Calibration Sensitivity in Analytical Chemistry: Definition, Measurement, and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of calibration sensitivity, a fundamental parameter in analytical chemistry that measures how strongly an instrument's signal responds to changes in analyte concentration.

Calibration Sensitivity in Analytical Chemistry: Definition, Measurement, and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of calibration sensitivity, a fundamental parameter in analytical chemistry that measures how strongly an instrument's signal responds to changes in analyte concentration. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the theoretical foundation of calibration sensitivity, contrasts it with related concepts like analytical and functional sensitivity, and details practical calibration methodologies from single-point to advanced multi-point techniques. The content further addresses troubleshooting common issues, optimizing performance across diverse matrices, and integrating sensitivity validation within regulatory frameworks to ensure robust, compliant analytical methods in pharmaceutical development and quality control.

What is Calibration Sensitivity? Core Concepts and Definitions

In the field of analytical chemistry, calibration sensitivity is a fundamental figure of merit that quantifies the change in instrumental response relative to a change in analyte concentration. Formally, it is defined as the slope of the calibration curve at the concentration of interest [1] [2]. This parameter, often denoted as m in the linear equation y = mx + b, provides a direct measure of an analytical method's ability to distinguish between small differences in concentration [1] [2]. A steeper slope indicates higher sensitivity, meaning the instrument produces a larger signal change for a given concentration change, which is particularly crucial for detecting trace analytes in fields like pharmaceutical development and environmental monitoring [3].

The relationship between signal and concentration is foundational. In a typical quantitative analysis, the instrumental response (y-axis) is plotted against the concentration of standard solutions (x-axis) to generate a calibration curve [1]. The slope of this curve, the calibration sensitivity, is not merely a statistical parameter but a central component in the calculation of unknown concentrations from measured signals using the inverse of the calibration equation [1] [2].

Quantitative Data and Figures of Merit

Calibration sensitivity works in concert with other analytical figures of merit to fully characterize a method's performance. Limit of detection (LOD) and limit of quantitation (LOQ) define the lowest concentrations that can be reliably detected or quantified, while the linear dynamic range establishes the concentration interval over which the method provides a linear response [4].

Table 1: Key Analytical Figures of Merit in Quantitative Analysis

| Figure of Merit | Symbol/Abbreviation | Definition | Relationship to Calibration Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Sensitivity | m | Slope of the calibration curve | Primary metric for the change in signal per unit change in concentration [1] [2]. |

| Limit of Detection | LOD | Lowest concentration that can be detected but not necessarily quantified | A higher sensitivity generally lowers the LOD, as the signal becomes more distinguishable from noise. |

| Limit of Quantitation | LOQ | Lowest concentration that can be quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy | A higher sensitivity generally lowers the LOQ. |

| Linear Dynamic Range | - | Concentration interval over which the response is linearly proportional to concentration | The range over which the sensitivity (m) remains constant [4]. |

| Coefficient of Determination | R² | Statistical measure of the goodness-of-fit of the linear model | A value close to 1.0 indicates the linear model (and its slope) is a reliable predictor [5]. |

The precision of a concentration determined from a calibration curve can be calculated statistically. The standard deviation of the calculated concentration (s_x) depends on the standard error of the regression (s_y), the calibration sensitivity (m), the number of calibration standards (n), the number of replicate measurements of the unknown (k), and where the unknown's signal falls relative to the mean of the standard signals [1]. The error is minimized when the signal from the unknown is close to the mean signal of the calibration standards [1].

Experimental Protocols for Determining Calibration Sensitivity

Accurate determination of calibration sensitivity requires a rigorous experimental approach to constructing the calibration curve. The following protocol details the critical steps.

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Calibration

| Item | Function and Critical Specifications |

|---|---|

| Standard Solution | A solution with a known, high-purity concentration of the analyte. Used to prepare all calibration standards [5]. |

| Solvent | A high-purity solvent compatible with both the analyte and the instrument (e.g., deionized water, methanol). Must be the same as used for the unknown samples [5]. |

| Volumetric Flasks | For precise preparation and dilution of standard solutions to ensure accurate known concentrations [5]. |

| Precision Pipettes and Tips | For accurate measurement and transfer of liquid volumes during serial dilution. Must be properly calibrated [5]. |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument to measure the analytical signal (absorbance). Requires calibration with a blank solution before measuring standards [5] [6]. |

| Cuvettes | Sample holders for the spectrophotometer. Must be clean and matched; quartz is required for UV measurements [5]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

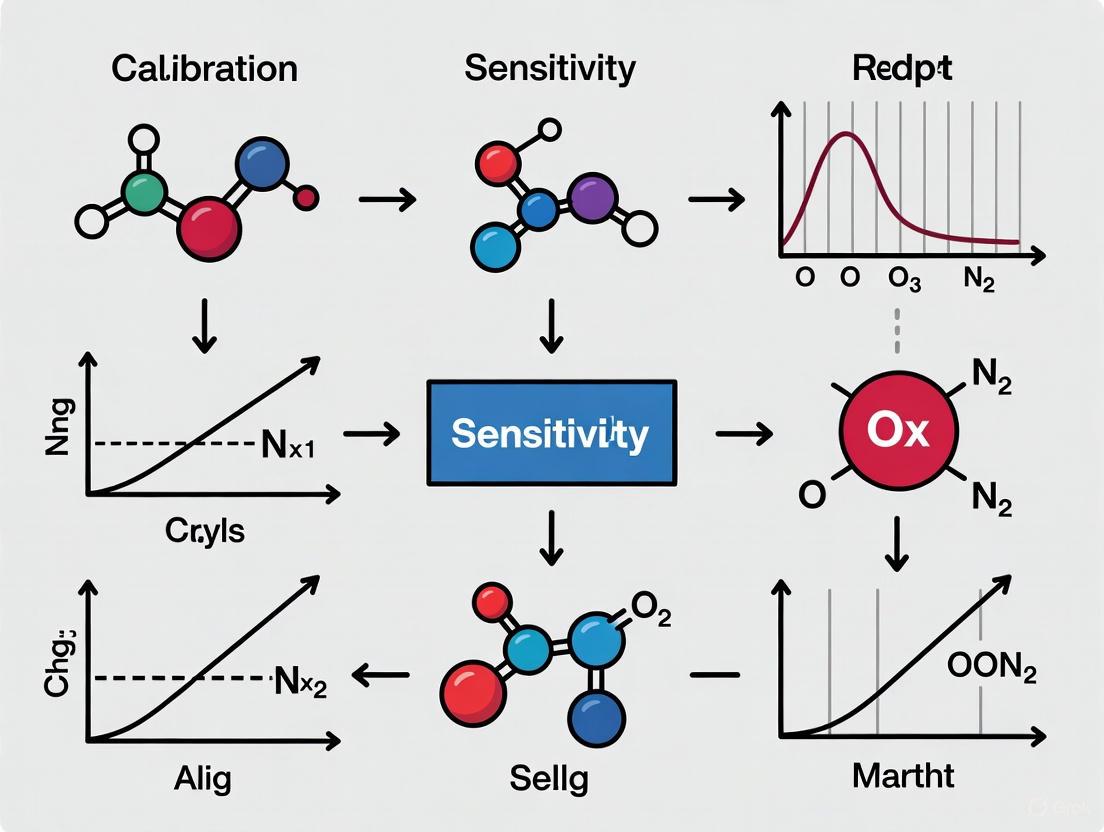

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow for establishing a calibration curve and determining its sensitivity.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for determining calibration sensitivity.

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Begin by preparing a concentrated stock solution of the analyte with a precisely known concentration. A series of standard solutions is then prepared via serial dilution [5]. A minimum of five standards is recommended to establish a reliable curve, and they should span the expected concentration range of the unknown samples [5].

- Instrumental Measurement: The analytical signal (e.g., absorbance in UV-Vis spectrophotometry) for each standard is measured using the appropriate instrument [5] [6]. It is critical that all standards and unknowns are measured under identical conditions, including using the same solvent matrix, to avoid matrix effects that can alter the sensitivity [3] [1]. Each standard should be measured in replicate (e.g., 3-5 readings) to assess measurement precision [5].

- Data Analysis and Calculation: The mean signal for each standard is plotted against its concentration. Linear regression analysis is performed on the data points to fit the best straight line, yielding the equation y = mx + b, where m is the calibration sensitivity and b is the y-intercept [1] [2] [5]. The coefficient of determination (R²) should be calculated to evaluate the linearity of the relationship, with a value close to 1.0 indicating a good fit [5].

Advanced Considerations and Innovations

Overcoming Practical Challenges

A perfectly linear calibration is often an ideal scenario. In practice, several factors can affect the sensitivity and linearity of a method. Matrix effects occur when components in the sample other than the analyte alter the instrumental response, leading to inaccuracies [3] [1]. This can be mitigated by using matrix-matched calibration, where standards are prepared in a medium that closely mimics the sample matrix [3].

Furthermore, the relationship between signal and concentration may plateau at higher concentrations due to instrumental saturation or a finite number of binding sites on a sensor surface, as is common in techniques like Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) [4]. In such cases, a non-linear model (e.g., Langmuir isotherm) may be required, and the calibration sensitivity becomes a function of concentration rather than a single constant value [4].

Recent Methodological Advances

Recent research has focused on improving the robustness and accuracy of calibration.

- Calibration by Proxy and Multiple Internal Standards: To correct for instrument sensitivity variations and matrix effects, novel methods use multiple internal standards to build more robust calibration curves, leading to improved accuracy and precision [3].

- Probabilistic Model Calibration: In complex computational models, new separation approaches transform high-dimension calibration problems into a series of simpler, low-dimension problems. This allows for more efficient and accurate identification of model parameters [7].

- Standardization in Emerging Techniques: In fields like Magnetic Particle Imaging (MPI), studies show that the environment (e.g., solution vs. cellular) significantly impacts the calibration curve. This has led to a push for new standardization, such as calibrating against the number of labelled cells rather than just iron content, ensuring biologically relevant quantification [8].

Calibration sensitivity, defined as the slope of the calibration curve, is a cornerstone of quantitative analytical chemistry. It is a direct measure of an analytical method's responsiveness to changes in analyte concentration. Its accurate determination relies on a rigorous experimental protocol involving careful preparation of standards, precise instrumental measurement, and robust statistical analysis. As analytical challenges grow more complex, with increasing demands for accuracy in complex matrices like biological systems, the fundamental principles of calibration and its associated sensitivity remain paramount. Continued innovation in calibration methodologies ensures that this foundational concept will continue to underpin reliable quantification in scientific research and drug development.

In analytical chemistry, the term "sensitivity" is frequently used, but it carries distinct and critical meanings depending on its context. Specifically, calibration sensitivity and analytical sensitivity represent fundamentally different concepts that describe a method's performance. Understanding this difference is not merely academic; it is essential for developing robust analytical methods, correctly interpreting data, and ensuring the reliability of results in drug development and clinical diagnostics. Within the broader thesis on calibration sensitivity in analytical chemistry research, this guide clarifies these concepts, preventing the common misinterpretations that can compromise data quality. Calibration sensitivity refers simply to the slope of the calibration curve, indicating how the instrumental response changes with analyte concentration [9]. In contrast, analytical sensitivity is a more comprehensive metric, defined as the ratio of the calibration sensitivity (slope) to the standard deviation of the measurement signal, thereby reflecting a method's ability to distinguish between different concentration levels based on both response change and precision [9] [10].

Conceptual Foundations and Definitions

Calibration Sensitivity

Calibration sensitivity, also known as simply "sensitivity" in some contexts, is defined as the slope of the calibration function [9] [10]. For a quantitative analytical method, it describes how strongly the measurement signal changes as a function of the change in the analyte's concentration. Mathematically, it is expressed as the differential quotient ( S = \frac{dy}{dx} ), where y is the measurement signal and x is the concentration or amount of the component to be determined [10]. A steeper slope indicates a higher calibration sensitivity, meaning that even small differences in concentration can cause significant changes in the measurement signal, making them easier to distinguish [9]. It is a fundamental property of the instrumental technique and the physicochemical interaction between the analyte and the detection system.

Analytical Sensitivity

Analytical sensitivity provides a more practical performance metric. It is defined as the ratio of the calibration sensitivity (the slope, m) to the standard deviation (SD) of the measured signal at a given concentration [9]. This definition incorporates the precision of the measurement system. A high analytical sensitivity means that the method can reliably distinguish between two different concentration levels because the difference in signal is large relative to the noise or variability in the signal [9]. It is crucial to note that analytical sensitivity is often confused with the Limit of Detection (LOD), but they are distinct concepts. The LOD is the smallest amount of an analyte that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, with a specified degree of certainty, while analytical sensitivity describes the ability to distinguish between concentration-dependent measurement signals [9] [10].

A Critical Distinction from Diagnostic Sensitivity

In the medical and diagnostic fields, the term "diagnostic sensitivity" takes on an entirely different meaning, which is a common source of confusion. According to the Robert Koch Institute (RKI), diagnostic sensitivity is "the ability of the examination method to detect as many diseased persons as possible" [9]. It is a statistical measure of performance, calculated as the proportion of true positive results among all individuals who actually have the disease [True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives)] [9]. This concept relates to the clinical effectiveness of a test and has no direct relation to the analytical capabilities of a laboratory method to detect low concentrations of an analyte. For the purposes of this guide, focused on analytical chemistry, the primary distinction remains between calibration and analytical sensitivity.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Metrics

The following tables summarize the core definitions, characteristics, and performance criteria for the two types of sensitivity.

Table 1: Fundamental Parameters of Calibration and Analytical Sensitivity

| Parameter | Calibration Sensitivity | Analytical Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Slope of the calibration curve [9] [10] | Slope divided by the standard deviation of the measurement signal [9] |

| Mathematical Expression | ( S = \frac{dy}{dx} ) [10] | ( \frac{Slope (m)}{Standard\ Deviation (SD)} ) [9] |

| Primary Focus | Change in instrument response per unit change in concentration | Ability to distinguish between two different concentration levels |

| Relationship to Precision | Independent of measurement precision | Directly incorporates measurement precision |

| Common Misconception | Often mistakenly used to describe the lowest detectable concentration | Frequently confused with the Limit of Detection (LOD) |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics and Related Limits

| Characteristic | Description | Relationship to Sensitivity Concepts |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Blank (LOB) | The highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample containing no analyte are tested [9]. | Foundation for determining the Limit of Detection. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the LOB [9]. It is not synonymous with analytical sensitivity [9]. | A low LOD often, but not always, correlates with high analytical sensitivity. |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The lowest concentration at which the analyte can not only be detected but also measured with acceptable precision and trueness (typically defined by a CV ≤ 20%) [9] [11]. | Functional sensitivity is often mistakenly equated with the LOQ [9]. |

| Functional Sensitivity | A term from clinical diagnostics defined as the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with a defined imprecision (e.g., a CV of 20%) [9]. | Reflects practical usability, similar to LOQ. It is not the same as analytical sensitivity [9]. |

| LLOQ & ULOQ | The Lower and Upper Limits of Quantification define the validated range of a calibration curve. The LLOQ must have a precision ≤20% CV and accuracy within ±20% [11]. | Define the operational range where the calibration model and analytical sensitivity are valid. |

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Establishing the Calibration Curve

The foundation for determining both calibration and analytical sensitivity is a rigorously constructed calibration curve.

- Minimum Standards and Replicates: Regulatory guidance, such as the EURACHEM Guide and USFDA draft guidance, mandates a minimum of six non-zero calibration standards to properly assess the calibration function, with the sample at zero analyte concentration also included [12]. At the method validation stage, it is advisable to perform at least triplicate independent measurements at each concentration level to properly evaluate precision across the range [12].

- Standard Preparation and Range: Calibration standards should be prepared from a pure substance with known purity or a solution of known concentration [12]. The standard concentrations must cover the entire range expected in test samples and should be evenly spaced across this range. Preparing standards by sequential 50% dilution is not recommended, as it leads to uneven spacing and can cause "leverage," where a single point at the high end disproportionately influences the slope and intercept of the regression line [12].

- Linearity Assessment: The correlation coefficient (r) or R-squared (R²) should not be the sole indicator of linearity. IUPAC discourages this practice [12]. A more robust assessment is the analysis of variance (ANOVA) for lack-of-fit (LOF). This test compares the variance due to LOF to the variance due to pure error through an F-test. A statistically significant LOF indicates the linear model may be inadequate [12].

Calculating Calibration and Analytical Sensitivity

- Plot the Calibration Curve: Graph the mean instrument response (y-axis) against the known concentration of each standard (x-axis).

- Perform Linear Regression: Use an appropriate fitting algorithm (e.g., ordinary least squares, OLS) to determine the line of best fit, which has the equation ( y = mx + b ), where

mis the slope andbis the y-intercept. - Determine Calibration Sensitivity: The calibration sensitivity is the value of the slope,

m, of the calibration curve [9] [10]. - Determine Analytical Sensitivity:

- At a specific concentration level, calculate the standard deviation (SD) of the measured signal from the replicate measurements.

- The analytical sensitivity at that concentration is then calculated as: ( \frac{m}{SD} ) [9].

Protocol for Functional Sensitivity (LOQ) Determination

Functional sensitivity, often analogous to the LOQ, is determined based on precision profiles.

- Prepare Test Material: Use samples (e.g., patient sera, pooled matrix) with the analyte present at different concentrations, preferably spanning the low end of the measuring range.

- Replicate Measurements: Analyze each concentration level multiple times (e.g., across multiple days) to capture total imprecision.

- Calculate Imprecision: For each concentration level, calculate the mean concentration and the coefficient of variation (CV).

- Establish the Threshold: The functional sensitivity or LOQ is defined as the lowest concentration at which the CV is less than or equal to an acceptable threshold, typically 20% in clinical chemistry and bioanalysis [9] [11].

Experimental Workflow for Sensitivity Determination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Calibration

| Item | Function in Sensitivity Analysis |

|---|---|

| Primary Reference Standard | A pure substance of known purity and identity used to prepare the stock solution for calibration standards. It is the foundational material for establishing trueness. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibrators | Calibration standards prepared in a medium identical or similar to the sample matrix (e.g., plasma, urine). This is critical for compensating for "matrix effects" that can alter the analytical signal. |

| Internal Standard (IS) | A reference compound, structurally similar but not identical to the analyte, added in a fixed amount to all samples and standards. The IS corrects for variability during sample preparation and analysis [3]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples with known concentrations of the analyte prepared independently from the calibration standards. QCs are used to monitor the stability and performance of the analytical method over time. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Reference materials characterized by a metrologically valid procedure, with one or more specified property values accompanied by a certificate. CRMs are used for method validation and verifying accuracy. |

Signaling Pathways and Logical Relationships

The relationship between the key concepts in method validation can be visualized as a hierarchical pathway where foundational metrics build towards practical performance characteristics. The process begins with the calibration curve, which is defined by its slope (calibration sensitivity) and the standard deviation of measurements. The ratio of these two parameters yields the analytical sensitivity, which describes the method's fundamental power to discriminate between concentrations. This intrinsic capability, in turn, supports the determination of practical application limits. The most critical of these is the Limit of Quantification (LOQ), or functional sensitivity, which represents the lowest concentration that can be measured with acceptable precision in a real-world setting. It is crucial to understand that diagnostic sensitivity operates on an entirely different pathway, being a statistical measure of clinical performance unrelated to the analytical method's low-concentration capabilities.

Conceptual Relationships in Sensitivity Analysis

In summary, the distinction between calibration sensitivity and analytical sensitivity is fundamental to sound analytical practice. Calibration sensitivity is a measure of the responsiveness of the detection system, defined simply by the slope of the calibration curve. Analytical sensitivity, however, is a more robust figure of merit that incorporates the precision of the measurement, providing a true indicator of a method's ability to distinguish between different analyte concentrations. For researchers and drug development professionals, a correct understanding and application of these terms is critical for method development, validation, and ensuring the reliability of data submitted for regulatory approval. Focusing solely on the slope of the calibration curve without considering the associated noise and variability offers an incomplete picture of an assay's capability, potentially leading to poor decision-making in both the laboratory and the clinic.

Calibration Sensitivity and the Fundamental Equation S = kACA + Sreag in Analytical Chemistry

Calibration sensitivity, represented by the term (kA) in the fundamental analytical equation (S = kA CA + S{reag}), serves as a cornerstone of method development in analytical chemistry. This parameter defines the capability of an analytical method to detect minute concentration changes of an analyte, directly impacting the reliability and sensitivity of quantitative measurements. Within the context of a broader thesis on calibration sensitivity, this technical guide explores its theoretical foundation, practical determination, and contemporary applications, with particular emphasis on pharmaceutical analysis and drug development. The establishment of a method's sensitivity through rigorous calibration protocols constitutes an essential prerequisite for generating valid analytical data, ensuring regulatory compliance, and making critical decisions in research and quality control.

In analytical chemistry, the relationship between an instrument's response and the concentration of an analyte is quantitatively described by the fundamental equation (S = kA CA + S{reag}), where (S) is the measured signal, (CA) is the analyte concentration, (S{reag}) is the contribution from the reagent blank (background signal), and (kA) is the calibration sensitivity [13]. The sensitivity (k_A) represents the change in instrument response per unit change in analyte concentration, effectively the slope of the calibration curve. A method with high sensitivity will produce a significant change in signal for a small change in concentration, which is particularly crucial for detecting and quantifying low-abundance analytes in complex matrices such as biological fluids or pharmaceutical formulations.

The determination of (kA) is therefore central to the standardization of any analytical method [13]. In an ideal scenario with a linear response, (kA) remains constant across the concentration range. However, in practice, sensitivity can be influenced by chemical interferences, instrumental parameters, and matrix effects, necessitating empirical determination through carefully designed calibration procedures. Understanding and accurately determining this parameter is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental aspect of ensuring the metrological integrity of an analytical method, forming a critical component of any thesis investigating the principles of chemical measurement science.

Theoretical Foundations and the Fundamental Equation

The foundational equation (S = kA CA + S{reag}) provides a linear model that forms the basis for most quantitative analytical determinations [13]. The term (S{reag}) accounts for the signal generated in the absence of the analyte, originating from reagents, solvents, or instrumental background. To isolate the signal attributable solely to the analyte ((SA)), this blank signal must be accounted for, yielding the simplified relationship (SA = kA CA) [13]. This model assumes a direct, proportional relationship between the net analyte signal and its concentration, an assumption that must be verified experimentally.

The calibration sensitivity, (kA), is theoretically influenced by the underlying physicochemical properties of the analyte and the analytical technique employed. For instance, in spectrophotometry, (kA) is governed by the molar absorptivity of the analyte according to the Beer-Lambert law. In chromatographic techniques, it relates to the detector's response factor for the specific compound. In practice, the theoretical value of (kA) is often difficult to calculate ab initio due to non-ideal behavior, instrumental variations, and matrix effects. Consequently, the value of (kA) is most reliably established by analyzing a series of standard solutions with known analyte concentrations [13]. The robustness of this determination is paramount, as any error in calculating (k_A) propagates directly into all subsequent concentration calculations for unknown samples.

Quantitative Determination of Sensitivity

The process of determining the calibration sensitivity (k_A) can be approached through different standardization strategies, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The choice of strategy depends on factors such as the expected concentration range, required accuracy, and available resources.

Single-Point vs. Multiple-Point Standardization

The most straightforward method for determining (kA) is a single-point standardization. This involves measuring the signal, (S{std}), for a single standard solution of known concentration, (C{std}). The sensitivity is then calculated as (kA = S{std} / C{std}) [13]. Subsequently, the concentration of an unknown sample, (CA), is calculated from its signal, (S{samp}), using (CA = S{samp} / kA). While simple and efficient, this approach is highly susceptible to error. It inherently assumes that (kA) is constant and that the calibration curve passes through the origin, which may not be valid. Any random error in the measurement of the single standard or a failure of the linearity assumption introduces a determinate error into all future analyses [13].

A more robust approach is multiple-point standardization, which involves preparing a series of standards that bracket the expected concentration range of the samples. A plot of (S{std}) versus (C{std}) generates a calibration curve, and the relationship is defined using a curve-fitting algorithm, such as linear regression based on the method of least squares [13]. The slope of the resulting best-fit line provides a statistically sound estimate of (kA). This method minimizes the influence of random error in any single standard and does not require the assumption that the curve passes through the origin, as the y-intercept can account for (S{reag}) [13]. A calibration curve with at least three standards is recommended, though more are preferable for establishing linearity and precision.

Key Sensitivity Metrics: LOD and LOQ

While (k_A) defines the analytical sensitivity across the concentration range, the practical utility of a method at low concentrations is defined by two key performance metrics: the Limit of Detection (LOD) and the Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) [14].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): This is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the background noise. It represents the point at which a signal is detectable, though not necessarily quantifiable with acceptable precision. Regulatory guidelines often define LOD using a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 [14].

- Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): This is the lowest concentration that can be quantitatively measured with stated accuracy and precision. The LOQ is crucial for methods that must report low-level impurities or biomarkers. It is typically defined by a signal-to-noise ratio of 10:1 [14].

These metrics are intrinsically linked to the calibration sensitivity. A method with a higher (k_A) will, all else being equal, yield lower (better) LOD and LOQ values, enhancing the method's capability for trace analysis.

Table 1: Methods for Determining Sensitivity and Detection Limits

| Parameter | Definition | Common Determination Methods | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Sensitivity ((k_A)) | Slope of the calibration curve; change in signal per unit change in concentration. | Single-point standardization: (kA = S{std} / C_{std}) [13]. Multiple-point standardization: Linear regression of a calibration curve [13]. | Single-point is simple but error-prone. Multiple-point is robust and accounts for linearity. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest concentration that can be detected. | Signal-to-Noise: S/N = 3:1 [14]. Statistical: Based on standard deviation of the blank or calibration curve [14]. | Should be verified experimentally with replicates. Critical for distinguishing analyte from noise. |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | Lowest concentration that can be quantified with accuracy and precision. | Signal-to-Noise: S/N = 10:1 [14]. Statistical: Based on standard deviation and the slope of the calibration curve [14]. | Must demonstrate acceptable precision and accuracy at the LOQ level. |

Advanced Methodologies and Applications

Innovative calibration strategies continue to evolve, addressing challenges such as matrix effects and the unavailability of high-purity reference materials.

Relative Molar Sensitivity (RMS)

A significant advancement in calibration methodology is the use of Relative Molar Sensitivity (RMS), which quantifies an analyte using a certified reference material (CRM) of a different, non-analyte compound [15]. The RMS is defined as the response ratio of the analyte to that of the non-analyte CRM per unit mole. It is calculated from the ratio of the slopes of their respective calibration equations [15]:

[ RMS = \frac{\text{Slope of calibration equation (Analyte)}}{\text{Slope of calibration equation (Non-analyte Reference Material)}} ]

This approach allows for accurate quantification of an analyte even when an identical, high-purity reference material is unavailable. The RMS method has been successfully applied in therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) to quantify drugs like carbamazepine, phenytoin, and voriconazole in blood serum using carbamazepine or caffeine as the non-analyte reference material [15]. This enhances analytical efficiency and reduces costs while maintaining high reliability, as the RMS possesses traceability to the International System of Units (SI).

Modern Calibration Trends

The field of calibration is witnessing the adoption of sophisticated techniques to improve robustness and transferability. These include:

- Matrix-Matched Calibration: Using standards prepared in a medium identical or similar to the sample matrix to correct for interference effects and improve accuracy [3].

- Multiple Internal Standards: Deploying several internal standards to correct for instrument sensitivity variations and matrix effects across different analyte classes [3].

- Advanced Regression Techniques: Utilizing statistical models that account for heteroscedasticity (non-constant variance across the concentration range) to ensure more reliable quantification [3].

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Determination

This section provides a detailed methodology for establishing calibration sensitivity using a multiple-point standardization approach, applicable to common techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

Detailed Protocol: Establishing a Calibration Curve

Objective: To determine the calibration sensitivity ((k_A)) and linear range for an analyte using a multiple-point standardization method.

Materials and Reagents:

- Certified Reference Material (CRM) or high-purity analyte standard.

- Appropriate solvent (e.g., HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile).

- Volumetric flasks, pipettes, and micropipettes of appropriate accuracy.

- Analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC system with UV detector, mass spectrometer).

Procedure:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh and dissolve the CRM in solvent to prepare a primary stock solution of known concentration (e.g., 1 mg/mL).

- Calibration Standard Serial Dilution: Perform serial dilutions of the stock solution to prepare at least 5-8 standard solutions that bracket the expected sample concentration range. For example, prepare standards at 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0, 10.0, 25.0, and 50.0 μg/mL.

- Instrumental Analysis: Inject each calibration standard into the analytical instrument in triplicate, using optimized and consistent instrument parameters. Record the analyte signal (e.g., peak area) for each injection.

- Blank Analysis: Analyze a solvent blank to determine the background signal, (S_{reag}).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the average signal for each concentration level.

- Subtract the average blank signal from each average standard signal to obtain the net analyte signal, (SA).

- Plot (SA) (y-axis) against the nominal standard concentration (x-axis).

- Perform linear regression analysis ((y = mx + c)) on the data. The slope ((m)) of the best-fit line is the calibration sensitivity, (k_A). The coefficient of determination (R²) should be ≥ 0.995 to confirm acceptable linearity.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for determining calibration sensitivity, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Calibration Sensitivity Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials required for performing sensitivity determination and calibration, as exemplified in the protocol above and in advanced methodologies like Relative Molar Sensitivity.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Calibration Experiments

| Item | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a traceable standard with defined purity for accurate calibration curve construction. | Used as the primary standard in a multiple-point calibration protocol [15]. |

| Internal Standards | A compound, different from the analyte, added in constant amount to all standards and samples to correct for instrumental variability and sample preparation losses. | Used in chromatographic methods to improve precision [3]. |

| Matrix-Matched Standards | Calibration standards prepared in a solution that mimics the sample matrix (e.g., control serum). Corrects for matrix effects that can suppress or enhance the analyte signal. | Essential for accurate bioanalysis of drugs in plasma or serum [3] [15]. |

| Non-Analyte Reference Material (for RMS) | A CRM of a different compound used to quantify the analyte via the Relative Molar Sensitivity factor, bypassing the need for an identical analyte CRM. | Carbamazepine used as a non-analyte reference to quantify phenytoin in serum via RMS [15]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Columns | Used for sample clean-up and pre-concentration of analytes from complex matrices, reducing interferences and improving signal-to-noise ratio. | Pre-treatment of control serum samples before HPLC analysis in RMS method development [15]. |

Calibration sensitivity, (kA), is far more than a numerical coefficient; it is a fundamental parameter that bridges theoretical analytical chemistry and practical quantitative measurement. Its accurate determination via rigorous calibration protocols—moving beyond simplistic single-point to robust multiple-point standardizations—is critical for method validation and reliability. The ongoing innovation in methodologies, such as Relative Molar Sensitivity and matrix-matched calibration, demonstrates the dynamic nature of this field, continually addressing challenges in pharmaceutical analysis and bioanalysis. A deep understanding of the principles governing the equation (S = kA CA + S{reag}) and its proficient application ensures that analytical data meets the stringent demands of modern research, drug development, and regulatory compliance, forming a foundational pillar of any scholarly investigation into analytical chemistry.

Why It's Not the Limit of Detection (LOD) or Limit of Quantification (LOQ)

In analytical chemistry, the terms calibration sensitivity, Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) are often mistakenly used interchangeably. This whitepaper clarifies their distinct definitions, roles, and relationships within analytical method validation. While calibration sensitivity represents the ability of a method to distinguish between small differences in analyte concentration, LOD and LOQ define the ultimate detection and quantification capabilities, respectively. Understanding these differences is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals to properly characterize analytical methods and ensure generated data is "fit for purpose" in regulatory submissions and clinical decision-making.

The proper characterization of an analytical method's capability at low analyte concentrations is fundamental to its appropriate application in pharmaceutical research and development. The sensitivity of an analytical method is a concept often misunderstood due to the existence of multiple related but distinct performance parameters. The calibration sensitivity, formally defined as the slope of the calibration curve, represents the change in instrument response per unit change in analyte concentration [16] [13]. In contrast, the Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the analytical background noise, but not necessarily quantified with precision [17] [18]. The Limit of Quantification (LOQ), always greater than or equal to the LOD, is the lowest concentration at which the analyte can not only be detected but also quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision, meeting predefined goals for bias and imprecision [16] [19].

Confusion arises because these parameters are mathematically related yet serve different purposes in method validation. This paper delineates the theoretical foundations, computational methodologies, and practical applications of each parameter, providing a framework for their proper use in drug development contexts.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Relationships

Calibration Sensitivity: The Slope of the Response

Calibration sensitivity, often simply called "sensitivity," is quantitatively expressed as the slope of the calibration curve within the linear range [13]. For a calibration curve following the linear equation ( S = mC + b ), where ( S ) is the measured signal, ( C ) is the analyte concentration, ( m ) is the slope, and ( b ) is the y-intercept, the calibration sensitivity is represented by ( m ). A steeper slope indicates a more sensitive method, as small concentration differences produce large changes in the instrumental response [20]. This parameter is foundational because both LOD and LOQ calculations incorporate the calibration sensitivity in their determination, reflecting how effectively the analytical system converts analyte concentration into a measurable signal.

Limit of Detection (LOD): The Threshold of Detection

The LOD addresses a fundamental question: "What is the lowest concentration that can be statistically distinguished from a blank sample?" The LOD is not the concentration that produces zero signal; even blank samples containing no analyte can produce an analytical signal due to background noise [16]. Statistically, the LOD is determined to minimize false positives (Type I error, α) and false negatives (Type II error, β) [18]. According to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) EP17 guideline, the LOD is derived using both the Limit of Blank (LoB) and data from a low-concentration sample [16]:

LoB = mean~blank~ + 1.645(SD~blank~) LOD = LoB + 1.645(SD~low concentration sample~)

The factor 1.645 corresponds to a 95% one-sided confidence level, assuming a Gaussian distribution of the blank and low-concentration sample measurements [16]. Alternative approaches, such as those based on signal-to-noise ratio, define LOD as the concentration that yields a signal 3 times the noise level, while methods using the calibration curve slope (m) and the standard deviation of the blank (σ) calculate LOD as ( \frac{3.3\sigma}{m} ) [17].

Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The Threshold of Reliable Quantification

While the LOD indicates presence or absence, the LOQ defines the lower limit for precise numerical measurement. The LOQ is the lowest analyte concentration that can be quantified with "acceptable precision and accuracy" under stated experimental conditions [18] [19]. The precision requirement is typically expressed as a percentage coefficient of variation (%CV), with a CV of 10% or 20% being common targets [16]. The mathematical derivation often follows a similar form to the LOD but with a higher multiplier to achieve greater confidence:

LOQ = ( \frac{10\sigma}{m} ) [17]

This factor of 10, compared to the 3.3 used for LOD, reflects the more stringent precision requirements for quantification versus mere detection [17]. The LOQ may be equivalent to the LOD if the predefined bias and imprecision goals are met at the LOD concentration, but it is typically found at a higher concentration [16].

Table 1: Core Definitions and Purposes

| Parameter | Formal Definition | Primary Purpose in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Sensitivity | Slope of the calibration curve (( m )) [13] | Measures the method's ability to distinguish small concentration differences |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lowest concentration reliably distinguished from the blank [16] | Answers "Is the analyte present?" (Detection) |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Lowest concentration quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy [16] [19] | Answers "How much of the analyte is present?" (Quantification) |

Experimental Protocols for Determination

Protocol for Establishing Calibration Sensitivity

Calibration sensitivity is determined empirically through the construction of a calibration curve.

- Standard Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions at multiple concentrations (regulatory guidance often recommends a minimum of 5-7 different levels) across the expected working range [12]. The standards should be prepared in a matrix similar to the sample matrix to minimize interference effects.

- Instrumental Analysis: Measure the instrumental response for each standard solution. Replicate measurements (at least triplicate) at each concentration level are advised, particularly during method validation, to evaluate precision [12].

- Curve Fitting and Slope Calculation: Plot the mean response against the concentration for each standard and perform a linear regression analysis. The slope (( m )) of the resulting line (( S = mC + b )) is the calibration sensitivity [13]. The use of ordinary least-squares (OLS) or weighted least-squares (WLS) regression should be justified based on the error structure across the concentration range [12].

Protocol for Determining LOD and LOQ

The CLSI EP17 guideline provides a standardized approach for determining LOD and LOQ [16].

Sample Types and Replication:

- LoB Determination: Test a minimum of 20 replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte). For initial method establishment, up to 60 replicates are recommended to capture population performance [16].

- LOD/LOQ Determination: Test a minimum of 20 replicates of a sample containing a low concentration of analyte, expected to be near the LOD.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean and standard deviation (SD) of the blank measurements.

- Compute the LoB as: mean~blank~ + 1.645(SD~blank~).

- Calculate the mean and SD of the low-concentration sample.

- Compute the LOD as: LoB + 1.645(SD~low concentration sample~).

- The LOQ is determined as the lowest concentration at which the analyte can be measured with predefined imprecision (e.g., ≤20% CV) and bias. This is established by testing samples at or above the LOD and determining the concentration where these performance goals are met [16].

Alternative ICH Q2(R1) Approaches:

- Visual Inspection: For non-instrumental methods, the LOD/LOQ can be determined by analyzing samples with known low concentrations and estimating the minimum level for detection/quantification [17].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Applicable to chromatographic methods. LOD requires a S/N of 3:1, while LOQ requires a S/N of 10:1 [17].

- Calibration Curve: Using the standard deviation of the response (σ) and the slope of the calibration curve (S), LOD = 3.3σ/S and LOQ = 10σ/S [17].

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Protocols for LOD and LOQ

| Aspect | LOD Protocol | LOQ Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Type | Sample containing low concentration of analyte [16] | Sample containing low concentration at or above the LOD [16] |

| Key Objective | Distinguish analyte signal from blank with confidence [16] | Achieve predefined targets for bias and imprecision [16] |

| Typical S/N Criterion | 3:1 [17] | 10:1 [17] |

| Typical SD/Slope Factor | 3.3 [17] | 10 [17] |

| Primary Outcome | Concentration for reliable detection [19] | Concentration for reliable quantification [19] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sensitivity and Limit Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Analyte | Used to prepare primary standard solutions. Known purity is critical for accurate calibration and correct determination of sensitivity, LOD, and LOQ [12]. |

| Matrix-Matched Blank | A sample identical to the test material but devoid of the analyte. Essential for accurate LoB and LOD determination, as it accounts for matrix-induced background signal [16] [21]. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibrators | Standard solutions prepared in a medium identical or similar to the sample matrix. Reduces interference effects (matrix effects), leading to a more accurate calibration slope and more reliable LOD/LOQ values [3]. |

| Internal Standard | A reference compound added in a fixed amount to all samples, blanks, and standards. Corrects for variability during sample preparation and analysis, improving the precision of the method, which is critical for LOQ determination [3]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Materials | Stable materials with known concentrations of analyte, typically at low, medium, and high levels. Used to verify that the analytical method, including its calibrated sensitivity and limits, is performing as expected over time [16]. |

Visualizing the Relationship: From Blank to Quantification

The following diagram illustrates the statistical relationship and progression from the blank measurement through to the LOQ, highlighting the roles of Type I (α, false positive) and Type II (β, false negative) errors.

Diagram Title: Statistical Progression from Blank to LOQ

Critical Considerations for Method Validation

The Pitfalls of Single-Point Calibration

Relying on a single standard to determine calibration sensitivity is ill-advised. A single-point standardization assumes the calibration curve passes through the origin and that the sensitivity is constant across the concentration range, an assumption that often does not hold true [13]. Any error in the determination of the slope (( k_A )) carries over into the calculation of sample concentrations and, by extension, into the estimation of LOD and LOQ. A multiple-point standardization using at least three standards (more are preferable) that bracket the expected concentration range minimizes this risk and provides a more robust measure of the true calibration sensitivity [13].

Misuse of the Correlation Coefficient (r)

A common mistake in evaluating calibration linearity, and thus the validity of the calculated sensitivity, is the over-reliance on the correlation coefficient (r) or the coefficient of determination (R²). IUPAC discourages the use of r to assume linearity in calibration [12]. A high r value indicates a strong linear relationship but does not prove the data is linear or that the model is appropriate. A more statistically sound approach to linearity assessment involves the analysis of variance (ANOVA) and a lack-of-fit test, which compares the variation due to model error (lack-of-fit) to the variation due to pure measurement error [12].

Impact of Noise Structure on Sensitivity

The traditional definition of sensitivity, based on the slope of the calibration curve, is valid for univariate calibration. However, in multivariate calibration, this concept must be adapted. Advanced studies show that the classical sensitivity parameter is only useful for comparing method performance when instrumental noise is identically and independently distributed (iid) [20]. For real-world systems with more complex noise structures (e.g., correlated or proportional noise), a generalized analytical sensitivity parameter, defined as the inverse of the concentration uncertainty generated by real noise propagation, provides a more reliable figure of merit for method comparison [20].

Calibration sensitivity, LOD, and LOQ are distinct yet interconnected parameters that form a critical triad in the characterization of any analytical method. Calibration sensitivity (( m )) is a measure of the method's responsiveness to changes in concentration. The LOD defines the absolute detection threshold, and the LOQ establishes the boundary for reliable quantification. Confusing these terms, particularly misinterpreting the LOD as a level at which precise quantification is possible, can lead to flawed scientific conclusions and regulatory non-compliance.

For researchers and drug development professionals, a rigorous, statistically grounded approach to determining these parameters is non-negotiable. This involves using multi-point, matrix-matched calibration curves, adhering to established guidelines like CLSI EP17 or ICH Q2(R1) for LOD/LOQ determination, and employing proper statistical tests for linearity assessment. A clear understanding and correct application of these concepts ensure that analytical methods are truly "fit for purpose," providing reliable data that underpins critical decisions in pharmaceutical development.

Distinguishing Analytical Sensitivity from Diagnostic Sensitivity in Clinical Contexts

In the realms of analytical chemistry and clinical diagnostics, the term "sensitivity" carries critically distinct meanings. Its interpretation depends fundamentally on context: it can refer to the lowest concentration of an analyte an instrument can detect, or the ability of a medical test to correctly identify diseased individuals. Within the broader thesis on calibration sensitivity in analytical chemistry research, understanding this distinction is paramount. Calibration sensitivity, defined as the slope of a calibration curve, is a core concept in analytical chemistry that describes how strongly a measurement signal changes with the concentration of the analyte [9]. However, this is merely the starting point for a cascade of related, yet distinct, performance metrics. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, conflating these terms can lead to flawed method validation, misinterpreted data, and ultimately, impacts on patient care. This guide provides an in-depth technical exploration of analytical and diagnostic sensitivity, framing them within the experimental and calibration frameworks essential for rigorous research and development.

Foundational Concepts and Definitions

The Core Concepts

- Calibration Sensitivity: This is the foundational parameter in analytical chemistry. It is defined as the slope ((m)) of the calibration function, which is the curve relating the instrumental response to the concentration of the analyte [9]. A steeper slope indicates a more sensitive method, as a small change in concentration produces a large change in the measurement signal.

- Analytical Sensitivity: This parameter builds upon calibration sensitivity by incorporating precision. It is defined as the ratio of the calibration slope ((m)) to the standard deviation (SD) of the measurement signal at a given concentration (( \gamma = m / SD )) [9] [20]. This describes a method's ability to distinguish between two different concentration values, not just its responsiveness. It is important to note that analytical sensitivity is not synonymous with the Limit of Detection (LOD) or Limit of Quantification (LOQ) [9].

- Diagnostic Sensitivity: This is a statistical measure of clinical performance. It is defined as the ability of a diagnostic test to correctly identify individuals who have a disease [22] [23]. It is calculated as the proportion of true positives out of all individuals who actually have the disease [24] [25]. In this context, "sensitivity" refers to the test's accuracy in detecting a condition, not a chemical concentration.

Visualizing the Relationship and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these concepts, from instrumental calibration to clinical application, and highlights where confusion often arises.

Quantitative Comparison and Clinical Impact

The table below provides a clear, side-by-side comparison of the three sensitivity types, summarizing their definitions, contexts, and clinical implications.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Sensitivity Types

| Feature | Calibration Sensitivity | Analytical Sensitivity | Diagnostic Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Slope of the calibration curve [9] | Slope of calibration curve / standard deviation of measurement signal [9] [20] | Proportion of true positives identified: TP / (TP + FN) [24] [23] |

| Context | Analytical Chemistry | Analytical Chemistry / Method Validation | Clinical Diagnostics / Medical Statistics |

| What it Measures | Instrument response per unit concentration change | Ability to distinguish between two analyte concentrations | Test's ability to correctly identify diseased individuals |

| Primary Goal | Quantify instrument responsiveness | Quantify method's discriminative power | Maximize disease detection; minimize false negatives |

| Clinical Implication | Foundation for accurate quantification | Ensures reliable detection of clinically relevant concentration differences | Directly impacts patient outcomes; high value is critical for screening serious diseases [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Determination

Determining Calibration and Analytical Sensitivity

The determination of these parameters is grounded in robust calibration experiments. According to regulatory guidance, a minimum of six to seven different concentration levels (including a zero point) is recommended for a proper assessment of the calibration function [12]. Triplicate independent measurements at each level are advised to evaluate precision.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Calibration Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Primary Reference Standard | A pure substance with known purity, used as the source of the analyte to prepare calibration standards, ensuring traceability and accuracy [12]. |

| Internal Standard | A reference compound added in fixed quantity to all samples and standards to correct for variability during sample preparation and analysis [3]. |

| Matrix-Matched Solvents | A medium identical or similar to the sample matrix (e.g., serum, buffer) used to prepare calibration standards. This is critical to reduce matrix effects and interference, ensuring accurate quantification [3]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Samples with known concentrations of the analyte, different from the calibration standards, used to independently verify the performance and reliability of the calibration model. |

The experimental workflow for establishing a calibration curve and deriving sensitivity metrics is methodical. The diagram below outlines the key steps.

Determining Diagnostic Sensitivity

Determining diagnostic sensitivity requires a different, population-based approach. It involves comparing the test in question against a gold standard method (e.g., bacterial culture for an infection, or a clinically established diagnostic test) that is assumed to be correct [25].

Protocol:

- Define Cohort: Recruit a population of individuals whose disease status is unknown.

- Run Tests in Parallel: Subject each individual to both the new diagnostic test and the gold standard test.

- Construct a 2x2 Contingency Table: Tabulate the results to classify outcomes as True Positives (TP), False Positives (FP), True Negatives (TN), and False Negatives (FN) [24] [25].

- Calculate Diagnostic Sensitivity: Apply the formula: ( \text{Sensitivity} = \frac{TP}{TP + FN} ) [24] [23] [25].

Table 3: Example 2x2 Table for a Diagnostic Test for a Bacterial Pathogen (using qPCR vs. Culture as Gold Standard)

| Gold Standard: Positive (Diseased) | Gold Standard: Negative (Healthy) | |

|---|---|---|

| New Test: Positive | 238 (True Positive, TP) | 21 (False Positive, FP) |

| New Test: Negative | 2 (False Negative, FN) | 103 (True Negative, TN) |

Calculation from Table 3:

- Diagnostic Sensitivity = ( \frac{238}{238 + 2} = \frac{238}{240} = 99.2\% )

- Diagnostic Specificity = ( \frac{103}{103 + 21} = \frac{103}{124} = 83.1\% ) [25]

This demonstrates a test with excellent ability to rule out the disease (high sensitivity) but a more moderate ability to rule it in, due to the false positives.

The Critical Distinction in Practice

A test's analytical sensitivity (low detection limit) is a necessary but insufficient condition for high diagnostic sensitivity. A test must be analytically sensitive enough to detect the pathogen, but it can fail diagnostically if, for example, it does not detect all genetic variants of the pathogen, leading to false negatives [22].

Furthermore, other concepts add layers of complexity. Functional sensitivity is a related term used in clinical laboratories, defined as the lowest analyte concentration that can be measured with a coefficient of variation (CV) ≤ 20%. It reflects the precision of a test at low concentrations and is closer in concept to the LOQ than to analytical or diagnostic sensitivity [9].

For professionals in drug development, these distinctions are vital during method validation and regulatory submission. Adherence to guidelines like ICH Q2(R2) requires clear reporting of a method's detection and quantification capabilities (analytical performance) separately from its clinical utility (diagnostic performance) [26] [27]. Misunderstanding can lead to a method that is analytically superb but clinically unfit, potentially jeopardizing a product's development.

Implementing Calibration Methods: From Theory to Laboratory Practice

In analytical chemistry, calibration is the fundamental process of establishing a relationship between an instrument's response and the concentration of an analyte. The sensitivity of a method, formally defined as the change in instrument response for a given change in analyte concentration, is central to this relationship [13]. In univariate calibration, sensitivity is represented by the slope of the calibration curve, determining the method's ability to distinguish between small concentration differences [13] [20]. This technical guide examines two principal calibration approaches—single-point and multiple-point standardization—framing their selection criteria within the context of achieving metrologically sound sensitivity in pharmaceutical and clinical research.

The choice between these calibration strategies impacts not only analytical efficiency but also the fundamental reliability of quantitative results. While single-point calibration offers simplicity and speed, multiple-point calibration provides a more comprehensive characterization of the analytical sensitivity across a concentration range. Understanding their respective advantages, limitations, and appropriate application domains is essential for researchers and drug development professionals tasked with developing robust analytical methods.

Theoretical Foundations of Calibration Sensitivity

Defining Analytical Sensitivity

The classical definition of sensitivity relies on the slope of the calibration curve in univariate analysis [13]. This concept is encapsulated in the fundamental calibration equation:

[ SA = kA C_A ]

where ( SA ) is the analyte's signal, ( CA ) is the analyte's concentration, and ( k_A ) is the method's sensitivity [13]. In this framework, the sensitivity represents the proportionality constant that translates instrumental response into meaningful concentration data. For higher-order calibration scenarios, more sophisticated definitions of sensitivity have been developed, incorporating uncertainty propagation principles to maintain consistency across different analytical methodologies [20].

A related parameter, analytical sensitivity (( \gamma )), has been proposed for method comparison as it accounts for both the calibration slope and measurement error. It is defined as the ratio between the calibration slope and the standard measurement error, providing a more robust basis for comparing methodologies across different instrumental signals [20]. This generalized parameter represents the inverse of the concentration uncertainty generated by real noise propagation, making it an excellent indicator for method performance comparison, especially when dealing with complex noise structures beyond identically and independently distributed (iid) noise [20].

The Role of Calibration Curves

Calibration curves establish the mathematical relationship between instrument response and analyte concentration, serving as the primary tool for quantifying unknown samples [12]. These curves can be constructed using either single-point or multiple-point standardization approaches, with the choice significantly impacting the reliability of subsequent quantitative analysis.

A critical consideration in calibration is the potential for the relationship between signal and concentration to deviate from ideal linearity, particularly at concentration extremes. The limitations of correlation coefficients (( r ) or ( R^2 )) as indicators of linearity must be recognized, as they can be misleading when calibration points cluster near extremes [12]. Proper linearity assessment should instead employ statistical tests like analysis of variance (ANOVA) and lack-of-fit (LOF) testing to verify the linear model's appropriateness across the entire concentration range [12].

Single-Point Standardization

Principles and Methodology

Single-point standardization represents the simplest calibration approach, determining the sensitivity (( kA )) by measuring the signal for a single standard with known analyte concentration (( C{std} )) [13]. The sensitivity is calculated as:

[ kA = \frac{S{std}}{C_{std}} ]

Once ( kA ) is determined, the concentration of analyte in a sample (( CA )) is calculated from its signal (( S_{samp} )) using:

[ CA = \frac{S{samp}}{k_A} ]

This approach implicitly assumes a linear relationship that passes through the origin, meaning a zero analyte concentration would produce zero instrumental response [13] [28]. The experimental protocol involves analyzing a single standard solution and the reagent blank, then applying the calculated sensitivity factor to unknown samples analyzed within the same batch.

Experimental Applications

Single-point calibration has demonstrated utility in specific, well-defined analytical scenarios. A notable application published in 2024 established its viability for quantifying 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in clinical settings using LC-MS/MS [29]. Researchers validated the method over a concentration range of 0.05–50 mg/L and compared single-point calibration (using a 0.5 mg/L standard) against multi-point calibration for monitoring cancer patients undergoing 5-FU therapy.

The study reported remarkable agreement between methods, with a mean difference of -1.87% and a slope of 1.002 in Passing-Bablok regression analysis [29]. Critically, the calibration approach did not impact clinical decision-making for dose adjustments based on area under the curve (AUC) calculations, demonstrating that single-point calibration can produce clinically equivalent results while improving analytical efficiency [29].

In pharmaceutical analysis, single-point standardization has been successfully implemented in paper-based analytical devices. These systems incorporate pre-stored calibrants that react simultaneously with samples, enabling quantitative colorimetric assays for compounds like iron(III), nickel(II), and amino acids without requiring multiple standard preparations [30]. This approach simplifies field-based analysis while maintaining acceptable accuracy for many applications.

Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Advantages and Limitations of Single-Point Standardization

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Improved efficiency and faster analysis times [29] | Assumes linear relationship through origin, which may not hold true [13] |

| Reduced cost due to fewer standard preparations [29] | Vulnerable to determinate errors if true sensitivity differs [13] |

| Simplified workflow with minimal calculations [30] | Limited ability to detect non-linearity in response [13] |

| Suitable for automated clinical analyzers with limited concentration ranges [13] | Cannot characterize response across concentration range [28] |

| Random access capability on analytical instruments [29] | Prone to matrix effects that alter sensitivity [30] |

The fundamental limitation of single-point calibration arises from its assumption of constant sensitivity across all concentrations. If the true sensitivity decreases at higher concentrations (as shown in the "actual relationship" in Figure 1), a determinate error occurs that directly impacts quantitative accuracy [13]. This makes method validation across the intended concentration range essential before implementing single-point calibration.

Multiple-Point Standardization

Principles and Methodology

Multiple-point standardization involves preparing a series of standards at different concentrations that bracket the expected analyte concentration in samples [13]. A calibration curve is constructed by plotting the instrumental response (( S{std} )) against the known standard concentrations (( C{std} )), with the relationship typically determined by linear regression using the method of least squares [13] [12].

This approach does not assume proportionality between signal and concentration, instead deriving the exact mathematical relationship from the experimental data. The resulting calibration model can account for non-zero intercepts and verify linearity across the working range [28]. Regulatory guidelines often recommend specific calibration designs; for example, the EURACHEM Guide and USFDA draft guidance mandate a minimum of six non-zero calibration standards, while ISO standards may require up to ten concentration levels [12].

Experimental Design Considerations

Proper calibration design requires careful consideration of multiple factors:

Number of Standards: Regulatory guidelines typically require 5-10 non-zero concentrations, with 6-10 being common in LC-MS/MS applications [29] [12].

Replication: Triplicate independent measurements at each concentration level are recommended during method validation to evaluate precision [12].

Concentration Spacing: Even spacing across the calibration range is preferred, with concentrations selected to bracket expected sample concentrations [12].

Range: The calibration range should ensure unknown samples fall within the central portion where prediction uncertainty is minimized [12].

Advanced calibration designs may incorporate specialized configurations based on analytical goals. A "five-by-five" design (five replicates at each of five concentrations) is a common starting point, with variations that emphasize precision at specific ranges [31]. For example, additional low-level standards enhance detection capability, while increased replication at specification limits (e.g., 5% and 10% wt in assay methods) improves precision at critical decision points [31].

Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Multiple-Point Standardization

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Characterizes true response function across concentration range [13] | Increased analysis time and cost [29] |

| Detects and quantifies non-linearity [28] | Delayed result availability [29] |

| Minimizes effect of random errors through statistical fitting [13] | Complex data processing requirements [12] |

| Enables statistical evaluation of linearity (e.g., lack-of-fit) [12] | Consumes more reagents and standards [29] |

| Identifies outliers and leverage points [12] | May limit random access on instruments [29] |

The comprehensive nature of multiple-point calibration makes it particularly valuable during method development and validation, where understanding the complete concentration-response relationship is essential. It provides the statistical foundation for assessing method linearity, identifying potential matrix effects, and establishing valid measurement uncertainty estimates [12].

Decision Framework: Selecting the Appropriate Approach

Technical Considerations for Method Selection

Choosing between single-point and multiple-point standardization requires systematic evaluation of analytical requirements:

Concentration Range: Single-point calibration may be appropriate for limited concentration ranges (typically not spanning more than one order of magnitude), while multiple-point is essential for wider ranges [13] [31].

Linearity Verification: Prior verification of linearity and zero-intercept is mandatory for single-point calibration [28]. This can be assessed statistically by evaluating whether the confidence interval for the intercept includes zero [28].

Matrix Effects: Single-point calibration is vulnerable to matrix effects that alter sensitivity [30]. Multiple-point standard addition methods may be necessary when such effects are present [30].

Regulatory Requirements: Certain applications must comply with specific regulatory standards that may dictate calibration design, such as FDA requirements for method validation [12].

Quality Control: Multiple-point calibration provides built-in quality control through linearity assessment, while single-point methods require separate quality control samples to verify continuing accuracy [28].

Statistical Assessment for Single-Point Applicability

A straightforward statistical test can determine whether single-point calibration is justified:

- Perform multiple-point calibration across the intended range

- Conduct regression analysis and examine the confidence interval for the intercept

- If zero falls within the 95% confidence interval of the intercept, single-point calibration may be appropriate [28]

For example, in the tryptophan analysis case study, the intercept confidence interval included zero (-0.071 to 0.079), supporting the use of single-point calibration [28]. Conversely, in another example, the intercept confidence interval (9.52 to 10.72) excluded zero, indicating the need for multiple-point calibration [28].

Emerging Approaches and Hybrid Methods

Innovative calibration strategies continue to evolve, particularly for field-deployable analytical systems:

Calibrant-Loaded Paper Devices: These incorporate pre-stored calibrants that react simultaneously with samples, enabling both external calibration and standard addition on a single device [30].

Single-Point Standard Addition: This approach combines the benefits of standard addition (compensating for matrix effects) with the simplicity of single-point analysis [30] [32].

Generalized Sensitivity Parameters: New figures of merit, such as generalized analytical sensitivity, facilitate method comparison under different noise structures, enhancing calibration model selection [20].

These hybrid approaches are particularly valuable in resource-limited settings or point-of-care testing, where they balance analytical rigor with practical implementation constraints.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Single-Point Calibration Validation

Before implementing single-point calibration, thorough validation against a multiple-point approach is essential:

Prepare Standards: Prepare a minimum of 6-8 standard solutions across the intended analytical range, including a blank [12].

Analyze Standards: Analyze all standards in random order, preferably on different days to incorporate inter-day variability [31].

Construct Calibration Curve: Perform regression analysis and determine the confidence interval for the y-intercept.

Statistical Testing: Verify that the intercept confidence interval includes zero and assess residual patterns for systematic trends [28].

Compare Methods: Analyze quality control samples at relevant concentrations using both single-point and multiple-point approaches [29].

Decision Point: If no significant difference is found between methods and the intercept includes zero, single-point calibration may be implemented with ongoing quality control [29] [28].

Protocol for Multiple-Point Calibration

For rigorous method development and validation:

Design Calibration Scheme: Select 5-10 concentration levels evenly spaced across the analytical range [31] [12].

Include Blank: Always include a zero-concentration sample (blank) to characterize the baseline response [12].

Replication: Perform triplicate measurements at each concentration level, preferably on different days with fresh preparations [31] [12].

Randomization: Analyze standards in random order to minimize sequence effects [31].

Statistical Evaluation: Calculate regression parameters, assess lack-of-fit, and evaluate homoscedasticity [12].

Leverage Assessment: Identify potential leverage points (concentrations at the extremes that disproportionately influence the regression) and consider balanced spacing if necessary [12].

The selection between single-point and multiple-point standardization represents a critical decision point in analytical method development that directly impacts data quality and analytical efficiency. Single-point calibration offers practical advantages in well-characterized, limited concentration ranges where linearity and proportionality have been rigorously demonstrated. Multiple-point calibration provides a more comprehensive characterization of the concentration-response relationship, enabling detection of non-linearity and greater statistical robustness for regulatory applications.

Within the framework of calibration sensitivity, the optimal approach depends on the specific analytical context, with single-point methods potentially viable for routine clinical monitoring of drugs like 5-fluorouracil [29], while multiple-point approaches remain essential for method validation and applications requiring rigorous uncertainty quantification. As analytical technologies evolve, particularly in point-of-care testing, hybrid approaches that combine the efficiency of single-point analysis with the robustness of standard addition methodologies offer promising directions for future development.