Combating Calibration Drift in Optical Emission Spectrometers: A Guide for Reliable Biomedical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing calibration drift in Optical Emission Spectrometers (OES).

Combating Calibration Drift in Optical Emission Spectrometers: A Guide for Reliable Biomedical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing calibration drift in Optical Emission Spectrometers (OES). It covers the fundamental causes of drift, including environmental changes, component aging, and matrix effects. The content explores established and emerging calibration methodologies, from high-low standardization and internal standards to advanced automated and AI-driven techniques. Practical troubleshooting protocols and validation strategies using Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) and statistical process control are detailed to ensure data integrity, compliance, and the reliability of analytical results in biomedical and clinical research settings.

Understanding Calibration Drift: Causes, Impacts, and Detection in OES

Defining Calibration Drift and Its Critical Impact on Analytical Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is calibration drift? Calibration drift is the gradual change in the accuracy of a measurement instrument over time. It is defined as a slow variation in a performance characteristic, such as gain or offset, leading to deviations in the instrument's readings after its initial calibration [1] [2]. In the context of research, this can cause a model's predictions or a spectrometer's readings to diverge from established reference values [1] [3].

2. What are the most common causes of calibration drift in a laboratory instrument? The common causes can be categorized as follows:

- Environmental Factors: Sudden or gradual changes in ambient temperature or humidity [2] [4] [5].

- Physical Stress: Mechanical or electrical shock, vibration, or mishandling of the equipment [2] [4].

- Natural Degradation: The typical wear and tear from frequent use or simply aging of the instrument's components over time [2] [4].

3. Why is monitoring for calibration drift critical for researchers? Unaddressed calibration drift leads directly to measurement errors, which can compromise the integrity of experimental data [2]. This can have several critical impacts:

- Compromised Data Integrity: Skewed results can lead to incorrect scientific conclusions [2].

- Safety Risks: Inaccurate measurements in processes or formulations can pose safety hazards [2] [4].

- Economic Costs: Drift can necessitate the repetition of experiments, wasting valuable time and resources [6]. One study on calcium measurement estimated that a small analytical bias could lead to millions of dollars in associated costs per year [6].

4. How can I detect calibration drift in my optical emission spectrometer? Detection typically involves a control chart methodology [1].

- Method: Regularly measure three or more traceable reference standards over time and plot the results on a control chart.

- Detection: If the measurements of these standards show a consistent, incremental divergence from their known certified values, it signifies that your instrument is experiencing calibration drift and requires service [1]. Advanced computational methods also exist for detecting calibration drift in predictive models by monitoring the error between predictions and observed outcomes over time [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Addressing Calibration Drift

Symptom: Inconsistent readings from certified reference materials.

Diagnosis: Potential calibration drift. Resolution Protocol:

- Verify Environmental Conditions: Ensure the laboratory temperature and humidity are within the manufacturer's specified operating range for the spectrometer [5].

- Inspect for Physical Damage: Check the instrument for any signs of mishandling, corrosion, or particulate accumulation on optical components [4] [5].

- Execute a Diagnostic Run: Measure a set of certified calibration standards that cover the analytical range of interest.

- Analyze Data: Plot the results against the established values of the standards on a control chart. A statistically significant trend indicates drift [1].

- Action: Schedule professional calibration and any necessary maintenance. The instrument should not be used for data generation until the issue is resolved.

Symptom: Gradual, unexplained shifts in data trends over a long-term study.

Diagnosis: Likely gradual calibration drift. Resolution Protocol:

- Review Maintenance Logs: Check the history for the last calibration date and any recent environmental events (e.g., power surges, HVAC failures) [5].

- Analyze Quality Control (QC) Data: Scrutinize the performance of your internal quality control samples over time. A persistent directional bias confirms drift.

- Implement Corrective Action: Recalibrate the instrument using a validated, multi-point calibration procedure [6]. Re-measure recent samples if possible to correct the data.

- Preventive Strategy: Shorten the interval between routine calibrations and consider implementing continuous monitoring systems for critical instrument parameters [5].

Quantitative Analysis of Drift

Table 1: Methods for Calculating Drift Uncertainty

| Method | Description | Formula | When to Use | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drift Since Last Calibration [7] | Calculates the absolute difference in an instrument's reading for the same standard between two consecutive calibrations. | `D = | y₂ - y₁ | ` Where y₂ is the most recent result and y₁ is the previous result. | For a direct, simple estimate of performance change over one calibration cycle. |

| Drift Between Different Reference Values [7] | Calculates the difference in the instrument's error when the calibrated reference values differ between reports. | `D = | (yi₂ - yref₂) - (yi₁ - yref₁) | ` Where yi is the instrument reading and yref is the reference value. | When the standard or reference values on calibration certificates are not identical. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Calibration

| Reagent / Material | Function in Calibration |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides a traceable, known value to establish the accuracy and scale of the instrument's response [6]. |

| Reagent Blank | Serves as a baseline reference to account for signals from the cuvette, reagents, or environment, isolating the analyte's signal [6]. |

| Internal Quality Control (IQC) Materials | Independent materials used to verify the continued validity of the calibration curve between formal recalibrations [6]. |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Detection and Management

Protocol 1: Implementing a Control Chart for Drift Detection This methodology is used to proactively monitor the performance of analytical instruments like optical emission spectrometers.

- Selection: Choose at least three certified reference standards that represent key analytical ranges for your work.

- Establish a Baseline: Under stable, optimal conditions, perform multiple measurements of these standards to establish a baseline mean and control limits (e.g., ±2 standard deviations).

- Routine Monitoring: At a predefined frequency (e.g., daily or weekly), measure the standards and plot the results on the control chart.

- Interpretation: If a standard's measurement shows a run of several points on one side of the mean or a point outside the control limits, it indicates the instrument is drifting and requires investigation [1].

Protocol 2: Robust Multi-Point Calibration A minimal two-point calibration is often insufficient to ensure reliability. This protocol enhances accuracy.

- Blank Measurement: First, run the reagent blank to establish a baseline signal [6].

- Calibrator Measurement: Measure at least two calibrators with different concentrations, covering the analytical range, in duplicate. The use of replicates accounts for measurement uncertainty [6].

- Curve Construction: Construct a calibration curve using linear regression or a more complex model suitable for the instrument's response.

- Verification: Analyze independent quality control materials to verify the calibration before running unknown samples. Calibration should be performed after any major instrument maintenance or reagent lot change [6].

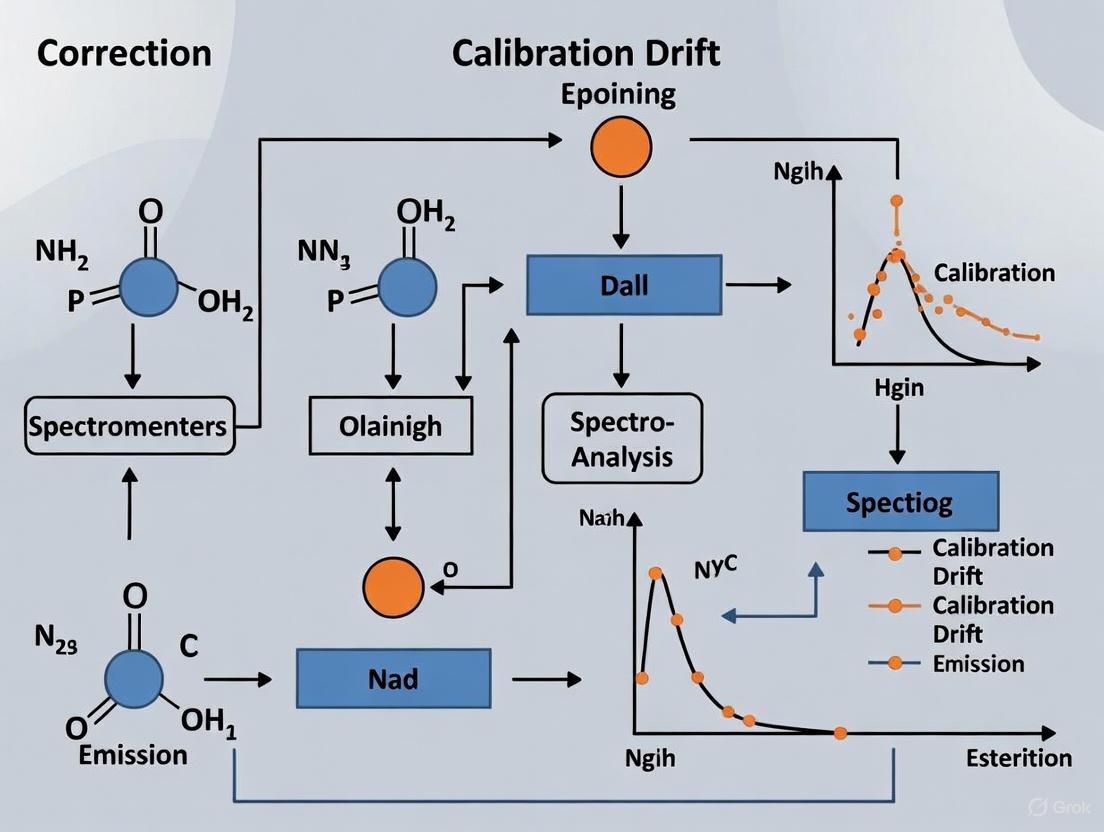

Workflow Diagrams for Drift Management

Drift Detection Workflow

Drift Causation Diagram

Calibration drift is a gradual change in instrument sensitivity that can distort results from your Optical Emission Spectrometer (OES). For researchers and scientists, understanding and mitigating drift is critical for ensuring the precision and accuracy of elemental composition analysis, which directly impacts data integrity in fields from drug development to materials science. Drift originates from a complex interplay of environmental, component, and operational factors. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help you identify specific drift sources and implement effective correction protocols within your research.

The following table summarizes the primary culprits of calibration drift, their impact on measurement uncertainty, and proven correction strategies based on current research.

Table 1: Environmental, Component, and Operational Sources of Drift

| Source Category | Specific Stressors | Impact on Measurement | Effective Correction Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Factors | Temperature Fluctuations [8] [9] [5] | Alters sensor materials/electronics; causes physical expansion/contraction. RMSE of 5.9 ± 1.2 ppm reported in CO2 sensors [8]. | Implement temperature stabilization; use instruments with automated environmental compensation [9] [10]. |

| Humidity Variations [5] | Causes condensation (short-circuiting, corrosion) or desiccation of sensor elements. | Use protective housings; deploy desiccants; regular calibration for local climate [5]. | |

| Particulate Accumulation (Dust) [5] | Obstructs sensor surfaces, altering exposure to air and skewing readings. | Implement regular cleaning schedules; use protective filters or housings [5]. | |

| Component-Related Factors | Aging Light Sources [8] | Long-term drifts producing biases up to 27.9 ppm over 2 years in NDIR sensors [8]. | Apply linear interpolation drift calibration; schedule periodic component replacement [8]. |

| Contaminated Optical Planes [9] [10] | Skews results by interfering with light path and sensitivity. | Perform regular visual inspections and cleaning of optical components [9]. | |

| Changes in Purging Gas/Vacuum Levels [9] [10] | Affects the environment within the spectrometer, altering signal intensity. | Monitor gas pressure and flow rates consistently; use high-purity gases [9]. | |

| Operational Factors | Infrequent Calibration [8] | Allows uncorrected drift to accumulate, increasing measurement uncertainty. | Maintain calibration every 3 months, not exceeding 6 months [8]. |

| Inadequate Control Samples [9] [10] | Prevents accurate detection and correction of instrument drift over time. | Use control samples with matrices closely matching process materials [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Correction

Protocol: Linear Interpolation for Long-Term Drift Correction

Background: Long-term drift, often from component aging, is a key challenge. A 30-month field study on NDIR sensors demonstrated that linear interpolation effectively calibrates long-term drift [8].

Methodology:

- Co-located Calibration: Co-locate the OES instrument with a high-precision reference analyzer for a short, initial period to establish a baseline correlation [8].

- Field Deployment: Deploy the OES for its intended research use.

- Periodic Re-calibration: Re-run the co-located calibration at recommended intervals (preferably within 3 months). Perform these calibrations during different seasons (e.g., both winter and summer) to account for seasonal drift cycles [8].

- Data Processing: Apply a linear interpolation algorithm between the periodic calibration points to correct the entire dataset. This method reduced a 30-month RMSE to 2.4 ± 0.2 ppm in a related sensor study [8].

Protocol: Advanced Drift Correction via HP ICP-OES

Background: High-Precision Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (HP ICP-OES) uses a robust drift correction procedure to achieve expanded uncertainties on the order of 0.3–1.0% [11].

Methodology:

- Standard and Sample Preparation: Prepare Standard Reference Material (SRM) solutions and unknown sample solutions. Matching the analyte mass fractions, internal standard mass fractions, and matrix compositions gravimetrically is critical [11].

- Data Acquisition: Run multiple replicates of SRM and sample solutions over the analysis period.

- Drift Modeling: Model the instrument drift by fitting an equation to the SRM measurement data over time (e.g., for Li content analysis [11]).

- Signal Correction: Apply the fitted drift correction equation to each measurement point for both standards and samples. This corrects for what was a major source of uncertainty in classical ICP-OES [11].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the most common environmental signs of calibration drift?

Answer: The most common symptoms include:

- Data Trends: Unexpected changes or inconsistencies in data trends over time without a corresponding change in the sample [5].

- Reference Mismatch: A persistent mismatch between your OES readings and values from a trusted reference instrument or control sample [5].

- Response Time: Changes in sensor response time, where the instrument becomes sluggish or erratic in its readings [5].

FAQ 2: How can I minimize drift caused by sample-to-sample variation?

Answer: Implement a rigorous schedule of control sample usage.

- Control Samples: Use control samples with a matrix and composition as close as possible to your actual process materials [9] [10].

- Frequency: Analyze these control samples at regular intervals, not just during predefined, infrequent recalibration sessions. This allows for continuous monitoring of the instrument's health and process capability [10].

FAQ 3: Our lab has stable temperature control. What else could be causing drift?

Answer: Even with stable temperatures, other factors can induce drift:

- Optical Contamination: Check for contaminated optical planes. Over time, dust or residues can accumulate, requiring cleaning [9] [10].

- Gas Supply: Verify the stability and purity of your purging gas or the vacuum level, as changes here can skew results [9] [10].

- Component Aging: Instruments are susceptible to long-term drift from the natural aging of internal components, such as the light source. This necessitates a long-term drift correction strategy [8].

System Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying and correcting the primary sources of calibration drift, integrating the protocols and strategies discussed.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Drift Management

| Item | Function in Drift Management | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) | Provides NIST-traceable benchmarks for calibrating the spectrometer and quantifying drift [11]. | Essential for HP ICP-OES protocols; matrix-matching to samples improves accuracy [11]. |

| Control Samples | Acts as a process control to verify the OES remains calibrated for specific sample types between formal recalibrations [9] [10]. | Should be homogeneous and have a composition close to the analyzed process materials [10]. |

| High-Purity Purging Gases | Maintains a stable, contaminant-free environment within the optical chamber of the spectrometer [9] [10]. | Fluctuations in purity or pressure can be a source of operational drift [9]. |

| Non-Absorbing Matrix Materials (e.g., KBr) | Used for sample dilution to minimize spectral artifacts like specular reflection in techniques like DRIFTS [12]. | Improves signal quality and quantitative reliability, indirectly supporting stable calibration [12]. |

| Optical Cleaning Supplies | For maintaining uncontaminated optical planes, which is critical for consistent sensitivity and signal intensity [9]. | Regular cleaning is a primary preventative maintenance step [5]. |

The Critical Role of Control Samples and Calibration Curves in Drift Detection

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Identifying and Correcting Drift in OES Measurements

Problem: Your Optical Emission Spectrometer (OES) shows inconsistent results when analyzing the same sample over time, suggesting potential instrument drift.

Background: Spark OES instruments are extremely sensitive to detect low concentration levels, but this makes them subject to environmental parameters over the mid to long term, causing results to 'drift' and reducing accuracy [13]. Drift can manifest as gradual changes in intensity readings or shifts in calibration curves.

Investigation Steps:

- Measure Control Samples: The most reliable method to detect drift is by regularly measuring control samples—samples of known composition that are similar to your production materials [13].

- Check Calibration Status: Verify that both detector (dark current) and instrument (wavelength) calibrations have been performed recently and successfully [14].

- Review Historical Data: Compare current control sample readings (average and standard deviation) against values established when the instrument was known to be in control [15].

Resolution Steps:

- Recalibrate the Instrument: If control sample measurements show significant deviations from established values, perform a full recalibration using Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [15] [13].

- Use Type Standardization: If inaccuracies persist only for specific, exotic alloys, perform a type standardization. This is an additional step after recalibration, using a reference material very close in composition to your problem sample [13].

- Implement a Drift Control Schedule: Establish a regular schedule for checking drift using control samples. The frequency can be based on a fixed number of analyzed samples (e.g., after every 100 products) or at regular time intervals [15].

Guide: Troubleshooting Failed Calibration Curves

Problem: Your OES instrument calibration fails, either for all wavelengths or only for specific analytical lines.

Background: Calibration establishes the relationship between the intensity of light emitted by an element and its concentration in the sample. Failures can stem from issues with the sample introduction system, the calibration standards, or the instrument itself [14].

Troubleshooting Steps:

When ALL Wavelengths Fail [14]:

- Check Sample Uptake: Ensure the pump tubing is not worn and the uptake delay time is sufficient for the solution to reach the spray chamber.

- Inspect the Nebulizer: Perform a nebulizer backpressure test. High backpressure indicates a blockage; low backpressure suggests a leak.

- Verify the Torch: Look for deposits or blockages in the torch injector tube, which can affect sample introduction.

- Confirm Solutions: Ensure calibration standards were prepared correctly and are not contaminated or unstable.

When SOME Wavelengths Fail [14]:

- Review Standards: Check for chemical incompatibilities or instability of specific elements in the calibration mix.

- Investigate Spectral Interferences: Use the software's "Possible Interferences" graph to see if other spectral lines are affecting your analysis and change wavelengths if necessary.

- Check Calibration Parameters: Ensure the correlation coefficient limits and curve fitting parameters (linear vs. rational) set in the method are realistic for the analysis.

- Examine the Blank: A contaminated blank is a common cause of failure for specific elements.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between a Certified Reference Material (CRM) and a control sample?

- CRM: A reference material with one or more property values that are certified by a recognized body. CRMs are essential for the initial calibration of the spectrometer but are expensive and often supplied in small quantities [15].

- Control Sample: A sample of known composition, often cheaper and larger than a CRM, that is used for routine checks of the spectrometer's performance. A control sample can be "linked" to the calibration curve by measuring it multiple times directly after calibration, effectively turning it into a reference sample for daily use [15].

Q2: How often should I recalibrate my OES instrument?

There is no fixed timeline. The need for recalibration should be determined by regularly measuring control samples. When the results from the control samples consistently fall outside pre-defined tolerance limits, a recalibration is necessary [15] [13]. A study on electrochemical sensors recommended semi-annual recalibration to correct for baseline drift [16], but for OES, the frequency depends on usage and the stability of the instrument.

Q3: My calibration curve was working yesterday, but today it's inaccurate. What happened?

Calibration curves can be affected by several factors that change between sessions:

- Instrument Warm-Up: The peltier cooler or polychromator may not have reached the correct operating temperature [14].

- Plasma Conditions: The torch may be misaligned, affecting sensitivity [14].

- Residual Contamination: Deposits from previous samples in the sample introduction system (nebulizer, spray chamber, torch) can alter signal response [14].

- Environmental Changes: Shifts in laboratory temperature or humidity can impact instrument performance [13].

Q4: Can I use a piece of bar stock instead of an expensive CRM to check for drift?

Yes, with proper preparation. A piece of bar stock can be used as a control sample if its composition is thoroughly determined and linked to your instrument's calibration. According to standards like DIN 51008-2, such a sample must be measured at least six times immediately after a successful calibration to link it to the calibration curve. It can then be used for routine drift checks but should not replace CRMs for the initial calibration itself [15].

Quantitative Data on Drift and Calibration

The tables below summarize empirical data on sensor drift and calibration frequencies from field studies, which can inform maintenance schedules for analytical instruments.

Table 1: Observed Drift Magnitudes in Low-Cost Sensors

| Sensor Type / Application | Observation Period | Maximum Observed Drift | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low-cost NDIR CO₂ Sensor [8] | 30 months | 27.9 ppm | Long-term sensor degradation (e.g., light source aging) |

| Low-cost NDIR CO₂ Sensor [8] | 6 months | ~25 ppm (RMSE) | Seasonal drift cycle |

| Electrochemical Gas Sensors (NO₂, NO, O₃) [16] | 6 months | ±5 ppb | Baseline drift |

| Electrochemical Gas Sensor (CO) [16] | 6 months | ±100 ppb | Baseline drift |

Table 2: Recommended Calibration Frequencies from Empirical Studies

| Analytical System | Recommended Maximum Calibration Interval | Supporting Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Low-cost CO₂ Sensor Networks [8] | 3 months (preferred), not exceeding 6 months | 30-month field evaluation; maintains accuracy within 5 ppm |

| Electrochemical Sensor Networks (NO₂, NO, O₃, CO) [16] | Semi-annual (6 months) | Long-term drift remained stable within specified bounds over 6 months |

| OES Spectrometer Drift Check [15] | After a set number of analyzed samples (e.g., every 100) | Statistical process control for quality assurance |

Experimental Protocols for Drift Assessment

Protocol: Establishing a Control Sample for OES Drift Monitoring

This protocol allows you to create a stable, in-house control sample to monitor your OES instrument's drift over time.

Key Reagent Solutions:

- Certified Reference Materials (CRMs): Used for the initial, traceable calibration of the spectrometer [15].

- Candidate Control Sample: A homogeneous material of known and stable composition, similar to your routine production samples. A piece of bar stock can be used [15].

- Solvents and Cleaning Materials: High-purity solvents for cleaning the electrode and sample surface between sparks to prevent cross-contamination.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Perform Full Calibration: Execute a complete calibration of the OES using appropriate CRMs. Ensure the calibration is stable and passes all quality checks [15].

- Measure Control Sample: Without delay, spark the candidate control sample a minimum of six times. Ensure the sample surface is properly prepared according to standard procedures [15].

- Calculate Reference Values: For each element, calculate the average intensity or concentration from the six measurements. This average becomes the "linked" reference value for your control sample [15].

- Establish Tolerance Limits: Determine acceptable tolerance limits (e.g., ±2 standard deviations) for each element based on the measured variation and your quality requirements.

- Routine Monitoring: Integrate the measurement of this control sample into your daily startup or quality control routine. Record the results on a control chart to track the instrument's performance over time.

Protocol: Correcting for Long-Term Drift in Sensor Networks

This protocol, adapted from a large-scale air sensor network study, uses statistical analysis of a sensor population to correct for drift remotely, reducing the need for frequent co-location with reference instruments [16].

Workflow Visualization:

Methodology Details:

- Preliminary Co-location: A representative batch of sensors is co-located with a reference-grade monitor. For each sensor, key calibration coefficients—sensitivity (response to target gas) and baseline (zero-output)—are calculated [16].

- Sensitivity Clustering Analysis: Calculate the sensitivity coefficients for all sensors in the batch. Analysis of over 100 sensors for gases like NO₂ showed that sensitivity values are clustered with a Coefficient of Variation (CV) of 15-22%. This high consistency supports using a population-level median value for bulk calibration [16].

- Establish Universal Parameters: Designate the median sensitivity value from the population as a universal coefficient for all sensors of that type [16].

- Remote Baseline Calibration (b-SBS Method): Apply the universal sensitivity to all sensors in the network. The baseline for each sensor is then calibrated remotely using methods like the 1st percentile of its data, which assumes periods of low pollutant concentration [16].

- Recalibration Cycle: Long-term data shows baseline drift remains stable within a narrow range (e.g., ±5 ppb over 6 months for NO₂), supporting a semi-annual recalibration frequency for maintaining data quality [16].

Assessing the Impact of Drift on Data Integrity in Pharmaceutical Analysis

In pharmaceutical analysis, calibration drift refers to the gradual deviation of an instrument's measurements from the true value over time. This phenomenon poses a significant threat to data integrity—the completeness, consistency, and accuracy of data throughout its lifecycle. For researchers using optical emission spectrometers, undetected drift can compromise the validity of analytical results, leading to incorrect conclusions about drug composition, purity, and stability.

The foundation of reliable data in regulated environments is built upon the ALCOA+ principles, which dictate that all data must be Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, Accurate, Complete, Consistent, Enduring, and Available [17] [18]. Calibration drift directly challenges the "Accurate" and "Consistent" tenets of this framework, potentially rendering entire datasets unsuitable for regulatory submissions.

Understanding Calibration Drift

What is Calibration Drift?

Calibration drift is a gradual change in the measurement accuracy of an instrument over time, resulting from factors such as component aging, environmental changes, or routine wear and tear [19]. In optical emission spectrometers, this may manifest as baseline shifts, sensitivity changes, or altered wavelength accuracy, ultimately affecting the reliability of spectral data used for pharmaceutical analysis.

Common Causes of Drift in Spectroscopic Instruments

The causes of calibration drift in optical emission spectrometers are multifaceted. Key factors include:

- Environmental fluctuations: Changes in temperature, humidity, and pressure can affect instrumental response [20] [19].

- Component aging: Degradation of light sources, detectors, and optical components occurs naturally over time [20].

- Mechanical instability: Vibration or misalignment of optical elements can lead to progressive performance decline [20].

- Source parameter changes: Variations in beam splitter parameters and interferometer tuning systems contribute to baseline instability [20].

FAQs on Drift and Data Integrity

Q1: How does calibration drift specifically impact data integrity in pharmaceutical analysis? Calibration drift directly compromises multiple ALCOA+ principles. It affects Accuracy by producing systematically biased results, undermines Consistency by creating variation over time, and threatens Complete data when drift necessitates exclusion of affected results. In severe cases, drift can impact Attributable data if the timing of the drift onset is unclear. For spectroscopic analysis, this may mean incorrect quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients or failure to detect impurities [17] [18] [19].

Q2: What are the early warning signs of calibration drift in optical emission spectrometers? Early indicators include: (1) Progressive baseline shifts in spectral measurements; (2) Gradual changes in system suitability test results; (3) Increased correction factors needed to maintain accuracy; (4) Higher variance in quality control samples; and (5) Trends in control chart data showing systematic directional movement [20] [19].

Q3: How often should calibration verification be performed to detect drift? Verification frequency should be risk-based, considering the instrument's criticality, stability history, and environmental conditions. For high-criticality spectrometers in pharmaceutical analysis, verification should occur between scheduled calibrations [21]. Statistical trend analysis of performance data should inform the specific frequency, with some instruments requiring verification as often as weekly, while others may maintain stability for longer periods [3] [19].

Q4: What is the difference between calibration, verification, and validation in this context?

- Calibration: Comparing instrument readings against traceable reference standards and making adjustments to restore accuracy [21].

- Verification: Confirming the instrument continues to perform within specified tolerances without making adjustments [21].

- Validation: Proving the entire analytical system (including sample preparation, measurement, and data processing) consistently delivers results meeting predefined requirements for its intended use [21].

Q5: What data integrity risks emerge from undetected calibration drift? Undetected drift creates multiple risks: (1) Incorrect release decisions for drug products; (2) Faulty stability studies leading to inaccurate shelf-life determinations; (3) Compromised method transfer between laboratories; (4) Regulatory citations for data integrity violations; and (5) Invalidated clinical trial results based on inaccurate analytical data [17] [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing Drift-Related Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Causes | Investigation Steps | Immediate Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive baseline upward drift | - Detector aging- Source intensity decline- Environmental temperature changes | 1. Review environmental monitoring data2. Check source usage hours3. Perform detector response test | 1. Control laboratory temperature2. Establish new baseline reference3. Increase calibration frequency |

| Increasing variance in replicate measurements | - Wavelength instability- Source flicker- Electronic noise | 1. Examine power supply stability2. Check grounding connections3. Perform noise spectrum analysis | 1. Ensure proper grounding2. Replace unstable components3. Use signal averaging |

| Gradual sensitivity loss | - Optical surface contamination- Fiber optic degradation- Source output decline | 1. Inspect optical path2. Measure source output3. Check alignment | 1. Clean optical components2. Establish new calibration curve3. Adjust integration time |

| Shifting peak positions | - Wavelength calibration drift- Temperature-induced refractive index changes | 1. Verify with reference standards2. Correlate with temperature data3. Check instrument calibration history | 1. Recalibrate wavelength2. Implement temperature control3. Use internal standards |

Correcting Baseline Drift in Spectral Data

For correcting baseline drift in spectroscopic data, the Non-sensitive area baseline automatic correction method based on weighted penalty least squares (NasPLS) has demonstrated effectiveness [20]. This method specifically addresses limitations of earlier algorithms in handling low signal-to-noise ratio environments.

Experimental Protocol for NasPLS Baseline Correction:

- Identify non-sensitive regions: Locate spectral regions where the target analyte shows zero absorbance, providing baseline reference points [20].

- Initialize parameters: Set initial weights for the penalized least squares algorithm based on signal characteristics.

- Iterative fitting:

- Compute the fitted baseline using weighted penalty least squares

- Update weights based on differences between the original spectrum and fitted baseline

- Give lower weight to points containing peak signals

- Convergence check: Continue iteration until the root mean square error between successive baseline estimates is minimized [20].

- Baseline subtraction: Subtract the fitted baseline from the original spectrum to obtain the corrected data.

This method has shown superior performance compared to AsLS, AirPLS, and ArPLS algorithms, particularly for spectra with complex baselines and varying signal-to-noise ratios [20].

Experimental Protocols for Drift Assessment

Monitoring Calibration Drift Over Time

Objective: To systematically monitor and quantify calibration drift in optical emission spectrometers used for pharmaceutical analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Optical emission spectrometer

- Certified reference materials (traceable to national standards)

- Environmental monitoring equipment (temperature, humidity sensors)

- Data collection software with statistical capabilities

- Control charts for trending results

Methodology:

- Establish baseline performance: Measure certified reference materials daily for 10 consecutive days to establish baseline instrument performance.

- Implement continuous monitoring:

- Analyze quality control samples with each analytical batch

- Record system suitability parameters before each analysis session

- Document environmental conditions throughout operation

- Statistical analysis:

- Calculate moving averages of key performance metrics

- Perform trend analysis using control charts with statistical limits

- Apply Western Electric Rules to identify non-random patterns

- Drift quantification:

- Compute rate of change for critical parameters

- Correlate drift with environmental factors and usage patterns

- Determine clinical or analytical significance of observed drift

Interpretation: Significant drift is indicated when metrics show statistically significant directional trends over time, exceeding predefined thresholds based on analytical tolerance requirements [3] [19].

Detection System for Calibration Drift

Advanced drift detection employs dynamic calibration curves maintained through online stochastic gradient descent with Adam optimization. This system:

- Processes observations in temporal order

- Adapts to changing calibration states

- Provides real-time performance assessment

- Triggers alerts when significant drift is detected [3]

The system uses an adaptive sliding window (Adwin) implementation to identify statistically significant increases in calibration error, providing actionable alerts with information on recent data appropriate for model updating [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Drift Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | ISO 17025 certified, traceable to national standards | Provides absolute accuracy benchmark for detecting and quantifying drift |

| Wavelength Calibration Standards | Holmium oxide solution or similar certified materials | Verifies wavelength accuracy and detects spectral shift drift |

| Stable Control Samples | Matrices similar to analytical samples with known characteristics | Monitors system performance and detects sensitivity changes over time |

| Intensity Calibration Standards | NIST-traceable radiant intensity standards | Quantifies changes in detector response and source intensity |

| Baseline Correction Algorithms | NasPLS, ArPLS, or similar advanced computational methods | Corrects for baseline drift in spectral data during processing [20] |

Workflow Diagrams

Drift Detection and Management Workflow

Data Integrity Assurance Process

Advanced Detection Methods

Algorithmic Approaches to Drift Detection

Modern drift detection employs sophisticated computational methods:

Dynamic Calibration Curves with Adaptive Updates:

- Utilizes online stochastic gradient descent with Adam optimization

- Maintains evolving logistic calibration curves that adapt to changing instrument performance

- Processes observations in temporal order, stepping coefficients toward newly optimal values

- Implements adaptive sliding windows (Adwin) to detect significant increases in calibration error

- Provides actionable alerts with windows of recent data appropriate for model updating [3]

Statistical Process Control Integration:

- Implements control charts with statistical limits for key performance parameters

- Applies Western Electric Rules to identify non-random patterns indicating drift

- Uses trend analysis to distinguish between random variation and systematic drift

- Incorporates measurement uncertainty calculations to assess significance of observed changes [19]

Quantitative Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Calculation Method | Acceptance Criteria | Regulatory Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Stability Index | RMSD of baseline from reference over time | < 2% change per analysis cycle | FDA data integrity guidance |

| Sensitivity Drift Rate | Slope of response curve for reference materials | < 1.5% per month | ICH Q2(R1) validation requirements |

| Wavelength Accuracy Shift | Deviation from certified wavelength standards | < 0.1 nm from established baseline | Pharmacopeial requirements |

| Reproducibility Variance | Coefficient of variation for replicate measurements | CV < 2% for consecutive batches | GMP manufacturing standards |

Corrective and Preventative Calibration Strategies: From Standards to Automation

In Optical Emission Spectrometry (OES), calibration is the process of establishing a relationship between the intensity of light emitted by an element and its concentration in a sample. This is essential because the instrument measures relative light intensities, not absolute concentrations [13] [22]. The underlying principle, Kirchhoff's Law, states that atoms and ions can only absorb the same energy that they emit, meaning they absorb and emit light at the same characteristic wavelengths [23]. Each element emits a unique set of spectral lines when excited in a plasma, and the intensity of these lines is proportional to the element's concentration, forming the basis for quantitative analysis [22].

Calibration drift—the gradual deviation from the original calibration curve over time—is a critical challenge. This occurs due to the extreme sensitivity of spark spectrometers, which makes them subject to environmental parameters, leading to reduced accuracy in the mid to long term [13]. Regular recalibration is therefore necessary to maintain analytical precision.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Calibration Issues and Solutions

This section addresses frequently encountered problems related to calibration in OES.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Why is my calibration for low-concentration elements inaccurate? Accurate low-level calibration requires building the calibration curve using standards with concentrations close to the expected sample levels and the detection limit. Using high-concentration standards in the same curve can dominate the regression statistics, making the curve insensitive to errors at low concentrations and leading to significant inaccuracies [24].

How often should I recalibrate my OES instrument? There is no single fixed schedule; the need for recalibration should be data-driven. The most reliable method is to regularly measure control samples (samples of known composition similar to your production material). Deviations in the results from these known values indicate that recalibration is necessary [13].

My calibration standards are correct, but results are still inaccurate. What should I check? Several instrumental factors can cause this. First, check the vacuum pump, as a malfunction can cause low wavelengths (essential for elements like Carbon, Phosphorus, and Sulfur) to lose intensity, leading to incorrect values [25]. Second, inspect and clean the optical windows in front of the fiber optic and in the direct light pipe, as dirt on these surfaces can cause analysis drift and poor results [25]. Finally, ensure that the lens on the probe is properly aligned to collect an adequate and intense light signal for accurate measurement [25].

What is the difference between a full recalibration and a type standardization? A full recalibration is the fundamental process of establishing the concentration-to-intensity relationship using certified reference materials [13]. Type standardization is an additional, fine-tuning step used when analyzing exotic alloys that are slightly different from the calibration matrix, or when the sample structure doesn't perfectly match the reference material. It is not an alternative to basic calibration and must be performed after a recalibration. Importantly, a type standardization is only valid for unknown materials that are very similar in composition to the standardization sample itself [13].

Troubleshooting Table: Symptoms, Causes, and Actions

The following table summarizes common calibration-related problems and how to address them.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low results for C, P, S | Malfunctioning vacuum pump purging optic chamber [25] | Monitor pump for noise, heat, oil leaks; check low-element readings [25] |

| General analysis drift, poor results | Dirty optical windows on fiber optic path or light pipe [25] | Clean optical windows as part of regular maintenance [25] |

| Low light intensity, inaccurate readings | Misaligned lens on the analysis probe [25] | Train operators to perform simple lens alignment checks and fixes [25] |

| Unstable or inconsistent analysis results | Contaminated argon gas or contaminated sample surface [25] | Ensure argon purity; re-grind samples with new pad, avoid touching sample or quenching [25] |

| High variation between tests on same sample | Instrument requires recalibration [25] | Recalibrate using a flat-prepared sample; analyze first standard 5x; RSD should not exceed 5 [25] |

| White/milky appearance of burn | Contaminated argon gas [25] | Check argon source and purity; ensure sample surface is properly prepared and not contaminated [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosing and Correcting Calibration Drift

Workflow for Calibration Verification and Correction

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for monitoring calibration performance and executing corrective actions.

Protocol: Establishing a Low-Level Calibration Curve for Trace Analysis

Objective: To create a calibration curve optimized for accurate quantification of trace elements near the method's detection limit [24].

Principles:

- Error Dominance: In a wide calibration range, the absolute error of high-concentration standards dominates the regression fit of the calibration curve. This can make the curve insensitive to variations at low concentrations, leading to poor accuracy for trace elements [24].

- Contamination Sensitivity: Contamination in the calibration blank or low-level standards has a disproportionately large effect on results for trace analytes [24].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define the Analytical Range: Determine the expected concentration of the target element(s) in your samples and the required reporting limit.

- Select Calibration Standards: Prepare a blank and at least three calibration standards. The concentrations of these standards should bracket the expected sample concentrations and the reporting limit. For example, if the reporting limit is 0.1 ppb and samples are expected below 10 ppb, suitable standards might be 0.5, 2.0, and 10.0 ppb [24]. Avoid including a very high-concentration standard (e.g., 100 or 1000 ppb) in this curve.

- Ensure Blank Purity: Meticulously prepare the calibration blank to minimize contamination from reagents, the introduction system, or the environment. The blank signal should be significantly lower than the signal from your lowest standard [24].

- Analyze Standards and Construct Curve: Analyze the blank and standards and use the data to construct the calibration curve. The correlation coefficient (R²) should not be the sole criterion for acceptance; verify the accuracy by analyzing an independent, low-concentration control standard.

- Verify Linear Range: If analyzing samples that may have higher concentrations, perform a linear range study by analyzing a higher-concentration standard against the low-level curve. The linear range is typically the highest concentration that recovers within 90-110% of its true value [24].

Protocol: Statistical Evaluation of a Multipoint Calibration Curve

Objective: To determine whether a linear calibration curve should be forced through the origin (y-intercept = 0) or not, based on regression statistics [26].

Principles:

- Forcing a curve through the origin when the y-intercept is statistically non-zero can introduce significant errors, especially at low concentrations [26].

- The decision is based on comparing the calculated y-intercept to its standard error.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Run Calibration Standards: Analyze a set of calibration standards across the desired concentration range.

- Perform Linear Regression: Use data analysis software (e.g., Excel's Data Analysis toolpack) to perform a linear regression of instrument response (y) versus concentration (x). Obtain the key regression statistics: y-intercept and standard error of the y-intercept [26].

- Statistical Test: Apply the following test:

- If the absolute value of the y-intercept is less than the standard error of the y-intercept, it is statistically valid to force the curve through the origin [26].

- If the absolute value of the y-intercept is greater than the standard error of the y-intercept, the curve should not be forced through the origin, and the calculated y-intercept should be used in the calibration equation [26].

- Evaluate Error: Using the incorrect model (e.g., forcing through zero when not appropriate) can result in large percentage errors for the lowest concentration standards, severely impacting data quality at the trace level [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents required for reliable OES calibration and maintenance.

| Item | Function | Technical Specification & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | For initial calibration and recalibration; provides known concentration values to establish the analytical curve [13]. | Must be traceable to national standards (e.g., NIST). Matrix and structure should match production samples as closely as possible for accurate results [13]. |

| Control Samples | For daily verification of calibration stability; monitors for instrument drift [13]. | Should be a homogeneous, stable material with a known composition that is similar to routine production samples. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Used to create a stable plasma environment and purge the optical path to prevent interference from atmospheric gases [25] [22]. | Contamination in argon causes unstable burns and inconsistent results. Purity is critical for exciting elements with low wavelengths like Carbon and Phosphorus [25]. |

| Sample Preparation Tools | To create a clean, representative, and flat surface for analysis, minimizing contamination and ensuring a good seal with the probe [25]. | Includes grinders, abrasive belts, or milling machines. Using a new grinding pad for each sample type prevents cross-contamination [25]. |

| Optical Cleaning Supplies | To maintain the clarity of optical windows and lenses, ensuring maximum light throughput for accurate intensity measurement [25]. | Specialized lens tissue and solvents that clean without scratching or leaving residues. Dirty optics cause analysis drift and poor results [25]. |

| Single- & Multi-Element Standard Solutions | Used for specific calibration tasks, especially in ICP-OES, to test instrument performance or create custom calibration curves [27]. | High-purity solutions (e.g., 99.999%) from reputable suppliers ensure accurate and reliable calibrations [27]. |

Implementing Internal Standard Calibration to Compensate for Signal Variability

Internal Standard Fundamentals

What is an internal standard and how does it correct for signal variability?

An internal standard (IS) is a chemical substance added at a known, constant concentration to all calibration standards, quality control samples, and unknown study samples at an early stage of analysis [28] [29]. Instead of using the absolute peak area of the target analyte for quantification, the calibration is based on the response ratio of the analyte to the internal standard [28] [29]. This ratio helps correct for random and systematic errors that may occur during sample preparation or analysis.

The core principle is that any variations affecting the analyte will similarly affect a properly chosen internal standard, making their ratio constant despite these fluctuations [28]. This compensates for volumetric losses during multi-step sample preparation, instrumental drift, and matrix effects that alter analytical signal intensity [30] [31] [29].

When should I use an internal standard in my analysis?

Internal standardization is particularly beneficial in the following scenarios [29]:

- Complex sample preparation: Methods involving multiple transfer steps, liquid-liquid extraction, evaporation, or reconstitution, where volumetric losses are likely.

- Sample-specific matrix effects: When analyzing complex sample matrices (e.g., biological fluids, environmental samples) that can cause signal suppression or enhancement.

- Long analytical runs: To correct for instrumental signal drift over time.

- Regulated bioanalysis: Following guidelines like the FDA M10 Bioanalytical Method Validation, which recommend internal standards, particularly stable isotope-labeled (SIL) compounds, for LC-MS/MS applications [32].

Internal standards may not be necessary for simple dilution-based methods with minimal preparation steps, where modern autosamplers provide excellent injection volume precision [29].

Implementation Guide

How do I select an appropriate internal standard?

Selecting an effective internal standard is critical for accurate correction. The table below summarizes the key selection criteria.

Table 1: Internal Standard Selection Criteria

| Criterion | Requirement | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Nature | Structurally similar analogue or, ideally, a stable isotope-labeled (SIL) version of the analyte [32] [33]. | Ensures the IS behaves similarly to the analyte during sample preparation and analysis [29]. |

| Absence in Sample | Must not be present or must be at negligible levels in the sample matrix [34] [31]. | Prevents overestimation of the IS concentration and incorrect ratio calculations. |

| Chromatographic Resolution | Must be well-resolved from the analyte and all other sample components [28]. | Allows for accurate integration of both analyte and IS peaks without interference. |

| Spectral Purity | Should have no spectral interferences with the analyte, and no matrix components should interfere with the IS [34] [31]. | Crucial for ICP-OES and MS detection to ensure a clean signal. |

| Similar Concentration | Added at a concentration similar to the expected analyte concentration [28]. | Ensures the response factor is within a similar order of magnitude. |

For ICP-OES analysis, additional considerations include matching the internal standard's viewing mode (axial or radial) and the type of emission line (atomic or ionic) to that of the analyte for effective correction [31] [35].

What is the step-by-step workflow for implementing internal standard calibration?

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for implementing an internal standard from method setup to data acquisition.

What are the essential reagents and materials needed?

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Internal Standard Calibration

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Internal Standard | A chemically pure compound, ideally stable isotope-labeled (SIL), used for signal correction. Must be absent from the sample matrix. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled (SIL) Analytes | Isotopically pure reference standards used for both quantification and as ideal internal standards due to nearly identical chemical behavior [32] [33]. |

| Ionization Buffer (for ICP-OES) | An solution containing an easily ionized element (e.g., Cs, Li) added to all samples to minimize ionization interferences from the matrix [31] [35]. |

| Internal Standard Mixing Kit | An automated system (e.g., a Y-connection and pump tube) for online addition of the internal standard, ensuring consistent concentration [31]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Matrix-matched standards with certified analyte concentrations used for method validation and verifying accuracy [34]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Why is my internal standard response highly variable, and how can I fix it?

Internal standard response variability (ISV) can originate from multiple sources. Investigating the pattern of variability is key to identifying the root cause [32]. The following decision tree guides you through this investigation.

How do I handle samples that are above the calibration curve when using an internal standard?

This is a common challenge because simple dilution after IS addition is ineffective; diluting the sample dilutes both the analyte and the IS, leaving their ratio unchanged [30]. The following table outlines proven strategies.

Table 3: Strategies for Analyzing "Over-Curve" Samples with Internal Standards

| Strategy | Protocol | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Dilute Before IS Addition | Dilute the original sample with blank matrix before adding the internal standard [30]. | Requires sufficient sample volume and blank matrix. Must be validated. |

| Increase IS Concentration | Add a higher concentration of IS to the undiluted sample to effectively lower the analyte-to-IS ratio [30]. | Must ensure the new IS concentration is within the linear range and is validated. |

| Use a Custom Calculation | Manually calculate the concentration based on the analyte's response factor and the known amount of IS recovered, if the software allows [36]. | Bypasses the calibration curve. Requires careful documentation. |

| Extend Calibration Range | Validate the method with a calibration curve that extends to higher concentrations to encompass potential over-curve samples [30]. | The most straightforward solution if detector sensitivity and linearity allow. |

Important: Any procedure for handling over-curve samples must be demonstrated to work accurately during method validation and be clearly documented in the analytical method [30].

Why are my accuracy and precision poor even with an internal standard?

If an internal standard is used but data quality remains poor, the fundamental assumption of proper IS tracking is likely violated. Use the following checklist:

- Verify IS Addition Technique: Check the pipette or automated system used to add the IS for accuracy and precision. An out-of-calibration pipette is a common culprit [29].

- Assess IS Trackability: The IS may not be tracking the analyte adequately due to differing physico-chemical properties. Evaluate this during method development using an IS-normalized matrix factor or a parallelism experiment with serial dilution of study samples [32].

- Check for Pre-Addition Issues: The internal standard cannot correct for problems that occur before it is added, such as inhomogeneous original samples or incomplete extraction [29].

- Review Data Evaluation: For ICP-OES, ensure the precision of internal standard replicates is good (RSD < 2-3%). Poor replicate precision can indicate mixing issues or other problems that lead to incorrect results [31].

Advanced Applications & Methodologies

What is multi-internal standard calibration (MISC)?

Multi-internal standard calibration (MISC) is an emerging approach that uses multiple internal standard species with a single calibration standard to provide a generalized correction for signal fluctuations [34]. This is particularly useful in techniques like ICP-OES for multi-analyte determination where finding a single ideal IS for all analytes is challenging.

In MISC, a calibration plot is constructed where each point corresponds to the analyte signal divided by the signal of a different IS species (e.g., different elements or argon lines) [34]. This method has shown performance comparable to traditional external calibration (EC) and single internal standard (IS) methods while requiring only a single standard solution, thereby increasing throughput and reducing waste [34].

How does internal calibration with a stable isotope-labeled (SIL) standard work?

Internal calibration is an innovative approach where a stable isotope-labeled (SIL) standard of the analyte is used as the internal standard in a "one-standard" calibration [33]. The method relies on the stability of the analyte-to-SIL response factor (RF). Once the RF is established, quantification of the endogenous analyte in unknown samples can be achieved by measuring the analyte-to-SIL peak area ratio, as the concentration of the added SIL is known [33]. This approach can be faster and less prone to error than preparing full external calibration curves. The naturally occurring isotopes of the SIL can also be monitored to provide additional calibration points for low-concentration analytes [33].

Standard Additions Method for Complex Biomedical Sample Matrices

Core Concept: Overcoming Matrix Effects

The standard additions method is a quantitative analysis technique used to overcome matrix effects in complex samples, where interfering substances within the sample alter the instrument's response, leading to inaccuracies [37]. This is particularly critical in biomedical analysis, where samples like blood plasma, urine, or tissues contain numerous components that can suppress or enhance analyte signals [38]. The method involves adding known amounts of the analyte directly to the sample, allowing for accurate determination of the original analyte concentration while compensating for the matrix's influence [39] [37].

When to Use Standard Additions

This method is essential when:

- A blank matrix is unavailable for preparing traditional calibration standards [40] [38].

- The sample matrix is complex, variable, or unknown [37] [41].

- Analyte recovery is low due to matrix-induced signal suppression or enhancement [38].

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Implementing the standard additions method for a liquid biomedical sample (e.g., plasma or urine) involves the following workflow. The entire process, from sample preparation to calculation, is summarized in the diagram below.

Workflow for Standard Additions

Step 1: Preparation of Test Solutions

- Accurately split the sample into a series of equal-volume aliquots [37] [41]. For a multiple-point addition, 4-5 aliquots are typical [40].

- Leave one aliquot as the unspiked sample (the control).

- Spike the remaining aliquots with increasing, known volumes of a standard solution containing the analyte at a known concentration (

C_s) [37]. A common practice is to spike such that the added analyte concentration reaches between 1x and 3x the estimated unknown concentration (x?) [41]. - Volume Correction: If the spiking volumes are significant (e.g., >1% of the sample volume), an equal volume of solvent should be added to the unspiked sample to cancel out dilution errors [41].

- Internal Standard: If used for monitoring instrument stability, add the same precise amount of internal standard to all aliquots, including the unspiked sample and calibration standards [31].

Step 2: Sample Analysis and Data Collection

- Process all prepared aliquots (unspiked and spiked) through the full analytical method, including any extraction, digestion, or chromatographic separation [39] [38].

- Measure the instrument response (e.g., spectroscopic intensity, chromatographic peak area) for each solution [37].

Step 3: Data Analysis and Calculation

- Plot the Data: Create a graph with the instrument response on the Y-axis and the concentration of the added standard on the X-axis [37] [40].

- Perform Linear Regression: Fit a straight line through the data points. The equation of the line will be in the form

y = mx + b, wheremis the slope andbis the y-intercept [37] [40]. - Calculate the Unknown Concentration (

C_x): The unknown concentration is determined by the absolute value of the x-intercept (wherey=0). This can be calculated using the formula:C_x = |b / m|[40].

For a single-point standard addition, the calculation can be simplified to:

C_x = (S_x * C_s * V_s) / (S_s * V_x)

Where S_x is the signal of the unspiked sample, S_s is the signal from the added standard, C_s is the concentration of the standard, V_s is the volume of the standard added, and V_x is the volume of the sample aliquot [41].

Troubleshooting FAQs

1. My standard additions curve is non-linear. What could be the cause? Non-linearity can arise from several factors:

- Exceeding Linear Dynamic Range: The spiked concentrations may exceed the instrument's linear response range. Ensure all measurements, including the highest spike, fall within the validated linear range [41] [42].

- Chemical Effects: The analyte may interact differently with the complex sample matrix at various concentration levels, or the analyte itself may be unstable under the analytical conditions [43].

- Spectral Interferences: In techniques like ICP-OES, unresolved spectral interferences can cause non-linear behavior. It is recommended to use at least two different spectral lines for the analyte and carefully scan the spectral region [41].

2. The method is time-consuming for high-throughput labs. How can I streamline it? You can simplify the workflow without significantly compromising quality:

- Single-Point Standard Addition: During method validation, demonstrate that a single spiked sample (in addition to the unspiked) provides equivalent results to a multi-point curve. This cuts the number of preparations and analyses drastically [40].

- Post-Extraction Spiking: Instead of spiking before sample preparation, spike the analyte into the final extract. This reduces the number of full extractions needed, simplifying preparation [40].

3. The calculated concentration seems inaccurate. Where should I look for errors? Inaccuracy often stems from systematic errors in the procedure:

- Pipetting and Volumes: Inaccurate pipetting when preparing spikes or sample aliquots is a common source of error. Use calibrated pipettes and good technique [37] [41].

- Background Correction: The method assumes the instrument signal is zero when the analyte concentration is zero. Ensure all measured signals are properly background-corrected [41].

- Instrument Drift: Signal drift during analysis can affect results. For techniques like ICP-MS, drift can be pronounced. A measurement sequence that intersperses the unspiked and spiked samples (e.g., sample → spiked sample → sample → spiked sample) can help account for linear drift [41].

4. How does standard addition compare to other methods for correcting matrix effects? The table below compares common calibration techniques.

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Calibration [42] | Calibration curve prepared in a pure solvent or simple matrix. | Simple, fast, and high-throughput. | Prone to inaccuracies from matrix effects. | Simple matrices with minimal interferences. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration [42] | Calibration standards prepared in a blank matrix matching the sample. | Reduces matrix effects effectively. | A blank matrix is often unavailable for biomedical samples [38]. | Matrices that are consistent and for which a blank is available. |

| Internal Standardization [41] [31] | A known internal standard element/compound is added to all samples and standards to correct for signal variations. | Corrects for instrument drift and some sample introduction effects. | Finding a suitable internal standard that behaves identically to the analyte can be difficult; may not correct for all plasma-related effects [41]. | Multi-analyte analysis where a compatible internal standard is available. |

| Standard Additions [39] [37] | The sample itself is spiked with known amounts of the analyte. | Corrects for matrix effects without needing a blank matrix; highly accurate for complex/unknown matrices. | Time-consuming; requires more sample preparation and analysis per sample. | Complex, variable, or unknown sample matrices like biomedical fluids. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents essential for successfully implementing the standard additions method.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) [39] | To prepare the primary standard solution for spiking; to validate method accuracy. | Must be NIST-traceable and of high purity. Ensures the accuracy of the spike concentration [39]. |

| Internal Standard Solution [31] | An element or compound not native to the sample, added to correct for instrument drift and sample introduction variability. | Should not be present in the sample and must be spectrally clean. Should have similar behavior to the analyte (e.g., similar ionization energy in ICP) [41] [31]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISAB/TISAB) [44] | Used in potentiometric analysis (e.g., ion-selective electrodes) to maintain a constant ionic background and pH, ensuring measurement of ion activity, not just concentration. | The composition is ion-specific. For example, a TISAB for fluoride measurement contains CDTA, NaCl, and acetic acid [44]. |

| High-Purity Acids & Solvents [45] | For sample digestion, dilution, and preparation of standards. | High purity is critical to avoid contamination that leads to elevated blanks and inaccurate results. |

| Metaphosphate Buffer [43] | An example of a stabilization buffer. Used to preserve unstable analytes like L-ascorbic acid during analysis by reducing the oxidation rate. | The choice of stabilization agent depends on the analyte's chemical stability. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Calibration and AI Workflows

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when integrating AI and digital twins into spectroscopic calibration.

FAQ 1: My AI model for predicting spectrometer calibration performs well on training data but poorly on new data. What should I do?

This is a classic sign of overfitting. Your model has likely learned the noise in your training dataset rather than the underlying calibration relationship.

- Solution: Implement regularization techniques and simplify your model. Furthermore, ensure your training dataset is representative of the real-world conditions your spectrometer will encounter, including variations in humidity and temperature. Applying humidity correction functions, as done in methane isotope research, can be crucial for generalizable models [46].

FAQ 2: How can I create a digital twin for my optical emission spectrometer when I don't have a complete computational model of the entire system?

A full-scale model is not always necessary. Start by building a partial digital twin focused on a specific component.

- Solution: For instance, you can begin by developing a high-fidelity simulation of the detector system or the plasma source. As demonstrated in parallel NMR research, the core of a digital twin is a model that combines electromagnetic simulation with data-driven parameters to predict system behavior [47]. You can use historical calibration data to infer and model the relationships between environmental factors and calibration drift.

FAQ 3: Significant calibration drift occurs in my spectrometer when ambient humidity changes. How can I correct for this?

Spectral interference from water vapor is a known challenge for optical instruments, and it requires a robust correction strategy [46].

- Solution:

- Empirical Correction: Conduct laboratory experiments where you measure standards across a controlled range of humidity levels.

- Model the Drift: Establish an empirical correction function (e.g., linear or quadratic) that quantifies the bias introduced by water vapor.

- Apply the Correction: Integrate this function into your calibration model. For the most accurate results, an isotopologue-specific calibration that accounts for non-linear spectral effects at high concentrations has been shown to be more stable than simpler methods [46].

FAQ 4: What is the most interpretable AI model for identifying which spectral wavelengths are most important for my calibration?

While complex models like Deep Neural Networks (DNNs) are powerful, tree-based ensemble methods often provide a better balance of performance and interpretability.

- Solution: Use Random Forest (RF) or Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) models. These algorithms can output a feature importance ranking, which clearly shows which wavelengths contribute most to the predictive model, thereby preserving chemical interpretability [48].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Quality Issues for AI-Driven Calibration

Poor data quality is the most common cause of AI model failure.

- Problem: The AI model's predictions are inaccurate and unstable.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Check for Data Leakage: Ensure that no information from the test set (or future data) was used to train the model.

- Assess Data Distribution: Compare the statistical properties (mean, variance, range) of your training data against your production data. Look for significant shifts.

- Evaluate Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Visually inspect raw spectra for excessive noise or artifacts.

- Corrective Actions:

- Augment Your Data: Use Generative AI (GenAI) to create synthetic spectral data that balances your dataset and enhances calibration robustness [48].

- Implement Robust Preprocessing: Standardize preprocessing steps (e.g., normalization, baseline correction, scatter correction) across all datasets [48].

- Feature Selection: Use tree-based models (RF, XGBoost) to identify and retain only the most diagnostically useful wavelengths, reducing noise [48].

Guide 2: Diagnosing and Correcting Biases in Digital Twin Simulations

A digital twin's predictions can diverge from reality due to unaccounted-for biases.

- Problem: The digital twin's simulated outputs consistently deviate from physical experimental results.

- Diagnostic Steps:

- Identify Bias Type: Determine if the bias is constant (e.g., a fixed offset) or variable (e.g., depends on humidity or sample type).

- Validate Sub-Models: Isolate and test individual components of the digital twin (e.g., the electromagnetic field simulation, the material interaction model) against controlled experiments.

- Check Coupling Effects: As seen in parallel NMR, unwanted coupling between components can distort results. Model these inter-channel couplings explicitly [47].

- Corrective Actions:

- Calibrate with Physical Data: Use a set of real-world measurements to calibrate the parameters of your simulation model.

- Implement a Feedback Loop: Continuously feed operational data from the physical spectrometer back into the digital twin to dynamically update and correct its models.

- Apply Blind Source Separation (BSS): If the digital twin receives a composite signal from multiple detectors, use BSS methods to separate the signals and identify the source of bias, similar to the approach used in parallel NMR signal decomposition [47].

Experimental Protocols for Emerging Trends

Protocol 1: Developing a Humidity Correction Model for Spectral Drift

This protocol provides a methodology to correct for humidity-induced calibration drift, based on techniques used in high-precision methane isotope analysis [46].

Methodology:

Laboratory Experimentation:

- Expose your spectrometer to a calibrated gas or a stable solid standard in a controlled climate chamber.

- Systematically vary the water vapor concentration across a range of 0.1% to 4.0%.

- At each humidity level, record the spectral measurements of your standard.

Data Analysis and Correction Function:

- For each humidity level, calculate the bias in your measurement (δ) compared to the known value of the standard measured under dry conditions.

- Plot the bias (δ) against the water vapor concentration.

- Fit an empirical function to this data. A linear or quadratic function is commonly used to model the humidity-induced bias [46].

Integration into Calibration:

- Incorporate the empirical correction function into your standard calibration procedure.

- For future measurements, continuously monitor ambient humidity and apply the correction in real-time.

Protocol 2: Building a Digital Twin for a Spectrometer Detector Array

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a digital twin for a multi-detector system, adapting the framework developed for parallel NMR spectroscopy [47].

Methodology:

System Modeling (Electromagnetic Simulation):

- Use finite element method (FEM) software (e.g., COMSOL) to create a geometric model of your detector array.

- Define the electrical parameters (permittivity, permeability) of all materials.

- Run an electromagnetic simulation to calculate the S-parameters, which quantify the coupling between detectors, and the magnetic/electric fields for each detector under unit excitation [47].

Spin-Dynamic/Signal Simulation:

- Import the calculated EM fields into a computational environment (e.g., Python with NumPy/SciPy, or specialized packages like Spinach for NMR).

- Develop a model that simulates the core physical interaction (e.g., plasma emission, light detection) and the resulting signal generation for each detector, accounting for the inter-detector coupling from the S-parameters.

Parallel Pulse Compensation & Signal Decomposition:

- Mitigation: Design cooperative pulse or sequence patterns that actively compensate for the predicted interference between detectors during the excitation phase [47].

- Separation: Use the coupling matrix from your model, or employ Blind Source Separation (BSS) techniques, to decompose the composite signal received from all detectors into its individual components [47].

Tabulated Data and Research Materials

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI/Chemometric Models for Spectral Quantification

The following table summarizes key characteristics of common algorithms used for building calibration models, helping you select the right tool for your application [48].

| Model | Best For | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLS Regression | Linear relationships, small datasets | Robust, handles collinearity, industry standard | Assumes linearity | Medium (via loadings) |

| Random Forest (RF) | Non-linear relationships, classification | High accuracy, robust to noise, provides feature importance | Can be computationally heavy | High (feature importance) |