Combating Photodegradation in Spectroscopy: Strategies for Accurate Pharmaceutical and Material Analysis

This article addresses the critical challenge of photodegradation in spectroscopic measurements, a key concern for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to ensure data integrity.

Combating Photodegradation in Spectroscopy: Strategies for Accurate Pharmaceutical and Material Analysis

Abstract

This article addresses the critical challenge of photodegradation in spectroscopic measurements, a key concern for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to ensure data integrity. It explores the fundamental mechanisms of light-induced molecular degradation across various materials, including organic semiconductors and active pharmaceutical ingredients. The content outlines standardized methodologies for photostability testing based on ICH guidelines and advanced analytical techniques for monitoring degradation pathways. It further provides practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies, such as the use of nanocarriers and substrate engineering, to mitigate photodegradation. Finally, the article covers validation protocols and comparative analysis of techniques, emphasizing the role of multivariate analysis for robust, reliable spectroscopic data in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Photodegradation: Mechanisms, Impact, and Substrate Effects on Sample Integrity

Fundamental FAQs on Photodegradation

What is photodegradation and why is it a critical concern in pharmaceutical research? Photodegradation is the chemical change in a material, such as an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API), induced by light energy, primarily ultraviolet (UV) radiation [1]. This process often involves oxidation and hydrolysis when combined with atmospheric oxygen and moisture [1]. In drug development, it is a primary cause of irreversible deterioration, leading to loss of potency, formation of potentially harmful degradation products, and reduced shelf-life [2]. Understanding and mitigating photodegradation is therefore essential for ensuring drug safety, efficacy, and stability throughout its lifecycle.

What are the primary mechanisms of photodegradation? The three core mechanisms are:

- Photo-oxygenation: A light-induced reaction where a molecule incorporates oxygen. This is a key initiation step for subsequent degradation pathways [2].

- Chain Scission: The breaking of the main chain (backbone) of a polymer or large molecule, which directly reduces molecular weight and leads to a loss of mechanical integrity and chemical properties [2] [1].

- Ring-Opening: The cleavage of a cyclic structure within a molecule, which can destroy the core scaffold responsible for its pharmacological activity.

How does light initiate these degradation mechanisms? The process begins when a molecule absorbs a photon of light with sufficient energy to excite an electron. This creates reactive sites that can:

- Directly break chemical bonds (as in chain scission or ring-opening) [1].

- React with environmental oxygen to form highly reactive free radicals (e.g., peroxy radicals) and reactive oxygen species (e.g., hydrogen radicals,

OH•) [2] [1]. These radicals then propagate a chain reaction, abstracting hydrogen atoms from the molecule and leading to further oxidation and bond cleavage [2].

Troubleshooting Guides for Experimental Artifacts

Issue 1: Inconsistent Photodegradation Rates in Replicate Experiments

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Light Source Intensity | Measure light flux at the sample position with a calibrated radiometer for all replicates. | Use a stabilized power supply for the light source and calibrate the light source regularly. Document the intensity and wavelength for every experiment. |

| Inadequate Control of Environmental Factors | Monitor and log temperature and humidity inside the reaction chamber during photolysis. | Use an environmental chamber to maintain constant temperature and humidity. Purge the system with an inert gas like N₂ to exclude oxygen and moisture if needed [3]. |

| Variations in Sample Presentation | Ensure uniform sample thickness and container geometry (e.g., consistent pathlength of cuvettes). | Use standardized containers and ensure samples are prepared in identical matrices (solvent, concentration) for all runs. |

Issue 2: Unexpected or No Degradation Products Observed

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Wavelength | Verify the absorption spectrum of your API and the emission spectrum of your light source overlap. | Select a light source (e.g., laser at 266 nm [4]) that emits at a wavelength absorbed by the chromophores in the target molecule. |

| Presence of Unaccounted Photosensitizers | Analyze solvent and excipient purity. Run control experiments with individual components. | Use high-purity reagents. Be aware that dissolved organic matter or trace metals can act as external impurities and catalyze indirect photodegradation [2] [1]. |

| Low Photon Flux or Short Exposure Time | Calculate the theoretical photolysis efficiency based on laser power, path length, and the compound's absorption cross-section [4]. | Increase light intensity or extend exposure duration to ensure sufficient photons are delivered to drive the reaction. |

Issue 3: Challenges in Quantifying Degradation Products Spectroscopically

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Overlapping Spectral Peaks | Perform multi-wavelength analysis or use hyphenated techniques like LC-MS or GC-MS to separate co-eluting compounds. | Employ a repetitive-scan FT-IR or UV-Vis method to capture full spectra over time, helping to deconvolute complex kinetics [4]. |

| Low Concentration of Key Intermediates | Increase sample concentration or scale of the experiment to enhance signal. | Utilize a long-path gas or liquid cell (e.g., multi-pass cell) to increase the effective pathlength and boost the absorbance signal of trace products [4]. |

| Instability of Photoproducts | Monitor the spectral evolution over time to identify transient peaks that appear and then disappear. | Use fast, real-time monitoring techniques (e.g., repetitive scan FT-IR on the millisecond scale) to capture short-lived intermediates [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Mechanisms

Protocol A: Monitoring Photochemical Kinetics via FT-IR Spectroscopy

This protocol uses a system coupling a repetitive-scan FT-IR spectrometer with a UV light source to monitor gaseous or volatile photoproducts in real-time [4].

1. Apparatus Setup:

- FT-IR Spectrometer: Configure for repetitive scanning at a desired spectral resolution (e.g., 2-4 cm⁻¹).

- Multi-pass Long-Path Gas Cell: Housed within the spectrometer sample compartment. This increases the interaction pathlength, enhancing sensitivity for low-concentration gaseous species [4].

- UV Light Source: A pulsed Nd:YAG laser (e.g., fourth harmonic at 266 nm) is optically aligned to pass multiple times through the gas cell for efficient photolysis [4].

- Vacuum Line: Connected to the gas cell for precise introduction and control of the precursor vapor pressure [4].

2. Procedure: 1. Introduce the volatile precursor into the gas cell at a controlled vapor pressure. 2. Acquire a background IR spectrum of the precursor before photolysis. 3. Initiate the UV laser pulses to start the photochemical reaction. 4. Simultaneously, start the repetitive scan of the FT-IR to collect time-resolved spectra. 5. Continue data acquisition for the desired reaction time (up to 100s of ms). 6. Analyze the sequential spectra to identify new absorption bands, track their growth (products), and the decrease of precursor bands.

3. Data Analysis:

- Use the Beer-Lambert law and the known optical pathlength for quantitative analysis of precursor consumption and product formation [4].

- Estimate photolysis efficiency based on laser power, optical path-length of the laser light, vapor pressure of the precursor, and its absorption cross-section [4].

Protocol B: Investigating Aqueous Photo-oxygenation Pathways

This protocol outlines an approach for studying photodegradation in solution, relevant to drug formulations.

1. Apparatus Setup:

- Light Source: Solar simulator or specific wavelength LED/lamp (e.g., in UV-A/UV-B range).

- Reaction Vessel: Quartz or UV-transparent glass vial/cuvette.

- Agitation System: Magnetic stirrer to keep the solution homogenous.

- Analytical Instrumentation: HPLC-MS for identifying and quantifying degradation products.

2. Procedure: 1. Prepare an aqueous solution of the API, with or without potential photosensitizers (e.g., humic substances, Fe³⁺ ions) or stabilizers [1]. 2. Divide the solution into multiple vials. Keep one vial in the dark as a control. 3. Expose the experimental vials to the light source under controlled temperature and atmosphere (e.g., air, O₂, or N₂). 4. Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time intervals. 5. Immediately analyze the aliquots using HPLC-MS to track the parent compound's disappearance and the formation of photo-oxygenation products.

3. Data Analysis:

- Compare chromatograms from light-exposed samples against the dark control.

- Use mass spectrometry to identify the molecular weights and proposed structures of degradation products, looking for mass increases consistent with oxygen incorporation (+16, +32 Da).

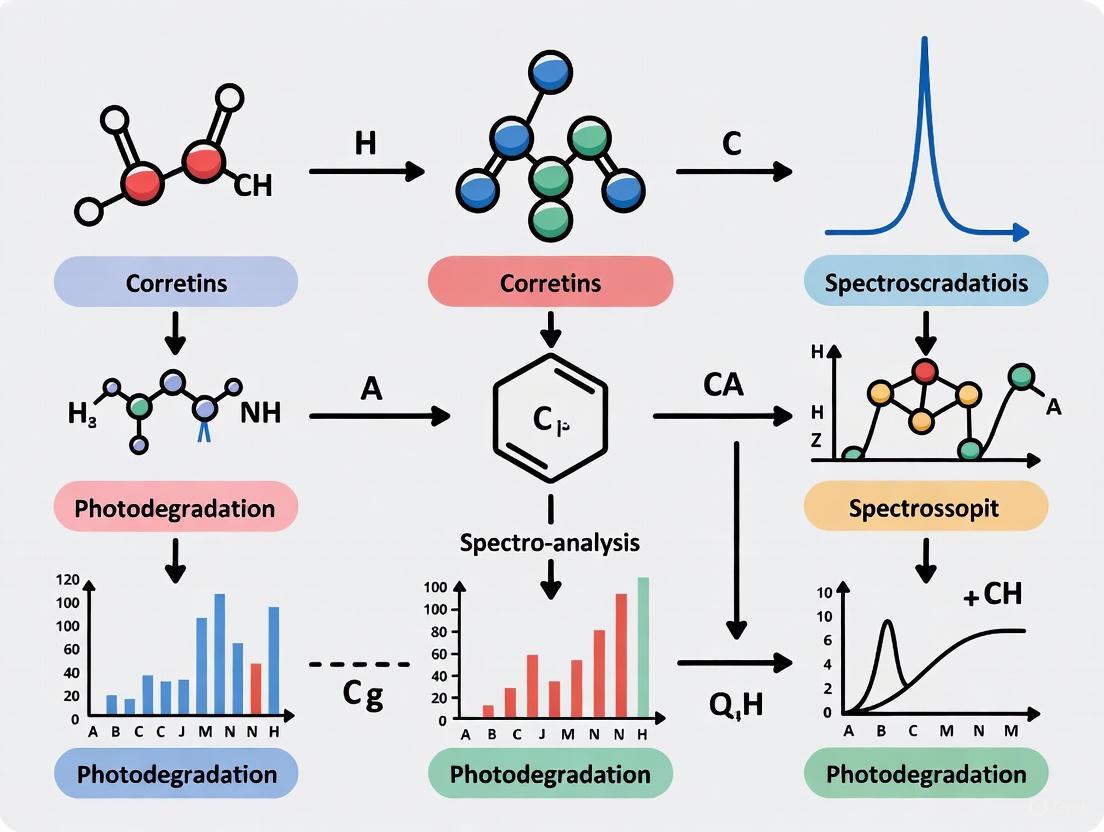

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Core Photodegradation Mechanism Pathways.

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Photodegradation Studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Stabilized Light Source (e.g., Nd:YAG Laser, LED Lamp) | Provides consistent, monochromatic UV light for controlled and reproducible photolysis experiments [4]. |

| Long-Path Gas/Liquid Cell | Increases the effective optical pathlength in spectroscopic cells, enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio for detecting low-concentration species [4]. |

| Free Radical Scavengers (e.g., BHT, Vitamin E) | Compounds that donate hydrogen atoms to stabilize free radicals; used to confirm radical-mediated degradation pathways and protect formulations [2]. |

| UV Absorbers | Organic compounds that absorb harmful UV radiation and dissipate it as heat, acting as a "sunscreen" for the API to prevent initial photon absorption [2]. |

| TiO₂ Photocatalyst | A semiconductor used to study accelerated photodegradation; upon UV excitation, it generates electron-hole pairs that produce highly reactive radicals for destructive oxidation of organics [1]. |

| Inert Atmosphere Chamber/Glovebox | Allows for the preparation and irradiation of samples in an oxygen- and moisture-free environment (e.g., N₂ or Ar), isolating photolytic from photooxidative pathways [3]. |

Photodegradation is a photo-induced process where molecules undergo chemical change upon absorbing light, primarily in the ultraviolet and visible spectra [5] [1]. In spectroscopic analysis, this presents a critical methodological challenge: the sample being measured may degrade during the analysis itself, leading to significant data artifacts. For researchers in pharmaceuticals and material science, this phenomenon directly compromises data accuracy, reproducibility, and the reliability of scientific conclusions [6] [7]. The very tool used to probe sample integrity can inadvertently alter it, creating a fundamental paradox in analytical science. This technical support center provides targeted guidance to identify, troubleshoot, and correct for photodegradation in your experimental workflows.

Understanding the Mechanisms and Impact

Fundamental Mechanisms of Photodegradation

Photodegradation occurs through direct and indirect pathways, each with distinct implications for experimental data.

- Direct Photolysis: Occurs when a target analyte directly absorbs light, leading to bond cleavage or molecular rearrangement [1]. This is common in molecules with chromophores, such as triarylmethane dyes [8] or drugs like sulfamethoxazole [9].

- Indirect Photolysis: Triggered when a photosensitizer in the sample (e.g., dissolved organic matter, catalyst residues, or impurities) absorbs light and transfers energy to the target analyte, causing its degradation [1]. This is a major pathway in complex matrices like environmental samples or biological formulations.

- Photooxidation: In the presence of oxygen, UV radiation causes photooxidative degradation, breaking polymer chains, generating free radicals, and reducing molecular weight [2]. This is a primary degradation route for polymers and many active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism leading to spectroscopic inaccuracy.

Key Factors Influencing Photodegradation Rates

The rate and extent of photodegradation are not uniform; they depend on several experimental factors. Understanding these is the first step in troubleshooting.

Table 1: Key Factors Affecting Photodegradation in Experiments

| Factor | Impact on Degradation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Light Exposure | Intensity, wavelength spectrum, and duration directly correlate with degradation rate. | ICH Q1B guidelines specify controlled light sources for drug stability testing [7]. |

| Sample Properties | Lower sample amounts can degrade faster due to a higher effective photon-to-molecule ratio [5]. Chemical structure (e.g., chromophores) determines light absorption. | |

| Environmental Conditions | Presence of oxygen accelerates photooxidation. Temperature and pH can also influence reaction rates [2]. | Melatonin hydrolysis is strongly influenced by the pH (alkaline conditions) [6]. |

| Matrix Composition | The presence of photosensitizers (e.g., humic substances, metal ions) can promote indirect photodegradation of the target analyte [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Incorporating specific reagents and materials into your experimental design can help mitigate photodegradation or study it systematically.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Photodegradation Studies and Stabilization

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Core-Waveguide (LCW) Cell | An amorphous-Teflon tubing that guides light via total internal reflection, providing a highly efficient and controlled irradiation path for online degradation studies [5]. | Embedded in a 2D-LC system to study photodegradation pathways of compounds like fuchsin and annatto [5]. |

| Lipid Nanocarriers (Liposomes, Niosomes, SLNs) | Drug delivery systems that encapsulate active compounds, protecting them from light and improving controlled release [7]. | Used to minimize photodegradation and improve the pharmacokinetic profile of NSAIDs like Ketoprofen [7]. |

| UV Absorbers & Stabilizers | Compounds that absorb harmful UV radiation or quench excited states, preventing the light energy from reaching the sensitive analyte [2]. | Added to polymer formulations (e.g., polystyrene) to prevent yellowing and embrittlement upon outdoor exposure [2]. |

| Photo-catalysts (e.g., TiO₂) | Semiconductors that generate reactive radicals (e.g., OH•) under light to deliberately degrade organic pollutants in a controlled manner [1]. | Used in advanced oxidation processes for water purification and waste treatment [1]. |

| Chemometric Software (MCR-ALS) | Multivariate Curve Resolution - Alternating Least Squares algorithms deconvolute complex spectral data to resolve pure spectra of degradation products and their concentration profiles [7] [9]. | Applied to resolve the degradation pathway of sulfamethoxazole from UV-Vis and LC-DAD data [9]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Photodegradation

Q1: My UV-Vis absorption spectra show a steady decrease in the main peak and the emergence of new peaks over repeated scans. Is this photodegradation? A: Yes, this is a classic signature of photodegradation. The decrease in the main peak indicates the loss of the parent compound, while the emergence of new peaks, often at longer wavelengths, indicates the formation of light-absorbing transformation products [6]. The isosbestic points you may observe confirm the clean conversion between chemical species [6].

- Actionable Steps:

- Reduce Exposure: Shorten the instrument integration time and use a shutter to block the beam between measurements.

- Attenuate Light: If possible, use a neutral density filter in the spectrometer's light path to reduce the intensity reaching the sample.

- Control Temperature: Perform measurements in a temperature-controlled cuvette holder, as some degradation reactions are thermally accelerated.

- Validate Linearity: Confirm that your spectral measurements are independent of light exposure time by taking rapid, successive scans and checking for overlap.

Q2: How can I definitively prove that the changes I'm seeing are from photodegradation and not another form of decomposition? A: A controlled light-exposure experiment is the most direct method. The workflow below outlines a robust protocol to confirm and characterize photodegradation.

- Protocol Details:

- Light Source: Use a well-defined light source, such as a cold-white LED lamp [5] or a monochromator for specific wavelengths [10], calibrated for irradiance.

- Control: The dark control must be kept under identical conditions (temperature, container) but shielded from all light.

- Analysis: Use a separation technique like Liquid Chromatography with a Diode-Array Detector (LC-DAD). The appearance of new peaks in the "light" chromatograms, absent in the "dark" controls, is definitive proof [5] [9].

Q3: My API is in a topical formulation and is known to be photosensitive. How can I improve its photostability? A: Incorporating the API into a protective drug delivery system is a highly effective strategy.

- Actionable Steps:

- Use Lipid Nanocarriers: Formulate the drug within liposomes, niosomes, or solid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs). These lipid-based systems act as a physical barrier, shielding the drug from incident light [7].

- Add Excipients: Incorporate approved UV absorbers (e.g., titanium dioxide) or antioxidants into the formulation matrix to scavenge reactive radicals [7] [2].

- Packaging: As a first line of defense, use opaque or amber packaging that blocks UV and visible light.

Q4: I need to study the kinetics of photodegradation and identify the products. What is a modern experimental setup for this? A: An online multi-dimensional chromatography system with an integrated photoreactor is a powerful approach.

- Methodology:

- Setup: Implement a Multiple-Heart-Cut 2D-LC system. The first dimension (¹D) separates the complex mixture, isolating a pure fraction of your compound of interest [5].

- Irradiation: The heart-cut fraction is transferred via an isocratic pump to a Liquid-Core-Waveguide (LCW) photoreactor where it is irradiated for precise time intervals [5].

- Analysis: The irradiated sample is then transferred to the second dimension (²D) for separation, resolving the parent compound from its transformation products. Coupling this to mass spectrometry (LC-DAD-MS) allows for product identification [5] [9].

- Data Processing: Apply chemometric methods like Multivariate Curve Resolution (MCR) to the spectral data to resolve the pure spectra and concentration profiles of all species, even from complex, overlapping data [7] [9].

Standard Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Forced Photodegradation Study According to ICH Q1B

This standard protocol is used in pharmaceutical development to assess the inherent photosensitivity of a drug substance or product [7].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare samples of the drug in a suitable transparent container (e.g., quartz cuvette).

- Light Source: Use a light source that combines both visible and UV outputs. Option 1 is an artificial daylight fluorescent lamp. Option 2 is a combination of a cool white fluorescent lamp and a near-UV lamp (320-400 nm) [7].

- Irradiation: Expose the sample to a total illumination of not less than 1.2 million lux hours for visible light and 200 watt hours/square meter for UV. Control the temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Control: Maintain a parallel sample wrapped in aluminum foil as a dark control.

- Analysis: At intervals, analyze both irradiated and control samples by a stability-indicating method (e.g., HPLC). Monitor the decrease in the active compound and the appearance of degradation products.

Protocol: Online LC-LCW-LC Analysis of Phototransformation Products

This advanced protocol allows for the automated study of degradation pathways [5].

Materials:

- LC System: 2D-LC system with a multiple-heart-cutting valve, two binary pumps, and an isocratic pump.

- Detector: Diode-Array Detector (DAD).

- Photoreactor: Liquid-Core-Waveguide (LCW) cell (e.g., 60 µL volume, AF2400 tubing) placed in a light box with a cold-white LED [5].

- Columns: Reversed-phase C18 columns of differing dimensions for ¹D and ²D.

Procedure:

- Inject the sample and perform the ¹D separation.

- Using the heart-cut valve, transfer a fraction containing the target analyte to a loop.

- Use the isocratic pump to flush the fraction from the loop through the LCW cell.

- Irradiate the sample in the LCW cell for a predefined time.

- Flush the irradiated sample to a loop connected to the ²D system.

- Perform the ²D separation to resolve the parent compound from its degradation products.

- Repeat for different irradiation times to build a kinetic profile.

FAQs: Understanding Substrate Effects on Organic Semiconductor Degradation

Q1: Why does my organic semiconductor film degrade differently when using ITO versus Ag substrates?

The electrode material itself can catalyze different chemical reactions during photodegradation. While many degradation products are similar on both ITO and Ag, distinct pathways emerge due to the specific chemical interactions at the interface. On Ag substrates, for example, unique infrared bands in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ region have been observed, suggesting ring opening and rearrangement in the benzothiadiazole unit that does not occur on ITO [11] [12]. Furthermore, ITO surfaces are known to be unstable and can rapidly form metal-hydroxides upon exposure to oxygen or water, creating active sites for further chemical reactions that accelerate degradation [11].

Q2: What is the practical impact of this substrate-dependent degradation on my organic electronic devices?

This dependency directly impacts device longevity and performance. Photo-instability at metallic/organic interfaces is a recognized main cause of device degradation [11]. For instance, photo-degradation at the ITO/organic interface can lead to a significant deterioration in charge transport properties [13]. In non-fullerene organic solar cells, chemical changes at these organic/inorganic interfaces are a suspected origin of instability [11]. This means the choice of electrode contact is not neutral; it fundamentally influences the device's operational stability.

Q3: How can I reliably detect and differentiate between these degradation pathways in my experiments?

Infrared reflectance–absorbance spectroscopy (IRRAS) coupled with multivariate analysis is a powerful technique for this purpose. Although early-stage degradation spectra on different substrates may appear visually similar, advanced data analysis methods like principal component analysis (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) can successfully reveal differences based on both the substrate type and the extent of degradation [11] [12]. This approach can identify specific chemical products, such as anhydride formation from interchain coupling or ketonic products, and attribute them to their pathways [11].

Q4: Are there strategies to mitigate these interfacial degradation issues?

Yes, applying specific interfacial buffer layers is an effective strategy. Research has shown that both CF₄ plasma treatments of the ITO surface and the insertion of an MoO₃ interfacial buffer layer can significantly enhance the photo-stability of the contact [13]. These methods help by reducing the detrimental chemical bonding interactions between the ITO and the adjacent organic layer that are responsible for degradation [13]. Similarly, in non-fullerene solar cells, a pre-annealing process can help prevent the penetration of top electrodes (like MoO₃ and Ag) into the photoactive layer, thereby reducing burn-in degradation [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials used in studying substrate-dependent degradation, based on a model system investigating FBTF on ITO and Ag.

| Item Name | Function/Description | Relevance to Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| FBTF | Model organic semiconductor (oligomer of F8BT) | Serves as the primary test material; its degradation is monitored on different substrates [11]. |

| ITO-coated glass | Transparent conducting oxide electrode (common anode) | One of the two key substrate materials under investigation for its effect on degradation pathways [11]. |

| Ag substrate | Metal electrode (common cathode) | The second key substrate, shown to induce unique degradation products not found on ITO [11]. |

| Palladium catalysts (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄, Pd(OAc)₂) | Catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling synthesis of FBTF | Used in the synthesis of the model OSC, FBTF [11]. |

| Potassium Phosphate / Na₂CO₃ | Base for Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction | Essential reagent in the synthetic pathway for creating the OSC material [11]. |

| MoO₃ | Interfacial buffer layer | Demonstrated to improve contact photo-stability and mitigate degradation at interfaces [13] [14]. |

Experimental Protocols for Substrate-Dependent Degradation Analysis

Protocol 1: Investigating Degradation Pathways via IRRAS with Multivariate Analysis

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to distinguish photodegradation pathways on ITO and Ag [11] [12].

- Substrate Preparation: Obtain ITO-coated glass slides and Ag substrates (e.g., cut from a high-purity Ag rod). Clean substrates thoroughly according to standard procedures (e.g., sequential sonication in acetone, isopropanol, and deionized water) and dry under a nitrogen stream.

- Thin-Film Deposition: Prepare a solution of the organic semiconductor (e.g., FBTF) in a suitable solvent (e.g., toluene). Deposit thin films onto the pre-prepared ITO and Ag substrates using an appropriate method such as spin-coating or drop-casting to ensure uniform coverage.

- Controlled Photodegradation: Place the coated substrates in a controlled environment (e.g., an environmental chamber with controlled temperature and atmosphere). Expose the films to a calibrated light source (e.g., a solar simulator or specific wavelength UV light) to induce photodegradation for set time intervals.

- IRRAS Spectral Monitoring: Use a Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer equipped with a reflectance accessory. Collect IR reflectance–absorbance spectra after each exposure interval. Focus on identifying emerging absorption bands that indicate chemical changes (e.g., carbonyl stretches for ketones ~1700 cm⁻¹, anhydrides ~1800 and 1760 cm⁻¹, and nitrile groups ~2100-2200 cm⁻¹) [11].

- Multivariate Data Analysis: Subject the collected spectral data to multivariate analysis.

- Perform Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of the data and identify the primary sources of variance, which can separate samples by substrate type and degradation time.

- Use Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) as a supervised method to maximize the separation between pre-defined groups (e.g., ITO vs. Ag, early vs. late stage degradation).

Protocol 2: Mitigating Degradation with an MoO₃ Interfacial Layer

This protocol is based on strategies shown to improve the photo-stability of ITO/organic contacts [13] [14].

- Substrate Preparation: Clean ITO-coated glass slides as described in Protocol 1.

- Interfacial Layer Deposition: Deposit a thin layer (a few nanometers) of MoO₃ onto the ITO surface. This is typically done using thermal evaporation under high vacuum to ensure a uniform, pinhole-free layer.

- OSC Layer Deposition: Deposit the organic semiconductor layer (e.g., NPB, FBTF, or a bulk heterojunction blend) directly onto the MoO₃-coated ITO substrate using a suitable method like spin-coating or thermal evaporation.

- Stability Testing: Fabricate control devices without the MoO₃ layer for direct comparison. Subject all devices to accelerated aging tests under continuous illumination or thermal stress while monitoring key performance parameters (e.g., current-voltage characteristics for OPDs/OSCs, luminance for OLEDs) over time.

- Post-Analysis: Use techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to analyze the chemical state of the interface and confirm the stability of the contact after testing [13].

Data Interpretation Guide

The following table summarizes key spectroscopic signatures and their interpretations to help diagnose degradation routes from your IRRAS data.

| Observed Spectral Change | Potential Chemical Change | Typical Substrate Dependence |

|---|---|---|

| Appearance of bands near 1700 cm⁻¹ | Formation of carbonyl groups, specifically ketonic derivatives of the fluorene unit [11] | Common on both ITO and Ag [11] |

| Appearance of a doublet near 1800 cm⁻¹ and 1760 cm⁻¹ | Formation of anhydride groups from a previously unreported interchain coupling mechanism [11] | Observed on both substrates [11] |

| New, weak bands in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ region | Ring opening and rearrangement in the benzothiadiazole (BT) unit, potentially forming nitriles or cyanates [11] | Specifically observed on Ag substrates, not on ITO [11] |

| Reduction in charge injection/collection efficiency, increased series resistance | Chemical degradation at the ITO/organic interface, reducing bonds between ITO and the organic layer [13] | Primarily associated with ITO contacts |

Workflow and Pathway Analysis

The diagram below illustrates the experimental workflow for analyzing substrate-dependent degradation and the divergent pathways identified.

This workflow, based on established research [11] [12], leads to the identification of distinct degradation pathways. A key finding is that Ag electrodes can catalyze unique ring-opening reactions in the benzothiadiazole unit, a pathway not typically observed on ITO.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My organic semiconductor (OSC) thin films show different degradation rates depending on the electrode substrate. How can I identify the specific degradation pathway?

A1: Substrate-dependent photodegradation is a documented phenomenon. The degradation pathway can be identified using IR Reflectance-Absorbance Spectroscopy (IRRAS) coupled with multivariate analysis [11].

- Primary Method: Perform IRRAS on your OSC films deposited on different substrates (e.g., ITO and Ag) and expose them to controlled light. Monitor spectral changes over time [11].

- Data Analysis: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the spectral data. These techniques can reveal subtle, substrate-dependent spectral changes that are not obvious from visual inspection. For example, research on FBTF films identified ring opening in the benzothiadiazole unit specifically on Ag substrates, indicated by new bands in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ region [11].

- Protocol:

- Deposit your OSC as a thin film on the substrates of interest (e.g., ITO and Ag).

- Place the samples in a controlled environment with a stable light source.

- Collect IRRAS spectra at regular intervals during light exposure.

- Analyze the time-series spectral data using PCA/LDA to distinguish degradation pathways based on substrate type and exposure time [11].

Q2: How can I minimize the photodegradation of my sensitive samples during spectrophotometric analysis?

A2: Photodegradation during analysis can be mitigated through specific sample handling and instrumental settings [15].

- Sample Handling:

- Minimize Light Exposure: Use amber glassware or wrap sample containers in aluminum foil. Keep samples in the dark as much as possible and only expose them to light immediately before measurement [15].

- Control Temperature: For heat-sensitive samples, use temperature-controlled cuvettes to prevent thermal degradation [15].

- Shorten Analysis Time: Use rapid-scan modes if available to reduce the total light exposure time [15].

- Instrumental Setup: Ensure your spectrophotometer is well-maintained, as stray light can exacerbate degradation issues [15].

Q3: What computational methods can I use to predict the photodegradation pathways of a pharmaceutical compound?

A3: Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Time-Dependent DFT (TDDFT) are powerful tools for studying photodegradation mechanisms at the molecular level [16].

- Application: These methods can model both direct photodegradation (where the molecule itself absorbs light) and indirect photodegradation (where the molecule reacts with photo-generated reactive species like hydroxyl radicals ·OH or singlet oxygen ¹O₂) [16].

- Output: The calculations can predict reaction pathways, intermediate structures, and activation energies (Ea). This helps identify the most probable degradation routes. For instance, a study on the antidepressant Citalopram (CIT) found that OH-addition and F-substitution reactions have very low activation energies, making them main degradation pathways [16].

- Typical Workflow:

- Use DFT to optimize the geometry of the ground-state molecule.

- Use TDDFT to study the excited-state properties and reactivity.

- Calculate the transition states and activation energies for potential reaction paths involving bond cleavage or reaction with oxidants [16].

Q4: What key reagents are essential for studying and mitigating photodegradation?

A4: The following table details key reagents used in advanced studies for understanding and enhancing photostability.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| 3-Aminopropyltriethoxy silane (APTES) | Used for in-situ cross-linking to form a protective SiO₂ shell around perovskite quantum dots, impeding ion migration and vaporization of organic cations to enhance operational stability [17]. |

| 2,6-bis(N-pyrazolyl)pyridine nickel(II) bromide (Ni(ppy)) | Acts as a co-catalyst. Its multi-π-electron-conjugated structure improves the interface with the perovskite QD, enhancing electron transfer and storage during photocatalytic reactions [17]. |

| 5-Hexynoic Acid / 3-Butynoic Acid | Short alkyl ligands used in the synthesis and purification of perovskite QD-co-catalyst hybrids. They facilitate ligand exchange and increase co-catalyst doping levels [17]. |

| Mercuric Chloride (HgCl₂) | Used in controlled experiments (e.g., at ~180 µM final concentration) to inhibit microbial activity in live incubations, allowing researchers to isolate and quantify abiotic degradation processes like photodegradation [18]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Studies

Protocol 1: Investigating Substrate-Dependent OSC Photodegradation with IRRAS and Multivariate Analysis

This protocol is based on a study investigating the photodegradation of an F8BT model oligomer on ITO and Ag substrates [11].

1. Materials Synthesis

- OSC Model Compound: Synthesize 4,7-bis(9,9-dimethyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)benzo[c][1,2,5]thiadiazole (FBTF) via a Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction.

- Reagents: 4,7-dibromo-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole, 2-(9,9-dimethyl-9H-fluoren-2-yl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-1,3,2-dioxaborolane, a palladium catalyst (e.g., Pd(PPh₃)₄ or a melamine-palladium catalyst), a base (e.g., potassium phosphate or Na₂CO₃), and a solvent (e.g., toluene or ethyl lactate) [11].

- Procedure: Heat the mixture under stirring (e.g., 80°C for 48 hours). Purify the crude product via column chromatography and recrystallize from a suitable solvent system like THF/ethanol [11].

2. Sample Preparation and Degradation

- Substrates: Use ITO-coated glass and polished Ag stubs as electrode contacts [11].

- Film Deposition: Deposit thin films of FBTF onto the clean substrates.

- Photodegradation Setup: Expose the prepared samples to a controlled light source in ambient or controlled atmospheric conditions. The light spectrum and intensity should be documented.

3. Data Collection and Analysis

- IRRAS Measurement: Collect infrared reflectance-absorbance spectra of the films at regular intervals during light exposure [11].

- Multivariate Analysis: Subject the time-series spectral data to Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). This statistical processing helps objectively identify and classify subtle spectral changes correlated with the substrate type and degradation extent [11].

Protocol 2: Computational Study of a Pharmaceutical's Photodegradation Pathways using DFT/TDDFT

This protocol outlines the computational approach to study the photodegradation of Citalopram (CIT) in water [16].

1. Computational Setup

- Software: Use quantum chemical software capable of performing DFT and TDDFT calculations (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA).

- Method and Basis Set: Select an appropriate functional (e.g., B3LYP) and basis set (e.g., 6-31G*) for the calculations.

2. Calculation Steps

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the molecular geometry of CIT in its ground state (S₀) to find the most stable structure [16].

- Excited-State Calculation: Use TDDFT to calculate the properties of the excited triplet state (T₁), which is often involved in photochemical reactions [16].

- Reaction Pathway Exploration:

- Direct Photodegradation: Model the bond cleavage reactions (e.g., C–C, C–N, C–F) and calculate the activation energy (Ea) for each pathway [16].

- Indirect Photodegradation: Model the reaction between CIT and common reactive oxygen species like hydroxyl radicals (·OH) or singlet oxygen (¹O₂). Identify possible reaction sites (e.g., OH-addition, F-substitution) and calculate the transition states and activation energies for these reactions [16].

3. Data Analysis

- Compare the activation energies (Ea) of all possible pathways. The pathways with the lowest Ea are the most kinetically favorable and represent the main photodegradation routes [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table summarizes key materials and their functions for experiments in photodegradation and OSC research.

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Substrates | ITO-coated glass, Ag stubs [11] | Serve as model electrode contacts to study substrate-dependent interfacial degradation in OSC devices. |

| Spectroscopic Tools | IR Reflectance-Absorbance Spectroscopy (IRRAS) [11] | A surface-sensitive technique to monitor chemical changes in thin films during degradation. |

| Data Analysis Software | Multivariate Analysis (PCA, LDA) [11] | Software for statistical analysis of complex spectral data to identify patterns and classify degradation pathways. |

| Computational Tools | Density Functional Theory (DFT), Time-Dependent DFT (TDDFT) [16] | Computational methods to model and predict molecular geometries, excited states, and reaction pathways for photodegradation. |

| Stabilizing Agents | APTES, Ni(ppy) co-catalyst [17] | Chemicals used to passivate defects, form protective layers, and improve interfaces to enhance photostability. |

| Microbial Inhibitor | Mercuric Chloride (HgCl₂) [18] | Used in control experiments to inhibit biodegradation, allowing for the isolation of photodegradation effects. |

Workflow Diagrams

Research Paths for Photodegradation

Photodegradation Correction Strategies

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Photodegradation in Spectroscopy

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My analyte's absorbance decreases significantly over time during spectral acquisition. What is the most likely cause? A1: This is a classic sign of photodegradation, most commonly initiated by UV/Visible light exposure in the presence of oxygen (photo-oxidation). The high-energy photons break chemical bonds, creating reactive species that react with ambient oxygen, leading to the degradation of your compound and a loss of absorbance.

Q2: How can I confirm that oxygen is causing my sample's instability? A2: Perform a simple controlled atmosphere experiment.

- Protocol:

- Prepare two identical samples of your analyte in sealed quartz cuvettes.

- For the test sample, purge the headspace with an inert gas like nitrogen or argon for 10-15 minutes before sealing.

- For the control sample, leave the headspace filled with ambient air.

- Expose both samples to the same controlled light source (e.g., a solar simulator or a specific wavelength from your spectrometer's lamp) for a set duration.

- Measure the absorbance or fluorescence of both samples at regular intervals.

- Expected Outcome: The sample purged with inert gas will show significantly less degradation than the control, confirming the role of oxygen.

Q3: My laboratory has standard fluorescent lighting. Could this be affecting my samples before they are even measured? A3: Yes. Standard fluorescent lights emit a non-negligible amount of UV and broad-spectrum visible light.

- Solution: Always store light-sensitive samples in amber glass vials or wrapped in aluminum foil. Perform sample preparation in low-light conditions whenever possible.

Q4: Why does the same compound degrade at different rates in different solvents? A4: Solvents can act as intermediaries in photochemical reactions. Some solvents (e.g., chloroform) can generate radicals upon light exposure, accelerating degradation. Others, like water, can facilitate hydrolysis reactions that are also light-dependent. Furthermore, the solubility of oxygen varies between solvents, affecting the rate of photo-oxidation.

Q5: How does water vapor contribute to photodegradation? A5: Water vapor can participate in hydrolysis reactions, where water molecules split chemical bonds. When these reactions are catalyzed or accelerated by light, it is known as photohydrolysis. This is a significant concern for hygroscopic (water-absorbing) samples or for experiments conducted in humid environments.

Quantitative Data on Environmental Triggers

Table 1: Common Light Sources and Their Spectral Outputs Relevant to Photodegradation

| Light Source | Peak Wavelength (nm) | Key Spectral Range | Relative Photon Energy |

|---|---|---|---|

| UVB Lamp | 302 nm | 280-315 nm | Very High |

| Sunlight (Midday) | ~500 nm | 290-2500 nm | Broad Spectrum (High UV) |

| Xenon Arc Lamp | ~450-500 nm | 250-2000 nm | Broad Spectrum (Simulates Sunlight) |

| Standard Fluorescent | Multiple Peaks | 400-700 nm | Moderate (Low UV) |

| Red LED | 630 nm | 620-645 nm | Low |

Table 2: Effectiveness of Common Quenchers and Stabilizers

| Reagent | Target Trigger | Mechanism of Action | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Azide | Singlet Oxygen | Physical Quencher | 1-5 mM |

| DABCO | Singlet Oxygen | Physical Quencher | 10-100 mM |

| Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) | Free Radicals | Radical Scavenger | 50-200 µM |

| Ascorbic Acid | Oxygen / Radicals | Reducing Agent | 0.1-1 mM |

| Inert Gas (N₂/Ar) | Oxygen | Displacement | N/A (Headspace Purging) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Assessing Photostability Under Controlled Illumination

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a standardized solution of the analyte in the solvent of interest. Aliquot into multiple identical vials/cuvettes.

- Environmental Control: Subject the aliquots to different conditions (e.g., one group purged with N₂, one with air, one with added stabilizer).

- Illumination: Expose the samples to a calibrated light source (e.g., a solar simulator with an AM 1.5G filter). Control the intensity (e.g., 1000 W/m²) and duration of exposure.

- Analysis: At defined time intervals, remove samples and analyze them using your spectroscopic technique (e.g., UV-Vis, HPLC-MS). Monitor for changes in the primary absorption peak, the appearance of new peaks (degradants), or a loss of fluorescence intensity.

- Data Analysis: Plot the remaining concentration or peak area versus time to determine degradation kinetics (e.g., zero-order, first-order).

Protocol: Quantifying the Impact of Ambient Humidity

- Chamber Setup: Use a sealed desiccator or humidity chamber. Control humidity using saturated salt solutions (e.g., LiCl for ~15% RH, NaCl for ~75% RH).

- Sample Preparation: Place identical, open aliquots of your sample solution in small vials inside the different humidity chambers. Include a control in a dry environment (e.g., with desiccant).

- Light Exposure: Expose the entire chamber to a consistent light source. Ensure all samples receive identical irradiance.

- Analysis: After exposure, seal the sample vials and analyze them spectroscopically. Compare the degree of degradation across the different humidity levels.

Visualization of Experimental Concepts

Diagram: Photodegradation Pathways

Diagram: Photostability Assay Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Amber Glassware | Protects light-sensitive samples from ambient UV/visible light during storage and handling. |

| Sealed Cuvettes | Prevents solvent evaporation and limits exposure to atmospheric oxygen and water vapor during measurement. |

| Inert Gas (N₂/Ar) | Used to purge solutions and create an oxygen-free atmosphere, halting oxidative degradation pathways. |

| Singlet Oxygen Quenchers (e.g., Sodium Azide) | Chemically deactivates reactive singlet oxygen, helping to isolate its role in the degradation mechanism. |

| Radical Scavengers (e.g., BHT) | Intercepts free radicals formed during photolysis, preventing chain-propagation reactions. |

| Saturated Salt Solutions | Provides a simple and reliable method for generating specific, constant relative humidity levels in closed chambers. |

| Solar Simulator | Provides a standardized, intense light source that mimics the solar spectrum for accelerated stability testing. |

Methodologies for Monitoring and Testing: From ICH Guidelines to Advanced Spectroscopic Techniques

FAQ: ICH Q1B Photostability Testing

1. What is the purpose of ICH Q1B photostability testing? The ICH Q1B guideline provides a standardized process to evaluate how a new drug substance or product is affected by light exposure. The goal is to test the intrinsic photostability characteristics of the drug, which informs essential decisions about its packaging, labeling, and storage conditions to ensure quality, safety, and efficacy throughout its shelf life [19] [20] [21].

2. Is photostability testing mandatory for new drug applications? While the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) states that light testing should be an integral part of stress testing, the ICH Q1B guidance contains non-binding recommendations [19]. However, it represents the regulatory standard and current thinking of the FDA and other international agencies. Following ICH Q1B is considered a best practice and is strongly recommended for products at risk of light degradation, especially for submissions of New Drug Applications (NDAs) or Abbreviated New Drug Applications (ANDAs) [20].

3. What are the core light exposure conditions specified in ICH Q1B? The guideline defines minimum requirements for light exposure. The confirmatory study should expose samples to both ultraviolet and visible light. The following table summarizes the core quantitative requirements [20] [22]:

| Parameter | Requirement | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet Region | Not less than 200 W·h/m² (320-400 nm) | Monitored with a calibrated radiometer or validated actinometric system. |

| Visible Region | Not less than 1.2 million lux·hours (400-800 nm) | Monitored with a calibrated lux meter. |

4. What is the recommended testing sequence? ICH Q1B recommends a sequential testing approach to efficiently determine the necessary level of protection [22]:

- Step 1: Test the drug substance and product unpackaged.

- Step 2: If unacceptable change occurs, test the product in its immediate primary pack (e.g., the bottle or blister).

- Step 3: If the product is still unstable in the primary pack, test it in its secondary market pack (e.g., the carton). Products that are stable only when packaged should have labeling instructions to protect them from light (e.g., "Store in the original container") [22].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Irradiation Source and Calibration Issues

A common challenge is ensuring the light source and its measurement are compliant and reproducible.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent results between testing cycles. | Variation in the spectral output of the light source over time or between different instruments. | Implement a rigorous calibration schedule. Use a chemical actinometer (e.g., quinine monohydrochloride) in addition to physical radiometers to measure the effective irradiance, as it can provide a more reliable measure of the photolytic exposure a sample receives [22]. |

| Uncertainty if the light source meets ICH Q1B spectral requirements. | The guideline offers two options, and the specific spectral power distribution (SPD) of a lamp can vary [22]. | Select a light source that complies with Option 1, which is defined by an overall spectral distribution similar to the ID65 standard (international standard for daylight). This is the most widely accepted and reproducible method [20] [22]. |

| Meeting the visible light requirement vastly exceeds the UV requirement. | The ratio of 1.2 million lux-hours to 200 W·h/m² is not 1:1. For a D65 simulator, the visible exposure alone provides sufficient UV energy [22]. | Follow the guideline's instruction to expose samples for the duration required to meet both the ultraviolet and visible minimums. In practice, this typically means the longer of the two exposures is the controlling factor [22]. |

Guide 2: Resolving Problems with Sample Presentation and Analysis

How samples are prepared and analyzed can significantly impact the outcome and interpretation of the test.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| A solid drug substance shows non-uniform degradation. | The sample was not spread evenly, leading to areas of shadow and varying layer thickness, which causes unequal light exposure [22]. | Present solid samples as a layer not more than 2 mm thick, such as in a Petri dish, and ensure the powder is spread evenly to maximize uniform exposure [22]. |

| Difficulty in interpreting the clinical relevance of degradation products. | The guideline does not explicitly cover the photostability of drugs under conditions of patient use (e.g., after dilution or administration) [23]. | While ICH Q1B focuses on shelf-life stability, it is a best practice to evaluate the potential for phototoxicity of the degradation products formed. This may require additional studies beyond the core guideline to ensure patient safety [24]. |

| Unclear how to handle protective packaging materials during testing. | The transmittance characteristics of packaging (e.g., colored glass or plastic) can affect how much light reaches the product [22]. | When testing in primary packs, it is critical to know the UV and visible transmittance properties of the packaging material. For confirmatory studies, the sample should be exposed while in the primary pack as it will be marketed [22]. |

Experimental Protocol: Core ICH Q1B Confirmatory Study

This protocol outlines the key steps for conducting a confirmatory photostability study on a drug product according to ICH Q1B Option 1.

1. Objective: To determine the photostability of a finished drug product in its immediate primary pack, enabling decisions on appropriate packaging and labeling.

2. Materials and Equipment

- Light source meeting D65/ID65 daylight standard output [20] [22].

- Calibrated light bank or chamber capable of controlling temperature.

- Calibrated radiometer and lux meter.

- Chemical actinometer (e.g., quinine monohydrochloride solution) for system validation [22].

- Sample of the drug product in its primary container (e.g., clear glass bottle).

- Appropriate opaque controls (e.g., wrapped in aluminum foil).

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Calibration. Validate the light exposure system using the chemical actinometer to confirm it delivers the required irradiance, or use a calibrated radiometer/lux meter [22].

- Step 2: Sample Preparation. Place the drug product in its primary container (and secondary carton if required by the testing sequence) into the light chamber. Include wrapped dark controls of the same batch to distinguish light-induced changes from thermal degradation.

- Step 3: Light Exposure. Expose the samples to a total illumination of not less than 1.2 million lux hours and an integrated near-ultraviolet energy of not less than 200 watt-hours per square meter [20] [22]. Maintain controlled temperature conditions (e.g., 25°C ± 2°C) to minimize thermal effects.

- Step 4: Sample Analysis. After exposure, compare the irradiated samples with the dark controls for any changes in:

- Appearance (e.g., color, clarity, physical form).

- Potency (assay of the active ingredient).

- Degradation Products (increase in related substances).

4. Data Interpretation and Actions

- Stable: No significant change compared to the dark control. Standard packaging and labeling may be sufficient.

- Unstable: Significant change in appearance, potency, or purity. Consider protective packaging (e.g., amber glass, opaque blisters) and/or labeling instructions (e.g., "Protect from light") [20] [22].

The following workflow diagrams the logical sequence for designing and interpreting a photostability study, integrating the core concepts of ICH Q1B.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in a compliant ICH Q1B photostability study.

| Item | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| D65/ID65 Simulating Light Source | A fluorescent, xenon, or metal halide lamp whose spectral power distribution mimics outdoor daylight filtered through window glass. This is the standard source defined in ICH Q1B Option 1 [20] [22]. |

| Chemical Actinometer | A chemical system (e.g., quinine monohydrochloride solution) whose known photochemical reaction rate is used to quantify the total photolytic exposure delivered by a light source. It serves to validate the physical radiometer data [22]. |

| Calibrated Radiometer | An instrument used to measure the cumulative irradiance (W·h/m²) in the ultraviolet range (320-400 nm) to ensure the minimum requirement is met [20] [22]. |

| Calibrated Lux Meter | An instrument used to measure the cumulative illumination (lux·hours) in the visible range (400-800 nm) to ensure the minimum requirement is met [20] [22]. |

| Protective Packaging Materials | Various containers (e.g., amber glass, opaque plastics, aluminum foil overwraps) used in the sequential testing approach to determine the minimum packaging required to protect the product from light [20] [22]. |

| Forced Degradation Study Samples | Samples of the drug substance intentionally degraded under harsh light conditions. This is not the confirmatory study but a preliminary step used to identify potential degradation products and validate analytical methods [22]. |

The process of conducting a forced degradation study, which precedes the confirmatory study, is outlined below.

Troubleshooting Guide: Ensuring Spectral Data Integrity

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when setting up light sources, filters, and exposure conditions for experiments focused on correcting photodegradation in spectroscopic measurements.

FAQ 1: My sample's spectral signal degrades rapidly during measurement. How can I confirm if my light source is the cause and what steps can I take?

Photodegradation during analysis can compromise data integrity. Follow this diagnostic protocol to identify and correct for light-induced sample degradation.

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Control Experiment: Begin by measuring a stable reference standard (e.g., polystyrene or a stable solvent like benzonitrile) [25] under your standard experimental conditions. Observe the signal over the typical duration of your sample measurement. A stable signal in the control indicates the issue is sample-specific, not instrumental.

- Attenuate Light Exposure: If the control is stable, repeat the measurement on your sensitive sample with reduced light exposure. This can be achieved by:

- Reducing Laser Power: Lower the output power of your excitation source.

- Using Neutral Density Filters: Introduce these filters in the light path to attenuate intensity without altering the wavelength.

- Shortening Exposure/Integration Time: Decrease the time the sample is illuminated for each measurement [25].

- Monitor Temporal Changes: Collect a time-series of spectra from the same sample spot. A progressive change in the spectrum (e.g., photobleaching of absorption features, emergence of new peaks) is a direct indicator of photodegradation [26].

Corrective Actions:

- Optimize Conditions: Use the minimum light intensity and shortest exposure time necessary to achieve an acceptable signal-to-noise ratio.

- Implement Environmental Controls: For samples susceptible to photo-oxidation, employ an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon glovebox) during measurement, as oxidative processes are often accelerated by light [26].

FAQ 2: My spectrometer's wavelength and intensity readings seem to drift over time. How do I correct for this instrumental instability?

Long-term instrumental drift is a critical source of error that can be misattributed to sample photodegradation. A rigorous calibration protocol is essential [27] [25].

- Calibration and Correction Protocol:

- Wavelength Calibration:

- Procedure: Regularly measure a standard with sharp, well-defined emission or Raman peaks (e.g., cyclohexane, paracetamol, or a neon/argon lamp for emission spectroscopy) [27] [25].

- Validation: Compare the measured peak positions to their certified values. The mean absolute deviation (MAD) across multiple peaks should be minimal. Software can then be used to adjust the wavelength axis of your sample data accordingly [25].

- Intensity/Response Calibration:

- Procedure: Use a calibrated standard lamp with a known spectral output profile or a stable reference material like silicon (for its characteristic Raman band at 520 cm⁻¹) to correct for changes in the system's response function [27] [25].

- Frequency: Recalibration should be performed weekly or as recommended by the manufacturer, especially when highly quantitative data is required over long periods [25].

- Dark Noise Correction:

- Procedure: Always measure and subtract the "dark" signal (with the light source blocked) from your sample spectrum to account for thermal and electronic noise in the detector [27].

- Wavelength Calibration:

FAQ 3: How can I design my experiment to proactively account for and correct photodegradation effects?

A robust experimental design incorporates strategies to monitor and correct for instability from the outset.

- Proactive Methodologies:

- Use Internal Standards: Whenever possible, incorporate a stable, non-interfering compound directly into your sample matrix. The consistent signal from this internal standard can be used to normalize your data and correct for both instrumental drift and uniform photodegradation effects.

- Systematic Randomization: When collecting multiple samples or time points, randomize the measurement order to prevent systematic bias from slow instrumental drifts.

- Computational Correction: For advanced users, computational methods like the Extensive Multiplicative Scattering Correction (EMSC) can be applied to estimate and suppress spectral variations arising from instrumental sources, thereby improving the reliability of long-term data [25].

The following workflow provides a systematic approach for diagnosing and correcting photodegradation and instrumental instability.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following materials are critical for conducting reliable spectroscopy experiments and correcting for photodegradation and instrumental effects.

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Polystyrene [25] | A solid standard used for wavenumber calibration in Raman spectroscopy due to its well-characterized and sharp Raman peaks. |

| Cyclohexane [25] | A liquid standard used for precise wavenumber calibration of Raman spectrometers across a broad spectral range. |

| Paracetamol [25] | A standard reference material (from EP/NIST) used for validating wavelength accuracy and intensity response. |

| Silicon Wafer [25] | Used to calibrate and verify the intensity response and exposure time of a Raman system via its strong band at 520 cm⁻¹. |

| Benzonitrile / DMSO [25] | Stable solvents used as control samples to test for instrumental stability and sample-specific photodegradation over time. |

| Calibrated Standard Lamp [27] | A light source with a known spectral output profile used for intensity/response calibration of spectrometers. |

| Neutral Density (ND) Filters | Optical filters used to uniformly attenuate the intensity of a light source without altering its spectral composition, crucial for controlling sample exposure. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common issues and questions researchers encounter when using FTIR, Photoluminescence, and Raman spectroscopy, with a focus on mitigating photodegradation and ensuring data fidelity.

FTIR Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Q1: My FTIR spectrum has a noisy baseline with strange peaks. What could be the cause? Several instrumental and sample-related factors can cause this:

- Instrument Vibration: FTIR spectrometers are highly sensitive to physical disturbances. Vibrations from nearby pumps, compressors, or general lab activity can introduce false spectral features. Ensure your instrument is placed on a stable, vibration-free surface [28].

- Contaminated ATR Crystal: A dirty Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) crystal is a common cause of distorted baselines and unexpected negative peaks. Contaminants from previous samples can interfere with the measurement. Solution: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with an appropriate solvent and acquire a fresh background scan before measuring your sample [28].

- Sample Anomalies: For materials like polymers, the surface chemistry (which may have oxidized or contained additives) can differ from the bulk material. This can lead to confusing spectra. Solution: Compare spectra from the surface with those from a freshly cut interior to identify if you are observing surface effects [28].

Q2: When processing diffuse reflectance data, my absorbance spectrum looks distorted. What am I doing wrong? This is likely a data processing error. For diffuse reflection measurements, processing data in standard absorbance units can produce distorted spectra. Solution: Convert your data to Kubelka-Munk units, which provides a more linear and accurate representation for analysis of diffusely scattered light [28].

Photoluminescence (PL) Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Q3: What is the fundamental difference between photoluminescence, fluorescence, and phosphorescence? Photoluminescence is the overarching phenomenon where a material emits light after absorbing photons. It manifests in two primary forms:

- Fluorescence: A rapid emission process where the excited electron decays from a singlet excited state. Emission typically occurs within nanoseconds [29].

- Phosphorescence: A much slower emission process involving a forbidden transition from a triplet excited state. Emission can persist from microseconds to hours [29]. PL is a non-contact, nondestructive method ideal for probing the electronic structure of materials like semiconductors and nanomaterials [29] [30].

Q4: My PL signal from a semiconductor sample is very weak. What could be reducing the luminescence efficiency? Weak PL signal can be caused by several factors, with nonradiative surface recombination being a major culprit, especially in semiconductors. At the boundaries or surfaces of a material, defects can provide pathways for excited electrons to relax without emitting a photon, significantly limiting the efficiency of light-emitting diodes, lasers, and photovoltaic cells [31]. Time-resolved PL (TRPL) is a key method to characterize these recombination dynamics and measure carrier lifetime [31].

Raman Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Q5: My Raman spectra have a high, sloping background that obscures the peaks. What is this and how can I fix it? This is most likely fluorescence interference, a very common sample-related artifact in Raman spectroscopy. The fluorescence signal from the sample or impurities can be orders of magnitude more intense than the Raman signal, generating a broad background [32] [33]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Using a longer excitation wavelength (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm) to reduce the energy enough to avoid exciting fluorescent transitions [32].

- Photobleaching the sample with the laser for an extended period before measurement.

- Applying computational background correction algorithms during data processing. Crucially, this baseline correction must be performed before any spectral normalization to avoid biasing your data [33].

Q6: I see sharp, random spikes in my Raman spectrum. What are they? These are cosmic rays, a common instrumental artifact. High-energy cosmic particles can strike the detector, causing a sharp, intense spike in the signal [32] [33]. Most modern Raman software includes algorithms for cosmic spike removal. It is a standard first step in the data analysis pipeline to identify and correct these spikes before further processing [33].

Q7: What are critical mistakes to avoid in Raman data analysis? Avoiding these common errors will significantly improve the reliability of your models:

- Skipping Calibration: Failure to perform wavelength/wavenumber calibration using a standard can cause systematic drifts to be mistaken for sample changes [33].

- Incorrect Preprocessing Order: Always perform background correction before spectral normalization. Normalizing first will code the fluorescence intensity into the normalization constant, biasing the results [33].

- Over-Optimized Preprocessing: Using over-optimized parameters for baseline correction can lead to overfitting. Use spectral markers, not model performance, to guide parameter selection [33].

- Model Evaluation Errors: Ensure complete independence between training, validation, and test data sets. "Replicate-out" or "patient-out" cross-validation is essential to prevent data leakage and overestimation of model performance [33].

Quantitative Data & Experimental Protocols

Key Experimental Parameters for Spectroscopic Techniques

Table 1: Typical parameters for FTIR, PL, and Raman experiments.

| Technique | Key Measurable | Typical Excitation Source | Primary Output | Critical for Mitigating Photodegradation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR [34] | Evolved CO₂, Carbonyl Index | Xenon lamp (e.g., with AM1.5 filter) | Absorbance (a.u.) vs. Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | In-situ measurement allows rapid assessment, minimizing long-term exposure. |

| Photoluminescence [29] [31] | Carrier Lifetime, Band Gap, Defect States | Pulsed Lasers (e.g., Nd:YAG, Picosecond) | Intensity (a.u.) vs. Wavelength (nm) & Decay Time (s) | Time-resolved (TRPL) uses low-duty-cycle pulses, reducing total light dose. |

| Raman [32] [35] | Molecular Fingerprint, Phonon Modes | 532 nm, 785 nm, 1064 nm Lasers | Intensity (a.u.) vs. Raman Shift (cm⁻¹) | Use of lower energy (785/1064 nm) lasers and lower power density reduces photochemical effects. |

Detailed Protocol: Rapid Measurement of Polymer Photo-degradation by FTIR

This protocol outlines a method to rapidly assess polymer photo-degradation by quantifying evolved carbon dioxide (CO₂), providing a quick alternative to measuring carbonyl group development [34].

1. Materials

- Polymer films (e.g., Low-Density Polyethylene), unpigmented or pigmented with TiO₂ or other fillers [34].

- Specialized IR reaction cell with a calcium fluoride (CaF₂) window [34].

- Xenon lamp with appropriate optical filters (e.g., AM1.5 filter to simulate solar spectrum) [34].

- FTIR Spectrometer.

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Cell Preparation & Baseline. Mount the polymer film sample inside the IR reaction cell. Acquire an initial FTIR spectrum with the UV light source off to establish a baseline for CO₂ absorbance [34].

- Step 2: In-Situ UV Exposure & Measurement. Expose the sample to UV irradiation through the cell window. Continuously or intermittently collect FTIR spectra to monitor the growth of the characteristic CO₂ absorbance band(s) over time (e.g., hourly) [34].

- Step 3: Data Analysis. Plot the integrated area or height of the CO₂ absorbance peak against irradiation time. The rate of CO₂ generation is a direct measure of the polymer's photo-oxidation rate. This can be correlated with traditional methods like carbonyl index development [34].

3. Logical Workflow The diagram below illustrates the experimental and data processing workflow for this protocol.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for spectroscopic experiments.

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Context |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Calibration Films [36] | Abscissa (wavenumber) and ordinate (absorbance) calibration for FTIR instruments. | Certified to traceable standards (e.g., NIST); critical for ensuring spectral accuracy and instrument performance over time. |

| ATR Cleaning Solvents | Cleaning contaminated ATR crystals (e.g., Diamond, ZnSe). | Isopropanol, hexane, or acetone are commonly used to remove sample residue, preventing carryover and negative peaks in FTIR spectra [28]. |

| Wavenumber Standard (e.g., 4-Acetamidophenol) [33] | Calibrating the wavenumber axis in Raman spectroscopy. | Contains multiple sharp peaks; used to construct a stable wavenumber axis, preventing spectral drift from being misinterpreted as a sample change. |

| Pure Compound Standards for Spiking [35] | Creating synthetic spectral libraries for Raman model calibration. | Pure analytes (e.g., glucose, lactate) are measured in water to create spectral fingerprints, which are fused with process data to build robust calibration models. |

Advanced Correction Methodologies

A Unified Workflow for Anomaly Correction in Spectroscopy

The following diagram outlines a generalized, multi-technique approach to identifying and correcting common artifacts and anomalies in spectroscopic data, which is crucial for obtaining reliable results in photodegradation studies.

Synthetic Spectral Libraries for Raman Calibration

A modern approach to building robust Raman calibration models involves creating Synthetic Spectral Libraries (SSLs) [35]. This method addresses the time-consuming and costly nature of traditional model building.

- Methodology: Pure compounds of interest (e.g., glucose, lactate) are dissolved in water and their characteristic Raman "fingerprint" spectra are acquired at various concentrations. These pure component spectra are then fused in silico with a base of existing spectral data from complex processes (e.g., cell culture broths) [35].

- Advantages: This data fusion approach can generate a vast and information-rich library of synthetic spectra, which effectively "breaks the correlation" between naturally co-varying analytes. It greatly reduces the manual labor and cost associated with physical spiking experiments while accounting for real-world spectral perturbations [35].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: A new, sharp peak appears at ~2160 cm⁻¹ during my UV irradiation experiment. What does this indicate? A1: This typically indicates the formation of a terminal metal-bound isocyanide (M-C≡N-R) or a metal cyanide (M-C≡N) complex. These species are common photodegradation products of metal-carbonyl complexes (which absorb in the 1900-2050 cm⁻¹ range). The shift to a higher wavenumber suggests a change in the metal's oxidation state or ligand field, reducing π-backbonding and strengthening the C≡N bond.

Q2: My azide peak at ~2100 cm⁻¹ disappears upon exposure to light. What happened and how can I confirm it? A2: The disappearance of the azide (-N₃) asymmetric stretch is a classic sign of photolytic cleavage, often releasing N₂ gas and forming a reactive nitrene species. To confirm:

- Monitor N₂ Formation: Use mass spectrometry (MS) to detect the release of N₂ (m/z = 28).

- Identify the Nitrene Product: The nitrene will rapidly react. Use NMR to identify the final product, which could be an amine (from C-H insertion) or an aziridine (from reaction with an alkene).

Q3: The peak in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ region is broad and weak. Is this significant or just noise? A3: Do not dismiss it. A broad, weak peak can indicate a low concentration of a degradation product or a weakly absorbing moiety (like a thiocyanate, N≡C-S, which can have a broad band). Increase the number of scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. If the peak intensity grows with irradiation time, it is almost certainly a real degradation product.

Q4: How do I distinguish between an isocyanide and a cyanide degradation product using FTIR? A4: The peaks can be very close. You must use complementary techniques.

- FTIR Context: Isocyanides (R-N≡C) often appear between 2140-2160 cm⁻¹, while cyanides (C≡N) can be between 2080-2160 cm⁻¹. This overlap makes definitive assignment difficult by IR alone.

- Confirm with NMR: ¹³C NMR is definitive. A cyanide carbon (M-C≡N) resonates between δ 120-160 ppm, while an isocyanide carbon (M-N≡C) appears far downfield between δ 150-180 ppm.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: In Situ FTIR Photodegradation Monitoring

Objective: To monitor the real-time photodegradation of a metal-carbonyl complex and identify products in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ region.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a ~5 mM solution of the metal-carbonyl complex (e.g., Mn(CO)₆Br) in a suitable, UV-transparent solvent (e.g., dichloromethane). Ensure the solution is degassed with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 15 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Baseline Acquisition: Place the solution in a sealed, UV-transmissive reaction vessel (e.g., quartz cuvette) within the FTIR spectrometer. Collect a background spectrum.

- Irradiation: Position a UV light source (e.g., 365 nm LED) at a fixed distance from the reaction vessel. Initiate irradiation.

- Spectral Collection: Continuously collect FTIR spectra (e.g., 1 spectrum every 30 seconds) throughout the irradiation period (e.g., 30 minutes). Focus on the spectral windows 1700-2200 cm⁻¹.

- Data Analysis: Plot the intensity of the parent carbonyl peaks and any new peaks in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ region versus time to determine kinetic profiles.

Protocol 2: Post-Irradiation Analysis for Nitrene Trapping

Objective: To confirm the formation of a reactive nitrene intermediate from organic azide photodegradation.

- Photolysis: Irradiate a solution of the organic azide (e.g., an alkyl azide) in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of a nitrene trap, such as cyclohexene, using a Pyrex-filtered medium-pressure mercury lamp for 1-2 hours.

- Reaction Quenching: Concentrate the reaction mixture under reduced pressure.

- Product Isolation: Purify the crude mixture using flash chromatography.

- Product Identification: Analyze the purified product using ¹H NMR, ¹³C NMR, and MS. The characteristic signals of an aziridine ring confirm nitrene formation and trapping.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Diagnostic IR Bands for Common Moieties in the 2100–2200 cm⁻¹ Region

| Moiety | Compound Type | Typical IR Range (cm⁻¹) | Band Shape | Common Degradation Origin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azide (-N₃) | Organic Azide | 2090-2160 | Strong, Sharp | Parent compound (disappears) |

| Cyanide (-C≡N) | Metal Cyanide | 2080-2160 | Sharp | Metal-carbonyl complexes, nitriles |

| Isocyanide (-N≡C) | Metal Isocyanide | 2140-2160 | Sharp | Rearrangement of metal-carbonyls |

| Thiocyanate (-S-C≡N) | Metal Complex | 2040-2100 | Broad | Ligand decomposition |

Table 2: Quantitative Spectral Changes During Mn(CO)₆Br Photolysis

| Irradiation Time (min) | [Mn(CO)₆Br] Peak @ 2095 cm⁻¹ (Abs) | [Mn(CN)(CO)₅] Peak @ 2160 cm⁻¹ (Abs) | % Degradation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0% |

| 5 | 0.62 | 0.08 | 27% |

| 10 | 0.41 | 0.18 | 52% |

| 15 | 0.25 | 0.24 | 71% |

| 20 | 0.15 | 0.27 | 82% |

Mandatory Visualization

Photodegradation Pathway of a Metal Carbonyl

In Situ IR Photodegradation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|