Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques for Advanced Material Characterization: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of modern spectroscopic techniques for material characterization, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques for Advanced Material Characterization: From Fundamentals to AI-Driven Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of modern spectroscopic techniques for material characterization, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores fundamental principles of light-matter interactions across the electromagnetic spectrum, examines methodological applications of techniques including Raman, FTIR, XRF, ICP-MS, and LIBS, addresses practical troubleshooting for matrix effects and interferences, and validates techniques through comparative case studies in pharmaceutical and mineral analysis. The review highlights the transformative impact of AI and machine learning in enhancing data interpretation, accelerating cross-modality spectral transfer, and shaping the future of high-throughput materials characterization in biomedical and clinical research.

Fundamental Principles of Light-Matter Interactions in Spectroscopy

Electromagnetic Spectrum Regions and Their Analytical Significance

The electromagnetic (EM) spectrum encompasses the entire distribution of electromagnetic radiation, classified by frequency or wavelength [1]. It ranges from long-wavelength, low-frequency radio waves to short-wavelength, high-frequency gamma rays, with visible light representing only a small fraction in the middle [2] [3]. Spectroscopy, the study of the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation, leverages these different regions to probe the composition, structure, and properties of materials [1] [4]. The fundamental principle is that matter can absorb, emit, or transmit radiation, and the resulting spectrum provides a characteristic fingerprint for analysis [1] [5]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of spectroscopic techniques based on EM spectrum regions, detailing their operational principles, applications, and experimental protocols for material characterization research.

The Electromagnetic Spectrum and Energy-Matter Interactions

The electromagnetic spectrum is systematically divided into regions. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview, listing these regions in order of increasing energy and decreasing wavelength, along with their corresponding wavelength and frequency ranges and key characteristics [1] [6].

Table 1: Regions of the Electromagnetic Spectrum

| Region | Wavelength Range | Frequency Range | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radio Waves | > 1 m | < 3 x 10⁸ Hz | Used in NMR spectroscopy, communications, and MRI [1] [3] [6]. |

| Microwaves | 1 mm – 1 m | 3 x 10⁸ – 3 x 10¹¹ Hz | Excites molecular rotations; used in cooking and radar [1] [6]. |

| Infrared (IR) | 700 nm – 1 mm | 3 x 10¹¹ – 4.3 x 10¹⁴ Hz | Associated with molecular vibrations; perceived as heat [1] [6]. |

| Visible Light | 400 – 700 nm | 4.3 x 10¹⁴ – 7.5 x 10¹⁴ Hz | Detected by the human eye; used in colorimetry and UV-Vis spectroscopy [1] [7]. |

| Ultraviolet (UV) | 10 – 400 nm | 7.5 x 10¹⁴ – 3 x 10¹⁶ Hz | Can cause chemical reactions and electronic transitions [1] [6]. |

| X-rays | 0.01 – 10 nm | 3 x 10¹⁶ – 3 x 10¹⁹ Hz | High energy, can penetrate soft tissues; used for crystallography and medical imaging [1] [3] [6]. |

| Gamma Rays | < 0.01 nm | > 3 x 10¹⁹ Hz | Highest energy; emitted from atomic nuclei [1] [6]. |

Fundamental Interaction Mechanisms

When electromagnetic radiation encounters matter, three primary interactions can occur, forming the basis for all spectroscopic techniques:

- Absorption: Radiation is absorbed by the material, promoting atoms or molecules to a higher energy state [1] [5]. The absorbed energy may excite electrons, cause molecular vibrations, or induce molecular rotations, depending on the radiation's energy.

- Emission: The material releases energy as photons when atoms or molecules return from an excited state to a lower energy state [1] [5].

- Transmission and Scattering: Radiation passes through the material with minimal interaction (transmission) or is redirected in various directions (scattering) [1] [5] [3].

The specific interaction that occurs depends on the energy of the incident radiation and the material's properties. The relationship is summarized in the following diagram.

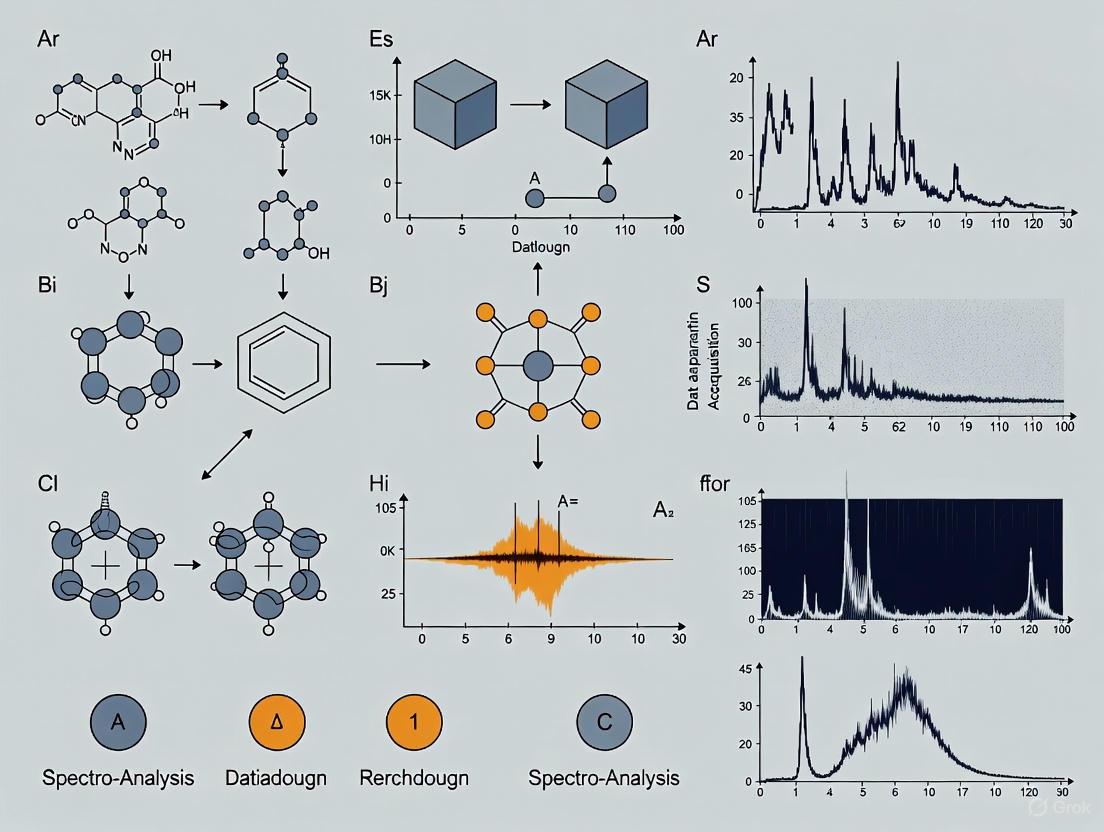

Diagram 1: Energy-matter interactions and spectroscopic analysis.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques by Region

Low-Energy Region (Radio Waves to Infrared)

Techniques in this region probe nuclear, rotational, and vibrational energy levels.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

- Principle: Uses radio waves to cause nuclear spin transitions in the presence of a strong magnetic field [3]. The local chemical environment of nuclei (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C) affects the resonance frequency.

- Experimental Protocol: A purified sample (solid or liquid) is placed in a strong, uniform magnetic field. A radiofrequency pulse is applied, and the resulting signal (free induction decay) is recorded as the nuclei relax. Fourier transformation converts this signal into a spectrum [5] [8].

- Analytical Significance: Primarily used for determining the structure of organic molecules, studying molecular dynamics, and analyzing polymer composition [5] [8].

Microwave Spectroscopy

Infrared (IR) and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

- Principle: Molecules absorb specific frequencies of infrared light that correspond to the natural frequencies of vibrational bonds (stretching, bending) [1] [9]. FTIR uses an interferometer to simultaneously collect all wavelengths, improving speed and sensitivity.

- Experimental Protocol: For transmission, a sample is ground with KBr and pressed into a pellet. For reflectance (e.g., ATR-FTIR), the sample is pressed against a crystal. The instrument irradiates the sample with IR light and measures which frequencies are absorbed [9] [5].

- Analytical Significance: The "fingerprint region" (often the mid-IR) is crucial for identifying unknown compounds by comparing their spectra to reference libraries [9]. It is indispensable for identifying functional groups and molecular structures in chemistry, materials science, and forensic analysis [1] [9] [5].

Medium-Energy Region (Visible and Ultraviolet Light)

This region is associated with electronic transitions in atoms and molecules.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

- Principle: Measures the absorption of UV or visible light, which promotes electrons in molecules from ground state to excited state [7]. Chromophores, functional groups that absorb light, are key to this technique.

- Experimental Protocol: A solution of the analyte is placed in a transparent cuvette. A spectrometer measures the intensity of light passing through the sample (I) versus a blank reference (I₀) across a wavelength range to calculate absorbance (A = log(I₀/I)) [7].

- Analytical Significance: Used for quantitative analysis, such as determining the concentration of DNA/RNA samples, monitoring reaction kinetics, and characterizing conjugated systems in organic chemistry [7].

Fluorescence (FL) Spectroscopy

- Principle: A molecule absorbs high-energy light (e.g., UV), becomes excited, and then emits lower-energy light (e.g., visible) upon returning to the ground state. The difference between absorption and emission maxima is the Stokes shift [7].

- Experimental Protocol: The sample is irradiated at a fixed excitation wavelength, and the emitted light is measured as a function of wavelength. Fluorometers often have two monochromators for independent control of excitation and emission wavelengths [7].

- Analytical Significance: Offers extremely high sensitivity and specificity for detecting and quantifying target molecules. Widely used in biochemistry, medical diagnostics, and DNA sequencing [7].

High-Energy Region (X-rays and Gamma Rays)

Techniques in this region probe inner-shell electrons and atomic nuclei.

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF)

- Principle: High-energy X-rays eject inner-shell electrons from atoms. When an outer-shell electron fills the vacancy, it emits a secondary (fluorescent) X-ray with an energy characteristic of the element [5].

- Experimental Protocol: The solid or liquid sample is irradiated with a primary X-ray beam. A detector analyzes the energies of the emitted fluorescent X-rays [5].

- Analytical Significance: A non-destructive technique for qualitative and quantitative elemental analysis of materials, from minerals to artworks [5].

X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

- Principle: A beam of X-rays is directed at a crystalline sample. The atoms in the crystal lattice cause the X-rays to diffract, producing a constructive interference pattern [5].

- Experimental Protocol: A powdered or single-crystal sample is mounted and rotated in the X-ray beam. A detector records the angles and intensities of the diffracted beams to produce a diffractogram [5].

- Analytical Significance: The primary method for determining the atomic and molecular structure of crystals, identifying crystalline phases, and analyzing material purity [5].

Gamma-ray Spectroscopy

Table 2 provides a direct comparison of the key spectroscopic techniques.

Table 2: Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques for Material Characterization

| Technique | EM Region | Probed Information | Common Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMR [5] [8] | Radio Waves | Molecular structure, nuclear environment, dynamics | Organic chemistry, polymer science, protein structure | Non-destructive; provides detailed atomic-level structural data. |

| FTIR [9] [5] | Infrared | Molecular vibrations, functional groups | Chemical ID, polymer characterization, forensic analysis | Fast, sensitive (ATR requires no sample prep); fingerprinting capability. |

| Raman [5] | Visible/Laser | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure | Mineralogy, carbon materials, pharmaceutical polymorphs | Non-destructive; complementary to IR; good for aqueous samples. |

| UV-Vis [1] [7] | UV/Visible | Electronic transitions, chromophores | Concentration measurement, reaction kinetics, band gap analysis | Quantitative; easy to use; often coupled with chromatography. |

| XRF [5] | X-rays | Elemental composition | Geology, metallurgy, environmental analysis | Non-destructive; bulk elemental analysis. |

| XRD [5] | X-rays | Crystal structure, phase identification | Materials science, pharmaceuticals, mineralogy | Definitive for crystalline phase identification. |

| LIBS [5] | Visible/Laser (emission) | Elemental composition | Field analysis, metallurgy, planetary exploration | Rapid, minimal sample preparation, in-situ capability. |

Advanced Applications and Integrated Workflows

Hyperspectral Imaging and Data Analysis

Imaging spectroscopy integrates spatial and chemical information, creating a "hyperspectral data cube" where each pixel contains a full spectrum [7]. This is generated by systematically rastering a spectrometer across a sample surface (or subsampling it) and compiling the spectral data into a three-dimensional block (X, Y spatial dimensions, and Z wavelength dimension) [7]. This data cube can be processed to create detailed 2D or 3D chemical images, revealing the distribution of specific components within a sample.

Diagram 2: Workflow for hyperspectral imaging and analysis.

The Role of Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing spectroscopy by enhancing computational predictions and processing complex experimental data [4]. ML models, particularly supervised learning, are trained on large datasets of theoretical or experimental spectra to predict electronic properties and molecular structures directly from spectral data [4]. This facilitates high-throughput screening and helps interpret spectra of complex, mixed samples, automating tasks that traditionally required extensive expert knowledge [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful spectroscopic analysis relies on specialized materials and reagents. Table 3 lists key items used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopy

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| KBr (Potassium Bromide) | An IR-transparent material used to prepare pellets for transmission FTIR analysis of solid samples [8]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) | Used as the solvent in NMR spectroscopy to provide a lock signal for the magnetic field and avoid interference from protonated solvents [8]. |

| ATR Crystals (e.g., Diamond, ZnSe) | Durable, high-refractive-index crystals used in Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FTIR for direct analysis of solids and liquids with minimal preparation [5]. |

| Reference Standards (e.g., Si powder for XRD) | Certified materials with known properties used to calibrate instruments (e.g., wavelength calibration in IR, angle calibration in XRD) and validate analytical methods [5]. |

| Sputter Coater (Gold/Palladium) | Used to coat non-conductive samples (e.g., polymers, biological specimens) with a thin, conductive metal layer prior to analysis by SEM to prevent charging [8]. |

| Staining Solutions (e.g., Uranyl Acetate) | Heavy metal salts used to stain biological or polymer samples for TEM analysis, enhancing contrast by scattering electrons [8]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Materials with certified composition for quantitative calibration in techniques like XRF and LIBS [5]. |

Spectroscopy, the scientific study of the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter, provides indispensable tools for determining the composition, structure, and behavior of materials across scientific disciplines [10]. These techniques all rely on three core interaction phenomena: absorption, emission, and scattering. For researchers in material characterization and drug development, understanding these fundamental processes is crucial for selecting the appropriate analytical technique, interpreting experimental data, and advancing research capabilities. Absorption occurs when a sample takes in photons from a radiation source, while emission involves the release of photons from an excited sample, and scattering describes the redirection of light upon interaction with matter [11] [10]. Each phenomenon provides distinct information about molecular structure, elemental composition, and material properties, forming the foundation for spectroscopic analysis in research and industry.

The principles of spectroscopy find applications ranging from elucidating molecular structures in novel pharmaceutical compounds to quantifying trace elements in battery materials and characterizing thermoelectric polymers [5] [12] [13]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of techniques based on these core phenomena, offering structured experimental data and methodologies to inform research decisions across scientific domains.

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis

The underlying principle of spectroscopy revolves around the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter. Electromagnetic radiation is characterized by its frequency (ν) and wavelength (λ), related by the speed of light: (c = νλ) [11]. When light interacts with a material, several phenomena can occur based on the energy of the photons and the electronic, vibrational, or rotational states of the material's atoms or molecules.

Figure 1: Classification of spectroscopic techniques based on core interaction phenomena with matter.

Absorption Phenomena

In absorption spectroscopy, matter absorbs specific wavelengths of incident radiation, causing transitions between energy states [11]. The absorbed energy promotes electrons to higher energy states or increases molecular vibrations, providing information about electronic structure, bond types, and functional groups. Quantitative analysis follows the Beer-Lambert law: (A = εlc), where (A) is absorbance, (ε) is molar absorptivity, (l) is path length, and (c) is concentration [11].

Emission Phenomena

Emission spectroscopy involves measuring radiation emitted by a sample after excitation by an external energy source [11] [10]. When atoms or molecules return to lower energy states, they emit photons at characteristic wavelengths. The emitted light's intensity is proportional to the concentration of the emitting species, enabling quantitative analysis.

Scattering Phenomena

Scattering spectroscopy measures radiation redirected by a sample [11]. In elastic scattering (Rayleigh), the photon's energy remains unchanged. In inelastic scattering (Raman), the photon's wavelength shifts due to energy transfer to or from the sample, providing vibrational information about molecular bonds [10].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Spectroscopic Interaction Phenomena

| Parameter | Absorption | Emission | Scattering |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Measurement of photons removed from incident light by sample | Measurement of photons released by excited sample | Measurement of photons redirected by sample |

| Energy Transition | Ground state → excited state | Excited state → ground state | Variable energy exchange |

| Information Obtained | Electronic structure, bond types, functional groups, concentration | Elemental identity, concentration, chemical environment | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure, chemical bonding |

| Key Techniques | UV-Vis, FTIR, AAS, XAS | AES, ICP-OES, Fluorescence, XRF | Raman, Rayleigh, Dynamic Light Scattering |

| Detection Sensitivity | Moderate to high (ppm to ppb for AAS) | Very high (ppb to ppt for ICP techniques) | Generally lower, but surface-sensitive |

| Quantitative Application | Excellent (Beer-Lambert law) | Excellent | Moderate, requires calibration |

| Typical Samples | Solutions, solids, thin films | Solutions, solids, gases | Solids, liquids, gases |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Absorption Spectroscopy Protocol: FTIR with ATR

Objective: To identify functional groups and molecular bonds in an unknown solid material using Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy with Attenuated Total Reflectance.

Materials and Reagents:

- FTIR spectrometer with ATR attachment

- ATR crystal (diamond, germanium, or zinc selenide)

- Standard reference materials for calibration

- High-purity solvents for cleaning

- Hydraulic press for solid powders

Procedure:

- Power on the FTIR spectrometer and allow it to warm up for 30 minutes.

- Clean the ATR crystal with appropriate solvent and conduct background measurement.

- For solid samples, place directly onto the ATR crystal; apply consistent pressure using the integrated anvil.

- For powders, use a hydraulic press to create a uniform pellet or place directly on crystal.

- Acquire spectrum in the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution.

- Perform 32 scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio.

- Process data: apply baseline correction, atmospheric suppression, and peak identification.

- Compare resulting spectrum to reference libraries for compound identification.

Data Interpretation: Identify characteristic absorption bands: C=O stretch at 1650-1750 cm⁻¹, O-H stretch at 3200-3600 cm⁻¹, C-H stretch at 2850-3000 cm⁻¹ [11] [10].

Emission Spectroscopy Protocol: ICP-OES

Objective: To quantitatively determine multiple elemental concentrations in a liquid sample using Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry.

Materials and Reagents:

- ICP-OES instrument with autosampler

- Argon gas supply

- Standard solutions for calibration curve

- High-purity nitric acid for digestion

- Deionized water

Procedure:

- Prepare sample through acid digestion if necessary, ensuring complete dissolution.

- Prepare standard solutions covering expected concentration range.

- Initialize plasma: set argon flow rates, power up RF generator, and ignite plasma.

- Allow system to stabilize for 30 minutes.

- Introduce samples via nebulizer and spray chamber.

- Monitor emission lines for target elements at characteristic wavelengths.

- Construct calibration curves from standard measurements.

- Calculate unknown concentrations from calibration curves.

- Run quality control samples to verify accuracy.

Data Interpretation: Element concentration is proportional to emission intensity at specific wavelengths. Detection limits typically range from ppb to ppm levels [12] [10].

Scattering Spectroscopy Protocol: Raman Spectroscopy

Objective: To obtain molecular vibrational information and identify chemical compounds through inelastic light scattering.

Materials and Reagents:

- Raman spectrometer with appropriate laser source

- Microscope attachment for micro-Raman

- Standard silicon wafer for calibration

- Glass slides or appropriate substrates

Procedure:

- Select appropriate laser wavelength to minimize fluorescence.

- Calibrate instrument using silicon reference peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹.

- Place sample on stage and focus laser spot.

- Set acquisition parameters: laser power, grating, integration time.

- Acquire spectrum with appropriate number of accumulations.

- Process data: apply cosmic ray removal, baseline correction, and smoothing.

- Identify characteristic Raman shifts for functional groups.

- Compare with spectral libraries for compound identification.

Data Interpretation: Raman shifts correspond to molecular vibrations. Key regions: C-C stretch (800-1200 cm⁻¹), C=C stretch (1500-1650 cm⁻¹), aromatic rings (around 1600 cm⁻¹) [5] [10].

Figure 2: Generalized workflow for spectroscopic analysis applicable across absorption, emission, and scattering techniques.

Comparative Performance Data

Table 2: Technical Performance Metrics of Spectroscopic Techniques Based on Core Phenomena

| Technique | Core Phenomenon | Detection Limits | Spatial Resolution | Information Dimension | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis | Absorption | ~10⁻⁶ M | ~1 mm | Electronic transitions | Concentration analysis, reaction monitoring |

| FTIR/ATR | Absorption | ~1% concentration | 10-100 μm | Molecular vibrations | Functional group identification, polymer characterization |

| AAS | Absorption | ppb level | N/A | Elemental composition | Trace metal analysis, environmental testing |

| Raman | Scattering | ~0.1-1% | ~1 μm | Molecular vibrations | Crystal structure, polymorph identification |

| ICP-OES | Emission | ppb level | N/A | Elemental composition | Multi-element analysis, material purity |

| XRF | Emission | ppm level | 10 μm - 1 mm | Elemental composition | Non-destructive elemental analysis |

| Fluorescence | Emission | ~nano-molar | ~200 nm | Electronic environment | Single-molecule detection, biological imaging |

Table 3: Experimental Considerations for Core Phenomenon-Based Techniques

| Parameter | Absorption Techniques | Emission Techniques | Scattering Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Moderate (varies by technique) | Extensive (often requires digestion) | Minimal (non-destructive) |

| Analysis Speed | Fast to moderate | Moderate to slow | Fast |

| Destructive Nature | Generally non-destructive | Often destructive | Non-destructive |

| Cost Factors | Low to moderate | High (instrumentation, gases) | Moderate to high |

| Operational Complexity | Low to moderate | High | Moderate |

| Sensitivity to Environment | Moderate (humidity affects IR) | Low (controlled plasma) | High (ambient light interference) |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (diamond, germanium) | Enables internal reflection for FTIR sampling | Solid and liquid analysis without extensive preparation |

| ICP Standards | Calibration and quantification | Elemental analysis via ICP-OES and ICP-MS |

| Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and method validation | Quality control across all spectroscopic techniques |

| High-Purity Solvents | Sample preparation and dilution | Minimizing background interference in UV-Vis and fluorescence |

| Specialized Gases (Argon, Nitrogen) | Plasma generation and atmospheric control | ICP techniques, FTIR purge systems |

| Calibration References (Silicon wafer) | Wavelength and intensity calibration | Raman spectroscopy standardization |

| Laser Sources | Excitation for Raman and LIBS | Enabling scattering and emission measurements |

Applications in Material Characterization Research

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

In drug development, spectroscopic techniques provide critical information throughout the research pipeline. FTIR and Raman spectroscopy identify functional groups and polymorphs in active pharmaceutical ingredients, affecting bioavailability and stability [10]. UV-Vis spectroscopy quantifies drug concentrations in dissolution studies, while fluorescence spectroscopy enables high-sensitivity detection of biological interactions and cellular uptake. The non-destructive nature of many scattering techniques allows analysis of final dosage forms without compromising product integrity.

Advanced Materials Research

Spectroscopic methods are indispensable for characterizing novel materials, from battery components to thermoelectric polymers [12] [13]. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) reveals surface chemistry and oxidation states in electrode materials. NMR spectroscopy studies local environments and ion mobility in novel electrolyte systems. For thermoelectric materials like PEDOT:PSS, UV-Vis-NIR spectroscopy determines electronic structure, while Raman spectroscopy monitors structural changes during doping processes that enhance thermoelectric performance.

Industrial and Quality Control Applications

The robustness of spectroscopic techniques enables widespread industrial implementation. Portable Raman spectrometers allow field identification of unknown materials, while FTIR provides rapid verification of raw material identity in pharmaceutical manufacturing [10]. XRF analyzers perform non-destructive elemental analysis of alloys and mining samples. Emission techniques like ICP-OES conduct routine quality checks for trace metal impurities in electronic components and battery materials, ensuring product safety and performance [12].

Absorption, emission, and scattering phenomena form the foundation of spectroscopic analysis, each offering distinct advantages for material characterization. Absorption techniques provide excellent quantitative capabilities and molecular structure information, emission methods offer exceptional sensitivity for elemental analysis, and scattering approaches deliver non-destructive, surface-sensitive characterization. The continuing evolution of these techniques, including integration with machine learning and development of portable instrumentation, expands their applications across research and industry. Understanding the fundamental principles, performance characteristics, and experimental requirements of each approach enables researchers to select optimal methodologies for specific analytical challenges in material science, pharmaceutical development, and beyond.

Spectroscopy, the investigation of spectra produced when matter interacts with electromagnetic radiation, serves as a cornerstone analytical technique across scientific disciplines [14]. This guide provides a detailed comparative analysis of atomic and molecular spectroscopy, two fundamental approaches with distinct principles and applications. For researchers engaged in material characterization, understanding the nuanced differences between these techniques is paramount for selecting the appropriate analytical method. Atomic spectroscopy focuses on the energy transitions of electrons within individual atoms, providing precise elemental identification and quantification [15]. In contrast, molecular spectroscopy examines the vibrational, rotational, and electronic behaviors of entire molecules, yielding insights into chemical composition, structure, and bonding [15] [14].

The selection between atomic and molecular spectroscopic methods directly impacts the quality and type of information obtained in research. Atomic techniques excel at detecting trace metals and determining elemental concentrations, even in complex sample matrices [16]. Molecular techniques, however, provide a fingerprint of molecular identity, revealing detailed information about functional groups, molecular structure, and chemical environment [14]. This comparative analysis will explore the fundamental principles, methodological approaches, and practical applications of these complementary techniques within the context of material characterization research.

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

Atomic Spectroscopy: Electronic Transitions in Atoms

Atomic spectroscopy operates on the principle that electrons in atoms exist in discrete energy levels [14]. When an electron absorbs energy, it transitions to a higher energy orbital; when it returns to a lower energy state, it emits energy in the form of photons [14]. The energy of these photons corresponds precisely to the difference between the two atomic energy levels, resulting in the characteristic line spectra that serve as unique fingerprints for each element [15] [14]. These narrow, well-defined spectral lines typically range from 3-10 nm in width and form the basis for both qualitative identification and quantitative analysis of elements [16] [17].

The fundamental processes underlying atomic spectroscopy include atomic absorption, emission, and fluorescence. In atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS), ground-state atoms absorb light at characteristic wavelengths [16] [17]. Atomic emission spectrometry (AES) involves measuring light emitted when excited atoms return to lower energy states [16]. Atomic fluorescence spectrometry (AFS) detects radiation emitted after atoms are excited by photon absorption [16]. These processes all rely on the quantized nature of atomic energy levels, which produces the sharp, discrete spectral lines that distinguish atomic spectroscopy from molecular techniques.

Molecular Spectroscopy: Complex Energy Transitions

Molecular spectroscopy encompasses a more complex hierarchy of energy transitions due to the additional degrees of freedom in molecules. Unlike atoms, molecules possess three types of quantized energy states: electronic, vibrational, and rotational [14] [17]. According to the Born-Oppenheimer approximation, the total energy of a molecule is the sum of contributions from electronic, vibrational, and rotational motions, with translational energy being negligible [17]. This complexity gives rise to three primary types of molecular spectra, each corresponding to different energy transitions and spectral regions.

Pure rotational spectra result from transitions between rotational energy levels within the same vibrational state and are observed in the far-infrared and microwave spectral regions [14] [17]. These transitions require the least energy and provide information about molecular geometry and bond lengths.

Vibrational-rotational spectra occur when molecules transition between vibrational levels, with accompanying rotational changes [14]. These mid-infrared spectra (often called IR spectra) reveal details about chemical bonds and functional groups.

Electronic band spectra involve transitions between electronic energy levels, accompanied by both vibrational and rotational changes [14]. These high-energy transitions observed in ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) regions produce characteristic band patterns rather than discrete lines due to the superposition of numerous vibrational and rotational transitions [14].

The hierarchical relationship between these transitions—with rotational requiring the least energy, vibrational requiring intermediate energy, and electronic transitions requiring the most energy—explains why molecular spectra appear as broad bands rather than the sharp lines characteristic of atomic spectra [14].

Figure 1: Fundamental distinction between atomic and molecular spectroscopy showing transition types and spectral characteristics.

Comparative Analysis: Key Parameters and Technical Specifications

The practical implementation of atomic and molecular spectroscopic techniques differs significantly in terms of instrumentation, sample requirements, and analytical capabilities. The table below summarizes the core differences between these approaches.

Table 1: Technical comparison of atomic versus molecular spectroscopy techniques

| Parameter | Atomic Spectroscopy | Molecular Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Elemental composition at atomic level [15] | Molecular structures and bonds [15] |

| Transitions Studied | Electronic energy level transitions [15] [14] | Vibrational, rotational, and electronic transitions within molecules [15] [14] |

| Spectral Characteristics | Narrow, discrete lines (3-10 nm width) [17] | Broad bands of closely spaced lines [14] [17] |

| Sample Complexity | Simpler samples, often minimal preparation [15] | More complex, often needs extensive preparation [15] |

| Detection Sensitivity | High for trace elements and isotopes (parts-per-trillion) [15] [16] | High for specific molecules and functional groups [15] |

| Analytical Scope | Elemental and isotopic analysis [15] | Molecular composition and structure [15] |

| Common Techniques | AAS, ICP-OES, ICP-MS, XRF [16] [18] | IR, Raman, UV-Vis, NMR [15] [14] |

| Sample States | Solid, liquid, gas [15] | Liquid, gas, some solids with preparation [15] |

The instrumentation for atomic spectroscopy typically requires high-temperature atomization sources such as flames, furnaces, or inductively coupled plasma (ICP) to break chemical bonds and create free atoms [16]. Molecular spectroscopy generally employs less energetic sample interactions, preserving molecular integrity while probing transitions between quantum states [14] [17]. This fundamental difference in sample treatment directly influences the type of information obtained and the applications for which each technique is best suited.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Atomic Spectroscopy: Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (GFAAS)

Protocol Objective: Determination of trace levels of toxic metals (e.g., cadmium and lead) in complex biological matrices with minimal sample pretreatment [18].

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Introduction: Liquid samples are injected directly into graphite furnace; solid samples may require acid digestion [16].

- Drying Stage: Temperature ramp to ~100°C to remove solvent without splattering.

- Pyrolysis/Ashing: Moderate heating (350-500°C) to remove organic matrix without volatilizing target analytes.

- Atomization: Rapid temperature increase to 2000-2500°C, vaporizing and atomizing the sample to create free atoms in the light path.

- Two-Stage Probe Atomization: Specialized approach for complex matrices like bovine blood, using sequential atomization to separate matrix effects from analyte signal [18].

- Detection: Measurement of light absorption at element-specific wavelengths using hollow cathode lamps.

- Quantification: Comparison of absorption signals to calibration curves prepared with matrix-matched standards.

Critical Parameters: Temperature program optimization, background correction, matrix modification to prevent interference, and careful calibration are essential for accurate results [16] [18].

Figure 2: GFAAS experimental workflow for trace metal analysis in complex matrices.

Molecular Spectroscopy: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Protocol Objective: Molecular identification and functional group analysis in solid-state pharmaceutical compounds.

Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation:

- KBr Pellet Method: Mix 1-2 mg sample with 200 mg dried potassium bromide; compress under vacuum to form transparent pellet.

- Alternative: Use attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory for minimal sample preparation.

- Instrument Setup: Purge spectrometer with dry air or nitrogen to minimize atmospheric CO₂ and H₂O interference.

- Background Scan: Collect reference spectrum without sample present.

- Sample Analysis: Acquire interferogram with sample; Fourier transform to generate absorption spectrum.

- Spectral Collection: Typically 16-64 scans at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution between 4000-400 cm⁻¹.

- Data Processing: Background subtraction, baseline correction, and peak identification.

- Interpretation: Correlation of absorption bands to specific molecular vibrations and functional groups.

Critical Parameters: Sample preparation consistency, proper background subtraction, resolution settings, and humidity control significantly impact spectral quality and reproducibility.

Research Applications in Material Characterization and Drug Development

Atomic Spectroscopy Applications

Atomic spectroscopic techniques provide critical elemental data across diverse research applications:

Pharmaceutical Quality Control: Detection of toxic heavy metals and catalyst residues in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and excipients to comply with regulatory requirements [17]. GFAAS methods enable determination of trace levels of cadmium and lead in drug products with minimal sample pretreatment [18].

Biomedical Research: Analysis of essential and toxic elements in biological tissues and fluids. The development of novel atomization techniques has enabled direct analysis of complex matrices like whole blood with reduced interference from organic components [18].

Environmental Monitoring: Quantification of trace metals in soils, geological samples, and water sources to assess contamination levels and ecosystem health [17]. Advanced techniques like laser ablation ICP-MS allow direct solid sampling with minimal preparation [18].

Material Science: Characterization of elemental composition in nanomaterials, alloys, and electronic materials. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) has emerged as a powerful technique for direct elemental analysis of diverse solid samples without extensive preparation [18].

Molecular Spectroscopy Applications

Molecular spectroscopic methods deliver structural insights across research domains:

Pharmaceutical Development: Drug polymorph identification, formulation stability testing, and reaction monitoring. IR and Raman spectroscopy provide fingerprint regions unique to specific molecular structures and crystalline forms [14].

Biomolecular Research: Protein secondary structure analysis, lipid membrane characterization, and biomarker detection. Molecular absorption spectroscopy aids in studying biomolecules and detecting disease biomarkers in complex biological mixtures [17].

Polymer and Materials Science: Chemical structure determination, cross-linking density measurement, and degradation studies. Silicone adhesive cross-linking can be monitored through specific vibrational signatures of catalytic organometallic compounds [16].

Forensic and Environmental Analysis: Chemical fingerprinting of unknown compounds, pollutant identification, and mixture analysis. The non-destructive nature of many molecular techniques preserves sample integrity for subsequent analyses [17].

Table 2: Application-specific comparison in pharmaceutical and materials research

| Research Context | Atomic Spectroscopy Application | Molecular Spectroscopy Application |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Quality Control | Trace metal impurities in APIs [17] | Polymorph identification and excipient characterization [14] |

| Biomolecular Research | Essential element quantification in tissues [16] | Protein secondary structure analysis [17] |

| Material Characterization | Elemental composition of alloys and nanomaterials [18] | Polymer degradation and cross-linking studies [16] |

| Environmental Analysis | Heavy metal detection in soil and water [17] | Pollutant identification and chemical fingerprinting [17] |

| Forensic Science | Gunshot residue analysis and glass composition [16] | Illicit drug identification and paint chip analysis [15] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of spectroscopic techniques requires specific reagents and reference materials to ensure analytical accuracy and reproducibility.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for spectroscopic analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Matrix Modifiers (e.g., Pd, Mg, NH₄⁺ salts) | Reduce volatility of analytes, modify matrix properties during thermal decomposition | GFAAS analysis of complex biological samples [16] |

| Certified Reference Materials | Method validation, calibration verification, quality assurance | Both atomic and molecular spectroscopy quantification [16] |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps | Element-specific light source for atomic absorption measurements | AAS for specific element detection [17] |

| Deuterium Lamps | Background correction source for UV measurements | AAS and UV-Vis molecular spectroscopy [17] |

| FTIR Grade KBr | Non-absorbing matrix for sample preparation in infrared spectroscopy | FTIR sample preparation for solid materials |

| ICP-Grade Acids | High purity acids for sample digestion and dilution | Sample preparation for ICP-OES and ICP-MS techniques |

| Isotopically Enriched Standards | Isotope dilution mass spectrometry for precise quantification | ICP-MS for accurate elemental quantification |

Technique Selection Guidelines

Choosing between atomic and molecular spectroscopic methods depends on specific research questions and analytical requirements. The following guidelines facilitate appropriate technique selection:

Elemental vs. Molecular Information: Select atomic spectroscopy for elemental composition and quantification; choose molecular spectroscopy for structural characterization and functional group identification [15] [17].

Detection Sensitivity Requirements: Atomic techniques generally offer superior sensitivity for trace metal detection (parts-per-trillion levels), while molecular methods excel at detecting specific functional groups and molecular motifs [15].

Sample Compatibility: Consider atomic spectroscopy for samples that can be digested or atomized; molecular spectroscopy may be preferable for samples requiring non-destructive analysis or structural preservation [15] [17].

Regulatory Compliance: Atomic spectroscopy is often mandated for elemental impurity testing per pharmacopeial guidelines, while molecular techniques fulfill identification and characterization requirements [16] [17].

Resource Constraints: Molecular spectroscopy often offers greater field portability, while atomic techniques typically require laboratory infrastructure, though portable atomic spectrometers are increasingly available [15] [18].

Emerging trends include the integration of multiple techniques for comprehensive analysis, development of portable instrumentation for field applications, and advancement of laser-based methods like LIBS and LA-ICP-MS for direct solid sampling [18]. These developments continue to expand the applications and capabilities of both atomic and molecular spectroscopic methods in research environments.

Atomic and molecular spectroscopy offer complementary approaches to material characterization with distinct strengths and applications. Atomic spectroscopy provides unparalleled sensitivity for elemental analysis and quantification, while molecular spectroscopy delivers detailed structural insights through vibrational, rotational, and electronic transitions. The selection between these techniques should be guided by specific research objectives, sample characteristics, and information requirements. Ongoing technological advancements continue to enhance the sensitivity, accessibility, and application scope of both approaches, maintaining their critical role in scientific research and material characterization. For comprehensive analysis, researchers often employ both techniques to obtain complete elemental and structural information, leveraging the respective strengths of each methodological approach.

Spectral Fingerprints as Molecular Identification Tools

Spectral fingerprinting has emerged as a powerful methodology for the rapid classification and identification of complex materials across scientific disciplines. This comparative analysis examines the experimental performance of ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis), Fourier transform infrared (FTIR), and hyperspectral coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering (HS-CARS) spectroscopy for molecular characterization. Quantitative evaluation reveals distinct operational parameters, detection capabilities, and application-specific advantages for each technique. FTIR demonstrates superior performance for enzymatic activity monitoring with 95% accuracy in distinguishing laccase reaction patterns, while HS-CARS achieves exceptional single-cell resolution for drug localization with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.942. UV-Vis spectral fingerprinting combined with analysis of variance-principal component analysis (ANOVA-PCA) successfully differentiates broccoli cultivars with 68.3% variance explained by growing conditions. These findings establish that technique selection must be guided by specific research objectives, target analytes, and required detection sensitivity.

Spectral fingerprinting represents a rapid analytical approach for comparing and classifying biological and chemical materials based on their unique spectral patterns without prior separation of components [19]. The fundamental principle underpinning this methodology is that genetic, environmental, and structural factors influence molecular composition, thereby producing distinctive spectral signatures that serve as identifying "fingerprints" [19]. Unlike targeted analytical approaches that focus on specific compounds, spectral fingerprinting leverages the complete pattern of responses across spectral ranges, making it particularly valuable for characterizing complex mixtures where multiple components contribute to the overall profile.

The successful application of spectral fingerprinting depends critically on the magnitude of variation induced by experimental factors compared to natural variation among individual samples [19]. This technique has gained significant traction across diverse fields including materials science, where it fingerprints defects in solids [20]; environmental science, where it characterizes sediment sources [21]; pharmaceutical research, where it localizes drug distributions [22]; and food science, where it differentiates plant cultivars and growing conditions [19]. The versatility of spectral fingerprinting stems from its implementation across multiple spectroscopic platforms, each offering unique advantages for specific analytical challenges.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques for Molecular Fingerprinting

| Technique | Spectral Range | Samples Analyzed | Detection Limit | Accuracy/ Discrimination Power | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis | 220-380 nm | Broccoli extracts | Not specified | 68.3% variance from treatments [19] | Differentiating plant cultivars and growing conditions [19] |

| FTIR | Mid-infrared | Enzyme reactions (laccases) | >60 mg [21] | 95% accuracy for laccase distinction [23] | Enzyme activity measurement, reaction monitoring [23] |

| HS-CARS | Vibrational fingerprint region | Drug compounds in liver tissue | Single-cell resolution [22] | AUC = 0.942 (high-dose drug) [22] | Drug localization, biological sampling [22] |

| VNIR-SWIR | Visible-near infrared-shortwave infrared | Sediment samples | >60 mg [21] | Source contribution modeling [21] | Sediment source discrimination, environmental tracing [21] |

Operational Characteristics and Data Analysis Requirements

Table 2: Operational Parameters and Data Processing Requirements

| Technique | Sample Preparation | Measurement Time | Multivariate Analysis Methods | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis | Extraction with methanol-water (60:40), centrifugation, 50-fold dilution [19] | Rapid scan (specific time not indicated) | ANOVA-PCA, derivative spectra, normalization [19] | Simple instrumentation, cost-effective, high sample throughput |

| FTIR | Direct measurement of powdered solids or enzyme reactions [23] | Real-time monitoring (specific duration not indicated) | PARAFAC, PCA [23] | Label-free, non-destructive, chemical bond specificity |

| HS-CARS | Tissue sectioning, no staining/labeling required [22] | Imaging-based (duration depends on area) | Deep learning (Hyperspectral Attention Net) [22] | High spatial resolution, minimal background, subcellular localization |

| VNIR-SWIR | Drying, no chemical treatment [21] | Rapid measurement (specific time not indicated) | PCA, mixing models [21] | Minimal preparation, cost-efficient for large sample sets |

Performance data extracted from multiple studies demonstrates distinctive capability profiles across techniques. UV-Vis spectroscopy, while utilizing broad absorption bands with theoretically lower information content, effectively differentiated broccoli cultivars and growing conditions when combined with appropriate multivariate analysis [19]. FTIR spectroscopy provided exceptional capability for monitoring enzymatic reactions in real-time, successfully distinguishing reaction patterns of different laccases with high accuracy [23]. The most technologically advanced approach, HS-CARS microscopy, achieved remarkable spatial resolution for drug localization within tissues when enhanced with deep learning algorithms [22].

Experimental Protocols for Spectral Fingerprinting

UV-Vis Spectral Fingerprinting for Plant Material Differentiation

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Obtain freeze-dried, powdered plant materials (e.g., broccoli cultivars) and sieve through standard 20 mesh sieves (particle size <0.850 mm) to ensure uniform homogenization [19].

- Weigh samples into screw cap vials and add methanol-water extractant (60:40, v/v) at a ratio of 5 mL per sample aliquot.

- Sonicate the mixture in a water bath at 40°C for 30 minutes, then centrifuge at low speed (5000 rpm) for 10 minutes [19].

- Transfer the supernatant to a separate vial and repeat extraction twice more with 2.5 mL of fresh extractant each time.

- Combine all supernatants and adjust final volume to 10 mL with methanol-water (60:40, v/v).

- Filter an appropriate aliquot through a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) syringe filter (pore size = 0.45 µm) prior to analysis.

- Dilute extracts 50-fold for UV spectral scans to remain within the linear absorbance range [19].

Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire spectral fingerprints between 220-380 nm using a spectrophotometer.

- Convert spectral data to ASCII files for chemometric analysis.

- Preprocess data by transforming to first derivative, applying seven-point second-order polynomial smoothing, and vector normalization [19].

- Apply ANOVA-PCA to partition data into subset matrices corresponding to each experimental factor.

- Calculate sums of squares to quantify percentage variance contribution from cultivar, treatment, and analytical repeatability [19].

HS-CARS Microscopy for Drug Fingerprinting

Sample Preparation and Imaging:

- Collect tissue samples (e.g., murine liver tissues) from subjects following drug administration.

- Prepare tissue sections using standard cryostat or microtome methods without chemical fixation or staining to maintain endogenous vibrational contrast [22].

- Mount tissue sections on appropriate slides compatible with CARS microscopy.

- Acquire hyperspectral CARS images using a laser scanning microscope equipped with dual-wavelength lasers for pump and Stokes beams.

- Collect spectral data across the vibrational fingerprint region (typically 500-3100 cm⁻¹) with spatial resolution sufficient for single-cell analysis [22].

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Train a Hyperspectral Attention Net (HAN) using a multiple instance learning framework with whole-image labels.

- Implement attention mechanisms to highlight informative regions within samples without pixel-level annotations.

- Validate model performance using receiver operating characteristic curves and calculate area under the curve (AUC) metrics [22].

- Compare drug localization patterns with complementary validation methods such as in situ hybridization staining.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectral Fingerprinting

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | UV-Vis capability (200-400 nm) | Acquisition of electronic transition spectra [19] |

| FTIR Spectrometer | With real-time monitoring capability | Monitoring enzymatic reactions and chemical transformations [23] |

| HS-CARS Microscope | Hyperspectral imaging with laser sources | Label-free chemical imaging at single-cell resolution [22] |

| Centrifuge | Capable of 5000 rpm operation | Separation of solid residues from extracts [19] |

| Sonication Bath | Temperature control (40°C capability) | Efficient extraction of analytes from solid matrices [19] |

| Syringe Filters | PVDF, 0.45 µm pore size | Removal of particulate matter prior to analysis [19] |

| Solvents | HPLC-grade methanol, water | Extraction medium for plant metabolites [19] |

| Chemometrics Software | PCA, ANOVA-PCA, PARAFAC capability | Multivariate analysis of complex spectral data [19] [23] |

This comprehensive comparison of spectral fingerprinting techniques demonstrates that methodological selection must align with specific research requirements. UV-Vis spectroscopy offers a cost-effective solution for high-throughput screening of plant materials and agricultural products, particularly when combined with ANOVA-PCA for variance decomposition [19]. FTIR spectroscopy provides exceptional capabilities for monitoring enzymatic reactions and chemical transformations in real-time with high specificity for molecular bond vibrations [23]. HS-CARS microscopy represents the cutting edge for spatially-resolved chemical analysis, enabling drug localization at single-cell resolution when enhanced with deep learning approaches [22].

The evolving landscape of spectral fingerprinting continues to expand with advancements in multivariate analysis, machine learning integration, and computational power. Future developments will likely focus on increasing spatial and temporal resolution, improving detection sensitivity for trace components, and establishing standardized spectral libraries for cross-laboratory comparisons. For researchers embarking on material characterization projects, the optimal technique balances analytical performance with practical considerations including sample availability, preparation requirements, and available instrumentation.

Non-Destructive Nature and Versatility of Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectroscopic analysis encompasses a suite of analytical techniques that study the absorption and emission of electromagnetic radiation by matter. These techniques are pivotal in material characterization research, providing tools for examining drug identity and purity, crystalline structures, and interactions between active ingredients and excipients [24]. A key advantage of many spectroscopic methods is their non-destructive nature, allowing samples to be retained for future studies after analysis [25]. Furthermore, their versatility enables application across diverse sample types—including gases, liquids, and solids—and a wide range of scientific and industrial fields from pharmaceutical development to archaeological authentication [26] [24].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of major spectroscopic techniques, emphasizing their non-destructive characteristics and application breadth. We objectively evaluate performance through experimental data and detailed methodologies, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate techniques based on specific material characterization needs within pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Pharmaceutical Applications of Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Primary Principle | Sample Form | Non-Destructive | Key Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR [27] [28] | Molecular bond vibrations in infrared light | Solid, Liquid, Gas | Yes | Chemical bond/functional group identification, drug stability testing [27] |

| Raman [27] | Inelastic scattering of light | Solid, Liquid | Yes | Molecular imaging, fingerprinting, process monitoring [27] |

| NMR [27] [25] | Nuclear spin transitions in magnetic field | Liquid, Solid | Yes | 3D molecular structure determination, conformational analysis [27] [25] |

| UV-Vis [27] | Electronic transitions | Liquid | Yes | Concentration measurement, absorbance analysis [27] |

| Fluorescence [27] | Light emission after excitation | Liquid | Yes | Molecular interactions, kinetics, protein stability [27] |

| MRR [29] | Molecular rotation transitions | Gas, Vapor | Yes | Residual solvent analysis, chiral purity assessment [29] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Limitations for Material Characterization

| Technique | Sensitivity | Spectral Resolution | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR [27] [28] | High for functional groups | ~0.5-4 cm⁻¹ | Rapid analysis, minimal sample prep, broad applicability | Water interference, weak for non-polar bonds |

| Raman [27] | Lower without SERS/TERS | ~1-2 cm⁻¹ | Minimal water interference, works with aqueous samples | Fluorescence background, poor for metals |

| NMR [25] | Low (requires sufficient concentration) | <1 Hz | Atomic-level structural information, quantitative | High cost, complex data interpretation, low sensitivity |

| UV-Vis [27] | Moderate (μM-nM) | 1-2 nm | Simple operation, excellent for quantification | Limited structural information, overlapping spectra |

| Fluorescence [27] | Very high (pM) | 1-5 nm | Extreme sensitivity, real-time monitoring | Requires fluorophores, photobleaching potential |

| MRR [29] | High (ppm-ppb) | <1 kHz | Unambiguous isomer identification, no separation needed | Limited to volatile compounds, emerging technology |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

FTIR for Protein Drug Stability Studies

Objective: To assess the stability of protein drugs under various storage conditions by analyzing secondary structure changes [27].

Materials: Protein drug samples, FTIR spectrometer with ATR accessory, temperature-controlled storage chambers, Python software with hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) capabilities.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Aliquot protein drug samples into weekly portions. Store under controlled temperature conditions (e.g., 4°C, 25°C, 40°C) to simulate various storage environments.

- FTIR Analysis: For each weekly time point, analyze samples using ATR-FTIR without dilution or preparation. Collect spectra in the mid-IR region (4000-400 cm⁻¹) with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, averaging 64 scans per spectrum.

- Data Processing: Process spectra using second-derivative transformation and Fourier deconvolution to enhance resolution of amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹). Subject processed spectra to hierarchical cluster analysis using Python to assess similarity of secondary protein structures across samples.

- Interpretation: Compare cluster patterns to determine structural similarity between samples stored under different conditions. Closer clustering indicates maintained stability, while divergent clustering suggests structural degradation [27].

Inline Raman for Bioprocess Monitoring

Objective: To monitor product aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing in real-time [27].

Materials: Raman spectrometer with fiber optic probe, bioreactor, robotic automation system, machine learning algorithms for chemometric modeling.

Methodology:

- System Setup: Integrate Raman probe directly into bioreactor vessel using sterile immersion probe. Connect to spectrometer with automated sampling capability.

- Calibration: Employ robotic automation to reduce calibration effort. Develop multivariate calibration models using machine learning algorithms correlating spectral features with product quality attributes.

- Data Collection: Acquire spectra every 38 seconds using automated sampling. Preprocess spectra using smoothing, baseline correction, and normalization algorithms.

- Real-time Analysis: Apply chemometric models to processed spectra for continuous measurement of aggregation and fragmentation. Implement control charts to detect normal and abnormal process conditions, including potential bacterial contamination [27].

Non-Invasive Fluorescence for Protein Stability

Objective: To monitor heat- and surfactant-induced denaturation of proteins without removing samples from vials [27].

Materials: Fluorometer with polarizing filters, sealed vials containing protein samples (e.g., bovine serum albumin), temperature control unit, circular dichroism spectrometer for validation.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare protein solutions in vials with varying concentrations of denaturing agents or under different temperature conditions.

- In-Vial Measurement: Use bespoke fluorescence polarization setup with polarizing filters to measure anisotropy without opening vials. Excitate at 280 nm (tryptophan residues) and measure emission at 340 nm.

- Data Acquisition: Record fluorescence polarization values over time as denaturation proceeds. Compare with control samples maintained under native conditions.

- Validation: Correlate fluorescence polarization measurements with circular dichroism spectra and size-exclusion chromatography analyses to validate denaturation state without compromising sample sterility [27].

Spectroscopic Analysis Workflow for Material Characterization

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., D₂O, CDCl₃) | Provides locking signal for NMR without interfering with sample | NMR spectroscopy for molecular structure determination [25] |

| Chiral Tag Molecules | Forms transient diastereomeric complexes with chiral analytes | MRR spectroscopy for enantiomeric excess determination [29] |

| ATR Crystals (e.g., diamond, ZnSe) | Enables internal reflection for direct solid/liquid analysis | FTIR spectroscopy with minimal sample preparation [28] [26] |

| Size Exclusion Columns | Separates protein-metal complexes from free metals | SEC-ICP-MS for studying metal-protein interactions [27] |

| Q-body Immunosensors | Fluorescently detects secreted proteins in microemulsions | Fluorescence-activated screening of high-producing bacterial strains [27] |

| Plasmonic Nanoparticles (Au/Ag) | Enhances Raman scattering through surface enhancement | SERS for detecting low concentration substances [27] |

Data Preprocessing and Advanced Computational Methods

Modern spectroscopic analysis relies heavily on advanced preprocessing and computational methods to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data. As spectroscopic signals are inherently weak and prone to interference from environmental noise, instrumental artifacts, sample impurities, and scattering effects, systematic preprocessing is essential for accurate characterization [30].

Critical preprocessing steps include cosmic ray removal for spike artifacts, baseline correction for low-frequency drift suppression, scattering correction, intensity normalization to mitigate systematic errors, and spectral derivatives for feature enhancement [30]. These methods are particularly important for machine learning applications, where unprocessed spectral data can introduce artifacts and bias feature extraction.

The field is currently undergoing a transformative shift driven by three key innovations: context-aware adaptive processing, physics-constrained data fusion, and intelligent spectral enhancement. These cutting-edge approaches enable unprecedented detection sensitivity achieving sub-ppm levels while maintaining >99% classification accuracy, with transformative applications spanning pharmaceutical quality control [30].

Common chemometric algorithms used in conjunction with these preprocessing methods include principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares (PLS), multivariate curve resolution (MCR), and artificial neural networks (ANNs) [31]. In recent years, artificial intelligence has revolutionized process monitoring through its ability to extract intricate nonlinear patterns from large spectroscopic datasets, enabling development of soft sensors that enhance accuracy and robustness in pharmaceutical bioprocessing [31].

Spectral Data Preprocessing Pipeline

This comparative analysis demonstrates that spectroscopic techniques offer powerful, non-destructive approaches for material characterization with distinctive strengths and applications. FTIR provides rapid chemical bonding information, Raman enables non-invasive process monitoring, NMR delivers atomic-level structural details, and fluorescence offers exceptional sensitivity for molecular interactions. The emerging technique of MRR spectroscopy shows particular promise for analyzing complex mixtures and chiral compounds without pre-separation.

The versatility of these methods continues to expand with advancements in computational analytics, machine learning integration, and preprocessing algorithms. Selection of an appropriate spectroscopic technique depends on multiple factors including sample characteristics, information requirements, detection sensitivity needs, and operational constraints. Understanding the comparative capabilities and limitations of each method enables researchers to strategically implement these tools for comprehensive material characterization throughout drug development and manufacturing processes.

Methodological Approaches and Real-World Applications Across Industries

The advancement of material characterization research is intrinsically linked to the development and application of sophisticated spectroscopic techniques. These methods provide researchers with the critical data needed to decipher the chemical composition, molecular structure, and elemental makeup of diverse materials, from novel battery components to geological specimens and pharmaceutical compounds. This guide presents a comparative analysis of five pivotal techniques—Raman Spectroscopy, Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), and Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS). By objectively evaluating their fundamental principles, performance capabilities, and experimental requirements, this article serves as a strategic resource for scientists and drug development professionals in selecting the optimal analytical tool for their specific research context.

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The following table summarizes the core characteristics and performance metrics of the five analytical techniques, providing a high-level overview for initial comparison.

Table 1: Comparative overview of key spectroscopic techniques

| Technique | Primary Information | Typical Detection Limits | Sample Throughput | Sample Preparation Needs | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure, phase identification [32] | ~0.1-1 wt% | Moderate to High | Minimal (often non-destructive) | Non-destructive; provides molecular fingerprint; can be used in aqueous environments |

| FTIR | Functional groups, chemical bonding, molecular structure [28] | ~0.1-1 wt% | High | Minimal to Moderate (varies with sampling mode: ATR, transmission) | Excellent for organic functional group identification; high sensitivity |

| XRF | Elemental composition (Na to U) [33] | ~1-100 ppm | Very High | Minimal (often non-destructive) | Non-destructive; rapid qualitative and quantitative analysis; portable systems available |

| ICP-MS | Elemental & isotopic composition, trace metals [34] [35] | ~ppt to ppq (parts-per-trillion to -quadrillion) | Moderate | Extensive (digestion/dissolution typically required) | Exceptional sensitivity and detection limits; wide dynamic range; isotopic capability |

| LIBS | Elemental composition (incl. light elements like H, Li, Be) [36] | ~0.1-100 ppm | Very High | Minimal (micro-destructive) | Rapid, in-situ analysis; requires little to no sample prep; portable and standoff capability |

Detailed Technique Profiles and Experimental Protocols

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Principle and Workflow: FTIR spectroscopy is based on the absorption of infrared light by chemical bonds in a molecule. When IR radiation is applied, chemical bonds vibrate at specific frequencies, absorbing energy at characteristic wavelengths that serve as a molecular fingerprint [28]. The core components of an FTIR spectrometer include an IR source, an interferometer with a moving mirror, a sample compartment, and a detector. The instrument does not measure one wavelength at a time; instead, it employs an interferometer to create an interference pattern containing information across all wavelengths. A mathematical operation (Fourier Transform) is then applied to this interferogram to convert the raw signal into a familiar absorbance or transmittance spectrum [28].

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: For solids, common techniques include the KBr pellet method (mixing ~1 mg of sample with 100-200 mg of KBr and pressing into a pellet) or Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR), which requires minimal preparation—often just placing the sample in contact with the ATR crystal. Liquids can be analyzed between two salt plates.

- Data Acquisition: The prepared sample is placed in the instrument's beam path. A background spectrum (without the sample) is first collected. The sample spectrum is then collected, typically over a wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹, by averaging 16-64 scans to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Data Analysis: The resulting spectrum is interpreted by identifying the position (wavenumber), shape, and intensity of absorption peaks, which correspond to specific functional groups (e.g., a broad peak at 3200–3600 cm⁻¹ indicates an O-H stretch, while a sharp peak near 1700 cm⁻¹ suggests a C=O stretch) [28].

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF)

Principle and Workflow: XRF is an atomic-level technique. When a material is exposed to high-energy X-rays, inner-shell electrons are ejected from atoms. As outer-shell electrons fall to fill these vacancies, they emit characteristic fluorescent X-rays. The energy of these emitted X-rays identifies the element, while their intensity relates to its concentration [37] [33]. Instruments can be energy-dispersive (ED-XRF), which uses a detector to separate and count X-rays of different energies simultaneously, or wavelength-dispersive (WD-XRF), which uses a crystal to diffract specific wavelengths to a detector.

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: For solids like metals or glasses, minimal preparation (e.g., surface cleaning) is needed. Powders (e.g., soils, crushed minerals) are often homogenized and pressed into pellets to ensure a flat, representative surface. Liquids can be analyzed in specialized cups.

- Data Acquisition: The sample is placed in the instrument, and the X-ray tube is activated. Measurement conditions (voltage, current) are optimized for the elements of interest. A spectrum is acquired, typically within seconds to a few minutes [38].

- Quantification: For qualitative analysis, peaks are assigned to elements based on their known energies [33]. For quantitative results, the Fundamental Parameters (FP) method, which uses theoretical models to correct for matrix effects, is commonly used. For highest accuracy, calibration with matrix-matched standards is recommended [33].

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

Principle and Workflow: ICP-MS is a powerful technique for trace elemental and isotopic analysis. The sample is typically introduced in liquid form (after acid digestion) and converted into an aerosol. This aerosol is transported into a high-temperature argon plasma (~10,000 K), where it is vaporized, atomized, and ionized. The resulting ions are then extracted into a high-vacuum mass spectrometer, separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), and counted by a detector [34] [35]. This process allows for extremely sensitive detection of most elements in the periodic table.

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Digestion: Solid samples (e.g., battery materials, biological tissues) must be dissolved. This often involves digesting 0.1–0.5 g of sample with strong acids (e.g., HNO₃, HCl, HF) using a hotplate, microwave, or automated digestion system.

- Instrument Tuning and Calibration: The ICP-MS is tuned using a multi-element standard to optimize sensitivity and minimize interferences. A calibration curve is established using a series of standard solutions with known concentrations [39] [35].

- Analysis and Data Processing: The digested and diluted sample is introduced via a peristaltic pump and nebulizer. Internal standards (e.g., Indium, Rhodium) are often added online to correct for instrument drift and matrix suppression. Concentrations are calculated by the software based on the calibration curve [39].

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

Principle and Workflow: LIBS uses a highly energetic, focused laser pulse to abate a tiny amount of material from the sample surface, creating a microplasma. The atoms and ions within this plasma are excited into higher energy states. As they decay back to their ground states, they emit light at characteristic wavelengths. The collected light is dispersed by a spectrometer, and the resulting spectrum is analyzed to determine the sample's elemental composition [36].

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Presentation: Requires minimal preparation. Solid samples can be analyzed directly on their native surface. To improve reproducibility, surfaces can be cleaned, and powders can be pressed into pellets.

- Data Acquisition: The sample is positioned so that the laser is focused on its surface. Multiple laser pulses are fired at each analysis location, and the emitted light is collected by a lens or fiber optic and sent to the spectrometer. A single measurement takes microseconds.

- Data Analysis: The spectrum is processed to identify elemental peaks. Quantification can be achieved by building multivariate calibration models using reference materials with known composition. LIBS is renowned for its high-speed mapping and suitability for hazardous material detection at a distance (standoff analysis) [36].

Raman Spectroscopy

Principle and Workflow: Raman spectroscopy probes molecular vibrations by measuring the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, usually from a laser. Most scattered light is at the same energy as the laser source (Rayleigh scattering), but a tiny fraction undergoes a shift in energy corresponding to the vibrational modes of the molecules in the sample. This inelastically scattered light (the Raman effect) produces a spectrum that is a fingerprint of the material's molecular structure, crystallinity, and phase [32].

Typical Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Raman is largely non-destructive and requires minimal sample prep. Solids, liquids, and gases can be analyzed directly. Care must be taken to avoid sample heating or degradation by the laser, and fluorescence can sometimes interfere.

- Data Acquisition: The laser is focused onto the sample, and the scattered light is collected. A filter blocks the intense Rayleigh scatter, and the remaining Raman signal is dispersed by a grating onto a sensitive detector (e.g., a CCD camera). Acquisition times range from seconds to minutes.

- Data Analysis: The resulting spectrum is interpreted by examining the positions, widths, and relative intensities of the Raman peaks. Reference spectra from databases (experimental or computational, as in high-throughput first-principles calculations [32]) are often used for material identification.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational workflows for the five spectroscopic techniques, highlighting the transformation of sample into analyzable data.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of spectroscopic analysis requires the use of specific consumables, standards, and sample preparation materials. The following table lists key items essential for the experiments described in this guide.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for spectroscopic analysis

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Application |