From Benchtop to Bioprocess: The Evolution of Spectroscopic Techniques Shaping Modern Drug Development

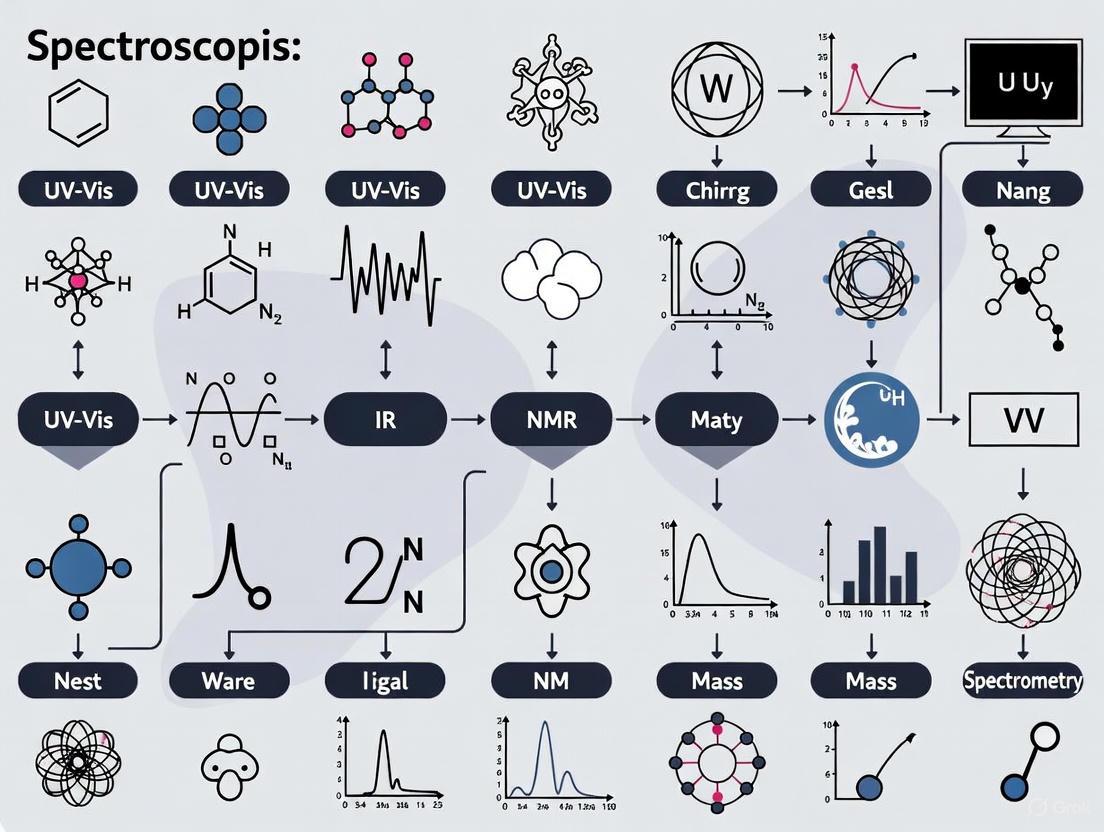

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the historical evolution and modern applications of spectroscopic techniques, with a specialized focus on the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industry.

From Benchtop to Bioprocess: The Evolution of Spectroscopic Techniques Shaping Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the historical evolution and modern applications of spectroscopic techniques, with a specialized focus on the pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industry. It traces the foundational discoveries from early UV-Vis and IR spectroscopy to the nano-driven transformation of Raman and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). The content explores current methodological applications in drug discovery, quality control, and real-time Process Analytical Technology (PAT), while addressing troubleshooting challenges like model optimization and data complexity. A comparative evaluation of techniques validates their roles in quantitative analysis, process monitoring, and the characterization of complex biologics, offering scientists and drug development professionals a strategic guide for leveraging spectroscopy in the development of next-generation therapeutics.

The Foundational Pillars: Tracing the Historical Breakthroughs in Analytical Spectroscopy

The period from the early 20th century through the 1950s marked a revolutionary era in analytical science, during which the foundational techniques of ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis), infrared (IR), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy were developed and established. Driven by the confluence of quantum mechanical theory and pressing analytical needs—from vitamin research to war efforts—these methodologies transformed the ability of scientists to probe molecular identity and structure. This guide details the historical context, fundamental principles, and standardized experimental protocols that cemented UV-Vis, IR, and NMR as indispensable tools for molecular characterization, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals.

Historical Foundations and Key Milestones

The development of modern molecular spectroscopy was a gradual process, evolving from initial qualitative observations to precise, quantitative analytical techniques. Isaac Newton's work in the 17th century, where he first applied the word "spectrum" to describe the rainbow of colors from dispersed sunlight, is a foundational point [1]. The 19th century saw critical advancements, including Joseph von Fraunhofer's detailed observations of dark lines in the solar spectrum using improved spectrometers and diffraction gratings, which elevated spectroscopy to a more precise science [1].

The pivotal shift from atomic to molecular spectroscopy began in the early 20th century. In IR spectroscopy, William Weber Coblentz, in the early 1900s, demonstrated that chemical functional groups exhibited specific and characteristic IR absorptions, laying the empirical groundwork for the technique [2]. For UV-Vis spectroscopy, practical impetus came from nutritional science in the 1930s, when research indicated that vitamins like vitamin A absorbed ultraviolet light. This spurred the development of commercial instruments, culminating in the 1941 launch of the Beckman DU spectrophotometer, which drastically reduced analysis time from hours or days to minutes [3] [4].

NMR spectroscopy has its theoretical roots in the early quantum mechanical work of physicists like Niels Bohr [5]. The direct discovery of NMR is credited to Isidor Isaac Rabi, who, in the 1930s, observed nuclear magnetic resonance in molecular beams, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 [6] [5]. This was swiftly followed by the pioneering work of Edward Mills Purcell and Felix Bloch, who independently developed NMR spectroscopy for liquids and solids in the late 1940s, sharing the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1952 [6] [5].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Establishing UV-Vis, IR, and NMR Spectroscopy

| Date | Event | Key Scientist/Entity | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1666 | Discovery of the Solar Spectrum | Isaac Newton [1] | First systematic study of light dispersion, coined the term "spectrum". |

| Early 1900s | Correlation of IR Bands with Functional Groups | William Weber Coblentz [2] | Established IR spectroscopy as a tool for molecular structure identification. |

| 1939-1941 | First Commercial UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Arnold O. Beckman/Beckman Instruments [3] [4] | Enabled rapid, accurate quantitative analysis of light-absorbing molecules like vitamins. |

| 1945-1946 | Development of NMR Spectroscopy for Condensed Matter | Purcell, Bloch, et al. [6] | Made NMR a practical technique for studying liquids and solids, forming the basis of modern NMR. |

| Mid 1940s | First Commercial IR Spectrometers | Beckman, PerkinElmer [2] | Made IR analysis accessible for R&D, particularly in the petrochemical and organic chemistry fields. |

| 1957 | First Low-Cost IR Spectrophotometer | PerkinElmer (Model 137) [2] | Democratized access to IR spectroscopy for a broader range of laboratories. |

Fundamental Principles and Technical Data

Each spectroscopic technique probes a different type of molecular transition, defined by the energy of the electromagnetic radiation it uses.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy involves the excitation of valence electrons between molecular orbitals, such as from the Highest Occupied Molecular Orbital (HOMO) to the Lowest Unoccupied Molecular Orbital (LUMO) [7]. These electronic transitions occur in the ultraviolet and visible regions of the electromagnetic spectrum. The fundamental law governing quantitative analysis in absorption spectroscopy is the Beer-Lambert Law (or Beer's Law): ( A = \epsilon c l ), where ( A ) is the measured absorbance, ( \epsilon ) is the molar absorptivity, ( c ) is the concentration, and ( l ) is the path length [7].

IR Spectroscopy probes molecular vibrations, such as stretching and bending of covalent bonds [7]. The mid-IR spectrum, which is most commonly used for molecular characterization, ranges from 4000 to 200 cmâ»Â¹ (wavenumber) or 2.5 to 50 µm in wavelength [2]. IR absorption is sensitive to heteronuclear bonds and asymmetric vibrations, providing a "fingerprint" unique to a specific compound [2].

NMR Spectroscopy is based on the re-orientation of atomic nuclei with non-zero spin in a strong external magnetic field upon absorption of radiofrequency radiation [6]. The resonant frequency of a nucleus is highly sensitive to its local chemical environment, providing detailed information on molecular structure, dynamics, and the chemical identity of functional groups [6]. The most common nuclei studied are ¹H and ¹³C [6].

Table 2: Fundamental Characteristics of UV-Vis, IR, and NMR Spectroscopy

| Parameter | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | IR Spectroscopy | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Transition | Electronic (valence electrons) [7] | Vibrational (bond vibrations) [7] | Nuclear Spin (nuclei in magnetic field) [6] |

| Typical Energy Range | Ultraviolet & Visible Light | Infrared Radiation [2] | Radio Waves [6] |

| Common Wavelength | ~190 - 800 nm | 2.5 - 50 µm [2] | - |

| Common Wavenumber | - | 4000 - 200 cmâ»Â¹ [2] | - |

| Common Frequency | - | - | 4 - 900 MHz [6] |

| Key Quantitative Law | Beer-Lambert Law [7] | Beer-Lambert Law | - |

| Primary Information | Concentration, chromophore presence | Functional group identity, molecular fingerprint [2] | Molecular structure, functional group connectivity, dynamics [6] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The establishment of these techniques relied on the development of standardized experimental protocols and instrumentation.

UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy Protocol

The fundamental setup for a UV-Vis spectrometer, as exemplified by the Beckman DU, includes a broadband light source, a dispersion element (such as a quartz prism), a wavelength selector, a sample holder, a detector, and a recorder [7] [4].

Diagram 1: UV-Vis Spectrometer Workflow

- Instrument Calibration: Ensure the instrument is warmed up and calibrated according to manufacturer specifications. Wavelength accuracy can be verified using known standards.

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the analyte in a suitable solvent that does not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest. Common solvents include water, ethanol, and hexane.

- Baseline Correction: Collect a spectrum with the solvent alone in the light path to establish a baseline.

- Data Acquisition: Place the sample solution in a cuvette of known path length (typically 1 cm) in the sample beam. Scan through the UV and visible wavelength range, measuring the intensity of light transmitted through the sample (I) and the reference (Iâ‚€).

- Data Analysis: Calculate absorbance (A) at each wavelength as ( A = \log{10}(I0/I) ). For quantitative analysis, use the absorbance value at λₘâ‚â‚“ and the Beer-Lambert Law to determine concentration: ( c = A / (\epsilon l) ), where ε is the known molar absorptivity coefficient [7].

Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol

Early dispersive IR spectrometers used a double-beam configuration to perform real-time background correction. Light from a source was split, passing through the sample and a reference, and was then dispersed by a diffraction grating onto a thermocouple detector [8].

Diagram 2: Dispersive IR Spectrometer Workflow

- Sample Preparation (Traditional Methods):

- Mull Technique: Grind 1-2 mg of solid sample with a drop of inert mulling agent (e.g., Nujol) in an agate mortar to form a fine paste. Compress the paste between two potassium bromide (KBr) or sodium chloride (NaCl) plates to form a thin film.

- KBr Pellet: Thoroughly mix 1 mg of sample with approximately 100 mg of dry potassium bromide powder. Press the mixture under high pressure in a specialized die to form a transparent pellet.

- Background Collection: Collect a background spectrum with an empty beam or a pure mulling agent/pure KBr pellet.

- Data Acquisition: Place the prepared sample in the spectrometer beam path. Scan through the standard mid-IR range (e.g., 4000-600 cmâ»Â¹). In a double-beam instrument, this automatically generates a ratioed spectrum against the reference beam [2].

- Spectral Interpretation: Identify key absorption bands and correlate their wavenumbers to known functional group vibrations (e.g., C=O stretch ~1700 cmâ»Â¹, O-H stretch ~3300 cmâ»Â¹) to deduce molecular structure [2].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Protocol

The basic NMR experiment involves aligning nuclear spins in a strong, constant magnetic field (Bâ‚€), perturbing this alignment with a radio-frequency (RF) pulse, and detecting the RF signal emitted as the nuclei relax back to equilibrium [6].

Diagram 3: Basic Pulsed NMR Spectroscopy Workflow

- Magnetic Field Stabilization: The spectrometer's magnetic field is homogenized using "shims" to parts per billion. A "lock" system, typically on the deuterium signal of the solvent, continuously monitors and corrects for magnetic field drift [6].

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve 2-50 mg of the sample in 0.5-0.7 mL of a deuterated solvent (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) [6]. Use a coaxial insert tube containing a reference compound (e.g., tetramethylsilane, TMS) if not already present in the solvent.

- Tuning and Calibration: Insert the sample tube into the magnet and allow it to equilibrate (spin). Tune the probe to the nucleus of interest (e.g., ¹H) and calibrate the 90° pulse width [6].

- Data Acquisition: Transmit a short, powerful RF pulse at the Larmor frequency of the nucleus to excite all nuclei simultaneously. The receiver then detects the decaying RF signal, known as the Free Induction Decay (FID). This process is repeated many times (from 16 for ¹H to hundreds for ¹³C) to improve the signal-to-noise ratio through averaging [6].

- Data Processing: Apply a Fourier Transform to the raw time-domain FID data to convert it into a frequency-domain spectrum. Phase and baseline correct the spectrum for analysis [6].

- Spectral Interpretation: Analyze the spectrum by determining chemical shifts (δ in ppm) relative to TMS, integration (for proton counting), and spin-spin coupling patterns (multiplicity and J-coupling constants) to infer the molecular structure and environment of nuclei [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful application of these spectroscopic techniques relies on a set of critical reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Early Spectroscopy

| Item | Technique | Function and Description |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | UV-Vis | Container for liquid samples; quartz is essential for UV transmission, while glass can be used for visible light only. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) | NMR | Solvent that provides a deuterium signal for the field-frequency lock system and minimizes interfering solvent proton signals [6]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR | An IR-transparent salt used to form pellets for solid sample analysis by pressing powdered sample with KBr [2]. |

| Mulling Agents (e.g., Nujol) | IR | An inert, viscous hydrocarbon used to suspend a finely ground solid sample between salt plates for analysis [2]. |

| Internal Standard (Tetramethylsilane - TMS) | NMR | Added to the sample in a deuterated solvent to provide a universal reference point (0 ppm) for chemical shift measurements [6]. |

| Salt Plates (NaCl, KBr) | IR | Windows made of materials transparent to IR radiation, used to hold liquid samples or mulls in the spectrometer beam path. |

| Monochromator (Prism/Grating) | UV-Vis, IR | The core optical component that disperses broadband light into its constituent wavelengths for selective analysis [4] [8]. |

| Mal-VC-PAB-DM1 | Mal-VC-PAB-DM1, MF:C61H82ClN9O17, MW:1248.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fencamine-d3 | Fencamine-d3 Stable Isotope | Fencamine-d3 is a deuterated stable isotope-labeled analog for research. It is for Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

The Raman effect, originating from the inelastic scattering of light, was first predicted by Smekal in 1923 and experimentally observed by C.V. Raman and Krishnan in 1928 [9]. This phenomenon provides a direct means to probe vibrational and rotational-vibration states in molecules and materials, offering unique chemical fingerprint information [9]. Despite its significant advantages over infrared spectroscopy—particularly when studying aqueous systems due to water's weak Raman scattering compared to strong infrared absorption—the practical application of spontaneous Raman scattering has long been hampered by its inherently weak signal, with scattering cross-sections approximately 10-14 times smaller than fluorescence processes [9] [10].

The fundamental weakness of the Raman effect confined the technique to limited practical use for nearly five decades until a serendipitous discovery at the University of Southampton in 1974 revolutionized the field. Martin Fleischmann, Patrick J. Hendra, and A. James McQuillan observed unexpectedly intense Raman signals from pyridine molecules adsorbed on electrochemically roughened silver electrodes [11] [10]. Initially attributed merely to increased surface area for molecular adsorption, this phenomenon was later recognized by Jeanmaire and Van Duyne (1977) and independently by Albrecht and Creighton (1977) as a genuine enhancement of the Raman scattering efficiency itself, ultimately achieving amplification factors of 10^5 to 10^6 [11] [10]. This discovery marked the birth of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), launching a new era in vibrational spectroscopy that would overcome the traditional sensitivity limitations of conventional Raman scattering.

Fundamental Principles and Enhancement Mechanisms

Electromagnetic Enhancement Mechanism

The primary mechanism responsible for the dramatic signal enhancement in SERS is electromagnetic in nature, accounting for enhancement factors typically ranging from 10^4 to 10^10 [12] [11]. This enhancement originates from the excitation of localized surface plasmons (LSPs)—coherent oscillations of conduction electrons—when nanostructured noble metal surfaces (typically gold or silver) are illuminated with light at appropriate wavelengths [13] [14].

The electromagnetic enhancement process operates through a two-step mechanism. First, the incident laser field is significantly enhanced at the metal surface due to plasmon resonance. Second, the Raman scattering efficiency of molecules located within this enhanced field is similarly amplified [11]. Since the total enhancement scales with the fourth power of the local electric field (E^4), nanoscale regions with the highest field confinement—known as "hot spots"—produce the most dramatic signal enhancements [13] [11]. These hot spots typically occur in nanoscale gaps between metallic nanoparticles, at sharp tips, or in regions of high surface curvature where electromagnetic fields are most effectively concentrated [12].

The electromagnetic enhancement mechanism depends critically on the optical properties of the nanostructured metal substrate. Silver and gold remain the most widely used metals for visible light SERS due to their plasmon resonance frequencies falling within this spectral range, though copper has also demonstrated effectiveness [11]. Recently, aluminum has emerged as a promising alternative for UV-SERS applications due to its plasmon band in the ultraviolet region [11].

Chemical Enhancement Mechanism

Complementing the electromagnetic effect, a secondary chemical enhancement mechanism contributes additional signal amplification, typically by 10-100 times [12]. This mechanism involves charge transfer between the metal substrate and adsorbed molecules, effectively creating a resonance Raman-like condition where the Raman scattering cross-section is increased [11].

The chemical enhancement mechanism requires direct contact or close proximity between the molecule and metal surface, as it depends on the formation of surface complexes or chemical bonds [11]. This effect is particularly significant for molecules whose molecular orbitals overlap with the Fermi level of the metal, enabling charge-transfer transitions that resonate with the incident laser excitation [11]. While the chemical enhancement is substantially smaller than the electromagnetic contribution, it provides valuable molecular-specific information about surface interactions and adsorption geometries.

Table 1: Comparison of SERS Enhancement Mechanisms

| Feature | Electromagnetic Mechanism | Chemical Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Enhancement Factor | 10^4-10^10 | 10-10^2 |

| Range | Long-range (~30 nm) | Short-range (direct contact) |

| Substrate Dependence | Metal morphology and composition | Chemical affinity and molecular orientation |

| Molecular Specificity | Low | High |

| Theoretical Basis | Plasmon resonance, field enhancement | Charge transfer, resonance Raman |

Methodological Evolution and Technical Implementation

Historical Development of SERS

The evolution of SERS over its half-century history can be divided into four distinct developmental phases, as revealed by a comprehensive historical analysis [15]. The initial development period (mid-1970s to mid-1980s) was characterized by fundamental discoveries and the establishment of theoretical frameworks explaining the enhancement phenomenon. This was followed by a downturn period (mid-1980s to mid-1990s) where challenges in reproducibility and substrate fabrication limited widespread adoption [15].

The field experienced a dramatic resurgence during the nano-driven transformation period (mid-1990s to mid-2010s), where advances in nanoscience and nanotechnology enabled precise fabrication of nanostructures with optimized plasmonic properties [15]. This period saw the development of well-controlled nanoparticles with various shapes (nanospheres, nanorods, nanostars, nanocubes) and the introduction of transition metals as viable SERS substrates [12] [10]. Since the mid-2010s, SERS has entered a boom period characterized by sophisticated applications in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and cultural heritage analysis, alongside the development of advanced techniques including tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) and shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHINERS) [15] [12].

SERS Substrate Fabrication and Optimization

The performance of SERS critically depends on the properties of the substrate, with key parameters including composition, morphology, and architecture [12] [11]. Early substrates relied on electrochemically roughened electrodes or aggregated colloidal nanoparticles, which provided substantial enhancement but suffered from poor reproducibility [10]. Modern substrate design has evolved toward engineered nanostructures with precise control over size, shape, and arrangement.

Table 2: Evolution of SERS Substrate Technologies

| Generation | Substrate Types | Enhancement Factor | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First (1970s-1980s) | Electrochemically roughened electrodes, colloidal aggregates | 10^5-10^6 | Simple preparation, high enhancement | Poor reproducibility, inhomogeneous |

| Second (1990s-2000s) | Lithographically patterned surfaces, controlled nanoparticles | 10^6-10^8 | Improved uniformity, tunable plasmonics | Complex fabrication, higher cost |

| Third (2010s-present) | Hybrid structures, 2D materials, 3D ordered nanostructures | 10^7-10^11 | High reproducibility, multifunctionality | Specialized synthesis required |

Advanced substrate architectures now include:

- Plasmonic nanoparticles with precisely controlled shapes (nanostars, nanorods, nanocubes) that create intense electromagnetic fields at sharp features [12]

- Three-dimensional ordered substrates that provide homogeneous signal enhancement and avoid the heterogeneous hot-spots associated with colloidal aggregation [12]

- Hybrid structures combining plasmonic metals with semiconductors or 2D materials (graphene, MoS2) that leverage both electromagnetic and chemical enhancement mechanisms [12] [11]

- Magnetic-plasmonic composites that enable sample concentration and separation through application of external magnetic fields [12]

The development of reliable, reproducible substrate fabrication methods has been essential for transforming SERS from a laboratory curiosity to a robust analytical technique suitable for quantitative analysis [12] [11].

Experimental Protocols for SERS Measurement

Protocol 1: Colloidal SERS for Molecular Detection

- Substrate Preparation: Synthesize gold or silver nanoparticles (typically 30-60 nm) using citrate reduction or similar methods. Characterize nanoparticle size and uniformity using UV-Vis spectroscopy (plasmon band position and width) and electron microscopy [12] [11].

- Sample Preparation: Mix analyte solution with colloidal suspension at optimal ratio (typically 1:1 to 1:10 v/v). Add aggregation agent (e.g., NaCl, MgSO4) if necessary to induce controlled nanoparticle clustering for hot-spot formation [12].

- Measurement Parameters: Select laser excitation wavelength matched to plasmon resonance of the substrate (typically 532 nm for silver, 633 nm for gold). Use appropriate laser power (0.1-10 mW) to avoid sample degradation. Employ acquisition times of 1-100 seconds depending on analyte concentration [12] [16].

- Data Collection: Record multiple spectra from different sample spots to account for heterogeneity. Include reference samples (substrate without analyte) for background subtraction [12].

Protocol 2: Solid SERS Substrate for Bioanalysis

- Substrate Selection: Choose commercially available or custom-fabricated solid SERS substrates (e.g., silicon or glass slides with deposited metal nanostructures, nanopatterned surfaces, or commercial SERS tapes) [12] [11].

- Sample Immobilization: Apply liquid sample (1-10 µL) to substrate surface and allow to dry. For complex biological matrices, implement washing steps to remove unbound interferents. Alternatively, functionalize substrate with capture elements (antibodies, aptamers) for specific target binding [12].

- Instrumentation: Utilize confocal Raman microscope with high-numerical aperture objective (60×-100×) for spatial resolution approaching the diffraction limit. Ensure precise focus on substrate surface for maximum signal [12] [13].

- Mapping and Analysis: Employ automated stage to collect spectral maps across sample area. Use multivariate analysis techniques (principal component analysis, hierarchical clustering) to extract meaningful chemical information from hyperspectral datasets [12].

Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: Breaking the Diffraction Limit

Principles and Instrumentation of TERS

Tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) represents a groundbreaking advancement that combines the chemical sensitivity of SERS with the superior spatial resolution of scanning probe microscopy (SPM) [13] [14]. First proposed by Wessel in 1985 and experimentally realized in 2000, TERS enables chemical imaging with nanoscale resolution, overcoming the fundamental diffraction limit that constrains conventional optical microscopy [13] [14].

The core principle of TERS relies on the enormous electromagnetic field enhancement generated at the apex of a sharp, metal-coated scanning probe microscope tip when illuminated by an appropriate laser source [13] [17]. This enhancement arises from a combination of the lightning rod effect (charge accumulation at sharp tips) and localized surface plasmon resonance when the tip material and geometry are properly matched to the excitation laser wavelength [13] [14]. The resulting confined electromagnetic field acts as a nanoscale light source, providing Raman signal enhancement exclusively from molecules located directly beneath the tip apex.

TERS instrumentation integrates scanning probe microscopy (either atomic force microscopy (AFM) or scanning tunneling microscopy (STM)) with confocal Raman spectroscopy through three primary optical geometries:

- Bottom illumination (transmission mode) through a transparent substrate with high-numerical aperture objectives

- Side illumination with a long working-distance objective for non-transparent samples

- Top illumination with the laser focused directly onto the tip from above [13]

The Raman enhancement factor (EF) in TERS experiments is quantitatively calculated using the formula: [ EF = \left( \frac{I{Tip-in}}{I{Tip-out}} - 1 \right) \frac{A{FF}}{A{NF}} ] where (I{Tip-in}) and (I{Tip-out}) represent Raman intensities with the tip engaged and retracted, respectively, while (A{FF}) and (A{NF}) correspond to the far-field and near-field probe areas [13].

TERS Probe Fabrication and Optimization

The performance of TERS critically depends on the properties of the scanning probe, with key parameters including tip material, radius of curvature, and plasmon resonance characteristics [13] [17]. The most common fabrication methods include:

Thermal Evaporation Coating: Dielectric AFM tips (silicon, silicon nitride) are metal-coated (typically gold or silver) through thermal evaporation in high vacuum (10^-5–10^-6 mbar). Pre-deposition of a thin adhesion layer (SiO2, AlF3) improves coating stability and enhances plasmonic performance [13].

Electrochemical Etching: Pure metal tips (gold, silver) are fabricated through electrochemical etching in appropriate electrolytes. This method produces tips with excellent plasmonic properties and tip radii smaller than 10 nm, but requires optimization of etching parameters for consistent results [13].

Template-Stripped Tips: Recently developed template-based fabrication methods produce highly reproducible gold tips with consistent enhancement factors and improved durability compared to conventional coated tips [13].

Table 3: TERS Probe Fabrication Methods and Performance Characteristics

| Fabrication Method | Tip Materials | Typical Radius | Enhancement Factor | Yield | Durability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Evaporation | Ag/Au on Si/SiN | 20-50 nm | 10^3-10^6 | Low | Moderate |

| Electrochemical Etching | Au, Ag wire | <10 nm | 10^4-10^7 | Moderate | High |

| Template-Stripped | Au | 20-40 nm | 10^5-10^7 | High | High |

Experimental Protocols for TERS Measurement

Protocol 1: AFM-TERS for Nanomaterials Characterization

- Tip Preparation: Select appropriate cantilever (contact, tapping, or contact mode) based on sample properties. Deposit 30-50 nm silver or gold coating via thermal evaporation with 2-5 nm chromium or titanium adhesion layer. Verify tip enhancement using reference sample (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene) [13] [17].

- Sample Preparation: Deposit sample on appropriate substrate (glass, mica, silicon). For atomically thin materials (graphene, TMDs), ensure flat, clean surfaces. For biological samples, use surface immobilization strategies to minimize drift [13] [14].

- Instrument Alignment: Engage tip on sample surface. Align laser focus to tip apex using confocal microscopy. Optimize polarization parallel to tip axis for maximum enhancement. Verify tip enhancement by comparing spectra with tip engaged versus retracted [13].

- Spectral Mapping: Acquire point spectra or hyperspectral maps with step sizes (10-50 nm) smaller than tip radius. Maintain constant tip-sample distance through feedback mechanism. Typical parameters: 0.1-1 mW laser power, 1-10 s integration per spectrum [13] [17].

- Data Processing: Subtract background spectra. Apply cosmic ray removal. Generate chemical maps based on specific Raman band intensities or positions [13].

Protocol 2: STM-TERS for Single-Molecule Studies

- Tip Preparation: Electrochemically etch gold or silver wire to produce sharp tips. Anneal under ultrahigh vacuum if possible to remove contaminants [13].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare atomically flat single-crystal surfaces (Au(111), Ag(111)). Deposit target molecules through sublimation or solution deposition at controlled coverage [13].

- Measurement Conditions: Operate under ultrahigh vacuum or controlled atmosphere to minimize contamination. Set appropriate tunneling parameters (0.1-1 nA current, 0.1-1 V bias). Use radially polarized laser excitation for strongest field enhancement [13].

- Simultaneous Topography/Spectroscopy: Acquire STM topography and TERS spectra simultaneously. Monitor signal fluctuations that may indicate single-molecule detection [13] [17].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Biomedical and Diagnostic Applications

SERS and TERS have found particularly impactful applications in biomedical research and clinical diagnostics, where their exceptional sensitivity and molecular specificity provide significant advantages [12]. Key applications include:

Cancer Diagnostics: SERS-based immunoassays enable early detection of low-abundance protein biomarkers for cancers such as pancreatic and ovarian cancer. Multiplexed detection platforms in microfluidic chips facilitate simultaneous measurement of multiple biomarkers, improving diagnostic accuracy and enabling differentiation between diseases with similar biomarker profiles [12] [11].

Pathogen Detection: Direct SERS strategies allow rapid identification and differentiation of bacterial pathogens (e.g., Salmonella enterica, Escherichia coli) and viruses (e.g., Enterovirus 71) based on their unique spectral fingerprints. Modifying SERS substrates with specific affinity proteins (e.g., SCARB2) enables highly selective viral detection [12].

Single-Cell Analysis: TERS provides unprecedented capability to investigate biochemical heterogeneity within individual cells, mapping distributions of lipids, proteins, nucleic acids, and pharmaceuticals at subcellular resolution. This enables studies of cell membrane organization, drug uptake mechanisms, and cellular responses to therapeutic interventions at the nanoscale [13].

Materials Science and Nanotechnology

In materials science, SERS and TERS have emerged as powerful tools for characterizing structure-property relationships at the nanoscale:

Two-Dimensional Materials: TERS has revealed defect-specific Raman features in graphene, transition metal dichalcogenides (MoS2, WS2), and other 2D materials, enabling correlation between atomic-scale structure and electronic properties. Edge defects, grain boundaries, and strain distributions can be mapped with nanoscale resolution, guiding materials design for electronic and optoelectronic applications [17] [14].

Catalysis and Surface Science: SERS provides molecular-level insight into catalytic mechanisms by monitoring reaction intermediates and surface processes under operational conditions. TERS extends this capability to single catalytic sites, revealing heterogeneity in activity and selectivity that is obscured in ensemble measurements [13].

Polymer and Composite Characterization: TERS enables nanoscale mapping of phase segregation, crystallinity, and chemical composition in polymer blends and composites, providing crucial information for materials optimization and failure analysis [13].

Cultural Heritage and Environmental Analysis

The non-destructive nature of Raman techniques has enabled innovative applications in cultural heritage science, where SERS and TERS facilitate analysis of priceless artifacts without sampling or damage [18]. These techniques enable identification of pigments, binding media, and degradation products in paintings, manuscripts, and archaeological objects, informing conservation strategies and authentication efforts [18].

In environmental monitoring, SERS provides sensitive detection of pollutants, including heavy metals, pesticides, and organic contaminants, in complex matrices. Field-portable SERS instruments enable on-site analysis of water quality and aerosol composition with detection limits approaching those of laboratory-based techniques [16].

Food Safety and Quality Control

SERS has emerged as a powerful technique for ensuring food safety and quality, with applications ranging from detection of chemical contaminants to authentication of food products [16]. Key implementations include:

Detection of Adulterants and Contaminants: SERS enables rapid identification of melamine in dairy products, unauthorized dyes in spices, pesticide residues on fruits and vegetables, and veterinary drug residues in meat products. Integration with molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) enhances selectivity in complex food matrices [16].

Pathogen Screening: SERS-based microfluidic platforms provide rapid detection of foodborne pathogens (e.g., Salmonella, Listeria, E. coli) with potential for point-of-care diagnosis in food production facilities. These systems combine sample concentration, separation, and detection in integrated platforms, reducing analysis time from days to hours [16].

Quality Authentication: SERS enables verification of food authenticity and origin through spectroscopic fingerprinting, detecting adulteration of high-value products such as olive oil, honey, and spices. Portable SERS instruments facilitate supply chain monitoring and prevention of food fraud [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for SERS and TERS Experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Materials | Gold nanoparticles (30-60 nm), Silver nanoparticles (40-100 nm), Aluminum nanostructures | Provide plasmonic enhancement | Gold: biocompatible, stable; Silver: higher enhancement but oxidizes; Aluminum: UV applications |

| Tip Fabrication | Silicon AFM probes, Gold wire (0.25 mm), Silver wire (0.25 mm), Hydrochloric acid (etchant) | TERS probe preparation | Electrochemical etching produces sharp metallic tips; Thermal evaporation coats dielectric probes |

| Surface Functionalization | Alkanethiols, Silane coupling agents, Biotin-streptavidin systems, Antibodies, Aptamers | Molecular-specific binding | Enable targeted detection; Improve substrate stability and selectivity |

| Reference Materials | Pyridine, 4-Mercaptobenzoic acid (4-MBA), Crystal violet, Rhodamine 6G | Enhancement factor calculation | Provide standardized signals for quantification and method validation |

| Sample Preparation | Sodium citrate (reducing agent), Magnesium sulfate (aggregation agent), Phosphate buffered saline | Colloidal stability and aggregation control | Optimize nanoparticle aggregation for maximum hot-spot formation |

| Instrument Consumables | Quartz cuvettes, Microscope slides, Silicon wafers, Mica sheets | Sample support and measurement | Low background fluorescence and Raman signals essential |

| Ethylideneamino benzoate | Ethylideneamino Benzoate|Research Chemicals | Bench Chemicals | |

| Cyclo(Ile-Leu) | Cyclo(Ile-Leu), MF:C12H22N2O2, MW:226.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The Raman revolution, spanning from the fundamental discovery of the effect to the advanced enhancements of SERS and TERS, represents a remarkable journey of scientific innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration. What began as a curious observation of enhanced signals from a roughened electrode has evolved into a sophisticated analytical toolkit that continues to expand the boundaries of chemical analysis.

The development of SERS overcame the fundamental sensitivity limitations that constrained conventional Raman spectroscopy for decades, while TERS shattered the diffraction barrier that had limited spatial resolution in optical microscopy. Together, these techniques provide unparalleled capability for molecular identification and characterization at the nanoscale, enabling applications ranging from single-molecule detection to clinical diagnostics and materials design.

As these techniques continue to evolve, emerging directions include the integration of machine learning for spectral analysis, development of multifunctional hybrid substrates, miniaturization for point-of-care diagnostics, and exploration of novel plasmonic materials beyond traditional noble metals. The next chapter of the Raman revolution will likely focus on increasing accessibility through standardized protocols and commercial instrumentation, ultimately transforming these powerful techniques from specialized research tools into mainstream analytical methods that address critical challenges across science, medicine, and industry.

Bibliometric analysis serves as an indispensable statistical tool for mapping the state of the art in scientific fields, providing essential information for prospecting research opportunities and substantiating scientific investigations [19]. In the field of spectroscopy—the study of the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation—this analytical approach reveals profound insights into the historical progression and intellectual structure of the discipline [20]. The method encompasses instruments to identify and analyze scientific performance based on citation metrics, reveal field trends through keyword analysis, and identify research clusters from recent publications [19]. This article employs bibliometric methodology to trace the systematic evolution of spectroscopic research, delineating its progression through four distinct developmental phases that reflect the field's response to technological innovation and emerging scientific paradigms.

The foundational principles of spectroscopy originated in the 17th century with Isaac Newton's prism experiments, where he first applied the word "spectrum" to describe the rainbow of colors forming white light [1]. These early investigations into the nature of light and color gradually evolved into a precise scientific technique through the contributions of figures like Joseph von Fraunhofer, who conducted detailed studies of solar spectral lines in the early 1800s [1]. The subsequent formalization of spectroscopy as an analytical discipline emerged through the work of Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff in the 1860s, who established that spectral lines are unique to each element and developed spectroscopy into a method for trace chemical analysis [21] [1]. This historical foundation sets the stage for the bibliometric mapping of spectroscopy's modern evolution, which this analysis divides into four distinct phases based on publication trends, citation networks, and methodological innovations.

Phase I: Foundation and Proof-of-Concept (Pre-1960 to 1970s)

Historical Development and Theoretical Frameworks

The initial phase of spectroscopic research encompasses the foundational work that established the core principles and early applications of the technique. This period begins with pre-20th century discoveries and extends through the proof-of-concept stage for various spectroscopic methods. The creation of the first spectroscope by Newton, featuring an aperture to define a light beam, a lens, a prism, and a screen, provided the essential instrumentation blueprint for subsequent developments [21]. The 19th century witnessed critical theoretical and experimental advances, including Pierre Bouguer's 1729 observation that light passing through a liquid decreases with increasing sample thickness, Johann Heinrich Lambert's formulation of his "Law of Absorption" in 1760, and August Beer's later establishment of the relationship between light absorption and concentration that now bears their name as the Beer-Lambert law [21].

The mid-19th century marked the emergence of spectroscopy as a precise analytical tool, characterized by key milestones such as David Rittenhouse's production of the first primitive diffraction grating in 1786, William Hyde Wollaston's 1802 observation of dark lines in the solar spectrum, and Joseph von Fraunhofer's invention of the transmission diffraction grating and detailed study of solar spectral lines in 1814 [21] [1]. The pivotal collaboration between Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff in the 1850s-1860s demonstrated that spectral lines are unique to each element, establishing spectroscopy as a method for elemental analysis and leading to the discovery of new elements including cesium, rubidium, thallium, and indium [21]. This period also saw Anders Jonas Ångström's publication of solar spectral line wavelengths in units of 10–10 meters (now known as the angstrom), cementing the quantitative foundation of spectroscopic measurement [21].

Key Methodological Innovations and Experimental Approaches

The proof-of-concept phase witnessed the development of several instrumental breakthroughs that transformed spectroscopic practice. Henry A. Rowland's 1882 production of greatly improved curved diffraction gratings using his new ruling machine at Johns Hopkins University established new standards for spectral resolution and precision [21]. The early 20th century brought the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen in 1895, Pieter Zeeman's observation of magnetic splitting of spectral lines in 1896, and the development of quantum theory by Max Planck and others, providing a theoretical framework for interpreting atomic and molecular spectra [21].

The period between 1900-1950 saw the introduction of commercially available spectroscopic instruments, with Frank Twyman (Adam Hilger Ltd.) producing the first commercially available quartz prism spectrograph in 1900 [21]. This era also witnessed foundational work in time-resolved spectroscopy, with A. Schuster and G. Hemsalech reporting the first work on time-resolved optical emission spectroscopy in 1900 using moving photographic film, and C. Ramsauer and F. Wolf investigating time-resolved spectroscopy of alkali and alkaline earth metals using a slotted rotating disk in 1921 [21]. The integration of spectroscopic theory with quantum mechanics culminated in Niels Bohr's 1913 quantum mechanical model of the atom, which explained the observed wavelengths of spectral lines through electron transitions between energy states [21].

Table 1: Key Proof-of-Concept Developments in Electrochemical Optical Spectroscopy

| Year | Technique | System Studied | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1963 | EC-ellipsometry | Anodic formation of Hgâ‚‚Clâ‚‚ films on Hg electrodes | First in situ electrochemical optical spectroscopy [22] |

| 1964 | EC-UV-Vis | Electro-redox of ferrocyanide | First in situ study of electrochemical product in solution phase [22] |

| 1966 | EC-IR | Electroreductions of 8-quinolinol | First in situ spectroelectrochemistry using vibrational spectroscopy [22] |

| 1967 | EC-SHG | Electrified Si and Ag electrodes | First in situ nonlinear spectroscopy at electrochemical interface [22] |

| 1973 | EC-Raman | Electrochemical deposition of Hgâ‚‚Clâ‚‚, Hgâ‚‚Brâ‚‚, and HgO | First normal Raman measurement in electrochemical systems [22] |

Phase II: Enhancement and Specialization (1980s-1990s)

Plasmonic Enhancement and Sensitivity Breakthroughs

The second phase of spectroscopic evolution witnessed a paradigm shift from fundamental method development to the creation of enhanced techniques with dramatically improved sensitivity and specialization. This period was characterized by the emergence of plasmonic enhancement-based electrochemical vibrational spectroscopic methods that addressed the critical limitation of detecting molecules at sub-monolayer coverage [22]. The groundbreaking discovery of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) between 1974-1977, which enabled the high-quality Raman spectroscopic measurement of (sub)monolayers of molecules adsorbed on electrochemically roughened Ag electrode surfaces, represented a revolutionary advancement in detection capability [22]. This plasmonic enhancement principle was subsequently extended to infrared spectroscopy with the development of surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (SEIRAS) in the mid-1990s, which exploited the enormously strong IR absorption exhibited by molecules on evaporated thin metal films [22].

A significant methodological innovation during this period was the strategy of "borrowing" SERS activity from highly active substrates to probe signals on normally weak or non-SERS-active surfaces. Beginning in 1987, researchers successfully obtained EC-SERS signals from various transition metal layers (including Fe, Ni, Co, Pt, Pd, and Pb) deposited on Au or Ag substrates, dramatically expanding the range of materials accessible to Raman spectroscopic investigation [22]. Further refinement came in 1995 with the development of EC-SERS using self-assembled monodisperse colloids, where monodisperse high-SERS-active nanoparticles were regularly arranged on organosilane-polymer-modified solid substrates, yielding desirable SERS activity with improved stability and reproducibility [22]. These enhancement strategies fundamentally transformed the applicability of vibrational spectroscopy to interfacial studies.

Methodological Diversification and Instrumentation Advances

This phase witnessed substantial diversification in spectroscopic methodologies and significant instrumental advancements that expanded application domains. The period saw the introduction of innovative data analysis methods including multivariate curve resolution (MCR), which decomposes complex datasets into contributions from underlying components to enhance data clarity and identify specific spectral features corresponding to individual chemical species [23]. Time-resolved spectroscopy emerged as a powerful approach for probing the dynamics of physical and chemical processes by capturing spectral data at extremely short time intervals, enabling researchers to monitor transitions and transformations in real time [23]. Mathematically, time-resolved spectra could be represented as a function of both time and frequency, S(ω,t), facilitating multi-dimensional analysis of dynamic processes [23].

Instrumentation advances during this period included the development of high-resolution detectors that allowed researchers to capture subtle spectral features once undetectable, enabling observation of minute variations in spectral lines critical for high-precision measurements [23]. The introduction of portable and miniaturized systems, particularly handheld spectrometers equipped with micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), democratized spectral analysis by enabling in situ measurements in remote or challenging environments [23]. The period also saw the emergence of specialized spectral analysis software suites, including MATLAB, LabVIEW, and Python-based platforms like SciPy and Astropy, which integrated advanced algorithms for processing spectral data alongside visualization, statistical analysis, and machine learning components [23].

Diagram 1: The Four-Phase Evolution of Spectroscopic Research with Associated Techniques and Applications

Phase III: Atomic Resolution and Well-Defined Surfaces (1990s-2010)

Single-Crystal Electrodes and Defined Interface Studies

The third evolutionary phase marked a critical transition from enhanced but structurally heterogeneous surfaces to well-defined interfaces with atomic-level precision. This period witnessed the realization of electrochemical vibrational spectroscopy on well-defined surfaces, enabling unprecedented correlation between spectral features and specific surface structures [22]. The late 1980s saw the pioneering application of electrochemical infrared spectroscopy to single-crystal electrodes, with studies of CO and hydrogen adsorption at Pt single-crystal electrodes providing detailed insights into surface-binding configurations and structure-function relationships [22]. This approach was extended to Raman spectroscopy in 1991 through the investigation of pNDMA adsorption at Ag single-crystal electrodes, followed by similar studies of pyridine at Cu single-crystal electrodes in 1998 [22]. These investigations demonstrated that surface plasmon polaritons induced by attenuated total reflection (ATR) configurations could effectively enhance Raman signals on atomically flat electrode surfaces, overcoming the inherent sensitivity limitations of conventional Raman spectroscopy at well-defined interfaces [22].

The pursuit of defined surface studies culminated in several groundbreaking methodological innovations. Electrochemical shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (EC-SHINERS), introduced in 2010, represented a particularly significant advance by utilizing ultra-thin, pinhole-free dielectric shells on nanoparticles to provide enormous Raman enhancement while preventing direct interaction between the metal core and the electrode surface [22]. This approach enabled detailed spectroscopic investigation of processes such as hydrogen adsorption at Pt single-crystal electrodes with unprecedented clarity and specificity [22]. Similarly, the development of electrochemical tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (EC-TERS) in 2015 combined electrochemistry, plasmon-enhanced spectroscopy, and scanning probe microscopy with high spatial resolution, allowing researchers to probe potential-dependent processes such as the protonation and deprotonation of molecules on Au single-crystal electrodes and electrochemical redox processes on transparent conducting oxides [22].

Advanced Spectroscopic Modalities and Resolution Breakthroughs

This phase witnessed the emergence and refinement of sophisticated spectroscopic modalities that pushed the boundaries of spatial and spectral resolution. Nonlinear optical techniques such as electrochemical sum frequency generation (EC-SFG) provided unique capabilities for probing well-defined interfaces, with initial demonstrations on single-crystal electrodes in 1994 investigating hydrogen and cyanide adsorption at Pt surfaces [22]. These methods offered exceptional surface specificity by exploiting the non-centrosymmetric nature of interfaces, enabling selective observation of molecular species specifically located at electrode surfaces without interference from the bulk solution phase [22]. The combination of these advanced optical techniques with well-defined electrode geometries facilitated detailed mechanistic understanding of interfacial electrochemical processes with molecular-level precision.

Further extending the capabilities of surface analysis, electrochemical Fourier transform infrared nano-spectroscopy (EC-nano FTIR) emerged in 2019 as a powerful tool for investigating potential-dependent phenomena at nanoscale interfaces [22]. This technique demonstrated particular utility for probing aggregation processes and molecular reorganization at electrode-electrolyte interfaces, such as potential-dependent aggregations of sulfate and ammonium at the graphene-electrolyte interface [22]. The continuous refinement of these methodologies throughout Phase III established a comprehensive toolkit for interrogating electrochemical interfaces with increasingly sophisticated spatial and temporal resolution, setting the stage for the subsequent development of operando approaches that would bridge fundamental studies with practical application environments.

Table 2: Progression of Detection Sensitivity and Resolution Across Developmental Phases

| Phase | Detection Limit | Spatial Resolution | Key Enabling Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Foundation | Monolayer to multilayer films | Macroscopic to millimeter scale | Prisms, diffraction gratings, photographic detection [21] [22] |

| Phase II: Enhancement | Sub-monolayer (10¹²-10¹ⵠmolecules) | Micrometer to sub-micrometer scale | SERS, SEIRAS, portable spectrometers [23] [22] |

| Phase III: Atomic Resolution | Single molecule (SERS) | Nanometer to atomic scale | SHINERS, TERS, nano-FTIR [22] |

| Phase IV: Operando Analysis | Sub-monolayer under working conditions | Multiple scales (nm-μm) integrated with device architecture | Machine learning, multivariate analysis, microspectroscopy [23] [22] |

Phase IV: Operando Spectroscopy and Cross-Disciplinary Integration (2010-Present)

Operando Methodologies and Real-Time Monitoring

The current phase of spectroscopic evolution is characterized by the emergence and rapid adoption of operando spectroscopic approaches, which investigate chemical and structural changes under actual working conditions in real-time [22]. This paradigm shift advances the subject of investigation from idealized electrochemical interfaces to practical interphases between electrodes and electrolytes, capturing the complexity of functional systems [22]. The early 2010s witnessed the initial implementation of operando electrochemical infrared and Raman spectroscopy, with applications ranging from investigation of adsorbed CO on catalyst surfaces to monitoring of complex processes in energy storage systems [22]. This methodological transition has been particularly transformative for studying functional energy materials, where operando spectroscopic monitoring provides direct insight into charge-transfer mechanisms, degradation processes, and state-of-health parameters under realistic operating conditions [22].

The implementation of operando methodologies has been facilitated by several technological advances, including the development of specialized spectroelectrochemical cells that maintain electrochemical control while providing optimal optical access for spectroscopic measurements [22]. Fiber-optic based systems have enabled operando monitoring in challenging environments such as batteries, where conventional optical alignment is impossible [22]. Simultaneously, the integration of multiple spectroscopic techniques within single experimental frameworks has provided complementary information that offers more comprehensive understanding of complex systems. These multimodal approaches often combine Raman and infrared spectroscopy with X-ray techniques or mass spectrometry to correlate molecular vibrational information with elemental composition or structural evolution, creating rich datasets that capture multiple aspects of system behavior under operational conditions [22].

Data Science Integration and Computational Spectroscopy

A defining characteristic of the current spectroscopic paradigm is the deeply integrated role of computational methods and data science approaches in both experimental design and data interpretation. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning has transformed the analysis of spectral data, enabling automated pattern recognition, classification, and prediction capabilities that dramatically enhance extraction of meaningful information from complex datasets [23]. Machine learning algorithms, including support vector machines (SVMs), random forests, and deep neural networks, now drive predictive models capable of classifying spectral signatures with high accuracy, while statistical models help determine feature importance and correlations, leading to robust methodologies for spectral interpretation [23]. Deep learning approaches such as convolutional neural networks have demonstrated particular promise in identifying subtle anomalies and patterns in spectral images, with autoencoders and generative adversarial networks (GANs) being employed for tasks such as image reconstruction and noise reduction in hyperspectral imaging [23].

Advanced data analysis frameworks have emerged as essential components of modern spectroscopic practice. Multivariate curve resolution (MCR) techniques decompose complex datasets into contributions from underlying components, enhancing data clarity and helping identify specific spectral features corresponding to individual chemical species [23]. Compressed sensing frameworks, which leverage sparsity in data to enable reconstruction from significantly fewer samples than traditionally required, have found significant applications in spectral imaging and real-time monitoring [23]. Mathematically, these approaches often employ observation models expressed as y = Ax + ε, where y is the observed vector, A is a sensing matrix, x is the sparse representation of the original signal, and ε represents noise, with specialized algorithms enabling rapid data acquisition and efficient processing under time and resource constraints [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials in Modern Spectroscopic Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Shell-Isolated Nanoparticles (SHINs) | Plasmonic enhancement with chemical isolation | EC-SHINERS for single-crystal electrode studies [22] |

| Monodisperse Metal Colloids | Reproducible SERS substrates | Self-assembled nanoparticle films for quantitative analysis [22] |

| Single-Crystal Electrodes | Atomically defined surface structures | Correlation of spectral features with surface structure [22] |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds | Spectral discrimination of specific moieties | Tracing reaction pathways and mechanistic studies [24] |

| Electrolyte Solutions with Redox Probes | Mediating electron transfer in spectroelectrochemistry | Studying electron transfer mechanisms and kinetics [22] |

| Functionalized Tip Probes | Nanoscale spatial resolution in TERS | Mapping chemical heterogeneity with <10 nm resolution [22] |

| Boranethiol | Boranethiol, CAS:53844-93-2, MF:BHS, MW:43.89 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dodec-8-en-1-ol | (Z)-Dodec-8-en-1-ol|For Research | (Z)-Dodec-8-en-1-ol is a key pheromone for insect pest management research. This product is for research use only (RUO) and is not intended for personal use. |

The bibliometric analysis of spectroscopic research reveals a clear evolutionary trajectory through four distinct phases, each characterized by specific methodological advances and conceptual frameworks. This progression began with foundational proof-of-concept studies, advanced through enhancement and specialization phases, achieved atomic-level resolution on well-defined surfaces, and has now emerged into an era of operando analysis and cross-disciplinary integration [22]. Current spectroscopic research continues to push boundaries through developments in portable and miniaturized systems, high-resolution detectors, and the integration of AI and machine learning for automated data analysis [23]. These innovations are reshaping the landscape of modern research across diverse fields including astrophysics, materials science, chemistry, and biomedical applications [23].

Future developments in spectroscopy are likely to focus on addressing several persistent challenges, including managing the enormous data volumes generated by modern instruments, overcoming noise and signal interference limitations, and reducing instrumentation costs to enhance accessibility [23]. Research in parallel processing, quantum computing, adaptive filtering, and noise-cancellation techniques shows promise in addressing these limitations [23]. Additionally, the ongoing development of cost-effective yet reliable alternatives through innovations in materials science and micro-fabrication technologies may democratize access to advanced spectroscopic capabilities [23]. As these technical advances proceed, spectroscopy will continue to expand its applications in environmental monitoring, medical diagnostics, astronomical investigations, and industrial process control, solidifying its role as an indispensable tool for scientific discovery and technological innovation across the disciplinary spectrum [23].

Diagram 2: Integrated Workflow for Modern Operando Spectroelectrochemical Studies Combining Multiple Techniques and Data Streams

The Rise of Non-Destructive and Portable Techniques for In-Situ Analysis

The field of chemical analysis is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional, destructive laboratory-based techniques toward non-destructive, portable methods that provide immediate results at the point of need. This evolution is driven by advances in spectroscopic technologies and the growing demand for rapid, on-site decision-making in fields ranging from environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical development and forensic science. Traditional methods like gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), while highly sensitive and accurate, are often centralized, time-consuming, destructive of samples, and require extensive sample preparation and highly trained personnel [25] [26]. In contrast, modern portable spectroscopic techniques provide non-destructive, rapid analysis with minimal to no sample preparation, enabling in-situ characterization where the sample is located [27]. This whitepaper explores the core principles, key technologies, and practical applications driving the rise of non-destructive and portable analysis, with a particular focus on spectroscopy-based methods.

Core Principles and Key Technologies

Non-destructive analytical techniques are defined by their ability to interrogate a sample without altering its chemical composition or physical integrity. This allows for the preservation of evidence for future reference or for the same sample to be subjected to subsequent analyses [27]. The portability of these techniques is enabled by technological miniaturization, including the development of compact lasers, advanced detectors, and robust optical systems, without significant sacrifice of analytical performance [28] [27].

Several spectroscopic techniques stand at the forefront of this analytical revolution. The table below summarizes the core principles and advantages of the key technologies discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Core Principles of Key Non-Destructive and Portable Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Typical Sample Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portable NIR Spectroscopy [27] | Measures overtones and combination vibrations of molecular bonds (e.g., C-H, O-H, N-H). | Non-destructive, rapid, deep sample penetration, easy-to-use. | Solids, liquids, gases. |

| Raman Spectroscopy [28] [29] | Measures inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, providing a molecular "fingerprint". | High spectral specificity, minimal interference from water, reagent-free. | Solids, liquids, gases. |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) [25] [26] | Dramatically enhances Raman signal by adsorbing analytes onto nanostructured metal surfaces. | Extreme sensitivity (single-molecule level), capable of trace analysis. | Liquids, complex mixtures (e.g., biofluids). |

| Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy (QEPAS) [30] | Detects sound waves generated when gas absorbs modulated light, using a quartz tuning fork as a sensor. | High sensitivity for trace gases, immunity to environmental noise, compact size. | Gases. |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Quartz-Enhanced Photoacoustic Spectroscopy (QEPAS) for Trace Gas Sensing

QEPAS is a highly sensitive technique for detecting trace gases. The core principle involves the photoacoustic effect: a modulated laser beam, tuned to an absorption peak of the target gas, is focused between the prongs of a quartz tuning fork (QTF). The gas absorbs the light, undergoes non-radiative relaxation, and generates a periodic pressure wave (sound) through thermal expansion. The high-quality factor (Q-factor) of the QTF mechanically resonates at the modulation frequency, amplifying the signal, which is then converted into an electrical signal via the piezoelectric effect [30].

Experimental Protocol for QEPAS:

- Laser Source Selection: A tunable laser source (e.g., distributed feedback laser) is selected with its emission wavelength matching the absorption line of the target gas [30].

- Wavelength Modulation: The laser's wavelength or intensity is modulated at the precise resonant frequency of the QTF (typically in the kHz range) [30].

- Gas Excitation: The modulated laser beam is focused through the sample gas between the QTF prongs [30].

- Acoustic Wave Detection: The generated acoustic wave drives the QTF's vibration, producing a piezoelectric current [30].

- Signal Processing: This weak current is amplified and processed by a lock-in amplifier, which is referenced to the laser modulation frequency, to extract the signal amplitude [30].

- Quantification: The signal amplitude, which is proportional to the gas concentration, is recorded. System calibration with known concentration standards is required for quantitative analysis [30].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and signal transduction pathway of the QEPAS technique.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) for Illicit Drug Detection

SERS overcomes the inherent low sensitivity of conventional Raman spectroscopy by utilizing plasmonic metal nanostructures to enormously enhance the Raman signal of molecules adsorbed on their surface. The protocol below details a specific approach using magnetic-plasmonic composite substrates for analyzing drugs in complex mixtures [25].

Experimental Protocol for SERS using Fe3O4@AgNPs:

- Substrate Synthesis:

- Fe3O4 Core: Magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles are synthesized via a solvothermal method using FeCl₂ and FeCl₃ as precursors and sodium hydroxide as a reducing agent [25].

- Amination: The Fe3O4 nanoparticles are functionalized with (3-aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane to create an amine-rich surface [25].

- Silver Coating: Silver nanoparticles are grown in-situ on the aminated surface by reducing silver nitrate with trisodium citrate, forming the core-shell Fe3O4@AgNPs composite [25].

- Sample Preparation and Enrichment:

- The Fe3O4@AgNPs substrate is mixed with the liquid sample (e.g., suspension of a complex mixture) [25].

- The mixture is vortexed to allow target analyte molecules (e.g., drugs like etomidate, heroin, ketamine) to adsorb onto the silver shell [25].

- An external magnet is applied to separate the particle-analyte complex from the solution matrix, thereby enriching the target and removing interfering substances [25].

- SERS Measurement:

- The magnetically enriched pellet is placed on a slide or well for analysis.

- A portable Raman spectrometer with a 785 nm laser is typically used. The laser is focused on the sample, and the scattered light is collected to generate the SERS spectrum [25].

- Data Analysis:

- Collected spectra are pre-processed (e.g., baseline correction, smoothing).

- The Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection algorithm is applied to the high-dimensional spectral data. UMAP reduces the dimensionality while preserving topological data structure, effectively clustering spectra by their chemical identity and simplifying the identification of target drugs amidst complex backgrounds [25].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Fe3O4@AgNPs SERS Substrate

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| FeCl₂·4H₂O / FeCl₃·6H₂O | Iron precursors for the synthesis of the magnetic Fe3O4 core nanoparticles [25]. |

| Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) | Acts as a reducing agent in the solvothermal synthesis of the Fe3O4 core [25]. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)trimethoxysilane (APTMS) | Silane coupling agent used to functionalize the Fe3O4 surface with amine groups for binding silver [25]. |

| Silver Nitrate (AgNO₃) | Source of silver ions for the growth of the plasmonically active AgNPs shell [25]. |

| Trisodium Citrate Dihydrate | Reducing and stabilizing agent for the in-situ growth of silver nanoparticles on the Fe3O4 core [25]. |

| Fe3O4@AgNPs Composite | Integrated SERS substrate providing both magnetic enrichment (via Fe3O4 core) and signal enhancement (via AgNPs shell) [25]. |

The integrated workflow for this SERS-based detection method, from sample preparation to intelligent data analysis, is summarized below.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

The selection of an appropriate technique depends heavily on the analytical problem, including the sample type, required sensitivity, and operational environment. The following table provides a structured comparison to guide this decision-making process.

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Portable and Non-Destructive Techniques

| Technique | Best For | Typical Sensitivity | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portable NIR Spectroscopy [27] | In-situ quality control (e.g., food, pharmaceuticals), raw material identification, soil analysis. | Varies by application; suited for major component analysis. | Complex spectra require chemometrics for interpretation; generally less sensitive than MIR. |

| Portable Raman Spectroscopy [28] [29] | On-site identification of unknown solids and liquids, forensic analysis, polymorph characterization. | Varies; can detect components at ~1-5% concentration in mixtures. | Fluorescence interference from colored samples; inherently weak signal without enhancement. |

| SERS [25] [26] | Trace-level detection in complex matrices (e.g., drugs in saliva, pollutants in water), single-molecule studies. | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to single-molecule level. | Substrate reproducibility and cost; requires optimization of substrate-analyte interaction. |

| QEPAS [30] | Ultrasensitive, specific trace gas monitoring (e.g., environmental NO/CHâ‚„, medical diagnostics). | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) level. | Primarily for gases; optical alignment can be challenging. |

The rise of non-destructive and portable techniques for in-situ analysis marks a significant milestone in the evolution of analytical science. Technologies like portable NIR, Raman, SERS, and QEPAS are transforming workflows across industries by delivering immediate, actionable data directly at the source—be it a crime scene, a manufacturing line, or a remote environmental monitoring station. The integration of these advanced sensors with sophisticated data processing tools like UMAP and machine learning is further enhancing their power and accessibility, pushing the boundaries of what is possible outside the traditional laboratory [25] [27]. As miniaturization and material science continue to advance, these techniques will become even more sensitive, affordable, and integrated into the fabric of real-time decision-making, solidifying their role as indispensable tools for researchers and professionals dedicated to understanding and manipulating the molecular world.

The evolution of spectroscopic instrumentation from custom-built apparatuses to standardized commercial platforms represents a critical, yet often overlooked, dimension in the history of scientific technology. This transition has fundamentally shaped how researchers conduct experiments, enabling the shift from individual craftsmanship toward reproducible, accessible, and increasingly sophisticated analytical methods. For centuries, natural philosophers and scientists designed and built their own instruments, a process that required deep theoretical knowledge alongside skilled craftsmanship [31] [32]. These custom-built setups were often unique, non-reproducible, and limited to a handful of experts capable of both operating and maintaining them.

The move to commercial platforms democratized spectroscopic analysis, making powerful techniques available to a broader community of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. This shift was not merely a change in manufacturing but a transformation in research ecology, enabling standardization, comparative studies, and the integration of spectroscopy into routine analytical workflows across chemistry, materials science, and pharmaceutical development [33] [34]. This document traces this instrumental journey, highlighting key technological milestones and their impact on modern research practices.

Historical Progression of Key Instrumentation

The development of spectroscopic instruments follows a clear arc from fundamental demonstrations of principle to engineered, commercially available products. The following timeline and table summarize pivotal moments in this journey.

Timeline of Instrument Development from Custom Builds to Commercial Platforms

Key Instrumentation Milestones from the 17th to Mid-20th Century

| Year | Scientist/Manufacturer | Instrument/Milestone | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1666 | Isaac Newton | Custom prism setup [31] [32] | First documented experimental setup to systematically disperse light into its spectrum; a custom prototype. |

| 1802 | William Hyde Wollaston | Improved slit apparatus [32] | Introduced a slit instead of a round aperture, enhancing spectral resolution. |

| 1814 | Joseph von Fraunhofer | First proper spectroscope (custom) [32] | Incorporated a slit, a convex lens, and a viewing telescope; used to systematically study dark lines in the solar spectrum. |

| 1859 | Gustav Kirchhoff & Robert Bunsen | Custom flame spectroscopy setup [32] | Established that spectral lines are unique to each element, founding the science of spectral analysis. |

| 1937 | Maurice Hasler (ARL) | First commercial grating spectrograph [32] | Marked the beginning of commercially produced spectroscopic instruments for laboratory use. |

| 1938 | Hilger and Watts, Ltd. | First commercial X-ray spectrometer [32] | Early example of a specialized commercial spectrometer. |

| 1955 | Alan Walsh | Commercial Atomic Absorption Spectrometer [32] | Launched a technique that would become a workhorse in analytical laboratories. |

The Modern Commercial Landscape

The latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century have been characterized by the refinement and diversification of commercial spectroscopic platforms. Key trends include miniaturization, hyphenation of techniques, and intelligent software integration, driven by the demands of fields like pharmaceutical development and materials science [33] [34] [35].

Contemporary Commercial Instrumentation Trends (2020-2023)

Recent product introductions highlight the current direction of commercial spectroscopic platforms, showcasing a focus on application-specific solutions, portability, and data integration.

| Trend Category | Example Instrument/Company | Description | Implication for Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miniaturization & Handheld Devices | Various handheld Raman/XRF analyzers [33] [34] | Compact, battery-powered instruments for field analysis. | Enables real-time, on-site decision making in drug manufacturing and mineral exploration [35]. |

| Technique Combination | Shimadzu AIRsight (FT-IR + Raman) [34] | A single microscope combining two vibrational spectroscopy techniques. | Provides complementary data from the exact sample spot, streamlining materials characterization. |

| Automation & Software | Metrohm Vision Air 2.0 [34] | Software for automated method control and data analysis. | Reduces operator dependency and integrates spectroscopy into broader lab informatics ecosystems. |

| Advanced Detection | Bruker Hyperion II IR Microscope [34] | Microscope combining quantum cascade lasers with FT-IR. | Enhances sensitivity and spatial resolution for analyzing complex mixtures and thin films. |

Experimental Protocols: From Classic to Contemporary

Protocol 1: Classical Custom-Build Absorption Experiment (c. 1666)

This protocol is based on Isaac Newton's seminal experiment, which laid the groundwork for optical spectroscopy [31] [32].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Prism | Core optical element for dispersing white light into its constituent spectral colors. |

| Darkened Chamber | Controlled environment to isolate the experiment from ambient light. |

| Window Shutter with Aperture | Creates a controlled, narrow beam of incoming sunlight. |

| White Screen/Wall | Surface for projecting and observing the resulting spectrum. |

Methodology:

- Setup: In a completely darkened chamber, allow a single beam of sunlight to enter through a small, round aperture in the window shutter.