From Spectra to Solutions: A Comprehensive Guide to Interpreting Spectroscopic Data in Biomedical Research

This article provides a modern framework for interpreting spectroscopic data, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

From Spectra to Solutions: A Comprehensive Guide to Interpreting Spectroscopic Data in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a modern framework for interpreting spectroscopic data, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It bridges foundational principles with cutting-edge applications, covering the core concepts of atomic and molecular spectroscopy, the practical use of techniques like SRS, FLIM, and NIR in biological contexts, and the critical application of chemometrics and AI for robust data analysis. Readers will gain actionable insights into troubleshooting spectral data, validating models, and leveraging these tools for advancements in biomarker discovery, therapeutic monitoring, and diagnostic innovation.

Core Principles: How Light Interacts with Matter in Biomedical Analysis

Spectroscopy, the study of the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation, serves as a fundamental exploratory tool across scientific disciplines. This field bifurcates into two principal categories: atomic spectroscopy and molecular spectroscopy. Each category probes matter at different structural levels and provides distinct, complementary information essential for comprehensive material characterization. Within spectral interpretation research, understanding the core differences, capabilities, and limitations of these techniques is paramount for selecting the appropriate analytical tool for a given research question.

Atomic spectroscopy investigates the electronic transitions of atoms, typically in their gaseous or elemental state. It is concerned with the energy changes occurring within individual atoms when electrons are promoted to higher energy levels or relax back to lower ones. The measured wavelengths are unique to each element, making atomic spectroscopy an powerful technique for elemental identification and quantification, without regard to the chemical form of the element [1]. In contrast, molecular spectroscopy examines the interactions of molecules with electromagnetic radiation, probing the energy changes associated with molecular rotations, vibrations, and the electronic transitions of the molecule as a whole. These interactions reveal information about chemical bonds, functional groups, and molecular structure [2] [3].

The overarching thesis of modern spectroscopic data interpretation is that robust, reliable analysis requires not just advanced instrumentation, but also a deep understanding of the underlying physical principles and the judicious application of chemometric techniques to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data [4] [5]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two spectroscopic pillars, offering researchers a framework for their selective application in drug development and related fields.

Core Principles and Instrumentation

Atomic Spectroscopy: Probing Elemental Composition

Atomic spectroscopy is fundamentally based on the quantization of electronic energy levels within atoms. When an electron in an atom transitions between discrete energy levels, it absorbs or emits a photon of characteristic energy, corresponding to a specific wavelength. The core principle is that the spectrum of these wavelengths is unique for each element, serving as a "fingerprint" for its identification [6]. The relationship between energy and wavelength is governed by the Bohr equation, ( E1 - E2 = h\nu ), where ( h ) is Planck's constant and ( \nu ) is the frequency of the light [6].

The instrumentation for atomic spectroscopy typically requires an atomization source to break chemical bonds and convert the sample into free atoms in the gas phase. Common techniques include:

- Flame Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (F-AAS): Uses a flame to atomize the sample and is sufficiently sensitive for many applications.

- Graphite Furnace Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (GF-AAS): Provides greater sensitivity for trace element analysis.

- Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES): Uses a high-temperature plasma to excite atoms, allowing for simultaneous multi-element detection [7].

These techniques have the highest elemental detection sensitivity, often at parts-per-billion levels, but they inherently lack spatial resolution and provide no information on molecular structure or chemical environment [7].

Molecular Spectroscopy: Elucidating Molecular Structure

Molecular spectroscopy, on the other hand, investigates the interactions of molecules with electromagnetic radiation. The energy states in a molecule are more complex than in an atom, encompassing electronic energy, vibrational energy, and rotational energy. Transitions between these states give rise to spectra that reveal rich chemical information [3]. The techniques are differentiated by the type of radiative energy and the nature of the interaction, which can be absorption, emission, or scattering [3].

Key molecular spectroscopy techniques include:

- Infrared (IR) and Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy: Probe vibrational and rotational modes of molecules, providing information about functional groups and chemical bonds [2].

- Raman Spectroscopy: Based on the inelastic scattering of light, it also provides vibrational information and is particularly useful for samples in aqueous solutions [2] [4].

- Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy: Investigates electronic transitions in molecules, often involving conjugated systems [8].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Utilizes the magnetic properties of certain nuclei to deduce molecular structure and dynamics [3].

Unlike atomic spectroscopy, molecular spectroscopy examines the chemical bonds present in compounds, eliciting telltale signals from the bonds between atoms rather than exciting individual atoms [1].

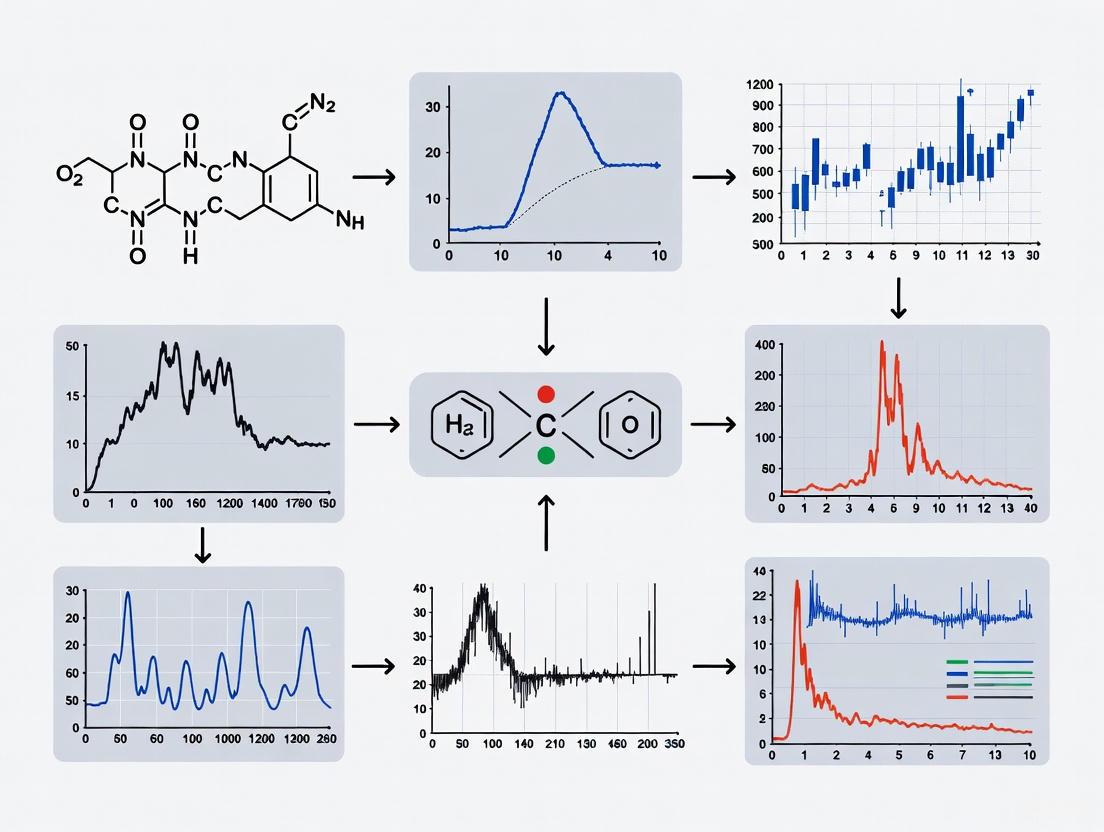

Visualizing the Core Differences

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in the energy transitions probed by atomic versus molecular spectroscopy.

The selection between atomic and molecular spectroscopy is dictated by the specific analytical question. The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison of their core characteristics to guide this decision.

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Atomic and Molecular Spectroscopy Techniques

| Parameter | Atomic Spectroscopy | Molecular Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | Elements (e.g., K, Fe, Pb) [1] | Functional groups, chemical bonds, molecular structures (e.g., -OH, C=O) [1] |

| Information Obtained | Total elemental composition & concentration [7] | Molecular identity, structure, polymorphism, interactions |

| Typical Detection Limits | ppt to ppb range (e.g., GF-AAS, ICP-MS) [7] | ppm to % range (e.g., NIR, Raman) [2] |

| Sample Form | Often requires digestion/liquid solution [7] | Solids, liquids, gases; often minimal preparation |

| Key Quantitative Figures of Merit | Determination coefficient (R²) up to 0.999, high precision in concentration [9] | R² > 0.99 for robust models, reliant on chemometrics [9] [5] |

| Primary Applications | Trace metal analysis, environmental monitoring, quality control of elemental impurities [7] | Pharmaceutical polymorph screening, reaction monitoring, food quality, material identification [2] [5] |

Advanced Applications and Synergistic Approaches

Multi-Source Spectroscopy Synergetic Fusion

A cutting-edge advancement in spectral interpretation research is the move away from viewing techniques in isolation and toward their synergistic integration. Multi-source spectroscopy synergetic fusion combines data from atomic and molecular techniques to achieve a more complete analytical picture and improve the robustness of prediction models [9].

A seminal study on the detection of total potassium in culture substrates demonstrated this principle powerfully. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS, atomic) and Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS, molecular) were used individually and in fusion. While the single-spectrum detection models showed poor performance, the LIBS-NIRS synergetic fusion model achieved a determination coefficient (R²) of 0.9910 for the calibration set and 0.9900 for the prediction set, realizing high-precision detection that neither technique could accomplish alone [9]. This approach leverages the elemental specificity of atomic spectroscopy with the molecular context provided by molecular spectroscopy, creating a model that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Computational Chemistry in Spectral Interpretation

The integration of computational chemistry has become a powerful tool for interpreting spectroscopic data, especially in molecular spectroscopy. By using methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT), researchers can simulate the expected spectra of molecules, which aids in the assignment of complex spectral features.

A case study on acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) demonstrated the high consistency between simulated and experimental spectra, with R² values of 0.9933 and 0.9995 for different comparisons [8]. This computational approach not only helps resolve ambiguous peak assignments caused by spectral overlap but also provides a resource-efficient and reproducible framework for pharmaceutical analysis, aligning with green chemistry principles [8].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Detailed Protocol: Elemental Analysis via Atomic Spectroscopy (ICP-AES)

This protocol outlines the determination of trace elements in a pharmaceutical material using Inductively Coupled Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-AES).

1. Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh ~0.2 g of the homogenized solid sample (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient or excipient) into a digestion vessel.

- Add 5 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃, trace metal grade).

- Perform microwave-assisted digestion according to a stepped program (e.g., ramp to 180°C over 10 minutes, hold for 15 minutes).

- After cooling, quantitatively transfer the digestate to a 50 mL volumetric flask and dilute to volume with high-purity deionized water (18 MΩ·cm).

- Include method blanks (acid only) and certified reference materials (CRMs) with each digestion batch for quality control.

2. Instrumental Setup and Calibration:

- Use an ICP-AES spectrometer equipped with a concentric glass nebulizer and a cyclonic spray chamber.

- Set instrument parameters per manufacturer recommendations (typically: RF power 1.2-1.5 kW, nebulizer gas flow 0.6-0.8 L/min, auxiliary gas flow 0.5-1.0 L/min, coolant gas flow 12-15 L/min).

- Prepare a multi-element calibration standard series (e.g., 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 5.0 mg/L) from certified stock solutions in a matrix of 2% HNO₃.

- Select appropriate emission wavelengths for each target element (e.g., K at 766.490 nm, Fe at 238.204 nm, Pb at 220.353 nm), avoiding spectral interferences.

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Aspirate the blank, standards, and samples, measuring the emission intensity at each wavelength.

- The instrument software constructs a calibration curve (intensity vs. concentration) for each element.

- The concentration of elements in the unknown samples is calculated by interpolation from the calibration curve, with correction for the method blank.

- Report results, ensuring recovery rates for the CRM are within acceptable limits (e.g., 85-115%).

Detailed Protocol: Molecular Identification via FT-IR and Raman Spectroscopy

This protocol describes the characterization of a synthetic drug compound, such as acetylsalicylic acid, using complementary FT-IR and Raman techniques.

1. Sample Preparation:

- For FT-IR (KBr Pellet Method): Dry approximately 1 mg of the purified sample and 200 mg of potassium bromide (KBr, IR grade) at 105°C for 1 hour to remove moisture. Mix them thoroughly and grind in a mortar and pestle to a fine powder. Compress the mixture under vacuum in a hydraulic press (~8-10 tons) for 1-2 minutes to form a transparent pellet [8].

- For Raman Spectroscopy: Place a small amount of the solid sample on a glass slide or in a suitable container. Ensure the sample is flat and has a clean surface for analysis. No specific preparation is typically needed beyond ensuring purity.

2. Instrumental Setup and Data Collection:

- FT-IR: Use an FT-IR spectrometer equipped with a DTGS detector. Collect the background spectrum with a clean KBr pellet. Place the sample pellet in the holder and acquire the spectrum over a range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ and 32 scans per spectrum to ensure a good signal-to-noise ratio [8].

- Raman: Use a Raman spectrometer equipped with a 532 nm laser. Set the laser power to a level that does not damage the sample (e.g., 10-50 mW at the sample). Focus the laser on the sample and collect the spectrum over an appropriate range (e.g., 4000-200 cm⁻¹) with an integration time of 10-30 seconds, averaged over multiple accumulations [8].

3. Data Analysis and Interpretation:

- Process the spectra by applying baseline correction and atmospheric suppression (for FT-IR).

- Identify characteristic vibrational bands and assign them to functional groups by comparison to spectral libraries or computational simulations. For acetylsalicylic acid, key FT-IR bands include: C=O stretch of carboxylic acid at ~1750 cm⁻¹ and C=O stretch of ester at ~1690 cm⁻¹. Key Raman bands include: aromatic ring vibrations at ~1600 cm⁻¹ and the phenyl ring stretch at ~1000 cm⁻¹.

- The combined use of FT-IR and Raman provides complementary data, as some bands strong in IR may be weak in Raman and vice versa, offering a more complete vibrational profile.

The workflow for this combined molecular analysis is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful spectroscopic analysis relies on high-purity materials and specialized reagents. The following table details key items essential for the experiments described in this guide.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl) | Sample digestion for atomic spectroscopy; creates a soluble matrix for elemental analysis. | Trace metal grade; required to minimize background elemental contamination [7]. |

| Certified Multi-Element Standard Solutions | Calibration and quantification in atomic spectroscopy (ICP-AES, AAS). | Certified reference materials (CRMs) with known concentrations in a stable, acidic matrix [7]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for FT-IR sample preparation; forms transparent pellets in the infrared region. | Infrared grade, finely powdered, desiccated to avoid water absorption bands [8]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃, D₂O) | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy; provides a signal for instrument locking and avoids dominant H₂O/CH signals. | 99.8% D atom minimum; supplied in sealed ampoules to prevent atmospheric water absorption. |

| Silicon Wafer / Standard Reference Material | Substrate for Raman analysis and wavelength calibration for Raman spectrometers. | Low fluorescence grade; provides a uniform, non-interfering surface for analysis. |

| Certified Reference Material (CRM) | Quality control; validates the accuracy and precision of the entire analytical method. | Matrix-matched to the sample type (e.g., soil, plant tissue, pharmaceutical powder) [7]. |

The choice between atomic and molecular spectroscopy is not a matter of which technique is superior, but which is the most appropriate for the specific analytical problem. Atomic spectroscopy is the unequivocal tool for determining what elements are present and in what quantity. Molecular spectroscopy is the definitive choice for elucidating molecular identity, structure, and bonding.

For the modern researcher, the most powerful approach lies in recognizing the complementary nature of these techniques. The emerging paradigm of multi-source spectroscopic fusion, supported by advanced chemometrics and computational simulations, represents the future of spectral interpretation research. By strategically combining atomic and molecular data, scientists can achieve a level of analytical insight and predictive robustness that is unattainable by any single method, thereby accelerating discovery and ensuring quality in fields from pharmaceuticals to materials science.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is an advanced analytical technique that combines conventional imaging with spectroscopy to capture and process information from across the electromagnetic spectrum. Unlike traditional imaging methods that record only three broad bands of visible light (red, green, and blue), hyperspectral imaging divides the spectrum into hundreds of narrow, contiguous spectral bands [10]. This capability enables the detailed analysis of materials based on their unique spectral signatures—characteristic patterns of electromagnetic energy absorption, reflection, and emission that serve as distinctive "fingerprints" for different materials [10] [11].

The fundamental data structure in hyperspectral imaging is the hyperspectral data cube, a three-dimensional (3D) dataset containing two spatial dimensions (x, y) and one spectral dimension (λ) [10] [12]. This cube is generated through various scanning techniques, including spatial scanning (e.g., pushbroom scanners), spectral scanning (using tunable filters), and snapshot imaging [10]. In the pharmaceutical sciences, this technology has emerged as a powerful tool for non-destructive quality control, enabling rapid identification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), detection of contaminants, and verification of product authenticity without complex sample preparation [13] [12].

The Architecture of the Hyperspectral Data Cube

Fundamental Structure and Composition

The hyperspectral data cube represents a mathematical construct where each spatial pixel contains extensive spectral information. This structure enables researchers to analyze both the physical distribution and chemical composition of materials within a sample simultaneously. The data cube comprises:

- Spatial Dimensions (x, y): These dimensions represent the physical area of the sample being imaged, with spatial resolution determined by factors such as detector size, focal length, and sensor altitude [11]. Each pixel in this spatial plane corresponds to a specific location on the sample surface.

- Spectral Dimension (λ): This dimension contains the full spectral information for each spatial pixel, typically consisting of hundreds of narrow, contiguous bands [10]. The spectral resolution, defined by the width of each band, determines the ability to distinguish between subtle spectral features.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Hyperspectral Data Cubes

| Characteristic | Description | Typical Values | Pharmaceutical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Smallest detectable feature size | 10 μm - 1 mm | Determines ability to detect API distribution and particle size |

| Spectral Resolution | Width of individual spectral bands | 1-10 nm | Affects discrimination of similar chemical compounds |

| Spectral Range | Wavelength coverage | UV (225-400 nm), VIS (400-700 nm), NIR (700-2500 nm) | Different spectral ranges probe different molecular vibrations and electronic transitions |

| Radiometric Resolution | Number of brightness levels | 8-16 bits | Impacts sensitivity to subtle spectral variations |

Data Acquisition Modalities

Hyperspectral data cubes can be acquired through several distinct scanning methodologies, each with particular advantages for pharmaceutical applications:

- Spatial Scanning (Pushbroom): This method utilizes a slit to project a strip of the scene onto a dispersive element (prism or grating), capturing a full slit spectrum (x, λ) for each line of the image [10]. Pushbroom scanning is particularly suitable for conveyor belt systems in pharmaceutical manufacturing, allowing continuous quality monitoring of tablets or capsules [12].

- Spectral Scanning: In this approach, full spatial (x, y) images are captured at discrete wavelengths by exchanging optical band-pass filters [10]. This "staring" method is advantageous for static samples but may suffer from spectral smearing if there is movement within the scene.

- Snapshot Hyperspectral Imaging: These systems capture the entire datacube simultaneously without scanning, providing benefits of higher light throughput and shorter acquisition times [10]. While computationally intensive, these systems are valuable for dynamic processes in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Core Analytical Techniques for Information Extraction

Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) Classification

The Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) algorithm is a widely employed technique for measuring spectral similarity between pixel spectra and reference spectra. SAM operates on the principle that an observed reflectance spectrum can be treated as a vector in a multidimensional space, where the number of dimensions equals the number of spectral bands [14].

The mathematical foundation of SAM is expressed as: [ \alpha = \cos^{-1}\left(\frac{\sum{i=1}^{C}ti ri}{\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{C}ti^2}\sqrt{\sum{i=1}^{C}ri^2}}\right) ] where (ti) represents the test spectrum, (r_i) denotes the reference spectrum, and (C) is the number of spectral bands [15]. The resulting spectral angle α is measured in radians within the range [0, π], with smaller angles indicating stronger matches between test and reference signatures [15].

A key advantage of SAM is its invariance to unknown multiplicative scalings, making it robust to variations arising from different illumination conditions and surface orientation [14]. This characteristic is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications where tablet surface geometry and lighting conditions may vary.

Diagram 1: SAM Classification Workflow

Endmember Extraction and Spectral Unmixing

Most hyperspectral analysis workflows begin with identifying spectrally pure components, known as endmembers, which represent the fundamental constituents within the sample. In pharmaceutical contexts, these may include APIs, excipients, lubricants, or coating materials.

The NFINDR (N-Finder) algorithm is commonly employed for automatic endmember extraction, iteratively searching for the set of pixels that encloses the maximum possible volume in the spectral space [15]. Once endmembers are identified, spectral unmixing techniques decompose mixed pixel spectra into their constituent components, quantifying the abundance of each material.

Table 2: Spectral Analysis Techniques for Pharmaceutical Applications

| Technique | Mathematical Basis | Pharmaceutical Application | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM) | Cosine similarity in n-dimensional space | API identification and distribution mapping | Invariant to illumination, simple implementation | Does not consider magnitude information |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Orthogonal transformation to uncorrelated principal components | Sample differentiation and outlier detection | Data reduction, noise suppression | Loss of physical interpretability in transformed axes |

| Linear Spectral Unmixing | Linear combination of endmember spectra | Quantification of component concentrations | Physical interpretability, quantitative results | Assumes linear mixing, requires pure endmembers |

| Anomaly Detection | Statistical deviation from background | Contaminant detection, quality control | No prior knowledge required | High false positive rate in complex samples |

Principal Component Analysis for Data Exploration

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) serves as a powerful dimensional reduction technique for hyperspectral data, transforming the original correlated spectral variables into a new set of uncorrelated variables called principal components (PCs) [12]. This transformation is particularly valuable for visualizing sample heterogeneity and identifying patterns in complex pharmaceutical formulations.

In practice, the first two principal components often capture the majority of spectral variance present in the data, enabling two-dimensional visualization that can completely separate different drug samples based on their spectral signatures [12]. For example, in a study analyzing tablets containing ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, and paracetamol, the first two PCs provided clear differentiation between all sample types [12].

Experimental Protocol: Pharmaceutical Tablet Analysis

Materials and Instrumentation

A typical experimental setup for pharmaceutical tablet analysis requires specific components optimized for the spectral region of interest:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Hyperspectral Analysis

| Component | Specification | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imager | Pushbroom spectrograph with CCD camera | Spatial and spectral data acquisition | RS 50-1938 spectrograph with Apogee Alta F47 CCD [12] |

| Illumination Source | High-stability broadband source | Sample illumination | Xenon lamp (XBO, 14 V, 75 W) [12] |

| Reference Materials | Pure pharmaceutical compounds | Spectral library development | Ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, paracetamol [12] |

| Sample Presentation | PTFE tunnel or integrating sphere | Homogeneous, diffuse illumination | PTFE tunnel for conveyor belt system [12] |

| Calibration Standards | Spectralon reference disks | Radiometric calibration | 150 mm Spectralon integrating sphere [12] |

Step-by-Step Analytical Procedure

Step 1: System Configuration and Calibration Configure the hyperspectral imaging system in an appropriate scanning modality based on sample characteristics. For tablet analysis, a pushbroom scanner with a conveyor belt system is optimal [12]. Perform radiometric calibration using a standard reference target to convert raw digital numbers to reflectance values. Position the illumination source and PTFE tunnel to ensure homogeneous, diffuse illumination that minimizes shadows and specular reflections [12].

Step 2: Data Acquisition Place tablet samples on the conveyor belt moving at a constant speed (e.g., 0.3 cm/s) [12]. Set the integration time of the CCD camera to achieve optimal signal-to-noise ratio without saturation (e.g., 300 ms) [12]. Acquire hyperspectral data across the appropriate spectral range (e.g., 225-400 nm for UV characterization of common APIs) [12].

Step 3: Data Preprocessing Apply necessary preprocessing algorithms to the raw hypercube, including bad pixel correction, spectral smoothing, and noise reduction. Convert data to appropriate units (reflectance or absorbance) using the calibration data. Optionally, apply spatial binning or spectral subsetting to reduce data volume while preserving critical information.

Step 4: Spectral Library Development Extract representative spectra from pure reference materials (APIs and excipients) to build a comprehensive spectral library. For pharmaceutical analysis, include samples of pure ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, and paracetamol in both pure form and commercial formulations [12].

Step 5: Image Classification and Analysis Implement the SAM algorithm to compare each pixel spectrum in the hypercube against the reference spectral library. Set an appropriate maximum angle threshold to classify pixels while rejecting uncertain matches. Apply post-classification spatial filtering to reduce classification noise and create a thematic map showing the spatial distribution of different components.

Step 6: Validation and Quantification Validate results through comparison with conventional analytical methods such as UV spectroscopy or HPLC [12]. For quantitative applications, perform spectral unmixing to estimate the relative abundance of each component in mixed pixels.

Diagram 2: Pharmaceutical Tablet Analysis Workflow

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Sciences

Chemical Mapping and Distribution Analysis

Hyperspectral imaging enables detailed visualization of API distribution within solid dosage forms, providing critical information about content uniformity that directly impacts drug safety and efficacy. By applying SAM classification to each pixel in the hypercube, researchers can generate precise spatial maps showing the location and distribution of different chemical components [15] [12]. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying segregation issues in powder blends or detecting uneven distribution in final dosage forms.

The technology has demonstrated effectiveness in distinguishing between different painkiller formulations (ibuprofen, acetylsalicylic acid, and paracetamol) based on their UV spectral signatures, with complete separation achieved using the first two principal components [12]. This chemical mapping capability extends to monitoring API-polymer distribution in solid dispersions, a critical factor in dissolution performance and bioavailability.

Process Analytical Technology (PAT) Implementation

Hyperspectral imaging has emerged as a powerful Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tool for real-time quality control in pharmaceutical manufacturing [12]. The technology can be integrated into production lines for:

- Raw Material Identification: Rapid verification of incoming API and excipient identity using spectral matching [13].

- Blend Uniformity Monitoring: Non-destructive assessment of powder blend homogeneity before compression [13].

- Tablet Coating Analysis: Quantification of coating thickness and uniformity without destruction of dosage forms [13].

- Counterfeit Detection: Identification of substandard or falsified products through spectral signature analysis [13].

The rugged design of modern hyperspectral imaging prototypes opens possibilities for further development toward large-scale pharmaceutical applications, with UV hyperspectral imaging particularly promising for quality control of drugs that absorb in the ultraviolet region [12].

Troubleshooting Complex Formulation Challenges

Hyperspectral imaging provides unique capabilities for troubleshooting in pharmaceutical development, particularly when dealing with complex transformations affecting product performance. For example, real-time Raman imaging has facilitated troubleshooting in cases where dissolution of bicalutamide copovidone compacts presented challenges [13]. The temporal resolution of these techniques allows researchers to follow microscale events over time, providing insights into dissolution mechanisms and failure modes.

Implementation Considerations and Methodological Challenges

Data Management and Computational Requirements

The exceptionally high dimensionality of hyperspectral data presents significant computational challenges. A single hypercube may contain hundreds of millions of individual data points, requiring substantial storage capacity and processing power [10]. Effective data management strategies include:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques such as PCA or wavelet transforms can significantly reduce data volume while preserving critical information [16].

- Region of Interest (ROI) Analysis: Focusing computational resources on relevant image regions rather than processing entire datasets [14].

- Efficient Algorithm Implementation: Optimizing classification algorithms for specific hardware architectures to reduce processing time [15].

Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) has shown particular promise for improving both runtime and accuracy of hyperspectral analysis algorithms by extracting approximation coefficients that contain the main behavior of the signal while abandoning redundant information [16].

Method Validation and Quality Assurance

Robust method validation is essential for implementing hyperspectral imaging in regulated pharmaceutical environments. Key validation parameters include:

- Spectral Reproducibility: Assessment of spectral variation across multiple measurements of the same material.

- Spatial Accuracy: Verification of classification results against known sample composition.

- Limit of Detection: Determination of the minimum detectable quantity of an API within a complex formulation.

- Robustness: Evaluation of method performance under varying environmental conditions and instrument parameters.

Reference measurements using conventional techniques such as UV spectroscopy provide essential validation for hyperspectral imaging methods [12]. For example, total reflectance spectra of pharmaceutical tablets recorded with commercial UV spectrometers serve as valuable benchmarks for hyperspectral data [12].

Future Perspectives in Spectroscopic Data Interpretation

The field of hyperspectral imaging continues to evolve with emerging trends focusing on enhanced computational methods, miniaturized hardware, and expanded application domains. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are playing increasingly important roles in spectral interpretation, with sophisticated pattern recognition algorithms enabling more accurate classification of complex spectral patterns [17].

Miniaturization of hyperspectral sensors facilitates integration into various pharmaceutical manufacturing environments, including continuous manufacturing platforms and portable devices for field use [17]. These advancements, coupled with decreasing costs, are expected to accelerate adoption across the pharmaceutical industry [17].

Hyperspectral imaging will be particularly transformative for innovative production solutions such as additive manufacturing (3D printing) of drug products, where spatial location of chemical components becomes critically important for achieving designed release profiles [13]. As the technology matures, standardized data formats and processing workflows will further enhance interoperability and facilitate regulatory acceptance.

The integration of hyperspectral imaging into pharmaceutical development and manufacturing represents a significant advancement in quality control paradigms, shifting from discrete sample testing to continuous quality verification. This transition aligns with the FDA's Process Analytical Technology initiative, promoting better understanding and control of manufacturing processes [12]. As research continues, hyperspectral imaging is poised to become an indispensable tool for spectroscopic data interpretation in pharmaceutical sciences.

Vibrational and electronic spectroscopy forms the cornerstone of modern analytical techniques for biomolecular structure and dynamics. These non-destructive methods provide unique insights into molecular composition, structure, interactions, and dynamics across temporal scales from femtoseconds to hours. The integration of spatial imaging with spectral analysis has redefined analytical approaches by merging structural information with chemical and physical data into a single framework, enabling detailed exploration of complex biological samples. This comprehensive guide examines four principal spectroscopic regions—UV-vis, NIR, IR, and Raman—that have become indispensable tools across bioscience disciplines, from fundamental research to drug development.

The versatility of spectroscopic techniques lies in their ability to capture a broad spectrum of electromagnetic wavelengths, each revealing distinct insights into a sample's chemical, structural, and physical properties. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-vis) spectroscopy probes electronic transitions, infrared (IR) spectroscopy investigates fundamental molecular vibrations, near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy examines overtones and combination bands, and Raman spectroscopy provides complementary vibrational information through inelastic light scattering. When combined with advanced computational approaches and hyperspectral imaging, these methods create powerful frameworks for unraveling biomolecular complexity.

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Major Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Spectral Range | Probed Transitions | Key Biomolecular Applications | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis | 190-780 nm | Electronic transitions (π→π, n→π) | Nucleic acid/protein quantification, drug binding studies, kinetic assays | nM-μM range |

| NIR | 780-2500 nm | Overtones & combination vibrations (X-H stretches) | Process monitoring, quality control of natural products, in vivo studies | Moderate (requires chemometrics) |

| IR (Mid-IR) | 2500-25000 nm | Fundamental molecular vibrations | Protein secondary structure, biomolecular interactions, cellular imaging | Sub-micromolar for dedicated systems |

| Raman | Varies with laser source | Inelastic scattering (vibrational modes) | Cellular imaging, disease diagnostics, biomolecular composition | μM-mM (enhanced with SERS) |

Table 2: Practical Considerations for Technique Selection

| Technique | Sample Preparation | Advantages | Limitations | Complementary Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis | Minimal (solution-based) | Cost-effective, simple, versatile, quantitative via Beer-Lambert law | Limited to chromophores, scattering interference | Fluorescence, Circular Dichroism |

| NIR | Minimal (solid/liquid) | Deep sample penetration, suitable for moist samples, in vivo compatible | Complex spectral interpretation, inferior chemical specificity | IR, Raman for validation |

| IR | Moderate (often requires D₂O) | High molecular specificity, fingerprint region, label-free | Strong water absorption, limited penetration depth | Raman, X-ray crystallography |

| Raman | Minimal to complex | Minimal water interference, high spatial resolution, single-cell capability | Weak signals, fluorescence interference | IR, Surface-enhanced approaches |

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of ultraviolet (190-380 nm) and visible (380-780 nm) light by molecules, resulting from electronic transitions between molecular orbitals. When photons of specific energy interact with chromophores, they promote electrons from ground states to excited states, with the absorbed energy corresponding to specific electronic transitions. The fundamental relationship governing quantitative analysis is the Beer-Lambert law, which states that absorbance (A) is proportional to concentration (c), path length (L), and molar absorptivity (ε): A = εcL [18] [19].

Modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers incorporate several key components: a deuterium lamp for UV light and a tungsten-halogen lamp for visible light, a monochromator (typically with diffraction gratings of 1200-2000 grooves/mm for wavelength selection), sample compartment, and detectors such as photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) or charge-coupled devices (CCDs) for signal detection [19]. Advanced microspectrophotometers can be configured for transmission, reflectance, fluorescence, and photoluminescence measurements from micron-scale sample areas [20].

Biomolecular Applications and Chromophores

UV-Vis spectroscopy finds diverse applications in biomolecular research due to its sensitivity to characteristic chromophores in biological molecules. Key chromophores and their absorption maxima include:

- Proteins: Aromatic amino acids tryptophan and tyrosine (280 nm), peptide bonds (210-220 nm)

- Nucleic acids: Purine and pyrimidine bases (260 nm)

- Cofactors and pigments: NADH (340 nm), flavins (450 nm), chlorophyll (430-660 nm)

The technique is extensively used for nucleic acid and protein quantification, enzyme activity assays, binding constant determinations, and reaction kinetics monitoring. In pharmaceutical applications, UV detectors coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) ensure drug product quality by verifying compound identity and purity [21] [18]. The hyperchromic shift observed in absorption spectra can indicate complex formation between inhibitors and metal ions in electrolytes, providing insights into molecular interactions [18].

Experimental Protocol: Protein-Ligand Binding Study

Objective: Determine the binding constant between a protein and small molecule ligand.

Materials:

- Double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer with Peltier temperature controller

- Quartz cuvettes (1 cm path length)

- Protein solution in appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate, pH 7.4)

- Ligand stock solution in compatible solvent

- Matching buffer for blank measurements

Methodology:

- Prepare protein solution at concentration near its extinction coefficient (typically 0.5-2 mg/mL)

- Scan protein solution from 240-350 nm to establish baseline spectrum

- Titrate increasing concentrations of ligand into protein solution while maintaining constant volume

- Incubate mixtures for 5 minutes at constant temperature to reach equilibrium

- Measure absorption spectra after each addition, subtracting reference cuvette with buffer only

- Analyze specific wavelength shifts or isosbestic points to determine binding constant using appropriate models (e.g., Scatchard plot, nonlinear regression)

Data Analysis:

- Plot absorbance changes versus ligand concentration

- Fit data to binding isotherm to extract binding constant (Kd)

- Confirm binding stoichiometry from inflection points in titration curve

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

NIR spectroscopy (780-2500 nm or 12,500-4000 cm⁻¹) probes non-fundamental molecular vibrations, specifically overtones and combination bands resulting from the anharmonic nature of molecular oscillators. Unlike fundamental transitions in mid-IR spectroscopy, NIR bands arise from transitions to higher vibrational energy levels (2ν, 3ν, etc.) and binary/ternary combination modes (ν₁+ν₂, ν₁+ν₂+ν₃). This anharmonicity makes NIR spectroscopy particularly sensitive to hydrogen-containing functional groups (O-H, N-H, C-H), which exhibit strong absorption in this region [22].

The dominant bands in biological samples include first overtones of O-H and N-H stretches (∼6950-6750 cm⁻¹), second overtones of C-H stretches (∼8250 cm⁻¹), and combination bands involving C-H, O-H, and N-H vibrations. The high complexity and significant overlap of these bands necessitates advanced chemometric approaches for spectral interpretation [22].

Biomolecular Applications

NIR spectroscopy occupies a unique position in bioscience applications due to its deep tissue penetration (up to several millimeters) and minimal sample preparation requirements. These characteristics make it particularly suitable for:

- Non-invasive medical diagnostics: Functional NIR spectroscopy (fNIRS) for neuroimaging and tissue oximetry

- Quality control of natural products: Analysis of medicinal plants, agricultural products, and pharmaceuticals

- Process analytical technology (PAT): Real-time monitoring of bioprocesses and fermentation

- In vivo studies: Tissue characterization and metabolic monitoring without destructive sampling

The technique's ability to interrogate moist samples and provide accurate quantitative analysis makes it valuable for biological systems where water content would interfere with other spectroscopic methods [22].

Experimental Protocol: Quality Assessment of Medicinal Plant Material

Objective: Rapid quality assessment and authentication of medicinal plant material using NIR spectroscopy.

Materials:

- FT-NIR spectrometer with diffuse reflectance accessory

- Quartz sample vials or rotating cup for powdered samples

- Standard reference materials for calibration

- Grinding apparatus for sample homogenization

Methodology:

- Grind plant material to homogeneous powder (∼100 μm particle size)

- Load sample into quartz vial ensuring consistent packing density

- Acquire spectra in diffuse reflectance mode with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution

- Collect 64-128 scans per sample to improve signal-to-noise ratio

- Maintain constant environmental conditions (temperature, humidity)

- Include reference standards in each analysis batch for quality control

Data Analysis:

- Apply preprocessing methods (SNV, derivatives, MSC) to reduce scattering effects

- Develop PLS-R models for quantitative prediction of active compounds

- Use PCA and classification algorithms (SIMCA, PLS-DA) for authentication

- Validate models with independent test sets using root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP)

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

IR spectroscopy (4000-400 cm⁻¹) probes fundamental molecular vibrations arising from changes in dipole moment during bond stretching and bending. The mid-IR region contains several diagnostically important regions for biomolecules: the functional group region (4000-1500 cm⁻¹) with characteristic O-H, N-H, and C-H stretches, and the fingerprint region (1500-400 cm⁻¹) with complex vibrational patterns unique to molecular structure. Key biomolecular bands include amide I (∼1650 cm⁻¹, primarily C=O stretch) and amide II (∼1550 cm⁻¹, C-N stretch + N-H bend) for protein secondary structure, and symmetric/asymmetric phosphate stretches for nucleic acids [23] [24].

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometers dominate modern applications, employing an interferometer with a moving mirror to simultaneously collect all wavelengths, providing significant signal-to-noise advantages through the Fellgett's advantage. Typical configurations include liquid nitrogen-cooled MCT detectors for high sensitivity and various sampling accessories (ATR, transmission, reflectance) adapted for diverse sample types [23].

Biomolecular Applications and Time-Resolved Studies

IR spectroscopy has become one of the most powerful and versatile tools in modern bioscience due to its high molecular specificity, applicability to diverse samples, rapid measurement capability, and non-invasiveness. Key applications include:

- Protein secondary structure quantification: Analysis of amide I band for α-helix, β-sheet, and random coil content

- Biomolecular interaction studies: Monitoring ligand binding, protein-protein interactions, and macromolecular assembly

- Cellular and tissue imaging: FTIR microspectroscopy for spatial mapping of biochemical composition

- Time-resolved studies: Investigation of biomolecular dynamics from picoseconds to seconds

Time-resolved IR spectroscopy has revolutionized our understanding of biomolecular processes by enabling direct observation of structural changes with ultrafast temporal resolution. Techniques such as T-jump IR spectroscopy, 2D-IR spectroscopy, and rapid-scan methods allow researchers to follow biological processes across an unprecedented range of timescales (femtoseconds to hours), capturing events from H-bond fluctuations to large-scale conformational changes and aggregation processes [24].

Experimental Protocol: Protein Folding Dynamics Using T-Jump IR Spectroscopy

Objective: Investigate microsecond-to-millisecond protein folding dynamics using temperature-jump initiation with IR detection.

Materials:

- T-jump IR spectrometer with Nd:YAG laser (1.9 μm, ∼10 ns pulse) for sample heating

- Tunable IR probe source (OPO/OPA system)

- Mercury-cadmium-telluride (MCT) detector with fast response time

- Flow cell with CaF₂ windows and precise path length (50-100 μm)

- D₂O-based buffers to avoid water absorption interference

Methodology:

- Prepare protein solution in D₂O buffer (pD 7.4, 50 mM phosphate) with careful control of denaturant concentration

- Degas solution to minimize bubble formation during T-jump

- Set flow rate to ensure fresh sample for each laser shot (typically 1-10 Hz)

- Adjust T-jump laser energy to achieve 8-12 K temperature increase

- Collect time-resolved IR spectra at amide I' region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) with delay times from 100 ns to 100 ms

- Measure static spectra before and after experiment to confirm sample integrity

Data Analysis:

- Extract kinetic traces at characteristic wavelengths for different secondary structures

- Fit multi-exponential functions to obtain folding/unfolding rate constants

- Perform singular value decomposition (SVD) to identify spectral components

- Construct energy landscape models from temperature-dependent kinetics

Raman Spectroscopy

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Raman spectroscopy is based on inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from lasers in the visible, near-infrared, or near-ultraviolet range. When photons interact with molecules, most are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering), but a small fraction (∼1 in 10⁷ photons) undergoes energy exchange with molecular vibrations, resulting in Stokes (lower energy) or anti-Stokes (higher energy) scattering. The energy differences correspond to vibrational frequencies within the molecule, providing a vibrational fingerprint complementary to IR spectroscopy [25].

Modern Raman systems incorporate several key components: laser excitation sources (typically 532 nm, 785 nm, or 1064 nm to minimize fluorescence), high-efficiency notch or edge filters for laser rejection, spectrographs (Czerny-Turner or axial transmissive designs), and sensitive CCD detectors. Advanced implementations include confocal microscopes for spatial resolution down to ∼250 nm, and specialized techniques such as surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS), and coherent anti-Stokes Raman spectroscopy (CARS) for enhanced sensitivity and spatial resolution [25].

Biomolecular Applications

Raman spectroscopy provides unique advantages for biological applications, including minimal sample preparation, compatibility with aqueous environments, and high spatial resolution for cellular imaging. Key biomolecular applications include:

- Cellular imaging and disease diagnostics: Label-free molecular fingerprinting of tissues and cells for cancer detection and disease diagnosis

- Biomolecular structure analysis: Protein secondary structure, nucleic acid conformation, and lipid membrane organization

- Drug discovery and development: Monitoring intracellular drug distribution and metabolism

- Forensic science: Identification of body fluids and trace evidence analysis

Characteristic Raman bands for biological molecules include:

- Proteins: Amide I (1650-1680 cm⁻¹), Amide III (1230-1310 cm⁻¹), phenylalanine (1003 cm⁻¹)

- Nucleic acids: DNA backbone (789-811 cm⁻¹), nucleobase vibrations (728, 1485, 1575 cm⁻¹)

- Lipids: C-H stretches (2845-2885 cm⁻¹), C=C stretches (1656 cm⁻¹)

- Carbohydrates: C-O-C and C-C stretches (850-1150 cm⁻¹)

The technique has demonstrated particular utility in neurodegenerative disease research, cancer detection, and real-time monitoring of biological processes [25].

Experimental Protocol: Single-Cell Raman Analysis for Disease Detection

Objective: Identify biochemical differences between healthy and diseased cells using confocal Raman microscopy.

Materials:

- Confocal Raman microscope with 532 nm or 785 nm laser excitation

- Aluminum-coated slides or CaF₂ substrates for optimal signal collection

- Cell culture materials and fixation reagents (if not using live cells)

- Standard reference materials for wavelength calibration

Methodology:

- Culture cells under standardized conditions and plate onto appropriate substrates

- For live cell analysis, maintain physiological conditions with temperature/CO₂ control

- Fix cells with 4% paraformaldehyde if not analyzing immediately (optional)

- Set laser power to 5-20 mW at sample to minimize photodamage

- Collect spectra with 1-10 second integration time using 600 grooves/mm grating

- Acquire multiple spectra per cell from different regions (nucleus, cytoplasm)

- Include media-only background measurements for subtraction

Data Analysis:

- Preprocess spectra (cosmic ray removal, background subtraction, normalization)

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to identify major spectral variations

- Use linear discriminant analysis (LDA) or support vector machines (SVM) for classification

- Generate false-color images based on specific band intensities or multivariate scores

- Identify biomarker bands through loading plots and reference to spectral databases

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Biomolecular Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | D₂O buffers | Solvent for IR spectroscopy, reduces water absorption | Requires pD adjustment (pD = pH + 0.4) |

| Quartz cuvettes | UV-transparent containers for UV-Vis spectroscopy | Preferred for UV range below 350 nm | |

| CaF₂/BaF₂ windows | IR-transparent materials for transmission cells | Soluble in aqueous solutions, requires careful cleaning | |

| ATR crystals (diamond, ZnSe) | Internal reflection elements for FTIR-ATR | Diamond: durable, broad range; ZnSe: higher sensitivity but fragile | |

| Calibration Standards | Polystyrene films | Wavelength calibration for Raman spectroscopy | 1001 cm⁻¹ band as primary reference |

| Holmium oxide filters | Wavelength verification for UV-Vis-NIR | Multiple sharp bands across UV-Vis range | |

| Atmospheric CO₂/H₂O | Background reference for IR spectroscopy | Monitors instrument stability during measurements | |

| Specialized Reagents | SERS substrates (Au/Ag nanoparticles) | Signal enhancement in Raman spectroscopy | Provides 10⁶-10⁸ signal enhancement for trace analysis |

| Stable isotope labels (¹³C, ¹⁵N) | Spectral distinction in complex systems | Shifts vibrational frequencies for specific tracking | |

| Cryoprotectants (glycerol, sucrose) | Glass formation for low-temperature studies | Prevents ice crystal formation in frozen samples |

Advanced Integration and Data Analysis Approaches

Hyperspectral Imaging and Data Cubes

Imaging spectroscopy integrates spatial information with chemical composition, enabling comprehensive material characterization. The process involves creating a hyperspectral data cube where the X and Y axes represent spatial dimensions and the Z axis contains spectral information. This is achieved by systematically collecting spectra from multiple spatial points, either through physical rastering, scanning optics with array detectors, or selective subsampling. The resulting data cube can be processed into two-dimensional or three-dimensional chemical images representing the distribution of specific components within biological samples [21].

Advanced applications include FTIR and Raman spectral imaging of tissues, which can differentiate disease states based on intrinsic biochemical composition without staining. NIR hyperspectral imaging has been applied to quality control of pharmaceutical tablets and natural products, while UV-Vis microspectroscopy enables DNA damage assessment within single cells [21] [22] [25].

Multidimensional and Time-Resolved Spectroscopies

Two-dimensional infrared (2D-IR) spectroscopy represents a significant advancement beyond conventional IR methods, correlating excitation and detection frequencies to reveal coupling between vibrational modes and dynamical information. Similar to 2D-NMR, 2D-IR provides structural insights through cross-peaks that report on through-bond or through-space interactions. This technique has been particularly valuable for studying protein folding, hydrogen bonding dynamics, and solvation processes with ultrafast time resolution [24].

Pump-probe methods extend time-resolved capabilities across multiple timescales, combining UV/visible pump pulses with IR probe pulses to capture light-initiated processes from picoseconds to milliseconds. Temperature-jump relaxation methods similarly expand the observable timeframe for conformational dynamics, while rapid-scan and step-scan techniques enable monitoring of slower processes such as protein aggregation and fibril formation [24].

Chemometrics and Computational Analysis

The complexity of biological spectra necessitates advanced computational approaches for meaningful interpretation. Multivariate analysis techniques including principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares regression (PLSR), and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) are routinely applied to extract relevant information from spectral datasets. For NIR spectroscopy in particular, where bands are heavily overlapped, these chemometric methods are essential for correlating spectral features with chemical or physical properties [22].

Quantum chemical calculations, particularly density functional theory (DFT), provide increasingly accurate predictions of vibrational frequencies and intensities, aiding band assignment and supporting mechanistic interpretations. Molecular dynamics simulations complement experimental spectra by modeling atomic-level motions and their spectroscopic signatures, creating powerful hybrid approaches for biomolecular analysis [22] [25].

Visualizing Spectroscopic Workflows and Relationships

Diagram 1: Fundamental Relationships in Biomolecular Spectroscopy

This diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships between the four spectroscopic techniques and their biomolecular applications. Each technique probes specific molecular phenomena (electronic transitions for UV-Vis, vibrational overtones for NIR, etc.), which collectively enable comprehensive biomolecular analysis including quantitative measurements, structure determination, dynamics studies, and spatial imaging.

Diagram 2: Experimental Design Decision Pathway

This decision pathway guides researchers in selecting appropriate spectroscopic techniques based on their specific biomolecular analysis goals. The diagram illustrates how different research questions (structure analysis, quantification, dynamics studies, or spatial mapping) lead to technique recommendations, with multimodal approaches providing complementary information for comprehensive characterization.

The integration of UV-vis, NIR, IR, and Raman spectroscopy provides a comprehensive toolkit for biomolecular analysis, with each technique offering unique capabilities and insights. UV-vis spectroscopy remains unparalleled for quantitative analysis of chromophores and rapid kinetic studies. NIR spectroscopy offers exceptional utility for process monitoring and in vivo applications due to its deep penetration and compatibility with hydrated samples. IR spectroscopy provides exquisite molecular specificity for structural analysis and interactions, particularly through advanced time-resolved implementations. Raman spectroscopy complements these approaches with high spatial resolution, minimal sample preparation, and excellent performance in aqueous environments.

The future of biomolecular spectroscopy lies in multimodal integration, combining multiple techniques to overcome individual limitations and provide comprehensive characterization. Advances in instrumentation, particularly in miniaturization, sensitivity, and temporal resolution, continue to expand application boundaries. Concurrent developments in computational methods, including machine learning and quantum chemical calculations, enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from complex spectral data. Together, these spectroscopic techniques form an indispensable foundation for understanding biomolecular structure, function, and dynamics across the breadth of modern bioscience and drug development.

Spectral signatures are unique patterns of absorption, emission, or scattering of electromagnetic radiation by matter, serving as fundamental fingerprints for molecular identification and characterization. These signatures arise from quantum mechanical interactions between light and the electronic or vibrational states of molecules, providing critical insights into molecular structure, bonding, and environment. In analytical spectroscopy, decoding these signatures enables researchers to determine chemical composition, identify functional groups, and probe intermolecular interactions with remarkable specificity.

The interpretation of spectral data forms the cornerstone of modern analytical research, particularly in fields such as drug development where understanding molecular interactions at the atomic level dictates therapeutic efficacy and safety. This technical guide examines the core principles underlying spectral signatures, from the fundamental role of chromophores in electronic transitions to the characteristic vibrations of molecular bonds, while presenting advanced methodologies for data acquisition, preprocessing, and interpretation essential for rigorous spectroscopic research.

Theoretical Foundations

Chromophores and Electronic Transitions

A chromophore is the moiety within a molecule responsible for its color, defined as the region where energy differences between molecular orbitals fall within the visible spectrum [26]. Chromophores function by absorbing visible light to excite electrons from ground states to excited states, with the specific wavelengths absorbed determining the perceived color. The most common chromophores feature conjugated π-bond systems where electrons resonate across three or more adjacent p-orbitals, creating a molecular antenna for photon capture [26].

The relationship between chromophore structure and absorption characteristics follows predictable patterns:

- Conjugation Length: Extended conjugated systems with more unsaturated bonds absorb longer wavelengths of light [26]

- Auxochromes: Functional groups attached to chromophores (e.g., -OH, -NH₂) modify absorption ability by altering wavelength or intensity [26]

- Metal Complexation: Metal ions in coordination complexes (e.g., chlorophyll with magnesium, hemoglobin with iron) significantly influence absorption spectra and excited state properties [26]

Table 1: Characteristic Absorption of Common Chromophores

| Chromophore/Compound | Absorption Wavelength | Structural Features |

|---|---|---|

| β-carotene | 452 nm | Extended polyene conjugation |

| Cyanidin | 545 nm | Anthocyanin flavonoid structure |

| Malachite green | 617 nm | Triphenylmethane dye |

| Bromophenol blue (yellow form) | 591 nm | pH-dependent sulfonephthalein |

Molecular Bonds and Vibrational Transitions

While chromophores govern electronic transitions in UV-visible spectroscopy, molecular bonds produce characteristic signatures in the infrared region through vibrational transitions. When electromagnetic radiation matches the natural vibrational frequency of a chemical bond, absorption occurs, providing information about bond strength, order, and surrounding chemical environment. These vibrational signatures are highly sensitive to molecular structure, hybridization, and intermolecular interactions such as hydrogen bonding.

The fundamental principles governing vibrational spectra include:

- Energy States: Vibrational energy levels are quantized, with transitions occurring between these states when IR radiation is absorbed

- Selection Rules: For a vibration to be IR-active, it must produce a change in the dipole moment of the molecule

- Group Frequencies: Specific functional groups absorb characteristic IR frequencies relatively independently of the rest of the molecule

Table 2: Characteristic Vibrational Frequencies of Common Functional Groups

| Functional Group | Bond | Vibrational Mode | Frequency Range (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxyl | O-H | Stretch | 3200-3650 |

| Carbonyl | C=O | Stretch | 1650-1750 |

| Amine | N-H | Stretch | 3300-3500 |

| Methylene | C-H | Stretch | 2850-2960 |

| Nitrile | C≡N | Stretch | 2200-2260 |

| Azo | N=N | Stretch | 1550-1580 |

Experimental Methodologies

Spectroscopic Techniques for Signature Acquisition

Different spectroscopic techniques probe various aspects of molecular structure through distinct physical phenomena, each providing complementary information about the system under investigation.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy measures electronic transitions involving valence electrons in the 190-780 nm range [27]. The technique identifies chromophores and measures their concentration through the Beer-Lambert law, with applications in reaction monitoring and purity assessment.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy probes fundamental molecular vibrations in the mid-infrared region (400-4000 cm⁻¹), providing detailed information about functional groups and molecular structure [27]. Characteristic absorption bands enable identification of specific bonds, with advanced techniques like Fourier-Transform IR (FTIR) enhancing sensitivity and resolution.

Raman Spectroscopy complements IR spectroscopy by measuring inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source [27]. Raman is particularly sensitive to symmetrical vibrations and non-polar bonds, with advantages including minimal sample preparation and compatibility with aqueous solutions.

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy investigates emission from electronically excited states, providing information about chromophore environment and energy transfer processes [28]. The technique offers exceptional sensitivity for probing chromophore interactions and quantum efficiency.

Advanced Protocol: Chromophore-Solvent Interaction Analysis

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for investigating chromophore-environment interactions through combined spectroscopic and computational methods, adapted from recent research on machine-learning-assisted vibrational assignment [29].

Objective: To characterize the spectral signatures of chromophore-solvent interactions and identify specific vibrational modes affected by noncovalent bonding.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-purity organic chromophore (e.g., tetracene, rubrene)

- Anhydrous spectroscopic-grade solvents

- FTIR spectrometer with attenuated total reflection (ATR) accessory

- Raman spectrometer with 785 nm excitation laser

- Photoluminescence spectrometer with temperature control

- Computational resources for hybrid DFT/MM calculations

Procedure:

Sample Preparation

- Prepare chromophore solutions at multiple concentrations (0.1-10 mM) in selected solvents

- For solid-state studies, incorporate chromophores into host matrices (e.g., ferrocene crystals) at low doping densities using Physical Vapor Transport method [28]

- Ensure uniform sample presentation with controlled path length for solution studies

Spectral Acquisition

- Collect FTIR spectra with 2 cm⁻¹ resolution, averaging 64 scans per sample

- Acquire Raman spectra using 785 nm excitation at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution with multiple acquisitions to minimize cosmic ray artifacts

- Perform photoluminescence measurements with temperature variation (4-300K) to isolate emission features

- Record reference spectra of pure solvents and host matrices for background subtraction

Data Preprocessing

- Apply cosmic ray removal using Multistage Spike Recognition algorithm [30]

- Implement baseline correction through Morphological Operations or Piecewise Polynomial Fitting [30]

- Normalize spectra using vector normalization or standard normal variate transformation

- Perform smoothing with Savitzky-Golay filters (2nd polynomial, 9-15 point window)

Spectral Analysis

- Decompose IR spectra into contributions from molecular fragments using machine-learning-based approaches [29]

- Identify hydrogen-bond signatures through frequency shifts and intensity changes in vibrational bands

- Calculate quantum yield enhancements from integrated emission intensities compared to reference samples

- Correlate experimental findings with hybrid Density-Functional Theory/Molecular Mechanics simulations

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Spectral Preprocessing Framework

Raw spectral data invariably contains artifacts and noise that must be addressed before meaningful interpretation can occur. A systematic preprocessing pipeline is essential for extracting accurate chemical information, particularly for machine learning applications [30].

Critical Preprocessing Steps:

Cosmic Ray Removal

- Mechanism: Detect and replace outlier spikes using multistage recognition algorithms

- Methods: Moving Average Filter, Missing-Point Polynomial Filter, Wavelet Transform with K-means clustering

- Performance: Automated detection with >99% accuracy for isolated artifacts

Baseline Correction

- Challenge: Remove low-frequency drifts from instrumental or scattering effects

- Algorithms: Piecewise Polynomial Fitting, B-Spline Fitting, Morphological Operations

- Optimization: Adaptive parameter selection to preserve true spectral features

Scattering Correction

- Application: Particularly crucial for NIR spectroscopy of biological samples

- Techniques: Multiplicative Signal Correction, Standard Normal Variate transformation

Normalization

- Purpose: Minimize systematic errors from concentration or path length variations

- Approaches: Vector normalization, Min-Max scaling, Probabilistic quotient normalization

Spectral Derivatives

- Benefits: Enhance resolution of overlapping peaks, eliminate baseline offsets

- Implementation: Savitzky-Golay derivatives (1st and 2nd order)

Machine Learning for Spectral Interpretation

Advanced machine learning techniques are transforming spectral data analysis by enabling automated interpretation of complex signatures and extraction of subtle patterns beyond human perception [29] [31].

Extreme Learning Machines (ELM) provide rapid solutions for spectral analysis problems through randomization-based learning algorithms. When incorporated with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for dimensionality reduction, ELM achieves prediction inaccuracies of less than 1% for quantitative spectral analysis [31]. The method significantly reduces reliance on initial guesses and expert intervention in analyzing complex spectral datasets.

Fragment-Based Decomposition represents a chemically intuitive approach that decomposes IR spectra into contributions from molecular fragments rather than analyzing atom-by-atom contributions [29]. This machine-learning-based method accelerates vibrational mode assignment and rapidly reveals specific interaction signatures, such as hydrogen-bonding in chromophore-solvent systems.

Deep Learning Architectures including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and deep ELMs achieve classification accuracies exceeding 97% for complex spectral patterns [31] [30]. These approaches automatically learn hierarchical feature representations from raw spectral data, minimizing the need for manual feature engineering.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spectral Signature Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrocene host crystals | Organometallic matrix for chromophore isolation | Provides optical transparency and spin shielding; grown by Physical Vapor Transport for high purity [28] |

| Tetracene and rubrene chromophores | Model polyacene quantum emitters | Exhibit bright emission and well-characterized spectral features; suitable for single-molecule studies [28] |

| Deuterated solvents | NMR and IR spectroscopy | Minimizes interference from solvent protons; enables spectral window observation |

| FTIR calibration standards | Instrument performance verification | Polystyrene films for frequency validation; NIST-traceable reference materials |

| Spectral databases (SDBS, NIST) | Reference data for compound identification | Contain EI mass, NMR, FT-IR, and Raman spectra for >30,000 compounds [32] |

| ATR crystals (diamond, ZnSe) | Internal reflection elements | Enable direct sampling of solids/liquids without preparation; diamond provides chemical inertness |

| Quantum yield standards | Fluorescence reference materials | Certified chromophores (quinine sulfate, rhodamine) for emission quantification |

Applications in Drug Development and Molecular Research

Case Study: Isolated Chromophore Systems for Quantum Applications

Research on chromophores isolated within organometallic host matrices demonstrates how spectral signature analysis enables advances in quantum information science. When tetracene or rubrene chromophores are incorporated at minimal densities into ferrocene crystals, the ensemble emission shows enhanced quantum yield and reduced spectral linewidth with significant blue-shift in photoluminescence [28]. These spectral modifications indicate successful isolation of individual chromophores and suppression of environmental decoherence, critical requirements for molecular quantum systems.

Key findings from this research include:

- Enhanced Quantum Yield: Isolated chromophores in ferrocene matrices show 3.2-5.8× nominal increase in emission intensity compared to crystalline forms [28]

- Line Narrowing: Reduced inhomogeneous broadening indicates minimized environmental fluctuations

- Modified Vibrational Structure: New Raman peaks suggest altered molecular symmetries in the host environment

- Magnetic Shielding: Ferromagnetic iron atoms in the host matrix potentially block external magnetic fluctuations

Pharmaceutical Analysis and Quality Control

Spectral signature analysis forms the foundation of modern pharmaceutical quality control, with applications spanning raw material identification, reaction monitoring, and final product verification. UV-vis detectors coupled with HPLC systems provide final identity confirmation before drug release, leveraging the specific chromophore signatures of active pharmaceutical ingredients [27]. Multivariate analysis of NIR spectra enables non-destructive quantification of blend uniformity in solid dosage forms, while IR spectroscopy confirms polymorph identity critical for drug stability and bioavailability.

Spectral signatures provide a fundamental bridge between molecular structure and observable physical phenomena, with sophisticated analytical techniques now enabling researchers to decode complex interactions at unprecedented resolution. The integration of advanced computational methods, particularly machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition and fragment-based analysis, is transforming spectral interpretation from art to science. As spectroscopic technologies continue to evolve alongside computational power, researchers' ability to extract meaningful chemical information from spectral signatures will further expand, driving innovations in drug development, materials science, and quantum technologies. The ongoing refinement of standardized protocols, reference databases, and multivariate analysis tools ensures that spectral signature analysis will remain a cornerstone of molecular research across scientific disciplines.

From Theory to Therapy: Spectroscopic Techniques Driving Drug Discovery and Diagnostics

The complexity of biological systems demands analytical tools that can probe dynamic metabolic activity, molecular composition, and cellular structures with minimal perturbation. Advanced optical imaging platforms that integrate Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS), Multiphoton Fluorescence (MPF), and Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging Microscopy (FLIM) represent a technological frontier in biological and biomedical research. These multimodal approaches provide complementary information that enables researchers to visualize biochemical processes with unprecedented specificity and temporal resolution within native tissue environments. The integration of these techniques is particularly valuable for investigating drug delivery pathways, metabolic regulation, and disease progression in complex biological systems [33] [34].

These platforms are revolutionizing how researchers interpret spectroscopic data by correlating chemical-specific vibrational information with functional fluorescence readouts. Within the context of spectroscopic data interpretation, each modality contributes unique dimensions of information: SRS provides label-free chemical contrast based on intrinsic molecular vibrations, MPF enables specific molecular tracking of labeled compounds and endogenous fluorophores, and FLIM adds another dimension by detecting microenvironmental changes that affect fluorescence decay kinetics. This multidimensional data acquisition is particularly powerful for studying heterogeneous biological samples where multiple molecular species coexist and interact within intricate spatial arrangements [33] [35] [36].

For drug development professionals, these integrated platforms offer powerful capabilities for visualizing the spatiotemporal distribution of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and their metabolites within tissues. The ability to repeatedly image the same sample or living subject over time provides critical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data that can accelerate drug development cycles. Furthermore, the combination of invasive and non-invasive imaging modalities bridges the gap between detailed ex vivo analysis and in vivo clinical translation, making these platforms particularly valuable for preclinical studies [33].

Fundamental Principles of Individual Techniques

Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) Microscopy