Green Alternatives: Replacing Toxic Solvents in Spectroscopic Analysis for Sustainable Labs

This article explores the paradigm shift towards green solvents in spectroscopic analysis, addressing the critical need for sustainable and safer laboratory practices.

Green Alternatives: Replacing Toxic Solvents in Spectroscopic Analysis for Sustainable Labs

Abstract

This article explores the paradigm shift towards green solvents in spectroscopic analysis, addressing the critical need for sustainable and safer laboratory practices. It provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of green chemistry, a detailed analysis of modern solvent alternatives like NADES and bio-based solvents, practical strategies for method optimization and troubleshooting, and validation through comparative case studies from HPLC and NMR. The content synthesizes the latest 2025 research to offer a roadmap for reducing environmental impact while maintaining analytical efficacy.

The Why and What: Foundations of Green Solvents in Modern Analysis

The Environmental and Health Imperative for Solvent Replacement

FAQs: Transitioning to Green Solvents in Spectroscopic Analysis

Why is replacing solvents like DMF an urgent issue now? The urgency stems from a combination of new regulatory restrictions and a growing understanding of severe health risks. Since December 2023, the European Union has restricted the use of DMF due to its reproductive health hazard (it may damage fertility or the unborn child) [1]. Scientifically, pervasive toxicity from industrial chemicals is a major concern, with exposure linked to rises in infertility, cancer, and neurological conditions [2]. From a practical perspective, continuing to use restricted solvents risks disrupting research and analytical workflows.

What are the primary health risks associated with conventional solvents? Many conventional solvents pose significant health risks. DMF, for example, carries the hazard statement H360, indicating it may damage fertility or the unborn child [1]. Broadly, synthetic chemicals can cause harm through mechanisms like endocrine disruption and oxidative stress [2]. For instance, high PFAS exposure has been linked to a more than 50% reduction in sperm counts [2].

How do I select a green solvent without compromising my analytical results? Successful solvent substitution requires a systematic approach. A 2025 study on benchtop NMR analysis of pyrolysis oils demonstrated that ethyl lactate could effectively replace DMF in a derivatization protocol for quantifying carbonyl groups, yielding comparable results to traditional methods [1]. The key is to evaluate alternative solvents based on their physical properties (e.g., ability to dissolve both the derivatizing agent and sample components), their spectroscopic transparency in your region of interest, and their green credentials [1] [3].

Are green solvents as effective as traditional ones? Yes, when selected appropriately. Research shows that substitutes like ethyl lactate can perform as well as harmful solvents like DMF in specific applications, such as 19F benchtop NMR analysis, without affecting the quantitative results [1]. Furthermore, using green solvents can sometimes offer additional advantages, such as allowing the use of more aqueous mixtures, which further reduces environmental impact and cost [1].

What are the common challenges when switching solvents, and how can I overcome them? Common challenges include the higher initial cost of some bio-based solvents, potential performance limitations in certain applications, and the need for method re-validation [4]. To overcome these, start by consulting published method-success stories, such as the replacement of DMF with ethyl lactate [1]. Always change one variable at a time during method development and carefully plan your experiments to ensure the new solvent system is robust and reproducible [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Spectral Quality or Signal After Solvent Replacement

Potential Cause: The new green solvent has different chemical properties (e.g., polarity, viscosity) that affect the derivatization reaction efficiency or sample stability.

Solution:

- Verify Reaction Completion: Ensure the alternative solvent fully dissolves your sample and derivatizing agent. For example, in replacing DMF with ethyl lactate for 19F NMR, confirm that the reaction mixture is homogenous [1].

- Check for Solvent Interference: Ensure the solvent does not have interfering spectral signals. For FT-IR, deuterated solvents like CDCl3 are excellent alternatives due to their mid-IR transparency [6].

- Optimize Parameters: You may need to adjust reaction time, temperature, or solvent-to-sample ratios. The switch to ethyl lactate allowed for an increased amount of water in the solvent mixture, which optimized the system further [1].

Problem 2: Inconsistent Results Between Traditional and Green Solvent Methods

Potential Cause: Insufficient homogenization of the sample or matrix effects from the new solvent system.

Solution:

- Standardize Sample Prep: Inadequate sample preparation causes up to 60% of analytical errors [6]. For solid samples, ensure proper grinding to a consistent particle size (e.g., <75 μm for XRF) [6].

- Use Internal Standards: Incorporate an internal standard to compensate for any matrix effects or instrument drift, a practice crucial in techniques like ICP-MS [6].

- Change One Variable at a Time: When troubleshooting, only alter the solvent type initially. If you change multiple parameters simultaneously (e.g., solvent and sample purification method), you will not know which change resolved the issue [5].

Problem 3: Precipitation or Phase Separation in New Solvent Mixtures

Potential Cause: The green solvent may have different miscibility or solvation power compared to the traditional solvent.

Solution:

- Explore Aqueous Mixtures: Some green solvents, like ethyl lactate, are tolerant of water and can form effective aqueous mixtures, which can be a cost-effective and greener solution [1].

- Evaluate Other Green Alternatives: If one bio-based solvent fails, others might succeed. Research indicates that besides ethyl lactate, solvents like Cyrene and γ-valerolactone have been reviewed as potential DMF replacements, though their suitability is application-dependent [1].

- Confirm Purity: Use high-purity, MS-grade solvents and reagents to minimize contamination that could lead to precipitation [5].

Experimental Protocols: A Case Study in Replacing DMF with Ethyl Lactate in 19F NMR

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, details the methodology for substituting the hazardous solvent DMF with bio-derived ethyl lactate for the derivatization and analysis of carbonyl groups in pyrolysis bio-oils using benchtop 19F NMR [1].

Background and Principle

The accurate analysis of carbonyl-containing species in bio-oils is vital for assessing their stability as alternative fuels. This method uses 4-(trifluoromethyl)phenylhydrazine as a derivatizing agent to selectively tag carbonyl compounds, introducing 19F nuclei into the sample. This allows for a sparser, more interpretable 19F NMR spectrum on a benchtop instrument, eliminating the need for cryogens [1].

Materials and Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Specification/Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Lactate | Green solvent for derivatization. Replaces DMF. | Bio-derived, racemic mixture. Serves as the primary reaction medium [1]. |

| 4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenylhydrazine | Derivatizing agent. | Introduces 19F nuclei specifically into carbonyl groups for NMR detection [1]. |

| Pyrolysis Oil Sample | Analytic. | e.g., Produced from oak, willow, or miscanthus via fast pyrolysis [1]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Reaction quench. | 0.1 M solution. Used to stop the derivatization reaction [1]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (e.g., DMSO-d6) | NMR lock solvent. | Provides a stable deuterium signal for the benchtop NMR instrument lock [1]. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

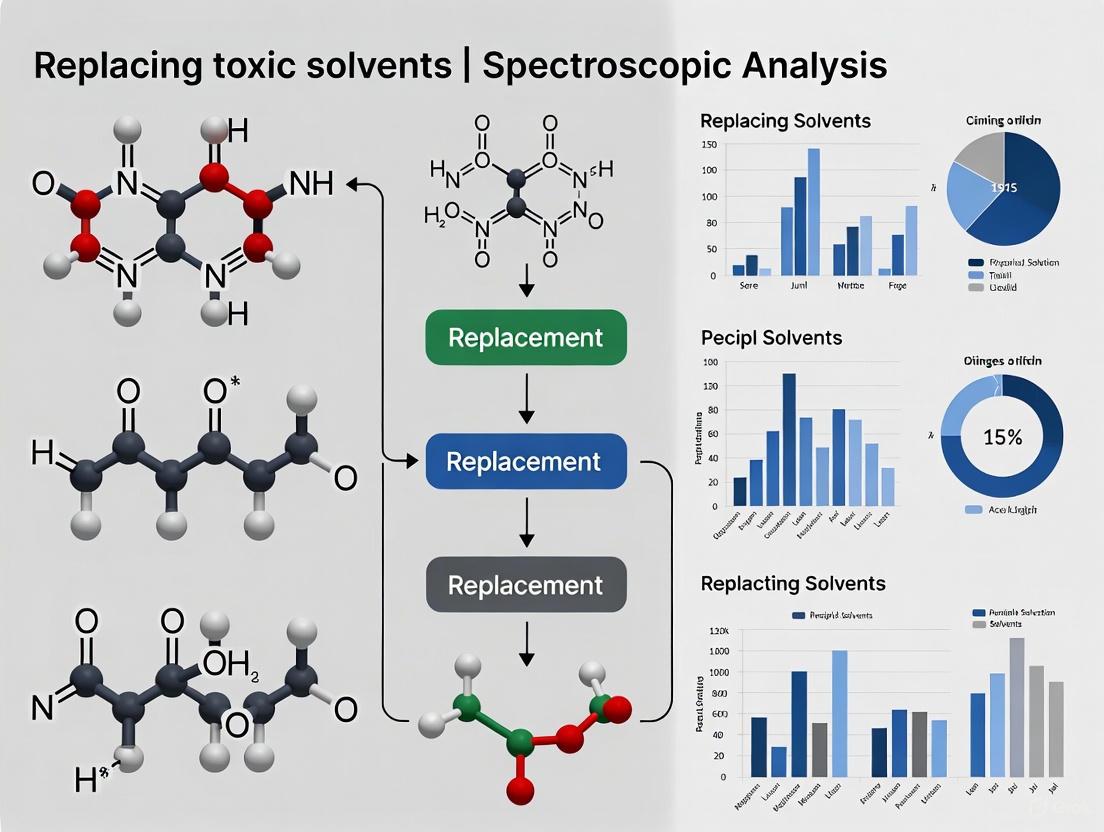

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for the solvent replacement protocol.

Data Interpretation and Validation

- Quantification: The total carbonyl content estimated from the 19F NMR spectra acquired using the ethyl lactate method should be comparable with those produced by traditional methods like titration [1].

- Functional Group Analysis: The spectra should be detailed enough to allow quantification of different carbonyl functional groups (e.g., aldehydes vs. ketones) present in the oil [1].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for Green Solvent Transition

| Item | Category | Function & Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Lactate | Bio-derived Solvent | A versatile, low-toxicity, biodegradable solvent effective for reactions like derivatization in NMR analysis [1] [3]. |

| Lactate Esters (e.g., Methyl Lactate) | Bio-derived Solvent | A class of green solvents known for low toxicity and volatile organic compound (VOC) emissions [4]. |

| D-Limonene | Bio-derived Solvent | Derived from citrus peel, used as a renewable solvent in cleaning and formulation applications [4]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Supercritical Fluid | A non-toxic, non-flammable solvent for selective extraction, minimizing environmental impact [3]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Designer Solvent | Tunable solvents with unique properties for specialized synthesis and extraction processes [3]. |

| CHEM21 Scoring System | Assessment Tool | A framework for quickly analyzing and visualizing the environmental and health hazards of chemicals [1]. |

| FDA's Expanded Decision Tree (EDT) | Assessment Tool | A screening tool to predict the chronic oral toxicity of chemicals based on their structural features [7]. |

Core Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is a transformative discipline that integrates the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies, aiming to reduce the environmental and human health impacts traditionally associated with chemical analysis [8]. For researchers in spectroscopic analysis, this means redesigning workflows to minimize or eliminate toxic solvents, reduce energy consumption, and prevent the generation of hazardous waste, all while maintaining the high standards of accuracy and precision required in drug development and research [9].

The following FAQs, troubleshooting guides, and experimental protocols are designed to support scientists in replacing traditional, often toxic, solvents with safer, more efficient alternatives in their spectroscopic analyses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle of Green Analytical Chemistry? The core principle is source reduction: minimizing waste by reducing the amount of samples and reagents used. It is the most fundamental way to make any analytical process more sustainable. This principle advocates for preventing waste generation in the first place, rather than treating or cleaning it up after it has been created [10] [9].

Q2: How do sustainable lab practices benefit a lab's bottom line? Sustainable lab practices lead to significant cost savings. By using fewer chemicals, generating less waste, and consuming less energy, labs can lower their operational expenses while simultaneously improving safety and efficiency. Case studies show reductions in solvent use by over 90% and energy consumption by 80-90% [11] [9].

Q3: Are green chemistry methods as accurate as traditional ones? Yes. While validation is crucial for new methods, modern eco-friendly analysis techniques have been developed to provide results that are just as accurate and reliable as traditional methods, often with added benefits like speed and reduced cost. For instance, Molecular Rotational Resonance (MRR) spectroscopy meets ICH and USP requirements for residual solvent analysis, offering unparalleled selectivity [9] [12].

Q4: What are the main categories of green solvent alternatives? The main directions in green solvents are:

- Substitution of hazardous solvents with those that show better environmental, health, and safety properties.

- Bio-derived solvents, such as Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES).

- Supercritical fluids, like supercritical CO₂.

- Ionic liquids and their greener counterparts, NADES [13] [8].

Q5: What is the easiest way to start making a lab more environmentally safe? The easiest way to begin is by implementing simple changes like minimizing solvent use in routine procedures, exploring micro-scale techniques for common assays, and properly sorting and recycling lab waste. A subsequent step could be to replace one toxic solvent in a frequently used protocol with a greener alternative [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Solvent Waste Generation in Sample Preparation

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause #1: Use of traditional, volume-intensive extraction techniques.

- Solution: Transition to solventless or reduced-solvent techniques.

- Action: Implement Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME). This technique uses a solid fiber to extract analytes from a sample, eliminating the need for liquid solvents entirely [9].

- Validation: Compare the recovery rates and detection limits of target analytes between the old and new methods to ensure data integrity.

Cause #2: Large sample sizes requiring large solvent volumes.

- Solution: Embrace miniaturization.

- Action: Scale down analytical procedures. Use micro-extraction techniques or lab-on-a-chip technology, which can handle microliter to nanoliter volumes, dramatically cutting down on solvent and sample consumption [9].

- Validation: Conduct a method comparison to confirm that precision and accuracy are maintained at the smaller scale.

Cause #3: Reliance on organic solvents for spectroscopic sample preparation.

- Solution: Replace organic solvents with Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES).

- Action: For extracting contaminants or analytes from solid food or plant samples, use a synthesized NADES. Their tunable properties allow for efficient extraction of a wide range of compounds [13].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If the viscosity of the NADES is too high, add a controlled amount of water (typically 10-25%) to modulate its physicochemical properties, reducing viscosity and increasing conductivity [13].

Problem: Difficulty Analyzing Low-Volatility Residual Solvents

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Limitations of static headspace gas chromatography (SH-GC).

- Solution: Employ orthogonal analytical techniques like Molecular Rotational Resonance (MRR) spectroscopy.

- Action: For analyzing low-volatility Class 2 residual solvents (e.g., DMSO, formamide, N-methylpyrrolidone) that SH-GC struggles with, use MRR. MRR's exceptional chemical selectivity allows for direct analysis of complex mixtures without chromatographic separation [12].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Ensure the analyte has a permanent dipole moment, as this is a prerequisite for MRR spectroscopy. The technique is suitable for online measurement applications and continuous manufacturing support [12].

Problem: Need for Real-Time Process Monitoring

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Offline analysis causing delays and inefficiencies.

- Solution: Implement Process Analytical Technology (PAT) tools like Raman or Near Infra-Red (NIR) spectroscopy.

- Action: Use inline Raman probes to monitor solvent content during distillation or solvent exchange operations in real-time. This provides immediate data for process control, reducing analysis times from hours to minutes [14].

- Troubleshooting Tip: To build a robust quantitative model, collect a sufficient set of calibration samples that cover the expected concentration range of the solvents involved. Use chemometric tools to correlate spectral data with reference values (e.g., from GC) [14].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Solvent-Free Analysis Using Near Infra-Red (NIR) Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the replacement of solvent-based hop acid analysis with NIR, as demonstrated by BarthHaas [11].

1. Goal: To accurately determine analyte concentration (e.g., alpha acids in hops) without using toxic solvents like toluene and methanol.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| NIR Spectrometer | The core instrument for non-destructive, rapid analysis. |

| Representative Sample Set | A diverse set of samples with known reference values (e.g., via traditional solvent method) is crucial for model building. |

| Data Analysis Software & Partner | For developing predictive chemometric models that correlate NIR spectra to analyte concentration. |

| Reusable Sample Cups/Cells | Enables circular economy principles by eliminating disposable glassware and solvent waste. |

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Proof of Concept. Test the NIR method on a small subset of samples to confirm feasibility for your specific analyte and matrix.

- Step 2: Data Collection. Acquire NIR spectra from a large and diverse set of calibration samples. In parallel, analyze these same samples using the validated reference method to obtain "true" concentration values.

- Step 3: Model Development. In collaboration with data scientists, use chemometric tools to build a predictive model that correlates the spectral data to the reference concentration values.

- Step 4: Implementation & Validation. Integrate the NIR method into routine analysis. Continuously validate its performance against quality control samples to ensure ongoing accuracy.

4. Workflow Diagram: The following diagram illustrates the transition from a traditional solvent-based method to a green NIR-based workflow.

Protocol: Synthesis and Use of Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) for Extraction

This protocol provides a general method for creating and applying NADES as a green alternative to organic solvents for extracting contaminants from food or natural product samples [13].

1. Goal: To synthesize a NADES and use it for the efficient extraction of analytes.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | e.g., Choline Chloride (a natural, biodegradable salt). Forms the base of the eutectic mixture. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | e.g., Organic acids (citric, malic), sugars (glucose), urea. Determines the polarity and properties of the NADES. |

| Heating/Magnetic Stirrer | To facilitate the formation of the eutectic mixture. |

| Water Bath | For temperature-controlled synthesis. |

| Deionized Water | To modulate the viscosity and polarity of the final NADES. |

3. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Selection of Components. Choose a combination of HBA and HBD based on the target analytes. Common starting points are choline chloride with urea (1:2) or with citric acid (1:1).

- Step 2: Synthesis.

- Weigh the HBA and HBD in the desired molar ratio into a glass vial.

- Add a small amount of water (typically 10-20% by weight) to reduce the final viscosity.

- Close the vial and heat the mixture to ~80 °C with continuous stirring (300-500 rpm) for 30-90 minutes, until a clear, homogeneous liquid is formed.

- Step 3: Extraction.

- Add the solid sample and the synthesized NADES to an extraction vessel.

- Utilize auxiliary energy (e.g., ultrasound or microwave) to enhance extraction efficiency and reduce time.

- Centrifuge the mixture to separate the extract from the solid residue.

- Step 4: Analysis. The NADES-based extract can often be directly injected or diluted for analysis using techniques like LC-MS or GC-MS.

4. Workflow Diagram: The following diagram outlines the process of creating a tailored NADES for green extraction.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Impact of Green Methods

The following tables summarize the quantitative benefits of adopting Green Analytical Chemistry principles, based on real-world case studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Benefits of Replacing Solvent-Based Analysis with NIR Spectroscopy [11]

| Parameter | Traditional Solvent Method | Green NIR Method | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Use (Methanol/Toluene) | ~42.3 Liters (Baseline) | ~4.2 Liters | ~90% |

| Analysis Time | 30 min - 4 hours | 1 - 2 minutes | >90% |

| Electricity Usage | Baseline | -- | 80-90% |

| Hazardous Waste Generation | Baseline | -- | ~90% |

| CO₂e Emissions from Solvents | ~22.11 kg (Baseline) | ~2.21 kg | ~90% |

Table 2: Comparison of Traditional vs. Green Analytical Methods [9] [10]

| Principle | Traditional Method | Green Analytical Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Size | Milliliters or more | Microliters to Nanoliters (Miniaturization) |

| Solvent Choice | Hazardous solvents (e.g., chloroform, benzene) | Non-toxic alternatives (e.g., water, ethanol, NADES) |

| Waste Generation | High volume of hazardous waste | Minimal waste, often non-hazardous |

| Energy Use | High (e.g., heating, vacuum pumps) | Low (e.g., room temperature methods, NIR) |

| Safety Profile | High-risk due to toxic chemicals | Low-risk, improved lab safety |

In the context of spectroscopic analysis, the choice of solvent is critical, not only for the quality of the data but also for the safety of the researcher and the environment. Green solvents are environmentally friendly chemical solvents designed to reduce the negative ecological and health impacts associated with traditional petrochemical solvents. Their development and adoption are central to the principles of green chemistry, aiming to minimize toxicity, reduce waste, and use renewable resources [15] [16]. This guide provides a technical framework for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to replace toxic solvents in their spectroscopic workflows with safer, sustainable alternatives.

FAQs: Transitioning to Green Solvents in Spectroscopic Analysis

What defines a "green solvent" and what are its key characteristics?

A green solvent is defined by a set of characteristics that collectively reduce its environmental and health footprint. While no single solvent is perfect, the ideal green solvent should excel in several of the following areas [15] [16] [17]:

- Low Toxicity: Poses minimal risk to human health and ecosystems, unlike traditional solvents such as benzene or chloroform [16] [17].

- Biodegradability: Can be broken down by microorganisms, preventing persistent accumulation in the environment [15] [17].

- Renewable Origin: Derived from biomass (e.g., crops, agricultural waste) rather than finite petrochemical sources [15] [16].

- Low Volatility: Exhibits low vapor pressure, which reduces the emission of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and improves air quality [16] [17].

- High Performance: Effectively dissolves the target analytes and is compatible with analytical techniques without interfering with the analysis [16] [17].

- Reusability and Recyclability: Can be recovered and reused in processes, reducing waste generation and costs [17].

How do I know if a "green" solvent is truly sustainable?

A solvent's "greenness" is not intrinsic; it must be evaluated through a holistic lifecycle assessment (LCA). A solvent that performs well in the lab may have a significant environmental burden from its production phase [18] [16] [19]. Key considerations include:

- Full Lifecycle Impact: Assess the environmental cost from feedstock source (renewable vs. fossil fuel), manufacturing energy, and disposal. For example, some ionic liquids have excellent in-use properties but are synthesized from petrochemicals via energy-intensive processes [18] [16].

- Techno-Economic Analysis: Evaluate both the environmental and economic performance. A 2023 study found that while a solvent like Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) may have a favorable environmental profile, its production costs can make it less competitive, whereas Ethyl Acetate (EA) can offer a balanced profile [18].

- Synthesis Method: The environmental impact of the synthesis pathway itself (e.g., chemical imidization vs. one-step polymerization) can become significant when processes are scaled up [18]. Always consult lifecycle assessment data when available to make an informed choice.

What are common classes of green solvents and their properties?

Green solvents can be classified into several categories based on their origin and composition. The table below summarizes the primary types and their key features.

Table 1: Common Classes of Green Solvents and Their Properties

| Solvent Class | Description & Origin | Key Properties | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents [15] [20] | Derived from renewable biomass (e.g., crops, agricultural waste). | Often biodegradable, low toxicity, renewable. | Ethyl Lactate, D-Limonene, 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) [20]. |

| Water & Supercritical Fluids [15] [16] | Water is the safest solvent. Supercritical fluids (e.g., CO₂) are above their critical point. | Water: non-toxic, safe. scCO₂: tunable solubility, non-flammable. | Supercritical CO₂ (scCO₂) [15]. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [15] [16] | Mixtures of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors with low melting points. | Low volatility, tunable, often low toxicity, simple synthesis. | Choline Chloride/Urea mixture [15]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) [15] [16] | Salts that are liquid at room temperature. | Negligible vapor pressure, thermally stable, tunable. | Imidazolium-based salts [15]. |

How do I select a green solvent to replace a toxic one in my IR spectroscopy method?

Replacing a hazardous solvent like carbon tetrachloride in IR spectroscopy requires a systematic approach focusing on spectroscopic transparency and solvation power.

- Experimental Protocol: Solvent Replacement for IR Spectroscopy

- Objective: To identify a greener solvent that produces a high-quality IR spectrum with minimal solvent interference for a given analyte (e.g., an alcohol).

- Materials: FT-IR spectrometer with liquid cell, candidate green solvents (e.g., heptane, ethyl acetate), analyte.

- Method:

- Baseline Acquisition: Collect a background spectrum for each candidate solvent using the same liquid cell.

- Analyte Preparation: Prepare solutions of your analyte (e.g., cyclohexanol) at a standard concentration in each candidate solvent.

- Spectral Collection: Record the IR spectra for each solution, ensuring consistent pathlength and instrument settings.

- Spectral Analysis:

- Identify Interference: Compare the spectra in the region of interest (e.g., O-H stretching ~3200-3600 cm⁻¹). A good solvent will have minimal absorption in this region, allowing the analyte's peak to be clearly seen.

- Fingerprint Region: Examine the fingerprint region (below ~1500 cm⁻¹), where solvent absorption can be very strong. The ideal solvent will have a "clean" fingerprint region or one that does not overlap with key analyte peaks [21].

- Evaluation: Select the solvent that provides the best combination of low toxicity, low spectral interference, and adequate dissolving power for your analyte.

What are the practical challenges when switching to green solvents?

Common challenges and their potential solutions include:

- Challenge: Altered spectral baselines or interference in critical spectral regions.

- Solution: Use spectral subtraction techniques to remove the solvent's signature. If interference is severe, consider a different class of green solvent (e.g., switching from a polar DES to a non-polar terpene like limonene).

- Challenge: Inadequate dissolving power for the target analyte.

- Solution: Explore solvent mixtures (e.g., water/ethanol) or "switchable" solvents, whose properties like polarity can be changed by an external trigger like CO₂ [15].

- Challenge: Higher viscosity affecting sample handling (common with Ionic Liquids and DES).

- Challenge: Higher cost or limited availability of some advanced green solvents.

- Solution: Start with readily available and cost-effective options like ethanol, ethyl acetate, or water-based systems. Prioritize solvents that can be easily recovered and recycled [17].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and their functions for experiments involving green solvents, particularly in spectroscopy.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Green Solvent Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Green Characteristics & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Lactate [15] [20] | A effective solvent for extracting natural products and used in paint strippers and cleaners. | Derived from corn starch; biodegradable; low toxicity; replaces toluene, acetone, and xylene. |

| D-Limonene [15] [20] | A non-polar solvent obtained from citrus peels, useful for extracting oils and hydrocarbons. | Renewable; generally recognized as safe (GRAS); readily biodegradable. |

| Choline Chloride [15] | A hydrogen bond acceptor (HBA) used to formulate Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES). | Low-cost, non-toxic, and a common nutrient. Allows for tunable solvent properties. |

| 2-Methyltetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF) [15] [20] | A replacement for THF in extractions and as a reaction medium. Derived from lignocellulosic biomass. | Renewable source; lower peroxide formation tendency compared to THF. |

| Dimethyl Carbonate (DMC) [17] [20] | A non-toxic solvent used in paints, inks, adhesives, and chemical synthesis. | Biodegradable; can be produced from CO₂ and methanol; replaces MEK and toluene. |

| Supercritical CO₂ [15] [16] | Used for extraction of pharmaceuticals and active ingredients, and for surface cleaning. | Non-toxic, non-flammable, and easily recyclable by depressurization. Requires specialized equipment. |

Visual Guide: Solvent Selection and Replacement Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for evaluating and replacing a traditional solvent with a greener alternative in a research setting.

The transition from traditional solvents to green solvents in analytical chemistry represents a pivotal shift toward sustainable science, reducing toxicity and environmental impact while maintaining analytical efficacy. For researchers in spectroscopic analysis, this shift is not merely an environmental consideration but a practical necessity driven by increasingly stringent regulations, such as those restricting the use of harmful solvents like DMF in the European Union [1]. Green solvents, derived from renewable resources and characterized by low toxicity and biodegradability, are now being successfully integrated into various spectroscopic methods, including NMR, NIR, and others, without compromising analytical performance [16]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for scientists navigating this transition, offering troubleshooting advice, experimental protocols, and essential resources to facilitate the successful adoption of green solvents in your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q1: Why should I replace traditional solvents like DMF or n-hexane in my spectroscopic analyses?

Traditional solvents present significant health, safety, and environmental challenges. N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) is classified as a reproductive health hazard (H360 statement) and its use has been restricted in the European Union since December 2023 [1]. Similarly, n-hexane is classified with class 2 reproductive toxicity and class 2 aquatic chronic toxicity [22]. From a practical perspective, green solvents can reduce environmental impact, lower user risks, and often decrease costs. Furthermore, funding bodies and scientific journals are increasingly favoring research that aligns with green chemistry principles.

Q2: I am concerned that green solvents will compromise my analytical results. How can I ensure performance is maintained?

This is a common and valid concern. The key is methodical validation. For instance, in benchtop 19F NMR analysis of pyrolysis oils, substituting DMF with ethyl lactate provided comparable results for carbonyl content quantification, with estimates aligning with those produced by titration [1]. When switching solvents, always run a parallel analysis using your old and new solvent systems on a standard or control sample. Compare key parameters like signal-to-noise ratio, resolution, and quantification accuracy to ensure data integrity is preserved.

Q3: What are the most promising classes of green solvents for spectroscopic applications?

Several classes have shown great promise, each with unique properties [16]:

- Bio-based Solvents: Derived from renewable biomass (e.g., corn, sugarcane, vegetable oils). Examples include ethyl lactate, 2-methyloxolane (2-MeOx), and cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) [16] [22].

- Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES): Mixtures of natural compounds (e.g., choline chloride and urea) that form a liquid with a melting point lower than that of either individual component. They are tunable, often biodegradable, and can be sourced from natural origins [23].

- Supercritical Fluids: Such as supercritical CO₂, which is excellent for extraction and chromatography, though it requires specialized equipment [16].

- Ionic Liquids (ILs): Salts in the liquid state with negligible vapor pressure. Their properties can be finely tuned, but their green credentials depend on their synthesis and biodegradability [16].

Q4: A green solvent failed to dissolve my sample. What are my options?

Solubility is a frequent hurdle. Your options include:

- Select an Alternative Green Solvent: Use the Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) as a theoretical tool to screen for solvents with similar solubility properties to your original, non-green solvent but with a better safety profile [22].

- Use a Solvent Mixture: Often, a mixture of a green solvent with water or another green solvent can achieve the desired solubility. Research has shown that using ethyl lactate allowed for an increase in the water content of the solvent mixture, further reducing environmental impact and cost without sacrificing performance [1].

- Apply Gentle Heating: Many green solvents have a higher boiling point than traditional ones, allowing you to gently heat the sample to enhance dissolution, provided your analyte is thermally stable.

Q5: How do I handle the higher viscosity of some green solvents, like many NaDES, for my HPLC analysis?

High viscosity can indeed be challenging for techniques like HPLC, as it leads to high backpressure. Solutions include:

- Dilution: Diluting the solvent with a miscible, low-viscosity solvent like water or ethanol can significantly reduce viscosity.

- Heating: Using a column heater can lower the effective viscosity of the mobile phase during analysis.

- Alternative Preparation: Some NaDES can be prepared with different molar ratios of their components to yield a less viscous mixture.

Research Reagent Solutions: A Green Solvent Toolkit

The table below details key green solvents and their applications, providing a starting point for your solvent substitution strategy.

Table 1: Promising Green Solvent Classes and Their Applications

| Solvent Class | Specific Examples | Key Properties & Advantages | Demonstrated Spectroscopic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate Esters | Ethyl Lactate [1] [16] | Bio-based, low toxicity, biodegradable, can tolerate water content. | Replaced DMF in 19F benchtop NMR for derivatization of pyrolysis oils [1]. |

| Bio-based Ethers | 2-Methyloxolane (2-MeOx), Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) [22] | Bio-based, good lipid solubility, lower toxicity than n-hexane. | 2-MeOx excelled in lipid extraction from oilseeds, compatible with subsequent analysis [22]. |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NaDES) | Choline Chloride/Urea, Menthol/Octanoic Acid [23] | Tunable properties, can be natural and biodegradable, low volatility. | Extensive use in extraction of bioactive compounds for analysis; potential as a medium for spectroscopy [23]. |

| Bio-based Alcohols | Bio-Ethanol, Glycerol Derivatives [16] [24] | Renewable, readily available, low toxicity. | Used in paints, coatings, and cleaning products; can be adapted for sample preparation [24]. |

| Terpenes | D-Limonene [16] [24] | Derived from citrus peels, effective non-polar solvent. | Applied in industrial cleaning and formulations; useful for extracting non-polar analytes [16]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Substituting DMF with Ethyl Lactate in Benchtop ¹⁹F NMR for Bio-oil Analysis

This protocol is adapted from a published procedure for analyzing carbonyl content in pyrolysis oils using benchtop NMR [1].

1. Principle: Carbonyl groups in complex pyrolysis oil samples are derivatized with 4-(trifluoromethyl)phenylhydrazine, introducing 19F nuclei into the sample. This allows for the acquisition of a sparse and specific 19F NMR spectrum for quantification, avoiding the overlapping signals in the crude oil spectrum.

2. Materials:

- Pyrolysis oil sample (~30 mg)

- 4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenylhydrazine (110 mg)

- Ethyl Lactate (Green solvent)

- Deionized Water

- Hydrochloric Acid (0.1 M)

- Benchtop NMR Spectrometer with 19F capability

3. Procedure: a. Derivatization Solution Preparation: Dissolve 110 mg of 4-(trifluoromethyl)phenylhydrazine in 1 mL of a 50:50 (v/v) mixture of ethyl lactate and water. b. Sample Reaction: Add the derivatization solution to approximately 30 mg of pyrolysis oil dissolved in 500 μL of ethyl lactate. Allow the reaction to proceed for 2 hours at room temperature. c. Reaction Quenching: Add 2 mL of 0.1 M hydrochloric acid to quench the reaction. d. Extraction: Extract the derivatized product using an appropriate organic solvent (e.g., diethyl ether or ethyl acetate). e. NMR Analysis: Evaporate the solvent and re-dissolve the product in an appropriate solvent for 19F NMR analysis. Acquire the spectrum on a benchtop NMR spectrometer.

4. Key Troubleshooting Tips:

- Incomplete Derivatization: Ensure the reaction is allowed to proceed for the full 2 hours. Gently stirring the reaction mixture can improve yield.

- Poor Spectral Quality: Check that the extraction step was efficient and that the final sample for NMR is free of water or other contaminants that could broaden signals.

- Precipitation: If precipitation occurs during the reaction, slightly increasing the proportion of ethyl lactate in the solvent mixture can improve solubility.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Green Solvents for Lipid Extraction

This protocol outlines a method to compare the efficiency of green solvents like 2-MeOx against n-hexane for oil extraction, relevant for subsequent spectroscopic analysis [22].

1. Principle: The extraction efficiency of different solvents is compared by measuring the yield and quality of oil extracted from a solid matrix, such as oilseed cake. Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) can be used to model and understand the dissolving mechanism.

2. Materials:

- Dry, defatted oilseed cake powder (e.g., Camellia seed cake)

- Candidate Green Solvents (e.g., 2-MeOx, CPME, Ethyl Acetate)

- Reference Solvent (e.g., n-hexane)

- Soxhlet Extraction Apparatus

- Rotary Evaporator

3. Procedure:

a. Sample Preparation: Dry the oilseed cake at 50°C for 12 hours, pulverize, and sieve to a consistent particle size (e.g., 0.25 mm).

b. Extraction: Weigh 30 g of powder into a beaker. Add solvent at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 (w/v). Stir for 1.5 hours at room temperature.

c. Solvent Removal: Separate the solid residue and evaporate the solvent from the extract using a rotary evaporator.

d. Calculation & Analysis:

* Calculate the Oil Extraction Ratio (%) using the formula: (Weight of extracted oil / (Weight of dry sample * Oil content)) * 100 [22].

* Analyze the extracted oil for composition (e.g., acylglycerols, fatty acids, tocopherols) using GC-MS or other spectroscopic techniques to compare solvent selectivity.

4. Key Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low Extraction Yield: Consider increasing the extraction temperature (if the solvent's boiling point allows) or extending the extraction time. A kinetic study can model the diffusion rate of your solvent [22].

- Solvent Loss: Due to potentially different boiling points, ensure the rotary evaporator bath temperature is optimized for the green solvent to prevent rapid evaporation or bumping.

Workflow Visualization: Green Solvent Implementation Strategy

The following diagram illustrates a logical pathway for researchers to follow when seeking to replace a traditional solvent with a greener alternative in their spectroscopic methods.

The Green Toolbox: A Guide to Modern Solvent Alternatives and Their Uses

Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES)

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues & Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Preparation | Mixture does not form a clear liquid | Incorrect molar ratio; insufficient heating or stirring | Re-check component molar ratios; gently heat to 60–80 °C with continuous stirring until a homogeneous liquid forms [25] [26] |

| Solvent solidifies at room temperature | Operating temperature is below the eutectic point; composition is off | Adjust HBA:HBD ratio; add a minimal amount of water (5-20%) to depress freezing point and lower viscosity [27] [25] | |

| Physical Properties & Handling | Extremely high viscosity, difficult to pipette | Inherently viscous network; low temperature; no water content | Warm the solvent; incorporate moderate water content; use positive-displacement pipettes [27] [25] |

| Poor extraction efficiency for target analytes | Viscosity limits mass transfer; solvent polarity mismatch with analyte | Optimize extraction parameters (temperature, time); tailor DES composition to match analyte polarity (e.g., use phenolic DES for lignans) [25] | |

| Analytical Application | Unusual chromatographic peaks or column pressure | Carryover of viscous DES components into HPLC system | Ensure adequate dilution of DES extract with mobile phase; use a guard column; avoid injecting pure DES [28] |

| Stability & Storage | Change in color or properties over time | Chemical degradation or water absorption | Prepare fresh DES when possible; store under anhydrous conditions and in sealed containers [27] [23] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What exactly are DES and NADES, and why are they considered "green"?

A Deep Eutectic Solvent (DES) is a mixture of a Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), often a quaternary ammonium salt like choline chloride, and a Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), such as urea, acids, or sugars. This combination engages in a complex hydrogen-bonding network, resulting in a significant depression of the melting point, making the mixture liquid at room temperature [29] [26]. For instance, choline chloride (mp: 302°C) and urea (mp: 133°C) form a liquid with a freezing point of 12°C at a 1:2 molar ratio [29].

Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) are a sub-class of DES where all components are primary metabolites found in nature, such as organic acids, sugars, amino acids, and choline derivatives [30] [23]. A classic example is a mixture of choline chloride and glucose.

They are considered "green" because they typically exhibit:

- Low volatility and non-flammability, reducing inhalation risks and environmental emissions [29] [26].

- Potential biodegradability and lower toxicity, especially for NADES made from food-grade constituents [30] [23].

- Tunability, allowing properties to be adjusted by changing the HBA and HBD, thus avoiding the need for more hazardous solvents [29] [31].

How do I select the right DES for my analytical application?

Selecting the appropriate DES involves matching its physicochemical properties to your analytical goal. The table below summarizes common choices based on target analytes, as demonstrated in recent research.

| Application Target | Recommended DES/NADES Composition (Molar Ratio) | Key Interaction Mechanism | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolic Antioxidants (e.g., TBHQ) | Choline Chloride : Ethylene Glycol (1:2) [25] | Hydrogen bonding | UALLME from edible oils for HPLC analysis [25] |

| Tocopherols (Vitamin E) | Choline Chloride : p-Cresol (1:2) [25] | π-π interaction | VALLE from soybean oil deodorizer distillate [25] |

| Lignans (e.g., sesamin) | Choline Chloride : p-Cresol (1:2) [25] | Hydrophobic & π-π interactions | UALLME from sesame oils [25] |

| Hydrophobic Drugs (e.g., Curcumin) | Choline Chloride : Maleic Acid (3:1) or Glucose : Sucrose (1:1) [30] | Solubilization enhancement | Improving bioavailability in pharmaceutical formulations [30] |

| Metal Ions | Choline Chloride : Urea (1:2) or other Type III DES [29] | Electrostatic & coordination | Metal extraction and electrodeposition processes [29] |

What are the best practices for preparing and storing DES to ensure experimental reproducibility?

For hot synthesis, the standard method involves weighing the HBA and HBD in the desired molar ratio into a sealed container, heating the mixture in a water bath or oven between 60°C and 80°C, and stirring continuously until a clear, homogeneous liquid forms. This can take from 30 minutes to a few hours [25] [23]. Grinding is an alternative method for components that form a liquid upon mixing and grinding at room temperature without external heat [23].

Proper storage is critical. DES and NADES are hygroscopic and can absorb water from the atmosphere, which alters their viscosity and polarity. For consistent results, store prepared solvents in sealed containers with minimal headspace. For long-term storage, desiccants or airtight vials are recommended. Monitor for changes in appearance or viscosity, and note the water content for critical applications [27] [23].

I've heard conflicting reports about DES toxicity and biodegradability. What is the current scientific consensus?

The assumption that all DES are inherently non-toxic and biodegradable simply because they are made from natural components is an oversimplification. Current research indicates that their ecotoxicity and biodegradability are highly dependent on the individual components, their molar ratios, and the resulting intermolecular interactions [27]. Some NADES show excellent biocompatibility, while other DES, particularly those with synthetic ionic components, may exhibit toxicity comparable to traditional organic solvents. It is essential to consult specific toxicity studies for the DES you plan to use and not to generalize their safety [27] [23].

Experimental Workflow: Replacing Toxic Solvents in Sample Preparation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for developing an analytical method that uses DES/NADES for sample preparation, specifically for spectroscopic or chromatographic analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in DES Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) | Choline Chlorine, Betaine, Amino Acids (e.g., L-Proline) | Forms the ionic or polar foundation of the solvent; choline chloride is most common due to low cost and low toxicity [29] [26]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) | Urea, Glycerol, Lactic Acid, Glucose, p-Cresol, Malic Acid | Interacts with the HBA to depress the melting point; determines polarity, viscosity, and extraction selectivity [29] [25]. |

| Hydrophobic DES Components | Decanoic Acid, Menthol, Thymol, p-Cresol | Enables creation of water-immiscible HDES for extracting non-polar compounds [25] [26]. |

| Extraction & Analysis Materials | Strata-X SPE Cartridges, C18 UHPLC Columns (e.g., Kromasil Ethernity), Nylon Syringe Filters (0.45 µm) | Used for clean-up, separation, and analysis of DES extracts [28]. |

| Green Metric Calculators | ACS GCI PR PMI Calculator | Tool to quantify and compare the environmental efficiency of your DES-based method against conventional protocols [23]. |

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

This guide addresses specific challenges researchers may encounter when replacing traditional solvents with bio-based alternatives in spectroscopic analysis and sample preparation.

Problem: Poor Extraction Efficiency or Recovery

- Issue: Analytes are not being effectively recovered during Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE) or Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE), leading to poor yields [32].

- Solution:

- Verify solvent compatibility: Ensure the solvent's polarity matches the target analytes. For hydrophilic compounds (logP < 0.5), 1-butanol is computationally recommended. For mid-range polarity (logP 0.5-2.6), ethyl acetate or 1-pentanol are effective. For hydrophobic compounds (logP > 2.6), cyclopentyl methyl ether is suggested [33].

- Check for analyte instability: In SPE, poor recovery might occur if analytes degrade or are protein-bound in the sample matrix. Review sample pre-treatment steps [32].

- Confirm elution solvent strength: If analytes are retained but not eluted, increase the elution solvent's strength. For bio-based solvents, consider switching from ethanol to ethyl acetate for more non-polar compounds [34] [32].

Problem: Irreproducible Results or Sample Carryover

- Issue: Inconsistent quantitative results between experimental replicates [32].

- Solution:

- Instrument Calibration: Verify analytical system function by injecting known standards. Perform repeated injections of pure standards to check injection reproducibility [32].

- Solvent Purity and Consistency: Use high-purity bio-based solvents. For SPE, compare sorbent lot numbers, as inconsistencies can cause variability [32].

- Matrix Effects: In LC-MS, matrix components can cause signal suppression/enhancement. If interferences are not removed by SPE, pre-treat samples with liquid-liquid extraction using bio-based solvents like ethyl acetate to remove lipids/fats [32].

Problem: Solvent Immiscibility or Phase Separation Issues

- Issue: Failure to achieve clean phase separation during extraction, especially from aqueous or micellar media [33].

- Solution:

- Select Appropriate Solvents: Computational and experimental studies show that only the more hydrophilic bio-based solvents (e.g., cyclopentanol, 1-butanol, ethyl acetate, 2-pentanol, 1-pentanol, 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran) provide clear phase separation in the presence of surfactants or residual organic solvents in aqueous micellar media [33].

- Modify Wash Steps: In SPE, improve sample cleanliness by using a wash solvent in which the analyte is insoluble. Ethyl acetate can be effective for removing many interferences while retaining the analyte [32].

Problem: Solvent-Related Analytical Interferences

- Issue: Solvent peaks or impurities overlap with analyte signals in chromatography or spectroscopy.

- Solution:

- Use Spectroscopic/Grade Bio-Solvents: Ensure solvents like bio-ethanol or ethyl lactate are of high analytical purity.

- Employ Blanks: Always run solvent blanks to identify and account for background signals.

- Consider Physical Properties: For GC-MS applications, note that solvents like ethyl lactate have low volatility, which may require specific inlet conditions [34].

Problem: High Toxicity or Environmental Concerns Persist

- Issue: The chosen bio-based solvent still poses health or environmental risks.

- Solution:

- Consult Solvent Selection Guides: Refer to established guides (e.g., Pfizer, GSK). Ethyl acetate and ethanol are typically "preferred," while 2-methyltetrahydrofuran is "usable" [35] [33].

- Evaluate Aquatic Toxicity: Some bio-based solvents like D-limonene are highly toxic to aquatic organisms. Consider less toxic options like ethyl lactate for such applications [34] [36].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the key advantages of using bio-based solvents over traditional petroleum-based solvents?

Bio-based solvents, derived from renewable biomass (e.g., corn, soy, citrus), offer a reduced carbon footprint as the carbon they release was recently absorbed by plants, making them theoretically carbon-neutral [34] [36]. They are often, though not always, less toxic and more biodegradable [34] [35]. For example, ethyl lactate is biodegradable, nontoxic, and has a high flash point, making it safer to handle and store [34] [36].

Can bio-based solvents directly replace traditional solvents like n-hexane or dichloromethane (DCM) in existing protocols?

In many cases, yes, but performance validation is essential. For instance, D-limonene has successfully replaced n-hexane for determining total lipids in foods and toluene in Dean-Stark moisture analysis [34]. For DCM, a mixture of ethyl acetate and ethanol can be a greener alternative in chromatographic applications, offering similar eluting strength [35]. However, metrological parameters (e.g., LOD, LOQ, precision) should be confirmed for the new solvent system [34].

Are all bio-based solvents considered "green"?

No. The "green" character is multi-faceted. A solvent's environmental impact depends on its sourcing, toxicity, biodegradability, and energy demands for production. While many bio-based solvents are greener, some, like D-limonene, can be highly toxic towards aquatic organisms [34]. The life cycle of the solvent, from production to disposal, must be evaluated [31].

How do I handle and dispose of bio-based solvents like ethyl lactate?

While many bio-based solvents are safer (e.g., Bio-Solv, an ethyl lactate blend, is not classified as a HAZMAT for volumes up to 55 gallons and contains no Hazardous Air Pollutants), standard laboratory safety practices still apply [36]. Use gloves and work in a well-ventilated area, as these solvents can remove oils from skin. Low-vapor-pressure solvents like ethyl lactate can be easily recycled via mechanical filtering or distillation [36].

What are the primary sources and production pathways for ethanol, ethyl lactate, and terpenes?

- Ethanol: Obtained from sugar-containing plants, lignocellulosic mass, algae, and straw via fermentation [34].

- Ethyl Lactate: Produced from corn and soybeans by fermenting biomass and reacting two fermentation products, ethanol and lactic acid [34].

- Terpenes (e.g., D-limonene): Sourced from agricultural waste, particularly from citrus processing, often via steam distillation [34].

Table 1: Physicochemical and Environmental Properties of Featured Bio-based Solvents

| Solvent | Flash Point (°C) | Kauri-Butanol (Kb) Value | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | ~13 [35] | N/A | Low toxicity, readily biodegradable, preferred green solvent [35] [33] | Volatile, flammable [35] |

| Ethyl Lactate | 133 [36] | 750 [36] | High solvent power, non-toxic, non-HAZMAT, biodegradable [34] [36] | Lower volatility may require GC inlet optimization [34] |

| D-Limonene | ~48 | N/A | Effective n-hexane substitute, renewable source (citrus) [34] | Highly toxic to aquatic organisms [34] |

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Analytical Applications

| Solvent | Application | Performance Summary | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Vortex-assisted MSPD of biocides from fish tissue | Extraction efficiency >96%; selected for low toxicity and beneficial physicochemical properties. | [34] |

| Ethyl Lactate | Pressurized Liquid Extraction of thymol from thyme | Showed good performance as a biosolvent for extracting this bioactive compound. | [34] |

| D-Limonene | DLLME for β-cyclodextrin determination | 200 µL used as extraction solvent; provided acceptable LOD and linear range. | [34] |

| Ethyl Acetate | Extraction of fatty acids from salmon tissue | Slightly better efficiency than 2-MeTHF, D-limonene, ethanol, and other biosolvents. | [34] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Dispersive Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (DLLME) using D-Limonene

This method is used for the pre-concentration of β-cyclodextrin prior to spectrophotometric determination [34].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the aqueous sample solution containing the target analyte (β-cyclodextrin).

- Complex Formation: Add a bioreagent like β-carotene (obtained from carrots) to form a colored complex with the analyte [34].

- Microextraction:

- Use a microsyringe to rapidly inject a mixture containing 1 mL of acetone (disperser solvent) and 200 µL of D-limonene (extraction solvent) into the sample solution [34].

- Gently shake the solution. A cloudy solution forms, consisting of fine droplets of D-limonene dispersed throughout the aqueous sample.

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the cloudy solution for a short period (e.g., 5 minutes) to separate the organic and aqueous phases. The dense D-limonene phase will settle at the bottom of the tube.

- Analysis: Carefully remove the aqueous layer. The enriched analyte in the D-limonene phase can be analyzed directly via spectrophotometry.

Protocol 2: Vortex-Assisted Matrix Solid-Phase Dispersion (MSPD) using Ethanol

This method is for extracting biocides from complex solid samples like fish tissue [34].

- Sample Homogenization: Accurately weigh the fish tissue sample (e.g., 0.5 g) and place it in a mortar.

- Blending with Sorbent: Add an appropriate solid support sorbent (e.g., silica gel, C18) to the tissue in a 1:1 to 1:4 ratio (sample/sorbent). Gently blend them together using a pestle to obtain a homogeneous, dry mixture.

- Packing: Transfer the homogeneous mixture to a solid-phase extraction cartridge or column, plugging the bottom with a frit.

- Elution: Add a volume of ethanol (the selected bio-based solvent) to the column. Cap the column and place it on a vortexer. Vortex the column for a set time (e.g., 1-2 minutes) to vigorously mix the solvent with the sample-sorbent blend, facilitating elution of the analytes.

- Collection: Collect the eluate containing the target biocides. The extract can be directly analyzed or concentrated further if needed.

Experimental Workflow and Solvent Selection Diagrams

Bio-based Solvent Selection Workflow

Vortex-Assisted MSPD Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Bio-based Solvent Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ethyl Lactate | Extraction of phytochemicals; general green replacement for chlorinated solvents. | Biodegradable, nontoxic, high flash point (133°F). High Kb value (750) indicates powerful cleaning ability [34] [36]. |

| D-Limonene | Replacement for n-hexane in lipid/fat determination; substitute for toluene in Dean-Stark analysis. | Effective but highly toxic to aquatic organisms. Can be recycled and reused [34]. |

| Ethanol | Extraction solvent for biocides and bioactive compounds; component of greener chromatography mobile phases. | Preferred green solvent. Low toxicity but flammable. Biorenewable options are available [34] [35]. |

| 1-Butanol | Extraction of hydrophilic compounds (logP < 0.5) from aqueous solutions. | Recommended by Pfizer solvent guide. Can be produced via acetone-butanol-ethanol fermentation [33]. |

| Cyclopentyl Methyl Ether (CPME) | Extraction of hydrophobic compounds (logP > 2.6) from aqueous solutions. | Classified as a usable (yellow) solvent in the GSK solvent guide. Can be produced from lignocellulosic biomass [33]. |

| Ethyl Acetate | Versatile solvent for mid-polarity compounds; greener alternative to DCM in chromatography. | Can be synthesized by fermenting sugars. Considered a preferred green solvent [35] [33]. |

| Anhydrous Sodium Chloride | Used in sample preparation for GC-MS to salt-out analytes, improving partition into the organic solvent phase. | Common in liquid-liquid extraction protocols to enhance recovery [37]. |

Supercritical Fluids and Subcritical Water for Extraction

The drive to replace toxic organic solvents in spectroscopic and chromatographic analysis has accelerated the adoption of green extraction technologies, primarily Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE) and Subcritical Water Extraction (SWE). These methods leverage the unique properties of substances beyond their critical points (for SFE) or water at high temperatures and pressures below its critical point (for SWE) to achieve efficient, selective, and environmentally friendly extraction of bioactive compounds from natural products and industrial waste [38]. SFE, particularly using supercritical carbon dioxide (scCO₂), is renowned for its unparalleled purity and process efficiency, providing selective extraction while minimizing environmental impact and eliminating toxic solvent residues [39] [40]. SWE utilizes water's tunable physicochemical properties at elevated temperatures to dissolve a wide range of polar and non-polar compounds, offering a safe, economical, and highly sustainable alternative to conventional solvents [41] [38]. This technical support center provides detailed troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and experimental protocols to assist researchers in seamlessly integrating these technologies into their analytical workflows, supporting the broader thesis of replacing toxic solvents in spectroscopic analysis research.

Troubleshooting Guides

Supercritical Fluid Extraction (SFE)

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SFE Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield & Efficiency | Low extraction yield | - Temperature/pressure below optimal crossover point [42].- Inadequate static soak time.- Incorrect particle size of matrix. | - Above 6000 psi, increase temperature; below, decrease it [42].- Implement static/dynamic cycling (e.g., 10 min static, 10 min dynamic) [42].- Grind sample to increase surface area, but avoid excessive compaction. |

| Inconsistent yield between runs | - Fluctuations in CO₂ pressure or temperature.- Clogged flow paths or valves.- Variable sample moisture content. | - Verify system calibration for pressure and temperature sensors.- Perform routine system purges and check for obstructions.- Standardize sample pre-treatment (drying, grinding). | |

| System Operation | High energy consumption | - Continuous operation at high pressure.- Inefficient pump and heater operation. | - Utilize static/dynamic cycling to reduce CO₂ consumption by nearly half [42].- Invest in newer, modular systems designed for reduced power consumption [39]. |

| System pressure instability | - CO₂ supply issues (empty cylinder, dip tube issues).- Leaks in high-pressure fittings.- Faulty back-pressure regulator. | - Check CO₂ cylinder weight and replace if empty; ensure correct dip tube orientation.- Perform leak check with leak detection fluid on all fittings.- Inspect, clean, or service the back-pressure regulator. | |

| Chemical & Application | Difficulty extracting polar compounds | - Low polarity of pure scCO₂.- Inadequate solvent strength. | - Introduce a polar co-solvent (e.g., ethanol, methanol) as a modifier [40].- Consider switching to a subcritical water system for highly polar compounds [38]. |

| Carryover or cross-contamination | - Incomplete cleaning of extraction vessels and lines.- Trapped material in dead volumes. | - Implement thorough cleaning protocols between samples using appropriate solvents.- Purge system with clean scCO₂ and co-solvents between runs. |

Subcritical Water Extraction (SWE)

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common SWE Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Issue | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yield & Efficiency | Low polyphenolic yield or antioxidant activity | - Suboptimal extraction temperature.- Excessive extraction time degrading thermolabile compounds. | - Optimize temperature gradient (e.g., 170°C often optimal for phenolics) [41] [43].- Shorten extraction time (e.g., 5-15 min at high temperatures) [43]. |

| Incomplete extraction | - Sample particle size too large.- Low pressure, reducing water penetration. | - Reduce and standardize particle size of the biomass.- Ensure pressure is sufficiently high to maintain water in liquid state. | |

| System Operation | Formation of degradation products | - Temperature too high for target compounds.- Prolonged exposure to high heat. | - For thermolabile compounds, use lower temperatures (e.g., 110-150°C) [41].- Monitor for HMF formation, a marker of degradation at >150°C [38]. |

| Corrosion or scaling in the system | - Use of untreated water with high mineral content.- Low pH of extracts. | - Use high-purity, deionized water.- Flush system regularly and inspect wetted components for wear. | |

| Chemical & Application | Poor selectivity | - Dielectric constant of water not tuned for target compounds. | - Precisely control temperature to manipulate water's polarity for specific compound classes [41] [38]. |

| Cellulose purification challenges from residue | - Inefficient bleaching step after SWE.- High lignin content in residue. | - For residues after SWE, apply hydrogen peroxide bleaching (e.g., 1-4 cycles at pH 12, 8% H₂O₂) [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary economic and technical challenges of implementing SFE, and how can they be mitigated? The main challenges are high capital investment for equipment and significant energy consumption during operation [40]. Mitigation strategies include adopting collaborative leasing models, exploring service-based contracts to offset upfront costs, and utilizing static/dynamic cycling to reduce CO₂ consumption by nearly half, thereby lowering operational expenses [39] [42]. Technological advancements are also producing more modular, automated, and energy-efficient systems, improving long-term cost-effectiveness [39].

Q2: How does subcritical water change its properties to extract diverse compounds? Under subcritical conditions, increasing temperature significantly reduces water's dielectric constant (a measure of polarity), surface tension, and viscosity. This transforms water from a highly polar solvent at room temperature into a medium capable of dissolving moderately polar and non-polar compounds, such as polyphenols and flavonoids [41] [38]. This tunability allows for selective extraction by simply adjusting the temperature.

Q3: My SFE yield for a new plant matrix is low. What parameters should I optimize first? Begin by mapping a pressure-temperature profile to identify the "crossover point," where the effect of temperature on yield reverses. Above this pressure, yield increases with temperature; below it, yield decreases with temperature [42]. Furthermore, optimize particle size and moisture content of your plant matrix, and consider the addition of a polar co-solvent like ethanol if your target compounds are polar [40].

Q4: Are extracts from SWE safe for pharmaceutical or food applications? Recent toxicological studies indicate a high degree of safety. Subcritical water extracts from sources like Rosa damascena and Rosa alba have shown no significant cytotoxicity in a range of concentrations across various test systems, including human lymphocytes, and demonstrate low genotoxicity, making them suitable for medical, food, and cosmetic industries [44]. The absence of toxic solvent residues is a key advantage.

Q5: What are the key trends driving the adoption of these green extraction technologies? Key drivers include: 1) Stringent regulatory frameworks favoring green chemistry and restricting organic solvents [39] [40]; 2) Consumer demand for clean-label, natural products without solvent residues [40]; 3) Technological convergence with AI and digitalization for real-time monitoring and process optimization [39] [45]; and 4) Industry 4.0 integration, enabling remote control and predictive maintenance [39].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed SWE Protocol for Bioactive Compounds from Brewer's Spent Grain (BSG)

This protocol is adapted from a study published in Molecules 2024, which demonstrates an integral fractionation of BSG into phenolic-rich extracts and cellulosic fibers [41].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Obtain dried BSG.

- Defatting: Perform a preliminary defatting step using a suitable solvent (e.g., hexane in a Soxhlet) or supercritical CO₂. This yields approximately 8% oil from the dried bagasse [41].

- Dry the defatted BSG (DB) to a constant weight.

2. Subcritical Water Extraction:

- Equipment Setup: Use a pressurized liquid extraction system equipped with an extraction cell, an oven for temperature control, a high-pressure pump, a pressure regulator, and a collection vial.

- Loading: Pack the extraction cell tightly with the defatted BSG.

- Extraction Parameters:

- Solvent: High-purity deionized water.

- Temperature: Test a range from 110°C to 170°C. The study found extracts at 170°C were richer in phenolics [41].

- Pressure: Maintain pressure sufficiently high (typically 10-50 bar) to keep water in the liquid state throughout the extraction.

- Static Time: Conduct extraction in static mode for a predetermined time.

- Cycles: 1-2 cycles.

- Collection: Upon completion, slowly release the pressure and collect the aqueous extract.

3. Post-Extraction Processing:

- Extract Concentration: Lyophilize (freeze-dry) the collected aqueous extract to obtain a solid powder for analysis.

- Residue Processing: The insoluble residue from the SWE step can be subjected to a bleaching treatment for cellulose purification using hydrogen peroxide (e.g., four 1-hour cycles at pH 12 with 8% H₂O₂) [41].

4. Analysis:

- Yield: Calculate the mass yield of the dry extract.

- Total Phenolic Content (TPC): Use the Folin-Ciocalteu method, expressing results as mg Gallic Acid Equivalents (GAE) per gram of dry extract. (e.g., 24 mg GAE/g was reported for 170°C extract) [41].

- Antioxidant Activity: Evaluate using DPPH assay (e.g., 71 mg DB·mg⁻¹ DPPH for 170°C extract) [41] or ABTS/FRAP assays [43].

- Antibacterial Assay: Test against model organisms like L. innocua and E. coli [41].

General SFE Protocol for Bioactive Lipids and Oils

This protocol synthesizes common practices for SFE, as illustrated in application notes for peanut oil extraction [42].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Grind the source material (e.g., peanuts, seeds, plant leaves) to a uniform, medium-fine particle size.

- Ensure the sample is dry, as moisture can interfere with scCO₂ extraction.

2. Supercritical CO₂ Extraction:

- Equipment Setup: Use a SFE system comprising a CO₂ cylinder, a cooled pump, a heated extraction vessel, pressure control valves, and a collection vessel.

- Loading: Fill the extraction vessel with the prepared sample.

- Extraction Parameters:

- Solvent: Food-grade or high-purity CO₂.

- Temperature: 40°C to 80°C [42].

- Pressure: 5000 to 7000 psi [42].

- Mode: Use static/dynamic cycling. A typical cycle is a 10-minute static soak followed by a 10-minute dynamic flow. A total extraction time of 3 hours has been used effectively [42].

- Co-solvent (Optional): If extracting polar compounds, add 5-15% of a co-solvent like ethanol via a secondary pump.

3. Collection:

- The extract is collected in a vessel by reducing the pressure, causing the CO₂ to gasify and leave the solute behind. The collection chamber may be cooled to improve recovery.

4. Analysis:

- Yield: Determine gravimetrically.

- Crossover Pressure: Identify the pressure (e.g., ~6000 psi) where the temperature-yield relationship inverts [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for SFE and SWE

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Supercritical CO₂ | Primary solvent for SFE; non-toxic, non-flammable, tunable solvent strength. | Must be high-purity (≥ 99.9%). Its critical point (31.1°C, 73.8 bar) makes it ideal for heat-sensitive compounds [40]. |

| Co-solvents/Modifiers | Enhance solubility of polar compounds in scCO₂. | Ethanol, Methanol. Ethanol is preferred for food/pharma applications (GRAS status). Typically added at 1-15% (v/v) [40]. |

| Subcritical Water | Solvent for SWE; polarity is tunable with temperature. | Must be high-purity, deionized water. Its dielectric constant drops from ~80 at 25°C to ~30 at 250°C, similar to organic solvents [41] [38]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Bleaching agent for purifying cellulose from SWE residues. | Used in concentrations around 8% for bleaching residues after SWE to obtain cellulose fibers [41]. |

| Analytical Standards | For quantification and identification of extracted compounds via HPLC, LC-MS. | Gallic Acid (for TPC), Quercetin (for flavonoids), Catechin, various phenolic acid standards. Essential for calibrating spectroscopic and chromatographic analyses [41] [43] [44]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | For clean-up and pre-concentration of extracts before spectroscopic analysis. | C18 cartridges are commonly used to desalt and concentrate polar bioactive compounds from aqueous SWE extracts. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Are ionic liquids (ILs) inherently "green" or environmentally friendly solvents? No, ionic liquids are not inherently green. While they possess properties like negligible volatility that reduce air pollution risks, their ecotoxicity and biodegradability vary significantly. Some ILs are toxic, particularly in aquatic environments, and fairly resistant to biodegradation. A comprehensive assessment is required to determine the greenness of a specific IL for an application [46].

Q2: What are the common physical properties of ILs that differ from conventional molecular solvents? ILs exhibit unique properties including negligible vapor pressure, high thermal stability, high ionic conductivity, and non-flammability. Their viscosity is often higher, and they have a large electrochemical window. These properties are tunable based on cation-anion combinations [47].

Q3: How can I select an IL with lower environmental impact? Selection should be based on a defined "greenness" framework, considering metrics like toxicity (e.g., to aquatic organisms, mammalian cell lines), biodegradability potential, and the presence of hazardous functional groups. Computational modeling (QSAR) and life cycle assessment are tools used for this evaluation [46] [48].

Q4: My IL-based spectroscopic analysis shows unexpected results. Could water absorption be the cause? Yes. Many ILs are hygroscopic. Absorbed water can significantly alter physicochemical properties, including viscosity, conductivity, and solvation environment, which can interfere with spectroscopic measurements. It is crucial to use thoroughly dried ILs under a controlled atmosphere (e.g., in a glovebox) for sensitive applications [47] [49].

Q5: Can ionic liquids be recycled after use in separations or reactions? Yes, their non-volatile nature facilitates recycling. Techniques such as liquid-liquid extraction, distillation (for protic ILs), and advanced oxidation processes have been explored for IL recovery and reuse, improving the sustainability of processes [46].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Properties | Unexpectedly high viscosity | Large ion size, strong intermolecular forces, water content. | Select ions with shorter alkyl chains; ensure thorough drying; moderate heating to reduce viscosity. |

| Low electrical conductivity | High viscosity, ion pairing/aggregation. | Choose ions that promote low viscosity (e.g., [TFSI]⁻); reduce ion pairing by selecting weakly coordinating ions [50] [49]. | |

| Synthesis & Purity | Impurities affecting performance | Incomplete synthesis, leftover halides from metathesis, water absorption. | Employ rigorous purification (e.g., washing, adsorption, prolonged drying under vacuum); characterize with elemental analysis or ion chromatography [50]. |

| Environmental & Safety | High toxicity or poor biodegradability | Use of hydrolytically unstable anions (e.g., [PF₆]⁻), long alkyl chains on cations. | Design ILs with readily biodegradable components (e.g., esters, sugars); use stable anions like [TFSI]⁻; consult ecotoxicity databases before selection [46]. |

| Application in Spectroscopy | Poor solvation of target analyte | Mismatch between IL polarity/coordination strength and analyte solubility. | Tune IL by selecting anions/cations with appropriate hydrogen bonding capacity (e.g., chloride for H-bond basicity) or compatible polar/apolar domains [49]. |

Table 1: Key Property Ranges for Common Ionic Liquid Types (Imidazolium-based examples)

| Property | Typical Range for ILs | Comparison: Molecular Solvent (Water) | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point | < 100 °C | 0 °C (water) | Ion size, symmetry, charge delocalization, intermolecular forces [47]. |

| Viscosity | 10 - 500 cP (at 25°C) | ~0.89 cP (water at 25°C) | Alkyl chain length, anion type, temperature, presence of water/impurities [47]. |

| Ionic Conductivity | 0.1 - 10 mS/cm | Very low (pure water) | Viscosity, ion mobility, degree of dissociation (ion pairing) [47]. |

| Vapor Pressure | Negligible at room temp | ~24 mmHg (water at 25°C) | Ionic nature and strong Coulombic forces [47]. |