Green Chemistry in the Lab: Sustainable Waste Reduction Strategies for Modern Analytical Methods

This article provides a comprehensive framework for integrating sustainability into analytical chemistry, specifically targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Green Chemistry in the Lab: Sustainable Waste Reduction Strategies for Modern Analytical Methods

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for integrating sustainability into analytical chemistry, specifically targeting researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC), contrasting them with traditional linear models. The content delivers actionable methodologies for minimizing solvent and energy consumption through automation, miniaturization, and process integration. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, including the 'rebound effect,' and offers optimization techniques. Finally, it guides the validation and comparative assessment of methods using established greenness metrics like AGREE and AGREEprep, empowering scientists to make environmentally conscious choices without compromising data quality.

Rethinking Analytical Chemistry: From Linear Waste to Sustainable Cycles

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary environmental problem with traditional analytical methods? Traditional analytical chemistry largely operates under a linear "take-make-dispose" model, which creates unsustainable environmental pressures through resource-intensive processes, energy consumption, and significant waste generation [1]. Many official standard methods rely on outdated, resource-intensive techniques, with 67% of assessed CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeia standard methods scoring below 0.2 on the AGREEprep greenness metric (where 1 is the highest score) [1].

FAQ 2: How is "sustainability" different from "circularity" in analytical chemistry? Sustainability is a broader concept balancing three pillars: economic, social, and environmental. Circularity is more focused, aiming primarily to minimize waste and keep materials in use for as long as possible. While interconnected, they do not always align; a circular practice might not fully address social or economic sustainability dimensions [1].

FAQ 3: What is the "rebound effect" in Green Analytical Chemistry? The rebound effect occurs when environmental benefits of a new, more efficient method are offset by unintended consequences. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might lead laboratories to perform significantly more analyses because it is cheap and accessible, ultimately increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [1].

FAQ 4: What are the main barriers to adopting greener analytical methods? Key barriers include a strong focus on product performance (like speed and sensitivity) over sustainability factors, and a coordination failure within the field. The traditional and conservative nature of analytical chemistry limits collaboration between key players like industry and academia, which is essential for transitioning to circular processes like resource recovery [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High Solvent and Chemical Waste

Symptoms: Your lab generates large volumes of hazardous solvent waste; methods require large sample sizes and high reagent volumes.

Solution: Implement Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles.

| Solution Strategy | Methodology | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Accelerate Mass Transfer | Apply assisting fields (e.g., ultrasound, microwaves) to enhance extraction efficiency and speed [1]. | Significantly reduces energy consumption compared to traditional heating (e.g., Soxhlet) [1]. |

| Parallel Processing | Use miniaturized systems to treat several samples simultaneously [1]. | Increases throughput and reduces energy consumed per sample [1]. |

| Automation | Implement automated sample preparation systems [1]. | Saves time, lowers reagent/solvent consumption, reduces waste, and minimizes operator exposure [1]. |

| Process Integration | Integrate multiple preparation steps into a single, continuous workflow [1]. | Cuts down on resource use and waste production while simplifying operations [1]. |

Problem 2: High Energy Consumption in Sample Preparation

Symptoms: Methods rely on energy-intensive processes like prolonged heating or cooling.

Solution: Redesign workflows for energy efficiency.

Steps:

- Evaluate Alternatives: Replace traditional Soxhlet extraction with modern techniques like pressurized liquid extraction or microwave-assisted extraction, which offer faster heating and reduced process times.

- Embrace Miniaturization: Scale down method volumes. Smaller volumes require less energy to heat, cool, or mix.

- Schedule Strategically: Batch process samples to maximize instrument uptime and avoid the energy costs of repeated start-up and shut-down cycles.

- Conduct an Energy Audit: Monitor energy usage of specific instruments to identify the most significant sources of consumption and prioritize improvements.

Quantitative Data on Method Greenness

The following table summarizes data from a greenness assessment of official standard methods, illustrating the scale of the problem.

Table 1: Greenness Scores of Official Standard Methods (CEN, ISO, Pharmacopoeia) [1]

| Standard Body | Number of Methods & Sub-Methods Assessed | Average AGREEprep Score (0-1 Scale) | Percentage of Methods Scoring Below 0.2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEN, ISO, Pharmacopoeia | 332 sub-method variations from 174 standard methods | Low (Specific average not provided) | 67% |

Experimental Protocols for Green Sample Preparation

Protocol: An Integrated and Miniaturized Approach for Liquid-Liquid Extraction

Objective: To reduce solvent consumption, waste generation, and energy use compared to traditional liquid-liquid extraction.

Principle: This method combines sample miniaturization and process integration to streamline workflow and minimize resource use [1].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

Item Function Low-Density Solvent Acts as the extracting phase. Micro-Syringe For precise handling of µL-volume samples and solvents. Vial with Conical Bottom Facilitates the collection of the solvent phase after extraction. Vortex Mixer Provides rapid mixing to accelerate mass transfer without significant heat input [1].

Procedure:

- Sample Introduction: Place a precisely measured µL-volume aqueous sample into a conical vial.

- Solvent Addition: Add a µL-volume of a low-density, water-immiscible organic solvent.

- Rapid Extraction: Securely cap the vial and place it on a vortex mixer. Agitate vigorously for a predetermined, short time (e.g., 1-2 minutes) to achieve efficient extraction [1].

- Phase Separation: Allow the vial to stand briefly for phase separation. Due to the conical design and small volumes, the organic solvent droplet will coalesce at the vial's tip.

- Analysis: Directly withdraw the solvent micro-droplet using a micro-syringe for instrumental analysis.

Workflow Visualizations

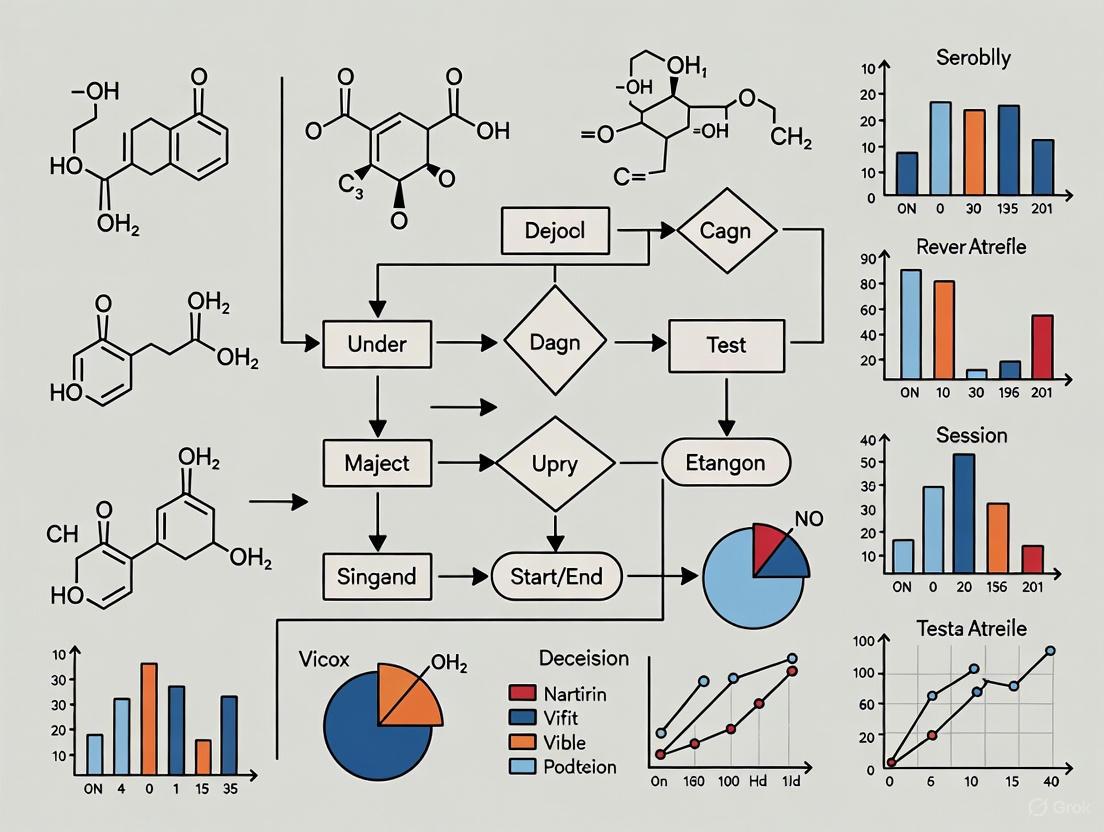

Diagram 1: Linear vs Circular Chemistry

Diagram 2: Green Sample Prep Workflow

Conceptual Framework: GAC vs. CAC

The following table outlines the core philosophical and practical differences between Green and Circular Analytical Chemistry.

| Aspect | Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) | Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Reduce environmental and health impacts of analytical processes [2]. | Transition from a linear "take-make-dispose" model to a waste-free, resource-efficient sector [1]. |

| Core Philosophy | Minimization: Prevent waste, reduce energy use, and avoid hazardous substances [2]. | Circulation: Keep materials in use for as long as possible through recycling, recovery, and reuse [1]. |

| Key Focus | The environmental footprint of the analytical method itself [3]. | The entire lifecycle of materials and resources within the analytical system [1]. |

| Sustainability Model | Primarily addresses the environmental pillar of sustainability [2]. | Integrates strong environmental and economic considerations; social aspect is less pronounced [1]. |

| Typical Strategies | Using green solvents, miniaturization, energy-efficient techniques (e.g., microwave-assisted extraction) [2] [4]. | Designing methods for resource recovery, recycling solvents, and collaboration among stakeholders to close material loops [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can a method be circular without being green? While the concepts are deeply interconnected, they are not identical. A process could theoretically be circular by recycling a highly toxic solvent, but it would not be considered green due to the inherent hazard of the substance. True sustainability in analytical chemistry seeks to achieve both goals simultaneously: using safe, benign materials and ensuring they are kept in circulation [1].

Q2: What is the "rebound effect" in Green Analytical Chemistry? The rebound effect refers to an unintended consequence where the environmental benefits of a greener method are offset by its increased use. For example, a novel, low-cost microextraction method might use minimal solvents per analysis. However, because it is so cheap and accessible, laboratories might perform significantly more analyses, ultimately increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated. Mitigation strategies include optimizing testing protocols and fostering a mindful laboratory culture [1].

Q3: How do I evaluate the greenness of my analytical method? Multiple tools have been developed to assess the environmental impact of analytical methods. These include AGREEprep (for sample preparation), GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index), and the Analytical GREEnness metric (AGREE). These tools provide scores based on criteria such as energy consumption, waste generation, and toxicity of reagents [5]. A recent assessment of 174 standard methods using AGREEprep revealed that 67% scored poorly, highlighting the urgent need for method modernization [1].

Q4: What are the main barriers to adopting Circular Analytical Chemistry? Two significant challenges hinder the transition to CAC:

- Lack of Direction: A strong focus remains on analytical performance (speed, sensitivity) with less emphasis on the lifecycle sustainability of materials [1].

- Coordination Failure: CAC requires collaboration among all stakeholders—manufacturers, researchers, routine labs, and policymakers. Analytical chemistry is a traditional field with limited cooperation between industry and academia, making it difficult to establish circular processes like solvent recycling at scale [1].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: High Solvent Waste in HPLC/UHPLC

Issue: Traditional reversed-phase LC methods rely heavily on acetonitrile and methanol, generating large volumes of toxic waste [3].

Solution Guide:

| Step | Action | Considerations & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Substitute the Solvent | Replace classical solvents with greener alternatives. For example, ethanol is a readily available, less toxic, and bio-based option. Cyrene (dihydrolevoglucosenone) is another bio-based solvent with promising applications in chromatography [3]. |

| 2 | Reduce Consumption | Switch to columns packed with smaller particles (e.g., sub-2 µm) or use core–shell technology. These columns offer higher efficiency, allowing for the use of shorter columns with smaller diameters, which reduces mobile phase consumption and analysis time [3]. |

| 3 | Recycle and Reuse | Implement an on-site solvent recovery system to distill and purify waste mobile phase for reuse. This is a core CAC practice that directly addresses the linear "dispose" model [1]. |

Problem: Energy-Intensive Sample Preparation

Issue: Traditional techniques like Soxhlet extraction are time-consuming and require large amounts of energy [2] [1].

Solution Guide:

| Step | Action | Considerations & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Apply Alternative Energy | Use ultrasound (sonication) or microwave-assisted extraction. These methods enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer, consuming significantly less energy than traditional heating [2] [1]. |

| 2 | Miniaturize and Automate | Adopt micro-extraction techniques (e.g., Solid-Phase Microextraction - SPME). This minimizes sample and solvent volumes. Automating this process further improves throughput, reduces reagent use, and lowers operator exposure risks [1] [4]. |

| 3 | Integrate Workflow | Combine multiple sample preparation steps into a single, continuous workflow. This simplifies operations and cuts down on resource use and waste production [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Waste Reduction

Protocol: Transferring a Classical HPLC Method to a Greener Solvent System

Objective: To reduce the environmental impact and toxicity of an existing HPLC method by substituting the organic modifier in the mobile phase.

Materials:

- HPLC/UHPLC system

- Classic method using acetonitrile or methanol

- Short (e.g., 50 mm) core–shell or sub-2 µm particle column

- Candidate green solvent (e.g., ethanol, acetone)

Methodology:

- Select a Green Solvent: Consult solvent selection guides (e.g., CHEM21, ACS GCI) to identify a less toxic, biodegradable alternative with similar elutropic strength to the original solvent [3].

- Adjust Mobile Phase Composition: Due to differences in solvent strength, the percentage of the new organic modifier will likely need adjustment. Use elutropic strength tables or software to estimate the starting composition.

- Optimize Chromatographic Conditions: The new solvent may affect selectivity, retention time, and backpressure. Systematically adjust the gradient program, temperature, and flow rate to achieve baseline separation of all analytes in a comparable or shorter runtime.

- Validate the Method: Ensure the new green method meets all validation parameters (precision, accuracy, linearity, LOD, LOQ) as required for its application.

Protocol: Implementing In-Situ Analysis to Eliminate Solvent Use

Objective: To completely avoid solvent consumption and waste generation by using a direct, non-destructive measurement technique.

Materials:

- Portable spectrometer (e.g., NIR, Raman) or sensor

- Appropriate software for data acquisition and modeling

Methodology:

- Feasibility Assessment: Determine if the analyte of interest has a measurable signal (e.g., a unique spectral fingerprint) that can be detected directly in the sample matrix without extensive preparation.

- Calibration Model Development: Collect a representative set of samples and analyze them using both the portable instrument and a reference laboratory method. Use chemometric tools to build a calibration model that correlates the in-situ signal with the reference concentration [2].

- Method Deployment: Use the calibrated model to perform direct, in-situ measurements on new samples. This approach is ideal for real-time, on-site monitoring and aligns perfectly with the GAC principle of direct analysis [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and concepts for implementing GAC and CAC principles.

| Reagent/Solution | Function in GAC/CAC | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents (e.g., Bio-based ethanol, Cyrene, Ionic Liquids) [2] [3] | Replace hazardous volatile organic compounds (VOCs) like acetonitrile and n-hexane in extractions and mobile phases. | Reversed-phase liquid chromatography, liquid-liquid extraction. |

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) [4] | Serve as biodegradable, non-toxic solvents for extracting a wide range of analytes. | Extraction of bioactive compounds from plant materials. |

| Switchable Solvents (SSs) [4] | Solvents that can change their hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity in response to a trigger (e.g., CO₂). Allows for easy recovery and reuse of the solvent. | Recycling and reusing solvents in liquid-liquid extraction processes. |

| Supramolecular Solvents (SUPRAS) [4] | Aqueous solvents made up of nanostructures; are considered green due to their water-based nature and ability to solubilize diverse compounds. | Extraction of organic contaminants from water and soil samples. |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

GAC and CAC Core Objectives

Green Sample Preparation Implementation

Conceptual FAQ: Core Principles

What is the fundamental difference between weak and strong sustainability?

Weak and strong sustainability are two opposing paradigms for achieving sustainable development. The core difference lies in how they view the substitutability of natural capital (e.g., forests, water, minerals) with human-made capital (e.g., technology, infrastructure).

- Weak Sustainability assumes that natural capital and human-made capital are largely substitutable. It posits that economic growth and technological progress can compensate for the depletion of natural resources and environmental damage. This model focuses on maintaining the total aggregate capital stock, allowing for the consumption of natural resources as long as human-made assets are built up in their place [1] [6].

- Strong Sustainability, in contrast, argues that natural capital is unique and provides essential functions that cannot be replaced by human-made capital. It recognizes ecological limits, planetary boundaries, and the need to protect and regenerate natural systems. This model requires that the stock of natural capital itself must not decline over time [1] [7].

How do these models relate to circularity in a laboratory context?

In analytical chemistry, sustainability is often confused with circularity, but they are not the same. Circularity is primarily focused on the environmental dimension, aiming to minimize waste and keep materials in use for as long as possible [1]. While this is a crucial step, it often integrates strong economic considerations but may not fully address the social pillar of sustainability.

- Weak Sustainability in the Lab might involve using recycled solvents but not reducing the overall number of energy-intensive analyses performed.

- Strong Sustainability in the Lab would involve a systemic shift, questioning the necessity of each analysis, prioritizing methods that actively restore natural systems, and ensuring social well-being alongside environmental and economic goals [1]. Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) is a framework that serves as a stepping stone from the linear "take-make-dispose" model toward these broader, strong sustainability goals [1].

What are the main barriers to adopting a strong sustainability model in research?

Transitioning to a strong sustainability model faces several significant challenges:

- Linear Mindset and Performance Focus: A persistent strong focus on analytical performance (speed, sensitivity) often overshadows sustainability factors like resource efficiency and waste reduction [1].

- Coordination Failure: The field of analytical chemistry is traditional and conservative, with limited cooperation between industry, academia, and policymakers. Strong sustainability requires all stakeholders to collaborate and embrace new principles [1].

- Outdated Standards: Many official standard methods (from CEN, ISO, Pharmacopoeias) rely on resource-intensive, outdated techniques. One study found that 67% of standard methods scored very low on greenness metrics, creating a regulatory barrier to adopting greener alternatives [1].

- The Rebound Effect: Green innovations can sometimes lead to unintended consequences that offset their benefits. For example, a new, low-cost microextraction method might lead laboratories to perform significantly more analyses, increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Scenarios

Problem: My standard operating procedure (SOP) is resource-intensive and scores poorly on green metrics, but is required for compliance.

- Diagnosis: This is a classic conflict between established, often "weak sustainability," practices and the goals of strong sustainability. The root cause is often outdated regulatory frameworks.

- Solution:

- Investigate Alternatives: Conduct a literature review to identify modern, mature analytical methods that achieve the same goal with less environmental impact.

- Quantify the Difference: Use a greenness assessment metric, such as the AGREEprep tool, to quantitatively compare the environmental performance of the current SOP against the proposed alternative [1].

- Engage Regulators: Compile the data on performance parity and improved greenness scores and present it to the relevant regulatory agency or standards committee. Advocate for updating the standard methods to include contemporary, greener techniques [1].

Problem: After automating our sample preparation to save time and solvents, the total number of analyses (and potential waste) has increased.

- Diagnosis: This is a "rebound effect," where efficiency gains lead to increased overall consumption, undermining sustainability goals [1].

- Solution:

- Optimize Testing Protocols: Implement smart, predictive analytics to determine when tests are truly necessary and avoid redundant analyses [1].

- Establish Sustainability Checkpoints: Update standard operating procedures to include mandatory sustainability reviews before initiating large batches of automated analyses.

- Cultivate a Mindful Culture: Train laboratory personnel on the implications of the rebound effect. Encourage a lab culture where resource consumption is actively monitored and questioned [1].

Problem: I want to implement a more sustainable method, but I lack clear direction and face resistance from a traditional research group.

- Diagnosis: This is a coordination and knowledge gap challenge, reflecting the systemic barriers to transitioning to a circular or strong sustainability framework [1].

- Solution:

- Adopt a Framework: Propose adopting a structured framework like the Twelve Principles of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) to provide a clear, shared direction for the team [1].

- Build a Business Case: Frame the transition in terms of long-term economic stability and risk mitigation (e.g., reducing dependency on scarce solvents), aligning with the "triple bottom line" of sustainability [1].

- Pilot and Showcase: Start with a small-scale pilot project to demonstrate the new method's viability, showcasing benefits like reduced costs for hazardous waste disposal or improved workplace safety.

Sustainability Model Comparison Table

Table 1: A comparison of Weak and Strong Sustainability paradigms applied to analytical chemistry.

| Feature | Weak Sustainability Model | Strong Sustainability Model |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Natural and human-made capital are substitutable [6]. | Natural capital is non-substitutable and must be preserved [7]. |

| Primary Goal | Maintain total capital stock; economic growth can compensate for environmental damage [1]. | Operate within ecological limits; restore and regenerate natural capital [1]. |

| View of Technology | Techno-optimism; technology will solve resource scarcity and pollution [1]. | Technology is a tool that must be used within planetary boundaries. |

| Lab Practice Analogy | Using a more energy-efficient HPLC that runs 3x more samples. | Redesigning the analytical workflow to eliminate unnecessary steps and non-essential analyses. |

| Waste Management | Focus on end-of-pipe solutions and recycling (downcycling). | Focus on waste prevention, reuse, and systems designed for zero waste. |

| Role of Circularity | Often conflated with the end goal of sustainability [1]. | Seen as a stepping stone and operational strategy toward the broader goal of strong sustainability [1]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Practice Solutions

Table 2: Key solutions for transitioning to more sustainable laboratory practices.

| Tool or Practice | Function & Role in Sustainable Research |

|---|---|

| Greenness Assessment Metrics (e.g., AGREEprep) | Software tools that provide a quantitative score of a method's environmental performance, allowing for objective comparison and justification of greener alternatives [1]. |

| Green Sample Preparation (GSP) | A framework focusing on minimizing or eliminating solvents, reducing energy consumption, and integrating steps to streamline workflows and cut resource use [1]. |

| Automation & Parallel Processing | Automated systems save time, lower reagent consumption, reduce waste, and minimize operator exposure to hazards. Parallel processing increases throughput and reduces energy consumed per sample [1]. |

| Ultrasound/Microwave-Assisted Extraction | These techniques use assisting fields to enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer while consuming significantly less energy than traditional methods like Soxhlet extraction [1]. |

| Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) Framework | A set of 12 principles that provide a clear, actionable roadmap for transitioning from a linear "take-make-dispose" model to a circular, and more sustainable, operational model [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Adapting a Method Using Strong Sustainability Principles

Aim: To redesign a traditional liquid-liquid extraction (LLE) method to align with the principles of strong sustainability by minimizing consumables, energy use, and waste generation.

Methodology:

Scoping and Necessity Assessment:

- Action: Before any lab work, critically assess the analytical question. Determine if the analysis is essential or if the goal can be met with existing data or an alternative, less resource-intensive technique.

- Strong Sustainability Rationale: This step addresses the root cause of waste by preventing unnecessary experiments, aligning with the "prevention" principle of strong sustainability.

Solvent and Method Selection:

- Action: Replace toxic, hazardous solvents (e.g., chlorinated, aromatic) with safer, bio-based alternatives where possible. Transition from a macro-scale LLE to a miniaturized method, such as vortex-assisted liquid-liquid microextraction (VALLME).

- Rationale: This directly reduces the intrinsic hazard and volume of chemicals used (preserving natural capital) and minimizes the waste stream [1].

Process Optimization:

- Action: Apply energy-efficient assisting fields like ultrasound or vortex mixing to accelerate the extraction process instead of relying on heating or prolonged shaking.

- Rationale: This significantly reduces the energy consumption of the method, lowering its carbon footprint and operational cost [1].

Integration and Automation:

- Action: Integrate the sample preparation step directly with the analytical instrument (e.g., online with HPLC/GC) or automate it using a robotic platform.

- Rationale: Integration minimizes sample transfer losses and solvent evaporation. Automation enhances precision, reduces human error, and allows for more consistent application of the optimized method, while also improving technician safety [1].

The workflow for this protocol transitions from a linear, resource-intensive process to a circular, efficiency-focused one, as visualized below.

Analytical chemistry is undergoing a paradigm shift to align with global sustainability goals. Traditional analytical methods, while ensuring precision and accuracy, often rely on resource-intensive processes that generate significant chemical waste and consume substantial energy. This technical support center provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with practical guidance for assessing and improving the environmental footprint of their analytical methods, particularly those derived from standard organizations like CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias. Within the broader context of waste reduction strategies for analytical methods research, this resource addresses the urgent need to evaluate the "greenness" of established protocols and provides troubleshooting advice for transitioning to more sustainable laboratory practices without compromising analytical quality.

Recent research has revealed concerning findings about the environmental performance of standard methods. An assessment of 174 standard methods with sample preparation steps and their 332 sub-method variations from CEN, ISO, and Pharmacopoeias showed generally poor greenness performance, with 67% of methods scoring below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale (where 1 represents the highest possible score) [8] [1]. The problem varies by application area, as shown in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Greenness Performance of Standard Methods by Application Area

| Application Area | Methods Scoring Below 0.2 (AGREEprep) | Overall Greenness Status |

|---|---|---|

| Environmental Analysis (Organic Compounds) | 86% | Critically Poor |

| Food Analysis | 62% | Poor |

| Inorganic/Trace Metals Analysis | 62% | Poor |

| Pharmaceutical Analysis | 45% | Moderate to Poor |

FAQ: Understanding Greenness Assessment of Standard Methods

What does "greenness" mean in the context of analytical methods?

Greenness refers to the environmental impact of an analytical method across its entire lifecycle, assessed against the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) [9] [3]. These principles include minimizing waste generation, using safer solvents and reagents, reducing energy consumption, enabling direct analysis, and implementing real-time monitoring. A green method balances analytical performance (accuracy, precision, sensitivity) with reduced environmental footprint, considering factors like operator safety, waste disposal, and resource consumption [9].

Why do many official standard methods score poorly on greenness metrics?

Most official standard methods were developed decades ago when environmental considerations were not a priority in method development. They often rely on resource-intensive, outdated techniques that involve large solvent volumes, hazardous chemicals, energy-intensive processes, and multi-step procedures [8] [1]. The conservative nature of regulatory science and the extensive validation required for standard methods create significant inertia against updating them with more sustainable alternatives.

What is the difference between Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC)?

While often used interchangeably, these concepts have distinct meanings. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) primarily focuses on reducing environmental impact through the 12 principles of GAC. Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) extends this concept by applying circular economy principles specifically to analytical practices, emphasizing keeping materials in use through recycling, recovery, and waste minimization [1]. CAC integrates stronger economic considerations alongside environmental concerns, though the social aspect is less pronounced [1].

What is the "rebound effect" in Green Analytical Chemistry?

The rebound effect occurs when environmental benefits from greener methods are offset by unintended consequences. For example, a novel low-cost microextraction method that uses minimal solvents might lead laboratories to perform significantly more extractions than before, increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [1]. Similarly, automation can lead to over-testing simply because the technology allows it. Mitigation strategies include optimizing testing protocols, using predictive analytics, and implementing sustainability checkpoints in standard operating procedures [1].

Troubleshooting Guides: Common Challenges and Solutions

Challenge: Poor Greenness Scores in Standard Methods

Problem: Your laboratory uses official standard methods (CEN, ISO, Pharmacopoeia) that score poorly on greenness assessment tools, creating environmental concerns and increasing waste disposal costs.

Solutions:

- Apply Greenness Assessment Tools: Use established metrics like AGREEprep (specifically for sample preparation) or the broader AGREE metric to evaluate current methods and identify the worst-performing aspects [8] [9].

- Implement Modifications Where Possible: While maintaining method validity for regulatory purposes, introduce green improvements such as:

- Advocate for Method Updates: Engage with standards organizations to update methods by including contemporary, greener sample preparation and analysis techniques [8] [1].

Table 2: Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Tool Name | Main Focus | Output Type | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep | Sample Preparation | Pictogram + Score (0-1) | First dedicated sample prep metric; 10 assessment criteria [9] |

| AGREE | Entire Method (12 GAC Principles) | Radial Chart (0-1) | Holistic single-score metric; comprehensive evaluation [9] |

| GAPI | Entire Analytical Workflow | Color-coded Pictogram | Easy visualization of environmental impact across all stages [9] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Method Environmental Impact | Score (100 = Ideal) | Penalty-point system based on solvent toxicity, energy, waste [9] |

Challenge: Transferring Traditional HPLC Methods to Greener Alternatives

Problem: Your HPLC methods use large volumes of hazardous solvents like acetonitrile and methanol, generating significant toxic waste and posing occupational health risks [9] [3].

Solutions:

- Solvent Replacement: Substitute classical solvents with greener alternatives. For reversed-phase chromatography, ethanol and isopropanol can often replace more toxic solvents [3].

- Method Transfer to UHPLC: Transfer methods from HPLC to UHPLC using core-shell or sub-2µm particle columns to reduce analysis time, solvent consumption, and waste generation [3].

- Column Geometry Optimization: Use shorter columns with smaller internal diameters to significantly reduce solvent consumption while maintaining separation efficiency [3].

- Solvent Recycling: Implement systems for collecting and redistilling used mobile phase solvents for reuse in appropriate applications.

Challenge: Energy-Intensive Sample Preparation

Problem: Sample preparation techniques in standard methods are often multi-step, time-consuming, and require significant energy (e.g., Soxhlet extraction) [1].

Solutions:

- Adopt Green Sample Preparation (GSP) Principles:

- Accelerate sample preparation using vortex mixing, ultrasound, or microwave-assisted extraction [1]

- Implement parallel processing of multiple samples [1]

- Automate sample preparation to save time, reduce reagent consumption, and minimize human error [1]

- Integrate multiple steps into a single, continuous workflow [1]

- Replace Solvent-Intensive Techniques: Switch to modern alternatives like:

- Solid-phase microextraction (SPME)

- Microextraction techniques that use minimal solvents

The following workflow diagram illustrates the systematic process for assessing and improving the greenness of analytical methods:

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Item/Category | Function in Green Method Development | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep Software | Open-source tool for assessing sample preparation greenness | Provides quantitative score (0-1) to benchmark and improve methods [9] |

| Green Solvents (e.g., ethanol, ethyl acetate, Cyrene) | Replace hazardous solvents in extraction and chromatography | Lower toxicity, better biodegradability, often bio-based [3] |

| Microextraction Devices | Miniaturized sample preparation (SPME, SBSE) | Reduce solvent consumption from mL to µL volumes [1] |

| Core-Shell Chromatography Columns | Improved separation efficiency | Enable faster analysis with less solvent consumption [3] |

| Automated Sample Preparation Systems | Standardize and reduce manual handling | Improve reproducibility while reducing solvent use and exposure [1] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for Greenness Assessment

Protocol 1: Assessing Method Greenness Using AGREEprep

Purpose: To evaluate the environmental performance of sample preparation methods using the AGREEprep metric [9].

Procedure:

- Define Method Steps: Detail each step of the sample preparation process, including reagents, equipment, and conditions.

- Input Data into AGREEprep Software: Enter quantitative and qualitative parameters across the 10 assessment criteria:

- Sample preparation collection and preservation

- Amount of sample and collection device

- Transportation and storage

- Materials and chemicals consumption

- Energy consumption

- Waste generation

- Health and safety hazards

- Operator safety

- Throughput and efficiency

- Method scalability and applicability

- Calculate Score: The software generates a score between 0-1 and a pictorial representation.

- Interpret Results: Scores below 0.5 indicate poor greenness requiring significant improvements; scores above 0.7 represent acceptable green performance.

Troubleshooting Tip: If the method scores poorly on reagent toxicity, identify alternative solvents using the CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide or similar resources to find replacements with better environmental, health, and safety (EHS) profiles [3].

Protocol 2: Transferring HPLC Methods to Greener Alternatives

Purpose: To modify existing HPLC methods to reduce environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance [3].

Procedure:

- Baseline Assessment:

- Document current method parameters: mobile phase composition, flow rate, column dimensions, and run time.

- Calculate solvent consumption per analysis and total waste generation.

- Solvent Replacement Evaluation:

- Identify toxic solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol, n-hexane) for replacement.

- Test greener alternatives (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol, ethyl acetate) for chromatographic performance.

- Adjust pH and modifier concentrations as needed to maintain separation.

- Method Transfer to UHPLC:

- Select appropriate UHPLC column with sub-2µm particles.

- Scale method parameters according to column geometry.

- Optimize flow rate and gradient profile for maximum efficiency.

- Validation:

- Verify method performance against original validation criteria.

- Document reduction in solvent consumption and waste generation.

Troubleshooting Tip: If peak shape deteriorates with alternative solvents, consider using specially designed end-capped columns with reduced silanol activity to minimize secondary interactions [10].

The Path Forward: Implementing Sustainable Practices

The transition to greener analytical methods requires coordinated action across multiple stakeholders. Regulatory agencies play a critical role by establishing clear timelines for phasing out methods that score low on green metrics and integrating these metrics into method validation and approval processes [1]. Manufacturers should invest in developing more energy-efficient instruments and sustainable consumables. Most importantly, researchers and laboratory professionals must champion this transition by systematically assessing their current methods, implementing improvements where possible, and advocating for updated standards that prioritize both analytical excellence and environmental responsibility [8] [1].

The findings that 67% of standard methods score below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale highlight both the magnitude of the challenge and the opportunity for improvement [8]. By adopting the troubleshooting guides, assessment protocols, and improvement strategies outlined in this technical resource, analytical laboratories can significantly reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining the high-quality data required for research and regulatory compliance.

Practical Guides: Implementing Waste-Reducing Techniques in Sample Prep and Analysis

Core Principles of GSP and Assisted Extraction

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What makes ultrasound and microwave-assisted techniques "green"? These techniques are considered green because they significantly reduce the consumption of hazardous organic solvents and energy compared to traditional sample preparation methods like Soxhlet extraction. They achieve this by accelerating mass transfer, enabling faster extraction, and allowing for miniaturized procedures that minimize reagent use [11] [1]. This aligns with the core principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) to increase operator safety and decrease waste generation [11].

Q2: How do ultrasound and microwaves fundamentally differ in their mechanisms for accelerating mass transfer? While both are energy-assisted fields, their core mechanisms differ:

- Ultrasound-assisted extraction (USAE): Primarily relies on acoustic cavitation. Sound waves (typically 20-100 kHz) propagate through the solvent, creating microscopic bubbles that grow and violently implode. This implosion generates localized spots of extremely high temperature and pressure, disrupting sample matrices and enhancing solvent penetration [12] [13].

- Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE): Transforms electromagnetic energy (typically 300 MHz to 300 GHz) into thermal energy. This is achieved through dielectric heating, where polar molecules (e.g., water) within the sample continuously realign with the rapidly oscillating microwave field. This molecular agitation causes intense internal heating, which can rupture cell walls and improve the desorption and solubility of analytes [14].

Q3: Can these techniques be fully automated? Yes, automation is a key strategy in Green Sample Preparation (GSP) and is fully applicable to these methods. Automated systems save time, lower the consumption of reagents and solvents, reduce waste generation, and minimize human intervention, thereby lowering operator exposure to hazardous chemicals [1].

Troubleshooting Extraction Efficiency

Frequently Asked Questions

Q4: I am not achieving sufficient recovery rates with USAE. What are the key parameters to optimize? Low recovery in USAE is often linked to suboptimal cavitation. Focus on these key parameters, summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Recovery in Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction

| Parameter | Effect on Extraction | Recommended Adjustment |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasound Amplitude/Frequency | Directly influences cavitation energy. Higher amplitude increases intensity. | Systematically increase amplitude (e.g., from 10% to 40-70%) while monitoring recovery [15]. |

| Extraction Temperature | Higher temperature can improve solubility and mass transfer but may reduce cavitation intensity. | Optimize for your analyte; a common optimal range is 20-100°C, with 70°C being effective in some applications [15]. |

| Extraction Time | Must be sufficient for the process to reach equilibrium. | Test intervals (e.g., 1 to 30 minutes); longer times do not always guarantee better yields and can degrade thermolabile compounds [15]. |

| Solvent Composition | Polarity and viscosity affect cavitation efficiency and analyte solubility. | Match solvent polarity to your target analyte. Consider green solvents like Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) [14] [12] [11]. |

Q5: My results show significant variation between sample replicates. How can I improve precision? Poor precision in USAE is frequently due to non-uniform ultrasound energy distribution. To improve consistency:

- Ensure Proper Probe Placement: If using an ultrasonic probe, maintain a consistent depth and centering within the sample tube.

- Use an Ultrasound Bath: For processing multiple samples simultaneously, an ultrasound bath with a homogeneous field is preferable. One study achieved quantitative recoveries for twelve replicates simultaneously using an ultrasound bath [15].

- Control Temperature: Perform extractions in a thermostated bath or cup horn system to maintain stable and consistent conditions [15].

Q6: During MAE, my sample appears degraded. What could be the cause? Analyte degradation in MAE is typically caused by excessive thermal stress. To mitigate this:

- Optimize Microwave Power: Avoid using 100% power continuously. Use lower power settings or a pulsed power program to control heating [14].

- Monitor Temperature: Use a temperature sensor with feedback control to prevent overheating.

- Review Solvent Choice: Solvents with very high dielectric constants will heat extremely rapidly. A study on star anise polysaccharides noted that overexposure to microwave power could hydrolyze the target compound, leading to low yield [14].

Instrumentation and Workflow Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions

Q7: What is the "rebound effect" in Green Analytical Chemistry, and how can I avoid it? The rebound effect refers to a situation where the efficiency gains of a greener method lead to unintended consequences that offset the environmental benefits. For example, a cheap and fast microextraction method might lead a lab to perform a much higher number of extractions, ultimately increasing the total volume of chemicals used and waste generated [1]. Automation can also lead to over-testing simply because it is easy to run many samples.

To avoid this:

- Optimize testing protocols to eliminate redundant analyses.

- Implement a mindful laboratory culture where resource consumption is actively monitored.

- Use predictive analytics to determine when tests are truly necessary [1].

Q8: Should I choose an ultrasonic bath or an ultrasonic probe? The choice depends on your required throughput and energy density.

Table 2: Ultrasonic Bath vs. Probe System Selection

| Feature | Ultrasonic Bath | Ultrasonic Probe |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | High - Multiple samples can be processed in parallel [15]. | Low - Typically processes one sample at a time. |

| Energy Intensity | Lower - Energy is distributed throughout the bath. | Higher - Energy is focused directly into the sample. |

| Application | Ideal for high-throughput applications where extreme intensity is not required, or for simultaneous extraction of many replicates [15]. | Best for tough matrices that require high-intensity disruption or for very small volume samples. |

| Uniformity | Can be less uniform, depending on position in the bath. | Highly uniform for the specific sample being processed. |

Experimental Protocol: Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction for Trace Metal Analysis

The following workflow diagram outlines a method for determining total tin (Sn) in canned tomatoes, adapted from a published procedure [13]. This method replaces traditional wet digestion.

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Canned tomatoes are homogenized to ensure a consistent and representative sample [16] [13].

- Extraction: A suitable aliquot (e.g., 0.5 g) is weighed into a extraction vessel. Aqua regia (a 3:1 mixture of HCl and HNO₃) is added as the extraction medium. The sample is then subjected to ultrasound-assisted extraction. The original study tested various media and found aqua regia to be most effective [13].

- Post-Extraction Processing: The extract is centrifuged to separate any solid residues [16] [13].

- Sample Clean-up and Derivatization: The supernatant is subjected to a two-fold dilution with deionized water. L-cysteine is added to the diluted extract. This step is critical for the subsequent analysis, as it reduces interferents and facilitates the generation of tin hydride (SnH₄) [13].

- Analysis: The final solution is analyzed by Hydride Generation Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (HG-ICP OES). This technique provides high sensitivity and minimizes matrix interferences for elements like tin [13].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured ultrasound-assisted extraction experiment and related green chemistry applications.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment | Green Chemistry Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Aqua Regia (HCl:HNO₃) | Extraction medium for dissolving Sn from the tomato matrix. Effective for aggressive food products [13]. | While acidic, it enables a simplified, faster extraction that replaces more laborious and energy-intensive wet digestion methods [13]. |

| L-cysteine | Acts as a pre-reductant and masking agent. Converts Sn to the correct oxidation state for efficient hydride generation and reduces interferences [13]. | Improves the efficiency and selectivity of the analytical method, reducing the need for repeated analyses and saving reagents. |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) | Used as a green extraction solvent in various applications, such as extracting polysaccharides from star anise [14]. | Low toxicity, biodegradable, and often derived from natural sources. A key alternative to hazardous conventional organic solvents [14] [12] [11]. |

| Solid-phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Used for sample clean-up and preconcentration of analytes, isolating them from complex matrices [11]. | Minimizes solvent consumption compared to traditional Liquid-Liquid Extraction (LLE). Enables miniaturization and automation [11]. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support center provides targeted guidance for researchers and scientists implementing parallel processing and automation to maximize throughput and align with waste reduction strategies in analytical methods research. The following troubleshooting guides and FAQs address common experimental challenges.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Issue 1: Low Sample Throughput in Automated Sample Preparation

- Problem: The automated system is processing fewer samples per hour than expected.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Check for Hardware Bottlenecks: Verify that the automated liquid handler or robot is operating at its designated speed. Inspect for mechanical wear or misalignment that could slow down movement.

- Review Method Parameters: Ensure the method script is optimized. Look for unnecessary pauses, slow pipetting speeds, or redundant wash steps that can be minimized or eliminated.

- Evaluate Sample Queueing: For parallel processing systems, ensure that samples are fed into the system in a continuous stream to avoid idle time for the instruments. Strategy: Implement automated sample preparation, which aligns with Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles by saving time and lowering reagent consumption [1].

Issue 2: Data Processing Bottlenecks in Parallel AI Systems

- Problem: Data analysis from high-throughput experiments is delayed, creating a backlog.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Confirm Compute Resources: Verify that the system has access to scalable compute resources, such as GPU acceleration, which are essential for handling complex AI tasks [17].

- Profile the Workflow: Use monitoring tools to identify which specific step in the data pipeline (e.g., feature extraction, model inference) is the slowest.

- Check for Serial Dependencies: Review the analysis code to ensure that tasks that can run in parallel are not forced to run sequentially. Strategy: Adopt parallel artificial intelligence systems, which run multiple AI processes simultaneously to enhance speed and scalability for real-time decision-making [18].

Issue 3: Inconsistent Results After Automating a Manual Method

- Problem: Automated methods yield higher variance or systematic errors compared to manual techniques.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Calibration Check: Recalibrate all sensors, detectors, and pipetting units on the automated platform. Even minor drifts can compound over many runs.

- Review Environmental Controls: Automated systems may be more sensitive to ambient temperature or humidity fluctuations. Ensure the lab environment is stable.

- Validate Liquid Handling: Perform gravimetric analysis or dye-based assays to confirm the accuracy and precision of all liquid transfer steps in the new automated method.

Issue 4: High Solvent Waste Generation in an Automated HPLC Method

- Problem: The transition to an automated chromatography system has increased solvent waste.

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Audit Method Volumes: Scrutinize the method for opportunities to reduce scale (e.g., moving to a narrower bore column, reducing flow rates, or minimizing gradient delay volumes).

- Explore Solvent Recycling: Investigate if certain clean solvents from one run can be safely reclaimed and reused in subsequent mobile phase preparations.

- Implement Method Integration: Streamline multi-step processes into a single, continuous workflow. Strategy: This integration simplifies operations and cuts down on resource use and waste production, a key goal of Circular Analytical Chemistry [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the first steps in transitioning a manual sample preparation method to an automated, parallel one? Start by conducting a full process assessment to map out the existing workflow and identify bottlenecks [17]. Then, select a proven automation technology that allows for the parallel processing of multiple samples, which is an impactful strategy for increasing throughput and reducing energy consumed per sample [1]. Finally, develop a validation protocol to ensure the automated method meets all required analytical performance criteria.

Q2: Our automated system is producing large volumes of data we can't keep up with. How can we improve this? This is a common challenge. You should invest in a robust data management platform capable of handling both structured and unstructured data in real-time [17]. Furthermore, consider implementing parallel AI systems designed to analyze, respond, and learn from data in real-time, which fundamentally transforms how businesses handle massive data flows [18].

Q3: How can we prevent the "rebound effect" where efficiency gains from automation lead to increased, and potentially unnecessary, testing? The rebound effect is a recognized risk in green analytical chemistry [1]. To mitigate it:

- Establish and adhere to optimized testing protocols to avoid redundant analyses.

- Use predictive analytics to determine when tests are truly necessary.

- Foster a mindful laboratory culture where resource consumption is actively monitored and questioned.

Q4: What is the difference between rule-based automation and AI-powered automation for a research lab? The core distinction lies in decision-making and adaptability [17].

- Rule-Based Automation follows fixed

if-thenpathways. It is excellent for highly repetitive, predictable tasks with structured data but struggles with unexpected inputs or unstructured data. - AI-Powered Automation uses models to evaluate multiple variables, make contextual decisions, and learn from new scenarios. It is better suited for complex tasks like analyzing unstructured data (e.g., images), predicting instrument failures, or optimizing experimental parameters in real-time. A hybrid approach is often most practical.

Table 1: Automation Adoption and Impact Metrics

| Metric | Value / Statistic | Context / Source |

|---|---|---|

| Processes suitable for automation | A majority of simple or infrequent processes | Are often more efficiently managed manually [19] |

| Companies actively integrating AI | Over 70% | Companies worldwide [18] |

| Use of automation for migrations | 58% in 2024 | Increased from 43% in 2023 [19] |

| Standard methods with poor greenness | 67% | Scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale [1] |

Table 2: AI-Powered vs. Rule-Based Automation [17]

| Aspect | AI-Powered Automation | Rule-Based Automation |

|---|---|---|

| Data Processing | Handles unstructured data (e.g., natural language, images) | Requires structured, formatted data |

| Adaptability | Learns and improves from new scenarios | Needs manual updates for any changes |

| Error Handling | Manages exceptions and anomalies, flags for human review | Often fails with unexpected inputs |

| Decision Transparency | Complex decision paths ("black box") | Clear, auditable decision logic |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing Parallel Sample Preparation for Green Chemistry

- Objective: To adapt a traditional, serial sample preparation technique to a parallel format that reduces solvent consumption, energy use, and time per sample, in line with Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles [1].

- Materials: Multi-well plate platform, automated liquid handler, low-volume reagent reservoirs, miniaturized extraction devices.

- Method: a. System Setup: Configure the automated liquid handler with a method that processes samples in a 96-well plate format simultaneously. b. Volume Optimization: Scale down all reagent and solvent volumes proportionally to the miniaturized well size. c. Acceleration: Replace traditional heating (e.g., Soxhlet) with assisted fields like ultrasound to enhance extraction efficiency and speed up mass transfer [1]. d. Validation: Run a set of calibration standards and quality control samples in parallel to confirm analytical performance (linearity, accuracy, precision) is maintained or improved.

- Waste Reduction Strategy: The miniaturized, parallel system inherently minimizes sample size as well as solvent and reagent consumption, directly reducing waste generation [1].

Protocol 2: Integrating an AI-Powered Predictive Maintenance Model

- Objective: To deploy a machine learning model that predicts analytical instrument (e.g., HPLC) failures, minimizing downtime and preventing wasted runs and reagents.

- Materials: Historical instrument log data, cloud computing resources or local server with GPU support, monitoring software with API access.

- Method: a. Data Aggregation: Gather historical data on instrument performance, error logs, maintenance records, and environmental conditions. b. Model Training: Train a machine learning algorithm on this data to identify patterns that precede common failures (e.g., increasing pressure fluctuations predicting pump seal failure). c. Deployment & Integration: Deploy the model via an API and integrate it with the laboratory monitoring system. d. Action: Configure the system to automatically generate maintenance tickets or alert technicians when the model predicts a high probability of imminent failure.

- Waste Reduction Strategy: Preventing unexpected instrument downtime avoids the loss of valuable samples and the reagents used in interrupted analyses, contributing to a more efficient and waste-free operation.

Workflow Visualizations

Parallel Process Implementation

AI Powered Decision Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Automated, Waste-Reduced Workflows

| Item | Function in Parallel Processing & Automation |

|---|---|

| Automation-Compatible Tips | Specifically designed tips that ensure a proper seal and accurate liquid transfer on automated liquid handling workstations, critical for reproducibility [20]. |

| Multi-Well Plate Platforms | The foundational hardware for parallel sample preparation, allowing dozens or hundreds of samples to be processed simultaneously, drastically increasing throughput. |

| Low-Volume Reagent Reservoirs | Enable the miniaturization of reactions and assays, directly reducing the volume of expensive or hazardous reagents consumed per sample. |

| Recyclable Solvents | Solvents selected or processed for potential reuse in non-critical applications, aligning with circular economy principles by keeping materials in use [1]. |

| Integrated Sensor Systems | Miniaturized sensors (pH, O2, etc.) that can be embedded in flow systems or bioreactors for real-time, in-line monitoring, providing data for AI-driven process control. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Pressure in Miniaturized Flow Systems

Problem: System pressure is consistently lower than expected.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| System Leak [21] | Check all fittings and connections for visible solvent seepage. Inspect pump seals for moisture or droplets. | Re-tighten connections carefully. Replace damaged tubing or ferrules. Replace leaking pump seals. |

| Partially Obstructed Solvent Inlet Filter [21] | Remove the inlet filter from the solvent line. If pressure returns to normal, the filter is the cause. | Clean or, more effectively, replace the solvent inlet filter. |

Guide 2: Managing High Pressure in Miniaturized Chromatography

Problem: System pressure is significantly and persistently higher than the established baseline.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Debris Accumulation [21] | Systematically remove components (e.g., detector, column) from the flow path one at a time, starting downstream. Observe the pressure change after each removal. | Identify and replace/clean the obstructed component (e.g., inline filter, guard column). Implement more rigorous sample cleanup to prevent recurrence. |

| Column Blockage | Check if the high pressure is isolated to the column by comparing the system pressure with and without the column installed. | Flush the column according to manufacturer instructions. If flushing fails, replace the column. Use a guard column to protect the analytical column. |

Guide 3: Poor Analytical Performance After Method Transfer to a Miniaturized System

Problem: After transferring a method to a miniaturized platform (e.g., UHPLC, microfluidic), methods show issues like poor resolution, peak broadening, or inaccurate quantification.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incompatible Flow Path Dimensions | Audit the internal diameters (i.d.) and volumes of all system components (injector, tubing, detector cell) against the requirements of the miniaturized method. | Replace standard i.d. tubing with narrower capillaries. Ensure the injection volume and detector cell volume are appropriately scaled down. |

| Inadequate Greenness Assessment [22] | Use greenness assessment tools (e.g., AGREE, GAPI) to evaluate the transferred method. Low scores may reveal unsustainable or problematic steps that also affect performance. | Re-optimize the method to use greener solvents [3], reduce waste, and improve safety, which often concurrently enhances robustness and transferability. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary greenness assessment tools for analytical methods, and how do they differ?

Using multiple tools provides a more complete picture of a method's environmental impact. The table below summarizes key metrics.

| Tool Name | Type of Output | Key Focus Areas | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [22] | Binary pictogram (yes/no for 4 criteria) | PBT chemicals, corrosive waste, hazardous waste generation. | A simple, initial quick check. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [22] | Numerical score (100 = ideal) | Penalty points for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste. | Directly comparing the overall greenness of different methods. |

| GAPI [22] | Color-coded pictogram (5 parts) | Visual assessment of the entire analytical process from sampling to final determination. | Identifying which specific stages of a method have the highest environmental impact. |

| AGREE [22] | Numerical score (0-1) & circular pictogram | Comprehensive evaluation based on all 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry. | A modern, holistic, and easily interpretable single-method evaluation. |

| AGSA [22] | Numerical score & star-shaped diagram | Multiple green criteria, including reagent toxicity, waste, energy, and operator safety. | Visual, multi-criteria comparison where a larger star area indicates a greener method. |

Q2: Beyond miniaturization, what other strategies can make liquid chromatography greener?

Several complementary strategies exist:

- Solvent Replacement: Substitute toxic classical solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) with greener alternatives. For example, supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) uses supercritical CO₂ as the primary mobile phase, drastically reducing organic solvent waste [23] [3].

- Column Technology: Using shorter columns packed with smaller particles (e.g., sub-2µm) or core–shell particles reduces analysis time, solvent consumption, and energy use [3].

- Energy Efficiency: Modern UHPLC systems are more energy-efficient. Reducing analysis time and optimizing methods for lower temperatures also lower the carbon footprint [23] [3].

Q3: My miniaturized method is green, but the analysis time is too long. How can I improve throughput without sacrificing greenness?

This is a common challenge in White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which balances greenness with practical efficiency [3].

- Column Choice: Transfer the method to a column with a smaller particle size. This increases efficiency, allowing for faster flow rates or a shorter column while maintaining resolution.

- Method Optimization: Use modeling software or Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning to predict optimal conditions, minimizing trial-and-error experiments that consume time and resources [23].

- Instrumentation: Ensure you are using a instrument (e.g., UHPLC) designed to handle the higher pressures associated with faster flow rates on small-particle columns.

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Workflow Evaluation using AGREE

Purpose: To calculate a unified greenness score based on the 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) [22].

Procedure:

- Gather Method Parameters: Compile all details related to your analytical method, including: sample preparation steps, types and volumes of solvents/reagents, energy consumption (e.g., heating, centrifugation), equipment used, amount of waste generated, and operator hazards.

- Input Data into AGREE Tool: Use the publicly available AGREE software or calculator.

- Assign Scores: For each of the 12 GAC principles, input the required data or assign a score based on the method's compliance. The tool often uses a scale for each principle.

- Generate Output: The tool will output a circular pictogram with 12 sections (one for each principle) and an overall score between 0 (not green) and 1 (ideal green). The diagram is color-coded from red to dark green for easy interpretation.

- Interpret Results: Analyze the pictogram to identify weak areas (red/orange sections). For example, a red score for "Principle 2: Avoid sample pretreatment" would prompt you to investigate simplifying or eliminating sample preparation.

Protocol 2: Comparative Solvent Greenness and Carbon Footprint Evaluation

Purpose: To compare the environmental impact of different solvents and estimate the carbon footprint of an analytical method [22] [3].

Procedure:

- Select Assessment Metrics: Choose a set of complementary tools, such as:

- Profile Each Solvent/Method: For each solvent or method variant, compile data on:

- Health & Safety: Toxicity, flammability, carcinogenicity.

- Environment: Biodegradability, bio-based origin (e.g., Cyrene [3]).

- Carbon Footprint: Energy consumption per sample (kWh), solvent production route, waste disposal method.

- Calculate Scores: Input the data into the respective calculators for AGREEprep, CaFRI, etc.

- Compare Holistically: Create a table to compare the scores from all tools side-by-side. A method that scores well across multiple metrics is considered robustly green and sustainable.

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Strategy | Function / Rationale | Green & Practical Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) [22] [3] | A holistic framework for evaluating method sustainability, balancing Green (environmental), Red (analytical performance), and Blue (practicality) components. | Ensures that waste-reduction strategies do not compromise the method's accuracy, sensitivity, or ease of use, leading to more adoptable and robust methods. |

| AGREE & AGREEprep Software [22] | Quantitative and visual tools for assessing the greenness of an entire analytical method or specifically the sample preparation step. | Provides a data-driven, standardized score to justify and communicate the environmental benefits of a miniaturized method, supporting regulatory and publication requirements. |

| Micro-extraction Techniques [24] [22] | Sample preparation methods (e.g., SULLME) that use minimal solvent volumes (typically < 10 mL) for extraction and pre-concentration of analytes. | Drastically reduces solvent consumption and hazardous waste generation. Enables direct coupling with miniaturized analytical systems and on-site analysis. |

| Green Solvent Replacements [3] | Substituting traditional, hazardous solvents (e.g., acetonitrile) with safer, bio-based, or less toxic alternatives (e.g., Cyrene, ethanol, supercritical CO₂). | Reduces environmental impact, operator exposure risk, and waste disposal costs. SFC using CO₂ can eliminate over 90% of organic solvent waste [23]. |

| UHPLC with Sub-2µm Columns [23] [3] | Utilizes smaller particle sizes and higher pressures to achieve faster separations and superior resolution compared to traditional HPLC. | Reduces analysis time, solvent consumption per run, and laboratory energy consumption, thereby lowering the method's overall carbon footprint. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is process integration in the context of analytical research? Process integration is a systematic, holistic approach to the design and operation of processes. In a research context, it means analyzing and designing your entire experimental workflow as a unified system rather than a series of independent steps. The primary goal is to conserve resources, which can include energy, water, and materials, thereby minimizing waste generation and reducing operating costs [25].

Q2: How can combining preparation steps reduce waste in my lab? Integrating steps minimizes the total number of manipulations, which directly leads to less consumption of solvents, reagents, and single-use plastics [25] [26]. It also reduces the need for external utilities and cleaning between steps, conserving water and energy. This systematic prevention of waste at the source is more effective than managing waste after it is created [27].

Q3: What are the first steps to implementing process integration? The initial phase, often called Front-End Loading (FEL1) or concept screening, involves a high-level feasibility assessment [25]. The key steps are:

- Task Identification: Transform the high-level goal of waste reduction into specific tasks, such as minimizing fresh solvent usage or maximizing reagent reuse [25].

- Targeting: Determine the theoretical minimum resource consumption (e.g., solvents, energy) for your process before designing the specific integration. This sets a benchmark for excellence [25].

- Process Mapping: Create a detailed visual diagram of your current workflow, including all inputs, outputs, and subtasks [28].

Q4: What are common bottlenecks in analytical workflows? Common bottlenecks occur where tasks pile up and cause delays. In labs, these are often found at stages like sample preparation/intake, where requests exceed capacity; cleaning and drying; and data validation/approval, where methods are complex or require multiple checks [28]. Identifying these is crucial for optimization.

Q5: How can I track the success of my workflow integration? You should track performance metrics (KPIs) that align with your waste reduction goals. Key metrics can include:

- Material Use: Volume of solvent or reagent consumed per experiment.

- Waste Generation: Mass of hazardous or solid waste produced.

- Time Efficiency: Average time spent from sample receipt to data reporting.

- Error Rate: Frequency of procedure repeats due to errors, which waste materials [28]. Tracking these in a platform like a lab notebook or ELN makes reporting easier [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Increased Cross-Contamination After Combining Steps

Possible Cause: Inadequate cleaning or purging protocols between different sample types within the integrated system.

Solution:

- Action: Introduce a mini-clean-in-place (CIP) cycle between different sample batches. Use a small volume of a cleaning solvent, and investigate recycling this solvent for initial rinses of heavily soiled apparatus.

- Prevention: During the workflow design, include a decision point to evaluate sample compatibility before combining their paths. Ensure the cleaning step is a defined box in your workflow diagram.

Problem 2: The Integrated Workflow is Too Complex for Standard Operation

Possible Cause: The optimized workflow has too many decision points or non-standard equipment requirements, leading to poor adoption and errors [28].

Solution:

- Action: Simplify the workflow by removing unnecessary steps. Use a workflow diagram to identify and eliminate redundancies [28].

- Prevention: During the design phase, get your team on board and provide thorough training on the new, integrated process. An onboarding workflow can help engage team members [28].

Problem 3: Data Inconsistencies After Workflow Changes

Possible Cause: Manual data entry at multiple points in the new workflow increases the chance of human error [28].

Solution:

- Action: Audit the data flow and identify manual tasks that can be automated, such as data transfer from instruments to a LIMS (Laboratory Information Management System) [28].

- Prevention: Design the integrated workflow with digital data capture in mind from the start. Use templates in your electronic lab notebook to ensure consistency.

Problem 4: Higher Than Expected Solvent Consumption

Possible Cause: The new workflow does not effectively target and maximize solvent recycle and reuse.

Solution:

- Action: Revisit the targeting step of process integration. Apply principles like mass integration to identify the minimum theoretical amount of fresh solvent required by optimizing recycle streams [25].

- Prevention: Incorporate solvent recovery units (e.g., distillation) as an integrated part of the initial workflow design, not as an afterthought.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach to developing an integrated, waste-reducing experimental workflow, from analysis to implementation.

Research Reagent Solutions for Waste Reduction

The following table details key reagents and materials where strategic choices can significantly reduce waste in integrated analytical workflows.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Waste-Reduction Strategy & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Solvents (e.g., ACN, MeOH) | Mobile phase, extraction, cleaning. | Strategy: Implement in-process recycling/recovery (e.g., distillation).Rationale: Reduces volume of hazardous waste generated and lowers consumption of fresh, high-purity solvents [25]. |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemically modifying analytes for detection. | Strategy: Use automated, flow-based systems with microliter volumes.Rationale: Minimizes the use of often toxic and expensive reagents by precisely controlling reaction scales, preventing surplus waste [25]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Sample clean-up and analyte concentration. | Strategy: Select reusable sorbents or switch to online SPE.Rationale: Eliminates or reduces the number of disposable plastic SPE cartridges, a significant source of plastic waste [26]. |

| Catalysts | Accelerating chemical reactions. | Strategy: Use immobilized heterogeneous catalysts.Rationale: Allows for easy recovery and reuse across multiple reaction cycles, reducing the amount of metal and ligand waste in the product stream [25]. |

| Calibration Standards | Instrument calibration and quantification. | Strategy: Prepare smaller, more frequent batches and share stocks between team members.Rationale: Prevents the degradation of large stock solutions, which often leads to disposal of expired, unused materials [27]. |

| pH Buffers | Maintaining stable pH conditions. | Strategy: Optimize buffer volume and explore biodegradable buffer compounds.Rationale: Reduces liquid waste volume and minimizes the environmental impact of the waste stream [26]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary low-energy assisted heating technologies suitable for research facilities? The primary technologies are Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHPs) and advanced Air-Source Heat Pumps. GSHPs use the stable temperature of the earth below the frost line for highly efficient thermal exchange. They can provide both heating and cooling [29] [30]. Advanced air-source heat pumps, particularly cold-climate models, have seen significant development and can operate efficiently in lower outdoor temperatures [31].