Green Shift in the Lab: A Strategic Guide to Transferring Analytical Methods for Sustainability

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to transition from traditional analytical methods to greener alternatives without compromising data integrity or regulatory compliance.

Green Shift in the Lab: A Strategic Guide to Transferring Analytical Methods for Sustainability

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to transition from traditional analytical methods to greener alternatives without compromising data integrity or regulatory compliance. It explores the foundational principles of Green and Circular Analytical Chemistry, detailing practical strategies for adapting sample preparation and core techniques. The content addresses common transfer challenges and coordination failures, offering troubleshooting and optimization advice. Furthermore, it guides readers on validating new green methods using modern metrics like AGREE and AGREEprep, and on executing compliant comparative transfers to ensure the new methods are robust, equivalent, and ready for implementation in quality control and research environments.

The Why Behind the Green Shift: Principles of Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

Core Concepts: Sustainability vs. Circularity

While often used interchangeably, sustainability and circularity are distinct concepts in green chemistry. Understanding this difference is crucial for setting accurate goals and evaluating the true environmental impact of your laboratory methods.

| Aspect | Circularity | Sustainability |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Material flows and resource cycles [1] | Holistic environmental, economic, and social impacts [2] |

| Central Goal | Eliminate waste, keep products/materials in use [1] [2] | Meet present needs without compromising future generations [2] |

| Key Principle | "Circular" systems (e.g., reuse, recycle) | "Triple Bottom Line" (planet, people, profit) |

| Relationship | A means to an end; a strategy [2] | The overarching end goal [2] |

| Measurement | Circularity Indicators (e.g., Material Circularity Indicator) [1] | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [3] [2] |

A circular practice is not automatically sustainable. For example, a recycling process that consumes excessive energy might improve circularity but have a higher overall carbon footprint, making it less sustainable [2]. Similarly, developing more fuel-efficient cars could lead to people driving longer distances, negating the envisioned environmental benefits—a phenomenon known as the "rebound effect" [2]. Therefore, circularity should be viewed as a powerful strategy within the broader, multi-dimensional goal of sustainability.

Troubleshooting Common Challenges in Greener Method Transfer

Adopting greener analytical techniques often presents specific challenges. Below are common issues and structured guidance for resolving them.

FAQ: My new green method (e.g., Micellar Chemistry) isn't yielding the expected results. Where do I start?

A systematic troubleshooting approach is key. Follow these steps to diagnose the problem [4]:

- Identify the Problem: Precisely define what is going wrong without assuming the cause (e.g., "reaction yield is 30% lower than literature value," not "the catalyst is bad").

- List All Possible Explanations: Brainstorm every potential cause, from the obvious (reagent quality, catalyst loading) to the less obvious (water purity, mixing efficiency, residual oxygen).

- Collect Data: Review your data and procedure. Were all appropriate controls used? Check storage conditions and expiration dates of all chemicals, especially surfactants and catalysts. Compare your detailed lab notebook entries against the original method protocol.

- Eliminate Explanations: Rule out causes that the data shows are not relevant (e.g., if controls worked, the core protocol is likely sound).

- Check with Experimentation: Design targeted experiments to test the remaining possibilities. For micellar chemistry, this could involve testing a new batch of surfactant or varying the agitation speed.

- Identify the Cause: Based on the experimental results, pinpoint the root cause and implement a fix.

FAQ: How do I know if my new "circular" lab practice is actually more "sustainable"?

To avoid circularity being mistaken for full sustainability, you must measure broader environmental impacts [2].

- Use Holistic Metrics: Move beyond simple circularity indicators. Employ Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to evaluate cumulative environmental impacts, including global warming potential and resource depletion, across the entire method lifecycle [2].

- Calculate Process Mass Intensity (PMI): A key green chemistry metric, PMI measures the total mass of inputs (solvents, reagents, etc.) per mass of product. A lower PMI indicates higher resource efficiency and a more sustainable process [3].

- Check for Rebound Effects: Consider if your circular improvement could lead to increased consumption or other negative consequences elsewhere in the system [2].

Experimental Protocol: Transitioning a Sonogashira Coupling to Aqueous Micellar Conditions

This protocol is adapted from a successful transition in the synthesis of an antimalarial drug candidate, MMV688533 [3].

Goal: Replace a traditional organic solvent-based Sonogashira coupling with a greener aqueous micellar method.

Key Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent | Function & Green Benefit |

|---|---|

| Non-ionic Surfactant (e.g., TPGS-750-M) | Forms micelles in water that act as nanoreactors, enabling organic reactions in water and reducing organic solvent waste [3]. |

| Palladium Catalyst | Facilitates the cross-coupling reaction. Benefit: Micellar conditions often allow for significantly reduced catalyst loadings (e.g., from 10 mol% to 0.5 mol%) [3]. |

| Sodium Formate | In some newer green cross-coupling methods, it can replace hazardous organometallic reagents as a cheap, safe, and effective replacement [5]. |

| Water | The primary reaction solvent, drastically reducing the use of hazardous and volatile organic solvents. |

Procedure:

- Micelle Preparation: In a reaction vessel, add the non-ionic surfactant (e.g., 2% w/w TPGS-750-M) to deionized water. Stir the mixture to form a clear, homogeneous micellar solution.

- Charge Substrates: Add the palladium catalyst, copper co-catalyst (if required), and organic substrates to the micellar solution.

- Run Reaction: Stir the reaction mixture at the recommended temperature (often room temperature or slightly elevated) and monitor by TLC or LC-MS until completion.

- Work-up: Upon completion, extract the desired product from the aqueous micellar solution using a minimal amount of a green solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate or 2-MeTHF). The aqueous micellar solution can often be recycled for subsequent runs.

- Analysis: Determine yield and purity. Use ICP-MS to measure residual palladium metal to ensure it meets regulatory standards (e.g., <10 ppm) [3].

Quantitative Comparison: Traditional vs. Sustainable Synthesis

The effectiveness of integrating sustainability and circularity is demonstrated by the revised synthesis of MMV688533 [3].

Table: Environmental Impact Comparison for API Synthesis

| Metric | Traditional Discovery Route | Sustainable Route (Aqueous Micellar) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Yield | 6.4% | 64% [3] |

| Palladium Catalyst Loading | 10 mol% | 0.5 mol% (20-fold decrease) [3] |

| Residual Palladium in API | 3760 ppm | <8.45 ppm (under FDA limit) [3] |

| Process Mass Intensity (PMI) | 287 | 111 (less than half the input mass) [3] |

| Key Solvents | Hazardous organic solvents | Water as primary solvent [3] |

Table: Circularity vs. Sustainability Assessment Framework

| Aspect to Measure | Circularity-Focused Metric | Sustainability-Focused Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Use | Volume of solvent recycled | Process Mass Intensity (PMI) [3] |

| Waste | Mass of waste sent for recycling | Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of waste treatment [2] |

| Material Sourcing | Use of bio-based/recycled feedstocks | Environmental impact of feedstock production (via LCA) [2] |

| Energy | N/A | Cumulative Energy Demand (via LCA) [2] |

Core Concepts: A Paradigm Shift

The transition in analytical chemistry and drug development from traditional, resource-intensive methods to greener alternatives mirrors the broader economic shift from a linear to a circular model. This transition is not merely an environmental consideration but a comprehensive framework for enhancing resource efficiency, reducing waste, and building more resilient research operations [6].

The Linear Model ("Take-Make-Dispose")

The linear model has historically dominated both industrial production and laboratory practices. It is characterized by a one-way flow of materials [7] [8].

- Take: Extract or purchase virgin raw materials and reagents.

- Make: Use these materials in synthesis, analysis, or drug formulation.

- Dispose: Discard waste, solvents, and single-use consumables after the experiment is complete.

This model creates significant challenges for laboratories, including rising costs for chemical and waste disposal, vulnerability to supply chain disruptions for critical materials, and a growing environmental footprint [7] [9].

The Circular Model

The circular model offers a regenerative alternative, designed to eliminate waste and keep products and materials in use at their highest value for as long as possible [10]. Its core principles, applied to a research context, are:

- Designing Out Waste and Pollution: This involves creating analytical methods that minimize solvent and reagent consumption from the outset [8] [6].

- Keeping Products and Materials in Use: This means circulating reagents, solvents, and materials within the lab through reuse, recovery, and remanufacturing [8] [11].

- Regenerating Natural Systems: Prioritizing the use of renewable, biodegradable, or less hazardous materials where scientifically feasible [10].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural differences between these two economic models.

Quantitative Comparison: Linear vs. Circular

The rationale for transitioning to a circular model is supported by compelling data on resource use, waste generation, and economic impact. The table below summarizes key performance indicators that highlight the limitations of the linear approach and the potential benefits of circularity.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Differences Between Linear and Circular Models

| Performance Indicator | Linear Model Performance | Circular Model Potential | Data Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Resource Reuse/Recycling | ~8.6% of 100B tons annually recycled (2020) | Target: Significantly higher material circularity | [12] |

| Global Material Waste | >90% of raw materials wasted after single use | Aims to design out waste; keeps materials in use | [7] |

| Projected Waste Increase (by 2050) | 70% surge (to 3.4B tons/year) | Model aims to reverse this trend | [7] |

| Projected Raw Material Demand (by 2060) | Expected to double (OECD) | Decouples growth from virgin resource extraction | [7] |

| Economic Value of Lost Materials (EU) | €600B annually from resource inefficiency | Recovers value via reuse and recycling | [7] |

| GDP Impact (EU by 2030) | -- | Potential boost of €1.8T | [7] |

| Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Impact | Contributes significantly to emissions | CE practices, innovation, and taxes reduce GHG | [12] |

Troubleshooting the Transition: A Greener Method Transfer Guide

Transferring analytical methods to greener techniques within a circular framework presents specific challenges. This guide addresses common issues and provides structured solutions.

FAQ: Navigating Common Challenges

Q1: Our lab wants to reduce solvent waste, but we are concerned about compromising data integrity and regulatory compliance. How can we proceed safely?

- A: Start with a gap analysis. Techniques like Microscale Chemistry or Automated Method Translation (e.g., scaling down from HPLC to UHPLC) can reduce solvent consumption by over 50% without altering the fundamental chemistry, thus preserving validity. Document the entire process, including a side-by-side comparison of validation parameters (precision, accuracy, linearity) between the old and new methods to demonstrate equivalence to regulatory bodies [11].

Q2: We rely on single-use plastic consumables for sterility and convenience. What are viable circular alternatives that maintain experimental integrity?

- A: The circular principle of "narrowing resource flows" applies here. First, evaluate if certified, reusable glassware (e.g., Duran bottles) can be implemented for certain solutions. If single-use is necessary, partner with suppliers who have take-back programs to recycle pipette tip boxes, specimen containers, or other plastics into new lab-grade products, creating a closed-loop system and aligning with Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) concepts [9] [10].

Q3: How can we practically handle the recovery and reuse of expensive or hazardous solvents?

- A: Implementing a Solvent Recovery Protocol is key. This involves:

- Segregation: Collecting different categories of waste solvent (e.g., non-halogenated, halogenated, aqueous) in dedicated, labeled containers to avoid cross-contamination [11].

- Assessment: Analyzing the waste stream via GC or GC-MS to determine purity and identify contaminants.

- Purification: Using in-lab distillation equipment to recover solvents of sufficient purity for non-critical tasks like initial glassware washing or as a mobile phase component in preparatory chromatography. This process turns a waste liability into a valuable in-lab resource [13].

- A: Implementing a Solvent Recovery Protocol is key. This involves:

Q4: Our current method uses a reagent derived from a scarce metal. How can we find a greener, more sustainable substitute?

- A: This is an opportunity for innovation. Apply the circular principle of "material substitution." Research and test catalysts based on more abundant and less toxic metals (e.g., iron, copper). Alternatively, explore bio-based catalysts or enzymatic reactions, which are often derived from renewable resources and operate under milder conditions, reducing energy consumption as well [6].

Experimental Protocol: A Circularity Assessment for Analytical Methods

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology to evaluate and improve the circularity of your analytical techniques.

1. Objective: To quantitatively assess the environmental and resource efficiency of an existing analytical method and identify opportunities for implementing circular principles.

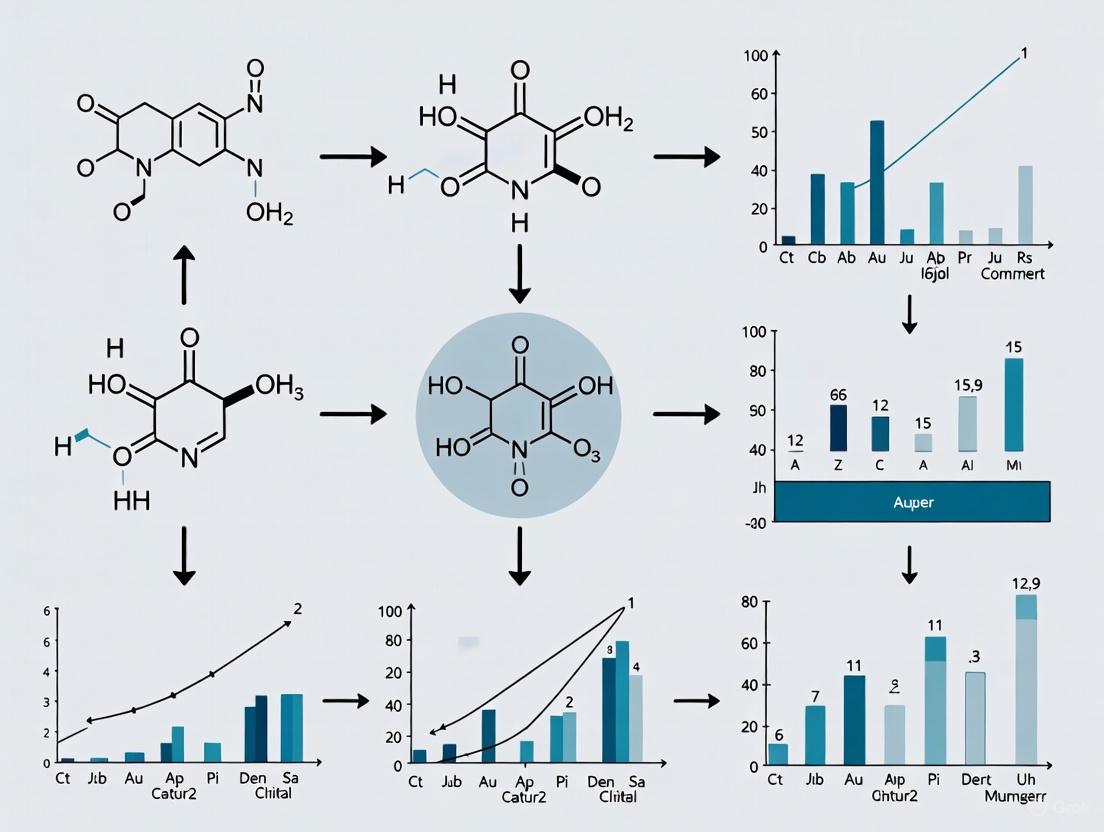

2. Experimental Workflow: The assessment follows a logical sequence of characterization, analysis, and optimization, as visualized in the workflow below.

3. Detailed Methodology:

Phase 1: Material Inventory & Mapping

- Procedure: For three consecutive runs of the method, meticulously record all inputs and outputs.

- Data Collection:

- Inputs: Mass/volume of all reagents, solvents, and catalysts; energy consumption (e.g., instrument kWh); and type/quantity of consumables (e.g., columns, vials, gloves).

- Outputs: Mass/volume of all waste streams, including post-reaction mixtures, spent solvents, and used consumables.

- Deliverable: Create a comprehensive input/output mass balance for the method [11].

Phase 2: Waste Stream Analysis

- Procedure: Segregate the waste outputs identified in Phase 1.

- Analysis:

- Hazard Classification: Classify each waste stream according to laboratory safety standards (e.g., flammable, toxic, corrosive).

- Value Identification: Identify components within the waste that have potential for recovery (e.g., precious metal catalysts, high-purity solvents).

- Recyclability Assessment: Check with suppliers or waste contractors for available recycling pathways for specific plastics, metals, or solvents [11] [10].

Phase 3: Identification of Circular Alternatives

- Procedure: Brainstorm and research alternatives for the most significant waste streams and resource-intensive inputs based on the "4 Rs" framework.

- Application of Principles:

- Reduce: Can the method be miniaturized or made more efficient? Can solvent volumes be reduced?

- Reuse: Can any solvent or catalyst be recovered and reused directly?

- Recycle: Can spent materials be processed into new resources?

- Redesign: Is there a different, less wasteful analytical technique that can achieve the same result? [14] [6]

Phase 4: Implementation & Validation

- Procedure: Select the most promising alternative from Phase 3 and run a parallel comparison between the original and the modified "circular" method.

- Validation: Key performance indicators must include:

- Analytical Figures of Merit: Precision, accuracy, limit of detection, and specificity.

- Circularity Metrics: Percentage reduction in solvent use, mass of waste generated, and percentage of waste streams diverted from disposal via recycling/recovery.

- Documentation: Compile all data into a method transfer report that justifies the change on both scientific and sustainability grounds [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for a Circular Lab

Transitioning to circular practices involves rethinking the materials and solutions used daily in the lab. The following table details key reagents and their functions from a circular perspective.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for a Circular Economy Lab

| Tool/Reagent Category | Traditional/Linear Example | Circular & Greener Alternative | Function & Circularity Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvents | Virgin-grade Acetonitrile, Hexane | In-lab recovered solvents (via distillation); Bio-derived solvents (e.g., Cyrene from cellulose) | Reduces reliance on virgin petrochemicals and waste disposal. Lowers environmental impact and toxicity [13] [6]. |

| Catalysts | Palladium, other scarce metal catalysts | Heterogeneous catalysts (reusable filters/beads); Catalysts from abundant metals (Fe, Cu); Enzymes (Biocatalysis) | Enables recovery and reuse multiple times. Uses more sustainable and less toxic elements, often from renewable sources [6]. |

| Sample Prep & Consumables | Single-use solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges | Reusable labware (e.g., glass columns for chromatography); Consumables from recycled/recyclable plastics (with take-back programs) | Drastically reduces plastic waste. Closes the material loop, aligning with EPR principles [9] [10]. |

| Analytical Standards | Individually prepared, high-volume stock solutions | Shared stock solutions within a lab; Stable, multi-component standards to reduce preparation frequency and waste. | "Narrows" resource flow by minimizing excess production and disposal of standard materials, saving costs and resources [11]. |

The paradigm of sustainability in analytical science is evolving beyond a simple binary choice. The concepts of weak sustainability and strong sustainability represent fundamentally different approaches to incorporating environmental considerations into scientific practice. Weak sustainability, rooted in neoclassical economics, suggests that different types of capital—natural, human, and physical—are substitutable, allowing for the depletion of natural resources as long as other forms of capital are created to compensate [15]. In analytical chemistry, this might manifest as continuing energy-intensive practices while purchasing carbon offsets or using slightly less toxic solvents without fundamentally changing methodological approaches.

In contrast, strong sustainability recognizes that certain natural systems and resources are irreplaceable and must be protected intact. This perspective, emerging from ecological economics, requires that the stock of natural capital not decline over time, acknowledging that many environmental functions cannot be replaced by human-made alternatives [15]. For the analytical scientist, this paradigm demands a fundamental rethinking of methods, instrumentation, and workflows to minimize environmental impact while maintaining analytical effectiveness.

The most comprehensive framework emerging in recent years is White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which expands the conversation beyond purely environmental concerns. WAC balances three equally important components: the green (environmental impact), red (analytical performance), and blue (practicality and cost-effectiveness) aspects of methodological choices [16]. This integrated approach ensures that sustainability efforts do not compromise the essential analytical attributes required for effective research and quality control, particularly during the critical process of method transfer to greener techniques.

Core Concepts: From Green to White Analytical Chemistry

The Evolution of Sustainable Analytical Principles

The journey toward sustainable analytical chemistry began with the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry established by Anastas and Warner, which were subsequently adapted into the 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) [16]. These principles provide a foundational framework for reducing the environmental footprint of analytical methods, with particular emphasis on:

- Reducing or eliminating toxic solvent use in analytical methods

- Minimizing energy consumption throughout analytical workflows

- Prioritizing waste prevention rather than treatment after generation

- Implementing real-time analysis for pollution prevention

While GAC represents a crucial step forward, it primarily focuses on environmental considerations, potentially at the expense of analytical performance and practical implementation. This limitation led to the development of more holistic frameworks.

The White Analytical Chemistry Framework

White Analytical Chemistry represents a significant evolution in sustainable analytical thinking, creating a balanced approach where environmental goals do not overshadow analytical needs. The WAC framework equally weights three critical components:

- Green Component: Environmental impact, solvent toxicity, waste generation, and energy consumption

- Red Component: Analytical performance including sensitivity, accuracy, precision, selectivity, and robustness

- Blue Component: Practical considerations such as cost-effectiveness, availability of equipment and reagents, ease of use, and operator safety [16]

This balanced approach is particularly valuable when transferring classical liquid chromatographic methods to more sustainable alternatives, as it ensures that the converted methods remain practically viable and analytically sound while reducing environmental impact [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Chemistry Frameworks

| Framework | Primary Focus | Key Principles | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green Chemistry | Environmental impact reduction | 12 principles including waste prevention, safer chemicals | Comprehensive environmental focus | Can overlook analytical performance |

| Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) | Minimizing environmental footprint of analysis | 12 principles adapted for analytical chemistry | Directly addresses analytical methodologies | May compromise analytical effectiveness |

| Blue Analytical Chemistry | Practicality and economic viability | Cost-effectiveness, ease of implementation | Ensures methods are practically applicable | Does not fully address environmental concerns |

| White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) | Balanced sustainability | Equal weighting of green, red, and blue components | Comprehensive balance of all key factors | More complex implementation |

Implementing Sustainable Method Transfer: A Practical Framework

Strategic Approaches to Method Transfer

Transferring analytical methods to greener alternatives requires a structured approach to ensure successful implementation. Several formal transfer strategies have been established, each appropriate for different circumstances:

- Comparative Testing: Both transferring and receiving laboratories analyze identical samples using the method, with results statistically compared to demonstrate equivalence [17] [18]. This approach is most suitable for well-established methods where both laboratories have similar capabilities.

- Co-validation: The analytical method is validated simultaneously by both transferring and receiving laboratories, ideal for new methods being developed specifically for multi-site use [17] [18].

- Revalidation: The receiving laboratory performs a full or partial revalidation of the method, necessary when transferring to laboratories with significantly different equipment or environmental conditions [17] [18].

- Transfer Waiver: In rare, well-justified cases where the receiving laboratory has demonstrated proficiency with the method, the formal transfer process may be waived with robust scientific justification [17].

Green Solvent Selection and Method Transfer

A primary strategy for greening liquid chromatography methods involves substituting hazardous organic solvents in the mobile phase with greener alternatives. The selection process must balance environmental, health, and safety concerns with chromatographic suitability.

Table 2: Greenness Ranking and Properties of Common Chromatographic Solvents

| Solvent | Environmental Impact | Health & Safety | Chromatographic Suitability | Greenness Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water | Minimal | Excellent | Limited solubility for non-polar compounds | 1 (Greenest) |

| Ethanol | Biobased sources available | Low toxicity, biodegradable | Polar, suitable for reversed-phase | 2 |

| Acetone | Low environmental persistence | Low toxicity concerns | Excellent solvent properties | 3 |

| Ethyl Acetate | Readily biodegradable | Moderate irritation potential | Medium polarity, normal phase | 4 |

| Heptane | High environmental persistence | High toxicity, neurotoxic | Non-polar, normal phase | 16 (Least Green) |

| Hexane | High environmental persistence | High toxicity, neurotoxic | Non-polar, normal phase | 17 |

When transferring methods to greener solvents, several technical considerations ensure success:

- Select solvents with similar polarity and solubility parameters to maintain separation efficiency

- Adjust gradient profiles to account for differences in solvent strength

- Verify detector compatibility, especially with UV-Vis detection where alternative solvents may have different UV cutoffs

- Consider column compatibility as some greener solvents may affect column stability differently than traditional solvents [16]

Instrumentation and Column Technologies for Sustainable Analysis

Beyond solvent selection, leveraging modern instrumentation and column technologies significantly enhances method sustainability:

- UHPLC and UHPSFC systems operate at higher pressures, enabling faster separations with reduced solvent consumption [19]

- Core-shell particle columns provide high efficiency with lower backpressure than fully porous sub-2μm particles

- Monolithic columns permit high flow rates with minimal backpressure, reducing analysis time

- Smaller internal diameter columns (e.g., 2.0mm vs. 4.6mm) dramatically reduce mobile phase consumption [16]

The transition to these technologies represents strong sustainability by fundamentally redesigning analytical processes rather than merely mitigating the impact of existing approaches.

Troubleshooting Guides for Sustainable Method Transfer

Systematic Troubleshooting Methodology

Implementing a systematic approach to troubleshooting ensures efficient problem resolution during method transfer to greener techniques. The following methodology provides a structured framework:

- Identify the Problem: Clearly define the issue without presuming causes (e.g., "peak broadening in transferred UHPLC method" rather than "wrong column temperature") [20]

- List Possible Causes: Brainstorm all potential explanations, including solvent compatibility, column chemistry, instrument parameters, and operator technique [20]

- Collect Data: Systematically gather information, beginning with the simplest explanations, including control results, equipment performance verification, and procedure adherence [20]

- Eliminate Causes: Rule out improbable explanations based on collected data [20]

- Test Experimentally: Design targeted experiments to test remaining hypotheses [20]

- Identify Root Cause: Determine the fundamental origin of the problem, not just superficial symptoms [20]

Common Issues and Solutions in Sustainable Method Transfer

Problem: Changes in Selectivity After Transfer to Greener Solvents

- Possible Causes:

- Differences in solvent polarity and solvation properties

- pH variations in alternative mobile phases

- Stationary phase interaction changes

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify solvent miscibility and mixture homogeneity

- Precisely control and measure mobile phase pH

- Test columns from different manufacturers with similar chemistry

- Adjust gradient profile to compensate for solvent strength differences [16]

Problem: Increased Backpressure in Transferred Methods

- Possible Causes:

- Higher viscosity of alternative solvents

- Incompatibility of green solvents with column hardwar

- Particulate contamination from alternative solvents

- Troubleshooting Steps:

Problem: Baseline Noise or Drift After Method Transfer

- Possible Causes:

- Different UV cutoff of alternative solvents

- Impurities in greener solvent grades

- Degradation of alternative solvents during analysis

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check UV absorbance profile of alternative solvents

- Use higher purity solvents specifically designed for HPLC

- Incorporate column temperature control to improve baseline stability

- Purge system thoroughly to remove residual traditional solvents [21]

Frequently Asked Questions: Sustainable Analytical Practice

Q: How do I balance sustainability goals with regulatory requirements when modifying compendial methods?

A: Begin with a thorough gap analysis comparing your sustainable alternative to the compendial method. For regulated environments, implement a structured method transfer protocol demonstrating that your green method provides equivalent or better results. Document the comparative testing thoroughly, focusing on key method attributes like accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness [17] [22]. This approach positions your sustainable method as an improvement rather than just a modification.

Q: What metrics should I use to evaluate the sustainability of my analytical methods?

A: Multiple metrics are available:

- Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS): Provides a unified metric for environmental impact [19]

- Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric: Evaluates methods against the 12 principles of GAC [23]

- White Analytical Chemistry (WAC): Provides balanced scoring across green, red, and blue components [16]

- Carbon footprint calculations: Estimate energy consumption and CO₂ emissions [16]

Q: How can I justify the initial investment in sustainable analytical technologies?

A: Frame your justification using a total cost of ownership perspective that includes:

- Reduced solvent purchase and waste disposal costs

- Lower energy consumption with modern instrumentation

- Increased sample throughput with faster methods

- Regulatory risk reduction through proactive sustainability

- Corporate social responsibility alignment [16] [19]

Q: What are the most effective first steps toward sustainable chromatography?

A: Begin with these high-impact, manageable steps:

- Replace acetonitrile with ethanol in reversed-phase HPLC where possible

- Implement method transfer to smaller diameter columns (e.g., 2.1mm vs. 4.6mm)

- Switch from normal-phase to greener techniques like HILIC or SFC

- Consolidate multiple methods to reduce method-specific validation

- Extend column lifetime with proper maintenance and guard columns [16]

Essential Tools and Reagents for Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Method Development

| Reagent/Technology | Function | Sustainable Advantage | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents | Mobile phase components | Renewable feedstocks, reduced toxicity | Cyrene shows promise as bio-based alternative to DMF/DMSO [16] |

| Ethanol | Polar solvent for reversed-phase | Low toxicity, biodegradable | Often requires adjustment of gradient profiles compared to acetonitrile |

| Superficially Porous Particles | Stationary phase technology | Higher efficiency permits shorter columns | Reduces solvent consumption by up to 60% while maintaining resolution |

| Monolithic Columns | Continuous stationary phase | Very low backpressure enables high flow rates | Ideal for rapid analysis with minimal solvent consumption |

| Column Switching Systems | Multi-dimensional separation | Targeted analysis reduces complete system usage | Enables heart-cutting techniques for complex matrices |

| SFC Systems | Alternative to normal-phase | Uses liquid CO₂ as primary mobile phase | Eliminates most hazardous solvent use in normal-phase separation |

The transition from weak to strong sustainability in analytical science represents a fundamental shift in how we conceptualize methodological choices. Weak sustainability approaches that merely mitigate the environmental impact of existing practices are no longer sufficient. Instead, the field must embrace strong sustainability principles that fundamentally redesign analytical processes to minimize environmental impact while maintaining or enhancing analytical performance.

The White Analytical Chemistry framework provides a balanced approach for this transition, ensuring that environmental goals do not compromise the analytical integrity and practical utility that make methods valuable in research and quality control settings. By implementing structured method transfer protocols, leveraging modern instrumentation and column technologies, and adopting systematic troubleshooting approaches, laboratories can successfully navigate the transition to more sustainable analytical practices.

As the field continues to evolve, the integration of sustainability considerations throughout the analytical method lifecycle will become increasingly important, moving from a secondary consideration to a fundamental attribute of analytical quality. This paradigm shift promises not only to reduce the environmental footprint of analytical science but to drive innovation in methodological approaches that benefit both science and society.

The transition towards sustainable science has made the adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) essential. GAC focuses on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods by reducing hazardous waste, energy consumption, and the use of toxic substances [24]. Circular Analytical Chemistry represents a paradigm shift, aiming to transform the entire analytical chemistry sector into a resource-efficient, closed-loop, and waste-free system by redefining waste as a resource and keeping products and materials in circulation for as long as possible [25]. Understanding these frameworks is crucial for successful method transfer to greener techniques.

The Twelve Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC)

The 12 principles of GAC provide a direct framework for making analytical methodologies more environmentally benign [24]. They are primarily concerned with the environmental impact of the "consumption" and "disposal" phases of analysis.

- Direct analytical techniques should be applied to avoid sample treatment.

- Minimal sample size and minimal number of samples are goals.

- In-situ measurements should be performed.

- Integration of analytical processes and operations saves energy and reduces the use of reagents.

- Automated and miniaturized methods should be selected.

- Derivatization should be avoided. (This step often uses additional reagents and generates waste).

- Generation of a large volume of analytical waste should be avoided and proper management of analytical waste should be provided.

- Multi-analyte determinations are preferred over methods for one analyte at a time.

- The use of energy should be minimized.

- Reagents obtained from renewable sources should be preferred.

- Toxic reagents should be eliminated or replaced.

- The safety of the operator should be increased.

The Twelve Goals of Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC)

Circular Analytical Chemistry goes beyond the laboratory-focused approach of GAC by applying circular economy principles to the entire analytical system, from production and consumption to post-use waste [25]. Its twelve goals aim for a radical transformation to decouple analytical performance from resource consumption.

- Waste valorization: Treat waste as a resource and use it as a potential input for other processes.

- Resource efficiency: Use the minimum amount of resources, including materials, water, and energy.

- Circulation of materials: Design analytical chemistry products for durability, reuse, and recycling.

- Renewable energy: Power analytical activities with energy from renewable sources.

- Elimination of hazardous substances: Replace substances of concern with safer alternatives.

- Process intensification: Develop more efficient processes that require less space, material, and energy.

- Design for circularity: Design instruments, devices, and accessories for disassembly, repair, and recycling.

- Sustainability assessment: Use tools like Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to evaluate environmental impacts.

- Energy efficiency: Improve energy efficiency in all analytical activities.

- Service over product: Shift from owning analytical equipment to using analytical services.

- Stakeholder collaboration: Build alliances between academia, industry, governments, and organizations.

- Policy coherence: Develop policies that support and incentivize circular practices.

GAC vs. CAC: A Comparative Framework

The following table summarizes the core differences and synergies between the two frameworks.

Comparative Analysis of GAC and CAC

| Feature | Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) | Circular Analytical Chemistry (CAC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Minimizing environmental impact of analytical methods [25] | Transforming the entire analytical system into a closed-loop [25] |

| Economic Model | Aligned with linear economy (improving efficiency within a take-make-dispose model) [25] | Aligned with circular economy (eliminating the concept of waste) [25] |

| Core Scope | Laboratory practices, method design [24] | Entire life cycle of products, broad stakeholder alliance [25] |

| Key Objective | Reduce waste, energy, and toxicity of analytical processes [24] | Eliminate waste, circulate materials, and preserve resources [25] |

| View on Waste | Something to be minimized and properly managed [24] | A resource to be valorized and used as feedstock [25] |

| Typical Actions | Miniaturization, solvent replacement, direct analysis [24] | Product redesign, service-based models, industrial symbiosis [25] |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs for Method Transfer

Common Challenges and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution | Related Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| High solvent waste generation | Traditional Liquid-Liquid Extraction methods | Switch to Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) or other solventless techniques [26] | GAC 1, 7; CAC 2 |

| Poor method sensitivity after miniaturization | Incompatible detector or sample loss in micro-system | Re-optimize transfer lines, use a more sensitive detector, or employ a different micro-extraction phase [26] | GAC 5 |

| Difficulty validating a new green method | Complex sample matrix interfering with alternative solvent | Use matrix-matched calibration standards or apply the standard addition method [26] | GAC 11 |

| High energy consumption of instrumentation | Old equipment, non-optimized run times | Schedule instrument standby modes, upgrade to energy-efficient models, consolidate sequences [25] | GAC 9; CAC 9 |

| Analytical device failure; entire unit replaced | Designed for obsolescence; not repairable | Select manufacturers that support repair and provide spare parts; advocate for modular design [25] | CAC 7, 10 |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I start implementing circular practices if I only work in a lab and don't control instrument design? A1: You can contribute significantly by focusing on CAC Goals 1 and 2. Segregate and valorize laboratory waste (e.g., solvent recycling programs) [25], prioritize the use of re-manufactured or refurbished equipment, and choose suppliers that take back packaging or consumables for reuse and recycling [25].

Q2: Is there a conflict between GAC's principle of "design for degradation" and CAC's goal to "circulate materials"? A2: This is a nuanced but important point. CAC aims to keep materials at their highest utility for as long as possible. "Design for degradation" is a last resort for when a material can no longer be circulated and must safely re-enter the environment without causing harm [27]. The priority should be designing for durability, reuse, and recycling first [25].

Q3: We have validated a method using a toxic solvent. What is the safest approach to transfer it to a green solvent? A3: A systematic approach is key. First, use tools like the AGREEprep metric to assess the greenness of your current method and identify the worst-performing criteria [25]. Then, consult databases of alternative green solvents (e.g., water, bio-based solvents, ionic liquids) [28]. Finally, perform a rigorous method validation to ensure the new solvent system provides comparable accuracy, precision, and sensitivity.

Q4: What is the single most impactful change we can make in our analytical lab to be more sustainable? A4: While there is no single answer, one of the most impactful actions is source reduction (GAC Principle 2), often achieved through miniaturization (GAC Principle 5) [24] [26]. Reducing sample and reagent volumes by scaling down to micro-extraction techniques or microfluidic devices has a cascade effect, reducing solvent use, energy consumption, and waste generation simultaneously.

Essential Workflow for Transitioning to Greener Methods

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for transitioning from a traditional linear analytical process to an integrated circular system, incorporating key principles from both GAC and CAC.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Green and Circular Chemistry

Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Labs

| Reagent/Material | Function | Traditional Hazardous Alternative | Sustainability Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., Ethanol, Ethyl Lactate) | Extraction and Chromatography | Petroleum-derived solvents (e.g., Hexane, Chloroform) | Derived from renewable feedstocks; generally less toxic and biodegradable [28]. |

| Ionic Liquids | Solvents, Catalysts, Electrolytes | Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) | Negligible vapor pressure, reducing air pollution; often recyclable [28]. |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Extraction and Chromatography | Organic solvents in SFE and SFC | Non-toxic, non-flammable, and easily removed from the product; uses waste CO₂ [28]. |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers | Sample Preparation | Solvent-intensive Liquid-Liquid Extraction | Eliminates or drastically reduces solvent use; fibers are reusable [26]. |

| Recycled or Remanufactured Instruments | Analytical Equipment | Newly manufactured instruments | Reduces electronic waste and the resource intensity of manufacturing new equipment [25]. |

Building Your Green Toolkit: Strategies and Techniques for Sustainable Methodologies

The transfer of classical analytical methods to more sustainable practices represents a critical evolution in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Within this paradigm shift, Green Sample Preparation (GSP) has emerged as a guiding principle that prioritizes environmental responsibility while maintaining analytical performance. Sample preparation has traditionally been the most polluting step in analytical workflows, often consuming large quantities of organic solvents and generating substantial toxic waste [29]. The fundamental goal of GSP is to redesign these procedures to align with the twelve principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), which aim to reduce the environmental and health footprints of analytical activities [16].

The core innovations driving this transition center on four interconnected technological pillars: acceleration (reducing processing time), parallelization (handling multiple samples simultaneously), automation (minimizing manual intervention), and integration (combining multiple processing steps). These approaches collectively address the primary environmental drawbacks of traditional sample preparation—high solvent consumption, energy demand, waste generation, and operator risk—while enhancing analytical throughput and reproducibility [30] [31]. Within the context of method transfer to greener analytical techniques, implementing these principles allows laboratories to maintain the rigorous data quality required for pharmaceutical development while significantly advancing sustainability goals [16] [19].

The Ten Principles of Green Sample Preparation

The foundation of modern green sample preparation was established with the formulation of ten explicit principles by López-Lorente et al. [31]. These principles provide a comprehensive framework for assessing and improving the environmental profile of sample preparation methods:

- Use of Safe Solvents/Reagents: Prioritize non-toxic, biodegradable solvents to minimize environmental impact and health risks.

- Renewable, Recycled, and Reusable Materials: Source materials sustainably and implement systems for recycling and reuse.

- Minimized Waste Generation: Reduce the mass and toxicity of waste produced during preparation.

- Minimized Energy Demand: Optimize procedures to lower overall energy consumption.

- High Sample Throughput: Process multiple samples simultaneously to improve efficiency.

- Miniaturization: Scale down procedures to use smaller sample and reagent volumes.

- Procedure Simplification: Reduce the number of processing steps required.

- Automation: Implement automated systems to enhance reproducibility and safety.

- Operator Safety: Prioritize methods that protect analysts from hazardous exposures.

- Minimized Samples, Chemicals, and Materials: Use only necessary quantities of all resources.

These principles form an integrated system where improvements in one area often synergistically address deficiencies in others [32]. For instance, miniaturization (Principle 6) typically reduces waste generation (Principle 3) and energy demand (Principle 4), while automation (Principle 8) enhances operator safety (Principle 9) and enables higher sample throughput (Principle 5).

Quantitative Assessment: The AGREEprep Metric

To standardize the evaluation of sample preparation greenness, the AGREEprep metric was developed as the first dedicated tool for quantifying the environmental impact of sample preparation methods [32]. This open-source software tool evaluates methods against the ten GSP principles through ten assessment criteria, each scoring from 0 to 1, where 1 represents optimal green performance.

AGREEprep generates an intuitive circular pictogram that visually displays the overall score (0-1) at the center, surrounded by ten colored segments corresponding to each assessment criterion. This visualization allows researchers to quickly identify both strengths and weaknesses in their methods, facilitating targeted improvements. The tool has been applied to evaluate numerous official standard methods, revealing significant opportunities for greining: traditional Soxhlet extraction methods scored only 0.04-0.12, while official food analysis methods ranged from 0.05-0.22, and methods for trace metal analysis scored 0.01-0.36 [32]. These consistently low scores highlight the urgent need for modernizing standard protocols through the implementation of acceleration, parallelism, automation, and integration strategies.

Table 1: AGREEprep Evaluation Results for Official Standard Methods

| Method Category | Number of Methods Evaluated | Primary Techniques | AGREEprep Score Range | Key Deficiencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental Analysis (Organic) | 25 | Soxhlet extraction | 0.04 - 0.12 | Time-consuming, high solvent/energy use, multiple additional treatment steps |

| Food Analysis | 15 | Soxhlet extraction, maceration, digestion | 0.05 - 0.22 | Manual operations, time-consuming, toxic reagents, energy-intensive heating |

| Environmental Analysis (Inorganic) | 25 | Acid digestion, microwave-assisted extraction, SPE | 0.01 - 0.36 | Large amounts of mineral acids, energy-demanding instrumentation, lack of automation |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common GSP Implementation Challenges

FAQ 1: How can I maintain analytical sensitivity while reducing solvent volumes in sample preparation?

Challenge: Miniaturization approaches often raise concerns about maintaining adequate sensitivity for trace analysis, particularly in pharmaceutical impurity testing.

Solution: Implement integrated enrichment techniques alongside miniaturization. For example, in-line Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) coupled with LC-MS/MS enables both miniaturization and pre-concentration. As demonstrated in pesticide analysis, this approach achieved detection limits at ng/L levels while processing sample volumes as low as 5mL [29]. The configuration uses an automated column-switching valve with extraction cartridges that enrich analytes before transfer to the analytical system.

Experimental Protocol: On-line SPE-LC-MS-MS for Water Analysis

- Sample Loading: Acidify water sample with 0.2% formic acid and filter through 0.45µm cellulose filter.

- Extraction: Load 5mL sample onto Oasis HLB cartridge (20mm × 2.1mm i.d., 25µm particles) using auxiliary loading pump.

- Analyte Transfer: Switch valve position to align SPE cartridge with analytical flow path.

- Chromatographic Analysis: Desorb enriched analytes directly onto analytical column (e.g., Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18, 10cm × 2.1mm i.d., 3.5µm particles) using gradient elution from 10% B to 79% B in 8min (A = 0.05% formic acid in water, B = acetonitrile).

- Detection: Perform analysis with MS/MS detection using alternating positive/negative electrospray ionization and Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM).

This method achieves 10-12 fold sensitivity increase compared to direct injection while eliminating manual SPE procedures and reducing solvent consumption [29].

FAQ 2: What strategies can overcome the throughput limitations of traditional extraction methods?

Challenge: Conventional techniques like Soxhlet extraction require extensive processing times (often 6-24 hours), creating bottlenecks in analytical workflows.

Solution: Employ parallelization and automation through modern instrumentation. The SSM (Srun, Sbatch, Monitor) scheme demonstrates how computational parallelization can dramatically improve processing efficiency. In tests with FAST telescope data, this approach reduced processing time from 14 hours (traditional methods) to 5.5 hours while increasing CPU utilization from 52% to 89% [33]. Although developed for data processing, this model of command splitting and parallel execution is directly applicable to controlling automated sample preparation systems.

Experimental Protocol: Automated Parallelized Extraction Workflow

- Sample Management: Arrange samples in racks compatible with automated liquid handling systems.

- Command Splitting: Divide processing commands into discrete, parallel-executable tasks.

- Resource Allocation: Distribute tasks across multiple processing units (e.g., multi-probe liquid handlers, parallel extraction stations).

- Continuous Monitoring: Implement real-time monitoring of system resources and task completion.

- Data Integration: Automatically compile results from parallel processes into unified datasets.

For solid samples, automated parallel extraction systems can process multiple samples simultaneously using significantly reduced solvent volumes compared to traditional Soxhlet extraction [30].

FAQ 3: How can I reduce hazardous solvent use without compromising analyte recovery?

Challenge: Many official methods specify hazardous solvents like hexane, benzene, or chlorinated compounds that pose significant environmental and health risks [32].

Solution: Apply solvent substitution guidelines based on modern green chemistry principles. The CHEM21 solvent selection guide and related frameworks provide ranked alternatives based on environmental, health, and safety (EHS) criteria [16]. For example, cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) and ethyl acetate can replace hexane in many extractions, while bio-based solvents like dihydrolevoglucosenone (Cyrene) show promise for chromatographic applications [16].

Experimental Protocol: Solvent Replacement Strategy for Sample Preparation

- Identify Solvent Function: Determine the primary role of the solvent (extraction, dilution, cleaning).

- Consult Selection Guides: Reference CHEM21, ACS GCI, or ICH Q3C guidelines to identify safer alternatives with similar properties.

- Evaluate Compatibility: Assess chemical compatibility with samples, analytes, and instrumentation.

- Pilot Testing: Conduct small-scale recovery studies comparing traditional and alternative solvents.

- Method Validation: Fully validate method performance using green solvents following ICH guidelines.

FAQ 4: What approaches can streamline multi-residue analysis in complex matrices?

Challenge: Comprehensive analysis of multiple analyte classes in complex matrices like food, biological tissues, or environmental samples typically requires extensive sample preparation with multiple cleanup steps.

Solution: Implement integrated techniques that combine extraction and cleanup in a single platform. Gas phase extraction techniques like Dynamic Headspace (DHS) and Headspace Sorptive Extraction (HSSE) effectively isolate volatile and semi-volatile compounds from complex matrices without solvents [29]. For example, thermal desorption of vegetable oils enables determination of aldehydes, hydrocarbons, free fatty acids, vitamins, and sterols without the apolar triglyceride matrix interference.

Experimental Protocol: Gas Phase Stripping for Complex Matrices

- Sample Introduction: Place 10mg sample in glass microvial within thermal desorption unit.

- Thermal Extraction: Heat from 25°C to 250°C at 60°C/min under 100mL/min helium flow, maintain at 250°C for 20min.

- Analyte Focusing: Trap extracted compounds in PTV injector at -50°C.

- Thermal Desorption: Heat cryotrap at 12°C/s to 310°C (5min hold) with 1:10 split ratio.

- Chromatographic Analysis: Separate on HP-5MS column (30m × 0.25mm i.d., 0.25µm df) with temperature program from 50°C to 300°C at 8°C/min.

- Detection: Analyze by MS with repeatability typically <10% RSD [29].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for GSP Implementation

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Green Sample Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Traditional Substance | Function in GSP | Green Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (Cyrene) | DMF, DMAc, NMP | Sample dissolution, extraction | Renewable feedstock, biodegradable, reduced toxicity |

| Ethyl acetate | Hexane, dichloromethane | Liquid-liquid extraction | Lower toxicity, better environmental profile |

| Cyclopentyl methyl ether (CPME) | THF, diethyl ether | Extraction solvent | Higher stability, lower peroxide formation, reduced toxicity |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Sorbents | Liquid-liquid extraction | Analyte enrichment and cleanup | Reduced solvent consumption, automation compatibility |

| Ionic Liquids | Organic solvents | Extraction media | Tunable properties, low volatility, potential reusability |

| Supercritical CO₂ | Organic solvents | Extraction fluid | Non-toxic, easily removed, tunable solvation power |

Workflow Visualization: GSP Method Transfer Strategy

Diagram 1: GSP Method Transfer Workflow

Diagram 2: GSP Core Principles Interconnection

The transition to greener sample preparation methodologies represents both an environmental imperative and a practical opportunity for enhancement of pharmaceutical analysis. By systematically applying the principles of acceleration, parallelism, automation, and integration through the structured framework outlined in this technical guide, research organizations can achieve substantial improvements in both sustainability metrics and operational efficiency. The troubleshooting scenarios and implementation strategies presented provide a roadmap for overcoming common barriers to GSP adoption.

As regulatory bodies increasingly emphasize environmental responsibility, the proactive transfer of analytical methods to greener alternatives positions drug development organizations at the forefront of sustainable science. By embracing the GSP framework and utilizing assessment tools like AGREEprep, the pharmaceutical industry can maintain the rigorous analytical standards required for product quality while significantly reducing its environmental footprint—creating a win-win scenario for both business objectives and planetary health [19] [32]. The continued collaboration between academic researchers, instrument manufacturers, and standardization bodies will be essential to further refine and disseminate these approaches across the global analytical community [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most practical green solvents I can use today to replace acetonitrile in reversed-phase HPLC? Replacing acetonitrile (ACN) is a primary goal for greening HPLC methods. Several practical alternatives exist, each with specific advantages and considerations for method transfer [34] [35] [36].

- Ethanol is a leading candidate. It is readily available, often cost-effective, and offers good chromatographic performance. Its main limitation is a higher UV cut-off (~210 nm), which can affect sensitivity for analytes that only absorb at low wavelengths [34].

- Carbonate Esters (e.g., dimethyl carbonate, propylene carbonate) are another green alternative. However, they are only partially miscible with water and require a co-solvent (like a small amount of methanol or ACN) to maintain a single-phase mobile phase throughout the run. Ternary phase diagrams are essential tools for optimizing these solvent blends [35].

- Water-based Mobile Phases represent the greenest option. In some cases, methods can be redesigned to use only aqueous mobile phases, particularly for the analysis of water-soluble compounds, thereby eliminating organic solvent use entirely [36].

Q2: My new hydrophobic DES is too viscous for easy pipetting. How can I manage this in a sample preparation workflow? High viscosity is a common challenge with certain Deep Eutectic Solvents (DES) and can be managed through simple adjustments to your protocol [37].

- Temperature Control: Gently warming the DES can significantly reduce its viscosity, making it easier to handle. The paraben extraction method, for instance, used a temperature of 40 °C during the desorption step [37].

- Ultrasound Assistance: Coupling the method with ultrasound-assisted desorption or extraction not only helps in handling viscous liquids but also improves mass transfer and extraction efficiency. A 30-minute sonication step has been successfully employed [37].

- Dilution: In some cases, minimal dilution with water or another green solvent can reduce viscosity without critically compromising the extraction efficiency.

Q3: I'm transferring a method from HPLC to UHPLC to save solvent. What are the key parameters I must adjust to maintain performance? Transferring a method to UHPLC is an excellent strategy for reducing solvent consumption and increasing throughput. Key parameters to focus on include [35] [36] [16]:

- Particle Size and Pressure: UHPLC uses columns packed with smaller particles (often sub-2 µm), which dramatically increases operating pressures. Ensure your UHPLC system can handle the required pressure.

- Column Dimensions: Use shorter columns with smaller internal diameters. Narrow-bore columns (e.g., ≤2.1 mm i.d.) can reduce mobile phase consumption by up to 90% compared to standard 4.6 mm columns [36].

- Flow Rate and Gradient: Scale down the flow rate proportionally to the reduction in column cross-sectional area. The gradient profile must also be adjusted to maintain the same linear velocity and separation selectivity.

- System Volume: The reduced dwell volume of UHPLC systems can affect gradient delay times, which may require fine-tuning for precise retention times.

Q4: Are the sensitivity and peak shape comparable when using green solvents like ethanol versus traditional acetonitrile? In many cases, yes, but with important caveats. Ethanol can provide comparable efficiency and resolution to acetonitrile [34]. The primary trade-off is often sensitivity due to ethanol's higher UV cut-off, which may necessitate using a higher detection wavelength [34] [35]. Peak shape is generally maintained, though the different solvent strength and viscosity of green solvents like carbonate esters can slightly alter selectivity and backpressure, requiring re-optimization of the mobile phase composition for optimal performance [35].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Recovery or Selectivity with Green Sorbents

Application Context: Solid-phase extraction (SPE) for the analysis of parabens in urine, transferring from a C18 sorbent to a greener alternative [37].

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low analyte recovery | Sorbent-analyte interactions too weak. | Test different green sorbent materials (e.g., PSA, Florisil) to find one with stronger selective affinity [37]. |

| High matrix co-extraction | Sorbent lacks selectivity, retaining interfering compounds. | Optimize the composition and volume of the green desorption solvent. Incorporate a wash step with a weak solvent to remove interferences before elution. |

| Inconsistent results | Sorbent bed channeling or insufficient conditioning. | Ensure the sorbent is properly conditioned with a compatible solvent before sample loading. Maintain a consistent flow rate during loading and elution. |

Experimental Protocol: H-NADES-based SPE for Parabens [37]

- Sorbent Conditioning: Load 50 mg of C18 sorbent into a cartridge. Condition with a suitable solvent.

- Sample Loading: Load the processed urine sample (e.g., buffered with phosphate) onto the sorbent.

- Washing: Use a small volume of a weak aqueous solvent to remove weakly retained matrix components.

- Elution: Desorb the target parabens using 200 µL of a hydrophobic NADES (prepared from DL-menthol and acetic acid in a 1:2 molar ratio).

- Ultrasound Assistance: Place the cartridge in an ultrasonic bath for 30 minutes at 40 °C to facilitate desorption.

- Analysis: Collect the eluent and analyze by HPLC-UV. This method reduced solvent volume and showed an AGREE greenness score of 0.70 [37].

Problem: High Backpressure or Peak Tailing with Green Mobile Phases

Application Context: Reversed-phase LC method transfer to green solvents like ethanol or carbonate esters [34] [35].

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Abnormally high system pressure | Mobile phase viscosity is too high. | Reduce the percentage of the viscous green solvent (e.g., ethanol, propylene carbonate). Consider increasing the column temperature to lower mobile phase viscosity [35] [36]. |

| Peak tailing or splitting | Silanol interactions with basic analytes; mobile phase pH issues. | Use a mobile phase additive (e.g., low concentration of ionic liquids) to mask silanol groups. Ensure the mobile phase pH is optimally buffered for your analytes [36]. |

| Baseline drift or noise | High UV absorbance of the green solvent. | Increase the detection wavelength above the solvent's UV cut-off. Use a reference wavelength to balance the baseline if available [35]. |

Experimental Protocol: Method Transfer to an Ethanol-Water Mobile Phase [34]

- Initial Scouting: Start with an isocratic method using an ethanol-water blend (e.g., 7:93 v/v for highly polar compounds) on a C18 column [34].

- Temperature Optimization: Set the column temperature between 30-40 °C to manage backpressure from the more viscous ethanol-water mixture.

- Gradient Re-optimization: If transferring a gradient method, re-optimize the gradient profile to account for the different elution strength of ethanol compared to ACN. The starting percentage of ethanol will likely need to be higher than that of ACN.

- Performance Check: Inject a standard mixture to check for adequate resolution, peak shape, and backpressure. The backpressure for a 250 mm x 4.6 mm column at 1 mL/min and 38°C with an ethanol-water mobile phase should be approximately 106 bar [34].

Problem: Inadequate Sensitivity in Miniaturized LC Methods

Application Context: Transferring an analytical-scale metabolomics or exposomics method to micro- or nano-flow LC to enhance sensitivity for trace-level analysis [38].

| Observation | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Lower than expected sensitivity | Sample loss in transfer lines or trapping column. | Ensure all connections are zero-dead-volume and check the trapping efficiency on the miniaturized platform. |

| Poor peak shape/repeatability | Column overload or matrix effects. | Dilute the sample or reduce the injection volume. Improve sample clean-up to reduce matrix interference [38]. |

| Chemical noise/contamination | System carryover from previous injections. | Implement more rigorous washing steps between injections, especially with biological matrices. Use longer gradients if rapid gradients are causing issues [38]. |

Experimental Protocol: Sensitivity Assessment for LC Miniaturization [38]

- Platform Comparison: Analyze the same spiked plasma extract (e.g., at 1 μg/L for pharmaceuticals/mycotoxins) on three different LC setups: analytical flow (~250 μL/min), micro-flow (~57 μL/min), and nano-flow (~0.3 μL/min).

- Standardized Injection: Keep the injection volume constant across platforms to directly compare sensitivity gains from reduced sample dilution.

- Data Analysis: Compare the signal intensities for a panel of small molecules. Micro-flow LC can offer a median 80-fold sensitivity gain over nano-flow for complex small-molecule analysis in plasma, making it a robust compromise [38].

- Assess Coverage: Evaluate not just sensitivity but also the number of features detected (e.g., in a non-targeted metabolomics workflow) to ensure the miniaturized platform does not unduly restrict the investigated chemical space.

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

Method Transfer to Greener Analytical Techniques

Hydrophobic NADES Preparation & Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Green Solvents and Sorbents for Chromatography

| Reagent/ Material | Function & Green Credential | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Replaces acetonitrile or methanol in reversed-phase mobile phases. Biobased, biodegradable, low toxicity. | Higher viscosity increases backpressure; UV cut-off ~210 nm. Best for detection at higher wavelengths [34] [36]. |

| Dimethyl Carbonate | Green organic solvent for mobile phases. Biodegradable and low toxicity. | Partially miscible with water; requires a co-solvent (e.g., methanol). Use ternary phase diagrams for formulation [35]. |

| Hydrophobic NADES (e.g., Menthol:Acetic Acid) | Green desorption solvent for SPE. Low toxicity, biodegradable components. | Viscous; requires ultrasound assistance and heating (e.g., 40°C) for efficient desorption. Molar ratio is critical [37]. |

| C18 Sorbent | Conventional reversed-phase sorbent for SPE. | Serves as a benchmark. Greener protocols can be developed by combining it with green elution solvents like NADES [37]. |

| Superficially Porous Particle (SPP) Columns | UHPLC columns for reduced solvent consumption. | Lower diffusion paths enhance efficiency, allowing shorter columns and faster runs, reducing solvent waste and energy use [35]. |

Quantitative Comparison of LC Miniaturization Strategies

| Parameter | Analytical Flow LC | Micro-Flow LC | Nano-Flow LC |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Flow Rate | 250 - 1000 µL/min [38] | ~57 µL/min [38] | ~0.3 µL/min [38] |

| Solvent Consumption / Run | High (mLs) | Moderate (100s of µL) | Very Low (10s of µL) |

| Relative Sensitivity | Baseline | 80-fold median gain vs. nano-flow in plasma [38] | High, but compound-dependent [38] |

| Robustness & Ease of Use | High | Best Compromise [38] | Lower (susceptible to clogging) [38] |

| Ideal Application | Routine, high-throughput analysis | Wide-target small-molecule trace bioanalysis; global metabolomics [38] | Volume-limited samples (e.g., single-cell analysis) |

FAQs: Greener Method Transfer

Q1: What are the primary environmental and economic benefits of transferring from traditional solvent-based synthesis to mechanochemistry?

The primary benefits are a dramatic reduction in solvent waste and a significant increase in energy efficiency. Traditional solution reactions often require substantial energy for solvent removal, heating, and cooling. Mechanochemistry, conducted with no or minimal solvent, largely eliminates this energy demand [39]. Furthermore, it avoids the environmental and economic costs associated with the purchase, disposal, and treatment of large quantities of organic solvents, aligning with green chemistry principles [39] [40].

Q2: My mechanochemical reaction in a ball mill has an unacceptably long induction period. What factors should I investigate?

A prolonged induction period can be linked to several factors related to the mechanochemical setup and environment. You should investigate:

- Atmospheric Humidity: Even small amounts of water, either intentionally added as Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) or unintentionally absorbed from humid air when the reactor is opened, can significantly accelerate or alter the reaction pathway [41].

- Polymorphic Form of Reactants: The starting polymorph of your reactants can impact the duration of the induction period, as some solid forms are more readily activated by mechanical force than others [41].

- Mechanical Frequency/Energy: The frequency of mechanical impacts in your mill is critical. Induction periods are often shorter in high-energy or high-frequency milling conditions [41].

Q3: When attempting "on-water" reactions, my water-insoluble substrates do not appear to react. What could be wrong?

The success of "on-water" reactions relies on the creation of a large interfacial area between the insoluble organic substrates and water. If no reaction is observed, the issue is likely inefficient mixing. You must ensure vigorous stirring or agitation to create a fine suspension and maximize the contact area at the oil-water interface, which is where the reaction acceleration occurs [42].

Q4: How scalable are mechanochemical methods for industrial pharmaceutical production, and what technologies exist?

Traditional batch mechanochemical methods like ball milling face scalability challenges. However, continuous-flow mechanochemistry has emerged as a solution for industrial applications. Twin-screw extrusion (TSE) is a leading technology that provides the necessary shear forces and mixing for reactions while enabling precise temperature control and kilogram-per-hour throughputs, making it suitable for the continuous manufacturing of peptides and other pharmaceuticals [43] [44].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Common Mechanochemical Synthesis Issues

- Problem: Inconsistent results between different milling sessions or laboratories.

Solution: The field is moving towards standardizing experimental protocols. To ensure reproducibility, always report and control key variables such as grinding frequency, ball-to-powder ratio, milling material (e.g., stainless steel, zirconia), and atmospheric conditions [43].

Problem: The reaction forms a sticky paste or cakes to the walls of the jar.

Solution: Caking can remove material from the active milling zone. The protocol may require intermittent interruption to scrape down the jar. Alternatively, using a small amount of a grinding additive (e.g., NaCl) or employing Liquid-Assisted Grinding (LAG) with a minimal, catalytic amount of solvent can improve mixture homogeneity and prevent caking [41].

Problem: Difficulty in monitoring reaction progress or identifying intermediates.

- Solution: Implement in situ monitoring techniques. Real-time analysis using synchrotron X-ray diffraction or Raman spectroscopy through polymer jar windows allows for the observation of reaction kinetics and intermediate phases without interrupting the process [43] [41].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting "On-Water" and Micellar Chemistry Reactions

- Problem: Low yield in a Suzuki-Miyaura coupling performed in water using micellar chemistry.

Solution: First, verify that you are using a designed surfactant like TPGS-750-M, which forms the nanoreactors essential for solubilizing substrates and catalysts [45]. Next, investigate catalyst loading; a key advantage of micellar chemistry is that it often allows for a reduction in catalyst loading (e.g., from 5 mol% to 1 mol%) while maintaining or even improving performance [45].

Problem: Reaction in water does not achieve the same selectivity as in organic solvent.

- Solution: Do not assume this is a failure. The unique environment of the micelle can alter selectivity. For example, an amide coupling in water has been shown to improve regioselectivity and suppress the formation of a pivaloyl byproduct common in classical organic solvents [45]. Characterize your product thoroughly, as you may have achieved a more favorable outcome.

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Mechanochemical Synthesis of a Pharmaceutical Cocrystal via Ball Milling

This protocol outlines the solvent-free synthesis of a cocrystal to improve the solubility of a low-solubility Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) [39].

1. Materials and Setup

- API (e.g., a BCS Class II drug)

- Coformer (e.g., a GRAS-listed carboxylic acid)

- High-energy ball mill (e.g., Retsch MM400 or similar)

- Milling jar (stainless steel or zirconia)

- Milling balls (same material as jar)

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Pre-weigh the API and coformer in a stoichiometric ratio (typically 1:1) and add them to the milling jar.

- Step 2: Add the milling balls to the jar, ensuring an appropriate ball-to-powder ratio (e.g., 20:1 to 40:1).

- Step 3: Secure the jar in the mill and process for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-90 minutes) at a fixed frequency (e.g., 30 Hz).

- Step 4: After milling, carefully open the jar and collect the solid product for analysis.

3. Workflow Diagram

Protocol 2: Continuous Dipeptide Synthesis via Twin-Screw Extrusion (TSE)

This protocol describes a green, continuous method for peptide bond formation as an alternative to traditional Solid-Phase Peptide Synthesis (SPPS) [44].

1. Materials and Setup

- Electrophile: e.g., Boc-Val-NCA or Boc-Val-NHS

- Nucleophile: e.g., Leu-OMe HCl

- Base: e.g., Sodium Bicarbonate

- Laboratory-scale co-rotating twin-screw extruder with multiple temperature zones.

2. Procedure

- Step 1: Pre-blend the electrophile, nucleophile, and base in an equimolar ratio.

- Step 2: Set the temperature profile of the extruder barrel zones. A typical profile might be: Zone A (Feed): 25°C, Zone B (Mixing): 40-60°C, Zone C (Reaction): 60-80°C.

- Step 3: Feed the powder blend into the extruder hopper at a fixed feed rate.

- Step 4: Collect the solid strand extruded from the die. Conversion can be monitored by HPLC.

3. Key Optimization Parameters for TSE Peptide Synthesis [44]

| Parameter | Typical Range or Condition | Impact on Reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Level | Solvent-free to 1% (w/w) acetone | Higher levels can improve conversion but reduce green credentials. |

| Temperature Profile | 25°C to 80°C across zones | Precise thermal control is critical for heat-sensitive substrates. |

| Amino Acid Ratio | 1:1 (Electrophile:Nucleophile) | Eliminates excess reagent waste common in SPPS. |

| Screw Speed | 100 - 300 rpm | Affects residence time and shear forces. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Greener Synthesis Experiments

| Reagent/Technology | Function in Energy-Conscious Synthesis |

|---|---|