Green Spectroscopic Techniques: Principles, Applications, and Sustainable Practices for Pharmaceutical Analysis

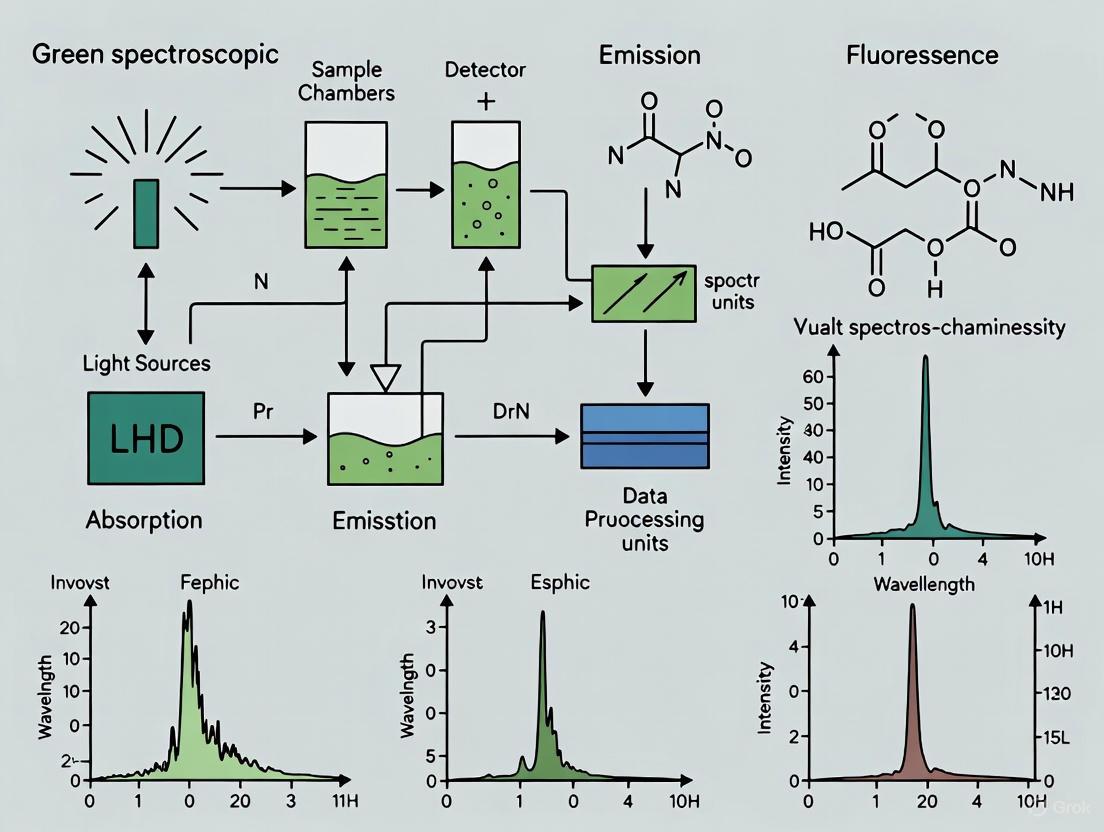

This article provides a comprehensive overview of green spectroscopic techniques, a cornerstone of sustainable analytical chemistry in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Green Spectroscopic Techniques: Principles, Applications, and Sustainable Practices for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of green spectroscopic techniques, a cornerstone of sustainable analytical chemistry in pharmaceutical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), including the 12 principles and key metrics like AGREE and MoGAPI for environmental impact assessment. The scope extends to detailed methodologies of solventless and minimally invasive techniques such as FT-IR, NIR, and Raman spectroscopy, illustrated with applications in drug quantification and impurity profiling. The content further addresses troubleshooting spectral interference and optimization strategies via computational approaches like Greenness-by-Design (GbD). Finally, it covers the validation of these methods against ICH guidelines and comparative analyses with traditional techniques, highlighting their analytical and environmental superiority. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals seeking to implement sustainable, efficient, and compliant analytical practices.

The Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Spectroscopic Foundations

Core Tenets of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC)

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) represents a fundamental paradigm shift within chemical analysis, dedicated to minimizing the environmental footprint and health risks associated with traditional laboratory practices [1]. Evolving from the broader concepts of green chemistry, GAC has matured into a specialized discipline with defined principles and measurable outcomes [2]. This transformation aligns analytical chemistry with global sustainability goals, challenging the field to reconcile its crucial role in determining the composition of matter with its historical reliance on energy-intensive processes, non-renewable resources, and waste generation [3]. The adoption of GAC is not merely an ethical choice but a necessary evolution, fostering innovation that reduces environmental impact while maintaining, and often enhancing, analytical performance [4].

Foundational Principles of GAC

The framework for GAC is built upon adaptations of the original 12 Principles of Green Chemistry, tailored specifically to the realities of analytical laboratories [2] [5]. These principles provide a strategic roadmap for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical methods.

The core tenets can be summarized as follows:

- Direct Analytical Techniques: Prioritizing methods that require minimal sample preparation and avoid derivatization [5].

- Integration of Analytical Processes: Embedding steps like sampling, sample preparation, and measurement into a single, streamlined apparatus to minimize material loss and contamination [5].

- Automation and Miniaturization: Employing automated systems and scaled-down processes to reduce reagent consumption, waste generation, and operator exposure to hazards [3] [4].

- Minimization of Reagents and Derivatives: Avoiding additional reagents where possible to reduce waste and complexity [4].

- Energy Management: Reducing total energy consumption by utilizing alternative energy sources (e.g., ultrasound, microwaves) and performing analyses at ambient temperature when feasible [3] [4].

- Toxic Reagent Substitution: Replacing hazardous solvents and reagents with safer, bio-based, or innocuous alternatives (e.g., water, supercritical CO₂, ionic liquids) [4] [5].

- Real-Time, In-Process Monitoring: Developing methods for direct analysis to prevent pollution at its source [4].

- Waste Minimization and Treatment: Preventing waste generation at the outset and properly treating any waste that is produced [5].

- Multi-Analyte Determinations: Maximizing information obtained from a single analysis to improve efficiency and throughput [3].

- Operator Safety: Ensuring a safe working environment through method design that minimizes exposure to hazardous chemicals [3].

- Reduction of Sample Number: Applying rational strategies and chemometric tools to minimize the number of samples required without compromising data quality [6].

A critical concept in modern GAC is White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), proposed as a holistic expansion. WAC balances the three pillars of analytical quality (red), ecological impact (green), and practical/economic practicality (blue) [2]. A perfect white method demonstrates synergy and harmony among these three criteria, ensuring that a method is not only green but also functionally viable and analytically sound for routine use [2].

Quantitative Metrics for Assessing Greenness

The principles of GAC are operationalized through a suite of greenness assessment tools. These metrics allow for the objective evaluation, comparison, and validation of the environmental friendliness of analytical methods.

Table 1: Overview of Key Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric Name | Type of Output | Key Assessed Parameters | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [6] | Qualitative (Pictogram) | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste amount. | Simple, provides immediate general information. | Qualitative only; limited scope. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [6] | Semi-Quantitative (Score out of 100) | Reagent hazards, energy consumption, waste amount. | Provides a total score; easy to interpret. | Penalty points assignment can be subjective. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [5] | Semi-Quantitative (Pictogram) | All stages of analysis, from sampling to waste. | Comprehensive, covers the entire method lifecycle. | Complex pictogram; output is not a single score. |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness metric) [5] [6] | Quantitative (Score 0-1) | The 12 principles of GAC. | Comprehensive, user-friendly software available. | Requires specialized software for full use. |

| AGREEprep [3] [5] | Quantitative (Score 0-1) | 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation. | Specific to sample preparation; provides a clear score. | Focused only on the sample prep stage. |

| RGB Model [5] [6] | Quantitative (Scores for Red, Green, Blue) | Combines GAPI (green), performance (red), and practicality (blue). | Balances greenness with functionality (a WAC tool). | More complex to calculate and interpret. |

The application of these tools in practice is demonstrated in a 2025 study that developed a solvent-free FT-IR method for quantifying antihypertensive drugs [7]. The method's greenness was evaluated using AGREEprep, which yielded a high score of 0.8, and the RGB model, which delivered a total score of 87.2 [7]. These scores quantitatively confirmed the method's superior environmental profile compared to a traditional HPLC method, which would typically consume significant volumes of organic solvents [7].

Key Strategies and Innovations in GAC

Green Sample Preparation (GSP)

Sample preparation is often the most resource-intensive step. GSP strategies focus on:

- Miniaturization and Microextraction: Using dramatically smaller sample and solvent volumes [3].

- Alternative Energy Sources: Applying ultrasound or microwave energy to accelerate mass transfer and enhance extraction efficiency while consuming less energy than traditional heating [3].

- Parallel Processing and Automation: Treating multiple samples simultaneously and employing automated systems to increase throughput, improve reproducibility, and reduce operator exposure [3].

- Solvent-Free Techniques: Employing methods like solid-phase microextraction (SPME) or using the FT-IR pressed pellet technique, which eliminates toxic solvent use entirely [4] [7].

Green Instrumentation and Techniques

- Spectroscopic Techniques: FT-IR and UV-Vis spectrophotometry are recognized as green core techniques due to their minimal requirements for solvents and sample preparation, speed of analysis, and low energy consumption [2] [7].

- Miniaturized and Portable Devices: Lab-on-a-chip and portable sensors enable on-site analysis, eliminating the environmental costs of sample transport and large, energy-intensive lab equipment [4].

- Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC): Using supercritical CO₂ as the mobile phase代替 traditional organic solvents [4].

- Energy-Efficient Instrumentation: Modern instruments like UPLC are designed for higher efficiency, lower solvent consumption, and shorter run times compared to conventional HPLC [6].

The Role of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

A truly sustainable approach requires a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) perspective, which evaluates the environmental impact of an analytical method across its entire life cycle—from the extraction of raw materials for instrument and solvent production to energy consumption during operation and final waste disposal [4]. This systemic view helps avoid "burden shifting," where solving one environmental problem creates another [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Green FT-IR Method

The following protocol, adapted from a 2025 study, exemplifies the application of GAC principles for the simultaneous quantification of amlodipine besylate (AML) and telmisartan (TEL) in pharmaceutical tablets using FT-IR spectroscopy [7].

Methodology

- Principle: The method is based on the direct correlation between the concentration of an analyte and the area under its specific absorption band in the IR spectrum (Beer-Lambert law) [7].

- Materials and Reagents:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs): AML and TEL reference standards.

- Potassium Bromide (KBr): High-purity, IR-grade, used as the matrix for preparing solid pellets.

- Tablet Formulations: Commercial tablets containing the fixed-dose combination.

- Hydraulic Press: For compressing the powder mixture into transparent pellets.

- FT-IR Spectrometer: Equipped with a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector.

- Analytical Balance, Agate Mortar and Pestle, Spatula.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectrometer | Instrument for acquiring infrared absorption spectra of the samples. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | An IR-transparent matrix used to prepare solid pellets for analysis, eliminating the need for solvents. |

| Hydraulic Press | Applies high pressure to the KBr-sample mixture to form a solid, transparent pellet suitable for IR transmission measurements. |

| AML & TEL Standards | Provide known concentrations of the analytes for constructing the calibration curve, enabling quantitative analysis. |

Experimental Workflow

- Sample Preparation:

- Weigh accurately 1-2 mg of the standard (AML or TEL) or ground tablet powder.

- Mix thoroughly with 100-200 mg of dry KBr powder in an agate mortar using a pestle.

- Transfer a portion of the homogeneous mixture into a pellet die and compress under vacuum at ~10 tons of pressure for 2-3 minutes to form a clear, transparent pellet.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Place the pellet in the FT-IR spectrometer holder.

- Acquire the transmission spectrum in the mid-IR range (e.g., 4000-400 cm⁻¹) with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹.

- Convert the acquired transmittance spectra into absorbance spectra using the instrument's software.

- Calibration Curve:

- Prepare pellets with standard solutions covering a range of concentrations (e.g., 0.2-1.2% w/w for each API in KBr).

- For AML, measure the area under the curve (AUC) for the characteristic R-O-R stretching vibration band at 1206 cm⁻¹.

- For TEL, measure the AUC for the characteristic C-H out-of-plane bending vibration band at 863 cm⁻¹.

- Plot the AUC against the corresponding concentration for each drug to construct the calibration curve.

- Analysis of Tablet Formulation:

- Prepare a pellet from the ground tablet powder as described.

- Record the FT-IR spectrum and measure the AUC at the two specific wavenumbers.

- Use the respective calibration curves to determine the concentration of AML and TEL in the tablet.

Greenness Assessment and Validation

The described FT-IR method was validated as per ICH guidelines, demonstrating accuracy, precision, specificity, and linearity [7]. Its greenness was quantitatively evaluated against a reported HPLC method, with results summarized below:

Table 3: Comparative Greenness Assessment of FT-IR vs. HPLC Method [7]

| Analytical Method | MoGAPI Score (Higher is Greener) | AGREEprep Score (1.0 is Ideal) | RGB Total Score (Higher is Better) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Developed FT-IR Method | 89 | 0.8 | 87.2 |

| Reported HPLC Method | Not Reported (Inferred lower) | Not Reported (Inferred lower) | Not Reported (Inferred lower) |

The high scores confirm the method's alignment with GAC principles, primarily due to its solvent-free nature, minimal waste generation, and reduced energy requirements compared to chromatography-based methods [7].

Green Analytical Chemistry has moved from a theoretical concept to an essential, actionable framework guided by clear principles and measurable metrics. The core tenets of GAC—minimizing waste and toxicity, enhancing energy efficiency, and prioritizing safety—are successfully implemented through strategies like miniaturization, solvent substitution, and direct analysis. The case of the green FT-IR protocol demonstrates that it is possible to develop analytical methods that are both environmentally superior and analytically excellent. As the field evolves, the integration of comprehensive lifecycle thinking and the balanced perspective of White Analytical Chemistry will be crucial for driving innovation and ensuring that analytical chemistry continues to play its vital role in a sustainable future.

The Twelve Principles of GAC and Their Adaptation for Spectroscopy

The foundational inspiration for Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) stems from the broader concept of sustainable development and green chemistry, which was formally interpreted by Anastas in 1999 [2]. The field of GAC itself emerged as a distinct concept in the year 2000, born from green chemistry with a specific focus on the contribution of analytical chemists to enhance laboratory practices [2]. The core mission of GAC is to minimize the negative impacts of analytical procedures on human safety, human health, and the environment [8]. This involves critical assessment and modification of all aspects of an analysis, including the reagents consumed, sample collection and processing, instrumentation, energy consumption, and the quantities of hazardous waste generated [8].

In an analytical context, the development of GAC should be seen as a stimulus for improving the field. The discipline's most significant challenge lies in finding a balance between improving the quality of analytical results and enhancing the methods' green credentials [2]. While the original Twelve Principles of Green Chemistry were developed by Anastas and Warner in 1998, they were primarily created to meet the needs of synthetic chemistry, meaning only some were directly applicable to analytical chemistry [2]. To address this, Gałuszka et al. updated these principles in 2013 to be fully utilized in Green Analytical Chemistry, providing a tailored road map for analysts [2].

The adoption of GAC principles is particularly relevant in fields like pharmaceutical analysis, where analytical processes are used at multiple stages, from quality assurance of starting materials and finished products to drug kinetics and stability testing [2]. The selection of an analytical technique is a pivotal decision point for implementing GAC. Among available options, spectroscopic techniques often present inherent green advantages by reducing or eliminating solvent use, simplifying sample preparation, and minimizing waste generation, positioning them as strong candidates for developing sustainable analytical methods [2] [7].

The Twelve Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The following table synthesizes the Twelve Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry, their core objectives, and specific adaptations for spectroscopic techniques.

Table 1: The Twelve Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Their Spectroscopic Adaptations

| Principle | Core Objective | Adaptation for Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Direct Analysis | Eliminate sample treatment to avoid using reagents and generating waste. | Using non-destructive techniques like Near-Infrared (NIR) or Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) for direct measurement of solid samples [2] [7]. |

| 2. Energy Reduction | Minimize energy consumption during analysis. | Utilizing instrumentation with low energy requirements and employing techniques that operate at ambient temperature without extensive heating or cooling. |

| 3. Green Reagents & Solvents | Use safer, bio-based, or less toxic chemicals. | Prioritizing solventless methods (e.g., KBr pellets in FT-IR) or using water and ethanol instead of toxic organic solvents [7]. |

| 4. Miniaturization | Scale down analytical devices and sample sizes. | Developing micro-spectroscopic cells and using micro-sampling techniques to reduce reagent and sample volume [2]. |

| 5. Real-time Analysis | Perform measurements in situ to prevent sample transport and preservation. | Employing portable spectrometers for on-site, in-field analysis, enabling immediate results [2]. |

| 6. Automation | Integrate automated systems to enhance efficiency and safety. | Implementing auto-samplers and automated data analysis workflows in hyphenated spectroscopic systems. |

| 7. Derivatization Avoidance | Eliminate steps that use additional reagents to make a compound detectable. | Choosing spectroscopic techniques (e.g., UV-Vis, fluorescence) that directly measure the native analyte without chemical modification [9]. |

| 8. Sample Waste Minimization | Generate minimal waste post-analysis. | Spectroscopic methods are often non-destructive, allowing sample re-use, or generate negligible waste compared to chromatographic methods [7]. |

| 9. Integration of Methods | Combine multiple analytical steps into a single, streamlined process. | Hyphenating techniques like microscopy-FT-IR or chromatography-spectroscopy for direct analysis without intermediate handling. |

| 10. Safe Methodology | Ensure the safety of the operator throughout the analytical process. | Using sealed measurement cells to contain volatile substances and designing instrumentation with safety interlocks. |

| 11. Waste Management | Properly treat or recycle waste generated. | The minimal waste from many spectroscopic methods simplifies management; any waste produced should be non-toxic and easily treatable. |

| 12. Choice of Multi-analyte Methods | Prefer methods that can determine multiple components simultaneously. | Applying chemometrics to vibrational spectra (e.g., FT-IR) for the simultaneous quantification of multiple drugs in a mixture [2] [7]. |

Greenness Assessment Metrics for Spectroscopic Methods

To evaluate how well an analytical method aligns with GAC principles, several greenness assessment metrics have been developed. These tools provide a structured framework for evaluating and comparing the environmental impact of analytical procedures [2] [8].

Table 2: Key Greenness Assessment Metrics for Analytical Methods

| Metric Tool | Description | Key Features & Output |

|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environment Methods Index) [10] [8] | An early, simple tool that uses a pictogram with four quadrants to indicate whether criteria for Persistence, Toxicity, Corrosivity, and Waste are met. | Pros: Easy to use and comprehend.Cons: Only qualitative (pass/fail); lacks granularity [10]. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [10] [8] | A semi-quantitative tool that assigns penalty points for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste. The final score indicates greenness. | Output: A numerical score; >75 = excellent greenness, <50 = unacceptable greenness [10]. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [10] [8] | A more comprehensive qualitative tool that uses a pictogram with five pentagrams to evaluate the entire analytical process from sampling to final determination. | Pros: More detailed than NEMI.Cons: Still qualitative; does not assign a numerical score [8]. |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [10] [8] | A software-based tool that evaluates all 12 GAC principles, assigning a score from 0-1 for each. | Output: A circular pictogram with 12 sections, each colored and scored, with a total score in the center. It is one of the most comprehensive tools [10]. |

| GEMAM (Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods) [8] | A newly proposed (2025) metric that is simple, flexible, and comprehensive. It is based on both the 12 GAC principles and 10 factors of green sample preparation (GSP). | Output: A pictogram with a central hexagon showing the overall score (0-10) and six surrounding hexagons for key dimensions (Sample, Reagent, Instrument, etc.) [8]. |

The Evolution to White Analytical Chemistry (WAC)

A significant evolution beyond GAC is the concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), proposed in 2021 [10]. WAC serves as a proper expansion of GAC, designed to balance functionality with sustainability. While GAC is primarily eco-centric, WAC integrates three equally important dimensions, modeled on the RGB color model [2] [10]:

- Green: Represents the environmental impact and encompasses GAC principles.

- Red: Represents analytical performance, including parameters like sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, and precision.

- Blue: Represents practical and economic aspects, such as cost, time, simplicity, and operator safety.

In this model, a "white" method demonstrates a perfect balance and synergy between the analytical, ecological, and practical facets [2] [10]. This holistic approach is crucial for fostering truly sustainable and efficient analytical practices in modern scientific research and industry [10].

Experimental Protocols for Green Spectroscopic Analysis

This section provides detailed methodologies for implementing green spectroscopy in practical settings, based on recently published research.

Protocol 1: Green FT-IR Spectroscopic Quantification of Pharmaceuticals

This protocol details a solventless, non-destructive FT-IR method for the simultaneous quantification of amlodipine besylate (AML) and telmisartan (TEL) in pharmaceutical tablets, as described by Eissa et al. (2025) [7].

1. Principle: The method leverages the Beer-Lambert law, where the absorbance of infrared light at specific wavenumbers is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte. It uses the pressed pellet technique with potassium bromide (KBr), eliminating the need for toxic organic solvents [7].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs): Amlodipine besylate and Telmisartan reference standards.

- Excipients: Common tablet excipients (e.g., microcrystalline cellulose, magnesium stearate, starch) for specificity testing.

- Matrix Material: Potassium Bromide (KBr), infrared grade.

- Solvent: Methanol (for excipient removal test only).

- Equipment: FT-IR Spectrometer, hydraulic pellet press, analytical balance, mortar and pestle.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Green FT-IR Protocol

| Item | Function / Rationale in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | An inert, transparent matrix for preparing solid pellets for FT-IR analysis. Allows direct analysis of solids without solvents. |

| Amlodipine/Telmisartan Standards | Provide known-concentration reference materials for constructing the calibration curve, ensuring method accuracy. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Applies high pressure to uniformly mix the powdered sample with KBr, forming a transparent pellet for IR transmission. |

| FT-IR Spectrometer | The core instrument that irradiates the KBr pellet with IR light and measures the specific wavenumbers absorbed by the drug molecules. |

3. Experimental Procedure:

- Standard Pellet Preparation: Weigh accurately 1-2 mg of the pure AML or TEL standard and mix thoroughly with 100-200 mg of dry KBr powder in an agate mortar. Press the mixture under a hydraulic press at 10-15 tons of pressure for a few minutes to form a transparent pellet.

- Sample Preparation from Tablets: Accurately weigh and powder not less than 20 tablets. Extract the powder with methanol to dissolve the APIs, leaving most excipients undissolved. Filter and evaporate the methanol extract to dryness. Use the resulting residue for pellet preparation as described above.

- Spectral Acquisition: Place the pellet in the FT-IR spectrometer holder. Acquire the transmission spectrum over a defined wavenumber range (e.g., 4000-400 cm⁻¹). Convert the transmittance spectra to absorbance spectra using the instrument's software.

- Calibration Curve: Prepare a series of standard pellets with known concentrations of AML and TEL (e.g., 0.2 to 1.2 %w/w). For AML, measure the area under the curve (AUC) at the characteristic R-O-R stretching vibration at 1206 cm⁻¹. For TEL, measure the AUC at the characteristic C-H out-of-plane bending vibration at 863 cm⁻¹. Plot the AUC against the concentration for each drug to establish the calibration graph.

- Quantification: Prepare a pellet from the sample extract and measure the AUC at 1206 cm⁻¹ and 863 cm⁻¹. Use the respective calibration equations to calculate the concentration of AML and TEL in the sample.

4. Method Validation & Greenness Assessment: The method was validated per ICH guidelines, demonstrating specificity (no interference from excipients), linearity, precision, and accuracy [7]. The greenness was evaluated using multiple metrics:

- MoGAPI score: 89/100

- AGREE prep score: 0.8/1.0

- RGB model: Overall score of 87.2, indicating a high degree of "whiteness" by balancing excellent green credentials with strong analytical performance and practicality [7].

Protocol 2: Resonance Rayleigh Scattering (RRS) for Drug Quantification

This protocol outlines a highly sensitive spectrofluorimetric method based on RRS for quantifying cyclopentolate (CYP) in ophthalmic solutions, as established by recent research (2025) [9].

1. Principle: The method is based on the enhancement of RRS intensity resulting from the formation of an ion-associate complex between the protonated tertiary amine group of CYP and the anionic dye, erythrosine, in a mildly acidic buffer [9].

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Analyte: Cyclopentolate hydrochloride.

- Dye Solution: Erythrosine (0.03% w/v in distilled water).

- Buffer Solution: Torell buffer (or other suitable buffer), pH 3.8.

- Solvent: Distilled water.

- Equipment: Spectrofluorimeter, pH meter, volumetric flasks, vortex mixer.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for RRS Protocol

| Item | Function / Rationale in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Erythrosine Dye | An acidic xanthene dye that forms a charged ion-pair complex with the protonated drug, leading to enhanced RRS signals for detection. |

| Torell Buffer (pH 3.8) | Maintains an optimal acidic pH to ensure the protonation of the drug's amine and the dissociation of the dye, facilitating complex formation. |

| Spectrofluorimeter | Used in synchronous scan mode to measure the intensity of the scattered light (RRS) generated by the drug-dye complex. |

3. Experimental Procedure:

- General Assay: Into a series of 10 mL volumetric flasks, add 1 mL of CYP standard solution (concentration range: 0.4-15 µg/mL).

- Complex Formation: Add 1.3 mL of 0.03% w/v erythrosine solution followed by 1.2 mL of Torell buffer (pH 3.8) to each flask.

- Dilution and Measurement: Dilute the mixture to the mark with distilled water and mix thoroughly. The RRS spectra are recorded using a synchronous spectrofluorimetric mode at a wavelength of 355.5 nm.

- Calibration: Measure the RRS intensity against a concurrently prepared reagent blank. Plot the corrected RRS intensity against the CYP concentration to generate the calibration curve.

- Sample Analysis: Dilute a commercial eye drop solution appropriately so its concentration falls within the linear range of the calibration curve. Follow the general assay procedure and calculate the CYP concentration from the regression equation.

4. Method Performance & Greenness: The method demonstrated a linear range of 40-1500 ng/mL with a detection limit (LOD) of 13 ng/mL [9]. The method is rapid (<5 min analysis time), cost-effective, and aligns with green principles by using aqueous solutions and minimal reagents, presenting an environmentally favorable option for quality control [9].

The integration of the Twelve Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry into spectroscopic practice represents a fundamental shift towards more sustainable and responsible science. As demonstrated by the cited protocols, techniques like FT-IR and RRS spectroscopy offer inherent advantages for developing methods that minimize solvent consumption, reduce waste generation, and enhance operator safety without compromising analytical performance [7] [9]. The ongoing development of sophisticated assessment tools like GEMAM and the holistic framework of White Analytical Chemistry provide critical guidance for researchers to systematically evaluate and improve their methods, ensuring a balance between greenness, functionality, and practical application [10] [8].

The future of green spectroscopy will likely be driven by increased automation, further miniaturization of devices, the development of more sophisticated on-site and portable instruments, and the deeper integration of chemometrics for data analysis [2]. Making analytical laboratories more ecologically conscious is an ongoing process that requires continuous effort and innovation. The adoption of these principles and frameworks is not merely an ethical choice but a practical one, promising economic benefits, enhanced safety, and the development of robust, future-proof analytical techniques [2] [10].

The interactions between electromagnetic radiation and matter—absorption, emission, and scattering—form the foundational principles of spectroscopic analysis. These processes provide crucial information about molecular structure, composition, and dynamics by probing the energy transitions within atoms and molecules [11]. Within the framework of green analytical chemistry, these fundamental interactions are harnessed through techniques specifically designed to minimize environmental impact by reducing hazardous solvent use, decreasing energy consumption, and preventing waste generation [12] [4].

Green spectroscopy represents a transformative approach that aligns analytical methodologies with the 12 principles of green chemistry, creating synergies between analytical performance and environmental responsibility [4]. This technical guide explores these core energy-matter interactions, their theoretical foundations, measurement methodologies, and applications within sustainable analytical frameworks that prioritize waste prevention, safer solvents, and energy efficiency [12].

Theoretical Foundations of Energy-Matter Interactions

Quantum Mechanical Framework

The interaction of light with matter occurs through discrete energy exchanges governed by quantum mechanics. Atoms and molecules exist in specific quantized energy states, and transitions between these states involve the absorption or emission of photons with energies precisely matching the energy difference between states [11] [13]. Electrons occupy specific orbitals around the atomic nucleus with defined energy levels, where the most energetic electrons reside in the outermost orbitals and participate in chemical interactions [14].

The quantized nature of these energy levels means electrons can only absorb specific amounts of energy to jump to higher energy states, and similarly emit discrete energy packets when returning to lower states [13]. This quantum behavior creates unique spectral "fingerprints" for each element and molecule, forming the theoretical basis for spectroscopic identification and analysis [13].

Absorption Processes

Absorption occurs when incident electromagnetic radiation is absorbed by atoms, ions, or molecules, promoting them from lower to higher energy states. This process creates an excited state and results in a decrease in the intensity of transmitted radiation at specific wavelengths [11] [15]. The energy of the absorbed radiation must exactly match the difference between two molecular energy states for the transition to occur [11].

The probability of absorption is determined by the transition dipole moment, which depends on changes in the electronic, vibrational, or rotational state of the molecule [11]. Absorption spectroscopy measures this attenuation of radiation as it passes through a sample, revealing information about the sample's composition and concentration through characteristic absorption patterns [15].

Emission Processes

Emission occurs when excited molecules release energy in the form of electromagnetic radiation while transitioning from higher to lower energy states [11]. This process manifests as two distinct mechanisms:

- Spontaneous emission: A molecule in an excited state spontaneously decays to a lower energy state, emitting a photon with energy corresponding to the energy difference between states [11].

- Stimulated emission: An incident photon interacts with a molecule in an excited state, triggering the emission of a second photon with identical energy, phase, and direction [11].

The intensity of emitted radiation is proportional to the population of molecules in excited states, following Boltzmann distribution principles [11]. Emission spectra typically appear as bright lines on a dark background, with each line corresponding to specific electronic transitions within the atom or molecule [13].

Scattering Processes

Scattering involves the redirection of electromagnetic radiation by molecules without net energy transfer to the molecules, though inelastic scattering does involve energy shifts [11]. Several scattering phenomena are significant in spectroscopic analysis:

- Rayleigh scattering: An elastic process where radiation interacts with molecules and is re-emitted at the same frequency as the incident radiation [11]. The intensity is proportional to the square of the molecular polarizability and inversely proportional to the fourth power of the wavelength, explaining atmospheric phenomena like the blue color of the sky [11].

- Raman scattering: An inelastic process where the scattered radiation has a different frequency than the incident radiation due to interactions that change the vibrational or rotational energy state of the molecule [11]. Stokes Raman scattering occurs at lower frequencies (energy gain by molecule), while anti-Stokes Raman scattering occurs at higher frequencies (energy loss by molecule) [11].

- Brillouin scattering: An inelastic process involving interaction with acoustic phonons (collective vibrational modes) in materials, resulting in small frequency shifts determined by the velocity of acoustic phonons and the incident radiation wavelength [11].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of Core Energy-Matter Interactions

| Process | Energy Transfer | Spectral Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absorption | Energy absorbed by molecule | Dark lines on bright background | Quantitative analysis, concentration determination, electronic state characterization |

| Emission | Energy released by molecule | Bright lines on dark background | Element identification, stellar composition analysis, fluorescence imaging |

| Rayleigh Scattering | No net energy transfer | Same frequency as incident radiation | Atmospheric studies, nanoparticle characterization |

| Raman Scattering | Energy transfer to/from molecule | Frequency-shifted from incident radiation | Molecular fingerprinting, vibrational state analysis, material identification |

Green Analytical Chemistry Framework

Principles of Green Spectroscopy

Green spectroscopy incorporates the 12 principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies, creating a sustainable framework that reduces environmental impact while maintaining analytical precision [4]. These principles provide a comprehensive foundation for designing environmentally benign analytical techniques, with several having particular relevance to spectroscopic methods:

- Waste prevention: Designing analytical processes to avoid generating waste rather than managing it after formation [4]

- Safer solvents and auxiliaries: Replacing toxic solvents with benign alternatives like water, supercritical CO₂, or ionic liquids [12] [4]

- Energy efficiency: Developing techniques that operate under milder conditions and employ alternative energy sources [4]

- Real-time analysis for pollution prevention: Implementing methodologies that monitor processes in real-time to prevent hazardous by-products [4]

The integration of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) provides a comprehensive evaluation of the environmental impact of analytical methods across all stages, from raw material sourcing to waste disposal, enabling informed decisions about method selection and optimization [4].

Green Spectroscopy Techniques

Several spectroscopic techniques align particularly well with green chemistry principles:

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy operates in the 780-2500 nm range and measures interactions between NIR radiation and chemical bonds containing hydrogen (e.g., -OH, -CH, -NH) [16]. This technique offers significant green advantages including minimal sample preparation, non-destructive analysis, rapid measurement capabilities, and elimination of hazardous solvents [16]. Applications include liquid food quality assessment, pharmaceutical analysis, and agricultural product monitoring [16].

Mid-Infrared (MIR) Spectroscopy, including Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, provides molecular fingerprinting capabilities with similar green advantages to NIR spectroscopy [17]. Recent advances combine MIR with interpretable machine learning for geographical origin authentication of agricultural products like flat green tea and quality component prediction [17].

Photoluminescence Spectroscopy (including fluorescence and phosphorescence) measures light emission from matter after photon absorption [18]. Advanced implementations use miniaturized instrumentation and solvent-free methodologies to reduce environmental impact while enabling highly sensitive detection for biomedical imaging and chemical analysis [18].

Table 2: Green Attributes of Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Green Solvent Usage | Energy Requirements | Waste Generation | Sample Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | Minimal to none | Low | None (non-destructive) | High |

| MIR Spectroscopy | Minimal to none | Low | None (non-destructive) | High |

| Photo-luminescence | Reduced (miniaturized formats) | Moderate | Low | Moderate to High |

| Traditional Chromatography | High (organic solvents) | High | Significant | Moderate |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

UV-Vis Absorption Spectroscopy Protocol

Principle: UV-Vis spectroscopy measures the absorption of ultraviolet and visible light by molecules, promoting valence electrons from the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) to the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) [18].

Materials and Equipment:

- Broadband light source (deuterium or tungsten lamp)

- Monochromator or wavelength selector

- Sample cuvette and reference cuvette

- Photodetector

- Data recording system [18]

Procedure:

- Turn on the instrument and allow the light source to stabilize for 15-30 minutes

- Prepare the sample solution using green solvents where possible (water, ethanol, supercritical CO₂)

- Fill the reference cuvette with pure solvent and the sample cuvette with the solution of interest

- Measure the intensity of light passing through the reference (I₀) and the sample (I)

- Calculate absorbance using: A = log₁₀(I₀/I) [18]

- Apply the Beer-Lambert Law for quantitative analysis: A = εcd, where ε is the molar absorptivity, c is concentration, and d is path length [18]

Green Considerations:

- Utilize aqueous or bio-based solvents instead of hazardous organic solvents

- Employ micro-volume cuvettes to reduce sample and solvent consumption

- Implement in-line monitoring for real-time analysis to prevent waste generation

Fluorescence Spectroscopy Protocol

Principle: Fluorescence occurs when a molecule absorbs light at a specific wavelength and rapidly re-emits light at a longer wavelength through spontaneous emission [18].

Materials and Equipment:

- Excitation light source (laser or broadband with monochromator)

- Sample compartment

- Emission monochromator or wavelength selector

- Photodetector positioned at 90° to excitation source

- Data acquisition system [18]

Procedure:

- Prepare sample solution at appropriate concentration (typically μM to nM range)

- Select excitation wavelength based on the absorption maximum of the fluorophore

- Position detector at 90° to the excitation path to minimize background scattering

- Scan emission monochromator while exciting at fixed wavelength to obtain emission spectrum

- Measure fluorescence intensity as a function of emission wavelength

- Calculate fluorescence quantum yield using reference standards: Φ = (number of photons emitted)/(number of photons absorbed) [18]

Green Considerations:

- Utilize solid-state light sources (LEDs) for reduced energy consumption

- Employ microfluidic cells to minimize sample volumes

- Implement chemometric analysis to enhance signal-to-noise ratio instead of concentration-based amplification

Near-Infrared Spectroscopy Protocol with Chemometrics

Principle: NIR spectroscopy probes overtone and combination vibrations of C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds, generating complex spectral data requiring multivariate analysis [16].

Materials and Equipment:

- NIR light source (tungsten-halogen lamp)

- Sample presentation accessory (transmission, reflectance, or transflectance)

- Spectrometer with interferometer or diffraction grating

- Detector (InGaAs, PbS, or DTGS)

- Computing system with chemometric software [16]

Procedure:

- Acquire NIR spectra of samples across the 780-2500 nm range

- Collect reference data for target analytes using primary methods (e.g., HPLC for concentration)

- Preprocess spectral data using techniques like:

- Savitzky-Golay smoothing for noise reduction

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV) transformation for scatter correction

- Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) for path length effects [16]

- Develop calibration model using Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) or machine learning algorithms

- Validate model using independent test set not included in calibration

- Apply model to predict properties of unknown samples

Green Considerations:

- Eliminates solvent consumption through direct analysis of solids and liquids

- Enables real-time, in-process monitoring to prevent off-spec production

- Reduces energy consumption through rapid analysis without extensive sample preparation

Diagram 1: NIRS with Chemometrics Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Green Spectroscopy

| Material/Reagent | Function | Green Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| Traditional Organic Solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, chloroform) | Sample preparation, extraction, mobile phases | Water, ethanol, supercritical CO₂, ionic liquids - Reduce toxicity and environmental persistence [4] |

| Reference Standards | Instrument calibration, quantitative analysis | In-house purified compounds - Minimize packaging and shipping impacts; digital calibration using chemometrics [16] |

| Sample Cells/Cuvettes | Contain samples during measurement | Reusable quartz/silica cells - Reduce waste; microfluidic chips - Minimize sample volume [18] |

| Derivatization Agents | Enhance detection sensitivity | Avoidance through advanced instrumentation - Eliminate toxic reagents; catalytic systems - Reduce stoichiometric waste [4] |

| Extraction Materials (solid-phase, liquid-liquid) | Isolate analytes from complex matrices | Solid-phase microextraction (SPME) - Minimize solvent use; microwave-assisted extraction - Reduce energy consumption [4] |

Advanced Applications in Green Spectroscopy

Sustainable Nanoparticle Synthesis and Analysis

Green spectroscopy enables the sustainable synthesis and characterization of nanomaterials. Plant-derived biomolecules serve as reducing and stabilizing agents in the synthesis of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs), replacing toxic reagents traditionally used [12]. Spectroscopic techniques including UV-Vis, fluorescence, and dynamic light scattering provide non-destructive monitoring of nanoparticle synthesis, growth, and surface functionalization while minimizing environmental impact through real-time analysis that prevents overconsumption of reagents [12].

Food Quality and Authentication Analysis

NIR and MIR spectroscopy combined with chemometrics offer rapid, non-destructive authentication of food products, addressing economic adulteration and geographical origin misrepresentation [16] [17]. For example, MIR spectroscopy with machine learning successfully discriminates GI-certified Longjing tea from non-certified alternatives based on spectral fingerprints, achieving high classification accuracy without hazardous solvents or extensive sample preparation [17]. This approach demonstrates the powerful synergy between green spectroscopy and advanced data analysis for solving real-world authentication challenges.

Environmental Monitoring and Pollution Prevention

Spectroscopic techniques play a crucial role in environmental monitoring through real-time, in-process analysis that prevents pollution at its source [4]. Portable NIR and MIR instruments enable field-based analysis of environmental contaminants without the need for sample transportation and extensive laboratory processing [16]. Green spectroscopic methods provide the sensitivity and selectivity needed for regulatory compliance monitoring while aligning with sustainability goals through reduced energy and solvent consumption [4].

Diagram 2: Green Spectroscopy Conceptual Framework

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with spectroscopic techniques represents a significant advancement in green analytical chemistry [17]. Interpretable machine learning models enhance the transparency of spectral data analysis while optimizing experimental parameters to minimize resource consumption [17]. AI-driven approaches enable researchers to rapidly identify optimal reaction conditions, catalyst systems, and analytical methods that align with green chemistry principles [12].

Miniaturization and portability continue to transform spectroscopic instrumentation, reducing the environmental footprint of analytical methods while expanding application possibilities [4]. Portable NIR and Raman spectrometers enable field-based analysis that eliminates sample transportation and reduces energy consumption compared to traditional laboratory instruments [16]. These technological advances support the transition toward decentralized analytical capabilities that align with the principles of green chemistry.

The ongoing development of green solvent systems including bio-based solvents, deep eutectic solvents, and supercritical fluids further enhances the sustainability of spectroscopic methods [4]. These alternatives reduce reliance on petroleum-derived solvents with higher toxicity and environmental persistence, creating analytical workflows with improved environmental profiles without compromising analytical performance.

Future research directions will likely focus on increasing the sensitivity and resolution of green spectroscopic methods to expand their application to trace analysis, developing standardized greenness assessment metrics for analytical techniques, and creating closed-loop analytical systems that minimize waste generation through continuous recycling of solvents and materials [4]. As these innovations mature, green spectroscopy will continue to transform how scientists extract chemical information while advancing sustainability goals across research and industrial sectors.

The paradigm of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has evolved from a specialized interest to a fundamental requirement in modern laboratories, driven by the need to minimize the environmental impact of chemical analyses. This evolution has been formalized through the establishment of the 12 Principles of GAC, which provide a comprehensive framework for developing environmentally friendly analytical processes. These principles prioritize the use of safer solvents, waste minimization, and reduced energy consumption [19]. A significant advancement beyond GAC is the concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), introduced in 2021, which provides a more holistic evaluation of analytical methods. The WAC concept is visually and conceptually modeled after the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) color model used in electronics, where white light is generated by combining three primary colors. In this analogous framework, the sustainability ("whiteness") of an analytical method is assessed through three complementary attributes [20]:

- Green: Represents the ecological criteria, including environmental impact, safety, and waste generation.

- Red: Symbolizes the analytical performance criteria, encompassing validation parameters such as accuracy, precision, and sensitivity.

- Blue: Denotes the practical and economic criteria, relating to practicality, cost-effectiveness, and ease of implementation.

A truly "white" method achieves an optimal balance among all three attributes, ensuring it is not only environmentally sound but also analytically robust and practically feasible for its intended application [20] [21]. This whitepaper delves into the core tools designed to quantify these attributes, with a specific focus on the AGREE and MoGAPI metrics for greenness, and the broader RGB model for a comprehensive white assessment, all framed within the context of green spectroscopic and chromatographic research.

Detailed Tool Analysis: AGREE, MoGAPI, and RGB

AGREE: The Analytical GREEnness Metric

The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric is a comprehensive greenness assessment tool that incorporates all 12 principles of GAC into its evaluation. It provides a user-friendly software-based calculator that generates a circular pictogram, divided into 12 segments. Each segment corresponds to one GAC principle and is colored on a gradient scale from red to green, providing an immediate visual summary of the method's environmental performance. The tool calculates an overall score on a scale of 0 to 1, displayed in the center of the pictogram, where a score closer to 1 indicates a greener method [19]. This tool has been widely applied to evaluate the greenness of various analytical techniques, including spectroscopic methods. For instance, a recent Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopic method for quantifying antihypertensive drugs was assessed using AGREE, achieving a high score and confirming its eco-friendly credentials by eliminating the need for solvents and minimizing waste [7].

MoGAPI: The Modified Green Analytical Procedure Index

The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) is a popular tool that uses five pentagrams to provide a visual profile of the environmental impact across different stages of an analytical method. However, a key limitation of the original GAPI is the lack of a single, quantitative score for straightforward method comparison. The Modified GAPI (MoGAPI) tool, introduced in 2024, was developed specifically to address this shortcoming. MoGAPI retains the intuitive pictogram of GAPI but introduces a robust scoring system. It calculates a total score, expressed as a percentage, which allows for the direct classification of methods [19]:

- ≥ 75%: Excellent greenness

- 50 – 74%: Acceptable greenness

- < 50%: Inadequate greenness

This tool synergizes the visual strengths of GAPI with the quantitative clarity of other metrics like the Analytical Eco-Scale. The availability of open-source software for MoGAPI (bit.ly/MoGAPI) significantly simplifies and standardizes its application, making it a powerful tool for researchers to evaluate and optimize their methodologies [19]. Its use in assessing an FT-IR method demonstrated a high score of 89, underscoring the green nature of solventless spectroscopic techniques [7].

The RGB Model and White Analytical Chemistry

The RGB model is an assessment framework that operationalizes the principles of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC). It does not refer to a single tool but rather a conceptual approach that can be implemented through various means, such as specialized Excel sheets or algorithms like the RGB 12-model [22] [20]. The core of this model is the simultaneous and balanced evaluation of the three pillars of sustainability:

- Red (Analytical Performance): Assessed using tools like the newly developed Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI), which evaluates ten key validation parameters (e.g., repeatability, sensitivity, linearity, robustness) and presents the results in a star-shaped pictogram with a final score from 0 to 100 [20].

- Green (Environmental Impact): Assessed using dedicated greenness metrics such as AGREE, GAPI, or MoGAPI.

- Blue (Practicality & Economy): Assessed using the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI), which scores ten practical criteria (e.g., cost, time, operational simplicity, hyphenation potential) and also outputs a pictogram with a score from 25 to 100 [20] [21].

The ultimate goal within the RGB framework is to achieve a high degree of "whiteness," representing a method that is analytically valid, environmentally benign, and practically applicable. This integrated approach prevents the selection of a method that is green but functionally inadequate for the required analytical task [20].

Table 1: Summary of Key Greenness and Sustainability Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Assessment Focus | Output Format | Scoring Range | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE [19] | Greenness (12 GAC Principles) | Circular pictogram with 12 segments | 0 to 1 | Comprehensive, considers all 12 GAC principles with software support. |

| MoGAPI [19] | Greenness (Method Steps) | Five pentagrams pictogram with total score | 0% to 100% | Provides a single quantitative score for easy comparison, building on familiar GAPI. |

| RAPI [20] | Red (Analytical Performance) | Star-shaped pictogram | 0 to 100 | First dedicated tool for holistic "redness" assessment based on validation parameters. |

| BAGI [20] [21] | Blue (Practicality & Economy) | Star-shaped pictogram | 25 to 100 | Automated software for evaluating practical aspects like cost, time, and throughput. |

| RGB 12-Model [22] [21] | Whiteness (Overall Sustainability) | Integrated assessment | Combined Score | Enables a combined red-green-blue assessment for a "whiteness" score. |

Experimental Protocols for Tool Application

The effective application of these assessment tools is a systematic process. The following protocols outline the steps for implementing AGREE, MoGAPI, and the RGB framework.

Protocol for AGREE Assessment

- Gather Method Parameters: Compile detailed data on every aspect of the analytical procedure, including the quantities and types of solvents/reagents, energy consumption of instruments, sample size, and waste generation and management.

- Input Data into AGREE Calculator: Access the open-source AGREE software and input the collected data. The software will evaluate the method's compliance with each of the 12 GAC principles.

- Interpret the Output: The software generates a pictogram. Analyze the colored segments to identify which principles are well-satisfied (green) and which require improvement (yellow or red). The overall score provides a quantitative benchmark for comparison with other methods [19].

Protocol for MoGAPI Assessment

- Define Analytical Steps: Break down the analytical method into its core components: sample collection, preservation, transportation, storage, sample preparation, reagent use, instrumentation, and waste handling.

- Access the Software: Navigate to the open-source MoGAPI tool available at bit.ly/MoGAPI.

- Input Methodological Data: For each step in the software, select the option that best describes the procedure (e.g., for "Sample collection," choose between "in-line," "online," or "offline").

- Generate and Analyze Report: The software automatically calculates a total score and produces the colored MoGAPI pictogram. Use the score to classify the method's greenness and the pictogram to pinpoint specific steps with the highest environmental impact [19].

Protocol for RGB Whiteness Assessment

- Perform Individual Assessments:

- Greenness: Conduct an evaluation using a dedicated green metric like AGREE or MoGAPI.

- Redness (Analytical Performance): Use the RAPI software (mostwiedzy.pl/rapi) to score the method based on ten analytical performance criteria, including precision, sensitivity, and linearity [20].

- Blueness (Practicality): Use the BAGI software (mostwiedzy.pl/bagi) to score the method based on ten practical criteria, such as analysis time, cost, and operational simplicity [20] [21].

- Synthesize the Results: Integrate the scores and pictograms from the three individual assessments. A method with high scores in all three dimensions (R, G, B) is considered to have a high degree of "whiteness."

- Optimize and Iterate: Use the integrated results to identify trade-offs. For example, if a method scores high in greenness but low in practicality (blueness), efforts should be focused on simplifying the procedure or reducing its cost without compromising its environmental or analytical performance [20].

Diagram 1: RGB Whiteness Assessment Workflow

Comparative Analysis and Practical Applications

Comparative Tool Performance

A comparative analysis of the reported case studies reveals the strengths and applications of each tool. The transition from GAPI to MoGAPI is particularly significant for quantitative decision-making. As demonstrated in [19], while four different methods might present a similar visual impression in a standard GAPI diagram, the MoGAPI score clearly reveals they all share an identical quantitative rating (e.g., 70), enabling objective comparison. Furthermore, complementary tools often yield aligned conclusions. A method for determining antivirals in environmental water scored 70 using MoGAPI and a comparable result using AGREE, confirming its intermediate greenness through different metrics [19].

Case Study: HPTLC Methods for Antiviral Analysis

A 2025 study provides a robust example of a comprehensive trichromatic sustainability assessment. The research developed two HPTLC methods (normal-phase and reversed-phase) for the concurrent quantification of three antiviral drugs [21]. The reversed-phase method, utilizing a greener ethanol-water mobile phase, was subjected to a multi-tool evaluation:

- Greenness: Assessed with Analytical Eco-Scale, AGREE, and the novel MoGAPI.

- Blueness: Evaluated using the BAGI metric to confirm its practicality and cost-effectiveness.

- Whiteness: The RGB 12-model algorithm was employed to appraise the overall sustainability, proving the method's superiority against a more complex, less sustainable HPLC-HRMS reference method [21]. This case underscores the utility of HPTLC and spectroscopic techniques as inherently greener alternatives due to their generally lower solvent consumption and waste output compared to traditional HPLC.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Green Spectroscopy

| Item / Technique | Function in Green Analysis | Green Advantage / Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Used in FT-IR spectroscopy for preparing solvent-free pellet samples [7]. | Eliminates need for hazardous organic solvents, drastically reducing waste and toxicity. |

| Ethanol | Used as a green solvent in mobile phases for HPLC/HPTLC [23] [21] or for sample preparation. | Biodegradable, less toxic, and renewable compared to acetonitrile or methanol. |

| Water | Used as a base solvent in reversed-phase chromatographic mobile phases or for extraction. | Non-toxic, safe, and inexpensive. Optimizing pH with minimal buffer concentration enhances greenness. |

| HPTLC Plates | Stationary phase for high-performance planar chromatography [22] [21]. | Enables high throughput with minimal solvent volume per sample, reducing waste and energy vs. HPLC. |

| FT-IR Spectrometer [7] | Instrument for vibrational spectroscopic analysis. | Enables rapid, non-destructive qualitative and quantitative analysis without solvents or reagents. |

The landscape of analytical chemistry is irrevocably shifting towards sustainability. The AGREE, MoGAPI, and RGB assessment models provide the necessary, robust frameworks to quantify and guide this transition. While AGREE and MoGAPI offer powerful and specialized evaluation of a method's greenness, the comprehensive RGB framework, augmented by dedicated tools like RAPI and BAGI, is indispensable for developing truly sustainable or "white" methods that excel in analytical performance, practicality, and ecological compatibility. For researchers in drug development and spectroscopy, the consistent application of these tools is no longer optional but a core component of modern, responsible method development. It ensures that the pursuit of analytical excellence goes hand-in-hand with environmental stewardship and economic feasibility, ultimately contributing to the broader goals of sustainable science.

The Role of Green Spectroscopy in Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

Green spectroscopy encompasses the adaptation of spectroscopic techniques to align with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), aiming to minimize environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance. In the pharmaceutical industry, this involves developing methods that reduce or eliminate hazardous solvent use, lower energy consumption, and minimize waste generation throughout the drug development pipeline. The drive toward sustainable practices is transforming analytical laboratories, where traditional methods often involve substantial quantities of toxic solvents and generate significant waste. Green spectroscopic techniques offer viable alternatives that maintain data quality and regulatory compliance while supporting the industry's sustainability goals and alignment with global initiatives like the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UNSDGs) [24]. This whitepaper examines the fundamental principles, technical implementations, and practical applications of green spectroscopy in modern pharmaceutical development.

Principles and Green Advantages of Spectroscopic Techniques

Green spectroscopy implementations prioritize waste prevention, safer solvents, and energy efficiency. The fundamental advantage lies in their ability to provide analytical data with minimal environmental burden, often through direct measurement approaches that eliminate extensive sample preparation.

Table 1: Comparison of Conventional vs. Green Spectroscopic Approaches

| Analytical Aspect | Conventional Methods | Green Spectroscopy Alternatives | Key Sustainability Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Extensive processing, liquid-liquid extraction, derivatization | Minimal preparation, direct analysis, solid sampling | Reduces solvent consumption and waste generation |

| Solvent Usage | High volumes of hazardous solvents (acetonitrile, methanol) | Solventless techniques (FT-IR) or green solvents [7] | Eliminates toxic waste, improves operator safety |

| Energy Consumption | Long analysis times, high temperature operations | Rapid analysis, ambient temperature operation | Lower energy footprint |

| Waste Generation | Significant post-analysis waste requiring treatment | Minimal to no waste produced [7] | Reduces environmental impact and disposal costs |

| Chemical Derivatives | Often uses derivatizing agents | Avoids derivatives through inherent molecular properties | Prevents generation of additional waste streams |

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy exemplifies these principles by enabling quantitative analysis without solvents or additional chemicals. The technique utilizes the natural vibrational properties of molecules, requiring only the analyte itself when using pressed pellet techniques with potassium bromide [7]. This eliminates the need for hazardous solvents throughout the analytical process, significantly reducing the environmental impact compared to chromatographic methods that consume substantial mobile phase volumes.

Key Green Spectroscopic Techniques and Methodologies

Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful green alternative for pharmaceutical analysis, particularly for quantitative determination of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in formulations. The technique measures the fundamental vibrational frequencies of chemical bonds, creating highly characteristic spectra that serve as molecular fingerprints.

Experimental Protocol: Green FT-IR Quantitative Analysis [7]

Sample Preparation: Prepare samples using the pressed pellet technique. Triturate approximately 1-2 mg of API with 200 mg of potassium bromide (KBr). Compress the mixture under high pressure (approximately 10 tons) to form a transparent pellet. This process requires no solvents.

Instrumental Parameters: Acquire spectra using an FT-IR spectrometer with the following typical settings:

- Resolution: 4 cm⁻¹

- Number of scans: 16-32

- Wavenumber range: 4000-400 cm⁻¹

Spectra Processing: Convert obtained transmittance spectra to absorbance spectra. Select characteristic absorption bands for each API that are free from interference from other components:

- For Amlodipine: R-O-R stretching vibrations at 1206 cm⁻¹

- For Telmisartan: C-H out-of-plane bending at 863 cm⁻¹

Quantification Method: Use the area under the curve (AUC) of selected absorption bands for quantification based on the Beer-Lambert relationship. Construct calibration curves by plotting AUC against concentration (%w/w) for standards.

Method Validation: Validate according to ICH guidelines, demonstrating specificity, linearity (e.g., 0.2-1.2% w/w range), precision (intra-day and inter-day RSD < 2%), and accuracy (recovery studies).

The greenness of this FT-IR method has been quantitatively assessed using modern metrics, achieving scores of 89 on the MoGAPI, 0.8 on AGREE prep, and 87.2 on the RGB model, confirming its significantly reduced environmental impact compared to HPLC methods [7].

UV-Vis Spectrophotometry with Advanced Signal Processing

Advanced UV-Vis spectrophotometry coupled with mathematical signal processing represents another green approach that avoids chromatographic separations. These methods resolve overlapping spectra without physical separation of components, dramatically reducing solvent consumption.

Experimental Protocol: Signal Processing Spectrophotometry [24]

Sample Preparation: Dissolve powdered tablet formulations in green solvents such as water or ethanol. Perform minimal processing—typically just filtration before analysis.

Spectral Acquisition: Collect zero-order absorption spectra across appropriate wavelength ranges (e.g., 200-400 nm) using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

Signal Processing Algorithms: Apply integrated signal processing approaches to resolve overlapping spectra:

- ISPP-D0: Processes the mixture's zero-order spectrum through successive manipulation methods including extended absorbance difference, absorbance resolution, and spectrum subtraction.

- ISPP-R: Processes the ratio spectrum of the mixture using dual amplitude difference, ratio extraction, and spectrum subtraction.

Quantification: Measure the resolved signals at predetermined wavelengths for each drug component:

- Candesartan at 254.0 nm

- Hydrochlorothiazide at 270.0 nm

- Amlodipine at 240.0 nm

Method Validation: Establish linearity (e.g., 5.0-35.0 μg/mL ranges), precision, and accuracy according to ICH guidelines, with statistical comparison to reference methods.

This approach maintains the simplicity and rapidity of UV-Vis spectrophotometry while overcoming traditional limitations of overlapping spectra through mathematical resolution, eliminating the need for separation-based techniques with high solvent consumption [24].

FT-IR with Chemometrics for Complex Analysis

For more complex analyses such as trace element quantification, FT-IR combined with chemometrics enables green analytical approaches that replace traditional metal analysis techniques requiring extensive sample digestion and hazardous reagents.

Experimental Protocol: Selenium Detection in Kefir Grain [25]

Sample Preparation: Minimal processing—simply present homogenized samples to the attenuated total reflection (ATR) crystal of the FT-IR spectrometer for direct measurement.

Spectral Acquisition: Collect infrared spectra using ATR-FTIR across the mid-infrared region (4000-400 cm⁻¹) with 32 scans at 4 cm⁻¹ resolution.

Chemometric Analysis: Apply dimensionality reduction algorithms to extract relevant spectral features:

- Competitive Adaptive Reweighted Sampling (CARS)

- Interval Random Frog (IRF)

- Iteratively Variable Subset Optimization (IVSO)

- Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA)

Model Development: Build quantitative prediction models using selected characteristic variables with algorithms including:

- Partial Least Squares (PLS)

- Least Squares Support Vector Machine (LSSVM)

- Extremely Randomized Trees (ET)

Validation: Compare predicted values of total selenium (TSe) and organic selenium (OSe) with reference methods (liquid chromatography-atomic fluorescence spectrometry), demonstrating high correlation coefficients (R² > 0.9) and low prediction errors.

This green method eliminates the need for extensive sample digestion using concentrated acids and complex pretreatment procedures associated with conventional selenium analysis techniques like atomic absorption spectroscopy or inductively coupled plasma methods [25].

Experimental Design and Workflow

The implementation of green spectroscopic methods follows systematic workflows that prioritize sustainability at each stage while maintaining analytical rigor. The diagrams below illustrate key experimental designs and relationships.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Green spectroscopic methods utilize reagents and materials specifically selected for their reduced environmental impact and alignment with sustainability principles.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Green Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Spectroscopy | Environmental Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for FT-IR pellet preparation | Enables solventless analysis; minimal waste generation [7] |

| Green Solvents (Water, Ethanol) | Alternative dissolution media for UV-Vis | Replaces hazardous organic solvents; biodegradable [24] |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Internal reflection element for FT-IR | Enables direct solid/liquid analysis without preparation [25] |

| Chemometric Software | Multivariate data analysis | Reduces need for chemical separations and derivatizations [25] |

| Reference Standards | Method calibration and validation | Ensures method accuracy while minimizing repeated analyses [7] |

Implementation in Pharmaceutical Workflows

Integrating green spectroscopy into pharmaceutical development requires strategic methodological changes that deliver both environmental and operational benefits. The primary applications include:

API Quantification in Formulations

FT-IR spectroscopy has been successfully applied to simultaneous quantification of antihypertensive drugs (amlodipine and telmisartan) in combined dosage forms with accuracy comparable to HPLC methods but with significantly reduced environmental impact [7]. The method demonstrated excellent linearity (0.2-1.2% w/w), precision (RSD < 2%), and recovery (98-102%), validating its suitability for quality control applications.

Raw Material and Excipient Analysis

Green spectroscopic methods provide rapid screening of incoming raw materials, replacing traditional wet chemistry methods that generate substantial waste. The non-destructive nature of techniques like FT-IR allows for further analysis of samples if required.

Process Analytical Technology (PAT)

The real-time monitoring capability of spectroscopic methods makes them ideal for PAT applications in manufacturing, enabling continuous quality assurance while minimizing solvent consumption and waste generation compared to offline chromatographic testing.

Green spectroscopy represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical analysis, offering scientifically robust alternatives to traditional methods while significantly reducing environmental impact. Techniques such as FT-IR and advanced UV-Vis spectrophotometry demonstrate that maintaining analytical excellence does not require compromising sustainability goals. As the pharmaceutical industry continues to prioritize environmental responsibility, the adoption of these green spectroscopic methods will play an increasingly vital role in sustainable drug development. Their implementation supports not only regulatory compliance and product quality but also alignment with global sustainability initiatives, creating a more environmentally conscious approach to pharmaceutical analysis.

Implementing Green Spectroscopic Methods in Pharmaceutical Workflows

The principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) are revolutionizing modern laboratories, driving the adoption of techniques that minimize environmental impact while maintaining analytical excellence. Within this framework, Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy coupled with pressed pellet sample preparation emerges as a powerful, sustainable methodology that aligns with the goals of waste reduction and operator safety. This technique eliminates the need for hazardous organic solvents traditionally used in sample preparation, significantly reducing the generation of chemical waste [7]. The pressed pellet method, which utilizes potassium bromide (KBr) as a matrix material, provides an environmentally benign alternative that does not compromise analytical performance, offering a green pathway for molecular characterization across pharmaceutical, material science, and environmental applications [7] [26].

The significance of solventless FT-IR extends beyond waste reduction. By avoiding solvents that can interfere with spectral interpretation, this approach enhances analytical accuracy while simultaneously reducing costs associated with solvent purchase, disposal, and regulatory compliance. The non-destructive nature of FT-IR analysis further contributes to its sustainability profile, as samples can often be recovered and reused after analysis [26]. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, detailed methodologies, and practical applications of pressed pellet FT-IR spectroscopy, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for implementing this green analytical technique.

Theoretical Foundations of FT-IR Spectroscopy

Core Principles of Infrared Spectroscopy

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb specific frequencies of infrared radiation corresponding to their characteristic vibrational modes. When IR radiation interacts with a sample, chemical bonds undergo vibrational transitions—including stretching, bending, and twisting—that occur at quantized energy levels [27] [26]. The fundamental relationship between molecular structure and IR absorption is described by the equation for vibrational frequency:

[ \nu = \frac{1}{2\pi c}\sqrt{\frac{k}{\mu}} ]

Where (\nu) is the vibrational frequency, (c) is the speed of light, (k) is the force constant of the bond, and (\mu) is the reduced mass of the vibrating atoms. This relationship explains why different functional groups exhibit characteristic absorption bands that serve as molecular fingerprints for identification and characterization [27]. The resulting IR spectrum plots absorbance or transmittance against wavenumber (cm⁻¹), providing a unique pattern that reveals molecular structure, functional groups, and in some cases, quantitative information about analyte concentration [27] [26].

Instrumentation and the Fourier Transform Advantage