Greenness Assessment of UPLC vs HPLC: A Sustainable Framework for Modern Analytical Laboratories

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, apply, and validate green chemistry principles when choosing between Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) and High-Performance...

Greenness Assessment of UPLC vs HPLC: A Sustainable Framework for Modern Analytical Laboratories

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to understand, apply, and validate green chemistry principles when choosing between Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC). It explores the foundational concepts of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), details established methodologies like AGREE and GAPI for environmental impact assessment, and offers practical strategies for method optimization and troubleshooting. By synthesizing validation protocols and comparative analysis, this guide empowers laboratories to make data-driven decisions that enhance analytical sustainability without compromising performance, aligning with global initiatives for greener scientific practices.

The Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Its Imperative in Liquid Chromatography

The Foundation of Green Analytical Chemistry

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a transformative discipline within the broader field of green chemistry, focusing specifically on making laboratory practices more environmentally friendly. While traditional analytical chemistry has prioritized precision and selectivity, often at the expense of environmental considerations, GAC integrates sustainability from the earliest stages of method development [1] [2]. This paradigm shift responds to the recognition that analytical activities, despite their smaller scale compared to industrial chemical processes, collectively generate significant environmental impacts through hazardous solvent usage, waste generation, and energy consumption [3] [4].

The conceptual foundation of GAC was formalized through the establishment of 12 guiding principles that provide a structured framework for developing eco-friendly analytical methods [1] [2]. These principles adapt and extend the original 12 principles of green chemistry published by Anastas and Warner, specifically tailoring them to address the unique requirements and challenges of analytical procedures [1]. The core objectives reflected in these principles include eliminating or reducing the use of hazardous chemicals, minimizing energy consumption, implementing proper waste management, and increasing operator safety [1].

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

The table below outlines the 12 principles of GAC, providing a description and primary goal for each principle:

Table 1: The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

| Principle Number | Principle Name | Description | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Direct Analytical Techniques | Use direct measurement techniques to avoid sample treatment [1]. | Minimize sample preparation steps and reagents [2]. |

| 2 | Minimal Sample Size | Reduce sample size and number of samples [1]. | Limit material consumption and waste generation [2]. |

| 3 | In-situ Measurements | Perform measurements at the sample location [1]. | Avoid transport, preserve sample integrity, and enable real-time analysis [2]. |

| 4 | Integration of Processes | Combine analytical processes and operations [1]. | Save energy and reduce reagent use [2]. |

| 5 | Automation & Miniaturization | Select automated and miniaturized methods [1]. | Enhance efficiency, reduce errors, and minimize reagent volumes [5] [2]. |

| 6 | Avoid Derivatization | Eliminate derivatization steps [1]. | Reduce chemical use, waste, and analysis time [2]. |

| 7 | Waste Minimization | Avoid generation of large waste volumes and manage waste properly [1]. | Reduce environmental impact of analytical waste [2]. |

| 8 | Multi-analyte Methods | Adopt methods that determine multiple analytes simultaneously [1]. | Increase throughput and efficiency [2]. |

| 9 | Energy Efficiency | Minimize energy consumption [1]. | Reduce carbon footprint of analytical operations [3] [2]. |

| 10 | Green Reagents & Solvents | Select and use safer solvents and reagents [2]. | Reduce toxicity and hazardousness of chemicals used [3] [2]. |

| 11 | Real-time Analysis | Pursue real-time, in-process analysis [1]. | Prevent pollution and enable immediate decision-making [2]. |

| 12 | Greenness Assessment | Apply metrics to quantify environmental performance [2]. | Enable objective evaluation and comparison of method greenness [6] [2]. |

Analytical Techniques and GAC Implementation

The Greening of Liquid Chromatography

Liquid chromatography, particularly High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC), is ubiquitous in pharmaceutical and environmental analysis. However, these techniques traditionally contribute significantly to the environmental footprint of analytical laboratories due to their high consumption of organic solvents (often exceeding 1 liter per day per instrument) and substantial energy requirements [3] [5]. The transfer of classical liquid chromatographic methods to more sustainable ones is therefore of utmost importance for progressing toward sustainable development goals [3].

Several key strategies have been identified for greening liquid chromatographic methods, with two of the most impactful being solvent substitution and miniaturization [3] [5]:

- Solvent Substitution: Replacing traditional, hazardous solvents like acetonitrile and methanol with greener alternatives is a primary focus. Ethanol, for instance, is gaining prominence as a more sustainable and less hazardous alternative for reversed-phase chromatography [7]. Other bio-based solvents, such as dihydrolevoglucosenone (Cyrene), derived from renewable feedstocks, also show promising potential [3].

- Miniaturization: Using columns with smaller internal diameters (e.g., 2.0 mm or 1.0 mm instead of the standard 4.6 mm) dramatically reduces mobile phase consumption. A 2.0-mm i.d. column uses approximately one-fifth of the solvent consumed by a 4.6-mm i.d. column at the same linear velocity, while a 1.0-mm microbore column uses only 1/20th [5]. This strategy is naturally aligned with mass spectrometry detection, which favors lower flow rates.

UPLC vs. HPLC: A Green Comparison

UPLC systems operate at significantly higher pressures than HPLC, enabling the use of columns packed with smaller particles (sub-2 µm). This technology offers inherent green advantages by design, primarily through faster analysis times and reduced solvent consumption [8] [7].

Table 2: Greenness Comparison of UPLC vs. HPLC

| Parameter | HPLC | UPLC | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Particle Size | 3-5 µm | <2 µm | Higher efficiency allowing shorter columns [3] |

| Operating Pressure | <400 bar | >600 bar | Enables use of smaller particles for faster separations [7] |

| Analysis Time | Longer (e.g., 10-30 min) | Shorter (e.g., 1-10 min) [8] | Reduced instrument energy consumption per sample [3] |

| Solvent Consumption | Higher volume per analysis | Lower volume per analysis [7] | Less waste generation, lower carbon footprint [3] |

| Column Dimensions | Longer columns (e.g., 150-250 mm) | Shorter columns (e.g., 50-100 mm) | Reduced solvent and energy use [3] [7] |

| Inherent Greenness | Lower | Higher | UPLC is fundamentally greener due to miniaturization and speed [8] [7] |

Experimental data from a study comparing methods for antihypertensive drugs clearly demonstrates these advantages. The reported UPLC/MS/MS method achieved separation within 1 minute, a substantial improvement over conventional HPLC methods, directly resulting in lower solvent consumption and energy use per analysis [8]. Another study developed a UPLC method for pharmaceutical drugs using ethanol as a green solvent and a short column (5 cm), achieving a run time of just 9 minutes, which was assessed as significantly greener than previous methods [7].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

To objectively evaluate and compare the environmental footprint of analytical methods, several greenness assessment tools have been developed. These metrics provide a standardized way to validate claims about a method's sustainability.

Table 3: Key Greenness Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Type | Output | Key Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Method Index) | Qualitative | Pictogram (4 quadrants) | Simple, early tool; limited scope | [8] [6] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Semi-quantitative | Score (100 = ideal) | Penalty points for hazardous chemicals, energy, waste | [8] [2] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Semi-quantitative | Color-coded pictogram | Evaluates entire workflow from sampling to result | [6] [7] [2] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | Quantitative | Score (0-1) & radial pictogram | Incorporates all 12 GAC principles; user-friendly software | [8] [6] [2] |

| BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) | Quantitative | Score (25-100) & pictogram | Assesses practicality/economic aspects, complementing green metrics | [4] [2] |

Application in Method Comparison

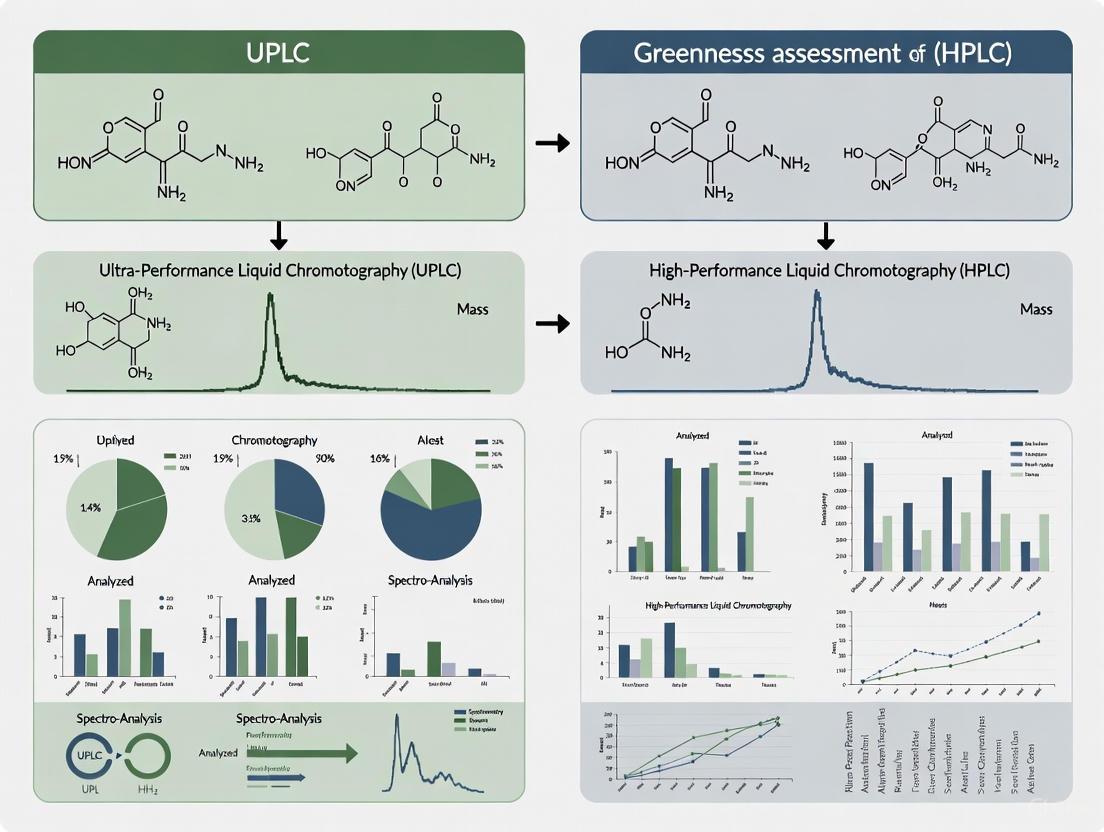

A protocol for comparative assessment involves applying one or more of these tools to both a newly developed method and a reference method. For example, in the cited study of the UPLC/MS/MS method for antihypertensive agents, the authors used five different green metric tools (NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, GAPI, AGREE, and a modified NEMI) to conclusively demonstrate its superior greenness profile compared to a reported HPLC method [8]. This multi-tool approach provides a comprehensive and robust evaluation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chromatography

| Item | Function in Green Chemistry | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Bio-based, less toxic alternative to acetonitrile and methanol [7]. | Mobile phase component in reversed-phase UPLC/HPLC [7]. |

| Dihydrolevoglucosenone (Cyrene) | Bio-based, biodegradable solvent derived from cellulose [3]. | Potential sustainable solvent for liquid chromatography [3]. |

| Water | The ultimate green solvent; used to maximize aqueous mobile phase比例 [3]. | Primary component of mobile phase in reversed-phase LC. |

| Core-Shell (Fused-Core) Columns | Provide high efficiency without the high backpressure of sub-2µm fully porous particles, allowing fast separations on standard HPLC systems [3]. | Enabling faster, more solvent-efficient separations. |

| Monolithic Columns | Silica-based rods with a porous structure that allows high flow rates with low backpressure, reducing analysis time [3]. | Fast separations with low solvent consumption. |

| Short UPLC Columns (e.g., 50 mm) packed with sub-2µm particles | Enable very fast separations with minimal solvent volume and minimal waste generation [3] [7]. | Key for UPLC method development for speed and greenness. |

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing a green analytical method based on the White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) framework, which balances environmental, performance, and practical criteria.

Diagram 1: Green Method Development Workflow. This flowchart outlines the systematic approach to developing an analytical method that balances the three pillars of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC): analytical performance (Red), practicality (Blue), and environmental impact (Green) [4] [2] [9]. The process begins with defining the analytical problem, followed by the application of GAC principles during method development. The resulting method then undergoes rigorous validation of its analytical performance (the "red" component), assessment of its practical and economic feasibility (the "blue" component), and finally, a comprehensive greenness assessment (the "green" component) using specialized metrics. A method that successfully balances these three aspects achieves the ideal of a "white" method [4].

The Environmental and Economic Drive for Sustainable Chromatography

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a significant paradigm shift, driven by the need to align laboratory practices with global sustainability goals. Traditional chromatographic methods, while foundational to drug development and quality control, often rely on hazardous solvents, generate substantial waste, and consume considerable energy. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has emerged as a critical discipline focused on minimizing the environmental footprint of these analytical processes without compromising their scientific robustness [10] [11]. Within this framework, the comparison between Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is particularly relevant. This guide provides an objective comparison of UPLC and HPLC, examining their performance, environmental impact, and economic value within the context of sustainable laboratory practices mandated by modern drug development.

The transition from a linear "take-make-dispose" model to a more circular analytical chemistry framework presents both a challenge and an opportunity for separation scientists [12]. This evolution is supported by the development of standardized greenness assessment tools, which enable the quantitative evaluation of analytical methods, providing researchers and regulatory bodies with clear metrics to guide the adoption of more sustainable practices [10] [2].

Fundamental Principles and Comparison of UPLC and HPLC

Core Technological Differences

Both UPLC and HPLC operate on the principles of liquid chromatography, where separation occurs as analytes distribute between a stationary phase and a mobile phase. The primary technological difference lies in the particle size of the stationary phase. HPLC traditionally uses particles in the range of 3-5 µm, while UPLC employs particles smaller than 2 µm [13]. This reduction in particle size is not merely incremental; it fundamentally enhances chromatographic performance by altering the relationship between flow rate and column efficiency, as described by the Van Deemter equation [13].

The smaller particles in UPLC systems allow for higher efficiency separations but also generate significantly higher backpressures. Whereas HPLC systems typically operate at pressures up to 6000 psi, UPLC instruments are engineered to withstand pressures as high as 15,000 psi (approximately 1000 bar) [13]. This requires robust instrumentation, including specially designed pumps, injection valves, and low-dispersion detectors capable of accurately capturing very narrow peaks.

Direct Performance and Operational Comparison

The following table summarizes a direct comparison of operational parameters between HPLC and UPLC systems for the analysis of the same compounds, based on an optimized method transition:

Table 1: Quantitative Operational Comparison Between HPLC and UPLC

| Characteristic | HPLC | UPLC |

|---|---|---|

| Column Stationary Phase | Xterra, C18, 50 x 4.6 mm, 4 µm particles | AQUITY UPLC BEH C18, 50 x 2.1 mm, 1.7 µm particles |

| Flow Rate | 3.0 ml/min | 0.6 ml/min |

| Injection Volume | 20 µl | 3-5 µl |

| Total Run Time | 10 min | 1.5 min |

| Total Solvent Consumption | Acetonitrile: 10.5 ml, Water: 21.0 ml | Acetonitrile: 0.53 ml, Water: 0.66 ml |

| Column Efficiency (Plate Count) | 2000 | 7500 |

| Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) | ~ 0.2 µg/ml | ~ 0.054 µg/ml |

This data, adapted from a method optimization study, demonstrates that UPLC provides a 3-4 fold reduction in analysis time and a dramatic 90-95% reduction in solvent consumption compared to HPLC [13]. Furthermore, UPLC offers superior analytical performance, evidenced by the significantly higher plate count (a measure of column efficiency) and lower LOQ (increased sensitivity) [13].

Greenness Assessment: A Multi-Metric Evaluation

The environmental profile of analytical methods can be comprehensively evaluated using several established greenness assessment tools. These metrics move beyond simple performance comparisons to provide a holistic view of environmental impact.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Greenness Assessment in Analytical Chemistry

| Tool Name | Main Focus | Output Type | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | All 12 principles of GAC | Radial chart with a score from 0 to 1 | Provides a holistic, single-score metric based on the full GAC principles [2]. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Entire analytical workflow | Color-coded pictogram | Offers easy visualization of impacts across all method steps [10] [2]. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Solvent toxicity, energy, waste, hazards | Penalty-point-based numerical score | A semi-quantitative tool where a higher score indicates a greener method [10] [8]. |

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) | Basic environmental criteria | Binary pictogram (green/white) | A simple, qualitative tool; less comprehensive than modern metrics [7] [8]. |

Application in Pharmaceutical Analysis Case Studies

Case Study 1: Determination of Antiviral and Anti-infective Drugs A 2023 study developed novel Reverse-Phase UPLC and multivariate calibration methods for the concurrent determination of Ciprofloxacin (CIP), Azithromycin (AZI), and Diclofenac (DIC). The method was designed with sustainability as a core principle, utilizing a shorter column (5 cm), ethanol as a green solvent alternative, and a reduced run time of 9 minutes. When evaluated with five greenness assessment tools (AGREE, AGREEprep, GAPI, ComplexGAPI, and Eco-Scale), the proposed UPLC method demonstrated significantly higher greenness scores compared to previously published HPLC methods. The Analytical Eco-Scale scores were 89 for the UPLC method and 84 for the MCR method, confirming their superior environmental profile [7].

Case Study 2: Analysis of Antihypertensive Drugs and Their Impurities A 2023 study in Scientific Reports developed a UPLC/MS/MS method for quantifying captopril, hydrochlorothiazide, and their harmful impurities within 1 minute. The greenness profile of this UPLC method was compared to a reported HPLC method using five metric tools (NEMI, Modified NEMI, GAPI, Analytical Eco-Scale, and AGREE). The study concluded that the proposed UPLC method had a "lower environmental impact" than the reported HPLC method, attributing this to its greater sensitivity, shorter analysis time, and reduced solvent consumption [8].

The workflow for selecting and validating a green chromatographic method based on these assessments can be summarized as follows:

Diagram 1: Method Selection and Green Assessment Workflow

Environmental and Economic Impact Analysis

Direct Environmental Benefits of UPLC

The environmental advantages of UPLC are direct and substantial, primarily stemming from reduced solvent consumption. As shown in Table 1, UPLC can reduce solvent use by over 90% compared to conventional HPLC [13]. This has a cascading positive effect: it minimizes the procurement of hazardous solvents, reduces the energy required for solvent production and transportation, and drastically cuts the volume of waste requiring disposal or treatment [11]. This aligns with the GAC principles of waste minimization and safer solvents [2].

Furthermore, the shorter run times of UPLC methods contribute to lower energy consumption per analysis. Although UPLC instruments may consume similar power to HPLC systems during operation, the ability to complete more analyses in a shorter time frame—or the same number of analyses in a fraction of the time—leads to an overall reduction in the laboratory's energy footprint [10].

Comprehensive Economic and Operational Advantages

The economic argument for UPLC is compelling and extends beyond the obvious cost savings from purchasing fewer solvents. The significant reduction in solvent usage also lowers costs associated with waste disposal, which can be substantial for organic solvents classified as hazardous waste [11] [12]. The increased throughput—enabled by faster run times—allows a laboratory to analyze more samples per day, enhancing productivity and potentially delaying capital expenditure on additional instruments [13].

UPLC also provides superior analytical performance, which carries its own economic value. The higher sensitivity and resolution can reduce the need for sample pre-concentration or re-analysis due to inadequate separation, saving both time and materials [7] [8]. This combination of direct cost savings, productivity gains, and enhanced performance makes UPLC a strong candidate for laboratories aiming to implement more sustainable and economically viable operations.

The Scientist's Toolkit for Sustainable Chromatography

Transitioning to more sustainable chromatographic practices requires specific reagents, columns, and instruments designed for green analytical chemistry.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Chromatography

| Item | Function | Green Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Green solvent alternative for mobile phases [7]. | Less hazardous and toxic than acetonitrile or methanol; biodegradable and from renewable sources [7] [11]. |

| Superficially Porous Particles (e.g., Fused-Core) | Stationary phase for HPLC and UPLC columns [14]. | Provide high efficiency similar to sub-2µm UPLC particles but with lower backpressure, enabling faster separations on some HPLC systems with less solvent [14]. |

| Bioinert or Inert Hardware Columns | Analytical columns with passivated metal surfaces [14]. | Prevent adsorption of metal-sensitive analytes (e.g., phosphorylated compounds), improving analyte recovery and reducing the need for method redevelopment or repeat analyses [14]. |

| UPLC Systems (e.g., ACQUITY UPLC) | Instrumentation designed for high-pressure separations [13]. | Enables use of sub-2µm particles for faster analyses and drastically reduced solvent consumption, directly addressing GAC principles [13]. |

| Hybrid Particle Columns (e.g., BEH Technology) | Second-generation stationary phase chemistry [13]. | Offers high mechanical stability for UPLC pressures and extended pH stability, improving method robustness and column lifetime, reducing waste [13]. |

Challenges and Future Perspectives in Sustainable Chromatography

Despite the clear benefits, the adoption of greener chromatographic methods like UPLC faces several barriers. The initial capital cost of UPLC instrumentation can be higher than that for HPLC, potentially deterring budget-conscious laboratories [11] [12]. There is also a need for broader education and training on GAC principles and the use of greenness assessment tools. Furthermore, the conservative nature of analytical chemistry and regulatory inertia can slow the phase-out of outdated, resource-intensive standard methods in favor of greener alternatives [12].

The future of sustainable chromatography will likely involve greater interdisciplinary collaboration among scientists, instrument manufacturers, and regulatory bodies [11] [12]. The concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) is gaining traction, which seeks a balance between analytical performance (red), environmental impact (green), and practical applicability (blue) [10] [2]. Tools like the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) are emerging to complement greenness assessments by evaluating practical viability [2]. Finally, a shift from "weak sustainability," which focuses on incremental improvements, toward "strong sustainability," which aims for regenerative and ecologically restorative practices, represents the next frontier for the field [12].

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate liquid chromatography technique is a critical decision that balances analytical performance with practical and environmental considerations. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) has served as the analytical cornerstone for decades, but the introduction of Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) in 2004 by Waters Corporation marked a significant technological evolution [15] [16]. This guide provides an objective comparison of UPLC and HPLC, focusing on the core technical differentiators—operating pressure, particle size, and system design—and their practical impact on parameters such as resolution, throughput, and sensitivity. Furthermore, it frames this comparison within the growing imperative for Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC), assessing the environmental footprint of each technique to aid in sustainable method development.

Core Technical Differentiators

The enhanced performance of UPLC systems stems from fundamental improvements in three key areas, which work in concert to deliver superior chromatographic results.

Operating Pressure

- HPLC: Traditional HPLC systems are designed to operate at pressures typically up to 6,000 psi (approximately 400 bar) [17]. This pressure ceiling limits the flow rates that can be used with densely packed columns.

- UPLC: UPLC systems are engineered to withstand significantly higher pressures, routinely operating at up to 15,000 psi (approximately 1,000 bar) and beyond [17] [16]. This high-pressure capability is a prerequisite for efficiently driving mobile phases through columns packed with smaller particles, which offer greater resistance to flow.

Column Particle Size

- HPLC: HPLC columns are typically packed with 3-5 µm particles [17] [16]. While these particles provide robust and reliable separations, the paths for molecular diffusion (eddy diffusion) are larger, leading to broader peaks.

- UPLC: UPLC utilizes columns packed with sub-2 µm particles (often 1.7 µm) [16]. The reduced particle size creates a more uniform packing structure, which directly minimizes the A term (eddy diffusion) in the van Deemter equation [18]. This results in narrower chromatographic peaks and higher efficiency.

Holistic System Design

A key differentiator often overlooked is the holistic design philosophy. While Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) is a general term for modified HPLC systems capable of using sub-2 µm particles, UPLC refers to a proprietary, holistically optimized system [15] [16]. Modified HPLC/UHPLC systems often require significant hardware changes (e.g., microbore flow cells, reduced-volume tubing, injector bypass) to minimize extra-column volume and band broadening when using sub-2 µm columns [15]. Even with these modifications, their performance in terms of peak capacity and sensitivity may not match that of a system like the ACQUITY UPLC, which was designed from the ground up for low-dispersion, high-resolution chromatography [15].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Outcomes

The technical differences between HPLC and UPLC translate directly into measurable performance advantages. A direct comparison of an anesthetic mixture separation on multiple vendors' systems quantified these disparities.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison between HPLC and UPLC

| Performance Parameter | HPLC (Typical 4.6 mm ID Column) | UPLC (2.1 mm ID Column) | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Pressure | Up to 6,000 psi [17] | Up to 15,000 psi [17] | System specifications |

| Typical Particle Size | 3-5 µm [17] [16] | < 2 µm (e.g., 1.7 µm) [16] | Column specifications |

| Theoretical Plate Count | ~100,000 plates/meter [17] | >300,000 plates/meter [17] | Kinetic performance measurement |

| Analysis Time | Baseline (e.g., 10-20 min) | 50-80% reduction [17] | Gradient separation of drug mixtures |

| Peak Capacity | Lower (e.g., 28-33% lower than UPLC) [15] | Higher | Separation of six anesthetics [15] |

| Solvent Consumption | Baseline | Up to 80% reduction with 2.1 mm ID column [15] | Comparison of column geometry and flow rates |

| Sensitivity | Lower due to larger column volume and peak dispersion | Higher due to narrower peaks and reduced band broadening [15] | Fixed y-axis chromatogram comparison |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The data in Table 1 is supported by a controlled comparative study. The following protocol outlines the methodology used to generate the key chromatographic data [15]:

- Objective: To compare the separation efficiency, sensitivity, and analysis time of a UPLC system against modified UHPLC systems from various vendors.

- Materials: The same ACQUITY UPLC sub-2 µm column (2.1 mm I.D.), lot of mobile phase, and wash solvents were used on all tested systems to ensure a fair comparison.

- Instrument Configuration: All UHPLC systems were configured according to the manufacturer's recommendations for low system delay volume. This included installing microbore flow cells, reduced-volume mixers and tubing, and utilizing injector bypass modes where available. The ACQUITY UPLC system was used in its standard, unmodified configuration.

- Method: A separation method for a mixture of six anesthetics was executed on each system. Critical separation parameters assessed included peak capacity (number of peaks resolved in a gradient time), peak width ratio (comparing early and late eluting peaks), and elution time of the last peak.

- Results Interpretation: The study concluded that the holistically designed UPLC system "easily outperformed all of the UHPLC vendors' systems with the greatest peak capacity, highest sensitivity, and fastest analysis time," attributing this to superior design minimizing gradient delay and extra-column band spreading [15].

Greenness Assessment of UPLC vs. HPLC

The principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) provide a framework for evaluating the environmental impact of analytical methods, focusing on waste reduction, safety, and energy efficiency [10] [2]. When viewed through this lens, UPLC offers significant "green" advantages over traditional HPLC.

Application of Green Metrics

Tools like the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric and the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) are used to provide a quantitative and visual assessment of a method's environmental impact [10] [2]. These tools evaluate the entire analytical workflow against the 12 principles of GAC.

Key areas where UPLC enhances greenness include:

- Solvent Reduction: The migration from traditional 4.6 mm I.D. HPLC columns to 2.1 mm I.D. UPLC columns can reduce solvent consumption by nearly 5-fold (80%) for a column of the same length, directly minimizing waste generation (GAC Principle #4) and the use of hazardous chemicals (Principle #5) [15] [2].

- Energy and Time Efficiency: Faster analysis times (up to 10x faster than HPLC) lead to reduced energy consumption for instrument operation (Principle #7) and increased laboratory throughput [17] [16].

- Miniaturization: The use of smaller columns, lower flow rates, and reduced sample volumes aligns with the GAC principle of miniaturization (Principle #8) [2].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between UPLC technical advantages and GAC principles:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementing a robust UPLC method, especially one aligned with green principles, requires specific reagents, tools, and a systematic approach. The following toolkit is essential for researchers.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Features for Performance & Greenness |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-2µm UPLC Columns | High-resolution stationary phase; core differentiator for UPLC. | Small particle size (<2µm) for high efficiency; 2.1 mm I.D. for low solvent consumption [15] [16]. |

| Eco-Friendly Solvents | Mobile phase (e.g., Ethanol, Water). | Replace hazardous solvents (acetonitrile/methanol); ethanol-water mixtures are a favored green alternative in method development [19] [2]. |

| Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) | Systematic framework for method development. | Uses Design of Experiments (DoE) to optimize for robustness and greenness simultaneously, minimizing experimental waste [19]. |

| Greenness Assessment Software | Evaluate method environmental impact. | Tools like AGREE and GAPI software provide scores/pictograms to quantify and guide sustainable method choices [10] [2]. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) Detectors | High-sensitivity detection and compound identification. | Coupling with UPLC (e.g., UPLC-MS/MS) provides superior selectivity for trace analysis in complex matrices [16] [20]. |

UPLC and HPLC are distinct technologies suited for different analytical needs. HPLC remains a robust, versatile, and cost-effective solution for many routine analyses. However, for applications demanding higher resolution, faster throughput, greater sensitivity, and a reduced environmental footprint, UPLC presents a compelling advantage. The core differences in pressure tolerance, particle size, and holistic system design directly translate to superior performance metrics and align with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry. For drug development professionals and researchers, the integration of UPLC with eco-friendly solvents and an AQbD framework represents the cutting edge of sustainable, high-performance analytical science.

In modern laboratories, particularly within the pharmaceutical and environmental sectors, the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have become a central tenet for sustainable operation. GAC focuses on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods by reducing hazardous chemical use, energy consumption, and waste generation [10] [2]. As analytical workhorses, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) are frequently scrutinized under this lens. This guide provides an objective comparison of the environmental footprints of HPLC and UPLC systems, quantifying their resource consumption to support evidence-based, sustainable decision-making for researchers and drug development professionals. The core environmental differentiators between these techniques stem from fundamental engineering differences: UPLC employs smaller particle sizes (<2 μm) and operates at significantly higher pressures (up to 15,000 psi or 1,000-1,200 bar), which directly enables reductions in solvent use, waste production, and analysis time [21] [22] [17].

Core Technology Comparison and Environmental Impact Mechanisms

The environmental performance of HPLC and UPLC is a direct consequence of their technical design. The following table summarizes the key technical differences that drive their respective resource consumption.

Table 1: Fundamental Technical Specifications of HPLC vs. UPLC

| Parameter | HPLC | UPLC |

|---|---|---|

| Column Particle Size | 3–5 μm | <2 μm (typically ~1.7 μm) [21] [22] [23] |

| Operating Pressure | Up to 6,000 psi (~400 bar) [21] [22] | Up to 15,000 psi (~1,000-1,200 bar) [21] [22] [17] |

| Typical Column Dimensions | 150–250 mm x 4.6 mm ID [22] | 30–100 mm x 2.1 mm ID [22] |

| Typical Flow Rate | 0.5–2.0 mL/min [22] | 0.2–0.5 mL/min [22] |

UPLC achieves its performance and efficiency gains by using smaller particles. The reduced particle size increases the surface area for interaction, creating greater separation efficiency. This allows for the use of shorter columns to achieve the same resolution, which in turn requires lower flow rates and less solvent to pass through the system in a given time [22]. The relationship between these technical parameters and the ultimate environmental impact is illustrated below.

Quantitative Environmental Footprint Comparison

Experimental data from direct comparison studies provides clear evidence of UPLC's advantages in reducing resource consumption. The following table synthesizes quantitative findings from various studies, including analyses of pharmaceutical drugs and benzodiazepines.

Table 2: Experimental Data Comparing Environmental Resource Consumption

| Environmental Parameter | HPLC Performance | UPLC Performance | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | 20–45 minutes [22] | 2–5 minutes [22] | Pharmaceutical analysis [22] |

| 40 minutes [24] | 15 minutes [24] | Benzodiazepine detection in biological samples [24] | |

| Solvent Consumption | High [21] [22] | 70-80% reduction [22] | General method scaling [22] |

| ~16 mL per run [24] | ~4.5 mL per run [24] | Benzodiazepine analysis, 40 min vs. 15 min run [24] | |

| Waste Generation | Correlates with solvent use | Proportionally reduced | Implied from solvent consumption data [22] [24] |

| Injection Volume | 10–20 μL [23] | 1–2 μL [23] | General practice [23] |

A notable case study analyzing a ternary mixture of pharmaceutical drugs (Ciprofloxacin, Azithromycin, and Diclofenac) developed a UPLC method that underscored its green credentials. The method reduced the run time to just 9 minutes and replaced traditional solvents with greener ethanol, resulting in a significantly improved greenness profile when assessed with multiple metrics (AGREE, GAPI, Eco-Scale) [7].

Methodologies for Greenness Assessment

To move beyond qualitative claims, the analytical community has developed standardized tools for quantifying the environmental impact of methods. These tools provide a structured way to evaluate and compare the "greenness" of HPLC and UPLC methods.

Table 3: Key Greenness Assessment Tools for Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Type of Output | What It Evaluates | Application in Chromatography |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Eco-Scale [10] [2] | Numerical score (100 = ideal) | Penalty points for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, waste [10] | Provides a semi-quantitative score for quick comparison between methods. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [10] [2] | Color-coded pictogram | Entire analytical workflow from sampling to detection [10] | Visually identifies the specific stages of a method that have the highest environmental impact. |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [10] [7] [2] | Radial diagram & score (0-1) | All 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry [10] [2] | Offers a comprehensive, holistic single-score metric based on the full GAC framework. |

| AGREEprep [10] [2] | Pictogram & score | Sample preparation stage only [10] | Focuses evaluation on the sample prep step, which is often a major source of waste. |

The workflow below illustrates how these metrics are applied in practice to evaluate an analytical procedure, leading to a more sustainable scientific outcome.

The Researcher's Toolkit for Sustainable Chromatography

Transitioning to more environmentally sustainable chromatography involves a combination of instrument selection, consumables, and assessment tools. The following table details key solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Reagents, Tools, and Solutions for Green LC Practice

| Tool / Solution | Function in Green Chromatography | Specific Example / Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-2 μm UPLC Columns | Enables faster separations with higher efficiency, reducing runtime and solvent use. | 100 mm x 2.1 mm column for scaling down from 250 mm x 4.6 mm HPLC columns [22]. |

| Green Solvent Alternatives | Replaces hazardous traditional solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) with safer options. | Use of ethanol as a less hazardous and more sustainable mobile phase component [7]. |

| Method Scaling Calculators | Provides formulas to accurately transfer HPLC methods to UPLC while maintaining resolution. | Scaling flow rate and injection volume based on column geometry to ensure performance [22]. |

| AGREE & GAPI Software | Open-source software that provides quantitative greenness scores for analytical methods. | Allows researchers to numerically benchmark and prove the improved sustainability of their UPLC methods [10] [2]. |

| Low-Volume Flow Cells | Specialized detector components for UPLC systems that minimize post-column band broadening. | Critical for maintaining sensitivity and resolution with the narrow peaks produced by UPLC [25] [26]. |

The experimental data and assessment metrics presented demonstrate that UPLC technology offers a significant and quantifiable advantage over traditional HPLC in reducing the environmental footprint of analytical laboratories. The primary benefits are drastically lower solvent consumption and waste generation, achieved through faster analysis times and more efficient system design. As the field of Green Analytical Chemistry continues to mature, the adoption of tools like AGREE and GAPI will become standard practice for justifying method selection and guiding the development of new, sustainable techniques. Future developments will likely focus on further automation, integration of even more eco-friendly solvents, and instrumentation designed for even greater energy efficiency, solidifying the role of UPLC as a cornerstone of environmentally responsible analytical science [21] [10] [2].

The field of analytical chemistry is undergoing a significant paradigm shift, moving beyond a singular focus on environmental considerations toward a more holistic integration of performance, practicality, and sustainability. While Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has been instrumental in reducing the environmental footprint of analytical methods by minimizing waste and hazardous substance use, it often does not fully address critical parameters such as analytical performance and economic feasibility [27]. This limitation has led to the emergence of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), a comprehensive framework designed to balance the three fundamental pillars of modern analytical science: analytical efficacy (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical/economic considerations (Blue) [27] [28]. This model evaluates methods not just on their greenness but on their overall "whiteness"—a harmonious integration of all three dimensions.

Within pharmaceutical research and drug development, this evolution is particularly relevant for comparing established and emerging chromatographic techniques. The debate between Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is a prime example, traditionally focused on performance metrics. However, when framed within the WAC model, this comparison transforms into a multidimensional assessment crucial for developing sustainable, efficient, and robust analytical methods for modern laboratories. This guide provides an objective, WAC-based comparison of UPLC and HPLC, supported by experimental data and standardized assessment protocols, to inform method selection in pharmaceutical analysis.

The White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) Framework: A Red-Green-Blue (RGB) Model

The WAC framework employs an RGB color model to visualize and quantify the balance of its three core aspects [27]. A method that optimally balances all three components produces a "white" light of quality.

- Red Component (Analytical Performance): This dimension assesses the fundamental analytical validity of a method. Key metrics include sensitivity, selectivity, accuracy, precision, linearity, robustness, and resolution [27]. The "red" score reflects the method's ability to deliver reliable, high-quality data.

- Green Component (Environmental Impact): This dimension, inherited from GAC, evaluates the method's environmental footprint. It considers factors such as energy consumption, the type and volume of solvents used, waste generation, reagent toxicity, and operator safety [27] [2]. The goal is to minimize ecological impact and health hazards.

- Blue Component (Practical & Economic Factors): This dimension addresses the practical implementation of the method in a laboratory setting. It includes criteria such as cost-effectiveness, analysis time, ease of use, sample throughput, need for specialized equipment or training, and potential for automation [27]. A high "blue" score indicates a method that is practical and economical for routine use.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these three components and the goal of achieving a "white," balanced method.

Comparative Analysis: UPLC vs. HPLC through the WAC Lens

The following tables provide a detailed, point-by-point comparison of UPLC and HPLC systems across the three dimensions of the WAC model, summarizing their core characteristics and quantitative performance.

Table 1: Instrumentation and Core Principle Comparison

| Feature | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Operating Principle | Isocratic or gradient separation using moderate pressure. | Isocratic or gradient separation using very high pressure. |

| Typical Particle Size | 3–5 µm | Sub-2 µm (often 1.7 µm) |

| Operating Pressure Range | Up to 400 bar (approx. 6,000 psi) | 600–1000 bar (approx. 15,000 psi) |

| System Dispersion | Higher | Significantly lower |

Table 2: WAC-Based Quantitative Method Comparison (Theoretical)

| Assessment Parameter | HPLC Method | UPLC Method | WAC Dimension |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | ~15-30 minutes | ~5-10 minutes | Blue |

| Solvent Consumption per Run | ~2-5 mL | ~1-2 mL | Green |

| Theoretical Plates | ~10,000 | ~20,000-30,000 | Red |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Baseline | Typically 1.5-3x higher | Red |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Baseline | Typically 2-5x lower | Red |

| Sample Throughput | Lower | Higher | Blue/Green |

| Organic Waste Generated | Higher | Reduced by 50-90% [2] | Green |

| Energy Consumption | Lower pressure, lower energy per run | Higher pressure, higher energy per run, but lower per sample due to speed | Green/Blue |

| Instrument Cost & Maintenance | Lower initial cost, established | Higher initial cost, specialized | Blue |

Experimental Protocols for WAC Assessment

To objectively compare the greenness and whiteness of analytical methods, standardized assessment tools and protocols are essential. The following section outlines a general experimental workflow and the key metrics used for evaluation.

General Workflow for Method Comparison

The diagram below outlines a generalized experimental workflow for developing and comparing chromatographic methods like UPLC and HPLC within a WAC framework.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: A Case Study on Pharmaceutical Analysis

A referenced study demonstrates the practical application of a WAC-assisted Analytical Quality by Design (AQbD) approach for developing a reversed-phase chromatographic method for a combination of drugs in human plasma [28]. The key steps of such a protocol are:

- Goal Definition: The aim was to simultaneously separate and quantify azilsartan, medoxomil, chlorthalidone, and cilnidipine. The method needed to be robust, sensitive for plasma analysis, and environmentally sustainable.

- Method Scoping & Instrument Selection: Both UPLC and HPLC systems were evaluated. The UPLC system utilized a column packed with sub-2µm particles, while the HPLC system used a conventional 5µm column.

- Method Development & Optimization: Critical method parameters were optimized, likely including:

- Mobile Phase Composition: Selection and ratio of aqueous and organic phases (e.g., phosphate buffer or ammonium acetate vs. acetonitrile or methanol), with a preference for less toxic solvents where possible [2].

- Flow Rate: Optimized for both separation efficiency and solvent consumption.

- Gradient Program: Temperature and gradient profile were fine-tuned to achieve baseline separation of all four analytes and plasma matrix components in the shortest possible runtime.

- Detection Wavelength: Selected using a diode array detector (DAD) to ensure maximum sensitivity for all analytes.

- Method Validation: The developed UPLC and HPLC methods were rigorously validated according to ICH Q2(R1) guidelines. Key Red (Analytical) parameters assessed included:

- Linearity & Range: Calibration curves were constructed and evaluated for correlation coefficient (R²).

- Precision: Repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day) were expressed as % Relative Standard Deviation (%RSD).

- Accuracy: Determined via recovery studies using spiked plasma samples.

- Sensitivity: Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) were calculated based on signal-to-noise ratio.

- Greenness and Whiteness Assessment: The final validated methods were evaluated using green metrics (e.g., AGREE) and the comprehensive WAC model [28]. The study reported that the optimized method achieved an "excellent white WAC score," indicating a successful balance of the RGB criteria.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UPLC/HPLC Method Development

| Item | Function in UPLC/HPLC | Greenness & Practicality Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Common organic mobile phase modifier; strong elution strength. | Toxic, high environmental impact; requires careful waste disposal. Preferred for high-performance separations [2]. |

| Methanol | Common organic mobile phase modifier; less expensive than acetonitrile. | Less toxic than acetonitrile but still hazardous. Can be a greener alternative in some applications [2]. |

| Water (HPLC Grade) | Aqueous component of the mobile phase. | Solvent choice itself is green; energy for purification is primary concern. |

| Ammonium Acetate / Formate | Additives for buffering mobile phase to control pH and improve peak shape. | Generally preferable to phosphate buffers for MS-compatibility and biodegradability. |

| Phosphate Buffers | Traditional additives for mobile phase buffering. | Can precipitate and cause system damage; less eco-friendly than volatile alternatives. |

| Reference Standards | Highly pure compounds used for peak identification and calibration. | - |

| Stationary Phases | The column packing material where chemical separation occurs. | UPLC columns (sub-2µm) provide higher efficiency but are more expensive and prone to clogging. HPLC columns (3-5µm) are more robust and forgiving. |

Greenness and Whiteness Assessment Metrics

A variety of tools have been developed to quantitatively assess the environmental and practical aspects of analytical methods.

Table 4: Summary of Key Greenness and Whiteness Assessment Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Focus | Output Type | Key Features & Relevance to WAC |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [2] [29] | Greenness | A radial pictogram and a score from 0-1, based on all 12 GAC principles. | Provides a comprehensive, single-score greenness assessment. Directly feeds into the "Green" component of WAC. |

| AGREEprep [12] [2] | Greenness of Sample Preparation | A pictogram and score, based on 10 sample preparation criteria. | The first dedicated metric for evaluating the sample preparation step, a critical part of the analytical lifecycle. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [2] [29] | Greenness | A color-coded pictogram covering the entire analytical workflow. | Allows for quick visual identification of the environmental impact at each stage of a method. |

| BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) [27] [2] | Practicality & Applicability (Blue) | A numerical score and a visual "asteroid" pictogram. | Evaluates practical aspects like cost, time, and ease of use. Directly feeds into the "Blue" component of WAC. |

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [29] | Greenness | A simple pictogram with four criteria (PBT, Hazardous, Corrosive, Waste). | Easy to use but provides only a qualitative pass/fail assessment. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [27] [29] | Greenness | A total score; points are subtracted for hazardous practices. | A semi-quantitative tool; scores above 75 are considered excellent green methods. |

| GEMAM (Greenness Evaluation Metric for Analytical Methods) [29] | Greenness | A pictogram with seven hexagons and a 0-10 score, based on 21 criteria from GAC and GSP. | A recently proposed (2025), comprehensive metric that is simple, flexible, and covers the entire analytical assay. |

The comparison between UPLC and HPLC, when viewed through the comprehensive lens of White Analytical Chemistry, reveals a nuanced trade-off. UPLC systems consistently demonstrate superior performance in the Red (analytical) domain, offering higher resolution, sensitivity, and speed. They also score highly in the Green (environmental) dimension due to significant reductions in solvent consumption and waste generation per analysis [2]. However, the Blue (practical/economic) dimension, characterized by higher initial instrument costs and more demanding maintenance requirements, can be a limiting factor.

The choice between UPLC and HPLC is no longer a simple question of which technique is "better." Instead, it is a strategic decision that must balance analytical requirements, sustainability goals, and practical laboratory constraints. The WAC model provides the necessary framework for this multidimensional assessment, guiding researchers and drug development professionals toward selecting or developing methods that are not only scientifically valid but also environmentally responsible and economically viable—truly "white" methods for a sustainable future.

A Practical Guide to Greenness Assessment Tools: From NEMI to AGREE

The principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have become a cornerstone of sustainable practices in modern laboratories, driving the development of methodologies that minimize environmental impact while maintaining analytical efficacy [30] [10]. For researchers and drug development professionals, particularly those investigating the environmental footprint of techniques such as UPLC versus HPLC, assessing a method's greenness is no longer optional but a critical component of methodological reporting and selection [31] [10].

The evolution of GAC has spurred the creation of dedicated metric tools to quantify and compare the environmental impact of analytical procedures [32] [33]. This guide provides a comparative overview of five major greenness assessment metrics—NEMI, AES, GAPI, AGREE, and AGREEprep—equipping scientists with the knowledge to evaluate their analytical workflows objectively.

Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the five major metrics, providing a clear framework for selection.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Metrics in Analytical Chemistry

| Metric Name | Year Introduced | Assessment Basis | Output Type | Scale/Scoring | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [31] [33] | 2002 [33] | 4 environmental criteria [32] | Pictogram (4 quadrants) [32] | Binary (Green/Uncolored) [32] | Simple, intuitive pictogram [31] | Qualitative only; limited criteria; lacks granularity [32] [10] |

| AES (Analytical Eco-Scale) [31] [33] | 2012 [33] | Penalty points for non-green aspects [10] | Numerical score [34] | 100-point scale (Ideal = 100) [31] | Semi-quantitative; allows direct method comparison [10] | No pictogram; relies on expert judgment for penalties [10] [34] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [31] [34] | 2018 [33] | Multiple aspects across 5 stages of analysis [34] | Pictogram (5 colored pentagrams) [34] | 3-level color scale (Green/Yellow/Red) [34] | Visual; covers entire analytical procedure [10] | No overall score (original version); some subjective color assignment [10] [34] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness Metric) [32] [35] | 2020 [32] | 12 SIGNIFICANCE principles of GAC [32] | Pictogram (clock-like graph) & numerical score [32] | 0-1 scale (Ideal = 1) [32] | Comprehensive; user-friendly software; flexible weighting [32] [10] | Does not fully cover pre-analytical processes [10] |

| AGREEprep (AGREE for sample preparation) [36] [37] | 2022 [36] | 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) [37] | Pictogram (round graph) & numerical score [37] | 0-1 scale (Ideal = 1) [37] | First dedicated metric for sample preparation; high specificity [36] [37] | Focuses only on sample prep; must be used with a broader tool [10] [37] |

Evolution and Workflow of Greenness Assessment

The development of greenness metrics illustrates a clear trajectory from simple, binary evaluations towards comprehensive, quantitative, and software-supported tools. The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary relationship and primary focus of these major metrics.

Foundational Metrics: NEMI and Analytical Eco-Scale

NEMI was the first tool developed to address the need for environmental assessment in analytical chemistry. Its pictogram is a circle divided into four quarters, each representing a criterion: whether chemicals are on the PBT (Persistent, Bioaccumulative, and Toxic) list; whether solvents are hazardous; whether the pH is between 2 and 12; and whether waste is ≤50 g [32] [31]. A major limitation is its binary nature (a criterion is either met or not), which fails to distinguish between degrees of greenness [32] [10].

The Analytical Eco-Scale (AES) introduced a semi-quantitative approach. It assigns penalty points to non-green aspects of a method (e.g., hazardous reagents, high energy consumption, waste generation), which are subtracted from a base score of 100. The resulting score categorizes the method: >75 represents excellent greenness, 50-75 represents acceptable greenness, and <50 represents inadequate greenness [31] [34]. While useful for comparison, it lacks a visual pictogram and involves subjectivity in assigning penalties [10] [34].

Advanced, Pictogram-Based Metrics: GAPI and AGREE

The Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) expanded assessment scope with a five-part pentagram pictogram that evaluates the entire analytical process from sampling to detection [10] [34]. Each section is colored green, yellow, or red, providing an immediate visual identification of the greenest and least green stages of a method [10]. A significant drawback of the original GAPI was the lack of a single overall score, making direct comparison of two methods challenging [34]. This has been addressed by recent modifications like MoGAPI (Modified GAPI), which calculates a total percentage score, classifying methods as excellent green (≥75), acceptable green (50–74), or inadequately green (<50) [34].

The Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric is considered one of the most advanced tools. It calculates a score from 0 to 1 based on all 12 principles of GAC (represented by the mnemonic SIGNIFICANCE) [32]. The output is a user-friendly, clock-like pictogram where each segment corresponds to one principle. The color of each segment (red-to-green) shows performance for that principle, and the segment width reflects its user-defined weight [32]. A major strength is the availability of free, open-source software that simplifies the calculation and generation of the pictogram [32] [35]. However, it does not deeply cover pre-analytical processes like reagent synthesis [10].

Specialized Metric: AGREEprep for Sample Preparation

AGREEprep is the first dedicated metric for evaluating the sample preparation step, which is often the most resource- and waste-intensive part of an analysis [36] [37]. It is based on the 10 principles of Green Sample Preparation (GSP) [37]. Like AGREE, it uses a round pictogram with a central score from 0 to 1 and colored segments for each criterion. It also offers flexible weighting and is supported by dedicated software [36] [37]. As it focuses solely on sample preparation, it should be used in conjunction with a whole-method metric like AGREE for a complete assessment [10].

Experimental Protocols for Metric Application

Applying these metrics requires a systematic approach to data collection from the analytical method being evaluated. Below is a generalized protocol.

Data Collection and Input

Step 1: Define the Analytical Workflow. Break down the method into discrete steps: sampling, transport, storage, sample preparation (e.g., extraction, purification), and final instrumental analysis (e.g., HPLC, UPLC) [34].

Step 2: Quantify Material Consumption.

- Record the type and exact volumes/weights of all solvents, reagents, and materials (e.g., sorbents, filters) used per sample [36] [31].

- For AGREEprep, this is critical for calculating the amount of waste generated [36].

Step 3: Identify Hazard Profiles.

- Consult Safety Data Sheets (SDS) to determine the hazard pictograms (e.g., toxic, corrosive, flammable) and toxicity data for all chemicals used [32] [31]. This information is essential for nearly all metrics, particularly AES, GAPI, and AGREE.

Step 4: Calculate Energy Consumption.

- Estimate the energy consumption in kWh per sample. This can be calculated based on the power rating of instruments (e.g., HPLC oven, centrifuge, evaporator) and their total runtime per sample [32] [31].

Step 5: Characterize Method Performance.

- Note parameters like sample throughput (samples per hour), degree of automation, and whether the analysis is direct, in-line, at-line, or off-line [32] [37]. These factors influence several principles in AGREE and AGREEprep.

Metric Calculation and Visualization

Step 6: Select and Apply the Metric(s).

- Input the collected data into the chosen metric's framework or software.

- For a holistic view, use a combination of tools (e.g., AGREE for the whole method and AGREEprep for a deep dive into the sample preparation step) [10].

Step 7: Generate and Interpret the Output.

- Use the available software for AGREE, AGREEprep, and MoGAPI to automatically generate the final pictogram and score [32] [34] [35].

- Interpret the results by identifying segments colored red or yellow in the pictogram, as these highlight specific aspects of the method that have the largest environmental impact and greatest potential for improvement [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit for Green Assessment

Successfully implementing greenness assessment requires both conceptual tools and practical resources. The following table lists key solutions used in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Tools for Greenness Assessment

| Tool / Solution Name | Function in Greenness Assessment |

|---|---|

| AGREE Software [32] [35] | Free, open-source calculator that simplifies data input, automatically computes the final score (0-1), and generates the characteristic clock-like pictogram. |

| AGREEprep Software [36] | Dedicated, open-source software for evaluating sample preparation steps based on the 10 principles of GSP, providing a quantitative score and pictogram. |

| MoGAPI Software [34] | Freely available online tool that applies the Modified GAPI protocol, delivering both the colored pentagram and an overall percentage score for easier method comparison. |

| Chemical Safety Data Sheets (SDS) | Primary source for determining hazard classifications, toxicity, and Persistence, Bioaccumulation, and Toxicity (PBT) data of reagents, which are critical inputs for penalty points in AES and scores in GAPI/AGREE. |

| National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) Diamonds | Standardized hazard rating system sometimes used by metrics like the Assessment of Green Profile (AGP) to categorize the health, flammability, and reactivity hazards of chemicals [31]. |

The landscape of greenness assessment metrics has evolved significantly, moving from the basic binary evaluation of NEMI to the comprehensive, software-driven, and quantitative approaches of AGREE and its specialized counterpart, AGREEprep. For researchers comparing analytical techniques like UPLC and HPLC, selecting the right metric is crucial. While GAPI provides an excellent visual overview of the entire method's environmental hotspots, AGREE offers a more nuanced and numerically comparable score. For methods involving complex extraction or derivation, supplementing a whole-method metric with AGREEprep is highly recommended. By integrating these tools into regular methodological development and validation, scientists and drug development professionals can make informed, sustainable choices that align with the core principles of Green Analytical Chemistry.

A Deep Dive into the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) Metric

The growing emphasis on environmental responsibility has made Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) a strategic priority in laboratories worldwide. GAC aims to reduce the environmental impact of analytical procedures by promoting safer chemicals, minimizing waste, conserving energy, and improving method efficiency without compromising analytical performance [2]. To support this transition, several greenness assessment tools have been developed, among which the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric has emerged as a comprehensive and widely adopted tool for evaluating the environmental footprint of analytical methods [2].

Introduced in 2020, AGREE provides a holistic, quantitative evaluation based on all 12 principles of GAC. Its algorithm generates a single score on a scale from 0 to 1, accompanied by an intuitive radial diagram that offers immediate visual feedback. This output allows for rapid benchmarking and method optimization, ensuring alignment with green chemistry principles [2]. The tool's capacity to integrate multiple environmental parameters into a unified assessment has made it particularly valuable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to implement more sustainable analytical practices in their workflows [2].

The 12 Principles of Green Analytical Chemistry

AGREE's assessment framework is built upon the 12 foundational principles of GAC, which provide a structured approach to developing environmentally conscious analytical methods. The following diagram illustrates these principles and their relationships within the AGREE evaluation system:

AGREE in Context: Comparison with Other Green Assessment Tools

While AGREE offers a comprehensive approach to environmental assessment, it is most effectively used alongside other metrics that evaluate different dimensions of analytical method quality. The concept of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) proposes a balanced assessment using a Red-Green-Blue (RGB) model, where "white" methods demonstrate optimal balance between analytical performance (Red), environmental impact (Green), and practical applicability (Blue) [4].

Comparative Analysis of Green Assessment Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of Major Greenness Assessment Tools in Analytical Chemistry

| Tool | Graphical Output | Assessment Focus | Output Type | Key Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE | Radial chart | All 12 GAC principles | Quantitative score (0-1) + visual | Holistic single-score metric | [2] |

| GAPI | Color-coded pictogram | Entire analytical workflow | Semi-quantitative | Easy visualization, no total score | [2] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Numerical score | Reagent toxicity, energy, waste | Semi-quantitative | Penalty-point system | [2] |

| NEMI | Pictogram (blank/filled circles) | Solvent toxicity, waste, corrosiveness | Qualitative | Simplest metric, limited scope | [8] |

| AGREEprep | Pictogram + score | Sample preparation only | Quantitative score (0-1) | First dedicated sample prep metric | [2] |

Complementary Assessment Tools

To achieve a balanced evaluation of analytical methods, AGREE should be complemented with tools that assess other critical dimensions:

Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI): Focuses on analytical performance criteria including repeatability, intermediate precision, reproducibility, selectivity/specificity, linearity, accuracy, range, robustness, limit of detection, and limit of quantification. It generates a star-like pictogram with a final mean quantitative assessment score (0-100) [4].

Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI): Evaluates practicality and economic factors such as analysis type, throughput, reagent availability, automation, and sample preparation. It provides both a numeric score and a visual "asteroid" pictogram [2].

The integration of AGREE with RAPI and BAGI enables a comprehensive RGB assessment that aligns with the White Analytical Chemistry concept, ensuring methods are not only environmentally sustainable but also analytically sound and practically viable [4].

Experimental Applications and Protocol Evaluation

AGREE Assessment of Pharmaceutical Analysis Methods

Recent studies across pharmaceutical analysis demonstrate AGREE's application in evaluating and comparing the greenness of various analytical methods:

Table 2: AGREE Scores in Recent Pharmaceutical Method Developments

| Analytical Method | Application | AGREE Score | Key Green Features | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RP-HPLC | Lobeglitazone sulphate & glimepiride in tablets | >0.7 | Reduced solvent consumption, ethanol-based mobile phase | [38] |

| RP-HPLC (QbD approach) | Neratinib in bulk & formulations | >0.7 | Optimized solvent usage, reduced waste generation | [39] |

| UPLC/MS/MS | Captopril, hydrochlorothiazide & impurities | >0.8 | Reduced analysis time (1 min), minimal solvent consumption | [8] |

| HPLC-fluorescence | Sacubitril & valsartan in dosage form & plasma | >0.7 | Ethanol-based mobile phase, isocratic elution | [40] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: UPLC/MS/MS Method for Antihypertensive Agents

A recent study developed and validated a UPLC/MS/MS method for the simultaneous determination of two antihypertensive agents and their harmful impurities, with detailed greenness assessment using AGREE and other metrics [8].

Chromatographic Conditions

- Instrumentation: UPLC/MS/MS "Acquity Waters" 3100 with triple quadrupole detector

- Column: Agilent Poroshell 120 EC-C18 (4.6 × 50 mm, 2.7 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Methanol and 0.1% formic acid (90:10, v/v)

- Flow Rate: 0.7 mL/min

- Analysis Time: 1 minute

- Detection: Tandem mass spectrometry with positive mode for captopril and negative mode for hydrochlorothiazide and impurities

Sample Preparation

- Standards: Prepared in methanol at concentration ranges of 50.0-500.0 ng/mL for captopril and 20.0-500.0 ng/mL for hydrochlorothiazide

- Extraction: Simple dilution and filtration approach

- Volume Consumed: Minimal sample volumes required due to high sensitivity of MS detection

Method Validation Results

- Linearity: Demonstrated with R² > 0.999 for all analytes

- Sensitivity: LOD values in ng/mL range suitable for impurity detection at pharmacopeial limits

- Accuracy: Recovery rates within 98-102% for all compounds

- Precision: RSD values <2% for both intra-day and inter-day precision

Greenness Assessment with AGREE

The AGREE evaluation of this method highlighted several strong green credentials:

- Rapid analysis (1 minute) significantly reduces energy consumption

- Minimal solvent consumption due to reduced flow rate (0.7 mL/min) and short runtime

- Efficient separation without need for extensive sample preparation

- Reduced waste generation compared to conventional HPLC methods

The method achieved an AGREE score >0.8, indicating excellent greenness performance, primarily attributed to the combination of UPLC technology for faster separations and MS detection for enhanced sensitivity without extensive sample preparation [8].

UPLC vs HPLC: A Greenness Perspective

The transition from conventional HPLC to UPLC systems represents a significant advancement in green analytical chemistry, which is clearly demonstrated through AGREE assessments.

Direct Comparative Study

A 2025 study directly compared AI-predicted HPLC methods with experimentally optimized approaches for analyzing amlodipine, hydrochlorothiazide, and candesartan. The AGREE assessment clearly demonstrated the superior greenness of the optimized method, which utilized:

- Faster analysis times (2.82 minutes maximum retention vs 12.12 minutes in AI-predicted method)

- Reduced solvent consumption through higher flow rates and optimized mobile phase composition

- Superior energy efficiency due to shorter runtimes [41]

Advantages of UPLC for Green Analytical Chemistry

UPLC systems consistently demonstrate better environmental performance in AGREE assessments due to several technological advantages:

Higher Efficiency Separations: UPLC columns with smaller particle sizes (<2μm) provide superior separation efficiency, allowing shorter analysis times and reduced solvent consumption [8].

Reduced Solvent Consumption: Typical UPLC methods use 30-70% less solvent compared to conventional HPLC methods, directly addressing GAC principles of waste minimization [8].

Shorter Analysis Times: Rapid separations (often 1-5 minutes versus 10-30 minutes for HPLC) significantly reduce energy consumption per sample [8] [41].

Enhanced Sensitivity: Improved detection capabilities often eliminate the need for extensive sample preparation and concentration steps, reducing overall chemical usage [8].

The environmental benefits of UPLC are quantitatively demonstrated through higher AGREE scores, typically ranging between 0.7-0.8 for UPLC methods compared to 0.5-0.7 for conventional HPLC methods analyzing similar compounds [8] [41].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green HPLC/UPLC Methods

The implementation of green chromatographic methods requires careful selection of reagents and materials to align with GAC principles while maintaining analytical performance.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green Chromatographic Methods

| Reagent/Material | Function | Green Alternatives | Environmental Benefit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Organic mobile phase component | Ethanol, methanol | Lower toxicity, better biodegradability | [38] [40] |

| Methanol | Organic mobile phase component | Ethanol | Reduced toxicity, renewable sourcing | [38] |

| Phosphate buffers | Aqueous mobile phase component | Ammonium formate | Better MS compatibility, reduced disposal concerns | [39] |

| Formic acid | Mobile phase modifier | Trifluoroacetic acid alternatives | Reduced environmental persistence | [8] |

| C18 columns | Stationary phase | Core-shell technology columns | Higher efficiency, lower backpressure | [8] [41] |

| Traditional HPLC columns (5μm) | Stationary phase | UPLC columns (1.7-2μm) | Shorter analysis times, reduced solvent consumption | [8] [41] |

The AGREE metric has established itself as an indispensable tool for the objective evaluation of environmental sustainability in analytical chemistry, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where regulatory compliance and method validation are paramount. Its comprehensive approach, which encompasses all 12 principles of Green Analytical Chemistry within a quantitative framework, provides researchers with a scientifically sound basis for method development and optimization.

The comparative assessment of UPLC and HPLC methods through AGREE has consistently demonstrated the environmental advantages of modern chromatographic technologies. UPLC methods generally achieve higher AGREE scores due to reduced solvent consumption, shorter analysis times, and lower energy requirements. However, the ultimate selection of analytical methodology should balance environmental considerations with analytical performance requirements and practical applicability, ideally using a combination of AGREE, RAPI, and BAGI assessments.

As the field of green analytical chemistry continues to evolve, AGREE will likely play an increasingly important role in guiding the development of sustainable analytical methods that minimize environmental impact while maintaining the high standards of accuracy, precision, and reliability required in pharmaceutical analysis and other scientific disciplines.

Applying the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) for a Holistic Workflow View

The principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have become a cornerstone of modern method development, aiming to minimize the environmental impact of analytical procedures without compromising performance [2]. Within this framework, the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI) has emerged as a powerful semi-quantitative tool that provides a visual assessment of the environmental impact across the entire analytical workflow [10]. GAPI employs a color-coded pictogram that evaluates each stage of an analytical method, from sample collection and preparation to final detection and analysis [2]. This holistic approach enables researchers to quickly identify areas with the highest environmental impact and prioritize improvements for more sustainable method development.

The application of GAPI is particularly relevant when comparing established and emerging chromatographic techniques, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UPLC). As analytical laboratories face increasing pressure to reduce their environmental footprint while maintaining high throughput and sensitivity, tools like GAPI provide critical insights for making informed decisions about method selection and optimization [10]. This guide explores how GAPI facilitates a direct comparison between HPLC and UPLC methods, offering a structured approach to evaluating their environmental performance within pharmaceutical research and drug development contexts.

The GAPI Framework: Structure and Interpretation