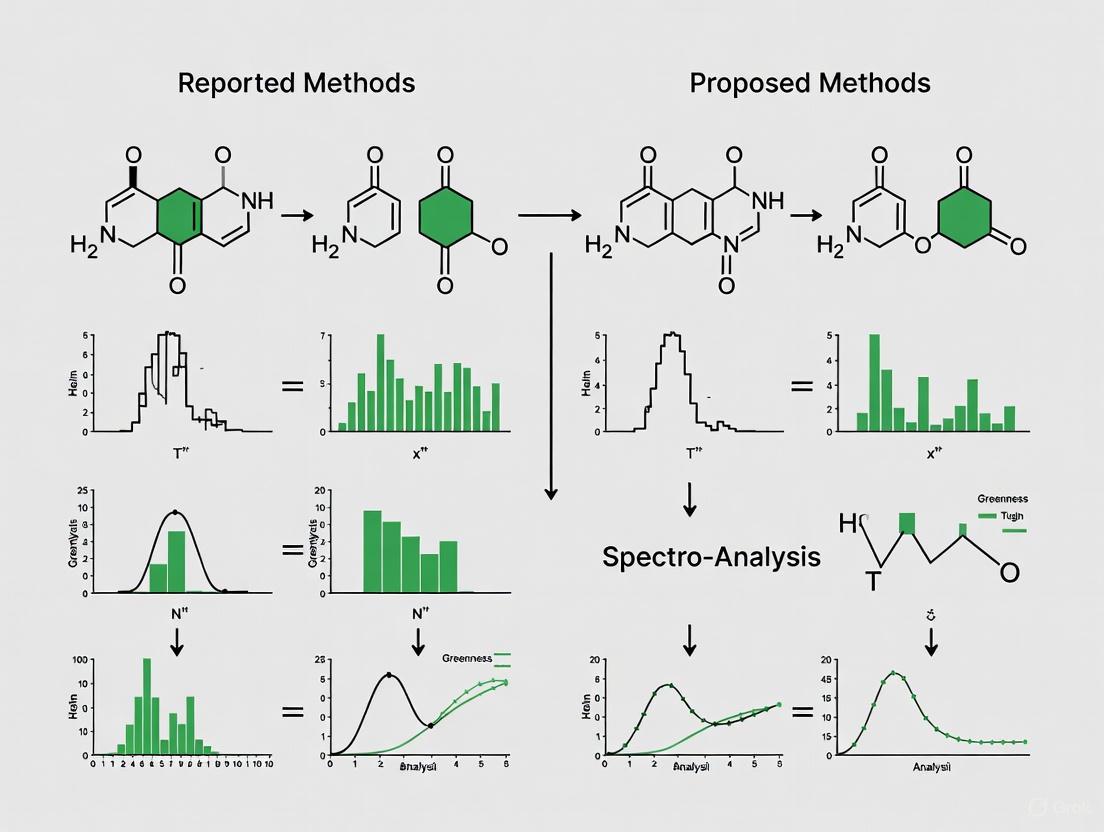

Greenness Profile Comparison in Pharmaceutical Analysis: A Comprehensive Framework for Evaluating Reported vs. Proposed Methods

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for conducting greenness profile comparisons between reported and newly proposed analytical methods.

Greenness Profile Comparison in Pharmaceutical Analysis: A Comprehensive Framework for Evaluating Reported vs. Proposed Methods

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a systematic framework for conducting greenness profile comparisons between reported and newly proposed analytical methods. It explores the foundational principles of Green and White Analytical Chemistry (GAC/WAC), details the application of modern assessment tools like AGREE, GAPI, and NEMI, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes robust validation protocols. Through case studies and comparative analyses, the content demonstrates how to balance environmental sustainability with analytical performance and practical feasibility, empowering scientists to make informed, eco-conscious decisions in analytical method development and selection.

The Principles of Green and White Analytical Chemistry: Building a Sustainable Foundation

The concept of green chemistry, formally established in the 1990s, created a transformative framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use and generation of hazardous substances [1] [2]. This philosophy has since permeated all chemical disciplines, including analytical chemistry, which traditionally relied on resource-intensive methods, toxic solvents, and energy-consuming instrumentation. Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) emerged as a dedicated subfield to address these specific environmental concerns within analytical practice [3]. Initially focused on minimizing the environmental footprint of analytical methods, GAC has evolved from a simple set of guidelines into a sophisticated, metrics-driven discipline essential for modern sustainable science [4]. This evolution reflects a broader shift in the chemical industry and research sectors toward aligning laboratory practices with the principles of sustainable development, ecological preservation, and workplace safety [3] [5]. This guide examines the core principles of GAC, traces its development, and provides a comparative analysis of the tools and metrics used to evaluate the greenness of analytical methods, with a special focus on applications relevant to pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles: The Foundation of Green Analytical Chemistry

The foundational framework for GAC is derived directly from the twelve principles of green chemistry, which have been adapted to address the specific needs and challenges of chemical analysis [3] [5]. These principles provide a comprehensive strategy for designing analytical methods that are safer, more efficient, and environmentally benign.

The primary goals of GAC include minimizing the consumption of reagents and solvents, reducing energy demands, avoiding toxic chemicals, preventing waste generation, enabling real-time analysis to prevent pollution, and prioritizing the safety of laboratory personnel [2] [5]. A key mantra within GAC is that the best waste is no waste at all, leading to a strong emphasis on waste prevention at the source rather than management after it is generated [3].

To visualize the logical relationships between the core principles and their implementation in analytical chemistry, the following diagram outlines the evolutionary pathway from broad green chemistry concepts to specific GAC principles and their practical applications.

Figure 1: Evolution from Green Chemistry to GAC and WAC Frameworks. This diagram traces the development from the foundational principles of Green Chemistry to the specialized field of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and its subsequent evolution into the more comprehensive White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) framework, which balances environmental, analytical, and practical considerations.

A pivotal development in implementing these principles has been the creation of the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic, which offers a practical framework for remembering and applying key green analytical practices [2]. This tool encapsulates the core objectives of GAC, making the principles more accessible and actionable for practicing analytical chemists in both research and industrial settings, including pharmaceutical quality control laboratories.

The Evolution of Assessment Metrics: Quantifying Greenness

A significant challenge in implementing GAC has been the quantification and comparison of the environmental friendliness of analytical methods. Early metrics developed for synthetic chemistry, such as the E-Factor (environmental factor), which measures the total waste produced per kilogram of product, were not directly transferable to analytical contexts [1]. This limitation spurred the development of dedicated metrics for analytical chemistry, leading to a proliferation of assessment tools with varying complexities and focus areas.

First-Generation Metrics

Initial tools were relatively simple and provided a quick, visual assessment of a method's greenness. The National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), for instance, uses a pictogram to indicate whether a method meets basic criteria regarding reagent toxicity, waste generation, and corrosiveness [1] [5]. While user-friendly, its binary (pass/fail) nature and limited scope offered low resolution for differentiating between methods.

Comprehensive Second-Generation Metrics

The need for more nuanced assessment led to the development of sophisticated metrics that evaluate multiple parameters across the entire analytical process. Key among these are:

- Analytical Eco-Scale: A semi-quantitative tool that penalizes methods for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste, providing a final score where a higher number indicates a greener method [1].

- Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI): Employs a multi-section pictogram to assess environmental impact at each stage of the analytical process, from sampling to final determination [2] [5].

- Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) Metric: A comprehensive tool that uses the twelve principles of GAC as assessment criteria, generating a final score from 0 to 1. Its visual output is a circular diagram where each segment's color intensity corresponds to the performance in that principle [5].

The table below provides a structured comparison of the most prominent GAC metrics, highlighting their methodologies, outputs, and key differentiators.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Metrics

| Metric Name | Methodology & Scoring | Output Format | Key Parameters Assessed | Primary Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [1] [5] | Binary assessment (pass/fail) of 4 criteria. | Quadrant pictogram; each quadrant filled if criterion met. | PBT reagents, corrosive, hazardous waste. | Simple, quick, visual. | Low resolution, limited scope, no energy consideration. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [1] | Penalty points subtracted from 100 for hazardous elements. | Numerical score (higher = greener). | Reagent toxicity, waste, energy, safety. | Semi-quantitative, easy result interpretation. | Subjectivity in assigning penalties. |

| GAPI [2] [5] | Qualitative assessment of 5 lifecycle stages. | Multi-colored pictogram with up to 15 fields. | Sample prep, reagents, instrumentation, waste. | Holistic, covers entire method lifecycle. | Qualitative, less suited for direct numerical comparison. |

| AGREE [5] | Scores 12 principles of GAC (0-1). | Circular diagram with 12 sections & overall score (0-1). | All GAC principles, including in-situ analysis, safety. | Most comprehensive, aligns perfectly with GAC principles. | Requires dedicated software, more complex input. |

| ComplexGAPI [2] | Extends GAPI with additional criteria. | Enhanced pictogram with more fields than GAPI. | Includes more detailed environmental and health impacts. | More detailed than GAPI. | Still qualitative, relatively new. |

The Rise of White Analytical Chemistry: A Holistic Framework

A significant recent evolution in the field is the introduction of White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), a paradigm designed to address a key limitation of traditional GAC: the potential trade-off between environmental sustainability and analytical performance or practical feasibility [2] [6]. WAC adopts a holistic RGB model, where "white" light is achieved by balancing three primary color components:

- Red (Analytical Performance): Encompasses traditional validation parameters such as accuracy, precision, sensitivity (LOD, LOQ), selectivity, and linearity [7].

- Green (Environmental Sustainability): Incorporates all the principles and metrics of conventional GAC.

- Blue (Practical & Economic Feasibility): Considers cost, analysis time, operational simplicity, safety for the operator, and energy requirements [2].

Under the WAC framework, an ideal "white" method excels in all three dimensions. This balanced perspective is particularly crucial in regulated environments like pharmaceutical quality control, where a method must not only be green but also robust, reliable, and cost-effective [2]. The advent of WAC has also spurred the development of dedicated assessment tools for its red and blue components, such as the Red Analytical Performance Index (RAPI) and the Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI), which work alongside established greenness metrics to provide a complete RGB profile [7].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

For researchers conducting greenness profile comparisons between reported and newly proposed methods, a standardized protocol is essential. The following workflow, applicable to techniques like HPLC/UPLC, provides a detailed methodology for a comprehensive assessment.

Experimental Workflow for Method Comparison

The diagram below illustrates a standardized protocol for comparing the greenness profiles of established and newly proposed analytical methods, integrating both GAC and WAC principles.

Figure 2: GAC and WAC Method Assessment Workflow. This workflow outlines the key steps for systematically comparing the greenness and overall suitability of analytical methods, from data collection to final synthesis of results.

Data Collection Protocol

The foundation of any greenness assessment is accurate, quantitative data collected for both the established method and the proposed alternative. Key data points include:

- Solvent Consumption: Total volume (mL) per analysis, including extraction, dilution, and mobile phase solvents. Note the identity and hazard classifications of each solvent [3] [8].

- Reagent Consumption: Mass (mg) of all derivatization agents, buffers, and catalysts used per analysis.

- Energy Consumption: Total analysis time (minutes) and instrument power requirements (kW). The total energy is often calculated as

Analysis Time × Power Rating[3]. - Waste Generation: Total mass (g) or volume (mL) of waste generated per analysis, including solvent wastes, solid phases, and contaminated samples.

- Analytical Performance Parameters: From method validation: Linear Range, LOD, LOQ, Accuracy (% Recovery), Precision (% RSD) [7].

Application of Metrics and Tools

Using the collected data, researchers apply the selected metrics. For software-based tools like AGREE and RAPI, this involves inputting the specific data points into the available software [7] [5]. For pictogram-based tools like GAPI, the analyst qualitatively assesses each category based on the method's procedural details. The output from these tools provides the basis for a comparative analysis, which should be summarized in a clear table.

Table 2: Sample Greenness Profile Comparison: Traditional vs. Green HPLC Method for Drug Analysis

| Assessment Parameter | Traditional HPLC Method | Proposed Green UHPLC Method |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Consumption | 10 mL/acetonitrile per run | 2 mL/ethanol-water per run |

| Total Waste Generated | ~120 g per analysis | ~25 g per analysis |

| Energy Demand | 25 min × 1.2 kW = 30 kJ | 5 min × 1.5 kW = 7.5 kJ |

| NEMI Pictogram | 2/4 quadrants filled | 4/4 quadrants filled |

| AGREE Score | 0.45 | 0.78 |

| Analytical Performance (RAPI) | Accuracy: 98.5%, Precision: 1.8% RSD | Accuracy: 99.2%, Precision: 2.1% RSD |

| Practicality (BAGI Score) | 65 (Moderately practical) | 85 (Highly practical) |

| Overall WAC Assessment | Suboptimal (Weak Green & Blue) | Well-balanced, near "White" |

Note: The data in this table is illustrative, based on common trends observed in method comparisons reported in the literature [2] [8] [5].

For researchers and drug development professionals aiming to implement GAC and WAC principles, a suite of modern tools and concepts is essential. The following table details key solutions that form the foundation of a sustainable analytical laboratory.

Table 3: Research Reagent and Tool Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Tool / Solution | Category | Primary Function in GAC | Relevance to Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids / Deep Eutectic Solvents | Green Solvent | Replace volatile organic solvents (VOCs) in extraction; lower toxicity and volatility [3]. | Safer sample prep for bioanalysis (plasma, urine). |

| Supercritical Fluid Chromatography (SFC) | Instrumental Technique | Uses supercritical CO₂ (non-toxic) as primary mobile phase; reduces organic solvent use by >80% [3]. | Ideal for chiral separations and purification in API development. |

| AGREE Software | Assessment Metric | Quantifies method greenness against all 12 GAC principles; provides visual and numerical score [5]. | Justifying environmental benefits of new analytical methods in regulatory submissions. |

| RAPI & BAGI Software | Assessment Metric | Assesses analytical performance (Red) and practical/economic factors (Blue) for a holistic WAC view [7]. | Ensuring new methods are not only green but also robust, accurate, and cost-effective for QC. |

| Automated Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) | Sample Prep | Miniaturizes and automates extraction; eliminates solvent use; integrates sampling & concentration [3] [8]. | High-throughput analysis of active compounds and metabolites in complex matrices. |

| Microwave-/Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction | Energy-Efficient Process | Uses alternative energy to accelerate extraction, reducing time and energy consumption vs. Soxhlet [3] [8]. | Efficient extraction of active ingredients from natural products for drug discovery. |

The evolution from Green Chemistry to Green Analytical Chemistry represents a critical maturation of sustainability within analytical science. The field has moved beyond general principles to a robust, metrics-driven discipline capable of quantitatively evaluating and comparing the environmental impact of analytical methods. The emergence of White Analytical Chemistry and its RGB model marks the next evolutionary step, addressing the crucial need to balance environmental sustainability with uncompromised analytical performance and practical feasibility. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these concepts and tools—from AGREE and GAPI to RAPI and BAGI—is no longer optional but essential for developing future-proof, responsible, and efficient analytical methods that meet the dual demands of scientific excellence and environmental stewardship. The ongoing innovation in green solvents, miniaturized instrumentation, and automated workflows promises to further reduce the ecological footprint of chemical analysis, solidifying its role in achieving broader sustainability goals.

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) represents a significant evolution in the field of sustainable science, moving beyond the purely environmental focus of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) to advocate for a more balanced approach. This modern framework ensures that analytical methods are not only environmentally responsible but also analytically powerful and practically feasible. WAC integrates these three pillars—environmental, functional, and practical—using an intuitive RGB (Red, Green, Blue) color model to achieve a "white" or perfect balance [9] [6] [10].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of WAC against traditional methods, complete with experimental data and protocols, to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their pursuit of truly sustainable and effective analytical processes.

The RGB Model: The Three Pillars of WAC

The core of the WAC concept is the RGB model, where each color represents a fundamental dimension for evaluating an analytical method [9]:

- Red - Analytical Performance: This dimension assesses the technical quality and effectiveness of the method. It ensures that the pursuit of sustainability does not compromise the core analytical results [9] [10].

- Green - Environmental Impact: This pillar is inherited from GAC and focuses on minimizing the ecological footprint of analytical processes. It evaluates the use of toxic reagents, energy consumption, and waste generation [11] [9].

- Blue - Practicality & Economics: This dimension addresses the practical aspects of implementing the method in real-world settings, including cost, time, simplicity, and operational safety [9] [10].

A method is considered "white" when it achieves a harmonious balance among all three criteria. The resulting color from mixing the Red, Green, and Blue assessments visually indicates how close a method is to this ideal state [9].

Detailed Experimental Protocols: WAC in Action

The following case studies illustrate how WAC principles are applied in real experimental research, from method development to validation.

Protocol 1: Chromatographic Determination of Mupirocin in Binary Mixtures

A 2023 study developed and validated two chromatographic methods for determining Mupirocin (MUP) in complex topical ointments, providing a clear example of WAC principles in practice [12].

- Objective: To develop precise HPTLC and RP-HPLC methods for quantifying MUP in the presence of other drugs (Fluticasone propionate or Mometasone furoate) and their impurities, while evaluating environmental impact [12].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Sample Preparation: MUP and impurity standard stock solutions were prepared in methanol. Pharmaceutical ointments were weighed, sonicated with methanol to extract the active ingredients, and filtered [12].

- HPTLC-Densitometry Method:

- Stationary Phase: HPTLC plates pre-coated with silica gel 60 F254.

- Mobile Phase: Toluene, chloroform, and ethanol in a ratio of 5:4:2 by volume.

- Detection: Scanned at 220 nm for MUP and 254 nm for other components [12].

- RP-HPLC Method:

- Column: Agilent Eclipse XDB C18 column.

- Mobile Phase & Elution: A stepwise gradient elution was used for one mixture (Methanol:Sodium di-hydrogen phosphate, pH 3.0) and an isocratic elution for another.

- Flow Rate: 1 mL/min.

- Detection: Photodiode Array Detector at different wavelengths for different analytes [12].

- Validation: Both methods were validated per International Council on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, confirming linearity, accuracy, precision, and specificity [12].

Protocol 2: Eco-Friendly Spectrofluorimetric Determination of Nitazoxanide

A 2022 study created a sensitive and green spectrofluorimetric method for quantifying the antiparasitic drug Nitazoxanide (NTZ), showcasing the balance between analytical performance and sustainability [13].

- Objective: To establish a simple, sensitive, and eco-friendly method for quantifying NTZ in dosage forms and human plasma [13].

- Experimental Workflow:

- Principle: Native NTZ is non-fluorescent. The method is based on its reduction with zinc powder in acidic medium to form a highly fluorescent product [13].

- Procedure:

- Reduction: 1.0 mL of NTZ working solution was mixed with 1.5 mL of concentrated HCl and 0.4 g of zinc powder.

- Reaction: The mixture was left to stand for 15 minutes with gentle shaking.

- Filtration: The reaction product was filtered.

- Analysis: The filtrate was diluted with methanol, and fluorescence was measured at an emission wavelength of 440 nm after excitation at 299 nm [13].

- Application: The method was successfully applied to analyze commercial tablets and human plasma samples, with bio-analytical validation performed according to European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidelines [13].

Comparative Analysis: WAC vs. Traditional Assessment

Quantitative Greenness Profile Comparison

The following table summarizes the greenness scores of the NTZ spectrofluorimetric method compared to other reported methods, as evaluated by four different assessment tools [13].

Table 1: Comparative Greenness Assessment of Methods for Nitazoxanide (NTZ) Determination

| Assessment Tool | Proposed Spectrofluorimetric Method [13] | Reported HPLC Method [13] | Reported Voltammetry Method [13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | ✓✓✓✓ (All criteria passed) | ✓✓✓✗ (One criterion failed) | ✓✓✗✗ (Two criteria failed) |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | 85 (Excellent) | 65 (Acceptable) | 55 (Unacceptable) |

| GAPI | (Green) | (Yellow) | (Red) |

| AGREE Score | 0.82 | 0.54 | 0.45 |

Conclusion: The proposed WAC-friendly spectrofluorimetric method demonstrated superior greenness across all metrics, achieving a high AGREE score of 0.82, indicating an "excellent green method" [13].

Comprehensive WAC Evaluation of Chromatographic Methods

The two chromatographic methods for Mupirocin were evaluated against the full WAC criteria, with their profiles summarized below [12].

Table 2: White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) Assessment of Chromatographic Methods

| WAC Criterion | HPTLC-Densitometry Method [12] | RP-HPLC Method [12] |

|---|---|---|

| Red (Analytical Performance) | ||

| - Linearity (Range) | 0.1-1.0 μg/band | 1-100 μg/mL |

| - Accuracy (% Recovery) | 99.5 - 100.8% | 98.9 - 101.2% |

| - Precision (% RSD) | < 1.5% | < 2.0% |

| Green (Environmental Impact) | ||

| - Solvent Consumption (per analysis) | ~10 mL | ~15 mL |

| - Solvent Toxicity | Moderate (Toluene, Chloroform) | Lower (Methanol, Buffer) |

| - Waste Generation | Low | Moderate |

| Blue (Practicality & Economics) | ||

| - Sample Throughput | High (Parallel) | Medium (Sequential) |

| - Cost per Analysis | Low | Medium |

| - Operational Simplicity | High | Medium |

| - Total Analysis Time | ~30 minutes | ~20 minutes |

Conclusion: The HPTLC method excels in sample throughput and cost (Blue), while the HPLC method offers a wider linear range and may use less toxic solvents (Green). The choice depends on the laboratory's specific priorities, perfectly illustrating the need for WAC's balanced evaluation [12].

The Analytical Toolkit: Metrics for Sustainable Science

The transition to sustainable analytics is supported by various assessment tools. The table below describes key metrics used in the field.

Table 3: Essential Tools for Greenness and WAC Assessment

| Tool Name | Primary Focus | Key Function & Output |

|---|---|---|

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [13] | Comprehensive Greenness | Evaluates all 12 GAC principles, providing a score from 0-1 and a colored pictogram. |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [12] | In-depth Greenness | Uses a pictogram with 5 pentagrams to detail environmental impact across the method's lifecycle. |

| NEMI (National Environmental Method Index) [12] | Basic Green Profile | A simple pictogram showing whether a method is Persistent, Bioaccumulative, Toxic, and/or Corrosive. |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [12] | Greenness Penalty Score | Assigns penalty points to un-green practices; a score above 75 is considered an excellent green method. |

| BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) [9] | Practicality (Blue) | Assesses practical aspects like cost, time, and operational simplicity, outputting a blue-shaded pictogram. |

WAC Workflow and Signaling Pathway

The following diagram visualizes the logical pathway and decision-making process for developing an analytical method based on White Analytical Chemistry principles. It illustrates how the Red, Green, and Blue criteria are integrated and balanced to achieve the ideal "white" method.

Diagram Title: The WAC Method Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key materials and reagents used in the featured WAC experiments, with explanations of their roles.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function in the Experiment | Example from Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc (Zn) Powder | Acts as a reducing agent in acidic medium to convert a non-fluorescent compound into a fluorescent one for detection. | Used to reduce Nitazoxanide for spectrofluorimetric analysis [13]. |

| Silica Gel 60 F254 HPTLC Plates | The stationary phase for Thin-Layer Chromatography, enabling the separation of mixture components. | Used to separate Mupirocin, other drugs, and their impurities [12]. |

| C18 Reverse-Phase Column | The standard stationary phase for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), separating compounds based on hydrophobicity. | Agilent Eclipse XDB C18 column used for chromatographic separation of mixtures [12]. |

| Methanol & Acetonitrile | Common organic solvents used for preparing standard solutions, sample extraction, and as components of the mobile phase. | Used in sample preparation and as part of the mobile phase in both HPTLC and HPLC protocols [12] [13]. |

White Analytical Chemistry marks a necessary evolution in analytical science. By mandating a balanced consideration of the Red (performance), Green (environmental), and Blue (practical) dimensions, WAC provides a holistic framework for developing methods that are not only scientifically valid but also environmentally responsible and economically viable [11] [9] [6]. As demonstrated by the comparative data, methods aligned with WAC principles can successfully achieve high analytical performance while minimizing their ecological footprint. For researchers in drug development and beyond, adopting the WAC framework is a crucial step towards truly sustainable and efficient scientific progress.

The growing emphasis on environmental responsibility has fundamentally transformed analytical chemistry, leading to the establishment of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) as a dedicated discipline focused on minimizing the environmental impact of analytical practices [14] [15]. While GAC provides a crucial foundation for sustainability, its primary focus on ecological concerns sometimes overlooks other critical aspects of method utility, such as analytical performance and practical feasibility. To address this limitation, White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) has emerged as a holistic framework that integrates environmental, performance, and practical considerations [11] [15]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these two frameworks, focusing on two cornerstone concepts: the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic of GAC and the RGB model of WAC. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this comparison explores the principles, assessment tools, and practical applications of both approaches to guide the selection and development of truly sustainable and effective analytical methods.

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) and the SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic

Core Principles and the SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic

Green Analytical Chemistry originated in 2000 as an extension of green chemistry principles specifically tailored to analytical techniques and procedures [14]. Its primary objective is to decrease or eliminate the use of dangerous solvents and reagents, reduce energy consumption, and minimize waste generation while maintaining robust method validation parameters [14] [15].

To provide a practical and memorable framework for implementing GAC principles, the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic was developed [15] [16]. This framework encapsulates the 12 core principles of GAC, offering a structured approach to greening analytical practices.

The diagram above illustrates the sequential relationship between the 12 principles encapsulated in the SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic, which provides a comprehensive framework for implementing GAC.

Table 1: The SIGNIFICANCE Mnemonic for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Letter | Principle | Core Concept |

|---|---|---|

| S | Select direct methods | Avoid sample treatment to prevent reagent consumption and waste generation [16] |

| I | Integrate processes | Combine analytical operations to save energy and reduce reagent use [16] |

| G | Generate no waste | Avoid waste generation or properly manage analytical waste [16] |

| N | Never waste energy | Minimize total energy requirements in the analytical process [16] |

| I | Implement automation | Prefer automated and miniaturized methods for efficiency [16] |

| F | Favor renewables | Choose reagents from renewable sources over depleting ones [16] |

| I | Increase operator safety | Enhance safety for the analyst through safer processes [16] |

| C | Carry out in-situ | Perform measurements directly at the sample location [16] |

| A | Avoid derivatization | Eliminate derivatization steps that require additional reagents [16] |

| N | Note minimal sample size | Use minimal sample sizes and minimal number of samples [16] |

| C | Choose multi-analyte methods | Prefer methods that can determine multiple analytes simultaneously [16] |

| E | Eliminate toxic reagents | Replace hazardous chemicals with safer alternatives [16] |

Key GAC Assessment Tools and Metrics

The implementation of GAC principles has been facilitated by the development of specialized assessment tools that help quantify the environmental footprint of analytical methods.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Assessing Greenness in Analytical Methods

| Assessment Tool | Type of Output | Key Parameters Assessed | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [14] [17] | Pictogram (four quadrants) | PBT chemicals, hazardous waste, corrosivity, waste amount | Simple, visual, quick assessment [17] | Binary (green/blank), limited scope, qualitative only [14] [17] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [14] [17] | Numerical score (0-100) | Reagent amount and hazard, energy, waste | Quantitative, enables direct comparison [14] | Relies on expert judgment for penalty points [14] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [14] [17] | Color-coded pictogram (5 sections) | Entire process from sampling to detection | Comprehensive, visual identification of high-impact stages [14] | No overall score, some subjectivity in color assignment [14] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness metric) [14] [17] | Numerical score (0-1) + circular pictogram | All 12 GAC principles | Comprehensive, user-friendly, facilitates comparison [14] | Limited pre-analytical process consideration [14] |

| AGREEprep [14] | Numerical score (0-1) + pictogram | Sample preparation-specific parameters | First dedicated sample preparation tool [14] | Must be used with broader tools for full method evaluation [14] |

White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) and the RGB Model

The RGB Model: A Triadic Approach

White Analytical Chemistry represents an evolutionary step beyond GAC by addressing its primary limitation: the potential trade-off between environmental sustainability and analytical performance [15]. WAC introduces a balanced, triadic approach known as the RGB model, which integrates three equally important dimensions [11] [15] [18].

The diagram above illustrates the three complementary dimensions of the WAC RGB model, which together create a balanced approach to analytical method evaluation.

The Red Component represents analytical performance, focusing on the quality and reliability of the results obtained. This dimension ensures that methods meet necessary standards for accuracy, precision, sensitivity, selectivity, and linear range [15] [18]. Without strong red attributes, a method fails its fundamental purpose regardless of its environmental benefits.

The Green Component encompasses the environmental impact of the method, directly incorporating the principles of GAC. This dimension addresses waste generation, energy consumption, reagent toxicity, and operator safety [15]. It aims to minimize the ecological footprint of analytical practices throughout their lifecycle.

The Blue Component addresses practical and economic feasibility, evaluating factors such as cost-efficiency, time-efficiency, operational simplicity, and availability of required instrumentation [18]. This dimension ensures that methods are not only scientifically sound and environmentally friendly but also practical for implementation in real-world laboratory settings.

When all three components are optimally balanced, the method achieves the desired "whiteness," representing an ideal synergy of performance, sustainability, and practicality [11] [15].

Key WAC Assessment Tools

The evaluation of whiteness requires specialized metrics that can simultaneously address all three dimensions of the RGB model.

BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index): This tool specifically assesses the blue component of WAC, evaluating practicality through 10 criteria including analysis type, number of analytes, sample throughput, automation, and reagent availability [18]. It provides a numerical score between 25 and 100, with scores above 60 indicating a genuinely practical method [18]. The tool generates a visual asteroid pictogram with sections colored dark blue, blue, light blue, or white based on the scores for each criterion [18].

Combined RGB Assessment: A comprehensive WAC evaluation typically involves using AGREE or GAPI for the green component, traditional validation parameters for the red component, and BAGI for the blue component [19]. The results are then integrated to determine the overall "whiteness" of the method and identify potential trade-offs between the three dimensions.

Comparative Analysis: GAC vs. WAC in Pharmaceutical Applications

Framework Comparison

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of GAC and WAC Frameworks

| Aspect | Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) | White Analytical Chemistry (WAC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Environmental impact minimization [15] | Balanced integration of three dimensions: Red, Green, and Blue [11] [15] |

| Core Principles | 12 principles encapsulated in SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic [16] | RGB model with approximately 12 principles distributed across three components [15] |

| Evaluation Approach | Unidimensional (Environmental impact) [15] | Multidimensional (Performance, Environment, Practicality) [11] [15] |

| Method Selection Criteria | Primarily based on greenness attributes | Holistic balance of analytical quality, sustainability, and practicality [15] |

| Potential Limitations | May compromise analytical performance for greenness [15] | More complex assessment requiring multiple metrics [15] |

| Industry Applicability | Suitable for initial environmental screening | Ideal for comprehensive method development and validation [15] |

Experimental Case Study: UV Spectrophotometric Methods for Pharmaceutical Analysis

A recent study developed five sustainable UV spectrophotometric methods for the simultaneous determination of chloramphenicol and dexamethasone sodium phosphate in ophthalmic formulations [19]. The methods employed different techniques including zero order, induce dual wavelength, Fourier self-deconvolution, ratio difference, and derivative ratio spectroscopy [19].

Experimental Protocol:

- Apparatus: Double-beam JASCO V-630 UV-visible spectrophotometer with 2 nm spectral slit width and 1000 nm/min scan speed [19].

- Reagents and Materials: Analytical grade ethanol was used as solvent; chloramphenicol and dexamethasone sodium phosphate reference standards were obtained from Orchidia Co. for Pharmaceutical Ind. (Cairo, Egypt) [19].

- Sample Preparation: Spersadex comp eye drops were diluted with ethanol to achieve working concentrations of 20.00 μg/mL for CHL and 4.00 μg/mL for DSP [19].

- Analysis: Different spectrophotometric techniques were applied based on the specific method being validated, with measurements taken between 200.0 and 400.0 nm [19].

Assessment Results: The methods were evaluated using both GAC and WAC metrics, with the zero order method for CHL achieving an Analytical Eco-Scale score of 82 (excellent green analysis) and an AGREE score of 0.76, indicating good environmental performance [19]. The BAGI assessment for practicality yielded scores ranging from 72.5 to 77.5 across the different techniques, confirming strong practicality (blueness) [19]. The integration of these metrics provided a comprehensive whiteness evaluation, demonstrating that the methods successfully balanced all three dimensions of the RGB model [19].

Research Reagent Solutions for Sustainable Analytical Chemistry

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Green and White Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in GAC/WAC | GAC/WAC Benefit | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | Green solvent for extraction and dilution [19] | Renewable, biodegradable, less toxic alternative to acetonitrile and methanol [19] | Solvent for spectrophotometric determination of chloramphenicol and dexamethasone [19] |

| Water | Solvent for chromatography and extraction | Non-toxic, readily available, zero hazardous waste | Alternative reverse-phase mobile phase component |

| Liquid Carbon Dioxide | Extraction solvent in SFE | Non-toxic, easily removed, replaces organic solvents | Supercritical fluid extraction of natural products |

| Ionic Liquids | Green solvents for extraction and separation | Low volatility, reducing air pollution and inhalation hazards [16] | Extraction media for metal ions and organic compounds |

| Biopolymers | Sorbents for sample preparation | Renewable, biodegradable solid-phase extraction materials | Molecularly imprinted polymers for selective extraction |

The comparison between Green Analytical Chemistry and White Analytical Chemistry reveals a natural evolution in sustainable analytical practices. While GAC provides a crucial foundation for environmental responsibility through its SIGNIFICANCE mnemonic and dedicated assessment tools, WAC offers a more comprehensive framework through its RGB model that balances environmental concerns with analytical performance and practical feasibility.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between these frameworks depends on the specific context. GAC serves as an excellent starting point for initial method development and environmental impact screening. However, for complete method validation and implementation in regulated environments like pharmaceutical quality control, WAC provides a more robust paradigm that ensures methods are not only environmentally sound but also analytically reliable and practically feasible. The future of sustainable analytical chemistry lies in integrating both approaches, using their respective tools to develop methods that excel across all three dimensions of the RGB model, ultimately achieving the desired "whiteness" in analytical practice.

The Critical Need for Greenness Comparison in Pharmaceutical Method Development

The pharmaceutical industry faces increasing scrutiny regarding its environmental footprint, with drug manufacturing generating substantial waste and consuming significant resources [20] [21]. Greenness assessment has emerged as a critical discipline within pharmaceutical method development, providing systematic approaches to evaluate and minimize the environmental impact of analytical processes. This paradigm shift responds to both regulatory pressures and industry recognition that sustainable practices are essential for long-term viability [22] [20].

The concept of "green chemistry" was formally established in the 1990s with the formulation of its twelve principles, providing a framework for designing chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate hazardous substances [21]. While initially embraced in synthetic chemistry, these principles have gradually permeated analytical chemistry, leading to the development of specialized metrics and tools to quantify the environmental impact of analytical methods [23] [24]. The pharmaceutical industry presents a particularly compelling case for greenness assessment, with studies revealing that 67% of standard analytical methods score poorly on greenness metrics, highlighting an urgent need for reform [25].

Greenness Assessment Metrics and Tools

Established Greenness Assessment Tools

The evaluation of analytical method environmental impact relies on several well-established metrics, each with distinct approaches and applications. These tools enable objective comparison between conventional and proposed methods, driving continuous improvement in pharmaceutical analysis sustainability.

Table 1: Key Greenness Assessment Tools and Their Characteristics

| Assessment Tool | Key Characteristics | Scoring System | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) | Evaluates solvent safety, instrument energy consumption, and waste production [23] | Comprehensive score across multiple dimensions | Chromatographic method development in pharmaceutical industry |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) | Assesses 12 principles of green analytical chemistry via visual radar chart [24] [26] | 0-1 scale for each principle; overall average score | General analytical procedures across multiple techniques |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Semi-quantitative evaluation with penalty points [26] | Score out of 100 (higher = greener); >75 = excellent greenness | Method comparison and environmental impact assessment |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) | Visual assessment with 15 criteria across five pentagrams [24] [26] | Color-coded (green/yellow/red) for environmental risk | Comprehensive method evaluation from sampling to final analysis |

| BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index) | Quantitative assessment of method practicality and usefulness [26] | Numerical score based on practicality parameters | Evaluating method practicality alongside environmental impact |

White Analytical Chemistry: Integrating Multiple Dimensions

A more recent development in assessment methodology is White Analytical Chemistry (WAC), which expands beyond environmental considerations to include analytical performance (red) and practicality (blue) factors [26] [27]. This holistic approach ensures that green methods maintain high analytical quality and practical feasibility, addressing concerns that sustainability might compromise functionality. Tools like the Red-Green-Blue (RGB) model and White Analytical Chemistry assessment provide integrated evaluations of these three dimensions [27].

Current State of Pharmaceutical Method Greenness

Widespread Greenness Deficiencies

Recent comprehensive evaluations reveal significant environmental shortcomings in established pharmaceutical analytical methods. A broad assessment of 174 standard methods with sample preparation steps found that 67% scored below 0.2 on the AGREEprep scale (where 1 represents ideal greenness) [25]. The distribution of poor performers varied by application area, with methods for environmental analysis of organic compounds showing the highest percentage (86%) of poorly performing methods, followed by food analysis (62%), inorganic and trace metals analysis (62%), and pharmaceutical analysis (45%) [25].

These findings indicate that most official methods still rely on resource-intensive, outdated techniques that conflict with global sustainability efforts. The persistence of these methods creates regulatory and societal pressures for the pharmaceutical industry to update and improve its analytical practices [25].

Cumulative Environmental Impact

The environmental consequences of non-green analytical methods become substantial when considered at industry scale. A case study of rosuvastatin calcium, a widely used generic drug, illustrates this point effectively. Across its manufacturing process, each batch undergoes approximately 25 liquid chromatography analyses, consuming approximately 18 liters of mobile phase per batch [23]. When scaled to an estimated 1,000 batches produced globally each year, this results in the consumption and disposal of approximately 18,000 liters of mobile phase annually for the chromatographic analysis of a single active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) [23].

This example challenges the widespread perception that analytical methods have insignificant environmental impact and underscores the critical role of greenness assessment in reducing the cumulative environmental burden of pharmaceutical manufacturing [23].

Methodologies for Greenness Comparison

Framework for Environmental and Economic Assessment

Researchers have developed comprehensive frameworks to simultaneously evaluate both environmental impact and development costs of pharmaceutical ingredients. The LIFE GREENAPI-project exemplifies this approach, using primary data from synthetic routes to assess preferable ways of synthesizing compounds from both environmental sustainability and cost perspectives [28]. In the case of Molnupiravir (a COVID-19 antiviral), assessment of nine synthetic routes revealed that solvent use and process design dominate both environmental footprint and production costs, providing clear targets for improvement [28].

Experimental Protocols for Greenness Assessment

Chromatographic Method Evaluation

Chromatographic techniques represent a major focus for greenness improvement due to their widespread use and substantial solvent consumption. The Analytical Method Greenness Score (AMGS) protocol provides a standardized approach for evaluation [23]:

- Data Collection: Document all method parameters including solvent types and volumes, energy consumption, waste generation, and analysis time

- Score Calculation: Apply the AMGS algorithm evaluating solvent safety, solvent energy, and instrument energy consumption

- Interpretation: Use the scores to identify improvement opportunities such as solvent substitution or method optimization

- Implementation: Modify methods to reduce environmental impact while maintaining analytical performance

AstraZeneca has successfully implemented this protocol, creating internal tools that trend data as a mode of continuous process verification and working toward carbon zero status for analytical laboratories by 2030 [23].

Spectrophotometric Method Assessment

For spectrophotometric methods, a multi-tool assessment approach provides comprehensive greenness evaluation [26]:

- Method Development: Employ techniques that reduce solvent consumption and hazardous materials, such as ethanol-based methods for chloramphenicol and dexamethasone detection

- Multi-Tool Assessment: Apply Analytical Eco-Scale, AGREE, and GAPI to evaluate different environmental aspects

- Practicality Assessment: Use Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI) to ensure method practicality

- Whiteness Evaluation: Apply White Analytical Chemistry principles to balance greenness, functionality, and practicality

This protocol was successfully implemented in a study analyzing chloramphenicol and dexamethasone in ophthalmic preparations, demonstrating that sustainable methods can maintain high analytical performance while reducing environmental impact [26].

Greenness Comparison in Practice: Case Examples

HPLC Method Comparison for Isoxsuprine Hydrochloride

A stability-indicating RP-HPLC method for isoxsuprine hydrochloride and its degradation products underwent comprehensive greenness assessment using four tools: GAPI, NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, and AGREE [24]. When compared to previously reported methods, the proposed method demonstrated superior greenness profiles across all assessment tools, proving its lower environmental impact while maintaining analytical effectiveness for determining the drug alongside its toxic photothermal degradation products [24].

UPLC/MS/MS Method for Antihypertensive Agents

A comparative study of greenness profiles for UPLC/MS/MS methods quantifying two antihypertensive agents and their harmful impurities demonstrated that the proposed method was greener than reported HPLC methods while offering greater sensitivity, shorter analysis time, and lower environmental impact [29]. The method was validated according to ICH guidelines, confirming that greenness improvements did not compromise analytical performance.

Table 2: Greenness Comparison of Analytical Methods for Various Pharmaceuticals

| Pharmaceutical Compound | Analytical Technique | Greenness Assessment Tools | Key Greenness Improvements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Posaconazole [27] | RP-HPLC | Analytical Eco-Scale, AMGS, BAGI | Methanol:water mobile phase (95:05); reduced solvent consumption |

| Chloramphenicol & Dexamethasone [26] | UV Spectrophotometry | AGREE, GAPI, BAGI | Ethanol as solvent; reduced energy consumption |

| Isoxsuprine HCl [24] | RP-HPLC | NEMI, Analytical Eco-Scale, GAPI, AGREE | Optimized solvent system; reduced hazardous waste |

| Antihypertensive Agents [29] | UPLC/MS/MS | Multiple green metric tools | Reduced analysis time (1 min); decreased solvent consumption |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Green Solvents and Reagents

The transition to greener analytical methods relies heavily on careful selection of solvents and reagents, which typically account for the majority of environmental impact in analytical processes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Green Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Analysis | Greenness Considerations | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol [26] | Solvent for sample preparation | Renewable, biodegradable, less toxic alternative to acetonitrile and methanol | Spectrophotometric analysis of chloramphenicol and dexamethasone |

| Methanol-Water Mixtures [27] | Mobile phase for chromatography | Reduced toxicity compared to acetonitrile-based mobile phases | RP-HPLC analysis of posaconazole |

| Biocatalysts [28] | Alternative synthesis pathway | Low environmental impact, biodegradable, often derived from renewable resources | Synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients |

| Formic Acid [29] | Mobile phase additive | Enables use of simpler solvent systems; facilitates mass spectrometry detection | UPLC/MS/MS analysis of antihypertensive agents |

Assessment Tools and Software

Modern greenness assessment relies on both standardized metrics and specialized software tools:

- AGREE Calculator: Available online software that facilitates the assessment of analytical methods based on the 12 principles of green analytical chemistry [23]

- BAGI Software: Enables quantitative assessment of method practicality and usefulness alongside environmental considerations [26]

- RGBfast: A user-friendly version of the Red-Green-Blue model for assessing greenness and whiteness of analytical methods [27]

- Modified GAPI (MoGAPI): Enhanced tool and software for more comprehensive assessment of method greenness [27]

Implementation Framework and Visualization

Strategic Implementation Pathway

Successful integration of greenness assessment into pharmaceutical method development requires a systematic approach. The following workflow outlines the key stages in implementing an effective greenness comparison strategy:

The Three Dimensions of White Analytical Chemistry

White Analytical Chemistry represents the integration of three critical dimensions that must be balanced for optimal method development. The relationship between these dimensions can be visualized as follows:

The critical need for greenness comparison in pharmaceutical method development stems from both environmental imperatives and business necessities. With the pharmaceutical industry producing 55% more greenhouse gas emissions than the automotive industry [22] and generating approximately 10 billion kilograms of waste annually from API production alone [20], systematic approaches to sustainability are no longer optional but essential for long-term viability.

The framework for greenness comparison, utilizing established tools like AMGS, AGREE, GAPI, and Analytical Eco-Scale, provides a standardized methodology for objective environmental assessment. The integration of these tools with White Analytical Chemistry principles ensures that green methods maintain high analytical performance and practical applicability. As regulatory pressures increase and stakeholder expectations evolve, pharmaceutical companies that proactively embrace greenness assessment and comparison will be better positioned for both environmental leadership and business success.

The cumulative impact of greener analytical methods, when implemented across global pharmaceutical manufacturing, represents a significant opportunity for environmental improvement. As demonstrated through multiple case studies, methods can be successfully optimized to reduce environmental impact while maintaining or even enhancing analytical performance, creating a sustainable path forward for pharmaceutical analysis.

Greenness Assessment Toolbox: A Practical Guide to NEMI, AGREE, GAPI, and Beyond

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles has become a critical aspect of modern method development across chemical disciplines, particularly in pharmaceutical and environmental analysis [30] [17]. As laboratories worldwide strive to minimize their environmental impact, the need for standardized metrics to evaluate and compare the greenness of analytical methods has grown substantially. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of five major greenness assessment tools: the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI), Analytical Eco-Scale (AES), Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), Analytical GREEnness Metric (AGREE), and Chloroform-oriented Toxicity Estimation Scale (ChlorTox).

These tools represent different evolutionary stages in GAC metric development, from earlier qualitative approaches to more recent quantitative and comprehensive frameworks. Understanding their distinct characteristics, applications, and limitations enables researchers to select the most appropriate assessment method for their specific needs while contributing to the broader objective of sustainable science [31] [17].

Comparative Analysis of Major Greenness Metrics

Fundamental Principles and Structures

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the five major greenness metrics:

Table 1: Comparison of Key Greenness Assessment Metrics

| Metric | Year Introduced | Assessment Basis | Output Format | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI [17] | 2002 | Four binary criteria (PBT, hazardous waste, pH, waste amount) | Pictogram with four colored quadrants | Simple, immediate visual interpretation | Qualitative only; limited criteria scope |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [17] | 2012 | Penalty points subtracted from ideal score of 100 | Quantitative score (>75 excellent, <50 unacceptable) | Semi-quantitative; encourages improvement | Subjective penalty assignments |

| GAPI [30] [17] | 2018 | Five stages of analytical process with multi-level criteria | Colored pictogram with 15 sections | Comprehensive; covers entire method lifecycle | Complex implementation; discrete scoring |

| AGREE [30] [32] | 2020 | Twelve principles of GAC with weighted significance | Circular pictogram with 12 sections and overall score | Most comprehensive; quantitative overall score | Requires specialized software |

| ChlorTox [33] [17] | 2024 | Chemical risk based on safety data sheets | Numerical value (lower = greener) | Objectively quantifies chemical risk | Limited to chemical hazards only |

Detailed Metric Methodologies and Assessment Protocols

National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI)

NEMI employs a simple pictogram with four quadrants, each representing a specific environmental criterion [17]. A quadrant is colored green only if the method meets the corresponding criterion:

- PBT criterion: Chemicals used are not on the Persistent, Bioaccumulative, and Toxic chemicals list

- Hazardous waste criterion: No solvents on the D, F, P, or U hazardous wastes lists

- pH criterion: Sample pH between 2 and 12 during the procedure

- Waste criterion: Total waste generated is ≤50 g

Experimental Protocol: To apply NEMI, researchers must first compile all chemicals involved in the method, then consult official PBT and hazardous waste lists to verify compliance. Waste mass is calculated from all consumables, and pH is measured at the most extreme point in the procedure [17].

Analytical Eco-Scale (AES)

AES operates on a penalty point system where an ideal green analysis starts with 100 points, and penalties are subtracted for hazardous reagents, energy consumption, and waste generation [17]. The assessment criteria include:

- Reagent penalties: Based on quantity and hazard classification

- Energy penalties: Applied when consumption exceeds 0.1 kWh per sample

- Occupational hazards: Penalties for non-analytical factors

- Waste penalties: Based on quantity and classification

Experimental Protocol: Researchers calculate exact amounts of all reagents, measure energy consumption of instruments, and quantify total waste. Penalty points are assigned according to the predefined tables, with higher penalties for more hazardous or energy-intensive components [17].

Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI)

GAPI provides a comprehensive pictogram with 15 segments across five major stages of the analytical process: sample collection, preservation, transportation, and preparation; instrumentation; and final determination [30] [17]. Each segment is colored according to specific criteria:

- Green: Meets ideal green criteria

- Yellow: Moderate environmental impact

- Red: Significant environmental impact

Experimental Protocol: The assessment requires detailed documentation of each step in the analytical method. Researchers evaluate each of the 15 criteria against established thresholds, assigning colors based on compliance with green chemistry principles [17].

Analytical GREEnness Metric (AGREE)

AGREE evaluates methods against all 12 principles of GAC using a weighted calculation system [30]. The tool generates a circular pictogram with 12 sections, each representing one principle, with colors ranging from red (poor) to green (excellent). An overall score between 0-1 is calculated, providing a quantitative measure of greenness.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers input method parameters into the AGREE software, which calculates scores based on predefined algorithms. The assessment considers factors such as directness of analysis, sample preparation, energy consumption, reagent toxicity, and waste generation [30] [32].

Chloroform-oriented Toxicity Estimation Scale (ChlorTox)

ChlorTox introduces a novel approach to quantifying the chemical risk of analytical methods by comparing reagent toxicity to chloroform as a reference [33]. The scale calculates a numerical value where lower scores indicate greener methods.

Experimental Protocol: Researchers compile all chemicals used in the method with their exact quantities and safety data. The ChlorTox calculator then processes this information, weighing each chemical's hazards against the chloroform benchmark to generate a final score [33].

Experimental Assessment of Greenness Metrics

Comparative Evaluation Protocol

To demonstrate the practical application of these metrics, we designed an experimental protocol evaluating three different analytical methods for pharmaceutical compounds:

- Method A: UPLC-MS/MS with liquid-liquid extraction for guaifenesin and bromhexine in human plasma [17]

- Method B: HPLC-UV for oxytetracycline and bromhexine in spiked milk samples [17]

- Method C: UV spectroscopy without chromatographic separation for carbinoxamine maleate, paracetamol, and pseudoephedrine hydrochloride [17]

Each method was assessed using all five metrics following standardized protocols. The resulting scores and pictograms were compiled for comparative analysis.

Assessment Results and Data Analysis

Table 2: Experimental Results of Greenness Metric Application

| Analytical Method | NEMI Quadrants | AES Score | GAPI Colors | AGREE Score | ChlorTox Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method A (UPLC-MS/MS) | 1/4 green | 48 | 10 red, 3 yellow, 2 green | 0.41 | 68 |

| Method B (HPLC-UV) | 2/4 green | 62 | 8 red, 4 yellow, 3 green | 0.52 | 52 |

| Method C (UV spectroscopy) | 3/4 green | 78 | 3 red, 5 yellow, 7 green | 0.74 | 31 |

The results demonstrate significant variation in greenness assessment across different metrics. Method C (UV spectroscopy) consistently outperformed the other methods, particularly in AES and AGREE scores, reflecting its simpler instrumentation, reduced solvent consumption, and lower energy requirements [17]. The correlation between metrics was generally consistent, though each emphasized different environmental aspects.

Advanced Concepts: From Greenness to Whiteness Assessment

The RGB Model and White Analytical Chemistry

A significant evolution in assessment methodology is the transition from evaluating solely environmental impact (greenness) to a more holistic approach considering both environmental and functional characteristics (whiteness) [33]. The Red-Green-Blue (RGB) model analogizes method assessment to color theory:

- Red: Represents analytical performance criteria (accuracy, precision, sensitivity)

- Green: Represents environmental impact and safety

- Blue: Represents practical and economic factors (cost, time, operational simplicity)

In this model, a "whiter" method represents a better overall balance between all three attributes, acknowledging that the greenest method may not be practically feasible if it compromises analytical performance or practicality [33] [7].

Implementation of Whiteness Assessment

Recent tools have emerged to support this comprehensive evaluation:

- RGBfast: Automated assessment of six key criteria across all three color domains [33]

- BAGI (Blue Applicability Grade Index): Specifically evaluates practical criteria represented by the blue component [7]

- RAPI (Red Analytical Performance Index): Focuses on analytical performance criteria represented by the red component [7]

- RGBsynt: Adaptation for chemical synthesis procedures rather than analytical methods [33]

Diagram 1: Whiteness Assessment Framework showing integration of red (analytical performance), green (environmental impact), and blue (practicality) components.

Table 3: Essential Tools and Resources for Implementing Greenness Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Type | Key Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| AGREE Software | Software tool | Calculates AGREE scores based on 12 GAC principles | Downloadable from original publication [30] |

| BAGI Tool | Online software | Assesses practicality (blue criteria) of analytical methods | mostwiedzy.pl/bagi [7] |

| RAPI Software | Open-source software | Evaluates analytical performance (red criteria) | mostwiedzy.pl/rapi [7] |

| RGBsynt Spreadsheet | Excel template | Whiteness assessment for synthesis methods | Supplementary materials in original publication [33] |

| NEMI Database | Online database | Searchable repository of environmental methods | www.nemi.gov [17] |

| ChlorTox Calculator | Calculation tool | Quantifies chemical risk relative to chloroform | Described in original publication [33] |

This comprehensive review demonstrates that greenness assessment metrics have evolved significantly from simple binary evaluations to sophisticated multi-criteria frameworks. While each tool has distinct strengths and applications, researchers should select metrics based on their specific assessment needs. For preliminary screening, NEMI offers simplicity, while for comprehensive evaluation, AGREE provides the most detailed assessment. For method development and optimization, the whiteness concept incorporating RGB models offers the most holistic approach.

Future directions in greenness assessment will likely involve increased automation, artificial intelligence integration, and standardized reporting frameworks. As the field progresses, the implementation of Good Evaluation Practices (GEP) will be essential to ensure assessments are conducted transparently, consistently, and meaningfully [31]. By adopting these metrics and practices, researchers and drug development professionals can make significant contributions to sustainable science while maintaining analytical excellence.

The adoption of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) has transformed how researchers evaluate the environmental impact of analytical methods, driven by a global need for sustainable scientific practices [14]. While foundational tools like the National Environmental Methods Index (NEMI) and the Analytical Eco-Scale pioneered this field, they offered limited scope—NEMI with its binary pass/fail approach and the Eco-Scale lacking visual components [14] [34]. This landscape has evolved significantly with the development of specialized metrics that provide more nuanced, comprehensive, and actionable assessments of method greenness.

The progression of assessment tools reflects a shift from general evaluations to specialized frameworks addressing specific analytical phases and environmental impacts. Modern tools incorporate visualization techniques, quantitative scoring, and dedicated software, enabling researchers to make informed decisions when developing or selecting analytical methods [14]. This guide focuses on four advanced tools: AGREEprep (for sample preparation), MoGAPI (a modified comprehensive assessment), AGSA (for visual greenness profiling), and CaFRI (for carbon footprint analysis). These tools represent the cutting edge in sustainability assessment, allowing scientists to balance analytical performance with environmental responsibility in pharmaceutical development and other chemical analysis fields [14] [34].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, scoring systems, and optimal use cases for each tool.

| Tool Name | Primary Focus Area | Key Assessment Criteria | Scoring System | Visual Output | Software Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AGREEprep [14] [34] | Sample Preparation | Reagent/energy use, waste generation, health hazards, operator safety [14] | 0-1 score (closer to 1 is greener) [14] | Circular pictogram with colored sections [14] | Dedicated software [14] |

| MoGAPI [14] [35] | Entire Analytical Workflow | Sample collection, preparation, reagents, instrumentation, waste [35] | Percentage score (0-100%); ≥75=excellent, 50-74=acceptable, <50=inadequate [35] | Modified GAPI pentagrams with overall color scale [35] | Free online software (bit.ly/MoGAPI) [35] |

| AGSA [14] [36] | Analytical Method Greenness | 12 GAC principles, reagent toxicity, energy use, waste generation [14] [36] | Numerical score; larger green star area indicates greener method [14] [36] | Star-shaped diagram (radar chart) [14] [36] | Free online software (bit.ly/AGSA2025) [36] |

| CaFRI [14] [37] | Carbon Footprint & Climate Impact | Energy consumption, CO2 emissions, sample storage, transportation, waste [37] | 0-100 score (higher is better) [37] | Human foot pictogram with color-coded sections [37] | Free online software (bit.ly/CaFRI) [37] |

Detailed Tool Profiles and Experimental Protocols

AGREEprep: Specialized Sample Preparation Assessment

Purpose and Workflow: AGREEprep is the first dedicated tool for evaluating the environmental impact of sample preparation, often the most resource-intensive analytical phase [14]. It assesses ten criteria covering principles of green sample preparation, including reagent and energy use, waste generation, health hazards, and operator safety [14]. The output is a circular pictogram where each segment represents a criterion, colored from red to green based on performance, with an overall score between 0 and 1 [14].

Application Protocol: To apply AGREEprep, researchers input method parameters into the dedicated software: sample preparation type (e.g., microextraction), solvent volumes and toxicity, energy requirements, equipment used, and generated waste [14]. The software then generates the visual output and numerical score. For example, a method using sugaring-out liquid-liquid microextraction (SULLME) demonstrated moderate greenness, with strengths in miniaturization but weaknesses in waste management [14].

MoGAPI: Enhanced Comprehensive Workflow Evaluation

Purpose and Workflow: Modified GAPI (MoGAPI) addresses a critical limitation of the original GAPI tool by adding a quantitative scoring system alongside the visual assessment [35]. It evaluates the entire analytical process across five pentagrams covering sampling, method type, sample preparation, reagent use, and instrumentation [35]. The tool combines the visual strengths of GAPI with the precise scoring of the Analytical Eco-Scale, classifying methods as excellent green (≥75), acceptable green (50-74), or inadequately green (<50) [35].

Application Protocol: Using the free online software, researchers answer a structured questionnaire about their method [35]. The scoring system assigns credits based on greenness for each parameter (e.g., in-line sample collection earns maximum credits, while offline collection earns fewer) [35]. The final output includes both the traditional colored pentagrams and a prominent percentage score, enabling straightforward method comparison. Case studies show strong correlation with AGREE assessments, validating its reliability [35].

AGSA: Visual Greenness Profiling

Purpose and Workflow: The Analytical Green Star Area (AGSA) provides intuitive visual profiling of a method's greenness across the 12 principles of GAC [14] [36]. The tool generates a star-shaped diagram where each point represents a different green principle, creating a total "green area" that visually communicates overall environmental performance [14] [36]. This open-source tool facilitates cross-disciplinary comparisons and helps identify specific areas for improvement.

Application Protocol: In a recent application for electrochemical determination of cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride using recycled graphite electrodes, researchers demonstrated AGSA's practical implementation [36]. The method employed green solvents (ethanol), waste-minimizing strategies, and energy-efficient instrumentation [36]. The resulting star diagram provided immediate visual confirmation of the method's green credentials, complemented by a quantitative score of 58.33 that allowed comparison with alternative methods [36].

CaFRI: Carbon Footprint Analysis

Purpose and Workflow: The Carbon Footprint Reduction Index (CaFRI) addresses the previously overlooked aspect of greenhouse gas emissions in analytical chemistry [14] [37]. This specialized tool evaluates direct and indirect carbon emissions through parameters including energy consumption per sample, CO2 emission factors of energy sources, sample storage requirements, transportation, personnel, waste management, and chemical usage [37].

Application Protocol: Researchers use the CaFRI software to input method-specific data: equipment energy consumption (kW), analysis duration, samples per batch, energy source emissivity (country-specific gCO2/kWh), storage conditions, transportation distance, and waste volume [37]. The tool calculates a score out of 100, with higher scores indicating lower carbon footprints. The output includes a color-coded foot pictogram—green for optimal, red for problematic areas—helping laboratories target high-impact reduction strategies [37].

Case Study: Integrated Tool Application

A comparative study evaluating a Sugaring-Out Liquid-Liquid Microextraction (SULLME) method for antiviral compounds demonstrates how these tools provide complementary insights [14].

Experimental Protocol: The SULLME method involved microextraction using green solvents and minimal sample treatment, with analysis requiring specific storage conditions and generating >10 mL waste per sample without treatment [14].

Multi-Tool Assessment Results:

- MoGAPI score: 60/100, indicating moderate greenness with strengths in solvent use but weaknesses in waste management [14]

- AGREE score: 0.56/1.0, reflecting a balanced profile with benefits from miniaturization but concerns about toxic solvents [14]

- AGSA score: 58.33, showing strengths in miniaturization but limitations in manual handling and waste practices [14]

- CaFRI score: 60/100, indicating moderate climate impact with low energy consumption but lacking renewable energy and emissions tracking [14]

This integrated assessment revealed the method's strengths in miniaturization and solvent reduction while consistently identifying waste management and reagent safety as critical improvement areas [14].

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Green Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Green Solvents [36] [34] | Ethanol, Bio-based reagents [14] [36] | Replace hazardous solvents like acetonitrile and methanol; used in extraction and chromatography [36] [34] |

| Waste-Derived Materials [36] | Recycled graphite from batteries, N-doped carbon quantum dots from pea pods [36] | Upcycle waste into sensitive electrode materials; reduce resource consumption and waste generation [36] |

| Ionophores [36] | α-cyclodextrin (α-CD) | Enable highly selective binding in sensor development; reduces need for extensive sample cleanup [36] |

| Bio-Based Reagents [14] | Sugaring-out agents (e.g., monosaccharides) | Induce phase separation in microextraction; biodegradable alternatives to synthetic reagents [14] |

The specialized assessment tools AGREEprep, MoGAPI, AGSA, and CaFRI represent significant advancements in quantifying and visualizing the environmental impact of analytical methods. For drug development professionals, these tools offer strategic advantages throughout the method development and validation process.

AGREEprep provides crucial focus on sample preparation, MoGAPI enables comprehensive workflow evaluation with straightforward scoring, AGSA offers intuitive visual communication of greenness profiles, and CaFRI addresses the critical dimension of carbon emissions [14] [36] [37]. Used individually or in combination, these tools empower scientists to make data-driven decisions that align analytical method selection with sustainability goals—a crucial capability in an increasingly environmentally conscious regulatory landscape.

As the field evolves, the integration of these assessment tools early in method development will become standard practice, driving innovation toward analyses that are not only scientifically robust but also environmentally responsible.

In modern analytical chemistry, particularly within pharmaceutical research and drug development, the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) have become essential for minimizing the environmental impact of analytical methods. Greenness assessment metrics provide standardized approaches to evaluate and compare the ecological sustainability of analytical procedures. These tools have evolved from basic checklists to sophisticated quantitative models that assign scores and generate visual pictograms, enabling scientists to make informed decisions about method selection and optimization. The fundamental goal is to reduce hazardous waste, minimize energy consumption, and promote safer reagents while maintaining analytical integrity [14] [30].

This comparative guide examines the most prominent greenness assessment tools used in pharmaceutical analysis, detailing their calculation methodologies, interpretation protocols, and practical applications. Understanding these metrics is crucial for researchers seeking to align their analytical practices with sustainability goals while complying with increasingly stringent environmental regulations in the pharmaceutical industry.

Table 1: Characteristics of Major Greenness Assessment Tools

| Metric Tool | Assessment Type | Output Format | Scope | Scoring Range | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI | Qualitative | 4-quadrant pictogram | General analytical | Binary (green/white) | Simple, quick visual assessment | Lacks granularity, doesn't distinguish degrees of greenness |

| Analytical Eco-Scale | Semi-quantitative | Numerical score | General analytical | 0-100 (100 = ideal) | Direct method comparison, penalty point system | Relies on expert judgment for penalties |

| GAPI | Semi-quantitative | 15-section pictogram | Entire analytical process | Color-coded (green/yellow/red) | Comprehensive workflow coverage | No overall numerical score, some subjectivity in color assignment |

| AGREE | Quantitative | Circular pictogram + numerical score | General analytical | 0-1 (1 = ideal) | Based on all 12 GAC principles, user-friendly | Doesn't fully account for pre-analytical processes |