GUM vs. Monte Carlo Simulation: A Strategic Guide to Uncertainty Analysis in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) and the Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) for quantifying measurement uncertainty, with a specific...

GUM vs. Monte Carlo Simulation: A Strategic Guide to Uncertainty Analysis in Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) and the Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) for quantifying measurement uncertainty, with a specific focus on applications in biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences. It covers the foundational principles of both methods, explores their practical application through case studies from clinical measurement and analytical chemistry, and offers troubleshooting guidance for common challenges like nonlinear models and asymmetric distributions. A detailed validation and comparative analysis section equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select the most appropriate method, enhance the reliability of their data, and meet rigorous regulatory standards for decision-making.

Understanding Measurement Uncertainty: The Roles of GUM and Monte Carlo

Defining Measurement Uncertainty and Its Critical Importance in Biomedical Data Integrity

In biomedical research and drug development, quantitative measurements form the bedrock of scientific discovery and clinical decision-making. Measurement uncertainty is a fundamental metrological concept that provides a quantitative estimate of the quality of a test result, characterizing the dispersion of values that could reasonably be attributed to the measurand [1]. According to ISO standards, no measurement is complete without an accompanying statement of its associated uncertainty [2], as this parameter enables researchers to determine if a result is adequate for its intended purpose and consistent with other similar results [1].

The International Standard ISO 15189:2004 defines measurement uncertainty as "a parameter associated with the result of a measurement, that characterises the dispersion of the values that could be reasonably attributed to the measurand" [1]. In laboratory medicine, this concept, while traditionally familiar in the form of standard deviation and imprecision metrics, has evolved into a more comprehensive framework essential for verifying that analytical methods meet defined goals, indicating the confidence in test results, and identifying areas for procedural improvement [1].

Methodological Frameworks for Uncertainty Analysis

GUM: The Established Standard

The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) represents the internationally recognized approach for uncertainty evaluation, developed through collaboration between various international metrological and standards organizations [1]. This framework provides laboratories with a structured methodology based on mathematical theory and experimental observation to estimate standard uncertainties for all relevant components of a test procedure [1].

The GUM approach classifies uncertainty components into two categories: Type A components (evaluated by statistical analysis of measurement series) and Type B components (evaluated by other means, such as manufacturer specifications or scientific literature) [3]. These components are combined into a standard combined uncertainty, which can be multiplied by a coverage factor (typically k=2 for 95% confidence) to produce an expanded uncertainty [3]. This "bottom-up" model requires identifying and quantifying all significant sources of uncertainty in the measurement process [3].

Monte Carlo Simulation: The Computational Approach

Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) has emerged as a powerful alternative and supplement to traditional GUM methods, particularly for complex, non-linear systems [4]. This computational technique uses repeated random sampling to numerically approximate the distribution of output quantities, making it especially valuable when the relationship between input and output variables is not linear or when output distributions are asymmetric [4].

As a supplement to GUM, MCS is recommended for validating GUM results and for cases where the GUM approach's assumptions of linearity and normality may not hold [4] [5]. The method involves propagating the probability distributions of input quantities through the measurement model to obtain the distribution of the output quantity, providing a more robust uncertainty estimation for complex biomedical measurement systems [4].

Comparative Analysis: GUM vs. Monte Carlo Methods

Performance Comparison in Biomedical Applications

Table 1: Methodological Comparison of GUM and Monte Carlo Simulation

| Characteristic | GUM Approach | Monte Carlo Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Law of uncertainty propagation; Taylor series approximation [5] | Repeated random sampling; statistical approximation [4] |

| Model Linearity Assumption | Requires linearization of model, potentially introducing errors for non-linear systems [5] | No linearization required; handles non-linear models effectively [4] [5] |

| Computational Demand | Relatively low computational requirements [5] | High computational demand, especially for complex models [5] |

| Output Distribution | Assumes normal or t-distribution for output [4] | No distributional assumptions; reveals true output distribution [4] |

| Implementation Complexity | Well-defined procedure but requires mathematical expertise [3] | Straightforward conceptually but requires programming/software expertise [4] |

| Accuracy for Asymmetric Distributions | May underestimate uncertainty for asymmetric distributions [4] | Accurately captures asymmetric distributions [4] |

Table 2: Application Performance in Case Studies

| Application Context | GUM Performance | Monte Carlo Performance | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Testing (ISO 8192:2007) [4] | Underestimated uncertainty at low toxicant concentrations; adequate for linear components | Accurate across all concentration ranges; revealed asymmetric distributions | Temperature tolerance, measurement interval, and oxygen probe accuracy were dominant uncertainty contributors (>90%) |

| Perspiration Measurement [5] | Calculated uncertainty: 6.81 × 10⁻⁶ kg/s | Compatible results with GUM for this application | Both methods identified airflow rate, air density, and humidity measurements as key uncertainty sources |

| Medical Laboratory Testing [3] | Practical limitations for complex biological measurements; top-down adaptations used | Not widely implemented in routine practice | Top-down models using quality control data preferred for routine medical laboratories |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Protocol for Toxicity Testing Uncertainty Analysis

The ISO 8192:2007 method for determining oxygen consumption inhibition in activated sludge provides a standardized protocol for evaluating measurement uncertainty in ecotoxicological testing [4]. The experimental procedure involves:

Sludge Preparation: Activated sludge is allowed to settle at room temperature for approximately one hour, decanted, and the supernatant replaced with chlorine-free tap water. This cleaning process is repeated four times [4].

Test Medium Preparation: Preparation of test medium containing 16 g/L peptone, 11 g/L meat extract, 3 g/L urea, 0.7 g/L NaCl, 0.4 g/L CaCl₂·2H₂O, 0.2 g/L MgSO₄·7H₂O, and 2.8 g/L KH₂PO₄ in distilled/deionized water [4].

Reference Substance Preparation: 3,5-dichlorophenol is dissolved at a concentration of 1 g/L in distilled/deionized water as a reference toxicant [4].

Test Procedure:

- A test mixture with different dilution levels (at least three concentrations plus blank control) is prepared

- Mixture is aerated (600 L/h) for 30 minutes

- Transferred to test vessel on magnetic stirrer

- Oxygen consumption measured using oxygen probe at 22 ± 2°C

- pH maintained at 7.5 ± 0.5 [4]

Calculation: Oxygen consumption rate (Rᵢ) calculated as: Rᵢ = (ρ₁ - ρ₂)/Δt × 60 (mg/L·h), where ρ₁ and ρ₂ represent oxygen concentrations at beginning and end of measurement range, and Δt is the time interval in minutes [4].

Protocol for Perspiration Measurement Uncertainty

The perspiration measurement system evaluation illustrates uncertainty analysis for biomedical instrumentation [5]:

System Configuration: Ambient air is drawn into a ventilation chamber by an air pump, with inlet air distributed uniformly to ensure proper mixing with humidity evaporated from human skin [5].

Parameter Monitoring:

- Flow rate controlled by valve and measured by flow meter

- Temperature and relative humidity of inlet and outlet air measured by sensors

- Air density calculated from temperature, pressure, and relative humidity measurements [5]

Uncertainty Components:

- Airflow rate uncertainty: resolution error (uniform distribution) and repeatability (standard deviation of 30 readings)

- Air density uncertainty: from temperature, pressure, and humidity measurements

- Absolute humidity uncertainty: calculated from temperature and relative humidity measurements [5]

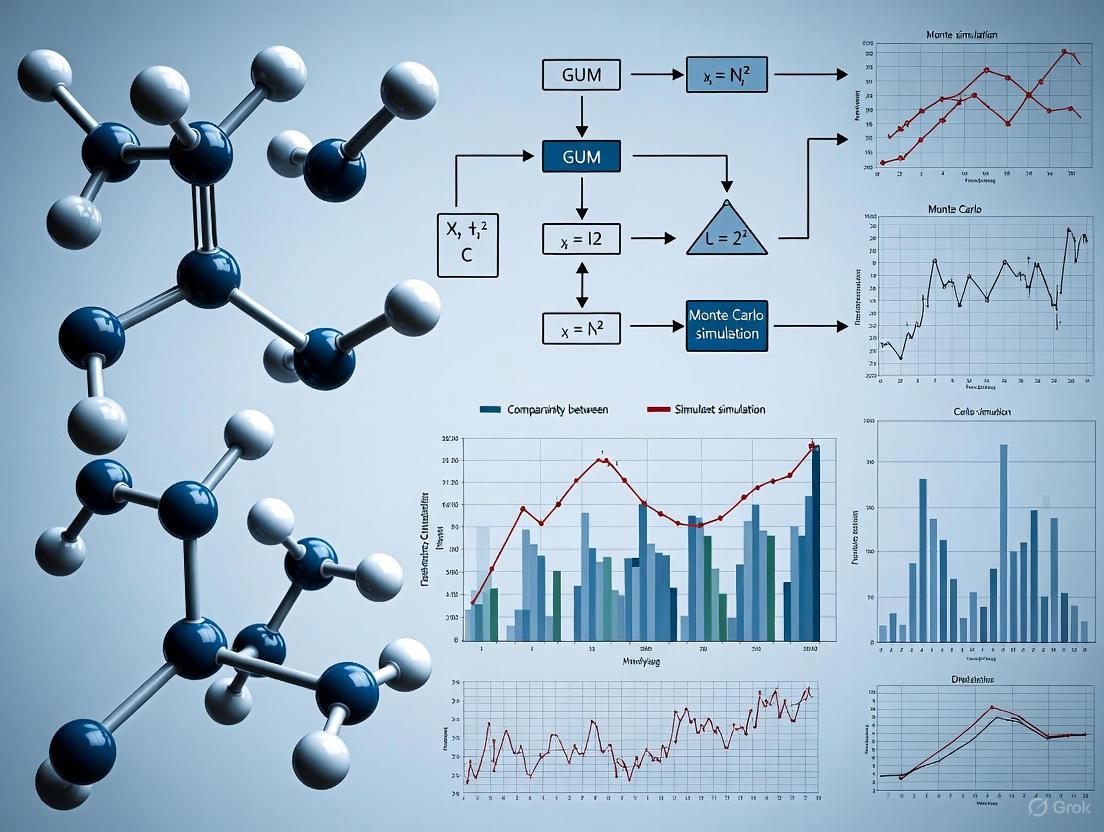

Visualization of Uncertainty Analysis Workflows

Generalized Uncertainty Analysis Framework

Uncertainty Analysis Decision Workflow

Experimental Protocol for Toxicity Testing

Toxicity Test Uncertainty Assessment

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Uncertainty Analysis

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Activated Sludge | Biological medium for toxicity testing; contains microbial communities | Ecotoxicological testing (ISO 8192:2007) [4] |

| 3,5-Dichlorophenol | Reference toxicant for method validation and calibration | Standardized toxicity testing [4] |

| Oxygen Probe | Measures dissolved oxygen concentration in biological systems | Respiration inhibition tests [4] |

| Temperature-Controlled Chambers | Maintain stable environmental conditions during testing | All biological measurements requiring temperature stability [4] [5] |

| Calibrated Flow Meters | Precisely measure and control airflow rates | Perspiration and respiration measurement systems [5] |

| Reference Materials | Provide traceability to stated references through unbroken chain of comparisons | Establishing measurement traceability [1] |

| Quality Control Materials | Monitor analytical performance and contribute to top-down uncertainty estimates | Routine medical laboratory testing [3] |

Critical Importance for Biomedical Data Integrity

In biomedical research and drug development, proper uncertainty quantification is not merely a technical requirement but a fundamental component of data integrity and reliability. The comparison of results from different laboratories, consistency assessment with reference values, and determination of suitability for clinical purpose all depend on robust uncertainty analysis [1].

Measurement uncertainty directly impacts risk assessment and decision-making processes throughout drug development. When measurement results lack proper uncertainty statements, decision risks increase significantly, potentially leading to incorrect conclusions about drug efficacy, safety profiles, or diagnostic accuracy [2]. This is particularly critical in biomedical contexts where decisions based on measurement data can affect patient diagnosis, treatment strategies, and regulatory approvals [6].

Furthermore, uncertainty analysis supports method validation and improvement by identifying dominant contributors to measurement variability. For instance, in toxicity testing, understanding that temperature tolerance, measurement interval, and oxygen probe accuracy account for over 90% of total uncertainty allows researchers to focus improvement efforts on these critical parameters [4]. This targeted approach to method optimization enhances both the quality and efficiency of biomedical research.

The choice between GUM and Monte Carlo methods should be guided by the specific characteristics of the measurement system, with GUM providing sufficient reliability for linear models with symmetric distributions, and Monte Carlo simulation offering superior performance for non-linear systems with asymmetric uncertainty distributions [4] [5]. As biomedical measurements continue to increase in complexity, the appropriate application of these uncertainty analysis methods will remain essential for maintaining data integrity across the research and development pipeline.

Foundational Principles of the GUM Framework

The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) is an internationally recognized document published by the Joint Committee for Guides in Metrology (JCGM) that establishes standardized guidelines for evaluating and expressing uncertainty in measurement results [7]. This framework provides a systematic approach for quantifying uncertainties from various sources, including equipment limitations, environmental conditions, calibration procedures, and human factors, ensuring reliable and traceable measurement results [7].

The GUM operates on several core principles that form the backbone of its methodology. First, it introduces a clear categorization of uncertainty evaluation methods into Type A and Type B. Type A evaluation involves statistical analysis of measured data, typically through repeated observations, while Type B evaluation incorporates other knowledge such as manufacturer specifications, calibration certificates, or previous measurement data [8]. Second, the framework emphasizes the propagation of uncertainties through measurement models using the law of propagation of uncertainty (LPU), which is based on a first-order Taylor series approximation [5]. Third, it provides guidelines for expressing uncertainties using confidence intervals, expanded uncertainty, and coverage factors to indicate the level of confidence associated with measurement results [7].

A fundamental assumption underlying the GUM approach is that measurement models are linear or nearly linear and that the probability distributions involved can be adequately characterized by normal distributions or t-distributions [4] [5]. This assumption enables the use of simplified mathematical approaches for uncertainty propagation but also defines the boundaries beyond which the GUM method may become unreliable.

The GUM Workflow: A Step-by-Step Process

Implementing the GUM framework follows a systematic workflow that ensures comprehensive uncertainty analysis:

- Define the Measurand: Precisely specify the parameter to be measured and its units of measurement [7].

- Identify Uncertainty Sources: Document all components of the calibration process and accompanying sources of error, which may include calibration uncertainties, environmental conditions, electrical noise, and stability of the test setup [7].

- Quantify Uncertainty Components: Evaluate each source of error through Type A (statistical) or Type B (non-statistical) methods, determining probability distributions for each source [7] [8].

- Calculate Standard Uncertainties: Convert each uncertainty component to a standard uncertainty, expressed as a standard deviation [7].

- Determine Sensitivity Coefficients: Calculate how each input quantity affects the final measurement result [9].

- Construct Uncertainty Budget: Compile all components and their standard uncertainty calculations in a structured format [7].

- Combine Uncertainties: Apply the root-sum-of-squares (RSS) method to combine all standard uncertainty components [7].

- Calculate Expanded Uncertainty: Apply an appropriate coverage factor (typically k=2 for 95% confidence) to obtain the final expanded uncertainty [7].

This structured approach facilitates transparency and repeatability in uncertainty analysis, allowing metrologists to identify dominant uncertainty contributors and prioritize improvement efforts.

Experimental Comparison: GUM Versus Monte Carlo Methods

Performance Comparison in Practical Applications

Experimental studies across various fields have provided quantitative comparisons between GUM and Monte Carlo methods. The table below summarizes key findings from published research:

Table 1: Experimental Comparison of GUM and Monte Carlo Methods

| Application Field | Measurement System | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Testing | ISO 8192:2007 oxygen consumption inhibition test | GUM results validated by MCS for oxygen consumption rates; Percentage inhibitions showed asymmetric distributions and were underestimated by GUM, especially at lower toxicant concentrations | [4] |

| Perspiration Measurement | Ventilated chamber sweat rate system | Measurement uncertainty: 6.81×10⁻⁶ kg/s (GUM) vs. 6.78×10⁻⁶ kg/s (MCS); Uncertainty percentage: 3.68% (GUM) vs. 3.66% (MCS) | [5] |

| Virtual CMM | Coordinate measurement machine simulation | For linear models with normally distributed errors: similar results; For non-linearity or biased data: propagation of distributions with bias correction provided most accurate results | [10] |

| Cadmium Measurement | Graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry | Main differences between methods attributed to calibration equation treatment | [5] |

| Electromagnetic Compatibility | EMC testing | No significant differences found between the two methods | [5] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Toxicity Testing Case Study

The comparative analysis of GUM and Monte Carlo methods in toxicity testing followed a rigorous experimental protocol based on the ISO 8192:2007 method for determining oxygen consumption inhibition in activated sludge [4]:

Materials and Equipment:

- Activated Sludge: Sourced from a municipal wastewater treatment plant

- Reference Substance: 3,5-dichlorophenol (as recommended in ISO 8192:2007)

- Test Medium: Peptone (16 g), meat extract (11 g), urea (3 g), sodium chloride (0.7 g), calcium chloride dihydrate (0.4 g), magnesium sulphate heptahydrate (0.2 g), anhydrous potassium dihydrogen phosphate (2.8 g) dissolved in 1 L distilled/deionized water

- Additional Reagents: N-allylthiourea (ATU) solution (2.5 g/L) and 3,5-dichlorophenol (1 g/L)

- Equipment: Oxygen probe (FDO 925 WTW), multi-parameter meter (Multi 3430 WTW), magnetic stirrer (Rotilabo MH 15), aeration systems

Experimental Procedure:

- Activated sludge was settled at room temperature for one hour, decanted, and supernatant replaced with chlorine-free tap water (repeated four times for cleaning)

- Test mixtures were prepared with at least three test material concentrations (1.0 mg/L, 10 mg/L, 100 mg/L) and a blank control, plus four additional dilution levels for inhibition curves

- Mixtures were aerated (300-600 L/h) for 30 minutes before transfer to test vessels on magnetic stirrers

- Oxygen consumption was measured while maintaining temperature at 22±2°C and pH at 7.5±0.5

- Oxygen consumption rates were calculated using: ( Ri = \frac{\rho1 - \rho_2}{\Delta t} \times 60 ) mg/(L·h), where ρ₁ and ρ₂ represent oxygen concentrations at beginning and end of measurement range, and Δt is the time interval in minutes

- Evaluation included linear regression of oxygen consumption curves with prior outlier identification using Cook's Distance

- Inhibition curves were generated to determine EC50 values

Uncertainty Analysis Methodology: The study evaluated up to 29 uncertainty contributions using both GUM and Monte Carlo approaches. Dominant uncertainty contributors identified included temperature tolerance, measurement interval, and oxygen probe accuracy, accounting for over 90% of total uncertainty [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Uncertainty Analysis

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Uncertainty Analysis Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Probe | Measures oxygen consumption in toxicity tests | FDO 925 with Multi 3430 meter [4] |

| Temperature Control System | Maintains stable test environment | 22±2°C maintenance capability [4] |

| Reference Substances | Provides calibrated comparison materials | 3,5-dichlorophenol for toxicity testing [4] |

| Activated Sludge | Biological medium for toxicity assessment | Sourced from wastewater treatment plants [4] |

| Data Analysis Software | Implements GUM and MCS algorithms | Capable of statistical analysis and simulation [5] |

Method Selection Guidelines and Limitations

The experimental evidence reveals clear guidelines for selecting between GUM and Monte Carlo methods based on measurement characteristics:

GUM Method is Preferred When:

- Measurement models are linear or nearly linear [10] [5]

- Error sources are normally distributed [10]

- Resources are limited, as GUM typically requires less computational time [5]

- The Welch-Satterthwaite formula can be adequately applied for effective degrees of freedom [5]

Monte Carlo Method is Superior When:

- Dealing with strong nonlinear models where Taylor series approximation becomes inaccurate [5]

- Probability distributions are asymmetric, as commonly occurs with percentage inhibition measurements [4]

- Models involve complex relationships that cannot be easily differentiated [9]

- Higher accuracy is required in uncertainty estimation, particularly with biased data analysis [10]

Key Limitations of Each Approach:

- GUM Limitations: Truncation errors from first-order Taylor series expansion in nonlinear models; potentially inaccurate assumption of normality; challenges in calculating effective degrees of freedom [5]

- Monte Carlo Limitations: Longer runtime requirements for complex cases; difficulty in selecting proper probability distribution functions; inability to visualize individual input contributions to overall uncertainty [5] [9]

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting the appropriate uncertainty evaluation method:

The GUM framework provides a robust, standardized methodology for uncertainty evaluation that performs effectively across a broad spectrum of measurement applications. Its structured workflow, emphasizing systematic identification and quantification of uncertainty sources, enables metrologists to produce comparable, defensible measurement results across different laboratories and industries [7].

Experimental evidence confirms that GUM and Monte Carlo methods yield equivalent results for linear models with normally distributed errors [10] [5]. However, in cases involving significant nonlinearities, distribution asymmetries, or complex model structures, Monte Carlo simulation provides more accurate uncertainty estimation [4] [5]. The emerging research trend focuses on hybrid approaches that leverage the computational efficiency of GUM while incorporating Monte Carlo validation for critical applications requiring higher accuracy.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting the appropriate uncertainty analysis method requires careful consideration of model linearity, distribution characteristics, computational resources, and accuracy requirements. The experimental protocols and comparison data provided in this guide offer a foundation for making informed decisions that enhance the reliability of measurement results in pharmaceutical development and other scientific fields.

The Monte Carlo method, also known as Monte Carlo simulation or Monte Carlo experiments, is a broad class of computational algorithms that rely on repeated random sampling to obtain numerical results [11]. The fundamental concept involves using randomness to solve problems that might be deterministic in principle, making it particularly valuable for modeling phenomena with significant uncertainty in inputs [11] [12]. The method derives its name from the Monte Carlo Casino in Monaco, inspired by the gambling activities of the uncle of its primary developer, mathematician Stanisław Ulam [11] [13].

Monte Carlo methods have evolved from their origins during the Manhattan Project in the 1940s, where John von Neumann and Stanislaw Ulam systematically developed them to investigate neutron travel through radiation shielding [13] [12]. The method has since become an indispensable tool across diverse fields including physics, finance, engineering, and healthcare, enabling researchers to explore complex systems that are analytically intractable or too costly to experiment with directly [11] [14] [13].

Fundamental Principles of Monte Carlo Simulation

Core Concept and Theoretical Basis

At its essence, the Monte Carlo method is a numerical technique that predicts possible outcomes of uncertain events by employing probabilistic models that incorporate elements of uncertainty or randomness [12]. Unlike deterministic forecasting methods that provide definite answers, Monte Carlo simulation generates a range of possible outcomes each time it runs, offering a more realistic representation of real-world variability [12].

The method operates on the principle of ergodicity, which describes the statistical behavior of a moving point in an enclosed system that eventually passes through every possible location [12]. This becomes the mathematical foundation for Monte Carlo simulation, where computers run sufficient simulations to produce probable outcomes from different inputs [12]. The accuracy of results is proportional to the number of simulations performed, with higher iteration counts yielding more reliable predictions [12].

The Role of Probability Distributions

Probability distributions are fundamental components that represent the range of possible values for uncertain variables [12]. These statistical functions capture the inherent randomness in input parameters and are categorized as either discrete or continuous distributions:

- Normal distribution (bell curve): Symmetrically shaped like a bell, representing most real-life events where possibilities are highest at the median and decrease toward both extremes [12].

- Uniform distribution: Represents random variables with equal probability across the valid range, appearing as a horizontal flat line when plotted [12].

- Triangular distribution: Uses minimum, maximum, and most-likely values to represent random variables, with probability peaking at the most-likely value [12].

- Exponential distribution: Describes the time between events in a Poisson process or the distance a particle travels before interaction [13].

The Monte Carlo Simulation Process

Systematic Workflow

The Monte Carlo method typically follows a structured pattern comprising several distinct phases [11] [13] [12]:

Figure 1: Monte Carlo Simulation Workflow

Detailed Phase Explanation

Define the Domain and Mathematical Model: Establish the system boundaries and develop equations describing relationships between input and output variables [12]. The mathematical model can range from basic business formulas to complex scientific equations and must accurately represent the system under investigation [12].

Generate Random Inputs from Probability Distributions: Create large datasets of random samples (typically 100,000 or more) based on appropriate probability distributions [12]. This step utilizes pseudo-random number generators (RNGs), with modern algorithms like the Mersenne Twister providing high-quality random sequences while allowing reproducibility for testing and debugging [13].

Perform Deterministic Computation: Execute the mathematical model using the generated random inputs [11]. Despite the random inputs, this computation is deterministic - the same inputs will always produce the same outputs [11] [12].

Aggregate and Analyze Results: Collect all output data and perform statistical analysis to determine key parameters such as mean values, standard deviations, and confidence intervals [11] [12]. The results are typically presented as histograms or distribution graphs that show the continuous range of possible outcomes [12].

Comparative Analysis: Monte Carlo Simulation vs. GUM Framework

The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) is an internationally recognized approach for estimating measurement uncertainties [4]. The GUM method relies on the law of uncertainty propagation and characterizes output quantities using normal or t-distributions [4]. For a response variable (y = y(x1, x2, \ldots, xn)), the combined uncertainty (uy) is calculated as:

[ uy = \sqrt{\sum{j=1}^{n}\left(\frac{\partial y}{\partial xj}u{xj}\right)^2 + 2\sum{j=1}^{n-1}\sum{i=j+1}^{n}\frac{\partial y}{\partial xi}\frac{\partial y}{\partial xj}u{xi,xj}} ]

where (u{xi,xj} = u{xi}u{xj}r{xi,xj}) and (-1 \leq r{xi,x_j} \leq 1) [15].

Key Differentiating Factors

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between GUM and Monte Carlo Methods

| Aspect | GUM Method | Monte Carlo Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Foundation | Law of uncertainty propagation & Taylor series expansion [4] [5] | Repeated random sampling & statistical analysis [11] [12] |

| Model Requirements | Differentiable models with known partial derivatives [5] [15] | Any computable model, including non-differentiable and black-box systems [11] [15] |

| Distribution Assumptions | Assumes normality or t-distributions for outputs [4] [5] | No distributional assumptions; empirically derives output distributions [12] [15] |

| Computational Approach | Analytical calculation using sensitivity coefficients [5] [16] | Numerical approximation through iterative sampling [11] [12] |

| Handling of Nonlinear Systems | Limited by first-order Taylor series approximation [5] [15] | Naturally accommodates strong nonlinearities without simplification [15] |

Performance Comparison in Experimental Studies

Multiple experimental studies have directly compared the performance of GUM and Monte Carlo methods across various application domains:

Table 2: Experimental Comparison of GUM and Monte Carlo Methods

| Application Domain | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Assessment (ISO 8192:2007) | GUM underestimated uncertainty at lower toxicant concentrations with asymmetric distributions; Monte Carlo provided accurate uncertainty quantification across all concentrations | [4] |

| Perspiration Measurement Systems | Both methods produced similar results (6.81 × 10⁻⁶ kg/s uncertainty), but Monte Carlo better captured system nonlinearities | [5] |

| Pressure Standard Effective Area | GUM required problematic simplifications for complex models; Monte Carlo enabled exact uncertainty calculations without approximations | [16] |

| Electronic Circuits (Sallen-Key Filter) | GUM produced inaccurate results for strongly nonlinear systems; Monte Carlo accurately quantified uncertainty despite nonlinearities | [15] |

| Biomedical Equipment | Monte Carlo provided more accurate results for nonlinear relationships, requiring increased trials for uncertainty stabilization | [5] |

Output Analysis and Interpretation in Monte Carlo Simulations

Statistical Aggregation Techniques

The output analysis phase transforms raw simulation data into meaningful statistical insights through several key processes:

Result Aggregation: Collecting all output values from multiple simulation runs for statistical processing [11]. For (n) simulations with results (ri), the empirical mean is calculated as (m = \frac{\sum{i=1}^{n} r_i}{n}) [11].

Distribution Fitting: Analyzing the shape and characteristics of output distributions to identify patterns, asymmetries, and outliers [12]. This often involves creating histograms or probability density plots of the results [12].

Confidence Interval Estimation: Determining ranges that contain the true value with specified probability [11]. The necessary sample size (n) for a desired accuracy (\epsilon) can be estimated using (n \geq s^2 z^2 / \epsilon^2), where (s^2) is the sample variance and (z) is the z-score corresponding to the desired confidence level [11].

Advanced Uncertainty Quantification

Figure 2: Uncertainty Quantification Process in Monte Carlo Analysis

Application in Drug Development and Healthcare

Pharmaceutical Research Implementation

Monte Carlo simulation has demonstrated particular value in drug development, where it addresses significant uncertainties in predictions of failure, cost overruns, and schedule variations [17]. The method enables dynamic modeling connecting preclinical stages through product launch, automatically reflecting time savings across dependent projects [17]. In healthcare more broadly, Monte Carlo methods have proven invaluable in treatment planning, risk assessment, and resource allocation [14].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Uncertainty Analysis

| Research Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Random Number Generators | Generate pseudo-random sequences for sampling input distributions [13] | Foundation for all Monte Carlo simulations; critical for reproducibility |

| Probability Distribution Libraries | Provide mathematical models for various uncertainty patterns (normal, uniform, triangular, exponential) [12] | Represent different types of uncertain variables in experimental systems |

| Statistical Analysis Software | Perform aggregation and analysis of simulation outputs [12] | Calculate uncertainty metrics, confidence intervals, and sensitivity measures |

| Computational Parallelization Frameworks | Distribute simulation workload across multiple processors [11] [12] | Reduce computation time for large-scale uncertainty analyses |

| Sensitivity Analysis Tools | Identify dominant uncertainty contributors in complex systems [4] | Prioritize factors for measurement improvement and uncertainty reduction |

Experimental Protocol for Pharmaceutical Uncertainty Analysis

A typical Monte Carlo implementation in drug development follows this structured protocol:

Model Establishment: Define the complete drug development pathway as a mathematical model incorporating all stages from preclinical research to commercialization [17].

Uncertainty Parameter Identification: Identify critical uncertain variables including success probabilities, development timelines, regulatory approval chances, and market dynamics [17].

Probability Distribution Assignment: Assign appropriate probability distributions to each uncertain parameter based on historical data or expert judgment [17] [12].

Simulation Execution: Run sufficient iterations (typically 10,000+) to obtain stable statistical results, utilizing parallel computing where necessary [17] [12].

Portfolio Analysis: For multi-project portfolios, model dependencies between projects where success of one initiative signals others to proceed [17].

Decision Support: Use resulting probability distributions of outcomes to support go/no-go decisions, resource allocation, and risk mitigation planning [17].

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

Benefits of Monte Carlo Simulation

- Complexity Handling: Capability to manage sophisticated models with dependencies within and across systems [17]

- Distribution Flexibility: No restrictive assumptions about input or output probability distributions [12] [15]

- Nonlinear System Compatibility: Accurate uncertainty quantification for strongly nonlinear systems where GUM fails [15]

- Comprehensive Uncertainty Capture: Ability to identify and model all viable outcomes from risks and opportunities [17]

- Visualization Capabilities: Generation of intuitive histograms and probability distributions for result communication [12]

Challenges and Computational Considerations

- Resource Intensity: Significant computational requirements, with simulations potentially taking hours or days to complete [11] [12]

- Input Sensitivity: Heavy dependence on appropriate input distributions and model structure [12]

- Implementation Complexity: Potential difficulty in selecting proper probability distribution functions for all input variables [5]

- Error Propagation: Inaccurate inputs necessarily lead to inaccurate outputs, as the method cannot compensate for fundamental model flaws [13]

The comparative analysis between GUM and Monte Carlo methods reveals distinct advantages for Monte Carlo simulation in complex, nonlinear systems prevalent in pharmaceutical research and drug development. While GUM provides an adequate analytical approach for simple, differentiable models with approximately normal output distributions, Monte Carlo simulation offers superior capability for handling real-world complexities, asymmetric distributions, and sophisticated dependency structures [4] [15].

For uncertainty analysis in drug development, where multiple interdependent factors contribute to overall project uncertainty and strategic decision-making, Monte Carlo methods provide a more robust and comprehensive framework [17]. The ability to model complete development pathways from preclinical research through commercialization, while dynamically capturing the impact of uncertainties across dependent projects, makes Monte Carlo simulation an indispensable tool for modern pharmaceutical researchers and development professionals [17].

In scientific research and drug development, quantifying the uncertainty associated with measurement results is not just good practice—it is a fundamental requirement for data integrity and regulatory compliance. The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) outlines two primary methodological frameworks for this task: the analytical Law of Propagation of Uncertainty (LPU) and the numerical Statistical Sampling approach, most commonly implemented via Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) [18] [19]. The LPU, rooted in differential calculus, provides an analytical solution, while MCS uses computational power to propagate distributions through random sampling [20]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two approaches, supported by experimental data, to help researchers select the most appropriate method for their uncertainty analysis.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

The core distinction between the two methods lies in their mathematical underpinnings and procedural execution.

Law of Propagation of Uncertainty (GUM Method)

The LPU is an analytical method based on the first-order Taylor series approximation of the measurement function [21] [18]. It is the internationally recognized approach detailed in the GUM [4].

- Mathematical Principle: For a measurand (Y = f(X1, X2, ..., XN)), the combined standard uncertainty (uc(y)) is calculated as shown in the equation below, where the partial derivatives (\partial f / \partial xi) are sensitivity coefficients, (u(xi)) are standard uncertainties of the inputs, and (u(xi, xj)) is the estimated covariance [21].

- Key Assumptions: The method assumes that the model can be satisfactorily linearized via its first-order Taylor expansion. It also generally characterizes the output quantity by a normal (Gaussian) distribution or a t-distribution [4]. The GUM procedure is based on the premise that all significant systematic errors have been identified and corrected [19].

- Complexity: The calculation of partial derivatives can become mathematically complex for highly non-linear models [20].

Statistical Sampling (Monte Carlo Simulation)

MCS is a numerical method that propagates uncertainties by simulating the measurement process a large number of times [19] [20].

- Mathematical Principle: MCS uses algorithmically generated pseudo-random numbers, forced to follow the probability density functions (PDFs) of the input quantities [19]. The model (Y = f(X1, X2, ..., X_N)) is evaluated repeatedly—often thousands or millions of times—with each evaluation using a new set of randomly sampled input values. The resulting distribution of output values directly provides the PDF of the measurand, from which its expectation, standard uncertainty, and coverage intervals can be derived empirically [19].

- Key Assumptions: MCS requires a reliable random number generator and a sufficient number of trials to ensure the output statistics converge to a stable value. It makes no linearity assumptions about the model [19].

- Implementation: For many medical laboratory applications, MCS can be implemented using readily available spreadsheets like Microsoft Excel, making it accessible without requiring advanced mathematical skills [19].

The fundamental workflows of these two methods are contrasted in the diagram below.

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

The theoretical differences translate into distinct practical strengths, weaknesses, and ideal use cases for each method. The following table summarizes the key comparative characteristics.

Table 1: Key Differences Between LPU and Monte Carlo Simulation

| Feature | Law of Propagation of Uncertainty (LPU) | Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Analytical (based on differential calculus) [21] | Numerical (based on statistical sampling) [19] [20] |

| Mathematical Basis | First-order Taylor series approximation [22] [18] | Repeated random sampling from input Probability Density Functions (PDFs) [19] |

| Model Linearity | Assumes the model can be linearized; performance degrades with strong non-linearity [4] | Handles linear and non-linear models with equal validity [19] [4] |

| Output Distribution | Typically assumes a Normal or t-distribution for the output [4] | Empirically derives the output PDF, revealing asymmetry if present [19] [4] |

| Computational Demand | Low; single calculation | High; requires thousands to millions of model evaluations [20] |

| Handling Correlation | Explicitly included via covariance terms in the propagation formula [22] [21] | Can be handled by sampling from multivariate input distributions [20] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Relatively simple, linear or mildly non-linear models with well-behaved uncertainties [20] | Complex, highly non-linear models, or models producing asymmetric output distributions [4] |

Experimental Data and Case Study Comparison

A 2025 study on toxicity assessment in wastewater treatment plants provides robust experimental data directly comparing both methods. The study quantified the measurement uncertainty of the ISO 8192:2007 method, which determines the inhibition of oxygen consumption in activated sludge, using both the GUM (LPU) and MCS approaches [4].

- Experimental Protocol: The investigation used activated sludge and 3,5-dichlorophenol as a reference substance. The core measurement was the oxygen consumption rate ((Ri)), calculated as ( Ri = \frac{\rho1 - \rho2}{\Delta t} \times 60 ) mg/L/h, where (\rho1) and (\rho2) are oxygen concentrations and (\Delta t) is the time interval [4]. The researchers evaluated up to 29 distinct uncertainty contributions, including temperature tolerance, measurement interval, and oxygen probe accuracy.

- Key Findings: The study concluded that for the calculated oxygen consumption rates, the results from the GUM method were successfully validated by MCS, confirming the LPU's reliability for this particular output [4]. However, for the final output of the analysis—the percentage inhibition—critical differences emerged. The MCS revealed that the percentage inhibitions at lower toxicant concentrations followed asymmetric distributions. The GUM method, which inherently assumes a symmetric output, underestimated the uncertainty in these cases [4].

- Interpretation: This case demonstrates that while the LPU is sufficient and computationally efficient for well-behaved, linear systems, MCS is indispensable for capturing the true uncertainty in complex, asymmetric systems often encountered in biological and pharmacological contexts.

Research Reagent Solutions for Uncertainty Analysis

The following table details key computational and statistical tools essential for implementing either uncertainty analysis approach.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Tools for Uncertainty Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Function in Uncertainty Analysis | Relevance to LPU or MCS |

|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Software (e.g., MATLAB, Mathematica) | Performs symbolic math for calculating partial derivatives required by the LPU, and provides libraries for random number generation for MCS [20]. | Both |

| Statistical Packages (e.g., R, Python with SciPy/NumPy) | Provide built-in functions for statistical analysis, probability distribution fitting, and advanced sampling algorithms crucial for MCS [19]. | Primarily MCS |

| Spreadsheet Software (e.g., Microsoft Excel) | Offers a accessible platform for implementing MCS using built-in random number functions and data analysis tools [19]. | Primarily MCS |

| Probability Distribution Libraries | Provide predefined models (Normal, Rectangular, Triangular, etc.) to correctly characterize the knowledge about each input quantity [19]. | Both |

| GUM Supplement 1 Documentation | The official guide for the propagation of distributions using a Monte Carlo method, serving as a key reference for MCS implementation [19] [4]. | Primarily MCS |

The choice between the Law of Propagation of Uncertainty and Statistical Sampling via Monte Carlo Simulation is not a matter of one being universally superior to the other. Instead, it is a strategic decision based on the complexity of the measurement model and the nature of the associated uncertainties.

The LPU is an efficient, established, and often sufficient analytical tool for linear or mildly non-linear models where the output can be reasonably assumed to follow a normal distribution. Its analytical nature makes it fast and well-suited for systems with a large number of inputs where MCS would be computationally expensive.

In contrast, MCS is a more powerful and robust numerical tool that should be employed for highly non-linear models, when input quantities have non-Gaussian distributions, or when the output distribution is suspected to be asymmetric [4]. It eliminates the need for complex linearization and provides a more empirically valid uncertainty estimate for complex systems, as evidenced by the toxicity testing case study.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this implies that the LPU remains a valuable tool for many routine analyses. However, for critical applications where model non-linearity is significant or the shape of the output distribution is unknown, MCS is the recommended and more reliable approach to ensure a complete and accurate assessment of measurement uncertainty.

Uncertainty analysis is a critical component in both laboratory accreditation and modern drug development, serving as a cornerstone for data reliability and regulatory decision-making. This guide examines the application of the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) and Monte Carlo Simulation within frameworks like ISO/IEC 17025 and Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD). By comparing these methodologies, we provide a structured analysis of their performance in quantifying measurement variability, which is essential for ensuring the validity of technical results and the safety and efficacy of pharmaceutical products.

The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) is the internationally recognized benchmark for evaluating measurement uncertainty [4] [5]. It is based on the law of uncertainty propagation and uses a first-order Taylor series approximation to combine uncertainty contributions from all input quantities affecting a measurement. The GUM method assumes that the output quantity can be characterized by a normal or t-distribution, making it most reliable for linear or mildly nonlinear models [5].

In contrast, Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) is a computational method recommended as a supplement to the GUM for more complex scenarios [4] [5]. It employs random sampling from the probability distributions of input quantities to build a numerical representation of the output quantity's distribution. This approach is particularly valuable for strongly nonlinear models or when the output distribution is expected to be asymmetric, as it does not rely on linear approximations [5].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each method.

Table: Foundational Principles of GUM and Monte Carlo Simulation

| Feature | GUM Method | Monte Carlo Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Analytical uncertainty propagation via first-order Taylor series [5]. | Numerical approximation via random sampling from input distributions [4] [5]. |

| Model Assumptions | Best for linear or mildly nonlinear models; assumes output is normal or t-distributed [5]. | No linearity assumption; handles nonlinear models and asymmetric outputs effectively [4] [5]. |

| Computational Demand | Generally low; calculated directly from a measurement equation. | Can be high, requiring a large number of trials (e.g., hundreds of thousands) for stable results [5]. |

| Primary Application Context | Standardized measurement processes where models are well-understood and relatively linear. | Complex systems, nonlinear models, and cases where the shape of the output distribution is unknown or asymmetric [4]. |

Comparative Experimental Data and Performance

A 2025 study on toxicity assessment in wastewater treatment provides a direct, quantitative comparison of GUM and Monte Carlo Simulation for the ISO 8192:2007 method, which determines the inhibition of oxygen consumption in activated sludge [4].

Experimental Protocol for Uncertainty Analysis

The experimental setup and measurement procedure were established according to ISO 8192:2007. The key components of the protocol were [4]:

- Test Organism/Medium: Nitrified activated sludge from a municipal wastewater treatment plant was used, cleaned via settling and decanting.

- Reference Substance: 3,5-Dichlorophenol was used as the reference toxicant, prepared at a concentration of 1 g/L in distilled/deionized water.

- Test Mixture Preparation: A test mixture with multiple dilution levels (at least three concentrations plus a blank control) was prepared. The medium was aerated for 30 minutes before measurement.

- Measurement Conditions: The test environment was maintained at 22 ± 2 °C with a pH of 7.5 ± 0.5. Oxygen consumption was measured in a test vessel using a calibrated oxygen probe.

- Data Analysis: Oxygen consumption rates were calculated via linear regression of the oxygen concentration curves. Inhibition curves were then generated to determine the EC50 value.

The study evaluated up to 29 different uncertainty contributions [4]. The three dominant contributors were identified as:

- Temperature tolerance

- Measurement time interval

- Oxygen probe accuracy Together, these factors accounted for over 90% of the total measurement uncertainty [4].

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Outcomes

The study validated the GUM results for oxygen consumption rates using Monte Carlo Simulation, confirming the GUM's reliability for this specific output [4]. However, a critical divergence was observed for the calculation of percentage inhibition, particularly at lower toxicant concentrations.

Table: Comparative Performance in Toxicity Testing (ISO 8192:2007)

| Analysis Output | GUM Method Results & Limitations | Monte Carlo Simulation Results & Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Consumption Rate | Results were validated by MCS, confirming reliability for this output [4]. | Excellently aligned with GUM results, confirming its suitability for this specific metric [4]. |

| Percentage Inhibition | Underestimated uncertainty, especially at lower toxicant concentrations. Struggled with asymmetric distributions [4]. | Effectively captured the asymmetric distribution of results, providing a more realistic uncertainty estimate [4]. |

| Key Finding | The GUM method's linearity assumption can lead to an underestimation of uncertainty in nonlinear, real-world biological systems [4]. | Proven as a necessary alternative for systems exhibiting asymmetry, ensuring robust and realistic decision-making [4]. |

Regulatory Significance in ISO/IEC 17025 and Drug Development

Uncertainty Analysis in ISO/IEC 17025 Accreditation

For testing and calibration laboratories, ISO/IEC 17025:2017 mandates the assessment and reporting of measurement uncertainty (MU) as a critical requirement for demonstrating technical competence [23] [24]. Clause 7.6 of the standard specifically addresses the evaluation of measurement uncertainty [24].

A common mistake during assessments is the use of incomplete uncertainty models, for instance, including only calibration uncertainty while ignoring other key contributors like sample preparation, environmental conditions, and operator variability [24]. Such weaknesses have a domino effect, impacting the validity of decision rules, statements of conformity (Clause 7.8.6), and the ability to ensure the validity of results (Clause 7.7) [24]. The 2017 revision of the standard introduced a stronger emphasis on risk-based thinking, requiring laboratories to systematically address risks to the quality of their results [25] [26].

Uncertainty Analysis in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD)

In drug development, the principles of uncertainty analysis are embedded in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD). MIDD uses quantitative models to facilitate drug development and regulatory decision-making, aiming to reduce costly late-stage failures and accelerate patient access to new therapies [27].

A "Fit-for-Purpose" approach is central to MIDD, meaning the selected modeling and uncertainty analysis techniques must be well-aligned with the specific Question of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) at a given development stage [27]. For example:

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models require robust uncertainty and variability analysis to gain regulatory acceptance for predicting drug-drug interactions or extrapolating to special populations.

- Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) models are inherently complex, and uncertainty analysis is crucial for establishing confidence in their predictions for dose selection and trial design [27] [28].

The emerging use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) in drug development further underscores the need for advanced uncertainty quantification. While AI projects can face high failure rates, generative AI shows high-value opportunities for accelerating modeling, simulation, and regulatory document creation, all of which rely on transparent uncertainty analysis [28].

Workflow and Implementation

The logical workflow for selecting and applying an uncertainty analysis method in a regulated laboratory or drug development setting is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions based on the experimental protocol for the activated sludge respiration inhibition test (ISO 8192:2007), a representative method for uncertainty analysis in a biological system [4].

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Uncertainty Analysis in Toxicity Testing

| Item | Function in the Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Activated Sludge | Serves as the biological matrix containing the microorganisms whose oxygen consumption is measured to assess toxicity [4]. |

| 3,5-Dichlorophenol | Used as a reference substance to standardize the toxicity test and validate the measurement method's performance [4]. |

| Oxygen Probe | The primary sensor for measuring dissolved oxygen concentration in the test vessel over time; its accuracy is a major uncertainty contributor [4]. |

| N-Allylthiourea (ATU) | A chemical inhibitor used to specifically suppress nitrification, allowing for the separate assessment of heterotrophic oxygen consumption inhibition [4]. |

| Test Medium (Peptone, Meat Extract, Urea, Salts) | Provides essential nutrients and maintains ionic strength, creating a standardized environment for microbial activity during the test [4]. |

| Temperature-Controlled Chamber | Maintains the test environment at a stable temperature (e.g., 22 ± 2 °C), as temperature fluctuation is a dominant uncertainty source [4]. |

Applied Uncertainty Analysis: Implementing GUM and Monte Carlo in Practice

Step-by-Step Guide to Conducting a GUM-Based Uncertainty Analysis

The Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) is an internationally recognized document that provides a standardized framework for evaluating and expressing measurement uncertainty. Developed by leading international standards organizations and first published in 1993, GUM establishes general rules applicable to a broad spectrum of measurements across different fields, from fundamental research to industrial applications [29] [7] [30]. The primary aim of GUM is to harmonize uncertainty evaluation practices, thereby ensuring reliability and facilitating the international comparison of measurement results [31] [29]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, applying a rigorous uncertainty analysis is not merely an academic exercise; it is a fundamental requirement for ensuring data integrity, assessing risk, and making defensible decisions based on measurement results. Compliance with standards such as ISO/IEC 17025, which requires uncertainty estimation for laboratory accreditation, further underscores its importance in regulated environments [4].

This guide is framed within a research context comparing the traditional GUM methodology, which relies on the law of propagation of uncertainty and a first-order Taylor series approximation, with the increasingly prevalent Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) method, a computational technique that propagates distributions by performing random sampling [4] [5] [30]. While GUM is the established benchmark, its limitations in handling highly nonlinear models or asymmetric output distributions are key drivers for the adoption of MCS, as evidenced by recent comparative studies in environmental and biomedical fields [4] [5].

Fundamental Concepts of Measurement Uncertainty

Before embarking on a step-by-step analysis, it is crucial to understand the core concepts. Measurement uncertainty is defined as a "parameter, associated with the result of a measurement, that characterizes the dispersion of the values that could reasonably be attributed to the measurand" [4]. In simpler terms, it quantifies the doubt about the measurement's result.

The GUM framework classifies methods for evaluating uncertainty components into two types:

- Type A Evaluation: Method of evaluation by the statistical analysis of a series of observations. This typically involves calculating the mean and standard deviation from repeated measurements [32].

- Type B Evaluation: Method of evaluation by means other than statistical analysis of series of observations. This involves using scientific judgment, manufacturer's specifications, calibration certificates, or other prior knowledge to estimate an uncertainty component [32].

The final combined uncertainty, denoted as u_c(y), is a single standard deviation equivalent that encompasses all identified uncertainty sources. For reporting purposes, particularly to provide a confidence interval, an expanded uncertainty (U) is calculated by multiplying the combined uncertainty by a coverage factor (k). Common coverage factors are k=2 for approximately 95% confidence and k=3 for 99% confidence, under the assumption of a normal distribution [30].

The GUM Step-by-Step Uncertainty Analysis Procedure

The process of calculating measurement uncertainty via the GUM methodology can be systematically broken down into a series of sequential steps. Different sources consolidate these steps slightly differently, but the core workflow remains consistent [33] [29] [7]. The following seven-step procedure provides a robust framework for conducting an analysis.

Step 1: Specify the Measurand and Measurement Process

The first step involves creating a clear plan by specifying the measurement in detail.

- Action: Document a clear statement of what is being measured (the measurand), the mathematical formula or model used to calculate it, the specific method or procedure followed, and the equipment employed [33].

- Example: For a drug concentration in a powder mixture, the measurand is the weight fraction

f, and the model isf = x / (x + y + z + ...), wherexis the drug quantity andy, z,...are excipient quantities [34]. The equipment would include the balances used to weigh each component.

List every possible factor that could contribute to uncertainty in the final result.

- Common Sources: These include instrument resolution, repeatability, environmental conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity), operator bias, calibration uncertainties of equipment, and material stability [33] [7]. A cause-and-effect diagram (fishbone diagram) can be a useful tool in this step to visually map out all potential influencers.

Step 3: Quantify the Uncertainty Components

Assign a numerical value to each source identified in Step 2.

- For Type A uncertainties: Calculate the standard deviation of the mean from repeated measurements [32].

- For Type B uncertainties: Use available information. For example, if a balance has a readability of ±0.1 mg, the uncertainty is derived from this value. The GUM provides guidance on assigning probability distributions (e.g., normal for calibration certificates, rectangular for digital instrument resolution) to convert specifications into standard uncertainties [33] [30].

Step 4: Characterize Uncertainties and Determine Sensitivity Coefficients

- Characterize Distribution: Classify each component as Type A or Type B and state its probability distribution (e.g., Normal, Rectangular, Triangular) [33].

- Sensitivity Coefficients (

c_i): These coefficients describe how much the output estimate (the measurand) changes with a small change in an input quantity. They are often determined from the partial derivative of the measurement model with respect to each input variable. For a modely = f(x1, x2, ...), the coefficient forx1isc1 = ∂y/∂x1[31] [34]. This step is crucial for converting input uncertainties into their contribution to the output's uncertainty.

Step 5: Convert Uncertainties to Standard Deviations

Ensure all uncertainty components are expressed as standard uncertainties, meaning they are in the form of a standard deviation. For a Type B evaluation with a rectangular distribution (due to a digital resolution of a), the standard uncertainty is u = a / √3 [33].

Step 6: Calculate the Combined Standard Uncertainty

Combine all the individual standard uncertainty components into a single combined standard uncertainty, u_c. This is typically done using the root-sum-square (RSS) method, which also incorporates the sensitivity coefficients [33] [7].

The general formula for non-correlated inputs is:

u_c(y) = √[ (c1 ⋅ u(x1))² + (c2 ⋅ u(x2))² + ... ]

Step 7: Calculate the Expanded Uncertainty

To obtain an interval expected to encompass a large fraction of the distribution of values, calculate the expanded uncertainty, U. This is done by multiplying the combined standard uncertainty by a coverage factor, k [33] [30].

U = k ⋅ u_c(y)

The choice of k (typically 2 or 3) is based on the desired level of confidence (e.g., 95% or 99%) and the effective degrees of freedom of the measurement (often estimated via the Welch-Satterthwaite formula) [5].

The workflow for this entire 7-step process is summarized in the following diagram:

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparative Studies

To ground the GUM methodology in practical research, this section outlines the experimental protocols from key studies that have directly compared GUM and Monte Carlo methods.

Protocol 1: Toxicity Assessment in Wastewater Treatment

This study quantified the measurement uncertainty of the ISO 8192:2007 method, which determines the inhibition of oxygen consumption in activated sludge, a critical test for protecting biological processes in wastewater treatment plants [4].

- Experimental Setup: Activated sludge from a municipal plant was utilized. The test substance was 3,5-dichlorophenol, a reference toxicant. The test medium was prepared with peptone, meat extract, urea, and salts. A test mixture with multiple dilution levels was prepared and aerated before transfer to a test vessel.

- Measurement Procedure: Oxygen consumption was measured in the vessel using a calibrated oxygen probe placed on a magnetic stirrer. The environment was maintained at

22 ± 2 °Cand a pH of7.5 ± 0.5. The oxygen consumption rate (R_i) was calculated from the slope of the oxygen concentration decrease over time:R_i = (ρ1 - ρ2) / Δt * 60mg/(L·h), whereρ1andρ2are oxygen concentrations at the start and end of the linear range, andΔtis the time interval in minutes [4]. - Uncertainty Analysis: The study evaluated a total of 29 uncertainty contributions, including temperature tolerance, measurement time interval, and oxygen probe accuracy. Both GUM and MCS were applied to propagate these uncertainties for the oxygen consumption rate and the derived percentage inhibition.

Protocol 2: Perspiration Measurement System

This research evaluated the uncertainty of a system designed to measure human perspiration rate, a biomedical measurement system involving multiple input parameters [5].

- Experimental Setup: The system consisted of a ventilated chamber covering a skin area, with ambient air sucked in by a pump. The system was instrumented with a flow meter for airflow rate and sensors for temperature and relative humidity at the inlet and outlet.

- Measurement Procedure: The perspiration rate (

G) was calculated indirectly from the measurements of airflow rate (m), inlet air density (ρ_in), and the absolute humidity of the inlet (d_in) and outlet (d_out) air, using the formula:G = m * (d_out - d_in) / ρ_in[5]. - Uncertainty Analysis: Uncertainty sources for each direct measurement (e.g., flow meter resolution and repeatability, sensor accuracy) were quantified. The propagation of these uncertainties through the perspiration rate equation was performed using both the GUM framework and Monte Carlo simulation, allowing for a direct comparison of the results and the underlying assumptions of each method.

Comparative Analysis: GUM vs. Monte Carlo Simulation

The following tables synthesize quantitative data and key characteristics from studies comparing GUM and Monte Carlo methods, highlighting the performance and applicability of each approach.

Table 1: Quantitative Results from Comparative Studies

| Study Application | Key Inputs & Model | GUM Result | Monte Carlo Result | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity Test (O₂ Inhibition) [4] | 29 inputs (Temp, Time, Probe). Nonlinear model for % inhibition. | Slightly underestimated uncertainty at low toxicant concentrations. | Revealed asymmetric distributions; provided more realistic uncertainty intervals. | GUM reliable for linear parts (O₂ rate); MCS superior for nonlinear outputs (% inhibition). |

| Perspiration System [5] | Airflow, density, humidity. G = m*(d_out - d_in)/ρ_in. |

Combined uncertainty: 6.81 × 10⁻⁶ kg/s. |

Validated the GUM result for this specific model. | Both methods agreed well for this system, demonstrating GUM's adequacy for less complex models. |

| Drug Concentration in Mixture [34] | Masses of drug x and excipients y,z.... f=x/(x+y+z+...). |

Relative uncertainty: df/f = (dx/x) * [1 + (n-1)f]. |

(Not applied in cited study) | Highlights GUM's use of a 1st-order Taylor series. Model shows uncertainty increases with number n of ingredients. |

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of GUM and Monte Carlo Simulation

| Feature | GUM Method | Monte Carlo Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Law of propagation of uncertainty; 1st-order Taylor series approximation [5]. | Repeated random sampling from input probability distributions; numerical propagation [4] [30]. |

| Model Complexity | Best suited for linear or mildly nonlinear models [5]. | Handles highly nonlinear models and complex systems without simplification [4] [5]. |

| Output Distribution | Assumes output is normal or t-distributed for expanded uncertainty [30]. | Generates an empirical output distribution, revealing asymmetry if present [4] [30]. |

| Computational Load | Low; analytical calculation. | High; requires thousands or millions of model evaluations to stabilize results [5]. |

| Primary Limitation | Can produce errors for strong nonlinearities; may underestimate uncertainty for asymmetric distributions [5] [30]. | Selection of correct input distributions is critical; runtime can be long for complex systems [5]. |

The relationship between the two methods and their optimal use cases is illustrated below. The GUM Supplement 1 officially endorses MCS as a complementary method, particularly for validating GUM results or when GUM's assumptions are violated [4] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and software tools essential for conducting uncertainty analyses in experimental research, particularly in pharmaceutical and environmental contexts as cited.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Software Tools

| Item Name | Function / Role in Uncertainty Analysis | Example from Research Context |

|---|---|---|

| 3,5-Dichlorophenol | Reference toxicant substance used to calibrate and validate bioassay responses. | Served as the reference substance in the ISO 8192:2007 toxicity test to ensure international comparability of inhibition results [4]. |

| Activated Sludge | A complex microbial ecosystem used as the biological sensor in toxicity inhibition tests. | Sourced from a municipal wastewater plant; its oxygen consumption response to toxins is the core measurand [4]. |

| N-allylthiourea (ATU) | Chemical inhibitor used to selectively suppress nitrification, allowing isolation of heterotrophic oxygen consumption. | Critical for modifying the standard test to measure specific inhibition pathways, adding a source of methodological uncertainty [4]. |

| Calibrated Oxygen Probe | Sensor for measuring dissolved oxygen concentration, a direct source of measurement uncertainty. | A dominant uncertainty contributor; its accuracy, calibration, and resolution directly impact the oxygen consumption rate calculation [4]. |

| SUNCAL Software | Free, open-source software for performing uncertainty calculations using both GUM and Monte Carlo methods. | Recommended for practical application, enabling researchers to perform the necessary statistical calculations and propagations [32]. |

| Precision Balances | Instrument for determining the mass of drug and excipients; a primary source of uncertainty in formulation. | Its sensitivity (dx) is a key term in the uncertainty model for drug concentration in powder mixtures [34]. |

This guide has detailed the step-by-step procedure for conducting a GUM-based uncertainty analysis, from specifying the measurand to reporting the expanded uncertainty. The comparative analysis with the Monte Carlo method reveals a clear landscape: the GUM framework provides a robust, analytically efficient, and standardized methodology that is perfectly adequate for a wide range of measurement problems, particularly those that are linear or only mildly nonlinear [5]. However, research demonstrates that for systems with significant nonlinearities or those that produce asymmetric output distributions, such as certain toxicity inhibition calculations, the GUM method can underestimate uncertainty [4]. In these cases, the Monte Carlo simulation offers a more powerful and reliable alternative, capable of revealing the true structure of the output uncertainty without relying on first-order approximations [5] [30].

For the modern researcher, the choice is not necessarily binary. The most rigorous approach, endorsed by the GUM Supplement 1, involves using the two methods in concert. One can use the GUM method for its efficiency and ease, while employing Monte Carlo simulation to validate the results, especially when operating near the boundaries of the GUM's applicability. This combined strategy ensures the highest level of confidence in uncertainty estimates, thereby strengthening the foundation of scientific conclusions and regulatory decisions in drug development and beyond.

Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing a Monte Carlo Simulation for Uncertainty

Uncertainty analysis is a cornerstone of reliable scientific research, ensuring that measurement results are accompanied by a quantifiable indicator of their reliability. For years, the Guide to the Expression of Uncertainty in Measurement (GUM) has provided the foundational framework for this analysis [19]. Its analytical, first-principles approach, however, presents challenges for complex, non-linear systems common in modern research. In response, the Monte Carlo Simulation (MCS) method has emerged as a powerful computational alternative [35]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two methodologies, arming researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to select the appropriate tool for their uncertainty analysis needs. The core distinction lies in their approach: GUM uses an analytical method based on linear approximations and sensitivity coefficients, while MCS uses computational power to propagate distributions through random sampling, making it particularly suited for complex models [35] [4].

Theoretical Foundation: GUM and Monte Carlo Simulation

The GUM Framework

The GUM provides a standardized, internationally recognized procedure for uncertainty estimation [4] [19]. Its methodology is fundamentally analytical. It requires building a detailed mathematical model of the measurement process and calculating the combined standard uncertainty by determining the separate effect of each input quantity through sensitivity analysis, which often involves computing complex partial derivatives [35]. A fundamental premise of the GUM is the assumption that known systematic errors are identified and corrected early in the evaluation, with the remaining uncertainty comprising components from both random errors and the uncertainty of the corrections themselves [19]. For many linear models with well-understood inputs, this approach is robust and effective.

The Monte Carlo Simulation Method

In contrast, Monte Carlo Simulation is a probabilistic method that relies on repeated random sampling to estimate numerical results [36]. Instead of solving a deterministic problem analytically, MCS uses randomness to simulate a process thousands of times, thereby building a distribution of possible outcomes [35]. This process involves defining probability distributions for all input variables and then running a large number of iterations, where for each iteration, values for the inputs are randomly drawn from their respective distributions and used to compute an output value [37] [38]. The resulting collection of output values forms a probability distribution, from which uncertainty estimates can be directly derived without the need for complex differential equations [19].

Comparative strengths and limitations

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of GUM and Monte Carlo Methods

| Feature | GUM Method | Monte Carlo Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Core Approach | Analytical (first-principles) | Computational (numerical sampling) |

| Mathematical Basis | Law of uncertainty propagation; Taylor series expansion | Repeated random sampling & statistical analysis |

| Handling Non-Linearity | Can be unreliable; neglects higher-order terms [35] | Naturally accounts for all non-linearities [35] |

| Handling Correlated Inputs | Complex and sometimes unreliable [35] | Can directly model correlation effects [35] |

| Output Distribution | Assumes/outputs a standard (e.g., normal, t-) distribution [4] | Empirically generates any output distribution, reveals asymmetries [4] |

| Skill Requirement | Advanced mathematical skills for derivatives [19] | Less advanced math; requires programming/software knowledge [19] |

Experimental Comparison: A Case Study in Toxicity Testing

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

A 2025 study quantifying the measurement uncertainty of the ISO 8192:2007 method, which determines the inhibition of oxygen consumption in activated sludge, provides robust experimental data for a direct comparison [4]. The study evaluated up to 29 separate uncertainty contributions.

- Measured System: Inhibition of oxygen consumption in activated sludge using 3,5-dichlorophenol as a reference substance [4].

- Key Measured Parameters: Oxygen consumption rate and percentage inhibition [4].

- Methodology: The uncertainty of the method was evaluated using both the GUM guideline and Monte Carlo Simulation (validated with 100,000 iterations) to facilitate a direct comparison of the results [4].

- Dominant Uncertainty Sources: The study identified temperature tolerance, measurement interval, and oxygen probe accuracy as the dominant contributors, accounting for over 90% of the total uncertainty [4].

Quantitative Results and Data Comparison

The experimental data allows for a clear, objective comparison of the outputs from both methods.

Table 2: Experimental Results from Toxicity Testing Uncertainty Analysis