Handheld Spectrometers in Field Analysis: Revolutionizing On-Site Drug Development and Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative impact of handheld spectrometers for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedical fields.

Handheld Spectrometers in Field Analysis: Revolutionizing On-Site Drug Development and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative impact of handheld spectrometers for researchers and scientists in drug development and biomedical fields. It details the core principles and key technologies—such as Raman, NIR, and MS—that enable portable, lab-grade analysis. The scope covers practical field applications from raw material identification to counterfeit drug detection, addresses common operational challenges and optimization strategies, and provides a comparative analysis of performance against traditional methods. Aimed at empowering professionals with the knowledge to implement these tools, the content synthesizes the latest technological advancements and real-world case studies to demonstrate enhanced efficiency, compliance, and decision-making in field-based research.

The Fundamentals of Handheld Spectrometry: Bringing the Lab to the Field

Handheld spectrometers are compact, portable analytical instruments that measure the interaction between light and matter to determine the chemical composition of samples. Their development represents a significant shift in spectroscopic analysis, moving technology from the laboratory directly into the field for real-time, on-site measurements. These instruments maintain the core principles of traditional spectroscopy while incorporating advanced miniaturization technologies to achieve portability without sacrificing critical analytical capabilities. The global market for miniaturized spectrometers is experiencing substantial growth, projected to reach $1.91 billion by 2029, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.8%, reflecting their expanding application across multiple sectors [1].

The fundamental value proposition of handheld spectrometers lies in their ability to provide rapid, non-destructive analysis across diverse environments including agricultural fields, pharmaceutical manufacturing facilities, crime scenes, and remote environmental monitoring sites. Unlike traditional benchtop instruments that require sample transportation and specialized laboratory settings, handheld versions enable immediate decision-making at the point of need, significantly reducing analysis time from days to seconds while maintaining adequate analytical performance for most field applications [2] [3].

Core Operating Principles

Fundamental Spectroscopy Concepts

All spectroscopic techniques, including handheld variants, operate on the principle of light-matter interaction. When light strikes a material, several phenomena can occur including absorption, reflection, scattering, and emission. Handheld spectrometers measure these interactions to generate spectra that serve as molecular fingerprints, enabling material identification and quantification.

The relationship between incident light and the resulting spectral response follows the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorption of light by a substance is directly proportional to its concentration and the path length. This fundamental principle enables quantitative analysis across various spectroscopic techniques. Mathematically, this is expressed as A = εlc, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient, l is the path length, and c is the concentration [4].

Handheld instruments typically operate within specific regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, with the most common being:

- Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis): 190-800 nm

- Near-Infrared (NIR): 780-2500 nm

- Raman: Typically using visible or NIR excitation lasers

Each spectral region provides different information about molecular structure and composition, with selection depending on the specific application requirements and sample characteristics [5] [3].

Technology Miniaturization Approaches

The transformation from benchtop to handheld spectrometers has been enabled by several miniaturization technologies:

- Micro-Optical Systems: Replacement of conventional optical components with micro-mirrors, miniature lenses, and fiber optics

- Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS): Implementation of tiny mechanical and electro-mechanical elements using microfabrication technology

- Advanced Detector Arrays: Development of compact, high-sensitivity detector arrays such as CCD and CMOS sensors

- Integrated Computational Elements: Combination of hardware with sophisticated algorithms to reconstruct spectral information [4] [6]

These technological advances have enabled spectrometer footprints that are orders of magnitude smaller than traditional systems while maintaining sufficient analytical performance for field applications.

Key Handheld Spectrometer Technologies

Handheld Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectrometers

Handheld NIR spectrometers analyze molecular overtone and combination vibrations, providing information primarily about organic functional groups containing C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds. These instruments typically operate in the wavelength range of 700-2500 nm and are particularly valuable for analyzing complex organic matrices [2] [3].

The operation of handheld NIR spectrometers involves illuminating the sample with a broadband NIR source and measuring the reflected or transmitted light using a miniaturized detector array. The resulting spectrum contains broad, overlapping absorption bands that require multivariate calibration models (chemometrics) for interpretation. These calibration models correlate spectral features with reference analytical data, enabling quantitative predictions for new samples [2].

NIR spectroscopy is particularly well-suited to handheld implementation due to the relatively straightforward optical designs and the commercial availability of robust components. Modern handheld NIR spectrometers, such as the trinamiX PAL Two, weigh approximately 550 grams and operate across an extensive 1300–2350 nm wavelength range with performance characteristics approaching those of benchtop systems [1].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Handheld NIR Spectrometers

| Parameter | Typical Range | Application Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | 700-2500 nm | Determines chemical functional groups detectable |

| Spectral Resolution | 5-20 nm | Affects ability to distinguish closely spaced absorption features |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Varies by instrument | Impacts detection limits and measurement precision |

| Measurement Time | 1-30 seconds | Affects throughput and suitability for real-time monitoring |

| Calibration Requirements | Application-specific | Determines readiness for different sample types |

Handheld Raman Spectrometers

Handheld Raman spectrometers measure inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source. When light interacts with molecular vibrations, a small fraction undergoes energy shifts that provide detailed information about molecular structure and chemical bonding. Raman spectroscopy is particularly valuable for identifying specific compounds through their unique vibrational fingerprints [7] [8].

These instruments have seen significant advancement over the past decade, with reductions in both size and cost while improving performance. Modern handheld Raman systems typically employ one of two approaches to mitigate the inherent weakness of the Raman effect:

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): Utilizes nanostructured metal surfaces to enhance Raman signals by factors of 10⁴-10⁸

- Resonance Raman Spectroscopy: Employs laser wavelengths that match electronic transitions of the target molecules to increase sensitivity

Recent innovations include SERRS-enabled immunoassay systems that combine the specificity of immunoassays with the sensitivity of resonance Raman, creating platforms adaptable to a broad range of biomarkers and sample types. These systems are being developed for point-of-care diagnostics targeting diseases like tuberculosis and pancreatic cancer [7].

Handheld Raman spectrometers are increasingly deployed in challenging environments including low-resource healthcare settings for diagnosing deadly diseases and detecting counterfeit medications. Their ability to provide immediate analysis without central laboratory facilities makes them particularly valuable in remote locations and for rapid screening applications [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Handheld Spectrometer Technologies

| Parameter | Handheld NIR | Handheld Raman |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Molecular overtone and combination vibrations | Inelastic light scattering |

| Excitation Source | Broadband NIR source | Monochromatic laser (typically 785 nm or 1064 nm) |

| Spectral Information | Broad, overlapping bands | Sharp, specific spectral features |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal often none | Minimal, but may require SERS substrates for trace detection |

| Primary Applications | Agriculture, food, pharmaceuticals | Pharmaceutical verification, forensic analysis, medical diagnostics |

| Key Advantage | Rapid quantitative analysis | Specific compound identification |

| Key Limitation | Requires extensive calibration | Fluorescence interference from some samples |

Reconstructive Spectrometers

A transformative advancement in spectrometer miniaturization is the emergence of reconstructive spectrometers, which combine miniaturized encoding hardware with advanced computational algorithms. These systems represent a paradigm shift from conventional spectroscopic approaches by replacing traditional wavelength separation components with encoding elements and mathematical reconstruction [6].

The operational principle of reconstructive spectrometers involves three sequential stages:

- Calibration: Characterizing the spectral response of the encoder using light sources with known spectral profiles

- Measurement: Exposing the device to unknown light and recording the encoded signal

- Reconstruction: Employing computational algorithms to recover the original spectrum from the encoded measurement

Mathematically, this process is described by the equation I = R · S, where I is the measured signal vector, R is the response matrix of the encoding system, and S is the unknown spectrum to be reconstructed. The reconstruction process typically employs compressive sensing theory and machine learning algorithms to solve this underdetermined inverse problem [6].

The significant advantage of reconstructive spectrometers is their potential for extreme miniaturization while maintaining high performance. Some implementations approach single-pixel spectrometer configurations, where miniaturized detectors with tunable spectral responses replace traditional dispersive optics and detector arrays. This architecture enables spectrometer integration into increasingly compact devices including smartphones and wearable technology [6].

Performance Considerations and Limitations

Performance Trade-offs in Miniaturization

The miniaturization of spectroscopic instrumentation inevitably involves performance compromises compared to laboratory systems. Understanding these trade-offs is essential for appropriate application selection and results interpretation:

- Reduced Sensitivity: Smaller optical components collect less light, resulting in lower signal-to-noise ratios compared to benchtop instruments [2]

- Spectral Resolution Limitations: Closely spaced spectral features may be harder to distinguish due to limitations in miniaturized optical designs [2]

- Limited Spectral Range: Handheld systems typically cover narrower wavelength ranges optimized for specific applications

- Calibration Dependency: NIR instruments particularly require application-specific calibration models that must be properly developed and validated [2]

Despite these limitations, handheld spectrometers provide adequate performance for a wide range of field applications where the benefits of portability and immediate analysis outweigh the performance compromises.

Methodological Protocols for Field Deployment

Successful deployment of handheld spectrometers requires careful methodological planning. The following protocols ensure reliable results:

Instrument Calibration and Validation

Pre-deployment Calibration:

- Verify instrument performance using certified reference materials

- Confirm wavelength accuracy using holmium oxide or other wavelength standards

- Validate photometric response using neutral density filters or other intensity standards

Field Validation:

- Analyze quality control samples at regular intervals during field use

- Implement standard operating procedures for sample presentation and measurement

- Document environmental conditions that may affect measurements (temperature, humidity)

Sample Presentation Protocols

Consistent sample presentation is critical for reproducible results:

Solid Samples:

- Maintain consistent packing density for powdered materials

- Ensure uniform surface presentation for reflectance measurements

- Control particle size distribution through grinding or other preparation when necessary

Liquid Samples:

- Use appropriate pathlength cells for transmission measurements

- Minimize air bubbles in sample presentation

- Account for container effects when measuring through packaging

Applications in Field Analysis Research

Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Applications

Handheld spectrometers have transformed pharmaceutical analysis and biomedical diagnostics by enabling real-time measurements at the point of need:

Pharmaceutical Manufacturing:

- Raw material identification and verification

- In-process monitoring of drug formulation processes

- Finished product quality verification

Counterfeit Drug Detection:

- Rapid authentication of pharmaceutical products

- Identification of substandard medications in supply chains

- Field screening of suspicious materials by regulatory agencies

Biomedical Diagnostics:

- Disease biomarker detection using SERRS-based platforms

- Tuberculosis diagnosis through ManLAM biomarker detection [7]

- Point-of-care testing for rapid diagnosis in resource-limited settings

The development of SERRS-enabled immunoassays represents a particularly significant advancement, creating adaptable platforms for detecting diverse biomarkers and pathogens. These systems are being designed to support multiplexed analyses for conditions like tuberculosis and pancreatic cancer, with the potential to dramatically reduce diagnostic timeframes in endemic regions [7].

Agricultural and Environmental Monitoring

Handheld spectrometers enable in-field analysis of plant physiology and environmental contaminants:

Plant Health Monitoring:

- Non-destructive assessment of plant carotenoids, flavonoids, and other phytochemicals [8]

- Early detection of plant stress through chemical signature changes

- In vivo monitoring of plant metabolic processes

Environmental Analysis:

- Identification of microplastics in environmental samples [8]

- Detection of pollutants in water and soil

- On-site screening of industrial emissions

The non-destructive nature of spectroscopic analysis is particularly valuable for agricultural applications, allowing repeated measurements on the same plants throughout growth cycles without damaging valuable specimens.

Experimental Workflow and Research Reagent Solutions

Generalized Experimental Workflow

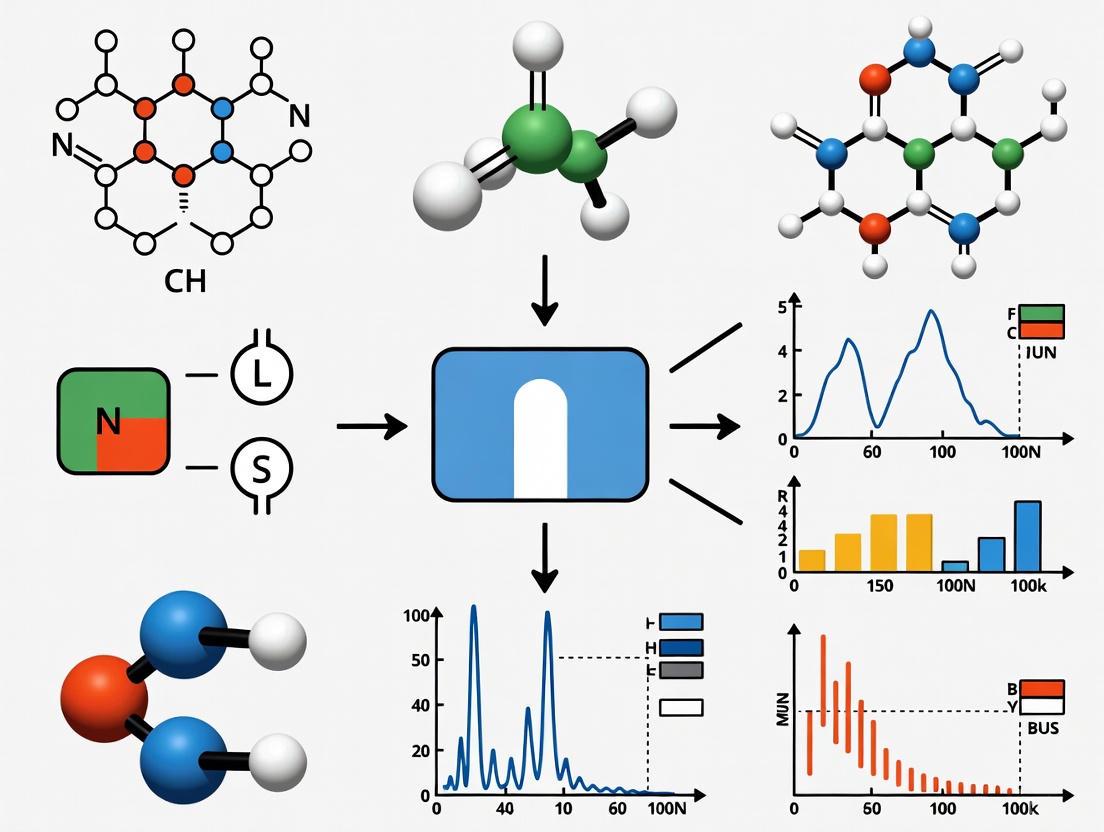

The following diagram illustrates the standard operational workflow for handheld spectrometer analysis:

Diagram 1: Handheld Spectrometer Analysis Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Detection

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Handheld Spectrometry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates | Enhance Raman signals via plasmonic effects | Gold nanoparticles, silver colloids for trace detection |

| Calibration Standards | Verify instrument performance | Holmium oxide for wavelength verification |

| Reference Materials | Method development and validation | Certified chemical standards with known purity |

| Surface Functionalization Agents | Enable specific molecular recognition | Thiol compounds for gold surface modification |

| Immunoassay Components | Provide biological specificity | Antibodies for capture and detection in SERRS platforms |

| Sample Presentation Accessories | Standardize measurement conditions | Reflection cups, transmission cells, vial holders |

Emerging Technological Trends

The field of handheld spectrometry continues to evolve through several key technological developments:

Integration with Artificial Intelligence:

- Machine learning algorithms for enhanced spectral interpretation and classification

- AI-assisted calibration transfer between instruments

- Automated quality assessment of spectral data

Advanced Materials and Nanotechnology:

- Novel SERS substrates with enhanced reproducibility and sensitivity

- Functionalized nanoparticles for specific target recognition

- Two-dimensional materials for miniaturized photonic components

Device Connectivity and IoT Integration:

- Bluetooth and wireless connectivity for data transmission

- Cloud-based spectral libraries and processing algorithms

- Integration with mobile computing platforms for extended capabilities

These technological advancements are driving handheld spectrometers toward increasingly sophisticated applications while simultaneously improving ease of use and accessibility for non-specialist operators.

Handheld spectrometers represent a transformative technology that has fundamentally changed analytical capabilities across numerous field applications. By understanding their core operating principles, performance characteristics, and methodological requirements, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful tools for diverse analytical challenges. The continuing evolution of miniature spectrometer technologies promises even greater capabilities in the future, potentially enabling applications not yet envisioned while making sophisticated chemical analysis increasingly accessible across scientific disciplines, industrial sectors, and geographic regions.

The advent of portable spectroscopy is transforming field research across pharmaceuticals, environmental science, and forensics. These handheld instruments empower scientists to perform non-destructive, real-time analysis directly at the sample source, bypassing the delays and potential degradation associated with traditional lab transport. For researchers and drug development professionals, this capability is accelerating decision-making in critical applications from raw material verification and counterfeit drug detection to environmental contaminant monitoring [9] [10] [3]. This technical guide details the core technologies, performance characteristics, and experimental methodologies underpinning portable Raman, Near-Infrared (NIR), Infrared (IR), and Mass Spectrometry (MS) systems, providing a framework for their effective implementation in field-based research.

Table 1: Core Technologies in Portable Spectroscopy

| Technology | Core Principle | Primary Field Applications | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light (e.g., a laser) [10]. | Pharmaceutical verification, material ID, counterfeit detection [9] [10]. | Minimal sample prep, works through packaging, specific molecular fingerprinting [10]. |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Absorption of light in the NIR region (780-2500 nm) by molecular overtone and combination vibrations [3]. | Pharmaceutical quality, agricultural quality, natural medicine analysis [3]. | Deep penetration, rapid quantitative analysis (e.g., moisture, API concentration) [3]. |

| IR Spectroscopy | Absorption of IR light by molecular bond vibrations. | Chemical manufacturing, forensic analysis, polymer ID. | Widely available, strong library support for compound matching. |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Ionization of sample molecules and separation based on mass-to-charge ratio. | Life sciences, drug discovery, environmental contaminant detection [11]. | Unmatched sensitivity and specificity for trace-level analysis [11]. |

Technology-Specific Analysis & Performance

Portable Raman Analyzers

Portable Raman systems dominate the market for on-site molecular identification, with the segment valued at US$573.0 million in 2025 and projected to reach US$1,319.0 million by 2032, growing at a CAGR of 7.4% [9]. Their growth is fueled by integration with artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning algorithms like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers, which automate the interpretation of complex spectral data and enhance accuracy in noisy environments [10]. This AI-guidance is revolutionizing pharmaceutical analysis, enabling breakthroughs in drug development, impurity detection, and early disease diagnostics [10].

A key application is counterfeit drug detection. The experimental protocol involves:

- Spectral Library Creation: Building a validated library of reference spectra for authentic pharmaceutical products using a portable Raman spectrometer with a 785 nm or 1064 nm laser to minimize fluorescence [10] [12].

- Field Measurement: Directly aiming the portable spectrometer's laser through the packaging (blister pack, bottle) onto the tablet or liquid sample to collect its Raman spectrum without opening the container [10].

- AI-Powered Analysis: Software, such as OMNIC Spectra or AI-powered platforms, compares the unknown sample's spectrum against the reference library. Deep learning models identify subtle spectral features indicative of counterfeit substances, excipients, or incorrect API concentration, providing a pass/fail result [10] [12].

- Validation: Results are validated by comparing the correlation value or spectral match score against a pre-defined threshold, with results below the threshold flagged as potentially counterfeit [12].

Portable NIR & IR Spectrometers

Portable NIR spectroscopy is a revolutionary tool for non-destructive analysis in biomedical and pharmaceutical realms [3]. Its growth is driven by the development of novel miniaturized spectrometers and its application in ensuring medicinal quality [3]. A key quantitative application is the determination of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) concentration in tablets. The methodology involves:

- Calibration Set Development: A representative set of tablets with known API concentrations (verified by HPLC) is assembled.

- NIR Spectral Acquisition: NIR spectra are collected for each tablet in the set using a portable NIR spectrometer.

- Multivariate Model Building: Using software like SIMCA, a Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression model is built that correlates the spectral features (X-matrix) with the known API concentrations (Y-matrix). The model is validated using cross-validation to ensure predictive power [13].

- Prediction: The calibrated model is deployed on the portable instrument. To analyze an unknown tablet, its NIR spectrum is collected and fed into the model, which instantly predicts the API concentration.

Portable Mass Spectrometers

While less common than optical techniques, portable Mass Spectrometers are seeing rapid growth, particularly in the life science and drug discovery segments [11]. They are invaluable for applications requiring extreme sensitivity, such as detecting trace-level contaminants or metabolites in the field. Their adoption is facilitated by miniaturization of components, including mass analyzers and vacuum systems. The experimental workflow for on-site environmental contaminant detection typically involves:

- Sample Introduction: A solid or liquid sample is collected and introduced via a portable thermal desorption or membrane inlet system.

- Soft Ionization: The sample is ionized using techniques like electrospray ionization (ESI) or photoionization to minimize fragmentation.

- Mass Analysis: Ions are separated by a miniature mass analyzer (e.g., quadrupole or ion trap).

- Data Interpretation: The resulting mass spectrum is compared against integrated libraries for compound identification, providing conclusive evidence of contaminant presence.

Market Outlook & Quantitative Data

The global market for mobile and portable spectrometers is experiencing robust growth, valued at USD 2.47 Billion in 2025 and projected to cross USD 5.96 Billion by 2035, expanding at a CAGR of more than 9.2% [11]. This growth is fueled by the surge in mass spectrometry analysis by medical professionals, rising utilization in food contamination detection, and the increasing adoption of security and analytical instruments [11].

Table 2: Portable Spectroscopy Market Outlook & Application Segmentation

| Segment | Market Data & Forecast | Key Drivers & Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Market | $2.47B (2025) to $5.96B (2035); CAGR: 9.2% [11]. | Rise in field-based analysis, demand for rapid on-site results, technological miniaturization [11]. |

| Raman Segment | $573M (2025) to $1,319M (2032); CAGR: 7.4% [9]. | Counterfeit drug detection, pharmaceutical quality control (QC), AI integration [9] [10]. |

| By Application | Drug Discovery segment anticipated to achieve notable CAGR (2025-2035) [11]. | Growing use in drug R&D and validation by medicinal chemists [11]. |

| By Region | North America holds >42.8% share; Asia-Pacific is fastest-growing [11]. | Advanced R&D infrastructure in North America; dynamically growing pharmaceutical sector in Asia-Pacific [11]. |

Essential Workflows & Data Interpretation

A generalized, optimized workflow for field analysis with a portable spectrometer is outlined in the diagram below, illustrating the process from sample collection to final reporting.

Critical to this workflow is the data interpretation phase. For Raman and IR, this often involves spectral library searching (e.g., using libraries from Aldrich or Cayman Chemical) [12]. For NIR, Multivariate Data Analysis (MVDA) is essential. Software like SIMCA provides a specialized spectroscopy skin that streamlines the creation of PCA, PLS, and OPLS models, allowing researchers to perform quantitative calibration and classify samples directly in the field [13]. The integration of Python scripts in such software further enables the automation of complex analytical workflows [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Software Solutions

Successful field deployment relies on both consumables and sophisticated software for data analysis and management.

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Portable Spectroscopy

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Reference Libraries | Databases of known compound spectra for identification [12]. | Aldrich Raman Condensed Phase Library for forensic drug identification [12]. |

| Multivariate Data Analysis (MVDA) Software | Software for building quantitative and classification models from complex spectral data [13]. | SIMCA with Spectroscopy Skin for developing PLS models to predict API concentration from NIR spectra [13]. |

| System Qualification Standards | Certified reference materials for verifying instrument performance [12]. | ValPro System Qualification for ensuring Raman spectrometer meets regulatory compliance specs [12]. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging & Analysis Software | Software for processing and visualizing chemical maps from spectroscopic imaging [14]. | MountainsSpectral for processing and correlating confocal Raman imaging maps with other microscopy data [14]. |

| Open-Source Analysis Platforms | Free, modifiable software for foundational visualization and analysis of imaging spectroscopy data [15]. | WISER (Workbench for Imaging Spectroscopy Exploration and Research) for spatial/spectral subsetting and analysis of image cubes [15]. |

Portable Raman, NIR, IR, and MS technologies have unequivocally shifted advanced chemical analysis from the centralized laboratory to the field. Driven by miniaturization, AI-enhanced data interpretation, and robust multivariate software, these tools provide researchers and drug development professionals with immediate, actionable insights. The significant market growth and continual technological advancements underscore their transformative role. As these portable systems become even more sensitive, cost-effective, and integrated with cloud data management, their capacity to accelerate research, ensure product quality, and safeguard public health on a global scale will only expand.

The paradigm of chemical analysis has fundamentally shifted from bringing samples to the laboratory to bringing the laboratory to the sample [16]. This transformation is powered by three interconnected technological forces: the miniaturization of optical components, the pervasive connectivity of modern electronics, and the manufacturing economies of scale driven by the consumer electronics industry [17] [18]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this convergence has enabled handheld spectrometers to become viable alternatives to traditional benchtop systems for field-based analysis, providing real-time, on-the-spot molecular insights that accelerate decision-making in applications from raw material verification to illicit drug identification [19] [20] [21].

This technical guide examines the core technologies driving this revolution, provides detailed experimental methodologies for field deployment, and analyzes the performance characteristics of modern handheld spectrometer systems within the context of field-based research applications.

Core Technological Drivers

Miniaturization: From Benchtop to Handheld

Miniaturization has replaced traditional bulky optical components with advanced micro-technologies, enabling laboratory-grade performance in handheld form factors [17].

Key Enabling Technologies:

- Microelectromechanical Systems (MEMS): MEMS-based diffraction gratings and interferometers have replaced traditional bulky optical components, significantly reducing size while maintaining spectral resolution [17].

- Advanced Detectors: Miniaturized charge-coupled devices (CCD) and complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) detectors capture spectral data with high sensitivity in compact packages [17].

- Solid-State Light Sources: Compact diode lasers and LEDs serve as excitation sources, reducing power consumption and enhancing portability [17].

- Novel Photonic Designs: Breakthroughs include photodetectors capable of measuring from ultraviolet to near-infrared (400-1000 nm) wavelengths while operating at voltages of less than 1 V in packages as small as a few square millimeters [22].

Connectivity: The Data Ecosystem

Modern handheld spectrometers integrate seamlessly into digital workflows through multiple connectivity layers that enhance their utility in research environments.

Connectivity Framework:

- Embedded Processing: Onboard digital signal processing (DSP) units and AI-driven spectral analysis enable real-time data processing without external computing power [17].

- Wireless Communication: Connectivity via IoT or Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) devices enables real-time data transmission to cloud platforms and laboratory information systems [16].

- Cloud Integration: Smartphone and cloud integration allows real-time data analysis, collaboration, and centralized database management [18].

- Cybersecurity: Hybrid Graph Convolutional Network (GCN)-transformer AI models can detect cyberattacks on networked wearables, ensuring sensitive spectral data remains secure [16].

Consumer Electronics Revolution

The consumer electronics industry has provided critical enabling technologies that have dramatically reduced the size, cost, and power requirements of handheld spectrometers.

Cross-Industry Technological Transfer:

- Component Manufacturing Scale: The widespread manufacturing of components like diode lasers (developed for CD and Blu-ray players) and advances in telecommunications have dramatically reduced costs [20].

- Battery Technology: Improvements in energy density from consumer electronics have enabled longer field operation [18].

- Display Interfaces: Touchscreen interfaces developed for smartphones and tablets have been adapted for intuitive spectrometer operation [19] [17].

- Global Market Growth: The mobile spectrometers market is projected to grow from USD 1.47 billion in 2025 to USD 2.46 billion by 2034, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 7.7% [18].

Technical Performance and Methodologies

Experimental Protocol: Field Deployment of Portable NIR for Drug Identification

The following detailed methodology is adapted from a 2024 study on portable NIR technology for identifying and quantifying Australian illicit drugs [21].

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable NIR Spectrometer: Viavi Solutions Inc. MicroNIR [21]

- Sample Set: 608 illicit drug specimens seized by law enforcement [21]

- Reference Method: Laboratory-grade chromatographic systems for validation [21]

- Software: NIRLAB infrastructure with chemometric modeling capabilities [21]

Procedure:

- Sample Acquisition: Collect spectra directly from drug specimens in the field with minimal preparation [21].

- Spectral Collection: Perform NIR scans across the appropriate wavelength range (e.g., 800-2500 nm) [17].

- Model Application: Process spectra through pre-trained machine learning algorithms optimized for target analytes [21].

- Identification & Quantification: Classify drug type and estimate purity based on spectral features [21].

- Validation: Confirm results using reference laboratory methods (e.g., GC-MS) for a subset of samples [21].

Performance Metrics: The study demonstrated high accuracy rates for drug identification: 98.4% for crystalline methamphetamine HCl, 97.5% for cocaine HCl, and 99.2% for heroin HCl [21]. Quantification was also highly accurate, with 99% of values falling within the relative uncertainty of ±15% [21].

Performance Comparison of Handheld Spectrometry Techniques

Table 1: Technical Comparison of Handheld Spectrometry Technologies

| Technology | Detection Principle | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy [17] | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic laser light | Pharmaceutical verification [19], illicit drug identification [23], forensic analysis | Non-destructive testing [23], ability to scan through packaging [23], minimal sample preparation | Fluorescence interference [17], limited sensitivity for low-concentration components in mixtures [20] |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy [17] | Absorption of light in 800-2500 nm range | Drug quantification [21], agricultural analysis, food quality testing | Non-destructive, real-time measurements with minimal sample preparation [17] | Broad, overlapping absorption bands require chemometrics [17], struggles with trace-level detection [17] |

| X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) [24] | Emission of fluorescent X-rays when excited by X-ray source | Elemental analysis of metals [25], environmental monitoring, archaeological artifacts | Non-destructive, rapid analysis with no sample preparation [24], immediate results | Limited to elemental composition (not molecular structure), safety concerns with X-ray emissions [24] |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) [17] | Atomic emission spectroscopy from laser-induced plasma | Metallurgical analysis [17], mining [17], hazardous material detection | Rapid, in-situ elemental analysis without sample preparation [17] | Destructive on microscopic scale [17], complex spectral interpretation due to matrix effects [17] |

Table 2: Performance Characteristics in Drug Analysis Applications

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy [23] | NIR Spectroscopy [21] | FT-IR Spectroscopy [20] | Colorimetric Tests [20] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Few seconds to 1 minute [20] | ~5 seconds [20] | <1 minute [20] | 1-2 minutes |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (can scan through packaging) [23] | Minimal | Must be in contact with sample [20] | Extensive (mixing reagents) |

| Destructive | No [23] | No [20] | No [20] | Yes |

| Accuracy | High for single-component samples [20] | 91-99% for major drugs [21] | High for single-component samples [20] | Moderate (false positive issues) [20] |

| Quantification Capability | Limited in mixtures [20] | Excellent (±15% uncertainty) [21] | Good | No |

| Ideal Use Case | Verification of pure pharmaceuticals [19] | Quantification of drug purity [21] | Laboratory confirmation | Preliminary screening |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for Field Spectroscopy

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function | Application Example | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portable Raman Spectrometer [19] | Molecular fingerprinting through inelastic light scattering | Non-invasive verification of drug formulations through packaging [17] | Bruker BRAVO with SSETM technology, Laser Class 1 certified [19] |

| Handheld NIR Spectrometer [21] | Quantitative analysis of organic compounds via overtone vibrations | Quantification of illicit drug purity in field settings [21] | Viavi MicroNIR with NIRLAB infrastructure and chemometric models [21] |

| Handheld XRF Spectrometer [24] | Elemental composition analysis via X-ray fluorescence | Metal alloy verification in manufacturing quality control [24] | Terra Scientific EulerX900 with advanced algorithms for non-destructive testing [25] |

| Chemometric Modeling Software [21] | Multivariate analysis of spectral data for identification and quantification | Machine learning algorithms for drug identification and purity estimation [21] | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) algorithms [17] |

| Validation Standards [23] | Calibration and verification of spectrometer performance | Method validation against reference techniques like GC-MS [23] | Certified reference materials with known composition and purity |

Implementation Challenges and Solutions

Despite significant advances, handheld spectrometers face specific technical challenges that researchers must address for successful field deployment.

Key Challenges and Mitigation Strategies:

- Sensitivity and Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Reduced optical paths in miniaturized systems inherently limit signal-to-noise ratio compared to benchtop instruments [17]. Solution: Advanced signal processing algorithms and sequential shifted excitation (SSETM) technology improve performance for challenging materials [19].

- Spectral Resolution and Accuracy: Miniaturized diffraction gratings and optics typically offer lower resolution than laboratory systems [17]. Solution: Computational spectroscopy techniques that reconstruct high-quality spectral data from compressed measurements [22].

- Matrix Interference: Complex mixtures pose challenges for direct analysis, particularly with trace components [20]. Solution: Sample preparation techniques including solvent extraction to concentrate analytes like fentanyl from mixtures [20].

- Regulatory Compliance: In pharmaceutical applications, systems must comply with 21 CFR Part 11 for electronic records [19]. Solution: Dedicated validation modes that ensure data integrity and prevent unauthorized modification [19].

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

The convergence of miniaturization, connectivity, and consumer electronics continues to evolve, opening new frontiers in handheld spectroscopy:

- Wearable Spectroscopic Sensors: Integration of Raman, SERS, and NIR sensors into wearable formats for continuous, non-invasive monitoring of physiological biomarkers [16].

- Artificial Intelligence Integration: AI and machine learning are enhancing spectral interpretation and predictive analytics, enabling more accurate identification of complex mixtures [18].

- Multi-Technology Platforms: Hybrid systems combining complementary techniques (e.g., Raman + LIBS + XRF) in single devices to address a wider range of analytical challenges [16].

- Miniaturization Advancements: Research continues into even smaller spectrometers, including pixel-sized sensors that could be incorporated into consumer smartphones for ubiquitous chemical analysis [22].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advancements promise increasingly sophisticated analytical capabilities in field-deployable formats, potentially transforming field research paradigms across pharmaceutical development, forensic science, and environmental monitoring.

Market Growth and Adoption Trends in Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sectors

The global market for portable and handheld spectrometers is experiencing significant growth, driven by their increasing adoption in the biomedical and pharmaceutical sectors. These compact, powerful instruments are revolutionizing field analysis and on-site testing by enabling rapid, non-destructive material identification and verification.

Global Market Size and Projections

The following table summarizes the current market valuation and future growth projections for the portable spectrometer sector:

| Market Segment | 2024/2025 Market Value | 2032/2034 Projected Value | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mobile Spectrometers Market [26] | USD 1.47 Billion (2025) | USD 2.46 Billion (2034) | 7.7% | Miniaturization, real-time field analysis, pharmaceutical QA |

| Molecular Spectrometer for Pharma [27] | USD 336 Million (2025) | USD 502 Million (2032) | 6.9% | Drug development, regulatory compliance, quality control |

| Portable Spectrometer Market [28] | USD 2,202.30 Million (2024) | USD 4,472.52 Million (2032) | 9.30% | Chemical & pharmaceutical industry demand |

| Portable Handheld Spectrometer [29] | USD 1.2 Billion (2023) | USD 2.8 Billion (2032) | 9.5% | Advancements in technology, user-friendly tools |

Technology Segmentation and Adoption

Different spectroscopic technologies are being adapted into portable formats to serve specific applications within the biomedical and pharmaceutical fields. The table below outlines key technology types and their primary uses:

| Technology Type | Primary Applications in Biomed/Pharma | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectrometers [30] [31] [29] | Drug identity verification, raw material inspection, counterfeit detection | Non-destructive, requires minimal sample prep, can analyze through packaging |

| Handheld LIBS [29] | Elemental analysis | Rapid, non-destructive elemental analysis |

| Mass Spectrometers [28] | Drug purity analysis, molecular weight determination | High sensitivity, ability to differentiate isotopes |

| UV-Visible Spectrometers [27] [29] | Routine pharmaceutical analysis, colorimetric assays | Widespread adoption, cost-effective for specific applications |

| Infrared Spectrometers [29] | Chemical identification, environmental monitoring | Identifies functional groups, useful for organic compounds |

Key Drivers and Technological Advancements

Primary Growth Drivers

The expansion of the portable spectrometer market in biomedical and pharmaceutical sectors is propelled by several key factors:

Stringent Regulatory Requirements: The pharmaceutical industry relies on portable spectrometers for quality control and assurance to comply with rigorous regulatory standards from agencies like the FDA and EPA, as well as pharmacopeial standards such as European Pharmacopoeia and United States Pharmacopeia (USP) [28] [32]. These instruments enable rapid on-site analysis of raw materials, intermediates, and finished products, ensuring product integrity and patient safety [31].

R&D Acceleration and Drug Development: Increased global R&D expenditure across biotechnology, materials science, and nanotechnology is expanding the use of spectroscopy [32]. Molecular spectrometers are essential for studying drug composition, structure, and interactions during the development phase [27].

Need for On-Site, Real-Time Analysis: Portable handheld spectrometers transform business operations by allowing informed decisions at the point of need, moving the laboratory to the sample rather than bringing the sample to the laboratory [33]. This capability is crucial for applications ranging from pharmaceutical manufacturing to environmental monitoring [34].

Technological Innovations

Recent technological advancements are enhancing the capabilities and adoption of portable spectrometers:

AI and Machine Learning Integration: Enhancements in spectral interpretation, anomaly detection, and pattern recognition are being achieved through AI and machine learning [26] [32]. These technologies provide rapid decision-making tools and predictive analytics, improving accuracy and reducing dependency on operator expertise.

Miniaturization and Enhanced Portability: breakthroughs in miniaturization, MEMS, optics, and integrated sensors are making devices more compact, affordable, and efficient [26]. This has resulted in instruments that are significantly smaller than traditional laboratory models while maintaining high performance [33].

Connectivity and Data Management: Modern portable spectrometers feature smartphone integration, cloud-based data sharing, and wireless communications for real-time data analysis and collaborative research [26] [34]. This enables seamless data management and remote diagnostics.

Hybrid and Multi-Technology Systems: Combinations of different spectroscopic techniques in single devices (Raman-NIR, Raman-XRF) are emerging, providing more comprehensive analytical capabilities [33]. These hybrid systems offer users greater versatility and cost-effectiveness.

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Standard Experimental Workflow for Pharmaceutical Raw Material Verification

The identity verification of incoming raw materials is a critical application of handheld Raman spectrometers in pharmaceutical manufacturing. The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow:

Detailed Methodologies

Protocol 1: Raw Material Identity Testing using Handheld Raman Spectroscopy

Objective: To verify the identity of incoming pharmaceutical raw materials directly in the warehouse, ensuring they match the specified chemical compound before release for manufacturing [30] [31].

Materials and Equipment:

- Handheld Raman spectrometer (785 nm or 1064 nm excitation recommended to minimize fluorescence) [33]

- Reference spectral library of approved raw materials

- Optional: sample vial holder for consistent positioning

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Verify instrument calibration using manufacturer-supplied reference standard according to established procedures [28].

- Sample Presentation: Place the raw material in its original container (if glass or plastic) or in a suitable sample vial. For materials in transparent packaging, analysis can often be performed directly through the container [33].

- Spectral Acquisition: Position the handheld spectrometer probe firmly against the sample or container. Acquire spectrum with appropriate integration time (typically 1-10 seconds) and number of accumulations to achieve adequate signal-to-noise ratio.

- Spectral Matching: Process the acquired spectrum (baseline correction, smoothing) and compare against the reference spectral library using correlation algorithms or spectral angle mapping.

- Interpretation: A positive match (typically >95% similarity) confirms material identity. Failed matches trigger quarantine and additional investigation.

Advantages: Non-destructive analysis, minimal to no sample preparation, rapid results (typically <30 seconds), can be performed by trained warehouse personnel [31].

Protocol 2: Counterfeit Drug Detection using Handheld Spectrometers

Objective: To identify counterfeit or substandard pharmaceutical products in field settings such as customs checkpoints, pharmacy inspections, or supply chain verification [30] [31].

Materials and Equipment:

- Handheld Raman or NIR spectrometer

- Comprehensive drug spectral database including authentic products and common counterfeits

- Tablet/capsule holder for consistent positioning

Procedure:

- Database Preparation: Ensure the instrument contains a current database of authentic pharmaceutical products, including excipients and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

- Sample Analysis: For tablets, position the spectrometer probe directly against the tablet surface. For capsules, analysis can be performed through the capsule shell in many cases.

- Spectral Comparison: Compare the acquired spectrum to the reference spectrum of the authentic product.

- API Verification: Confirm the presence of the correct API at appropriate concentration levels.

- Excipient Screening: Check for correct excipient composition, as deviations may indicate counterfeit products.

- Result Documentation: Save spectra and results for regulatory purposes and further investigation if needed.

Advantages: Rapid screening (typically <60 seconds), non-destructive testing preserves evidence for legal proceedings, ability to detect wrong APIs, incorrect dosage, or absence of declared APIs [31].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of portable spectrometer applications in biomedical and pharmaceutical research requires specific reagents and materials. The following table details key solutions and their functions:

| Research Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates [30] | Enhance Raman signal sensitivity by up to 10⁷ times for trace analysis | Metallic nanoparticles (Au/Ag) on solid supports; enables detection of pesticide residues, drug metabolites |

| Calibration Standards [28] | Verify instrument performance and ensure regulatory compliance | Certified reference materials traceable to national standards; includes polystyrene for wavelength calibration |

| Spectral Library Databases [33] | Enable automated compound identification through spectral matching | Curated collections of reference spectra; often application-specific (pharmaceuticals, explosives, narcotics) |

| Portable Sample Accessories [34] | Facilitate consistent sampling for various material types | Include vial holders, powder cups, liquid cells; improve reproducibility in field analysis |

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The future of portable spectroscopy in biomedical and pharmaceutical sectors is shaped by several emerging trends:

AI-Powered Spectral Interpretation: Advanced algorithms are enhancing spectral interpretation, enabling faster and more accurate identification of complex mixtures and subtle anomalies [26] [32]. This reduces dependency on operator expertise and enables predictive maintenance and anomaly detection in pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Hyphenated and Multi-Technology Systems: Integration of multiple spectroscopic techniques in single devices (Raman-FTIR, Raman-NIR, Raman-XRF) provides more comprehensive analytical capabilities [33]. These hybrid systems offer users greater versatility and cost-effectiveness by reducing the need for multiple specialized instruments.

Expansion of 'Citizen Science' and Decentralized Testing: The miniaturization and simplification of spectroscopic devices are enabling new applications in citizen science and point-of-care testing [33]. Research organizations can equip members of the public with accessories and software for their phones, coordinating large-scale studies.

Advanced Data Management and Cloud Integration: Cloud-based spectral data processing supports centralized monitoring, scalability, and collaborative research across geographies [32]. This enables real-time data sharing between field operators and central laboratories, enhancing decision-making speed.

Despite the promising outlook, the market faces challenges including high initial acquisition costs for advanced systems, the need for skilled operators despite improvements in usability, and ongoing issues with library development and maintenance for diverse applications [28] [35]. Additionally, environmental limitations in extreme field conditions and competition from established laboratory instruments for highly specialized applications remain considerations for future development [35].

From Theory to Practice: Field Applications in Drug Development and Analysis

Pharmaceutical Raw Material Identification (RMID) on the Loading Dock

The identification and verification of raw materials (RMID) at the loading dock represents a critical control point in pharmaceutical manufacturing, ensuring that incoming ingredients meet specifications before entering production. Traditional methods, which involve collecting samples for laboratory analysis, are time-consuming, create quarantine backlogs, and increase the risk of contamination and human error. The integration of handheld Raman spectrometers is transforming this process, enabling non-destructive, on-the-spot analysis that aligns with the broader trend of moving analytical capabilities from the central laboratory directly into the field. This shift, driven by advancements in spectroscopic technology and miniaturization, supports real-time decision-making, significantly accelerates material release, and enhances overall supply chain integrity [36] [37].

This technical guide details the implementation of handheld Raman spectroscopy for RMID in a cGMP environment. It provides researchers and scientists with a comprehensive framework covering operational principles, validated methodologies, and practical protocols for deploying this technology to achieve laboratory-quality results at the point of receipt.

Handheld Raman Technology: Core Principles and Advantages

Raman spectroscopy is a molecular spectroscopic technique that relies on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser. When light interacts with a molecular sample, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering), but a tiny fraction undergoes a shift in energy corresponding to the vibrational modes of the molecules present. This creates a unique "fingerprint" spectrum, allowing for definitive identification of chemical compounds [37].

Key Advantages for Loading Dock RMID:

- Non-Destructive and Non-Invasive: Samples can be analyzed through transparent or translucent packaging, such as plastic bags and glass vials, eliminating the need for opening containers and reducing exposure risks and sampling errors [38] [39].

- Rapid Analysis: Identification is typically achieved in 5-30 seconds, allowing for 100% verification of incoming lots directly at the point of receipt [39] [37].

- Minimal Sample Preparation: No grinding, pressing, or other preparation is required, streamlining the workflow for non-expert operators [38] [37].

- Portability and Ruggedness: Handheld devices are battery-operated, weigh under 2 kg, and are often built to IP65 or similar standards for durability in industrial environments like loading docks [37].

A critical technical consideration is laser wavelength. While 785 nm lasers are standard for many organics, the 1064 nm wavelength is particularly advantageous for analyzing colored materials or substances prone to fluorescence, as it minimizes these interfering effects. Modern handheld systems leverage Orbital Raster Scanning (ORS) to move the laser beam across the sample, improving signal quality and reducing the risk of localized sample heating [38] [37].

Experimental Protocol for RMID Method Development and Validation

Implementing a handheld Raman method for RMID requires a structured approach to ensure reliability and regulatory compliance. The following protocol outlines the key stages from initial setup to routine use.

Method Development and Library Building

The foundation of a successful RMID system is a robust spectral library.

- Step 1: Sample Collection and Preparation. Acquire a minimum of 3-5 independent lots of each raw material from qualified suppliers to account for natural variability (e.g., in particle size, crystalline form). For through-container analysis, collect spectra of the material inside its authentic, unopened primary packaging [40].

- Step 2: Data Acquisition. Using the handheld Raman spectrometer, collect a sufficient number of spectra (e.g., 10-20 scans per lot) from different spots on the container to ensure representativeness. The instrument's software will typically average these scans to create a stable, representative reference spectrum for each material [40].

- Step 3: Library Entry Creation. For each raw material, the averaged spectrum is saved in the instrument's library and linked to the material's unique identifier (e.g., material name, CAS number). The system then uses algorithms to define the spectral limits for a "Pass" result [37].

Method Validation

Before implementation, the method must be validated to demonstrate its reliability. Key performance characteristics include:

- Specificity: The method must unequivocally distinguish between the target material and common contaminants or look-alike materials (e.g., starch vs. maltodextrin). It should not produce a "Pass" for an incorrect material [40].

- Robustness: Test the method under varied but realistic conditions, such as slightly different focus distances, operator techniques, or ambient temperature fluctuations, to ensure consistent performance [40].

- System Suitability: Perform daily checks using a known reference standard to verify the instrument is functioning within its specified parameters before testing unknown materials [37].

Routine Operation on the Loading Dock

The following workflow diagram illustrates the optimized process for raw material testing on the loading dock.

Essential Technical Specifications and Research Toolkit

Selecting the appropriate handheld Raman spectrometer and supporting materials is crucial for success. The following tables summarize key considerations and essential components for establishing an RMID program.

Table 1: Key Specifications for Handheld Raman Spectrometers in Pharmaceutical RMID

| Feature | Recommendation for RMID | Rationale and Research Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Wavelength | 1064 nm is preferred for broadest application | Reduces fluorescence from colored containers or impurities; essential for analyzing materials in brown paper sacks [38] [41]. |

| Spectral Range | 200-3200 cm⁻¹ | Covers the "fingerprint region" where most molecular vibrations occur, ensuring unique identification [37]. |

| Spectral Library | Customizable, with 20,000+ compound capacity | Must allow creation of a site-specific library with multiple lots; pre-loaded libraries aid initial setup [37]. |

| Regulatory Compliance | 21 CFR Part 11, USP, GMP | Ensures data integrity, traceability, and electronic signature support for use in regulated environments [39] [37]. |

| Connectivity | Wi-Fi, Bluetooth | Enables real-time data transfer to centralized databases/LIMS and remote oversight [37]. |

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit for RMID on the Loading Dock

| Item or Solution | Function in the RMID Process |

|---|---|

| Handheld Raman Spectrometer | The core analytical device for non-destructive, through-container spectral acquisition [38] [39] [37]. |

| Validated Spectral Library | A customized digital collection of reference spectra for all raw materials; the benchmark for all identity verifications [37] [40]. |

| System Suitability Standard | A stable, known chemical standard (e.g., acetaminophen) used daily to confirm instrument performance is within specified limits [37]. |

| Robust Method (SOP) | A detailed, step-by-step procedure defining the entire process from sample presentation and scan parameters to result interpretation [40]. |

| IQ/OQ/PQ Documentation | Installation, Operational, and Performance Qualification documents proving the instrument is installed correctly, operates as intended, and performs suitably for its specific RMID applications [39] [37]. |

Quantitative Impact and Market Validation

The adoption of handheld Raman spectroscopy for field-based RMID is supported by strong market data and documented operational benefits. The technology not only improves quality control but also delivers significant economic advantages by streamlining logistics.

Table 3: Market and Performance Data for Handheld Spectrometers

| Metric | Data | Context and Source |

|---|---|---|

| Global Mobile Spectrometers Market (2025) | USD 1.47 Billion | Projected to grow at a CAGR of 7.7% to USD 2.46 billion by 2034, indicating rapid adoption [26]. |

| Global Portable Handheld Spectrometer Market (2025) | USD 1.5 Billion (est.) | Driven by demand for rapid, on-site analysis across multiple industries [35]. |

| Time Savings in Material Release | Up to 50% faster | Agilent reports moving materials from "pallet to production" 50% faster using their Vaya spectrometer [41]. |

| Analysis Speed | 5-20 seconds per sample | Enables high-throughput verification on the loading dock, as demonstrated by TSI's ASSURx and others [39] [37]. |

| Material Coverage | Organics, powders, liquids, aqueous solutions | Raman is versatile and can handle a wide range of sample types, unlike older NIR techniques [39]. |

The following diagram synthesizes the technical, operational, and strategic factors that underpin the successful deployment of this technology, illustrating the logical pathway from implementation to ultimate benefit.

The deployment of handheld Raman spectrometers for raw material identification on the loading dock is a definitive advancement in pharmaceutical quality control. This guide has detailed the technical principles, validated experimental protocols, and essential tools required to transfer this analytical capability from the laboratory to the field. By enabling non-destructive, rapid, and definitive identification of materials through their primary packaging, this technology directly addresses key industry challenges: reducing quarantine times, minimizing operational costs, and mitigating risks of contamination and counterfeiting [39] [41].

For researchers and scientists, this shift is not merely a matter of convenience but a strategic evolution. It embodies the broader trend of field-based analysis, where real-time data drives smarter, faster, and more secure manufacturing decisions. As the market data and technical specifications confirm, handheld Raman spectroscopy has matured into a robust, compliant, and indispensable technology for the modern pharmaceutical supply chain, ensuring that product quality is built in from the very first step.

Rapid Detection of Counterfeit and Adulterated Pharmaceuticals

The global fight against substandard and falsified (SF) medicines represents a significant public health challenge, with approximately 10% of medical products in low- and middle-income countries being substandard or falsified [42]. These poor-quality pharmaceuticals lead to increased morbidity and mortality, adverse drug reactions, economic losses, and diminished public confidence in health systems. The deployment of handheld spectroscopic devices has emerged as a transformative strategy for rapid, on-site screening of pharmaceutical quality, enabling interventions at various points in the supply chain without the delays associated with laboratory testing.

Traditional methods for medicine quality control, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), while highly accurate, are time-consuming, expensive, and require complex laboratory infrastructure [43] [42]. This creates significant bottlenecks, especially when regulatory agencies need to screen large numbers of samples. Handheld spectrometers address these limitations by bringing analytical capabilities directly to the field, offering non-destructive, rapid analysis with minimal sample preparation [44].

This technical guide examines the principles, performance, and application of handheld spectroscopy within a broader research context, focusing on their operational parameters, methodological considerations, and integration into comprehensive quality assurance frameworks for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Technologies and Their Operational Principles

Handheld Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy operates on the principle of inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source. When light interacts with a molecule, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering), but a small fraction undergoes frequency shifts corresponding to the vibrational modes of the molecular bonds, creating a unique spectral "fingerprint" [44].

Modern handheld Raman instruments, such as the NanoRam and TruScan, incorporate 785 nm excitation lasers with thermoelectrically-cooled CCD detectors to enhance signal stability and reduce background noise [44] [45]. Key advantages include:

- Non-contact analysis through transparent packaging

- Minimal sample preparation requirements

- High molecular selectivity for unambiguous compound identification [44]

A significant challenge in Raman analysis is sample auto-fluorescence, which can overwhelm the Raman signal. Advanced instruments employ algorithmic corrections and hardware innovations such as shifted-excitation Raman difference spectroscopy (SERS) to mitigate these effects [44] [45].

Handheld Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy

NIR spectroscopy measures overtone and combination vibrations of molecular bonds, particularly C-H, O-H, and N-H, when samples are irradiated with light in the 780-2500 nm range [46]. Unlike Raman, NIR is an absorption technique that probes different molecular interactions.

The SCiO device exemplifies modern NIR technology, operating as a diffuse reflectance NIR spectrometer with an optical integrating attachment similar to an integrating sphere [43]. Benefits of NIR include:

- Deeper sample penetration compared to Raman

- Reduced fluorescence issues

- Lower cost compared to Raman systems [43]

NIR spectra typically exhibit broad, overlapping bands that require advanced chemometric processing for meaningful interpretation, making robust statistical models essential for effective deployment [46].

Emerging Technological Innovations

Recent advancements focus on overcoming traditional limitations. Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS) enables analysis through opaque, non-transparent containers by collecting scattered light at a distance from the illumination point, effectively probing subsurface layers [45]. This capability is particularly valuable for analyzing pharmaceuticals in blister packs or colored bottles.

Multi-technique integration combines complementary approaches; for instance, one study demonstrated that a low-cost NIR sensor providing a short wavelength NIR range (swNIR) and a classical handheld NIR spectrometer (cNIR) could achieve 96.0% and 91.1% correct identification in validation, respectively, when paired with optimized classification algorithms [46].

Performance Evaluation and Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The evaluation of handheld spectrometers requires careful assessment of multiple performance parameters. Sensitivity and specificity vary significantly based on instrument design, sample composition, and analytical methodology.

Table 1: Detection Capabilities of Handheld Spectrometers for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Device Type | Detection Capability | Limit of Detection | Analysis Time | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Handheld Raman (TruNarc) | Cocaine in mixtures with common cutting agents [47] | 10-40 wt% (dependent on sample composition) [47] | < 20 seconds [44] | Narcotics identification, raw material verification [44] [47] |

| Handheld NIR (SCiO) | Falsified artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) [43] | Successful identification of falsified samples; substandard artesunate detection [43] | Rapid screening (specific time not provided) | Antimalarial screening, supply chain monitoring [43] |

| Handheld Raman with SORS (Resolve) | Ibuprofen through opaque polypropylene container [45] | Quantitative through opaque packaging with ±15% acceptance limits [45] | Varies with configuration | Analysis through opaque packaging, quantitative API assessment [45] |

Field Performance and Validation Studies

Independent field evaluations provide critical data on real-world performance. A systematic review identified 41 portable devices for medicine quality screening, but only six had undergone field testing, highlighting a significant evidence gap [42]. Key findings from field evaluations include:

- Raman devices demonstrated a 97.5% true positive rate for cocaine detection in 3,168 case samples compared to GC-MS analysis, with no false positives reported [47].

- NIR spectrometers successfully identified falsified medicines in all cases where reference spectra of genuine products were available, though detection of substandard APIs was more variable [43].

- Methodology robustness depends heavily on comprehensive spectral libraries and calibration models; one study achieved 100% counterfeit detection by creating a database containing almost all tablets produced by a pharmaceutical firm [46].

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Handheld Spectroscopy Technologies

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy | Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Mechanism | Laser-induced inelastic scattering [44] | Absorption of NIR radiation [46] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; can analyze through transparent packaging [44] | Minimal; can analyze through some packaging [43] |

| Spectral Information | Well-resolved, sharp peaks for specific molecular identification [44] | Broad, overlapping bands requiring chemometrics [46] |

| Fluorescence Interference | Significant challenge for some compounds [44] | Less susceptible to fluorescence [46] |

| Quantitative Capability | Possible with appropriate models [45] | Possible with robust calibration models [46] |

| Cost Factor | Higher (approximately USD 17,000-50,000) [43] | Lower (approximately USD 1,000-250 for SCiO) [43] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Testing Procedure for Raw Material Identification

A validated protocol for pharmaceutical raw material identification using handheld Raman spectroscopy involves systematic methodology development and verification [44]:

Instrument Calibration: Begin with calibration using certified reference standards of target compounds to establish baseline spectral signatures.

Method Development: For each material, develop a specific "method" by collecting a minimum of 20 scans. This incorporates variations in sampling position, packaging materials, and batch-to-batch differences to ensure method robustness.

Spectral Analysis: Process acquired spectra using proprietary algorithms that compare unknown spectra against reference libraries, generating a numerical P-value (where 1.000 represents a perfect fit) for PASS/FAIL determination [44].

Result Interpretation: Samples yielding P-values above a predetermined threshold (e.g., >0.95) are confirmed as authentic, while failures trigger additional analysis using Hit Quality Index (HQI) matching against broader spectral libraries.

This methodology has proven effective for differentiating between visually similar pharmaceutical excipients such as various cellulose materials (e.g., microcrystalline cellulose, HPMC compounds) and food additives like lactose and maltodextrin [44].

Counterfeit Detection Protocol for Finished Dosage Forms

A comprehensive approach to counterfeit tablet detection using handheld NIR spectrometers involves [46]:

Reference Database Creation: Compile extensive spectral libraries from authentic products, measuring 5 independent batches per formulation with 3-5 tablets per batch and 10 spectra per tablet to capture normal manufacturing variability.

Chemometric Model Development: Implement supervised classification methods such as Support Vector Machine (SVM) for short-wavelength NIR or Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) for classical NIR range data.

Model Validation: Challenge optimized models with known counterfeit samples to verify detection capability, utilizing "One vs Rest" classification approaches that compare questioned samples against all genuine products in the database.

Field Deployment: For suspect samples, collect triplicate spectra and process through validated models, with results including correlation distances and class assignment probabilities to support decision-making.

This protocol successfully identified 100% of counterfeits in a study involving 29 pharmaceutical product families comprising 53 different formulations [46].

Quantitative Analysis Through Packaging

For quantitative assessment of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) through packaging, a validated methodology includes [45]:

Sample Presentation: Analyze samples directly through glass vials or with additional opaque packaging (e.g., glass vial placed inside polypropylene container).

Spectrum Acquisition: Acquire spectra using both conventional backscattering and spatially offset Raman spectroscopy (SORS) configurations where available.

Multivariate Modeling: Develop Partial Least Squares Regression (PLS-R) models using API-specific calibration curves with concentration ranges covering expected values (e.g., 24-52% w/w for ibuprofen in ternary mixtures).

Validation: Assess model performance using accuracy profiles with ±15% acceptance limits, following ICH Q2(R1) guidelines to ensure adequate quantitative performance for intended use.

This approach has demonstrated that while conventional handheld Raman devices can quantify APIs through transparent packaging, only SORS-enabled instruments achieve acceptable accuracy through opaque containers [45].

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Workflow for handheld spectrometer analysis of pharmaceuticals

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Handheld Spectrometer Research

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Provide authenticated spectral signatures for method development and calibration [44] | Creating reference libraries for pharmaceutical raw materials (e.g., cellulose, HPMC) [44] |

| Validation Sets with Known API Content | Enable performance assessment of quantitative methods against reference standards [45] | Testing PLS-R models for ibuprofen quantification in ternary mixtures [45] |

| Common Pharmaceutical Excipients | Assess selectivity and potential interference in API detection [44] [45] | Differentiating between similar compounds (e.g., cellulose vs. microcrystalline cellulose) [44] |

| Binary Mixtures with Cutting Agents | Determine detection limits in complex matrices [47] | Establishing LOD for cocaine in mixtures with levamisole, paracetamol, etc. [47] |

| Packaging Materials | Evaluate analytical capability through various barriers [45] | Testing SORS performance through opaque polypropylene containers [45] |

| Chemometric Software | Process spectral data, build classification models, and perform statistical analysis [46] | Implementing SVM or LDA models for tablet authentication [46] |

Handheld spectroscopy represents a rapidly advancing field that significantly enhances capabilities for detecting counterfeit and adulterated pharmaceuticals. The integration of these technologies into supply chain monitoring provides a powerful approach to combating the global challenge of poor-quality medicines.

Future developments will likely focus on improved sensitivity for API quantification, expanded spectral libraries covering more pharmaceutical products, enhanced data sharing capabilities between devices, and reduced costs for wider deployment. Additionally, standardization of testing protocols and validation criteria will be essential for regulatory acceptance and comparative performance assessment.

For researchers and drug development professionals, handheld spectrometers offer not only practical screening tools but also platforms for methodological innovation through advanced signal processing and machine learning approaches. As these technologies continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly vital role in global pharmaceutical quality assurance systems.

On-Site Analysis of Complex Mixtures and Trace Components (e.g., Fentanyl)

The potent synthetic opioid fentanyl, and its analogues, represent a significant public health and security threat due to extreme potency, with a lethal dose for an average adult estimated to be as low as 2 milligrams [48]. The presence of trace amounts of fentanyl in illicit drug supplies, often unbeknownst to the user, has been a major driver of the opioid overdose crisis [48]. This reality underscores a critical analytical challenge: the reliable detection and identification of a highly potent trace component within a complex and variable chemical mixture in a field setting.