HPLC Separation Fundamentals: From Core Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

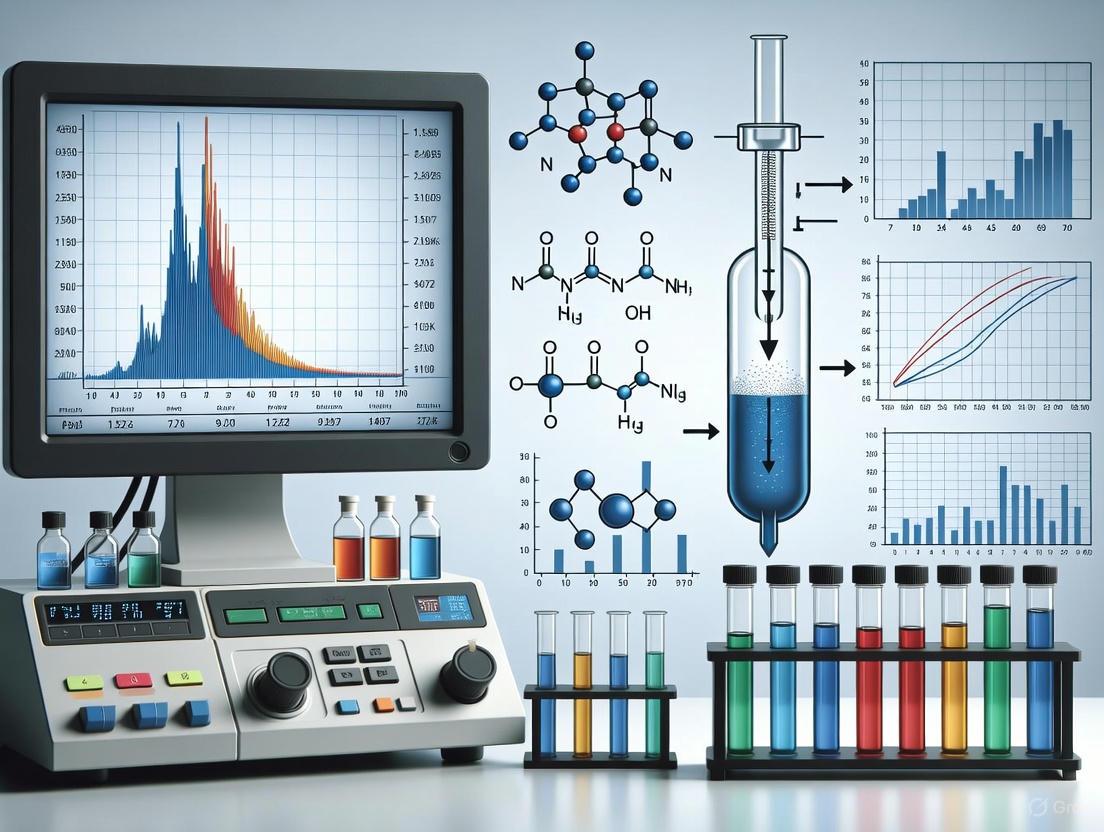

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the fundamental principles of chromatographic separation in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

HPLC Separation Fundamentals: From Core Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the fundamental principles of chromatographic separation in High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It bridges the gap between foundational theory and cutting-edge practice, covering the thermodynamic and kinetic basis of separation, modern method development aided by artificial intelligence, systematic troubleshooting for reliable results, and rigorous validation for pharmaceutical quality control. By synthesizing established knowledge with emerging trends, this guide serves as a valuable resource for enhancing analytical precision, efficiency, and innovation in biomedical research.

Core Principles: The Thermodynamic and Kinetic Basis of HPLC Separation

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is a powerful analytical technique used to separate, identify, and quantify components in a mixture. This separation occurs through a sophisticated interplay between two fundamental elements: the mobile phase and the stationary phase [1] [2]. The mobile phase, a pressure-driven liquid solvent, transports the sample through the system. The stationary phase, a solid material packed within a column, interacts with the sample components to retard their movement [1]. The core principle of HPLC rests on the differential distribution of analytes between these two phases. Compounds possessing varying affinities for the stationary and mobile phases will elute at different times, resulting in the physical separation essential for analysis [2]. A deep understanding of the characteristics and interactions of these two phases is not merely foundational; it is the critical factor in developing robust, efficient, and reproducible chromatographic methods for pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Characteristics of Mobile and Stationary Phases

Mobile Phase Characteristics

The mobile phase is not merely a transport medium; its properties directly govern analyte retention and selectivity. Key characteristics include [2]:

- Polarity: The polarity of the mobile phase must be considered relative to the stationary phase and the analytes. In reversed-phase chromatography (the most common mode), a polar mobile phase (e.g., water mixed with methanol or acetonitrile) is used with a non-polar stationary phase [2].

- Composition: Mobile phases can be a single solvent or, more commonly, a mixture. The use of solvents like water/acetonitrile or water/methanol provides greater flexibility and control over separation [2].

- pH and Buffer Capacity: For ionizable compounds, the pH of the mobile phase is critical. It can dramatically affect the analyte's charge state and thus its interaction with the stationary phase. Buffers (e.g., phosphate, acetate) are added to maintain a stable pH, which is essential for achieving consistent retention times and peak shape [2].

- Flow Rate: The rate at which the mobile phase is pumped through the column impacts separation efficiency and time. Higher flow rates reduce analysis time but may compromise resolution, whereas lower flow rates generally increase resolution at the cost of longer run times [2].

- Additives: Minor components, such as ion-pairing agents or salts, can be added in low millimolar concentrations to compete with solutes for adsorption sites or form complexes, offering precise control over selectivity and peak shape for challenging separations [3].

Stationary Phase Characteristics

The stationary phase is the heart of the chromatographic column, where the physical separation of analytes occurs. Its properties are equally vital [2]:

- Polarity and Chemistry: The chemical nature of the stationary phase determines the primary retention mechanism. Polar phases (e.g., bare silica) are used in normal-phase chromatography, while non-polar phases (e.g., C18-bonded silica) are standard for reversed-phase chromatography [2].

- Surface Area: A higher surface area provides more interaction sites, which generally improves separation resolution, particularly for complex mixtures [2].

- Particle Size: Smaller particles (e.g., 1.7-5 µm) offer higher efficiency and resolution but significantly increase system backpressure. This relationship is a key driver behind the development of UHPLC, which uses sub-2µm particles and higher pressure pumps [1] [2].

- Pore Size: The pore size determines analyte accessibility. Smaller pores (60-120 Ã…) are ideal for small molecules, while larger pores (>300 Ã…) are necessary for large biomolecules like proteins [2].

- Chemical Stability: The stationary phase must withstand operational conditions, including pH extremes and organic solvents. While silica-based phases are common, polymer-based phases are often chosen for their robustness under extreme pH conditions [2].

Table 1: Common Stationary Phase Types and Their Applications

| Stationary Phase Type | Common Functional Groups | Separation Mode | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase | C18 (Octadecyl), C8 (Octyl), Phenyl | Partitioning | Non-polar to moderately polar small molecules (e.g., drug compounds, metabolites) [2] |

| Normal-Phase | Silica, Diol, Amino, Cyano | Adsorption | Polar compounds, isomers, natural products [2] |

| Ion-Exchange | Sulfonic Acid (Cation), Quaternary Ammonium (Anion) | Ion-Exchange | Charged molecules like proteins, peptides, amino acids [2] |

| Size-Exclusion | Porous Silica or Polymer | Size-Exclusion | Biomolecules (proteins, polymers) separated by hydrodynamic volume [2] |

| Chiral | Various Protein-based or Synthetic Selectors | Enantioselective | Separation of enantiomers, critical in pharmaceutical development [3] |

Fundamental Interaction Mechanisms

The separation in HPLC is achieved because different analytes have varying distribution coefficients between the mobile and stationary phases. The primary interaction mechanisms include [2] [4]:

- Hydrophobic Interactions: The dominant mechanism in reversed-phase HPLC. Non-polar analyte molecules preferentially associate with the non-hydrocarbon ligands (e.g., C18) of the stationary phase, while the polar mobile phase promotes elution.

- Polar Interactions: Key in normal-phase HPLC. Polar functional groups on the analyte (e.g., -OH, -NHâ‚‚) interact with polar sites on the stationary phase (e.g., silanol groups on silica).

- Ionic Interactions: Utilized in ion-exchange chromatography. Charged analytes are attracted to oppositely charged functional groups on the stationary phase. Retention can be controlled by adjusting the mobile phase pH and ionic strength.

- Steric and Size-Based Interactions: The basis of size-exclusion chromatography, where molecules are sorted by their size as they diffuse through the pores of the stationary phase. Larger molecules elute first as they cannot enter the pores.

- Enantioselective Interactions: As explored in fundamental research, chiral stationary phases contain selectors that differentially interact with the three-dimensional structure of enantiomers. Torgny Fornstedt's work highlights that these phases are often heterogeneous, consisting of a few strong, chiral-discriminating sites and many weak, non-selective sites, which can be modeled using bi-Langmuir isotherms [3].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how these interactions lead to the separation of a sample mixture.

Quantitative Descriptors of Chromatographic Performance

The success of the chromatographic process is evaluated using key performance parameters derived from the interaction of the analyte with the mobile and stationary phases. These quantitative descriptors are crucial for method development and validation [1].

Table 2: Key Chromatographic Parameters and Their Definitions

| Parameter | Definition | Influence from Phases |

|---|---|---|

| Retention Time (táµ£) | The time elapsed between sample injection and the maximum peak signal of the analyte [1]. | Determined by the strength of analyte interaction with the stationary phase and the eluting strength of the mobile phase. |

| Efficiency (N) | The number of theoretical plates, a measure of peak broadening [1]. | Influenced by stationary phase particle size and packing quality, as well as mobile phase flow rate and viscosity. |

| Resolution (Râ‚›) | The ability to distinguish between two adjacent peaks [1]. | A combined effect of efficiency, retention, and selectivity; directly controlled by mobile phase composition and stationary phase chemistry. |

| Selectivity (α) | The ability to separate two analytes, calculated as the ratio of their capacity factors [1]. | Primarily governed by the chemical nature of the stationary phase and the composition/pH of the mobile phase. |

| Capacity Factor (k') | A measure of how long an analyte is retained on the column relative to an unretained molecule. | Directly reflects the equilibrium distribution of the analyte between the mobile and stationary phases. |

Advanced Fundamental Concepts

Adsorption Isotherms and Surface Heterogeneity

Under the analytical conditions typical of drug quantification (linear conditions), peak broadening is primarily kinetically controlled. However, a fundamental understanding of nonlinear (preparative) conditions is vital for purification processes and reveals the true nature of the stationary phase surface. In these conditions, thermodynamic factors, specifically the adsorption isotherm, govern peak shape and retention [3].

Groundbreaking work by scientists like Torgny Fornstedt has demonstrated that chiral stationary phases, particularly protein-based ones, are not homogeneous. They consist of a multitude of weak, non-selective adsorption sites and only a few strong, chiral-discriminating sites [3]. This surface heterogeneity can be modeled using the bi-Langmuir isotherm, which accounts for two distinct site types:

- Type I Sites: Non-selective, high-capacity, responsible for general retention.

- Type II Sites: Selective, low-capacity, essential for enantio-recognition [3].

This heterogeneity explains phenomena like peak tailing and the loss of enantioselectivity at higher sample concentrations, as the selective sites become saturated [3]. The Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) is a powerful tool that extends beyond simple models, providing a detailed energetic "fingerprint" of the chromatographic surface by revealing the full spectrum of binding strengths present [3].

Distinguishing Kinetic and Thermodynamic Tailing

Peak tailing is a common practical issue that can originate from different fundamental sources. Simple tests can distinguish the underlying cause [3]:

- Kinetic Tailing: If tailing decreases when a lower flow rate is used, the origin is kinetic, often due to slow mass transfer or slow adsorption/desorption kinetics on some sites.

- Thermodynamic Tailing: If tailing decreases when a lower sample concentration is injected, the cause is thermodynamic, typically resulting from heterogeneous adsorption (e.g., the bi-Langmuir model) [3].

Experimental Protocols for Fundamental Studies

Protocol for Determining Adsorption Isotherms

Objective: To characterize the equilibrium distribution of an analyte between the mobile and stationary phase under nonlinear conditions, revealing surface heterogeneity [3].

Materials:

- HPLC system with pump, injector, and detector (e.g., UV/VIS).

- Analytical column with the stationary phase under investigation.

- Mobile phase components (HPLC grade).

- Standard of the target analyte.

Method:

- Isocratic Elution at High Concentrations: Prepare a series of analyte solutions at increasing concentrations, spanning from the analytical (dilute) range to the overloaded concentration range.

- Chromatographic Runs: Inject each solution using an isocratic mobile phase composition. Precisely record the resulting elution profiles (peak shapes).

- Inverse Method: Use the recorded elution profiles to calculate the adsorption isotherm. This involves finding the isotherm function which, when used in the chromatographic model, best simulates the experimental overloaded peaks.

- Model Fitting: Fit the experimental data to different adsorption models (e.g., Langmuir, bi-Langmuir, Tóth). Statistical tests (e.g., Fisher analysis) can help identify the most appropriate model [3].

Workflow for Model Identification: A structured four-step workflow can be employed to identify the correct physical adsorption model [3]:

- Visual Classification: Examine the shape of the isotherm (linear, convex, or concave).

- Scatchard Analysis: Plot the data to explore interaction patterns; a linear plot suggests a Langmuir model, while curvature suggests heterogeneity.

- AED Calculation: Compute the Adsorption Energy Distribution to visualize the number and nature of adsorption sites, distinguishing unimodal from bimodal distributions.

- Model Testing: Perform final model fitting and statistical testing to confirm the best fit.

Protocol for Investigating Mobile Phase Additive Effects

Objective: To systematically evaluate the effect of a mobile phase additive (e.g., an ion-pairing reagent) on the retention and peak shape of an ionic analyte.

Materials:

- HPLC system with a compatible column (e.g., C18).

- Mobile phase components: Water, organic modifier (acetonitrile), additive (e.g., alkyl sulfonate for ion-pairing).

- Ionic analyte standard.

Method:

- Baseline Establishment: Develop a preliminary gradient or isocratic method without the additive to establish a baseline retention for the analyte.

- Additive Screening: Prepare a series of mobile phases with a constant organic modifier percentage but varying concentrations of the additive (e.g., 5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM).

- Analysis: Inject the analyte standard with each mobile phase composition and record the retention time, peak symmetry, and efficiency (theoretical plates).

- Data Analysis: Plot the retention factor (k') against the additive concentration. A linear increase suggests a dynamic ion-pairing mechanism where the additive competes for adsorption sites and modifies the stationary phase's properties [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HPLC Research and Method Development

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| C18 (Octadecyl) Column | The workhorse reversed-phase stationary phase for separating non-polar to moderately polar molecules [2]. |

| Silica (Normal-Phase) Column | Polar stationary phase for separating polar compounds or isomers, often used with non-aorganic mobile phases [2]. |

| Chiral Selector Column | Specialized stationary phase (e.g., protein-based, polysaccharide-based) for resolving enantiomers, a critical task in pharmaceutical analysis [3]. |

| HPLC-Grade Water & Organic Solvents (Acetonitrile, Methanol) | The primary components of the mobile phase; high purity is essential to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Potassium Phosphate, Ammonium Acetate) | Used to prepare buffered mobile phases to control pH for the analysis of ionizable compounds [2]. |

| Ion-Pairing Reagents (e.g., TFA, Alkyl Sulfonates) | Additives that interact with ionic analytes and the stationary phase to improve the retention and peak shape of charged molecules [3] [2]. |

| Guard Column | A short column placed before the analytical column containing the same phase, to protect the expensive analytical column from particulate matter and contaminants that could irreversibly bind to it [4]. |

| 2-Isopropoxypyridine | 2-Isopropoxypyridine, CAS:16096-13-2, MF:C8H11NO, MW:137.18 g/mol |

| 2-Methoxy-3-methylaniline | 2-Methoxy-3-methylaniline, CAS:18102-30-2, MF:C8H11NO, MW:137.18 g/mol |

In the realm of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) research, a profound understanding of adsorption thermodynamics is paramount for achieving efficient separations, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where high purity and yield are critical. The adsorption isotherm, which describes the equilibrium distribution of solute molecules between the mobile and stationary phases, lies at the heart of chromatographic process design and optimization. For decades, the Langmuir adsorption model has served as the fundamental theoretical framework for describing monolayer adsorption onto homogeneous surfaces. Its mathematical simplicity and physical intuitiveness have made it ubiquitous in chromatographic science. However, the inherent limitations of this classical model when confronted with chemically heterogeneous surfaces, commonly encountered in practical HPLC stationary phases, have driven the development of more sophisticated models such as the bi-Langmuir isotherm [5] [6].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the evolution from the classical Langmuir model to advanced bi-Langmuir approaches for characterizing complex surfaces. Within the context of chromatographic separation fundamentals, we will explore the theoretical underpinnings, mathematical formulations, and practical applications of these models, providing drug development professionals with the knowledge necessary to select and apply the appropriate adsorption model for their specific separation challenges.

Theoretical Foundations of Adsorption Models

The Langmuir Adsorption Model: Core Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Langmuir adsorption model, introduced by Irving Langmuir in 1916, explains adsorption by assuming an adsorbate behaves as an ideal gas at isothermal conditions and postulates that adsorption and desorption are reversible processes [7]. The model is built upon several fundamental assumptions that define its application scope. It presumes a perfectly flat surface with energetically equivalent adsorption sites, monolayer coverage where each site can hold at most one molecule, and no interactions between adsorbed molecules on adjacent sites [7] [8].

The mathematical formulation of the Langmuir isotherm can be derived through kinetic, thermodynamic, or statistical mechanical approaches. The kinetic derivation provides particular insight into the adsorption process. It considers the rate of adsorption (rad) and desorption (rd) as elementary processes:

- rad = kad p_A [S] (rate of adsorption proportional to partial pressure and free site concentration)

- rd = kd [A_ad] (rate of desorption proportional to occupied site concentration)

At equilibrium, where the rate of adsorption equals the rate of desorption, these relationships yield the familiar Langmuir isotherm equation [7]:

θA = (Keq^A pA) / (1 + Keq^A p_A)

Where θA represents the fractional surface coverage, pA is the partial pressure of the adsorbate, and Keq^A is the equilibrium constant for the adsorption process (the ratio kad/k_d) [7]. In liquid chromatography, this is often expressed in terms of concentration:

q = (q_s b c) / (1 + b c)

Where q is the adsorbed phase concentration, q_s is the saturation capacity (monolayer coverage), c is the liquid-phase concentration, and b is the adsorption equilibrium constant [6].

The Bi-Langmuir Model: Extending to Surface Heterogeneity

The bi-Langmuir isotherm represents a significant extension of the classical model designed to account for surface heterogeneity. This model assumes the adsorbent surface contains two distinct types of adsorption sites, each with different energies and capacities, which is frequently the case with real chromatographic stationary phases [6] [9]. This heterogeneity may arise from different chemical functional groups or varied surface morphologies present on the adsorbent material.

The mathematical formulation of the bi-Langmuir isotherm represents a simple summation of two Langmuir terms [6]:

q = (bs,1 qs,1 c) / (1 + bs,1 c) + (bs,2 qs,2 c) / (1 + bs,2 c)

Where the subscripts 1 and 2 refer to the two different types of adsorption sites, each with their specific saturation capacity (qs,1, qs,2) and adsorption equilibrium constant (bs,1, bs,2) [6]. This model finds particular relevance in chiral separations and other applications where the stationary phase contains multiple distinct interaction mechanisms.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Langmuir and Bi-Langmuir Adsorption Models

| Feature | Langmuir Model | Bi-Langmuir Model |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Assumption | Homogeneous, identical sites | Heterogeneous, two distinct site types |

| Site Energy Distribution | Unimodal | Bimodal |

| Mathematical Form | q = (q_s b c) / (1 + b c) | q = (bs,1 qs,1 c)/(1 + bs,1 c) + (bs,2 qs,2 c)/(1 + bs,2 c) |

| Number of Parameters | 2 (q_s, b) | 4 (qs,1, bs,1, qs,2, bs,2) |

| Application Scope | Ideal, simple systems | Complex surfaces, multiple interactions |

| Common HPLC Applications | Basic analytical separations | Chiral separations, complex mixtures |

Advanced Adsorption Phenomena and Model Limitations

Critical Assessment of Model Limitations and Applicability Boundaries

While the Langmuir and bi-Langmuir models provide valuable frameworks for understanding adsorption phenomena, researchers must recognize their inherent limitations. The classical Langmuir model's assumption of surface homogeneity is rarely satisfied in practical chromatographic systems, where most stationary phases exhibit significant heterogeneity in their binding sites [8]. Furthermore, the model assumes monolayer coverage, which becomes problematic in systems where multilayer adsorption may occur, particularly in nanoscale pores found in some advanced stationary phases or in shale systems studied for gas adsorption [8].

For the bi-Langmuir model, while it accommodates two distinct site types, real-world surfaces often contain multiple adsorption site varieties with continuous energy distributions, which neither model adequately captures [8]. Additionally, at supercritical conditions often encountered in industrial processes, the Langmuir model fails to accurately describe adsorption behavior without significant adjustments [8]. Researchers have also noted that the Langmuir model does not adequately account for molecular interactions in the adsorbed phase or the potential for adsorbate-adsorbate interactions at higher coverage levels [7] [8].

Other Adsorption Isotherm Models

Beyond the Langmuir-family models, several other isotherm types play important roles in chromatographic science:

- BET Isotherm: Accounts for multilayer adsorption, where solute molecules can adsorb onto already adsorbed layers, represented by q = (qs bs c) / [(1 - bl c)(1 - bl c + bs c)] where bs and b_l are equilibrium constants for adsorption on the stationary phase and adsorbed layers, respectively [6].

- Competitive Langmuir Models: Essential for multi-component mixtures where components compete for adsorption sites, with the form for component 1 in a two-component system being: q1 = (b1 qs,1 c1) / (1 + b1 c1 + b2 c2) [8].

- Anti-Langmuir (Type III) Isotherms: Characterized by concave curvature, representing systems where adsorption affinity increases with surface coverage [6].

Experimental Determination of Adsorption Isotherms

Methodologies and Protocols

Accurate determination of adsorption isotherms is crucial for effective chromatographic process design, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where separation optimization directly impacts product purity and cost. Several well-established methods exist for isotherm determination:

Frontal Analysis (FA) is traditionally considered the most accurate method, though it requires significant amounts of materials and solvents. In FA, solutions of the compound with increasing concentration are continuously injected into the column. For each concentration, a breakthrough curve is determined, and the amount adsorbed is calculated from the retention volume at the inflection point of this curve [6].

The Inverse Method (IM) offers a more efficient approach with lower material requirements. In this method, the isotherm is derived from the overloaded elution profile of the compound through iterative solving of the mass balance equation of liquid chromatography. A significant limitation of conventional IM is the requirement for a priori assumption of the isotherm type (Langmuir, bi-Langmuir, etc.), which introduces bias if the assumed model is incorrect [6].

Recent advancements have focused on developing model-free unbiased methods that combine the accuracy of FA with the efficiency of IM. One such approach uses spline interpolation to fit isotherm data points without presuming a specific model form, then optimizes the distribution of these points to minimize differences between measured and calculated overloaded peaks [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Adsorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Column | Housing for stationary phase where separation occurs | Column chemistry (C18, chiral, etc.), particle size, porosity (ϵ) affect separation efficiency [9] |

| Stationary Phase | Solid adsorbent material responsible for separation | Surface chemistry, functional groups, particle uniformity dictate adsorption behavior [5] |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | Carrier liquid transporting analytes through column | Purity, viscosity, chemical compatibility; often buffers or solvent mixtures [5] |

| Analyte Standards | Reference compounds for isotherm determination | High purity, known concentration; single-component for initial studies [6] |

| Calibration Solutions | Establishing concentration-response relationships | Known concentrations covering expected range; used for detector calibration [6] |

| Azepan-2-one oxime | Azepan-2-one oxime, CAS:19214-08-5, MF:C6H12N2O, MW:128.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 7-Methylindan-4-ol | 7-Methylindan-4-ol|High-Quality Research Chemical |

Computational Modeling and Simulation Approaches

Mathematical Frameworks for Chromatographic Process Simulation

The simulation of chromatographic processes relies on mathematical models that balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy. The Equilibrium-Dispersive (ED) model is widely used for simulating chromatographic processes, representing a practical compromise between simplicity and predictive capability. This model assumes instantaneous equilibrium between the mobile and stationary phases and lumps all non-equilibrium effects into an apparent dispersion term [9].

The one-dimensional mass balance equation for the ED model is expressed as:

∂Ck/∂t + F(∂qk/∂t) + u(∂Ck/∂z) = Dapp,k(∂²C_k/∂z²)

Where Ck(t, z) and q*k(t, z) represent the solute concentration of the kth component in the mobile and stationary phases, respectively, u is the linear mobile phase velocity, F = (1 - ϵ)/ϵ is the phase ratio, and D_app,k is the apparent dispersion coefficient [9].

More rigorous approaches include the General Rate Model, which accounts for axial dispersion, pore diffusion, and mass transfer resistance between liquid and solid phases. However, this increased physical accuracy comes with substantially higher computational demands [5].

Numerical Solution Techniques

Solving the nonlinear partial differential equations governing chromatographic processes requires sophisticated numerical methods. The Runge-Kutta Discontinuous Galerkin (RKDG) finite element method has emerged as a powerful technique for handling the sharp discontinuities and convection-dominated nature of these equations [9]. This method combines the flexibility of finite element methods with the stability properties of modern shock-capturing schemes, making it particularly suited for simulating chromatographic processes with nonlinear isotherms where sharp concentration fronts develop [9].

Alternative approaches include Finite Difference Methods (FDM), Finite Element Methods (FEM), and Finite Volume Methods (FVM), each with distinct advantages and limitations in terms of accuracy, stability, and computational efficiency [9].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Industrial Separations

HPLC Method Development and Optimization

In pharmaceutical research, adsorption models play a crucial role in HPLC method development and optimization. Understanding the adsorption isotherm allows researchers to predict how changes in mobile phase composition, temperature, or stationary phase chemistry will affect separation efficiency [5]. This is particularly important in the development of preparative chromatographic methods where nonlinear effects dominate and small changes in operating conditions can significantly impact product purity and yield [5] [6].

The separation of enantiomers using chiral stationary phases represents a particularly challenging application where bi-Langmuir isotherms often provide the most accurate description of adsorption behavior. The presence of two distinct types of interaction sites on these specialized phases makes the bi-Langmuir model naturally suited for modeling such systems [5].

Simulated Moving Bed (SMB) Chromatography

Simulated Moving Bed (SMB) technology has become increasingly important for large-scale continuous chromatographic separations, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry for the production of single-enantiomer drugs [5]. The successful design and operation of SMB units depend critically on accurate adsorption isotherm data for all components to be separated.

The competitive Langmuir or bi-Langmuir isotherms are frequently employed in SMB process modeling to optimize flow rates in each section and determine switching times [5]. Without accurate isotherm information, SMB processes often operate suboptimally, resulting in reduced purity, yield, and productivity.

Diagram 1: Bi-Langmuir Isotherm Determination Workflow. This diagram illustrates the integrated experimental-computational approach required for accurate adsorption model determination, highlighting the iterative refinement process often necessary when simple models prove inadequate.

The progression from the classical Langmuir model to more sophisticated approaches like the bi-Langmuir isotherm represents a necessary evolution in our understanding of adsorption phenomena on complex surfaces relevant to HPLC research and pharmaceutical development. While the Langmuir model provides an essential foundation with its clear physical interpretation and mathematical simplicity, real-world chromatographic systems often demand more nuanced models that account for surface heterogeneity, multi-component interactions, and nonlinear behavior.

The bi-Langmuir model, with its ability to describe adsorption on two distinct site types, offers significantly improved accuracy for many practical applications, particularly in chiral separations and complex mixture analysis. However, researchers must remain cognizant of the limitations of all models and select the approach that best balances physical accuracy with practical utility for their specific separation challenges.

As chromatographic science continues to advance, particularly in pharmaceutical applications where separation efficiency directly impacts product quality and cost, the ongoing refinement of adsorption models and their experimental determination methods will remain crucial. The integration of robust computational methods with accurate experimental data provides the foundation for continued innovation in chromatographic process design and optimization.

In the realm of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), the fundamental goal is the efficient separation of compounds in a chemical mixture. This separation occurs as analytes interact differently with a stationary phase while being carried by a mobile phase [1]. A core, yet often overlooked, challenge in achieving optimal separation is the inherent surface heterogeneity of chromatographic stationary phases. Rather than possessing uniform interaction sites, these surfaces contain a distribution of adsorption sites with varying energies [10]. This heterogeneity can manifest in practical issues such as peak tailing, reduced resolution, and unpredictable retention times, ultimately compromising the accuracy and reliability of analytical and preparative chromatography [10] [11].

The Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) framework has emerged as a powerful theoretical and computational tool to quantitatively map this surface heterogeneity. Moving beyond traditional adsorption isotherms that assume a uniform surface, AED models adsorption as a sum of independent homogeneous sites, each with a specific energy [10]. This provides a more realistic representation of the complex interactions occurring in the column. Within the context of chromatographic separation research, AED is not merely a theoretical concept; it is a practical asset for elucidating retention mechanisms, characterizing chromatographic systems, and explaining performance-degrading phenomena [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to AED, detailing its theoretical foundations, methodologies, and applications specifically for researchers and scientists in HPLC and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations of Adsorption Energy Distribution

The Problem of Surface Heterogeneity in Chromatography

In an ideal chromatographic system, the stationary phase would present a perfectly uniform surface to analyte molecules, resulting in symmetric, Gaussian peak shapes. In reality, stationary phases, such as common C18-bonded silicas, exhibit significant surface heterogeneity. This heterogeneity originates from variations in the chemical nature of the surface, including different types of functional groups, irregularities in ligand bonding, and variations in the underlying support structure [12] [13].

The practical consequences for HPLC research and drug development are significant. Surface heterogeneity can cause peak tailing, a phenomenon where the trailing edge of a chromatographic peak is broadened, reducing the resolution between closely eluting compounds [10]. In analytical chromatography, this leads to impaired quantification and identification, while in preparative chromatography, it results in broad, asymmetric elution profiles, lowering purification yield and efficiency [10] [11]. The extent of heterogeneity depends on the combined effects of the stationary phase, the mobile phase composition, the properties of the analyte, and the operational conditions [11].

From Adsorption Isotherms to Energy Distributions

The traditional approach to modeling adsorption in chromatography involves fitting experimental data to an adsorption isotherm model, which describes the equilibrium relationship between the concentration of an analyte in the mobile phase (c) and its concentration on the stationary phase (q) [6]. Common models include:

- Langmuir Isotherm: Assumes a homogeneous surface with a single, specific energy and no interaction between adsorbed molecules. Its equation is ( q = (bs qs c)/(1 + bs c) ), where ( qs ) is the saturation capacity and ( b_s ) is the adsorption equilibrium constant [6].

- Bi-Langmuir Isotherm: Extends the Langmuir model to describe a surface with two distinct types of adsorption sites. Its form is ( q = (b{s,1} q{s,1} c)/(1 + b{s,1} c) + (b{s,2} q{s,2} c)/(1 + b{s,2} c) ) [6].

- BET Isotherm: Accounts for multilayer adsorption, where molecules can adsorb on top of already adsorbed layers, and is represented by ( q = (qs bs c)/((1 - bl c)(1 - bl c + b_s c)) ) [6] [13].

A significant limitation of these models is their assumption of a uniform or a few discrete energy sites. They often fail to fully describe the complex interactions on a truly heterogeneous surface [10]. The AED framework overcomes this by representing the overall adsorption isotherm as a continuous integral over a distribution of adsorption energies.

The fundamental equation of AED is given by:

[ q(c) = \int_{\min}^{\max} f(\epsilon) \Theta(c, \epsilon) \, d\epsilon ]

Here, ( q(c) ) is the total concentration of adsorbed analyte, ( \epsilon ) is the adsorption energy, ( f(\epsilon) ) is the Adsorption Energy Distribution function, and ( \Theta(c, \epsilon) ) is a local adsorption model (e.g., the Langmuir model) for a site with energy ( \epsilon ) [14]. The AED ( f(\epsilon) ) quantitatively represents the proportion of sites with a specific adsorption energy ( \epsilon ), thus providing a "map" of the surface heterogeneity.

Table 1: Common Adsorption Isotherm Models and Their Characteristics

| Isotherm Model | Mathematical Form | Surface Assumption | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | ( q = \frac{bs qs c}{1 + b_s c} ) | Homogeneous, monolayer | ( qs ), ( bs ) |

| Bi-Langmuir | ( q = \frac{b{s,1} q{s,1} c}{1 + b{s,1} c} + \frac{b{s,2} q{s,2} c}{1 + b{s,2} c} ) | Heterogeneous, two discrete site types | ( q{s,1}, b{s,1}, q{s,2}, b{s,2} ) |

| BET | ( q = \frac{qs bs c}{(1 - bl c)(1 - bl c + b_s c)} ) | Homogeneous, multilayer | ( qs, bs, b_l ) |

Methodological Approaches for AED Determination

Experimental Acquisition of Adsorption Data

The first step in deriving an AED is the accurate experimental determination of an adsorption isotherm. Two primary chromatographic methods are employed for this:

- Frontal Analysis (FA): This method is traditionally considered the most accurate [6]. It involves the continuous infusion of solutions with increasing concentrations of the analyte onto the chromatographic column. For each concentration, a breakthrough curve is recorded. The amount adsorbed is calculated from the retention volume at the inflection point of this curve [6] [13]. While highly accurate, FA can require significant amounts of analyte and solvent.

- The Inverse Method (IM): This method is less material-intensive. It involves injecting a large, concentrated sample to create an overloaded elution profile [6]. The adsorption isotherm is then derived by iteratively solving the mass balance equation of liquid chromatography (the Equilibrium-Dispersive model) until the calculated peak profile matches the experimental one [6]. A critical limitation of the traditional IM is that it requires an a priori assumption of the isotherm model (e.g., Langmuir), which can bias the results if the model is incorrect.

Recent advancements have led to the development of model-free inverse methods. These methods use numerical interpolation, such as spline fitting, instead of a predefined isotherm equation to fit the overloaded peak profiles, thereby providing an unbiased determination of the adsorption isotherm with accuracy comparable to FA but with lower material consumption [6].

Computational Derivation of AED from Isotherm Data

Once a reliable adsorption isotherm is acquired, the AED is computed by solving the integral equation that defines the heterogeneous adsorption model. This is an ill-posed problem, meaning small errors in the experimental data can lead to large oscillations in the calculated distribution. Specialized computational algorithms are required to stabilize the solution.

A widely used and robust method is the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm with maximum likelihood estimation [12] [14]. The EM algorithm is an iterative procedure that converges to the most likely AED given the experimental data. The process typically begins with an initial "guess" of a uniform distribution, known as the "total ignorance guess" [14]. The algorithm then successively refines this distribution until the difference between the isotherm calculated from the AED and the experimental isotherm is minimized.

Table 2: Key Experimental Parameters for AED Studies in HPLC

| Parameter | Description | Impact on AED Determination |

|---|---|---|

| Concentration Range | The range of analyte concentrations used in Frontal Analysis or Inverse Method. | A wide range is crucial to probe both low-energy (low conc.) and high-energy (high conc.) sites [10]. |

| Mobile Phase Composition | The ratio of solvents (e.g., water/methanol) in the mobile phase. | Greatly influences analyte-stationary phase interactions and thus the measured adsorption energy [10] [12]. |

| Stationary Phase | The chemistry and structure of the column packing material. | The primary source of heterogeneity; different phases (C18, cyano, etc.) yield vastly different AEDs [12] [13]. |

| Temperature | The temperature of the chromatographic column. | Affects the kinetics and thermodynamics of the adsorption process. |

| Number of Grid Points | The number of discrete energy levels used in the numerical computation of the AED. | Affects the resolution of the AED; too few points may obscure details, too many can induce noise [11]. |

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from experiment to the final AED, integrating the key steps and algorithms discussed.

Workflow for Determining an AED

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AED Studies in HPLC

| Item / Reagent | Function in AED Analysis |

|---|---|

| Chromatographic Column | The stationary phase under investigation; its surface chemistry (e.g., C18, chiral selectors) is the primary source of adsorption heterogeneity [12] [13]. |

| Analytes (e.g., Phenol, Caffeine) | Probe molecules used to characterize the stationary phase. Their adsorption isotherms are measured, and their chemical properties (polarity, charge) determine which aspects of heterogeneity are revealed [12]. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Constitute the mobile phase (e.g., Methanol, Water, Acetonitrile). The composition modulates the interaction strength between the analyte and stationary phase, affecting the measured adsorption energy [1] [12]. |

| Adsorption Isotherm Model | A kernel function (e.g., Langmuir, BET) used in the integral equation to describe local adsorption on a homogeneous patch of the surface [10] [13]. |

| Numerical Algorithm (EM Code) | Computational software or custom code (e.g., implementing the Expectation-Maximization algorithm) to solve the ill-posed inverse problem and compute the AED from isotherm data [12] [14]. |

| (3,5-Dimethyl-pyrazol-1-yl)-acetic acid | (3,5-Dimethyl-pyrazol-1-yl)-acetic acid, CAS:16034-49-4, MF:C7H10N2O2, MW:154.17 g/mol |

| Di-tert-butyl hydrazine-1,2-dicarboxylate | Di-tert-butyl hydrazine-1,2-dicarboxylate, CAS:16466-61-8, MF:C10H20N2O4, MW:232.28 g/mol |

Applications and Interpretation in HPLC Research

Interpreting the Adsorption Energy Distribution Plot

The primary output of an AED analysis is a plot of the distribution function ( f(\epsilon) ) against the adsorption energy ( \epsilon ). The shape of this distribution provides direct insight into the nature of the stationary phase's surface:

- A single, sharp peak suggests a relatively homogeneous surface, where most sites have a similar adsorption energy.

- Multiple distinct peaks (multimodal distribution) indicate a surface with several discrete types of adsorption sites. For example, a bi-modal AED suggests two predominant site energies, which could be modeled with a bi-Langmuir isotherm [6]. A study on C18-chromolith adsorbents even revealed a trimodal distribution for phenol and a quadrimodal distribution for caffeine, indicating greater complexity than previously assumed [12].

- A broad, continuous distribution signifies a highly heterogeneous surface with a wide, smooth spectrum of adsorption site energies, which cannot be adequately described by simple isotherm models with few parameters.

Explaining Chromatographic Phenomena

AED provides a direct link between surface properties and practical chromatographic performance.

- Peak Tailing: This common issue is often a direct consequence of surface heterogeneity. A small number of high-energy adsorption sites can cause a portion of the analyte molecules to be strongly retained, resulting in the characteristic tailing of the peak. The AED visually identifies the presence and proportion of these high-energy sites [10] [11].

- Characterizing Stationary Phases: AED is a powerful tool for comparing different batches of stationary phases or different chemistries. For instance, studies have shown that non-end-capped C18 phases often exhibit detectable heterogeneity in their AED, whereas end-capped phases appear more homogeneous, explaining their superior chromatographic performance in terms of peak symmetry [13].

Elucidating Retention Mechanisms

By studying how the AED changes with different experimental conditions, researchers can deduce the fundamental mechanisms governing retention. For example, observing how the AED shifts with changes in mobile phase pH or organic modifier content can reveal the relative contributions of hydrophobic, polar, and ionic interactions to the overall retention of an analyte [10] [11]. This is particularly valuable in the development of robust analytical methods for pharmaceuticals, where understanding and controlling retention behavior is critical.

Advanced Topics and Future Directions

The application of AED is expanding beyond traditional chromatography. An emerging interdisciplinary approach uses the AED framework to analyze the kinetics of multi-substrate enzymatic reactions, drawing an analogy between substrate binding to an enzyme's active site and analyte adsorption to a heterogeneous surface [14]. This allows for the determination of Michaelis constants (( K_m )) from reaction rate data without prior knowledge of the number of competing substrates.

Furthermore, machine learning (ML) is beginning to impact this field. In materials science, interpretable ML models are being trained to predict adsorption energies on complex catalyst surfaces, helping to identify key structural and electronic features that control adsorption [15]. While currently more prevalent in catalysis, these data-driven approaches hold promise for the future characterization of chromatographic materials, potentially enabling the virtual screening of new stationary phases with tailored properties.

The Adsorption Energy Distribution framework transforms the abstract concept of surface heterogeneity into a quantifiable and visually interpretable metric. For researchers and drug development professionals working with HPLC, AED provides a deeper, mechanistic understanding of the separation process that goes beyond the limitations of traditional adsorption models. By mapping the energy landscape of stationary phases, AED directly explains practical challenges like peak tailing and serves as a powerful tool for column characterization, method development, and retention mechanism studies. As computational methods and interdisciplinary applications advance, AED is poised to remain a cornerstone technique in the fundamental research of chromatographic separation.

Within high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), peak shape serves as a primary indicator of system performance. The idealized, symmetrical Gaussian peak represents efficient mass transfer and specific, homogenous interactions between analytes and the stationary phase [16]. In practice, deviations from this ideal—specifically broadening and tailing—are common chromatographic challenges. For researchers and scientists in drug development, accurately diagnosing the root cause of these abnormalities is not merely a technical exercise but a critical prerequisite for achieving reliable quantification, maintaining method robustness, and ensuring regulatory compliance [16] [17].

The origins of peak distortions can be fundamentally categorized as either thermodynamic or kinetic in nature. Thermodynamic causes are related to the energetics of analyte retention, specifically the heterogeneity of adsorption sites on the stationary phase. In contrast, kinetic causes are related to the rates of mass transfer processes and the dynamics of analyte movement through the chromatographic system [3]. This guide provides an in-depth technical framework for differentiating between these two fundamental causes, equipping scientists with the diagnostic protocols and tools necessary for effective troubleshooting and method optimization.

Theoretical Foundations: Energetics vs. Rates

The Thermodynamic Basis of Chromatography

Chromatographic retention is fundamentally governed by thermodynamics. The distribution of an analyte between the mobile phase and the stationary phase is described by an equilibrium constant, K, which is directly related to the chromatographic capacity factor, k' [18].

K = k' β

where β is the phase ratio. This equilibrium constant is linked to the Gibbs free energy change, ΔG, for the transfer of the analyte from the mobile to the stationary phase [18]:

ΔG = -RT lnK

The Gibbs free energy change itself has both enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (ΔS) components [18]:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

In this context, peak tailing or broadening caused by thermodynamics arises from heterogeneous adsorption. When a stationary surface possesses a distribution of adsorption sites with different energies, the analyte molecules experience a range of interaction strengths. Molecules interacting with stronger sites are retained longer, leading to the characteristic tailing of the peak [3]. This is effectively modeled by isotherms such as the bi-Langmuir model, which accounts for distinct populations of adsorption sites [3].

The Kinetic Basis of Chromatography

Kinetic contributions to peak shape relate to all time-dependent processes that cause band broadening as the analyte band travels through the chromatographic system. These include:

- Longitudinal diffusion

- Resistance to mass transfer in both the stationary and mobile phases

- Extra-column effects (e.g., in tubing, injector, detector) [16] [19]

When mass transfer is slow, some analyte molecules lag behind the center of the band, leading to broadening and tailing. A common kinetic issue in HPLC is slow sorption-desorption kinetics, where the rate at which analyte molecules exchange between the mobile and stationary phases is limited [3]. In effect, the chromatography is operating under non-equilibrium conditions.

Diagnostic Experimental Protocols

Differentiating between thermodynamic and kinetic origins requires simple but deliberate experimental tests. The following protocols are designed to systematically isolate the causative factor.

Flow Rate Test for Kinetic Origins

Principle: Kinetic band broadening is directly influenced by the mobile phase flow rate. Mass transfer limitations and slow sorption-desorption kinetics become more pronounced at higher flow rates because the analyte has less time to equilibrate between phases [3].

Experimental Procedure:

- Under isocratic conditions, inject the analyte of interest and record the chromatogram at the standard method flow rate (e.g., 1.0 mL/min).

- Precisely measure the tailing factor or asymmetry factor of the target peak.

- Reduce the flow rate by at least 50% (e.g., to 0.5 mL/min), ensure system re-equilibration, and repeat the injection.

- Compare the peak tailing factors from the two experiments.

Interpretation: A significant decrease in tailing at the lower flow rate indicates a kinetic origin. The reduced flow rate allows more time for mass transfer and sorption-desorption processes, mitigating the kinetic limitation [3].

Sample Concentration Test for Thermodynamic Origins

Principle: Thermodynamic tailing caused by heterogeneous adsorption is a saturation effect. At low analyte concentrations, the high-energy adsorption sites are in vast excess, and a symmetrical peak may be observed. As the concentration increases, these selective sites become saturated, forcing later-eluting molecules to interact only with the more abundant, weaker sites, which manifests as peak tailing [3].

Experimental Procedure:

- Inject the sample at the standard method concentration and record the chromatogram.

- Precisely measure the tailing factor of the target peak.

- Dilute the sample significantly (e.g., 5- to 10-fold) and repeat the injection, ensuring the detector response remains linear.

- Compare the peak tailing factors.

Interpretation: A significant decrease in tailing at the lower sample concentration confirms a thermodynamic origin. Dilution prevents saturation of the high-energy sites, restoring a more symmetrical peak shape [3] [17].

The following workflow synthesizes these diagnostic tests into a single, actionable troubleshooting guide:

Quantitative Analysis of Peak Shape

Consistent quantification of peak shape is essential for objective diagnosis and monitoring. The two most common parameters are the USP Tailing Factor (Tf) and the Asymmetry Factor (As). Both are measured at a specified percentage of the peak height, typically 5% or 10% [16] [17] [20].

USP Tailing Factor (Tf): Tf = (a + b) / 2a, where 'a' is the width from the peak front to the peak center at 5% height, and 'b' is the width from the peak center to the peak tail at 5% height [16].

Asymmetry Factor (As): As = B / A, where 'B' is the width of the tailing half of the peak at 10% height, and 'A' is the width of the fronting half at 10% height [20].

For a perfectly symmetrical peak, Tf = As = 1.0. A value greater than 1.0 indicates tailing, while a value less than 1.0 indicates fronting. In regulated environments, a USP Tailing Factor below 1.5 is often acceptable, though values between 0.9 and 1.2 are considered ideal [16] [20].

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters Table

The following table summarizes the key parameters and their responses in thermodynamic versus kinetic scenarios, providing a quick-reference guide for interpretation.

Table 1: Key Parameter Responses for Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Peak Tailing

| Parameter | Thermodynamic Tailing | Kinetic Tailing |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Cause | Heterogeneous adsorption sites (e.g., residual silanols) [3] | Slow mass transfer/sorption-desorption kinetics [3] |

| Effect of Flow Rate | Little to no change in tailing factor [3] | Tailing factor decreases as flow rate is reduced [3] |

| Effect of Sample Load | Tailing factor increases with higher concentration/load [3] [17] | Minimal change in tailing factor with load (at analytical scales) |

| Adsorption Isotherm | Bi-Langmuir or other complex models [3] | Langmuir (if kinetics were instantaneous) |

| Typical Stationary Phase | Under-deactivated silica, aged columns | High-density bonding, superficially porous particles |

Practical Troubleshooting and Mitigation Strategies

Addressing Thermodynamic Tailing

Thermodynamic tailing, often caused by undesirable secondary interactions with the stationary phase, can be mitigated through chemical solutions.

- Mobile Phase pH Adjustment: For basic analytes, operating at a low pH (e.g., pH 3.0) protonates acidic residual silanol groups on the silica surface, minimizing ionic interactions that cause tailing [16] [20]. For acidic analytes, higher pH may be beneficial.

- Use of High-Quality Stationary Phases: Employ endcapped columns to reduce the population of accessible silanols. For challenging separations of basic compounds, highly deactivated or sterically protected columns (e.g., bidentate bonding) are superior choices [16] [20].

- Buffer Selection and Concentration: Using an appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate, ammonium formate) at a sufficient concentration (e.g., 10-50 mM) helps mask silanol activity and maintain a stable pH, improving peak shape [16] [17].

Addressing Kinetic Tailing

Kinetic tailing is mitigated by optimizing system and method parameters to enhance mass transfer.

- Reduced Flow Rate: As per the diagnostic test, lowering the flow rate provides more time for equilibration, directly improving kinetics-related tailing [3].

- Column Efficiency: Using columns packed with smaller particles (e.g., sub-2μm) or superficially porous particles (e.g., Fused-Core) enhances efficiency and reduces the contribution of slow mass transfer to band broadening [16].

- Minimization of Extra-Column Volume: Extra-column effects from tubing, injectors, and detector flow cells contribute significantly to kinetic broadening. Use narrow internal diameter tubing (e.g., 0.005") and ensure all connections are zero-dead-volume to preserve efficiency [16] [19].

- Temperature Control: Increasing the column temperature can accelerate mass transfer kinetics and reduce mobile phase viscosity, leading to improved peak shape [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogues key materials and solutions used in diagnosing and resolving peak shape issues in HPLC.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Peak Shape Investigation

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Endcapped C18 Column (e.g., Agilent ZORBAX Eclipse Plus) | Standard column for reducing secondary silanol interactions with basic analytes [20]. |

| Extended pH Column (e.g., Agilent ZORBAX Extend) | Allows operation at high pH (up to 11.5) for suppressing ionization of basic compounds, improving peak shape [16] [20]. |

| Stable Bond Column for Low pH (e.g., Agilent ZORBAX SB) | Designed for stable operation at low pH (<3) to protonate silanols and minimize tailing [20]. |

| Polar-Embedded Column | Provides additional shielding for basic compounds, reducing access to residual silanols [16]. |

| Ammonium Acetate/Formate Buffer | Volatile buffers for LC-MS compatibility; controls pH and masks silanol activity [16]. |

| Phosphate Buffer | A common UV-transparent buffer for controlling mobile phase pH in non-MS applications [17]. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Ion-pairing agent and mobile phase modifier; can improve peak shape of peptides and basic analytes [3]. |

| Narrow-Bore PEEK Tubing (0.005" ID) | Minimizes extra-column volume and associated band broadening [16]. |

| In-line Filter / Guard Column | Protects the analytical column from particulates that can block the inlet frit and create voids, a cause of peak splitting and tailing [17] [20]. |

| 2-(Methylsulfonyl)pyridine | 2-(Methylsulfonyl)pyridine, CAS:17075-14-8, MF:C6H7NO2S, MW:157.19 g/mol |

| 2,5-Diphenylpyridine | 2,5-Diphenylpyridine, CAS:15827-72-2, MF:C17H13N, MW:231.29 g/mol |

Advanced Concepts: Adsorption Energy Distributions

For persistent and complex peak shape issues, advanced modeling techniques provide deeper insight. The concept of Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) is a powerful tool that moves beyond simple model fitting (e.g., Langmuir) to reveal the full spectrum of binding energies present on a chromatographic surface [3].

AED analysis involves a mathematical inversion of experimental adsorption isotherm data to generate a distribution plot that acts as an energetic "fingerprint" of the stationary phase. A unimodal, narrow distribution indicates a homogeneous surface, while a broad or multi-modal distribution confirms thermodynamic heterogeneity [3]. This technique has been successfully applied to explain why basic solutes like metoprolol exhibit severe tailing on certain C18 columns at low pH (showing a bimodal AED) but not at high pH (showing a unimodal AED) [3]. This direct visualization of surface energy heterogeneity provides unequivocal evidence of a thermodynamic cause for tailing.

The distinction between thermodynamic and kinetic origins of peak broadening and tailing is a cornerstone of robust HPLC method development. Thermodynamic tailing, rooted in the heterogeneous energy landscape of the stationary phase, responds to changes in sample load and is remedied by chemical solutions. Kinetic tailing, arising from non-equilibrium mass transfer processes, responds to changes in flow rate and is addressed by optimizing system hydraulics and column efficiency.

Mastering the simple diagnostic tests of varying flow rate and sample concentration empowers scientists to move beyond phenomenological observations to a mechanistic understanding of their chromatographic system. This fundamental understanding, supported by advanced tools like AED, enables precise troubleshooting, ensures data integrity, and accelerates drug development by creating more reliable and transferable analytical methods.

Leveraging Biosensor Insights for Fundamental Chromatographic Understanding

Chromatography and biosensors, though often perceived as distinct analytical domains, are fundamentally united by their reliance on molecular interactions at surfaces. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) separates components based on their differential distribution between stationary and mobile phases, a process governed by the thermodynamics and kinetics of adsorption. Biosensors transform specific biological interactions into quantifiable signals, providing real-time data on binding events. The convergence of these fields offers a powerful paradigm for advancing fundamental separation science, particularly in pharmaceutical research and drug development where understanding molecular interactions is critical.

Biosensor research provides chromatographers with direct, real-time insight into binding mechanisms that are often obscured in chromatographic systems by flow dispersion and mobile phase effects. This technical guide explores how principles and data from biosensor platforms can be leveraged to deepen our understanding of chromatographic processes, ultimately enabling more predictive separation science and rational method development in HPLC.

Fundamental Principles: Shared Foundations of Molecular Interaction

Core Chromatographic Challenges Addressed by Biosensor Insights

Chromatographic separation hinges on molecular interactions that present several fundamental challenges:

Surface Heterogeneity: Chromatographic stationary phases are rarely uniform. Chiral stationary phases, particularly protein-based phases, consist of a large number of weak, non-selective sites alongside a few strong, chiral-discriminating sites. This heterogeneity explains why enantioselectivity can diminish at higher concentrations as selective sites become saturated. The bi-Langmuir isotherm model effectively describes this behavior by modeling adsorption as interaction with two distinct site types: Type I (non-selective, high-capacity) for general retention, and Type II (selective, low-capacity) for enantio-recognition [3].

Peak Tailing Origins: Peak tailing and distorted elution profiles under overload conditions can stem from either thermodynamic or kinetic heterogeneity. In thermodynamic heterogeneity, tailing occurs when strong binding sites become saturated; in kinetic heterogeneity, tailing arises when some sites have slower exchange rates. Simple diagnostic tests can distinguish these origins: if tailing decreases at lower flow rates, the origin is kinetic; if it decreases at lower sample concentrations, the cause is thermodynamic [3].

Biosensing Platforms as Mechanistic Probes

Biosensors provide complementary capabilities for investigating these chromatographic challenges:

Real-Time Binding Monitoring: Modern biosensor platforms like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and quartz crystal microbalance (QCM) generate high-resolution, time-resolved data on binding events without flow dispersion or mobile phase interference. This enables direct observation of association and dissociation rates, building a mechanistic understanding that complements chromatographic data [3].

Advanced Analysis Algorithms: Tools like the rate constant distribution (RCD) and adaptive interaction distribution algorithm (AIDA) analyze complex, multi-site binding kinetics on heterogeneous surfaces. These are conceptual analogs to the adsorption energy distribution (AED) tool used in chromatography but focus on kinetic rather than thermodynamic distributions [3].

Table 1: Core Complementary Strengths of Chromatography and Biosensors

| Analytical Technique | Molecular Interaction Insights | Key Measurable Parameters | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) | Indirect measurement via retention times and peak shapes | Retention factor, selectivity, efficiency, resolution | Flow dispersion effects, mobile phase interference, indirect readout |

| Biosensors (SPR, QCM) | Direct, real-time monitoring of binding events | Association rate (kon), dissociation rate (koff), affinity constant (KD) | Surface immobilization artifacts, limited throughput for some platforms |

Quantitative Biosensor Data Informing Chromatographic Models

Case Study: Revealing Hidden Heterogeneity in SARS-CoV-2 RBD-ACE2 Interaction

A compelling example of biosensors revealing molecular complexity comes from the reanalysis of published biosensor data describing the interaction between human ACE2 and the SARS-CoV-2 receptor binding domain (RBD). Original studies using standard one-to-one kinetic models assumed homogeneous interaction and reported single affinity constants. When researchers applied AIDA to analyze the binding data, they uncovered a broad, heterogeneous distribution of rate constants—clear evidence of multiple concurrent binding modes. In one case, the calculated affinity constant (KD) differed by more than 300% from the originally reported value, demonstrating how traditional fitting approaches can oversimplify complex biological interactions and yield misleading mechanistic conclusions [3].

Experimental Protocol: Biosensor-Based Binding Characterization

The following detailed methodology enables quantitative biomolecular interaction analysis applicable to chromatographic system characterization:

Surface Preparation: CM5 sensor chips are prepared by determining the optimal isoelectric point of the protein using acetate buffers at various pH values (e.g., pH 4.0, 4.5, 5.0, 5.5). Primary amine groups of the target protein spontaneously react with reactive succinimide esters activated by a mixture of N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) and 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC). Ethanolamine is added to deactivate excess reactive groups, with immobilization levels typically around 8000 response units (RU) for flow cell 2 [21].

Binding Affinity Measurements: Analytes are diluted in appropriate buffers to obtain a concentration series (e.g., 30.34–485.40 μM for 3-CQA). The affinity of analytes to immobilized ligands is assessed using instruments like Biacore systems with specialized evaluation software. The equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) is used to evaluate binding activity, with typical measurements performed in triplicate (n=3) for statistical reliability [21].

Data Evaluation Algorithms: Five mathematical approaches for evaluating binding curves following pseudo-first-order kinetics with different noise levels can be compared. These include linear transformation of primary data using derivatives or integrals, and integrated rate equations yielding exponential functions. Commercial software (Biacore, TraceDrawer, Scrubber) and open-source alternatives (Anabel, EvilFit) are available, though understanding the underlying models is essential to avoid misinterpretation [22].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Biosensor-Chromatography Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Technical Specifications | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| CM5 Sensor Chip | Biosensor surface for ligand immobilization | Carboxymethylated dextran matrix on gold film | General purpose protein immobilization studies [21] |

| NHS/EDC Chemistry | Activation of carboxyl groups for amine coupling | N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) | Covalent immobilization of proteins, antibodies [21] [22] |

| PEG-Based Polymers | Creating low-fouling, functionalizable surfaces | Poly(ethylene glycol) diamine (PEG-DA, MW 2000 Da), ɑ-methoxy-ω-amino PEG (PEG-MA, MW 2000 Da) | Reducing non-specific adsorption in biosensors [22] |

| HSS T3 Column | UPLC stationary phase for complex separations | 2.1 × 50 mm; particle size = 1.8 μm | Separation of phenolic acids and flavonoids in traditional medicines [21] |

Practical Applications: From Biosensor Data to Chromatographic Practice

Diagnosing and Addressing Peak Tailing

The integration of biosensor insights provides powerful diagnostic approaches for chromatographic peak tailing:

Mechanism Identification: By applying biosensor-derived principles, chromatographers can determine whether peak tailing originates from thermodynamic or kinetic heterogeneity. This distinction is crucial for selecting appropriate remediation strategies, as these different origins require fundamentally different approaches [3].

Flow Rate and Concentration Studies: Simple experimental tests can validate the mechanism: varying flow rates (with tailing decreasing at lower flow rates indicating kinetic origins) and sample concentrations (with tailing decreasing at lower concentrations indicating thermodynamic origins) [3].

Enhancing Chiral Separation Design

Biosensor research directly informs chiral chromatography development:

Surface Heterogeneity Characterization: Biosensor analysis of chiral stationary phases reveals the presence of multiple binding site types with different characteristics and capacities. This heterogeneity explains the concentration-dependent performance often observed in chiral separations [3].

Binding Site Quantification: Biosensors enable precise quantification of the relative abundance and strength of selective versus non-selective binding sites, allowing for more rational selection and optimization of chiral stationary phases for specific separation challenges [3].

Mobile Phase Additive Optimization

Biosensor techniques provide unique insights into the mechanism of mobile phase additives:

Additive versus Modifier Effects: While modifiers (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) adjust overall eluent polarity, additives (typically in low millimolar concentrations) work by competing with solutes for adsorption sites or forming complexes. Biosensors can directly probe these competitive binding mechanisms, enabling more rational additive selection [3].

Molecular-Level Mechanism Elucidation: Biosensors allow direct observation of how additives influence binding kinetics and thermodynamics, moving beyond phenomenological interpretations to fundamental mechanistic understanding [3].

Experimental Workflows and Diagnostic Frameworks

Integrated Characterization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for combining biosensor and chromatographic characterization:

Workflow for Integrated Characterization

Peak Tailing Diagnostic Framework

This diagnostic framework leverages biosensor insights to troubleshoot chromatographic peak tailing:

Peak Tailing Diagnostic Framework

The integration of biosensor insights with chromatographic science represents a paradigm shift from empirical method development toward fundamentally informed, predictive separation design. By providing direct access to binding kinetics and thermodynamics, biosensors illuminate the molecular-level phenomena that govern chromatographic performance. This synergistic approach enables researchers to diagnose separation challenges with unprecedented precision, select stationary phases based on mechanistic understanding rather than trial-and-error, and design more robust chromatographic methods. For drug development professionals facing increasingly complex separation challenges, particularly with biologics and chiral pharmaceuticals, this integrated perspective offers a powerful pathway to accelerated method development and enhanced product characterization.

As both biosensor and chromatographic technologies continue to advance—with improvements in sensitivity, throughput, and data analysis capabilities—their convergence promises to further deepen our fundamental understanding of molecular interactions and transform the practice of separation science.

Method Development and Practical Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Within the framework of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) research, the selection of an appropriate stationary phase is a fundamental strategic decision that directly dictates the success and efficiency of a separation. The stationary phase serves as the critical interface where molecular interactions determine retention, selectivity, and resolution. This guide provides an in-depth examination of three pivotal stationary phase classes—C18, chiral, and mixed-mode—situating their operational principles and performance characteristics within the broader context of chromatographic fundamentals. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this whitepaper synthesizes current market intelligence with advanced technical insights to inform method development and column selection, enabling robust analytical outcomes across pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and environmental applications.

Core Principles and Market Context

The Fundamental Role of the Stationary Phase

In HPLC, the stationary phase is the immobile substrate packed within the column, interacting with analyte molecules as the mobile phase carries them through. The thermodynamic (e.g., adsorption strength) and kinetic (e.g., mass transfer) properties of this interaction are the primary determinants of chromatographic performance [3]. A profound understanding of these principles is essential for selecting a phase that provides the requisite selectivity and efficiency for a given analytical challenge. Surface heterogeneity, a common feature where a stationary phase possesses sites with varying interaction energies, can lead to peak tailing and is a key consideration in column evaluation [3].

The HPLC Column Market Landscape

The global market for HPLC columns is experiencing robust growth, driven significantly by demands from the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors. The C18 column market alone is projected to grow from $1296 million in 2025 at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 7.4% through 2033 [23]. This expansion is fueled by continuous technological advancements and stringent regulatory requirements for quality control.

Table 1: Global C18 HPLC Column Market Snapshot (2025-2033)

| Metric | Value | Details/Segmentation |

|---|---|---|

| 2025 Market Size | $1296 million | |

| Projected CAGR (2025-2033) | 7.4% | |

| Key Market Driver | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology R&D | Accounts for ~60% (~$1.2B) of market value [23] |

| Other Key Sectors | Food & Beverage, Environmental Monitoring, Academic Research | Combined ~40% (~$800M) of market value [23] |

| Leading Players | Waters, Agilent, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Phenomenex, Restek | Highly competitive landscape driving innovation [23] [24] |

C18 Reversed-Phase Columns: The Workhorse of HPLC

Characteristics and Retention Mechanism

C18 columns, functionalized with octadecylsilane (C18) chains bonded to a silica support, are the most ubiquitous stationary phases in reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC). Their primary retention mechanism is hydrophobic interaction between the non-polar alkyl chains and non-polar regions of the analyte molecules. This makes them exceptionally versatile for separating a wide range of neutral and non-polar to moderately polar compounds.

Key Performance Factors and Selection Criteria

The performance of a C18 column is not universal; it is profoundly influenced by its physical and chemical properties. Understanding these factors is crucial for strategic selection [25] [26].

Table 2: Key Factors Influencing C18 Column Performance and Selection Guidelines

| Factor | Impact on Performance | Selection Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Load | Higher load increases hydrophobic retention; lower load shortens run times. | Select high carbon load for hydrophobic compounds; lower load for faster analysis of less hydrophobic analytes [25]. |

| Silica Purity (Class A vs. B) | Metal impurities (Class A) cause peak tailing for basic compounds; high-purity silica (Class B) yields symmetric peaks. | Prioritize Class B silica for analyzing amines or other basic compounds [26]. |

| Endcapping | Reduces secondary interactions with residual silanols, improving peak shape and reproducibility. | A standard, critical feature for most applications; ensure column is endcapped [25]. |

| Particle Size | Smaller particles (e.g., 1.7-3 µm) offer higher efficiency and resolution but require higher pressure. Larger particles (e.g., 5 µm) are suited for high-throughput or routine analysis. | Choose smaller particles for complex mixtures and UHPLC systems; larger particles for standard HPLC [25] [24]. |

| Pore Size | Smaller pores (~100 Ã…) for small molecules; larger pores (~300 Ã…) for biomolecules like proteins and peptides. | Match pore size to analyte size [25]. |

| pH Stability | Determines the range of mobile phase pH the column can withstand without degradation. | For methods requiring low or high pH, select columns with extended pH stability (e.g., pH 1-12) [25]. |

Recent Innovations and Leading Products