HPLC vs. UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Strategic Guide for Pharmaceutical Analysis

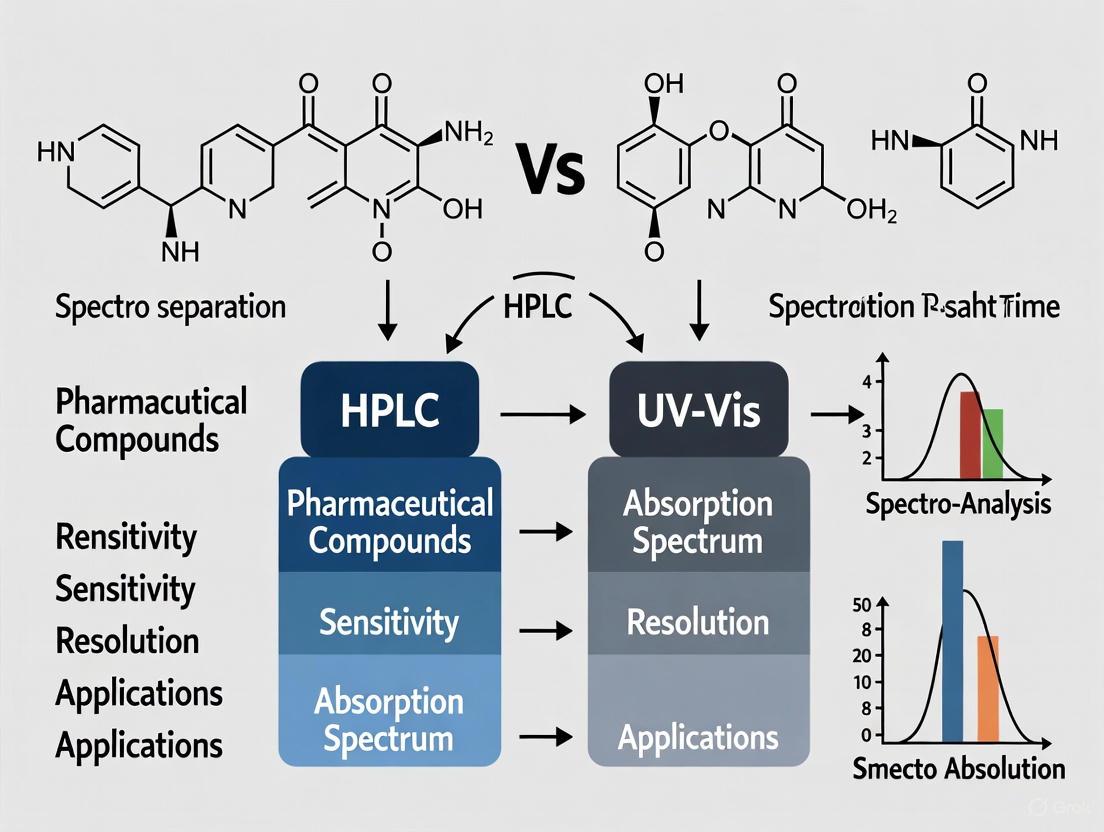

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and UV-Vis Spectroscopy for researchers and professionals in drug development.

HPLC vs. UV-Vis Spectroscopy: A Strategic Guide for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and UV-Vis Spectroscopy for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of both techniques, explores their specific methodological applications from API quantification to stability testing, and offers practical troubleshooting guidance. A detailed validation and comparative analysis equips scientists to make informed, strategic choices between these methods based on project goals, regulatory requirements, and analytical needs, supported by current case studies and future-oriented perspectives.

Core Principles: Understanding HPLC and UV-Vis Fundamentals

In the rigorous world of pharmaceutical analysis, the dual demands of ensuring product efficacy and patient safety are paramount. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and UV-Visible Spectrophotometry (UV-Vis) represent two foundational analytical techniques that address these demands from distinct perspectives. HPLC is a separation-powered technique, designed to isolate individual components from a complex mixture like a drug formulation. In contrast, UV-Vis spectroscopy embodies absorption simplicity, offering a straightforward method to quantify a target analyte based on its light-absorbing properties. The choice between these methods is not a matter of superiority but of strategic application, hinging on the specific analytical question, the complexity of the sample matrix, and the required level of specificity. This guide delves into the operational principles, comparative strengths, and optimal applications of each technique within pharmaceutical research and quality control, providing scientists with the framework to select the most effective tool for their analytical challenges.

Core Principles and Instrumentation

UV-Vis Spectroscopy: The Principle of Absorption

UV-Vis spectroscopy operates on a straightforward principle: molecules can absorb light of specific wavelengths, promoting their electrons to higher energy states. The fundamental relationship governing this technique is the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance (A) of a solution is directly proportional to the concentration (c) of the absorbing species and the path length (L) of the light through the solution, expressed as A = εlc, where ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient [1]. This direct proportionality is the bedrock of quantitative analysis using UV-Vis.

A typical UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components [1]:

- Light Source: Often a combination of lamps (e.g., deuterium for UV, tungsten-halogen for visible) to provide a broad spectrum of light.

- Wavelength Selector: A monochromator containing a diffraction grating to select a specific, discrete wavelength of light to pass through the sample.

- Sample Holder: A cuvette, typically with a standard path length of 1 cm, made of quartz for UV work or glass/plastic for visible range measurements.

- Detector: A device, such as a photomultiplier tube or photodiode, that converts the transmitted light intensity into an electrical signal, which is then processed to output an absorbance value.

The output is an absorption spectrum, a plot of absorbance versus wavelength, which can be used to identify compounds via their characteristic absorption maxima (λ_max) and for quantification against a calibration curve [1].

Figure 1: UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Workflow. The instrument selects a specific wavelength of light to pass through the sample, and the detector measures how much light is absorbed to produce a spectrum. PMT: Photomultiplier Tube.

HPLC: The Power of Separation

HPLC is a chromatographic technique that separates the components of a mixture based on their differential distribution between a stationary phase (the column packing) and a mobile phase (the liquid solvent). The core principle is that each compound in a mixture will have a unique affinity for the stationary phase, leading to different retention times as they are carried through the column by the high-pressure mobile phase [2] [3]. This physical separation is the key to HPLC's analytical power.

Modern HPLC systems are composed of several sophisticated modules [2] [3] [4]:

- High-Pressure Pump: Delivers a constant, pulseless flow of the mobile phase through the system at high pressures (typically 50-350 bar).

- Autosampler: Precisely injects a defined volume of the sample solution into the flowing mobile phase.

- Chromatographic Column: The heart of the system. It is typically a stainless-steel tube packed with micron-sized particles (e.g., C18 silica) that serve as the stationary phase.

- Detector: The most common is a UV-Vis detector, which measures the absorbance of the eluting compounds. Other detectors include fluorescence (FLD) and mass spectrometry (MS).

- Data System: Records and processes the signal from the detector, generating a chromatogram—a plot of detector response versus time.

When coupled with a UV detector (HPLC-UV), the technique not only separates compounds but also quantifies them based on the same Beer-Lambert law principles that govern standalone UV-Vis spectroscopy [3].

Figure 2: HPLC-UV System Workflow. The pump drives the mobile phase and sample through the column, where separation occurs. Components are detected and quantified as they elute, producing a chromatogram.

Critical Comparison for Pharmaceutical Analysis

The choice between HPLC and UV-Vis in a pharmaceutical context is guided by the nature of the sample and the analytical goal. The table below summarizes their core attributes for direct comparison.

Table 1: Essential Comparison of HPLC and UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Analytical Feature | HPLC | UV-Vis Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Separation based on chemical partitioning | Absorption of light by molecules |

| Key Analytical Output | Chromatogram (Response vs. Time) | Absorption Spectrum (Absorbance vs. Wavelength) |

| Sample Complexity | Ideal for complex mixtures (e.g., drug + impurities) | Best for simple solutions or single analytes [5] |

| Specificity | High (Separation + detection minimizes interference) [5] | Low to Moderate (Any compound absorbing at λ_max will interfere) [5] |

| Key Quantitative Performance | ||

| Linearity | R² > 0.999 [6] | R² > 0.999 [6] |

| Accuracy | ~99.6-100.1% [6] | ~99.8-100.5% [6] |

| Sensitivity (Typical LOQ) | Can reach 0.01% for trace impurities [2] | Less suited for trace analysis in complex matrices [5] |

| Analysis Speed | Slower (minutes to tens of minutes) | Very fast (seconds to minutes) |

| Cost & Operation | High (instrument, columns, solvents, skilled operator) | Low (simple instrument, minimal consumables) |

Strategic Selection: When to Use Which Technique

Use HPLC when:

- The sample is a complex mixture and you need to quantify multiple specific components, such as the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and its potential impurities or degradants [2].

- The matrix contains interfering compounds that absorb at the same wavelength as your target analyte [5] [7].

- The analysis requires a stability-indicating method to track the formation of degradants over time, a common requirement in pharmaceutical shelf-life studies [2].

Use UV-Vis when:

- The sample is relatively pure, or the analyte of interest is the primary light-absorbing component in the solution [6].

- The goal is rapid, high-throughput quantitative analysis of a known compound, such as the assay of a standard API in a quality control setting [6].

- Resources are limited, as UV-Vis requires less capital investment, lower operational costs, and less specialized training [1].

Experimental Protocols from Cited Research

Protocol 1: Quantification of Favipiravir in Tablet Formulation

This protocol, derived from a comparative study, outlines the parallel use of HPLC and UV-Vis for quantifying an antiviral drug, showcasing a direct methodological comparison [6].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials for Favipiravir Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Favipiravir Reference Standard | Primary standard for calibration curve | Atabay Pharmaceuticals |

| Favicovir Tablets (200 mg) | Test pharmaceutical formulation | Atabay Pharmaceuticals |

| Sodium Acetate | Buffer salt for HPLC mobile phase | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Acetonitrile (HPLC-grade) | Organic component of mobile phase | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for standard and sample prep | Milli-Q Water System |

| C18 Chromatographic Column | Stationary phase for separation | Inertsil ODS-3 (4.6 x 250 mm, 5 µm) |

2. Sample Preparation (for both methods):

- Standard Solution: A stock solution of 1000 µg/mL of favipiravir is prepared in deionized water. This is serially diluted to create a calibration range of 10–60 µg/mL [6].

- Tablet Sample Solution: Ten tablets are weighed and finely powdered. A portion equivalent to 50 mg of favipiravir is transferred to a 50 mL volumetric flask, dissolved in deionized water, sonicated, diluted to volume (resulting in 1000 µg/mL), and filtered [6].

3. HPLC Analysis:

- Mobile Phase: 50 mM Sodium acetate buffer (pH adjusted to 3.0 with glacial acetic acid) and Acetonitrile in a 85:15 (v/v) ratio [6].

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min [6].

- Column Temperature: 30 °C [6].

- Detection Wavelength: 227 nm [6].

- Injection Volume: Not specified, but typically 10-20 µL.

- Procedure: The HPLC system is equilibrated with the mobile phase. The standard and sample solutions are injected in triplicate. The concentration in the tablet is calculated based on the peak area using the calibration curve [6].

4. UV-Vis Analysis:

- Wavelength: 227 nm (determined from a prior scan of the standard solution) [6].

- Procedure: Using deionized water as a blank, the absorbance of the standard and sample solutions is measured directly in a 1.0 cm quartz cuvette. The concentration is determined from the calibration curve [6].

Protocol 2: Analyzing Drug Release from a Composite Scaffold

This study on Levofloxacin highlights a scenario where HPLC is demonstrably more reliable than UV-Vis for analysis within a complex matrix [5].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Materials for Levofloxacin Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Levofloxacin Reference Standard | Primary standard for calibration | National Institutes for Food and Drug Control |

| Ciprofloxacin | Internal Standard for HPLC | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Methanol (HPLC-grade) | Mobile phase component & solvent | Merck KGaA |

| KH₂PO₄ & Tetrabutylammonium bromide | Buffer components for HPLC mobile phase | Merck KGaA |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) | Release medium for scaffold study | Commercial Supplier |

| Sepax BR-C18 Column | Stationary phase for separation | Sepax Technologies, Inc. |

2. Sample Preparation:

- Levofloxacin-loaded composite scaffolds are immersed in SBF to study drug release over time. Aliquots of the release medium are collected for analysis [5].

3. HPLC Analysis:

- Mobile Phase: A mixture of 0.01 mol/L KH₂PO₄, methanol, and 0.5 mol/L tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulphate (75:25:4) [5].

- Flow Rate: 1 mL/min [5].

- Detection Wavelength: 290 nm [5].

- Internal Standard: Ciprofloxacin is used to improve quantification accuracy [5].

- The method demonstrated a high correlation (R² = 0.9991) and was able to accurately quantify Levofloxacin without interference from the scaffold's degradation products [5].

4. UV-Vis Analysis:

- The same samples were also measured at the λ_max for Levofloxacin. While the linearity was good (R² = 0.9999), the recovery rates were found to be less accurate than those obtained by HPLC, particularly at medium and high concentrations. This was attributed to interference from other components leaching from the scaffold material, which UV-Vis could not distinguish from the Levofloxacin signal [5].

The analytical landscape in pharmaceutical development is not a choice of a single superior technique but a strategic deployment of complementary tools. HPLC stands as the undisputed champion for separation power, offering the specificity and resolution needed to dissect complex drug formulations, monitor stability, and quantify impurities. Its ability to physically separate components before detection makes it indispensable for rigorous regulatory compliance. Conversely, UV-Vis spectroscopy excels in absorption simplicity, providing a rapid, cost-effective, and robust means of quantification for well-defined analytes in simple matrices. Understanding the fundamental principles, comparative strengths, and practical applications of both techniques, as detailed in this guide, empowers scientists and drug development professionals to make informed decisions, ensuring the efficiency, accuracy, and reliability of their analytical data.

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, the selection of an appropriate analytical technique is paramount to ensuring drug quality, safety, and efficacy. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectrophotometry represent two foundational pillars supporting drug development and quality control. Within a laboratory setting, understanding the intricate differences in their instrumentation and operational complexity enables researchers and drug development professionals to make informed decisions aligned with their analytical requirements. This technical guide provides a detailed, side-by-side examination of these two techniques, focusing on their core components, methodological workflows, and practical implementation in pharmaceutical research.

Instrumentation Breakdown: Core Components and Complexity

The fundamental differences between HPLC and UV-Vis spectroscopy begin with their instrumental architecture, which directly dictates their capabilities and operational demands.

UV-Vis Spectrophotometry Instrumentation

UV-Vis spectroscopy operates on a relatively simple principle: measuring the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by a sample. The instrumentation is designed to execute this principle efficiently [8].

- Light Source: Typically, a deuterium lamp for the UV range (190–400 nm) and a tungsten or halogen lamp for the visible range (400–800 nm) provide the broad spectrum of light required [8].

- Wavelength Selector: A monochromator, containing a prism or diffraction grating, is used to select a specific, narrow wavelength of light from the broad-spectrum source to pass through the sample [9] [8].

- Sample Container: The sample is held in a cuvette, typically with a standard path length of 1 cm, made of a material transparent to UV and/or visible light, such as quartz [9].

- Detector: A photomultiplier tube or photodiode converts the intensity of the light transmitted through the sample into an electrical signal, which is then processed to calculate absorbance [8].

A key instrumental choice is between single-beam and double-beam configurations. A single-beam instrument measures the light intensity before and after introducing the sample, while a double-beam instrument simultaneously splits the light to pass through both a sample and a reference blank, allowing for instant comparison and compensation for solvent absorption or source fluctuations [8].

HPLC Instrumentation

HPLC is a separation technique, and its instrumentation is consequently more complex, designed to handle a high-pressure liquid flow and separate components before detection [4].

- High-Pressure Pump: This component delivers the mobile phase (a solvent or mixture of solvents) at a constant, high pressure (often hundreds to thousands of bar) to push the sample through the column [10] [4].

- Injector (Auto-sampler): An automated or manual system introduces the sample mixture into the flowing mobile phase with high precision and reproducibility [4].

- Chromatographic Column: The core of the separation, the column is typically a stainless-steel tube packed with micron-sized particles (e.g., C18 silica) that act as the stationary phase. Different compounds in the sample interact differently with the stationary phase, causing them to elute at different times [10] [2].

- Detector: A variety of detectors can be used. The most common is a UV-Vis detector, which is essentially a specialized spectrophotometer that measures the absorbance of the eluting stream [10] [4]. Other detectors include fluorescence (FLD) and mass spectrometry (MS), which can provide greater sensitivity and specificity [2] [4].

- Data System: Computer software controls the entire system and processes the detector's signal to produce a chromatogram—a plot of detector response versus time—which is used for qualitative and quantitative analysis [4].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of HPLC and UV-Vis Instrumentation

| Component | HPLC | UV-Vis Spectrophotometry |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Separation followed by detection | Direct absorption measurement |

| System Complexity | High (multiple integrated modules) | Low (sequential optical path) |

| Light Source | Often a deuterium lamp within the detector | Deuterium & tungsten/halogen lamps |

| Wavelength Selection | Monochromator in detector | Monochromator before sample |

| Sample Introduction | Precision injector/autosampler | Manual placement of cuvette |

| Critical Separation Component | Chromatographic column | Not applicable |

| Detection | UV-Vis, FLD, MS, etc. | UV-Vis absorption only |

| Data Output | Chromatogram (Absorbance vs. Time) | Spectrum (Absorbance vs. Wavelength) |

Operational Workflows and Methodological Complexity

The procedural steps for performing analysis with each technique further highlight the differences in their operational complexity and the level of skill required.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Workflow

The operation of a UV-Vis spectrophotometer is relatively straightforward, making it accessible for routine quality control [11].

Figure 1: The UV-Vis spectroscopy workflow is a direct, linear process centered on absorbance measurement at a specific wavelength.

The process involves dissolving the sample in a suitable solvent, placing it in a cuvette, and measuring the absorbance at a predetermined wavelength specific to the analyte of interest, such as 241 nm for repaglinide [10] or 234 nm for metformin [12]. The concentration is then calculated directly using the Beer-Lambert law (A = εbc), which establishes a linear relationship between absorbance and concentration [9] [8]. This simplicity, however, is a double-edged sword; it requires that the sample be relatively pure, as any other light-absorbing substance (chromophore) in the solution will contribute to the total absorbance and lead to inaccuracies [11] [9].

HPLC Operational Workflow

HPLC operation is a more intricate process, involving multiple steps where parameters must be carefully optimized and controlled [2] [4].

Figure 2: The HPLC workflow is a multi-stage process involving system preparation, sample injection, on-column separation, and detection of individual components.

A typical HPLC analysis begins with the meticulous preparation of the mobile phase, which may involve buffering to a specific pH (e.g., pH 3.5 with orthophosphoric acid) to optimize separation [10]. The sample often requires pre-treatment, such as filtration, to prevent column damage. The heart of the operation is the chromatographic run, where the sample is injected and its components are separated based on their differential interaction with the stationary phase as the mobile phase flows through the column. Each separated compound elutes at a specific retention time and passes through the detector, generating a peak in the chromatogram. Quantification is achieved by integrating the area under these peaks and comparing them to a calibration curve generated from standard solutions [10] [5]. This multi-step, separation-based approach is what grants HPLC its high specificity but also contributes to its higher operational complexity and longer analysis times compared to UV-Vis [2].

Experimental Protocols and Validation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The development and validation of analytical methods are critical in pharmaceutical analysis to ensure they are fit for purpose, as mandated by ICH guidelines [10] [11]. The following protocols illustrate the application of both techniques.

Representative UV-Vis Protocol for Drug Assay

Analyte: Repaglinide in tablet dosage form [10].

- Standard Solution Preparation: A primary stock solution of repaglinide reference standard (1000 µg/mL) is prepared in methanol. Working standard solutions are then diluted from this stock to concentrations within the linear range of 5–30 µg/mL [10].

- Sample Solution Preparation: Twenty tablets are weighed and finely powdered. A portion equivalent to 10 mg of repaglinide is accurately weighed, dissolved in methanol, sonicated for 15 minutes, and made up to volume. The solution is filtered, and an aliquot is further diluted to a concentration within the linearity range [10].

- Analysis: The absorbance of the standard and sample solutions is measured against a methanol blank at a wavelength of 241 nm [10].

- Calculation: The concentration of repaglinide in the sample is determined by comparing the sample absorbance to the calibration curve of the standard solutions [10].

Representative HPLC Protocol for Drug Assay

Analyte: Repaglinide in tablet dosage form [10].

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: Agilent TC-C18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm)

- Mobile Phase: Methanol and water in a 80:20 ratio, with pH adjusted to 3.5 using orthophosphoric acid

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV at 241 nm

- Injection Volume: 20 µL [10]

- Standard and Sample Preparation: Prepared similarly to the UV-Vis method, but final dilutions are made using the mobile phase. The linearity range is typically wider, e.g., 5–50 µg/mL [10].

- System Suitability Testing: Before analysis, the system is checked for performance parameters like peak symmetry (tailing factor ~1.22), theoretical plate count, and reproducibility of retention time and peak area [10].

- Analysis and Calculation: The standard and sample solutions are injected. The peak area of repaglinide in the sample chromatogram is recorded and the concentration is determined using the calibration curve [10].

Side-by-Side Method Validation

Method validation provides objective evidence that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended use. The table below summarizes typical validation outcomes for both techniques, underscoring HPLC's superior performance for complex tasks.

Table 2: Comparison of Validated Method Parameters for HPLC and UV-Vis (Data based on repaglinide analysis [10] and levofloxacin analysis [5])

| Validation Parameter | HPLC Performance | UV-Vis Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity (R²) | > 0.999 [10] | > 0.999 [10] |

| Precision (% RSD) | < 1.5% [10] | < 1.5% [10] |

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | 99.7 - 100.3% [10] | 99.6 - 100.5% [10] |

| Specificity | High (separates analytes from impurities) [10] [5] | Limited (susceptible to interference) [11] [5] |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Lower (e.g., 0.156 µg/mL for metformin) [12] | Higher (less sensitive) [11] |

| Application Scope | Bulk drug, formulations, impurity profiling, stability studies [10] [2] | Routine QC of simple, single-component samples [11] |

A study on levofloxacin quantification further highlights a key limitation of UV-Vis. While it showed excellent linearity, its recovery rates in a complex drug-delivery system were less accurate than HPLC due to inability to distinguish the drug from other scaffold-derived impurities in the solution. This confirms that HPLC is the preferred method for accurate determination in complex matrices [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The execution of reliable HPLC and UV-Vis methods depends on the use of specific, high-quality materials and reagents.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for HPLC and UV-Vis Analysis

| Item | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents (e.g., Methanol, Acetonitrile) | Act as the mobile phase to transport the sample through the system. | Low UV absorbance and high purity are critical to minimize baseline noise and ghost peaks [10] [4]. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., Potassium Dihydrogen Phosphate) | Modify mobile phase pH to control ionization of analytes, improving separation. | Must be volatile if coupling with MS detection. pH must be carefully optimized and controlled [10] [5]. |

| Chromatographic Column (e.g., C18) | The stationary phase where the physical separation of sample components occurs. | Selection depends on analyte properties (polarity, pH stability). Column chemistry, length, and particle size dictate efficiency and resolution [10] [2]. |

| Reference Standard | Highly pure analyte used for calibration and quantification. | Essential for constructing accurate calibration curves. Purity must be certified [10] [11]. |

| UV-Transparent Cuvettes | Hold the liquid sample in the spectrophotometer's light path. | Must be made of quartz for UV range analysis; path length is standardized (e.g., 1 cm) [9] [8]. |

| Filters (Syringe Filters) | Remove particulate matter from samples prior to HPLC injection. | Prevents clogging of HPLC lines and column, protecting the instrumentation [4]. |

The choice between HPLC and UV-Vis spectroscopy is a strategic decision balancing analytical needs against operational resources. UV-Vis spectrophotometry offers a straightforward, cost-effective, and rapid solution for the quantitative analysis of pure, chromophore-containing substances, making it ideal for high-throughput, routine quality control of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in simple formulations. However, its fundamental limitation is its lack of inherent separation power, making it vulnerable to interference from excipients, impurities, or degradation products. In contrast, HPLC presents a more complex and costly operational landscape, requiring significant expertise and more elaborate sample preparation. Its unparalleled strength lies in its ability to separate, identify, and quantify individual components within a complex mixture. This makes HPLC an indispensable tool for demanding applications such as impurity profiling, stability-indicating assays, and analysis of multi-component formulations. For the pharmaceutical researcher, the decision is clear: UV-Vis is a precise scalpel for defined, simple tasks, while HPLC is the versatile power tool essential for navigating the complexities of modern drug development and ensuring the highest standards of product quality.

Inherent Advantages and Limitations of Each Method

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring the identity, purity, safety, and efficacy of drug substances and products is paramount. Analytical method development and validation form the cornerstone of drug quality assurance throughout the product lifecycle, from development to post-marketing surveillance [11]. Among the numerous analytical techniques available, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy remain two of the most widely employed methods for pharmaceutical analysis [11]. Each technique offers a distinct set of capabilities that make it suitable for specific applications within drug development and quality control. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the inherent advantages and limitations of HPLC and UV-Vis spectroscopy, contextualized within pharmaceutical analysis research. The objective is to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a clear understanding of the strategic considerations for method selection based on analytical requirements, sample complexity, and regulatory constraints.

Core Technological Foundations

UV-Vis Spectroscopy operates on the principle of measuring the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by analyte molecules. When samples contain chromophores—functional groups that absorb light in the UV-Vis range (typically 190-800 nm)—electrons transition to higher energy states, resulting in characteristic absorption spectra [11] [13]. The relationship between absorbance and concentration is governed by the Beer-Lambert law, enabling quantitative analysis. This technique is primarily used for quantitative determination of analytes that contain light-absorbing chromophores in their molecular structure [11].

HPLC is a separation technique that resolves complex mixtures into individual components based on their differential partitioning between a mobile phase (liquid) and a stationary phase (packed column) [2]. The separated components then pass through a detector—often a UV-Vis, Photodiode Array (PDA), Mass Spectrometry (MS), or other specialized detector—for identification and quantification [13]. This two-stage process (separation followed by detection) provides an additional dimension of selectivity compared to stand-alone spectroscopic techniques [11] [2].

Direct Comparison of Key Characteristics

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of both techniques, highlighting their core differences:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of UV-Vis Spectroscopy and HPLC

| Characteristic | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | HPLC |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Principle | Absorption of light by chromophores | Differential separation followed by detection |

| Selectivity | Limited; relies on spectral differences | High; based on separation mechanism and detection |

| Sample Complexity | Suitable for simple mixtures or single components | Ideal for complex mixtures with multiple analytes |

| Analysis Speed | Fast (typically minutes) | Moderate to slow (method-dependent) |

| Cost & Equipment | Low cost; simple instrumentation | High cost; complex instrumentation [11] |

Advantages and Limitations in Technical Detail

UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Strengths and Weaknesses

Key Advantages

UV-Vis spectroscopy offers several compelling advantages for pharmaceutical analysis:

- Operational Simplicity and Cost-Effectiveness: The technique requires minimal training to operate, and the instruments have lower acquisition and maintenance costs compared to HPLC systems, making them particularly accessible for small businesses and routine quality control [11].

- Rapid Analysis: With minimal sample preparation and direct measurement capabilities, UV-Vis can provide analytical results in minutes, facilitating high-throughput screening and rapid batch release testing for simple formulations [11].

- Sufficient Sensitivity for Many APIs: For quality control assays of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) with strong chromophores, UV-Vis provides adequate sensitivity and precision without the need for complex method development [11].

Inherent Limitations

Despite its advantages, UV-Vis spectroscopy suffers from significant technical limitations:

- Limited Specificity: The technique cannot distinguish between the target analyte and other UV-absorbing substances, such as excipients, degradation products, or impurities, leading to potential interference and inaccurate quantification [11].

- Chromophore Dependency: Analytes must contain chromophores to be detectable, rendering the technique unsuitable for compounds lacking UV absorption characteristics [11].

- Limited Capability for Multi-Component Analysis: Without separation capabilities, UV-Vis struggles to accurately quantify individual components in complex formulations, as overlapping absorption spectra cannot be deconvoluted with confidence [11].

HPLC: Strengths and Weaknesses

Key Advantages

HPLC delivers powerful analytical capabilities that address many limitations of spectroscopic methods:

- Exceptional Selectivity and Resolution: HPLC provides two dimensions of selectivity—chromatographic separation and detection—enabling the resolution of complex mixtures into individual components, including isomers, impurities, and degradants [11] [2].

- Comprehensive Quantitative Capabilities: The technique offers excellent precision (RSD < 0.2% achievable with UV detection), sensitivity (capable of detecting impurities at 0.01% levels), and a wide linear dynamic range, making it suitable for both major component assays and trace analysis [14] [2].

- Versatile Detection Options: While UV detection is common, HPLC can be coupled with various detectors including PDA (for peak purity assessment), fluorescence (for enhanced sensitivity), MS (for structural identification), and others, expanding its application scope [13].

- Regulatory Acceptance: HPLC is the gold standard for stability-indicating methods, impurity profiling, and other regulated analyses, with well-established validation protocols and regulatory precedence [11] [14].

Inherent Limitations

The sophisticated capabilities of HPLC come with notable drawbacks:

- High Complexity and Cost: HPLC instrumentation is substantially more expensive to acquire, maintain, and operate. The systems require significant laboratory space, regular maintenance, and skilled personnel for operation and troubleshooting [11] [14].

- Time-Consuming Method Development: Developing and validating a robust HPLC method can be a lengthy process, requiring optimization of numerous parameters including column chemistry, mobile phase composition, pH, temperature, and flow rate [11].

- Substantial Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation: Traditional HPLC systems consume significant volumes of high-purity solvents, creating environmental concerns and waste disposal challenges, though this is being addressed by UHPLC and miniaturized systems [11].

- Labor-Intensive Sample Preparation: While analysis itself is automated, sample preparation often remains manual, involving weighing, grinding, extraction, and filtration steps that require skilled technical execution [14].

Method Validation and Regulatory Considerations

Validation Parameters for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Both HPLC and UV-Vis methods require thorough validation to ensure reliability, accuracy, and reproducibility for their intended applications. Key validation parameters include [11]:

- Specificity/SELECTIVITY: The ability to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of other components. HPLC generally excels in this parameter due to its separation power.

- Linearity and Range: The ability to obtain test results proportional to analyte concentration, and the interval between upper and lower concentration levels. Both techniques can demonstrate excellent linearity when properly validated.

- Accuracy and Precision: The closeness of measured values to the true value (accuracy) and the agreement between series of measurements (precision). HPLC typically provides superior precision, especially for complex samples.

- Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The lowest concentrations of an analyte that can be detected or quantified with acceptable accuracy and precision.

- Robustness and Ruggedness: The reliability of an analysis under normal but variable laboratory conditions, and its performance when conducted by different analysts or instruments.

Regulatory Framework

Pharmaceutical analysis operates within a strict regulatory framework governed by ICH (International Council for Harmonisation), FDA (Food and Drug Administration), USP (United States Pharmacopeia), and other regulatory bodies [11] [14]. These organizations provide detailed guidelines for analytical method validation, including ICH Q2(R2) for validation of analytical procedures [11]. The choice between HPLC and UV-Vis must consider these regulatory expectations, with HPLC often being required for stability-indicating methods and impurity profiling due to its superior specificity [14].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Case Study: Levofloxacin Analysis Comparison

A comparative study of Levofloxacin analysis demonstrates the practical performance differences between HPLC and UV-Vis methods [5]:

HPLC Methodology for Levofloxacin

- Chromatographic Conditions: Separation was performed using a Sepax BR-C18 column (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) maintained at 40°C. The mobile phase consisted of 0.01 mol/L KH₂PO₄, methanol, and 0.5 mol/L tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulphate (75:25:4 ratio) delivered at 1.0 mL/min flow rate [5].

- Detection: UV detection at 290 nm with an injection volume of 10-20 µL.

- Sample Preparation: Levofloxacin standard solutions were prepared in simulated body fluid (SBF). Samples were vortex-mixed with internal standard (ciprofloxacin), extracted with dichloromethane, centrifuged, and the supernatant was dried under nitrogen before reconstitution [5].

- Performance Metrics: The method demonstrated a linear range of 0.05-300 µg/mL with a regression equation of y = 0.033x + 0.010 (R² = 0.9991). Recovery rates for low, medium, and high concentrations (5, 25, and 50 µg/mL) were 96.37±0.50%, 110.96±0.23%, and 104.79±0.06%, respectively [5].

UV-Vis Methodology for Levofloxacin

- Spectroscopic Conditions: Standard solutions of Levofloxacin in SBF were scanned from 200-400 nm to determine the maximum absorption wavelength [5].

- Sample Preparation: Direct measurement of Levofloxacin standards in SBF without extensive sample preparation.

- Performance Metrics: The method demonstrated a linear range of 0.05-300 µg/mL with a regression equation of y = 0.065x + 0.017 (R² = 0.9999). Recovery rates for low, medium, and high concentrations were 96.00±2.00%, 99.50±0.00%, and 98.67±0.06%, respectively [5].

The study concluded that UV-Vis provided inadequate accuracy for measuring drug concentrations in complex composite scaffolds due to interference, while HPLC emerged as the preferred method for investigating sustained-release properties in tissue engineering applications [5].

Workflow Comparison

The fundamental workflows for both techniques are visualized below, highlighting their operational differences:

Diagram 1: Analytical technique workflows compared

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for implementing both analytical techniques in pharmaceutical research:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC and UV-Vis Analysis

| Category | Specific Items | Technical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC Columns | C18, C8, phenyl, cyano stationary phases | Differential separation of analytes based on chemical properties | Column chemistry selection critical for method specificity [15] |

| Mobile Phase Components | HPLC-grade methanol, acetonitrile, water; buffer salts (phosphate, formate) | Carrier medium for analytes; pH and ionic strength control | Volatile buffers preferred for LC-MS applications [14] |

| Reference Standards | Certified reference materials (CRMs), internal standards | Quantification and method calibration | Purity and traceability documentation essential for regulated labs [11] |

| Sample Preparation | Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges, filtration units, volumetric glassware | Sample clean-up, concentration, precise volume measurement | Class A volumetric flasks required for regulated testing [14] |

| UV-Vis Specific | Quartz cuvettes, wavelength standards | Sample containment, wavelength accuracy verification | Quartz required for UV range; plastic suitable for visible only [11] |

| System Suitability | Retention marker solutions, column performance tests | Verification of system performance before sample analysis | Mandatory for regulated HPLC analysis per GMP requirements [14] |

Strategic Method Selection and Future Perspectives

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The choice between HPLC and UV-Vis should be guided by analytical requirements and practical constraints:

- For Routine QC of Simple Formulations: UV-Vis is often sufficient for single-component assays, content uniformity testing, and dissolution testing where specificity is not a primary concern [11].

- For Complex Mixtures and Stability Studies: HPLC is essential for analyzing multi-component formulations, conducting impurity profiling, and developing stability-indicating methods where specificity is critical [11] [2].

- When Specificity is Paramount: HPLC with PDA or MS detection provides the highest level of confidence in peak identity and purity, essential for method development and troubleshooting [13].

- When Resources are Limited: UV-Vis offers a cost-effective alternative for laboratories with budget constraints or those performing high-volume routine testing [11].

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of pharmaceutical analysis continues to evolve with several notable trends:

- Hybrid and Advanced Systems: The combination of HPLC with UV-Vis detection (HPLC-UV) or diode array detection (HPLC-DAD) leverages the strengths of both techniques, providing separation capability with spectral confirmation [11].

- Green Analytical Chemistry: Developments in miniaturized HPLC systems and solvent reduction approaches address environmental concerns associated with traditional HPLC methods [11].

- UHPLC and Advanced Detection: Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC) using sub-2µm particles provides superior resolution, speed, and sensitivity compared to conventional HPLC [15]. Coupling with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) offers unparalleled specificity and structural elucidation capabilities [11] [2].

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): There is growing implementation of real-time monitoring using spectroscopic methods, particularly in biopharmaceutical manufacturing, to enhance process understanding and control [16].

Both HPLC and UV-Vis spectroscopy occupy critical positions in the pharmaceutical analyst's toolkit, with each offering distinct advantages suited to particular applications. UV-Vis spectroscopy provides a rapid, cost-effective solution for simple, high-throughput analyses where specificity is not a limiting factor. In contrast, HPLC delivers the separation power, specificity, and sensitivity required for complex pharmaceutical analyses, particularly for regulated methods where comprehensive characterization is essential. The strategic selection between these techniques—or their combination in hybrid approaches—should be guided by the specific analytical requirements, sample complexity, regulatory considerations, and available resources. As pharmaceutical analysis continues to evolve, both techniques will maintain their relevance, with advancements focused on enhancing efficiency, sensitivity, and environmental sustainability.

Within pharmaceutical analysis research, the selection of an appropriate analytical technique is paramount to generating reliable, accurate, and regulatory-compliant data. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) represent two foundational pillars in the analyst's toolkit, yet they serve distinct purposes and offer different levels of analytical power [11]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide framed within a broader thesis on the differences between these two techniques. It presents a structured decision framework to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals select the optimal method based on specific analytical scenarios, sample complexity, and regulatory requirements. The core thesis is that while UV-Vis offers speed and simplicity for specific, well-defined analyses, HPLC provides the separation power and specificity necessary for complex matrices and rigorous quality control.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Core Concepts

UV-Vis spectroscopy is an analytical technique that measures the amount of discrete wavelengths of UV or visible light that are absorbed by or transmitted through a sample in comparison to a reference or blank sample [1]. The fundamental principle is based on the excitation of electrons to higher energy states by photons of light, with the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) providing a characteristic property of the analyte [1]. The relationship between absorbance (A), concentration (c), path length (L), and the molar absorptivity (ε) is governed by the Beer-Lambert law (A = εcL), which forms the basis for quantitative analysis [1].

A typical UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components: a light source (often a deuterium lamp for UV and a tungsten/halogen lamp for visible light), a wavelength selector (such as a monochromator with a diffraction grating), a sample compartment, and a detector (e.g., a photomultiplier tube or photodiode) to convert light into an electronic signal [1]. The entire process enables the rapid acquisition of an absorption spectrum, which plots absorbance against wavelength.

HPLC: Core Concepts

HPLC is a separation technique that resolves the components of a mixture based on their differential partitioning between a mobile phase (liquid) and a stationary phase (packed inside a column) [17] [18]. The resolved components elute from the column at different times (retention times) and are then detected, typically by a UV-Vis detector, which functions on the same principles described above [14]. This combination of high-resolution separation with sensitive detection is what gives HPLC its power.

A standard HPLC system includes a pump for delivering the mobile phase at high pressure, an injector for introducing the sample, a column oven for temperature control, the analytical column itself, a detector, and a data system [17] [14]. The choice of stationary phase (e.g., C18 for reversed-phase chromatography) and mobile phase composition are critical parameters that are optimized during method development to achieve the desired separation [17] [18].

Comparative Technical Performance: UV-Vis vs. HPLC

The choice between UV-Vis and HPLC is fundamentally a trade-off between simplicity and informational complexity. The table below summarizes the core technical and operational differences between the two techniques.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of UV-Vis spectroscopy and HPLC

| Aspect | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measures light absorption by molecules [1] | Separates components followed by detection (e.g., UV) [17] [18] |

| Primary Strength | Speed, cost-effectiveness, simplicity [11] | High selectivity, specificity, and resolving power [11] [14] |

| Selectivity | Limited; susceptible to spectral overlaps [11] | Excellent; can separate and quantify multiple analytes in a mixture [11] |

| Sensitivity | Good for simple assays [11] | Superior; can detect low-level impurities [11] |

| Sample Preparation | Typically minimal [11] | Often required and can be labor-intensive (e.g., extraction, filtration) [11] [14] |

| Analysis Speed | Very fast (seconds to minutes) [11] | Moderate to slow (minutes to tens of minutes) [11] |

| Cost | Low equipment and operational cost [11] | High instrumentation cost and maintenance [11] [14] |

| Key Limitation | Requires chromophore; cannot analyze complex mixtures [11] [1] | Complex operation; requires skilled personnel and method development [11] [14] |

| Ideal Use Case | Routine QC of simple samples, dissolution testing, raw material identity [11] [19] | Assay of complex formulations, impurity profiling, stability-indicating methods [11] [14] |

Quantitative data from direct comparison studies highlight these performance differences. For instance, a study on metformin hydrochloride found that while both methods were valid, HPLC (UHPLC) demonstrated better precision (RSD < 1.578% for repeatability) compared to UV-Vis (RSD < 3.773% for repeatability) [12]. Another study on Levofloxacin showed that HPLC provided more accurate recovery rates (e.g., 104.79±0.06% at high concentration) compared to UV-Vis (98.67±0.06%) when the drug was loaded onto a complex composite scaffold, underscoring HPLC's superiority in the presence of potential interferents [5].

Decision Framework for Method Selection

Selecting the right analytical tool requires a systematic assessment of the analytical goal, sample properties, and operational constraints. The following diagram provides a visual workflow for this decision-making process.

Decision Workflow for Analytical Tool Selection

Framework Application Guidelines

The decision nodes in the workflow are defined by the following critical questions:

- Assess Sample Complexity: Is the sample a simple solution, a pure active pharmaceutical ingredient (API), or a complex mixture like a formulated product? UV-Vis is suitable only for the former, as it cannot distinguish between multiple absorbing species [11]. For complex mixtures, a separation technique is required.

- Determine the Need for a Chromophore: Does the analyte contain a functional group that absorbs UV or visible light? UV-Vis requires the presence of a chromophore for detection. If absent, HPLC with an alternative detector (e.g., refractive index, mass spectrometry) is necessary [18].

- Define Specificity and Purity Requirements: Is the goal to simply quantify a major component, or is identification and quantification of impurities, degradants, or co-formulants required? HPLC is the definitive choice for stability-indicating assays and impurity profiling due to its high resolution [14].

- Evaluate Operational Constraints: What are the constraints regarding budget, time for analysis, and technical expertise? UV-Vis is less expensive, faster, and requires less training, making it ideal for high-throughput routine QC. HPLC, while more resource-intensive, delivers comprehensive data that is often required for regulatory filings [11] [14].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for UV-Vis Spectrophotometric Assay of an API

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing the analysis of metformin hydrochloride [12].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential materials for UV-Vis analysis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Instrument for measuring light absorption [1] |

| Quartz or UV-transparent Cuvettes | Sample holder; quartz is essential for UV range [1] |

| Analytical Balance | Precisely weighing the reference standard and sample |

| Volumetric Flasks | For accurate preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions |

| Reference Standard (e.g., Metformin HCl) | High-purity compound to create a calibration curve [12] |

| Suitable Solvent (e.g., Methanol:Water) | Dissolves the analyte and is transparent in the measured wavelength range [12] |

2. Methodology

- Wavelength Selection: Prepare a standard solution of the API and scan it over the UV-Vis range (e.g., 200-400 nm). Identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax). For metformin, this was found to be 234 nm [12].

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Accurately weigh the reference standard. Dissolve and dilute to prepare a stock solution. Subsequently, prepare a series of standard solutions covering a defined concentration range (e.g., 2.5-40 μg/ml) by serial dilution [12].

- Sample Preparation: Extract and dilute the pharmaceutical sample (e.g., powdered tablets) using the same solvent as the standards to ensure the analyte concentration falls within the linear range of the calibration curve.

- Measurement and Quantification: Using the solvent as a blank, measure the absorbance of each standard and the sample solution at the predetermined λmax. Construct a calibration curve by plotting absorbance versus concentration. Determine the concentration of the API in the sample solution using the regression equation of the calibration curve [12].

Protocol for HPLC Assay and Impurity Profiling

This protocol outlines the development and validation of an HPLC method for pharmaceutical analysis, as per ICH guidelines [17].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 3: Essential materials for HPLC analysis

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| HPLC System | Instrument comprising pump, injector, column oven, detector, and data system [14] |

| Analytical Column (e.g., C18) | Stationary phase for separating mixture components [17] |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents & Reagents | Mobile phase components (e.g., water, acetonitrile, methanol, buffers) [17] |

| Syringe Filters (e.g., 0.45 μm) | For filtering mobile phase and sample solutions to protect the column |

| Reference Standards (API and Impurities) | For identification and quantification of target analytes [17] |

2. Methodology

- Method Development [17] [18]:

- Column and Mobile Phase Selection: Begin with a common column (e.g., 15 cm C18, 5 μm particle size) and a binary mobile phase (e.g., acetonitrile/water or methanol/water buffer). A typical initial flow rate is 1.0-1.5 mL/min.

- Optimization: Use gradient elution for initial scouting. Adjust the mobile phase composition (organic modifier percentage, pH, buffer concentration) to achieve resolution between the API and all known impurities/degradants. The goal is a robust method where all peaks are baseline-resolved.

- System Suitability Testing (SST) [14]: Before sample analysis, perform SST to ensure the system is performing adequately. This involves injecting a standard solution to confirm parameters like retention time reproducibility, theoretical plate count, tailing factor, and resolution meet predefined criteria.

- Sample Analysis:

- Preparation of Standards and Samples: Accurately prepare standard solutions of the API and impurities. Prepare the sample solution by extracting the drug product, ensuring it is compatible with the mobile phase.

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject the standards and samples. A well-developed method will show clear separation of the API from its impurities and excipients, as demonstrated in the chromatogram of progesterone where the analyte was resolved from the placebo formulation [17].

- Quantification: Identify peaks by comparing retention times with standards. Quantify the API and impurities using their respective calibration curves, ensuring the method is validated for its intended purpose (assay or impurities) as per ICH Q2(R2) [17].

In pharmaceutical analysis, there is no single "best" technique—only the most appropriate one for a specific question. UV-Vis spectroscopy serves as an efficient and cost-effective tool for routine quality control of raw materials and simple formulations where specificity is not a primary concern. In contrast, HPLC is the indispensable technique for method development requiring definitive identification, precise quantification, and rigorous impurity profiling in complex matrices. The provided decision framework, grounded in technical principles and practical constraints, empowers scientists to make informed, defensible choices. This ensures that the selected analytical strategy not only delivers scientifically sound data but also aligns with project timelines, resources, and ultimate regulatory objectives.

Techniques in Action: Method Development and Real-World Applications

UV-Vis for Rapid Assay and Stability Testing in Formulations

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring the identity, purity, strength, and stability of drug substances and products is paramount. Analytical techniques such as UV-Vis spectrophotometry and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) play central but distinct roles in pharmaceutical analysis [11]. While HPLC is often considered the gold standard for specific separations and impurity profiling, UV-Vis spectrophotometry remains a vital technique for rapid assay and stability testing, particularly in resource-limited settings or for routine quality control of simple formulations [11] [20]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide on the application of UV-Vis spectrophotometry for these purposes, framing its utility within the broader context of analytical method selection by comparing its capabilities with those of HPLC.

The fundamental principle of UV-Vis spectrophotometry involves measuring the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by a compound in solution. The amount of light absorbed at a specific wavelength is directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte, as described by the Beer-Lambert law [20] [21]. This straightforward relationship enables the rapid and cost-effective quantification of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) that contain chromophores—functional groups that absorb light in the UV-Vis region [11].

Theoretical Foundations and Comparative Analysis with HPLC

Core Principles of UV-Vis Spectrophotometry

UV-Vis spectrophotometry operates on the Beer-Lambert Law, which states a linear relationship between absorbance (A), molar absorptivity (ε), path length (b), and analyte concentration (c): A = εbc. This foundational principle allows for the direct quantification of chromophore-containing compounds without the need for complex separation steps [20] [21]. Method development typically involves identifying the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for the API, establishing a linear calibration curve across a relevant concentration range, and validating method parameters as per ICH guidelines [20] [22].

HPLC as a Comparative Technique

HPLC, particularly reversed-phase chromatography with UV detection, separates components in a mixture based on their differential partitioning between a stationary and mobile phase [11] [14]. It provides high resolving power, allowing for the simultaneous quantification of multiple active ingredients, impurities, and degradation products in a single run [14]. The detection principle for HPLC-UV still relies on UV absorption, but the chromatographic separation step occurs prior to detection, conferring superior specificity for complex mixtures [11] [23].

Direct Comparison of UV-Vis and HPLC

The choice between UV-Vis and HPLC hinges on the analytical problem, sample complexity, and available resources. The table below summarizes the core differences, highlighting why UV-Vis remains a workhorse for rapid, straightforward analyses despite the superior separation power of HPLC.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of UV-Vis Spectrophotometry and HPLC for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Aspect | UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measurement of light absorption by chromophores [11] | Chromatographic separation followed by detection (e.g., UV) [11] |

| Cost & Equipment | Low cost; simple instrument setup [11] | High cost; complex instrumentation [11] [14] |

| Selectivity & Specificity | Limited; prone to spectral overlaps from excipients or impurities [11] | High; excellent separation capabilities [11] [14] |

| Sensitivity | Good for simple assays in µg/mL range [20] [22] | Superior; can detect impurities at ng/mL levels [11] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; often just dissolution and dilution [11] | Can be complex; may require extraction, filtration [11] [14] |

| Analysis Speed | Very fast (minutes per sample) [11] | Moderate to slow (tens of minutes per run) [11] |

| Ideal Use Cases | Routine QC of simple formulations, single-component analysis [11] [21] | Complex mixtures, impurity profiling, stability-indicating methods [11] [5] |

Experimental Protocols for UV-Vis Method Development and Application

Method Development and Validation for API Assay

A validated UV-Vis method ensures that the procedure is suitable for its intended use, providing reliable and reproducible results [11] [20]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for developing and validating a method for assaying an API in a formulation.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UV-Vis Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard | Highly purified analyte used to establish the calibration curve and validate the method. | Candesartan cilexetil bulk drug [20] |

| Appropriate Solvent | Dissolves the analyte without interfering in the UV absorption at the λmax. | Methanol:Water (9:1) for Candesartan [20] |

| Pharmaceutical Formulation | The finished dosage form (e.g., tablet, capsule) to be analyzed. | Candesartan 8 mg tablets [20] |

| Forced Degradation Reagents | Chemicals used to stress the API and demonstrate method specificity. | 0.1 N HCl, 0.1 N NaOH, 3% H₂O₂ [20] [22] |

Procedure:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Accurately weigh and transfer an appropriate amount of the API reference standard into a volumetric flask. Dissolve and dilute to volume with a suitable solvent to obtain a primary stock solution of known concentration (e.g., 100 µg/mL) [20].

- Wavelength Determination (λmax): Dilute the stock solution to a concentration within the expected linear range (e.g., 10 µg/mL). Scan this solution over the UV range (e.g., 200-400 nm) against a solvent blank. The wavelength corresponding to the maximum absorbance is selected as the λmax for the assay [20]. For candesartan cilexetil, this was found to be 254 nm [20].

- Calibration Curve Construction: Prepare a series of standard solutions from the stock solution to cover a defined concentration range (e.g., 10-90 µg/mL). Measure the absorbance of each standard at the λmax and plot absorbance versus concentration. The regression equation and correlation coefficient (R²) should be calculated. A value of R² > 0.999 indicates excellent linearity [20] [22].

- Sample Analysis: Powder and homogenize a representative number of tablets. Accurately weigh a portion equivalent to one dose and transfer to a volumetric flask. Add solvent, sonicate to dissolve the API, dilute to volume, and filter if necessary. Dilute the sample to a concentration within the calibration range, measure its absorbance, and calculate the API content using the regression equation [20].

- Method Validation: The method must be validated as per ICH guidelines [20] [22].

- Accuracy: Perform recovery studies by spiking a pre-analyzed sample with known amounts of the standard (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120%). Recovery should typically be between 98-102% [20].

- Precision: Determine repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst). Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) should generally be less than 2% [20].

- LOD and LOQ: Calculate the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) from the calibration data, e.g., LOD = 3.3σ/S and LOQ = 10σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the response and S is the slope of the calibration curve [22].

Stability-Indicating Studies and Forced Degradation

A stability-indicating method can accurately quantify the API and detect the presence of degradation products, even if they co-elute or absorb similarly in a simple UV scan. While HPLC is inherently more specific for this purpose, a UV-Vis method can be stability-indicating if it is proven that degradation products do not interfere with the quantification of the intact API [20] [22].

Forced Degradation Protocol:

- Acidic/Alkaline Hydrolysis: Treat the API solution with a defined volume of acid (e.g., 0.1 N HCl) or base (e.g., 0.1 N NaOH). Reflux the solution at an elevated temperature (e.g., 60°C) for a specified period, withdrawing samples at intervals to monitor degradation [20] [22].

- Oxidative Degradation: Expose the API solution to an oxidizing agent such as 3% hydrogen peroxide. Keep the solution in the dark for a period (e.g., 12 hours) and sample at intervals for analysis [20].

- Thermal Degradation: Subject the solid API to dry heat in an oven (e.g., at 60°C) and sample periodically [20].

- Photolytic Degradation: Spread the solid API in a thin layer and expose it to direct sunlight or a UV light source for several days, sampling at regular intervals [20].

For each stress condition, prepare a sample at the intended assay concentration and measure the absorbance. The method is considered stability-indicating if there is a clear and measurable decrease in the API peak (absorbance) without significant spectral interference from degradation products at the same λmax. Significant degradation was observed for candesartan under acidic, neutral, and oxidative conditions, demonstrating the method's ability to monitor instability [20]. Similarly, doxycycline hyclate showed significant degradation under alkaline, neutral, and oxidative stress [22].

The workflow below illustrates the logical sequence for developing and applying a UV-Vis method for drug assay and stability testing.

UV-Vis Method Development and Application Workflow

Case Studies and Data Presentation

Case Study 1: Stability-Indicating Assay of Candesartan Cilexetil

A study developed a simple and specific UV method for candesartan cilexetil in bulk and tablet dosage forms [20]. The method used methanol:water (9:1) as solvent with detection at 254 nm. The method was linear in the range of 10-90 µg/mL (R²=0.999) and showed recovery between 99.76-100.79%. The drug was subjected to forced degradation, and the order of degradation was found to be: Acidic > Neutral > Oxidative > Thermal > Alkaline > Photolytic > UV light [20]. This demonstrates the utility of UV-Vis in identifying an API's susceptibility to various stress conditions.

Case Study 2: Limitations in Complex Systems - Levofloxacin Analysis

A comparative study of levofloxacin analysis from a drug-delivery composite scaffold highlights a key limitation of UV-Vis. While both HPLC and UV-Vis showed excellent linearity (R² > 0.999), the recovery rates differed significantly [5]. For medium concentrations (25 µg/mL), HPLC showed a recovery of 110.96%, whereas UV-Vis showed 99.50% [5]. The study concluded that UV-Vis was inaccurate for this complex system due to interference from other scaffold components that co-dissolved and absorbed light, while HPLC successfully separated levofloxacin from these interferents [5].

Table 3: Quantitative Data from Levofloxacin Analysis Case Study [5]

| Method | Regression Equation | R² Value | Recovery at 25 µg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC | y = 0.033x + 0.010 | 0.9991 | 110.96% |

| UV-Vis | y = 0.065x + 0.017 | 0.9999 | 99.50% |

UV-Vis spectrophotometry remains a powerful and indispensable tool in the pharmaceutical analyst's toolkit. Its strengths of speed, simplicity, and low cost make it ideally suited for routine quality control of simple formulations, rapid assay during early development, and initial stability screening [11] [21]. The technique can be successfully validated as stability-indicating for APIs whose degradation products do not spectrally interfere [20] [22].

However, the choice of analytical technique must be guided by the sample's complexity and the required specificity. For complex mixtures, formulations with interfering excipients, or when precise impurity profiling is required, HPLC's superior separation power is unequivocally necessary [11] [5] [14]. Therefore, UV-Vis and HPLC should not be viewed as mutually exclusive but as complementary techniques, each fulfilling a critical role within a holistic pharmaceutical quality control strategy.

HPLC for Complex Mixtures, Impurity Profiling, and Stability-Indicating Methods

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is an indispensable tool in pharmaceutical development and quality control, providing unparalleled capability for separating, identifying, and quantifying chemical compounds in complex mixtures. The technique's exceptional resolving power, accuracy, and precision make it particularly valuable for analyzing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), their impurities, and degradation products [14]. In the context of a broader comparison with UV-Visible spectroscopy, HPLC offers distinct advantages for complex pharmaceutical analyses. While UV-Vis spectroscopy provides simple, rapid quantification of chromophoric compounds, it lacks the separating capability to distinguish individual components in mixtures without prior separation [24]. This fundamental difference positions HPLC as the superior technique for impurity profiling and stability-indicating methods where multiple chemically similar compounds must be resolved and quantified independently.

The application of reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) aligns particularly well with the hydrophobic nature of most small-molecule drugs, providing sufficient retention and mass balance for comprehensive purity assays [14]. When coupled with ultraviolet detection, HPLC leverages the chromophoric properties of pharmaceutical compounds—the same property exploited in UV-Vis spectroscopy—but adds the critical dimension of separation prior to detection. This combination enables precise quantification of both major components and trace-level impurities within a single analytical run. The five-order magnitude of linear UV response further enhances HPLC's utility, allowing convenient single-point calibration in stability-indicating assays while monitoring at the API's λmax provides specific and sensitive quantitation of related substances [14].

Fundamental Principles and Method Development

Core Components of an HPLC System

Modern HPLC systems comprise several integrated modules that must function harmoniously to achieve reliable results. The binary pump delivers precise mobile phase composition at flow rates typically ranging from 0.0001 to 10.000 mL/min with accuracy within ±1% and repeatability below 0.06% RSD [25]. The autosampler introduces reproducible sample volumes (typically 5-100 µL) into the flowing mobile phase, while the column oven maintains stable temperature conditions to ensure retention time reproducibility. The analytical column serves as the heart of the separation system, with reversed-phase C18 columns (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) being most common for pharmaceutical applications [25]. Finally, the UV detector monitors column effluent at specified wavelengths (often 230-254 nm for drugs with aromatic structures), generating signals proportional to analyte concentration.

Method Development Strategy

Developing a robust HPLC method requires systematic optimization of multiple parameters to achieve the desired separation. The process begins with column selection, where C18 stationary phases provide excellent versatility for small molecule pharmaceuticals. Mobile phase composition is then optimized through experimentation with aqueous-organic mixtures, typically using methanol-water or acetonitrile-water systems [25]. The addition of buffers or ion-pairing reagents may be necessary for ionizable compounds to improve peak shape and resolution. Flow rate optimization (commonly 0.8-1.5 mL/min for standard columns) balances analysis time against backpressure and resolution requirements. Temperature control (25-40°C) enhances reproducibility, while detection wavelength is selected based on the analyte's UV spectrum to maximize sensitivity for both the API and potential impurities.

Table 1: Optimized HPLC Conditions for Mesalamine Analysis

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Column | C18 (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) | Optimal balance of efficiency, backpressure, and separation |

| Mobile Phase | Methanol:Water (60:40 v/v) | Provides adequate retention and resolution of mesalamine from impurities |

| Flow Rate | 0.8 mL/min | Compromises analysis speed with column efficiency and backpressure |

| Detection Wavelength | 230 nm | Near λmax for mesalamine, providing good sensitivity |

| Injection Volume | 20 µL | Suitable for concentration range without column overloading |

| Column Temperature | Ambient (25±2°C) | Simplifies method transfer between laboratories |

| Run Time | 10 minutes | Balances throughput with sufficient separation |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

HPLC Method Validation Protocol

Once developed, HPLC methods must be rigorously validated to demonstrate suitability for their intended purpose. The International Council on Harmonization (ICH) guideline Q2(R2) provides the framework for validation parameters that must be assessed [25] [14]. The protocol below outlines the critical experiments and acceptance criteria for a stability-indicating HPLC method.

Linearity and Range: Prepare a minimum of five standard solutions across the specified range (e.g., 10-50 µg/mL for mesalamine) [25]. Inject each concentration in triplicate and plot peak area versus concentration. Calculate the regression line by least-squares method and determine the correlation coefficient (R²), which should be ≥0.999. The y-intercept should not differ significantly from zero, and residuals should be randomly distributed.

Accuracy (Recovery): Spike placebo matrix with known quantities of analyte at three concentration levels (80%, 100%, 120% of target) [25]. Prepare each level in triplicate and analyze using the validated method. Calculate percentage recovery for each level, which should be between 98.0-102.0% with RSD <2.0%. For the mesalamine method, recoveries of 99.05-99.25% with RSD <0.32% demonstrate excellent accuracy [25].

Precision: Assess both repeatability (intra-day precision) and intermediate precision (inter-day, inter-analyst, inter-instrument). Prepare six independent samples at 100% of test concentration and analyze in a single day. Repeat the study on a different day with different preparations. Calculate %RSD for peak areas and retention times, which should be <1.0% for intra-day and <2.0% for inter-day precision [25].

Specificity: Demonstrate that the method can unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of potential impurities, degradants, and matrix components. Inject blank (placebo), standard, stressed samples, and synthetic mixtures. Verify that the analyte peak is pure and free from interference using diode array detector peak purity assessment or mass spectrometric detection.

Detection and Quantitation Limits: Determine LOD and LOQ using signal-to-noise ratio method of 3:1 and 10:1, respectively. Alternatively, calculate based on standard deviation of the response and slope of the calibration curve. For the mesalamine method, LOD of 0.22 µg/mL and LOQ of 0.68 µg/mL were established [25].

Robustness: Deliberately introduce small variations in method parameters (flow rate ±0.1 mL/min, temperature ±5°C, mobile phase composition ±2% organic) and evaluate system suitability. The method should maintain adequate performance under all variations, with RSD <2% for peak areas and retention times [25].

Forced Degradation Studies Protocol

Forced degradation studies establish the stability-indicating properties of the method and reveal potential degradation pathways of the drug substance. These studies should be conducted under conditions that cause approximately 5-20% degradation to ensure sufficient degradation products are formed without over-stressing the sample [25].

Acidic Degradation: Treat drug solution with 0.1 N HCl at 25±2°C for 2 hours [25]. Neutralize with 0.1 N NaOH before analysis. This evaluates susceptibility to hydrolytic degradation under acidic conditions.

Alkaline Degradation: Treat drug solution with 0.1 N NaOH at 25±2°C for 2 hours [25]. Neutralize with 0.1 N HCl before analysis. This evaluates susceptibility to hydrolytic degradation under basic conditions.

Oxidative Degradation: Expose drug solution to 3% hydrogen peroxide at 25±2°C for 2 hours [25]. Directly analyze without neutralization. This assesses susceptibility to oxidative degradation pathways.

Thermal Degradation: Subject solid drug substance to dry heat at 80°C for 24 hours [25]. Dissolve in diluent and analyze. Evaluates thermal stability of the drug in solid state.

Photolytic Degradation: Expose solid drug to UV light at 254 nm for 24 hours according to ICH Q1B guidelines [25]. Dissolve in diluent and analyze. Determines photosensitivity of the drug substance.

For each stress condition, compare chromatograms with unstressed controls to identify degradation products. Confirm that the method resolves degradation products from the main peak and that mass balance (sum of analyte and degradation products) approaches 100%.

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Impurity Profiling

Impurity profiling represents one of the most critical applications of HPLC in pharmaceutical analysis, directly impacting drug safety and efficacy. Regulatory guidelines from ICH (Q3A, Q3B, Q3C, Q3D) and USP classify impurities into several categories requiring identification, qualification, and control [26]. HPLC provides the separating power necessary to resolve and quantify diverse impurity types within a single analysis.

Organic impurities include starting materials, intermediates, by-products, and degradation products that may arise during synthesis or storage. These represent the most diverse category and often require sophisticated chromatographic separation from the API and from each other. Inorganic impurities typically include catalysts, heavy metals, and other reagents, though these are more commonly analyzed by spectroscopic techniques. Residual solvents are volatile organic chemicals used in manufacturing, classified by ICH Q3C into Classes 1-3 based on toxicity [26].