Infrared Spectroscopy in Food Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control and Authenticity Testing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of infrared (IR) spectroscopy for ensuring food quality and authenticity.

Infrared Spectroscopy in Food Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to Quality Control and Authenticity Testing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of infrared (IR) spectroscopy for ensuring food quality and authenticity. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of IR spectroscopy, including Near-Infrared (NIR) and Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) techniques. It details methodological approaches for analyzing diverse food matrices—from plant-based beverages and spices to nuts and dairy—highlighting the critical role of chemometrics for data analysis. The content further addresses practical challenges and optimization strategies for method development and compares IR spectroscopy's performance against traditional analytical techniques, offering insights into its validation, accuracy, and growing potential in industrial and research settings.

The Science of Light: Foundational Principles of Infrared Spectroscopy in Food Analysis

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy has emerged as a cornerstone analytical technique for ensuring food quality, safety, and authenticity. This vibrational spectroscopy method analyzes the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter to reveal detailed information about molecular composition and structure. Within the food sector, two specific regions of the infrared spectrum are predominantly utilized: the Near-Infrared (NIR) and Mid-Infrared (MIR) regions. The application of these techniques is particularly valuable for addressing critical challenges in food analysis, including the detection of adulteration, confirmation of geographical origin, quantification of key components, and identification of contaminants. Unlike traditional wet chemistry methods which often require extensive sample preparation, hazardous chemicals, and significant time, IR spectroscopy offers a rapid, non-destructive, and environmentally friendly alternative [1] [2]. The integration of chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data—has further empowered researchers to extract meaningful information from complex spectral data, solidifying the role of IR spectroscopy as an indispensable tool in modern food science [2] [3].

Core Principles of Molecular Vibrations

The Physical Basis of Vibrational Spectroscopy

The fundamental principle underlying infrared spectroscopy is the absorption of specific frequencies of infrared light by chemical bonds within a molecule. This absorption occurs when the frequency of the incident IR radiation matches the natural vibrational frequency of a molecular bond, causing it to stretch, bend, or deform. The absorbed energy promotes the molecule to a higher vibrational energy state. The specific frequencies at which absorption occurs, measured in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹), provide a characteristic molecular fingerprint that is unique to the sample's chemical composition [4] [5].

Characteristic Vibrations in NIR and MIR

While both NIR and MIR spectroscopy probe molecular vibrations, they access different types of transitions, leading to distinct spectral information and applications.

Mid-Infrared (MIR) Spectroscopy operates in the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ (2.5–25 µm) and is concerned with the fundamental vibrations of molecular bonds. These include both stretching (symmetrical and asymmetrical) and bending (scissoring, rocking, wagging, twisting) motions. The MIR spectrum is divided into two key regions: the functional group region (4000–1300 cm⁻¹) and the fingerprint region (1300–600 cm⁻¹). The functional group region contains distinct absorption bands for key groups like O-H, N-H, and C-H, while the fingerprint region is characterized by complex, unique patterns resulting from coupled vibrations, allowing for precise material identification [4].

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy covers the range of 12,800–4000 cm⁻¹ (780–2500 nm). This region contains signals from overtones and combinations of the fundamental vibrations observed in the MIR region. Specifically, NIR spectra arise from the first, second, and third overtones of X-H stretching modes (where X is C, N, or O) and combination bands (e.g., stretching + bending). These transitions are weaker by an order of magnitude compared to fundamental bands, resulting in NIR spectra with broad, overlapping peaks that are highly complex and difficult to interpret visually without multivariate statistical tools [2] [3].

Table 1: Comparison of NIR and MIR Spectroscopy

| Feature | Near-Infrared (NIR) | Mid-Infrared (MIR) |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | 780–2500 nm (12,800–4,000 cm⁻¹) | 2.5–25 µm (4,000–400 cm⁻¹) |

| Vibrational Transitions | Overtones & combinations | Fundamental vibrations |

| Absorption Intensity | Weaker (10-100x less than MIR) | Stronger |

| Sample Penetration | Higher (several mm) | Lower (micrometers) |

| Typical Sampling | Diffuse reflection, transmission | ATR, Transmission, DRIFT |

| Primary Bonds Probed | C-H, O-H, N-H | C=O, O-H, N-H, C-O, C-H |

Spectral Interpretation and Data Analysis

Pre-processing of Spectral Data

Raw spectral data is often contaminated with noise and light scattering effects that can obscure chemical information. Therefore, data pre-processing is a critical first step in analysis.

- Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC): This is a model-based method that corrects for both additive and multiplicative effects commonly found in diffuse reflectance spectroscopy, effectively removing scattering artifacts [2].

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV): This technique centers and scales spectral data on a sample-by-sample basis, correcting for baseline shifts and path length variations [2].

- Savitzky-Golay Smoothing and Derivatives: This algorithm is widely used for smoothing spectra to reduce high-frequency noise. Its derivative function (first or second derivative) is applied to resolve overlapping absorption bands and correct baseline drift, though it may increase noise [2].

Chemometric Methods for Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

Due to the complexity of IR spectra, especially in NIR, chemometric tools are essential for extracting meaningful information.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): An unsupervised technique used for exploratory data analysis. PCA reduces the dimensionality of the spectral data, helping to identify patterns, groupings, or outliers without prior knowledge of sample classes [2] [6].

- Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR): A supervised method that is the workhorse for quantitative analysis. PLSR develops a model that finds the relationship between spectral data (X-matrix) and reference laboratory values (Y-matrix) for a constituent of interest (e.g., protein, moisture) [7] [2].

- Classification Methods (PLS-DA, SVM, Ensemble Learning): For qualitative analysis, such as authenticating origin or detecting adulteration, classification models are used. Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) is a linear classification method. More advanced non-linear methods like Support Vector Machine (SVM) and ensemble methods like Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM) can achieve higher accuracy for complex discrimination tasks [7] [6]. Ensemble learning, which combines multiple models, has shown great promise in improving predictive performance and robustness [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FT-NIR with Ensemble Learning for Detecting Contaminants in Oils

This protocol outlines the procedure for detecting mineral oil adulteration in corn oil using Fourier Transform Near-Infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopy coupled with interpretable ensemble learning models [7].

1. Reagent and Sample Preparation:

- Acquire pure food-grade corn oil and potential contaminants (e.g., diesel, kerosene, lubricating oil).

- Prepare adulterated samples by spiking pure corn oil with individual mineral oils at multiple concentration levels (e.g., 0.5%, 1%, 2%, 5% v/v).

- Ensure homogeneous mixing for each sample.

2. Spectral Data Acquisition:

- Use an FT-NIR spectrometer equipped with a transmission cell or an ATR accessory.

- Collect spectra in the range of 800–2500 nm (12,500–4,000 cm⁻¹).

- For each sample, acquire multiple scans (e.g., 32–64) and average them to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Maintain a constant temperature during measurement.

3. Data Pre-processing and Partitioning:

- Apply pre-processing techniques such as SNV, first derivative (Savitzky-Golay), or MSC to the raw spectra.

- Implement a clear data partitioning strategy. For each contamination level, randomly assign a portion of samples (e.g., 70%) to the training set for model development and the remainder (e.g., 30%) to the test set for validation.

4. Model Development and Validation:

- Develop a PLS-DA model as a baseline to screen contaminated vs. uncontaminated samples.

- Train ensemble learning models, such as LightGBM or Gradient Boosting Machine (GBM), to identify the specific type of contaminant.

- Optimize model hyperparameters using the training set via cross-validation.

- Validate the final model's performance on the untouched test set by evaluating metrics such as classification accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity.

5. Model Interpretation:

- Employ interpretation frameworks like SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) to identify the key spectral variables (wavelengths) that most significantly contribute to the model's predictions. This enhances trust in the model by providing insights into the chemical basis for the discrimination [7].

Protocol 2: Solvent-Based MIR for Authenticating Saffron

This protocol describes the use of solvent-based MIR spectroscopy for the geographical discrimination of saffron and detection of plant-based adulterants [6].

1. Metabolite Extraction:

- Follow a modified solvent extraction protocol based on the ISO 3632 standard for saffron.

- Use a Design of Experiments (DOE) approach to screen and optimize extraction parameters such as solvent type, extraction time, and temperature.

2. Spectral Acquisition with MIRA Analyzer:

- Utilize a dedicated MIR analyzer (e.g., MIRA) equipped with an ATR crystal.

- Place a droplet of the saffron extract onto the ATR crystal.

- Collect the MIR spectrum in the fingerprint region. Acquire multiple scans per sample to ensure representativeness.

3. Data Analysis for Geographical Discrimination:

- Perform exploratory data analysis using PCA to observe natural clustering of samples by origin.

- Develop a PLS-DA model using the MIR data to classify samples based on their geographical origin. Test different pre-processing methods (e.g., first derivative) to improve model performance.

- Alternatively, employ a Random Subspace Discriminant Ensemble (RSDE) model, which may achieve higher accuracy without intensive pre-processing.

4. Adulteration Detection and Identification:

- For adulterant detection, use a one-class model like Data-Driven Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (DD-SIMCA) to differentiate pure saffron from adulterated samples.

- To identify the type and level of specific adulterants (e.g., safflower, marigold), build a multi-class classification model using PLS-DA or RSDE. The RSDE model has been shown to outperform PLS-DA for this task [6].

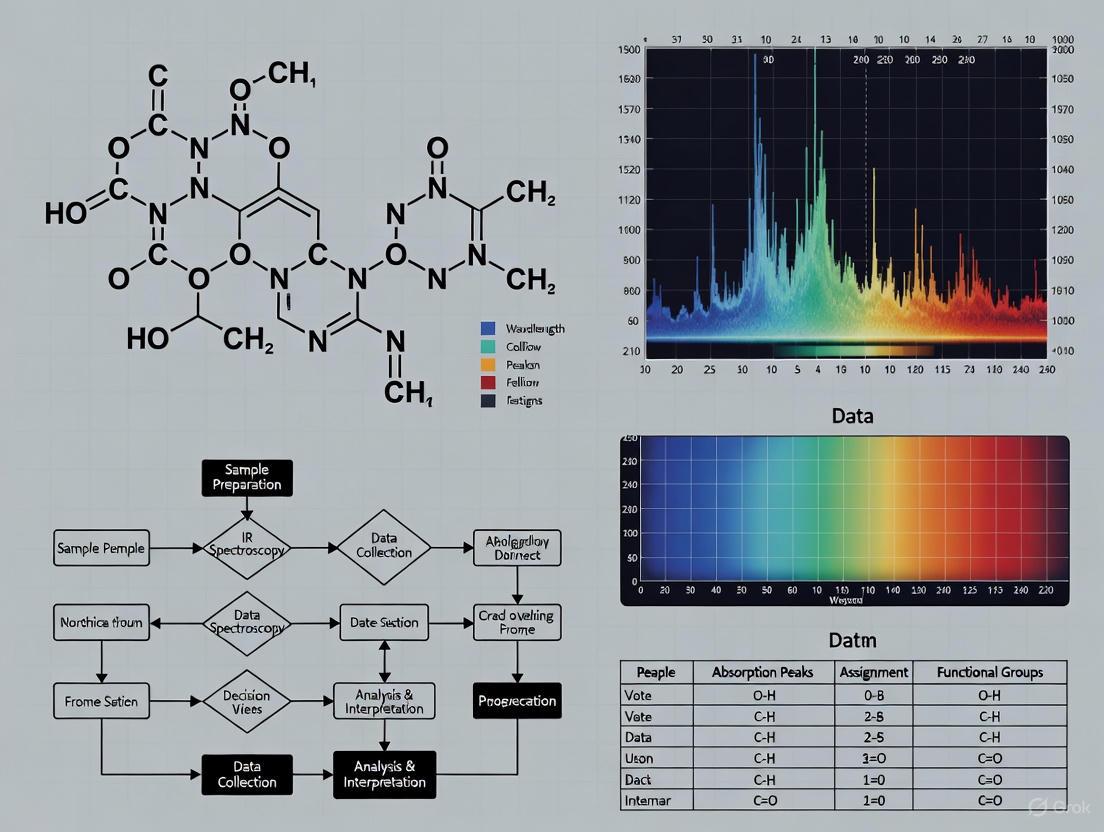

Diagram 1: MIR workflow for saffron authentication, covering origin and purity analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of IR spectroscopy for food analysis relies on a set of essential reagents, materials, and software tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item/Category | Function/Description | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| FT-NIR Spectrometer | Instrument for acquiring NIR spectra; often with fiber optic probes for flexible sampling. | Quantitative analysis of protein, moisture, fat in grains, milk [8] [2]. |

| FTIR Spectrometer with ATR | Instrument for acquiring MIR spectra; ATR accessory allows for minimal sample prep. | Detection of adulteration in oils, honey, dairy; saffron authentication [4] [6]. |

| Vibrational Probes (e.g., Azide, ¹³C, Deuterium) | Bioorthogonal tags used as metabolic probes to track specific pathways in complex systems. | Metabolic imaging in biological samples; tracking anabolism of specific nutrients [9]. |

| Chemometrics Software | Software for spectral pre-processing, multivariate calibration, and classification. | Developing PLSR models for quantification; PLS-DA for classification [7] [2]. |

| Reference Materials | Certified materials for instrument validation and calibration model development. | Ensuring accuracy of quantitative models for protein, fat, etc. [10]. |

Diagram 2: Universal chemometric workflow for processing NIR and MIR spectral data.

The core principles of molecular vibrations provide the foundation for understanding and applying NIR and MIR spectroscopy in food analysis. While MIR spectroscopy probes fundamental vibrations, offering detailed molecular fingerprints, NIR spectroscopy utilizes overtones and combinations for rapid, deep-penetration analysis of bulk constituents. The successful application of both techniques is inextricably linked to robust chemometric methods for spectral pre-processing and multivariate modeling. The presented experimental protocols and toolkit provide a practical framework for researchers to implement these powerful techniques. As the field advances, the integration of more sophisticated machine learning models and high-throughput imaging promises to further unlock the potential of infrared spectroscopy, solidifying its role as a green and efficient solution for ensuring food quality and authenticity.

The analysis of food quality and authenticity is a critical challenge in ensuring consumer safety and compliance with global regulatory standards. Infrared spectroscopy has emerged as a cornerstone analytical technique in this field, providing rapid, non-destructive assessment of food matrices. A significant evolution in this domain is the transition from traditional, laboratory-bound benchtop instruments to agile, portable spectrometers that enable analysis directly in the field and throughout the supply chain [11] [12]. This overview details the principles, capabilities, and applications of both benchtop Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) and portable Near-Infrared (NIR) spectrometers, providing a structured comparison and detailed experimental protocols for their application in food research.

Technical Foundations and Key Comparisons

Vibrational spectroscopy, including FTIR and NIR, operates on the principle of measuring the interaction between infrared light and matter. When molecules are exposed to infrared radiation, they absorb specific wavelengths that correspond to the energies of their chemical bonds' vibrational modes. This produces a spectral "fingerprint" unique to the sample's chemical composition.

Benchtop FTIR spectrometers typically utilize an interferometer and operate across the mid-infrared region (MIR, approximately 4000-400 cm⁻¹), which is rich in fundamental vibrational transitions and allows for highly specific compound identification [11] [13].

Portable NIR spectrometers operate in the near-infrared region (approximately 780-2500 nm), which encompasses overtone and combination bands of C-H, N-H, and O-H bonds. While these signals are broader and more complex to interpret, they are well-suited for quantitative analysis and require advanced chemometrics for deconvolution [14] [15]. The defining characteristic of portable NIR devices is their miniaturization, achieved through advancements in microelectro-mechanical systems (MEMS) and microelectronics, enabling their use outside traditional laboratories [12].

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of these two instrument classes.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Benchtop FTIR and Portable NIR Spectrometers

| Characteristic | Benchtop FTIR Spectrometer | Portable NIR Spectrometer |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Spectral Range | Mid-IR (4000 - 400 cm⁻¹) [13] | Near-IR (780 - 2500 nm) [14] [16] |

| Primary Analytical Strength | High specificity for compound identification [11] | Rapid quantification and classification [11] [15] |

| Throughput & Destructiveness | High-throughput; typically non-destructive [11] | Rapid; non-destructive [11] [14] |

| Portability & Use Case | Laboratory-bound; controlled environments | Handheld; on-site at farm, processing line, or market [15] [12] |

| Sample Preparation | Often required | Minimal to none [17] [16] |

| Spectral Resolution | High | Generally lower than benchtop systems [12] |

| Key Application Example | Detection of specific adulterants in oils [11] | Screening for pesticide residues on intact fruits [14] [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Detection of Pesticide Residues on Intact Fruits using Portable NIR

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating the quantification of pesticides like azoxystrobin and chlorpyrifos in cherry tomatoes and strawberries [14].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Acquire intact fruits (e.g., strawberries, tomatoes). For method development, use organically grown fruits to ensure no pre-existing pesticide residues.

- For calibration, prepare samples by spraying with pesticide solutions at different concentrations, reflecting the maximum residue limits (MRLs) and typical use patterns. Include a set of untreated control samples.

- Allow the sprayed samples to dry at room temperature before spectral acquisition.

2. Instrumentation and Spectral Acquisition:

- Device: Use a portable NIR spectrometer with a wavelength range of at least 900-1700 nm [14].

- Setup: Operate the device in reflectance mode. Ensure the device is calibrated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Measurement: Take multiple spectra from different positions on each fruit's surface to account for natural variability. A minimum of three scans per fruit is recommended. Ensure consistent contact or distance between the spectrometer's probe and the fruit surface.

3. Data Preprocessing:

- Convert raw reflectance spectra to absorbance (A = log(1/R)).

- Apply preprocessing techniques to minimize light scattering effects and enhance spectral features. Common methods include:

4. Chemometric Modeling and Validation:

- Model Development: Use the preprocessed spectra to build a quantification model.

- Recommended Algorithm: Orthogonal Projections to Latent Structures (OPLS) regression combined with variable selection methods (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination) has shown high predictive capacity (R²cv > 0.9) for this application [14].

- Validation: Split the dataset into a calibration (training) set and a validation (test) set. Validate model performance using cross-validation and external validation sets to report key metrics such as Root Mean Square Error of Cross-Validation (RMSECV) and the coefficient of determination for the prediction set (R²p) [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol.

Protocol 2: Authenticity Assessment and Adulteration Detection using Benchtop FT-NIR

This protocol is based on studies comparing benchtop and portable systems for detecting citric acid adulteration in lime juice [17].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare genuine juice samples using a cold press juicer.

- Homogenize the juices thoroughly using an ultra-turrax homogenizer to ensure spectral consistency.

- Prepare adulterated samples by adding exogenous citric acid to genuine juice at varying levels.

- For benchtop analysis, transfer the liquid sample into a standardized quartz cuvette with a fixed path length (e.g., 2 mm) [17].

2. Instrumentation and Spectral Acquisition:

- Device: Use a benchtop FT-NIR spectrometer, typically covering 1000-2500 nm [17].

- Setup: Calibrate the instrument using a built-in external reference (e.g., a background air scan or a certified reference standard) before each measurement session.

- Measurement: Acquire triplicate spectra for each sample in transmittance or diffuse reflectance mode, as appropriate. The high stability of the benchtop system allows for high-resolution scanning at a controlled temperature.

3. Data Preprocessing:

- Similar to Protocol 1, apply necessary preprocessing. For authenticity classification, Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) are highly effective for benchtop FT-NIR data [17].

4. Chemometric Modeling and Validation:

- Exploratory Analysis: Begin with Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to observe natural clustering and identify outliers.

- Discriminant Model: Use Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) to build a model that classifies samples as "genuine" or "adulterated." This model can achieve high accuracy (>94%) [17].

- Class-Modeling Approach: For authenticity problems, Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (SIMCA) is particularly powerful. It creates a model for the "genuine" class, and any sample that does not fit this model is flagged as atypical or adulterated. This approach has shown overall model performance of up to 98% for benchtop systems [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key materials and software solutions essential for conducting research in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Food Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Portable NIR Spectrometer (e.g., viavi MicroNIR, Thermo Fisher Phazir) | Handheld device for on-site, non-destructive spectral data collection on intact samples [12]. |

| Benchtop FT-NIR Spectrometer (e.g., Buchi N-500) | High-performance laboratory instrument for high-resolution spectral analysis of liquid and solid samples [17]. |

| Chemometrics Software (e.g., PLS_Toolbox, The Unscrambler) | Software for advanced multivariate data analysis, including PCA, PLS, OPLS, and machine learning algorithms [11] [12]. |

| Reference Analytical Standard (e.g., Certified Citric Acid) | Used for preparing calibration samples with known adulterant concentrations to build and validate predictive models [17]. |

| Ultra-Turrax Homogenizer | Ensures sample homogeneity, which is critical for obtaining reproducible and reliable spectra, especially for liquid and semi-solid matrices [17]. |

| Standardized Quartz Cuvettes | Provides a consistent and reproducible path length for liquid sample analysis in benchtop spectrometers [17]. |

Data Analysis and Chemometric Workflow

The powerful synergy between spectroscopy and chemometrics is what enables the extraction of meaningful information from complex spectral data. The process involves a logical sequence of steps, from raw data to actionable results, as illustrated below.

Key Chemometric Techniques:

- Data Preprocessing: Techniques like SNV and derivatives are crucial for removing physical light-scattering effects and enhancing chemical-related spectral features prior to modeling [14] [17].

- Exploratory Analysis (PCA): An unsupervised method used to visualize inherent data structure, identify patterns, clusters, and potential outliers without prior knowledge of sample classes [17] [12].

- Predictive Modeling: This includes both discriminant and class-modeling techniques.

- PLS-DA and OPLS: Supervised methods that maximize the separation between predefined sample classes (e.g., contaminated vs. clean). OPLS, in particular, separates the variation related to the predictive component from orthogonal (unrelated) variation, often leading to more interpretable models [14].

- SIMCA: A class-modeling technique that defines the boundaries of a target class (e.g., "authentic" honey). It is highly suited for authenticity testing as it can identify samples that do not belong to the target class, even if they are a new type of adulterant not seen before [17].

- Emerging Trends: The field is rapidly adopting data fusion (integrating data from multiple spectroscopic sources) and deep learning to model complex, non-linear relationships in data, further improving predictive accuracy and robustness [12].

The journey from benchtop FTIR to portable NIR spectrometers marks a paradigm shift in food quality and authenticity testing. Benchtop systems remain the gold standard for high-specificity identification in controlled laboratories, while portable NIR devices empower stakeholders with rapid, on-site screening capabilities. The effective application of both technologies is fundamentally dependent on robust chemometric models. Future directions point toward greater integration of these instruments with the Internet of Things (IoT), cloud computing, and advanced machine learning, paving the way for fully automated, intelligent decision-support systems that ensure food safety and integrity from farm to fork [15] [12].

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy has emerged as a cornerstone analytical technique for addressing critical challenges in food science, namely the assessment of authenticity, detection of adulteration, and evaluation of quality parameters. This family of techniques, which includes Near-Infrared (NIR) and Mid-Infrared (MIR) spectroscopy, along with Fourier-Transform IR (FT-IR) spectroscopy, is prized for its rapid, non-destructive, and green analytical capabilities [2] [18]. Its application is pervasive across the food industry and research sectors, enabling the swift monitoring of chemical composition without extensive sample preparation or the use of hazardous chemicals [19] [20]. When coupled with chemometrics, IR spectroscopy provides a powerful tool for the quantitative analysis of major constituents and the qualitative discrimination of food products based on their unique spectral fingerprints [2] [21]. These applications are vital for ensuring compliance with labeling regulations, protecting consumers from fraudulent practices, and maintaining brand integrity [22] [20]. This document outlines the key applications and provides detailed experimental protocols for implementing these techniques within a research context.

The following table summarizes the primary IR spectroscopy techniques used in food analysis, their principles, and their main applications in quality, authenticity, and adulteration testing.

Table 1: Overview of Infrared Spectroscopy Techniques in Food Analysis

| Technique | Spectral Range | Principle of Operation | Strengths | Common Food Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy [2] [18] | 750–2500 nm (12,500–4000 cm⁻¹) | Measures overtones and combinations of fundamental vibrations from C-H, N-H, and O-H bonds. | Rapid, high penetration depth, minimal sample preparation, suitable for online/at-line analysis. | Quantification of protein, moisture, fat, carbohydrates in grains, meat, dairy [2] [19]; Identification of origin; Adulteration screening. |

| Fourier-Transform Mid-Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy [23] [24] | 4000–400 cm⁻¹ | Measures fundamental molecular vibrations, providing detailed chemical structure information. | High specificity and information content; excellent for identifying functional groups and specific compounds. | Authentication of edible oils [23]; Detection of adulteration in honey, spices, milk [25] [22]; Analysis of physicochemical properties. |

| Raman Spectroscopy [25] | Varies (Laser-dependent) | Measures inelastic scattering of light, providing a vibrational fingerprint of the sample. | Minimal interference from water; provides complementary information to IR. | Detection of toxic substances, foodborne pathogens, and alcohol content in beverages [25]. |

Key Applications and Quantitative Data

The application of IR spectroscopy spans a vast array of food matrices. The table below compiles specific use cases and, where available, quantitative performance data from recent research.

Table 2: Key Applications and Performance of IR Spectroscopy in Food Testing

| Food Category | Analyte/Parameter of Interest | Technique Used | Key Findings & Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee [25] | Trace Elements (As, Pb, Cr, Zn, Fe, etc.) | ICP-OES | Successfully quantified 10 trace elements. Highest average concentration was Fe (498.72 ± 23.07 μg/kg). All samples were within safe limits. |

| Chicken Meat [25] | Geographical Origin | ICP-Based Methods | OPLS-DA model identified 23-28 significant elements for discrimination. Canonical discriminant analysis achieved 100% accuracy in classification. |

| Edible Oils [23] [22] | Authenticity & Adulteration | FT-IR | Successfully used to detect and quantify adulteration with lower-grade oils. Coupled with chemometrics for rapid, multi-parameter prediction. |

| Beverages & Spirits [25] | Ethanol & Toxic Alcohols (Methanol) | Raman Spectroscopy | Enabled rapid, non-destructive measurement through container. Applied for health safety and identifying adulteration. |

| Milk & Dairy [19] [26] | Fat, Protein, Lactose, Adulteration | FT-NIR / IR | Standard for rapid quantification of major components. Used for raw milk authentication by comparing spectral fingerprints to a known pure reference. |

| Grains & Flour [2] [20] | Protein, Moisture, Starch, Fiber | NIRS | Routine quality control. Diffuse reflectance mode used for solids/powders. Provides results in seconds for multiple parameters. |

| Fruits & Vegetables [18] [20] | Sugar (Brix), Ripeness, Internal Defects | NIRS (Interactance) | Non-destructive assessment of internal quality. Suitable for whole, intact produce. |

| Plastic Food Packaging [25] | Heavy Metals (Co, As, Cd, Pb, etc.) | ICP-MS | Method validated with LOD: 0.10–0.85 ng/mL; LOQ: 0.33–2.81 ng/mL. Migration of Zn, Al, and Pb into foodstuffs was confirmed. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: FT-IR Analysis for Edible Oil Authenticity

Application: Detection of adulteration in extra virgin olive oil [23] [22].

Principle: Adulterants (e.g., cheaper vegetable oils) introduce distinct chemical functional groups or alter the ratios of existing ones (e.g., C=O, C-H stretches), leading to detectable changes in the FT-IR spectrum.

Materials & Reagents:

- Pure, authenticated extra virgin olive oil reference samples.

- Test oil samples.

- FT-IR spectrometer with ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) accessory.

- Liquid sample cell or ATR crystal (e.g., diamond, ZnSe).

- Solvent (e.g., hexane) for cleaning; Lint-free wipes.

Procedure:

- Instrument Start-up: Power on the FT-IR spectrometer and allow it to stabilize for at least 15 minutes.

- Background Collection: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with solvent and dry. Collect a background spectrum of the clean crystal.

- Sample Loading: Apply a small drop of the pure reference oil or test oil directly onto the ATR crystal, ensuring full coverage of the crystal surface.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Acquire spectra in the range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹.

- Set resolution to 4 cm⁻¹ and accumulate 32–64 scans per spectrum to ensure a high signal-to-noise ratio.

- Replication: Analyze each sample in at least triplicate, cleaning the crystal between each measurement.

- Data Pre-processing: Export the averaged spectra and apply necessary pre-processing steps such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or derivative filters (e.g., Savitzky–Golay) to minimize baseline drift and scattering effects [2].

Data Analysis & Chemometrics:

- Qualitative Analysis (PCA): Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the pre-processed spectral data to observe natural clustering. Adulterated samples will appear as outliers or form separate clusters from the pure reference samples.

- Quantitative Analysis (PLSR): To quantify the level of adulteration, use Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR). Develop a calibration model by spiking pure oil with known concentrations of an adulterant and recording their spectra. The model correlates spectral changes with adulterant concentration, allowing for prediction in unknown samples [23].

Protocol 2: NIRS for Quantitative Analysis of Solid Food Powders

Application: Determination of protein, moisture, and fat in milk powder [19] [20].

Principle: Chemical bonds (O-H, N-H, C-H) in major food components absorb NIR light at specific wavelengths. The intensity of absorption is related to their concentration.

Materials & Reagents:

- Milk powder samples.

- NIR spectrometer equipped with a diffuse reflectance cup or spinning module.

- Standard laboratory reference methods (e.g., Kjeldahl for protein, loss on drying for moisture).

- Cuvettes or sample cups for powder analysis.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Ensure samples are homogeneous. For powders, consistent particle size is critical; grinding may be necessary. Allow samples to equilibrate to room temperature.

- Instrument Calibration: This is a critical one-time/periodic step. Analyze a large set (n > 50) of representative samples using both the NIR spectrometer and the standard reference methods.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Fill the sample cup consistently and evenly without compacting.

- Acquire spectra in the 800–2500 nm range.

- Use a rotating cup or collect multiple spectra from different spots to account for heterogeneity.

- Model Development: Use chemometric software to build a calibration model (typically using PLSR) that correlates the spectral data (X-matrix) with the reference analytical data (Y-matrix). Pre-process spectra using Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) or derivatives as needed [2].

- Validation: Validate the model using an independent set of samples not used in the calibration. Key performance metrics include Coefficient of Determination (R²), Standard Error of Prediction (SEP), and Residual Predictive Deviation (RPD).

Data Analysis: Once a robust calibration model is established and loaded into the instrument software, routine analysis involves simply acquiring the spectrum of an unknown sample, and the software instantly predicts the values for protein, moisture, fat, etc., based on the model.

Workflow Diagram: IR-Based Food Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for authenticity and quality control using IR spectroscopy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for IR-based Food Analysis

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose | Application Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FT-IR Spectrometer with ATR | Enables direct analysis of liquids, pastes, and solids with minimal preparation. | Authentication of oils, honey, and liquid dairy products [23] [22]. |

| NIR Spectrometer with Reflectance Probe | For non-destructive analysis of solid and powdered samples in lab or inline. | Analysis of grain, flour, and powdered milk in a production environment [19] [20]. |

| Chemometric Software Package | Critical for developing quantitative (PLSR) and qualitative (PCA, SIMCA) models from spectral data. | Open-source (R, Python) or commercial packages (OPUS, Unscrambler) are used [2] [18]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Used for instrument verification and as primary standards for calibration models. | NIST-traceable standards for protein, moisture, etc., to ensure model accuracy [25]. |

| Microfluidic Chips & SERS Substrates | Used with Raman spectroscopy to trap and enhance signal from specific analytes like pathogens. | Detection of foodborne pathogens; requires specific substrate functionalization [25]. |

| Solvents (Hexane, Ethanol) | For cleaning optics and ATR crystals between samples to prevent cross-contamination. | High-purity, spectroscopic grade is recommended to avoid introducing spectral artifacts. |

The global food supply chain faces increasing pressures from globalization, fraud, and stringent safety requirements, creating an urgent need for analytical techniques that are not only accurate but also rapid and adaptable. Traditional methods for ensuring food quality and authenticity, such as chromatography and DNA analysis, are often time-consuming, labor-intensive, and require destructive sampling, making them unsuitable for high-throughput or in-line monitoring [27]. Within this context, infrared (IR) spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful analytical tool to address these modern challenges. Techniques such as Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) and Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy provide rapid, non-destructive, and multi-parameter analysis, enabling real-time decision-making from "farm to fork" [28]. This Application Note details the implementation of IR spectroscopy, supported by specific protocols and data, for robust food quality and authenticity testing.

Application Notes: IR Spectroscopy in the Food Supply Chain

The application of IR spectroscopy, combined with chemometrics, allows for the extraction of critical information from complex food matrices. The following table summarizes its key capabilities:

Table 1: Key Applications of IR Spectroscopy for Food Analysis

| Application Focus | Analytical Capability | Example Use Case | Reference Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative Analysis | Measurement of beneficial components (proteins, polysaccharides, polyphenols) and fatty acids. | Online quantitative analysis of food components during processing. | NIR Spectroscopy [8] |

| Authenticity & Adulteration | Identification of mislabelling, dilution, or substitution with inferior substances. | Detection of adulterants in edible oils and identification of fraudulent substitution. | FT-IR Spectroscopy [23] |

| Origin & Provenance | Geographical traceability and verification of botanical/animal origin. | Tracing the geographic origin of milk and tea oil. | NIR Spectroscopy [3] |

| Microbiological Safety | Detection and identification of microbial contaminants. | Rapid screening for microbial contamination. | NIR Spectroscopy [8] |

| Process Monitoring | Real-time assessment of quality parameters during production. | In-line quality monitoring in commercial cheese production. | NIR Spectroscopy [28] |

Representative Data and Chemometric Analysis

The efficacy of IR spectroscopy is unlocked through chemometrics. The table below presents quantitative results from recent studies, demonstrating the predictive power of this combined approach.

Table 2: Representative Performance Data of NIR/FT-IR in Food Analysis

| Food Matrix | Analysis Type | Target Parameter/Class | Chemometric Model | Performance Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tea Oil | Geographical Traceability | Origin | CNN with Data Fusion | 98.75% Prediction Accuracy | [3] |

| Milk | Geographical Traceability | Origin | FDLDA-KNN Classifier | 97.33% Classification Accuracy | [3] |

| Peanut Oil | Adulteration Quantification | Adulterant Level | Partial Least Squares (PLS) | R² > 0.9311, RMSECV < 4.43 | [3] |

| Edible Oils | Free Fatty Acid (FFA) Determination | FFA Content | Differential FT-IR Spectroscopy | Quantitative analysis without titration | [29] |

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide detailed methodologies for two key applications of IR spectroscopy in food analysis.

Protocol: Detection of Edible Oil Adulteration using FT-IR Spectroscopy with ATR

Principle: This method uses Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FT-IR to detect and quantify adulterants in edible oils by identifying spectral changes associated with unauthorized additives [23]. The internal reflection element creates an evanescent wave that interacts with the sample, generating a molecular fingerprint.

Materials & Equipment:

- FT-IR Spectrometer equipped with an ATR accessory (e.g., Diamond or ZnSe crystal)

- Liquid sample cell (optional for transmission mode)

- Micro-pipettes and high-purity solvents (e.g., hexane) for cleaning

- Software for spectral collection and chemometric analysis

Procedure:

- Instrument Initialization: Power on the FT-IR spectrometer and allow it to stabilize. Purge the optical path with dry nitrogen to minimize spectral interference from atmospheric CO₂ and water vapor [29].

- Background Acquisition: Place a drop of pure solvent (or air for ATR) on the ATR crystal. Collect a background spectrum with the following parameters:

- Spectral Range: 4000 - 600 cm⁻¹

- Resolution: 4 - 8 cm⁻¹

- Number of Scans: 32 - 64 (optimize for signal-to-noise ratio)

- Sample Preparation & Loading:

- Ensure the ATR crystal is clean and dry.

- Pipette a small volume (e.g., 20-50 µL) of the pure (reference) oil or test sample directly onto the crystal, ensuring it covers the entire surface.

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Place the sample in contact with the ATR crystal. If specified, apply a consistent pressure using the instrument's pressure applicator to ensure good crystal-to-sample contact [30].

- Run the IR spectrum using the same parameters as the background acquisition.

- Post-Run Cleaning: Clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with an appropriate solvent and dry with a lint-free cloth before analyzing the next sample.

- Data Processing & Analysis:

- Process raw spectra using preprocessing techniques such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) to remove light scattering effects [3].

- For quantification (e.g., of adulterant level), develop a Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression model using calibration standards of known adulteration levels.

- For classification (authentic vs. adulterated), use methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA).

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of Liquid Food Components using NIR Spectroscopy

Principle: This protocol uses NIR spectroscopy for the rapid, non-destructive quantification of major components (e.g., fats, proteins, carbohydrates) in liquid foods like milk or fruit juices [3].

Materials & Equipment:

- NIR Spectrometer (Benchtop or portable, with a transmission or transflectance probe for liquids)

- Quartz cuvettes or disposable glass vials (pathlength 1-10 mm, depending on sample absorptivity)

- Temperature-controlled sample holder (recommended)

- Chemometric software

Procedure:

- System Setup: Stabilize the spectrometer and the sample temperature to a constant value (e.g., 25°C) to minimize spectral variance.

- Background Reference: Collect a background spectrum using an empty clean cuvette or a water blank, depending on the analysis.

- Sample Loading: Fill the cuvette with the homogeneous liquid sample, avoiding air bubbles.

- Spectral Collection: Place the cuvette in the sample holder and acquire the NIR spectrum. Typical parameters include:

- Wavelength Range: 780 - 2500 nm

- Resolution: 8 - 16 cm⁻¹

- Number of Scans: 16 - 32

- Calibration Model Development:

- Assemble a large set of samples (n > 50) covering the natural variability in the component of interest.

- Obtain reference values for the target component(s) using primary methods (e.g., Kjeldahl for protein).

- Preprocess spectra (e.g., Savitzky-Golay derivative, SNV) and use PLS regression to build a model correlating spectral data to reference values [3].

- Validate the model using an independent set of samples.

- Prediction: Apply the validated model to the spectra of unknown samples to predict their composition.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a food quality and authenticity analysis project using IR spectroscopy, from sample to result.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of IR-based methods relies on specific materials and software solutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for IR-based Food Analysis

| Item/Category | Function & Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | The internal reflection element in ATR sampling; enables direct analysis of solids and liquids with minimal preparation. | Analysis of viscous liquids (oils) and pastes. [29] |

| Chemometric Software | Software for multivariate data analysis, including preprocessing, PCA, PLS, and machine learning algorithms. | Developing quantitative and classification models for fraud detection. [27] [3] |

| NIR Calibration Standards | Certified reference materials for instrument validation and calibration transfer between devices. | Ensuring measurement consistency and accuracy in quantitative models. |

| Portable NIR Spectrometer | A handheld device for rapid, on-site screening at various points in the supply chain (e.g., warehouse, field). | Geographic origin verification of agricultural products. [3] |

| Spectroscopic Solvents | High-purity, spectroscopic-grade solvents (e.g., hexane, ethanol) for cleaning optical components and sample preparation. | Cleaning ATR crystals between samples to prevent cross-contamination. [31] |

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Applications Across Food Matrices

Infrared spectroscopy, particularly in the near-infrared (NIR) region, has established itself as a cornerstone technique for rapid, non-destructive analysis in food quality and authenticity testing [3] [32]. The spectral band of NIR typically covers 780 nm to 2500 nm, measuring the interaction between NIR radiation and chemical bonds in the sample, primarily those in hydrogen-containing groups (O-H, C-H, N-H) [3]. However, the resulting spectra are complex, characterized by broad, overlapping absorption bands that are difficult to interpret directly [3] [33]. This is where chemometrics transforms spectral data into actionable insight.

Chemometrics, defined as the mathematical extraction of relevant chemical information from measured analytical data, integrates theories from mathematics, statistics, and computer science to identify, quantify, and classify sample properties [3] [33]. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with classical chemometric methods represents a paradigm shift, enabling the analysis of complex, high-dimensional datasets that overwhelm traditional techniques [12] [34] [33]. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for utilizing Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, and machine learning for spectral analysis within food research.

Theoretical Foundations of Chemometric Techniques

Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

PCA is an unsupervised learning technique used for exploratory data analysis and dimensionality reduction [33]. It projects the original, potentially correlated spectral variables into a new set of orthogonal variables called Principal Components (PCs). The first PC captures the maximum variance in the data, with each subsequent component capturing the remaining variance in descending order. This allows for the visualization of sample clustering, identification of outliers, and detection of natural patterns within high-dimensional spectral data without prior knowledge of sample classes [33].

Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression

PLS regression is a supervised multivariate calibration method used to model the relationship between a spectral matrix (X) and a vector of concentration values or reference analyses (Y) [3] [35]. Unlike PCA, which only considers the variance in X, PLS finds latent variables that simultaneously maximize the covariance between X and Y. This makes it particularly powerful for predicting analyte concentrations in complex mixtures like foodstuffs, even in the presence of collinearity and noise [35] [36]. Key metrics for evaluating PLS models include the Coefficient of Determination (R²) and the Root Mean Square Error of Calibration (RMSEC) or Prediction (RMSEP) [36].

Machine Learning (ML) in Spectroscopy

Machine learning algorithms significantly expand the toolbox available for spectral analysis. They are particularly adept at handling non-linear relationships and automating feature extraction [34] [33].

- Support Vector Machine (SVM): A supervised algorithm that finds the optimal hyperplane to separate classes or predict quantitative values in high-dimensional space. It is effective for classification and regression tasks, especially with limited samples [33].

- Random Forest (RF): An ensemble method that constructs multiple decision trees and aggregates their results. It offers strong generalization, reduces overfitting, and provides feature importance rankings [34] [33].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): A class of deep learning models capable of automatically learning hierarchical features from raw or minimally preprocessed spectral data, often achieving state-of-the-art performance in classification and quantification tasks [34] [33].

Application Notes: Chemometrics in Food Quality and Authenticity

The following table summarizes selected recent applications of chemometric techniques in food analysis, demonstrating their performance across various matrices and challenges.

Table 1: Applications of Chemometric Techniques in Food Analysis

| Food Matrix | Analytical Challenge | Chemometric Technique(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Reference Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tiger Nut (Cyperus esculentus L.) | Quantification of crude oil, protein, and starch | PLSR with variable selection | R²: 0.8946 (oil), 0.8525 (protein), 0.8778 (starch) | [36] |

| Honey | Authentication & detection of adulteration | PCA, PLSR, Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) | Classification accuracy >90% for adulteration | [35] |

| Plant-Based Milk Alternatives | Classification and detection of variability | PCA, Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) | Successful discrimination of almond, oat, rice, and soy drinks | [37] |

| Milk | Geographical origin traceability | Portable NIR with Fuzzy Direct LDA-KNN | Classification accuracy of 97.33% | [3] |

| Peanut Oil | Identification of adulteration | PLS Modeling | R² > 0.9311, low RMSECV | [3] |

| Powdered Foods (spices, dairy, cereals) | Adulterant detection | SVM, Random Forest, Deep Learning | Detection accuracy often >90% | [38] |

Workflow for Spectral Analysis

A robust chemometric analysis follows a structured workflow from spectral acquisition to model deployment. The following diagram illustrates the key stages, highlighting the iterative nature of model development and validation.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantification of Nutrient Composition in Tiger Nuts using PLSR

Objective: To rapidly and non-destructively predict the content of crude oil (CO), crude protein (CP), and total starch (TS) in tiger nut tubers using a portable NIR spectrometer and PLSR [36].

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Portable NIR Spectrometer | Acquisition of spectral data from samples. | IAS8120 (Range: 800-1100 nm or broader) [36] |

| Tiger Nut Samples | Representative sample set for calibration and validation. | 75 samples, 28 varieties, multiple regions [36] |

| Reference Chemistry: Soxhlet Apparatus | Determination of reference crude oil content for model calibration. | Standard solvent extraction [36] |

| Reference Chemistry: Kjeldahl Apparatus | Determination of reference crude protein content for model calibration. | Measures nitrogen content [36] |

| Reference Chemistry: Spectrophotometer | Determination of reference total starch content for model calibration. | Dual-wavelength colorimetric method [36] |

| Data Analysis Software | For spectral preprocessing, variable selection, and PLSR modeling. | Python, R, MATLAB, or commercial chemometrics software |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Wash fresh tiger nut tubers and air-dry to a stable moisture content (~10%). Grind the dried tubers and sieve through a 30-mesh screen. Store prepared powder at 4°C [36].

- Reference Analysis: Determine the CO, CP, and TS content for each sample using standard chemical methods (Soxhlet extraction, Kjeldahl, and spectrophotometry, respectively). These values form the reference (Y-block) for the PLSR model [36].

- Spectral Acquisition: Using the portable NIR spectrometer, collect the spectra of all powdered samples. Ensure consistent scanning parameters and environmental conditions. The resulting spectra form the predictor matrix (X-block) [36].

- Spectral Preprocessing: Apply preprocessing techniques to minimize light scattering and noise. Common methods include:

- Variable Selection (Optional but Recommended): To improve model performance, employ algorithms like Interval Partial Least Squares (iPLS) or Moving Window PLS (MWPLS) to select spectral regions most informative for the specific component being analyzed [36].

- Model Development & Validation:

- Split the dataset into a calibration set (e.g., 70-80% of samples) and a validation set (20-30%).

- Build the PLSR model on the calibration set, correlating the preprocessed spectra (X) with the reference values (Y).

- Use leave-one-out or cross-validation on the calibration set to determine the optimal number of latent variables and prevent overfitting.

- Validate the model by predicting the component values in the independent validation set. Calculate performance metrics: R² and RMSEP [36].

Protocol 2: Authentication of Honey and Detection of Adulteration

Objective: To use NIR spectroscopy combined with chemometrics to verify honey authenticity, classify botanical origin, and detect adulterants like corn or rice syrup [35].

Materials and Reagents:

- NIR Spectrometer (benchtop or portable with InGaAs detector)

- Pure and Adulterated Honey Samples

- Liquid Sample Cell or Transflectance Probe

- Chemometrics Software with PCA, PLS-DA, and LDA algorithms.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Ensure honey samples are well-mixed and free of air bubbles. Warm crystallized samples gently in a water bath (not exceeding 40°C) to liquefy, then homogenize. Allow samples to equilibrate to room temperature (e.g., 25°C) before analysis [35].

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect NIR spectra of all honey samples using a transmission or transflectance cell. A wavelength range of 1000-2500 nm is typical. For each sample, collect multiple scans and average them to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [35].

- Data Preprocessing: Apply standard preprocessing techniques to the raw spectra. Common choices for honey include:

- Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) or SNV to compensate for path length differences and scattering.

- Savitzky-Golay First or Second Derivative to enhance spectral features and remove baseline offsets [35].

- Exploratory Analysis (PCA): Perform PCA on the preprocessed spectral data. Examine the scores plot (e.g., PC1 vs. PC2) to visualize natural clustering of samples, identify potential outliers, and observe any separation between pure and adulterated samples or between different floral origins [35].

- Classification Model:

- For Adulteration Detection: Use a classification algorithm like Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the principal components from PCA to build a model that classifies samples as "pure" or "adulterated" [35]. Alternatively, use PLS-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) or Support Vector Machine (SVM) directly on the spectra.

- For Quantifying Adulteration: If the goal is to predict the level of an adulterant, develop a PLSR model using reference values for the adulterant concentration.

- Model Validation: Validate the classification model using an external test set or cross-validation. Report classification accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. For quantitative PLSR models, report R² and RMSEP [35].

The Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Future Directions

The field is rapidly evolving with the integration of advanced machine learning and AI, moving beyond classical chemometrics. The following diagram illustrates how AI is being integrated into modern spectroscopic workflows.

Key emerging trends include:

- Explainable AI (XAI): Addressing the "black box" nature of complex models like deep learning by providing insights into which spectral regions drive predictions, building trust and providing chemical insight [34] [33].

- Data Fusion: Combining data from multiple spectroscopic sensors (e.g., NIR, Raman, MIR) using low-, mid-, or high-level fusion strategies to create more robust and informative models [12].

- Miniaturization and Portability: The development of handheld and portable spectrometers, coupled with robust chemometric models, enables real-time, on-site analysis throughout the food supply chain [12] [32].

- Self-Adaptive Models and Multi-Omics Integration: Future frameworks may involve models that continuously learn from new data. Furthermore, using AI to fuse spectral data with other 'omics' data (genomics, proteomics) promises a more holistic understanding of food quality and authenticity [34] [38].

In the rapidly expanding plant-based food sector, product authentication and quality control have become paramount for consumer protection and regulatory compliance. This case study details the application of Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy for authenticating commercial plant-based milk substitutes. Framed within broader thesis research on infrared spectroscopy for food quality and authenticity testing, this work demonstrates how ATR-FTIR, combined with chemometric analysis, provides a rapid, non-destructive method for classifying plant-based beverages and detecting potential adulteration or compositional variability.

The global market for plant-based milk alternatives has experienced remarkable growth, with per capita revenue expected to increase by approximately 127% from 2014 to 2027 [37]. This surge, driven by environmental concerns, health considerations, and dietary preferences, has created an urgent need for analytical methods to verify product authenticity and compositional integrity [37]. Plant-based beverages derived from almonds, oats, rice, and soy exhibit distinct biochemical profiles that serve as chemical fingerprints for authentication purposes [39].

Theoretical Background

ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy Fundamentals

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy leverages the interaction between infrared radiation and molecular bonds in a sample to produce characteristic spectral fingerprints. When IR light interacts with a sample placed on a crystal with a high refractive index, it undergoes total internal reflection, generating an evanescent wave that penetrates the sample typically to a depth of 0.5-5 micrometers. Molecular bonds within the sample absorb specific frequencies of this radiation, resulting in absorption bands that correspond to the sample's chemical composition [40].

The resulting spectrum provides a comprehensive molecular fingerprint of the sample, with absorption bands representing specific molecular vibrations from functional groups present in proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and other constituents. For plant-based milk authentication, the Amide I and II regions (1700-1600 cm⁻¹ and 1600-1500 cm⁻¹) are particularly important for protein characterization, while the carbohydrate region (1200-900 cm⁻¹) provides information about sugar and fiber content [37] [39].

Chemometrics in Spectral Analysis

Chemometrics applies statistical and mathematical methods to extract meaningful information from chemical data. When applied to complex ATR-FTIR spectral data, chemometric techniques enable:

- Pattern recognition for sample classification

- Discrimination between categories based on compositional differences

- Quantification of specific components in complex mixtures

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) reduces the dimensionality of spectral data while preserving variance, allowing visualization of natural clustering between sample classes. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) groups samples based on spectral similarity, while Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA) and Orthogonal PLS-DA (OPLS-DA) build predictive models for classification [37] [39].

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation

Table 1: Sample Preparation Protocol for Plant-Based Milk Analysis Using ATR-FTIR

| Step | Procedure | Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Acquisition | Purchase commercial plant-based beverages from retail markets | Include multiple brands and batches for each beverage type (almond, oat, rice, soy) | Ensure representative sampling of commercial products |

| Lyophilization | Freeze samples at -80°C for 3 days, then lyophilize | Vacuum: 0.80 mbar; Temperature: -25°C until completely dehydrated [39] | Remove water interference from spectra; preserve macronutrient structure |

| Homogenization | Gently mix or vortex samples before analysis | Ensure uniform distribution of components | Improve spectral reproducibility |

Sample preparation is critical for obtaining high-quality, reproducible ATR-FTIR spectra. Lyophilization eliminates the strong infrared absorption of water, which can obscure important spectral regions, particularly the Amide I region crucial for protein secondary structure analysis [39]. The freeze-drying process preserves the native structure of macromolecules, ensuring that spectral features accurately represent the beverage's composition.

ATR-FTIR Spectral Acquisition

Table 2: Instrumental Parameters for ATR-FTIR Spectral Acquisition

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument | FTIR Spectrometer with ATR accessory | Standard equipment for solid and liquid sample analysis |

| ATR Crystal | Diamond internal reflection element | Durability and chemical resistance; suitable for diverse samples |

| Spectral Range | 4000-400 cm⁻¹ | Covers fundamental molecular vibration regions |

| Resolution | 4 cm⁻¹ | Optimal balance between spectral detail and signal-to-noise ratio |

| Scan Number | 20-100 scans per sample | Improve signal-to-noise ratio through averaging |

| Background Correction | Before each sample or sample set | Minimize atmospheric interference (CO₂, H₂O vapor) |

Spectral acquisition follows a standardized protocol: (1) Clean the ATR crystal with appropriate solvents and dry; (2) Collect background spectrum; (3) Apply lyophilized sample to completely cover the crystal surface; (4) Apply consistent pressure using the instrument's pressure clamp; (5) Collect sample spectra; (6) Clean crystal thoroughly between samples [39]. Most studies employ 20-100 scans per sample to ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio while maintaining practical analysis time.

Data Pre-processing and Chemometric Analysis

Raw spectral data requires pre-processing to remove instrumental artifacts and enhance chemical information before chemometric analysis:

- ATR Correction: Compensates for depth of penetration variation with wavelength

- Baseline Correction: Removes scattering effects and baseline drift

- Normalization: Standardizes spectral intensity for comparative analysis (typically Min-Max or Standard Normal Variate)

- Smoothing: Reduces high-frequency noise (Savitzky-Golay filter commonly used)

- Derivative Analysis: Second-derivative transformation enhances resolution of overlapping bands, particularly in the Amide I region for protein secondary structure analysis [39]

Following pre-processing, both unsupervised (PCA, HCA) and supervised (PLS-DA, OPLS-DA) chemometric methods are applied to classify samples and identify discriminatory spectral features.

Key Experimental Findings

Spectral Features for Classification

Table 3: Characteristic ATR-FTIR Spectral Regions for Plant-Based Milk Authentication

| Spectral Region (cm⁻¹) | Molecular Assignment | Discriminatory Utility | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3000-2800 | C-H stretching (lipids, fatty acids) | Differentiation based on lipid profiles | Variations in almond beverages due to different lipid content [37] |

| 1700-1600 (Amide I) | C=O stretching (proteins) | Protein secondary structure quantification | β-turn and α-helix structures key for discrimination [39] |

| 1600-1500 (Amide II) | N-H bending, C-N stretching (proteins) | Protein content and characteristics | Soy beverages show distinct protein profile [39] |

| 1200-900 | C-O-C, C-O stretching (carbohydrates) | Carbohydrate profile differentiation | Distinguishes oat (β-glucans) and rice (high sugar) beverages [37] [39] |

Research demonstrates that ATR-FTIR spectroscopy effectively discriminates between different types of plant-based beverages. In a comprehensive study analyzing 41 commercial beverages, soy and rice beverages formed distinct clusters in chemometric models, while almond and oat samples showed partial overlap due to greater compositional variability [39]. Variable Importance in Projection (VIP) scores from OPLS-DA models identified β-turn and α-helix protein structures, along with carbohydrate-associated spectral bands, as the most significant features for classification [39].

Challenges in Almond Beverage Authentication

Almond-based beverages present particular challenges for authentication due to their significant compositional variability. ATR-FTIR studies have revealed that almond beverages often demonstrate less precise clustering in chemometric models compared to oat, rice, and soy beverages [37]. This variability frequently stems from the inclusion of other ingredients like rice or soy as fillers or stabilizers, which can mislead consumers about nutritional content [37]. The ATR-FTIR method successfully detects this variability, with models accurately identifying almond beverages containing substantial amounts of rice or soy components.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ATR-FTIR Analysis of Plant-Based Milks

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectrometer | Equipped with ATR accessory (diamond crystal recommended) | Spectral acquisition from plant-based milk samples |

| Lyophilizer | Capable of reaching -80°C and 0.80 mbar vacuum | Sample dehydration to remove water interference |

| Chemometrics Software | MATLAB, Python with scipy.stats, or dedicated spectral analysis packages | Multivariate data analysis and classification model development |

| Reference Materials | Pure plant sources (almond, oat, rice, soy) | Method validation and calibration standards |

| Crystal Cleaning Solvents | HPLC-grade solvents (e.g., methanol, ethanol) | ATR crystal cleaning between samples to prevent cross-contamination |

Implementation Workflows

Experimental Workflow

Experimental workflow for plant-based milk authentication

Data Analysis Pathway

Data analysis pathway for spectral interpretation

ATR-FTIR spectroscopy combined with chemometric analysis represents a powerful, rapid, and non-destructive approach for authenticating plant-based milk alternatives. The method successfully discriminates between beverage types based on their unique biochemical fingerprints, with particular effectiveness in identifying protein secondary structures and carbohydrate profiles as key discriminatory features.

Implementation of this analytical approach addresses growing concerns about product authenticity in the expanding plant-based food sector, providing manufacturers, regulators, and researchers with a reliable tool for quality control and verification of label claims. The portability of modern ATR-FTIR instruments further enhances their potential application in various settings, from research laboratories to industrial quality control environments [37].

Future developments in spectral database creation, calibration transfer protocols, and advanced machine learning applications will further strengthen the role of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy in ensuring transparency and authenticity throughout the plant-based food supply chain.

Food fraud represents a significant global challenge to food safety, consumer health, and economic stability, with estimated annual economic losses of $40 billion affecting approximately 16,000 tons of food and beverages [38]. Adulteration manifests in three primary dimensions: intentional, accidental, and falsified [38]. Intentional adulteration includes substituting premium ingredients with cheaper alternatives, such as adding ground nutshells to cinnamon or starches to protein supplements [38]. This case study explores the application of Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, specifically Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, as a rapid, non-destructive analytical tool for detecting adulteration across three vulnerable food categories: spices, nuts, and liquid foods. Framed within broader thesis research on IR spectroscopy for food quality and authenticity testing, this study provides detailed protocols and data interpretation frameworks suitable for researchers, scientists, and quality control professionals engaged in food fraud mitigation.

Theoretical Foundations of NIR Spectroscopy

Near-Infrared spectroscopy operates in the electromagnetic spectrum range of 800–2500 nm (12,500–4000 cm⁻¹), situated between the visible and mid-infrared regions [41]. This technique measures molecular overtone and combination vibrations, primarily involving C-H, O-H, and N-H chemical bonds [2] [35]. These vibrations provide a unique chemical "fingerprint" for each sample, enabling discrimination between authentic and adulterated products [42].

The interaction between NIR light and matter follows the Beer-Lambert law, where absorbance is proportional to both concentration and optical path length [38]. NIR systems typically comprise a radiation source, sample cell, and detector, with measurements acquired through diffuse reflectance for solids (e.g., spices, nut powders) or transmission/transflectance for liquids (e.g., honey, oils) [38] [2]. The technique's significant advantages include minimal sample preparation, rapid analysis (seconds to minutes), and simultaneous multi-component determination without consuming or altering samples [2] [35].

Despite these advantages, NIR spectroscopy faces limitations including low sensitivity for compounds present at concentrations below 1%, susceptibility to environmental factors (e.g., temperature, moisture), and the necessity for robust calibration models using chemometrics [38] [2]. These limitations underscore the critical importance of proper experimental design and model development, as detailed in subsequent sections.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of NIR Spectroscopy for Food Authentication

| Characteristic | Description | Implication for Food Authentication |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | 800–2500 nm | Captures overtone and combination vibrations of organic compounds |

| Key Molecular Vibrations | C-H, O-H, N-H bonds | Sensitive to major food components (proteins, fats, carbohydrates, water) |

| Sample Forms | Solids, liquids, powders | Applicable to diverse food matrices without extensive preparation |

| Analysis Speed | Seconds to minutes | Suitable for high-throughput screening and real-time decision making |

| Detection Limits | Typically >0.1–1% | Effective for economically-motivated adulteration at commercially relevant levels |

| Destructive | Non-destructive | Preserves sample for further testing or legal proceedings |

Experimental Design and Workflow

A systematic approach to NIR-based adulteration detection ensures reliable, reproducible results. The following workflow diagram illustrates the comprehensive process from sample preparation to final authentication decision:

Sample Preparation Protocol

For Spices and Nut Powders:

- Grinding: Process samples to uniform particle size using a laboratory mill (e.g., 250–500 μm) to minimize light scattering effects [38].

- Moisture Standardization: Condition samples in a controlled environment (relative humidity 40–50%, 25°C) for 24 hours to reduce spectral variability from water content differences [38].

- Packaging: Present samples in uniform containers with consistent geometry and packing density for reflectance measurements [38].

For Liquid Foods (Honey, Oils, Milk):

- Homogenization: Mix samples thoroughly to ensure uniform distribution of components [35].

- Temperature Equilibration: Standardize sample temperature to 25±1°C to minimize spectral effects from temperature variation [35].

- Cell Selection: Use transmission cells with appropriate path lengths (0.5–2 mm) for liquids, or transflectance cells for viscous samples [2].

Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

Equipment Setup:

- NIR Spectrometer: Benchtop (laboratory) or portable (field) devices covering 1000–2500 nm range [41] [42].

- Detector Type: InGaAs for higher wavelength sensitivity (1100–2500 nm), PbS for diffuse reflectance of solids [2].

- Acquisition Mode: Diffuse reflectance for powdered spices/nuts; transmission for clear liquids; transflectance for viscous liquids [38] [2].

Spectral Collection Parameters:

- Spectral Range: 1000–2500 nm for comprehensive chemical information [35].

- Resolution: 4–16 cm⁻¹ for optimal feature detection [35].

- Scan Number: Minimum 32 scans per spectrum to ensure adequate signal-to-noise ratio [41].

- Replication: Analyze at least 5–10 subsamples per specimen to account for heterogeneity [38].

Spectral Preprocessing and Chemometric Analysis

Spectral Preprocessing Techniques

Raw NIR spectra contain both chemical and physical information, necessitating preprocessing to enhance chemical signals while minimizing confounding physical effects (e.g., light scattering, particle size variation). The table below summarizes common preprocessing techniques and their applications:

Table 2: Spectral Preprocessing Techniques for NIR Analysis of Foods

| Technique | Primary Function | Typical Applications | Effect on Spectra |

|---|---|---|---|

| Savitzky-Golay (SG) Smoothing | Reduces high-frequency noise | All sample types; essential before derivative processing | Improves signal-to-noise ratio without significant peak distortion [38] |

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) | Corrects for scattering effects | Powdered spices, nut flours, uneven surfaces | Removes multiplicative interferences and baseline shifts [38] [2] |

| Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) | Compensates for additive and multiplicative scattering | Heterogeneous solid samples | Linearizes reflectance spectra, enhancing chemical information [2] |

| First Derivative (FD) | Eliminates baseline offset and enhances resolution | Overlapping peaks; subtle spectral features | Emphasizes minor spectral variations; requires subsequent smoothing [38] [2] |

| Second Derivative (SD) | Enhances peak resolution and class discrimination | Complex mixtures with overlapping absorptions | Improves separation of closely spaced peaks; increases noise [38] |

Chemometric Modeling Approaches

Chemometrics applies statistical methods to extract meaningful information from chemical data. For NIR-based authentication, both unsupervised and supervised approaches are employed:

Exploratory Analysis (Unsupervised):

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Reduces spectral dimensionality while preserving variance, enabling visualization of natural sample clustering and outlier detection [41] [2]. PCA is particularly valuable for initial data exploration to identify patterns and potential adulteration trends without prior class information.

Classification and Regression (Supervised):

- Partial Least Squares-Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA): A discriminant version of PLS that maximizes separation between predefined classes (e.g., authentic vs. adulterated) [41].

- Soft Independent Modeling of Class Analogy (SIMCA): A class modeling technique that develops a separate PCA model for each class, useful for verifying sample conformity to a target class (e.g., pure spice) [43].

- Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR): Establishes relationship between spectral data and continuous reference values (e.g., adulteration percentage), enabling quantitative prediction [2] [35].

Model Validation: Robust validation is essential to ensure model reliability. Employ:

- Cross-validation: Internal validation (e.g., venetian blinds, random subsets) to optimize model complexity and prevent overfitting [41].

- External validation: Testing with completely independent sample sets not used in model development [35].

- Performance metrics: For classification: sensitivity, specificity, accuracy; for regression: RMSECV, RMSEP, R² [2].

Application-Specific Protocols and Data Interpretation

Spice Authentication

Spices represent a high-risk category for adulteration due to their high value and complex supply chains. Common adulterants include spent spice material, foreign plant matter, synthetic dyes, and hazardous substances like Sudan dyes [41] [42].

Experimental Protocol for Black Pepper Authentication:

- Reference Samples: Collect 50 authenticated black pepper samples from verified sources.

- Adulterated Samples: Prepare adulterated samples by mixing authentic pepper with pepper husks, starch, or spent pepper in 5–40% (w/w) increments.

- Spectral Acquisition: Use diffuse reflectance mode with benchtop NIR spectrometer (1000–2500 nm, 8 cm⁻¹ resolution, 64 scans).