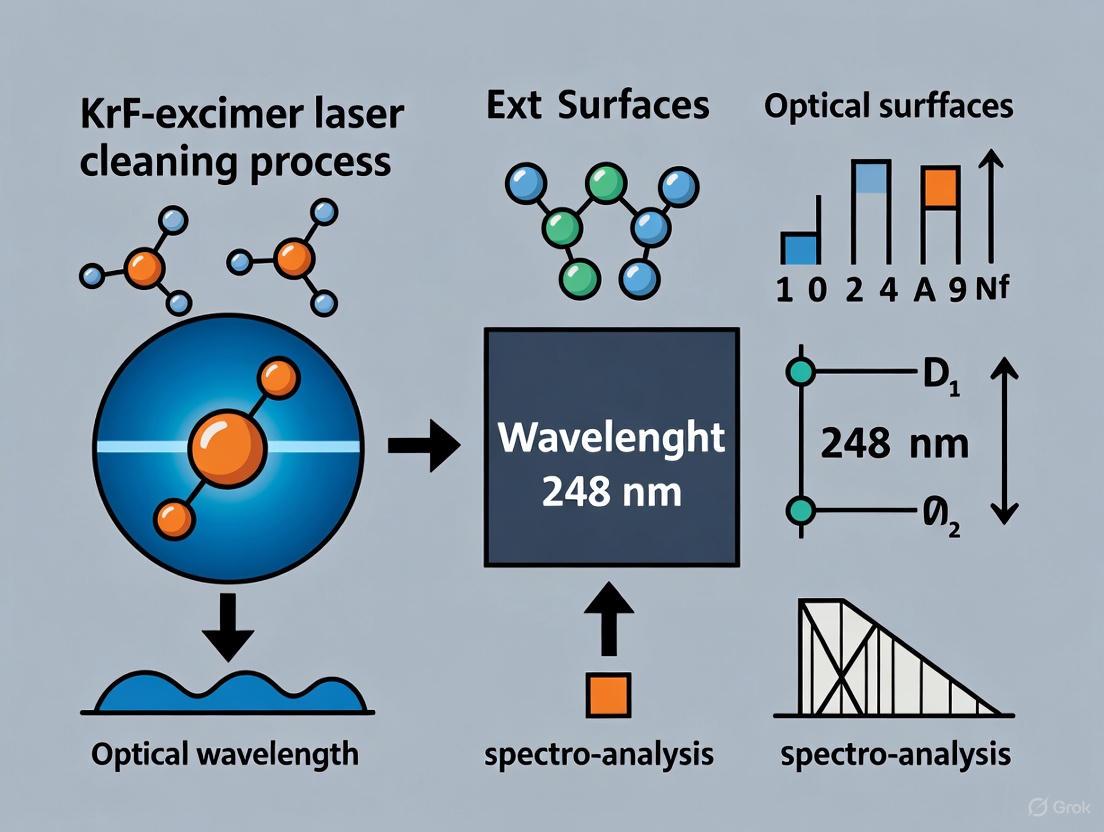

KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning at 248 nm: Mechanisms, Applications, and Optimization for Optical Surfaces

This article provides a comprehensive examination of KrF excimer laser cleaning at a wavelength of 248 nm, a advanced technique for the precise and controlled removal of contaminants, coatings, and...

KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning at 248 nm: Mechanisms, Applications, and Optimization for Optical Surfaces

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of KrF excimer laser cleaning at a wavelength of 248 nm, a advanced technique for the precise and controlled removal of contaminants, coatings, and particulates from sensitive optical surfaces. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and development professionals, the content spans from foundational principles and cleaning mechanisms to specific methodological applications across diverse materials. It delivers a thorough guide for troubleshooting and optimizing laser parameters to ensure efficacy and prevent substrate damage, supported by validation through modern analytical techniques and comparisons with traditional cleaning methods. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to implement this non-contact, environmentally friendly technology effectively in research and high-tech industrial settings.

Unveiling the Principles: How 248 nm KrF Laser Light Interacts with Contaminants and Substrates

Laser cleaning is an advanced, non-contact surface-processing technology that utilizes a high-energy laser beam to irradiate a component's surface, leading to the instant evaporation or stripping of contaminants, rust, and coatings. Compared with conventional cleaning methods, laser cleaning offers significant advantages, including high precision, efficiency, environmental friendliness, and superior controllability [1]. The interaction between a laser beam and a material involves complex physical and chemical processes such as decomposition, ionization, vibration, expansion, and vaporization. The effectiveness of the cleaning process is governed by three fundamental mechanisms: the laser thermal ablation mechanism, the laser thermal stress mechanism, and the plasma shock wave mechanism. The dominance of each mechanism depends on the laser parameters and the material properties of the contaminants and substrate [1]. This document details these mechanisms within the specific context of using a 248 nm KrF excimer laser for cleaning and preparing optical surfaces, providing application notes and experimental protocols for researchers.

Fundamental Mechanisms and Their Principles

Laser Thermal Ablation Mechanism

The laser thermal ablation mechanism primarily relies on the photothermal effect. When a pulsed laser beam irradiates the attachments on a substrate surface, the energy is absorbed, causing a rapid temperature increase. If the temperature exceeds the gasification threshold of the contaminant, it will be removed through processes like vaporization, combustion, or decomposition [1]. For a 248 nm KrF excimer laser, the high photon energy can also induce photochemical effects, where the photon energy directly breaks molecular bonds in the contaminant layer, transforming the material into a loose state that promotes its removal [1].

The temperature increase (ΔT) on the material surface under laser irradiation can be expressed as:

[

\Delta T = \frac{P}{\pi \omega_0 K}

]

where P is the incident laser power, ω₀ is the laser spot radius, and K is the thermal conductivity of the material [1].

The laser energy (W) required within a single pulse duration can be described as:

[

W = \rho h [Cs (Tm - T0) + Cp (Tb - Tm) + Lm + Lr]

]

where ρ is the density, h is the thickness of the attachment, C_s is the specific heat capacity, C_p is the specific heat, T_m is the melting point, T_b is the boiling point, T_0 is the initial temperature, L_m is the latent heat of melting, and L_r is the latent heat of evaporation [1].

A critical aspect of this mechanism is the ablation threshold. When the ablation threshold of the contaminant is lower than that of the substrate, the laser energy density can be controlled to remove the attachment without damaging the substrate. Successful application requires careful calibration of laser parameters to stay within this window [1].

Laser Thermal Stress Mechanism

Unlike the thermal ablation mechanism, the laser thermal stress mechanism utilizes stress effects induced by the laser rather than relying solely on thermal effects to vaporize material. When a short-pulse laser irradiates a surface, the attachment and a thin layer of the substrate absorb energy, causing rapid heating. The short pulse width leads to a very fast thermal expansion cycle, generating high compressive stresses. Upon cooling, this can create a high-pressure solid lifting force. When this lifting force surpasses the van der Waals force binding the contamination to the substrate, the contaminants are ejected from the surface [1].

The one-dimensional heat conduction equation governing this process is [1]:

[

\rho c \frac{\partial T(z,t)}{\partial t} = \lambda \frac{\partial^2 T(z,t)}{\partial z^2} + \alpha I_0 A e^{-Az}, (0 \leq z \leq l, 0 \leq t \leq \tau)

]

where ρ is density, c is specific heat capacity, λ is thermal conductivity, α is absorptivity, I₀ is laser intensity, A is the absorption coefficient, z is depth, and t is time.

The resulting thermal stress (σ) can be expressed as:

[

\sigma = Y \varepsilon = Y \frac{\Delta l}{l} = Y \gamma

]

where Y is Young's modulus, ε is strain, Δl is the change in length, l is the original length, and γ is the thermal expansion coefficient of the material [1]. This mechanism is particularly effective for removing particles or layers with a different thermal expansion coefficient from the substrate.

Plasma Shock Wave Mechanism

The plasma shock wave mechanism becomes significant when the laser fluence is high enough to ionize air or vaporized material above the surface, creating a laser-induced plasma. The rapid expansion of this plasma generates a propagating shock wave that travels towards the substrate surface. The impulsive pressure from this shock wave is capable of dislodging and removing tiny particles and thin films from the surface. This mechanism is highly effective for cleaning sub-micron particles without significant thermal loading of the substrate [1].

Quantitative Parameters for KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning

The following tables summarize critical laser parameters and their effects on the cleaning process and outcomes for different material systems, as reported in recent research.

Table 1: KrF Laser Parameters and Observed Cleaning Effects on Various Materials

| Material | Laser Fluence (J/cm²) | Pulse Number | Pulse Duration/ Frequency | Key Observations | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-cut LiNbO₃ | Varied (Ablation study) | Varied (1 to 100) | 20 ns, 25 Hz | Surface damage (exfoliation, discoloration) observed at high fluence/pulses; Suppressed with SiO₂ overlayer. | [2] |

| WC-Co Composite | 5.5 J/cm² | 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100 | 20 ns, 1-100 Hz | Lower pulses (1, 5) caused Co removal & nano-structuring; Higher pulses (50, 100) induced micro-cracks. | [3] |

| Polyimide (PI) Film | 7-18 mJ/cm² | 6000-18000 | 20 ns, 10 Hz | Formation of Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures (LIPSS); Optimal at ~14 mJ/cm², 12000 pulses. | [4] [5] |

| General Polymer Ablation | Material-dependent | Material-dependent | Nanosecond pulses | Ablation occurs when fluence (F) exceeds material threshold; depends on pulses (P), frequency, and absorption coefficient. | [6] |

Table 2: Process Outcomes and Optimization Guidelines for KrF Laser Cleaning

| Process Outcome | Key Influencing Parameters | Optimal Conditions / Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Minimizing Substrate Damage | Fluence, Pulse Number, Presence of overlayer. | Use fluence just above contaminant's ablation threshold but below substrate's damage threshold; Use minimal pulses needed; A SiO₂ overlayer can protect the substrate [2] [1]. |

| Selective Binder Removal (WC-Co) | Fluence, Pulse Number. | Lower number of pulses (1-5) with high fluence (5.5 J/cm²) selectively removes Co binder without major cracking [3]. |

| Nanostructure Formation (LIPSS) | Energy Density, Pulse Number, Polarization. | For PI, 14.01 mJ/cm² with 12,000 pulses of linearly polarized 248 nm laser produces uniform ~200 nm period ripples [4] [5]. |

| Controlled Roughening | Pulse Number, Fluence. | Surface roughness increases with pulse number; can be controlled predictably (e.g., Ra from 0.55 nm to ~14.3 nm on PI) [4] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for KrF Laser Cleaning

General Workflow for Laser Cleaning and Surface Preparation

The following diagram outlines a standard experimental workflow for laser cleaning and surface modification using a KrF excimer laser.

Protocol 1: Surface Decontamination and Coating Removal

This protocol is designed for removing contaminants or thin films from optical surfaces with minimal substrate damage.

- Objective: To selectively remove a surface contaminant or coating from a substrate (e.g., LiNbO₃) without inducing surface damage.

- Materials:

- KrF Excimer Laser (248 nm).

- Target sample (e.g., X-cut LiNbO₃).

- Optional: SiO₂ overlayer film (~1.0 µm thick).

- Solvents (ethanol, deionized water) for ultrasonic cleaning.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Clean the substrate ultrasonically in absolute ethanol and then deionized water for 10 minutes each. Dry in a vacuum oven. If using a protective overlayer, deposit a ~1.0 µm SiO₂ film on the LiNbO₃ surface [2].

- Laser Setup: Configure the KrF laser with a pulse repetition rate of 25 Hz and a pulse width (FWHM) of 20 ns. Use a mask-projection system to define the cleaning area [2].

- Parameter Calibration:

- Conduct a test with a low fluence (e.g., below 1 J/cm²) and a low number of pulses (e.g., 10).

- Gradually increase the fluence and pulse count in subsequent test areas while monitoring for the onset of surface damage (exfoliation, discoloration).

- Identify the optimal fluence that achieves cleaning while staying below the damage threshold. The use of a SiO₂ overlayer can allow for higher fluences without damage [2].

- Cleaning Execution: Irradiate the entire target area with the optimized parameters.

- Validation: Inspect the surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to confirm contaminant removal and check for laser-induced damage [2].

Protocol 2: Selective Binder Ablation for Surface Preparation

This protocol is used for surface engineering of composite materials, such as preparing WC-Co substrates for diamond film coating.

- Objective: To selectively remove the cobalt (Co) binder from a WC-Co composite surface to create a roughened, residual-stress-free surface ideal for diamond film adhesion.

- Materials:

- KrF Excimer Laser (248 nm, Compex Pro 201 or equivalent).

- Polished WC-Co composite sample.

- Diamond polishing compound (1-6 µm grit).

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Polish the WC-Co sample using diamond polishing compounds of decreasing grit size (e.g., 6 µm, 3 µm, 1 µm) to achieve a smooth initial surface [3].

- Laser Setup: The laser is operated at a wavelength of 248 nm. The beam is delivered to the sample surface, which is placed in open atmosphere at room temperature [3].

- Parameter Calibration:

- For selective Co removal and nano-structuring without micro-cracks, use a lower number of pulses (1 to 10) with a higher fluence (e.g., 5.5 J/cm²) [3].

- Avoid higher pulse counts (e.g., 50, 100) at this fluence, as they induce micro-cracks.

- Processing: Irradiate the sample surface. A lower number of pulses will yield a darker surface region indicating Co removal and possible carbon phase formation [3].

- Validation:

- Use SEM to examine surface morphology and detect micro-cracks.

- Use Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) to confirm the reduction in surface cobalt content [3].

- Use X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to analyze for the presence of residual stress.

- Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to quantify the increase in surface roughness [3].

Protocol 3: Fabrication of Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures (LIPSS)

This protocol is for creating functional, periodic nanostructures on polymer surfaces to alter properties like wettability.

- Objective: To fabricate uniform nanoscale periodic ripples (LIPSS) on a polyimide (PI) film surface to enhance hydrophilicity.

- Materials:

- Linearly polarized KrF excimer laser (248 nm).

- Polyimide film (e.g., thickness 0.05 mm).

- Absolute ethanol and deionized water.

- Optical homogenizer to ensure a flat-top beam profile.

- Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Cut PI film into 15x15 mm squares. Clean ultrasonically in absolute ethanol and deionized water for 10 minutes each. Dry in a vacuum drying oven [4] [5].

- Laser Setup:

- Use an optical path with a homogenizer to achieve a uniform energy distribution.

- Ensure the laser's inherent linear polarization is used; no additional polarizer is needed. The ripples will form perpendicular to the polarization direction [4] [5].

- Set the pulse width to 20 ns and the repetition rate to 10 Hz. Use normal beam incidence.

- Parameter Calibration:

- Processing: Irradiate the sample. The large number of pulses requires a stable sample stage and consistent laser output.

- Validation:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Equipment and Materials for KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| KrF Excimer Laser | 248 nm wavelength, e.g., Lambda Physik LPX210i or Compex Pro 201. | The primary energy source for ablation and surface modification. The UV wavelength is well-absorbed by many materials. |

| UV-Grade Fused Silica Substrates/Mirrors | UV Fused Silica, Surface Quality: 10-5 scratch-dig. | Used as substrates or optics due to low thermal expansion, high UV transmission, and high damage threshold [7]. |

| Beam Delivery & Homogenizing Optics | Attenuators, beam splitters, plano-convex lenses, homogenizer. | Controls laser fluence, shapes the beam, and creates a uniform (flat-top) energy profile on the target surface [4] [5]. |

| Characterization: SEM | Scanning Electron Microscope. | Provides high-resolution imaging of surface morphology, ablation features, and damage assessment [2] [3]. |

| Characterization: EDS | Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy. | Analyzes elemental composition changes on the surface (e.g., selective Co removal from WC-Co) [3]. |

| Characterization: AFM | Atomic Force Microscope, e.g., Cypher VRS. | Quantifies nanoscale topography, measures LIPSS period/depth, and evaluates surface roughness (Ra) [4] [5]. |

| Characterization: XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. | Investigates chemical state changes and reactions with atmospheric gasses (e.g., nitrogen, oxygen) after laser treatment [3]. |

| Protective Overlayer | SiO₂ thin film (~1.0 µm thick). | Deposited on the sample to suppress surface damage (exfoliation) during deep ablation processes [2]. |

The Krypton Fluoride (KrF) excimer laser, operating at a wavelength of 248 nanometers (nm), is a cornerstone technology in advanced cleaning and processing applications. Its significance stems from the unique properties of ultraviolet-C (UV-C) light at this specific wavelength, which offers a powerful combination of high photon energy and strong material absorption. The high photon energy of approximately 4.99 eV enables the laser to directly break chemical bonds in organic materials and contaminants, facilitating a photochemical ablation process. Concurrently, this wavelength is strongly absorbed by a wide range of organic polymers, biological specimens, and degradation products found on cultural heritage objects, making it exceptionally effective for precise, non-contact cleaning. Within the broader thesis on KrF-excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces, this document establishes the fundamental principles and provides detailed protocols for harnessing these properties in research and development.

Key Characteristics and Applications of 248 nm Radiation

The 248 nm wavelength occupies a critical position in the electromagnetic spectrum, offering distinct advantages for material processing.

Fundamental Properties

- High Photon Energy: At 248 nm, each photon carries an energy of about 4.99 eV. This energy is sufficient to directly dissociate covalent bonds (e.g., C-C, C-H, C-O) common in organic molecules and polymers, initiating photochemical decomposition [8] [9].

- Strong Absorption: Many materials, including organic coatings, microbial organisms, and pollution crusts, exhibit strong absorption bands in the UV-C region. This high absorption confines the laser energy to a thin surface layer, enabling precise removal without generating significant thermal stress to the underlying substrate [10] [11].

- Pulsed Operation: KrF excimer lasers typically operate with nanosecond (ns) to femtosecond (fs) pulse durations. This pulsed delivery allows for high peak powers that drive efficient ablation, while the short pulse width limits heat diffusion, minimizing thermal damage to sensitive surfaces in applications ranging from painting restoration to semiconductor cleaning [8] [12] [1].

Quantitative Performance Data

Table 1: Efficacy of 248 nm Pulsed Laser in Various Applications

| Application Field | Target Material | Key Laser Parameters | Efficacy / Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pest Control | Spider mites (T. urticae) | 248 nm, 5 mJ pulse, 60 Hz, 80 kJ/m² dose | 98% mortality in adult mites | [8] |

| Pest Control | Spider mite eggs | 248 nm, 5 kJ/m² dose | ~100% egg mortality (prevented hatching) | [8] |

| Painting Cleaning | Aged varnish/overpaint | 248 nm, 0.1 - 1.1 J/cm² fluence | Successful removal of non-original layers | [10] |

| Water Treatment | Ibuprofen (pharmaceutical) | 266 nm (for reference), ns pulses | >95% degradation in pure water in <6 minutes | [9] |

| Stained Glass Cleaning | Encrustations & corrosion | 248 nm, varied fluence & rep. rate | Defined removal of crusts without damaging gel layer | [11] |

Experimental Protocols for KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments, demonstrating the application of 248 nm laser cleaning across different fields.

Protocol 1: Cleaning of Aged Varnish from Paintings

This protocol is adapted from studies on laser cleaning of historical easel paintings [10].

1. Principle: Aged varnishes and overpaints strongly absorb 248 nm radiation. The laser energy ablates the material in a controlled, layer-by-layer manner, with selectivity achieved by tuning parameters below the damage threshold of the underlying original paint.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- KrF Excimer Laser System (e.g., Lambda Physik LPX series) emitting at 248 nm with nanosecond pulses.

- Beam delivery system with galvanometric mirrors for scanning.

- Non-invasive analytical tools: Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), Reflection FT-IR spectrometer, Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) spectrometer.

- Fume extraction system.

3. Procedure: 1. Pre-Cleaning Assessment: Characterize the painting surface using OCT to determine the stratigraphy and thickness of the varnish layers. Perform reflection FT-IR to identify the molecular composition of the surface coatings. 2. Laser Parameter Calibration: - Set the laser to a low fluence (e.g., 0.1 J/cm²). - Perform test cleaning on a small, inconspicuous area. - Gradually increase the fluence (up to ~1.1 J/cm²) and number of pulses (N) until optimal removal is observed, monitored in real-time if possible. 3. Cleaning Operation: Use the galvanometric scanner to direct the laser beam (shaped to a rectangular spot of ~0.08 x 1.00 cm²) over the target area. 4. In-situ Monitoring: After each cleaning pass, re-analyze the area with OCT and FT-IR to assess the amount of material removed and confirm the absence of the varnish layer without affecting the underlying paint. 5. Final Assessment: Conduct a final LIF measurement to verify the surface state and ensure no latent damage has occurred.

Protocol 2: Acaricidal Treatment Using 248 nm Irradiation

This protocol is based on research into the acaricidal efficacy of UV-C irradiation on spider mites [8].

1. Principle: High-intensity 248 nm radiation is lethal to arthropods and their eggs, causing molecular damage to DNA and proteins. The pulsed nature of the laser enhances efficacy through high peak power.

2. Materials and Equipment:

- Pulsed KrF Excimer Laser (e.g., CEX-100) with output at 248 nm.

- Laser power meter (e.g., thermopile sensor).

- Sample holders for mites and host leaves.

- Environmental chamber for rearing mites (26°C, 50-60% RH).

3. Procedure: 1. Sample Preparation: Rear two-spotted spider mites (Tetranychus urticae) on host plant leaves (e.g., common bean). Collect adult females and eggs of synchronized age for experiments. 2. System Setup: Place the laser source at a fixed distance from the target (e.g., 150 mm). Measure the power (mW) and calculate the energy density (kJ/m²) at the target surface. The spot size is typically small (e.g., 2.16 cm²). 3. Irradiation: Expose adult mites and eggs to the laser for varying durations (e.g., 1 to 4 minutes) and energy densities (e.g., 5 to 80 kJ/m²). The pulse repetition rate can be adjusted (e.g., up to 100 Hz). 4. Post-Treatment Evaluation: - Mite Mortality: Assess mortality immediately after irradiation and again at 24 hours post-irradiation. - Egg Hatchability: Observe irradiated eggs daily for up to 12 days to determine the percentage that fail to hatch.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

Table 2: Key Equipment and Reagents for 248 nm Laser Cleaning Research

| Item Name | Function / Role | Specific Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KrF Excimer Laser | Generates high-energy 248 nm pulsed light. | CEX-100; Lambda Physik LPX 200/305i. Requires KrF gas mixture. |

| Beam Shaping Optics | Modifies beam profile and spot size on target. | Fused silica lenses, apertures. Enables even energy distribution. |

| Galvanometric Scanner | Precisely directs the laser beam over the surface. | Essential for automated cleaning of large or complex areas. |

| Calibrated Power/Energy Meter | Measures laser output at the target. | NIST-calibrated thermopile sensor (e.g., GreenTEG B05). Critical for dose control. |

| Non-Invasive Analysers (OCT, FT-IR) | Assesses surface pre- and post-cleaning. | OCT for stratigraphy; FT-IR for chemical composition. |

| Fume Extraction System | Removes ablated particulates and vapors. | Critical for operator safety and laboratory air quality. |

Workflow and Interaction Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the experimental workflow for laser cleaning and the fundamental mechanisms of laser-material interaction at 248 nm.

KrF Laser Cleaning Experimental Workflow

Laser-Material Interaction Mechanisms at 248 nm

The 248 nm wavelength generated by KrF excimer lasers is a powerful tool for advanced cleaning, leveraging its high photon energy and strong material absorption. The provided application notes and detailed experimental protocols for painting conservation and acaricidal treatment showcase its versatility and efficacy. The fundamental mechanisms—photochemical, photothermal, and mechanical—often work in concert to enable the precise, controlled, and residue-free removal of unwanted surface layers. This makes 248 nm laser cleaning an invaluable technique for R&D professionals working with sensitive optical surfaces, cultural heritage artifacts, and in specialized industrial and biomedical fields.

Photochemical versus Photothermal Effects at Ultraviolet Wavelengths

The interaction of ultraviolet laser radiation with materials engages two primary mechanisms: photochemical and photothermal effects. Understanding the interplay between these phenomena is crucial for optimizing laser applications, particularly in precision fields such as laser cleaning of optical surfaces. At 248 nm, the wavelength of KrF-excimer lasers, photon energy reaches approximately 5 eV, sufficient to directly break molecular bonds in many materials [3]. This application note examines the conditions governing the dominance of each mechanism and provides experimental protocols for researchers requiring controlled laser processing of optical surfaces.

The photochemical effect occurs when high-energy photons directly break chemical bonds, causing material ablation through non-thermal pathways with minimal heat transfer to the substrate. In contrast, the photothermal effect relies on photon energy being converted to heat, enabling thermal processes like melting, vaporization, and stress-induced removal [1]. For KrF-excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces, determining which mechanism dominates depends on specific laser parameters and material properties, requiring careful experimental control to achieve desired outcomes while preventing substrate damage.

Theoretical Background

Fundamental Mechanisms

Photochemical effects dominate when photon energy exceeds molecular bond energies, enabling direct bond dissociation without significant heat generation. At 248 nm (5 eV), this energy surpasses the binding energies of many organic compounds (C-C: 3.6 eV, C-H: 4.3 eV) and some inorganic bonds [13]. The process involves electronic excitation followed by bond cleavage, resulting in precise, cold ablation with minimal thermal damage to surrounding areas. This mechanism typically requires short pulse durations and high peak fluences to achieve multiphoton absorption when photon energy alone is insufficient for direct bond breaking [14].

Photothermal effects occur when materials absorb laser energy and convert it to heat, causing rapid temperature rise that leads to melting, vaporization, or thermal decomposition. This mechanism depends on the thermal properties of the material, including absorption coefficient, thermal conductivity, and specific heat capacity [1]. The resulting thermal stress can produce mechanical forces that remove material when thermal expansion differences between surface contaminants and substrate exceed adhesion forces [15].

Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Characteristics of Photochemical and Photothermal Effects at 248 nm

| Parameter | Photochemical Effect | Photothermal Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Transfer | Direct bond breaking via electronic excitation | Phonon-mediated thermal activation |

| Primary Mechanism | Photon-induced molecular dissociation | Thermal vibration leading to phase changes |

| Spatial Resolution | High (sub-micron) | Moderate to high |

| Thermal Damage Risk | Low | High |

| Typical Pulse Duration | Nanosecond to femtosecond | Microsecond to continuous wave |

| Fluence Requirement | Material-dependent (exceed ablation threshold) | Sufficient for rapid heating |

| Material Selectivity | High (wavelength-dependent absorption) | Moderate (thermal property dependent) |

| Suitable Applications | Precision cleaning, polymer processing | Paint removal, large-area cleaning |

KrF Excimer Laser Specifics

KrF excimer lasers operating at 248 nm provide unique advantages for surface processing due to their high photon energy and typical nanosecond pulse durations. This wavelength is strongly absorbed by most organic materials, biological tissues, and many metal oxides, enabling precise ablation with minimal thermal penetration [3] [10]. The high absorption coefficient at UV wavelengths typically confines energy deposition to thin surface layers, facilitating both photochemical bond breaking and rapid thermal heating depending on pulse parameters.

Experimental Evidence and Parameter Optimization

Dominant Mechanism Identification

Recent research reveals that the dominant mechanism at 248 nm depends on specific laser parameters and material properties. For graphene oxide reduction, photochemical effects prevail under visible light irradiation despite temperatures remaining below the standard thermal reduction threshold of 200°C [14]. Conversely, laser cleaning of metallic contaminants typically employs photothermal mechanisms where thermal stress overcomes adhesion forces [15].

Table 2: Laser Parameters and Dominant Mechanisms for Different Materials

| Material | Laser Parameters | Dominant Mechanism | Observed Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide | 532 nm, 300 μW, CW | Photochemical | Reduction without significant heating |

| WC-Co Composite | 248 nm, 5.5 J/cm², 1-50 pulses | Mixed (pulse-dependent) | Selective Co removal at low pulses |

| Historical Paintings | 248 nm, 0.1-1.1 J/cm², 1-50 pulses | Photochemical | Varnish removal without pigment damage |

| Polyimide Film | 248 nm, 14.01 mJ/cm², 12,000 pulses | Photothermal | LIPSS formation via thermal effects |

| Glass Insulators | 1064 nm, 8 W, 8 m/s scan | Photothermal | Contaminant removal via thermal stress |

KrF Laser Cleaning of Optical Surfaces

For KrF excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces at 248 nm, the following parameter ranges have been established for different applications:

- Historical painting cleaning: Fluence: 0.1-1.1 J/cm², Pulse number: 1-50 pulses, Selective varnish removal via photochemical ablation [10]

- WC-Co composite treatment: Fluence: 1.5-5.5 J/cm², Pulse number: 1-100 pulses, Selective cobalt removal at lower pulse counts [3]

- Polyimide nanostructuring: Fluence: 7-18 mJ/cm², Pulse number: 6000-18000 pulses, LIPSS formation via photothermal mechanism [5]

The optimal working window for precision cleaning of optical surfaces typically employs lower fluences (0.5-2 J/cm²) with minimal pulse counts (1-20 pulses) to maximize photochemical effects while minimizing thermal contributions [3] [10].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning of Optical Surfaces

Objective: Remove contaminants from optical surfaces without substrate damage using dominant photochemical effects.

Materials and Equipment:

- KrF excimer laser (248 nm, nanosecond pulse duration)

- Optical components to be cleaned

- Beam delivery system with galvanometric mirrors

- Energy meter for fluence calibration

- Non-invasive monitoring equipment (OCT, reflection FT-IR)

Procedure:

- Surface Characterization:

- Perform baseline analysis using optical coherence tomography (OCT) to determine contaminant thickness

- Conduct reflection FT-IR spectroscopy to identify chemical composition of contaminants

Laser Parameter Setup:

- Set laser fluence between 0.5-1.5 J/cm² (below substrate damage threshold)

- Configure beam spot size based on contaminant distribution (typically 0.08 × 1.00 cm² rectangular area)

- Set initial pulse number to 5 pulses for test cleaning

Test Cleaning:

- Irradiate test areas with systematic variation of pulse numbers (1, 3, 5, 10, 20 pulses)

- Maintain constant fluence within ±5% variation across the beam profile

Post-Treatment Assessment:

- Re-examine cleaned areas using OCT to measure remaining contaminant thickness

- Perform FT-IR analysis to verify complete contaminant removal

- Inspect for surface damage using optical microscopy

Parameter Optimization:

- Select parameters that achieve complete contaminant removal without substrate damage

- For heat-sensitive substrates, prioritize lower pulse counts with moderate fluence

Troubleshooting:

- If contamination persists: Gradually increase pulse number (up to 50 pulses maximum)

- If substrate damage occurs: Reduce fluence by 0.1 J/cm² increments

- For non-uniform cleaning: Verify beam homogeneity and surface planarity

Protocol 2: Differentiation of Photochemical vs. Photothermal Effects

Objective: Determine the dominant mechanism in laser-material interaction at 248 nm.

Materials and Equipment:

- KrF excimer laser system with adjustable parameters

- Target materials (polymers, metals, or contaminants)

- Thermal imaging camera or Raman thermometry system

- XPS analysis capability

- AFM for surface topography

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare identical samples of target material

- Ensure uniform surface roughness and contamination levels

Thermal Measurement Setup:

- Configure Raman thermometry with silicon nanowires for in situ temperature measurement

- Calibrate temperature measurement system

- Set safety limits to prevent material degradation

Laser Irradiation:

- Irplicate sample series with varying fluences (0.1-5 J/cm²) and pulse numbers (1-100)

- Monitor temperature evolution during irradiation

- Record maximum reached temperatures

Post-Irradiation Analysis:

- Perform XPS analysis to identify chemical changes

- Conduct AFM to examine surface topography modifications

- Compare results with control samples heated conventionally to same temperatures

Mechanism Identification:

- Photochemical dominance: Significant chemical modification with temperatures below thermal activation threshold

- Photothermal dominance: Material changes correlate with temperature profile and match conventional heating results

- Mixed mechanism: Both chemical and thermal changes observed

Data Interpretation:

- Temperatures <150°C with material modification indicate photochemical dominance

- Material changes only above specific temperature thresholds suggest photothermal processes

- Immediate ablation at low pulse numbers suggests photochemical pathways

- Gradual material modification over multiple pulses suggests thermal accumulation

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for KrF Laser Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| KrF Excimer Laser | 248 nm photon source | 5 eV photons, nanosecond pulses |

| Beam Homogenizer | Creates uniform fluence distribution | Essential for reproducible processing |

| Galvanometric Mirror System | Precise beam positioning | Enables complex cleaning patterns |

| Energy Attenuator | Adjusts laser fluence | Fine-tunes energy density |

| Optical Coherence Tomography | Non-invasive stratigraphic analysis | Measures layer thickness pre/post cleaning |

| Reflection FT-IR Spectrometer | Chemical composition analysis | Identifies molecular changes |

| Atomic Force Microscope | Surface topography characterization | Nanoscale resolution of laser effects |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer | Surface chemistry analysis | Quantifies elemental and chemical changes |

| Raman Thermometry | In situ temperature measurement | Uses SiNWs for accurate thermal monitoring |

Visualizations

KrF Laser Cleaning Workflow

Diagram 1: KrF Laser Cleaning Workflow - This flowchart illustrates the systematic protocol for KrF excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces, emphasizing parameter optimization and damage prevention.

Mechanism Differentiation Methodology

Diagram 2: Mechanism Differentiation Methodology - This workflow outlines the experimental approach for determining whether photochemical or photothermal effects dominate during UV laser processing.

The interaction of 248 nm laser radiation with materials involves complex competition between photochemical and photothermal effects. For KrF-excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces, photochemical mechanisms typically dominate at lower fluences (0.5-2 J/cm²) and pulse numbers (1-20), enabling precise contaminant removal without substrate damage. Photothermal effects become increasingly significant at higher energy densities and pulse counts, particularly for materials with strong UV absorption.

Successful application requires careful parameter optimization based on the specific contaminant-substrate system, supported by non-invasive monitoring techniques. The protocols outlined herein provide researchers with methodologies to achieve controlled laser cleaning while identifying dominant mechanisms for process optimization. As research advances, continued investigation of the interplay between these mechanisms will further enhance precision and efficiency in UV laser processing of optical surfaces.

Within the scope of broader thesis research on KrF-excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces at a wavelength of 248 nm, understanding the precise ablation thresholds of common contaminants and underlying optical substrates is paramount. This laser cleaning process depends on the principle of selective ablation, where the laser energy density is carefully controlled to exceed the removal threshold of the contaminant while remaining below the damage threshold of the optical substrate [1]. This application note consolidates critical quantitative data on these thresholds and provides detailed, reproducible experimental protocols for their determination, serving as an essential resource for researchers and scientists in the field.

Material Ablation and Damage Thresholds

The effectiveness and safety of laser cleaning are governed by the differential in ablation thresholds between the contaminant and the substrate. The data presented below are critical for defining the operational window of the process.

Table 1: Ablation and Damage Thresholds for Common Materials at 248 nm

| Material Type | Material Name | Ablation/Damage Threshold (mJ/cm²) | Key Findings / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contaminant | Sulfide on Steel | 410 [1] | Removal threshold; successful cleaning between 410-8250 mJ/cm². |

| Contaminant | Aged Triterpenoid Varnishes | 200,000 - 1,800,000 [16] | "Optimum" photochemical ablation fluence range. |

| Contaminant | Parylene-C (on Iridium) | >1,000,000 [17] | Successful deinsulation; higher fluence improves uniformity. |

| Optical Substrate | Polyimide (PI) Film | 7,000 - 18,000 [5] | LIPSS formation range; optimal at ~14,010 mJ/cm². |

| Optical Substrate | CaF₂ (Highly Polished) | ~6,100,000 [18] | Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) for front surface. |

| Optical Substrate | CaF₂ (Roughly Polished) | ~5,600,000 [18] | LIDT for front surface; lower due to surface defects. |

The data reveals a significant spread in threshold values, influenced by material properties and surface condition. For instance, the surface polishing level of CaF₂ substrates has a demonstrable impact on their laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT). Highly polished CaF₂ windows exhibit a higher LIDT (6.1 J/cm²) compared to their roughly polished counterparts (5.6 J/cm²), as surface defects like scratches and digs on the latter act as precursors to damage by enhancing local light absorption [18]. Furthermore, the LIDT of the rear surface is consistently lower than that of the front (incident) surface for both polishing levels, a phenomenon attributed to internal light field modulation [18].

Fundamental Laser Cleaning Mechanisms

The interaction of a 248 nm laser with materials can be described by three primary mechanisms, the dominance of which depends on the laser parameters and the material properties [1].

- Laser Thermal Ablation Mechanism: A high-energy laser beam irradiates the surface, causing the attachments to undergo rapid heating, leading to vaporization, combustion, or decomposition. For a 248 nm KrF excimer laser, the high photon energy (5 eV) can directly break molecular bonds (C-C, C-H, C-O) in organic contaminants, a process known as photochemical ablation or laser ablation [19].

- Laser Thermal Stress Mechanism: The short pulse width of the laser induces rapid, localized heating and cooling, leading to quick thermal expansion and contraction. This generates a high-pressure solid lifting force or shear force at the contaminant-substrate interface, mechanically peeling the contaminant away once this force surpasses the van der Waals force [1].

- Plasma Shock Wave Mechanism: When an ultra-short pulse, high-peak-power laser irradiates a surface, it can generate vapor and subsequently a laser-induced plasma. This plasma, continuing to absorb laser energy, produces an instantaneous shock wave (1-100 kbar) that fragments and removes surface contaminants [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate cleaning mechanism based on the contaminant and substrate properties.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Determining Single-Pulse Ablation Thresholds

This protocol outlines a standard method for determining the ablation threshold of a material using a KrF excimer laser, based on industry-standard practices [16] [18].

Objective: To determine the minimum laser fluence required to initiate ablation of a material with a single laser pulse.

Materials and Equipment:

- KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm)

- calibrated laser energy meter

- beam homogenizer and attenuator

- sample material

- optical microscope (for post-irradiation analysis)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Clean and dry the sample surface to remove any ambient contaminants.

- Laser Setup: Configure the laser optical path, ensuring the use of a beam homogenizer to achieve a flat-top beam profile and an attenuator for precise fluence control.

- Irradiation Test: Fire a single laser pulse onto the sample surface at a predetermined starting fluence.

- Inspection: Examine the irradiated spot under an optical microscope for signs of material modification or removal.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 3 and 4, systematically increasing or decreasing the fluence in small increments.

- Threshold Identification: The ablation threshold is identified as the fluence at which a permanent, microscopically visible change to the surface is first observed.

Protocol for Systematic Investigation of Multi-Pulse LIPSS Formation on Polymers

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for studying the formation of Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures (LIPSS) on polymer surfaces like polyimide, as described in recent literature [5].

Objective: To systematically investigate the effects of laser energy density and pulse number on the morphology and surface roughness of LIPSS on polyimide films.

Materials and Equipment:

- KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm, pulse width ~20 ns, 10 Hz repetition rate)

- beam delivery system with homogenizer and attenuator

- motorized X-Y sample stage

- polyimide film samples (e.g., 15 mm x 15 mm, ultrasonically cleaned)

- Atomic Force Microscope (AFM)

Procedure:

- Parameter Definition: Define a matrix of experimental parameters. For example:

- Laser energy density: A range from 7 to 18 mJ/cm².

- Pulse number: A range from 6000 to 18,000 pulses.

- Sample Irradiation: Mount the PI sample on the stage. Using computer control, irradiate different areas of the sample with specific combinations of energy density and pulse number from the parameter matrix.

- AFM Characterization: After laser processing, characterize the surface morphology of each irradiated area using AFM in tapping mode to avoid sample damage.

- Data Analysis: For each parameter set, measure the spatial period of the ripples, the ripple depth, and calculate the surface roughness (Ra). The most uniform and well-defined LIPSS are typically achieved at an optimal combination of parameters (e.g., ~14 mJ/cm² and 12,000 pulses for polyimide) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Equipment for KrF Laser Cleaning Research

| Item Name | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| KrF Excimer Laser | The core light source, emitting at 248 nm with high photon energy (5 eV) suitable for both photochemical and photothermal processes. |

| Beam Homogenizer | Creates a uniform flat-top beam profile, which is critical for achieving consistent ablation and accurate threshold measurements across the processed area. |

| Precision Energy Attenuator | Allows for fine, continuous adjustment of the laser fluence incident on the sample, enabling precise determination of ablation thresholds. |

| Atomic Force Microscope | Used for high-resolution characterization of surface topography, including the measurement of LIPSS periodicity, depth, and surface roughness (Ra). |

| Optical Microscope | For initial, rapid inspection of irradiated spots to identify the onset of ablation or surface damage. |

| Polyimide Films | A model polymer substrate with high thermal stability, often used for fundamental studies on laser-polymer interactions and LIPSS formation. |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) Windows | A common optical substrate material with high transmission in the UV range; used for studying laser-induced damage thresholds (LIDT). |

This application note has synthesized key data and methodologies central to the KrF-excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces. The compiled ablation and damage thresholds provide a critical foundation for defining safe and effective processing windows. Furthermore, the detailed experimental protocols empower researchers to generate reproducible, high-quality data specific to their contaminant-substrate systems. A deep understanding of the interplay between laser parameters and material properties, as outlined in these guidelines, is essential for advancing the application of 248 nm laser cleaning in precision industrial and research settings.

Laser cleaning, particularly using KrF excimer lasers at a wavelength of 248 nm, has emerged as an advanced, controllable surface-processing technology with significant applications in the conservation of artworks and the processing of optical components [20] [1]. The interaction between the high-energy ultraviolet laser beam and material involves complex physical and chemical processes, including decomposition, ionization, vibration, expansion, and ablation [1]. Understanding the nature and extent of the chemical, physical, and morphological changes induced by laser irradiation is critical for optimizing cleaning procedures, minimizing substrate damage, and developing future applications. This Application Note details the fundamental mechanisms, characterizes the effects on diverse materials, and provides standardized protocols for analyzing these laser-induced modifications, serving as a practical resource within the broader context of KrF-excimer laser cleaning of optical surfaces.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Laser-Material Interaction

The interaction of a 248 nm laser with materials is governed by several competing mechanisms. The dominance of each mechanism depends on the laser parameters (e.g., fluence, pulse width), the properties of the contaminant or coating, and the substrate material [1].

- Laser Thermal Ablation Mechanism: When a pulsed laser beam irradiates a surface, the absorbed energy causes a rapid temperature increase. If the temperature exceeds the material's vaporization threshold, the attachments undergo combustion, decomposition, and ablation [1]. This mechanism is predominant when the laser energy density is set above the ablation threshold of the contaminant but below that of the substrate, enabling selective removal.

- Laser Thermal Stress Mechanism: This mechanism utilizes the stress effect induced by the laser rather than its thermal effect. The short pulse width causes rapid heating and cooling, resulting in quick thermal expansion and generating a high-pressure solid lifting force. The attachment is removed when this solid lifting force surpasses the van der Waals force binding it to the substrate [1].

- Plasma Shock Wave Mechanism: When a high-energy laser ionizes the surrounding air or surface material, it creates plasma. The rapid expansion of this plasma generates a shock wave that propagates across the surface, effectively dislodging and removing tiny particles and contaminants without direct ablation [1].

The following workflow illustrates the decision-making process for selecting the appropriate analysis techniques based on the observed laser-induced changes:

Material-Specific Laser-Induced Alterations

The effects of 248 nm KrF excimer laser irradiation are highly material-dependent. The following sections and tables summarize key changes observed in different material classes.

Optical Crystals: Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂)

Calcium fluoride is an important optical window material for ultraviolet (UV) and deep-ultraviolet (DUV) applications. Its laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) directly limits the operational power of laser systems [18].

Table 1: Laser-induced damage characteristics of CaF₂ crystal planes at 248 nm [18] [21]

| Crystal Plane | LIDT (Zero Probability) - Highly Polished | LIDT (Zero Probability) - Roughly Polished | Primary Damage Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| (100) | ~6.1 J/cm² | ~5.6 J/cm² | Damage morphology linked to {111} cleavage planes and <110> sliding systems. |

| (110) | ~6.1 J/cm² | ~5.6 J/cm² | Damage morphology linked to {111} cleavage planes and <110> sliding systems. |

| (111) | ~6.1 J/cm² | ~5.6 J/cm² | Damage morphology linked to {111} cleavage planes and <110> sliding systems. |

Key findings include:

- The rear surface of an optical window has a lower LIDT than the front surface due to higher localized electric field intensity [18].

- Superior surface polishing significantly increases the LIDT, as scratches and digs act as precursors that enhance light absorption and reduce mechanical strength [18].

- The specific damage morphology (e.g., cracking patterns) is intrinsically linked to the crystal's structural characteristics, particularly its cleavage planes {111} and slip systems {100} <110> [21].

Polymers and Paints

The response of organic materials to 248 nm laser irradiation varies significantly based on their composition.

Table 2: Chemical and physical changes in polymers and paints induced by 248 nm laser irradiation

| Material | Laser Parameters | Observed Chemical Changes | Observed Physical/Morphological Changes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyimide Film [5] | 248 nm, 20 ns, 7-18 mJ/cm², 6000-18000 pulses | - | Formation of Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures (LIPSS). Period ~200 nm, depth ~60 nm. Surface roughness (Ra) increased ~26x. Water contact angle decreased from 73.7° to 19.7°. |

| Egg Tempera Paints [20] [22] | 248 nm KrF laser | Degradation of binding medium (especially with inorganic pigments). Alterations in pigment molecular composition in some cases. | Various degrees of discoloration (ΔE), strongly dependent on pigment. Effects occur primarily in the surface layer. |

| Designed Polymer (Triazeno) [23] | 248 nm (absorption minimum) vs 308 nm (absorption max) | Surface oxidation for both wavelengths below ablation threshold. Different decomposition products above threshold. | Below threshold: smooth surface (chemical modification). Above threshold: pronounced differences in surface morphology between wavelengths. |

Metals: Aluminum (Al)

Laser ablation of aluminum in different ambient environments allows for controlled surface engineering, enhancing its mechanical properties [24].

Table 3: Surface and mechanical property changes of Al after 248 nm laser ablation in different ambients (100 torr, 100 pulses) [24]

| Ambient Environment | Laser Fluence (J/cm²) | Surface Structuring | Chemical Composition Changes | Change in Nanohardness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reactive (Ar) | 0.86 - 1.27 | Formation of nanoparticles, LIPSS, and other micro/nano structures. | Minimal change in composition. | Moderate increase due to laser-induced work hardening. |

| Reactive (O₂) | 0.86 - 1.27 | Development of complex structures enhanced by oxidation. | Formation of aluminum oxides (AlO, Al₂O₃) on the surface. | Significant increase due to the synthesis of hard alumina phases. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key research reagents and materials for studying 248 nm laser-induced changes

| Item | Function/Relevance |

|---|---|

| Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) Crystals | Model substrate for UV optical material studies. Used to determine LIDT and damage mechanisms related to crystal orientation [18] [21]. |

| Polyimide (PI) Films | A robust polymer substrate for studying laser-induced nanostructuring (LIPSS) and wettability changes due to its high thermal and chemical stability [5]. |

| Egg Tempera Paint Dosimeters | Well-defined, artificially aged model systems for simulating historical paints. Critical for evaluating laser-induced discoloration and binder degradation in conservation science [20] [22]. |

| High-Purity Aluminum Targets | A ductile metal substrate for investigating the interplay between laser ablation, ambient gas, and the synthesis of surface structures and hard phases like alumina [24]. |

| Controlled Atmosphere Chamber | Essential for experiments requiring reactive (O₂, N₂) or non-reactive (Ar, He) environments to study the role of ambient gas in laser-material interactions [24]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) of Optical Windows

This protocol outlines the procedure for determining the LIDT of materials like CaF₂ using a 1-on-1 damage test [18].

5.1.1 Materials and Equipment

- KrF excimer laser (248 nm wavelength, ~20 ns pulse duration)

- Test samples (e.g., CaF₂ with different crystal planes and polishing levels)

- Laser energy measurement device (e.g., joule meter)

- Dark-field optical microscope

- Computer with data analysis software

5.1.2 Procedure

- Sample Preparation: Prepare and clean samples. Divide into groups (e.g., highly polished vs. roughly polished) and characterize initial surface defects using dark-field microscopy [18].

- Laser Irradiation:

- Mount the sample in the laser path.

- For each test site, irradiate with a single laser pulse (1-on-1 mode).

- Systemically increase the laser fluence for subsequent test sites.

- For each fluence level, test 10 sites to determine damage probability [18].

- Damage Inspection:

- After irradiation, inspect each site under a dark-field optical microscope.

- Define an irreversible, significant change in the surface as "damage" [18].

- Record the number of damaged sites (N_damage) for each fluence level.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate damage probability for each fluence: P = Ndamage / Ntotal.

- Plot damage probability (P) versus laser fluence (F).

- Perform a linear fit of the data points. The fluence at which the fit line intersects zero probability is the zero-probability LIDT [18].

Protocol: Analyzing Laser-Cleaning Effects on Painted Artwork

This protocol describes a multi-technique approach to assess chemical and physical changes in paints after KrF laser irradiation, simulating conservation treatment [20] [22].

5.2.1 Materials and Equipment

- KrF excimer laser (248 nm)

- Model paint systems (e.g., artificially aged egg tempera on inert substrate)

- Profilometer

- Colorimeter

- FTIR Spectrometer

- Raman Spectrometer

- LIBS System

- Mass Spectrometer (e.g., DTMS, LDI-TOF-MS)

5.2.2 Procedure

- Sample Preparation and Baseline Characterization:

- Use well-defined, artificially aged paint dosimeters.

- Before irradiation, characterize a non-irradiated region (nv1) of the sample using all techniques listed to establish a baseline [20].

- Laser Irradiation:

- Irradiate adjacent sample regions using a range of laser fluences, from low (non-ablative, nv3) to high (ablative, nv2) [20].

- Ensure precise control over the beam spot and fluence.

- Post-Irradiation Analysis:

- Profilometry: Measure the irradiated areas to determine morphological changes and surface roughness (Ra) [20].

- Colorimetry: Measure the color (CIE Lab*) of irradiated and non-irradiated areas. Calculate the total color difference (ΔE) to quantify discoloration [20] [22].

- Chemical Analysis:

- Use FTIR and Raman spectroscopy to detect molecular-level changes in the binding medium and pigments [20] [22].

- Employ LIBS for elemental analysis and to stratigraphically probe the paint layer [20].

- Apply DTMS or LDI-TOF-MS to determine the nature of chemical changes in the organic components [20] [22].

- Data Integration and Interpretation:

- Correlate data from all techniques.

- Determine the fluence threshold for the onset of discoloration and binder degradation.

- Establish a safe operating window for cleaning where the varnish/contaminant is removed without altering the underlying paint [22].

The following diagram summarizes the workflow for analyzing laser-induced changes in artworks:

The analysis of laser-induced changes from 248 nm KrF excimer laser irradiation requires a systematic, multi-technique approach. The effects are profoundly material-dependent, necessitating careful a priori investigation on model systems. For optical crystals like CaF₂, the damage threshold and morphology are governed by surface polish and intrinsic crystallography. For polymers and paints, outcomes range from beneficial nanostructuring to detrimental discoloration and chemical degradation. In metals, the ambient environment critically influences the resulting surface chemistry and mechanical properties. The protocols provided herein offer a foundation for researchers to safely and effectively characterize these interactions, enabling the advancement of laser cleaning and processing technologies for optical, cultural heritage, and industrial applications.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing KrF Laser Cleaning on Diverse Optical Materials

KrF excimer laser operating at a wavelength of 248 nm is a cornerstone technology for the precise cleaning and processing of optical surfaces. Its effectiveness stems from its short wavelength, high photon energy, and ability to initiate primarily photochemical ablation processes, which minimize thermal damage to the substrate. The precision of this technique is not inherent but is meticulously controlled by four interdependent process parameters: fluence, pulse number, repetition rate, and spot size. This application note provides a detailed framework for researchers and scientists to define, optimize, and validate these critical parameters within the specific context of cleaning optical surfaces, ensuring reproducible, efficient, and safe outcomes.

Defining the Key Parameters and Their Physical Roles

Laser Fluence

- Definition: Laser fluence (Φ) is the ratio of a single pulse's energy (E) to the area (A) over which it is distributed (Φ = E/A). It is typically measured in Joules per square centimeter (J/cm²).

- Physical Role: Fluence is the primary driver of the ablation mechanism. It determines whether the interaction with the contaminant layer is dominated by photochemical, photothermal, or photomechanical processes [25] [16]. Operating below the ablation threshold of the target material leads to inefficient cleaning and heat accumulation, while excessive fluence can cause plasma shielding, reducing ablation efficiency and potentially damaging the underlying substrate [16].

Pulse Number

- Definition: The total count of laser pulses delivered to a single spot on the surface.

- Physical Role: The pulse number controls the total energy dose and the depth of material removal. In KrF excimer laser ablation of aged organic varnishes, multi-pulse irradiation can lead to incubation effects, where the ablation threshold fluence decreases with successive pulses due to the accumulation of defects [26] [16]. This effect must be accounted for to achieve uniform depth control.

Repetition Rate

- Definition: The frequency at which laser pulses are emitted, measured in Hertz (Hz) or kilohertz (kHz).

- Physical Role: The repetition rate governs the thermal load on the substrate. A high repetition rate can lead to significant heat accumulation between pulses, potentially increasing the removal rate of thin contaminants but also risking the formation of a heat-affected zone (HAZ). Conversely, a low repetition rate allows for longer cooling intervals, making it suitable for heat-sensitive materials [25] [27].

Spot Size

- Definition: The cross-sectional area of the laser beam at its focus on the workpiece surface. For a Gaussian beam, it is often defined by the 1/e² diameter.

- Physical Role: Spot size directly determines the laser fluence for a given pulse energy and defines the lateral resolution of the processing operation [26]. A smaller spot size enables finer feature definition but requires higher precision in beam delivery and sample positioning. The accurate measurement of spot size is critical for the correct calculation of fluence [26].

Table 1: Core Parameter Definitions and Their Roles in the Ablation Process

| Parameter | Definition | Unit | Primary Role in Ablation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluence | Pulse Energy / Beam Area | J/cm² | Determines the dominant ablation mechanism (photochemical vs. thermal) and removal efficiency. |

| Pulse Number | Total pulses on a single spot | Unitless | Controls ablation depth and is linked to incubation effects that lower the damage threshold. |

| Repetition Rate | Pulses emitted per second | Hz, kHz | Governs thermal accumulation on the substrate, affecting processing speed and HAZ. |

| Spot Size | 1/e² diameter of beam at focus | µm, mm | Defines lateral resolution and fluence for a given pulse energy. |

Quantitative Parameter Ranges and Interactions

The optimal value for each parameter is not absolute but is determined by the specific properties of the contaminant and the optical substrate. The following data, synthesized from research into laser cleaning and ablation, provides a foundational guideline for parameter selection.

Table 2: Experimentally-Derived Parameter Ranges for Different Cleaning Scenarios using a KrF (248 nm) Laser

| Application Scenario | Fluence Range (J/cm²) | Typical Repetition Rate | Key Considerations | Primary Ablation Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aged Triterpenoid Varnishes (e.g., Dammar, Mastic) [16] | 0.6 - 1.2 (Optimum) | Single to few Hz | "Optimum" fluence maximizes ablation yield per photon; low fluences cause photothermal melting, high fluences induce screening [16]. | Photochemical |

| Thin Oxide Layers & Paints [25] | Medium | 20 - 50 kHz | Medium-high repetition rate provides uniform energy distribution for even removal of thin layers. | Photothermal/Photochemical |

| Thick Rust, Coatings & Stubborn Contaminants [25] | High | < 10 kHz | Low repetition rate ensures high single-pulse energy for effective cracking and peeling. | Photomechanical |

| Microprocessing of Polymers (PU, PI, PC) [28] | Specific to polymer | Low (Single pulse) | Ablation depth is linear with pulse accumulation; minimal chemical change to remaining surface [28]. | Photochemical |

| Fine Micromachining (PMMA) [29] | - | - | Low thermal effect and high precision are paramount; requires precise overlap and scanning control. | Photochemical |

The parameters do not function in isolation but interact in complex ways. For instance, the effective fluence is a function of both pulse energy and spot size. Furthermore, a high repetition rate can effectively lower the ablation threshold through thermal accumulation, while a high number of pulses can do the same via incubation. A critical interaction is the pulse number-dependent decrease in ablation threshold fluence, which has been successfully modeled for silicon and is a vital consideration for controlling depth penetration and avoiding substrate damage [26].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Ablation Threshold Fluence

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to study the ablation of aged varnishes and silicon [26] [16].

1. Objective: To empirically determine the minimum fluence required to initiate ablation of a specific contaminant layer without damaging the underlying optical substrate.

2. Materials & Equipment:

- KrF excimer laser (248 nm)

- Beam profiling apparatus

- Attenuator

- Sample with contaminant/substrate

- White-light interferometer

3. Procedure: 1. Characterize Beam: Measure the beam's spatial profile and spot size at the sample plane using a beam profiler. For a non-Gaussian excimer beam, employ a method like the multi-pulse crater measurement to determine the effective spot diameter and profile [26]. 2. Prepare Sample: Mount the sample securely and ensure the surface is perpendicular to the beam. 3. Set Parameters: Fix the pulse number and repetition rate to low values. 4. Create Test Matrix: Fire a series of single pulses or a fixed, low number of pulses (e.g., 10 pulses) onto the sample surface, with each site at a systematically increased fluence. 5. Measure & Analyze: Use a white-light interferometer to measure the ablated depth at each site. Plot the ablated depth per pulse (d) versus the natural logarithm of the fluence (Φ). 6. Calculate Threshold: Fit the data to the relationship d = (1/α_eff) * ln(Φ/Φ_th), where α_eff is the effective absorption coefficient. The ablation threshold fluence, Φ_th, is the intercept on the fluence axis where the ablation depth becomes zero.

Protocol: Optimizing Fluence and Pulse Number for Uniform Layer Removal

This protocol is critical for applications like the removal of aged varnishes from sensitive surfaces [16].

1. Objective: To find the combination of fluence and pulse number that ensures complete contaminant removal while preserving a protective layer of varnish above the underlying paint or substrate.

2. Procedure: 1. Start with Threshold: Begin with the ablation threshold fluence (Φ_th) determined in Protocol 4.1. 2. Ablation Rate Curve: Perform ablation rate studies by firing a range of fluences (e.g., from 0.2 to 1.8 J/cm²) and measuring the depth ablated per pulse. Identify the "optimum fluence" which provides the highest ablation rate per pulse without inducing screening effects [16]. 3. Depth Profiling: At the optimum fluence, create a series of spots with an increasing number of pulses. Measure the ablated depth after each pulse number to establish a depth vs. pulse number calibration curve. 4. Safety Margin: Calculate the total pulse number required to ablate the contaminant layer down to a predetermined safe depth, ensuring the remaining layer thickness is greater than the optical penetration depth of the laser light in the varnish [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Equipment and Materials for KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning Research

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| KrF Excimer Laser | Pulsed UV laser source (248 nm). High photon energy enables photochemical ablation. | The core tool for all cleaning and ablation experiments [16] [28] [29]. |

| Beam Attenuator | Precisely controls the energy of the laser pulse reaching the sample. | Essential for conducting fluence-scaling experiments to find the ablation threshold [16]. |

| Beam Profiler | Measures the spatial intensity distribution and spot size of the laser beam at the focus. | Critical for accurate fluence calculation and process reproducibility [26]. |

| Aged Triterpenoid Varnish Films | Standardized test substrate (e.g., dammar, mastic). | Model system for studying the laser cleaning of historical artworks; exhibits depth-dependent aging gradients [16]. |

| Polymer Films (PU, PI, PC, PMMA) | Well-characterized substrates with known UV absorption. | Used for fundamental ablation studies and micromachining applications [28] [29]. |

| White-Light Interferometer | Non-contact 3D surface profiler for measuring ablation depth and surface topography. | Used to quantify ablation rates and inspect surface quality after processing [16]. |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) | Analytical technique that uses the laser plasma to perform elemental analysis of ablated material in real-time. | Can be used for depth-profiling and as an endpoint detection method to prevent substrate damage [16]. |

KrF-excimer laser cleaning, operating at a wavelength of 248 nm, has emerged as a powerful, dry, and selective method for decontaminating sensitive surfaces in the semiconductor industry [30]. This advanced cleaning technology offers a solution to the limitations of conventional wet cleaning processes, which often involve hazardous solvents and can be inefficient at removing sub-micrometer particles [1] [30]. Laser cleaning is particularly valuable for cleaning wafer surfaces and semiconductor components where even infinitesimally small contaminants can lead to device defects and failures [31]. The process leverages precise laser ablation to remove organic contaminants, particles, and other undesirable layers without damaging the underlying substrate, providing a high degree of control and enabling in-situ monitoring [30].

Fundamental Mechanisms of KrF Excimer Laser Cleaning

The interaction between a 248 nm laser beam and material involves complex physico-chemical processes. The primary mechanisms responsible for cleaning are laser thermal ablation, laser thermal stress, and plasma shock waves [1]. For KrF excimer laser cleaning of organic contaminants from wafers, the laser thermal ablation mechanism is often dominant.

Laser Thermal Ablation

When a pulsed 248 nm laser beam irradiates a contaminated wafer surface, the contaminant layer (e.g., photoresist) absorbs the laser energy, causing its temperature to rise rapidly. If the energy exceeds the contaminant's vaporization threshold, it leads to instant evaporation, combustion, or decomposition [1]. The high-photon energy of the 248 nm wavelength (5 eV) can also directly break molecular bonds in organic contaminants through photochemical effects, transforming them into a loose state that is more easily removed [1]. The ablation process is highly selective when the ablation threshold of the contaminant is lower than that of the substrate, allowing for effective removal without substrate damage [1].

Role of Wavelength and Pulse Duration

The short wavelength (248 nm) and nanosecond pulse duration of the KrF excimer laser are key to its effectiveness [10] [30]. Organic materials and degraded varnishes strongly absorb radiation in the UV region, enabling highly selective removal. The short pulse duration confines thermal energy, minimizing heat diffusion into the substrate and allowing for precise layer-by-layer material removal [10].

Experimental Protocols for Wafer Surface Cleaning

Protocol 1: Removal of Organic Photoresist from Silicon Wafers

This protocol details a method for removing spin-coated photoresist, a common organic contaminant, from silicon wafers using a KrF excimer laser [30].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Silicon Wafer Substrate | Base material to be cleaned. |

| Photoresist (PFR 7790G) | Representative organic contaminant for protocol validation. |

| KrF Excimer Laser | Light source (λ=248 nm, pulse duration=20 ns). |

| Laser Fluence | Energy density per pulse (e.g., 0.1-0.3 J/cm²). |

| Beam Homogenizer | Creates a uniform energy profile across the beam spot. |

| Profilometer | Measures ablation depth and verifies cleaning efficacy. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Sample Preparation: Clean silicon wafers are spin-coated with photoresist (e.g., PFR 7790G) to a uniform thickness, typically around 1.2 μm [30].

- Laser Setup: Configure the KrF excimer laser (e.g., Lambda Physik LPX 100). Pass the beam through a homogenizer to ensure a top-hat energy profile. Use an external lens to focus the beam onto the wafer surface [30].

- Parameter Calibration: Set the laser fluence below the ablation threshold of silicon but above that of the photoresist. Fluence values between 0.1 J/cm² and 0.3 J/cm² are typical [30].

- Cleaning Procedure: Irradiate the coated wafer surface with the laser. The number of pulses (N) required is a function of the coating thickness (d) and the ablation rate (δ), given by N = d/δ. The wafer can be translated under the beam using a computer-controlled X-Y stage for large-area processing [30].

- Efficacy Assessment: Use a profilometer to measure the ablation depth and confirm complete removal of the photoresist layer. Inspect the surface for any residual contamination or damage.

Quantitative Data and Process Optimization

Ablation rates for photoresist at different fluences are quantified in the table below [30].

Table 1: Ablation rate of photoresist at 248 nm for different fluence values

| Laser Fluence (J/cm²) | Ablation Rate (μm/pulse) |

|---|---|

| 0.10 | 0.05 |

| 0.20 | 0.07 |

| 0.30 | 0.09 |

The relationship between the number of laser pulses (N) and the thickness of the removed layer (d) can be modeled linearly for a constant fluence: d = δ · N, where δ is the ablation rate per pulse [30]. This model is crucial for predicting the appropriate number of pulses needed to remove a contaminant layer of known thickness without damaging the substrate.

Protocol 2: In-situ Monitoring and Optimization of Laser Cleaning

This protocol leverages non-invasive analytical techniques to monitor the cleaning process in real-time, which is critical for optimizing parameters and ensuring safety, especially for valuable components [10].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| KrF Excimer Laser Workstation | Includes galvanometric mirrors for beam steering. |

| Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) | Non-invasive cross-sectional imaging of layer thickness. |

| Reflection FT-IR Spectroscopy | Identifies molecular composition of surface chemicals. |

| Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) | Monifies fluorescence properties of surfaces. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Pre-cleaning Assessment: Perform initial OCT and Reflection FT-IR measurements on the wafer or component to determine the initial thickness and chemical identity of the contaminant or varnish layer [10].

- Laser Parameter Definition: Set the initial laser fluence (e.g., between 0.1 and 1.1 J/cm²) and a low number of pulses (N) [10].

- Iterative Cleaning and Monitoring:

- Apply a limited number of laser pulses to a test area.

- Use OCT to measure the remaining layer thickness and confirm material removal without substrate damage.

- Use Reflection FT-IR to detect chemical changes and verify the removal of target compounds (e.g., aged varnishes, oxalates) [10].

- Parameter Optimization: Gradually adjust the fluence and pulse count based on the feedback from OCT and FT-IR until the optimal parameters for complete contaminant removal with no substrate alteration are identified.

- LIF Monitoring: Use Laser-Induced Fluorescence (LIF) with the same laser beam at significantly attenuated energy densities to potentially provide on-line feedback during the cleaning process [10].

Results and Discussion

Efficacy and Process Window

KrF excimer laser cleaning at 248 nm has proven highly effective at removing organic contaminants from silicon wafers. The process window is defined by the ablation thresholds of the contaminant and the substrate [1]. Successful cleaning without substrate damage is achieved when the laser fluence is maintained above the contaminant's threshold but below the substrate's. For example, in cleaning martensitic stainless steel, a fluence between 0.41 J/cm² and 8.25 J/cm² successfully removed sulfides without damaging the steel substrate [1].

Advantages Over Conventional Methods

This dry laser cleaning process offers significant advantages, making it a promising alternative to conventional methods [1] [30].

- Environmental Friendliness: It eliminates or drastically reduces the need for hazardous chemical solvents, aligning with green manufacturing principles [30].

- Precision and Selectivity: The high absorption of 248 nm light by organic materials and the ability to control fluence and pulse count enable selective, layer-by-layer removal [10].

- Non-contact Process: The laser cleaning process avoids mechanical contact, eliminating the risk of surface scratching or mechanical stress induced by physical contact methods.

- Potential for In-situ Monitoring and Automation: The process is compatible with real-time monitoring techniques like OCT, FT-IR, and LIF, paving the way for automated, closed-loop control systems for high-reliability manufacturing [10].

This application note demonstrates that KrF excimer laser cleaning at 248 nm is a highly effective, precise, and environmentally friendly technology for cleaning wafer surfaces and semiconductor components. The detailed protocols for removing organic contaminants and for in-situ monitoring provide a framework for researchers and engineers to implement this advanced cleaning method. The quantitative data on ablation rates and the clear process windows enable the optimization of cleaning parameters for specific applications. As the semiconductor industry continues to demand higher purity and smaller critical dimensions, the adoption of controlled laser cleaning techniques is expected to grow, driving advancements in yield and device performance.