Laser Cleaning vs. Plasma Cleaning for Optical Components: A Scientific Comparison for Precision Applications

This article provides a comprehensive, science-driven comparison between laser and plasma cleaning technologies for optical components, tailored for researchers and scientists.

Laser Cleaning vs. Plasma Cleaning for Optical Components: A Scientific Comparison for Precision Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive, science-driven comparison between laser and plasma cleaning technologies for optical components, tailored for researchers and scientists. It explores the fundamental principles of each method, detailing their specific mechanisms for contaminant removal on surfaces like lenses, mirrors, and filters. The content covers critical application methodologies, process optimization strategies, and troubleshooting for high-stakes environments. A direct, evidence-based comparison equips professionals in biomedical and clinical research to select the optimal cleaning technique for enhancing optical performance, ensuring experimental integrity, and improving device reliability.

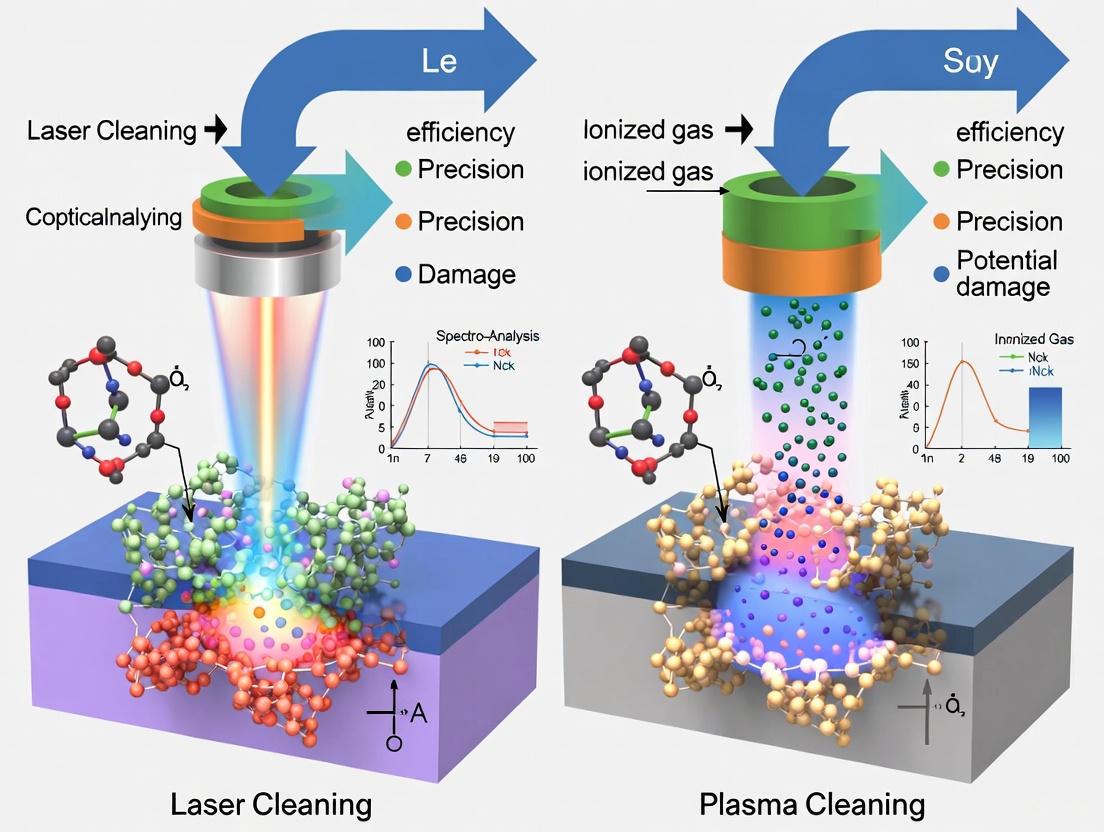

Understanding the Core Principles of Laser and Plasma Cleaning

Laser cleaning and plasma cleaning represent two advanced, dry techniques for decontaminating surfaces, each operating on distinct physical principles and suited for different applications. Laser cleaning utilizes focused pulsed laser beams to selectively ablate contaminants through a process of ablative photodegradation, whereby the energy of photons is absorbed, breaking chemical bonds in the surface material [1]. In contrast, plasma cleaning employs ionized gas to remove organic matter through chemical reactions and physical sputtering, often at a microscopic level [1] [2]. Within the context of optical components research, where preserving nanoscale surface integrity and optical performance is paramount, the choice between these methods is critical. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of laser and plasma cleaning technologies, drawing on recent experimental studies to delineate their mechanisms, efficacy, and optimal use cases for researchers and scientists.

Principles of Operation

Laser Cleaning and Ablative Photodegradation

Laser cleaning is a non-contact process that removes contaminants by projecting high-energy pulsed laser beams onto a surface. The fundamental mechanism, ablative photodegradation, involves the laser energy being preferentially absorbed by the contaminant layer. This absorption leads to rapid heating, causing the contaminants to undergo vaporization or ablation, effectively breaking chemical bonds and turning them into gas or fine debris [1] [3]. The process is governed by the principle of selective photothermolysis, where the laser parameters—wavelength, pulse duration, and fluence—are tuned to ensure the contaminant's ablation threshold is exceeded while the substrate remains undamaged [4] [5]. For instance, a mid-infrared laser at 2.8 µm is highly absorbed by organic contaminants like epoxy but transmitted through many semiconductor substrates, enabling precise cleaning without substrate damage [5]. The process can involve photothermal, photophysical, and photochemical interactions, with shorter pulses (e.g., picosecond or femtosecond) reducing thermal damage to the underlying material [6].

Plasma Cleaning Mechanisms

Plasma cleaning relies on an ionized gas (plasma) containing a mixture of ions, electrons, and neutral reactive species. This plasma is typically generated by applying a high voltage to a gas like oxygen or argon under low pressure [2] [7]. The cleaning action occurs through two primary mechanisms:

- Chemical Reaction: Reactive species in the plasma, such as oxygen radicals, interact with organic contaminants on the surface, breaking them down into volatile byproducts like CO₂ and H₂O that are then evacuated by the vacuum system [2] [8].

- Physical Sputtering: Ions in the plasma gain energy from the electric field and bombard the surface, physically dislodging contaminants through momentum transfer [8]. Unlike laser cleaning, plasma treatment is often non-selective, uniformly affecting the entire exposed surface. While effective for removing micro- and nanoscale organic contaminants, it can potentially modify the surface chemistry and morphology of the substrate [7] [5].

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key experimental findings from recent studies, highlighting the performance of each cleaning method in specific applications.

Table 1: Experimental results for laser cleaning applications.

| Material/Cleaning Target | Laser Parameters | Key Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| TC4 Titanium Alloy (Oxide Film) | 1064 nm wavelength, 5.27 J/cm², 300 kHz, Gaussian pulse | Lower surface damage, reduced oxygen content, and lower roughness vs. Flat-top pulse. | [4] |

| HDPE Polymer (Bond Breaking) | 4th Harmonic (266 nm), 3-10 mJ pulse energy, 20 Hz | Most effective at directly breaking C-H bonds, evident from Hα peak at 656.3 nm; minimal ablation. | [9] |

| Silicon Photonics (Epoxy Contaminant) | 2.8 µm wavelength, short pulses | Selective removal of organic epoxy without damaging the underlying silicon substrate. | [5] |

Table 2: Experimental results for plasma cleaning applications.

| Material/Cleaning Target | Plasma Parameters | Key Results | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemically Coated Optical Components (Organic Contaminants) | Low-pressure oxygen/argon RF plasma | Restored optical transmittance, quantitative relationship between functional groups and transmittance established. | [2] [8] |

| Silicon Carbide (SiC) Surface | Oxygen plasma | Reduced surface roughness from 1.090 nm to 0.055 nm. | [8] |

| Gold Mirror (Carbon Contamination) | RF Plasma | Efficiently removed carbon contaminants and restored original optical performance without secondary contamination. | [8] |

Table 3: Direct comparison of laser and plasma cleaning characteristics.

| Feature | Laser Cleaning | Plasma Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Process Mechanism | Focused laser energy (Ablative photodegradation) | Ionized gas interaction (Chemical/Physical) |

| Selectivity | High (Wavelength-dependent absorption) | Low (Blanket treatment) |

| Suitable Contaminants | Rust, coatings, paints, oxides, organic particles [1] [3] | Organic films, micro-particles, carbon contamination [2] [8] |

| Spatial Precision | High (Can be localized to sub-micron spots) | Low (Treats entire exposed surface) |

| Impact on Surface | Minimal substrate damage if tuned correctly; can alter roughness [4] | Can activate surface, improve adhesion, risk of over-etching or surface modification [7] [5] |

| Throughput | Fast for localized cleaning; slower for large areas | Slower for large areas, but good for batch processing of small parts |

| Environmental Impact | Dry process, no chemicals, minimal waste [3] | Low waste generation, uses process gases [7] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Laser Cleaning of Oxide Films on TC4 Titanium Alloy

This protocol is adapted from a study investigating the removal of oxide films using different laser spot patterns [4].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Cut TC4 titanium alloy into 25 mm × 25 mm × 3 mm samples. Clean surfaces to remove any gross contamination. Characterize the native oxide film (approx. 10 µm thick) using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and metallurgical microscopy.

- 2. Laser Setup:

- Laser Type: Pulsed fiber laser (e.g., 1064 nm wavelength).

- Spot Patterns: Compare Gaussian and Flat-top pulse profiles.

- Key Parameters: Set laser energy density to 5.27 J/cm², repetition frequency to 300 kHz, and scanning speed to 6000 mm/s. The spot diameter is typically 130 µm.

- Equipment Configuration: Mount the laser output on an industrial robot. Use a scanning galvanometer system with a focusing lens to direct the beam across the sample surface in a pre-programmed path.

- 3. Cleaning Procedure: Irradiate the sample surface with the laser according to the set parameters. The laser beam is scanned over the surface to ensure full coverage of the target area.

- 4. Post-Cleaning Analysis:

- Microscopy: Use SEM to examine surface micromorphology and confirm oxide removal.

- Elemental Analysis: Employ Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) with SEM to measure oxygen content on the cleaned surface versus an untreated control.

- Surface Roughness: Quantify using a profilometer or roughness-measuring instrument (e.g., Mitutoyo SJ-140).

Protocol: Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning of Optical Coatings

This protocol is based on a study that combined experiments and molecular dynamics simulations to clean organic contaminants from sol-gel SiO₂ chemical coatings [2] [8].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Prepare chemical-coated fused silica samples using a dip-coating method with a sol-gel SiO₂ solution. Apply a controlled organic contamination layer to the coated surface.

- 2. Plasma Reactor Setup:

- Reactor Type: Low-pressure capacitive-coupled RF plasma system.

- Gas Composition: Use oxygen (O₂) or argon (Ar) as the process gas.

- Key Parameters: Optimize discharge power and gas pressure based on Langmuir probe measurements to achieve desired plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature.

- 3. Cleaning Procedure: Place the contaminated sample inside the plasma reactor chamber. Evacuate the chamber to low pressure. Introduce the process gas and ignite the plasma. Treat the sample for a predetermined duration.

- 4. Post-Cleaning Analysis:

- Optical Performance: Measure the transmittance of the optical component at the target wavelength (e.g., 355 nm) to quantify recovery.

- Surface Cleanliness: Use techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) to characterize the removal of organic functional groups.

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation: Complement experimental results with a Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) model to simulate the interaction between plasma species and organic contaminants at the atomic scale, revealing reaction mechanisms.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental decision-making workflow for selecting between laser and plasma cleaning, based on the nature of the contamination and the substrate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 4: Key equipment and materials for laser and plasma cleaning research.

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Pulsed Fiber Laser (1064 nm) | Primary energy source for ablation; nanosecond pulses offer a balance of cost and effectiveness for many materials. | Removing oxide films from titanium alloys [4]. |

| Mid-IR Laser (2.8-3 µm) | Selectively targets organic contaminants due to strong absorption by O-H and C-H bonds, while transmitting through semiconductors. | Cleaning epoxy from sensitive silicon photonics dies without substrate damage [5]. |

| Low-Pressure RF Plasma Reactor | Generates low-temperature plasma for contaminant removal via chemical reactions and physical sputtering in a controlled vacuum environment. | Removing organic contamination from large-aperture optical components with chemical coatings [2] [8]. |

| Langmuir Probe | Diagnostic tool for characterizing plasma parameters (e.g., electron temperature, ion density) within the reactor. | Optimizing plasma discharge power and gas pressure for efficient cleaning [8]. |

| Sol-Gel SiO₂ Coating | A common, research-relevant chemical coating for optical components, susceptible to organic contamination. | Used as a standardized substrate for testing and optimizing cleaning protocols for optics [8]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | For high-resolution imaging of surface morphology before and after cleaning to assess effectiveness and substrate damage. | Analyzing the micromorphology and elemental composition (via EDS) of a cleaned TC4 titanium alloy surface [4]. |

| Spectrometer (LIBS/OES) | Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy or Optical Emission Spectroscopy for in-situ monitoring of the ablation/cleaning process and elemental analysis. | Monitoring the presence of Hα peaks during laser-induced HDPE bond breaking [9] or analyzing plasma species. |

For the researcher in optics and photonics, the choice between laser and plasma cleaning is not a matter of superiority but of strategic application. Laser cleaning excels in precision, offering targeted removal of specific contaminants—from thick oxides on metals to epoxy droplets on photonic integrated circuits—with minimal impact on the surrounding substrate [4] [5]. Its principle of ablative photodegradation provides unparalleled control. Plasma cleaning, conversely, offers comprehensive uniformity, effectively eliminating nanoscale organic films and activating surfaces across entire components, making it ideal for preparing surfaces for bonding or restoring the transmittance of large optics [2] [8]. The experimental data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a foundation for making an evidence-based selection. Ultimately, integrating both technologies into a research or production workflow may provide the most versatile solution, leveraging the strengths of each to meet the extreme cleanliness and integrity demands of next-generation optical components.

In the realm of high-precision optical systems, such as those found in intense laser facilities and inertial confinement fusion research, the performance and longevity of large-aperture optical components are critically dependent on surface cleanliness. Organic contamination on surfaces like anti-reflective or high-reflective coatings can lead to irreversible damage and rapid degradation of optical performance under laser irradiation, reducing the laser damage threshold by approximately 60% [8]. For optical components requiring atomic-level precision, two advanced cleaning technologies have emerged as principal contenders: plasma cleaning and laser cleaning. Plasma cleaning utilizes an ionized gas containing reactive species (ions, electrons, and neutral particles) to remove contaminants at a molecular level, while laser cleaning employs concentrated laser beams to vaporize or ablate unwanted materials through rapid thermal interactions [1] [7].

The selection between these methods represents a significant technical decision for researchers and optical engineers. Plasma technology operates through chemical reactions between reactive plasma species and surface contaminants, effectively breaking them down into volatile byproducts [10]. Laser cleaning, conversely, relies primarily on photophysical and photothermal mechanisms where pulsed laser energy is absorbed by the contamination layer, leading to its removal through vaporization, thermal stress, or explosive evaporation [11] [12]. For optical components with delicate chemical coatings and extreme performance requirements, understanding the atomic-level interactions of these cleaning processes is essential for optimizing cleaning protocols and preventing substrate damage.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Plasma Cleaning: Atomic-Level Interactions

Plasma cleaning operates through the generation of partially ionized gas containing a complex mixture of reactive species including electrons, positive ions, neutral atoms, molecules in excited states, and UV light [13] [8]. When these species interact with contaminated surfaces, multiple atomic-level processes occur simultaneously. The reactive particles collide with organic contaminants, transferring energy and breaking chemical bonds through radical-driven pathways [8]. Simultaneously, UV radiation from the plasma contributes to molecular bond breaking, while ion bombardment provides physical energy transfer that disrupts contaminant layers.

The efficacy of plasma cleaning is governed by key parameters including discharge power, gas composition, pressure, and treatment duration. Experimental studies combining Langmuir probe measurements and emission spectroscopy have demonstrated that these parameters directly influence plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature, which in turn determine cleaning efficiency [8]. Reactive molecular dynamics (RMD) simulations have revealed that the primary cleaning processes occur on nanosecond timescales at atomic spatial scales, with the reactive species in the plasma (particularly oxygen radicals in oxygen-based plasmas) chemically reacting with carbon-based contaminants to form volatile reaction products such as CO and CO₂ that are subsequently removed from the surface [8].

Laser Cleaning: Fundamental Mechanisms

Laser cleaning employs high-energy laser pulses to remove contaminants through several interconnected mechanisms. The primary removal mechanisms include:

Ablation Gasification Effect: When a high-energy laser beam strikes a contaminant layer, the absorbed energy causes rapid temperature increase exceeding the material's gasification point, leading to instantaneous vaporization and removal [11]. During this process, the vaporized material and surrounding air can be ionized to form plasma, which generates a high-pressure shock wave that further contributes to contaminant removal [11] [12].

Vibration Stripping Effect: The rapid thermal expansion of the contaminant layer creates thermal stress that exceeds the adhesion force between the contaminant and substrate, causing mechanical detachment [11]. Additionally, interference patterns from reflected laser beams within the contaminant layer create high-energy resonant waves that accelerate removal [11].

Explosion Stripping Effect: Moisture or air trapped in pores and gaps of the contaminant layer rapidly expands when heated by the laser, generating pressure that overcomes adhesion forces and causes explosive removal of the material [11].

The laser cleaning process is governed by precise parameter control, with energy density needing to remain between two critical thresholds: the contamination removal threshold and the substrate damage threshold [12]. This threshold effect enables self-limiting cleaning where contaminants are removed without damaging the underlying substrate.

Comparative Analysis: Plasma vs. Laser Cleaning

Technical Performance Comparison

Table 1: Technical Performance Comparison of Plasma and Laser Cleaning

| Parameter | Plasma Cleaning | Laser Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Cleaning Mechanism | Chemical reaction with reactive species & ion bombardment [13] [8] | Thermal ablation, vibration stripping, & shock waves [11] [12] |

| Spatial Resolution | Macroscopic to microscopic (uniform coverage) [10] | High precision (can target specific areas) [7] |

| Contaminant Types | Organic residues, micro-particles, microbial contaminants [13] [8] | Oxide films, paint layers, rust, biofilms [1] [11] [14] |

| Surface Modification | Activates surface, increases surface energy, improves wettability [13] [10] | Can alter surface roughness, minimal chemical modification [11] [7] |

| Penetration Capability | Reaches complex geometries and tight spots [10] | Line-of-sight process, limited for hidden areas [7] |

Table 2: Process Characteristics and Applications Comparison

| Characteristic | Plasma Cleaning | Laser Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Operating Environment | Low-pressure vacuum chambers or atmospheric pressure [13] [10] | Ambient atmosphere, typically no enclosure required [1] |

| Typical Treatment Time | 2-120 seconds [13] | Varies with contamination thickness and area [12] |

| Suitable Materials | Metals, plastics, ceramics, glass, elastomers [13] | Metals, ceramics, polymers, artworks [1] [11] |

| Primary Industries | Semiconductor, medical devices, optics, electronics [13] [8] | Aerospace, automotive, marine, art conservation [1] [11] |

| Environmental Impact | Low, minimal chemical usage [13] [10] | Low, minimal waste generation [11] |

Applications in Optical Components Research

For optical components research, each cleaning method offers distinct advantages depending on the specific application requirements:

Plasma Cleaning Applications: Plasma cleaning excels in applications requiring molecular-level cleanliness and surface activation without material removal. Studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in restoring the optical transmittance of large-aperture optical components with chemical coatings by removing organic contaminants that cause laser-induced damage [8]. The technology is particularly valuable for cleaning delicate optical components with complex geometries where uniform coverage is essential. Research has shown that low-pressure oxygen plasma can effectively remove carbon-based contaminants from optical surfaces, restoring near-baseline optical performance through radical-driven pathways [8].

Laser Cleaning Applications: Laser cleaning has proven effective for removing specific contaminant layers from optical components, with research focusing on real-time monitoring using techniques like laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) to ensure optimal cleaning without substrate damage [14]. The precision of laser cleaning allows for selective removal of contaminants from specific areas without affecting surrounding regions, making it valuable for delicate optical components where controlled material removal is required. Studies have successfully demonstrated laser cleaning of various contaminants while preserving the substrate's structural integrity [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Plasma Cleaning Experimental Protocol for Optical Components

Objective: To remove organic contaminants from chemical-coated optical components while restoring optical transmittance and laser damage resistance.

Materials and Equipment:

- Low-pressure plasma cleaning system with RF power source

- Vacuum chamber with gas flow control system

- Langmuir probe for plasma characterization

- Optical emission spectrometer

- Reference optical components with sol-gel SiO₂ chemical coatings

- Oxygen and argon gas sources

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare chemical-coated fused silica samples using dip-coating method with sol-gel SiO₂ at 355 nm wavelength. Maintain consistent coating parameters: 25°C temperature, 85 mm/min pull speed, and post-treatment with ammonia and HMDS for 24 hours [8].

Plasma System Setup:

- Place samples in vacuum chamber and evacuate to appropriate pressure

- Introduce oxygen or oxygen-argon gas mixture at controlled flow rates

- Apply RF power (typically 13.56 MHz) to generate capacitive-coupled discharge

- Maintain low-pressure environment (typically 10-100 mTorr) [8]

Process Monitoring:

- Use Langmuir probe to measure plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature

- Employ optical emission spectroscopy to identify reactive species concentrations

- Monitor discharge power (typically 100-500W) and gas pressure as critical parameters [8]

Quality Assessment:

- Measure optical transmittance before and after cleaning

- Characterize surface morphology using SEM/EDS analysis

- Evaluate laser damage threshold recovery

- Assess cleaning uniformity across large apertures

Key Parameters from Recent Studies: Recent research has established that optimal cleaning occurs within specific process windows: discharge power significantly affects electron temperature and ion density, while gas composition influences the types of reactive species generated. Molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that bombardment energy and ion flux are critical factors in the efficiency of organic contaminant removal [8].

Laser Cleaning Experimental Protocol with LIBS Monitoring

Objective: To remove marine biofilm layers from aluminum alloy surfaces while monitoring cleaning quality in real-time and preventing substrate damage.

Materials and Equipment:

- Nanosecond pulsed fiber laser (200W maximum power, 1064 nm wavelength)

- Galvanometer scanning system

- Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) system with spectrometer (300-800 nm range)

- 6061 aluminum alloy samples with marine biofilm layers

- Scanning Electron Microscope with EDS analyzer

- Digital microscope for surface morphology examination

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare 6061 aluminum alloy specimens (150 mm × 40 mm × 2 mm)

- Immerse in marine environment for 3 months to develop natural biofilm layers

- Characterize initial biofilm thickness (40-65 μm for hard attachments, 20-50 μm for EPS layers) [14]

Laser Cleaning Setup:

- Configure laser parameters: pulse width (30-240 ns), repetition rate, spot size

- Set scanning pattern ('S' trajectory) with rectangular scanning path (15 mm × 15 mm)

- Adjust laser power (typically 20-160W based on contamination type) [14]

LIBS Monitoring Implementation:

- Position fiber optic probe 80 mm from workpiece surface

- Collect plasma spectra during cleaning process (300-800 nm wavelength range)

- Monitor characteristic elemental peaks (C, O, Al, Ca, Mg) [14]

- Establish "reference spectrum" for optimal cleaning endpoint determination

Process Optimization:

- Calculate Pearson correlation coefficient between acquired spectra and reference spectrum

- Adjust laser parameters based on real-time spectral feedback

- Determine optimal cleaning parameters through regression fitting of spectral data [14]

Post-Cleaning Analysis:

- Perform EDS analysis to verify elemental composition changes

- Examine surface morphology using SEM

- Assess cleaning completeness and substrate damage

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Plasma and Laser Cleaning Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sol-gel SiO₂ coating | Creates uniform chemical coatings on optical components | Plasma cleaning studies on model contaminated optics [8] |

| Oxygen and Argon gases | Process gases for plasma generation | Creating reactive species in plasma cleaning [8] |

| Ammonia and HMDS | Post-treatment reagents for chemical coatings | Enhancing coating durability before contamination studies [8] |

| Marine biofilm layers | Representative organic contamination | Testing laser cleaning effectiveness on natural biofilms [14] |

| Langmuir probe | Measures plasma parameters (potential, density, temperature) | Characterizing plasma conditions during cleaning [8] |

| LIBS spectrometer | Real-time monitoring of elemental composition | Determining cleaning endpoints during laser processes [14] |

Visualization of Cleaning Mechanisms and Processes

Diagram 1: Plasma cleaning process workflow showing the sequence from gas introduction to surface cleaning.

Diagram 2: Laser cleaning process with real-time LIBS monitoring and feedback control system.

Plasma and laser cleaning technologies offer complementary approaches for addressing contamination challenges in optical components research. Plasma cleaning excels in applications requiring molecular-level cleanliness, surface activation, and uniform coverage of complex geometries, particularly for removing organic contaminants from delicate optical coatings. The atomic-level interactions between reactive plasma species and contaminants follow radical-driven pathways that efficiently restore optical performance without damaging underlying substrates.

Laser cleaning provides high-precision removal of specific contaminant layers with real-time monitoring capabilities, making it particularly valuable for applications where controlled material removal is essential. The integration of LIBS monitoring enables precise endpoint detection and optimization of cleaning parameters, ensuring complete contaminant removal while preserving substrate integrity.

For optical components research, the selection between these technologies depends on specific application requirements, including the nature of contaminants, substrate sensitivity, geometrical considerations, and desired post-cleaning surface properties. Both techniques offer environmentally friendly alternatives to traditional chemical cleaning methods and continue to evolve through advanced process monitoring and control methodologies. As research progresses, the combination of experimental approaches with molecular dynamics simulations provides increasingly detailed understanding of the fundamental interactions at the atomic level, enabling further optimization of these critical cleaning technologies for high-performance optical systems.

The performance and longevity of optical components are critically dependent on surface cleanliness. Contaminants such as organic residues, particles, and oxides can severely compromise optical performance by increasing light scattering, creating hot spots through radiation absorption, and reducing laser-induced damage thresholds [15] [16]. In research environments, particularly those involving intense laser systems like inertial confinement fusion facilities, surface contaminants on optical components can reduce laser damage thresholds by approximately 60% [8]. Traditional cleaning methods, including mechanical grinding, chemical solvents, and ultrasonic cleaning, often present challenges such as difficulty in localization, high residue, low efficiency, environmental pollution, and health hazards [17]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates two advanced cleaning technologies—laser cleaning and plasma cleaning—for addressing these contaminant targets on optical surfaces, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform method selection.

Plasma Cleaning

Plasma cleaning is a surface treatment process that utilizes ionized gas (plasma) containing active species such as ions, electrons, and neutral particles to remove contaminants from various materials [7]. The process is initiated by applying a high voltage to a gas, leading to ionization and the creation of reactive ions and free radicals that interact with surface contaminants, causing decomposition [7]. This technology not only cleans surfaces but can also modify surface properties to improve adhesion and wettability for subsequent treatments [7]. Plasma cleaning is particularly noted for its effectiveness on intricate geometries and micro-scale contaminants, making it suitable for delicate optical components [7].

Laser Cleaning

Laser cleaning employs concentrated laser beams to remove unwanted materials from surfaces through thermal interaction [7]. The process directs a high-powered laser beam onto the surface, where the energy is absorbed by contaminants, causing them to vaporize or ablate [7]. This method leaves minimal residue as contaminants are converted into gas or fine debris that can be easily removed [7]. Laser cleaning is recognized for its precision, speed, and effectiveness in dealing with heavily soiled surfaces, including rust, paint, and other tough contaminants on metals [7]. The technology is particularly advantageous for its non-invasive nature, which helps maintain the integrity of the base material [7].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Removal Efficacy for Primary Contaminant Types

Organic Residues: Plasma cleaning excels in removing organic contamination through a chemical reaction process where plasma's UV energy breaks organic bonds on surface contaminants, causing them to volatilize [18]. Experimental studies on low-pressure plasma cleaning of organic contamination from chemically coated surfaces demonstrate that oxygen plasma effectively removes organic contaminants from optical components, restoring near-baseline optical performance through radical-driven pathways [2] [8]. Laser cleaning also effectively removes organic contaminants, though its mechanism is primarily thermal rather than chemical.

Particles and Dust: Laser cleaning shows superior performance for removing particulate contamination through its ablation mechanism. The focused laser energy effectively dislodges and removes particles from surfaces without contact [7]. Plasma cleaning can remove particles but may be less effective for larger, non-adhered particulates compared to laser methods.

Oxides: Laser cleaning has proven particularly effective for oxide removal from metal surfaces. The technology is widely used for rust removal from various metal substrates [7] [18]. Plasma cleaning can remove oxides but may be less efficient for thicker oxide layers compared to laser cleaning.

Table 1: Contaminant Removal Efficacy Comparison

| Contaminant Type | Plasma Cleaning Efficacy | Laser Cleaning Efficacy | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Residues | High (chemical breakdown) | Medium-High (thermal ablation) | Plasma uses radical-driven pathways [8] |

| Fine Particles | Medium | High (non-contact removal) | Laser effective for non-adhered particulates [7] |

| Oxides | Medium | High (efficient ablation) | Laser preferred for thick oxide layers [7] |

| Biofilms | Limited data | High (proven efficacy) | Laser successfully removes marine biofilms [14] |

| Micro-scale Contaminants | High (excellent for intricate geometries) | Medium (depends on laser focus) | Plasma superior for complex microstructures [7] |

Process Parameters and Experimental Results

Plasma Cleaning Parameters: Experimental studies on low-pressure plasma cleaning have identified key parameters that influence cleaning efficacy. Research combining experimental and molecular dynamics studies has shown that discharge power, gas pressure, plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature significantly affect cleaning performance [2] [8]. Optimal parameters for organic contaminant removal from optical components typically involve oxygen or argon gas mixtures, with specific combinations of these parameters determined through Langmuir probe and emission spectrometer measurements [8].

Laser Cleaning Parameters: Laser cleaning effectiveness is predominantly determined by process parameters including laser power, pulse width, frequency, and scanning speed [17]. Experimental research on removing Al metal layers from ceramic substrate surfaces demonstrated that a laser with power of 120 W, pulse width of 200 ns, frequency of 240 kHz, and speed of 6000 mm/s could effectively remove a 50 μm Al metal layer in a single cleaning cycle without damaging the ceramic substrate [17]. Studies on marine biofilm removal from aluminum alloy surfaces utilized nanosecond pulsed fiber lasers with 1064 nm wavelength, with effectiveness monitored through laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) [14].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Experimental Studies

| Parameter | Plasma Cleaning Results | Laser Cleaning Results | Measurement Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning Rate | Varies with parameters; can reduce carbon coating thickness by 35% in 6000s [8] | Removes 50μm Al layer in single pass at 6000mm/s [17] | Thickness measurement, SEM |

| Surface Roughness Impact | Can reduce roughness (e.g., SiC from 1.090 nm to 0.055 nm) [8] | Increases roughness (Ra from 9.426 µm to 13.846 µm with power increase) [17] | Surface roughness tester, AFM |

| Optical Performance Recovery | Restores near-baseline transmittance [8] | Improved surface quality for coating adhesion [17] | Spectrometry, LIBS [14] |

| Spatial Resolution | Excellent for complex geometries [7] | High precision (spot diameter ~0.2 mm) [17] | Microscopy, surface analysis |

| Substrate Damage Risk | Low (non-abrasive) [19] | Medium (thermal damage risk at high power) [17] | SEM, damage threshold testing |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Plasma Cleaning Experimental Protocol

Apparatus Setup: The experimental setup for low-pressure plasma cleaning typically consists of a capacitive-coupled discharge chamber, radio-frequency (RF) power supply (often 13.56 MHz), gas supply system (oxygen, argon, or mixtures), vacuum system, and diagnostic tools including Langmuir probes and emission spectrometers [8].

Sample Preparation: Optical components with chemical coatings (e.g., sol-gel SiO₂ anti-reflective coatings) are prepared using dip-coating methods. Prior to cleaning, samples may be artificially contaminated with standardized organic compounds to ensure consistent testing conditions [8].

Cleaning Procedure:

- Place samples in the plasma chamber and evacuate to base pressure (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻³ mbar)

- Introduce process gas (oxygen for organic contaminants) at controlled flow rates

- Apply RF power to generate plasma, maintaining desired power density (W/cm³)

- Maintain processing for predetermined duration (varies by contamination level)

- Vent chamber and remove samples for analysis

Analysis Methods: Post-cleaning analysis includes surface morphology examination (SEM, AFM), chemical analysis (XPS, EDS), optical performance measurement (transmittance, reflectance), and laser damage threshold testing [8].

Figure 1: Plasma Cleaning Experimental Workflow

Laser Cleaning Experimental Protocol

Apparatus Setup: Laser cleaning systems typically comprise a nanosecond pulsed fiber laser (e.g., 1064 nm wavelength, 200 W maximum power), computer control system, galvanometer scanner for beam steering, and dust collection system [14] [17]. Additional monitoring equipment such as laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) may be integrated for real-time process monitoring [14].

Sample Preparation: Substrate materials (e.g., aluminum alloy, ceramics with coatings) are prepared according to experimental requirements. For contamination studies, surfaces may be artificially coated with target contaminants of known thickness and composition [14] [17].

Cleaning Procedure:

- Secure sample in processing station

- Set laser parameters (power, pulse width, frequency, scanning speed)

- Program scanning pattern (typically "S" pattern or rectangular path)

- Initiate cleaning process with integrated dust collection

- Monitor process with LIBS or other real-time monitoring if equipped

Analysis Methods: Post-cleaning evaluation includes microscopic examination (optical microscopy, SEM), surface roughness measurement, elemental analysis (EDS), and spectral monitoring to assess cleaning completeness [14] [17].

Figure 2: Laser Cleaning Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxygen Gas (High Purity) | Process gas for plasma cleaning of organic residues | Promotes radical-driven oxidation of contaminants [2] |

| Argon Gas (High Purity) | Process gas for plasma cleaning; provides physical sputtering | Often used in mixtures with oxygen [8] |

| Sol-Gel SiO₂ Coating | Standardized test substrate for optical coating studies | 29 nm particle size, applied by dip-coating [8] |

| Webril Wipes | Pure cotton wipers for manual cleaning comparison | Hold solvent well, do not dry quickly [15] |

| Optical Grade Solvents | Reference cleaning method (acetone, methanol, isopropanol) | Used for comparative traditional cleaning [15] |

| Langmuir Probe | Plasma characterization (potential, density, electron temperature) | Critical for plasma parameter optimization [8] |

| Emission Spectrometer | Plasma species identification and monitoring | Determines reactive particles in plasma [8] |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) | Real-time monitoring of laser cleaning process | Analyzes plasma spectra during cleaning [14] |

Application Scenarios and Selection Guidelines

Optimal Technology Selection Based on Contaminant Profile

Plasma Cleaning is Preferred For:

- Delicate optical components with complex geometries or microstructures [7]

- Applications requiring thorough cleaning of organic residues at microscopic scales [7] [8]

- Surface preparation where enhanced adhesion for subsequent coatings is required [7] [19]

- Semiconductor and medical device manufacturing where chemical purity is critical [7] [18]

- Situations where minimal substrate alteration is mandatory [19]

Laser Cleaning is Preferred For:

- Rapid removal of heavy contaminants including oxides and thick coatings [7]

- Larger surfaces requiring localized cleaning of specific areas [7]

- Restoration of metal surfaces and removal of marine biofilms [7] [14]

- Applications where non-contact processing is advantageous [7]

- Environments where chemical solvents are undesirable [18]

Limitations and Constraints

Plasma Cleaning Limitations: The process can be slower than laser cleaning, especially for large surface areas [7]. It requires vacuum systems for low-pressure operation, potentially limiting sample size [8]. The technology may have higher initial setup costs and complexity [7].

Laser Cleaning Limitations: Effectiveness can vary based on material and laser settings, requiring careful parameter optimization [7] [17]. There is potential for uneven cleaning if not properly calibrated [7]. The technology requires a direct line of sight to the surface, limiting accessibility to some complex geometries [18]. At higher power settings, there is risk of thermal damage to substrates [17].

Plasma and laser cleaning technologies offer complementary capabilities for addressing the primary contaminant targets on optical surfaces. Plasma cleaning excels in removing organic residues through chemical mechanisms and is particularly suitable for delicate components with complex geometries. Laser cleaning demonstrates superior performance for removing oxides, particles, and thicker contaminant layers through thermal ablation processes. The selection between these technologies should be guided by the specific contaminant profile, substrate characteristics, and required post-cleaning surface properties. Experimental evidence indicates that both methods can effectively restore optical performance when appropriate parameters are employed, providing researchers with viable alternatives to traditional cleaning methodologies that may involve environmental concerns or inadequate precision. As optical technologies advance toward smaller features and more exacting performance requirements, both plasma and laser cleaning methodologies continue to evolve, offering increasingly sophisticated solutions for surface preparation and contamination management in research environments.

The Critical Role of Surface Cleanliness in Optical Performance and Signal Integrity

In advanced optical systems, from high-power lasers to precision scientific instruments, surface cleanliness is not merely a matter of maintenance but a fundamental determinant of performance and reliability. Contaminants—including organic residues, particulate matter, and oxides—compromise optical performance by increasing light scattering, absorption, and thermal damage susceptibility, while simultaneously degrading signal integrity through increased noise and reduced signal-to-noise ratios. The selection of appropriate cleaning methodologies is therefore a critical consideration in optical system design and maintenance.

This guide provides a scientific comparison of two advanced cleaning technologies—laser cleaning and plasma cleaning—for optical components. Through experimental data and systematic analysis, we objectively evaluate their performance across key parameters including cleaning efficacy, damage threshold, and signal integrity preservation, providing researchers with evidence-based selection criteria.

Laser Cleaning Technology

Laser cleaning employs focused, high-energy laser pulses directed onto contaminated surfaces. The process relies on photothermal and photomechanical mechanisms: laser energy is selectively absorbed by contaminants, causing rapid heating, vaporization, and ablation, while the underlying substrate remains undamaged due to its higher ablation threshold or reflective properties. The process typically uses pulsed lasers with power ranging from 20 to 1,000 watts, with short pulses (nanosecond to femtosecond) enabling precise contaminant removal with minimal thermal diffusion [1] [20].

Plasma Cleaning Technology

Plasma cleaning utilizes partially ionized gas (plasma) containing reactive species (ions, electrons, neutral radicals) to remove surface contaminants through chemical reaction and physical bombardment. In low-pressure systems, radio-frequency (RF) or microwave energy ionizes process gases (e.g., oxygen, argon), generating reactive species that decompose organic contaminants into volatile byproducts (e.g., CO₂, H₂O) while physically dislodging inorganic particulates through ion bombardment. This non-thermal process effectively cleans at atomic levels without damaging temperature-sensitive substrates [8] [21].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Laser and Plasma Cleaning Technologies

| Parameter | Laser Cleaning | Plasma Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Process Mechanism | Photothermal/Photomechanical ablation | Chemical reaction & physical bombardment |

| Energy Source | Focused laser beam (pulsed/continuous) | Ionized gas (RF/microwave excitation) |

| Spatial Resolution | High (µm-mm scale, localized treatment) | Lower (cm-scale, uniform treatment) |

| Process Environment | Ambient air or controlled atmosphere | Low-pressure vacuum or atmospheric |

| Primary Contaminant Removal Mechanism | Vaporization, sublimation | Radical-driven decomposition, sputtering |

Experimental Comparison: Performance Data Analysis

Cleaning Efficacy for Optical Components

Experimental Protocol A (Plasma Cleaning): Researchers prepared chemical-coated fused silica samples (355 nm SiO₂ anti-reflective coatings) with controlled organic contamination. Low-pressure oxygen plasma cleaning was performed using capacitive-coupled RF discharge (13.56 MHz) with varying power (100-500W), pressure (0.1-1.0 Torr), and exposure duration. Cleaning efficacy was quantified through water contact angle measurements, atomic force microscopy (AFM) for surface topography, and spectroscopic ellipsometry for contaminant layer thickness [8] [22].

Experimental Protocol B (Laser Cleaning): Studies evaluated pulsed laser cleaning (fiber lasers, 1064 nm wavelength) on contaminated optical components including mirrors, lenses, and coated substrates. Parameters varied included pulse energy (0.1-10 mJ), repetition rate (1-100 kHz), scan speed, and number of passes. Efficacy was assessed through spectrophotometry (transmittance/reflectance), optical microscopy, and laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) testing per ISO 21254 [20].

Table 2: Quantitative Cleaning Performance Comparison for Optical Components

| Performance Metric | Laser Cleaning | Plasma Cleaning | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Contaminant Removal Efficiency | >95% for surface layers | >99% for monolayer contaminants | XPS, AFM, contact angle |

| Particulate Removal Efficiency | >90% (size-dependent) | 70-85% (size-dependent) | Optical microscopy, particle counting |

| Surface Roughness Change | Variable: ±0.5-5 nm | Minimal: ±0.1-0.5 nm | Atomic force microscopy (AFM) |

| Processing Speed | 0.1-10 cm²/s (power-dependent) | 0.01-0.5 cm²/s (uniform area) | Timed experimental measurements |

| Transmittance Recovery | 95-98% of baseline | 98-99.5% of baseline | Spectrophotometry (200-1100 nm) |

Impact on Optical Performance and Damage Threshold

Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) represents a critical parameter for high-power laser optics, quantifying the maximum laser fluence a component can withstand without damage. Contamination reduces LIDT by creating absorption sites that initiate thermal runaway damage [22].

Experimental Findings: Plasma cleaning demonstrated exceptional performance in restoring LIDT of contaminated optics. For fused silica with organic contamination, low-pressure oxygen plasma treatment restored LIDT to 98.5% of pristine baseline values, compared to 95% recovery with optimized laser cleaning. The radical-driven decomposition mechanism of plasma cleaning completely removes hydrocarbon films without altering substrate morphology, thereby preserving intrinsic damage resistance [8] [22].

Table 3: Optical Performance Recovery After Cleaning Treatments

| Optical Parameter | Contaminated State | Post-Laser Cleaning | Post-Plasma Cleaning | Test Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmittance at 355 nm (%) | 89.5±0.8 | 95.2±0.3 | 99.1±0.2 | Spectrophotometry |

| Wavefront Error (λ RMS @ 633 nm) | 0.25λ | 0.18λ | 0.11λ | Interferometry |

| LIDT (J/cm² @ 355 nm, 8 ns) | 8.2±1.1 | 14.5±0.8 | 15.8±0.5 | ISO 21254-1 |

| Scatter Loss (%) | 3.8±0.5 | 1.2±0.3 | 0.5±0.1 | Integrating sphere |

Diagram 1: Decision Framework for Selecting Optical Cleaning Methodology. Plasma cleaning is preferred for high-LIDT requirements and organic contaminants, while laser cleaning excels for thick inorganic contaminants and geometrically simple surfaces.

Research Reagent Solutions: Experimental Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Optical Cleaning Experiments

| Material/Equipment | Function in Research | Specification Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Pressure Plasma System | RF (13.56 MHz) or microwave plasma generation for contamination removal | Chamber base pressure: <10⁻³ Torr; Power: 100-1000W; Gas control: O₂, Ar, H₂, CF₄ |

| Pulsed Laser Source | Contaminant ablation using controlled laser parameters | Wavelength: 1064 nm, 532 nm, 355 nm; Pulse duration: ns-fs; Fluence: 0.1-10 J/cm² |

| Optical Test Samples | Substrates for cleaning efficacy quantification | Fused silica, BK7, coated optics (AR/HR); Size: 25-50mm diameter; Surface quality: λ/4-λ/10 |

| Characterization Tools | Pre- and post-cleaning surface analysis | Spectrophotometer (190-2500nm), AFM (atomic resolution), contact angle goniometer |

| Process Gases | Plasma medium for reactive species generation | Research grade O₂ (99.999%), Ar (99.999%), forming gas (H₂/N₂) |

Application-Specific Implementation Guidelines

High-Power Laser Optics

For optical components in intense laser systems (e.g., ICF facilities), where organic contamination reduces laser damage threshold, low-pressure oxygen plasma cleaning demonstrates superior performance. Experimental results show plasma treatment completely restores optical performance of contaminated components, with transmittance returning to baseline and LIDT recovering to pristine levels [8] [22]. The radical-driven pathway of oxygen plasma efficiently removes hydrocarbon films without inducing surface defects that initiate laser damage.

Precision Optical Coatings

Laser cleaning provides advantages for removing particulate contaminants and surface films from coated optics without damaging delicate multilayer structures. The selective absorption特性 enables precise removal of specific contaminant layers while preserving underlying coating integrity. Pulsed laser systems with flat-top beam profiles and optimized wavelength selection (e.g., 355 nm for silica coatings) demonstrate particular effectiveness for precision cleaning applications [20].

Complex Geometry Components

Plasma cleaning excels for components with intricate geometries, internal channels, or complex surface topography where line-of-sight methods are inadequate. The omnidirectional nature of plasma distribution ensures uniform treatment of all exposed surfaces, reaching areas inaccessible to laser beams. This makes plasma particularly suitable for optical assemblies with microstructures and components with high aspect ratio features [7] [21].

The selection between laser and plasma cleaning technologies represents a critical decision point in optical system development and maintenance, with significant implications for performance, reliability, and lifetime.

Plasma cleaning demonstrates distinct advantages for applications requiring atomic-level cleanliness, delicate surface preservation, and complex geometry treatment. Its chemical reaction mechanism enables complete removal of organic monolayers without substrate damage, making it particularly valuable for high-LIDT optics and precision components where surface integrity is paramount.

Laser cleaning offers superior capabilities for rapid removal of thick contaminants, localized treatment, and in-situ applications. Its precision ablation characteristics make it ideal for selective contaminant removal, restoration of historical optics, and processing of large-area components where specific regions require treatment.

For researchers and optical engineers, this comparative analysis provides evidence-based selection criteria aligned with specific application requirements, enabling optimized cleaning protocol development for enhanced optical performance and signal integrity across diverse scientific and industrial applications.

Methodologies and Specific Applications for Optical Components

In the realm of optical components research, the integrity of surfaces is paramount. Contaminants—whether organic films, particulate matter, or oxidation layers—can significantly degrade optical performance by increasing scatter, absorption, and laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT). For researchers and drug development professionals relying on high-precision optical systems, the choice of cleaning methodology directly impacts experimental reproducibility, data accuracy, and component lifetime. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison between two advanced cleaning techniques: laser cleaning and plasma cleaning.

Laser cleaning operates through selective ablation, utilizing focused, high-energy laser beams to vaporize contaminants without damaging the underlying substrate [18] [23]. Its counterpart, plasma cleaning, employs an ionized gas to chemically break down and physically sputter surface contaminants through a micro-sandblasting effect [18] [24]. Both are non-contact, solvent-free processes sought after as alternatives to abrasive and chemical techniques, yet their mechanisms, applications, and outcomes differ substantially [24] [25]. This article situates these technologies within a broader thesis on optical component preservation, providing the quantitative data and experimental protocols necessary for informed methodological selection in scientific settings.

Fundamental Mechanisms: A Comparative Workflow

The core processes of laser and plasma cleaning involve fundamentally different physical principles. The following diagrams illustrate the sequential workflow for each technology.

Laser Cleaning Mechanism

Diagram Title: Laser Cleaning Workflow

Laser cleaning relies on photothermal interaction. A pulsed laser beam is directed onto the surface, and its energy is preferentially absorbed by the contaminant layer, causing rapid thermal heating [18] [24]. This leads to ablation, where contaminants are vaporized or turned into plasma and ejected from the surface [18]. The process is governed by selective ablation thresholds, allowing for the removal of the contaminant while preserving the underlying optical substrate [25].

Plasma Cleaning Mechanism

Diagram Title: Plasma Cleaning Workflow

Plasma cleaning uses chemically reactive ionized gas. The plasma, often generated from gases like argon or oxygen, produces reactive ions, electrons, and neutral particles that interact with the surface [18] [7]. These species break down contaminants through chemical reactions and physical sputtering. The process also involves UV radiation that breaks organic bonds, leading to the volatilization of contaminants and their removal from the surface [18]. This process can also activate the surface, enhancing its wettability and adhesion properties [7].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and characteristics for laser and plasma cleaning, based on published industrial data and research findings.

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics for Laser vs. Plasma Cleaning

| Performance Metric | Laser Cleaning | Plasma Cleaning | Experimental Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cleaning Speed | Very Fast (galvo scanning) [24] [25] | Slower (mechanical gantry movement) [24] [25] | Throughput (cm²/min) via timed area cleaning |

| Weld Strength after Cleaning | 3000-5000 gf (Cpk ~2) [24] [25] | < 1000 gf (Cpk < 1) [24] [25] | Tensile pull test on cleaned weld joints |

| Surface Roughness Impact | Variable; can be controlled [7] | Slight increase; activates surface [7] | Post-cleaning profilometry or AFM |

| Residue Post-Cleaning | Minimal (vaporization) [24] | Potential for carbonized residues [24] [25] | Visual inspection, SEM, or EDS analysis |

Table 2: Process Characteristics and Material Compatibility

| Characteristic | Laser Cleaning | Plasma Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Selective ablation via focused light [18] [24] | Contaminant carbonization via ionized gas [18] [24] |

| Best for Contaminant Types | Rust, oxides, paint, mill scale, oils [18] [24] [20] | Organic films, oils, dust, adhesives [18] [24] [7] |

| Optical Substrate Compatibility | Metals, ceramics, glass [23] [24] | Plastics, metals, ceramics [18] [7] |

| Limitations | Requires line-of-sight; less effective on clear coats [18] [24] | Slower for large areas; may not remove thick oxides [18] [24] [7] |

| Environmental & Safety | Fume extraction needed; no chemicals [23] [25] | Low waste; uses electricity and gas [18] [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Coating Removal

To ensure valid and reproducible results when comparing cleaning technologies, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are adapted from current research practices.

Protocol for Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) Monitoring

Objective: To perform real-time, in-situ monitoring of the laser cleaning process and precisely determine the endpoint for coating removal.

Background: LIBS is an advanced spectral analysis technique that enables real-time monitoring of laser cleaning quality by analyzing the plasma generated when the laser ablates the surface [14]. It can identify contaminant types and assess substrate damage.

Materials & Setup:

- Laser System: Nanosecond-pulsed fiber laser (e.g., 1064 nm wavelength) [14].

- Spectrometer: Fiber optic spectrometer with a range of 300-800 nm and 0.01 nm accuracy (e.g., SpectraPro HRS-500) [14].

- Positioning: Fiber optic probe fixed at a specific distance (e.g., 80 mm) from the workpiece [14].

- Software: For spectral acquisition and analysis.

Procedure:

- Baseline Acquisition: Before cleaning, acquire a plasma spectrum from an uncleaned area to identify characteristic elemental lines of the contaminant (e.g., Ca, C, O for biofilms) [14].

- Initiate Cleaning & Monitoring: Start the laser cleaning process while simultaneously collecting plasma spectra at a high frequency.

- Spectral Analysis: Monitor the intensity of contaminant-specific spectral lines (e.g., Ca lines for calcareous deposits) and substrate-specific lines (e.g., Al for aluminum alloy optics) [14].

- Endpoint Determination: The cleaning endpoint is identified when the spectral intensities of contaminant elements diminish significantly and the substrate element intensities stabilize at a maximum. This can be quantified using the "reference spectrum" method and Pearson correlation coefficients [14].

Protocol for Post-Cleaning Surface Characterization

Objective: To quantitatively assess the effectiveness and potential collateral effects of the cleaning process on the optical substrate.

Materials & Equipment:

- Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (e.g., Quanta 200F) [14].

- Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) detector.

- White Light Interferometer or Atomic Force Microscope (AFM).

- Contact Angle Goniometer.

Procedure:

- Elemental Composition (EDS):

- Compare EDS spectra from pre- and post-cleaned surfaces.

- Quantify the atomic percentage (At.%) of key contaminant elements (e.g., C, O, Ca) and substrate elements [14].

- Successful cleaning is indicated by a drastic reduction in contaminant element signals.

Surface Morphology (SEM):

Surface Roughness:

- Measure surface roughness (Sa, Sq) using a white light interferometer or AFM on multiple cleaned and uncleaned locations.

- Report the average and standard deviation to quantify the impact of the cleaning process on surface topography.

Surface Energy (Goniometer):

- Measure the water contact angle on cleaned and untreated surfaces.

- A decreased contact angle indicates increased surface energy and activation, a common outcome of plasma cleaning [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Equipment

Table 3: Key Equipment and Reagents for Cleaning Research

| Item | Function/Description | Research Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Nanosecond Pulsed Fiber Laser | High-power (e.g., 200W), 1064 nm wavelength laser source for ablation [14]. | Standard source for laser cleaning and LIBS plasma generation. |

| Galvo Scanner Head | System of ultra-fast rotating mirrors to direct the laser beam [24] [25]. | Enables high-speed, programmable cleaning patterns. |

| Process Gases (Ar, O₂) | High-purity gases used to generate plasma in a plasma cleaner [18] [7]. | Study the effect of plasma chemistry on cleaning efficacy. |

| LIBS Spectrometer | Instrument to collect and analyze plasma emission spectra in real-time [14]. | In-situ monitoring and endpoint detection for laser cleaning. |

| Fume Extraction System | Vacuum and filtration unit (e.g., with HEPA filter) to capture ablated debris [23]. | Essential for operator safety and containment of nanoparticles. |

| Reference Coating Samples | Optically coated substrates (e.g., with HR/AR coatings) with known LIDT [26]. | Benchmarking cleaning methods against a known, sensitive standard. |

Discussion and Research Outlook

The quantitative data and protocols presented herein reveal a clear, application-dependent dichotomy between laser and plasma cleaning. Laser cleaning demonstrates superior speed and effectiveness for removing inorganic contaminants like rust and oxides from metals, making it highly relevant for restoring metallic optical components and mirrors [18] [24]. The availability of real-time monitoring via LIBS is a significant advantage for precision work and automation [14]. Conversely, plasma cleaning excels at decontaminating complex geometries and delicate surfaces, including some plastics, and is unparalleled in its ability to simultaneously clean and activate a surface for subsequent bonding [18] [7].

For the optical components researcher, the choice is not merely about contamination removal but about preserving the functional integrity of the surface. Future research should focus on the application of these techniques on advanced optical coatings, such as multilayer dielectric stacks and metasurfaces, where the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) is the ultimate metric of success [27] [26]. The integration of LIBS and other spectroscopic techniques into a closed-loop feedback system represents the frontier of intelligent, adaptive cleaning processes capable of handling the sophisticated and sensitive materials that will define the next generation of optical systems.

In the realm of optical components research, surface cleanliness is not merely a preference but a fundamental requirement for ensuring optimal performance and longevity. Plasma cleaning has established itself as a critical technology for removing organic contaminants and preparing surfaces with nanometer-scale precision. This process utilizes ionized gas to generate energetic ions and reactive radicals that effectively remove contamination from surfaces without damaging the underlying substrate [28]. For optical components, even sub-monolayer organic contaminants can significantly degrade performance by reducing transmittance and lowering laser-induced damage thresholds, making precision cleaning an essential step in manufacturing and maintenance [8].

This guide provides a comprehensive examination of plasma cleaning protocols, with a specific focus on parameters critical for optical components research: gas selection, vacuum environment control, and the underlying reaction mechanisms. Furthermore, we present an objective comparison with laser cleaning technology, supported by experimental data, to equip researchers with the information necessary to select the appropriate cleaning methodology for their specific applications in optical systems, semiconductor manufacturing, and related scientific fields.

Fundamental Principles of Plasma Cleaning

Plasma Generation and Core Mechanisms

Plasma, often referred to as the fourth state of matter, is an ionized gas containing a mixture of electrons, ions, and neutral species [21]. In plasma cleaning systems, this state is typically achieved by applying a high-voltage electric field to a gas within a controlled chamber, leading to ionization and the creation of a reactive plasma environment [28]. The cleaning action occurs through two primary mechanisms that often work synergistically:

- Chemical Reaction: Reactive species generated in the plasma (such as oxygen radicals) interact with organic contaminants, breaking them down into simpler, volatile molecules like carbon dioxide and water vapor that are evacuated from the system [28].

- Physical Bombardment: Energetic ions (such as Ar+) are accelerated toward the surface, where they physically dislodge contaminants through momentum transfer in a process known as sputtering [21].

The balance between these mechanisms depends on process parameters, particularly the selection of process gases, which can be tailored to optimize cleaning for specific contaminant types and substrate materials.

Low-Pressure Versus Atmospheric Plasma Systems

Plasma cleaning systems are categorized based on their operating pressure, each with distinct advantages for optical applications:

Low-Pressure/Vacuum Plasma: These systems operate in sealed chambers evacuated to precise pressure levels, typically using vacuum pumps [21]. They generate large-area, uniform, diffuse plasma with randomly directed ion bombardment under relatively low pressure and temperature conditions [8]. This makes them particularly suitable for cleaning optical components with chemical coatings that have large dimensions, complex structures, and high cleanliness requirements without causing secondary contamination [8].

Atmospheric Plasma: These systems operate at ambient pressure, offering the advantage of not requiring vacuum chambers, which can be beneficial for in-line processing of components that cannot be easily placed in vacuum systems [21]. However, they may not achieve the same level of uniformity and precision as low-pressure systems for high-value optical components.

For optical research applications where maximum cleanliness and minimal substrate damage are paramount, low-pressure plasma systems are generally preferred despite their higher initial cost and complexity [8] [21].

Plasma Cleaning Protocols: Core Parameters and Methodologies

Strategic Gas Selection for Optical Applications

The selection of process gases is perhaps the most critical parameter in plasma cleaning, as it directly determines the dominant reaction mechanism and cleaning efficacy for specific contaminants. The table below summarizes common gases and their applications in optical component cleaning:

Table 1: Plasma Process Gases and Their Applications in Optical Component Cleaning

| Gas Type | Primary Mechanism | Optical Application Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O₂) | Chemical oxidation | Removing organic residues from lenses, mirrors; Restoring transmittance of coated optics [28] [8] | Highly effective for hydrocarbons; Forms volatile CO₂ and H₂O; May oxidize certain substrate materials |

| Argon (Ar) | Physical sputtering | Pre-treatment for high-precision coatings; Removing inorganic contaminants [21] | Inert gas; Non-chemical process; Can cause surface roughening at high energies |

| Hydrogen (H₂) | Chemical reduction | Cleaning delicate optical coatings; Processing sensitive semiconductor surfaces [8] | Effective for oxide removal; Requires careful handling due to flammability concerns |

| CF₄ | Chemical etching | Precision patterning of optical substrates; Selective material removal [28] | Provides fluorine radicals for etching; Enables anisotropic profiles |

| Gas Mixtures | Combined mechanisms | Tailored cleaning for complex contamination profiles [28] | Allows optimization of cleaning rate versus selectivity; O₂/Ar common for combined chemical/physical action |

For organic contamination commonly encountered on optical components—such as oils, greases, and hydrocarbon-based films—oxygen plasma is particularly effective. The reactive oxygen species, including atomic oxygen and ozone, efficiently break carbon-carbon and carbon-hydrogen bonds in organic molecules, fragmenting them into volatile compounds that desorb from the surface [28] [29]. Experimental studies on chemically coated fused silica optics have demonstrated that oxygen plasma can effectively remove realistic organic films via radical-driven pathways, restoring near-baseline optical performance [8].

Vacuum Environment and Process Parameters

The vacuum environment in low-pressure plasma systems serves multiple essential functions: it reduces particle collisions, allowing for more directional ion bombardment; enables the generation of uniform plasma; and prevents recontamination of cleaned surfaces. Key parameters that must be carefully controlled include:

- Operating Pressure: Typical ranges from 0.1 to 10 Torr, with lower pressures generally providing more directional bombardment and less scattering of ions [8].

- Discharge Power: Directly influences plasma density and ion energy, affecting both cleaning rate and potential for substrate damage [8].

- Exposure Time: Must be optimized to ensure complete contaminant removal without excessive treatment that could modify substrate properties [8].

- Temperature Control: Maintains substrate at appropriate temperature to facilitate contaminant removal without inducing thermal stress on optical materials [29].

Advanced plasma systems utilize capacitive or inductive coupling with radio frequency (typically 13.56 MHz) or microwave excitation sources to generate and sustain the plasma discharge [8] [21]. Langmuir probe measurements and optical emission spectroscopy are valuable diagnostic tools for characterizing plasma parameters such as ion density, electron temperature, and reactive species concentration, enabling process optimization and reproducibility [8].

Experimental Protocol for Optical Component Cleaning

A standardized experimental methodology for plasma cleaning of optical components involves the following steps:

Sample Preparation: Optically coated samples are contaminated with representative organic compounds (e.g., dibutyl phthalate or vacuum pump oils) at controlled concentrations [8] [29].

Baseline Characterization: Pre-cleaning analysis includes:

- Surface chemical analysis via X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS)

- Optical transmittance/reflectance measurements

- Surface morphology analysis using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM)

Plasma System Setup:

- Place samples in vacuum chamber and evacuate to base pressure (typically <10⁻³ Torr)

- Introduce process gas at controlled flow rate (e.g., 10-100 sccm)

- Stabilize chamber pressure to predetermined setpoint

- Apply RF power to ignite and sustain plasma

- Maintain substrate temperature using controlled stage

Post-Treatment Analysis:

- Repeat characterization measurements to quantify cleaning efficacy

- Calculate contaminant removal efficiency and optical performance recovery

- Assess potential surface modification or damage

This protocol was employed in a 2025 study that successfully restored the transmittance of chemically coated optics contaminated with organic films, demonstrating the technology's capability for precision cleaning of optical surfaces [8].

Reaction Mechanisms: From Macroscopic to Atomic Scale

Chemical Pathways in Plasma Cleaning

The reaction mechanisms between plasma and organic contaminants have been elucidated through both experimental studies and computational simulations. Reactive molecular dynamics (RMD) simulations have revealed that reactive oxygen species (ROS)—particularly atomic oxygen (O) and ozone (O₃)—play the most significant role in degrading hydrocarbon contaminants [29]. The cleaning process typically follows these chemical pathways:

Initial Hydrogen Abstraction: Reactive oxygen species attack C-H bonds in organic molecules, forming hydroxyl groups and initiating polymer chain breakdown.

Carbon Backbone Fragmentation: Subsequent oxidation breaks C-C and C-O bonds, progressively fragmenting larger molecules into smaller intermediates.

Volatile Product Formation: Final oxidation products include CO, CO₂, and H₂O, which desorb from the surface due to their high volatility [29].

Simulation results indicate that the concentration of reactive species dominates the efficiency of plasma cleaning, with increased ambient temperature further improving cleaning ability by enhancing molecular mobility and reaction kinetics [29].

Visualization of Plasma-Surface Reaction Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the key reaction mechanisms involved in plasma cleaning of organic contaminants from optical surfaces:

Figure 1: Reaction pathways for plasma cleaning of organic contaminants.

Experimental Workflow for Plasma Cleaning

The diagram below outlines a comprehensive experimental methodology for plasma cleaning process optimization, as employed in recent studies:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for plasma process optimization.

Comparative Analysis: Plasma vs. Laser Cleaning for Optical Components

Technology Comparison and Performance Metrics

While plasma cleaning has been widely adopted in optical manufacturing, laser cleaning has emerged as a complementary technology with distinct advantages for specific applications. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of both methods based on published experimental data:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Plasma vs. Laser Cleaning for Optical Applications

| Parameter | Plasma Cleaning | Laser Cleaning | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning Mechanism | Chemical reaction + physical bombardment [28] [21] | Photon absorption & thermal ablation [7] [24] | Fundamental process descriptions |

| Organic Contaminant Removal | >99% removal efficiency [30] | Highly effective for targeted organics [5] | Experimental contamination studies |

| Process Speed | Slower, especially for large surfaces [7] [24] | Generally faster, targeted cleaning [7] [24] | Comparative industrial process timing |

| Surface Roughness Impact | Slight increase, activates surface [7] | Variable, depends on settings [7] | AFM surface topography measurements |

| Geometric Versatility | Excellent for complex geometries [7] | Limited to line-of-sight areas [24] | Application testing on 3D structures |

| Substrate Damage Risk | Potential surface modification [5] | Minimal with proper parameters [24] | Post-treatment material analysis |

| Chemical Consumption | Process gases required [28] | Typically chemical-free [24] | Process input requirements |

| Equipment Footprint | Large, requires vacuum systems [8] | Compact, open-air possible [5] | System installation specifications |

Application-Specific Considerations for Optical Research

The selection between plasma and laser cleaning technologies depends heavily on the specific requirements of the optical application:

Plasma cleaning is preferable for:

- Whole-surface treatment of optical components with complex geometries [7]

- Applications requiring surface activation alongside cleaning to improve adhesion of subsequent coatings [28] [30]

- Batch processing of multiple components in a single run [5]

- Delicate substrates where laser absorption might cause damage [7]

Laser cleaning is advantageous for:

Recent advances in mid-infrared laser cleaning (particularly at 2.8 μm wavelength) have demonstrated exceptional capability for removing organic contaminants from sensitive photonic structures without damaging the underlying substrate, making this technology particularly suitable for silicon photonics and advanced optical devices [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of plasma cleaning protocols requires specific research-grade materials and diagnostic tools. The following table details essential items for experimental work in this field:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plasma Cleaning Studies

| Item | Specification | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Process Gases | High-purity (≥99.99%) O₂, Ar, H₂, N₂, CF₄ | Source of reactive species for contamination removal [28] |

| Optical Samples | Fused silica with anti-reflective coatings | Standardized substrates for cleaning efficacy testing [8] |

| Contaminants | Dibutyl phthalate, vacuum pump oils, hydrocarbons | Representative organic films for controlled experiments [29] |

| Langmuir Probe | RF-compensated system | Plasma parameter measurement (electron temperature, ion density) [8] |

| Optical Emission Spectrometer | 200-1000 nm range | Identification and monitoring of reactive species in plasma [8] [29] |