Linearity and Range in Pharmaceutical Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to HPLC and UV-Vis Method Comparison

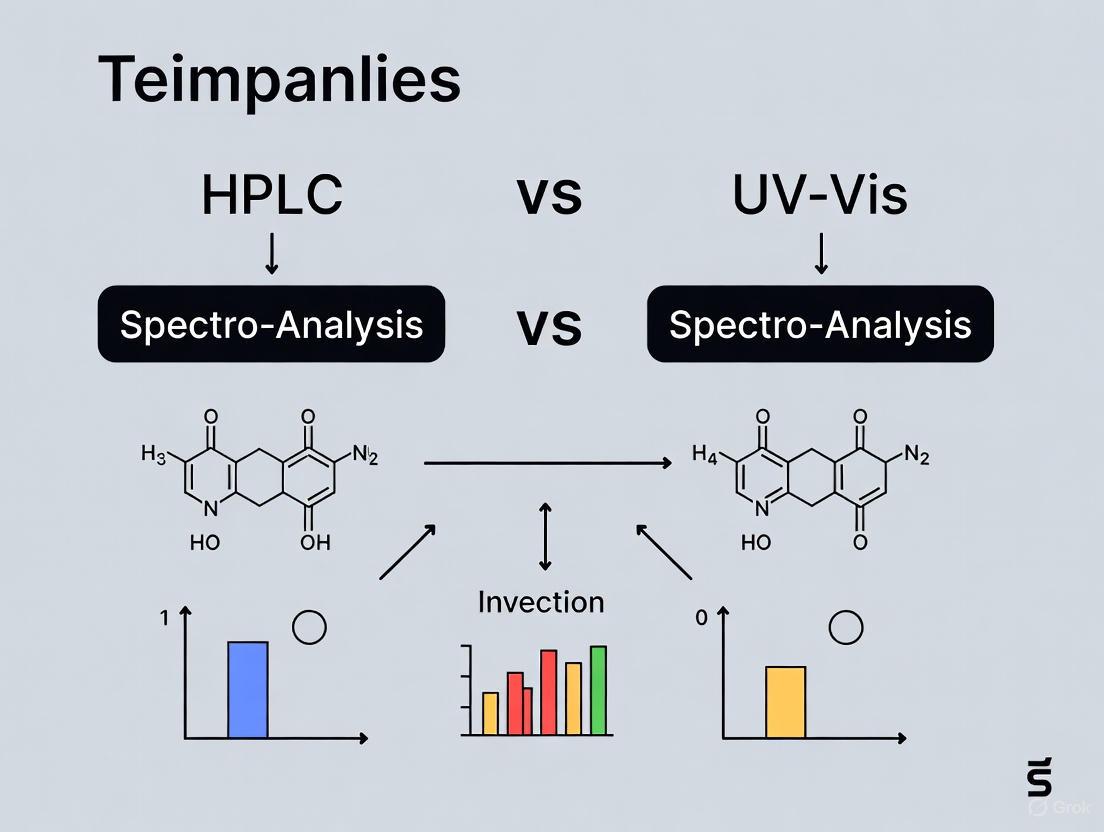

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of the linearity and range characteristics of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and UV-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy for pharmaceutical analysis.

Linearity and Range in Pharmaceutical Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide to HPLC and UV-Vis Method Comparison

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of the linearity and range characteristics of High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and UV-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy for pharmaceutical analysis. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles governing the quantitative response of each technique. The scope encompasses methodological applications, troubleshooting for non-linearity, and validation strategies as per ICH guidelines. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical case studies, this review serves as a critical resource for selecting and optimizing analytical methods to ensure accurate, reliable, and compliant quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients and impurities throughout the drug development lifecycle.

Core Principles: Deconstructing Linearity and Range in HPLC and UV-Vis Spectroscopy

In analytical chemistry, the validity and reliability of a method are paramount. Linearity and range are two critical validation parameters that ensure an analytical procedure can accurately and precisely quantify a substance over a defined concentration span. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these concepts is essential for developing robust HPLC and UV-Vis methods, which are foundational techniques in pharmaceutical analysis. This guide explores these key parameters and objectively compares how they are demonstrated in both HPLC and UV-Vis methodologies, providing a clear framework for analytical method validation.

Theoretical Foundations: Understanding Linearity and Range

What is Linearity?

Linearity refers to the ability of an analytical method to produce results that are directly, or linearly, proportional to the concentration of the analyte in a given sample [1] [2]. It demonstrates that the method's response (for example, the peak area in HPLC or absorbance in UV-Vis) increases predictably as the amount of analyte increases.

The relationship is typically evaluated using a calibration curve, which is a plot of the instrumental response against the analyte concentration [1]. The quality of the linear relationship is often expressed statistically by the correlation coefficient (R²) or the coefficient of determination, with a value of ≥ 0.995 or 0.997 commonly set as the acceptance criterion [1] [2].

What is Range?

The range of an analytical method is defined as the interval between the upper and lower concentration levels of an analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [1]. In essence, the range defines the "span of usable concentrations" where the method is proven to perform reliably [1]. It is directly derived from the linearity study and must encompass all concentrations where the analyte will be measured during routine analysis.

The Relationship and Distinction

While deeply interconnected, linearity and range address different questions:

- Linearity shows how well the method performs across concentrations, gauging the quality of the proportional relationship.

- Range defines where the method performs well, specifying the concentration span over which this linearity, plus accuracy and precision, are maintained [1].

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for establishing and evaluating these parameters:

A Comparative Case Study: Levofloxacin Analysis

A direct comparison of HPLC and UV-Vis methods for analyzing Levofloxacin in a complex drug-delivery system highlights practical performance differences [3]. The study aimed to measure the drug's release from a mesoporous silica microspheres/nano-hydroxyapatite (n-HA) composite scaffold, a context with significant potential for impurity interference.

Experimental Protocol Summary [3]:

- Analytes: Levofloxacin.

- Methods: HPLC with UV detection and UV-Vis spectrophotometry.

- Sample Preparation: A standard curve for Levofloxacin was established in simulated body fluid (SBF) across a concentration range of 0.05–300 µg/mL. For HPLC, an internal standard (Ciprofloxacin) was used, and samples were processed with liquid-liquid extraction before analysis.

- Instrumentation:

- HPLC: Shimadzu liquid chromatograph with a Sepax BR-C18 column. Mobile phase: 0.01 mol/L KH₂PO₄, methanol, and tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulphate (75:25:4). Flow rate: 1 mL/min. Detection: 290 nm.

- UV-Vis: UV-2600 spectrophotometer. Wavelength: 283.5 nm (determined from scanning).

- Linearity Assessment: Fourteen different concentration levels were analyzed to establish the calibration curve.

The quantitative results from this study are summarized in the table below:

Table 1: Comparison of HPLC and UV-Vis Performance for Levofloxacin Analysis

| Parameter | HPLC Method | UV-Vis Method |

|---|---|---|

| Regression Equation | y = 0.033x + 0.010 | y = 0.065x + 0.017 |

| Correlation Coefficient (R²) | 0.9991 | 0.9999 |

| Recovery at 5 µg/mL | 96.37 ± 0.50% | 96.00 ± 2.00% |

| Recovery at 25 µg/mL | 110.96 ± 0.23% | 99.50 ± 0.00% |

| Recovery at 50 µg/mL | 104.79 ± 0.06% | 98.67 ± 0.06% |

| Conclusion in Study | Preferred method for accurate measurement in complex scaffold system. | Less accurate for measuring drug concentration in biodegradable composites. |

The data shows that while both methods demonstrated excellent correlation coefficients (R² > 0.999), the UV-Vis method showed more consistent accuracy (recovery rates of 96-100%) across the three concentration levels compared to the HPLC method, which showed more variable recovery (96-111%) in this specific experimental context [3]. The authors concluded that for their complex system with potential impurities, HPLC was the more accurate and preferred technique [3].

Experimental Protocols for Determining Linearity and Range

The following workflow, consistent with ICH guidelines, details the general steps for establishing linearity and range.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Analytical Reference Standard | High-purity analyte used to prepare calibration standards for accurate curve generation. |

| Blank Matrix | The sample material without the analyte, used to assess specificity and matrix effects. |

| Mobile Phase Solvents (HPLC) | HPLC-grade solvents used to carry the sample through the chromatographic column. |

| Diluent | Appropriate solvent to dissolve and dilute the analyte and standards without interference. |

Step-by-Step Workflow

- Define the Concentration Range: Based on the method's application, bracket the expected sample concentrations. A typical range is 50% to 150% of the target or specification level [1] [2]. For impurity methods, the range may extend from the quantitation limit (QL) to 150% of the specification limit [1].

- Prepare Standard Solutions: Prepare a minimum of five to six concentration levels within the defined range [1] [2]. For instance, to validate an assay for an impurity specified at 0.20%, levels might include QL (e.g., 0.05%), 50% (0.10%), 100% (0.20%), and 150% (0.30%) of that limit [1].

- Analyze the Standards: Inject or analyze each concentration level, preferably in triplicate, using the finalized analytical method [2].

- Plot and Analyze Data: Plot the average response (e.g., peak area, absorbance) against the concentration for each level. Perform a linear regression analysis to calculate the slope, y-intercept, and correlation coefficient (R²).

- Evaluate Residuals: Visually inspect a plot of the residuals (the difference between the measured and predicted responses). A random scatter of residuals around zero indicates a good fit, while a pattern suggests non-linearity [2].

- Define the Validated Range: The range is the concentration interval over which the acceptable linearity (e.g., R² ≥ 0.995), as well as required precision and accuracy, are consistently achieved [1].

The decision-making process during this validation is summarized below:

HPLC vs. UV-Vis: A Method Comparison Guide

The fundamental difference in technique—separating components versus measuring bulk absorption—shapes how linearity and range are approached in HPLC and UV-Vis.

Table 3: HPLC vs. UV-Vis at a Glance

| Feature | HPLC | UV-Vis Spectrophotometry |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Separation followed by detection. | Direct measurement of light absorption. |

| Selectivity | High. Resolves analytes from impurities and matrix, reducing interference [3]. | Low. Measures total absorbance at a wavelength, which can include interfering substances [3]. |

| Impact on Linearity | A clean separation ensures the detector response is specific to the analyte, leading to more reliable linearity in complex matrices. | In complex samples, absorbance from other components can cause deviation from true linearity for the target analyte [3]. |

| Typical Range | Can be very broad, often over several orders of magnitude, due to the specificity of detection. | May be narrower in complex samples due to matrix effects and the Beer-Lambert law's limitations at high concentrations. |

| Best Suited For | Analysis of specific compounds in complex mixtures (e.g., drug potency, impurity profiling) [3] [4]. | Analysis of pure substances or simple mixtures, or when used as a simple, low-cost detector for HPLC [5] [6] [7]. |

Linearity and range are non-negotiable pillars of a reliable analytical method. While UV-Vis spectrophotometry offers simplicity and cost-effectiveness for well-defined applications, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography provides superior selectivity and is often the unequivocal choice for accurate analysis in complex matrices, as demonstrated in the Levofloxacin case study. The rigorous validation of these parameters, following established protocols and a critical evaluation of the data beyond just the R² value, provides the scientific evidence that an analytical method is fit for its intended purpose, thereby ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of pharmaceutical products.

The Beer-Lambert Law (also known as Beer's Law) establishes a fundamental relationship between the attenuation of light through a substance and the physical properties of that substance, forming the cornerstone of ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy and quantitative analysis [8]. This principle enables scientists to determine the concentration of solutes in solution by measuring how much light the solution absorbs at specific wavelengths. The law states that the absorbance of light by a solution is directly proportional to both the concentration of the absorbing substance and the path length the light takes through the solution [9].

In practical terms, when monochromatic light passes through a solution in a cuvette with an incident intensity (I₀) and emerges with a transmitted intensity (I), the transmittance (T) is defined as the ratio I/I₀, often expressed as a percentage [8]. More importantly for quantitative work, absorbance (A) has a logarithmic relationship to transmittance, defined as A = log₁₀(I₀/I) [8] [9]. This relationship means that an absorbance of 1 corresponds to 10% transmittance, while an absorbance of 2 corresponds to 1% transmittance [8]. The mathematical expression of the Beer-Lambert Law combines these relationships into the equation A = εlc, where ε is the molar absorptivity or molar absorption coefficient (a measure of how strongly a substance absorbs light at a specific wavelength), l is the path length of light through the solution (typically 1 cm for standard cuvettes), and c is the concentration of the solution [8] [9].

The linear relationship between absorbance and concentration expressed in the Beer-Lambert Law enables the creation of calibration curves, which are fundamental to quantitative analysis in pharmaceutical research, environmental testing, and material characterization [8]. This foundational principle allows researchers to determine unknown concentrations by measuring absorbance and comparing it to standards of known concentration.

Theoretical Framework and Instrumentation

Core Principles of Light Absorption

UV-Vis spectroscopy operates on the principle that molecules absorb light at specific wavelengths when the energy of incoming photons matches the energy required to promote electrons to higher energy states [10]. The amount of energy carried by light is inversely proportional to its wavelength, meaning shorter wavelengths of UV and visible light carry more energy than longer wavelengths [10]. Different bonding environments in molecules require different specific energy amounts for electronic transitions, which explains why substances absorb light at different characteristic wavelengths, creating unique "spectral fingerprints" [10].

The relationship between absorbance and transmittance is crucial for understanding why absorbance is preferred for quantitative analysis. As shown in Table 1, absorbance has a logarithmic relationship with transmittance, which creates a linear relationship with concentration as per the Beer-Lambert Law [8] [11]. In contrast, transmittance has an exponential relationship with concentration, making it unsuitable for direct quantitative measurements [11]. This fundamental mathematical principle explains why quantitative analysis is always performed using absorbance rather than percentage transmittance.

Table 1: Relationship Between Absorbance and Transmittance

| Absorbance | % Transmittance | Light Transmitted |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100% | 100% |

| 0.3 | 50% | 50% |

| 1 | 10% | 10% |

| 2 | 1% | 1% |

| 3 | 0.1% | 0.1% |

UV-Vis Spectrophotometer Components

A UV-Vis spectrophotometer consists of several key components that work together to measure light absorption [10]:

- Light Source: Typically a xenon lamp for full UV-Vis range, or dual lamps (deuterium for UV and tungsten/halogen for visible light)

- Wavelength Selector: Monochromators with diffraction gratings (typically 1200-2000 grooves/mm) or filters to select specific wavelengths

- Sample Holder: Cuvettes typically with 1 cm path length, made of quartz for UV studies (as glass and plastic absorb UV light)

- Detector: Photomultiplier tubes (PMT), photodiodes, or charge-coupled devices (CCDs) to convert light intensity into electrical signals

The instrumental setup follows either a cuvette-based system for standard liquid samples or cuvette-free systems for specialized applications such as DNA/RNA analysis with very small sample volumes [10]. Proper instrument calibration using blank reference samples is essential for obtaining accurate absorbance measurements, as the reference signal automatically corrects for solvent effects and instrumental characteristics [10].

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of a UV-Vis spectrophotometer components and light path

Experimental Protocols and Method Validation

Standard UV-Vis Methodology

The development and validation of a UV-Vis spectroscopic method for pharmaceutical analysis follows established protocols to ensure reliability, accuracy, and precision. A typical methodology for drug quantification, such as for terbinafine hydrochloride, involves these key steps [5]:

Standard Solution Preparation: Precisely weigh 10 mg of reference standard and transfer to a 100 mL volumetric flask. Add approximately 20 mL of distilled water, shake manually for 10 minutes, then dilute to volume with distilled water to obtain a stock solution of 100 μg/mL.

Wavelength Selection: Transfer 0.5 mL of stock solution to a 10 mL volumetric flask and dilute to mark with distilled water (5 μg/mL final concentration). Scan the resulting solution across 200-400 nm using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer to identify the maximum absorption wavelength (λmax). For terbinafine hydrochloride, this was found at 283 nm [5].

Calibration Curve Construction: Prepare a series of standard solutions covering the expected concentration range (e.g., 5-30 μg/mL for terbinafine hydrochloride). Measure absorbance at λmax and plot concentration versus absorbance. Perform regression analysis to establish the linear relationship [5].

Sample Analysis: Prepare test samples from pharmaceutical formulations at appropriate dilutions and measure absorbance at the established λmax. Calculate concentration using the calibration curve equation.

Method Validation Parameters

According to International Conference on Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines, UV-Vis methods must be validated for specific analytical performance characteristics [5] [12]:

- Linearity: Demonstrated through correlation coefficient (r² > 0.999) across the working range [5] [12]

- Precision: Evaluated as intra-day and inter-day variations, with %RSD < 2% [5]

- Accuracy: Assessed through recovery studies at 80%, 100%, and 120% levels, with recoveries of 98-102% [5]

- Specificity: Ability to measure analyte accurately in presence of excipients or impurities [12]

- Detection and Quantitation Limits: LOD = 3.3×N/B and LOQ = 10×N/B, where N is standard deviation of blank and B is slope of calibration curve [5]

Table 2: Typical Validation Parameters for UV-Vis Methods of Various Pharmaceuticals

| Drug Compound | Linear Range (μg/mL) | λmax (nm) | Correlation Coefficient (r²) | Recovery (%) | Precision (%RSD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Terbinafine HCl [5] | 5-30 | 283 | 0.999 | 98.54-99.98 | <2 |

| Repaglinide [12] | 5-30 | 241 | >0.999 | 99.63-100.45 | <1.5 |

| Atezolizumab [13] | 0.10-1.50 mg/mL | - | 0.9995 | - | - |

| Oxytetracycline [14] | 5-25 | 268 | - | - | - |

Comparative Analysis: UV-Vis vs. HPLC in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Performance Comparison Studies

Direct comparison studies between UV-Vis spectroscopy and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) provide valuable insights for method selection in pharmaceutical analysis. A comprehensive study on levofloxacin quantification demonstrated distinct performance characteristics between these techniques [3]:

The HPLC method exhibited excellent linearity (y = 0.033x + 0.010, R² = 0.9991) across a wide concentration range (0.05-300 μg/mL), while the UV-Vis method also showed strong linearity (y = 0.065x + 0.017, R² = 0.9999) within a more limited range [3]. Recovery studies revealed that HPLC provided more accurate results for levofloxacin loaded on complex composite scaffolds, with recovery rates of 96.37±0.50%, 110.96±0.23%, and 104.79±0.06% for low, medium, and high concentrations, respectively [3]. In comparison, UV-Vis showed recovery rates of 96.00±2.00%, 99.50±0.00%, and 98.67±0.06% for the same concentration levels [3].

Similarly, a study on repaglinide analysis found that while both methods demonstrated suitable linearity (r² > 0.999) and accuracy, HPLC offered a wider linear range (5-50 μg/mL) compared to UV-Vis (5-30 μg/mL) [12]. The HPLC method also showed superior precision with lower %RSD values, making it more suitable for complex formulations or when higher specificity is required [12].

Analytical Strengths and Limitations

Each technique offers distinct advantages depending on the analytical requirements:

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Strengths:

- Simplicity of operation and minimal training requirements [5]

- Rapid analysis time and high sample throughput [5] [12]

- Lower instrumentation and maintenance costs [5] [12]

- Excellent for routine quality control of raw materials and simple formulations [5]

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Limitations:

- Susceptibility to interference from excipients, impurities, or overlapping absorptions [3]

- Generally narrower linear range compared to HPLC [12]

- Lower specificity for complex mixtures without separation [3]

- Limited application for compounds without suitable chromophores [15]

HPLC Strengths:

- Superior specificity and ability to separate complex mixtures [3] [12]

- Wider linear dynamic range for quantification [3] [12]

- Better accuracy for analysis in complex matrices [3]

- Compatibility with various detection methods (UV, RI, MS) [15]

HPLC Limitations:

- Higher instrumentation and operational costs [12]

- Longer analysis time and more complex method development [12]

- Requires greater technical expertise for operation and maintenance [12]

- Higher consumption of solvents and reagents [12]

Table 3: Direct Comparison of UV-Vis and HPLC for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Parameter | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | HPLC with UV Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Minutes per sample | 10-30 minutes per run |

| Linearity Range | Limited (e.g., 5-30 μg/mL) [12] | Wider (e.g., 0.05-300 μg/mL) [3] |

| Specificity | Low to Moderate (depends on matrix) | High (with separation) |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (LOD ~μg/mL) [5] | Higher (LOD ~ng/mL) |

| Precision (%RSD) | Typically <2% [5] | Typically <1.5% [12] |

| Equipment Cost | Low to Moderate | High |

| Skill Requirement | Basic training required | Advanced training needed |

| Sample Throughput | High | Moderate |

| Ideal Application | Raw material testing, simple formulations | Complex matrices, stability studies, bioanalysis |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis and Quality Control

Pharmaceutical Quality Control Applications

UV-Vis spectroscopy serves as a workhorse technique in pharmaceutical quality control due to its simplicity, reliability, and cost-effectiveness. The technique has been successfully applied to various drug compounds, including:

- Terbinafine Hydrochloride: Method validation for bulk drug and pharmaceutical formulations demonstrated excellent linearity (5-30 μg/mL), precision (%RSD < 2), and recovery (98.54-99.98%) [5]

- Repaglinide: Quantitative analysis in tablet dosage forms with good accuracy (99.63-100.45% recovery) and precision (%RSD < 1.5) [12]

- Atezolizumab: Determination in pharmaceutical products with wide linear range (0.10-1.50 mg/mL) and high correlation (r² = 0.9995) [13]

- Oxytetracycline: Development and validation of method for veterinary injections, with 28 of 47 samples complying with specifications [14]

For these applications, UV-Vis spectroscopy provides sufficient accuracy and precision while offering advantages in speed and cost-efficiency compared to chromatographic methods. The technique is particularly valuable for routine analysis in quality control laboratories with high sample throughput requirements.

Research and Development Applications

In pharmaceutical research and development, UV-Vis spectroscopy finds application in:

- Preformulation studies to determine solubility profiles and stability constants

- Drug release testing from delivery systems, though with limitations in complex matrices [3]

- Compatibility studies between active ingredients and excipients

- Raw material identification and qualification

The Beer-Lambert Law enables researchers to quickly screen multiple formulations during early development stages, with HPLC confirmation for final candidate selection. This complementary approach optimizes resource allocation while maintaining data quality throughout the development process.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of UV-Vis spectroscopic methods requires specific reagents and materials carefully selected for each application. The following essential research reagents form the foundation of reliable pharmaceutical analysis:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Analysis | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Pharmacopeial grade (when available) or high purity (>95%) | Primary calibration and method validation | Terbinafine HCl RS [5], Oxytetracycline RS [14] |

| Solvents | HPLC or analytical grade | Sample dissolution, dilution, and blank preparation | Methanol [12], distilled water [5], 0.01N HCl [14] |

| Volumetric Flasks | Class A glassware | Precise preparation of standard and sample solutions | 10, 50, 100, 200 mL capacities [5] [14] |

| Quartz Cuvettes | 1 cm path length, high transmission | Sample holder for UV range measurements | Required for wavelengths <350 nm [10] |

| pH Adjusters | Analytical grade acids/bases | Mobile phase modification or sample stabilization | Orthophosphoric acid [12], hydrochloric acid [14] |

| Filters | 0.22 μm or 0.45 μm membrane | Sample clarification before analysis | Removal of particulate matter [14] |

Figure 2: Decision tree for selection between UV-Vis and HPLC methods based on analytical requirements

The Beer-Lambert Law remains the fundamental principle underlying UV-Vis spectroscopy and its application in pharmaceutical quantitative analysis. While HPLC generally offers superior specificity, wider linear range, and better performance in complex matrices, UV-Vis spectroscopy maintains significant advantages in simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and analysis speed [3] [12]. The choice between these techniques should be guided by specific analytical needs, with UV-Vis being ideal for routine quality control of raw materials and simple formulations, and HPLC being preferred for complex matrices, method development, and situations requiring high specificity [3] [5] [12].

For comprehensive quality control systems, both techniques can play complementary roles, with UV-Vis serving as a rapid screening tool and HPLC providing confirmatory analysis when needed. The continued development and validation of UV-Vis methods according to ICH guidelines [5] [12] ensures this accessible technique remains relevant in modern pharmaceutical analysis, particularly in resource-limited settings where cost considerations are paramount. As pharmaceutical formulations grow increasingly complex, understanding the capabilities and limitations of both UV-Vis and HPLC becomes essential for selecting the appropriate analytical approach based on specific requirements for sensitivity, specificity, throughput, and cost.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is a powerful analytical technique that separates, identifies, and quantifies components in a mixture. The core principle involves distributing the analyte between a mobile phase (eluent) and a stationary phase (packing material of the column) [16]. As the mobile phase carries the sample through the column, different constituents interact with the stationary phase to varying degrees, leading to their separation based on retention time [17]. Following separation, a detection unit is required to recognize the analytes as they elute from the column. Among the various detection methods available, UV-Vis detection remains one of the most frequently used detectors in HPLC systems due to its robustness, versatility, and wide applicability [18] [19].

This article explores the fundamental principles of how HPLC separation combines with UV detection to enable precise quantification, framed within research comparing the linearity and range of HPLC with standalone UV-Vis methods. Understanding this synergy is crucial for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on accurate and reliable analytical data.

Principles of Separation and Detection

The HPLC Separation Mechanism

The separation efficiency of HPLC hinges on the differential interaction of sample molecules with the stationary phase. Molecules that interact strongly with the packing material are retarded longer, while those with weaker interactions pass through more quickly [16]. The time a compound takes from the moment of injection until it is detected is its retention time (tR), a substance-specific characteristic under constant conditions [16]. Two primary elution modes are employed: isocratic elution, where the mobile phase composition remains constant, and gradient elution, where the mobile phase composition is changed during the separation to favor the elution of more strongly retained analytes [16].

Fundamentals of UV-Vis Detection

UV-Vis detectors function by measuring the absorption of ultraviolet or visible light by analyte molecules as they pass through a flow cell. For absorption to occur, electrons within the analyte molecules must be promoted from a ground state to an excited state by incident photons [18]. The specific energy of this transition corresponds to a particular wavelength, according to the equation ( E = hc / \lambda ), where ( E ) is energy, ( h ) is Planck's constant, ( c ) is the velocity of light, and ( \lambda ) is the wavelength [18]. This absorption converts a physiochemical property of the analyte into an electrical signal proportional to the analyte's concentration, enabling both identification and quantification [19].

UV detectors are predominantly used in the 200–400 nm wavelength range, covering UV and the lower part of the visible spectrum [18]. The key types of UV-Vis detectors include:

- Variable Wavelength Detector (VWD): Uses a single, selected wavelength to illuminate the sample, offering high sensitivity [19].

- Diode Array Detector (DAD) / Multiple Wavelength Detector (MWD): Exposes the sample to the entire spectrum, allowing for simultaneous measurement at all wavelengths. This is preferred for complex mixtures, unknown samples, and peak purity analysis [19].

Quantitative Comparison of HPLC Detectors

While UV-Vis is a workhorse, selecting a detector depends on the analyte's properties and the required sensitivity. The table below compares standard HPLC detection methods, highlighting their performance and limitations for quantification [19].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common HPLC Detectors

| Detection Method | Analytic Requirements | Typical Detection Limit | Linear Dynamic Range | Universal or Selective | Destructive? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis (UVD) | Absorbs UV-Vis light (190-800 nm) | Nanograms | Wide | Selective | No |

| Fluorescence (FLD) | Native fluorophore or fluorescent tag | Femtograms | Wide | Highly Selective | No |

| Refractive Index (RID) | Difference in RI from mobile phase | Micrograms | Limited | Universal | No |

| Evaporative Light Scattering (ELSD) | Non- and semi-volatile | Nanograms | Non-linear | Near-Universal | Yes |

| Charged Aerosol (CAD) | Non- and semi-volatile | Picograms | Wide (>4 orders) | Near-Universal | Yes |

| Electrochemical (ECD) | Undergoes redox reaction | Femtograms | Wide | Selective | Yes |

| Mass Spectrometry (MS) | Volatile, ionizable | Picograms | Wide | Highly Selective | Yes |

Linearity and Range: HPLC-UV vs. Standalone UV-Vis

The combination of HPLC separation with UV detection significantly enhances the reliability of quantification compared to standalone UV-Vis spectroscopy. A key advantage is the mitigation of matrix effects. In a direct UV-Vis measurement, interfering substances in a complex sample like plasma can absorb light at the same wavelength as the analyte, leading to inaccurate concentration readings [20]. HPLC physically separates the analytes from these interferents before they reach the detector, ensuring that the UV signal is specific to the target compound.

This is critically important in fields like therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). For instance, an HPLC-UV method developed for the simultaneous quantification of isosorbide dinitrate and sildenafil in human plasma demonstrated excellent linearity for both drugs—ISDN from 0.01–10.0 µg/mL and SIL from 0.025–10.0 µg/mL—with low quantitation limits [20]. This wide linear range in a complex biological matrix showcases the power of combining separation with detection, a feat difficult to achieve with direct UV-Vis.

Experimental Protocols for HPLC-UV Quantification

Detailed Methodology: Drug Monitoring in Plasma

The following protocol, adapted from a study on simultaneous drug quantification, illustrates a robust HPLC-UV method development and validation process [20].

- Analytical Column: Nova-Pack C18, 4 µm particle size.

- Mobile Phase: Acetonitrile and acetate buffer (5 mM; pH 5) in a ratio of 39:61 % v/v.

- Flow Rate: 1.1 mL/min.

- Detection Wavelength: 214 nm.

- Injection Volume: 50 µL.

- Column Temperature: Room temperature.

- Run Time: < 10 minutes.

Sample Preparation: Human plasma samples were spiked with analyte standards. Proteins were likely precipitated using an organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile), followed by centrifugation. The supernatant was then injected into the HPLC system [20].

Validation Data: The method was validated per ICH and US FDA guidelines.

- Linearity: >0.999 for both analytes.

- LOQ (Limit of Quantification): 0.01 µg/mL for ISDN and 0.020 µg/mL for SIL.

- Accuracy: Recovery rates of 104.9% (ISDN) and 105.55% (SIL) from spiked plasma.

Detailed Methodology: c-di-GMP Analysis in Bacterial Cells

This protocol for quantifying a bacterial secondary messenger demonstrates application in microbiology [21].

- HPLC System: Agilent 1100 HPLC with UV detector.

- Column: Reverse-phase C18 column (2.1 × 40 mm, 5 µm).

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM ammonium acetate in water.

- Mobile Phase B: 10 mM ammonium acetate in methanol.

- Elution: Gradient elution.

- Detection Wavelength: 253 nm (absorption maximum for c-di-GMP).

Sample Preparation:

- Grow bacterial cells (e.g., Pseudomonas aeruginosa) to the desired stage.

- Harvest a culture volume equivalent to 1 mL at OD₆₀₀ = 1.8 by centrifugation (16,000 × g, 2 min, 4°C).

- Wash the cell pellet twice with 1 mL of ice-cold PBS.

- Resuspend the pellet in 100 µL of ice-cold PBS and incubate at 100°C for 5 minutes.

- Add ice-cold ethanol to a final concentration of 65% to extract c-di-GMP.

- Centrifuge and retain the supernatant.

- Dry the supernatant in a vacuum concentrator and reconstitute for HPLC analysis.

Quantification: c-di-GMP levels are quantified by comparing peak areas against a standard curve of known concentrations and normalized to total cellular protein [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for HPLC-UV Analysis

| Item | Function & Importance | Example from Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| C18 Reverse-Phase Column | The stationary phase for separation; the heart of the HPLC system. Separation depends on the column's chemistry, length, and particle size. | Nova-Pack C18, 4 µm [20]; Reverse-phase C18 (2.1 × 40 mm, 5 µm) [21] |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Act as the mobile phase to carry analytes through the system. High purity is critical to minimize UV background noise and prevent column damage. | Acetonitrile [20]; Methanol [21] |

| Buffer Salts | Modify the mobile phase pH and ionic strength to control analyte ionization, retention, and separation efficiency. | Ammonium acetate [21]; Acetate Buffer [20] |

| Analytical Standards | Pure substances used to create calibration curves for identifying and quantifying analytes based on retention time and peak area. | c-di-GMP (Bio-log) [21]; Isosorbide Dinitrate & Sildenafil [20] |

| Protein Precipitation Reagents | Essential for bioanalysis; remove proteins from biological samples (e.g., plasma) to reduce matrix interference and protect the HPLC column. | Acetonitrile (implied) [20]; Ethanol [21] |

| Syringe Filters | Used to clarify and sterilize samples prior to injection, removing particulates that could clog the HPLC system. | Hydrophobic PTFE, 0.45 µm [21] |

Critical Factors Influencing UV Detection and Quantification

Wavelength Selection and Solvent Effects

Selecting the optimal detection wavelength is paramount for sensitivity. While λmax (wavelength of maximum absorption) of the analyte is often chosen, the featureless nature of many solution-based UV spectra can make this difficult [18]. Furthermore, the choice of mobile phase can induce bathochromic (red) shifts or hypsochromic (blue) shifts in the absorbance spectrum. For example, changing the solvent for propanone from hexane to water shifts its absorption maximum from 280 nm to 257 nm [18]. This underscores the necessity of performing wavelength selection and calibration under the same eluent conditions used for the analysis.

The Impact of pH and Temperature

Variations in pH can drastically alter UV spectra, particularly for ionizable compounds, by shifting the equilibrium between different molecular forms [18]. Buffers help control pH but can also absorb UV light at low wavelengths, increasing background noise. Temperature fluctuations can also affect UV spectra and must be controlled, especially when using a column oven [18]. Modern HPLC-UV systems have largely addressed historical concerns about wavelength calibration robustness, making quantification at λmax a reliable strategy [18].

The synergy between HPLC separation and UV detection creates a powerful tool for accurate quantification across diverse scientific fields. The physical separation of analytes from complex matrices prior to detection overcomes the fundamental limitation of direct UV-Vis spectroscopy, which is susceptibility to interference. This enables researchers to achieve excellent linearity and a wide dynamic range even in challenging samples like human plasma or bacterial extracts. While mass spectrometric detectors offer superior specificity and sensitivity, UV detectors remain a dominant force due to their robustness, cost-effectiveness, and broad applicability. For drug development professionals and researchers, a deep understanding of how separation and UV detection principles combine is essential for developing reliable, reproducible, and validated analytical methods.

In analytical chemistry, the dynamic range of an instrument describes the concentration interval over which it can produce a quantifiable response, bounded by its lower limit of quantification (LOQ) and upper limit of quantification. This parameter fundamentally distinguishes High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) from UV-Vis spectroscopy. While UV-Vis spectroscopy measures absorbance directly from a sample without prior separation, HPLC integrates a separation mechanism with detection, enabling it to isolate analytes from complex matrices before measurement. This inherent difference in design principles translates into significant practical advantages for HPLC in terms of working range, particularly when analyzing complex samples or mixtures where component interference would otherwise compromise accuracy.

Theoretical Foundations: Core Mechanisms Defining Instrument Capability

The fundamental distinction in dynamic range between these techniques stems from their core operational mechanisms. UV-Vis spectroscopy functions as a concentration-sensitive technique, where the measured absorbance is directly proportional to the analyte's concentration according to the Beer-Lambert law. However, this relationship becomes non-linear at higher concentrations due to phenomena such as stray light or chemical interactions. More critically, in mixtures, spectral overlapping of different components can severely distort measurements, effectively narrowing the usable concentration range for any single analyte [22].

In contrast, HPLC is primarily a separation technique coupled with a detection system (often UV-Vis itself). The chromatographic process physically separates analytes from interfering matrix components and from each other before they reach the detector. This separation eliminates the problem of spectral overlap that plagues direct UV-Vis analysis. Consequently, the HPLC detector primarily encounters individual, purified analyte bands, allowing it to operate effectively across a much broader concentration range for each component [23] [22]. The dynamic range in HPLC is therefore less limited by the detector's inherent capabilities and more by the separation efficiency and the detector's linear response to isolated analytes.

Comparative Experimental Data: Quantitative Performance Assessment

Table 1: Comparison of Validated Method Parameters for Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Compound / Matrix | Analytical Method | Linear Range | Correlation Coefficient (r²) | Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repaglinide (Tablet) | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | 5-30 μg/mL | >0.999 | Not Specified | [12] |

| Repaglinide (Tablet) | HPLC-UV | 5-50 μg/mL | >0.999 | Not Specified | [12] |

| Terbinafine HCl (Bulk & Formulation) | UV-Vis Spectroscopy | 5-30 μg/mL | 0.999 | 1.30 μg | [5] |

| Bakuchiol (Cosmetic Products) | HPLC-DAD | Quantified in complex oil/emulsion matrices | Comparable to NMR | Not Specified | [23] |

| Bakuchiol (Cosmetic Products) | Direct UV-Vis | Failed in emulsions due to incomplete dissolution | N/A | N/A | [23] |

| DOTATATE (Radiopharmaceutical) | HPLC-UV | 0.5-3 μg/mL | 0.999 | 0.1 μg/mL | [24] |

Experimental data consistently demonstrates HPLC's superior dynamic range. A direct comparison study of repaglinide analysis showed that while UV-Vis was linear from 5-30 μg/mL, the HPLC method maintained linearity from 5-50 μg/mL, covering a 66% wider concentration range [12]. Furthermore, research on bakuchiol in cosmetic serums highlighted a critical practical limitation of UV-Vis: it failed to provide proper quantification in oil-in-water emulsions (samples 5 and 6) due to incomplete dissolution and extraction issues. HPLC, however, successfully quantified bakuchiol in these complex matrices, including one sample containing 3.6% bakuchiol, demonstrating its robustness in real-world applications where analyte concentration and matrix complexity vary widely [23].

Detailed Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Linearity Validation

Protocol 1: Establishing UV-Vis Linearity and Range

The following generalized protocol is adapted from validated methods for compounds like terbinafine hydrochloride [5]:

- Standard Stock Solution: Accurately weigh 10 mg of reference standard and dissolve in a suitable solvent (e.g., water, methanol) in a 100 mL volumetric flask. Make up to volume to obtain a 100 μg/mL stock solution.

- Working Standard Solutions: Pipette aliquots (e.g., 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0, 2.5, 3.0 mL) of the stock solution into a series of 10 mL volumetric flasks. Dilute to volume with the same solvent to create a concentration series (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 μg/mL).

- Absorbance Measurement: Scan each solution against a solvent blank in the UV range (200-400 nm) or measure the absorbance at the predetermined λmax (e.g., 283 nm for terbinafine HCl).

- Calibration Curve: Plot the measured absorbance against the corresponding concentrations. Perform linear regression analysis. The method is considered linear if the correlation coefficient (r²) is ≥ 0.995 or 0.999, as per ICH guidelines [25] [12] [5].

Protocol 2: Establishing HPLC-UV Linearity and Range

This protocol is summarized from validated methods for repaglinide and Ga-68-DOTATATE [12] [24]:

- Standard Stock Solution: Prepare a stock solution of the analyte at a high concentration (e.g., 1000 μg/mL) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., methanol, mobile phase).

- Calibration Standards: Dilute the stock solution with mobile phase to create at least five concentrations covering the expected range (e.g., from 5-50 μg/mL for repaglinide, or 0.5-3 μg/mL for DOTATATE).

- Chromatographic Analysis: Inject each standard solution (e.g., 20 μL) into the HPLC system. Typical conditions include:

- Column: Reverse-phase C18 (e.g., 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm).

- Mobile Phase: Isocratic or gradient elution with a mixture of methanol/water or acetonitrile/water, sometimes with pH modifiers (e.g., 0.1% TFA).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection: UV detector at a specific wavelength (e.g., 241 nm for repaglinide, 220 nm for DOTATATE).

- Calibration Curve: Plot the peak area (or height) of the analyte against the injected concentration. Perform linear regression. The method is validated for linearity if r² ≥ 0.999, and the residuals are randomly distributed [25] [24].

Diagram 1: Workflow for validating the linearity and range of an analytical method, applicable to both HPLC and UV-Vis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for HPLC and UV-Vis Analysis

| Item | Function in Analysis | Common Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase components; high purity minimizes baseline noise and preserves the column. | Acetonitrile, Methanol, Water (with 0.1% TFA for modifier) [12] [24] |

| Reverse-Phase C18 Column | The core of separation; stationary phase that interacts differently with analytes to separate them. | Agilent TC-C18, 250 x 4.6 mm, 5 μm [12] |

| Reference Standard | Used to prepare calibration standards for identifying the analyte and constructing the calibration curve. | Certified pure analyte (e.g., Repaglinide, DOTATATE) [12] [24] |

| Volumetric Glassware | For precise preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions to ensure accuracy. | Class A volumetric flasks and pipettes [5] |

| UV/VIS Cuvettes | Hold the sample solution for measurement in the spectrophotometer; must have matched optical pathlengths. | Quartz cuvettes (for UV range) [12] |

| Syringe Filters | Clarify samples before injection into the HPLC to remove particulates that could damage the column. | 0.45 μm or 0.22 μm pore size membranes [26] |

Visualization of Fundamental Distinctions

Diagram 2: Core distinction between HPLC and UV-Vis processes determining dynamic range. HPLC separates analytes before detection, avoiding interference and enabling a wider range.

The inherent capability of HPLC to offer a wider dynamic range than UV-Vis spectroscopy is not the result of a single component but a fundamental distinction in operational philosophy. UV-Vis is a direct measurement technique whose range is ultimately constrained by spectral interference and the Beer-Lambert law's limitations in mixtures. HPLC, functioning as an integrated separation-detection system, circumvents these limitations by physically resolving analytes prior to quantification. This allows the detector to measure each purified component effectively across a much broader concentration span. The consistent experimental evidence, demonstrating HPLC's successful application in complex matrices where UV-Vis fails, solidifies its position as the more powerful tool for quantitative analysis across diverse concentration levels, a critical requirement in drug development and modern analytical research.

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, the validation of analytical methods is paramount to ensure the reliability, accuracy, and consistency of data supporting drug development and quality control. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) Q2(R1) guideline, titled "Validation of Analytical Procedures: Text and Methodology," provides a standardized framework for this validation process, defining key parameters that must be evaluated [27]. Among these parameters, linearity and range are fundamental for establishing the quantitative capability of an analytical procedure.

According to ICH Q2(R1), linearity is defined as the "ability (within a given range) to obtain test results which are directly proportional to the concentration (amount) of analyte in the sample" [28]. The range is defined as "the interval between the upper and lower concentration of analyte in the sample for which it has been demonstrated that the analytical procedure has a suitable level of precision, accuracy and linearity" [27]. These parameters are not standalone considerations but are intrinsically linked; a method's linearity must be demonstrated throughout its specified range to prove its suitability for intended use.

This guide provides a detailed comparison of how linearity and range are applied and evaluated across two fundamental analytical techniques: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectrophotometry. Through experimental case studies and a structured comparison of their performance against ICH Q2(R1) criteria, this article aims to equip researchers and scientists with the knowledge to select the most appropriate method for their specific analytical challenges.

ICH Q2(R1) Criteria for Linearity and Range

Defining the Parameters

The ICH Q2(R1) guideline provides specific acceptance criteria and experimental approaches for demonstrating linearity and range [27]. For linearity, a minimum of five concentration levels is recommended [28]. The relationship is typically evaluated by visually inspecting a plot of the analytical response against the analyte concentration and by applying statistical analysis to the data, using parameters such as the correlation coefficient (r), y-intercept, slope, and residual sum of squares [27] [28].

The required range varies depending on the intended application of the analytical procedure [27]:

- Assay of Drug Substance/Product: 80% to 120% of the test concentration.

- Content Uniformity: 70% to 130% of the test concentration.

- Dissolution Testing: ±20% over the specified range (e.g., from 60% to 100% for an immediate-release product with NLT 80% specification).

- Impurity Determination: From the reporting level (e.g., the Quantitation Limit or LOQ) to 120% of the impurity specification.

It is critical to differentiate between the linearity of the response function and the linearity of results. The response function describes the relationship between the instrument's signal and the analyte concentration. In contrast, the linearity of results refers to the proportionality between the theoretical concentration of the sample and the final test result calculated from the calibration model. The ICH guideline's definition specifically addresses the latter, emphasizing the need for test results to be proportional to the analyte amount [29].

Experimental Design and Acceptance Criteria

The establishment of linearity involves preparing and analyzing a series of standard solutions at different concentrations across the intended range. A calibration curve is then constructed by plotting the analytical response against the concentration. The following table summarizes typical acceptance criteria for different types of methods:

Table 1: Typical Acceptance Criteria for Linearity in Analytical Methods

| Method Type | Correlation Coefficient (r) | Bias at 100% (%y-intercept) | Key Range Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assay (HPLC/UV-Vis) | Not Less Than (NLT) 0.999 | Not More Than (NMT) 2.0% | Covers 80-120% of test concentration [28]. |

| Related Substances (HPLC) | NLT 0.997 | NMT 5.0% | From reporting level (LOQ) to 120% of specification [28]. |

| Dissolution (UV-Vis) | NLT 0.999 | NMT 2.0% | ±20% over the specified range (e.g., 60-100%) [28]. |

For impurity methods, if an impurity is poorly resolved from the main active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) peak, linearity should be demonstrated by spiking the impurity into a solution containing the API at the test concentration. This approach ensures that the accuracy of the impurity quantification is assessed in a matrix that reflects the actual sample analysis conditions [28].

Case Study: Levofloxacin Analysis by HPLC vs. UV-Vis

A direct comparative study of HPLC and UV-Vis for the analysis of Levofloxacin released from a mesoporous silica microspheres/nano-hydroxyapatite (n-HA) composite scaffold provides a robust dataset to evaluate the performance of both techniques against ICH Q2(R1) principles [3].

Experimental Protocols

HPLC Method Details: [3]

- Equipment: Shimadzu liquid chromatograph with LC-2010AHT pump and UV-Vis detector.

- Column: Sepax BR-C18 (250 × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size).

- Mobile Phase: A mixture of 0.01 mol/L KH₂PO₄, methanol, and 0.5 mol/L tetrabutylammonium hydrogen sulphate (75:25:4 ratio).

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min.

- Detection Wavelength: 290 nm.

- Injection Volume: 10 µL for assay.

- Internal Standard: Ciprofloxacin.

- Sample Preparation: Levofloxacin standards (0.05–300 µg/mL) in simulated body fluid (SBF) were mixed with internal standard, extracted with dichloromethane, and the supernatant was dried under nitrogen before reconstitution.

UV-Vis Method Details: [3]

- Equipment: UV-2600 UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

- Wavelength Selection: Scanning of standard solutions (5, 25, 50 µg/mL) from 200–400 nm to determine the maximum absorption wavelength.

- Sample Preparation: Direct analysis of Levofloxacin standard solutions in SBF across the concentration range.

Results and Comparative Performance

The study established standard curves for both methods and calculated recovery rates at low, medium, and high concentrations to assess accuracy. The results are summarized in the tables below.

Table 2: Linearity Comparison for Levofloxacin Analysis

| Parameter | HPLC Method | UV-Vis Method |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Concentration Range | 0.05 - 300 µg/mL | 0.05 - 300 µg/mL |

| Regression Equation | y = 0.033x + 0.010 | y = 0.065x + 0.017 |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | 0.9991 | 0.9999 |

| Correlation Coefficient (r) | ~0.9995 (calculated from R²) | ~0.99995 (calculated from R²) |

Table 3: Accuracy (Recovery) Data for Levofloxacin Analysis

| Concentration Level | HPLC Recovery Rate (%) | UV-Vis Recovery Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Low (5 µg/mL) | 96.37 ± 0.50 | 96.00 ± 2.00 |

| Medium (25 µg/mL) | 110.96 ± 0.23 | 99.50 ± 0.00 |

| High (50 µg/mL) | 104.79 ± 0.06 | 98.67 ± 0.06 |

While both techniques demonstrated excellent correlation coefficients (r > 0.999), a critical examination of the accuracy data reveals a significant finding. The HPLC method showed variable and suboptimal recovery at the medium and high concentrations (110.96% and 104.79%, respectively), falling outside the typical acceptance criterion of 98-102% for accuracy. In contrast, the UV-Vis method demonstrated consistently accurate recovery across all three concentration levels, all within 96-100% [3].

The study concluded that for measuring drug concentration in complex, impure samples like composite scaffolds, UV-Vis can be less accurate due to potential interference from other components that also absorb light. HPLC, with its superior separation power, is the preferred method in such complex matrices because it can isolate the target analyte from impurities before detection, thereby providing more reliable results despite the recovery anomalies observed in this specific experimental setup [3].

Comparative Analysis: HPLC and UV-Vis for Linearity and Range

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key decision points and technical considerations when selecting and implementing these analytical methods.

Key Differentiating Factors

Specificity and Interference: The core difference lies in specificity. HPLC is a separation-based technique that physically resolves the analyte from other sample components before detection, making it highly specific and suitable for complex matrices like biological fluids or formulated products [3]. UV-Vis is a direct measurement technique that lacks separation; it measures the total absorbance at a specific wavelength, making it vulnerable to interference from any co-eluting absorbing species, which can compromise both linearity and accuracy [3].

Application Scope: UV-Vis is well-suited for analyzing pure solutions of the analyte or simple mixtures where potential interferents are known and absent, such as in dissolution testing of single-component drug products [28]. HPLC is indispensable for assays requiring high specificity, such as related substance quantification, stability-indicating methods, and analysis of drugs in complex biological matrices [3] [28].

Method Development and Validation Complexity: HPLC method development is typically more complex, involving optimization of the column, mobile phase composition, and gradient. UV-Vis method development is generally simpler, primarily focusing on wavelength selection [3]. However, as demonstrated in the levofloxacin case study, a high R² value in UV-Vis does not automatically guarantee accuracy in impure samples, underscoring the need for rigorous validation that includes specificity testing [3] [29].

Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials commonly required for conducting linearity and range studies according to ICH Q2(R1), with notes on their application in HPLC and UV-Vis methods.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Linearity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Substance (Analyte) Reference Standard | Primary standard for preparing calibration solutions of known concentration. | Required for both HPLC and UV-Vis. Should be of high and documented purity [3]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., Ciprofloxacin) | Added to samples to correct for variability in sample preparation and injection. | Primarily used in HPLC to improve precision [3]. Not typically used in routine UV-Vis. |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents (e.g., Methanol, Water) | Used as solvents for standards and as components of the mobile phase. | Essential for HPLC to ensure low UV background and prevent system damage [3]. |

| Buffer Salts (e.g., KH₂PO₄, Tetrabutylammonium bromide) | Modify mobile phase to control pH and ionic strength, improving chromatographic separation. | Critical for achieving peak symmetry and resolution in HPLC [3]. Not used in UV-Vis sample prep. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) or Sample Matrix | Mimics the actual sample environment to evaluate matrix effects on linearity and accuracy. | Used in both techniques to demonstrate the validity of the calibration in the presence of matrix components [3]. |

The comparative analysis of HPLC and UV-Vis spectrophotometry within the framework of ICH Q2(R1) linearity and range guidelines reveals a clear, application-dependent choice for scientists. While UV-Vis can be a valid, simple, and cost-effective technique for analyzing pure substances or in well-understood, simple matrices, its vulnerability to spectral interference is a critical limitation.

HPLC, with its superior separation power, provides the specificity necessary for accurate quantification in complex samples, making it the more robust and generally reliable technique for most pharmaceutical applications, including assay, content uniformity, and related substance determination. The experimental data on Levofloxacin analysis confirms that a high correlation coefficient (R²) is necessary but not sufficient to guarantee method validity; accuracy and specificity must be rigorously demonstrated within the intended range and in the context of the sample matrix.

Therefore, the choice between HPLC and UV-Vis should be guided by the nature of the sample matrix and the required specificity, with HPLC being the preferred choice for complex formulations and stability-indicating methods, and UV-Vis serving as a viable option for simpler, well-defined applications where interference is not a concern.

Practical Applications: Implementing HPLC and UV-Vis Methods for Accurate Quantification

In pharmaceutical research and drug development, the accuracy of analytical data is paramount. Calibration curves serve as the fundamental link between an instrument's response and the true concentration of an analyte, forming the basis for reliable quantitative analysis. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Ultraviolet-Visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis) represent two cornerstone techniques for quantitative analysis, each with distinct advantages and limitations in calibration practices. Proper calibration ensures that instruments provide accurate, reproducible results, directly impacting drug development timelines, regulatory compliance, and therapeutic decision-making [30] [31]. This guide objectively compares calibration practices for HPLC and UV-Vis methods, examining linearity, range, and practical implementation through experimental data and established protocols.

Fundamental Concepts in Calibration Curve Design

Calibration Curve Definitions and Regression Analysis

A calibration curve is a regression model used to predict unknown concentrations of analytes based on the instrumental response to known standards. In a simple linear regression, the relationship is expressed as ( Y = a + bX ), where ( Y ) is the instrument response, ( X ) is the concentration, ( b ) is the slope, and ( a ) is the y-intercept [31]. The method of least squares is typically used to determine the line of best fit by minimizing the sum of squared residuals (the differences between observed and predicted values) [31]. The assumption is that measurement error is normally distributed and consistent across all concentrations, though this assumption must be verified for valid results.

The Critical Importance of Weighting Factors

When calibration spans a wide concentration range (often more than one order of magnitude), the variance of data points frequently differs across the range, a phenomenon known as heteroscedasticity. With unweighted regression, larger absolute deviations at higher concentrations disproportionately influence the regression line, resulting in significant inaccuracies at the curve's lower end [32] [31].

Weighted least squares linear regression (WLSLR) counters this by assigning greater importance to data points with smaller variances. Common weighting factors include:

- 1/x: Counters proportional error across the range

- 1/x²: Used when variance increases dramatically with concentration

- 1/x⁰.⁵: A moderate weighting approach [32]

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines recommend using "the simplest model that adequately describes the concentration-response relationship using appropriate weighting" [32] [31]. Selecting the optimal weighting factor is typically done by comparing the sum of the absolute values of relative error (ΣRE) for different weighting schemes, choosing the simplest model that minimizes this error [32].

HPLC Calibration: Best Practices and Protocols

HPLC System Calibration and Qualification

Proper HPLC calibration extends beyond the analytical curve to encompass instrument performance verification. Key components requiring regular calibration include:

Table 1: HPLC System Calibration Components

| Component | Calibration Parameters | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Pump | Flow rate accuracy, pressure monitoring | Directly affects retention time reproducibility and resolution [30] |

| Detector | Wavelength accuracy, linearity test | Ensures accurate response measurement across concentration range [30] |

| Injector | Injection volume accuracy, repeatability | Impacts precision of sample introduction [30] |

| Column | Plate number (N), resolution, peak symmetry | Measures separation efficiency [30] |

Regular calibration using certified reference materials (CRMs) and comprehensive documentation are essential for maintaining regulatory compliance and data integrity [30].

HPLC Calibration Curve Design and Optimization

Effective calibration curve design for HPLC requires strategic concentration selection. Rather than using true serial dilutions, most practitioners recommend a mixed design with higher point density at lower concentrations to improve accuracy in this critical region [33].

For example, a well-designed calibration curve might use concentrations of:

- 1, 2, 5, 10, 20 μg/mL for assays where precision at lower concentrations is critical [33]

This approach counters the natural weighting of unweighted regression toward higher concentrations, providing better precision throughout the analytical range [33].

Experimental Protocol: HPLC-UV Method for Antihypertensive Drugs

A developed HPLC-UV method for simultaneous determination of antihypertensive drugs in pharmaceuticals and plasma demonstrates proper calibration practices [34]:

Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: RP-CN column (4.6 mm I.D. × 200 mm, 5 μm)

- Mobile Phase: Acetonitrile-methanol-10 mmol orthophosphoric acid pH 2.5 (7:13:80, v/v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1.0 mL/min

- Detection: UV at 235 nm

- Injection Volume: 20 μL

- Temperature: 30°C [34]

Calibration Curve Establishment:

- Linearity Ranges:

- Amlodipine (AML): 0.1-18.5 μg/mL

- Olmesartan (OLM): 0.4-25.6 μg/mL

- Valsartan (VAL): 0.3-15.5 μg/mL

- Hydrochlorothiazide (HCT): 0.3-22 μg/mL [34]

- Standard solutions were prepared by serial dilution from stock solutions (1 mg/mL in methanol)

- Each concentration was injected in triplicate

- The average peak area was plotted against concentration to generate calibration curves

Performance Metrics:

- Reproducibility: RSD ≤6.9% for all analytes

- Accuracy: Relative mean error ≤10.6% [34]

This protocol highlights the comprehensive approach needed for robust HPLC calibration in complex matrices.

UV-Vis Spectrophotometry Calibration: Approaches and Considerations

UV-Vis Method Characteristics and Calibration Practices

UV-Vis spectrophotometry offers simplicity, rapid analysis, and cost-effectiveness for quantitative analysis. However, its applicability depends on the analyte having a suitable chromophore and the absence of significant interferences in the sample matrix. Without chromatographic separation, UV-Vis is more susceptible to matrix effects than HPLC, particularly in complex biological samples [3].

Calibration practices for UV-Vis typically follow similar regression principles as HPLC, though the working range may be narrower due to the Beer-Lambert law deviations at higher concentrations and sensitivity limitations at lower concentrations.

Experimental Protocol: UV-Vis Method for Levofloxacin Analysis

A study comparing HPLC and UV-Vis for levofloxacin quantification demonstrates UV-Vis calibration practices:

UV-Vis Methodology:

- Wavelength Selection: Standard solutions scanned from 200-400 nm to determine maximum absorption wavelength

- Sample Preparation: Standard solutions prepared in simulated body fluid

- Calibration Range: 0.05-300 μg/mL [3]

Calibration Performance:

- Regression Equation: y = 0.065x + 0.017

- Coefficient of Determination (R²): 0.9999 [3]

Despite the excellent R² value, comparative studies revealed limitations in accuracy for complex samples compared to HPLC [3].

Direct Comparison: HPLC vs. UV-Vis Calibration Performance

Experimental Data Comparison

A direct methodological comparison study for levofloxacin quantification provides objective performance data:

Table 2: HPLC vs. UV-Vis Method Performance Comparison for Levofloxacin [3]

| Parameter | HPLC Method | UV-Vis Method |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.05-300 μg/mL | 0.05-300 μg/mL |

| Regression Equation | y = 0.033x + 0.010 | y = 0.065x + 0.017 |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | 0.9991 | 0.9999 |

| Recovery (Low Concentration, 5 μg/mL) | 96.37 ± 0.50% | 96.00 ± 2.00% |

| Recovery (Medium Concentration, 25 μg/mL) | 110.96 ± 0.23% | 99.50 ± 0.00% |

| Recovery (High Concentration, 50 μg/mL) | 104.79 ± 0.06% | 98.67 ± 0.06% |

| Application in Complex Matrices | Suitable for drug-loaded composite scaffolds | Less accurate for complex composite scaffolds |

Critical Analysis of Comparative Performance

While both techniques showed excellent linearity over the same concentration range, HPLC demonstrated superior precision (evidenced by smaller standard deviations in recovery studies) and better accuracy in complex samples [3]. The UV-Vis method, despite its excellent R² value of 0.9999, was deemed insufficient for accurately measuring drug concentration in complex composite scaffolds, highlighting that correlation coefficient alone is an inadequate measure of method reliability [3] [31].

For analysis of complex biological samples, HPLC consistently outperforms UV-Vis due to its separation capability, which minimizes interference from matrix components. The study concluded that "it is not accurate to measure the concentration of drugs loaded on the biodegradable composite composites by UV-Vis" and that "HPLC is the preferred method to evaluate sustained release characteristics" [3].

Method Selection Workflow and Research Reagent Solutions

Analytical Method Selection Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for HPLC and UV-Vis Calibration

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Provides traceable standard for accurate calibration | Essential for both HPLC and UV-Vis; must be of highest purity [30] |

| HPLC-Grade Solvents | Mobile phase preparation | Minimize baseline noise and interference; filtered and degassed [34] [3] |

| Chromatography Columns | Compound separation | Select based on analyte properties (C18, CN, etc.) [34] [3] |

| Buffer Components | Mobile phase pH control | Use high-purity salts; adjust pH carefully [34] [35] |

| Internal Standards | Correction for procedural losses | Especially critical for HPLC of complex samples [3] [31] |

The selection between HPLC and UV-Vis methods for calibration curve establishment depends on the specific analytical requirements. HPLC provides superior specificity, accuracy, and precision for complex matrices, particularly in pharmaceutical and biological applications, making it the preferred technique for regulated bioanalytical work. UV-Vis offers simplicity, rapid analysis, and cost-effectiveness for simpler applications where interferents are absent or minimal. Both techniques require careful attention to calibration design, with appropriate weighting factors necessary for wide concentration ranges. The correlation coefficient alone should not determine method acceptability; instead, comprehensive validation including accuracy, precision, and recovery studies across the analytical range should guide method selection and optimization.

Vancomycin, a tricyclic glycopeptide antibiotic, is a crucial therapeutic agent for severe Gram-positive bacterial infections, particularly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Its clinical use is complicated by a narrow therapeutic window; subtherapeutic concentrations can lead to treatment failure and antimicrobial resistance, while supratherapeutic concentrations increase the risk of nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity [36] [37]. For serious MRSA infections, the therapeutic trough concentration target is 10–20 mg/L, with a recommended area under the concentration-time curve to minimum inhibitory concentration (AUC/MIC) ratio of ≥400 for optimal efficacy and safety [36] [38]. Consequently, precise therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is essential for patient-specific dose optimization, especially in critically ill patients and those with augmented renal clearance or organ transplantation, where pharmacokinetics are highly variable [36] [38].

Analytical Methodologies for Vancomycin Quantification

Several analytical techniques are available for quantifying vancomycin in biological fluids, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

- Immunoassays: Methods like chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) are widely used in clinical settings due to their operational simplicity and rapid turnaround [38] [37]. However, they can be susceptible to interference from metabolites or other substances, potentially leading to falsely elevated results, particularly in patients with renal impairment [38].

- Chromatographic Methods: High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) is recognized for its high sensitivity, superior specificity, and low sample volume requirements [39] [38] [37]. It effectively avoids cross-reactivity issues and is considered a reference method for vancomycin TDM in complex patient populations [38].

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: While cost-effective and simple, UV-Vis lacks the inherent separation capabilities of HPLC, making it prone to interference from complex matrices like plasma and generally unsuitable for direct vancomycin quantification in biological samples [23] [40].

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Vancomycin TDM

| Technique | Key Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-UV | Separation on column, UV detection | High specificity & sensitivity, low sample volume, avoids metabolite interference | Requires skilled personnel, longer analysis time, complex instrumentation [36] [39] [38] |

| Immunoassay (e.g., CMIA) | Antigen-antibody binding with chemiluminescent signal | Fast, simple, suitable for high-throughput clinical labs | Potential for cross-reactivity and falsely elevated results [38] [37] |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Absorption of ultraviolet/visible light | Low cost, simple operation, fast analysis | Poor specificity in complex matrices, prone to interference [23] [40] |

Case Study: HPLC-UV Method Development and Validation

A recent study developed and validated a simple, reproducible, and green HPLC-UV method for quantifying vancomycin in human plasma, specifically applied to critically ill patients [36].

Experimental Protocol

- Sample Preparation: Plasma samples (0.3 mL) underwent a single-step deproteinization using 10% perchloric acid. After vortexing and centrifugation, the supernatant was injected into the HPLC system [36].

- Chromatographic Conditions:

- Column: C18 column

- Mobile Phase: Phosphate buffer (pH 2.8) and Acetonitrile (90:10, v/v)

- Flow Rate: 1 mL/min

- Detection: UV detection at 192 nm

- Runtime: 10 minutes [36]

- Method Validation: The method was rigorously validated according to international guidelines, assessing parameters including linearity, range, precision, accuracy, and recovery [36].

Key Findings on Linearity and Range

The method demonstrated excellent linearity over the concentration range of 4.5–80 mg/L, with a correlation coefficient (r²) of >0.99, confirming a direct proportional relationship between concentration and detector response [36]. The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) was established at 4.5 mg/L, ensuring adequate sensitivity to measure trough concentrations at the low end of the therapeutic range [36].

Table 2: Validation Parameters for the HPLC-UV Method (4.5–80 mg/L)

| Validation Parameter | Result | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Linearity Range | 4.5 – 80 mg/L | - |

| Correlation Coefficient (r²) | > 0.99 | ≥ 0.99 [36] |

| Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ) | 4.5 mg/L | - |

| Intra-day Precision (CV%) | 2.99 – 8.39% | ≤ 15% [36] |

| Intra-day Accuracy (% Error) | 0.36 – 6.02% | ≤ 15% [36] |

| Inter-day Precision (CV%) | 2.71 – 6.06% | ≤ 15% [36] |

| Inter-day Accuracy (% Error) | 3.71 – 7.36% | ≤ 15% [36] |

| Recovery | 60.7 – 70.6% | - |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete experimental process for the HPLC-UV analysis of vancomycin in plasma.

Comparative Analysis: HPLC vs. UV-Vis for Vancomycin TDM

When evaluating HPLC and UV-Vis methods for pharmaceutical analysis, the critical distinction lies in HPLC's separation power before detection, which is absent in basic UV-Vis spectroscopy [23] [40].

- Specificity and Selectivity: The described HPLC method successfully separates vancomycin from plasma components, with a clean chromatogram showing no interfering peaks at vancomycin's retention time [36]. In contrast, UV-Vis measures total absorbance at a wavelength, making it impossible to distinguish vancomycin from other absorbing substances in plasma, leading to potential overestimation [23] [40].

- Linear Range and Sensitivity: The validated HPLC linear range of 4.5–80 mg/L [36] is fit-for-purpose for TDM. UV-Vis can be linear for standard solutions, but its effective range in biological matrices is severely compromised without separation.

- Application in Complex Matrices: The HPLC method was successfully applied to patient samples from critically ill patients [36]. UV-Vis is generally not reliable for direct measurement of drugs in complex biological samples like plasma due to lack of separation [23] [40].

Table 3: Direct Comparison of HPLC-UV and Standalone UV-Vis for Vancomycin Analysis

| Performance Characteristic | HPLC-UV Method | Standalone UV-Vis |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity in Plasma | High (Separation achieved) | Very Low (No separation) |

| Effective Linear Range in Plasma | 4.5 – 80 mg/L (Validated) | Not reliably established for plasma |

| LOD/LOQ in Plasma | LLOQ = 4.5 mg/L | Likely significantly higher |

| Susceptibility to Matrix Interference | Low | Very High |

| Suitability for TDM | Excellent, used in clinical studies [36] [38] | Poor, not suitable for direct plasma analysis |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following reagents and materials are fundamental for implementing the described HPLC-UV method for vancomycin analysis.

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC-UV Analysis of Vancomycin

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Protocol | Specification/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin Reference Standard | Calibration and Quality Control | Used to prepare standard solutions for the calibration curve [36] |

| Human Plasma | Biological matrix for analysis | Sample matrix from patients or donors [36] |