Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning of Fused Silica Optics: Mechanisms, Applications, and Damage Control

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of low-pressure plasma cleaning for maintaining the performance of fused silica optics in high-power laser systems and precision instruments.

Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning of Fused Silica Optics: Mechanisms, Applications, and Damage Control

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of low-pressure plasma cleaning for maintaining the performance of fused silica optics in high-power laser systems and precision instruments. It explores the foundational science behind plasma-organic contaminant interactions, detailing the radical-driven pathways for efficient removal. The content covers methodological approaches for in-situ application, including parameter optimization and process control. Critical troubleshooting aspects, such as preventing plasma-induced surface damage and nano-defect formation, are addressed. Finally, the technology is validated through comparative performance metrics, including laser-induced damage threshold recovery and transmittance restoration, offering researchers a validated framework for implementing this non-destructive cleaning technique.

The Science of Plasma Cleaning: Fundamental Mechanisms and Reactive Pathways

The Critical Challenge of Organic Contamination

In high-power laser systems, such as those used in inertial confinement fusion (ICF) facilities and advanced scientific research, the performance and longevity of large-aperture optical components are critically limited by surface contamination [1]. During prolonged service in vacuum-based intense laser systems, the surface chemical coatings of these optics inevitably accumulate organic contamination, leading to irreversible damage to the coatings and rapid degradation of optical performance under laser irradiation [1]. Experimental results have demonstrated that contamination on optical component surfaces can induce damage spots five times the size of the contaminants themselves under intense laser irradiation, reducing the laser damage threshold of optical components by approximately 60% [1].

Surface contaminants on optical components in intense laser systems primarily include particulate contaminants, organic contaminants, and moisture [1]. While effective control of particulate and moisture contamination has been largely achieved through methods such as negative-pressure cycling, air-knife purging, and temperature-regulated techniques, organic contaminants on large-aperture optical components remain a critical unresolved issue during prolonged system operation [1]. Free organic contaminants continuously deposit onto chemical coatings in vacuum environments during extended laser facility operation, where they undergo ablation or decomposition under intense laser irradiation, generating stray light that damages and detaches the chemical coatings from optical component surfaces [1].

The quantification and characterization of these contaminants require sophisticated analytical techniques. Laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) has emerged as a powerful method for quantitative analysis of manufacturing-induced trace contaminants on optical glass surfaces, enabling depth-resolved measurements through successive laser pulses applied to the same irradiation sites [2]. These measurements have evidenced surface contamination originating from polishing during glass manufacturing and correlated contaminant penetration depths with changes in optical properties [2].

Table 1: Primary Contamination Types and Their Impact on Fused Silica Optics

| Contaminant Type | Primary Sources | Impact on Optical Performance | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Compounds | Outgassing in vacuum environments, processing residues | Reduced laser damage threshold (~60% reduction), chemical coating damage, stray light generation [1] | XPS, LIFM [1] [3] |

| Particulate Contaminants | Laser-driven particle sources, manufacturing processes [4] | Localized intensification leading to damage initiation, growth upon subsequent laser exposure [4] | Automated microscopy [4] |

| Moisture | Ambient environment, processing | Not specified in available literature | Not specified |

| Metallic Impurities | Polishing compounds (Ce, La) [3] | Direct absorption of UV laser energy, reduced mechanical strength [3] | Calibration-free LIBS [2] |

Quantitative Analysis of Contamination Effects

Non-destructive evaluation methods have revealed strong correlations between surface defects and laser damage performance. UV laser-induced fluorescence imaging (LIFM) and photo-thermal deflection (PTD) can quantitatively distinguish differences in absorptive defect distributions in fused silica samples subjected to different post-processing steps [3]. The percentage of fluorescence defects and the weak absorption coefficient show strong relationships with damage threshold and damage density, confirming these non-destructive methods as effective tools for estimating damage performance of fused silica optics prior to utilization [3].

The relationship between contamination and laser-induced damage has been quantitatively established through systematic testing. Research has shown that the damage density of hydrofluoric (HF) acid-etched samples is two orders lower than that of non-etched samples, with longer etching times resulting in lower damage density [3]. Additionally, magnetorheological finishing (MRF) samples, despite decreasing sub-surface damage (SSD), often exhibit worse damage performance due to secondary pollution from MRF fluid residue on surfaces [3].

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Surface Defects on Laser Damage Performance

| Defect Parameter | Measurement Technique | Correlation with Damage Performance | Typical Values for High-Quality Optics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence Defect Area Percentage | Laser-Induced Fluorescence Imaging (LIFI) [3] | Strong negative correlation with damage threshold [3] | <0.1% after optimized DCE [3] |

| Weak Absorption Coefficient (at 355 nm) | Photo-Thermal Deflection (PTD) [3] | Direct correlation with damage density [3] | <1 ppm average absorption [3] |

| Surface Roughness | 3D Optical Profiler [5] | Affects light scattering and damage initiation | <2.86 µm after plasma processing [6] |

| Zero Probability Damage Threshold | Raster-scan testing [3] | Direct performance metric | 13.2-30.8 J/cm² at 355 nm [3] |

Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning: Mechanism and Protocols

Fundamental Principles

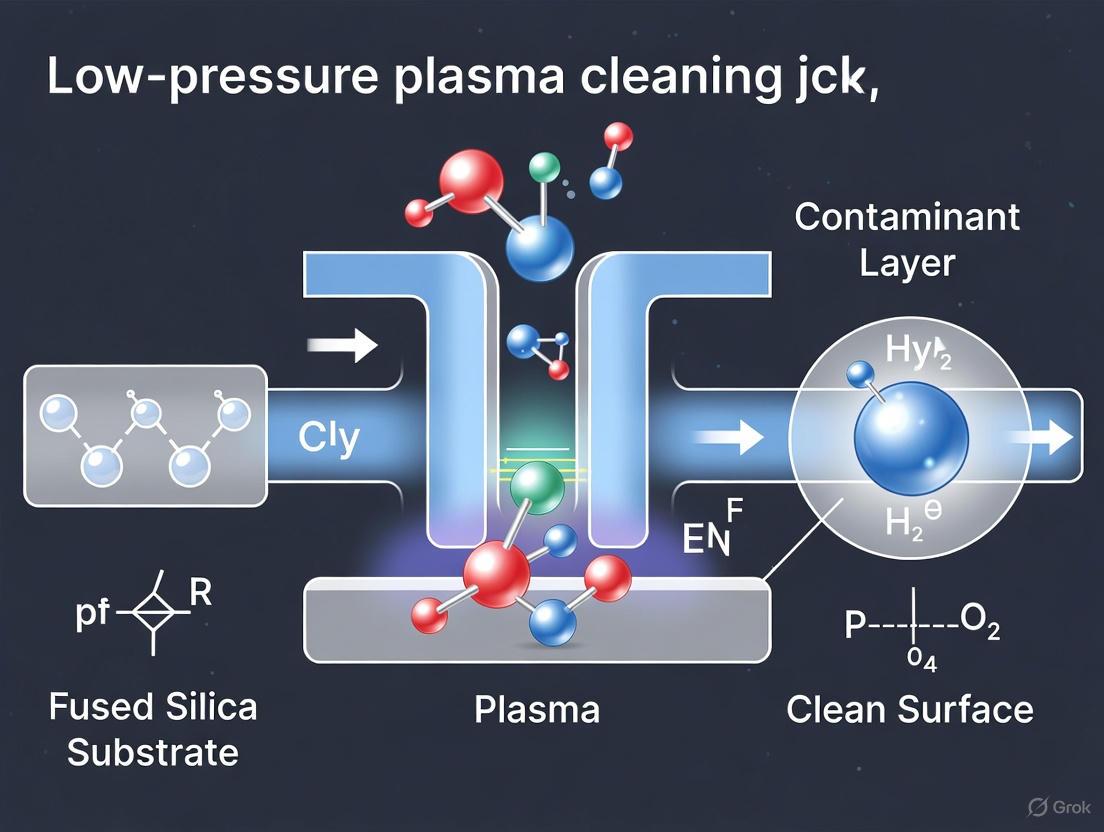

Low-pressure plasma cleaning technology has emerged as a promising solution for addressing organic contamination on high-power optics. This approach ionizes working gas via low-pressure radio-frequency (RF) capacitive coupling discharge, generating a large-area, uniform, diffuse plasma with randomly directed ion bombardment under relatively low pressure and temperature conditions [1]. The technology can efficiently and non-destructively clean optical components with chemical coatings that have large dimensions, complex structures, and high cleanliness requirements without causing secondary contamination [1].

The plasma cleaning process involves three main mechanisms: chemical cleaning, physical cleaning, and incineration [7]. In chemical plasma cleaning, the process gas in the cleaning chamber is excited by a high-frequency generator, producing radicals and ionized particles that react with contamination on the product surface, yielding H₂O and CO₂ as byproducts [7]. Physical plasma cleaning (sputtering) involves molecules of the process gas being accelerated by the high-frequency field, colliding with the product to be cleaned, and mechanically removing impurities through a micro-sandblasting effect [7]. Elevated temperature processes can also favor the outgassing of volatile substances that polymerize on the surface [7].

Experimental Protocol: Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning of Fused Silica Optics

Objective: To remove organic contamination from fused silica optics while minimizing surface damage and restoring optical performance.

Materials and Equipment:

- Low-pressure plasma cleaning system with RF generator (typically 13.56 MHz)

- Vacuum chamber with pressure control system

- Mass flow controllers for process gases

- Langmuir probe for plasma characterization

- Optical emission spectrometer

- Fused silica samples with organic contamination

- Transmittance measurement system

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare chemical-coated fused silica samples using sol-gel SiO₂ at 355 nm wavelength via dip-coating method [1].

- Use a pull-coating machine at 85 mm/min pull speed with 29 nm SiO₂ particle size at 25°C [1].

- Perform post-treatment of chemical coating with ammonia and hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) by placing post-treatment reagents and samples in a sealed glass container for 24 hours [1].

System Setup:

Plasma Parameter Optimization:

Cleaning Process:

- Initiate plasma discharge and maintain for predetermined duration (typically 45 minutes to several hours based on contamination level) [6].

- Monitor process parameters continuously to ensure stability.

- Terminate plasma and vent chamber after process completion.

Post-Cleaning Analysis:

Research Reagent Solutions for Plasma Cleaning Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plasma Cleaning Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Usage Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxygen (O₂) Gas | Primary reactive gas for organic contaminant removal [1] | Formation of reactive oxygen species that break down hydrocarbon contaminants [1] | High purity required to prevent introducing new contaminants |

| Argon (Ar) Gas | Inert gas for physical sputtering and plasma stabilization [1] | Diluent gas in mixtures, enhances ion bombardment efficiency [1] | Often used in combination with reactive gases |

| Sulfur Hexafluoride (SF₆) | Source of fluorine radicals for silica etching [5] | Chemical etching of fused silica surfaces: SiO₂ + 4F* → SiF₄ + O₂ [5] | Requires careful handling and disposal |

| Hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) | Surface treatment for chemical coatings [1] | Post-treatment of sol-gel SiO₂ coatings to enhance stability [1] | 24-hour treatment in sealed container |

| Sol-Gel SiO₂ | Anti-reflective coating material [1] | Dip-coating of fused silica substrates at 355 nm wavelength [1] | 29 nm particle size, pulled at 85 mm/min |

Molecular Dynamics Insights and Process Optimization

Advanced molecular dynamics simulations have provided critical insights into the atomic-scale interactions between plasma and fused silica surfaces. Studies utilizing Reactive Molecular Dynamics (RMD) models have simulated the cleaning process of organic contaminants under different bombardment energies and ion fluxes, revealing that oxygen plasma bombardment disrupts fused silica bonds, leading to successive sputtering of silicon-oxygen atoms [8]. The quantity of sputtered silicon atoms demonstrates a linear correlation with irradiation time, with significant damage onset observed beyond 33 eV, underscoring plasma's role in thinning fused silica [8].

These simulations have revealed that temperature is a crucial factor affecting surface damage during plasma cleaning [8]. The research establishes that pit defects and distinctive interface damage patterns elucidate the impact of neutral oxygen atoms, providing fundamental insights for achieving non-destructive optics cleaning [8]. The microscopic mechanisms uncovered through these simulations offer theoretical explanations for plasma cleaning effects observed in macroscopic experiments [1].

Optimization of plasma parameters is crucial for effective cleaning while minimizing damage. Studies evaluating plasma parameters' impact on material removal rate (MRR) and surface roughness in plasma polishing of fused silica have revealed that proper parameter control enables significant improvements in surface quality [5]. The development of medium-pressure plasma polishing (MPPP) processes has demonstrated the potential for achieving material removal rates of 0.11 mm³/min with controlled surface characteristics [6].

Table 4: Optimized Plasma Parameters for Fused Silica Cleaning

| Process Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Cleaning Performance | Optimal Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| RF Power | 20-80 W [6] | Higher power increases reaction rates but may cause damage | 40-60 W (dependent on other parameters) |

| Chamber Pressure | 5-20 mbar [6] | Affects plasma density and mean free path of ions | 10 mbar (balance between density and energy) |

| Gas Composition | O₂, Ar, SF₆ mixtures [5] | Determines chemical vs physical cleaning dominance | O₂/Ar (90:10) for organic removal [6] |

| Process Duration | 45 min to several hours [6] | Longer times increase contaminant removal but risk substrate damage | Time-controlled to endpoint detection |

| Substrate Temperature | Ambient to 300°C | Higher temperatures enhance reaction kinetics | Controlled based on substrate sensitivity |

Low-pressure non-equilibrium plasma technologies represent a cornerstone of modern materials processing, particularly for applications requiring precise surface modification without thermal damage. These systems utilize partially ionized gases sustained at pressures typically between 1 and 1000 Pa, where free electrons achieve high temperatures (1-10 eV) while heavy particles (ions, neutral species) remain near ambient temperature [9] [10]. This thermodynamic non-equilibrium enables efficient dissociation of source gas molecules through electron-impact reactions while maintaining bulk gas temperatures compatible with heat-sensitive materials, including fused silica optics [9]. The fundamental advantage of low-pressure systems lies in their superior plasma uniformity over large volumes and significantly reduced specific power requirements for generating high densities of reactive species compared to atmospheric-pressure alternatives [9]. In the context of fused silica optics cleaning, this translates to predictable, homogeneous surface treatments with minimal risk of thermal stress-induced damage.

The scientific foundation of low-pressure plasma applications rests upon understanding the relationship between discharge parameters, the resulting fluxes of reactive species, and their interaction with material surfaces. As plasma species are generated through inelastic collisions between energetic electrons and source gas molecules, the lack of significant gas-phase loss channels at low pressures enables substantial densities of reactive species to accumulate in the plasma bulk [9]. These species subsequently diffuse to surfaces, where they participate in precisely controlled chemical reactions that facilitate contaminant removal, surface activation, or subtle morphological modifications—all critical processes for achieving ultraclean fused silica optics with optimal laser damage resistance.

Discharge Characteristics and Electrical Properties

Discharge Configuration and Plasma Generation

Low-pressure plasma systems for precision applications typically employ several discharge configurations, each with distinct characteristics and optimal operational domains. Dielectric Barrier Discharges (DBD) utilize at least one dielectric-covered electrode to limit current and prevent arc formation, generating relatively homogeneous plasma sheets suitable for surface treatment [11] [12]. Capacitively Coupled Plasmas (CCP) employ parallel electrodes with radio frequency (typically 13.56 MHz) excitation, establishing oscillating sheaths that efficiently accelerate ions toward electrode surfaces [10]. Inductively Coupled Plasmas (ICP) use time-varying magnetic fields induced by antenna currents to generate high-density plasma with independent control of ion flux and energy, while Microwave Discharges (often at 2.45 GHz) produce even higher electron densities through efficient electron heating via electromagnetic wave energy transfer [10]. Each configuration creates unique combinations of electron energy distributions, plasma densities, and ion flux characteristics that must be matched to specific processing requirements.

The formation and sustainability of low-pressure plasma depend critically on maintaining an appropriate balance between ionization rates and particle loss mechanisms. When sufficient electric field is applied, free electrons gain kinetic energy between collisions and eventually reach thresholds capable of ionizing background gas molecules through inelastic collisions. The resulting electron-ion pairs sustain the discharge when generation rates compensate for losses to surfaces and volume recombination. In low-pressure systems, the reduced collision frequency allows electrons to achieve higher average energies compared to atmospheric pressure counterparts, significantly enhancing dissociation and excitation efficiencies for a given input power [9]. This characteristic makes low-pressure systems particularly energy-efficient for generating the reactive species essential for precision optics cleaning.

Quantitative Discharge Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of discharge characteristics for different low-pressure plasma configurations

| Discharge Type | Typical Frequency | Electron Density (m⁻³) | Electron Temperature (eV) | Ion Energy (eV) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC Glow Discharge | DC - 100 kHz | 10¹⁴ - 10¹⁶ | 1 - 5 | 10 - 500 | Basic research, sputtering |

| Capacitively Coupled Plasma (CCP) | 13.56 MHz - 100 MHz | 10¹⁵ - 10¹⁷ | 1 - 4 | 50 - 1000 | Etching, thin film deposition |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) | 1 - 100 MHz | 10¹⁷ - 10¹⁹ | 2 - 5 | 10 - 500 | High-rate processing, optics cleaning |

| Microwave Discharge | 0.9 - 2.45 GHz | 10¹⁷ - 10¹⁹ | 3 - 8 | 10 - 200 | High-density plasma, species generation |

Table 2: Effect of packing materials on CO₂ discharge characteristics at different powers [11]

| Discharge Power (W) | Average Electric Field (kV/cm) - Empty Tube | Average Electric Field (kV/cm) - SiO₂ Packed | Average Electric Field (kV/cm) - Al₂O₃ Packed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1.32 | 1.40 | 1.55 |

| 12.5 | 1.46 | 1.48 | 1.72 |

| 15 | 1.53 | 1.61 | 1.79 |

| 17.5 | 1.68 | 1.74 | 1.95 |

| 20 | 1.82 | 1.88 | 2.11 |

The electrical characteristics of low-pressure discharges exhibit distinct pressure-dependent behaviors that directly influence processing outcomes. As demonstrated in Table 2, the introduction of dielectric packing materials (such as Al₂O₃ beads) into the discharge region significantly enhances local electric field strength through polarization effects, subsequently increasing electron energy and reaction rates [11]. This field enhancement effect stems from the dielectric constant mismatch between the packing material and plasma, creating localized field intensification at contact points between beads. The resulting increase in electron energy directly enhances dissociation efficiencies for molecular gases, as evidenced by the 12.18% CO₂ conversion rate achieved with Al₂O₃ packing compared to empty tube configurations [11].

The reduced electric field (E/N, where E is the electric field and N is the gas density) serves as a critical parameter determining electron energy distribution functions and subsequent reaction pathways. Experimental measurements confirm that increasing discharge power systematically elevates the reduced electric field across all configurations, with packed-bed reactors exhibiting more pronounced enhancement [11]. This relationship directly influences average electron energy, which typically ranges from 1-5 eV in low-pressure processing plasmas—sufficient to break most chemical bonds while minimizing ion-induced damage. Computational modeling reveals that increased reduced electric field values from approximately 50 Td to 150 Td can elevate mean electron energies from 2.5 eV to 4.5 eV, significantly increasing rate constants for electron-impact dissociation and excitation processes critical for reactive species generation [11].

Reactive Species Generation and Transport Mechanisms

Formation of Reactive Species

The generation of reactive species in low-pressure plasma occurs primarily through electron-impact reactions involving source gas molecules. Energetic electrons (those in the high-energy tail of the electron energy distribution function) collide with neutral molecules, transferring sufficient energy to cause dissociation, excitation, or ionization. For oxygen plasma, dominant pathways include:

- Dissociation: e⁻ + O₂ → O + O + e⁻

- Excitation: e⁻ + O₂ → O₂* + e⁻

- Ionization: e⁻ + O₂ → O₂⁺ + 2e⁻

The dissociation fraction of molecular oxygen in optimized low-pressure systems can exceed 10%, producing atomic oxygen densities approaching 10²² m⁻³ [13]. The actual density achieved depends critically on system geometry, discharge power, pressure, and particularly the surface recombination characteristics of reactor materials. Similar processes occur in other molecular gases, with nitrogen plasma generating N atoms and N₂* excited species, while argon plasma produces metastable Ar* atoms with internal energies of 11.5 eV—sufficient to initiate reactions through Penning processes.

The electron energy distribution function (EEDF) fundamentally determines the efficiency of reactive species generation. In low-pressure discharges, the EEDF often approximates a Maxwellian distribution, with the high-energy tail (>5-10 eV) responsible for most inelastic processes. The rate coefficients for specific reaction channels exhibit strong dependence on mean electron energy, with dissociation thresholds typically around 5-10 eV and ionization thresholds around 12-15 eV [11]. Computational modeling demonstrates that increasing mean electron energy from 2 eV to 4 eV can enhance dissociation rate constants by 2-3 orders of magnitude, highlighting the critical importance of electron energy control for optimizing reactive species production [11].

Transport and Loss Mechanisms

In low-pressure plasmas, the transport of reactive species to surfaces occurs primarily through ambipolar diffusion for ions and neutral diffusion for radicals, with characteristic diffusion lengths determined by reactor geometry and pressure. Unlike atmospheric pressure systems where homogeneous gas-phase reactions dominate loss mechanisms, low-pressure plasmas exhibit significantly longer species lifetimes (up to seconds versus microseconds at atmospheric pressure), with heterogeneous surface reactions representing the predominant loss mechanism [13]. This extended lifetime enables uniform treatment of complex geometries and allows separation of plasma generation and processing regions, as exploited in remote plasma configurations.

The surface loss probability for reactive species varies considerably depending on surface material, temperature, and morphology. For atomic oxygen recombination on silica surfaces, the loss coefficient typically ranges from 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻³, increasing with surface roughness and temperature [13]. Two primary mechanisms govern surface recombination: the Eley-Rideal mechanism, where gas-phase atoms directly recombine with adsorbed atoms, and the Langmuir-Hinshelwood mechanism, involving two adsorbed atoms associating and desorbing as a molecule [13]. The relative contribution of each pathway depends on surface coverage, atom flux, and kinetic energy, with ion bombardment significantly enhancing recombination coefficients through increased surface mobility and defect creation.

Table 3: Characteristics of principal reactive species in oxygen plasma

| Species Type | Examples | Typical Density (m⁻³) | Lifetime | Primary Surface Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radicals (neutral) | O, OH | 10²⁰ - 10²² | Milliseconds - seconds | Chemical etching, functionalization |

| Charged ions | O₂⁺, O⁻ | 10¹⁵ - 10¹⁸ | Microseconds | Sputtering, ion-assisted chemistry |

| Excited species | O₂(a¹Δg), O(¹D) | 10¹⁸ - 10²⁰ | Microseconds - milliseconds | Energy transfer, dissociation |

| Radiation (VUV) | OI (130 nm) | - | Nanoseconds | Photon-stimulated desorption |

Experimental Protocols for Fused Silica Optics Cleaning

Plasma System Configuration and Setup

Protocol 1: System Preparation and Substrate Loading

Vacuum Chamber Preparation: Clean the plasma reactor chamber using isopropyl alcohol followed by deionized water to remove particulate contamination. Perform a preliminary oxygen plasma treatment (100 W, 10 Pa, 10 min) to remove hydrocarbon residues from chamber walls [14].

Substrate Mounting: Mount fused silica optics on a grounded aluminum holder designed to minimize shadowing effects. Ensure electrical contact for surface potential stabilization. The holder should be positioned parallel to the electrode surface at a distance of 30-50 mm to ensure uniform flux distribution [15].

Pressure Stabilization: Evacuate the chamber to base pressure (<10⁻² Pa) using a turbomolecular pumping system. Introduce process gas (typically oxygen or argon-oxygen mixtures) through mass flow controllers to achieve stable operating pressure between 1-50 Pa [14] [15].

Leak Rate Verification: Monitor chamber pressure with gas flow suspended to verify leak integrity. Acceptable leak rates should be <10⁻³ Pa·L/s to prevent atmospheric contamination during processing.

Protocol 2: Plasma Ignition and Parameter Optimization

Impedance Matching: For RF systems, adjust impedance matching network to minimize reflected power (<5% of forward power) at the desired operating conditions [10].

Plasma Ignition: Apply RF power (typically 13.56 MHz) using a stepped power ramp (10 W/s) to prevent transient arcs. Initiate discharge at 50 W and stabilize for 2 minutes before adjusting to final power level [14].

Parameter Optimization: Using optical emission spectroscopy, monitor the 777 nm atomic oxygen and 844 nm atomic argon lines to optimize power and pressure for maximum O radical production. Typical optimized conditions for fused silica cleaning are 100-300 W RF power at 5-20 Pa pressure [13].

Process Stability Verification: Monitor discharge parameters (voltage, current, power) for stability over 5-minute observation period before introducing samples. Variations should not exceed ±5% during this period.

Plasma Treatment and Process Monitoring

Protocol 3: In-situ Plasma Treatment and Diagnostics

Treatment Initiation: Expose fused silica substrates to oxygen plasma using predetermined optimized parameters. Standard conditions: O₂ flow rate 50 sccm, pressure 10 Pa, RF power 200 W, electrode spacing 40 mm [14].

Optical Emission Spectroscopy: Position fiber optic spectrometer to collect plasma emission through quartz viewport. Monitor O (777 nm) and OH (309 nm) line intensities normalized to Ar (750 nm) reference line (when using Ar addition) to track reactive species density stability [11].

Electrical Characterization: Record voltage and current waveforms using high-voltage probe and current monitor. Calculate dissipated power from Q-U Lissajous figures for DBD systems or VI product for RF systems [11].

Temperature Monitoring: Monitor substrate temperature using infrared pyrometer through viewport. Maintain temperature below 150°C to prevent thermal stress in fused silica [14].

Protocol 4: Post-treatment Analysis and Characterization

Venting Procedure: After plasma treatment, shut off RF power and maintain gas flow for 1 minute to flush out reactive species. Gradually vent chamber with dry nitrogen to prevent particulate contamination.

Surface Energy Assessment: Within 30 minutes of removal, measure water contact angle using 2 µL droplets. Successful cleaning typically yields contact angles <10° for fused silica surfaces [15].

XPS Analysis: Perform X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy within 4 hours of treatment to quantify surface carbon contamination. Effective plasma cleaning should reduce carbon content to <5 atomic% [14].

AFM Characterization: Acquire atomic force microscopy images (5×5 µm scan area) to evaluate surface roughness changes. Properly optimized plasma cleaning should not increase RMS roughness beyond 0.5 nm [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for low-pressure plasma studies

| Item | Specification | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Substrates | 25 mm diameter × 5 mm thickness, λ/10 surface accuracy | Primary substrate for cleaning studies | Spectrosil 2000 or equivalent; RMS roughness <0.5 nm |

| Process Gases | Oxygen (5.0 purity), Argon (5.0 purity) | Plasma generation and reactive species source | Additional purification traps recommended for moisture removal |

| Dielectric Packing Materials | Al₂O₃, SiO₂ spheres (1-3 mm diameter) | Electric field enhancement in packed-bed reactors | Dielectric constant >9 for significant field enhancement |

| Langmuir Probe System | Cylindrical tungsten tip, computerized acquisition | Electron temperature and density measurements | Requires RF compensation for non-thermal plasmas |

| Optical Emission Spectrometer | 200-800 nm range, ±0.1 nm resolution | Reactive species monitoring and process control | Focus on O (777 nm), OH (309 nm), CO (391 nm) lines |

| Quartz Crystal Microbalance | 6 MHz AT-cut crystals with deposition monitor | In-situ contamination rate measurement | Requires temperature stabilization for accurate readings |

| XPS Reference Samples | Gold, silver, and copper calibration foils | Surface composition quantification | Storage in inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation |

| Impedance Matching Network | Automatic, 13.56 MHz, 3 kW capacity | RF power coupling optimization | Manual tuning acceptable for fixed-parameter studies |

Molecular Dynamics Insights into Plasma-Surface Interactions

Recent advances in molecular dynamics simulations have provided atomic-scale insights into plasma-surface interactions during fused silica cleaning. Simulations employing the ReaxFF force field reveal that oxygen plasma bombardment disrupts Si-O bonds in fused silica, leading to successive sputtering of silicon and oxygen atoms [14]. The quantity of sputtered atoms demonstrates a linear correlation with irradiation time under constant flux conditions, with significant damage onset observed at particle energies exceeding 33 eV [14]. This threshold energy represents a critical parameter for process optimization, as it defines the boundary between contamination removal and substrate damage.

The evolution of surface morphology during plasma treatment follows distinct patterns depending on incident particle energy and flux. At optimal cleaning conditions (10-30 eV), simulations show selective removal of surface contaminants and minimal substrate damage, while higher energies (>33 eV) produce pit defects and increased surface roughness through preferential sputtering of specific lattice sites [14]. Temperature emerges as a crucial factor influencing surface damage, with elevated temperatures (≥400 K) significantly enhancing adatom mobility and surface reorganization rates. These insights enable prediction of process windows that maximize contaminant removal while preserving optical surface quality.

Process Optimization and Damage Mitigation Strategies

Successful plasma cleaning of fused silica optics requires careful balancing between cleaning efficiency and surface preservation. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that neutral oxygen atoms with kinetic energies of approximately 1-10 eV primarily drive surface functionalization and etching, while higher energies (>33 eV) cause significant lattice damage [14] [13]. This energy threshold provides crucial guidance for process parameter selection, particularly in specifying bias voltages and plasma potentials. Experimental validation confirms that maintaining ion energies below 30 eV during cleaning effectively removes hydrocarbon contaminants while limiting surface roughness increase to <0.2 nm RMS [14].

The surface temperature during plasma treatment significantly influences both cleaning kinetics and damage accumulation. Elevated temperatures (up to 150°C) enhance the diffusion and desorption of reaction products, reducing processing time by approximately 30% compared to room temperature operations [14]. However, temperatures exceeding 200°C can accelerate defect migration and aggregation, potentially compromising laser-induced damage threshold. Advanced strategies employ pulsed plasma techniques with duty cycles of 10-50% to manage thermal load while maintaining high radical fluxes, effectively decoupling energy input from species generation.

Table 5: Optimized parameters for damage-free plasma cleaning of fused silica optics

| Process Parameter | Optimal Range | Effect on Cleaning | Effect on Surface Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Pressure | 5-20 Pa | Higher pressure increases radical density | Lower pressure reduces ion energy and damage |

| RF Power Density | 0.5-1.5 W/cm² | Higher power increases cleaning rate | Excessive power causes heating and defects |

| Oxygen Concentration | 80-100% | Higher O₂ increases radical density | Ar dilution reduces chemical etching |

| Process Temperature | 100-150°C | Higher temperature enhances kinetics | Excessive temperature causes thermal stress |

| Treatment Time | 5-30 minutes | Longer exposure improves cleaning | Over-treatment causes surface roughness |

| Ion Energy | <30 eV | Sufficient for contaminant removal | Minimizes lattice displacement damage |

The implementation of real-time monitoring and control represents the most effective strategy for process optimization. Optical emission spectroscopy tracking of the O (777 nm)/Ar (750 nm) ratio provides direct correlation with atomic oxygen density, enabling immediate adjustment of power and pressure to maintain optimal cleaning conditions [11]. Similarly, in-situ ellipsometry can monitor surface layer thickness changes with sub-nanometer resolution, allowing process termination once contaminant removal is complete. These advanced control strategies reduce processing variability by up to 60% compared to fixed-parameter approaches, ensuring reproducible surface conditions critical for high-performance optical applications.

Radical-Driven Reaction Pathways for Organic Contaminant Removal

In the context of a broader thesis on low-pressure plasma cleaning of fused silica optics, understanding the radical-driven reaction pathways for removing organic contaminants is paramount. During prolonged service in vacuum-based intense laser systems, the surface chemical coatings of large-aperture optical components inevitably suffer from organic contamination, leading to irreversible damage and rapid degradation of optical performance under laser irradiation [1]. This application note details the protocols and mechanistic insights into how low-pressure plasma, specifically oxygen-based plasma, utilizes radical-driven pathways to remove organic contaminants from critical optical surfaces.

The core mechanism involves the ionization of a working gas, such as oxygen or argon, via low-pressure radio-frequency (RF) capacitive coupling discharge. This process generates a large-area, uniform, diffuse plasma. The reactive species within this plasma, including radicals, ions, and electrons, then interact with the organic contaminants [1] [9]. The primary removal process is chemical decomposition driven by reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can be significantly enhanced by the kinetic energy of plasma particles. This kinetically assisted chemical removal leads to the stepwise decomposition of organic molecules into small, volatile molecular groups that desorb from the surface [16].

Key Radical Reaction Pathways and Quantitative Analysis

Dominant Reaction Pathways

Reactive molecular dynamics (ReaxFF MD) simulations have been instrumental in elucidating the atomic-scale reaction mechanisms. Using dibutyl phthalate (DBP) as a representative model pollutant, two dominant radical-driven reaction pathways have been identified [16]:

- Butyl Chain Cleavage: Radicals, particularly atomic oxygen, attack the alkoxy groups of the molecule, leading to the scission of C-O bonds and the subsequent breakdown of the carbon chains.

- Benzene Ring Cleavage: Energetic radicals open and fragment the aromatic ring structure, ultimately leading to the complete mineralization of the molecule.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential nature of these radical-driven pathways for a model organic contaminant.

Quantitative Efficacy of Kinetic Enhancement

While the core mechanism is chemical, the initial kinetic energy of the reactive oxygen species is a critical promoter. It enhances the transport and penetration of radicals into the contaminant layer and facilitates energy transfer to overcome reaction energy barriers [16]. The following table summarizes the quantitative enhancement of contaminant decomposition due to the kinetic energy of plasma species, as revealed by ReaxFF MD simulations.

Table 1: Quantitative Effect of Kinetic Energy on Contaminant Decomposition (ReaxFF MD Data)

| Initial Kinetic Energy of ROS | DBP Residue Ratio | Enhancement of Decomposition Rate | Key Activated Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0083 eV | High | Baseline (1x) | Limited thermal reactions |

| 75 eV | Low | Up to 1310% increase | C-O cleavage, C-C fission, ring opening |

Experimental Protocol for Plasma Cleaning of Fused Silica Optics

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table lists the key materials, reagents, and equipment required for the experimental investigation of low-pressure plasma cleaning of optical components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Plasma Cleaning Studies

| Item Name | Function/Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Substrates | Optical component material; can be uncoated, or with sol-gel SiO₂ chemical coatings [1] [17]. | Primary sample for cleaning efficacy and damage studies. |

| Dibutyl Phthalate (DBP) | Representative model organic contaminant [16]. | Used in simulation and experimental studies to standardize contamination. |

| Oxygen (O₂) Gas | Primary process gas; source of reactive oxygen species (O, O₂⁺) [1] [16]. | Drives chemical decomposition of organic contaminants. |

| Argon (Ar) Gas | Inert process gas; can be used for physical sputtering or in gas mixtures [1]. | Used to study physical bombardment effects. |

| Low-Pressure RF Plasma System | Capacitively coupled plasma reactor with vacuum pump, gas flow control, and RF power generator (e.g., 13.56 MHz) [1]. | Core apparatus for generating non-equilibrium plasma. |

| Langmuir Probe | Diagnostic tool for measuring plasma parameters (plasma potential, ion density, electron temperature) [1]. | Characterizing plasma discharge properties. |

| Emission Spectrometer | Diagnostic tool for identifying types of reactive particles excited in the plasma [1]. | Monitoring active radical species in real-time. |

Step-by-Step Workflow for Plasma Cleaning and Analysis

The following diagram outlines the integrated experimental and simulation workflow for developing and optimizing a plasma cleaning process.

Protocol Steps:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare chemical-coated fused silica samples using a dip-coating method with a sol-gel SiO₂ solution designed for 355 nm laser applications [1].

- Contaminate samples with a representative organic contaminant (e.g., a calibrated amount of DBP or exposure to vacuum outgassing compounds) to create a standardized test surface [16] [17].

Plasma System Setup & Parameterization:

In-situ Plasma Diagnostics (Optional but Recommended):

- Use a Langmuir probe to measure fundamental plasma parameters such as plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature. This establishes a quantitative relationship between input power and the resulting plasma characteristics [1].

- Employ Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES) to identify the specific reactive oxygen species (e.g., atomic oxygen radicals) present in the plasma, confirming the activation of radical-driven pathways [1].

Ex-situ Surface and Performance Analysis:

- Water Contact Angle: Measure the contact angle before and after cleaning. A significant decrease indicates the removal of hydrophobic organic contaminants and increased surface hydrophilicity [17].

- Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM): Image the surface topography to directly assess the removal of contaminants and, critically, to check for any nano-scale roughening or pit formation due to over-cleaning [14] [17].

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): Analyze the surface chemical composition to confirm the reduction of carbon content and the chemical state of the fused silica surface post-cleaning [1].

- Optical Transmittance: Measure the transmittance of the optic at the target wavelength (e.g., 355 nm). Successful cleaning should restore transmittance to near-baseline levels [1] [17].

- Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT): Test the LIDT to ensure that the cleaning process not only restores optical performance but also maintains or improves the component's resistance to laser damage [17].

Critical Considerations for Non-Destructive Cleaning

A paramount concern in plasma cleaning is avoiding damage to the fused silica substrate. Molecular dynamics simulations reveal that once organic contaminants are fully removed, continued plasma irradiation (over-cleaning) leads to the formation of nano-defects [14].

- Damage Mechanism: Oxygen plasma bombardment disrupts Si-O bonds in the fused silica lattice, leading to the sputtering of silicon and oxygen atoms and the formation of pit defects. Significant surface damage is observed when the energy of bombarding species exceeds a critical threshold (e.g., ~33 eV) [14].

- Process Window Optimization: The cleaning process must operate within a window defined by minimum cleaning time (for complete contaminant removal) and maximum cleaning time (before onset of substrate damage). Parameters like discharge power and process gas pressure directly influence the aggressiveness of the plasma and must be carefully tuned to this window [1] [14].

This application note establishes that the removal of organic contaminants from fused silica optics via low-pressure plasma is predominantly governed by radical-driven chemical reactions, with physical kinetic energy acting as a crucial enhancer. The integration of experimental diagnostics with ReaxFF molecular dynamics simulations provides a powerful methodology to decode the atomic-scale pathways and optimize process parameters. By adhering to the detailed protocols and recognizing the critical balance between cleaning efficacy and substrate preservation, researchers can implement a robust, non-destructive cleaning strategy. This ensures the longevity and performance stability of high-value optical components in intense laser systems.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Plasma-Surface Interactions

Application Note: Nano-Defect Formation on Fused Silica Optics

Low-pressure plasma cleaning has emerged as a critical technology for maintaining the ultra-high cleanliness requirements of fused silica optics in precision laser systems, particularly within vacuum environments [8]. While effectively removing organic contaminants, prolonged plasma exposure can induce nanoscale damage on the optically active surfaces, ultimately degrading performance [8]. This application note examines the atomic-scale mechanisms of plasma-induced nano-defect formation on fused silica surfaces using Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. The insights gained are foundational for developing non-destructive cleaning protocols within the broader context of fused silica optics preservation.

Quantitative Damage Parameters from MD Simulations

MD simulations reveal critical parameters and thresholds governing surface damage during oxygen plasma irradiation of fused silica. The tables below summarize key quantitative findings.

Table 1: Plasma Energy Parameters and Damage Effects

| Plasma Energy (eV) | Observed Effect on Fused Silica Surface |

|---|---|

| ~3 (Electron Temperature) | Typical electron temperature in RF plasma; sheath voltage can reach hundreds of volts [8]. |

| <33 eV | Region below significant damage threshold [8]. |

| >33 eV | Onset of significant surface damage; bond disruption and atomic sputtering occur [8]. |

| 74 eV (Case Study) | Observable pit defect formation and successive sputtering of silicon-oxygen atoms [8]. |

Table 2: Temporal Evolution of Surface Damage

| Irradiation Time | Damage Depth | Atomic Sputtering Observation |

|---|---|---|

| Initial 10 ps | Damage initiates | Linear increase in sputtered atoms; Si:O sputtering ratio ~ 1.5:1 [8]. |

| 100 ps | ~17.03 Å | Damage depth reaches a plateau despite continued irradiation [8]. |

| Post-irradiation | Morphology stable | Sputtered atoms aggregate into molecular clusters in the vacuum [8]. |

Key Findings and Mechanisms

The interaction between oxygen plasma and fused silica is characterized by two primary mechanisms:

- Physical Sputtering: Energetic ions (e.g., Ar⁺) accelerated from the plasma bombard the surface, transferring kinetic energy to lattice atoms. When this energy exceeds the surface binding energy, atoms are physically ejected [18].

- Chemical Reaction & Bond Disruption: Reactive species, particularly oxygen radicals, disrupt the Si-O network bonds of fused silica. This leads to the successive sputtering of silicon and oxygen atoms [8].

Simulations show that temperature is a crucial factor affecting the extent of surface damage [8]. Furthermore, neutral oxygen atoms play a key role in forming distinctive pit defects and interface damage patterns [8]. After the initial damage layer forms, subsequent oxygen ions can bombard previously deposited ions, creating a protective layer that causes the damage depth to plateau over time [8].

Protocol: Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Plasma-Surface Interaction

Simulation Setup and Workflow

This protocol details the procedure for establishing and running an MD simulation to investigate low-temperature oxygen plasma interactions with a fused silica surface.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Materials

| Item Name | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Fused Silica Substrate | Amorphous SiO₂ structure representing the optical component surface [8]. |

| Oxygen Plasma Species | Source of neutral oxygen atoms (O) and ions (O⁺) for bombardment [8]. |

| ReaxFF Force Field | A reactive force field used to describe bond breaking and formation during plasma-surface interactions [8] [1]. |

| LAMMPS / Similar MD Engine | Software to perform the molecular dynamics calculations. |

| Visualization Software (e.g., OVITO) | For analyzing simulation trajectories, defect identification, and rendering atomic configurations. |

Figure 1: MD Simulation Workflow for Plasma-Surface Interaction.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Model Construction

- Build an atomic model of a fused silica substrate. The model should be large enough to minimize periodic boundary effects and have a defined surface plane.

- Create a simulation box that includes a vacuum region above the substrate surface to accommodate plasma species and sputtered atoms [8].

Force Field Selection and Validation

- Employ a reactive force field (ReaxFF) parameterized for Si/O systems. This force field is critical as it allows for dynamic bond breaking and formation during the simulation [8] [1].

- Ensure the force field can accurately reproduce the bonding structure and known material properties of fused silica.

System Equilibration

- Perform energy minimization of the initial structure to remove any unrealistic atomic clashes.

- Equilibrate the fused silica substrate at the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) using an NVT (constant Number, Volume, and Temperature) ensemble for a sufficient duration (e.g., tens of picoseconds) to stabilize the system.

Plasma Bombardment Phase

- Introduce plasma particles (e.g., neutral oxygen atoms) one by one or in small groups toward the substrate surface.

- Set the kinetic energy of the incident particles based on the parameter under investigation (e.g., 33 eV, 74 eV). The direction can be perpendicular or follow a defined distribution [8].

- The flux is controlled by the time interval between particle injections. A typical simulation might involve 10-100 ps of continuous plasma irradiation [8].

- Use an NVE (constant Number, Volume, and Energy) ensemble during this bombardment phase to correctly model energy transfer.

Post-Irradiation Relaxation

- After ceasing plasma particle injection, allow the system to relax for a further period (e.g., 90 ps) under NVT conditions. This allows the system to reach a new stable state and for sputtered atoms to form clusters [8].

Data Collection and Analysis

- Trajectory Output: Save atomic coordinates and velocities at regular intervals for post-processing.

- Sputtering Yield: Count the number of silicon and oxygen atoms that are permanently ejected from the substrate surface. Track the O:Si ratio of sputtered atoms [8].

- Damage Depth Analysis: Calculate the erosion depth of the original surface over time. Monitor the injection depth of oxygen atoms into the substrate [8].

- Defect Identification: Use coordination number analysis to identify under-coordinated atoms and visualize pit formation or surface roughening.

Critical Parameters for Experimental Correlation

For MD simulations to effectively guide macroscopic experiments, specific parameters must be aligned.

Figure 2: Correlation Framework Between Simulation and Experiment.

- Particle Energy: The kinetic energy of ions/atoms in the simulation (e.g., 33 eV, 74 eV) must correspond to the plasma sheath potential in experimental RF plasmas, which can reach hundreds of volts [8].

- Particle Flux: The rate of particle injection in the simulation should be calibrated, where possible, to the ion flux density measured experimentally via Langmuir probes [1].

- Temperature Control: The substrate temperature in the simulation is a direct input and a crucial factor affecting surface damage, which must be controlled and matched to experimental conditions [8].

Spatial Distribution of Plasma Discharge Characteristics in Capacitive-Coupling Systems

In the field of low-pressure plasma cleaning for fused silica optics, mastering the spatial distribution of plasma discharge characteristics is paramount for achieving uniform and efficient removal of organic contaminants. Capacitively coupled plasma (CCP) systems, typically energized by radio-frequency (RF) power sources, are widely employed for this purpose due to their ability to generate large-area, uniform plasma under low-pressure conditions [1] [19]. The control of this spatial uniformity is critical, as non-uniform plasma distributions can lead to uneven cleaning of large-aperture optical components, directly compromising their laser damage threshold and overall optical performance [1]. This application note provides a detailed experimental framework for characterizing and optimizing the spatial distribution of plasma discharge parameters, enabling researchers to achieve reproducible and effective cleaning of fused silica optics.

Key Plasma Parameters and Their Spatial Relationship

The spatial distribution of capacitively coupled plasma is governed by several interdependent parameters. Understanding these relationships is essential for experimental design and interpretation.

Table 1: Key Plasma Parameters and Their Interdependencies in Capacitive-Coupling Systems

| Parameter | Spatial Influence | Effect on Plasma Uniformity | Typical Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Excitation Frequency | Determines electromagnetic wavelength on electrodes; affects standing wave formation [20]. | Higher frequencies (e.g., 150 MHz) promote significant standing wave effects and voltage non-uniformity compared to 13.56 MHz [20]. | Impedance analyzer, Network analyzer |

| Discharge Power | Influences electron temperature, ion density, and plasma potential [1]. | Optimal power range ensures stable discharge without constriction; affects density profile [1]. | Langmuir probe, IV probe |

| Gas Pressure | Affects mean free path and ionization collision rate [1]. | Lower pressures often improve uniformity but require optimal power coupling [1]. | Capacitance manometer, Barometer |

| Electrode Geometry & Size | Larger electrodes (relative to wavelength) exacerbate standing wave effects [20]. | Center-to-edge voltage variations occur; 1m electrode at 150 MHz shows >50% voltage variation [20]. | Caliper, Design specifications |

| Plasma Impedance (Zp) | Nonlinear characteristic; varies with applied power and geometry [20]. | Uniformity is achieved when impedance is constant across the electrode area [20]. | Langmuir probe, IV waveform analysis |

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Distribution Analysis

Langmuir Probe Characterization of Plasma Parameters

Objective: To measure the spatial variations of plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature across the electrode area.

Materials:

- Low-pressure capacitive-coupled plasma reactor with RF source (typically 13.56 MHz or higher)

- Langmuir probe system with positioning mechanism

- Data acquisition system

- Vacuum pump system and pressure gauge

- High-precision XYZ probe manipulator

- Process gases (Ar, O₂)

Procedure:

- System Setup: Establish a stable low-pressure plasma discharge using Ar or O₂ as the working gas. Maintain constant pressure (e.g., 10-100 mTorr) and gas flow rate.

- Probe Calibration: Calibrate the Langmuir probe using a standard plasma source prior to measurements.

- Spatial Mapping: Program the XYZ manipulator to move the probe to predetermined positions across the plasma region, particularly between the electrodes.

- Data Collection: At each position, obtain current-voltage (I-V) characteristics by sweeping the probe voltage.

- Parameter Extraction: Analyze the I-V characteristics to derive local plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature using appropriate theory (e.g., Orbital Motion Limited theory).

- Data Visualization: Create 2D contour maps of each parameter to visualize spatial distribution.

Note: The probe should be carefully cleaned before and after experiments to avoid contamination of measurements.

Voltage Distribution Mapping via Transmission Line Modeling (TLM)

Objective: To computationally determine the voltage distribution across large-area electrodes, identifying standing wave effects.

Materials:

- Computational electromagnetics software (e.g., COMSOL Multiphysics, SEMCAD)

- Electrode material properties (conductivity, magnetic permeability)

- Experimentally measured plasma impedance data

Procedure:

- Model Construction: Create a finite element model of the electrode system, including upper electrode, lower grounded electrode, and plasma region.

- Parameter Definition:

- Simulation Setup: Apply RF excitation at specified frequency (e.g., 13.56 MHz or 150 MHz) at chosen power application point(s).

- Boundary Conditions: Set electrode edges as open-circuit or capacitive termination based on actual reactor design.

- Solution: Solve the 2D wave equation using the finite difference method to compute voltage amplitude at each node across the electrode surface.

- Analysis: Identify regions of maximum and minimum voltage amplitude, quantifying center-to-edge variation.

Table 2: Exemplary Voltage Distribution Data for 1m Electrode (Relative to Center Voltage)

| Position from Center (m) | 13.56 MHz Excitation | 150 MHz Excitation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 0.1 | 0.99 | 0.95 |

| 0.2 | 0.98 | 0.82 |

| 0.3 | 0.96 | 0.65 |

| 0.4 | 0.93 | 0.48 |

| 0.5 | 0.90 | 0.35 |

Data adapted from calculations showing standing wave effect severity increases with frequency [20].

Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES) for Reactive Species Distribution

Objective: To map the spatial distribution of key reactive species (e.g., oxygen radicals) responsible for organic contaminant removal.

Materials:

- Spectrometer with optical fiber

- XYZ positioning system for fiber optic collector

- Calibrated light source for wavelength intensity calibration

Procedure:

- Plasma Ignition: Generate oxygen-based plasma at specified operating conditions.

- Spectral Acquisition: Position the optical fiber at various locations in the plasma chamber and collect emission spectra.

- Species Identification: Identify characteristic emission lines for key species (e.g., atomic oxygen at 777 nm).

- Intensity Mapping: Create spatial maps of emission intensity for each species, proportional to their concentration.

- Correlation: Correlate species distribution with cleaning efficacy measured via transmittance recovery of contaminated optics.

Visualization of Experimental Workflow and Plasma-Surface Interactions

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Plasma Discharge Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Substrates | Sample material for contamination and cleaning studies | High-purity, often with sol-gel SiO₂ chemical coatings at 355 nm wavelength [1] |

| Process Gases (Ar, O₂) | Plasma generation and reactive species production | High-purity grade (99.99%+); O₂ enables radical-driven organic contaminant removal [1] |

| Langmuir Probe System | Spatial measurement of plasma parameters (potential, density, temperature) | Requires precise positioning system and appropriate data acquisition software [1] |

| RF Power Supply & Matching Network | Plasma generation and impedance matching | Typically 13.56 MHz industrial standard; matching network minimizes reflected power [1] [19] |

| Optical Emission Spectrometer | Identification and spatial mapping of reactive species | Wavelength range 200-800 nm; fiber optic coupling for spatial scanning [1] |

| Vacuum System | Maintaining low-pressure environment for plasma | Base pressure ~10⁻⁶ Torr; pressure control during gas flow [1] |

| Contamination Sources | Simulating real-world organic contamination on optics | Controlled deposition of hydrocarbon-based contaminants [1] |

Achieving uniform spatial distribution of plasma discharge characteristics is fundamental to the success of low-pressure plasma cleaning processes for fused silica optics. The experimental protocols detailed in this application note—encompassing Langmuir probe diagnostics, transmission line modeling of voltage distribution, and optical emission spectroscopy—provide researchers with a comprehensive methodology for characterizing and optimizing capacitive-coupled plasma systems. The correlation between these plasma parameters and cleaning effectiveness, particularly the restoration of optical transmittance and laser damage threshold, enables the development of highly efficient, reproducible cleaning processes essential for maintaining the performance of high-power laser systems.

Implementing Plasma Cleaning: Process Parameters and Practical Applications

RF Capacitive-Coupling Discharge Systems for Optical Component Cleaning

In intense laser systems, such as those used in inertial confinement fusion and fundamental scientific research, the performance and longevity of large-aperture optical components are critically limited by organic contamination. During prolonged operation in vacuum environments, these surfaces inevitably accumulate hydrocarbon-based contaminants. Under intense laser irradiation, these contaminants ablate or decompose, generating stray light that damages delicate chemical coatings and reduces the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) of optical components by approximately 60% [1]. This degradation severely limits the operational efficiency and output capability of the entire laser facility.

Low-pressure plasma cleaning technology, specifically utilizing Radio-Frequency (RF) capacitive-coupling discharge, has emerged as a superior solution for addressing this challenge. This technology efficiently generates a large-area, uniform, diffuse plasma that can remove organic contaminants without causing secondary contamination or damage to sensitive optical coatings. Unlike wet cleaning methods or other dry cleaning techniques, RF plasma cleaning can be performed in situ without disassembling precision optical components, making it particularly valuable for large-aperture optics in complex laser systems [1] [21].

This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing RF capacitive-coupling discharge systems, specifically framed within research on low-pressure plasma cleaning of fused silica optics.

Fundamental Principles

Plasma Generation via RF Capacitive Coupling

In RF capacitive-coupling discharge systems, electrical energy is transferred to a low-pressure gas through capacitive coupling at radio frequencies (typically in the kHz to MHz range). This energy transfer ionizes the gas molecules, creating a plasma containing reactive species including ions, electrons, radicals, and excited molecules [1].

The capacitive coupling mechanism involves two parallel electrodes forming a capacitor, with the optical component and processing chamber acting as the dielectric medium. When RF power is applied, oscillating electric fields accelerate free electrons, which then collide with neutral gas molecules, initiating and sustaining the plasma through ionization processes.

Contaminant Removal Mechanisms

The removal of organic contaminants occurs through two primary mechanisms:

- Chemical Reaction: Reactive species in the plasma (particularly oxygen radicals in an oxygen-based plasma) react with hydrocarbon contaminants, breaking them down into volatile compounds (e.g., CO₂, H₂O) that are evacuated by the vacuum system [1].

- Physical Sputtering: Energetic ions from the plasma bombard the surface, physically dislodging contaminant molecules through momentum transfer. The randomly directed ion bombardment under relatively low pressure and temperature conditions enables efficient yet non-destructive cleaning [1].

Reactive molecular dynamics simulations have revealed that these processes occur on nanosecond timescales at atomic spatial scales, involving complex reaction pathways between plasma species and organic contaminants [1].

Experimental Protocols

System Configuration and Setup

Essential Components

The experimental setup for low-pressure plasma cleaning requires the following core subsystems:

- Vacuum Chamber: Constructed of stainless steel with appropriate electrical feedthroughs and viewports.

- RF Power Supply and Matching Network: Typically operating at 13.56 MHz industry standard frequency with impedance matching to maximize power transfer.

- Capacitive Electrodes: Parallel plates within the vacuum chamber, often with the sample placed on the grounded electrode.

- Vacuum System: Comprising roughing and turbo-molecular pumps to achieve base pressure of 10⁻² to 10⁻³ mbar.

- Gas Delivery System: Mass flow controllers for precise regulation of process gases (oxygen, argon, or mixtures).

- Diagnostic Instruments: Langmuir probe, optical emission spectrometer, and process monitors.

Sample Preparation Protocol

- Substrate Cleaning: Begin with fused silica substrates cleaned using standard solvent procedures (isopropanol followed by acetone in ultrasonic bath).

- Chemical Coating Application: Apply sol-gel SiO₂ chemical coatings using dip-coating methodology:

- Submerge three-quarters of the substrate height in coating sol for 2 minutes to ensure full contact.

- Withdraw at constant speed of 85 mm/min using precision pull-coating apparatus [1].

- Perform post-treatment with ammonia and hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) in sealed container for 24 hours to enhance coating stability [1].

- Contamination Procedure: Artificially contaminate samples in controlled vacuum environment to simulate operational conditions of intense laser systems.

Plasma Characterization Methods

Langmuir Probe Analysis

Objective: To determine fundamental plasma parameters including plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature under varying discharge conditions.

Procedure:

- Insert Langmuir probe into plasma discharge region at predetermined positions.

- Sweep probe voltage from negative to positive bias relative to ground while measuring current.

- Record current-voltage (I-V) characteristics at multiple locations within the plasma.

- Analyze I-V curves using appropriate theory to extract:

- Electron temperature from the exponential region of the electron retardation current

- Ion density from the ion saturation current region

- Plasma potential from the point where the second derivative of the I-V curve is zero

- Repeat measurements across variations in discharge power (50-300 W) and gas pressure (0.1-1.0 mbar).

Optical Emission Spectroscopy

Objective: To identify reactive species present in the plasma and correlate their presence with cleaning effectiveness.

Procedure:

- Couple optical fiber to viewport on vacuum chamber with direct line-of-sight to plasma region.

- Connect fiber to spectrometer with appropriate wavelength range (200-800 nm).

- Acquire emission spectra with integration times sufficient for adequate signal-to-noise.

- Identify characteristic emission lines for:

- Oxygen plasma: Atomic oxygen (777 nm, 844 nm), O₂⁺ bands, excited molecular states

- Argon plasma: Ar I lines (750 nm, 811 nm)

- Correlate emission intensities with process parameters and cleaning performance.

Cleaning Effectiveness Evaluation

Surface Cleanliness Assessment

Water Contact Angle Measurements:

- Place cleaned optical component on level stage of contact angle goniometer.

- Dispense 2-5 µL deionized water droplet onto surface using precision syringe.

- Capture image of droplet profile immediately after deposition.

- Measure contact angle using sessile drop method.

- Compare pre-cleaning and post-cleaning values, with lower angles indicating higher cleanliness and hydrophilicity [21].

Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM):

- Mount sample on AFM specimen stage.

- Scan surface areas of 5×5 µm to 20×20 µm using tapping mode.

- Acquire height and phase images with resolution sufficient to resolve nanoscale features.

- Calculate surface roughness parameters (Ra, Rq) from height data.

- Compare topography before and after cleaning to verify contaminant removal without damage to chemical coatings [21].

Optical Performance Metrics

Transmittance Measurements:

- Place sample in UV-Vis spectrophotometer with appropriate beam diameter.

- Measure transmittance across wavelength range 300-800 nm, with particular attention to operational wavelength (e.g., 355 nm for intense laser systems).

- Compare to baseline measurements of uncontaminated samples.

- Establish quantitative relationship between number of organic functional groups and transmittance values [1].

Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) Testing:

- Place sample in controlled test chamber with capability for in situ damage monitoring.

- Irradiate multiple sites with laser pulses at varying fluence levels (R-on-1 or S-on-1 methodology).

- Monitor for damage events using scattered light detection or online microscopy.

- Calculate damage probability curve and extract LIDT value (typically at 0% damage probability).

- Compare LIDT before and after cleaning to quantify performance recovery [21].

Quantitative Data and Process Optimization

Plasma Parameters Under Varied Conditions

Table 1: Plasma characteristics as function of discharge power and pressure in oxygen-based RF capacitive discharge

| Discharge Power (W) | Gas Pressure (mbar) | Plasma Potential (V) | Ion Density (cm⁻³) | Electron Temperature (eV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.2 | 18.5 | 8.7×10⁹ | 3.2 |

| 100 | 0.2 | 22.1 | 1.5×10¹⁰ | 2.9 |

| 150 | 0.2 | 25.8 | 2.3×10¹⁰ | 2.7 |

| 200 | 0.2 | 28.3 | 3.1×10¹⁰ | 2.5 |

| 100 | 0.1 | 24.5 | 9.8×10⁹ | 3.3 |

| 100 | 0.3 | 20.2 | 1.8×10¹⁰ | 2.6 |

| 100 | 0.5 | 18.7 | 2.1×10¹⁰ | 2.3 |

Cleaning Performance Metrics

Table 2: Optical component performance recovery after low-pressure plasma cleaning

| Sample Condition | Water Contact Angle (°) | Transmittance at 355 nm (%) | LIDT (J/cm²) | Surface Roughness Ra (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uncontaminated Baseline | 25 | 99.8 | 25 | 0.55 |

| Contaminated | 82 | 95.3 | 10 | 1.09 |

| After Plasma Cleaning | 28 | 99.5 | 24 | 0.58 |

| Percentage Recovery | 96% | 99.7% | 96% | 95% |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for plasma cleaning research

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sol-gel SiO₂ Coating Sol | Application of chemical coatings on fused silica substrates | Particle size 29 nm; optimized for 355 nm wavelength [1] |

| Hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) | Post-treatment of chemical coatings to enhance stability | Used in vapor phase treatment for 24 hours in sealed container [1] |

| High-Purity Oxygen (O₂) | Primary process gas for organic contaminant removal | Generates oxygen radicals for chemical breakdown of hydrocarbons [1] |

| High-Purity Argon (Ar) | Process gas for physical sputtering or as carrier gas in mixtures | Enables ion bombardment mechanism; sometimes mixed with oxygen [1] |

| Fused Silica Substrates | Base material for optical components in intense laser systems | High LIDT requirement; various sizes including large-aperture formats [21] |

| Dip-Coating Apparatus | Application of uniform chemical coatings on substrate surfaces | Constant pull speed of 85 mm/min; precision immersion mechanism [1] |

Visualization of Processes and Workflows

Experimental Workflow for Plasma Cleaning Research

Plasma-Contaminant Interaction Mechanisms

RF capacitive-coupling discharge systems provide an effective, controllable, and non-destructive method for removing organic contaminants from precision optical components used in intense laser systems. The technology successfully restores the optical performance of contaminated components, with demonstrated recovery of approximately 99.7% of original transmittance and 96% of laser-induced damage threshold [21].

The optimal cleaning efficiency is achieved through careful control of discharge parameters, particularly power and pressure, which directly influence the plasma characteristics and consequent cleaning mechanisms. The combination of experimental diagnostics with molecular dynamics simulations provides comprehensive insights into the fundamental processes occurring at the atomic scale during plasma cleaning [1].

For researchers pursuing advanced studies in this field, future work should focus on refining process parameters for specific coating types, investigating long-term effects of repeated cleaning cycles, and developing real-time monitoring techniques for process control. The integration of these advanced plasma cleaning protocols will contribute significantly to enhancing the performance and longevity of optical systems in demanding scientific and industrial applications.

Within the broader research on low-pressure plasma cleaning of fused silica optics, the precise optimization of core process parameters is critical for achieving effective contaminant removal while preserving the optical substrate's integrity. Discharge power, gas pressure, and treatment duration form a interconnected set of variables that directly control the plasma's physical and chemical properties, thereby dictating both cleaning efficiency and potential surface damage [1] [8]. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers in systematically optimizing these parameters, framed within the context of advancing non-destructive, high-performance cleaning techniques for intense laser systems and other high-precision optical applications [21].

Parameter Effects and Quantitative Relationships

The core parameters influence the plasma cleaning process through distinct yet interconnected mechanisms. The following table summarizes the quantitative and qualitative effects of varying these key parameters, synthesizing findings from experimental and simulation studies [1] [22] [8].

Table 1: Effects of Core Plasma Cleaning Parameters on Process Outcomes

| Parameter | Key Effects and Quantitative Relationships |

|---|---|

| Discharge Power | - Ion Density: Increases linearly with rising RF power, enhancing the flux of reactive species [1].- Cleaning Rate: Positively correlated with power, but requires optimization to balance efficiency against the risk of surface damage from high-energy ion bombardment [1] [8].- Electron Temperature: Moderately increases with power, affecting the excitation of reactive species [1]. |

| Gas Pressure | - Plasma Uniformity: Lower pressures (e.g., in the medium-pressure range of 11.6 mbar) promote diffuse, uniform plasmas, which are crucial for uniform cleaning of large apertures [22].- Ion Energy vs. Flux: Lower pressure increases mean free path, leading to higher ion bombardment energy, while higher pressure increases radical density and chemical etching contribution [1] [8].- Process Window: A medium-pressure regime can balance chemical vaporization and minimize damaging physical ion sputtering [22]. |

| Treatment Duration | - Contaminant Removal: Cleaning effectiveness increases with time until organic layers are fully removed [21].- Over-cleaning Risk: Prolonged exposure after contaminant removal leads to nano-defect formation on the fused silica substrate, degrading optical performance. The damage depth increases with time before plateauing [8].- Linear Sputtering: Molecular dynamics simulations show the quantity of sputtered Si atoms has a linear correlation with irradiation time [8]. |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Optimization

This section outlines detailed methodologies for conducting experiments to establish the optimal windows for discharge power, gas pressure, and treatment duration.

Protocol: Systematic Evaluation of Discharge Power and Gas Pressure

Objective: To determine the combined effect of discharge power and gas pressure on plasma characteristics and cleaning efficacy.

Materials:

- Low-pressure plasma reactor with RF source (e.g., 13.56 MHz or 40.68 MHz)

- Langmuir probe system

- Optical Emission Spectrometer (OES)

- Fused silica samples with standardized organic contamination

- Goniometer for water contact angle measurements

- Spectrophotometer for transmittance measurements

- Atomic Force Microscope (AFM)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare contaminated fused silica samples using a dip-coating method with a consistent pull-speed (e.g., 85 mm/min) to ensure uniform contaminant layers [1].

- Parameter Matrix: Design a experiment varying RF power (e.g., 50 W to 150 W) and gas pressure (e.g., 5 to 20 mbar) while using a fixed, standard gas mixture (e.g., O₂ and Ar) and an initial treatment duration.

- Plasma Characterization: For each parameter set:

- Cleaning Efficacy Assessment: After processing:

- Measure the water contact angle to characterize surface energy and cleanliness [21].

- Quantify optical transmittance at the target wavelength (e.g., 355 nm) to assess performance recovery [1] [21].

- Use AFM to scan the surface and quantify the removal of contaminants and any change in surface roughness [21].

- Data Analysis: Construct contour plots or response surfaces to visualize the relationship between power, pressure, and the measured responses (e.g., ion density, transmittance recovery).

Protocol: Establishing Treatment Duration and Damage Threshold

Objective: To identify the optimal treatment time that ensures complete contaminant removal while avoiding substrate damage.

Materials:

- Low-pressure plasma reactor

- Fused silica samples with standardized organic contamination

- Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) test setup

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectrometer (XPS) or Raman Spectrometer

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation software (e.g., LAMMPS with ReaxFF force field)

Procedure:

- Experimental Duration Sweep: Process contaminated samples for a series of durations (e.g., from 1 to 30 minutes) at a fixed, optimized power and pressure.

- Post-Process Analysis:

- Use XPS or Raman spectroscopy to monitor the disappearance of carbon signatures (indicating organic removal) and the subsequent emergence of surface network defects on the fused silica itself [8] [23].

- Test the LIDT of the cleaned samples to correlate cleaning duration with the recovery and potential degradation of optical performance [21].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulation:

- Construct an atomistic model of the fused silica surface with an adsorbed hydrocarbon contaminant layer.

- Simulate the bombardment of oxygen plasma at varying energies (e.g., 10 eV to 100 eV) and fluxes, tracking the removal of contaminant atoms and the sputtering of substrate Si and O atoms [1] [8].