Mass Resolution vs. Mass Accuracy: A Practical Guide for Reliable HRMS Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to understanding and applying the distinct yet interconnected concepts of mass resolution and mass accuracy in High-Resolution...

Mass Resolution vs. Mass Accuracy: A Practical Guide for Reliable HRMS Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide to understanding and applying the distinct yet interconnected concepts of mass resolution and mass accuracy in High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS). It covers foundational principles, methodological best practices for enhancing data quality, troubleshooting for optimal instrument performance, and validation strategies for confident data interpretation. By clarifying these critical parameters, the article aims to empower professionals to generate more reliable, reproducible, and impactful results in applications ranging from proteomics and metabolomics to biopharmaceutical characterization.

Demystifying Core Concepts: The Fundamental Difference Between Mass Resolution and Mass Accuracy

In high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) research, two concepts are fundamental for precise molecular analysis: mass resolution and mass accuracy. While mass accuracy refers to the difference between measured and true mass values, this guide focuses on mass resolution—the instrument's ability to distinguish between closely spaced ions in a mass spectrum [1]. This capability becomes particularly critical when analyzing complex samples where distinguishing between isobaric species (compounds with nearly identical mass) can determine the success of an experiment [2] [3].

The pharmaceutical and life sciences increasingly rely on high-resolution MS for applications ranging from proteomics and lipidomics to drug metabolism studies and biotherapeutic characterization [4] [5]. Within this context, understanding mass resolution is not merely academic; it directly influences method development, data interpretation, and ultimately, the confidence in analytical results.

Fundamental Definitions and Mathematical Framework

Distinguishing Resolution from Resolving Power

In mass spectrometry literature, the terms "resolution" and "resolving power" have been used in ways that can create confusion. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), these terms are formally defined as follows [1]:

- Resolution (ΔM): The minimum mass difference between two peaks of equal intensity that allows them to be distinguished as separate entities.

- Resolving Power (R): A dimensionless quantity expressed as R = M/ΔM, where M is the mass of the ion being measured and ΔM is the resolution.

The IUPAC definition states that a larger resolution value indicates better peak separation [1]. However, some mass spectrometrists reverse these definitions, aligning with conventions in other fields of physics [1]. This technical guide will adhere to the IUPAC convention.

Quantification Methods: Peak Width and Valley Definitions

The numerical value of resolution depends on the method used for its determination. The two most common methods are:

- Peak Width Definition: ΔM is defined as the width of the peak measured at a specified fraction of the peak height, typically 50% (Full Width at Half Maximum, or FWHM) or other percentages such as 5% or 10% [6] [1].

- Valley Definition: ΔM is defined as the closest spacing of two peaks of equal intensity where the valley between them falls to a specified fraction (e.g., 10% or 50%) of the peak height [1].

For practical purposes, the 5% peak width definition is roughly equivalent to the 10% valley definition [1]. When reporting resolution values, it is essential to specify which method was used.

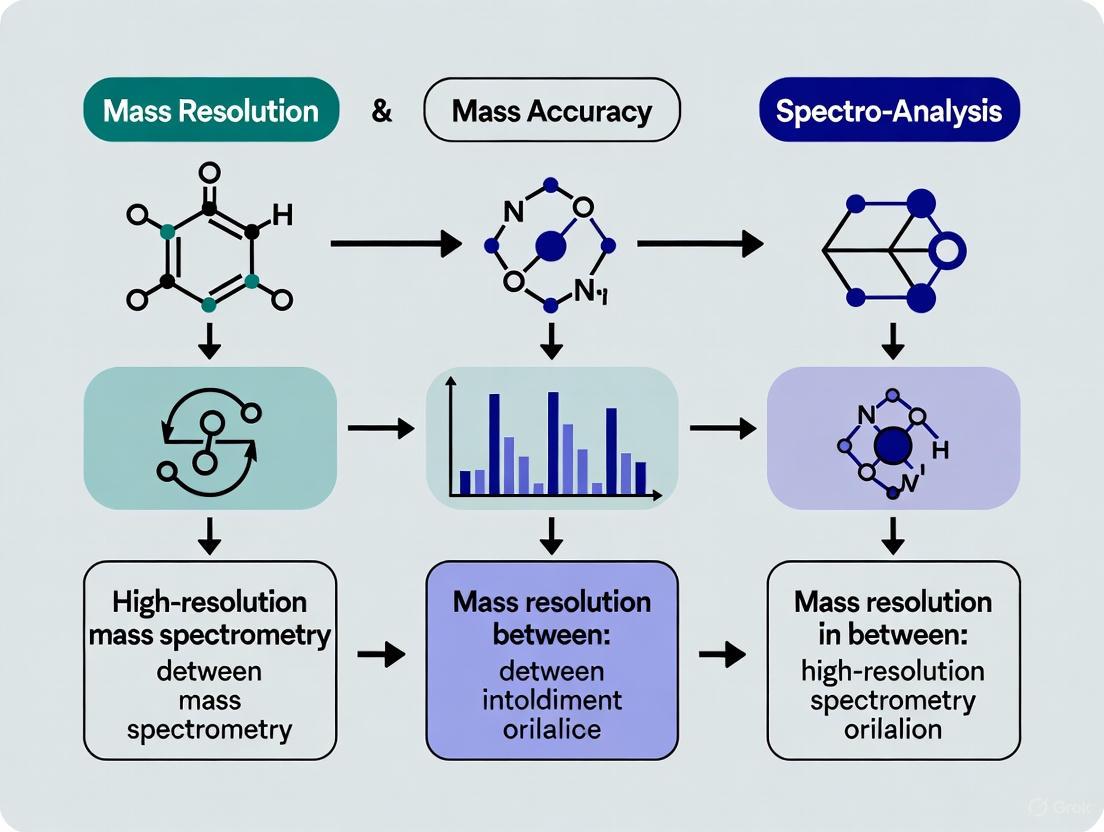

Diagram 1: Core conceptual framework for understanding mass resolution, showing the relationship between formal definitions and quantification methods.

Mathematical Relationships and Calculation Approaches

The fundamental relationship between resolving power (R), mass (M), and the minimum distinguishable mass difference (ΔM) is expressed as:

R = M / ΔM

This equation demonstrates that for a given resolving power, the ability to distinguish close masses (ΔM) becomes more challenging as the mass (M) increases. For example, a resolving power of 10,000 at m/z 100 allows distinction of peaks 0.1 Da apart, while at m/z 1000, it can only distinguish peaks 0.1 Da apart if the resolving power is 100,000 [1].

Table 1: Mass Resolution Calculation Examples Across Different Instrument Types

| Mass (m/z) | Resolving Power (R) | Minimum Distinguishable ΔM | Typical Instrument Capability |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 10,000 | 0.01 Da | Low-resolution TOF |

| 500 | 50,000 | 0.01 Da | High-resolution TOF |

| 500 | 100,000 | 0.005 Da | Orbitrap |

| 500 | 1,000,000 | 0.0005 Da | FT-ICR |

Current High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Platforms

Instrumentation Landscape and Performance Metrics

Different mass analyzer technologies offer varying levels of performance in terms of resolution, scan speed, and mass accuracy. The selection of an appropriate platform depends on the specific application requirements and necessary trade-offs.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Platforms

| Mass Analyzer Type | Typical Resolving Power (FWHM) | Scan Speed | Key Applications | Technology Principle |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT-ICR | 1,000,000+ [6] [3] | ~1 Hz [6] | Petroleum analysis, complex mixture characterization [3] | Ion cyclotron frequency in magnetic field [3] |

| Orbitrap | 100,000 - 500,000 [6] [3] | 1-10 Hz [6] [3] | Proteomics, metabolomics, biopharma [4] [5] | Electrostatic axial oscillation [3] |

| High-Res TOF | 40,000 - 60,000 [6] [3] | Up to 500 Hz [6] | Metabolite ID, lipidomics [2] [3] | Time-of-flight measurement [3] |

| Quadrupole/Ion Trap | 1,000 - 10,000 [6] | Variable | Targeted analysis, precursor selection | Mass-selective stability |

Recent Technological Advancements

The field of high-resolution mass spectrometry continues to evolve rapidly, with instrument manufacturers pushing performance boundaries:

- The Orbitrap Astral Zoom mass spectrometer, introduced in 2025, delivers 35% faster scan speeds, 40% higher throughput, and 50% expanded multiplexing capabilities while maintaining high resolution [5].

- Structures for Lossless Ion Manipulation (SLIM) technology demonstrates resolving power exceeding 200 for ion mobility separations, enabling distinction of lipid isomers that co-elute using conventional methods [2].

- Improvements in time-of-flight (TOF) instrumentation now enable resolving powers of 40,000-60,000 with significantly faster acquisition rates compared to Fourier transform-based instruments [6] [3].

Experimental Protocols for Maximizing Mass Resolution

Method Development for High-Resolution Applications

Achieving optimal mass resolution in practice requires careful method development across multiple parameters:

Instrument Calibration and Tuning

- Perform regular mass calibration using certified reference standards appropriate for the mass range of interest.

- For high-resolution accurate mass measurements, use internal calibration compounds or lock mass correction to maintain mass accuracy during longer runs.

- Optimize ion transmission settings to balance sensitivity and resolution, as overfilling the analyzer can degrade performance.

Chromatographic Considerations

- Match LC peak widths to MS acquisition speed; for UHPLC peaks of 2-3 seconds, ensure sufficient data points (10-15) across the peak for reliable integration [3].

- Consider comprehensive 2D-LC approaches for highly complex samples to increase peak capacity and reduce spectral complexity entering the MS at any given time [4].

Data Acquisition Strategies

- For Orbitrap instruments, select resolving power settings based on application needs, balancing against scan speed requirements [3].

- Employ data-dependent acquisition (DDA) or data-independent acquisition (DIA) methods that leverage high resolution for precursor selection and fragment ion analysis.

Case Study: Lipid Isomer Separation Using SLIM Ion Mobility-MS

Experimental Objective: To resolve and identify isomeric lipids in complex biological extracts using high-resolution ion mobility spectrometry coupled to mass spectrometry [2].

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Obtain purified TLC fractions of total lipid extracts as lyophilized powders.

- Reconstitute in chloroform and prepare to final concentration of 10 μg/mL in 1:2 chloroform:methanol.

- For lipid isomer standards, prepare at 10 μg/mL in 1:1 acetonitrile:methanol (for PC and PE standards) or 40 μM equimolar concentrations in 1:1 methanol:IPA with 2 mM ammonium acetate (for TG standards) [2].

Instrumentation and Parameters:

- Platform: SLIM IM (Structures for Lossless Ion Manipulation) interfaced with high-resolution Q-TOF mass spectrometer.

- Ionization: Positive electrospray ionization (ESI) via Jet Stream source.

- Drift Gas: Ultra-high purity nitrogen for nitrogen-based CCS measurements (CCSN2).

- Data Acquisition: Flow injection analysis using liquid chromatography system without separation column for direct infusion [2].

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Perform two-step calibration procedure to align TW(SLIM)CCS values to within 2% average bias of reference DTCCS values.

- Identify lipid features by combination of accurate m/z, CCS, retention time, and linear mobility-mass correlations.

- Curate high-resolution IM lipid structural atlas using multidimensional separation data [2].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for high-resolution lipid isomer analysis using SLIM ion mobility-mass spectrometry.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful high-resolution MS analysis requires carefully selected reagents and consumables to maintain instrument performance and ensure reproducible results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Resolution MS Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (Optima grade methanol, chloroform, water, acetonitrile, IPA) [2] | Sample preparation and mobile phase components; minimize background interference | Lipid extraction and reconstitution for MS analysis [2] |

| Mobile Phase Additives (Formic acid, ammonium formate) [2] | Modify pH and ionic strength for improved ionization efficiency | Positive ESI mode analysis of lipids and metabolites [2] |

| Mass Calibration Standards (e.g., HFAP tuning mixture) [2] | Instrument mass calibration and accuracy verification | Daily mass calibration for high-resolution accurate mass measurements [2] |

| Certified Reference Materials (Lipid isomer standards) [2] | Method development and performance verification | Assessing separation capabilities for isomeric systems [2] |

| LC Columns (U/HPLC columns with sub-2μm particles) | High-efficiency chromatographic separation | UHPLC separation preceding high-resolution MS detection [3] |

Application in Drug Development and Biopharmaceutical Analysis

High-resolution mass spectrometry has become indispensable in modern drug development, particularly for the characterization of complex biotherapeutics:

Biopharmaceutical Characterization

- Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) and New Molecular Formats (NMFs): High-resolution MS enables comprehensive characterization of critical quality attributes (CQAs) including post-translational modifications (PTMs) [4].

- Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs): HRMS is used to assess drug-to-antibody ratios, conjugation sites, and payload stability [4].

- Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD) Molecules: High-resolution LC-MS/MS facilitates impurity profiling and detection of low-abundance degradation products [4].

High-Throughput Peptide Mapping Lonza has developed high-throughput, multi-attribute monitoring (MAM) peptide mapping workflows for targeted PTM analysis of biotherapeutics. These workflows incorporate [4]:

- Shorter LC methods designed to detect critical PTMs

- Optimized MS acquisition settings for quantification of chromatographic peaks

- Faster data curation using traditional software combined with R programming

- A toolbox of protease digestion protocols for efficient digestion of NMFs

Quantitative Proteomics in Clinical Research High-resolution MS platforms are increasingly applied in clinical proteomics for biomarker discovery and validation. The combination of high resolution and accurate mass measurements enables [4]:

- Label-free quantification or isobaric tagging for precise measurement of protein degradation and target engagement

- Targeted proteomics using triple quadrupole instruments for biomarker validation

- Metabolic pathway analysis using LC-QTOF or LC-Orbitrap platforms

The continued evolution of high-resolution MS instrumentation and methodologies ensures that mass resolution will remain a critical parameter for advancing drug development and biopharmaceutical characterization.

Mass resolution—the fundamental ability to distinguish between closely spaced ions—remains a cornerstone capability in high-resolution mass spectrometry. As instrumentation continues to advance, with platforms like the Orbitrap Astral Zoom achieving new levels of performance, researchers gain increasingly powerful tools for discriminating subtle molecular differences in complex samples [5]. Understanding the principles, measurement approaches, and practical implementation of high mass resolution enables scientists to push the boundaries of what is analytically possible in pharmaceutical research, proteomics, and biomarker discovery.

The interplay between mass resolution and mass accuracy continues to define the quality and reliability of mass spectrometry data. As the field progresses, the strategic application of high-resolution MS platforms, matched to specific analytical challenges, will undoubtedly yield new insights into complex biological systems and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

In high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) research, the concepts of mass resolution and mass accuracy are fundamental, yet they are often conflated. While mass resolution defines the ability of a mass spectrometer to distinguish two closely spaced peaks, mass accuracy refers to the closeness of the measured mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) to its true, theoretical value [1] [6]. This distinction is critical for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on HRMS for definitive molecular identification, structural elucidation, and confirmation of elemental composition. Accurate mass measurement, enabled by high-resolution instrumentation, has become a cornerstone in the analytical toolkit, driving decisions from the earliest stages of drug discovery through to quality control in commercial manufacturing [7]. The precision of these measurements directly influences the ability to differentiate between analytes of interest and complex biological matrices, identify subtle biotransformations, and correctly assign fragment ions in MS/MS experiments [8]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of mass accuracy, its relationship with mass resolution, and the detailed methodologies required to achieve and validate high-quality measurements in a research setting.

Core Concepts: Defining Mass Accuracy and Its Relationship to Resolution

Key Terminology and Definitions

A clear understanding of the following terms is essential for discussing mass accuracy [9] [8]:

- Accurate Mass: The experimentally measured mass of an ion, reported with a specified degree of uncertainty. It is this measured value that is compared to the theoretical mass.

- Exact Mass: The calculated mass of an ion or molecule based on the single most abundant isotope for each element (e.g., 12C, 1H, 16O, 14N).

- Monoisotopic Mass: The mass of a molecule calculated using the exact mass of the most abundant naturally occurring stable isotope for each element. For most organic small molecules, this is synonymous with the exact mass.

- Nominal Mass: The integer mass of a molecule or ion, calculated using the integer mass of the most abundant isotope for each element.

- Mass Accuracy: The agreement between the measured mass (accurate mass) and the theoretical mass (exact mass). It is typically expressed in milliDaltons (mDa) or parts per million (ppm).

The formula for calculating mass accuracy in ppm, the most common unit, is: Mass Accuracy (ppm) = [(Measured Mass - Theoretical Mass) / Theoretical Mass] × 10^6

Mass Accuracy vs. Mass Resolution and Resolving Power

It is crucial to distinguish mass accuracy from the related, but distinct, concepts of resolution and resolving power. Table 1 summarizes the key differences and purposes of these fundamental parameters.

Table 1: Differentiating Mass Accuracy, Resolution, and Resolving Power

| Parameter | Definition | Typical Units | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Accuracy | Closeness of a measured m/z value to its true theoretical value [8]. | ppm, mDa | Verify elemental composition; identify unknown compounds. |

| Mass Resolution | The minimum separation between two peaks of equal height such that they can be distinguished [1]. | N/A (a value of separation) | Determine if two ions of similar m/z can be distinguished in a spectrum. |

| Mass Resolving Power | A performance parameter of the instrument, defined as m/Δm, where Δm is the peak width [1] [6]. | Unitless (e.g., 50,000) | Describe instrument performance and its inherent capability to separate ions. |

While high resolving power is often necessary to achieve high mass accuracy by separating an analyte peak from nearby chemical interferences, it does not guarantee it [8]. A mass spectrometer can have high resolving power (sharp peaks) but poor mass accuracy if its mass scale is not properly calibrated.

The Critical Link: Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Dynamic Range

The practical mass accuracy achievable in an experiment is not solely a function of the instrument's specifications. It is highly dependent on experimental conditions, particularly the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) and dynamic range [10].

The standard deviation of the mass measurement, σ(m), is inversely proportional to the S/N [10]: σ(m) ≈ Constant / (S/N)

This relationship means that low S/N leads to greater imprecision and, consequently, poorer mass accuracy. Furthermore, the presence of a large, interfering peak adjacent to a small analyte peak—a common scenario in complex mixtures—requires a much higher resolving power to achieve the same valley separation than if the two peaks were of equal height [10]. This interplay between dynamic range and required resolving power directly impacts the effective mass accuracy for low-abundance species.

Quantitative Data: Performance Standards Across Instrumentation

The capabilities of different mass analyzers vary significantly. Table 2 provides a comparative overview of typical resolving power and mass accuracy for common mass spectrometer types.

Table 2: Typical Performance of Common Mass Analyzers [6] [8]

| Mass Analyzer Type | Typical Resolving Power (FWHM) | Typical Mass Accuracy | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole / Ion Trap | 1,000 - 4,000 | ~100 - 500 ppm | Targeted quantitation, routine ID, precursor selection. |

| Time-of-Flight (TOF) | 10,000 - 60,000 | < 5 ppm (with internal calibration) | Metabolite ID, impurity screening, high-speed LC-MS. |

| Orbitrap | 100,000 - 500,000 | 1 - 3 ppm | High-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) for untargeted analysis, proteomics. |

| FT-ICR | 1,000,000 - 20,000,000 | < 1 ppm | Ultra-high resolution applications, petroleum, and complex mixture analysis. |

Mass accuracy is often interpreted in the context of the mass error in ppm or mDa. Table 3 illustrates how the same absolute mass error (in mDa) translates to different relative errors (in ppm) at different masses, highlighting why ppm is the preferred unit for reporting across a wide mass range.

Table 3: Relationship Between Absolute and Relative Mass Error [8]

| Theoretical Mass (Da) | Measured Mass (Da) | Absolute Error (mDa) | Relative Error (ppm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 250.0000 | 250.0250 | 25.0 | 100.0 |

| 500.0000 | 500.0250 | 25.0 | 50.0 |

| 1000.0000 | 1000.0250 | 25.0 | 25.0 |

Methodologies and Protocols for High Mass Accuracy

Achieving and maintaining high mass accuracy requires a rigorous approach to instrumentation, calibration, and data acquisition.

Instrument Calibration

Calibration is the process of adjusting the instrument's measured signal using a standard to ensure accuracy and precision [11]. For mass spectrometers, this involves running a calibration solution containing compounds with known, precisely defined masses across the m/z range of interest.

- Internal Calibration: The calibrant is introduced simultaneously with the analyte, providing the highest possible mass accuracy by correcting for drifts during the measurement.

- External Calibration: The calibrant is run before and/or after the analytical sequence, and a calibration curve is applied to the sample data.

The following workflow diagram outlines the standard operating procedure for mass spectrometer calibration.

High-Accuracy Measurement with FT-ICR MS

Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR) Mass Spectrometry represents the gold standard for mass resolution and accuracy [10]. The following protocol details the steps for obtaining high-quality data.

Experimental Protocol: High-Mass-Accuracy Analysis using FT-ICR MS

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a stock solution of the analyte (e.g., 1 mg/mL in a suitable solvent like toluene-methanol) [10].

- For electrospray ionization (ESI), dilute the stock to a final concentration (e.g., 0.25 mg/mL) with a solvent containing a volatile acid or base (e.g., 2% formic acid) to promote protonation [10].

2. Instrument Setup and Ionization:

- Directly infuse the sample through a fused-silica capillary at a low flow rate (e.g., 0.5 μL/min) using a micro-ESI source [10].

- Apply appropriate ESI voltages (e.g., needle: 2.3 kV; tube lens: 350 V) [10].

3. Ion Accumulation and Cooling:

- Transfer ions through an external quadrupole mass filter for isolation if required.

- Accumulate and cool ions in a multipole (e.g., octopole) using helium gas at low pressure (~2 mTorr) to thermalize them, which improves signal stability and mass accuracy [10].

4. Ion Transfer and Trapping:

- Transfer the cooled ions to the ICR cell.

- Utilize a high-performance cell design (e.g., a dynamically harmonized cell or electrically compensated cell) to maintain a near-perfect trapping potential, which is critical for sustaining ion coherence and achieving high resolution [10].

5. Excitation and Detection:

- Apply a tailored excitation waveform (e.g., a SWIFT waveform) for broadband excitation of the trapped ions [10].

- Detect the image current induced by the coherently orbiting ions, acquiring a high-resolution time-domain transient (e.g., 8 Mword) [10].

6. Data Processing and Mass Calibration:

- Convert the time-domain transient to a mass spectrum via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT).

- Perform phase correction to display the spectrum in absorption mode, which provides higher resolving power and better mass accuracy than the magnitude mode [10].

- Calibrate the mass spectrum using a known internal or external standard. For the highest accuracy, use a multi-point calibration equation and consider segmenting the mass scale or including a space charge term in the calibration to account for ion abundance effects [10].

- Implement conditional averaging: Average only those mass spectra whose total ion abundances fall within a narrow range (e.g., 10%) to minimize the space charge-induced mass shift variations between scans [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, standards, and materials essential for conducting high mass accuracy experiments.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High Mass Accuracy MS

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Technical Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Calibration Standard | To calibrate the m/z scale of the mass spectrometer for accurate mass assignment. | A solution containing compounds with known exact masses across a wide range (e.g., sodium trifluoroacetate for ESI negative mode; a mixture of caffeine, MRFA, and Ultramark for ESI positive mode). |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | To prepare mobile phases, samples, and standards with minimal ion suppression and background interference. | Solvents (water, acetonitrile, methanol) with low levels of volatile impurities and additives (e.g., 0.1% formic acid). |

| Lock Mass Substance | To provide a continuous internal m/z reference for real-time calibration correction during LC-MS runs. | A compound introduced via a second sprayer or co-infused with the analyte that provides a persistent ion of known mass (e.g., phthalates, polysiloxanes). |

| Tuning and Optimization Mix | To optimize instrument parameters (ion optics, voltages) for maximum sensitivity and stability. | A solution with several known compounds used in automated instrument tuning routines. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | For online or offline sample cleanup to remove salts and matrix components that can suppress ionization and degrade accuracy. | Reversed-phase, mixed-mode, or other chemistries tailored to the analyte. Used in systems like RapidFire for high-throughput screening [12]. |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The relationship between high resolution and high mass accuracy is the enabling force behind several critical applications in pharmaceutical research. The following diagram conceptualizes how these two parameters work together to solve analytical challenges.

- Differentiating Analytes from Matrix: Accurate-mass data allows for the use of narrow mass extraction windows (e.g., ±0.005 Da instead of ±0.5 Da), effectively filtering out chemical noise from biological matrices and eliminating false positives [8].

- Identifying Biotransformations: Accurate mass enables differentiation between isobaric metabolic transformations. For example, it can distinguish between an oxidation (M + O, +15.9949 Da) and a methylation (M + CH2, +14.0156 Da), which are indistinguishable with nominal mass instruments [8].

- Elemental Composition Assignment: A mass accuracy of 5 ppm or better is often sufficient to determine a unique elemental composition for molecules up to ~500 Da, drastically narrowing the possibilities for unknown identification [10] [8].

- Resolving Isotopic Fine Structure: Ultra-high resolution (Resolving Power > 1,000,000) allows the separation of individual isotopologues, such as 34S from 2H2, providing direct evidence for the presence of sulfur in a molecule and further validating the assigned elemental composition [10].

In high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), the terms mass resolution and mass accuracy represent fundamentally distinct concepts that are frequently conflated, leading to significant misinterpretations in analytical data. Mass resolution refers to the ability of a mass spectrometer to distinguish between ions of similar mass-to-charge ratios, whereas mass accuracy denotes the precision of the measured mass compared to its true theoretical value. This whitepaper delineates these critical parameters, articulating their individual impacts on data reliability, elemental composition assignment, and subsequent analytical conclusions. Within the broader thesis of HRMS research, understanding this distinction is paramount for robust method development, accurate metabolite identification, and reliable quantitative analyses in drug development pipelines.

The conflation of mass resolution and mass accuracy persists as a common pitfall in scientific communication, potentially compromising data interpretation and methodological rigor in mass spectrometry. Mass resolution is formally defined as the ability of a mass analyzer to separate two peaks of similar mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio, typically quantified as m/Δm50%, where Δm50% is the peak width at half-maximum height [10]. In practical terms, higher resolution allows the separation of isobaric species that would otherwise co-elute and confound analysis.

Conversely, mass accuracy describes the deviation between the measured m/z value and its true theoretical value, usually expressed in parts per million (ppm) or milliDaltons (mDa) [13]. It is a measure of measurement precision, crucial for confident elemental composition assignment. The relationship between these parameters is synergistic but not synonymous; high resolution facilitates accurate mass measurement by isolating the target ion from potential interferences, yet a instrument can exhibit high resolution without concomitant high accuracy [13]. This distinction forms the foundational principle for selecting appropriate HRMS instrumentation and methodologies for specific analytical challenges in pharmaceutical research and development.

Foundational Principles and Definitions

Mass Resolution: The Separating Power

Mass resolution quantifies the instrument's capacity to distinguish adjacent peaks in a mass spectrum. The required resolving power is not a fixed value but depends critically on the analytical context, including the dynamic range of the sample and the mass difference between the species to be separated [10]. For two peaks of equal height and width, the resolution required for baseline separation is conventionally defined. However, for a minor peak in the presence of a major interferent (e.g., a 100:1 height ratio), the required resolving power can be an order of magnitude higher to produce a discernible valley between them [10]. This has direct implications for analyzing complex mixtures like biological samples or petroleum crude oil, where dynamic ranges can exceed 10,000:1.

Mass Accuracy: The Measure of Truth

Mass accuracy is the cornerstone of confident compound identification. It is formally defined by the equation:

ppm error = ( |measured mass - theoretical mass| / theoretical mass ) × 10⁶ [14].

The accuracy required for unambiguous elemental composition assignment depends on the mass of the analyte. For molecules below 500 Da, a mass accuracy of approximately 1 mDa is often sufficient to assign a unique elemental composition for common biological elements (C, H, N, O, S, etc.) [10]. The reliability of this assignment is further enhanced by the analysis of isotopic fine structure—the ability to resolve and measure individual isotopologues (e.g., ³⁴S from ²H²H), which provides unequivocal confirmation of the presence and number of specific elements like sulfur in the monoisotopic species [10].

Table 1: Core Definitions and Impact Factors of Mass Resolution and Accuracy

| Parameter | Formal Definition | Typical Units | Primary Influence on Data | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Resolution | m/Δm50% | Resolution (e.g., 50,000) | Ability to distinguish between ions of similar m/z; reduces spectral interferences [10] | Mass analyzer type (FT-ICR, Orbitrap, TOF), magnetic field strength, acquisition time [10] [14] |

| Mass Accuracy | ( | ppm or mDa | Confidence in elemental composition assignment; reliability of compound identification [13] [14] | Signal-to-noise ratio (S/N), mass calibration, space charge effects, digital resolution [10] |

Experimental Methodologies for HRMS Analysis

The following section outlines a detailed protocol for achieving high mass accuracy and resolution, specifically using Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry (FT-ICR MS), which offers the highest broadband mass resolution [10].

Sample Preparation Protocol

- Sample Dissolution: Prepare a stock solution of the analyte (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in a suitable solvent such as toluene. For electrospray ionization (ESI), further dilute the sample (e.g., to 0.25 mg/mL) with a 49:49 (v/v) mixture of toluene-methanol, adding 2% formic acid to promote protonation in positive ion mode [10].

- Complex Mixture Pre-fractionation: For compositionally complex samples like plasma proteome, employ a "divide-and-conquer" strategy. This involves: a) Depletion of high-abundance proteins (e.g., albumin); b) Fractionation via strong cation exchange (SCX) chromatography; c) Protein digestion with a sequence-specific protease (e.g., trypsin); d) Further separation of peptides using reverse-phase liquid chromatography (LC) [15].

FT-ICR MS Instrumental Configuration and Data Acquisition

- Instrument Setup: Utilize an FT-ICR mass spectrometer equipped with a high-field superconducting magnet (e.g., 9.4 tesla). Employ an electrically compensated ICR cell design (e.g., Tolmachev or dynamically harmonized cell) to maintain a quadrupolar trapping potential for sustained ion coherence [10].

- Ionization and Transmission: Introduce the sample via a fused silica capillary at a low flow rate (e.g., 0.5 μL/min) using microESI. Apply typical ESI voltages (e.g., needle at 2.3 kV, tube lens at 350 V). Transfer ions through an external quadrupole mass filter and a custom-built accumulation octopole, cooling them with helium gas (~2 mTorr) before transfer to the ICR cell [10].

- Waveform Generation and Detection: For targeted analysis, construct and apply a stored waveform inverse Fourier transform (SWIFT) waveform for ion isolation. Follow with a broadband excitation waveform (e.g., 50 Hz/μs sweep rate). Acquire the time-domain transient (e.g., 8 Mword) using a high-speed digitizer [10].

- Data Processing: Subject the time-domain transient to a Fourier transform to convert it into a frequency spectrum. Apply a mass-calibration transformation, often incorporating a space charge term and using segmented calibration for complex spectra, to convert frequency data into m/z and abundance pairs [10] [15].

Data Processing for Enhanced Accuracy

- Conditional Averaging: To mitigate mass measurement errors induced by space charge effects (which shift peak positions based on the number of ions in the cell), average only those mass spectra whose total ion abundances or summed peak heights fall within a narrow specified range (e.g., 10%). This practice can reduce the root-mean-square (rms) mass error by a factor of 2–3 [10].

- Phase Correction: Apply phase correction to the frequency spectrum to display it in absorption mode rather than the default magnitude mode. This transformation significantly improves mass resolution, mass accuracy, and the signal-to-noise ratio [10].

Data Presentation and Visualization

Quantitative Data and Performance

Table 2: Representative Quantitative Performance of Sitagliptin from HRMS Analysis using AI-Driven Data Processing

| Experiment Type | Linear Dynamic Range | Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ) | Upper Limit of Quantitation (ULOQ) | Accuracy and Precision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MRMHR | > 3 orders of magnitude | 1 ng/mL | 5000 ng/mL | Within ±25% acceptance criteria [16] |

| SWATH DIA | > 3 orders of magnitude | 1 ng/mL | 5000 ng/mL | Within ±25% acceptance criteria [16] |

| Nominal MRM | > 3 orders of magnitude | 1 ng/mL | 2000 ng/mL | Within ±25% acceptance criteria [16] |

Visualizing the HRMS Workflow and Pitfall

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of an HRMS analysis, highlighting the distinct roles of and relationships between mass resolution and mass accuracy, culminating in the common pitfall of their conflation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry Experiments

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | Sample dissolution and mobile phase for LC separation; minimizes chemical noise. | Toluene, methanol, acetonitrile, water (LC-MS grade) [10] [16] |

| Ionization Additives | Promotes protonation or deprotonation of analytes for efficient ion formation in ESI. | Formic acid (0.1-2%), ammonium acetate [10] [16] |

| Protease Enzyme | Digests proteins into smaller peptides for bottom-up proteomics analysis. | Trypsin (sequence-specific) [15] |

| Chromatography Columns | Separates complex mixtures to reduce ion suppression and simplify mass spectra. | Reverse-phase C18 (e.g., 2.1 x 50 mm, 1.7 µm) [16] |

| Calibration Standards | Enables accurate mass calibration before or during sample analysis. | Commercial standard mixes covering a wide m/z range. |

| High-Field FT-ICR Mass Spectrometer | Provides the highest broadband mass resolution and accuracy for complex mixture analysis. | Instrument with a >9.4 T superconducting magnet and a dynamically harmonized ICR cell [10] |

The distinction between mass resolution and mass accuracy is not merely semantic but foundational to the integrity of mass spectrometry data. Resolution empowers separation, while accuracy validates identification. The conflation of these concepts represents a critical pitfall that can undermine analytical confidence, leading to misassignment of elemental compositions and erroneous biological conclusions. For researchers in drug development, a precise understanding and clear communication of these parameters are essential for robust method validation, reliable metabolite profiling, and the successful application of HRMS across the discovery and development pipeline. As HRMS technology continues to evolve, maintaining this conceptual clarity will be paramount for harnessing its full potential in solving complex analytical challenges.

In high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), the concepts of mass resolution and mass accuracy are fundamentally intertwined. While distinct, they share a synergistic relationship where high mass resolving power is often a critical prerequisite for achieving high mass accuracy, especially in complex analytical scenarios. Mass resolving power is defined as a mass analyzer's ability to distinguish between two adjacent peaks, typically calculated as m/Δm50%, where Δm50% is the peak's full width at half maximum (FWHM) [10] [17]. Mass accuracy, on the other hand, refers to the conformity between the measured m/z value and its true theoretical value, usually reported in parts per million (ppm) [18]. This guide explores the critical dependency of mass accuracy on mass resolution, detailing the underlying principles, experimental methodologies, and practical implications for research and drug development.

The Fundamental Link Between Resolution and Accuracy

At its core, the relationship between resolution and accuracy concerns the certainty of a measurement. Accurate mass measurement requires that the measured mass spectral peak corresponds to a single, unique ionic species [10]. If a mass spectral peak contains an unresolved isobaric interference—where two ions with the same nominal mass but different exact masses contribute to the same signal—the resulting centroid mass will be shifted, leading to an inaccurate measurement [18]. The required mass resolving power increases significantly with the dynamic range of the sample; distinguishing a low-abundance ion from an adjacent high-abundance ion requires a much higher resolving power than separating two peaks of equal height [10].

Furthermore, the precision of the mass measurement, which directly limits accuracy in the absence of systematic error, is governed by the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of the peak [10]. Higher resolution leads to narrower peak widths, which increases peak height and thus S/N for a given number of ions, ultimately improving mass measurement precision [10]. The highest broadband mass resolving power and mass accuracy are currently provided by Fourier transform mass spectrometry (FTMS) instruments, namely Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) and Orbitrap mass analyzers [10] [17].

Visualizing the Core Relationship

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental interdependence between mass resolution and mass accuracy.

Quantitative Comparison of Mass Analyzer Performance

The capability for high resolution and accuracy varies significantly across different mass analyzer technologies. The following table summarizes the typical resolving power and mass accuracy performance of common mass spectrometers, highlighting the superior performance of FT-based instruments.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Mass Analyzers in High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

| Mass Analyzer Type | Typical Resolving Power (FWHM) | Typical Mass Accuracy (ppm) | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole / Ion Trap | 1,000 – 10,000 [6] | >10 [18] | Routine targeted analysis, precursor ion selection |

| Time-of-Flight (TOF) | 10,000 – 60,000 [17] [6] | 1 - 5 [18] | High-speed profiling, GC-MS coupling |

| Orbitrap | 100,000 – 1,000,000+ [17] [6] [19] | <1 - 3 [17] [20] | Untargeted metabolomics, proteomics, biopharma characterization |

| FT-ICR | 1,000,000 – 20,000,000+ [10] [6] | <1 [10] | Ultra-complex mixture analysis (e.g., petroleum, natural products) |

The performance of these analyzers is not static. Recent advancements in FTMS continue to push the boundaries. For example, next-generation Orbitrap instruments, such as the Orbitrap Astral Zoom, are engineered to deliver 35% faster scan speeds and 40% higher throughput, which enhances the ability to acquire high-resolution data across narrow chromatographic peaks [19]. In FT-ICR MS, innovations in cell design, such as the dynamically harmonized cell, and advanced data processing techniques like phase correction to absorption-mode, have been pivotal in achieving resolving powers over 1,000,000 for proteins [10].

Experimental Protocols: From High Resolution to High Accuracy

Achieving high mass accuracy in practice requires a rigorous experimental workflow that leverages high resolution at multiple stages. The following protocol, typical for FT-ICR MS analysis of complex mixtures, exemplifies this process.

Detailed Methodology: FT-ICR MS Analysis of a Complex Pharmaceutical Mixture

1. Sample Preparation:

- Material: Russian bitumen dissolved in toluene is used as a model complex mixture, but the principles apply to pharmaceutical extracts or biological samples [10].

- Procedure: Prepare a stock solution (e.g., 1 mg/mL) and further dilute to a final concentration of 0.25 mg/mL with a 49:49 (v/v) toluene-methanol solvent containing 2% formic acid to promote protonation during positive ion electrospray ionization (ESI) [10].

2. Ionization and Injection:

- Ion Source: Use electrospray ionization (ESI) under typical conditions (e.g., needle voltage: 2.3 kV, tube lens: 350 V) [10].

- Introduction: Directly infuse the sample through a fused silica capillary at a low flow rate (e.g., 0.5 μL/min) [10].

3. Ion Pre-processing and Isolation:

- Cooling and Focusing: Transfer ions to an accumulation octopole and cool with helium gas (~2 mTorr) to reduce kinetic energy spread and improve trapping efficiency [10].

- Quadrupole Isolation: Use an external quadrupole mass filter to isolate a specific m/z range of interest, reducing the total ion load and potential space charge effects in the ICR cell [10].

4. High-Resolution Analysis in the FT-ICR Cell:

- Excitation: Apply a tailored frequency sweep (e.g., a SWIFT waveform) to coherently excite the trapped ions to a larger cyclotron radius without ejecting them [10].

- Detection: Detect the image current induced by the coherently orbiting ion packets on the detection electrodes. Acquire the time-domain transient (e.g., 8 Mword) for a duration sufficient to achieve the desired resolving power [10].

5. Data Processing and Calibration for High Accuracy:

- Fourier Transform: Convert the time-domain transient to a frequency-domain spectrum via Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) [10] [17].

- Advanced Calibration: Apply a multi-term calibration equation that includes a space charge correction term. For complex mixtures, use segmented mass calibration, where different calibration constants are applied to different m/z segments of the spectrum to account for systematic variations [10].

- Conditional Averaging: To mitigate space charge-induced mass shifts, average only those mass spectra whose total ion abundances fall within a narrow specified range (e.g., 10%), significantly reducing root-mean-square (rms) mass error [10].

Visualization of the Experimental Workflow

The end-to-end process from sample to high-accuracy result is depicted below.

Advanced Applications: Resolution-Enabled Accuracy in Action

Elemental Composition Assignment and the Mass Defect

The ultimate goal of many accurate mass measurements is to determine a unique elemental composition (CcHhNnOoSs...) for an unknown ion. The ability to do so hinges on the mass defect—the difference between an atom's exact mass and its nominal mass [10] [18]. Each element has a characteristic mass defect; for example, oxygen-16 has a mass defect of -0.005085 u, while hydrogen-1 has a defect of +0.007825 u [18]. Consequently, different elemental compositions with the same nominal mass will have distinct exact masses.

High mass resolution is critical to separate these isobaric species, ensuring the measured peak corresponds to a single elemental composition. As shown in Figure 3 of [18], the number of possible empirical formulae for a given mass decreases dramatically with increasing mass accuracy. A mass accuracy of ~1 mDa is often sufficient for unique assignment for molecules up to ~500 Da, but this requires the peak to be pure and free of interferences, which is a function of resolution [10].

Resolving Isotopic Fine Structure

Beyond the monoisotopic mass, ultra-high resolution allows for the resolution of isotopic fine structure. For example, the mass difference between a 34S atom and two 2H atoms is only 0.00317 Da [10]. Resolving this fine structure allows for the direct confirmation of the presence and number of sulfur atoms in a molecule, dramatically increasing the confidence of the elemental composition assignment compared to using the monoisotopic mass alone [10]. This is a powerful demonstration of how resolving power directly enables more accurate and informative molecular identification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in high-resolution mass spectrometry experiments, particularly in a pharmaceutical context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for High-Resolution MS Experiments

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents (water, methanol, acetonitrile) minimize chemical noise and background interference, which is crucial for maintaining high signal-to-noise ratio in HRMS. |

| Formic Acid / Ammonium Acetate | Common volatile additives for mobile phases in LC-MS. Formic acid aids protonation in positive ESI mode, while ammonium acetate facilitates adduct formation useful in negative mode. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Used for precise quantification and to correct for ion suppression/enhancement in the ion source, improving quantitative accuracy. |

| ESI Tuning Mix / Calibration Solution | A solution of compounds with known exact masses (e.g., sodium trifluoroacetate) used for internal mass calibration of the instrument to achieve optimal mass accuracy. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Used for sample clean-up and pre-concentration to remove salts and matrix components that can cause ion suppression and degrade resolution and accuracy. |

| FTMS Calibration Reagents | Specific reagents for high-performance calibration of FT-ICR and Orbitrap instruments, often including a mixture of compounds across a broad m/z range for segmented calibration [10]. |

The relationship between mass resolution and mass accuracy is not merely complementary but foundational. High mass resolving power is a critical enabling technology for achieving high mass accuracy by ensuring the purity of mass spectral peaks, reducing measurement uncertainty, and providing access to structurally informative details like isotopic fine structure. As mass spectrometry continues to evolve, driving advancements in fields from pharmaceutical analysis to omics research, the continued push for higher resolution and accuracy will remain intrinsically linked, each propelling the other forward to unlock deeper layers of molecular understanding.

Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) and Parts Per Million (ppm)

In high-resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) research, the unambiguous identification of chemical compositions hinges on two fundamental metrological concepts: mass resolution and mass accuracy. Mass resolution is the ability of a mass spectrometer to separate ions with similar mass-to-charge ratios (m/z), while mass accuracy quantifies how close the measured m/z value is to the true theoretical value [13]. Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) is the primary metric for defining and calculating mass resolution [21] [6]. Simultaneously, Parts Per Million (ppm) is the standard unit for expressing mass accuracy, providing a normalized measure of measurement error that is comparable across different instruments and mass ranges [22]. This guide delves into the technical definitions, mathematical relationships, and practical applications of FWHM and ppm, framing them within the critical context of distinguishing mass resolution from mass accuracy for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. A precise understanding of these metrics is indispensable for interpreting HR-MS data, particularly in applications such as elemental composition determination (ECD) and the identification of unknown compounds [10] [23].

Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM): Defining Mass Resolution

Core Definition and Mathematical Foundation

The Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) is a statistical measure of the width of a distribution or spectral peak. It is defined as the difference between the two values of the independent variable (e.g., m/z) at which the dependent variable (e.g., signal intensity) is equal to half of its maximum value [21] [24]. In simpler terms, it is the width of a mass spectral peak measured at a point halfway up its maximum height.

The FWHM is intrinsically linked to the concept of Mass Resolving Power, which is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as ( R = \frac{m}{\Delta m} ), where:

- ( m ) is the specific mass (or m/z) of the peak.

- ( \Delta m ) is the peak width at half height, precisely the FWHM [6].

Therefore, the FWHM is the ( \Delta m ) in the denominator of the resolving power equation. A smaller FWHM results in a higher resolving power, indicating a greater ability to distinguish between closely spaced peaks.

FWHM for Specific Distribution Functions

The relationship between FWHM and the underlying peak shape varies depending on the distribution function. The following table summarizes this relationship for common distributions in mass spectrometry.

Table 1: FWHM for Common Spectral Peak Distributions

| Distribution Type | Probability Density Function | FWHM Relationship |

|---|---|---|

| Normal (Gaussian) | ( f(x)=\frac{1}{\sigma\sqrt{2\pi}}\exp\left[-\frac{(x-x_0)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right] ) | ( \text{FWHM} = 2\sqrt{2\ln 2}\;\sigma \approx 2.355\;\sigma ) [21] |

| Lorentzian (Cauchy) | ( f(x)=\frac{1}{\pi\gamma\left[1+\left(\frac{x-x_0}{\gamma}\right)^{2}\right]} ) | ( \text{FWHM} = 2\gamma ) [21] |

| Hyperbolic Secant | ( f(x)=\operatorname{sech}\left({\frac{x}{X}}\right) ) | ( \text{FWHM} = 2\ln(2+{\sqrt{3}})\;X\approx 2.634\;X ) [21] |

The Critical Role of Dynamic Range in Resolution

The conventional definition of resolution assumes two peaks of equal height and width. However, in real-world samples, peaks often have vastly different intensities. The required resolving power to distinguish two peaks increases significantly as their height ratio (dynamic range) grows [10]. For example, the minimum resolving power needed to produce a discernible valley between two peaks of equal width but with a 100:1 height ratio is approximately ten times higher than for two peaks of equal height [10]. Consequently, any report of mass resolving power must specify the dynamic range under which it was measured to be meaningful for complex samples.

Parts Per Million (ppm): Quantifying Mass Accuracy

Definition and Calculation in Mass Spectrometry

In mass spectrometry, Parts Per Million (ppm) is a unit of measurement used to express the mass accuracy or the error in a measured mass compared to its theoretical value [22]. It normalizes the error to the mass of the ion, allowing for comparison across different m/z values and instruments.

The formula for calculating mass accuracy in ppm is: [ \text{ppm} = \left( \frac{\text{Theoretical m/z} - \text{Experimental m/z}}{\text{Theoretical m/z}} \right) \times 10^{6} ] A lower ppm value indicates higher mass accuracy. For instance, a mass accuracy of 5 ppm for an ion at m/z 1000 means the measured mass is within ±0.005 Da of the true mass.

The Significance of ppm in Elemental Composition Assignment

Accurate mass measurement, expressed in ppm, is a powerful tool for Elemental Composition Determination (ECD). The mass defect of different elements means that a sufficiently accurate mass measurement can drastically narrow down, or even uniquely identify, the possible elemental compositions (CcHhNnOoSs...) of an ion [10] [23]. For example, a mass accuracy of 1 ppm is often sufficient to assign a unique elemental composition for molecules up to approximately 500 Da [10]. However, as molecular weight increases, the number of possible formulas with masses within a few ppm of the measured value also increases, necessitating even higher accuracy or complementary data.

The Interplay and Distinction: FWHM (Resolution) vs. ppm (Accuracy)

A common misconception is that high resolution automatically guarantees high mass accuracy. While related, these are distinct concepts [13]. Resolution (FWHM) is about peak separation, while Accuracy (ppm) is about the correctness of the measured mass value.

However, resolution supports accuracy in two critical ways:

- Elimination of Interferences: High resolution separates an ion of interest from nearly isobaric interferences or chemical noise. If a contaminating peak is not resolved, it can skew the centroid position of the combined peak, leading to a mass measurement error [13].

- Precise Peak Centroiding: A narrower peak (smaller FWHM) provides a more well-defined maximum, making it easier to determine the peak's center with greater precision, which directly improves mass accuracy [10] [13].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between FWHM, resolution, and their combined role in achieving confident compound identification.

Diagram Title: Relationship Between FWHM, Resolution, and Accuracy in MS

Experimental Protocols for High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry

Detailed Methodology: FT-ICR MS for Complex Mixture Analysis

The following protocol, adapted from current research, outlines the steps for achieving high mass accuracy and resolution in the analysis of a complex mixture using Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance Mass Spectrometry (FT-ICR MS), which provides the highest broadband mass resolution [10].

Sample Preparation:

- Dissolution: Dissolve the sample (e.g., Russian bitumen) in an appropriate solvent (e.g., toluene) to create a 1 mg/mL stock solution.

- Dilution and Protonation: Further dilute the stock solution to a working concentration (e.g., 0.25 mg/mL) with a solvent mixture conducive to ionization. For positive ion electrospray ionization (ESI), use 49:49 (v/v) toluene-methanol with 2% formic acid to promote protonation [10].

FT-ICR Mass Spectrometry Instrumentation and Data Acquisition:

- Instrument Setup: Utilize a high-field FT-ICR mass spectrometer (e.g., equipped with a 9.4 tesla superconducting magnet) and an advanced ICR cell design (e.g., a dynamically harmonized cell or Tolmachev cell) to achieve a near-perfect electrostatic trapping field [10].

- Ionization and Injection: Introduce the sample via a direct infusion pump (e.g., 0.5 μL/min) through a microESI needle. Ions are formed under standard ESI conditions (needle voltage: ~2.3 kV) [10].

- Ion Cooling and Accumulation: Transfer ions through an external quadrupole mass filter for isolation if needed, and then to a accumulation octopole. Cool the ions with helium gas at ~2 mTorr to reduce kinetic energy and spatial distribution before transfer to the ICR cell [10].

- Excitation and Detection:

- Generate a tailored frequency sweep excitation waveform (e.g., a SWIFT waveform) using an arbitrary waveform generator.

- Apply the waveform to the ICR cell to coherently excite the ions.

- Detect the image current produced by the coherently orbiting ion packets on the detection electrodes.

- Digitize the resulting time-domain transient signal at a high sampling rate (e.g., 10 Msample/s) [10].

- Signal Processing and Calibration:

- Apply a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to convert the time-domain signal into a frequency-domain mass spectrum.

- Calibrate the spectrum using a known internal or external standard. For the highest accuracy, use multi-point calibration equations and consider segmenting the mass scale for localized calibration [10].

- Implement conditional averaging: Average only those mass spectra whose total ion abundances fall within a narrow range (e.g., 10%) to minimize space charge-induced mass shifts from scan-to-scan variation. This can reduce root mean square (rms) mass error by a factor of 2–3 [10].

- For additional resolution and accuracy, apply phase correction to display the spectrum in absorption mode, which provides a narrower peak width (FWHM) than the conventional magnitude-mode spectrum [10].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for High-Resolution MS Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| High-Field FT-ICR Mass Spectrometer | Instrument platform providing the highest broadband mass resolving power (>1,000,000) [10] [6]. | 9.4 tesla horizontal solenoid magnet [10]. |

| Advanced ICR Cell | Ion trap designed to create a uniform electric field for sustained ion coherence and long transient lifetimes. | Dynamically harmonized cell [10]. |

| Calibration Standard | Substance of known elemental composition for accurate mass scale calibration. | C19H22NO+ (m/z ~280) [23]. |

| Ionization Source (ESI/APCI) | Gentle ionization method that generates intact molecular ions for analysis. | Electrospray Ionization (ESI) or Atmospheric-Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) source [10] [23]. |

| Arbitrary Waveform Generator | Electronic hardware for creating tailored excitation waveforms for specific ion manipulation. | National Instruments PXI 5421 [10]. |

| High-Speed Digitizer | Critical for accurately capturing the high-frequency time-domain transient signal. | National Instruments PXI 5122 (10 Msample/s) [10]. |

Advanced Applications: Leveraging Resolution and Accuracy for Confident Identification

Resolving Isotopic Fine Structure

Ultra-high mass resolution (R > 1,000,000) enables the resolution of isotopic fine structure [10]. This refers to the ability to separate peaks from ions of the same nominal isotope mass but different elemental compositions, such as ¹²Cₙ versus ¹³Cₙ₋¹¹⁵N, which differ by mere mDa. Resolving these features provides direct and unequivocal evidence for the presence of specific elements (e.g., confirming the number of sulfur atoms via ³²S vs. ³⁴S separation), thereby dramatically increasing confidence in elemental composition assignment beyond what is possible with accurate mass alone [10].

Spectral Accuracy for Low-Resolution Systems

Even with high mass accuracy (< 3 ppm), formula identification can remain ambiguous. A powerful complementary approach is the use of spectral accuracy [23]. This involves calibrating the instrument's mass spectral peak shape to a known, symmetric function. Once calibrated, the theoretical isotope distribution for a candidate formula can be calculated and directly compared to the measured spectrum. The root mean square error (RMSE) of this fit, expressed as percent spectral accuracy, serves as a powerful filter to identify the correct formula, even on lower-resolution instruments like single quadrupoles, where high mass accuracy alone may lead to the wrong assignment [23].

Comparative Performance of Mass Analyzers

The capability to achieve specific levels of resolution and accuracy is inherently linked to the type of mass analyzer used. The following table provides a comparative overview of typical performance metrics for common mass spectrometers.

Table 3: Mass Resolving Power and Accuracy Across Different Mass Spectrometers

| Mass Analyzer Type | Typical Resolving Power (FWHM) | Typical Mass Accuracy (ppm) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole / Ion Trap | 1,000 - 10,000 [6] | > 50 [23] | Unit mass resolution, limited accuracy without advanced calibration. |

| Time-of-Flight (TOF) | 10,000 - 60,000 [6] | 1 - 5 [23] | Good for fast chromatography, moderate to high resolution. |

| FT-Orbitrap | Up to 100,000 - 500,000+ [6] | 1 - 3 [23] | High resolution and accuracy, widely used in proteomics/metabolomics. |

| FT-ICR | Up to 1,000,000 - 20,000,000+ [10] [6] | < 1 - 1 [10] | Highest available broadband resolution and sub-ppm accuracy. |

Note: Resolving power and mass accuracy are highly dependent on specific instrument model, acquisition speed, and tuning.

From Theory to Practice: Techniques to Enhance Resolution and Accuracy in Your HRMS Workflows

Optimizing Ion Source Conditions for Improved Ionization Efficiency

In high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), the ability to distinguish between molecules with nearly identical mass-to-charge ratios (m/z)—such as cysteine (121.0196) and benzamide (121.0526)—fundamentally depends on two key concepts: mass resolution and mass accuracy [25]. While excellent mass resolution allows the instrument to separate these closely spaced peaks, achieving reliable and precise mass accuracy is profoundly dependent on the quality of the ion signal, which originates at the ion source [25]. Ionization efficiency, defined as the proportion of analyte molecules successfully converted into gas phase ions, therefore serves as a critical foundation for all subsequent measurements [26]. Low ionization efficiency not only limits sensitivity and the ability to detect trace-level components but can also adversely impact the precision of mass accuracy by reducing the signal-to-noise ratio for the molecular ions used in exact mass determination [26]. This technical guide explores the optimization of various ion source conditions, providing detailed methodologies and data to enable researchers to systematically improve ionization efficiency, thereby unlocking the full quantitative and qualitative potential of HRMS within pharmaceutical and bioanalytical research.

Theoretical Foundations of Ionization

Fundamental Ionization Processes

Ionization techniques in mass spectrometry can be broadly classified into two categories: hard and soft ionization [27]. Hard ionization methods, such as Electron Ionization (EI), impart high internal energy to analyte molecules, resulting in extensive fragmentation that provides valuable structural information but often yields a weak or non-existent molecular ion signal [27]. In contrast, soft ionization techniques, including Electrospray Ionization (ESI) and Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI), impart less internal energy, predominantly generating intact molecular ions (e.g., [M+H]⁺ or [M-H]⁻) with little fragmentation, which is crucial for determining molecular weight and for analyzing large, non-volatile biomolecules [27].

The underlying physics of ionization is governed by fundamental equations. In thermal ionization, the degree of ionization (α) is described by the Saha-Langmuir equation:

α = n_i/n_o = g exp[e(φ - I)/kT]

where n_i/n_o is the ion-to-neutral ratio, g is a statistical constant, e is the electron charge, φ is the work function of the ionizing surface, I is the ionization potential of the analyte, k is Boltzmann's constant, and T is the temperature [28]. This equation highlights that ionization efficiency can be enhanced by using a surface material with a high work function and by operating at elevated temperatures, particularly for elements with low ionization potentials [28].

Ion Source Technologies and Their Mechanisms

Different ion sources operate on distinct principles, making them suitable for specific applications. The following table summarizes key ionization techniques and their characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Ionization Techniques in Mass Spectrometry

| Ionization Technique | Ionization Mechanism | Optimal Analytes | Fragmentation Level | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospray Ionization (ESI) [27] | Electrospray produces charged droplets that undergo desolvation and Coulomb fission to yield gas-phase ions. | Polar molecules, large biomolecules (proteins, peptides), and non-volatile compounds. | Very low (Soft) | Analysis of peptides, proteins, nucleotides; coupling with LC. |

| Electron Ionization (EI) [27] | High-energy electrons interact with gas-phase analyte molecules, causing electron ejection and fragmentation. | Organic compounds < 600 Da; volatile and thermally stable compounds. | Very high (Hard) | Structural elucidation of unknowns; environmental, forensic, and pharmaceutical analysis. |

| Thermal Ionization (TIMS) [28] | Sample is heated on a high-work-function metal surface (e.g., Re) to induce surface ionization. | Elements, particularly lanthanides and actinides (U, Pu); isotopic analysis. | Low | Precise isotopic abundance measurement; nuclear forensics, geochronology. |

| Dielectric Barrier Discharge (e.g., FμTP) [29] | A noble gas (He, Ar) is excited by a high-voltage AC to form a low-temperature plasma that ionizes the analyte. | Broad coverage, including both polar and non-polar pesticides and contaminants. | Low (Soft) | Target and non-target screening of multiclass contaminants; LC-MS and ambient ionization. |

| Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) [27] | A corona discharge creates reagent ions from the solvent, which subsequently ionize the analyte via gas-phase reactions. | Low to medium polarity, thermally stable compounds. | Low (Soft) | Analysis of drugs, pesticides, and various organic compounds. |

Key Parameters for Ion Source Optimization

Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Parameters

Optimizing an ESI source is critical for maximizing sensitivity, especially when dealing with complex matrices like biological samples. The key parameters, often referred to as the "source gas and temperature settings," work in concert to stabilize the spray and efficiently generate gas-phase ions [30] [31].

- Source Gas 1 (GS1) functions primarily as a nebulizing gas, breaking the liquid stream emerging from the capillary into a fine aerosol of charged droplets [30].

- Source Gas 2 (GS2) is a drying or auxiliary gas that typically flows concentrically around the spray. It assists in desolvation by transferring heat from the side heaters into the spray core, helping to evaporate the solvent from the charged droplets [30].

- Temperature (TEM) sets the temperature of the heaters that warm GS2. Increased temperature facilitates the desolvation process but must be balanced to avoid thermally degrading the analyte [30].

- Curtain Gas (CUR) acts as a barrier gas flowing between the curtain plate and the orifice plate. It serves two main purposes: it prevents solvent and neutral contaminants from entering the vacuum system, and it helps decluster solvated ions by collisional activation before they enter the mass analyzer [30].

Systematic tuning of these parameters is essential. A common strategy involves infusing a standard solution of the target analyte and sequentially adjusting GS1, GS2, TEM, and CUR while monitoring the signal intensity (Total Ion Current or a specific MRM transition) to find the optimal combination for maximum response [31].

Thermal Ionization Source Parameters

For Thermal Ionization Mass Spectrometry (TIMS), optimization revolves around the properties of the source cavity and the heating protocol.

- Cavity Material: The choice of material is paramount. Rhenium (Re) is often preferred due to its high work function (φ), which, according to the Saha-Langmuir equation, directly enhances the ionization efficiency for a given element [28].

- Cavity Geometry: Confined cavity structures (e.g., tubular designs) significantly increase ionization efficiency compared to flat filaments. This is because analyte atoms undergo multiple interactions with the hot cavity walls, increasing the probability of ionization [28].

- Temperature Profile: Precise control of the heating current and temperature is required. The temperature must be high enough to efficiently vaporize and ionize the sample but controlled to prevent rapid evaporation and sample exhaustion before data acquisition [28]. Experimental studies have shown that establishing an optimal temperature gradient is crucial for obtaining stable ion beams of elements like Sr, Sm, Lu, Yb, and U [28].

Electron Impact and Plasma Source Parameters

- Cathode Material: In Electron Impact (EI) sources, the thermionic emission current density (

J_R) is governed by the Richardson equation:J_R = AT^2 exp(-Φ/k_B T). Therefore, selecting a cathode material with a low work function (Φ) and high melting point, such as Y₂O₃-coated iridium, allows for a higher electron emission current at a given temperature, thereby increasing the probability of ionization events [32]. - Discharge Gas: In plasma-based sources like Flexible microtube Plasma (FμTP), the nature of the discharge gas (e.g., Helium or Argon) influences the ionization mechanism and efficiency [29]. While helium is common, argon and argon-propane mixtures are effective, cost-efficient alternatives that avoid potential issues associated with helium depletion and its impact on turbopumps [29].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

Protocol: Optimizing a Tubular Cavity Ion Source

The following workflow, adapted from research on a high-efficiency cavity ion source, provides a methodology for qualifying and optimizing a thermal ionization source [28].

Diagram 1: Cavity Ion Source Optimization Workflow

1. Source Assembly and Preparation: The cavity ion source is assembled with a cylindrical Rhenium cavity tube and a Tantalum heating filament. The sample is loaded into the cavity via a sampler tube [28].

2. Vacuum and Power Setup: The system is evacuated to a base pressure below 5×10⁻⁷ mbar. The Ta filament is connected to a DC current power supply (e.g., 12.5V/120 A), and a high-voltage power supply (e.g., -2500 V) is connected to electrically float the filament for ion extraction [28].

3. Heating and Data Acquisition: The filament is heated gradually to establish a stable temperature gradient. With the cavity operating at high temperature, a quadrupole mass analyzer (QMA) is used to perform full mass scans (e.g., m/z 1-250) to characterize the ion output. The signals for target elements (e.g., Boron, Strontium, Samarium, Lutetium, Ytterbium, Uranium) are recorded at their established optimum emission currents [28].

4. Performance Comparison: The ion signals obtained from different cavity geometries (e.g., Cavity-1 with L/D=25 and Cavity-2 with L/D=20) are directly compared. The sensitivity is calculated, and the superiority of one design over the other is quantified, often showing a factor of 2-3 improvement for a cavity with a higher Length-to-Diameter (L/D) ratio [28].

Protocol: Evaluating ESI Ion Utilization Efficiency

This protocol describes a method to quantitatively evaluate the overall performance of an ESI-MS interface, measuring the proportion of analyte molecules that are successfully converted into gas-phase ions and transmitted to the detector [26].

1. Standard and MS Preparation: A peptide mixture (e.g., 1 µM of each peptide in 0.1% formic acid in 10% acetonitrile) is prepared. The mass spectrometer is fitted with the interface to be tested (e.g., a single inlet capillary, a multi-inlet capillary, or a SPIN - Subambient Pressure Ionization - interface) [26].

2. Current and Spectral Measurement: - The total electric current transmitted through the interface is measured by using a low-pressure ion funnel as a charge collector, connected to a picoammeter. - Simultaneously, mass spectra are acquired (e.g., over 1 minute in positive ion mode, m/z 200-1000) to obtain the total ion current (TIC) and the extracted ion current (EIC) for specific analytes [26].

3. Data Analysis and Efficiency Calculation: The ion utilization efficiency is assessed by correlating the measured transmitted electric current with the observed analyte ion intensity in the mass spectrum. A more efficient interface will show a higher ratio of detected ion current (in the mass spectrum) to total transmitted electric current, indicating superior conversion of the charged cloud into desolvated, transmission-ready ions [26].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The following tables synthesize quantitative data from optimization studies across different ionization techniques.

Table 2: Performance Gains from Cavity Ion Source Optimization [28]

| Optimization Parameter | Baseline/Comparison | Optimized Result | Impact on Ionization Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cavity Material | Conventional Filament (Tungsten) | Rhenium (Re) Cavity | Increased due to higher work function of Re. |

| Cavity Geometry (L/D Ratio) | Cavity-2 (L/D = 20) | Cavity-1 (L/D = 25) | 2-3 times higher signal for actinides/lanthanides. |

| Ion Source Type | Conventional Thermal Ion Source (TIS) | Tubular Cavity Ion Source (CIS) | Superior sensitivity for wide IP range elements. |

Table 3: Sensitivity and Matrix Effect Comparison for LC-MS Ionization Sources [29]

| Ion Source | Discharge Gas | Pesticides with Higher Sensitivity (vs. ESI) | Pesticides with Negligible Matrix Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrospray (ESI) | Not Applicable | Baseline (0%) | 35% - 67% |

| APCI | Not Applicable | Not Reported | 55% - 75% |

| Flexible microtube Plasma (FμTP) | Helium | 70% | 76% - 86% |

| FμTP | Argon / Argon-Propane | Similar LOQs for ~90% of pesticides (vs. He-FμTP) | Similar robust performance to He-FμTP |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Materials for Ion Source Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Rhenium (Re) Cavity Tube | High-work-function material for thermal ionization sources; enhances ionization yield for lanthanides/actinides. | >99.9% purity Re tube used in tubular cavity source [28]. |

| Y₂O₃-Coated Iridium Filament | Cathode for EI sources; low work function enables high electron emission current for increased ionization. | Used in a high-efficiency electron impact ion source for planetary MS [32]. |

| Etched Fused Silica Emitter | Nano-electrospray emitter for ESI-MS; provides stable, high-efficiency ionization at low flow rates. | Capillaries (O.D. 150 µm, I.D. 10 µm) chemically etched for ESI and SPIN interfaces [26]. |

| High-Purity Discharge Gases | Medium for sustaining plasma in DBD-based ion sources (e.g., FμTP). | Helium (99.9999%), Argon (99.999%), Argon-Propane mix [29]. |

| Volatile LC-MS Buffers | Mobile phase additives for stable electrospray and efficient ionization. | Ammonium acetate, ammonium formate [31]. |

Interplay with Mass Resolution and Accuracy

The optimization of ionization efficiency is not an isolated goal but a prerequisite for achieving high-quality mass resolution and accuracy, particularly in HRMS. A strong, stable ion signal resulting from high ionization efficiency directly improves the signal-to-noise ratio (S/N). This enhanced S-Ratio allows the mass analyzer to more accurately define the centroid of an ion's mass-to-charge peak, which is the fundamental measurement underlying exact mass determination [25] [26]. Furthermore, efficient and soft ionization techniques like ESI and FμTP primarily generate intact molecular ions (e.g., [M+H]⁺), which are the essential species for obtaining an accurate molecular weight [29] [27]. Excessive fragmentation or a weak molecular ion signal complicates or precludes this measurement. Techniques that reduce matrix effects, such as FμTP, further support mass accuracy by minimizing ion suppression, which can distort peak shapes and shift apparent mass, thereby ensuring that the measured signal accurately reflects the true isotopic distribution and centroid of the analyte [29] [31]. The relationship between source conditions and final data quality is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Ion Source Impact on Mass Accuracy