Mastering Spectral Overlap: Strategies for High-Parameter Flow Cytometry Panel Design

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing spectral overlap in flow cytometry.

Mastering Spectral Overlap: Strategies for High-Parameter Flow Cytometry Panel Design

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing spectral overlap in flow cytometry. It covers the fundamental principles of spectral flow cytometry, detailing how full-spectrum detection and unmixing algorithms overcome the limitations of conventional compensation. The content explores practical methodologies for panel design, reagent selection, and blocking protocols, alongside advanced troubleshooting techniques for common errors. Finally, it examines validation frameworks and the comparative advantages of spectral cytometry in clinical and translational research, offering a complete resource for developing robust, high-parameter assays.

Understanding Spectral Overlap: From Conventional Limits to Spectral Solutions

Fundamental Definitions

What are spectral overlap and spillover in flow cytometry?

Spectral Overlap is the phenomenon where the emission spectrum (the range of light wavelengths a fluorophore emits) of one fluorophore overlaps with the emission spectrum of another [1]. Spillover is the concrete result of this overlap: the fluorescent signal from one fluorophore is detected in the optical channel (photodetector) intended for a different fluorophore [2] [3] [1].

This occurs because fluorophores do not emit light at a single, precise wavelength. Instead, they emit across a broad range of wavelengths [4]. When using multiple fluorophores in a single panel, their broad emission spectra inevitably overlap, causing one fluorophore's signal to "spill over" into another's detector [2].

Why is correcting for spillover so critical for accurate data?

Without correction, spillover can lead to false-positive results, making it appear that a cell expresses a marker that it does not [1]. This compromises the accuracy and reliability of your data [2]. The process of compensation is a mathematical correction applied to raw flow cytometry data to subtract the spillover signal from secondary channels, ensuring that the signal in each detector accurately reflects the expression of its intended target [1] [4].

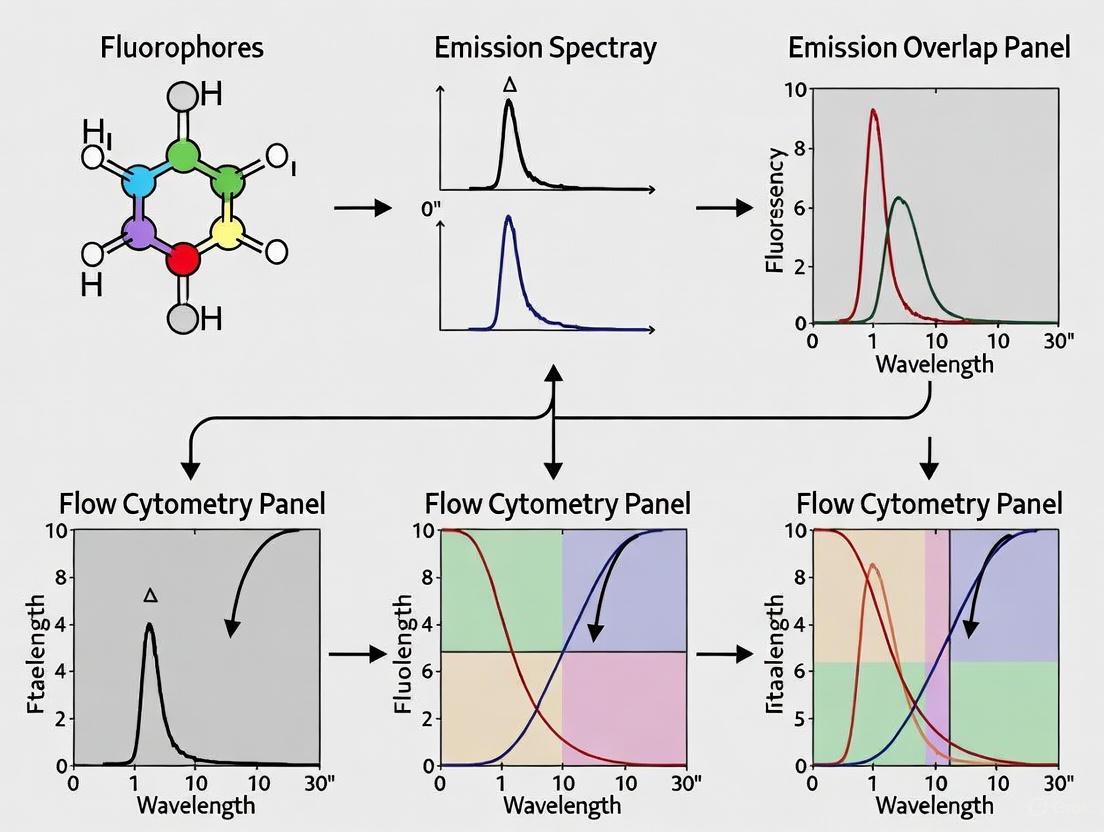

The diagram below illustrates the core concepts and their relationships:

Troubleshooting FAQs

The Problem: My fluorescence-minus-one (FMO) control shows a spread-out negative population, making it hard to set a clear gate. What is happening? This is likely spillover spreading, a phenomenon where the process of compensating for spillover introduces increased variance, causing the negative population to widen [3] [5]. This is not an error but a fundamental property of the compensation mathematics and the measurement error inherent in detecting fluorescence [5]. It is most pronounced when a bright fluorophore with high spillover is paired with a dim marker [3].

The Solution:

- Panel Redesign: For future experiments, use a spillover spreading matrix (SSM) during panel design to identify and avoid fluorophore combinations with high spillover, especially for co-expressed markers [3].

- Gating Adjustment: When analyzing current data, gate conservatively by following the contour of the spread population in your FMO control rather than drawing a tight gate that may include false positives.

The Problem: After compensation, my fully stained sample shows a population that is negative for all markers. Did I over-compensate? Yes, this is a classic sign of over-compensation [1]. This occurs when the software subtracts too much signal from a channel, creating artificial negative values [1].

The Solution:

- Verify Control Brightness: Ensure your single-stained compensation controls are at least as bright as, or brighter than, the sample you are compensating [2] [4]. Dim controls can lead to incorrect spillover calculations.

- Re-run Compensation: If controls are adequate, re-run the compensation calculation using automatic compensation tools if available, or manually adjust the over-compensated value downward [1].

The Problem: My data shows "smeared" populations that diagonal, and I cannot resolve clear positive and negative cells. This indicates under-compensation, where not enough spillover signal has been subtracted from the affected channel [1]. Residual spillover creates a correlated signal between two channels, causing the population to smear along a diagonal axis [4].

The Solution:

- Check Control Specificity: Confirm that your single-stain controls are pure and specific. A control contaminated with another fluorophore will provide an incorrect spillover value.

- Increase Compensation: Increase the compensation value for the culprit fluorophore into the affected channel until the median fluorescence of the positive and negative populations is aligned vertically (or horizontally) on the bi-axial plot [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Calculating and Applying Compensation Using Single-Stain Controls

Objective: To correct for spectral spillover in a multicolor flow cytometry experiment using single-stain controls.

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Single-Stain Controls: Cells or antibody-capture beads stained individually with each fluorophore-conjugated antibody used in your panel [1] [6].

- Unstained Control: Cells or beads with no fluorescent stain to measure autofluorescence and background [1] [6].

- Viability Dye: A fixable viability dye to exclude dead cells, which exhibit high nonspecific binding [7] [6].

- Fc Receptor Blocking Solution: To reduce nonspecific antibody binding [7] [6].

Methodology:

- Prepare Controls: For each fluorophore in your panel, prepare a dedicated tube of cells or compensation beads stained with only that fluorophore [1] [6].

- Match Experimental Conditions: Treat your compensation controls exactly like your experimental samples (same fixation, permeabilization, incubation time, and lot of reagents) [2] [1].

- Acquire Data: Run each single-stain control and the unstained control on the flow cytometer. Collect a sufficient number of events (at least 5,000 positive events for each control) for a statistically robust calculation [6].

- Perform Compensation: Use your flow cytometry software's automatic compensation tool. The software will calculate a spillover coefficient (the proportion of signal measured in a secondary detector relative to the primary detector) for each fluorophore pair and generate a compensation matrix [2] [1].

- Apply to Experimental Data: Apply the calculated compensation matrix to your fully stained experimental samples [1].

Protocol 2: Utilizing a Spillover Spreading Matrix (SSM) for Panel Design

Objective: To proactively assess and minimize the impact of spillover spreading during the design phase of a high-parameter flow cytometry panel.

Materials:

- Software Tool: A panel design platform with an integrated Spectra Viewer and SSM calculator (e.g., FluoroFinder, BD Spectrum Viewer) [3] [8].

Methodology:

- Input Instrument Configuration: Select your specific flow cytometer model within the software to define its laser and detector configuration [3] [8].

- Assign Fluorophores: Add the fluorophores you are considering for your panel to the virtual worksheet.

- Generate SSM: The software will generate an SSM, a table where each value represents the standard deviation of the spillover spreading error for each fluorophore pair [3].

- Analyze the Matrix:

- Identify combinations with high spillover spreading values (a general threshold is >10) [3].

- Avoid assigning high-spreading fluorophore pairs to markers that are co-expressed on the same cell population [3].

- Reassign fluorophores to minimize high values, prioritizing the separation of bright fluorophores from dim or co-expressed markers [3].

Advanced Concepts: The Shift to Spectral Flow Cytometry

How does spectral flow cytometry handle spillover differently? Conventional flow cytometry uses compensation to correct spillover after detection, while spectral flow cytometry uses spectral unmixing to identify fluorophores based on their full spectral signature [9].

- Conventional Cytometry: Uses optical filters to direct a limited portion of a fluorophore's emission to a single detector. Spillover is corrected mathematically via compensation [9].

- Spectral Cytometry: Collects the full emission spectrum (from ~350-900 nm) of every fluorophore across an array of detectors [9]. The instrument then uses a reference library of each fluorophore's unique spectral signature to "unmix" the combined signal from a cell, assigning the correct intensity for each fluorophore [9]. This allows for better resolution of fluorophores with overlapping peak emissions and can separate cellular autofluorescence as a distinct signal [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Managing Spectral Overlap |

|---|---|

| Antibody-Capture Beads | Provide a uniform, cell-free substrate for generating consistent single-stain compensation controls, eliminating biological variability [1]. |

| Fixable Viability Dyes | Allow for the identification and exclusion of dead cells during analysis, which reduces high background fluorescence that complicates spillover correction [7] [6]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Minimizes nonspecific antibody binding to Fc receptors on cells, reducing background signal and leading to cleaner compensation [7] [6]. |

| Tandem Dyes | Enable the use of more fluorophores on an instrument with a limited number of lasers by creating a distinct emission peak via FRET. Note: They can be prone to degradation and increased spillover [3]. |

| Spectra Viewer & Panel Builder | Online tools that allow visualization of fluorophore excitation/emission spectra and calculate spillover/spreading to optimize panel design before purchasing reagents [3] [8]. |

In conventional flow cytometry, the accurate detection of multiple fluorochromes is fundamentally challenged by spectral overlap. This occurs because fluorochromes emit light across a broad range of wavelengths, and their emission spectra frequently overlap. While compensation is a standard mathematical correction for this spillover, it has inherent limitations that can compromise data accuracy, especially in complex multicolor panels. Understanding these limitations and their associated troubleshooting strategies is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals relying on high-quality flow cytometry data.

FAQ: Understanding Compensation and Its Pitfalls

What is compensation and why is it necessary?

Compensation is a mathematical correction required in conventional flow cytometry to account for fluorescence spillover—the phenomenon where the emission of one fluorochrome is detected in the detector of another. This is necessary because fluorochromes do not emit light at a single perfect wavelength. Instead, they have an emission spectrum, often with a long "tail" that can be detected by photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) assigned to other fluorochromes [10]. For example, fluorescein (FITC) has a maximal emission at 524 nm, but its emission tail can extend beyond 600 nm, leading to detectable signal in the PE or other channels if not corrected [10]. Without compensation, it is impossible to make an accurate measurement of a single fluorochrome in the presence of multiple labels [10].

What are the most common errors that occur during compensation?

Common compensation errors often stem from issues with the single-color controls used to calculate the spillover values [11]. Key problems include:

- Inadequate Controls: Using controls that do not match the experimental samples, for example, using beads instead of cells, or using fixed controls for unfixed samples (and vice versa) [11].

- Poor Signal: Controls with weak positive signals or an insufficient number of positive events can lead to inaccurate compensation calculations [11].

- Autofluorescence: Cell autofluorescence, particularly in certain channels, can mix with the fluorophore signal and create a hybrid signal that is not properly accounted for during compensation [11] [12].

- Tandem Dye Degradation: Tandem dyes (e.g., PE-Cy7) can break down, causing a blue-shift in their emission spectrum. If the single-color control has not undergone the same degradation, the compensation matrix will be incorrect [11].

How can I identify a compensation error in my data?

The most characteristic visual signature of a compensation error is a skewed or correlated population in a two-parameter plot [11]. This often manifests as a "leaning" cloud of positive events, where an increase in fluorescence in one channel is accompanied by an artificial increase or decrease in another channel. A specific and common artifact is "hyper-negative" populations, where a compensated population appears below zero on the axis [11]. This is biologically implausible and indicates an over-correction for spillover.

What is "spreading error" and how is it different from a compensation error?

It is critical to distinguish between an incorrect compensation and spreading error.

- Compensation Error: A mistake in the calculation or application of the spillover correction, resulting in skewed or correlated data. This is often fixable with better controls [11].

- Spreading Error: An inherent, unavoidable consequence of the physics of fluorescence detection and the compensation process itself. It refers to the increase in the variance (spread) of a negative population in a detector that is receiving a large compensation value from a bright fluorochrome in another detector [12]. Unlike a compensation error, spreading error is symmetrical and cannot be eliminated by perfect compensation; it must be managed through careful panel design [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Compensation-Related Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Clues | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| No or Weak Signal [13] [14] [15] | Incorrect PMT voltage/Gain | All fluorochromes appear dim; signal is close to axis. | Run positive control and adjust voltage/gain. |

| Antibody degradation or incorrect storage | Signal is weak despite correct instrument settings. | Titrate antibody; use fresh aliquots. | |

| Inadequate permeabilization (intracellular staining) | Surface markers work, but intracellular do not. | Validate permeabilization protocol; include Triton X-100 [13]. | |

| High Background/Non-specific Staining [16] [14] | Overcompensation | Populations appear "hyper-negative". | Recalculate compensation with better single-stain controls [11]. |

| Fc receptor binding or antibody trapping | High background in multiple channels. | Add Fc receptor blocking step; optimize wash steps with detergent [16] [14]. | |

| Excessive antibody concentration | High fluorescence intensity but poor resolution. | Titrate antibodies to find optimal concentration. | |

| Skewed Populations (Compensation Error) [11] | Mismatched single-stain controls | Controls (beads/cells) do not match sample treatment. | Use biological single-stain controls that match sample prep. |

| Autofluorescence interference | High background in channels ~450-500nm and ~650-750nm. | Use FMO controls; consider automated autofluorescence extraction on spectral cytometers [12]. | |

| Tandem dye degradation | Sudden appearance of spillover errors in a previously working panel. | Use fresh tandem dyes; protect from light. | |

| Poor Resolution of Rare Populations [16] | Spreading error | Negative population is broadened in a channel receiving high compensation from a bright marker. | Re-design panel to avoid large compensation values on rare population markers. |

| Insufficient event collection | Statistics on rare population are noisy. | Acquire more total events; use high cell-loading concentrations. | |

| High background from dead cells/debris | False positives from autofluorescent debris. | Gate out dead cells and debris rigorously [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Accurate Compensation

Protocol 1: Generating Reliable Single-Color Controls

A robust compensation matrix hinges on high-quality single-color controls [10] [11].

Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions:

- Viability Dye: To exclude dead cells (e.g., DAPI, Propidium Iodide).

- Fc Receptor Blocking Solution: To reduce non-specific binding (e.g., purified human or mouse IgG).

- UltraComp eBeads: Alternatively, compensation beads for surface markers.

- Positive Control Cells: Cells known to express the target antigen at a high level.

- Fixation/Permeabilization Buffer: If staining intracellular targets.

Methodology:

- Match Your Samples: Controls must be subject to the exact same protocols as test samples, including fixation, permeabilization, and incubation times [11].

- Use Biological Controls: While beads are stable, single-stained cells are often preferable as they account for cell autofluorescence and antibody-specific binding characteristics [11].

- Ensure Brightness: The positive population in the control should be several logs brighter than the negative population to ensure an accurate calculation of the spillover value [11].

- Acquire Sufficient Events: Collect enough positive events (at least a few hundred) for a robust statistical calculation [11].

- Avoid Mix-Ups: Carefully label all controls to prevent using the wrong single-color control for a channel.

Protocol 2: Using FMO Controls to Validate Gating and Reveal Spreading Error

Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) controls are essential for setting gates for dim markers and visualizing the effects of spreading error [11].

Methodology:

- Prepare the Control: Stain the sample with all antibodies in the panel except one.

- Set Gates: Use the FMO control to set the positive gate for the omitted antibody. This reveals how spreading error and background affect the negative population in a real-sample context.

- Troubleshoot: If the staining in the full panel does not match the pattern expected from the FMO, this indicates a potential panel design flaw or compensation issue.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents for Managing Spectral Overlap

| Item | Function in Experiment | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Compensation Beads | Provide a uniform, bright positive signal for setting compensation without using cells. | Ideal for stable surface markers. Cannot account for cellular autofluorescence [11]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Solution | Blocks non-specific antibody binding to Fc receptors on immune cells, reducing background. | Critical for staining immune cells from blood, spleen, or lymph nodes [16]. |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live from dead cells. Dead cells have high autofluorescence and non-specific antibody binding. | Essential for gating and excluding artifacts that complicate compensation [16]. |

| Bright Fluorophores (e.g., PE, APC) | Used for detecting markers with low expression levels. | Pairing a dim marker with a bright fluorophore improves resolution and simplifies compensation [13]. |

| Tandem Dyes (e.g., PE-Cy7, APC-Cy7) | Combine a donor fluorophore with an acceptor to create new emission profiles, expanding panel size. | Prone to degradation; batch variability and instability can cause major compensation shifts [11]. |

| FMO Controls | Used to accurately set gates for dim markers and visualize the impact of spreading error. | The gold standard for validating gating strategies in multicolor panels [11]. |

Visualizing the Compensation Process and Its Challenges

The following diagram illustrates the core principles of fluorescence spillover and the mathematical compensation process in conventional flow cytometry.

Figure 1. The principle of fluorescence spillover and compensation. Fluorophores emit light across a broad spectrum, leading to spillover into non-primary detectors. The observed signal is a mixture, which compensation aims to correct using a spillover matrix to calculate the actual fluorescence.

The limitations of filter-based detection and compensation become especially apparent when compared to the spectral approach, as shown below.

Figure 2. A comparison of conventional and spectral flow cytometry architectures. The conventional system's filter-based detection and "one detector-one fluorophore" model is inherently limited and prone to spreading error. In contrast, spectral cytometry captures the full emission spectrum, enabling superior unmixing of complex fluorophore combinations.

Core Concepts FAQ

What constitutes the fundamental difference between spectral and conventional flow cytometry?

The fundamental difference lies in how fluorescence signals are detected and resolved. Conventional flow cytometry uses a limited number of detectors per laser to measure only the peak emission of each fluorochrome. Its ability to multiplex dyes with overlapping emission spectra is restricted and complicated by compensation procedures [17]. In contrast, spectral flow cytometry uses multiple detectors to capture the entire fluorescence emission spectrum for each fluorochrome across multiple laser lines. This allows for more precise signal unmixing via algorithms, even between dyes with highly overlapping emissions, enabling the simultaneous analysis of a greater number of parameters [17].

How does algorithmic unmixing enhance the detection of dimly expressed markers?

Algorithmic unmixing enhances detection by characterizing and extracting autofluorescence (AF) signals using the same linear unmixing algorithms employed in fluorochrome identification [17]. The extraction of AF minimizes background noise compared to conventional flow cytometry. Furthermore, the integration of more sensitive detectors in spectral technologies significantly enhances the resolution of cell populations in multiparametric assays. This combined approach improves the overall accuracy and clarity of results, which is particularly beneficial for detecting markers expressed at low levels [17].

What are the primary clinical and research applications empowered by this technology?

Spectral flow cytometry is redefining clinical diagnostics and research, particularly in hematologic malignancies and immunological disorders [17].

- Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Detection: It allows for high-resolution quantification of leukemic burden with high sensitivity using single-tube assays, which is critical for risk assessment and guiding treatment decisions [17].

- Comprehensive Immune Profiling: Its high-parameter capability supports deep phenotyping for biomarker discovery and therapy monitoring, such as tracking CAR-T cell kinetics and profiling T-cell exhaustion in immuno-oncology [17].

- Drug Discovery & Clinical Trials: Pharma and CROs use it for enhanced pharmacodynamic biomarker monitoring and discovery, especially in scenarios with limited specimen availability like bone marrow aspirates or pediatric biopsies [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Resolution after Unmixing (High Background/Spreading)

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| High Autofluorescence | Use fresh cells or cells fixed for a short period. Run matching unstained cells to assess autofluorescence levels [18]. | Autofluorescence from aged or poorly handled cells contributes significantly to background noise, interfering with unmixing algorithms. |

| Spectral Spillover Spreading | Utilize a spectrum viewer during panel design to select fluorochromes with minimal spectral overlap. Pair dim markers with bright fluorochromes and highly expressed antigens with dimmer fluorochromes [18] [19] [20]. | Spillover spreading is caused by measurement errors from multiple fluorochromes spilling into each other's detectors, which can mask dim positive populations [18]. |

| Inadequate Controls for Unmixing | Ensure single-stained controls for each fluorochrome are as bright or brighter than the fully stained sample. Use the same fluorophore in controls and experiments, and treat them identically (e.g., same fixative) [21]. | The unmixing algorithm relies on reference controls to build a spectral library. Incorrect controls lead to inaccurate unmixing and data artifacts. |

| Polymer Dye Instability | When using more than one polymer dye (e.g., Brilliant Violet dyes), include a specific polymer stain buffer in your staining protocol to prevent dye-dye interactions [21]. | Without a stabilizer, some polymer dyes can stick together, forming aggregates that alter their spectral signature and cause unmixing errors. |

Spectral Unmixing Troubleshooting Workflow

Issue: Weak or Absent Fluorescence Signal

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Low Antigen Abundance or Accessibility | For intracellular targets, ensure adequate fixation and permeabilization. For surface antigens, keep cells on ice during processing to prevent internalization. Use a Golgi-block step (e.g., Brefeldin A) for secreted proteins like cytokines [18] [15]. | The target protein may not be present, may be expressed at low levels, or may be inaccessible to the antibody due to its subcellular location. |

| Suboptimal Antibody Titration | Titrate the antibody concentration for your specific cell type and experimental conditions. A concentration that is too low will yield a weak signal [18]. | Although an antibody may be validated for flow cytometry, the optimal concentration can vary based on cell type and antigen density. |

| Fluorochrome-Conjugate Issues | For intracellular staining, use fluorochromes with a low molecular weight to improve cell entry. Protect samples from light to prevent photobleaching [15]. | Large fluorochrome conjugates can reduce antibody motility, preventing access to intracellular epitopes. Fluorochromes can fade upon light exposure. |

| Instrument Laser Misalignment | Run calibration beads to check instrument performance. Ensure lasers are aligned correctly for optimal excitation [18] [15]. | Misaligned lasers result in inefficient excitation of fluorochromes, leading to a weak emitted signal. |

Issue: Unmixing Errors and Data Artifacts

This issue manifests as events appearing below zero on plots or populations skewed into the negative region [21].

Diagnostic Protocol:

- Identify Error Scope: Determine if the unmixing error exists in both the fully stained tube and the single-stained control tube, or only in the fully stained tube [21].

- If errors exist in both controls and full stains:

- Recalculate Unmixing: The most likely cause is an error in setting up the unmixing algorithm. Revisit the software setup to ensure the correct single-stained controls are assigned to their corresponding fluorochrome channels and that gating for the calculation was accurate [21].

- Verify Control Quality: Ensure the autofluorescence of the positive particles in the control is appropriately matched to the negatives, especially when using a mix of cells and beads [21].

- If errors exist only in full stains:

- Check Control Brightness: The single-stained control must be as bright or brighter than the corresponding signal in the fully stained sample. Compare the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) [21].

- Ensure Treatment Consistency: The single-stained controls and fully stained samples must be treated identically (e.g., the same fixation protocol, same buffer additives). Fixative can slightly alter a fluorophore's emission spectrum [21].

- Inspect Polymer Dyes: If using polymer dyes without a dedicated stain buffer, dye-dye interactions may be causing aggregation and spectral shifts, not a pure unmixing error [21].

Resolution: For errors related to control setup or treatment inconsistency, new controls must be made that strictly follow the rules. For polymer dye aggregation, new samples must be stained with the appropriate stain buffer added [21].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Standard Operating Procedure: High-Parameter Intracellular Cytokine Staining

This protocol is typical for immune functional assays, such as characterizing T-cell responses [22].

Intracellular Staining Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

Cell Stimulation & Secretion Block:

Surface Antigen Staining:

- Harvest and wash cells.

- Block Fc Receptors to prevent non-specific antibody binding using a commercial blocking reagent [18] [20].

- Stain with a cocktail of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against surface markers (CD3, CD4, CD8, etc.).

- Keep cells on ice and use ice-cold buffers during this and all subsequent steps to halt internalization and modulation of surface antigens [18] [15].

Fixation & Permeabilization:

- Fix cells with a formaldehyde-based fixative (e.g., 4% formaldehyde for no more than 30 minutes). Over-fixation can diminish fluorescence signals [18].

- Permeabilize cells using a mild detergent (e.g., Saponin, Triton X-100) to allow antibodies access to the interior of the cell. For nuclear antigens, more vigorous detergents may be required [18].

Intracellular Staining:

- Stain with a cocktail of fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies against intracellular targets (e.g., cytokines like IFN-γ, IL-17, or transcription factors).

- Use low molecular weight fluorochromes (e.g., Alexa Fluor dyes) for better intracellular mobility [15].

- Include adequate washing steps with permeabilization buffer to remove trapped, unbound antibody [18].

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire data on a spectral flow cytometer.

- Use calibration beads to ensure optimal instrument performance before running samples [18].

Quantitative Data from Clinical Applications

The table below summarizes the performance of spectral flow cytometry in detecting Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) across various hematologic malignancies, demonstrating its high sensitivity and clinical utility [17].

| Disease | SFC Panel Design | Achieved MRD Sensitivity | Key Clinical Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-Cell Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (B-ALL) | 23-color panel | ~10⁻⁵ (0.001%) | Enhanced detection of dim antigens and CD19-negative leukemic clones post-therapy [17]. |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | 24-color to 27-color single-tube assay | Down to 0.02% | High-resolution profiling of blast maturation; eliminates need for sample splitting [17]. |

| Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) & Lymphoma | Panels with CD5, CD19, CD20, CD23, CD79b, ROR1 | As low as 0.005% | Increased specificity and improved detection of rare malignant clones [17]. |

| Multiple Myeloma | EuroFlow NGF markers in a single-tube assay | ~10⁻⁶ (0.0001%) | Clear distinction of clonal vs. normal plasma cells; supports standardized MRD endpoints [17]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Reduces non-specific antibody binding via Fc receptors on myeloid cells and others, lowering background [18] [20]. | Essential for staining in human samples and highly recommended for mouse samples to improve signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Protein Transport Inhibitors (Brefeldin A/Monensin) | Blocks Golgi-mediated export, trapping secreted proteins (e.g., cytokines) inside the cell for intracellular detection [18] [22]. | Required for any intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) assay. |

| Viability Dye | Distinguishes live from dead cells. Dead cells bind antibodies non-specifically, contributing to high background [18]. | Crucial for accurate analysis, especially when processing tissue samples or using cryopreserved cells. |

| Polymer Stain Buffer | Prevents non-specific interactions and aggregation between polymer-based dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet dyes) when used in the same panel [21]. | Mandatory when using two or more polymer dyes in a single panel to avoid aberrant data. |

| Antibody Capture Compensation Beads | Used to generate consistent and bright single-stained controls for setting up unmixing/compensation, especially for rare markers [18]. | Ensure the beads are compatible with the antibody host species. Treat beads with the same fixative as samples. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a spectral flow cytometer and a conventional one? The core difference lies in the detection system. Conventional flow cytometers use optical filters and dichroic mirrors to direct narrow bands of light, typically matching a fluorophore's emission peak, to dedicated detectors (the "one detector–one fluorophore" approach). In contrast, spectral cytometers collect the full emission spectrum of every fluorophore across a wide wavelength range. They use a prism or diffraction grating to scatter the light, which is then captured by an array of detectors (often 32-64 or more) [23] [24]. This allows spectral cytometry to distinguish fluorophores based on their entire spectral "fingerprint," not just a single peak.

Q2: How does spectral cytometry improve resolution and facilitate high-parameter panels? Spectral cytometry enhances resolution through spectral unmixing. This computational process analyzes the full spectrum from each cell and deconvolutes the individual contributions of all fluorophores present, even if their emission spectra significantly overlap [23]. This capability directly enables high-parameter flexibility, as it allows researchers to use many more fluorophores in a single panel—up to 40 or more—by leveraging dyes with overlapping but distinct spectral profiles that would be impossible to separate on a conventional cytometer [23] [24].

Q3: Can spectral flow cytometry really extract and use autofluorescence? Yes, this is a significant advantage. All cells have endogenous autofluorescence, primarily from molecules like NADH and FAD, which have characteristic spectral signatures [25]. In conventional cytometry, this autofluorescence contributes broadly to background noise. Spectral cytometry can unmix and subtract this autofluorescence signal from the total signal, improving the signal-to-noise ratio for specific markers [25]. Furthermore, researchers can now probe these intrinsic autofluorescence signals to gain direct insights into cellular metabolic states [25].

Q4: Why do I see unexpected signals or errors in my high-parameter spectral data? Even with spectral unmixing, data quality can be affected by several factors related to reagent interactions:

- Dye-Dye Interactions: Polymer dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet stains) can stick together, creating aberrant signals. This is mitigated by using specific polymer stain buffers [26] [21].

- Tandem Dye Degradation: Tandem dyes are prone to breakdown, which can cause the acceptor fluorophore to detach. This leads to erroneous signals from the donor fluorophore alone, which can be misassigned to a different marker in your panel [26] [24].

- Fc Receptor Binding: Antibodies can bind non-specifically to Fc receptors on cells, increasing background. This is reduced by blocking with normal serum from the same species as the staining antibodies [26].

Troubleshooting Guide

Issue 1: High Background or Non-Specific Staining

| Possible Cause | Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Fc Receptor Mediated Binding | Incubate cells with a blocking solution containing normal serum (e.g., rat and mouse serum) for 15 minutes at room temperature before adding staining antibodies [26]. | Blocks low-affinity interactions between antibodies and Fc receptors on immune cells, improving specificity [26]. |

| Polymer Dye Interactions | Include a commercial Brilliant Stain Buffer or similar in your surface antibody master mix when using two or more polymer dyes [26] [21]. | Prevents dye-dye interactions that cause non-specific signal and data skewing [26]. |

| Tandem Dye Instability | Use tandem stabilizer in your staining buffer and resuspension buffer. Protect stained samples from light [26]. | Stabilizes the chemical bond between the donor and acceptor fluorophores in tandem dyes, preventing degradation and spectral spillover [26]. |

| Inadequate Washing | Ensure thorough washing steps with buffers that may include detergents (e.g., Tween) to remove excess, unbound antibody [15]. | Removes trapped or unbound antibody that contributes to high background, particularly in intracellular staining [15]. |

Issue 2: Poor Unmixing Quality or Incorrect Population Identification

| Possible Cause | Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Single-Color Controls | Use single-color controls that are at least as bright as your fully stained sample and are treated identically (including fixation). Always use the exact same antibody-fluorophore conjugate for the control as in your panel [21]. | The unmixing algorithm requires a high-quality reference spectrum from each fluorophore. Dim or improperly treated controls provide a poor reference, leading to unmixing errors [21]. |

| Spectral Spillover from Autofluorescence | When designing your panel, account for cell autofluorescence. Use the autofluorescence signal as a separate "fluorophore" during unmixing to subtract it from your specific signals [25]. | Treating autofluorescence as a defined component allows the software to mathematically separate it from the signals of your specific markers, improving accuracy [25]. |

| Tandem Dye Breakdown | Check the integrity of your tandem dyes. If breakdown is suspected, replace the reagent and ensure proper handling and storage [26]. | A degraded tandem dye emits a spectrum that no longer matches its reference control, causing the unmixing algorithm to fail and assign signal to the wrong channel [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents for optimizing spectral flow cytometry experiments, as referenced in the protocols and troubleshooting guides above.

| Reagent | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Sera (e.g., Rat, Mouse) | Blocks non-specific binding via Fc receptors to reduce background staining [26]. | The serum should ideally be from the same species as the host of your primary antibodies [26]. |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer (BSB) | Prevents non-specific interactions between polymer dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet dyes) in a panel [26] [21]. | Essential when using more than one polymer dye in a panel. Not required for single-stain controls [26]. |

| Tandem Stabilizer | Protects susceptible tandem dyes from degradation during staining and sample acquisition [26]. | Improves data quality and reproducibility by maintaining the spectral integrity of tandem dyes [26]. |

| CellBlox | A blocking buffer specifically formulated for use with NovaFluor dyes [26]. | We do not cover its optimized usage here, as it requires specific optimization per manufacturer instructions [26]. |

| Sodium Azide | Prevents internalization and modulation of surface antigens, preserving fluorescence intensity [15]. | Highly toxic. Requires appropriate safety handling. Can be omitted for short-term protocols [26] [15]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Diagram: Spectral Unmixing Workflow

Strategic Panel Design and Practical Protocols for Minimizing Spillover

In multicolor flow cytometry, the accurate resolution of distinct cell populations hinges on a core principle: the careful pairing of fluorophore properties with the biological characteristics of the target antigens. Two factors are paramount: matching the brightness of the fluorophore to the abundance of the antigen, and ensuring spectral distinguishability between all fluorophores in the panel. Neglecting these principles can lead to poor resolution, inaccurate data, and failed experiments. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help you navigate these critical aspects of panel design.

Fluorophore Brightness and Antigen Abundance: A Quantitative Guide

The key to maximizing signal resolution is to assign the brightest fluorophores to antibodies targeting low-abundance antigens, and weaker fluorophores to highly expressed markers. This strategy prevents weak signals from being lost and avoids saturation of detectors by very strong signals.

The table below summarizes the relative brightness of common fluorescent proteins and organic dyes as reported in the literature, providing a reference for your panel design.

Table 1: Relative Brightness of Example Fluorophores for Flow Cytometry

| Fluorophore | Type | Excitation Laser (nm) | Emission Peak (nm) | Relative Brightness/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus | Fluorescent Protein | 488-514 | 528 | High signal-to-noise ratio; suitable for low-level expression [27] |

| mTagBFP2 | Fluorescent Protein | 405 | 454 | High signal-to-noise ratio; minimal spectral overlap [27] |

| TagRFP657 | Fluorescent Protein | 561-640 | 657 | High signal-to-noise ratio; compatible with NIR detection [27] |

| EGFP | Fluorescent Protein | 488 | 507 | Gold standard; widely used but may be superseded by newer proteins [27] |

| tdTomato | Fluorescent Protein | 561 | 581 | Very bright; but is a tandem dimer, not a monomer [27] |

| Spark PLUS Dyes | Organic Dye | Varies by specific dye | Varies by specific dye | Designed for enhanced brightness [23] |

| Brilliant Violet 421 | Polymer Dye | 405 | 421 | Very bright; common choice for high-impact markers [28] |

| APC | Phycobiliprotein | 640 | 660 | Bright; common choice for high-impact markers [28] |

| FITC | Organic Dye | 488 | 519 | Less bright; suitable for highly expressed antigens [28] [23] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Fluorophore Selection and Panel Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Monomeric Fluorescent Proteins | Genetic reporters for knock-in gene-expression or fusion-protein constructs [27]. | Creating stable cell lines or reporter mice for multicolor tracking. |

| Viability Dyes | Distinguish and exclude dead/dying cells from analysis to prevent nonspecific antibody binding [28]. | Live/dead discrimination in immunophenotyping panels (e.g., LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell stains). |

| Amine-Reactive Barcoding Dyes | Label individual cell samples for pooling, reducing staining variation and acquisition time [29]. | Multiplexing multiple samples in a single tube for phospho-flow or cytokine staining. |

| Tandem Dyes | Conjugates of a donor fluorophore and an acceptor molecule that allow for large Stokes shifts [23]. | Expanding the palette of colors available for a single laser line (e.g., PE-Cy7, APC-Cy7). |

| Single Color Reference Controls | Individually stained samples used to create spectral signatures for unmixing or compensation [30]. | Essential for setting up both spectral unmixing and conventional compensation. |

| Fixatives | Preserve cell state and stabilize fluorescent signals for later analysis [30]. | Preparing fixed single-color controls; 0.5% formaldehyde may stabilize some tandems for up to 5 days. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Panel Assembly and Validation

The following workflow provides a systematic methodology for designing, testing, and troubleshooting a multicolor flow cytometry panel.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Define Panel and Tier Antigens: List all target antigens and categorize them into tiers based on their expression levels (low/rare, medium, high/abundant) on your specific cell type [28].

- Theoretical Fluorophore Assignment:

- Assign your brightest fluorophores (e.g., BV421, APC) to detect low-abundance antigens [28].

- Assign medium-brightness fluorophores to antigens with medium expression.

- Assign your dim fluorophores (e.g., FITC) to detect highly abundant antigens [28].

- Use panel builder tools (e.g., FluoroFinder, instrument manufacturers' software) to visualize potential spectral conflicts and check reagent availability [28] [2].

- Experimental Validation:

- Prepare Single-Color Controls: For each fluorophore-antibody conjugate in your panel, stain cells or compensation beads to create a single-color control. Use a brightly stained population for accurate calculations [2] [30].

- Stain a Full-Panel Sample: Stain a test sample (e.g., PBMCs) with the complete antibody mixture.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Acquire data for all single-color controls and the full-panel sample on your flow cytometer.

- For conventional cytometers: Use the single-color controls to calculate spillover coefficients and apply compensation [2].

- For spectral cytometers: Use the single-color controls to create reference spectra and perform spectral unmixing [9] [30].

- Troubleshoot and Iterate: Evaluate the resolution of your populations. If resolution is poor (e.g., dim populations are not distinct from negative, or spillover is high), return to Step 2 and reassign problem fluorophores to different channels or to markers that are not co-expressed [28].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is it critical to match fluorophore brightness to antigen density? Matching brightness to abundance ensures optimal resolution of your target populations. A dim fluorophore on a low-abundance antigen will produce a weak signal that may be indistinguishable from background autofluorescence. Conversely, a very bright fluorophore on a highly expressed antigen can produce such a strong signal that it overwhelms the detector, causing excessive spillover into other channels and degrading the resolution of other markers in your panel [28].

2. On a spectral cytometer, can I use fluorophores with highly overlapping emission spectra? Yes, but with a crucial caveath. Spectral flow cytometry can distinguish fluorophores based on their entire spectral signature, not just their peak emission. However, the algorithms still require the signatures to be unique enough to be mathematically separated. If two fluorophores have near-identical spectra across all detection channels, unmixing will fail. Always check the spectral similarity score in your panel design software; fluorophore combinations with lower similarity are ideal [9] [23].

3. My tandem dye is giving inconsistent results. What could be wrong? Tandem dyes (e.g., PE-Cy7, APC-Cy7) are prone to degradation because they consist of two fluorophores coupled together. If this bond breaks, the donor fluorophore's signal will increase, radically shifting the spectral signature and causing massive spillover. To prevent this:

- Protect from light: Always store conjugated antibodies and stained samples in the dark.

- Avoid freeze-thaw cycles: Aliquot antibodies.

- Use fresh fixative: Some fixatives can accelerate tandem degradation. Test different fixatives; 0.5% formaldehyde has shown better stability for some tandems than stronger alternatives [30].

4. How long can I use my single-color reference controls for spectral unmixing? With proper preparation and storage, single-color controls can be stable for extended periods, but this requires validation. One study found that when using the same antibody lot and proper fixation (e.g., 0.5% formaldehyde), controls could effectively unmix data acquired one to two months later [30]. However, tandem dye controls are less stable and may need to be remade every few days. Always check the stability of your specific controls under your storage conditions.

5. What is the best way to handle cellular autofluorescence in my experiment? Spectral flow cytometry offers a significant advantage here. Because it records a full spectrum, cellular autofluorescence can often be identified as a distinct "signature" and subtracted during the unmixing process. Many spectral analyzers allow you to include autofluorescence as a separate "fluorophore" in your unmixing algorithm, which can dramatically improve the resolution of dimly expressed markers [9] [31].

FAQs on Tandem Dye Stability and Breakdown

What are tandem dyes and why is their stability a concern?

Tandem dyes are composed of two fluorophores—a donor and an acceptor—covalently bound together. They function through Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET), where the donor fluorophore absorbs light and transfers the energy to the acceptor, which then emits light at a longer wavelength. This process allows you to get multiple distinct readouts from a single laser, greatly increasing panel flexibility [32] [33].

The primary concern is their tendency to break down or decouple, a process where the chemical linkage between the two fluorophores degrades. When this happens, the energy transfer fails, and you primarily detect light emission from the donor fluorophore (e.g., PE or APC). This breakdown creates spillover-like artifacts and false-positive signals in your data, which can lead to biological misinterpretation [34] [33].

What specific factors cause tandem dye breakdown?

Tandem dye degradation is influenced by several factors, which can act alone or in combination [34]:

- Light: Exposure to light, especially during sample preparation, can photobleach the donor and acceptor molecules [32].

- Temperature: Higher temperatures accelerate the breakdown process. It is crucial to keep antibody stocks and staining mixes cold [34].

- Fixatives: Formaldehyde-based fixatives generally cause manageable but noticeable degradation. Harsher fixatives like methanol can severely degrade the protein portion of the tandem dye [34].

- Time: Older vials of tandem dyes and master mixes containing them will show more degradation [34].

- Cellular Enzymes: A critical factor is a cell-dependent degradation mechanism. Metabolically active cells, particularly myeloid cells like monocytes and macrophages, contain enzymes that catalytically break down tandems. This means breakdown can be highly variable between different cell types in the same sample [34] [35].

How can I design my panel to minimize the impact of tandem breakdown?

Strategic panel design is your first line of defense against tandem dye breakdown artifacts [34] [33]:

- Avoid tandems on widely expressed markers. This prevents breakdown signals from appearing across many cell populations.

- Do not assign the tandem dye and its parent fluorophore to markers expressed on the same cell type. For example, avoid using a PE-based tandem and a plain PE antibody on markers co-expressed on T cells.

- Match antigen density with fluorophore brightness. Avoid using a very bright tandem dye on a highly expressed marker if you are using the parent fluorophore for a dim marker. Breakdown signal from the bright tandem can overwhelm the authentic dim signal.

- Consider newer, more stable dyes. Dyes like BioLegend's Fire dyes (excluding Fire 810), Bio-Rad's StarBright, or BD's RealBlue dyes are engineered for higher stability and can be excellent alternatives [33].

What are the best practices for handling tandem dyes during experiments?

Proper handling from staining to acquisition is essential [34] [36] [33]:

- Work quickly and keep samples in the dark. Use foil to cover tubes and plates as much as possible.

- Keep things cold. Store antibodies and perform staining steps on ice or in a cold room when feasible.

- Prepare master mixes fresh. Do not make master mixes containing tandems too far in advance.

- Use a Tandem Stabilizer. Commercial additives like BioLegend's Tandem Stabilizer can significantly reduce breakdown. It is recommended to add it to your master mix, perm/wash buffers, and the final sample resuspension buffer prior to acquisition [34] [26].

- Match your controls to your samples. Your single-color controls for unmixing/compensation must be treated identically to your experimental samples (same light, temperature, fixation, and time conditions). If staining a cell type known to cause breakdown, use cells—not beads—as your controls [34].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| False positive signal in a channel corresponding to a parent fluorophore (e.g., PE or APC). | Breakdown of a tandem dye (e.g., PE-Cy7) into its constituent parts. | Verify panel design rules; use Tandem Stabilizer; ensure proper handling to limit light/heat exposure [34] [33]. |

| Variable false positives between different cell types in the same sample. | Cell-dependent enzymatic degradation, often worse in myeloid cells. | Use a Tandem Stabilizer; for intracellular staining, add stabilizer to perm/wash buffers; use cells (not beads) for single-color controls [34] [35]. |

| High background or spreading error across multiple channels. | Excessive tandem breakdown and/or spectral spillover from a high-expression marker. | Titrate antibodies; review panel design to avoid bright tandems on abundant targets; use FMO controls to set gates [36]. |

| Weak or lost signal in the tandem channel. | General photobleaching or severe dye degradation. | Protect samples from light; use fresh antibody aliquots; check antibody expiration dates [36]. |

| Poor resolution of a dim marker. | The marker is assigned to a parent fluorophore (e.g., PE) and a bright tandem (e.g., PE-Cy7) is breaking down into it. | Re-design the panel to assign the dim marker to a non-tandem dye and the bright marker to a more stable fluorophore [33]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents used to manage tandem dye stability.

| Reagent | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Tandem Stabilizer [34] [26] [32] | Commercial additive to reduce decoupling of tandem dyes. | Add at a 1:1000 dilution to staining master mixes, wash buffers, and sample storage buffer. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent [26] [32] | Blocks non-specific binding of antibodies to Fc receptors on cells. | Incubate cells with purified anti-CD16/32 antibodies or normal serum for 15 minutes prior to surface staining. |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer [26] | Prevents dye-dye interactions between polymer-based "Brilliant" dyes (e.g., Brilliant Violet). | Add at up to 30% (v/v) to surface antibody staining master mixes. |

| CellBlox [26] | Prevents non-specific interactions for NovaFluor dyes. | Use according to manufacturer's instructions for panels containing NovaFluor dyes. |

| Vitamin C [34] [35] | An antioxidant that can antagonize the cell-dependent degradation of tandems. | Can be tested as an alternative to commercial stabilizers (concentration requires optimization). |

Experimental Protocol: Surface Staining with Tandem Stabilization

This protocol provides an optimized workflow for surface staining that incorporates steps to minimize tandem dye breakdown, adapted from a published method [26].

Materials

- Cells (e.g., murine splenocytes or human PBMCs)

- FACS Buffer (PBS with 0.5-1% BSA or FBS, optional 0.1% sodium azide)

- Mouse Serum (e.g., Thermo Fisher, cat. no. 10410)

- Rat Serum (e.g., Thermo Fisher, cat. no. 10710C)

- Tandem Stabilizer (BioLegend, cat. no. 421802)

- Brilliant Stain Buffer (BD Biosciences, cat. no. 566385)

- Surface antibodies

- 96-well V-bottom plates

Workflow

Procedure

Prepare Blocking Solution: Create a mixture containing mouse serum, rat serum, and Tandem Stabilizer in FACS buffer. A sample formulation is [26]:

- Mouse Serum: 300 µL

- Rat Serum: 300 µL

- Tandem Stabilizer: 1 µL

- 10% Sodium Azide: 10 µL (optional, for short-term use)

- FACS Buffer: 389 µL

- Total Volume: 1 mL

Plate and Wash Cells: Dispense your cells into a V-bottom 96-well plate. Centrifuge the plate at 300 × g for 5 minutes (at 4°C or room temperature) and carefully decant the supernatant.

Block Cells: Resuspend the cell pellet in 20 µL of the prepared blocking solution. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature, protected from light.

Prepare Staining Mix: While blocking, prepare the surface antibody master mix. For each sample, combine:

- Tandem Stabilizer: 1 µL

- Brilliant Stain Buffer: 30 µL (or a volume up to 30% of the total mix)

- Titrated surface antibodies: As required

- FACS Buffer: to a final volume of 100 µL

Stain Cells: Add 100 µL of the surface staining mix to each well. Mix thoroughly by pipetting. Incubate for 1 hour at room temperature in the dark.

Wash Cells: Add 120 µL of FACS buffer to each well. Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes and discard the supernatant. Repeat this wash step with a larger volume of 200 µL FACS buffer.

Resuspend for Acquisition: Resuspend the final cell pellet in FACS buffer containing Tandem Stabilizer at a 1:1000 dilution. Your samples are now ready for acquisition on the flow cytometer [34] [26].

The effectiveness of Tandem Stabilizer is demonstrated by reduced false-positive signals. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from validation experiments [34].

| Condition | False PE Signal (a.u.) | False APC Signal (a.u.) | Data Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Stabilizer | High | High | Poor: Significant false positives and skewing. |

| Stabilizer in Final Buffer Only | Medium | Medium | Moderate: Reduced but persistent artifacts. |

| Stabilizer Throughout Protocol | Low | Low | Good: Cleanest data with minimal breakdown. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Staining Problems and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background Fluorescence | Fc receptor-mediated non-specific antibody binding on monocytes, macrophages, or B cells [26] [37] [38] | Implement Fc receptor blocking with serum or specific blocking antibodies prior to antibody incubation [26] [37] [39]. |

| Non-specific binding from dead cells or cellular debris [40] [38] | Include a viability dye to gate out dead cells during analysis; ensure high cell viability (>90%) before staining [37] [38]. | |

| Unexpected Positive Signals or "Spreading" | Polymer dye interactions (e.g., Brilliant Violet, Super Bright) when multiple dyes are used without a stabilizer [26] [21] | Use a commercial polymer dye stain buffer (e.g., Brilliant Stain Buffer) in the staining mix [26] [21]. |

| Tandem dye degradation, leading to emission in the channel of the constituent fluorophore [26] | Include tandem stabilizer in staining and resuspension buffers; protect tandem dyes from light [26]. | |

| Weak or No Signal | Low antigen abundance paired with a dim fluorophore [40] [38] | Pair low-density targets with bright fluorophores (e.g., PE) and high-density targets with dimmer ones (e.g., FITC) [38]. |

| Inadequate antibody titration or inappropriate instrument settings [40] [38] | Titrate all antibodies to determine the optimal concentration; verify cytometer laser and detector settings [38]. | |

| Compensation/Unmixing Errors in Full Stains | Single-stained controls are less bright than the fully stained sample [21] | Ensure positive signals in single-stain controls are at least as bright as in the experimental sample [21]. |

| Fluorophore in the control does not match the one in the panel (e.g., using FITC control for a GFP sample) [21] | Use the exact same fluorophore for the control and the full stain [21]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is Fc receptor blocking critical for immunophenotyping? Fc receptors naturally bind to the constant region (Fc) of antibodies, independent of the antigen-binding site. This can cause non-specific staining, obscuring true positive signals and increasing background, particularly on immune cells like monocytes, macrophages, and B cells. Blocking these receptors ensures that antibody binding is specific to its target antigen [26] [37].

Q2: When should I use a polymer dye stain buffer? You must use a polymer stain buffer (e.g., BD Brilliant Stain Buffer or Thermo Fisher SuperBright Stain Buffer) anytime your panel contains two or more antibodies conjugated to polymer dyes, such as the Brilliant Violet (BV) or Super Bright families. These dyes are prone to hydrophobic interactions, which can cause them to stick together and generate erroneous signals. The buffer contains components that prevent these interactions, preserving data integrity [26] [21].

Q3: Can I use the same blocking serum for all my experiments? No. For best results, the blocking serum should match the host species of the primary antibodies you are using. For example, if you are staining mouse cells with primarily rat-derived antibodies, you should use normal rat serum. Avoid using serum from the same species as your cells if you are staining for immunoglobulins [26].

Q4: My single-stain controls look fine, but my full-panel stains show errors. Why? This is a common issue that indicates your single-stain controls did not perfectly mimic your full stain. The most frequent reasons are:

- The fluorescence intensity in the single-stain control was lower than in the full stain [21].

- You used compensation beads for controls but cells for your experiment, and their autofluorescence differs [21].

- You forgot to add polymer dye buffer to your full stain, causing dye-dye interactions that aren't present in the single stains [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents essential for implementing optimized staining protocols in high-parameter flow cytometry.

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Normal Serum (e.g., Rat, Mouse) [26] | Blocks non-specific binding via Fc receptors. | Match the host species of your staining antibodies for most effective blocking [26]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Antibodies (e.g., anti-CD16/32) [39] | Specifically blocks common low-affinity Fcγ receptors. | An alternative to serum; often used for mouse cells [39]. |

| Brilliant Stain Buffer [26] | Prevents hydrophobic interactions between polymer dyes. | Mandatory for panels with multiple Brilliant Violet or similar dyes; use at up to 30% (v/v) of staining mix [26] [21]. |

| Tandem Stabilizer [26] | Prevents degradation of tandem dyes. | Add to staining buffer and final resuspension buffer to preserve tandem dye integrity [26]. |

| Flow Cytometry Staining Buffer [39] | Provides a protein-rich, isotonic medium for antibody staining and washing. | Typically contains BSA and sodium azide; reduces non-specific binding and maintains cell viability [39]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Basic Protocol 1: Surface Staining with Integrated Blocking

This protocol provides an optimized, general-use approach for reducing non-specific interactions when staining cell surface markers [26].

Materials

- Blocking Solution: Comprising 30% mouse serum, 30% rat serum, 0.1% tandem stabilizer, and the remainder FACS buffer [26].

- Surface Staining Master Mix: Contains antibodies, 30% Brilliant Stain Buffer (or 4x less if using Brilliant Stain Buffer Plus), 0.1% tandem stabilizer, and FACS buffer [26].

- Other: V-bottom 96-well plates, centrifuge, pipettes.

Procedure

- Prepare Cells: Dispense cells into a V-bottom 96-well plate. Centrifuge at 300 × g for 5 minutes and decant the supernatant [26].

- Block: Resuspend the cell pellet in 20 µL of blocking solution. Incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature in the dark [26].

- Stain: Without washing, add 100 µL of the surface staining master mix directly to the cells. Mix well by pipetting [26].

- Incubate: Incubate for 60 minutes at room temperature in the dark [26].

- Wash: Add 120 µL of FACS buffer, centrifuge, and discard the supernatant. Repeat the wash with 200 µL of FACS buffer [26].

- Resuspend: Resuspend the cells in FACS buffer containing a 1:1000 dilution of tandem stabilizer [26].

- Acquire: Analyze the samples on a flow cytometer [26].

Basic Protocol 2: Fc Receptor Blocking for Human Cells

This protocol is specifically optimized for blocking Fc receptors on human cells, such as peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) [37].

Materials

Procedure

- Prepare Cells: Wash cells and resuspend at 10⁷ cells/mL in cold staining buffer. Cell viability should exceed 90% [37].

- * Aliquot:* Add 50 µL of cell suspension (500,000 cells) to a tube [37].

- Block: Add 50 µL of HAB to the tube, mix, and incubate for approximately 1 minute at room temperature [37].

- Stain: Add the directly conjugated antibodies to the tube. incubate for 30 minutes at 4°C in the dark [37].

- Wash: Wash cells twice with 1 mL of buffer and resuspend for acquisition [37].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for selecting and applying the appropriate blocking and stabilization strategies in a flow cytometry experiment.

Key Technical Notes

- Serum Selection: The efficacy of Fc receptor blocking is highly dependent on using the correct serum. Always use serum from the same species as your staining antibodies for optimal results [26].

- Buffer Compatibility: Note that NovaFluor dyes may require a specific blocking reagent called CellBlox, which has a different optimization process than Brilliant Stain Buffer [26].

- Safety: Many fixatives contain paraformaldehyde and should be handled in a fume hood. Sodium azide, a common buffer additive, is highly toxic and must be handled according to its safety data sheet [26].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background Fluorescence in Backbone Panel

Problem: Excessive background noise compromises the resolution of core cell populations defined by backbone markers like CD45, CD3, CD19 [41].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| High Autofluorescence | Use fresh cells; avoid over-fixation; include unstained control; employ viability dyes [40] [42]. | Reduces non-specific signal from dead/damaged cells. |

| Fc Receptor Binding | Implement Fc receptor blocking step during staining protocol [40] [42]. | Prevents non-specific antibody binding. |

| Insufficient Washing | Increase wash buffer volume, number, or duration of washes [40] [42]. | Removes unbound antibody. |

| Spillover Spreading | Use multicolor panel builder tools to minimize emission spectrum overlap; optimize compensation [42]. | Corrects for fluorescence spillover between channels. |

Issue 2: Low Signal Intensity on Critical Backbone Markers

Problem: Weak or absent detection signal for key lineage-defining markers (e.g., CD4, CD8, CD14, CD16 [41]), hindering major population identification.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Low Antigen Expression | Pair low-abundance targets with bright fluorophores (e.g., PE, APC) [43]. | Maximizes signal-to-noise ratio. |

| Suboptimal Antibody Titer | Titrate all antibody reagents to determine optimal concentration for specific cell types [40] [42]. | Ensures optimal antibody binding. |

| Fluorophore Handling | Protect fluorophores from light; avoid prolonged exposure to fixatives, especially for tandem dyes [42] [44]. | Prevents photobleaching and dye degradation. |

| Incorrect Laser/Filter Setup | Verify instrument configuration matches fluorophore requirements [43] [42]. | Ensures proper laser excitation and signal detection. |

Issue 3: Poor Resolution of Major Immune Populations Across Sites

Problem: Inconsistent gating of major immune cell subsets (T cells, B cells, monocytes, NK cells) when the same backbone panel is used across different instruments or locations [45].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Principle |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument Variability | Use standardized workflows and validate the backbone panel on the specific instrument[scitation:1]. | Controls for technical variation. |

| Compensation Errors | Use bright, single-stained controls (cells or beads) for each fluorophore; avoid reusing compensation matrices [44]. | Accurately corrects spectral overlap. |

| Sample Processing Differences | Standardize sample handling, fixation, and staining protocols across all sites [45]. | Minimizes pre-analytical variation. |

Experimental Protocol: Backbone Panel Optimization and Drop-In Modification

This protocol outlines the steps for qualifying a modified backbone flow cytometry panel, based on a case study where a single antibody was replaced for a Phase II oncology study [45].

Workflow for Backbone Panel Modification

Context: A 19-color spectral flow cytometry backbone panel for human whole blood required the replacement of one antibody to detect a specific cell therapy [45].

Step 1: Titration of Replacement Antibody

- Prepare an appropriately stained whole blood sample.

- Titrate the new replacement antibody in the context of the core antibody set.

- Select the concentration that provides optimal staining index and separation [45].

Step 2: Method Optimization

- Conduct optimization studies using the selected antibody concentration.

- Ensure all other assay components remain identical [45].

Step 3: Method Qualification (Fit-for-Purpose)

- Perform a targeted qualification based on the degree of change and context of use.

- Key Assessments [45]:

- Limit of Blank (LOB) / Limit of Detection (LOD): Determine the lowest signal distinguishable from background.

- Lower Limit of Quantitation (LLOQ): Establish the lowest concentration that can be reliably measured.

- Stability: Evaluate sample stability under various conditions.

- Precision: Assess intra-assay, inter-operator, and inter-instrument variability.

Outcome: The case study achieved assay readiness in approximately 8 weeks, meeting sponsor deadlines and ensuring robustness for a global Phase II study [45].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What exactly is a backbone flow cytometry panel? A backbone panel is a well-characterized, optimized, or validated set of core markers used to define major cell populations of interest, such as T cells, B cells, monocytes, and NK cells [45]. It provides a consistent framework with flexible "drop-in" channels, allowing researchers to add custom markers without rebuilding the entire assay [45] [46].

Q2: How does the backbone approach improve data comparability in multi-center clinical trials? The backbone approach ensures cross-site reproducibility by using stable population definitions over time and location [45]. It employs standardized workflows, sample handling methods, and data analysis strategies, which reduce assay variability and make it easier to merge data collected from different cohorts, sites, or time points [45] [41].

Q3: When should I use a bright fluorophore versus a dim one for my backbone markers? As a general rule, use the brightest fluorophores for low-abundance antigens or rare cell populations [43]. Dimmer fluorophores are suitable for highly expressed antigens. For example, a bright fluorophore like PE or APC is recommended for detecting a sparsely expressed marker, whereas a dimmer fluorophore can be used for a ubiquitous marker like CD45 [43].

Q4: What are the critical controls for properly gating a high-parameter backbone panel?

- Fluorescence Minus One (FMO) Controls: Tubes containing all fluorophores except one. These are essential for accurately setting positive/negative gates, especially for emergent markers or rare populations [44].

- Single-Stained Controls: Necessary for calculating compensation for each fluorophore. These can be cells or compensation beads, but the carrier should be consistent for each channel [44].

- Unstained Cells: To assess autofluorescence [42].

Q5: Can I reuse a compensation matrix from a previous experiment for my backbone panel? It is not recommended. The best practice is to run compensation controls fresh for each experiment. Tandem dyes are particularly susceptible to degradation over time, which changes their spectral properties. Furthermore, instrument sensitivity can drift, making a previously calculated matrix inaccurate [44].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Backbone Panels |

|---|---|

| Viability Dye | Critical for excluding dead cells from analysis, which reduces background and improves data quality [45]. |

| Fc Receptor Blocking Reagent | Minimizes non-specific antibody binding, a common source of high background [40] [42]. |

| Compensation Beads | Provide a consistent, uniform population for setting up compensation controls and instrument calibration [44]. |

| Antibody Capture Beads | Useful for creating bright, single-positive compensation controls, especially for markers that are not well-expressed on available cells [44]. |

| Cell Stabilization Reagents | Preserve sample integrity, crucial for multi-site trials where samples may be shipped [47]. |

| Pre-validated Backbone Panels | Offer a standardized starting point for immunophenotyping, saving time and resources in panel development [45] [47]. |

Logical Framework for Addressing Spectral Overlap in Backbone Panels

Spectral Overlap Management Workflow

Advanced Troubleshooting: Identifying and Correcting Unmixing Errors

FAQ: Why is my negative population not round and showing asymmetric spread?

An asymmetrical or "swooping" negative population is a classic sign of an unmixing error. It occurs when the reference control used to create the spectral signature does not accurately match the conditions of that fluorophore in your full panel sample [48] [49].

- Root Cause: The most common reason is a mismatch between your single-color control and your multi-color sample. This can be due to differences in autofluorescence, fluorophore brightness, or the cellular environment (e.g., fixation) [48].

- The "Like-With-Like" Rule: The autofluorescence of the positive cells in your control must be identical to the autofluorescence of the negative cells. Violating this rule, for example, by using unstained live cells as a negative for a viability dye stained on dead cells (which are more autofluorescent), will introduce error [48].

Diagnostic Table: Common Unmixing Error Patterns

| Observed Pattern | Likely Cause | How to Investigate |

|---|---|---|

| Asymmetrical "swooping" or "banana-shaped" positive populations [48] | Inaccurate spectral signature from reference control; spillover from other fluorophores not properly subtracted [48] [49] | Plot all fluorophores on NxN plots to find the interfering channel [48]. |

| Non-round negatives and ultra-negative events [48] [49] | Spillover errors causing a spread in the data, leading to events with negative values after unmixing [48]. | Check for positive correlations between markers that are not biologically linked [49]. |

| Multiple positive peaks where only one is expected [48] | Breakdown of tandem dyes (e.g., APC-Cy7) or contamination of the control with another fluorophore. | Inspect the reference control histogram for multiple peaks; ensure tandem dyes are from the same lot and protected from light and fixatives [48]. |

| Massive spreading in the negative, making it hard to gate [49] | High panel complexity or a poorly designed panel with fluorophores that have very similar spectra (high similarity index). | Calculate the panel's complexity index; aim to use fluorophores with a similarity index of <0.98 [48]. |

| The staining pattern is different from previous experiments [49] | Incorrect unmixing/compensation, or a change in the reference controls over time (e.g., degraded tandem dyes in a stored reference library). | Re-validate reference library controls; ensure consistent sample processing protocols [48]. |

FAQ: My data shows "hypernegative" events. What does this mean?

The presence of distinct ultra-negative populations is a clear indicator of significant spillover error from an incorrectly unmixed fluorophore [49]. Unlike the symmetrical spread of a true negative population, these errors create a distinct, asymmetrical population that leans negative as fluorescence in the interfering channel increases [49].

Protocol: Systematic Validation of High-Sensitivity Panels

Following established guidelines like CLSI H62 ensures reliable detection of rare populations and minimizes unmixing errors [50].

Precision Evaluation:

- Intra-assay Precision: Run three replicates of the same sample in a single acquisition. Calculate the %CV for the population of interest.

- Inter-assay Precision: Run three replicates of the same sample across four different runs (e.g., different days). Express precision as the mean %CV of all runs.

- Acceptance Criteria: For rare cell populations (<0.1%), a %CV of 30–35% can be considered acceptable [50].

Sample Stability Assessment:

- Divide a sample into aliquots and treat them with a stabilizer (e.g., TransFix).

- Store samples at room temperature and analyze them at multiple time points (e.g., 0, 4, 24, 48 hours).

- Calculate the relative difference between results at each time point and the baseline (0-hour). A relative difference of <20% indicates acceptable stability [50].

Establishing the Lower Limit of Quantification (LLOQ):

- Use a sample with a known low frequency of the target population.

- The LLOQ is the lowest level at which the analyte can be reliably quantified with acceptable precision and accuracy. This is critical for validating assays designed to detect rare events [50].

Table: Example Precision Validation Data for a Rare Cell Population (Tfh cells)