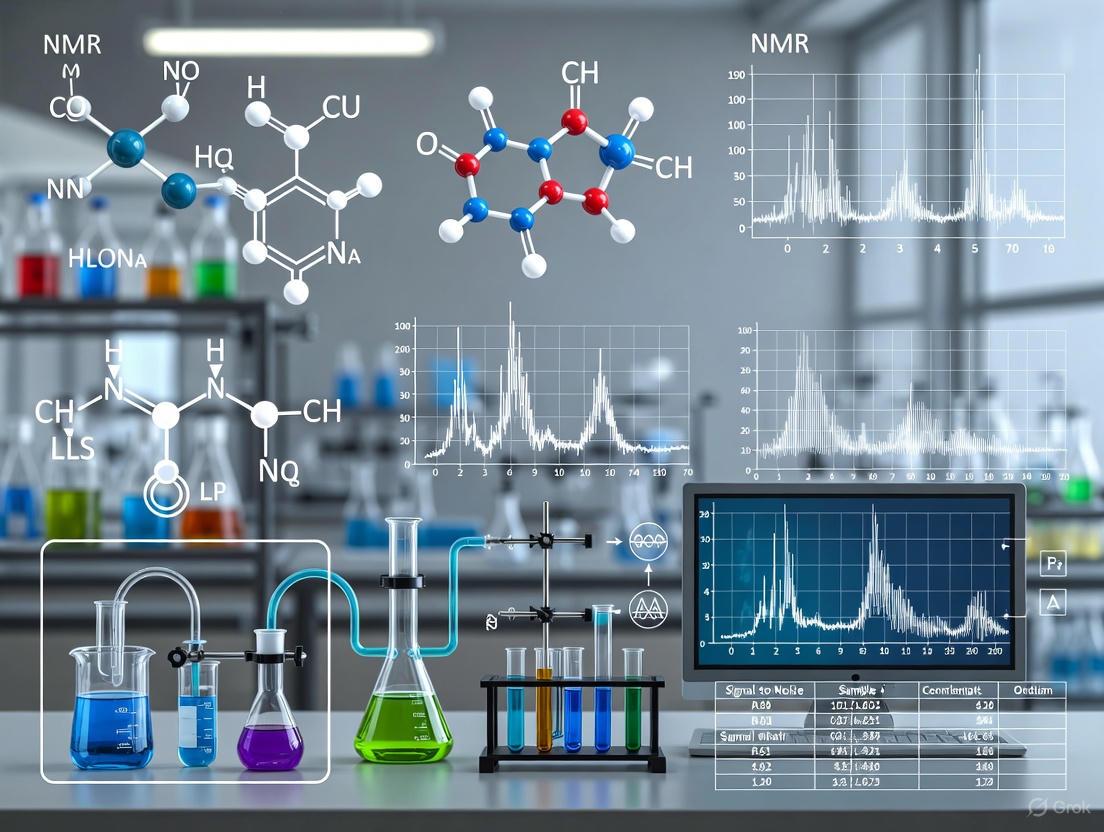

Maximizing NMR Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide to Signal-to-Noise Ratio Optimization for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Maximizing NMR Sensitivity: A Comprehensive Guide to Signal-to-Noise Ratio Optimization for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it explores the critical impact of SNR on data quality, detection limits, and the reliability of metabolic profiling and biomarker discovery. The content details practical methodologies for parameter adjustment, coil design, and experimental setup, alongside troubleshooting common issues and validating performance across spectrometer platforms. With a focus on both conventional and emerging autonomous optimization techniques, this guide serves as an essential resource for maximizing the potential of NMR in sensitive biomedical analyses.

Understanding NMR Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Core Principles and Impact on Data Quality

Defining SNR and Its Critical Role in Detection Limits and Quantification

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and why is it critical in NMR spectroscopy?

The Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a measure of the strength of a desired signal compared to the background noise in a system [1]. In NMR spectroscopy, it quantifies how well the true NMR signal can be distinguished from random, unwanted fluctuations [2]. A higher SNR indicates a stronger desired signal relative to background noise, resulting in cleaner, more reliable spectra and enabling the detection of weaker signals, which is crucial for identifying minor components or low-concentration samples [1] [3].

Q2: How is SNR quantitatively determined in an NMR spectrum?

A common method for determining SNR involves selecting a region of the spectrum where no signals are present, calculating either the root mean square or standard deviation of the data in this region as the noise level, and then dividing the height of a specific signal by this noise level [2]. The formula can be represented as SNR = Signal_Height / Noise_Level.

Q3: What is the relationship between SNR, Limit of Detection (LOD), and Limit of Quantification (LOQ)?

SNR directly determines the Limits of Detection (LOD) and Quantification (LOQ). The LOD is the minimum concentration at which a substance can be reliably detected, typically requiring an SNR between 3:1 and 10:1. The LOQ is the minimum concentration for reliable quantification, generally requiring an SNR of 10:1 or higher [4]. According to ICH guidelines, a signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1 is acceptable for estimating the detection limit, while a 10:1 ratio is required for quantification [4].

Q4: Why might automatic receiver gain (RG) adjustment not provide optimal SNR?

Recent research indicates that SNR does not always increase monotonically with receiver gain. On some spectrometers, a drastic drop in SNR is observed for certain nuclei at specific gain settings [5]. For example, while RG=18 provided a 13C SNR similar to the maximum at 9.4 T, at RG=20.2, the determined SNR was 32% lower [5]. Automatic RG adjustment is programmed to maximize signal and avoid overflow but does not necessarily account for these complex SNR characteristics [5].

Q5: What are some advanced computational methods for improving SNR?

Deep learning protocols have been developed for high-quality, reliable, and fast noise reduction of NMR spectroscopy [3]. These methods effectively reduce noises and spurious signals, recover desired weak peaks almost entirely drowned in severe noise, and implement considerable SNR improvement [3]. Additionally, sequential Bayesian optimal experimental design can optimize experimental conditions to maximize information gain per unit time, particularly beneficial for experiments with limited prior knowledge, such as those studying minor conformational states of proteins [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Improving Poor SNR in 1D 13C NMR Experiments

Problem: Weak or noisy 13C NMR signals that are insufficient for reliable detection or quantification.

Solution:

- Increase Sample Concentration: The signal intensity is directly proportional to spin concentration [5]. Use the highest concentration feasible while considering solubility and cost.

- Optimize Receiver Gain (RG): Do not rely solely on automatic RG adjustment. Perform a manual RG calibration to find the optimal setting for your specific nucleus and spectrometer [5].

- Utilize Signal Averaging: Acquire and accumulate multiple scans. The SNR improves with the square root of the number of scans [1].

- Ensure Proper Parameter Setup: For nuclei with large chemical shift ranges, set correct O1P (transmitter offset) and SW (spectral width) to maintain good excitation profile and sensitivity [7].

Verification: After implementation, compare the SNR of a characteristic signal before and after optimization using the standard calculation method [2].

Guide 2: Addressing Inconsistent LOD/LOQ Determinations in Regulatory Submissions

Problem: Inconsistent determination of detection and quantification limits for impurity profiling in pharmaceutical applications.

Solution:

- Establish Robust Baseline Measurement: Use a peak-free section in the current chromatogram or from a previous blank run to determine baseline noise [4].

- Apply Appropriate SNR Criteria: For LOD, ensure SNR ≥ 3:1; for LOQ, ensure SNR ≥ 10:1 in accordance with ICH Q2(R1) guidelines [4].

- Validate with Realistic Samples: Under challenging chromatographic conditions, consider using stricter SNR values (3:1-10:1 for LOD, 10:1-20:1 for LOQ) to ensure robustness [4].

- Document Processing Parameters: Note that excessive data smoothing can artificially improve SNR but may suppress small peaks; preserve raw data for verification [4].

Verification: Prepare standard solutions at LOD and LOQ concentrations and verify that they meet the required SNR criteria with acceptable precision and accuracy.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Optimal Receiver Gain for Maximum SNR

Purpose: To empirically determine the receiver gain setting that provides maximum SNR for a specific nucleus and spectrometer, as automated settings may not optimize for SNR [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Standard reference sample (e.g., 1 mM 13C-labeled compound)

- NMR spectrometer with variable receiver gain control

- Standard NMR tube

Procedure:

- Prepare a standard sample of known concentration.

- Set up a standard 1D experiment for the nucleus of interest.

- Run a series of identical experiments while systematically varying the receiver gain.

- For each experiment, process the data identically and calculate the SNR for a specific signal.

- Plot SNR versus receiver gain to identify the optimal setting.

Expected Outcome: A non-monotonic relationship between RG and SNR may be observed, with a specific RG value providing maximum SNR [5].

Protocol 2: SNR Calibration for Hyperpolarized Samples

Purpose: To establish optimal RG and excitation angle parameters for hyperpolarization experiments where automatic RG adjustment is not possible [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- Hyperpolarized sample (e.g., [1-13C]pyruvate)

- NMR spectrometer capable of hyperpolarization experiments

Procedure:

- Estimate the expected signal intensity based on polarization level and concentration [5].

- Set RG sufficiently low to avoid ADC overflow but high enough to maintain sensitivity.

- Use the relationship: Signal = A · f(RG) · sin(α) · P · C, where α is the flip angle, P is polarization, and C is concentration [5].

- Perform test experiments to verify settings before the actual hyperpolarized experiment.

Expected Outcome: Optimal parameters that provide high SNR while avoiding ADC-overflow artefacts for transiently enhanced signals [5].

Data Presentation

Table 1: SNR Requirements for Analytical Method Validation Based on ICH Guidelines

| Parameter | Definition | Minimum SNR Requirement | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | Minimum concentration at which a substance can be reliably detected | 3:1 | Identifying the presence of impurities or low-abundance species |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | Minimum concentration at which a substance can be reliably quantified | 10:1 | Precise measurement of impurity levels or minor components |

| Target SNR for Robust Quantification | Recommended SNR for reliable quantitative analysis | 10:1 - 20:1 | Pharmaceutical analysis under challenging conditions [4] |

Table 2: Factors Affecting SNR in NMR Spectroscopy and Optimization Strategies

| Factor | Effect on SNR | Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Concentration | Directly proportional to signal intensity [5] | Use maximum feasible concentration; consider sample solubility |

| Magnetic Field Strength | Higher fields generally improve sensitivity | Use highest available field strength for challenging experiments |

| Number of Scans (NS) | Improves as √NS [1] | Increase acquisition time; balance with experimental throughput |

| Receiver Gain (RG) | Non-monotonic relationship; optimal value is system-dependent [5] | Perform manual RG calibration rather than relying solely on automation |

| Probe Tuning/Matching | Poor tuning reduces sensitivity and increases noise [7] | Ensure proper tuning/matching for each sample; use automated tuning when available |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for NMR SNR Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function/Application | Usage Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents | Lock signal and field frequency stabilization | Use high-quality, anhydrous solvents for best results |

| Standard Reference Compounds | System performance validation and SNR calibration | Use certified reference materials for quantitative work |

| 5 mm NMR Tubes | Sample containment with consistent magnetic susceptibility | Use high-quality, matched tubes for reproducible results |

| Cryoprobes | Signal enhancement through noise reduction | Utilize for low-concentration samples or sensitivity-limited experiments |

| Shape Tools | Simulation of excitation profiles for parameter optimization [7] | Essential for non-standard nuclei or specialized experiments |

Visualization of Key Concepts

Diagram 1: SNR Optimization Workflow

Diagram 2: SNR in Analytical Decision Making

The Fundamental Relationship Between SNR, Sensitivity, and Measurement Time

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in NMR? While often used interchangeably, sensitivity and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) are distinct concepts. Sensitivity is formally defined as the ability of an instrument to detect a target analyte and is often reported as the SNR for a defined concentration of a reference substance [8]. In practice, for non-uniformly sampled spectra, a more functional definition of sensitivity is the probability of detecting weak peaks [9]. The SNR is a direct measurement of the peak height divided by the root-mean-square (RMS) value of the noise [9]. Sensitivity defines the quality and amount of data you can obtain from challenging samples, while SNR is a quantitative value you can measure from a single spectrum.

Why does signal averaging improve my SNR, and what are the practical limits? Signal averaging improves SNR because the signal intensities add proportionally to the number of scans (N), while random noise increases proportionally to the square root of N [8]. Therefore, the SNR improves with the square root of the number of scans: SNRN = SNR1 × √N. This means that to double your SNR, you need to acquire four times as many scans. The practical limit is the total available instrument time, especially for samples with long longitudinal relaxation times (T1) that require long relaxation delays to avoid signal saturation [10].

How does receiver gain (RG) affect my SNR, and should I always use the maximum value? The receiver gain (RG) amplifies the detected signal to match the dynamic range of the analog-to-digital converter. Contrary to intuition, a higher RG does not always yield a better SNR. On some modern spectrometers, the SNR for X-nuclei (like 13C or 15N) can actually drop significantly at high RG values [5]. One study found that while the signal intensity increases linearly with RG, the noise level is a non-trivial function of RG, leading to a non-monotonic relationship between RG and SNR [5]. Automatic RG adjustment may not find the optimal SNR; it is primarily designed to avoid signal overflow. For the best results, it is recommended to empirically test the SNR behavior on your specific spectrometer and nucleus of interest [5].

Can I gain sensitivity without increasing my measurement time? Yes, several advanced methods can enhance sensitivity without extending experiment time:

- Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS): By sampling only a fraction of the data points in indirect dimensions and using the saved time to acquire more scans per increment, NUS can yield a significant increase in SNR and detection sensitivity for multi-dimensional experiments within the same total measurement time [9].

- Pulse Sequence Optimization: Using sequences like SOFAST-HMQC allows for much shorter recycle delays by selectively exciting protons that relax faster, maximizing the SNR per unit time [11].

- Polarization Transfer: Techniques like INEPT transfer polarization from highly sensitive nuclei (e.g., 1H) to less sensitive nuclei (e.g., 13C or 15N), resulting in a strong signal enhancement [11].

- The Nuclear Overhauser Effect (NOE): Irradiating protons during the relaxation delay can enhance the signal of coupled heteronuclei (like 13C) by up to 200% [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Weak or No Signal in 1D 13C Spectrum

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient scans (NS) | Check if very few scans were acquired. Weak 13C signals require extensive signal averaging. | Drastically increase NS. The SNR will improve with √NS [10]. |

| Suboptimal relaxation delay (D1) | Measure T1 relaxation times or refer to literature values for similar compounds. | Optimize D1 and the excitation pulse angle using the Ernst angle condition to maximize SNR per unit time [11] [10]. |

| Missing NOE enhancement | Compare signal intensity between pulse sequences with and without 1H irradiation during D1 (e.g., zg30 vs. zgdc30). |

Use a pulse program that includes 1H irradiation during the relaxation delay (e.g., zgdc30) to leverage 1H-13C NOE [10]. |

| Incorrect receiver gain (RG) | Perform an RG calibration experiment to measure SNR as a function of RG [5]. | Set the RG to the value that empirically provides the highest SNR, which may not be the maximum value [5]. |

Problem: Poor SNR in Multi-Dimensional NMR Experiments

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient measurement time | The total measurement time may be too short for the desired resolution and sensitivity. | Consider using Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS). By sampling a subset of indirect dimension points, you can achieve higher resolution or better SNR within the same time [9]. |

| Slow molecular tumbling | For large molecules, broad lines reduce peak height and SNR. | Implement TROSY (Transverse Relaxation Optimized SpectroscopY)-type experiments, which can select the longest-lived coherences and provide dramatic sensitivity gains (e.g., 20-50 fold) [11]. |

| Conformational exchange broadening | Check if line broadening is present even when the molecule is not very large. | Use CPMG-based pulse trains during chemical shift evolution to suppress exchange contributions to linewidth [11]. |

Quantitative Data and Relationships

Table 1: SNR and Measurement Time Relationships

| Parameter Relationship | Mathematical Formula | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Averaging | ( SNRN = SNR_1 \times \sqrt{N} ) [8] | To double the SNR, the measurement time must be quadrupled. |

| Non-Uniform Sampling (NUS) Gain | SNR and sensitivity increase with well-chosen NUS schedules [9]. | For a fixed total time, skipping points in indirect dimensions allows for more scans, boosting SNR. |

| Serial Measurements (Radon Transform) | ( SNR{RT} \approx SNR{1} \times \sqrt{M} ) (for M spectra) [12] | Processing a series of M spectra with the Radon Transform can boost SNR by √M compared to a single spectrum. |

Table 2: Key Parameters for Optimizing a 1D 13C Experiment [10]

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse Program | zgdc30 |

Provides 30° excitation, 1H decoupling during acquisition, and NOE enhancement during the delay. |

| Acquisition Time (AQ) | 1.0 second | Balances sufficient digitization with the Ernst angle condition; shorter times cause truncation artifacts. |

| Relaxation Delay (D1) | 2.0 seconds | Combined with AQ=1.0s, gives D1+AQ=3.0s, which is optimal for the Ernst angle for a typical 13C T1 of ~20s. |

| Number of Scans (NS) | 128 (or more as needed) | Essential for building SNR for insensitive 13C nuclei. |

| Window Function | Gaussian (GM), LB=-0.2, GM=0.07 | Provides narrower lines and slightly better SNR than standard exponential line broadening. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Method for Measuring 1H Sensitivity (SNR) This protocol is used to assess the intrinsic sensitivity of an NMR instrument [8].

- Sample: Prepare a sample of 1% (v/v) ethylbenzene in CDCl3.

- Acquisition Parameters:

- Experiment: 1D proton (pulse-acquire)

- Pulse flip angle: 90°

- Acquisition time: > 1 s

- Relaxation delay: > 60 s (to ensure full relaxation)

- Number of scans (NS): 1

- Processing:

- Process the data with 1.0 Hz of exponential line broadening (apodization).

- Do not use any resolution enhancement functions.

- SNR Calculation:

- Measure the height of the tallest peak in the methylene quartet (at ~2.65 ppm).

- Measure the root-mean-square (RMS) noise in a signal-free region of the spectrum (e.g., between the methylene and aromatic signals).

- Calculate SNR = (Peak Height) / (RMS Noise). A higher value indicates a more sensitive instrument.

Protocol 2: Optimizing Receiver Gain (RG) for Maximum SNR This procedure should be performed for different nuclei and spectrometers to account for system-specific non-linearities [5].

- Sample: Use a standard sample for the nucleus of interest (e.g., 1% ethylbenzene for 1H, a labeled compound for 13C).

- Acquisition:

- Set up a standard 1D experiment for the nucleus.

- Keep all parameters constant (NS, D1, AQ, pulse power) except for the RG.

- Acquire a series of spectra, incrementing the RG from its minimum to its maximum value.

- Analysis:

- For each spectrum, measure the SNR of a well-resolved peak.

- Plot the measured SNR as a function of the set RG value.

- Optimization:

- Identify the RG value that yields the highest SNR. Use this value for future experiments on that spectrometer for the same nucleus.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SNR and Sensitivity Experiments

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity Reference Sample | Used to standardize and measure the SNR performance of an NMR instrument. | 1% Ethylbenzene in CDCl3 [8]. The methylene quartet at ~2.65 ppm is used for the measurement, not the aromatic signals. |

| Shigemi Tubes | Matches the magnetic susceptibility of the solvent to confine the sample to the most homogeneous region of the magnetic field, improving lineshape and effective sensitivity [11]. | Especially useful for precious, low-volume samples. |

| Deuterated Solvents | Provides a lock signal for the spectrometer to maintain magnetic field stability and can be the source for the reference signal. | Standard solvents like D2O, CDCl3, DMSO-d6. |

| Cryo-Probes | Cools the receiver coil and pre-amplifier to reduce electronic noise, typically providing a 4-fold increase in sensitivity compared to conventional probes [11]. | Now standard on most modern research spectrometers. |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds | Enables the study of biomolecules (proteins, nucleic acids) by incorporating sensitive NMR nuclei (e.g., 13C, 15N) at high abundance [11]. | Essential for multi-dimensional NMR studies of biological macromolecules. |

How Magnetic Field Strength (B₀) and Probe Design Influence Theoretical SNR Limits

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Troubleshooting Common SNR Issues

FAQ: My NMR signal is weak and noisy. What are the primary factors I should check to improve SNR? The most common factors affecting SNR are magnetic field strength (B₀), probe design and configuration, sample properties, and data acquisition parameters. Begin by verifying your receiver gain (RG) settings, as improper RG can reduce SNR by up to 32% even on modern spectrometers [5]. Ensure your sample is properly prepared—inhomogeneous samples, air bubbles, or poor quality NMR tubes can severely degrade magnetic field homogeneity and SNR [13]. Check that your system is properly shimmed, as field inhomogeneity broadens resonance lines and reduces signal amplitude [8].

FAQ: I am considering upgrading to a higher field instrument. What practical SNR gain can I expect moving from 3T to 11.7T based on experimental data? Experimental measurements under controlled conditions show SNR gains following approximately B₀^1.94±0.16 between 3T and 11.7T [14]. This closely matches the theoretical prediction of B₀^2. The table below summarizes experimental SNR measurements across field strengths:

Table: Experimental SNR Gains vs. Theoretical Predictions

| Field Strength | Theoretical SNR Trend | Experimental SNR Relationship | Practical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Field (<0.2T) | SNR increases linearly with B₀ | Linear increase with B₀ | Best-case scenario with small samples [15] |

| Intermediate Field (0.2T-3T) | SNR increase flattens | Rate of increase flattens | Diminishing gains with increased field strength [15] |

| High Field (3T-11.7T) | Proportional to B₀² | B₀^1.94±0.16 [14] | Closely matches theoretical prediction under controlled conditions |

| Ultra-High Field (>3T) | Theoretical expectation of 100% increase from 1.5T to 3.0T | Actual gain of 30-60% in brain tissue [15] | Biological factors, RF inhomogeneity, and relaxation changes reduce gains |

FAQ: I'm getting an "ADC overflow error" during data acquisition. How do I resolve this? ADC overflow occurs when the receiver gain (RG) is set too high, causing the signal to exceed the analog-to-digital converter's range. Immediately type "ii restart" to reset the hardware after the error occurs [13]. Set RG to a value in the low hundreds, even if the automatic "rga" adjustment suggests a higher value [13]. Always wait for the first scan to complete before leaving the experiment to ensure no ADC overflow issues occur. For hyperpolarized samples where automatic RG adjustment isn't possible, carefully calibrate RG settings in advance to avoid overflow while maintaining sufficient SNR [5].

FAQ: How does probe design specifically influence my experimental SNR? Probe design critically impacts SNR through several mechanisms. The RF coil configuration significantly affects sensitivity—crossed coil designs with separate inner solenoid coils for ¹H and outer saddle coils for X-nuclei can improve ¹H sensitivity by 30% at 600 MHz and 66% at 750 MHz compared to standard single solenoid designs [16]. Cryogenically cooled probes provide 3-4 fold sensitivity improvements by reducing electronic noise [16]. The filling factor (how well the sample fills the detection coil) also dramatically affects SNR, with smaller volume probes and proper coil design providing better sensitivity for limited samples [17] [16].

Advanced SNR Optimization

FAQ: How can I optimize receiver gain settings for maximum SNR? Systematically test your spectrometer's SNR behavior as a function of RG, as optimal settings are strongly system and resonance frequency dependent [5]. For X-nuclei, maximum SNR often occurs at modest RG settings (10-18) rather than at maximum RG [5]. Use the following relationship to guide your optimization: Signal = A · f(RG) · sinα · P · C, where f(RG) is the receiver gain function, α is the flip angle, P is the nuclear spin polarization, and C is the spin concentration [5]. For quantitative NMR, keep signal amplitudes below 50% of the receiver range threshold (RRT) to avoid signal compression and distortion [5].

FAQ: What is the relationship between data averaging and SNR improvement? SNR increases with the square root of the number of signal averages (n): SNRₙ = SNR₁ × √n [15] [8]. For example, 4 data averages double the SNR, while 16 averages provide a four-fold improvement [15] [8]. This relationship has major implications for experimental planning—an instrument with ¼ the sensitivity requires 16 times longer measurement time to achieve equivalent SNR [8]. The following table illustrates this relationship:

Table: Data Averaging and SNR Improvement

| Number of Averages (n) | SNR Improvement | Practical Application |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Baseline | Reference for single scan |

| 4 | 2× improvement | Common starting point for good SNR [15] |

| 16 | 4× improvement | Typical for demanding experiments |

| 32 | 5.66× improvement | Useful for weak signals |

| 128 | 11.31× improvement | Extreme averaging for very weak signals [15] |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Method for Measuring ¹H Sensitivity

Purpose: To quantitatively evaluate NMR instrument sensitivity using a standardized sample and acquisition parameters [8].

Materials:

- Sample: 1% (v/v) ethylbenzene in CDCl₃ with 0.1% TMS [8]

- NMR tubes appropriate for your spectrometer frequency (use high-frequency tubes ≥500MHz for high-field systems) [13]

Acquisition Parameters:

- Experiment type: 1D proton (pulse-acquire)

- Pulse flip angle: 90 degrees

- Acquisition time: >1 second

- Relaxation delay: >60 seconds

- Number of scans: 1 (for baseline measurement)

- Line broadening: 1.0 Hz exponential (no resolution enhancement) [8]

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Process data with 1 Hz exponential line broadening

- Measure the SNR of the tallest peak of the methylene quartet at ~2.65 ppm

- Use a noise region between the methylene and aromatic signals (~7 ppm) for RMS noise calculation

- Avoid using aromatic peaks for SNR measurement as they provide falsely elevated values (~5× higher) [8]

Protocol for Measuring SNR as a Function of Magnetic Field Strength

Purpose: To isolate and quantify the effect of magnetic field strength on SNR using identical experimental setups [14].

Materials:

- Spherical phantom (16.5 cm inner diameter) filled with saline water (4.6 g/L NaCl and 10 g/L agar) [14]

- Identical birdcage volume coils at all field strengths (except where exact match unavailable) [14]

- Standardized phantom holder for consistent positioning [14]

Acquisition Parameters:

- Sequence: 3D gradient-recalled echo (GRE)

- Parameters: TR = 30 ms, TE = 3 ms, resolution = 1.5 × 1.5 × 1.5 mm³, FOV = 192 × 192 × 192 mm³, matrix = 128 × 128 × 128, bandwidth per pixel = 400 Hz [14]

- Multiple flip angles and TEs to determine T₁ and T₂* values

- B₁⁺ field per volt measurement using actual flip angle imaging (AFI) sequence [14]

Analysis Method:

- Correct for flip-angle excitation inhomogeneity

- Fit signal equation to recover T₁ and T₂* values

- Calculate SNR at each field strength using identical ROI at phantom center

- Plot SNR versus B₀ and fit to power law relationship [14]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NMR SNR Optimization

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1% Ethylbenzene in CDCl₃ | Standard reference sample for ¹H sensitivity measurement [8] | Use methylene quartet at ~2.65 ppm for SNR measurement; avoid aromatic peaks [8] |

| Spherical Saline Phantom | Controlled sample for field strength SNR comparisons [14] | 16.5 cm diameter with 4.6 g/L NaCl + 10 g/L agar; provides consistent electrical properties [14] |

| Tetrakis(trimethylsilyl)silane (TKS) | Sensitivity reference for solid-state NMR [16] | Use ~2.6% TKS in KBr:NaCl (1:20:20 ratio) packed in 1.6 mm rotor [16] |

| Cryogenically Cooled Probes | Reduce electronic noise for 3-4× sensitivity improvement [16] | Particularly beneficial for sensitivity-limited experiments with dilute samples |

| Crossed Coil Probes | Independent optimization of ¹H and X-nuclei channels [16] | Provides 30-66% ¹H sensitivity improvement over single solenoid designs [16] |

| Automatic Tuning/Matching (ATM) | Ensure optimal probe coupling to sample [17] | Critical for maintaining consistent sensitivity across sample changes |

Workflow Diagrams

The Direct Link Between SNR and Coefficient of Variation (CV) in Metabolomic Data

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental relationship between SNR and CV in metabolomic data? There is a well-established inverse relationship between SNR and CV. Peaks with low SNR exhibit high CV (poor reproducibility), while peaks with high SNR exhibit low CV (good reproducibility). This relationship roughly obeys a log~10~ dependence [18].

Why should I care about CV when I have a good SNR? A low CV is a prerequisite for successful biomarker validation. The analytical reproducibility (CV) of your measurement must be smaller than the biological effect you are trying to measure for a potential biomarker to be reliably validated [19] [18].

I work with low-concentration metabolites. How does this affect my data quality? Low-concentration metabolites inherently have a lower SNR, which directly leads to a higher CV (typically in the range of 15-30% for SNR < 15). This means these metabolites are harder to quantify reproducibly and require more rigorous validation [18].

Which normalization method is best for improving CV? The optimal normalization method depends on your data [19] [18]:

- Quotient Normalization (QN) is often superior for validating low-concentration metabolites (low SNR), as it produces smaller CVs for smaller peaks.

- Normalization to Total Intensity (NTI) or Normalization to an Internal Standard (NIS) can be better for samples with very little variation in total signal intensity, especially for strong peaks.

How can I improve the SNR and CV in my NMR-based metabolomics workflow? From sample preparation to analysis, you can [20]:

- Maximize Extraction Efficiency: Use an optimized protocol, such as aqueous methanol extraction with a tissue-to-solvent ratio of 1:10 to 1:15 (mg/μL), and combine tissue homogenization with ultrasonication.

- Optimize NMR Parameters: Ensure proper sample concentration (e.g., 5-8 mg/mL for NMR analysis) and use completely relaxed spectra for quantitatively accurate results.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High CV across many metabolites, including those with strong signals.

- Potential Cause: Inadequate normalization or strong technical variation (e.g., spectrometer drift, sample degradation) [19] [21].

- Solutions:

- Apply Normalization: Test different normalization methods (QN, NTI, NIS) to see which one minimizes CV for your specific dataset [19] [18].

- Account for Technical Factors: For large-scale studies, identify and correct for sources of variation like the time between sample preparation and measurement, spectrometer batch effects, and drift over time within a spectrometer [21].

Problem: High CV specifically for low-abundance metabolites (low SNR peaks).

- Potential Cause: This is an expected analytical challenge. The low intensity of these signals makes them more susceptible to noise, leading to higher variability [18].

- Solutions:

- Increase Scans/Transients: Acquire more scans during NMR data collection to improve the SNR.

- Use Quotient Normalization: This method has been shown to specifically improve CV values for smaller peaks [18].

- Utilize Advanced Tools: Explore neural network-based quantification methods, which show promise in accurately quantifying metabolites even at low concentrations or in complex, overlapping spectra [22].

Problem: Inconsistent metabolite quantification in LC-MS data.

- Potential Cause: High technical variation and missing values, which are common challenges in global metabolite profiling by LC-MS [23].

- Solutions:

- Implement Quality Control (QC): Run a pooled QC sample repeatedly and use it to monitor performance.

- Apply Data Quality Metrics: Use metrics like the coefficient of variation (CV) and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) to assess reproducibility. Typically, compounds with a CV > 20-30% should be filtered out [23].

- Preprocess Data: Ensure proper peak alignment, denoising, and baseline correction during data preprocessing to minimize instrumental artifacts [24].

Table 1. The Relationship Between SNR, CV, and Metabolite Concentration in NMR Spectroscopy [18]

| SNR Group | Typical CV Range | Implication for Reproducibility | Metabolite Concentration Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (SNR < 15) | 15% - 30% | Poor | Low-concentration metabolites; require rigorous validation |

| High (SNR > 150) | 5% - 10% | Good | High-concentration metabolites; more robust for biomarker discovery |

Table 2. Impact of Normalization Method on CV for Different SNR Peaks [19] [18]

| Normalization Method | Effect on Low-SNR Peaks (CV) | Effect on High-SNR Peaks (CV) | Recommended Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quotient Normalization (QN) | Reduces | Increases | Optimal for studies focusing on low-concentration metabolites |

| Normalization to Total Intensity (NTI) | -- | Reduces | Superior for samples with minimal total signal intensity variation |

| Normalization to Internal Standard (NIS) | -- | Reduces | Best when a stable, reliable internal standard is available |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing the SNR-CV Relationship in Synthetic Urine Samples via NMR This protocol is adapted from foundational studies that used synthetic samples to isolate instrumental reproducibility from biological variation [19] [18].

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare five different synthetic urine samples by spiking Surine or a similar synthetic urine base with 9-17 small molecule metabolites.

- Choose components to cover a range of resonant frequencies, relaxation times, and concentrations (e.g., 63 µM to 1.1 mM).

- Add a phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.3 mM KH₂PO₄, pH 7.2) and a known internal standard (e.g., TSP in D₂O).

Data Acquisition:

- Acquire NMR spectra (e.g., ¹H NMR) for each sample repeatedly over an extended period (e.g., 8 months) to assess long-term reproducibility.

- Use a standard NMR pulse sequence and consistent instrumental parameters across all measurements.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate SNR: For each metabolite resonance, measure the signal height and divide by the standard deviation of the noise in a signal-free region of the spectrum.

- Calculate CV: For each resonance, determine the concentration or peak intensity across multiple measurements. The CV is the standard deviation divided by the mean, expressed as a percentage.

- Group Data: Group peaks into distinct SNR ranges (e.g., <15, 15-150, >150) and calculate the average CV for each group to observe the inverse relationship.

Protocol 2: Optimized NMR-Based Metabolite Extraction from Plant Seeds This protocol focuses on maximizing SNR from the initial sample preparation step [20].

- Homogenization: Use a tissuelyser to homogenize the plant seed material.

- Solvent Extraction:

- Use aqueous methanol as the extraction solvent.

- Use an optimal tissue-to-solvent ratio of 1:10 to 1:15 (mg/µL).

- Subject the homogenate to ultrasonication to improve extraction efficiency.

- Repeat Extraction: Perform the extraction process three times on the same sample pellet and combine the supernatants to maximize metabolite recovery.

- Sample Preparation for NMR:

- Dry the combined supernatants and reconstitute them in a buffer for NMR analysis.

- The optimal extract-to-buffer ratio for NMR analysis is around 5-8 mg/mL to balance signal strength and avoid issues like high viscosity.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3. Essential Materials for NMR-Based Metabolomics Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Urine (e.g., Surine) | Provides a consistent, biologically relevant matrix for preparing controlled samples for method validation. | Used as a base for spiking metabolites to study instrumental CV [18]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (D₂O) | Provides a field-frequency lock for the NMR spectrometer. | Added to samples to maintain a stable magnetic field during data acquisition [18]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., TSP-d₄) | Serves as a chemical shift reference (0.0 ppm) and can be used for concentration quantification and normalization (NIS). | Added to all samples at a known concentration (e.g., 0.3 mM) [22] [18]. |

| Phosphate Buffer | Maintains a constant pH across all samples, minimizing chemical shift variation of metabolite resonances. | KH₂PO₄ buffer at pH 7.2 is used in synthetic urine preparation [18]. |

| Aqueous Methanol | An efficient solvent for extracting a wide range of polar metabolites from biological tissues. | Used as the extraction solvent in the optimized plant seed metabolomics protocol [20]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

SNR-CV Workflow

Optimization Strategy

Exploring the Consequences of Poor SNR on Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a fundamental metric in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, quantifying the strength of a target signal relative to the level of background noise. In the context of biomarker discovery, a high SNR is prerequisite for obtaining reliable, reproducible data. NMR-based metabonomics research is critically dependent on high-quality spectral data to identify and validate potential biomarkers for human diseases. The analytical reproducibility of NMR measurements, often expressed as the Coefficient of Variation (CV) or relative standard deviation, is intrinsically linked to SNR, forming a cornerstone for successful biomarker validation [18] [19].

FAQs: SNR in Biomarker Research

FAQ 1: What is the concrete impact of poor SNR on biomarker validation?

Poor SNR directly undermines the analytical reproducibility of NMR measurements, which is the foundation of biomarker validation. Research has demonstrated an inverse correlation between SNR and the Coefficient of Variation (CV). Specifically:

- Metabolite resonance peaks with low SNR (<15) exhibit significantly higher CVs, typically in the range of 15–30% [18].

- In contrast, strong peaks with high SNR (>150) demonstrate much better reproducibility, with CVs typically between 5–10% [18]. This relationship means that potential biomarkers present at low concentrations, which yield smaller peaks, will have poorer reproducibility and therefore require much more rigorous validation efforts [18] [19].

FAQ 2: How does normalization method choice interact with SNR?

The choice of normalization method can differentially affect peaks depending on their SNR. Studies on synthetic urine samples show that:

- Quotient Normalization (QN) tends to produce smaller CVs for smaller peaks (low SNR) but larger CVs for the strongest peaks (high SNR) [18].

- Normalization to Total Intensity (NTI) or Normalization to an Internal Standard (NIS) often performs better for samples with minimal variation in total signal intensity and for strong peaks [18]. Consequently, QN may be optimal for validating low-concentration metabolites, whereas NTI or NIS could be superior for spectra where the most intense peaks are of primary interest [18].

FAQ 3: What are the primary sources of technical variation that degrade SNR and data quality?

Large-scale NMR metabolomic studies, such as the one involving ~120,000 UK Biobank participants, identify several key sources of unwanted technical variation that can impair effective SNR and compromise data [21]:

- Spectrometer Batch Effects: Differences between instruments can introduce systematic bias.

- Drift Over Time: Signal drift can occur within a single spectrometer over the course of measurement.

- Sample Preparation and Degradation: The time between sample preparation and measurement can affect metabolite stability.

- Plate Position Effects: The well position (row and column) on a shipping or measurement plate can influence measured concentrations.

- Outlier Plates: Specific plates can show anomalous behavior due to issues in the sample plating process. Proactive quality control and removal of this technical variation are essential to increase the signal for genetic and epidemiological studies [21].

Quantitative Impact of SNR on Data Quality

Table 1: Relationship Between Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and Coefficient of Variation (CV) in NMR Metabolomics

| SNR Range | Typical Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Impact on Biomarker Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Low (SNR < 15) | 15% - 30% | Poor reproducibility; requires extremely rigorous validation; high risk of false discoveries. |

| Medium | 10% - 15% | Moderate reproducibility; validation is challenging. |

| High (SNR > 150) | 5% - 10% | Good to excellent reproducibility; more reliable for validation. |

Table 2: Effect of Normalization Methods on Peaks of Different SNR

| Normalization Method | Effect on Low-SNR Peaks | Effect on High-SNR Peaks |

|---|---|---|

| Quotient Normalization (QN) | Tends to produce smaller CVs [18] | Tends to produce larger CVs [18] |

| Normalization to Total Intensity (NTI) | --- | Tends to produce smaller CVs [18] |

| Normalization to Internal Standard (NIS) | --- | Tends to produce smaller CVs [18] |

| No Normalization (NN) | --- | --- |

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving SNR and Data Quality

Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio

- Problem: Overall spectrum has poor SNR, making peaks difficult to distinguish from noise.

- Check the Sample: The most common source of poor SNR is the sample itself. Verify sample concentration, ensure it is free of precipitate or cloudiness, check for paramagnetic impurities, and confirm the NMR tube is filled to the correct height [25].

- Verify Hardware Function: If the sample appears correct, investigate potential instrument problems. This includes checking the probe tuning, the calibration of pulses (P1), and the performance of the preamplifier [25] [10].

- Optimize Acquisition Parameters: For 13C NMR, ensure parameters are set for optimal SNR. Key optimized parameters for a general 13C experiment include [10]:

- Pulse Program:

zgdc30(for 1H decoupling and NOE enhancement). - Acquisition Time (AQ): 1.0 second.

- Relaxation Delay (D1): 2.0 seconds.

- Number of Scans (NS): 128 or higher as needed.

- 90° Pulse (P1): Calibrated and set correctly.

- Pulse Program:

- Apply Optimal Processing: Use processing functions that enhance SNR without distorting peaks. For 13C, a Gaussian window (GM) with LB = -0.2 and GB = 0.07 can provide narrower lines and slightly better SNR compared to standard exponential multiplication [10].

Technical Variation and Batch Effects

- Problem: Identical samples yield different results across different runs or spectrometers, mimicking poor SNR reproducibility.

- Systematic Quality Control (QC): Implement a rigorous QC pipeline to identify and remove unwanted technical variation. This is critical in large-scale studies [21].

- Monitor Technical Covariates: Track factors such as shipping batch, plate well position, spectrometer ID, and measurement date/time [21].

- Statistical Adjustment: Use a regression-based pipeline to remove the effects of technical covariates like sample degradation time, plate row/column effects, and drift over time within a spectrometer [21].

- Handle Outliers: Systematically identify and remove outlier plates that show non-biological deviations, as these can severely impact specific biomarkers [21].

Incorrect Signal Assignment and Integration

- Problem: Overlapping peaks or poor resolution lead to misassignment of signals and inaccurate integration.

- Use 2D NMR Experiments: Employ correlation spectroscopy such as COSY and HSQC to confirm proton connectivity and resolve ambiguous assignments [26].

- Ensure Proper Relaxation Delays: Use a relaxation delay (D1) longer than 5 times the T1 of the slowest-relaxing nuclei to prevent saturation effects and ensure accurate integration [26].

- Check Processing Parameters: Perform careful phase and baseline correction to avoid artificial signals and distorted integrations [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NMR-based Biomarker Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Synthetic Urine (e.g., Surine) | Provides a consistent, defined matrix for preparing control samples and for method development, free from the biological variability of real urine [18]. |

| Deuterated Solvent (D2O) | Provides the lock signal for the NMR spectrometer and dissolves the sample [18]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., TSP, DSS) | Serves as a chemical shift reference (0 ppm) and can be used for quantification (NIS) [18] [26]. |

| Buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffer) | Maintains a constant pH, which is critical for the stability of metabolites and the reproducibility of chemical shifts [18]. |

| NMR Tubes | High-quality, matched NMR tubes are essential for consistent performance, especially in automated systems [26]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Investigating SNR-CV Relationship Using Synthetic Urine

This protocol is adapted from foundational work on biomarker validation [18].

1. Sample Preparation:

- Prepare five different synthetic urine samples by adding 9-17 small molecule metabolites at concentrations spanning a physiologically relevant range (e.g., 63 µM to 1.1 mM) to a base synthetic urine matrix like Surine [18].

- Add a phosphate buffer (e.g., 0.3 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.2) to stabilize pH.

- Include an internal standard (e.g., Trimethylsilyl propionate, TSP, in D2O) for chemical shift referencing and potential normalization [18].

2. NMR Data Acquisition:

- Acquire NMR spectra for all samples over an extended period (e.g., eight months) to assess long-term instrumental reproducibility [18].

- Use standard 1D NMR pulse sequences with water suppression.

- Record all relevant acquisition parameters.

3. Data Analysis:

- Pre-processing: Apply different normalization methods (Quotient Normalization, Normalization to Total Intensity, Normalization to an Internal Standard, and No Normalization) to the spectral data [18].

- SNR Calculation: For each metabolite resonance peak, calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio.

- CV Calculation: For each peak, compute the Coefficient of Variation (relative standard deviation) across the multiple measurements over time [18].

- Statistical Analysis: Group peaks by their SNR and analyze the relationship between SNR and CV for each normalization method. The inverse log10 dependence between SNR and CV can be modeled [18].

Protocol: Quality Control and Removal of Technical Variation

This protocol is based on procedures developed for the UK Biobank NMR metabolomics data [21].

1. Data Collection and Logging:

- Systematically record all technical covariates, including: shipping batch, 96-well plate ID, well position, aliquoting robot, aliquot tip, spectrometer ID, and date/time stamps for each step in the sample processing and measurement pipeline [21].

2. Quality Control Pipeline:

- Log Transformation: Apply a log transformation to the original biomarker concentrations to stabilize variance.

- Remove Sample Degradation Effects: Regress out the effect of the time between sample preparation and measurement (on a log scale) using robust linear regression.

- Remove Plate Position Effects: Sequentially regress out the effects of plate row (categorical) and plate column (categorical) from the residuals.

- Remove Intra-Spectrometer Drift: Bin plates by measurement date within each spectrometer and regress out this bin effect as a categorical variable.

- Rescale and Remove Outliers: Rescale the final residuals to the distribution of the original data. Systematically identify and remove entire outlier plates that show strong non-biological deviations [21].

3. Validation:

- Compare the median Coefficient of Variation (CV%) and coefficient of determination (R²) between blind duplicate samples before and after the QC procedure. A successful application should reduce CV% and increase R² [21].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

Impact Pathway of Poor SNR

SNR Optimization Workflow

Practical Strategies for SNR Enhancement: From Parameter Adjustment to Advanced Coil Design

Optimizing Receiver Gain (RG) to Maximize Signal While Avoiding ADC Overflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is Receiver Gain (RG) and why is it critical for NMR sensitivity? The Receiver Gain (RG) is a parameter that matches the dynamic range of the NMR signal recorder to the strength of the expected signal. It is crucial because it directly impacts the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). A higher RG amplifies the signal, but if set too high, it can cause ADC overflow, which clips the signal and introduces artifacts. Finding the optimal RG is therefore essential for maximizing sensitivity and obtaining reliable data [5].

What does the "ADC Overflow" error mean, and how should I resolve it? An "ADC Overflow" error means that the amplified NMR signal has exceeded the maximum voltage that the Analog-to-Digital Converter (ADC) can accurately digitize. This leads to a clipped Free Induction Decay (FID) and severe spectral distortions [5] [13].

- Immediate fix: Reduce the RG value. If you used automatic gain adjustment (

rga), try setting RG to a lower, fixed value [27]. - Proactive troubleshooting: For 2D experiments like HSQC, the automatic RG adjustment (

rga) can be unreliable. It is recommended to determine a suitable RG from a 1D experiment and manually set it for the 2D experiment, changing the automation program toau_zgonlyto preventrgafrom running [27].

Why can't I always trust the automatic RG adjustment? While convenient, automatic RG adjustment is programmed primarily to avoid signal overflow, not to maximize the SNR. Recent research on Bruker Avance NEO systems has revealed that the relationship between RG and SNR is not always straightforward. For some nuclei (e.g., 13C, 15N), the SNR can drop drastically at certain RG values. For example, one study found that for 13C on a 9.4 T spectrometer, an RG of 20.2 resulted in a 32% lower SNR compared to the value at RG=18. This non-optimal value might still be chosen by automatic routines, underscoring the need for manual calibration for critical experiments [28] [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: ADC Overflow Error or "DRU Warning" in TopSpin

Symptoms: You receive an error message such as "zg: DRU warning: n ADC-overflow warnings during acquisition (DRU1)!" or a pop-up stating "ADC Overflow." The acquired FID may appear clipped, and the resulting spectrum has a distorted baseline or spurious peaks [27].

Resolution Steps:

- Immediately reduce the RG: Manually set the RG to a lower value. If the current RG is very high (e.g., 2050), try reducing it to 1030 or 600 [27].

- Reset the hardware: After an ADC overflow error, it may be necessary to type

ii restartin TopSpin to reset the hardware interface [13]. - Check probe tuning: A poorly tuned probe has reduced sensitivity, which can cause the automatic gain routine to set an incorrectly high RG. Ensure the probe is properly tuned and matched before running the RG adjustment [27].

- Adjust pulse parameters: If reducing the RG is insufficient, you can reduce the excitation pulse width (

pw) or the transmitter power (tpwr) to decrease the initial signal amplitude [29]. - For 2D experiments: Avoid using

rga. Instead, determine the optimal RG from a corresponding 1D experiment and set it manually. Change the automation program (AUNM) toau_zgonly[27].

Issue: Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio Despite High Receiver Gain

Symptoms: The spectrum is acquired without ADC overflow errors, but the SNR is lower than expected, making it difficult to distinguish weak peaks from noise.

Resolution Steps:

- Calibrate the RG for your specific system: Do not assume that a higher RG always gives a better SNR. The relationship is system- and nucleus-dependent [5].

- Perform an RG sweep experiment: Acquire a series of 1D spectra of your sample or a standard, incrementing the RG value for each acquisition while keeping all other parameters constant.

- Measure and plot SNR vs. RG: Process the spectra identically. For each spectrum, measure the signal intensity (peak height or area) and the noise (in a signal-free region), then calculate the SNR.

- Identify the optimal RG: Plot SNR as a function of RG. The optimal value is at the peak of this curve, not necessarily at the maximum RG. Studies have shown that for X-nuclei, the maximum SNR is often reached at a modest RG (e.g., between 10 and 18), far below the maximum available value [5] [30].

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent research on RG optimization across different spectrometers and nuclei [5] [30].

Table 1: Example of Non-Linear SNR Behavior on a 9.4 T Spectrometer (Bruker Avance NEO)

| Nucleus | Receiver Gain (RG) | Relative SNR | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13C | 18 | ~100% | Maximum or near-maximum SNR achieved. |

| 13C | 20.2 | ~68% | SNR dropped significantly by 32%. |

| 13C | 101 (Max) | ~100% | SNR similar to RG=18, but with higher risk of signal compression. |

Table 2: Signal Amplitude Deviation on a 1 T Benchtop Spectrometer (Magritek Spinsolve)

| Nucleus | Maximum Observed Signal Deviation |

|---|---|

| 1H | Up to 50% |

| 13C | Up to 50% |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determining the Optimal Receiver Gain (RG)

Objective: To empirically determine the RG value that maximizes the SNR for a specific nucleus and spectrometer configuration.

Materials:

- NMR spectrometer

- Standard reference sample (e.g., 1% ethylbenzene for 1H, 13C-labeled compound for heteronuclei)

- Standard 5 mm NMR tube

Method:

- Prepare the system: Insert the sample, lock, tune the probe for the nucleus of interest, and shim to optimal resolution.

- Set up a standard 1D experiment: Use a pulse program (e.g.,

zgfor 1H). Set parameters like spectral width (sw), relaxation delay (d1), and acquisition time to standard values. Use a 90-degree pulse if possible. - Disable automatic RG: Set

rgto a low starting value (e.g., 1 or 10). - Acquire the first spectrum: Run the experiment with a single scan.

- Increment the RG: Increase the

rgvalue systematically. On Bruker systems, common steps are between 1 and 101. Record the exact RG value used for each experiment. - Repeat acquisition: For each new RG value, run the experiment again with identical parameters. A typical sweep might include RG values of 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, 25, 30, 40, 60, 80, and 101 [30].

- Process the data: Process all FIDs identically (same window function, line broadening, phase correction, and baseline correction).

- Data analysis: For each spectrum:

- Measure Signal: Integrate a well-resolved peak or use its height.

- Measure Noise: Calculate the root-mean-square (RMS) noise in a region of the spectrum where no signals are present.

- Calculate SNR: Divide the signal by the noise.

- Plot and interpret: Create a plot of SNR versus the set RG value. The RG that corresponds to the highest SNR is the optimal value for your system and nucleus.

This workflow for determining the optimal Receiver Gain can be visualized as follows:

Protocol: Estimating Parameters for Hyperpolarized Samples

Objective: To estimate safe and effective RG and flip angle (α) settings for transiently hyperpolarized samples to avoid ADC overflow while preserving SNR.

Method:

- Know your system's maximum signal (Sm): This is the ADC overflow threshold, often set conservatively at 50% of the receiver range threshold (RRT) to avoid signal compression [5].

- Estimate the expected signal: The maximum signal from a hyperpolarized sample can be estimated by:

Signal = A · f(RG) · sin(α) · P · CWhere:Ais a hardware-specific constant.f(RG)is the receiver gain function.αis the excitation flip angle.Pis the nuclear polarization.Cis the spin concentration [5].

- Constrain the experiment: The estimated signal must be less than the maximum recordable signal:

Signal ≤ Sm. - Choose parameters: Using the estimated polarization and concentration, choose a combination of a low flip angle (α) and an RG value (determined from your RG-SNR calibration) that satisfies the overflow constraint while providing sufficient SNR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Receiver Gain and Sensitivity Optimization Experiments

| Item | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Sample | A sample of known concentration and structure (e.g., 1% Ethylbenzene in CDCl3 for 1H, 13C-labeled compound) used to calibrate RG and measure SNR consistently. |

| High-Frequency NMR Tubes | Specially manufactured NMR tubes (e.g., rated for ≥500 MHz) are essential for high-field spectrometers to prevent magnetic susceptibility distortions that degrade line shape and SNR [13]. |

| Deuterated Solvent | Provides a lock signal for the magnetic field stabilization. The choice of solvent must be correctly selected in the software for accurate chemical shift referencing and locking [29] [13]. |

| Cryogenically Cooled Probe | A probe where the receiver coil and/or electronics are cooled with cryogenic gases to reduce thermal noise, thereby significantly increasing SNR [28]. |

What is the fundamental relationship between scan number and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in NMR? The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in NMR spectroscopy improves with the square root of the number of scans (also known as transients or signal averages) acquired. This is a fundamental principle of signal averaging, which leverages the different behaviors of the coherent NMR signal and random electronic noise. The coherent signal adds linearly with the number of scans (N), while the random noise adds as the square root of N (√N). Therefore, the overall SNR increases by a factor of √N [8].

The relationship is summarized by the equation:

SNRN = SNR1 × √N

where SNR1 is the signal-to-noise ratio for a single scan, and SNRN is the signal-to-noise ratio after N scans [8].

Key Concepts & Quantitative Data

SNR Improvement Table

The following table illustrates how the SNR improves with an increasing number of scans based on the square root dependence. The "Practical Implication" column shows the multiplier for the total experiment time required to achieve a similar SNR gain on a spectrometer with lower inherent sensitivity.

| Number of Scans (N) | SNR Multiplier (√N) | Practical Implication: Time Cost for Equivalent Gain on Less Sensitive Instrument |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.0 | Baseline |

| 4 | 2.0 | 4x longer experiment time [8] |

| 16 | 4.0 | 16x longer experiment time [8] |

| 64 | 8.0 | 64x longer experiment time |

| 256 | 16.0 | 256x longer experiment time |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for SNR Optimization

The following reagents and materials are crucial for preparing samples and conducting experiments to maximize SNR.

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl\u2083, DMSO-d\u2086) | Provides a signal for the instrument's lock system to maintain magnetic field stability. Essential for achieving high resolution [31]. |

| Reference Sample (e.g., 1% Ethylbenzene in CDCl\u2083) | A standardized sample used to quantitatively measure and compare the sensitivity (SNR) of an NMR spectrometer according to established protocols [8]. |

| Internal Chemical Shift Standard (e.g., TMS) | Tetramethylsilane (TMS) is the primary reference standard for calibrating the 0 ppm point in both \u00b9H and \u00b9\u00b3C NMR spectra [32]. |

| High-Quality NMR Tubes | Matched 5 mm NMR tubes are critical for optimal magnetic field homogeneity (shimming). Using "high-frequency" rated tubes is recommended for high-field spectrometers (e.g., 600 MHz) to avoid poor resolution and shimming difficulties [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Measuring ¹H NMR Sensitivity

This protocol is used to determine the intrinsic sensitivity of an NMR instrument, which is a key benchmark for planning signal-averaging experiments [8].

- Sample Preparation: Use a certified reference sample of 1% (v/v) ethylbenzene in CDCl\u2083 containing 0.1% TMS.

- Acquisition Parameters:

- Pulse Sequence: 1D proton (pulse-acquire)

- Pulse Flip Angle: 90 degrees

- Acquisition Time (AQ): > 1 second

- Relaxation Delay (D1): > 60 seconds (ensures full relaxation between scans)

- Number of Scans (NS): 1

- Data Processing: Process the Free Induction Decay (FID) using 1.0 Hz of exponential line broadening (apodization). No resolution enhancement functions should be applied.

- SNR Calculation: Measure the SNR of the tallest peak in the methylene quartet (around 2.65 ppm). The RMS noise should be calculated from a signal-free region of the spectrum (e.g., between the methylene and aromatic signals). Avoid using the aromatic signals for this calculation, as it will give a falsely high SNR [8].

Protocol for Optimizing Signal Averaging in Routine ¹H NMR

For daily experiments, a balance between SNR and experiment time is key. Modern spectrometers often have optimized parameter sets for this purpose [33].

- Parameter Set Selection:

- For a single scan (NS=1): Use a parameter set like

PROTON1. This employs a 90° excitation pulse (PULPROG=ZG) and a long relaxation delay (e.g., 17 seconds on a 400 MHz instrument) to ensure complete relaxation and quantitatively reliable integrals. - For multiple scans (NS>1): Use a parameter set like

PROTON8. This employs a 30° excitation pulse (PULPROG=ZG30) and a shorter relaxation delay (e.g., 1.5 seconds). The smaller flip angle requires less time for spin recovery, allowing for more scans to be accumulated in a shorter total time without saturating the signal.

- For a single scan (NS=1): Use a parameter set like

- Determining Scans Needed: Use the relationship SNRN = SNR1 × √N to estimate the number of scans required to achieve a desired SNR. For example, to double your SNR, you need to acquire 4 scans [8].

- Total Experiment Time: The total time of an experiment is approximately NS × (AQ + D1). Adjust NS and D1 based on your SNR requirements and time constraints [33].

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

FAQ: Why are my integrals unreliable even after many signal averages? Integral accuracy is primarily affected by incomplete spin-lattice (T1) relaxation between scans, not directly by the number of scans. If the relaxation delay (D1) is too short, nuclei do not fully recover to equilibrium before the next pulse, leading to signal saturation and reduced integral accuracy. For quantitative integrals with multiple scans, ensure AQ + D1 is sufficiently longer than the T1 of the nuclei of interest. For the most reliable integrals in a single scan, use a long D1 (e.g., 17-60 seconds) [33].

FAQ: I increased the scans, but my SNR is worse than expected. What is wrong? Deviations from the ideal √N improvement can stem from several factors:

- Incorrect Receiver Gain (RG): A poorly set RG can drastically reduce SNR. Surprisingly, the maximum RG value does not always provide the best SNR. One study found that for ¹³C on a 9.4 T spectrometer, an RG of 18 provided a 32% better SNR than the maximum RG of 101. Always test and calibrate the optimal RG for your specific system and nucleus [5].

- Poor Magnetic Field Homogeneity: Inadequate shimming leads to broadened peaks, which lowers their amplitude and thus the SNR. A well-shimmed magnet is a prerequisite for effective signal averaging [8].

- Probe Tuning/Matching: Variations in sample dielectric constant can detune the probe, reducing the efficiency of the RF pulse. The probe should be tuned for each new solvent [31].

Troubleshooting: ADC Overflow Error

- Symptom: The experiment fails with an "ADC overflow" error, or the resulting spectrum has severe distortions.

- Cause: The receiver gain (RG) is set too high, causing the analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to be overwhelmed by the signal intensity [13].

- Solution:

- Manually set the RG to a lower value.

- If using automated RG adjustment (

rga), note that the suggested value can sometimes be too high. If an overflow occurs, restart the hardware withii restartand set a lower, manual RG value [13]. - Always monitor the first scan of an experiment to ensure the FID is not clipped.

Troubleshooting: Poor Resolution and Broad Lines

- Symptom: Peaks are broad even after signal averaging, limiting resolution and SNR.

- Cause: The main magnetic field (B₀) is inhomogeneous, meaning the shimming is sub-optimal [13] [31].

- Solution:

- Ensure your sample is prepared correctly—use a high-quality NMR tube filled to the standard height.

- Check for air bubbles or insoluble particles in the sample.

- Perform a shimming routine (e.g.,

topshim). Start from a good, recent shim file (rshcommand) and re-optimize the shims, particularly the Z, X, Y, XZ, and YZ shims [13].

Workflow and Conceptual Diagrams

Signal Averaging Optimization Workflow

Square Root Dependence Conceptual Diagram

Implementing Apodization and Post-Processing Techniques for Noise Reduction

The pursuit of an optimal Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a central challenge in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, directly impacting the detection limits, accuracy, and reliability of results in chemical and biochemical research. While hardware advancements continue to push the boundaries of sensitivity, the intelligent application of post-processing techniques remains a critical and accessible means to enhance data quality. This guide, framed within broader thesis research on optimizing the NMR SNR, provides a practical technical resource. It addresses common experimental hurdles and details the implementation of post-processing methods, notably apodization, which serve to maximize the useful information extracted from acquired data, thereby supporting robust scientific conclusions in fields like drug development [34] [5].

Fundamental Concepts: SNR and Post-Processing

The SNR is a cornerstone metric in NMR, quantifying the strength of the desired signal relative to the background noise. A low SNR can obscure spectral details and compromise quantitative analysis. Post-processing encompasses the digital manipulation of the Free Induction Decay (FID)—the raw time-domain signal—after data acquisition to improve the final frequency-domain spectrum [34].

A key relationship exists between the FID and the spectrum, governed by the Fourier Transform. Parameters of the FID, such as its decay rate, directly influence the appearance of the spectrum, including line widths and the noise level. Post-processing techniques strategically alter the FID to emphasize certain characteristics before it is transformed into the final spectrum [34].

The following table summarizes the core components involved in the NMR signal pathway that are essential for SNR optimization.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Materials for NMR SNR Optimization

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvent | Provides a lock signal for the magnetic field stability and dissolves the sample. Common examples include CDCl₃ or D₂O [29]. |

| Chemical Shift Reference | An internal standard (e.g., TSP or DSS) added to the sample for precise chemical shift referencing, which is crucial for correct compound identification and spectral alignment [35]. |

| NMR Tube | A high-quality, specific tube is required to hold the sample. For high-field spectrometers (≥500 MHz), using appropriate "high-frequency" NMR tubes is essential to avoid poor shimming and resolution issues [13]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: What is apodization and how does it help with noise reduction?

Answer: Apodization, or weighting, is the process of multiplying the FID by a mathematical function to improve either the sensitivity (SNR) or the resolution of the final spectrum. This process inherently involves a trade-off; enhancing one typically comes at the expense of the other.

- For Sensitivity Improvement: A matched filter, such as an exponential function, is applied. This function suppresses the later part of the FID where the signal has decayed and the noise is more prominent, thereby reducing the overall noise level in the spectrum [36].

- For Resolution Enhancement: A function like the Lorentz-to-Gauss transformation is used. It suppresses the early, intense part of the FID and emphasizes the later part, which can narrow the linewidths in the spectrum, making it easier to distinguish closely spaced peaks [36].

FAQ 2: I keep getting an "ADC Overflow" error. What should I do?

Answer: An "ADC Overflow" error indicates that the signal intensity has exceeded the maximum input range of the analog-to-digital converter (ADC). This can result in a clipped FID and severe spectral artifacts [5].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce the Receiver Gain (RG): This is the most direct solution. Manually set the RG to a lower value. On some systems, even if the automatic gain adjustment (

rga) suggests a high value, setting RG to a value in the low hundreds can resolve the issue [13]. - Reduce Pulse Power: Lower the pulse width (

pw) or the transmitter power (tpwr). This tips a smaller portion of the magnetization into the transverse plane, generating a weaker signal and preventing overflow [29]. - Check Sample Concentration: If the sample is overly concentrated, consider dilution for future experiments [29].

FAQ 3: My spectrum has a poor signal-to-noise ratio even after many scans. What post-processing options do I have?

Answer: Beyond increasing the number of scans, several post-processing techniques can improve SNR:

- Apodization: Apply an exponential function (e.g., line broadening) to the FID. This acts as a noise filter [36].

- Zero Filling: This increases the number of data points in the FID before Fourier Transform, leading to a smoother-looking spectrum, which can make it easier to distinguish small signals from noise [37].

- Spectral Processing Software: Utilize advanced software features. Modern packages like Mnova NMR incorporate algorithms, including AI-powered peak picking and baseline correction, which can help accurately identify and quantify signals in noisy data [37].

FAQ 4: How can I verify that my receiver gain is set optimally for the best SNR?

Answer: Contrary to the assumption that the highest possible RG (without causing overflow) always yields the best SNR, recent research shows that SNR behavior can be non-monotonic and system-dependent.

Experimental Protocol for RG Calibration:

- Prepare a standard sample of known concentration.

- Acquire a series of identical experiments, changing only the RG value across a wide range (e.g., from the minimum to the maximum).

- Process all spectra identically using consistent apodization and processing parameters.

- Measure the Signal and Noise: For each spectrum, measure the amplitude of a specific peak (Signal) and the standard deviation of a region containing only noise.

- Calculate and Plot SNR: Calculate SNR (Signal/Noise) for each RG value and plot SNR versus RG. The optimal RG is the value that provides the highest SNR, which may not be the maximum RG [5].

Table 2: Quantitative SNR and Signal Response to Receiver Gain (RG) on Different Spectrometers

| Nucleus / System | Observed SNR and Signal Behavior | Recommended Optimal RG |

|---|---|---|

| 1 T Benchtop (e.g., Magritek) | Signal intensity deviated by up to 50% from expected values; SNR increased with RG but with non-linear signal response [5]. | System-specific calibration required. |

| High-Field Bruker (e.g., 9.4 T) | For ¹³C, a drastic, non-linear drop in SNR was observed. SNR at RG=18 was similar to maximum, but at RG=20.2 it was 32% lower, despite higher signal amplitude [5]. | ~18 (for ¹³C at 9.4 T). |

| General High-Field Systems | Signal intensity increases linearly with RG, but the noise function is non-trivial, leading to an unexpected SNR peak at modest RG values for some X-nuclei [5]. | 10-18 for many X-nuclei (far below the maximum of 101). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Apodization Functions

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal apodization function and parameters for a given NMR dataset to achieve the best balance between sensitivity and resolution.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a standard 1D ¹H NMR spectrum of a sample containing both well-resolved and closely spaced peaks.

- Initial Processing: Apply a standard Fourier Transform without any apodization to establish a baseline spectrum.

- Sensitivity Enhancement:

- In your processing software, apply an exponential apodization function (often called Line Broadening, or

LB). - Start with a small value (e.g.,

0.3 Hz) and gradually increase it (e.g.,1.0 Hz,3.0 Hz). - After each adjustment, apply the processing and note the change in the noise level and the broadening of the peaks.

- In your processing software, apply an exponential apodization function (often called Line Broadening, or

- Resolution Enhancement:

- Apply a resolution-enhancing function such as Gaussian multiplication (e.g.,

GMorGBfunctions in many software packages). - Adjust the parameters to control the narrowing of peaks. Be cautious, as excessive resolution enhancement can introduce truncation artifacts and degrade SNR [36].

- Apply a resolution-enhancing function such as Gaussian multiplication (e.g.,

- Comparative Analysis: Compare the processed spectra to identify which set of parameters provides the most suitable trade-off for your analytical goal.

Software Note: Tools like the apodization slider in JASON software automate this trial-and-error process by allowing users to interactively slide between "Best Sensitivity" and "Best Resolution" settings, providing immediate visual feedback [36].

Protocol 2: Calibrating Receiver Gain for Maximum SNR

Objective: To experimentally determine the receiver gain (RG) setting that yields the maximum Signal-to-Noise Ratio for a specific nucleus on a specific spectrometer.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Use a stable, standard reference sample with a known concentration of the nucleus of interest (e.g., ¹H in TMS, ¹³C in a labeled compound).

- Parameter Setup: Define a standard 1D pulse sequence. Set the number of scans (

NS) to a value that provides a measurable signal in a reasonable time. - Data Collection Series:

- Set the receiver gain (

RG) to its minimum value and run the experiment. - Increment the

RGby a fixed step (e.g., 5-10 units) and repeat the experiment. Continue this process until you reach the maximumRGor consistently trigger ADC Overflow.

- Set the receiver gain (

- Data Processing: Process all FIDs identically using the same apodization, zero-filling, and baseline correction parameters.

- SNR Calculation:

- For each spectrum, measure the Signal as the height of a chosen, isolated peak.

- Measure the Noise as the root mean square (RMS) or standard deviation in a signal-free region of the spectrum.

- Calculate SNR = Signal / Noise for each RG value.

- Plot and Interpret: Create a plot of SNR versus RG. The optimal RG is the value at which the SNR peaks. Use this calibrated value for future quantitative experiments on that nucleus and system [5].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting and applying key noise reduction and processing techniques covered in this guide.

NMR Noise Reduction Workflow