Miniaturization Strategies for Greener Spectroscopy: Sustainable Analytical Solutions for Biomedical Research

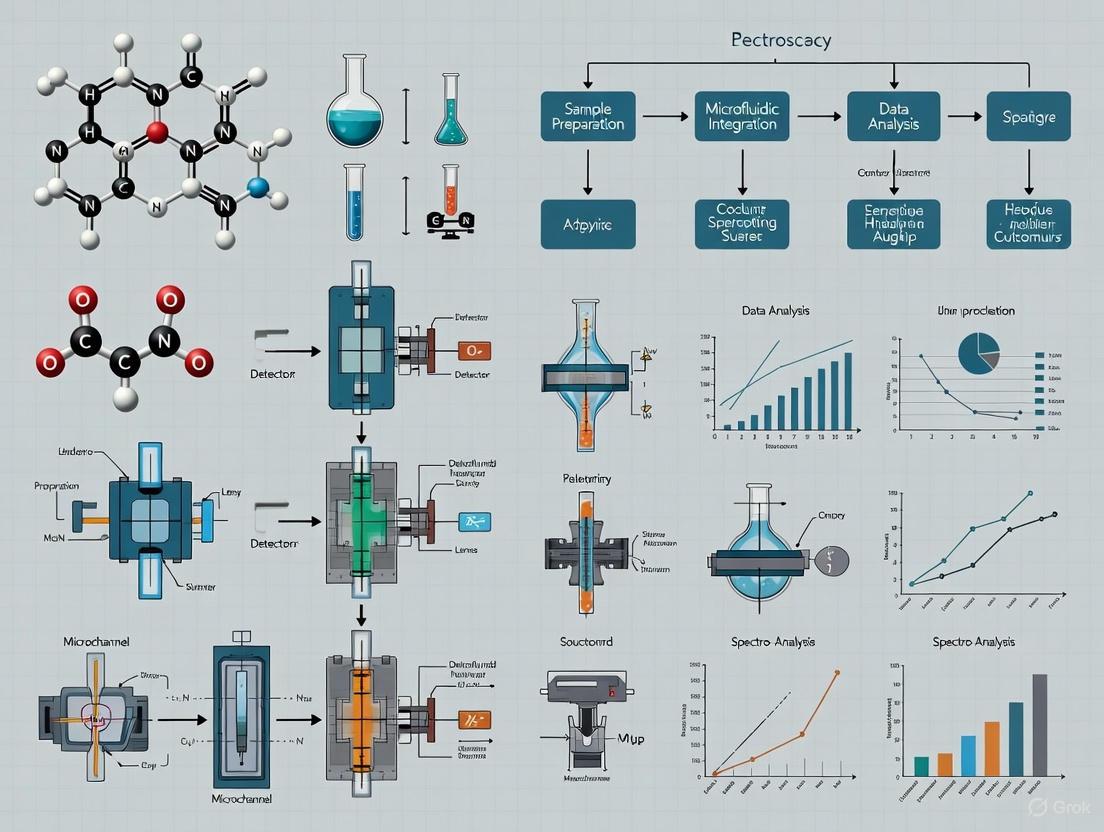

This article explores the integration of miniaturization strategies with spectroscopic techniques to advance Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles within biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Miniaturization Strategies for Greener Spectroscopy: Sustainable Analytical Solutions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the integration of miniaturization strategies with spectroscopic techniques to advance Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles within biomedical and pharmaceutical research. It examines the foundational shift from traditional methods to portable, resource-efficient technologies like lab-on-a-chip devices, reconstructive spectrometers, and miniaturized separation systems. The scope spans methodological applications in drug discovery and impurity profiling, addresses key optimization challenges for robust implementation, and provides comparative validation against conventional instrumentation. By synthesizing current advancements and practical considerations, this review serves as a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance sustainability without compromising analytical performance.

The Green Imperative: Core Principles and Technologies Driving Spectroscopy Miniaturization

Defining Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) in Pharmaceutical Contexts

Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) is a specialized discipline that integrates the principles of green chemistry into analytical methodologies. Its primary goal is to minimize the environmental and human health impacts traditionally associated with chemical analysis in pharmaceutical development and quality control [1] [2]. GAC transforms analytical workflows by optimizing processes to ensure they are safe, non-toxic, environmentally friendly, and efficient in their use of materials, energy, and waste generation [1].

The foundation of GAC rests on the 12 principles of green chemistry, which provide a comprehensive framework for designing and implementing environmentally benign analytical techniques [2]. These principles emphasize waste prevention, the use of renewable feedstocks, energy efficiency, atom economy, and the avoidance of hazardous substances [2]. In the pharmaceutical industry, this translates to reimagining traditional analytical methods—which often rely on toxic reagents and solvents—into safer, more sustainable practices that reduce ecological footprints while maintaining high standards of accuracy and precision [1] [3].

Core Principles and Strategic Framework

The 12 principles of GAC provide a strategic roadmap for developing sustainable analytical methods in pharmaceutical contexts. The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between core GAC principles and their implementation outcomes in pharmaceutical analysis.

The implementation of these principles drives significant operational benefits. Miniaturization stands as a cornerstone strategy, dramatically reducing sample and reagent consumption while maintaining analytical performance [4] [3]. The use of alternative solvents like water, supercritical carbon dioxide, ionic liquids, and bio-based replacements directly addresses one of the largest sources of hazardous waste in traditional pharmaceutical analysis [3] [2]. Meanwhile, energy-efficient techniques such as microwave-assisted and ultrasound-assisted processes lower operational carbon footprints, and real-time analysis enables immediate decision-making that prevents pollution at its source [2].

GAC Methodologies and Miniaturization Strategies

Miniaturized Analytical Techniques

Miniaturized analytical techniques are revolutionizing pharmaceutical testing by offering sustainable and efficient alternatives to traditional methods [4]. These approaches align perfectly with GAC principles by significantly reducing sample and reagent consumption, minimizing waste generation, and accelerating analysis times [4] [3]. The following table summarizes key miniaturization technologies and their pharmaceutical applications.

Table 1: Miniaturized Analytical Techniques for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Technique Category | Specific Technologies | Pharmaceutical Applications | Key Green Benefits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Miniaturized Sample Preparation | Solid-phase microextraction (SPME), Liquid-phase microextraction, Stir-bar sorptive extraction [4] | Sample clean-up, analyte concentration, impurity profiling [4] | Decreased solvent usage, improved sample throughput, enhanced sensitivity [4] |

| Miniaturized Separation | Capillary electrophoresis, Microchip electrophoresis, Nano-liquid chromatography [4] | Analysis of complex pharmaceutical matrices, chiral separations, biomolecule analysis [4] | Exceptional separation efficiency, minimal sample requirements, reduced operational costs [4] |

| Lab-on-a-Chip & Portable Systems | Microfluidic chips, Portable spectrometers, Hand-portable LC systems [3] [4] | On-site testing, reaction monitoring, point-of-care diagnostics [3] | Reduced transportation needs, minimal sample preservation, lower carbon footprint [3] |

Implementation Workflow

Implementing miniaturized strategies requires a systematic approach. The following workflow diagram outlines a standard methodology for transitioning from traditional to miniaturized GAC approaches in pharmaceutical analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the easiest way to start making our pharmaceutical analysis lab more environmentally safe? [3] A1: Begin by implementing simple changes like minimizing solvent use in routine procedures, exploring micro-scale techniques for common assays, and properly sorting and recycling lab waste. These initial steps can significantly reduce environmental impact with minimal investment [3].

Q2: Are green chemistry methods as accurate and reliable as traditional pharmaceutical analysis techniques? [3] A2: Yes. While validation is crucial for new methods, modern eco-friendly analysis techniques have been developed to provide results that are just as accurate and reliable as traditional methods, often with added benefits like increased speed and reduced operational costs [3].

Q3: How can we evaluate and compare the greenness of different analytical methods? [5] A3: Several standardized metrics are available, including the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) tool and the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI). These tools offer comprehensive assessments based on the 12 principles of GAC, providing scores and visual outputs that facilitate comparison between methods [1] [5].

Q4: What are the most significant barriers to adopting GAC in pharmaceutical settings? A4: The primary challenges include method validation requirements, initial investment in new equipment, and the need for training and education. However, these are outweighed by long-term benefits including enhanced safety, cost savings, improved efficiency, and better regulatory compliance [3].

Troubleshooting Common GAC Implementation Issues

Issue 1: Poor separation efficiency after transitioning to nano-liquid chromatography [4]

- Potential Cause: Column clogging due to inadequate sample clean-up or incompatible flow rates.

- Solution: Implement miniaturized sample preparation techniques such as solid-phase microextraction to remove particulates and matrix interferents. Optimize flow rate parameters for the specific column dimensions.

Issue 2: Inconsistent results with microextraction techniques [4]

- Potential Cause: Variable extraction times or insufficient conditioning of extraction phases.

- Solution: Standardize extraction timing using automated systems and establish rigorous conditioning protocols. Ensure consistent sample agitation or stirring rates.

Issue 3: Signal deterioration in portable spectroscopy devices [3]

- Potential Cause: Environmental factors affecting instrument performance or inadequate calibration transfer from benchtop methods.

- Solution: Implement regular field calibration checks using stable reference materials. Develop method transfer protocols that account for differences between laboratory and portable instrumentation.

Greenness Assessment Tools and Metrics

Evaluating the environmental sustainability of analytical methods is essential for implementing GAC in pharmaceutical contexts. Several standardized metrics have been developed to quantify and compare the greenness of analytical methods [5]. The following table compares the most widely used GAC assessment tools.

Table 2: Green Analytical Chemistry Assessment Metrics and Tools

| Assessment Tool | Key Characteristics | Output Format | Pharmaceutical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEMI (National Environmental Methods Index) [5] | Early tool using a quadrant pictogram; assesses persistence, bioaccumulation, toxicity, and waste [1] | Simple pass/fail pictogram | Initial screening of method environmental impact [1] |

| GAPI (Green Analytical Procedure Index) [5] | Comprehensive evaluation of entire method lifecycle from sampling to waste [1] | Color-coded pictogram (5 parameters) | Comparative assessment of HPLC/UPLC methods for drug analysis [1] |

| AGREE (Analytical GREEnness) [5] | Holistic assessment based on all 12 GAC principles with weighting capability [1] | Circular pictogram with numerical score (0-1) | Overall greenness scoring for pharmaceutical methods; supports sustainability claims [1] |

| Analytical Eco-Scale [5] | Penalty-point system based on reagent toxicity, energy consumption, and waste [5] | Numerical score | Quantitative greenness evaluation for laboratory method development [5] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Implementing GAC in pharmaceutical analysis requires specific reagents and materials that enable miniaturization and reduce environmental impact. The following table details key solutions for greener pharmaceutical analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Green Analytical Chemistry

| Reagent/Material | Function in GAC | Traditional Alternative | Key Green Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bio-based Solvents (e.g., ethanol, limonene) [3] [2] | Extraction and chromatography mobile phases | Halogenated solvents (e.g., chloroform, dichloromethane) | Renewable feedstocks, biodegradable, lower toxicity [3] [2] |

| Ionic Liquids [3] [2] | Designer solvents for selective extraction | Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) | Non-volatile, recyclable, tunable properties [3] [2] |

| Supercritical CO₂ [3] [2] | Extraction and chromatography solvent | Organic solvent mixtures | Non-toxic, non-flammable, easily removed from products [3] [2] |

| Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME) Fibers [4] [3] | Solventless sample preparation and concentration | Liquid-liquid extraction | Minimal solvent use, reusable, easy automation [4] [3] |

| Microfluidic Chip Substrates [4] | Miniaturized analysis platforms | Conventional lab glassware | Ultra-low reagent consumption, integrated processes [4] |

Green Analytical Chemistry represents a fundamental shift in how pharmaceutical analysis is conducted, emphasizing environmental stewardship, sustainability, and efficiency without compromising data quality [2]. By embracing miniaturization strategies, alternative solvents, and energy-efficient technologies, pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals can significantly reduce the environmental footprint of their analytical workflows while maintaining the high standards required for regulatory compliance [4] [3].

The integration of GAC principles, supported by standardized assessment metrics and innovative reagent solutions, positions the pharmaceutical industry to meet growing sustainability demands while continuing to advance medicinal innovation [6] [2]. As GAC methodologies continue to evolve, they offer a clear pathway toward more sustainable pharmaceutical development that aligns with global environmental objectives [7] [8].

The Synergy Between Miniaturization and Sustainability Goals

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Technical Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Problems in Miniaturized Spectroscopy and Chromatography

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Green Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality | Noisy spectra or chromatograms | Instrument vibrations from nearby equipment [9]. | Relocate spectrometer to stable surface, use vibration-damping mounts [9]. | Prevents repeated analyses, saving energy and reagents. |

| Negative peaks in ATR-FTIR | Dirty or contaminated ATR crystal [9]. | Clean crystal with appropriate solvent, acquire new background scan [9]. | Maintains data integrity, avoiding sample re-preparation and waste. | |

| Distorted baseline in diffuse reflection | Data processed in absorbance units [9]. | Convert data to Kubelka-Munk units for accurate representation [9]. | Ensures correct first-time analysis, conserving resources. | |

| System Operation | Inconsistent separation resolution (cLC/nano-LC) | Column blockage or degraded stationary phase. | Implement pre-column filters; flush and re-condition column with compatible solvents. | Extends column lifespan, reducing solid waste. |

| Poor sensitivity | Low light throughput (Spectroscopy) | Incorrect integration time or obstructed slit [10]. | Increase integration time for low light; ensure slit is not obstructed [10]. | Optimizes performance without hardware replacement. |

| Connectivity & Power | USB power disconnects | PC entering power-saving mode [10]. | Disable USB selective suspend/power-saving settings on the PC [10]. | Prevents data loss and repeated runs. |

Method-Specific Troubleshooting

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE) and Microchip Electrophoresis

- Problem: Poor peak efficiency or migration time drift.

- Cause: Buffer depletion or evaporation in small-volume reservoirs.

- Solution: Frequently replenish background electrolyte or use sealed vial caps. This aligns with Green Analytical Chemistry by maintaining separation performance without resorting to larger, more wasteful formats [11] [4].

Solid-Phase Microextraction (SPME)

- Problem: Declining extraction efficiency.

- Cause: Sorption of matrix components (e.g., proteins) onto the fiber, fouling the coating.

- Solution: Implement a rigorous cleaning procedure between extractions, validating with a standard. This miniaturized sample preparation strategy uses negligible solvent compared to traditional liquid-liquid extraction [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Concepts

Q1: How does instrument miniaturization directly support sustainability goals in a research lab? Miniaturization directly reduces the consumption of samples and solvents, which is a core principle of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC). Techniques like nano-liquid chromatography (nano-LC) and capillary electrophoresis (CE) can reduce solvent consumption from milliliters per run to microliters, drastically minimizing hazardous waste generation and disposal costs [11] [4]. This also lowers the energy demand of fume hoods and waste management [12].

Q2: What is the "rebound effect" in green analytical chemistry? The rebound effect occurs when the efficiency gains of a greener method are offset by increased usage. For example, a cheap, low-solvent microextraction method might lead a lab to perform significantly more extractions than before, potentially increasing the total volume of chemicals used and negating the initial environmental benefit. Mitigation strategies include optimizing testing protocols to avoid redundant analyses [12].

Technical Specifications

Q3: What is integration time in a mini-spectrometer and how should I set it? The integration time is the duration for which the sensor accumulates light-generated electrical charge. For low light levels, a longer integration time can be set to gather sufficient signal. It is typically adjustable in 1 µs or 1 ms steps. Note that while a longer time improves signal, the sensor's dark noise also increases proportionally [10].

Q4: How is spectral resolution defined for mini-spectrometers? A practical definition is the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of a spectral peak. This is the width of the peak at a point that is 50% of its maximum intensity. FWHM is approximately 80% of the value obtained from the more formal Rayleigh criterion [10].

Q5: How often do mini-spectrometers require wavelength calibration? Due to a lack of moving parts, mini-spectrometers exhibit excellent stability. Manufacturers suggest that wavelength calibration is typically not needed under normal indoor operating conditions. The calibration factors provided at shipment should remain valid. Precision can be checked periodically using calibration lamps with known spectral lines [10].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: On-Site Soil Contaminant Screening Using a Handheld Vis-NIR Spectrometer

This protocol uses visible-near infrared (Vis-NIR) spectroscopy for rapid, green analysis of potentially toxic trace elements (PTEs) like lead and cadmium in soil [13].

Key Reagent Solutions

- Quartz Measurement Cups: Provide minimal spectral interference compared to glass.

- Spectralon Reference Standard: Used for instrument calibration to white baseline.

- Pre-characterized Soil Reference Set: Essential for building and validating chemometric models.

Protocol: Chiral Separation of APIs using Electrokinetic Chromatography (EKC)

This protocol highlights a miniaturized separation technique ideal for sustainable pharmaceutical analysis [11].

Key Reagent Solutions

- Chiral Selectors (e.g., Cyclodextrins): Enable enantiomeric resolution based on selective host-guest interactions.

- High-Purity Buffer Salts: Ensure reproducible migration times and stable electro-osmotic flow.

- Capillary Rinsing Solutions: Sodium hydroxide for regeneration, water for rinsing, and buffer for equilibration.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Miniaturized and Sustainable Analysis

| Item | Function & Sustainable Rationale | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids (e.g., [Bmim]Cl⁻) | Serve as green solvent alternatives with low volatility, reducing inhalational exposure and atmospheric emissions. Can be designed for recyclability [14]. | Coal extraction for sustainable energy research [14]. |

| Biochar | Used in sustainable soil remediation. Its high surface area and functional groups can bind and immobilize contaminants like cadmium, reducing their bioavailability [14]. | Soil remediation and pollution control studies [14]. |

| Novel Chiral Selectors | Enable highly efficient enantiomeric separations in techniques like EKC. This avoids the need for more wasteful preparative-scale chiral chromatography [11]. | Chiral separation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) [11]. |

| Machine Learning Algorithms (e.g., CNN, PLSR) | Not a reagent, but a crucial tool. AI enhances sensitivity and classification accuracy from miniaturized systems, reducing the need for larger, more resource-intensive instruments [14] [13]. | Plastic identification in e-waste [14]; predicting soil contaminants from spectral data [13]. |

| Silica-Based SPME Fibers | A core microextraction tool that concentrates analytes from a sample with zero solvent consumption, aligning perfectly with Green Sample Preparation (GSP) principles [4]. | Pre-concentration of analytes from complex biological or environmental matrices prior to LC or GC analysis [4]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Lab-on-a-Chip and Microfluidics Troubleshooting

Table 1: Common Lab-on-a-Chip Issues and Solutions

| Problem Category | Specific Symptoms | Potential Causes | Solution Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Introduction | Difficulties loading sample, inconsistent flow between runs [15] | Macro-to-micro interfacing challenges, complex user steps [15] | Optimize microfluidics for end-user, simplify user steps, consider lyophilization to minimize steps [15] |

| System Interfacing | Poor electrical, thermal, or optical connections [15] | Improper interfacing between macro-scale systems and micro-scale chip [15] | Ensure reliable electrical/thermal/optical interfaces while minimizing fluidic contact to prevent contamination [15] |

| Material Compatibility | Reduced cell viability, unwanted adsorption, chemical degradation [15] | Material incompatibility (e.g., PDMS absorbing hydrophobic molecules) [16] | Select materials based on biocompatibility, chemical resistance, hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity [15] [16] |

| Manufacturing Scale-Up | Inconsistent device performance when moving to production [15] | Prototyping methods not transferrable to high-volume production [15] | Design for manufacturing from the start, develop pilot production processes, use scalable materials [15] |

| Contamination Control | Analysis drift, poor results, cross-contamination between samples [17] | Fluidic contact contamination, dirty interfaces [17] [15] | Implement proper fluid control and contamination prevention designs [17] |

Portable Spectrometer Troubleshooting

Table 2: Portable Spectrometer Common Failures and Fixes

| Problem Type | Warning Signs | Root Causes | Troubleshooting Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum System Issues (OES) | Low readings for C, P, S; pump noises/smoking; oil leaks [18] | Vacuum pump failure; atmosphere in optic chamber [18] | Monitor pump performance; replace leaking pumps immediately [18] |

| Optical Component Problems | Drifting analysis; frequent recalibration needed; poor results [18] | Dirty windows in front of fiber optic or direct light pipe [18] | Clean optical windows regularly; establish maintenance schedule [18] |

| Sample Preparation Errors | Inconsistent/unstable results; white/milky burns [18] | Contaminated samples; skin oils; quenching in water/oil [18] | Regrind samples with new pads; avoid touching samples; don't quench [18] |

| Probe Contact Issues | Loud analysis sound; bright light escape; no results [18] | Poor surface contact; convex shapes; insufficient argon flow [18] | Increase argon flow to 60 psi; add convex seals; custom pistol heads [18] |

| Contamination (XRF) | Erroneous data; damaged components [19] | Dust/dirt in instrument nose; damaged beryllium window [19] | Regularly replace ultralene window; keep instrument clean during use [19] |

| Component Degradation | Poor results despite proper technique [20] | X-ray tube or detector aging; limited shelf life [20] | Test with reference standard; factory recalibration if needed [20] |

Experimental Protocols

Reference Standard Validation for Portable XRF

Purpose: Verify instrument calibration and performance using reference materials [20].

Materials:

- Factory-provided reference standard (typically stainless steel 2205 or soil cup) [20]

- Isopropyl alcohol and lint-free wipes [20]

- Personal protective equipment

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Clean reference standard with isopropyl alcohol to remove contaminants and oils. Avoid harsh cleaners that may damage surface [20].

- Instrument Setup: Ensure correct assay type is selected (e.g., "Alloys" for metal standards) [20].

- Multiple Measurements: Take ≥10 assays of the reference standard, moving the aperture to different areas on the sample [20].

- Data Analysis: Calculate average elemental results. Verify values fall within specified Min/Max ranges for the standard [20].

- Interpretation: If averages are within range, instrument is properly calibrated. If not, proceed to advanced troubleshooting [20].

Miniaturized Raman Spectrometry for Methanol Quantification

Purpose: Demonstrate high-performance chemical quantification using miniaturized Raman spectrometer [21].

Materials:

- Miniaturized Raman spectrometer with built-in polystyrene reference [21]

- Methanol-water mixtures of known concentrations

- Cuvettes or appropriate sample holders

Procedure:

- System Initialization: Power on the compact Raman system featuring non-stabilized laser diodes and non-cooled small sensors [21].

- Reference Calibration: Utilize the built-in reference channel that collects the Raman spectrum of polystyrene for real-time calibration of Raman shift and intensity [21].

- Sample Loading: Introduce methanol-water mixtures of varying concentrations into the measurement area.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect Raman spectra using the densely packed optics system with 7 cm⁻¹ resolution within 400-4000 cm⁻¹ range [21].

- Quantitative Analysis: Process spectra using the calibrated system to establish quantification curve for methanol content [21].

Surface Cleaning Protocol for Alloy Analysis

Purpose: Ensure accurate elemental analysis by proper surface preparation [20].

Materials:

- Diamond sandpaper or abrasive disks (element-specific)

- Rotary tool with appropriate brushes

- Isopropyl alcohol

- Lint-free wipes

Procedure:

- Inspection: Examine sample for corrosion, debris, or contamination [20].

- Surface Preparation: Remove corrosion using diamond sandpaper or rotary tool. Ensure abrasive material doesn't contain elements that could contaminate analysis (e.g., silicon for Si-sensitive applications) [20].

- Cleaning: Thoroughly clean prepared surface with isopropyl alcohol to remove residual particles [20].

- Verification: Analyze prepared surface, ensuring complete contact and proper instrument settings [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| PDMS (Polydimethylsiloxane) | Flexible, transparent elastomer for LOC prototyping [16] | Air permeable for cell studies; absorbs hydrophobic molecules; limited for industrial scale-up [16] |

| Thermoplastic Polymers (PMMA, PS) | Transparent, chemically inert LOC fabrication [16] | Good chemical resistance; compatible with hot embossing/injection molding for scale-up [16] |

| Paper Substrates | Ultra-low cost diagnostics for limited-resource settings [16] | Enables metabolite detection in urine; extremely low production costs [16] |

| Protective Cartridges (XRF) | Prevents detector contamination from sample particles [22] | Requires regular replacement; type/thickness affects accuracy; use manufacturer-specified cartridges [22] |

| Diamond Abrasives | Sample surface preparation for alloy analysis [20] | Avoid silicon-containing abrasives for certain applications; clean thoroughly after preparation [20] |

| Reference Standards | Instrument calibration verification [20] | Factory-calibrated for specific instrument; store cleanly; test instrument regularly [20] |

| Isopropyl Alcohol | Sample and instrument cleaning [20] | Removes oils and contaminants without residue; preferred over harsh household cleaners [20] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How can I verify if my handheld XRF analyzer is working correctly? Test it using the factory-provided reference standard. Take multiple assays (≥10) of the standard, ensuring the average elemental results fall within the specified Min/Max ranges. If results are outside acceptable ranges, first clean the sample and check the instrument window for damage [20].

Q2: What are the most common mistakes beginners make with handheld XRF analyzers? The top five mistakes are: (1) improper sample preparation (not cleaning or using wrong abrasives), (2) using incorrect calibration for the material type, (3) not replacing protective cartridges regularly, (4) using insufficient measurement time (should be 10-30 seconds), and (5) not following radiation safety protocols [22].

Q3: Why is my lab-on-a-chip device experiencing poor cell viability? This can result from material incompatibility (e.g., PDMS absorbing essential molecules), excessive shear rates from improper flow control, or unsuitable surface chemistry. Ensure your material selection accounts for biocompatibility and consider the effects of fluid manipulation on cell health [15].

Q4: How can I improve the manufacturing scalability of my lab-on-a-chip device? Design for manufacturing from the earliest stages. Choose materials compatible with high-volume processes like injection molding or hot embossing rather than prototyping-only materials like PDMS. Develop pilot production processes before finalizing design [15].

Q5: What are the key considerations for making spectroscopy research "greener"? Focus on: (1) Developing reusable or biodegradable materials (e.g., paper-based devices) to replace single-use plastics, (2) Reducing power consumption through miniaturization, (3) Implementing local manufacturing to reduce transport emissions, and (4) Creating devices that reduce the need for sample transport to central labs [23].

Q6: How often should I replace the protective cartridges on my XRF analyzer? This depends on usage and sample type, but generally after each use session. Aluminum alloys particularly require cartridge changes before analyzing other materials, as aluminum particles can affect future measurements. Always use manufacturer-specified cartridges to maintain accuracy [22].

Q7: What causes inconsistent results in portable spectrometer analysis? Common causes include: (1) Insufficient measurement time (use 10-30 seconds minimum), (2) Sample contamination (oil, moisture, or preparation residues), (3) Dirty optical components, (4) Improper sample presentation (inadequate thickness or contact), and (5) Instrument calibration drift [18] [22] [20].

Reduced Solvent Consumption and Waste Generation in Miniaturized Systems

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Pressure and Poor Peak Shape in Miniaturized LC Methods

Problem: After scaling down a conventional HPLC method to a miniaturized column, the system pressure is too low, and peak shape is poor.

Explanation: This often indicates a mismatch between the instrument's internal volume (dwell volume) and the requirements of the miniaturized column. Excessive volume before the column causes significant delay and band broadening, degrading the separation [24].

Solutions:

- Check Connection Tubing: Use the shortest possible length and the narrowest internal diameter (e.g., 0.005-inch ID) of tubing between the injector and the column.

- Optimize Detector Flow Cell: Ensure the detector flow cell is compatible with low flow rates to prevent extra-column band broadening.

- Method Translation: Re-calculate method parameters, focusing on maintaining linear velocity rather than simply reducing flow rate proportionally. Use method translation software if available.

- Consider System Capabilities: Be aware that standard HPLC instruments may not be optimally suited for columns with an internal diameter smaller than 3.0 mm; 3.0 mm ID columns often represent a practical "sweet-spot" on such systems [24].

Guide 2: Managing Increased Backpressure with High-Efficiency Columns

Problem: Switching to a column with smaller particles or a superficially porous particle (SPP) format causes system pressure to exceed instrumental limits.

Explanation: Columns with smaller particles (<2 µm) and SPPs offer higher efficiency but generate higher backpressure [24].

Solutions:

- Reduce Column Length: A shorter column (e.g., 50 mm or 10 mm) packed with the same high-efficiency particles can maintain resolution while drastically reducing backpressure and run time [24].

- Adjust Flow Rate Temporarily: Slightly lower the flow rate to bring the pressure within the system's limit, but be aware this will increase the analysis time.

- Verify Instrument Limits: Confirm your instrument's maximum pressure rating. Widespread adoption can be limited by the high upfront cost of UHPLC systems capable of very high pressures [24].

- Explore Alternative Phases: Some SPPs or hybrid particles can provide similar efficiency at lower backpressure compared to fully porous sub-2µm particles.

Guide 3: Correcting for Negative Absorbance Peaks in FT-IR Spectroscopy

Problem: FT-IR spectra show strange negative absorbance peaks.

Explanation: In Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) accessories, this is commonly caused by a contaminated crystal. The contaminant absorbs light during the background scan, so when a clean sample is measured, it appears to have "negative" absorption at those wavelengths [9].

Solutions:

- Clean the ATR Crystal: Follow the manufacturer's instructions to properly clean the crystal with an appropriate solvent.

- Acquire a Fresh Background Scan: Always collect a new background spectrum after cleaning the crystal and before measuring a new sample.

- Ensure Proper Contact: For solid samples, ensure the sample is making firm, uniform contact with the crystal surface.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most effective strategies to immediately reduce solvent consumption in my HPLC lab?

The most straightforward strategy is to switch to a column with a narrower internal diameter (ID) operated at a lower flow rate. For example, scaling from a 4.6 mm ID column to a 2.1 mm ID column can reduce mobile phase consumption by nearly 80% for the same analysis time [24]. Additionally, employing high-efficiency, shorter columns or superficially porous particles (SPPs) can cut run times and solvent use by over 50% while maintaining resolution [24].

FAQ 2: I have a standard HPLC system (400-bar limit). Can I still benefit from miniaturization?

Yes, significant sustainability improvements are absolutely achievable. While you may not be able to use the smallest 2.1 mm ID columns effectively, you can successfully use 3.0 mm ID columns. By optimizing system volumes and using 3.0 mm ID columns with modern stationary phases, you can find a "sweet-spot" that greatly reduces solvent and energy consumption without requiring a new instrument [24].

FAQ 3: Besides solvents, how does miniaturization contribute to "greener" spectroscopy?

Miniaturization offers several environmental benefits beyond solvent reduction [11] [4] [24]:

- Reduced Energy Consumption: Shorter analysis times and the ability to turn off instruments sooner directly lower energy usage.

- Minimized Waste Generation: Less solvent consumed means less hazardous waste to be treated and disposed of.

- Lower Sample Volume: Miniaturized techniques require smaller sample volumes, which is crucial for precious or biological samples.

- Decreased Raw Material Use: Smaller columns consume fewer raw materials for their production.

FAQ 4: Are there any experimental scenarios where miniaturization is not recommended?

Yes, miniaturization is generally not suitable for preparative or process-scale chromatography, where the primary goal is to purify large quantities of material. In these cases, high column loadability is essential, and reducing column dimensions would be counterproductive [24]. However, for routine analytical testing, miniaturization remains highly relevant.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Scaling Down an HPLC Method for Solvent Reduction

Objective: To adapt an existing HPLC method to a miniaturized column format, significantly reducing solvent consumption and analysis time while maintaining chromatographic performance.

Materials:

- Original Method: 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm fully porous particle column.

- Miniaturized Column: 50 mm x 3.0 mm, 1.7 µm fully porous particle (or SPP) column with similar stationary phase chemistry.

- HPLC/UHPLC System: Capable of handling higher backpressures and with minimized extra-column volume.

- Mobile Phase: Identical to the original method.

- Samples: Standard and quality control samples.

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Equip the system with narrow-bore tubing (e.g., 0.005" ID) and a low-volume flow cell to minimize extra-column band broadening.

- Method Translation: Use scaling equations or software to translate the original method. The key is to maintain the same linear velocity.

- Flow Rate Calculation: Adjust the flow rate based on the change in column cross-sectional area. Formula:

F2 = F1 * (dc2² / dc1²), whereFis flow rate anddcis column internal diameter. - Example: Scaling from 4.6 mm ID to 3.0 mm ID:

F2 = 1.68 mL/min * (3.0² / 4.6²) ≈ 0.714 mL/min. - Gradient Adjustment: Keep the gradient time proportional to the column void volume to maintain the same gradient steepness. Formula:

tG2 = tG1 * (F1/F2) * (L2/L1), wheretGis gradient time andLis column length.

- Flow Rate Calculation: Adjust the flow rate based on the change in column cross-sectional area. Formula:

- Injection Volume: The injection volume may need scaling down to avoid volume overload. A good starting point is to scale it by the ratio of column volumes.

- System Equilibration: After method translation, run the new method, monitoring system pressure and peak shape. Make minor adjustments to flow rate or gradient as needed for optimal performance.

Quantitative Data on Solvent and Energy Savings

The table below summarizes experimental data demonstrating the environmental benefits of HPLC miniaturization strategies [24].

Table 1: Quantitative Sustainability Gains from HPLC Miniaturization

| Miniaturization Strategy | Specific Change in Column Format | Solvent Consumption Reduction | Energy Reduction | Run Time Decrease |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduced Column ID | 4.6 mm → 2.1 mm ID (same length) | 79.2% | Not specified | Not specified |

| High-Efficiency Short Column | 150x4.6mm, 5µm → 50x3.0mm, 1.7µm | 85.7% | 85.1% | 88.5% |

| Superficially Porous Particles (SPP) | Same dimensions, Fully Porous → SPP | >50% | Not specified | >50% |

| Ultra-Short Column | 100x2.1mm, 3µm → 10x2.1mm, 2µm | 70% (from 5.3 mL to 1.6 mL/inj) | Not specified | 88% (from 13.2 min to 1.6 min) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Miniaturized Chromatography

| Item | Function/Benefit | Considerations for Green Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow-ID Columns (e.g., 3.0 mm, 2.1 mm ID) | Core component for reducing mobile phase consumption at lower flow rates. | Directly reduces solvent waste generation [24]. |

| Superficially Porous Particle (SPP) Columns | Provide high efficiency, leading to faster separations and lower solvent use compared to fully porous particles. | Higher efficiency enables shorter columns and faster runs, saving solvent and energy [24]. |

| Short and Ultra-Short Columns (e.g., 10-50 mm length) | Drastically reduce analysis time and solvent consumption per run while maintaining resolution. | Ideal for high-throughput labs, significantly reducing environmental footprint per sample [24]. |

| Low-Volume Connection Tubing (e.g., 0.005" ID) | Minimizes system dwell volume and band broadening, which is critical for maintaining efficiency in miniaturized setups. | Prevents peak broadening, ensuring that the benefits of a small column are not lost [24]. |

| Compatible Detector Flow Cells | Low-volume flow cells are designed for low flow rates to maintain detection sensitivity and minimize peak dispersion. | Essential for achieving good performance with miniaturized methods without sacrificing data quality. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

Miniaturization Strategy Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate miniaturization strategy in HPLC, based on instrument capabilities and analytical goals.

Diagram 1: A logical workflow for selecting an HPLC miniaturization strategy based on analytical goals and instrument capabilities.

Energy Efficiency and Life Cycle Analysis of Compact Instruments

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How does miniaturization contribute to greener spectroscopy in pharmaceutical research? Miniaturized analytical techniques align with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles by significantly reducing solvent and sample consumption, minimizing waste generation, and lowering the overall environmental footprint of analytical processes. Techniques like capillary electrophoresis and nano-liquid chromatography enhance separation efficiency while using minimal resources, making them ideal for sustainable pharmaceutical testing [11] [25].

Q2: What are the most common performance issues with compact spectrophotometers? Common issues include inconsistent readings or drift, low light intensity errors, blank measurement errors, and unexpected baseline shifts. These often stem from aging light sources, dirty cuvettes or optics, improper calibration, or residual sample contamination [26].

Q3: How can I improve the accuracy and lifespan of my compact spectrometer? Regular maintenance is key: ensure proper calibration using certified standards, keep optical windows and cuvettes clean, allow the instrument sufficient warm-up time, and replace aging lamps promptly. For portable OES spectrometers, also maintain the vacuum pump and ensure proper probe contact during analysis [26] [18].

Q4: My FT-IR spectra are noisy or show strange peaks. What should I check? First, ensure the instrument is free from external vibrations. Then, inspect and clean the ATR crystal, as contaminants can cause negative absorbance peaks. Always collect a fresh background scan after cleaning. Also, verify your data processing settings, as incorrect units (e.g., using absorbance instead of Kubelka-Munk for diffuse reflection) can distort spectra [9].

Q5: Why is Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) important for evaluating compact instruments? LCA provides a systematic method to quantify the total environmental impact of an instrument from raw material extraction to disposal. Using LCA helps researchers and manufacturers make informed decisions to optimize resource efficiency, reduce emissions, and improve the overall sustainability of analytical technologies [27] [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Spectrophotometer Performance Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Spectrophotometer Problems

| Problem Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent readings or drift | Aging lamp; Insufficient warm-up | Replace lamp; Allow 30+ minutes for stabilization [26] |

| Low light intensity error | Dirty/misaligned cuvette; Debris in light path | Clean cuvette; Ensure proper alignment; Inspect optics [26] |

| Blank measurement errors | Incorrect reference; Dirty reference cuvette | Use correct blank solution; Clean reference cuvette thoroughly [26] |

| Unexpected baseline shifts | Residual sample in cell; Requires recalibration | Clean cell completely; Perform baseline correction [26] |

| Noisy FT-IR spectra | Instrument vibration; Dirty ATR crystal | Isolate instrument from vibrations; Clean crystal and take new background [9] |

| Inaccurate analysis (OES) | Contaminated argon; Poor probe contact | Regrind samples to remove coatings; Ensure good probe contact and argon purity [18] |

Guide 2: FT-IR Spectroscopy Quick Fixes

Table 2: Specific FT-IR Issues and Solutions

| FT-IR Issue | Underlying Reason | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy Data | Physical vibrations from pumps or lab activity | Place the instrument on a stable, vibration-free surface [9] |

| Negative Absorbance Peaks | Contaminated ATR crystal | Clean the ATR crystal with appropriate solvent and run a fresh background scan [9] |

| Distorted Baselines in Diffuse Reflection | Data processed in absorbance units | Convert data to Kubelka-Munk units for accurate representation [9] |

| Spectral Differences in Polymer Analysis | Surface chemistry not matching bulk material | Compare surface spectrum with a spectrum from a freshly cut interior [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

Protocol 1: Validating Spectrophotometer Accuracy and Precision

Purpose: To verify the performance of a spectrophotometer after maintenance or when troubleshooting inconsistent results.

Materials:

- Certified reference standards (e.g., neutral density filters, holmium oxide filter for wavelength accuracy)

- Matching, clean cuvettes

- Appropriate blank solution (e.g., solvent)

Methodology:

- Warm-up: Power on the instrument and allow it to stabilize for at least the manufacturer's recommended time (typically 30 minutes) [26].

- Blank Calibration: Using the blank solution in a clean cuvette, perform a blank correction to establish a baseline.

- Accuracy Check: Measure the absorbance of the certified reference standard at its specified wavelength. Compare the measured value to the certified value. The deviation should be within the instrument's specifications.

- Precision (Repeatability) Check: Measure the same homogeneous sample (or standard) at least five times consecutively without re-blanking.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) for the replicate measurements. An RSD exceeding 5% indicates a potential problem with the instrument's precision or sample preparation, and the test should be repeated [18].

Protocol 2: Assessing Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Purpose: To quantitatively assess the sensitivity and detectability of the instrument.

Materials:

- Low-concentration standard or a pure solvent sample

Methodology:

- Baseline Scan: Scan the pure solvent blank over a defined wavelength range (e.g., from 500 to 550 nm).

- Peak Scan: Scan a low-concentration standard that produces a small but known peak.

- Calculation: The signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) is calculated as the height of the analyte peak divided by the peak-to-peak noise of the baseline in a region adjacent to the peak. A declining S/N ratio can indicate a failing lamp or dirty optics.

Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Consumables for Miniaturized Spectroscopy

| Item | Function / Application | Green Chemistry Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Calibrating instrument accuracy and precision; validating methods. | Essential for maintaining data integrity, preventing wasted resources on repeated experiments [26] [18]. |

| Capillary Columns | Stationary phase for separations in capillary electrophoresis (CE) and nano-liquid chromatography (nano-LC). | Core miniaturized technology; drastically reduces solvent consumption compared to standard HPLC [11] [25]. |

| Micro-Sample Vials & Plates | Holding minimal sample volumes for automated, high-throughput analysis. | Reduces plastic waste and sample/solvent volumes required per test [25]. |

| Chiral Selectors | Enabling separation of enantiomers in Electrokinetic Chromatography (EKC) for pharmaceutical analysis. | Provides high-resolution, rapid separations with reduced resource use compared to traditional methods [11]. |

| ATR Crystals (e.g., Diamond) | Enabling direct solid/liquid sample analysis in FT-IR with minimal preparation. | Eliminates or reduces the need for sample preparation solvents (e.g., for KBr pellets) [9]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Used as mobile phases and for sample preparation. | Miniaturized techniques (nano-LC, micro-extraction) reduce consumption by orders of magnitude, aligning with waste reduction principles [11] [25]. |

The Role of Nanomaterials and Nanosensors in Enhancing Green Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions for Green Nanomaterial Synthesis

The table below details key reagents and materials used in the environmentally-friendly synthesis of nanomaterials, which are foundational to developing advanced nanosensors.

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Green Nanomaterial Synthesis and Their Functions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Green Synthesis | Key characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Plant Extracts (e.g., from leaves, fruits) | Acts as a natural source of reducing and stabilizing (capping) agents (e.g., phenols, flavonoids) to convert metal ions into nanoparticles without hazardous chemicals [29]. | Cost-effective, renewable, and simplifies synthesis by combining reduction and stabilization in one step [29]. |

| Microorganisms (Bacteria, Fungi, Algae) | Bio-reduction of metal ions and secretion of biomolecules that cap and stabilize the formed nanoparticles [29]. | Offers potential for large-scale production and synthesis under mild conditions [29]. |

| Semiconductor Nanomaterials (e.g., TiO₂, Cu NPs) | Serves as the active material in photocatalytic degradation of organic water pollutants like methylene blue [29]. | High reactivity and large surface area enable efficient light-driven breakdown of contaminants [29]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Used in sensor platforms and organic solar cells due to exceptional electrical and mechanical properties [30]. | Enhances charge transport and structural integrity in sensing and energy devices [30]. |

| Metal/Metal Oxide Nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag, ZnO) | Function as the sensing element in chemical nanosensors; their unique optical and electrical properties change upon interaction with target analytes [30]. | High surface-to-volume ratio and tunable surface chemistry allow for highly sensitive detection [30]. |

| Polymer Nanosensors (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Used in devices like polymer solar cells and as a matrix for sensor fabrication, offering flexibility and tunable electronic properties [30]. | Enables the development of lightweight, flexible, and potentially low-cost electronic and sensing devices [30]. |

Key Experimental Protocols in Green Nanotechnology

Protocol: Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles Using Plant Extracts

This method provides a sustainable alternative to conventional chemical synthesis [29].

- Preparation of Plant Extract: Wash and dry plant leaves (e.g., Azadirachta indica), then grind them into a fine powder. Boil the powder in deionized water (e.g., 5 g in 100 mL) for 20 minutes and filter the mixture to obtain a clear extract.

- Synthesis Reaction: Mix the plant extract with an aqueous solution of the target metal salt (e.g., 1 mM AgNO₃ for silver nanoparticles) in a defined ratio (e.g., 1:9 v/v) under constant stirring at room temperature.

- Monitoring and Characterization: Observe the color change of the solution (e.g., to yellowish-brown for AgNPs) as initial evidence of nanoparticle formation. Characterize the synthesized nanoparticles using UV-Vis spectroscopy (to confirm surface plasmon resonance), FT-IR spectroscopy (to identify functional groups from the extract responsible for capping and stabilization), and TEM (to determine size and morphology) [29] [31].

- Purification: Centrifuge the nanoparticle solution at high speed (e.g., 15,000 rpm for 15 minutes), discard the supernatant, and re-disperse the pellet in deionized water. Repeat 2-3 times.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Nanosensor Array for Gas/VOC Sensing

This protocol outlines the creation of an artificial olfactory system (e-nose) for applications like breath diagnostics [32].

- Substrate Preparation: Clean a substrate (e.g., silicon wafer or interdigitated electrode array) with solvents and oxygen plasma to ensure a contaminant-free surface.

- Sensor Functionalization: Prepare dispersions of different sensing nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, metal oxide nanowires, functionalized graphene). Deposit each nanomaterial onto specific electrodes of the array using methods like drop-casting, inkjet printing, or chemical vapor deposition to create a diverse sensor array [32].

- Baseline Establishment: Place the functionalized sensor array in a sealed chamber with a continuous flow of pure carrier gas (e.g., synthetic air). Measure and record the baseline electrical resistance (for chemiresistive sensors) of each sensor element.

- Exposure and Data Acquisition: Introduce the target gas or complex mixture (e.g., synthetic breath with specific VOCs) into the chamber. Record the change in the electrical signal (e.g., resistance) from each sensor element over time.

- Data Analysis and Pattern Recognition: Extract features (e.g., maximum response, recovery time) from the signals of all sensors in the array. Use machine learning algorithms (e.g., convolutional neural networks) to analyze the composite response pattern and identify or classify the target analyte [32].

Workflow: Green Analysis Using Miniaturized Nanosensor Systems

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes a nanosensor "green"? A1: A nanosensor is considered "green" when its entire lifecycle aligns with sustainable principles. This includes the use of environmentally benign synthesis routes (e.g., using plant extracts instead of hazardous chemicals), energy-efficient fabrication processes, the sensor's ability to enable miniaturized and on-site analysis (reducing the need for sample transport and large lab equipment), and its potential for detecting environmental pollutants with high sensitivity [33] [29].

Q2: How does miniaturization contribute to greener spectroscopy and analysis? A2: Miniaturization is a cornerstone of green analytical chemistry. It leads to a drastic reduction in the consumption of samples and solvents, minimizes waste generation, and reduces the energy required for operations. Furthermore, miniaturized devices, such as lab-on-a-chip systems integrated with nanosensors, enable portable, on-site, and real-time monitoring, eliminating the environmental footprint associated with transporting samples to a central laboratory [33].

Q3: Why is FT-IR spectroscopy so important for characterizing green-synthesized nanoparticles? A3: FT-IR spectroscopy is crucial because it non-destructively identifies the specific functional groups (e.g., hydroxyl, carbonyl, amine) from the plant extract or microorganism that are responsible for reducing metal ions and capping/stabilizing the nanoparticles. This confirmation is essential for understanding the synthesis mechanism and ensuring the nanoparticles are properly stabilized for their intended application [31].

Q4: What is an artificial olfactory system (e-nose) and what advantage does it offer for gas sensing? A4: An artificial olfactory system, or electronic nose (e-nose), is a device that uses an array of multiple nonspecific nanosensors to mimic the mammalian sense of smell. Instead of one sensor for one analyte, the system generates a unique response pattern ("fingerprint") for a complex gas mixture (like human breath or air). When combined with pattern recognition algorithms (e.g., machine learning), this approach can distinguish between similar compounds, overcoming the selectivity challenges of single sensors and allowing for the diagnosis of diseases or identification of pollutants [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Poor Sensitivity or Selectivity in Nanosensors

- Potential Cause: Inadequate surface functionalization of the nanomaterial, leading to poor interaction with the target analyte.

- Solution: Optimize the functionalization protocol by varying the concentration of the capture probe (e.g., antibody, aptamer) and using appropriate cross-linkers. Employ a sensor array with diverse nanomaterials to enhance selectivity through pattern recognition [32].

Problem: Aggregation of Nanoparticles During Green Synthesis

- Potential Cause: Insufficient capping or stabilizing agents in the plant extract or microbial medium.

- Solution: Increase the concentration of the biological source (e.g., plant extract) relative to the metal salt precursor. Alternatively, post-synthesis stabilization with a gentle, biocompatible capping agent can be performed. Characterize with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to monitor size and stability [29].

Problem: Low Reproducibility in Sensor Fabrication

- Potential Cause: Inconsistent deposition of nanomaterial on the sensor substrate (e.g., drop-casting leading to coffee-ring effect).

- Solution: Shift to more controlled deposition techniques such as inkjet printing or spray coating with a shadow mask. Ensure nanomaterial dispersions are homogeneous and sonicated adequately before deposition [32].

Problem: High Background Noise in Electrical Gas Sensing

- Potential Cause: Interference from environmental factors, particularly humidity and temperature fluctuations.

- Solution: Implement a baseline correction and sensor calibration protocol that accounts for humidity. Use temperature control during measurements. Integrate a reference sensor in the array that is insensitive to the target gas but responds to environmental changes [32].

Mechanism: Functional Principle of a Chemical Nanosensor

The following table consolidates key performance data for various applications of nanomaterials and nanosensors, highlighting their effectiveness in enhancing green analysis.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Nanomaterials and Nanosensors in Green Applications

| Application / Technology | Key Nanomaterial(s) | Performance Metric & Result | Experimental Context / Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells | Zinc Oxide Nanorods, TiO₂ | Power conversion efficiency increased from 1.31% to 2.68% with TiO₂ coating on ZnO nanorods [30]. | Enhanced energy conversion for self-powered sensors [30]. |

| Organic Solar Cells | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Efficiency significantly enhanced from 0.68% to over 14.00% with CNT integration [30]. | Development of efficient, lightweight energy systems [30]. |

| CIGS Solar Cells | ITO (Front Contact) | Efficiency improved by 23.074% (absolute) with ITO front contact [30]. | Ultra-high efficiency energy applications [30]. |

| Polymer Solar Cells | Triple Core-Shell Nanoparticles | Power absorption and short-circuit current enhanced by 136% and 154% due to improved light trapping [30]. | Enhanced performance for portable device power [30]. |

| Wastewater Remediation | Green-Synthesized Copper Nanoparticles | ~70% removal of methylene blue dye from water via photocatalytic degradation [29]. | Green approach for pollutant degradation [29]. |

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Miniaturized Spectroscopy in Drug Development

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Assay Downscaling in Drug Discovery

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on HTS Downscaling

Q1: What are the primary benefits of downscaling HTS assays to 1536-well or higher-density formats? Downscaling HTS assays offers significant advantages, chief among them being a substantial reduction in the consumption of reagents and samples, which aligns with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) [11] [33]. This miniaturization also leads to faster analysis times, reduced costs, and increased throughput, enabling the screening of larger compound libraries more efficiently [33] [4]. Furthermore, it reduces the environmental footprint of drug discovery by minimizing waste generation [4].

Q2: What are the critical validation steps for a newly miniaturized assay? A rigorous validation process is essential for miniaturized assays. For a new assay, a full validation is required, which includes [34]:

- Stability and Process Studies: Determining the stability of all reagents under storage and assay conditions.

- Plate Uniformity Study: A 3-day assessment to evaluate signal variability and separation using the DMSO concentration intended for screening. This study tests the assay at "Max," "Min," and "Mid" signal levels to ensure a robust window for detecting active compounds.

- Replicate-Experiment Study: Conducting replicate experiments to confirm reproducibility.

Q3: What common technical challenges are associated with miniaturized HTS, and how can they be addressed? Several hurdles can appear when transitioning to miniaturized formats [35] [36]:

- Data Analysis: The volume and complexity of multiparametric data, especially from high-content screening (HCS), require a robust informatics framework. Innovative approaches like hierarchical clustering and advanced data analysis algorithms are needed for interpretation [33] [35].

- Liquid Handling: Accurate and precise pipetting of nanoliter volumes is critical. Acoustic dispensing technology, which offers contact-less, accurate fluid transfer, can be a key enabling technology [37].

- Assay Interference: Effects from batch, plate, or well position can lead to false positives/negatives. Proper data normalization techniques (e.g., percent inhibition, z-score) and careful experimental design are crucial to mitigate these effects [36].

Q4: Can crude, unpurified reaction mixtures be used in downscaled screening? Yes, using crude lysates or unpurified reaction mixtures is a validated strategy in ultra-miniaturized screening to accelerate the discovery process. For example, a library of 1536 compounds synthesized on a nanomole scale via acoustic dispensing was successfully screened directly by differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) without purification, leading to the identification of novel protein binders [37]. This approach is applicable for initial hit finding and characterization.

Q5: How does downscaling support greener spectroscopy and analytical practices in drug discovery? Miniaturization is a cornerstone of Green Analytical Chemistry. By drastically reducing the volumes of solvents, reagents, and samples required, miniaturized techniques directly prevent waste generation [33] [4]. Techniques like capillary electrophoresis, nano-liquid chromatography, and lab-on-a-chip devices not only use less material but also enhance energy efficiency and enable the development of portable, self-powered devices for on-site analysis, further contributing to sustainability [11] [33].

Troubleshooting Guide for Miniaturized HTS Assays

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No signal or very low signal | Assay buffer too cold, causing low enzyme activity [38]. | Equilibrate all reagents to the specified assay temperature before use [38]. |

| Reagents omitted or protocol step skipped [38]. | Re-read the data sheet and follow instructions meticulously [38]. | |

| Reagents expired or incorrectly stored [38]. | Check the expiration date and storage conditions for all reagents [38]. | |

| Samples are too dilute [38]. | Concentrate the sample or prepare a new one with a higher concentration of cells or tissue [38]. | |

| Signals are too high (saturation) | Standards or samples are too concentrated [38]. | Dilute samples and ensure standard dilutions are prepared correctly according to the data sheet [38]. |

| Working reagent was prepared incorrectly [38]. | Remake the working reagent, carefully following the instructions [38]. | |

| High signal variability between replicates | Air bubbles in wells [38]. | Pipette carefully to avoid bubbles; tap the plate to dislodge any that form [38]. |

| Inconsistent pipetting or unmixed wells [38]. | Use calibrated equipment, pipette consistently, and tap the plate to ensure uniform mixing [38]. | |

| Precipitate or turbidity in wells [38]. | Inspect wells; dilute, deproteinate, or treat samples to eliminate precipitation [38]. | |

| Poor assay performance (e.g., low Z'-factor) | High background noise or signal drift [36]. | Conduct a Plate Uniformity study to identify and correct for edge effects, reagent instability, or timing issues [34]. |

| DMSO concentration incompatible with the assay [34]. | Perform a DMSO compatibility test early in validation (typically 0-1% for cell-based assays) and use the validated concentration in all screens [34]. | |

| Failed nano-scale synthesis | Incompatible solvent or reaction conditions [37]. | Test different solvents suitable for acoustic dispensing (e.g., DMSO, ethylene glycol, 2-methoxyethanol) and optimize reaction time [37]. |

Quantitative Data for HTS Assay Scales

The following table summarizes key parameters and resource consumption across different HTS assay scales, illustrating the efficiency gains from miniaturization.

Table 1: Comparison of Typical HTS Assay Scales

| Parameter | 96-Well Format | 384-Well Format | 1536-Well Format | Nano-Scale (Acoustic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Well Volume | 100-200 µL | 20-50 µL | 5-10 µL | 3.1 µL (total reaction) [37] |

| Sample/Reagent Consumption | High | Moderate | Low | Very Low (nanomoles) [37] |

| Throughput (compounds) | Low | Medium | High | Very High (e.g., 1536 reactions/plate) [37] |

| Key Enabling Technologies | Standard pipettes, plate readers | Multichannel pipettes, automated liquid handlers | Non-contact dispensers (acoustic), specialized optics [35] | Acoustic dispensing (e.g., Echo 555) [37] |

| Common Applications | Early HTS, functional assays | Primary HTS, dose-response | Ultra-HTS, high-content screening [35] | On-the-fly synthesis and screening [37] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Downscaling Workflows

Protocol 1: Automated Nano-Scale Synthesis and Screening

This protocol enables the synthesis and screening of a 1536-compound library on a nanomole scale for initial hit identification [37].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Source Plate: Contains building block stock solutions (e.g., 71 isocyanides, 53 aldehydes, 38 cyclic amidines) in appropriate solvents [37].

- Destination Plate: 1536-well microplate [37].

- Instrument: Acoustic dispenser (e.g., Echo 555) [37].

- Solvents: Ethylene glycol or 2-methoxyethanol [37].

- Detection System: Mass Spectrometer, Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) instrument [37].

Procedure:

- Library Design: Use a script to randomly combine building blocks into the wells of a 1536-well destination plate to maximize chemical diversity [37].

- Acoustic Dispensing: Use the acoustic dispenser to transfer 2.5 nL droplets of each building block from the source plate to the destination plate. The total reaction volume is 3.1 µL per well, containing ~500 nanomoles of total reagents [37].

- Reaction Incubation: Seal the plate and incubate for 24 hours at room temperature [37].

- Quality Control: After incubation, dilute each well with 100 µL of ethylene glycol. Analyze the reaction mixtures by direct-injection mass spectrometry to categorize reaction success [37].

- Screening: Screen the crude, unpurified reaction mixtures directly against the biological target using a biophysical assay such as Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) [37].

Protocol 2: Miniaturized Production of Recombinant AAV (rAAV) Vectors

This streamlined protocol for producing gene therapy vectors in a 6-well format demonstrates downscaling for biologics and complex molecules [39].

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Cell Line: Adherent HEK293T cells (passage number <15) [39].

- Plasmids: pTransgene, pRep/Cap, pHelper in a 1:1:1 molar ratio [39].

- Transfection Reagent: Polyethylenimine (PEI) [39].

- Culture Vessel: 6-well cell culture plate [39].

- Media: DMEM + 10% Fetal Calf Serum (FCS) [39].

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Seed HEK293T cells at a density of 0.5 x 10^6 cells per well in a 6-well plate. Incubate for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO₂ until cells reach 60-70% confluence [39].

- Transfection Mix Preparation:

- Transfection: Add the transfection mix dropwise to each well. Gently shake the plate and return it to the incubator [39].

- Harvest: 72 hours post-transfection, aspirate the medium. Wash and detach the cells by adding PBS and pipetting. Transfer the cell suspension to a microcentrifuge tube [39].

- Lysis and Analysis: Pellet the cells by centrifugation (800 x g for 10 min). Discard the supernatant and resuspend the cell pellet in 100 µL of PBS. This crude lysate contains the rAAV vectors and can be used directly for downstream transduction assays or further purified [39].

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

HTS Downscaling Workflow

On-the-Fly Synthesis and Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Miniaturized HTS

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Acoustic Dispenser (e.g., Echo 555) | Enables contact-less, highly precise transfer of nanoliter volumes of reagents and compound libraries for miniaturized assays and synthesis [37]. |

| DMSO-Tolerant Assay Reagents | Critical for screening compounds stored in DMSO; reagents must maintain stability and activity at the final DMSO concentration used (typically 0-1% for cell-based assays) [34]. |

| 1536-Well Microplates | The standard consumable for ultra-high-throughput screening, designed for low-volume reactions and compatible with automated imaging and detection systems [35] [37]. |

| Stable Cell Lines (e.g., HEK293T) | Used in cell-based HTS and for producing biological tools (e.g., viral vectors); consistent passage number and viability are crucial for reproducible results [39]. |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI) | A transfection reagent used to deliver plasmid DNA into cells for protein or virus production in miniaturized formats (e.g., rAAV production) [39]. |

| Specialized Solvents (e.g., Ethylene Glycol) | Used in nano-scale synthesis for acoustic dispensing due to their suitable physical properties and compatibility with biochemical reactions [37]. |

| High-Sensitivity Detection Kits (DSF, MST) | Biophysical assay kits for protein-binding studies; essential for screening unpurified nano-scale reactions with low compound mass [37]. |

Miniaturized NIR and Raman Spectroscopy for Raw Material and Product Analysis

The adoption of miniaturized NIR and Raman spectrometers represents a significant stride toward sustainable analytical practices. These portable tools align with the principles of Green Analytical Chemistry and Circular Analytical Chemistry by drastically reducing the consumption of energy and solvents, minimizing waste generation, and enabling analyses at the point of need [12]. This technical support center is designed to help you overcome common experimental challenges, ensuring you can leverage these technologies for accurate, efficient, and greener analysis.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Spectral Quality and Artifacts

Q1: My Raman spectrum has a broad, sloping background that obscures the peaks. What is this and how can I correct it?

- Problem: This is typically fluorescence interference, a common sample-induced artifact where the fluorescence signal can be orders of magnitude more intense than the Raman signal [40] [41].

- Solutions:

- Experimental: Use a spectrometer with a longer wavelength laser source (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm) to reduce the energy that excites electronic transitions [40] [41] [42].

- Data Pre-treatment: Apply mathematical corrections to the spectrum. Derivatives (first or second) are highly effective at removing broad, additive backgrounds like fluorescence [41]. Other methods include baseline correction algorithms [43].

Q2: The baseline of my NIR spectrum from a powder sample is shifting. What causes this?

- Problem: This is caused by light scattering effects due to uncontrollable physical variations in your sample, such as changes in particle size distribution, density, or surface roughness [41].

- Solutions:

- Data Pre-treatment: Apply scattering correction algorithms.

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) are standard for correcting multiplicative and additive effects [41].

- Extended Multiplicative Signal Correction (EMSC) is a more advanced, model-based method that can separate physical light-scattering effects from chemical absorbance, providing superior results for complex samples [41].

- Data Pre-treatment: Apply scattering correction algorithms.

Q3: I see sharp, random spikes in my Raman spectrum. What are they?

- Problem: These are cosmic rays (or cosmic spikes), caused by high-energy particles striking the detector [43].

- Solution: Most modern spectrometer software includes an algorithm for cosmic spike removal. This should be one of the first steps in your data analysis pipeline [43].

Measurement and Calibration

Q4: My Raman measurements on the same sample seem to drift over time. Why?

- Problem: Instabilities in the laser wavelength or intensity can cause spectral shifts and intensity fluctuations [40]. Without proper calibration, these instrumental drifts can be mistaken for sample-related changes [43].

- Solutions:

- Wavelength Calibration: Regularly measure a wavenumber standard (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol) with known peaks to construct a stable and accurate wavenumber axis [43].

- Intensity Calibration: Perform a white light measurement to correct for the spectral transfer function of the optical system and the detector's quantum efficiency, generating setup-independent Raman spectra [43].

Q5: How can I ensure my method works on a different miniaturized spectrometer?

- Problem: Poor method transferability due to instrumental variations.

- Solution: Raman spectroscopy benefits from high selectivity with distinct spectral peaks. Methods created on one instrument can often be transferred to another by simply transferring the reference library files, especially if the instruments are of the same model [42]. For NIR, which has broader, less distinct peaks, method transfer may require more expert intervention and additional reference spectra to account for inter-instrument variability [42].

Data Analysis and Modeling

Q6: What is the most critical mistake to avoid in data analysis?

- Problem: Information leakage during model evaluation, where data from the same biological replicate or patient are split between training and test sets. This leads to a significant overestimation of model performance [43].

- Solution: Ensure complete independence of your data subsets. All spectra from a single independent sample (e.g., a patient, a batch) must be placed entirely in either the training, validation, or test set. Use a "replicate-out" or "patient-out" cross-validation strategy [43].

Q7: What is the correct order for spectral pre-processing steps?

- Incorrect Order: Performing spectral normalization before background correction.

- Correct Order: The fluorescence background intensity is encoded in the normalization constant, which will bias your model. Always perform baseline correction before normalization [43].

Table 1: Summary of Common Artifacts and Mitigation Strategies

| Artifact/Issue | Primary Cause | Recommended Correction Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | Sample impurities/electronic transitions | Longer wavelength laser (785/1064 nm), derivative spectra, baseline correction [40] [41] |

| Light Scattering | Particle size/density variations (NIR) | SNV, MSC, EMSC [41] |

| Cosmic Rays | High-energy particle detector strike | Automated cosmic spike removal software [43] |

| Spectral Drift | Laser instability, environmental changes | Regular wavenumber & intensity calibration [43] |

Experimental Protocols for Greener Analysis

Protocol 1: Non-Destructive Raw Material Authentication through Packaging

This protocol enables rapid, green verification of incoming raw materials without breaking packaging seals, reducing contamination risk, solvent use, and analysis time [42].

- Sample Presentation: Place the handheld Raman spectrometer's laser aperture against the transparent packaging (e.g., glass vial or polyethylene bag liner) containing the raw material. Use a vial-holder or nose-cone attachment if available to ensure correct and consistent focal distance [42].

- Method Selection: Select the appropriate method from the instrument's library, often by scanning a barcode on the container [42].

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the measurement. For modern handheld systems, use the "auto" mode, where the instrument automatically optimizes laser power, exposure time, and the number of accumulations to achieve a target signal-to-noise ratio in the shortest time possible [42].

- Identity Verification: The instrument software compares the unknown spectrum to the reference library. Advanced systems use a probability-based approach (e.g., calculating a p-value) to determine if differences are statistically significant given the measurement uncertainty, providing a "pass/fail" result [42].

Protocol 2: Building a Robust Model for Soil Contaminant Monitoring with Vis-NIR

This protocol outlines a green alternative to traditional, waste-intensive methods for monitoring Potentially Toxic Trace Elements (PTEs) in soil [13].

- Sample Collection and Spectral Acquisition: Collect a diverse set of soil/sediment samples representing different types and PTE concentrations. Acquire Vis-NIR spectra directly from prepared soil samples.

- Data Pre-processing: Apply necessary pre-treatments to minimize physical scattering and enhance chemical signals. Common steps include Savitzky-Golay smoothing and derivatives [13].

- Multivariate Modeling: Use machine learning techniques like Random Forests or Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to correlate spectral features with PTE concentrations. For large, independent datasets, more complex models can be explored [44] [43] [13].

- Model Validation: Critically evaluate the model using an independent test set or a strict cross-validation method where all spectra from a single sampling site are kept together to prevent over-optimistic performance estimates [43] [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Miniaturized Spectroscopy

| Item | Function / Use Case |

|---|---|