Mitigating Spectral Artifacts in Handheld Raman Data: A Practical Guide for Robust Biomedical Analysis

Handheld Raman spectroscopy is revolutionizing pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis with its portability and non-destructive capabilities.

Mitigating Spectral Artifacts in Handheld Raman Data: A Practical Guide for Robust Biomedical Analysis

Abstract

Handheld Raman spectroscopy is revolutionizing pharmaceutical and biomedical analysis with its portability and non-destructive capabilities. However, its full potential is often limited by spectral artifacts arising from instrumental noise, fluorescence, and environmental variables. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to identify, troubleshoot, and mitigate these artifacts. Covering foundational principles, advanced preprocessing methodologies, AI-powered optimization techniques, and rigorous validation protocols, we deliver actionable strategies to enhance data quality, ensure regulatory compliance, and unlock the transformative potential of handheld Raman in drug discovery and clinical applications.

Understanding Spectral Artifacts: Sources and Impact on Handheld Raman Data Integrity

The Pervasive Challenge of Artifacts in Portable Spectroscopy

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Correcting Common Artifacts

This guide helps you identify common artifacts in portable Raman spectroscopy, understand their causes, and apply effective corrections.

Cosmic Rays (Cosmic Spikes)

- Description: Sharp, intense, narrow spikes that appear randomly in spectra.

- Causes: High-energy cosmic particles or their secondary particles striking the detector [1].

- Correction:

- Use built-in instrument software for cosmic ray removal.

- For persistent spikes, acquire multiple spectra and apply statistical filters (e.g., median filtering) to identify and remove outliers.

Fluorescence Background

- Description: A broad, sloping baseline that can obscure Raman peaks, often 2-3 orders of magnitude more intense than Raman signals [1].

- Causes: Sample impurities or the sample itself emitting fluorescence [2] [3].

- Correction:

Spectral Calibration Drift

- Description: Systematic shifts in the wavenumber axis, causing peaks to appear at incorrect positions.

- Causes: Changes in ambient temperature or instrumental instability [1].

- Correction:

Signal Instability and Noise

- Description: Unwanted random variations or baseline fluctuations.

- Causes:

- Correction:

- Ensure laser source is stable and properly filtered [2].

- Check and clean optical components; realign if necessary.

- For noise reduction, increase integration time or accumulate more scans, applying smoothing algorithms carefully to avoid losing spectral information.

Sample-Induced Artifacts

- Description: Sample heating, decomposition, or unexpected spectral features.

- Causes:

- Correction:

- Reduce laser power to avoid sample damage.

- Ensure proper sample preparation and cleaning.

- For heterogeneous samples, acquire multiple spectra from different positions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the order of data processing steps so important in Raman analysis? The sequence is critical to prevent introducing biases. Always perform baseline correction before spectral normalization. If normalization is done first, the fluorescence background intensity becomes encoded in the normalization constant, potentially biasing all subsequent models [1].

Q2: My portable Raman instrument shows different peak intensities on different days. How can I make my data comparable? This is typically an intensity calibration issue. Perform intensity calibration to correct for the spectral transfer function of optical components and the quantum efficiency of the detector. This generates setup-independent Raman spectra, making data from different days comparable [1].

Q3: What is the most common mistake when building calibration models for quantitative analysis? A common mistake is having insufficient independent samples for model training and testing. For reliable models, measure at least 3-5 independent biological replicates in cell studies, and approximately 20-100 patients for diagnostic studies [1].

Q4: When should I use SNV normalization versus baseline correction? Standard Normal Variate (SNV) processing standardizes your data by subtracting the range-average and dividing by the range-standard deviation, which helps scale spectra together [4]. However, SNV should generally be applied after baseline correction to avoid amplifying background artifacts [1].

Q5: How can I avoid over-optimizing my preprocessing parameters? Instead of using model performance to optimize preprocessing parameters, use spectral markers as the merit for optimization. This prevents overfitting to your specific dataset and improves model generalizability to new data [1].

Table 1: Common Artifacts in Portable Raman Spectroscopy

| Artifact Type | Primary Cause | Detection Method | Recommended Correction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmic Ray Spikes | High-energy particles [1] | Visual inspection of sharp, narrow spikes | Multiple acquisitions with statistical filtering [1] |

| Fluorescence Background | Sample impurities or matrix [2] [3] | Broad, sloping baseline obscuring peaks | Longer wavelength lasers; computational baseline correction [2] [1] [3] |

| Wavenumber Drift | Instrumental or temperature instability [1] | Peak shifts in standard reference measurements | Regular calibration with wavenumber standards [1] |

| Signal Instability | Laser fluctuations or misalignment [2] | Baseline fluctuations and noise | Laser filtering; optical realignment; signal averaging |

| Etaloning | Thin-film interference in CCD detectors | Periodic modulation of baseline | Specialized optical filters or computational correction |

Experimental Protocols for Artifact Mitigation

Protocol 1: Routine Instrument Calibration

- Daily Check: Perform quick measurement of a wavenumber standard.

- Weekly Calibration: Conduct full white light reference measurement.

- After Any Movement: Recalibrate portable instrument after transportation.

- Documentation: Record all calibration results and environmental conditions.

Protocol 2: Sample Measurement Best Practices

- Laser Power Optimization: Start with low power, gradually increase while monitoring for sample damage.

- Multiple Acquisitions: Collect 3-5 spectra from different sample spots.

- Background Reference: Always measure appropriate blank/reference sample.

- Parameter Consistency: Use the same measurement settings for all comparable samples [5].

Protocol 3: Building Robust Calibration Models

- Design of Experiments (DOE): Use DOE to define a design space with more variation than expected in commercial use [5].

- Analyte Spiking: Extend concentration ranges and break correlations between analytes [5].

- Independent Validation: Ensure training, validation, and test datasets contain independent biological replicates [1].

- Model Selection: Choose model complexity based on available independent measurements [1].

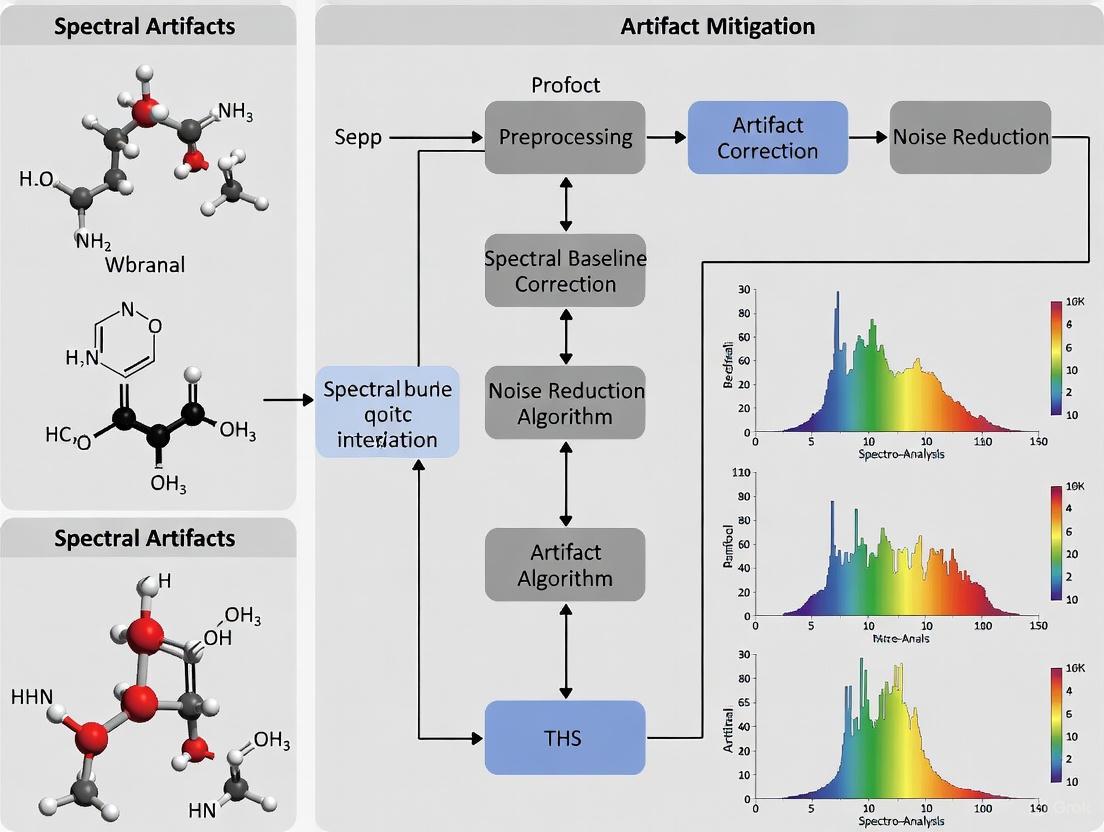

Diagram: Raman Data Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 4-Acetamidophenol | Wavenumber calibration standard | Provides multiple peaks across wavenumber regions; use for constructing wavenumber axis [1] |

| Polystyrene | Intensity and wavelength reference | Well-characterized spectrum for routine instrument validation |

| SERS Substrates | Signal enhancement | Gold/silver nanoparticles for trace detection; citrate used in some substrates [4] |

| Reference Analytes | Model calibration | Pure compounds (e.g., glucose, lactate) for building predictive models [5] |

| Design of Experiments Software | Statistical experimental design | Defines design space with intentional parameter variations [5] |

| MVDA Software | Multivariate Data Analysis | Finds correlations between spectral data and reference analyses [5] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common Raman Artifacts

This guide addresses the most frequent artifact sources in Raman spectroscopy, providing researchers with clear methodologies for identification and resolution.

FAQ: How can I tell if my spectrum has a fluorescence background, and what can I do about it?

Fluorescence interference is a common issue that can obscure the weaker Raman signal, manifesting as a broad, elevated baseline underneath the sharper Raman peaks [6].

- Identification: Look for a steeply sloping or curved baseline that overwhelms the Raman bands. In severe cases, the Raman peaks may be completely undetectable [7].

- Solutions:

- Use NIR Excitation Wavelengths: Switching the laser excitation from visible wavelengths (e.g., 532 nm) to near-infrared (NIR) wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm) is one of the most effective methods. Since fluorescence requires a certain energy threshold (wavelength) to be excited, using a 1064 nm laser often avoids electronic excitation entirely, drastically reducing fluorescence [7]. For example, a Raman spectrum of PEEK plastic that was featureless at 532 nm excitation showed clear, assignable peaks when measured at 1064 nm [7].

- Employ Photobleaching: Pre-expose the sample to the laser for an extended period before collecting the analytical spectrum. This process can "bleach" or degrade the fluorescent impurities over time, reducing the fluorescence background [6].

- Apply Background Subtraction Algorithms: Software solutions can be used post-measurement to subtract the fluorescent background. Algorithms, such as those using a Savitzky-Golay filter, can model and remove the broad baseline curvature, leaving a flat Raman spectrum [6].

Noise degrades the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), making it difficult to distinguish weak Raman bands. The primary sources are instrumental and include dark current and readout noise [8] [9].

- Identification: Noise appears as high-frequency, random variations or "fuzziness" on the spectral baseline, distinct from the broader fluorescence background.

- Solutions:

- Cool Your Detector: Deeply cooling the CCD detector (e.g., to -60°C) significantly reduces the dark current shot noise, which is a major noise source for long acquisition times [8].

- Optimize Acquisition Time and Laser Power: Increasing the signal strength by using longer acquisition times or higher laser power (within the sample's damage threshold) improves the SNR. However, this must be balanced against the risk of sample degradation or increased fluorescence [8].

- Use Denoising Algorithms: Computational methods can be applied during data processing to smooth the spectrum. These range from simple moving window average smoothing to advanced deep learning algorithms that can effectively separate noise from the true Raman signal [10].

FAQ: My Raman peaks look distorted or have unexpected spikes. What could be the cause?

Cosmic spikes and calibration errors are common culprits for distorted or anomalous peaks [3] [1].

- Identification:

- Solutions:

- Remove Cosmic Spikes: Most modern Raman software includes automated algorithms for cosmic spike removal. These identify and filter out these sharp, anomalous spikes from the data [1].

- Perform Regular Wavelength/Wavenumber Calibration: Frequently measure a standard reference material (e.g., 4-acetamidophenol or a silicon wafer) with known and stable peak positions. Use this measurement to correct and align your spectrometer's wavenumber axis, ensuring accurate and reproducible peak assignments [1].

Experimental Protocol: Mitigating Fluorescence in Microplastics via Photo-Fenton Treatment

The following detailed protocol is adapted from a study focused on removing fluorescent interference from pigmented microplastics [11].

- Objective: To oxidatively degrade fluorescent pigment additives in environmental microplastic samples, thereby enabling clear Raman spectroscopic analysis.

- Materials:

- Microplastic samples

- Fenton's reagent catalysts: FeSO₄·7H₂O (Fe²⁺), FeCl₃ (Fe³⁺), Fe₃O₄, or K₂FeO₇

- Hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂, 30% wt/wt)

- Ultrapure water

- Laboratory glassware

- Procedure:

- Preparation: Cut plastic samples into manageable pieces (e.g., 1 cm² films).

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a sunlight-Fenton reaction system. For example, use a Fe²⁺ catalyst at a concentration of 1 × 10⁻⁶ M and H₂O₂ at a concentration of 4 M.

- Treatment: Submerge the samples in the Fenton's reagent and expose them to sunlight or UV light for a defined period (e.g., 14 hours). The light catalyzes the decomposition of H₂O₂, generating highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (·OH).

- Degradation Mechanism: These hydroxyl radicals non-selectively and oxidatively degrade the organic pigment molecules responsible for the fluorescence signal.

- Analysis: After treatment, rinse the samples with ultrapure water and analyze them using Raman spectroscopy.

- Expected Outcome: The study reported that this treatment increased the proportion of microplastics with a high Raman spectrum matching-degree (RSMD ≥ 70%) from 13.33% to 87.62%, successfully removing the fluorescent interference without advanced detectors or spectral processing [11].

The table below consolidates key quantitative data from research to guide experimental design.

| Artifact Source | Quantitative Impact / Threshold | Recommended Mitigation Strategy | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | Baseline 2-3 orders of magnitude more intense than Raman bands [1]. | Use 1064 nm excitation; Photobleaching; Background subtraction algorithms [6] [7]. | [6] [1] [7] |

| Detector Dark Noise | Significant increase with long acquisition times and high operating temperatures [8]. | Use deeply cooled CCD detectors (e.g., -60°C) [8]. | [8] |

| Laser Power Density | Sample-dependent threshold beyond which structural/chemical changes occur [3]. | Carefully adjust incident laser power to stay below sample damage threshold [8]. | [8] [3] |

| SERS Enhancement | Signal enhancement of 10¹⁰ to 10¹⁴ reported, enabling trace analysis [12]. | Use gold or silver nanoparticle substrates to amplify Raman signal [12]. | [12] |

| Confocal Pinhole | Reducing diameter exponentially increases Raman band contrast against fluorescence [6]. | Close the confocal pinhole to limit collection volume to the focal plane [6]. | [6] |

Visualizing the Raman Artifact Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing the common artifacts discussed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for Raman Analysis

This table lists essential materials used in the featured experiments and general Raman spectroscopy for effective artifact mitigation.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Raman Spectroscopy | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fenton's Reagent (Fe²⁺/Fe³⁺ & H₂O₂) | Oxidatively degrades fluorescent pigment molecules in samples [11]. | Sample pre-treatment for fluorescent microplastics and other pigmented materials [11]. |

| Gold & Silver Nanoparticles | Provides immense Raman signal enhancement (SERS) via plasmonic effects [12]. | Trace detection of pollutants, pharmaceuticals, and biological molecules [12]. |

| Wavenumber Standard (e.g., 4-Acetamidophenol, Silicon Wafer) | Calibrates and validates the wavenumber axis of the spectrometer for accurate peak assignment [1]. | Routine instrument calibration and quality control [1]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Objective Lenses | Corrects for optical aberrations and maximizes light collection at NIR wavelengths [7]. | Essential for measurements using 1064 nm lasers to reduce fluorescence [7]. |

| InGaAs Detector | High-sensitivity detector optimized for the NIR spectral range [7]. | Used in FT-Raman and NIR dispersive systems (e.g., with 1064 nm lasers) [7]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common artifacts in Raman spectroscopy that can affect my machine learning model?

Artifacts in Raman spectroscopy are typically grouped into three categories, each with the potential to significantly skew your quantitative analysis and machine learning outcomes [3] [2]:

- Instrumental Effects: Caused by the equipment itself, including:

- Laser Instability: Fluctuations in laser intensity or wavelength cause noise and baseline shifts [3] [2].

- Non-Lasing Emission Lines: Lasers (e.g., Nd:YAG) can emit unintended wavelengths, introducing spurious peaks if not properly filtered [3] [2].

- Detector Noise: Electronic noise from components like CCDs introduces unwanted signals [3].

- Sample-Induced Effects: Arising from the sample's properties:

- Sampling-Related Effects: Resulting from the measurement process:

- Motion Artifacts: Sample movement during measurement can distort spectra with significant noise and baseline shifts [3].

Q2: My ML model performs well on training data but poorly on new data. Could spectral artifacts be the cause?

Yes, this is a classic sign of poor model generalizability, often rooted in data quality issues. Artifacts can create misleading patterns that your model learns during training. When presented with new, real-world data that lacks these specific artifactual patterns, performance drops [13] [14]. This is often due to:

- Non-Representative Training Data: If your training data contains artifacts that are not present (or are different) in the test data or real-world deployment environment, the model will fail to generalize [13].

- Overfitting to Noise: Models can learn to "fit the noise" introduced by artifacts rather than the underlying molecular signatures of interest [14].

Q3: Is it better to have missing data or noisy data in my dataset for ML training?

Research indicates that noisy data is generally more detrimental to machine learning models than missing data [15].

- Noisy Data: Causes rapid performance degradation and increases training instability, as it actively misleads the learning algorithm. This is especially critical in sequential decision-making tasks [15].

- Missing Data: While harmful, its impact is less severe. Models can often learn to handle missingness through techniques like masking [15].

The relationship between model performance (S) and the corruption level (p) often follows a diminishing returns curve: S = a(1 - e^{-b(1-p)}) [15].

Q4: How can I make Raman data from different instruments compatible for a single ML analysis?

The key is spectral harmonization. This process ensures that different Raman systems produce equivalent results, enabling interoperability [16]. A proven method involves:

- Intensity Correction: Applying algorithms to harmonize Raman intensities, achieving a coincidence of >90% across different instruments and laser wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm and 532 nm) [16].

- Chemometric Validation: Using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to study and confirm the reproducibility of the harmonized spectra [16]. This moves beyond simple pass/fail validation and allows for harmonized quantification.

Troubleshooting Guide: Artifacts and Mitigation Strategies

| Problem Area | Specific Symptom | Potential Artifact Cause | Recommended Correction Procedure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Source | Unusual peaks, high background | Non-lasing emission lines from laser source | Apply appropriate optical filters (notch, bandpass, holographic) [3] [2]. |

| Laser Source | Baseline drift, noisy signal | Instabilities in laser intensity or wavelength | Ensure laser power and cooling systems are stable; use a high-quality, stable laser source [3]. |

| Sample | High, sloping background obscuring peaks | Sample fluorescence | Use a longer wavelength laser (e.g., 785 nm, 1064 nm); apply computational background subtraction techniques [3] [2]. |

| Data Collection | Spikes or sharp, non-reproducible peaks | Cosmic ray strikes on the detector | Utilize cosmic ray removal algorithms available in most modern spectrometer software [2]. |

| Data Quality for ML | Model performs poorly on real-world data | Training/test data not harmonized or contain different artifacts | Implement spectral harmonization protocols [16] and ensure consistent preprocessing across all data. |

| Data Quality for ML | Model is biased or inaccurate | Underlying training data is biased or of poor quality | Apply a data quality framework like METRIC to assess dataset composition and identify biases [17]. |

Quantitative Impact of Data Corruption on ML

The table below summarizes findings from a study on how data corruption impacts model performance, guiding resource allocation for data cleaning [15].

| Corruption Type | Impact on Model Performance | Training Stability | Effectiveness of Increasing Data Volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing Data | Performance degrades gradually. Less detrimental than noise [15]. | Lower impact on stability [15]. | Mitigates but does not fully eliminate degradation [15]. |

| Noisy Data | Rapid performance degradation. More harmful than missing data [15]. | Causes significant instability, especially in sequential tasks [15]. | Limited recovery; marginal utility diminishes with high noise [15]. |

| Empirical Rule | ~30% of data is critical for performance; ~70% can be lost with minimal impact [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Spectral Harmonization for Reliable ML

Objective: To achieve interoperability between different Raman instruments, enabling the creation of a unified, high-quality dataset for machine learning analysis [16].

Materials:

- Two or more Raman spectrometers (e.g., with 785 nm and 532 nm laser excitations).

- Reference materials (e.g., potassium‑sodium niobate, polystyrene).

- Samples of interest (e.g., security markers from documents).

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Collect Raman spectra from the same set of reference materials and samples across all instruments.

- Intensity Harmonization: Apply a harmonization algorithm to correct for intensity disparities between the different systems. The goal is a >90% coincidence in intensity [16].

- Validation via Chemometrics: Perform a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) on the harmonized dataset.

- Expected Outcome: Spectra from the same material, regardless of the instrument used, should cluster tightly together in the PCA score plot. This confirms high reproducibility [16].

- Model Training & Testing: Use the harmonized dataset to train and validate your machine learning model.

METRIC Framework for Assessing Data Quality in Medical ML

For researchers in drug development, the METRIC-framework provides a structured way to assess training data quality, which is crucial for regulatory approval of ML-based medical devices [17]. It comprises 15 awareness dimensions to reduce biases and increase robustness. Key dimensions include:

- Completeness: The degree to which expected data is present.

- Accuracy: The correctness of the data values.

- Consistency: The absence of contradictions in the data.

- Representativeness: How well the data reflects the target population.

- Fairness: The absence of biases that could lead to unfair outcomes.

Systematically evaluating a dataset along these dimensions helps lay the foundation for trustworthy AI in medicine [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., Polystyrene) | Used for instrument calibration and spectral harmonization protocols to ensure data comparability across different labs [16]. |

| Notch & Bandpass Filters | Critical optical components for removing elastic Rayleigh scattering and non-lasing laser emission lines, ensuring a clean Raman spectrum [3] [2] [18]. |

| Stable Laser Sources (785 nm, 1064 nm) | Longer wavelengths help minimize fluorescence artifacts from biological samples, improving signal-to-noise ratio [3] [2]. |

| Data Quality Assessment Framework (e.g., METRIC) | A structured checklist to evaluate training datasets for biases and quality issues, which is essential for building robust and fair ML models [17]. |

Workflow Diagram: Mitigating Artifacts for Robust ML

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My Raman spectrum has a large, sloping background that obscures the peaks. What is this, and how can I remove it?

This is likely fluorescence background, a common issue where sample fluorescence creates a slowly varying baseline that can swamp the weaker Raman signal [19] [2]. Correction is typically a two-step process: First, estimate the baseline, then subtract it from the raw spectrum [20].

- Recommended Workflow:

- Asymmetric Least Squares (ALS): This is a powerful method that models the baseline by assigning asymmetric weights to points, assuming the Raman peaks are positive deviations [21] [20]. It works well for complex baselines.

- Iterative Polynomial Fitting (e.g., I-ModPoly): This method fits a polynomial to the spectrum iteratively, excluding peak regions to refine the baseline estimate. It is effective but may require careful selection of the polynomial degree [20].

- SNIP Clipping: The Statistics-sensitive Non-linear Iterative Peak-clipping (SNIP) algorithm is another robust, parameter-driven method for estimating the background [19] [20].

Q2: My data is very noisy. What are the best methods for denoising without distorting the Raman peaks?

Denoising aims to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) while preserving the integrity of the Raman peaks, which can be compromised by simple smoothing [22].

- Recommended Workflow:

- Savitzky-Golay (SG) Filtering: This is a common and effective method. It performs a local polynomial regression to smooth the data. The key is to choose an appropriate window size; too small a window leaves excess noise, while too large a window broadens and distorts peaks [20].

- Wavelet Transform: This method decomposes the signal into different frequency components, allowing for targeted removal of high-frequency noise. It can achieve excellent results but often requires manual selection of decomposition levels [23].

- Deep Learning (Convolutional Autoencoders): Recent advances use convolutional denoising autoencoders (CDAE) to learn noise features and remove them automatically. This approach has shown improvements in noise reduction and, crucially, in preserving Raman peak intensities and shapes [22].

Q3: I see sharp, extremely intense spikes in my spectrum that weren't there in a previous measurement. What are these?

These are cosmic rays or spikes. They are caused by high-energy particles striking the detector and manifest as narrow, random, and intense bands [19] [23] [20].

- Recommended Workflow:

- Detection: Compare successively measured spectra to identify abnormal intensity changes at specific wavenumbers [19]. Algorithms can jointly inspect intensity changes along the wavenumber axis and between successive measurements [19].

- Correction: Once identified, the corrupted data points are replaced. This can be done via interpolation using the intensities from neighboring, unaffected points [19]. Another method is to replace the spike region with intensities from a successive measurement of the same sample at the same wavenumber positions [19].

Q4: I've preprocessed my spectra, but my model performs poorly on data from a different instrument. What went wrong?

This is a classic issue of model transferability. Raman spectra can show significant shifts in band position or intensity between devices due to differences in calibration, laser wavelength, or optical components [19] [24].

- Recommended Workflow:

- Instrument Calibration: Ensure all instruments are properly calibrated using standard materials. This includes both wavenumber calibration (aligning measured band positions to theoretical values) and intensity calibration (correcting for the system's intensity response function) [19].

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV): This normalization technique can help suppress fluctuations in excitation intensity or focusing conditions by centering and scaling each spectrum [19] [4].

- Model Transfer Techniques: Apply dedicated algorithms to remove the systematic spectral variations between different instruments or to adjust the model parameters to account for the new data characteristics [19].

Quantitative Comparison of Preprocessing Methods

The tables below summarize key techniques for baseline correction and denoising to help you select an appropriate method.

Table 1: Comparison of Baseline Correction Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asymmetric Least Squares (ALS) [21] [20] | Iteratively fits a smooth baseline with asymmetric weighting to ignore Raman peaks. | Handles complex, slowly varying baselines well. | Performance depends on penalty and weight parameters. |

| Iterative Polynomial Fitting (I-ModPoly) [20] | Fits a polynomial to the spectrum, iteratively excluding points identified as peaks. | Effective for various fluorescence backgrounds. | Risk of over-fitting or under-fitting with incorrect polynomial degree. |

| SNIP Clipping [19] [20] | Iteratively applies a peak-clipping operator based on local statistics to estimate background. | Robust, non-linear method, works well without peak identification. | Its efficiency can depend on the number of iterations. |

Table 2: Comparison of Denoising Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Savitzky-Golay (SG) Filter [20] | Local polynomial regression within a moving window. | Simple, fast, and well-established. Preserves peak shape and height reasonably well. | Can broaden peaks with large window sizes; choice of parameters is critical. |

| Wavelet Transform [23] | Decomposes signal into frequency components for targeted noise removal. | Superior noise reduction while preserving high-frequency signal features. | Requires manual selection of wavelet type and decomposition level; can be complex. |

| Convolutional Denoising Autoencoder (CDAE) [22] | Deep learning model trained to map noisy spectra to clean ones. | Automated; shows strong performance in preserving peak intensities and shapes. | Requires a training dataset and computational resources. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Preprocessing Steps

Protocol 1: Baseline Correction using Asymmetric Least Squares (airPLS)

Objective: To remove fluorescence background from a raw Raman spectrum using the adaptive iteratively reweighted penalized least squares (airPLS) algorithm [20].

- Input: Raw Raman spectrum (Intensity vector

Iover Wavenumber vectorW). - Parameter Initialization: Set the smoothness parameter

λ(typical range: 10² to 10⁹) and the convergence thresholdtolerance. - Iterative Calculation:

a. Assign initial equal weights

wto all data points. b. Compute the baselinezby minimizing the penalized least squares function:(I - z)^T * (I - z) + λ * (diff(z))^T * (diff(z)). c. Update the weights for points where the intensityIis above the current baselinez(i.e., potential peaks). These points receive lower weights. d. Repeat steps (b) and (c) until the change in the calculated baseline between iterations is less than thetolerance. - Output: The fitted baseline vector

zand the corrected spectrumI_corrected = I - z.

Protocol 2: Denoising using a Savitzky-Golay Filter

Objective: To smooth a Raman spectrum, reducing high-frequency noise while preserving the underlying peak shape [20].

- Input: Raman spectrum (Intensity vector).

- Parameter Selection:

- Window Size: The number of points in the filter window. Must be an odd integer. A good starting point is 5-15 points. A larger window provides more smoothing but may distort sharp peaks.

- Polynomial Order: The order of the polynomial to fit. Typically, order 2 or 3 is used.

- Application:

- For each point in the intensity vector, a polynomial is least-squares fitted to the data within the centered window.

- The value of the central point in the window is replaced by the value of the fitted polynomial at that point.

- The window moves point-by-point through the entire spectrum.

- Output: The smoothed intensity vector.

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Sequential Raman preprocessing workflow.

Diagram 2: Relationship between artifacts and correction methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Raman Spectroscopy Experiments and Validation

| Item | Function in Raman Spectroscopy | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Wavenumber Standard [19] | Calibrates the x-axis (wavenumber shift) of the spectrometer to ensure peak positions are accurate and comparable across instruments. | Measuring a standard like cyclohexane or silicon to generate a calibration function by aligning measured peaks to known theoretical values. |

| Intensity Standard [19] | Calibrates the y-axis (intensity) of the spectrometer to correct for the system's variable response across the spectral range. | Using a white light source or a material with a known emission profile to derive an intensity response function for relative intensity comparisons. |

| Reference Materials (e.g., Tartaric Acid) [24] | Validates the entire analytical workflow, from sample presentation to spectral preprocessing and library matching. | Testing different batches of a raw material (like tartaric acid) to assess and account for material variability (e.g., fluorescence) when building identification libraries. |

| Standardized Software Package (e.g., PyFasma) [20] | Provides a reproducible, modular environment for implementing preprocessing workflows and multivariate analysis. | Batch processing a dataset through spike removal, smoothing, baseline correction, and normalization before performing PCA/PLS-DA for classification. |

Advanced Preprocessing Workflows: A Step-by-Step Guide to Artifact Correction

Troubleshooting Guides

Cosmic Ray Removal

Problem: Sudden, sharp, and narrow spikes of high intensity appear randomly in Raman spectra, obscuring true Raman peaks.

Root Cause: High-energy cosmic particles strike the CCD or CMOS detector during data acquisition [1] [19]. These are random, single-pixel events.

Solution: Implement a detection and correction algorithm based on peak morphology.

- Detection: Identify spikes by their characteristically narrow width and high prominence compared to true Raman peaks [25]. True Raman peaks are broader.

- Correction: Replace the spike-affected spectral points using interpolation from neighboring, unaffected points or from successive measurements at the same wavenumber [1] [19].

- Automation: Use built-in instrument software features (e.g., WiRE software's automated removal for large Raman images) or open-source algorithms that leverage peak width and prominence thresholds for detection [25] [26].

Experimental Protocol: Prominence/Width Algorithm for Spike Removal

- Input: A single raw Raman spectrum or a set of spectra.

- Peak Identification: Use a peak-finding algorithm (e.g., in Python's

scipy.signal) to identify all local maxima in the spectrum. - Feature Calculation: For each detected peak, calculate its width (e.g., full width at half maximum) and its prominence (the vertical distance from the peak to its lowest contour line).

- Spike Identification: Flag peaks where the ratio of prominence-to-width exceeds a defined threshold. Cosmic rays have an extremely high prominence-to-width ratio, whereas true Raman peaks have a lower ratio [25].

- Correction: For each flagged spike, replace the intensity values in the affected region with interpolated values from the immediate surrounding data points.

- Validation: Visually inspect corrected spectra against raw data to ensure all spikes are removed without altering genuine Raman features.

Baseline Correction

Problem: A slowly varying, broad background signal, often from sample fluorescence or instrumental effects, overlaps with and obscures the Raman spectrum [1] [3].

Root Cause: Sample fluorescence, which can be 2-3 orders of magnitude more intense than Raman signals, or broad scattering from optical components [1] [3].

Solution: Apply mathematical techniques to model and subtract the fluorescent background without distorting Raman bands.

- Algorithm Choice: Common methods include asymmetric least squares (AsLS), iterative polynomial fitting, and morphological operations (e.g., Tophat filter) [19] [27].

- Critical Workflow Order: Baseline correction must be performed before spectral normalization. Performing normalization first will bias the normalization constant with the fluorescence intensity, leading to significant errors in subsequent analysis [1].

- Advanced Methods: Convolutional autoencoder (CAE+) models and other deep learning approaches are emerging as powerful tools for effective baseline correction that better preserve Raman peak intensities [22].

Experimental Protocol: Iterative Polynomial Baseline Correction

- Input: A Raman spectrum, preferably with cosmic rays already removed.

- Initial Fit: Fit a low-order polynomial (e.g., 3rd to 6th degree) to the entire spectrum. This initial fit will be influenced by strong Raman peaks.

- Iterative Re-weighting: Identify spectral points where the intensity is significantly above the current polynomial fit. Down-weight these points (considered Raman peaks) in the next iteration.

- Convergence: Repeat the fitting process with updated weights until the polynomial converges to represent only the background, with the Raman peaks effectively excluded from the fit.

- Subtraction: Subtract the final fitted polynomial from the original spectrum to obtain a baseline-corrected spectrum.

Scattering Correction

Problem: Vertical offsets and intensity scaling variations caused by changes in laser power, sample focus, or scattering properties make spectra non-comparable [4] [19].

Root Cause: Fluctuations in experimental conditions, such as laser power stability, slight differences in focusing on the sample, or inherent light scattering properties of the sample itself [19].

Solution: Apply normalization techniques to standardize spectral intensities.

- Technique Selection:

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV): Centers and scales each spectrum by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation [4].

- Vector Normalization: Divides the spectrum by its Euclidean norm (the square root of the sum of squared intensities) [19].

- Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC): A more advanced method that models and removes scattering effects based on a reference spectrum [19].

Experimental Protocol: Standard Normal Variate (SNV) Normalization

- Input: A Raman spectrum that has undergone cosmic ray removal and baseline correction.

- Select Region: Choose the spectral range (R) to be normalized (e.g., 350-3000 cm⁻¹) [4].

- Calculate Mean: Compute the mean intensity,

μ, within the selected region R. - Calculate Standard Deviation: Compute the standard deviation,

σ, of the intensities within region R. - Transform: For every intensity value,

I, in region R, calculate the SNV-corrected value:I_SNV = (I - μ) / σ. - Output: The result is a spectrum with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one over the selected region, making it directly comparable to other similarly processed spectra.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is the order of preprocessing steps so critical? The order is paramount to prevent the introduction of artifacts and data bias. A specific and critical rule is that baseline correction must always be performed before normalization. If normalization is done first, the intense fluorescence background becomes encoded into the normalization factor, biasing all subsequent data and machine learning models [1]. The recommended workflow is: Cosmic Ray Removal -> Wavenumber/Intensity Calibration -> Baseline Correction -> Smoothing (if needed) -> Normalization.

Q2: My baseline correction is removing or distorting my Raman peaks. What am I doing wrong? Over-optimized preprocessing is a common mistake [1]. This often occurs when the parameters of the baseline correction algorithm (e.g., polynomial degree, smoothing tolerance) are set too aggressively. To avoid this:

- Use a grid search to find optimal parameters, using the quality of the resulting spectral features as the metric, not the final model performance [1].

- Consider using deep learning-based baseline correction methods (e.g., CAE+ models), which are designed to correct the baseline while better preserving Raman peak intensities and shapes [22].

Q3: Are there any fully automated and reliable methods for cosmic ray removal? Yes, several automated methods exist. Beyond the manual/iterative checks, you can use:

- Instrument Software: Many commercial systems (e.g., Renishaw's WiRE software) include automated cosmic ray filtration for large datasets [26].

- Open-Source Algorithms: Recent intuitive algorithms based on peak prominence and width ratios offer automated detection of cosmic rays down to low signal-to-noise ratios and are available as open-source Python code [25].

Q4: How does scattering correction like SNV differ from baseline correction? These techniques address fundamentally different problems:

- Baseline Correction targets additive effects, such as fluorescence, which manifest as a slow, wavy drift underneath the Raman peaks. It corrects the signal offset, primarily in the vertical direction.

- Scattering Correction (e.g., SNV, MSC) targets multiplicative effects, such as variations in overall signal intensity due to scattering or focus changes. It adjusts the scale and offset of the entire spectrum to make it comparable to others [4] [19].

Data Presentation

Quantitative Comparison of Preprocessing Algorithms

| Technique Category | Specific Method | Key Parameters | Advantages | Limitations / Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cosmic Ray Removal | Prominence/Width Ratio [25] | Prominence/Width threshold | Intuitive, detects low-intensity spikes, open-source | May require tuning for novel sample types |

| Median Filtering [28] | Window size | Simple, fast on successive measurements | Less effective on single spectra | |

| Baseline Correction | Iterative Polynomial Fitting | Polynomial degree, tolerance | Handles complex, wavy baselines | Overfitting can distort/remove Raman peaks [1] |

| Asymmetric Least Squares (AsLS) | Smoothness (λ), Asymmetry (p) | Robust for many fluorescence types | Parameter selection is critical [22] | |

| Convolutional Autoencoder (CAE+) [22] | Network architecture | Automated, preserves peak intensity | Requires training data and computational resources | |

| Scattering Correction | Standard Normal Variate (SNV) [4] | Spectral region (R) | Centers & scales spectra, simple calculation | Sensitive to the chosen spectral region |

| Vector Normalization [19] | Spectral region (R) | Simple, preserves spectral shape | Does not correct for additive baselines | |

| Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) [19] | Reference spectrum | Models and removes scattering effects | Performance depends on a good reference spectrum |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent & Material Solutions

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| 4-Acetamidophenol | Wavenumber calibration standard with multiple sharp peaks [1]. | Calibrating the wavenumber axis before measurement campaigns to ensure spectral comparability across days. |

| Stainless Steel Slides | Substrate with low Raman background [26]. | Replacing glass slides for measuring biological cells to minimize unwanted spectral contributions from the substrate. |

| Bandpass & Longpass Filters | Optical filtering to ensure a clean laser line and isolate Stokes Raman scattering [29]. | Integrated into the spectrometer setup to block laser plasma lines and Rayleigh scatter, ensuring a clean signal. |

| Intensity Calibration Standard | A material with a known, stable emission profile (e.g., a white light source) [19]. | Correcting for the spectral transfer function of the spectrometer to generate setup-independent Raman spectra. |

FAQs: Smoothing and Normalization

Q1: Why is smoothing applied to Raman spectra, and when is it necessary? Smoothing is a preprocessing step used to suppress random noise introduced by the instrument's detector and electronic components [3]. It is typically recommended only for highly noisy data [19]. Oversmoothing can degrade the subsequent analysis by distorting the genuine Raman bands, so its application should be cautious and validated [19].

Q2: What are the common methods for spectral smoothing? Smoothing is usually achieved via a moving-window low-pass filter [19]. Common algorithms include:

- Savitzky-Golay Filter: A polynomial smoothing filter that preserves the shape and height of spectral peaks better than a simple moving average.

- Gaussian Filter: Applies weights according to a Gaussian distribution within the moving window.

- Mean or Median Filter: A simple moving window that calculates the average or median value.

Q3: What is the purpose of normalization in Raman spectroscopy? Normalization is performed to suppress variations in spectral intensity that are not related to the sample's chemical composition. These fluctuations can be caused by changes in the excitation laser intensity, sample focusing conditions, or sample volume probed [19] [30]. It enables the comparison of spectra based on their relative band intensities rather than absolute intensity.

Q4: My machine learning model is overfitting. Could my preprocessing be the cause? Yes. The choice of preprocessing, including smoothing and normalization, strongly influences analysis results and can introduce artifacts if not chosen appropriately [31] [32]. An optimal pre-treatment method depends on the specific dataset and the goal of the analysis [32]. It is crucial to evaluate the model's performance on a separate, unprocessed test set to diagnose overfitting related to preprocessing.

Q5: How do I choose the right normalization method? The choice depends on your sample and experimental goal. The table below summarizes common techniques.

Table 1: Common Normalization Techniques in Raman Spectroscopy

| Normalization Method | Brief Description | Best Used When |

|---|---|---|

| Area Normalization (Vector Norm) | Spectral intensities are divided by the total area under the spectrum [19]. | The total amount of sample is constant, and you are interested in relative compositional changes. |

| Peak Height Normalization | Intensities are divided by the height of an internal standard peak [19]. | A specific, stable Raman band from a known component is present in all samples. |

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) | Each spectrum is centered (mean) and scaled (standard deviation) independently [19]. | Dealing with scattering effects (e.g., in powders or solids) and path length variations. |

| Min-Max Normalization | Scales the spectrum to a fixed range (e.g., 0 to 1). | Simple scaling for comparative visualization is needed. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Loss of Peak Resolution After Smoothing

Problem: After smoothing, the Raman bands appear broader, and closely spaced peaks are no longer distinguishable. Solution:

- Reduce the smoothing window size. A larger window aggressively removes noise but also smears sharp features.

- Re-evaluate the necessity of smoothing. If the raw data is of high quality, smoothing might be omitted.

- Try the Savitzky-Golay filter, which is generally better at preserving peak shape and height compared to a simple moving average [33].

Prevention Protocol:

- Always compare the smoothed spectrum with the raw data to visually inspect for feature distortion.

- Optimize data acquisition parameters (e.g., increase integration time) to obtain a higher signal-to-noise ratio initially, reducing the need for aggressive smoothing.

Problem: The smoothing algorithm creates "ripples" or false peaks near sharp spectral features or distorts the baseline. Solution:

- This is often a sign of an excessively large smoothing window.

- Immediately reduce the window size and reprocess the data.

- Ensure the smoothing step is performed after baseline correction in your workflow. Applying smoothing to a spectrum with a strong fluorescent baseline can compound errors [19].

Prevention Protocol:

- Follow a standardized preprocessing sequence: Cosmic ray removal → Baseline correction → Smoothing → Normalization [19] [30].

- Use algorithms with parameters that are less prone to creating artifacts, such as the Savitzky-Golay filter with a low polynomial order.

Issue 3: Poor Classification Performance or High Model Error After Normalization

Problem: After applying normalization, your multivariate classification or regression model performs poorly on validation data. Solution:

- Reconsider your normalization method. The chosen method might be removing critical variance related to your property of interest. For instance, using total area normalization when the total concentration varies between samples can be detrimental.

- Test alternative normalization techniques from Table 1. The optimal method is highly dataset-dependent [32].

- Validate without normalization to establish a performance baseline.

Prevention Protocol:

- The optimal pre-treatment method depends on the characteristics of the data set and the goal of data analysis [32]. Systematically evaluate different preprocessing combinations on a separate validation set, not the final test set, to avoid bias.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Smoothing Parameters

This protocol helps determine the optimal smoothing parameters for your dataset before proceeding with quantitative analysis.

Materials:

- Raw Raman spectra (after cosmic spike removal and baseline correction).

- Data analysis software (e.g., Python with SciPy, PyFasma [34], ORPL [30]).

Methodology:

- Select a Representative Spectrum: Choose a spectrum from your dataset that has a representative signal-to-noise ratio and contains all critical spectral features.

- Apply Smoothing: Apply your chosen smoothing algorithm (e.g., Savitzky-Golay) to the spectrum using a range of parameters (e.g., window sizes from 5 to 25 points, polynomial order 2 or 3).

- Calculate a Quality Metric: For each smoothed spectrum, calculate the Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between the smoothed spectrum and the raw spectrum. Plot the RMSE versus the window size.

- Visual Inspection: Overlay the smoothed spectra with the raw data. Identify the point where the noise is sufficiently reduced without visible distortion of the Raman bands.

- Final Selection: Choose the parameter set that offers a good compromise between noise reduction (low RMSE) and feature preservation based on visual inspection. Apply this parameter to the entire dataset.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Normalization Methods for Model Generalization

This protocol compares normalization techniques to identify the one that leads to the most robust machine learning model.

Materials:

- Preprocessed Raman spectra (cosmic rays removed, baseline corrected, and smoothed).

- Known reference values or class labels for the samples.

- Machine learning environment (e.g., Python with scikit-learn, PyFasma [34]).

Methodology:

- Data Splitting: Split your dataset into training and hold-out test sets.

- Normalization Trials: Normalize the training set using several different methods (e.g., Area, SNV, Peak Height). It is critical to calculate the normalization parameters (like mean area) from the training set only and then apply these parameters to the test set to avoid data leakage.

- Model Training and Validation: Train an identical model (e.g., PLS-DA or PCA-LDA) on each of the normalized training sets. Evaluate performance using a cross-validation protocol on the training set.

- Final Evaluation: Apply the best-performing normalization method from step 3 to the hold-out test set and evaluate the model's final performance.

- Result Interpretation: The normalization method that yields the highest cross-validation and test set accuracy is the most appropriate for your specific application.

Workflow and Decision Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence for applying smoothing and normalization within a complete Raman data preprocessing workflow, highlighting key decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools for Raman Preprocessing

| Tool / Solution Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Smoothing & Normalization |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyFasma [34] | Open-source Python Package | Integrates essential preprocessing tools and multivariate analysis. | Provides implemented algorithms for smoothing and multiple normalization techniques within a reproducible framework. |

| Open Raman Processing Library (ORPL) [30] | Open-sourced Python Package | A modular package for processing Raman signals, optimized for biological samples. | Offers tools for the entire preprocessing workflow, including the novel "BubbleFill" baseline algorithm, preceding smoothing and normalization. |

| BubbleFill Algorithm [30] | Morphological Baseline Removal Algorithm | A novel method for removing complex fluorescence baselines. | Critical pre-normalization step. A poorly corrected baseline can severely distort subsequent normalization. |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter [33] | Digital Filter | Smooths data by fitting a polynomial to successive subsets of the spectrum. | A gold-standard smoothing technique that effectively reduces noise while preserving the underlying spectral shape. |

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) [19] | Scatter Correction & Normalization Technique | Corrects for light scattering and path length variations. | A specific normalization method highly useful for solid or turbid samples where scattering effects are significant. |

FAQs: Principal Component Analysis in Spectral Data Management

Q1: What is the primary benefit of using PCA on handheld Raman spectral data? PCA reduces the high dimensionality of Raman spectra by transforming the original variables (intensities at many wavelengths) into a smaller set of new, uncorrelated variables called Principal Components (PCs). This process compresses the data while preserving its essential variance, which helps mitigate the effects of spectral noise and artifacts, simplifies data visualization, and improves the performance of downstream machine learning models [35] [36] [37].

Q2: My PCA model performs well on calibration data but poorly on new data. What could be wrong? This is a classic sign of overfitting, often caused by applying PCA to a dataset containing outliers or without proper validation. To correct this:

- Detect Outliers: Use metrics like Cook's Distance on your raw or reconstructed spectral data to identify and remove highly influential outlier spectra before building the final PCA model [37].

- Apply Cross-Validation: Always use k-fold cross-validation (e.g., k=3) during the model development phase to ensure its robustness and generalizability [37].

Q3: How can I determine the optimal number of Principal Components to retain? The goal is to retain enough components to capture the essential signal while discarding noise. A standard method is to use a Scree Plot, which graphs the variance explained by each component. The optimal number is often at the "elbow" of the plot, where the cumulative variance approaches an acceptable threshold (e.g., >95-99%) before the curve flattens [35] [38].

Q4: When should I consider methods other than PCA for my Raman data? While PCA is excellent for linear relationships and noise reduction, consider non-linear methods if your data has complex, non-linear structures. Techniques like Kernel PCA (KPCA), t-SNE, or UMAP may be more effective if:

- PCA fails to provide clear cluster separation in the scores plot.

- You are primarily interested in visualizing complex, non-linear groupings within your data [38].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common PCA Challenges in Handheld Raman

Issue 1: Poor Cluster Separation in PCA Scores Plot

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overlapping clusters in the PC1 vs. PC2 scores plot, making class discrimination difficult. | High Fluorescence Background: Swamps the weaker Raman signal, adding non-informative variance [2]. | Apply background correction algorithms (e.g., rolling ball, asymmetric least squares) before PCA to remove fluorescent baseline [39] [2]. |

| Spectral Artifacts: Cosmic rays or instrument noise are misinterpreted as genuine spectral features [2]. | Implement pre-processing: use cosmic ray removal and apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) normalization to reduce scattering effects [39] [38]. | |

| Insufficient Chemical Contrast: The genuine molecular differences between samples are minor. | Combine PCA with supervised methods like Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the principal components to enhance class separation [40] [39]. |

Issue 2: Instability and Interpretability of PCA Model

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The PCA loadings are dominated by noise, or the model is sensitive to minor changes in the data. | High-Frequency Noise: PCA attempts to model random noise, which can dominate higher-order components [2]. | Apply a smoothing filter (e.g., Savitzky-Golay) to the spectra. Retain fewer components, focusing on those that capture the broad, chemically relevant spectral peaks [39]. |

| Data Scaling Issues: Variables (Raman shifts) with high intensity but low information dominate the variance [37]. | Use Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Mean-Centering scaling before PCA to ensure all variables are on a comparable scale and the model is not biased by absolute intensity [37] [38]. | |

| Loadings are difficult to interpret in terms of known chemical signatures. | The principal components are linear mixtures of multiple underlying chemical variances, which is inherent to PCA. | Use Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) as an alternative, which often yields more chemically interpretable components due to its non-negativity constraint [41]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Standard Workflow for PCA on Handheld Raman Data

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide to mitigate spectral artifacts and build a robust PCA model, based on methodologies from recent literature [39] [37] [38].

Objective: To preprocess handheld Raman spectra, perform PCA for dimensionality reduction and exploratory data analysis, and validate the model for stability.

Materials & Software:

- Handheld Raman spectrometer

- Samples for analysis

- Computing environment (e.g., Python with Scikit-learn, R, MATLAB)

- Spectral preprocessing scripts (e.g., for SNV, detrending)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Data Acquisition & Averaging:

- Collect multiple spectra (e.g., n=5-10) from different spots on each sample.

- Average these spectra to create a single, representative spectrum per sample, reducing random noise [39].

Spectral Preprocessing (Critical for Artifact Mitigation):

- Cosmic Ray Removal: Identify and remove sharp, spiky peaks using dedicated algorithms [39] [2].

- Background/Fluorescence Correction: Apply a baseline correction method (e.g., rolling ball, polynomial fitting) to subtract the fluorescent background [39] [2].

- Normalization: Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or vector normalization to correct for path length and scattering effects, and mean-center the data [37] [38].

Dimensionality Reduction with PCA:

- Input the preprocessed spectral matrix (samples x wavenumbers) into the PCA algorithm.

- Extract principal components. The first few (PC1, PC2, PC3) typically capture the majority of the structured variance.

Model Validation:

Workflow Visualization

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings on the performance and effectiveness of PCA from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of PCA in Various Spectral Applications

| Application Context | Key Metric | Reported Value / Outcome | Reference & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Release Prediction (Polysaccharide-coated drugs) | Data Dimensionality Reduction | Input: >1500 spectral features → Output: Reduced set of principal components. | [37]: PCA was used as a preprocessing step before machine learning, simplifying the feature space. |

| Phase Transition Detection (Polycrystalline BaTiO₃) | Successful Phase Identification | PCA determined the tetragonal-to-cubic phase transition pressure at ~2.0 GPa. | [35]: Demonstrated PCA's ability to identify subtle structural changes from Raman spectra. |

| NIR Spectra Analysis (Paracetamol) | Variance Captured by First Two PCs | The first two principal components captured ~100% of the total variance. | [38]: Highlights PCA's efficiency in capturing nearly all information in a reduced dimension. |

| Hyperspectral Image Classification (Organ Tissues) | Comparative Classification Accuracy | Accuracy with Full Data: 99.30%. Accuracy with STD-based Reduction: 97.21%. | [40]: Provided for context; shows that simpler band selection can approach PCA's performance, but PCA is more robust for complex artifacts. |

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials & Tools

Table 2: Key Computational and Experimental Reagents for PCA-based Spectral Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Normal Variate (SNV) | Spectral normalization technique that removes scattering artifacts and corrects for path length differences, ensuring data is on a comparable scale for PCA [38]. | A standard preprocessing step in most spectral analysis pipelines. |

| Rolling Ball / Asymmetric Least Squares (AsLS) | Algorithm for estimating and subtracting the fluorescent baseline from Raman spectra, which is a common artifact that can dominate the first principal component [39] [2]. | Crucial for analyzing biological samples or impurities that fluoresce. |

| Savitzky-Golay Filter | Digital filter that can be used for smoothing spectra (reducing high-frequency noise) and calculating derivatives, improving the signal-to-noise ratio before PCA [39]. | Helps prevent PCA from modeling high-frequency noise. |

| Cook's Distance | A statistical metric used to identify influential outliers in a dataset. Applied to the PCA-reconstructed data to find spectra that disproportionately influence the model [37]. | Essential for building a robust and generalizable PCA model. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | A resampling procedure used to evaluate the stability of the PCA model by partitioning the data into 'k' subsets and iteratively training on k-1 folds and validating on the remaining fold [37]. | Typically, k=3 or k=5 is used to ensure the model is not overfitted to one specific data split. |

In pharmaceutical quality control, the verification of raw materials is a critical first step to ensure drug safety and efficacy. Handheld Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful tool for this application, enabling rapid, non-destructive identification of materials directly through transparent packaging, thereby reducing inspection time and contamination risk [42] [43]. However, the reliability of these identifications depends entirely on the quality of the spectral data acquired. Spectral artifacts—unwanted features not inherent to the sample—can compromise data integrity, leading to false acceptances or rejections of raw materials [2].

This case study examines a systematic approach to identifying, troubleshooting, and mitigating common spectral artifacts encountered during the verification of pharmaceutical raw materials using handheld Raman spectroscopy. By framing this within a broader research thesis on spectral data quality, we provide a proven framework for researchers and drug development professionals to enhance the accuracy of their analytical methods.

Understanding Common Spectral Artifacts: A Troubleshooter's Guide

Artifacts in Raman spectroscopy can originate from the instrument, the sampling process, or the sample itself [2]. The following table summarizes the most frequent challenges faced during raw material verification.

Table 1: Common Artifacts in Handheld Raman Spectroscopy for Raw Material Verification

| Artifact Type | Primary Cause | Impact on Spectrum | Common in Pharmaceutical Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | Sample impurities or the material itself emitting light [2] [44] | A broad, sloping baseline that can obscure weaker Raman peaks [2] [44] | Cellulose, dextrin, certain APIs [43] |

| Laser-Induced Sample Degradation | Laser power density exceeding the sample's threshold [2] | Changes in peak shapes and intensities during measurement | Heat-sensitive or colored compounds |

| Cosmic Rays | High-energy radiation striking the detector [2] | Sharp, intense, random spikes | Can occur in any measurement |

| Ambient Light Interference | Leakage of room lighting into the optical path | Increased background noise, reduced signal-to-noise ratio | Measurements taken outside a controlled light environment |

| Fluorescence | Sample impurities or the material itself emitting light [2] [44] | A broad, sloping baseline that can obscure weaker Raman peaks [2] [44] | Cellulose, dextrin, certain APIs [43] |

| Package-Induced Signal | Raman signal from the container (e.g., glass vial, plastic bag) | Peaks from the packaging material superimposed on the sample spectrum | Materials analyzed through blister packs or plastic bags [42] |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides for Specific Issues

FAQ 1: How can I mitigate intense fluorescence from a raw material like cellulose or dextrin?

Fluorescence is a predominant issue, particularly with organic raw materials. Mitigation requires a combination of instrument settings and procedural techniques.

- Use Instrument-Specific Fluorescence Mitigation: If your handheld spectrometer has a dedicated fluorescence suppression technology (e.g., SSE), ensure it is activated [44].

- Employ Photobleaching: Before collecting the final spectrum, shine the laser on the sample spot for a longer period. The fluorescence often decays over time, allowing the Raman signal to be measured. This technique was used successfully for fluorescent materials like cellulose and trimagnesium phosphate [43].

- Laser Wavelength Selection: While fixed in a handheld device, this is a key design consideration. Using a 785 nm laser, as in the TruScan instrument, helps minimize fluorescence compared to shorter wavelengths like 532 nm [42] [43].

FAQ 2: I see sharp, random spikes in my spectrum. What are they, and how do I remove them?

These are almost certainly cosmic rays. They are not a defect of the instrument but an environmental phenomenon.

- Solution: Modern Raman instrument software typically includes an algorithm for cosmic ray removal. This algorithm identifies and filters out these sharp, single-pixel spikes. Ensure this feature is enabled in your acquisition method [2].

- Verification: If unsure, simply repeat the measurement. Cosmic rays are random and will not appear in the same spectral location in consecutive acquisitions.

FAQ 3: The spectrum of my material in a plastic bag shows extra peaks. What should I do?

You are likely seeing the Raman signal from the plastic packaging itself.

- Solution: The most effective strategy is to create a reference spectrum of the empty packaging material and subtract it from the sample spectrum using the instrument's software. Advanced analyzers like the TruScan RM are explicitly designed for non-contact analysis through plastic bags and glass containers, and their software can handle this complexity [42].

- Best Practice: Always use a consistent type of transparent packaging for your raw materials to simplify the background subtraction process.

FAQ 4: My sample appears to be changing or burning during analysis. How can I prevent this?

This indicates laser-induced thermal degradation. The laser power density is too high for the sample.

- Solution: Reduce the laser power. Most handheld instruments with an "auto" mode will handle this automatically, optimizing laser power and exposure time to get a good signal without damaging the sample [43]. For manual operation, systematically reduce the power or defocus the laser beam on the sample surface.

Experimental Protocol: A Case Study on Raw Material Verification

The following workflow, based on a study using the TruScan handheld Raman spectrometer, outlines a robust methodology for verifying 28 common pharmaceutical raw materials, including active ingredients and excipients [43].

Title: Raw Material Verification Workflow

Key Steps:

- Reference Acquisition: A reference spectrum of the pure raw material is acquired through the wall of a borosilicate glass vial using a "reference" handheld instrument [43].

- Method Creation: A verification method is created using the reference spectrum. The study used a probability-based algorithm that evaluates whether an unknown spectrum lies within the multivariate domain of the reference, given the measurement uncertainty. This is more robust than simple correlation [43].

- Method Transfer: The method file is transferred to multiple "test" handheld units, demonstrating the ease of method transferability across instruments [43].

- Field Verification: For an unknown sample, the operator selects the method, measures the material through its packaging (e.g., a 2-mm thick polyethylene bag), and initiates the scan. The instrument uses an "auto" mode to automatically optimize data acquisition parameters (exposure time, accumulations, laser power) to achieve the required signal-to-noise ratio as quickly as possible [43].

- Identity Check: The instrument's software compares the unknown spectrum to the library reference and calculates a p-value. A p-value ≥ 0.05 indicates the spectra are consistent, and the material is verified (Pass). A p-value < 0.05 indicates a significant discrepancy, and the material fails [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Handheld Raman Raw Material Verification

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Handheld Raman Spectrometer (e.g., TruScan) | The primary analytical instrument. Features a 785 nm laser, CCD detector, and software for spectral acquisition and analysis [43]. |

| Borosilicate Glass Vials | Ideal container for acquiring reference spectra, as it provides a consistent, low-Raman-signal background [43]. |

| Polyethylene Bags (2-mm thick) | Simulates common industrial packaging for raw materials; allows for non-invasive, through-container verification [43]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | High-purity materials from suppliers like Sigma-Aldrich used to build accurate spectral libraries [43]. |

| Vial Holder / Nose-Cone Attachment | Ensures consistent and correct focal distance between the laser aperture and the sample, which is critical for spectral reproducibility [43]. |

| Spectral Database/Library Software | Web-based or onboard software for storing reference spectra, creating verification methods, and performing statistical comparisons [43]. |

The successful implementation of handheld Raman spectroscopy for 100% raw material inspection in the pharmaceutical industry hinges on a deep understanding of spectral artifacts. As demonstrated in this case study, a systematic approach—combining knowledge of artifact origins, strategic troubleshooting, and a robust, standardized experimental protocol—can effectively mitigate these issues. The use of advanced algorithms that go beyond simple spectral correlation further strengthens the reliability of the verification process. By adopting these practices, researchers and quality control professionals can confidently leverage handheld Raman technology to enhance supply chain security, accelerate production, and safeguard product quality.

Troubleshooting Field Data and AI-Driven Optimization Strategies

Procedures for On-Site Artifact Diagnosis in Field Applications

Quick-Reference: Common Artifacts and Initial Mitigation Steps

The table below summarizes the most frequently encountered artifacts in field Raman spectroscopy, their observable symptoms, and immediate corrective actions you can take on-site.

| Artifact Type | Common Symptoms in Spectrum | Immediate On-Site Mitigation Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence | A steep, sloping baseline that obscures or overwhelms Raman peaks [2] [45]. | Switch to a near-infrared laser source (e.g., 785 nm) if available [45]. Use shifted-excitation Raman difference spectroscopy (SERDS) if instrument is equipped [46]. |

| Cosmic Rays | Sharp, narrow, single-pixel spikes of very high intensity [45]. | Utilize the instrument's automated cosmic ray removal software [45]. Re-measure the point to confirm the artifact's disappearance. |

| Sample/Instrument Motion | Broad baseline shifts, distorted peak shapes, and general signal instability [2]. | Ensure the instrument probe is stabilized against the sample or packaging. Use a sample holder or jig for consistent positioning. |

| Ambient Light Interference | A noisy, elevated baseline, often with sharp spikes from room lights [46]. | Shield the measurement point from ambient light. Use a charge-shifting detection method if available [46]. |

| Laser-Induced Damage | Changes in peak positions or intensities, or the appearance of new bands (e.g., burning) during measurement [2] [45]. | Immediately lower the laser power. Use the instrument's line-focus or defocusing mode to spread the power over a larger area [45]. |

| Container/Substrate Interference | Broad bands or specific peaks that do not correspond to the sample of interest [45]. | Increase confocality to minimize signal from container walls. Use low numerical aperture (NA) lenses to focus deeper into a bulk sample within a container [45]. |

Detailed Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do I diagnose and correct a dominant fluorescence background during outdoor measurements?

Issue: You are attempting to identify a substance in the field, but the collected spectrum is dominated by a strong, sloping fluorescence background, masking the Raman signal. This is often exacerbated by varying sunlight.

Diagnosis Procedure:

- Visual Inspection: Observe the raw spectrum. A true Raman signal will have a relatively flat baseline with sharp, characteristic peaks. Fluorescence presents as a broad, valley-like background [2].

- Change Laser Wavelength: If your handheld device has multiple lasers, switch from a visible wavelength (e.g., 532 nm) to a near-infrared (NIR) laser (e.g., 785 nm). NIR excitation significantly reduces fluorescence for most samples [45].

- Check Ambient Light: Note if the interference changes with cloud cover or shading, indicating a dynamic component from ambient light [46].

Corrective Protocols:

- For Static Fluorescence: Use Shifted-Excitation Raman Difference Spectroscopy (SERDS). This technique uses two laser wavelengths with a very small shift. Since Raman peaks shift with the laser line but fluorescence does not, subtracting the two collected spectra effectively removes the fluorescent background [46].

- For Dynamic Interference (Varying Light): Employ Charge-Shifting (CS) Detection if available. This method uses a specialized CCD and rapid switching to subtract varying ambient light interference during acquisition itself. For the most challenging conditions, a combined SERDS-CS approach is optimal for rejecting both static fluorescence and dynamic ambient light [46].

- Post-Processing: Apply a baseline correction algorithm (e.g., asymmetric least squares, polynomial fitting) during data analysis. Note that over-optimization of these parameters can lead to artifacts and should be done with care [1].

FAQ 2: The spectrum shows sharp, random spikes. Are these cosmic rays or a real sample component?

Issue: Your spectra contain intense, narrow spikes that were not present in previous measurements of the same substance.

Diagnosis Procedure:

- Spatial Test: Move the instrument slightly and re-measure the same spot or an adjacent spot. Cosmic rays are random events and will not reappear in the exact same spectral position in the new measurement.

- Temporal Test: Perform a second measurement at the same spot with identical parameters. A cosmic ray artifact will disappear, while a real Raman peak will be reproducible.

Corrective Protocols:

- Automated Removal: Most modern Raman systems include automated cosmic ray removal in their operating software (e.g., WiRE software). This is the preferred first step [45].