Mitigating Temperature Effects in Spectroscopic Measurements: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Temperature variations present a significant challenge in spectroscopic measurements, inducing spectral shifts and broadening that compromise data integrity and analytical results.

Mitigating Temperature Effects in Spectroscopic Measurements: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Temperature variations present a significant challenge in spectroscopic measurements, inducing spectral shifts and broadening that compromise data integrity and analytical results. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of temperature effects, covering the fundamental physical mechanisms, advanced methodological corrections, and data-driven optimization strategies. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current research on techniques ranging from phase error correction and evolutionary rank analysis to machine learning-based compensation. The scope includes practical troubleshooting guidance and a comparative analysis of validation frameworks, offering a holistic resource for achieving temperature-robust spectroscopy in biomedical and clinical settings.

Understanding the Core Challenge: How Temperature Variations Fundamentally Alter Spectral Data

Within the broader thesis on addressing temperature variations in spectroscopic measurements, understanding thermal spectral interference is paramount. Fluctuations in sample temperature introduce significant analytical challenges, primarily manifesting as band shifting, broadening, and overlap in vibrational spectra. These anomalies compromise data integrity, leading to inaccurate peak identification, erroneous quantitative measurements, and ultimately, unreliable scientific conclusions [1]. In pharmaceutical development and analytical research, where precision is critical, such temperature-induced effects can obscure vital molecular information, affecting everything from polymorph identification in active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) to reaction monitoring in complex synthetic pathways.

The fundamental physics stems from the temperature dependence of molecular vibrations. As thermal energy increases, anharmonicity in the molecular potential energy surface becomes more pronounced, altering vibrational energy level spacings and transition probabilities [2]. This review establishes a structured troubleshooting framework to identify, diagnose, and mitigate these thermal interference effects, providing researchers with practical methodologies to safeguard data quality across diverse spectroscopic applications.

Core Concepts: Thermal Effects on Spectral Features

Thermal energy perturbs molecular systems through several physical mechanisms, each producing characteristic spectral signatures that complicate interpretation and analysis.

Band Broadening Mechanisms

Thermal effects primarily induce band broadening through two complementary pathways: collisional broadening and rotational line broadening. As temperature rises, molecules experience increased collision rates, shortening the lifetime of vibrational states and, through the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, broadening spectral lines [2]. Simultaneously, the population distribution across a wider range of rotational energy levels smears the fine structure of vibrational transitions, particularly evident in gas-phase spectroscopy. In condensed phases, these mechanisms operate cooperatively with solvent-induced effects, creating complex band shapes that challenge quantitative analysis.

Band Shifting Phenomena

Temperature-dependent band shifting occurs through two dominant mechanisms. Thermal expansion of molecular crystals alters intermolecular distances and force constants, progressively shifting vibrational frequencies. More fundamentally, the anharmonicity of molecular vibrations means that increased thermal population of excited states leads to frequency shifts, as described by the vibrational Schrödinger equation for an anharmonic oscillator [2]. This "pseudocollapse" phenomenon manifests as progressive broadening of bands arising from an anharmonic potential, producing shifts having no direct relation to chemical reaction rates.

Band Overlap Complications

As individual bands broaden and shift with temperature changes, previously resolved spectral features frequently converge, creating problematic band overlap. This convergence diminishes analytical specificity, particularly in complex biological or pharmaceutical samples where multiple components with similar functional groups coexist. The resulting composite bands hinder accurate peak integration for quantitative analysis and may obscure minor spectral features indicative of critical sample properties, such as polymorphic forms or degradation products.

Table: Primary Thermal Effects on Spectral Features

| Thermal Effect | Physical Origin | Spectral Manifestation | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Broadening | Increased collision rates & rotational state distribution | Wider peaks with reduced amplitude | Decreased resolution, impaired peak separation |

| Band Shifting | Anharmonicity & thermal expansion of crystal lattices | Peak position changes | Incorrect compound identification, calibration errors |

| Band Overlap | Combined broadening and shifting of adjacent peaks | Merging of previously distinct peaks | Loss of analytical specificity, inaccurate quantification |

Troubleshooting Guide: Q&A for Experimental Challenges

Diagnostic Framework for Thermal Spectral Anomalies

Q1: How can I determine if temperature variations are causing the spectral abnormalities I'm observing?

Begin with systematic diagnostics to confirm thermal origins. First, document the specific anomaly pattern—whether it manifests as baseline instability, peak suppression, or excessive spectral noise [1]. Compare sample spectra collected at different, carefully controlled temperatures using a temperature stage or environmental chamber. If the anomalies reproduce consistently with temperature cycling, thermal interference is likely. For confirmation, record blank spectra under identical thermal conditions; if the blank exhibits similar baseline drift or instability, the issue may be instrumental (e.g., interferometer thermal expansion in FTIR) rather than sample-specific [1].

Q2: What specific spectral patterns indicate temperature-related band broadening versus shifting?

Band broadening typically presents as a progressive decrease in peak height with corresponding increase in peak width at half-height as temperature increases, while the integrated peak area remains relatively constant. In contrast, band shifting manifests as systematic movement of peak maxima to different wavenumbers or wavelengths with temperature changes. These phenomena frequently occur together, creating the appearance of "smearing" across a spectral region. To distinguish them, track specific peak parameters (position, height, width at half-height, area) across a temperature gradient and plot their temperature dependence [2].

Q3: Why do my sample spectra show increased noise and baseline drift during temperature ramping experiments?

Baseline instability during temperature ramping typically results from multiple compounding factors. Sample cell windows may exhibit slight thermal expansion, altering the optical path length. Temperature gradients across the sample can create refractive index variations that scatter incident radiation. Additionally, temperature-induced changes to the sample matrix, such as altered hydrogen bonding networks or conformational equilibria, can produce genuine but unwanted spectral changes. Implement a sealed, temperature-equilibrated reference cell containing only solvent or matrix material to distinguish instrument-related baseline effects from sample-specific phenomena [1] [3].

Resolution and Mitigation Strategies

Q4: What experimental controls can minimize thermal interference in sensitive spectroscopic measurements?

Implement rigorous thermal management protocols: allow extended equilibration times at each measurement temperature (typically 10-15 minutes for small volume samples), use temperature stages with active stability control (±0.1°C or better), and employ samples with minimal thermal mass for rapid equilibration. For solution studies, utilize sealed cells to prevent evaporation-related cooling effects. In solids characterization, ensure uniform powder compaction and thermal contact to minimize thermal gradients. Most critically, maintain consistent sample preparation protocols across comparative experiments, as variations in particle size, crystallinity, or concentration can exacerbate temperature-dependent spectral changes [1] [3].

Q5: How can I resolve overlapping peaks caused by thermal broadening?

Apply mathematical deconvolution techniques to resolve overlapping features, but only after careful validation. Frequency-dependent Fourier self-deconvolution can narrow individual bands, while second derivative spectroscopy enhances separation of overlapping features. For quantitative analysis, implement curve-fitting with appropriate line shapes (e.g., Voigt profiles that combine Gaussian and Lorentzian character). However, these computational approaches cannot fully recover information lost to severe overlap; the optimal strategy remains preventing excessive broadening through careful temperature control during data acquisition [3].

Q6: What reference materials are suitable for monitoring temperature-dependent spectral changes?

Certified thermal reference materials with well-characterized temperature-dependent spectra provide essential validation. Polystyrene films exhibit specific infrared bands with known temperature dependencies suitable for FTIR validation. For Raman spectroscopy, the temperature-dependent shift of the silicon phonon band at approximately 520 cm⁻¹ provides an intrinsic reference. In research applications, low-temperature (77K) spectra in frozen matrices often provide the highest resolution references for comparison with room-temperature data, revealing thermally-induced changes through differential analysis [1].

Table: Troubleshooting Thermal Spectral Anomalies

| Symptom | Possible Thermal Causes | Immediate Actions | Long-term Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Progressive baseline drift | Uneven sample heating, cell window expansion | Extend temperature equilibration, reseal cell | Use temperature-stabilized sample compartment, matched reference cell |

| Unexpected peak broadening | Excessive temperature gradients, rapid scanning | Slow temperature ramp rate, improve thermal contact | Implement active temperature stabilization, reduce sampling density |

| Systematic peak shifts | Uncontrolled sample temperature drift | Verify temperature calibration, monitor with reference standard | Incorporate internal temperature probe, use thermostated sample holders |

| Increased spectral noise | Temperature-induced refractive index fluctuations | Increase signal averaging, isolate from drafts | Install acoustic enclosures, use temperature-regulated purge gas |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Two-Line Thermometry for Temperature Validation

Spectroscopic temperature measurement using oxygen absorption thermometry provides exceptional precision for validation studies. This methodology exploits the temperature-dependent intensity ratio of two oxygen absorption lines in the 762 nm band, previously applied for measurements of high temperatures in flames but adaptable to ambient conditions [4].

Protocol:

- Utilize distributed feedback lasers targeting two specific oxygen absorption lines within the 762 nm band.

- Direct the laser beam along the sample measurement path to ensure spatial overlap with spectroscopic sampling.

- Precisely measure absorption intensities at both wavelengths simultaneously.

- Calculate temperature using the established relationship between the line strength ratio and thermodynamic temperature.

- Achievable precision: 22 mK RMS noise (7.5 × 10⁻⁵ relative uncertainty) at 293 K with 60-second integration time [4].

This approach provides exceptional spatial and temporal alignment between temperature measurement and spectral acquisition, critical for validating thermal conditions during sensitive experiments.

Temperature-Dependent Spectral Acquisition Protocol

For systematic characterization of thermal effects, implement this standardized acquisition workflow:

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare samples with consistent morphology and packing density to minimize thermal contact variations.

- For solution studies, employ degassed solvents to prevent bubble formation during temperature cycling.

- Utilize sealed sample cells with known, minimal thermal mass.

Data Acquisition:

- Equilibrate samples at each temperature for a minimum of 10 minutes (adjust based on sample thermal mass).

- Monitor stabilization using real-time spectral tracking of a reference peak.

- Acquire spectra with sufficient signal averaging to maintain signal-to-noise ratio >100:1 across all temperatures.

- Include background spectra at each temperature to correct for instrument-specific thermal effects.

- Sequence temperature steps in both ascending and descending order to identify hysteresis effects.

Data Processing:

- Apply consistent baseline correction across all spectra using polynomial fitting or derivative methods.

- Normalize spectra to an internal standard band with minimal temperature dependence.

- Precisely track peak parameters (position, height, width, area) across the temperature series.

- Plot temperature dependencies to quantify thermal coefficients for each vibrational mode.

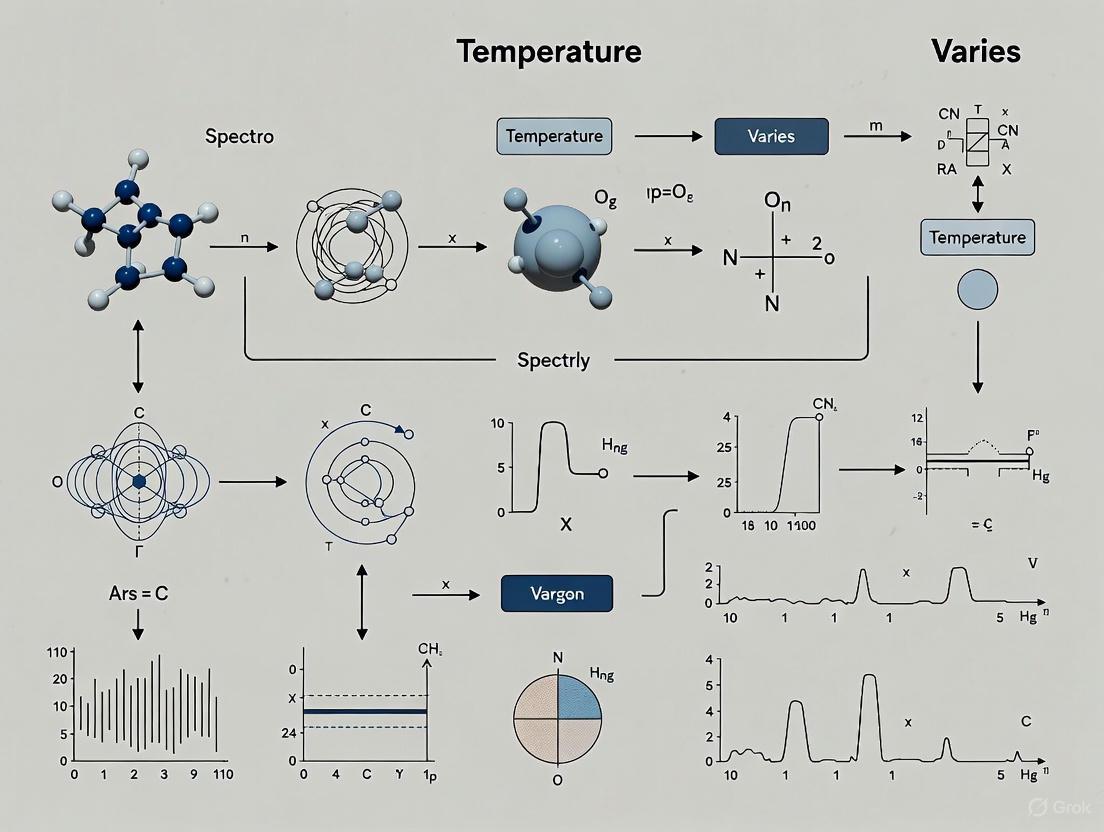

Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Thermal Relationships

Thermal Spectral Interference Diagnostic Framework

Diagram 1: Diagnostic framework for thermal spectral anomalies.

Temperature-Dependent Spectral Acquisition Workflow

Diagram 2: Temperature-dependent spectral acquisition workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Thermal Spectroscopy

| Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Film Reference | Temperature validation standard for IR spectroscopy | Provides well-characterized bands with known thermal response for instrument validation |

| Silicon Wafer | Raman spectroscopy thermal reference | Intense phonon band at ~520 cm⁻¹ with characterized temperature-dependent shift |

| Holmium Oxide Filter | Wavelength calibration standard | Critical for verifying instrumental wavelength accuracy across temperature variations |

| Thermotropic Liquid Crystals | Temperature gradient visualization | Identify thermal inhomogeneities in sample illumination areas |

| Deuterated Solvents | Low-temperature matrix isolation | High-purity solvents for cryogenic studies with minimal interference in regions of interest |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR window material | Low thermal conductivity; requires careful temperature control to prevent cracking |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) | IR window material | Superior thermal properties compared to KBr for variable-temperature studies |

| Inert Perfluorinated Oil | Thermal contact medium | Improves heat transfer between sample and temperature-controlled stage |

FAQ: Addressing Common Thermal Interference Questions

Q1: At what temperature threshold do thermal effects typically become significant in vibrational spectroscopy? Thermal effects manifest progressively rather than at a specific threshold. Generally, temperature variations exceeding ±1°C from standard conditions become detectable in high-resolution instruments, while changes beyond ±5°C often produce analytically significant band shifts and broadening. However, this depends strongly on the specific molecular system and instrumentation. Systems with strong hydrogen bonding or conformational flexibility may exhibit pronounced thermal effects even with ±0.5°C variations [2].

Q2: Can computational methods fully correct for temperature-induced spectral changes? While computational approaches like Fourier self-deconvolution and second derivative spectroscopy can mitigate some thermal effects, they cannot fully reconstruct information lost to severe thermal interference. These methods work best when applied to minimally compromised data. The most effective strategy remains prevention through rigorous experimental temperature control, with computational correction serving as a supplementary approach rather than a complete solution [3].

Q3: How does thermal interference differ between benchtop and portable spectroscopic instruments? Portable instruments generally face greater thermal challenges due to smaller thermal mass, less effective insulation, and greater exposure to ambient fluctuations. Benchtop systems typically incorporate better temperature stabilization of critical components like detectors and sources. However, both systems benefit from the same fundamental principles of temperature control, adequate equilibration time, and appropriate reference standards [1].

Q4: What is the most overlooked aspect of temperature management in spectroscopic experiments? The thermal equilibration time represents the most frequently underestimated factor. Researchers often proceed with measurements before the entire sample-instrument system has reached stable thermal conditions. This is particularly critical for solid samples where thermal conductivity is poor, and temperature gradients can persist long after the external sensor indicates stability. Implementing real-time spectral monitoring of a reference peak provides the most reliable indication of true thermal equilibrium [1] [3].

Q5: Are certain spectroscopic techniques more susceptible to thermal interference than others? Yes, techniques with higher spectral resolution, such as FTIR and Raman spectroscopy, generally show greater susceptibility to thermally-induced band shifts and broadening. Conversely, techniques with inherently broader features, like UV-Vis spectroscopy, may be less affected. However, quantitative applications in any technique can be compromised by temperature variations affecting peak intensities and baselines. NMR spectroscopy represents a special case where temperature effects influence both chemical shifts and relaxation mechanisms [1].

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Temperature-Induced Spectral Shifts and Poor Reproducibility

Problem: Measurements show poor repeatability, with drifting baselines, shifted absorption maxima, or broadened spectral bands, making quantitative analysis unreliable.

Underlying Cause: Temperature variations affect spectroscopic measurements by altering molecular dynamics and energy state populations according to the Boltzmann distribution. Higher temperatures increase molecular motion, leading to Doppler and collisional broadening of spectral lines [5]. The probability of molecules occupying higher energy states increases with temperature, fundamentally changing the observed spectroscopic signatures [6].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Drifting baseline/unstable readings | Instrument lamp not stabilized; environmental temperature fluctuations | Allow spectrometer to warm up for 30+ minutes; operate in temperature-controlled lab (15-35°C) [7] [8] [9]. |

| Shifted absorption maxima | Sample temperature differs from calibration temperature | Implement active temperature control for samples; use temperature-controlled cuvette holders [6]. |

| Broadened spectral peaks | Increased molecular motion and collision frequency at higher temperatures | Pre-equilibrate samples to controlled temperature before measurement; consider cryogenic cooling for high-resolution studies [5]. |

| Inconsistent results between replicates | Sample evaporating or reacting during measurement; cuvette orientation inconsistency | Use sealed cuvettes for volatile solvents; always place cuvette in same orientation; minimize time between replicates [7]. |

| Negative absorbance readings | Blank solution measured at different temperature than sample | Ensure blank and sample are at identical temperature; use same cuvette for both blank and sample measurements [7]. |

Preventive Measures:

- Maintain consistent laboratory temperature and minimize drafts

- Implement regular instrument calibration at operating temperature

- Allow sufficient warm-up time for instrumentation (minimum 5-30 minutes depending on instrument) [8] [7]

- Use temperature monitoring and control systems for critical quantitative work

Guide 2: Managing Bilinearity in Multivariate Spectral Analysis

Problem: When applying chemometric models like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to spectral data, unexpected non-additive interactions between variables create complex, difficult-to-interpret patterns that reduce model accuracy.

Underlying Cause: Bilinearity describes a mathematical property where a function is linear in each of its arguments separately. In spectroscopy, this manifests as multiplicative interactions between row and column effects in data matrices, represented as ( x{ij} = m + ai + bj + ui \times vj ), where the additive effects are (ai, bj) and multiplicative effects are (ui, v_j) [10]. This creates characteristic crossing patterns in profile plots instead of parallel lines seen in purely additive data [10].

Diagnosis and Solutions:

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-parallel lines in profile plots | Multiplicative interactions between sample and environmental variables | Apply Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to estimate and separate multiplicative effects [10]. |

| Clustering artifacts in PCA scores | Temperature-induced scaling of spectral features across samples | Standardize data using median instead of mean to reduce outlier effects on bilinear patterns [10]. |

| Model performs poorly on new batches | Unaccounted bilinear interactions between composition and instrument conditions | Include bilinear terms explicitly in chemometric models or use algorithms designed for multiplicative interactions. |

| Inconsistent growth rates in time series | Different components responding non-uniformly to environmental changes | Interpret bilinearity as growth rate modifiers: ( \text{ratio} = \exp(b(yr2)-b(yr1)) \times \exp(u(cnt)) ) [10]. |

Experimental Workflow for Bilinear Analysis:

- Collect spectral data under controlled temperature conditions

- Create standardized profile plots to visualize row and column effects

- Apply SVD to estimate multiplicative components

- Use median polishing for robust standardization when outliers are present

- Incorporate bilinear terms explicitly in multivariate models

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why does temperature significantly affect my NIR predictions for hydroxyl values in polyols, and how much error should I expect per degree Celsius?

Temperature alters the Boltzmann distribution of molecular energy states and affects hydrogen bonding interactions in polyols. For hydroxyl value determination, each 1°C change introduces approximately 0.05 mg KOH/g absolute error, which corresponds to about 0.20% relative error. A deviation of just 2°C can cause errors exceeding 1% in your predictions [6].

Q2: My FTIR spectra show variability between instruments even with the same experimental adhesives. Is this normal, and how can I improve reproducibility?

Yes, inter-instrument variability is a recognized challenge in FTIR spectroscopy. Studies show that different instruments introduce spectral variability due to differences in resolution, signal-to-noise ratio, and analytical configuration [11]. To improve reproducibility:

- Develop instrument-specific calibration protocols

- Apply consistent spectral processing workflows

- Use robust chemometric approaches like PCA with standardized preprocessing

- Create tailored reference libraries for your specific instrument [11]

Q3: What is the optimal operating temperature range for Ocean Optics and Vernier spectrometers, and why is warming up important?

Most benchtop spectrometers specify operating temperatures between 15°C to 35°C [8] [9]. Warming up for at least 5-30 minutes is crucial because it stabilizes the light source (tungsten/deuterium lamps) and detector components, reducing baseline drift and ensuring photometric accuracy. Without proper warm-up, you may experience unstable readings and calibration drift [7] [8].

Q4: How can I distinguish temperature effects from other sources of spectral error like dirty windows or poor probe contact?

Temperature effects typically manifest as systematic shifts in peak positions and gradual baseline changes, while other issues cause more abrupt problems:

- Dirty windows: Cause gradual calibration drift and poor analysis readings [12]

- Poor probe contact: Creates loud sparking sounds, bright light leakage, and potentially dangerous electrical discharge [12]

- Contaminated argon: Results in white, milky burns and inconsistent/unstable results [12]

- Temperature effects: Show predictable, quantifiable shifts in peak positions and intensities [5] [6]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Temperature Effects in NIR Spectroscopy

Objective: Systematically measure how temperature variations affect prediction accuracy for chemical parameters in liquid samples.

Materials:

- Temperature-controlled NIR spectrometer (e.g., OMNIS NIR Analyzer)

- Standard glass vials (8 mm pathlength)

- Temperature calibration standards

- Polyol samples or other target analytes

Methodology:

- Cool sample to 25°C using instrument temperature control and hold for 300 seconds

- Heat sample to target temperature (e.g., 26°C) and initiate measurement

- Perform triple measurements at each temperature point across studied range (e.g., 26-38°C)

- For each temperature, calculate repeatability error from replicate measurements

- Analyze changes in prediction values versus temperature using linear regression

- Calculate absolute and relative errors per degree Celsius for each parameter [6]

Data Analysis:

- Plot prediction values against temperature to identify trends

- Calculate repeatability error: ( \text{Error} = \frac{\text{Standard Deviation}}{\text{Mean}} \times 100\% )

- Determine temperature coefficient: ( \text{Coefficient} = \frac{\Delta \text{Prediction}}{\Delta \text{Temperature}} )

Protocol 2: Assessing Bilinearity in Spectral Data Sets

Objective: Identify and quantify bilinear patterns in multivariate spectral data to improve chemometric model accuracy.

Materials:

- Spectral data set with multiple samples and variables

- Statistical software with SVD capability (e.g., R, Python)

- Profile plotting functionality

Methodology:

- Arrange data in matrix form with rows representing samples and columns representing spectral features

- Create raw profile plots to visualize initial patterns

- Fit additive model: ( x{ij} = m + ai + bj ) and calculate residuals: ( r{ij} = x{ij} - m - ai - b_j )

- Apply Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) to residuals to estimate multiplicative effects: ( r{ij} = ui \times v_j )

- Create standardized profile plot with columns sorted by multiplicative effect ( v_j )

- For outlier-resistant analysis, apply median polishing instead of mean-centered standardization [10]

Interpretation:

- Parallel lines in standardized profile plots indicate additivity

- Diverging or converging lines indicate bilinearity

- The slope of lines corresponds to multiplicative effect ( u_i )

- Spatial arrangement along x-axis corresponds to column effect ( v_j )

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Temperature Variation on NIR Predictions

| Application | Parameter | Absolute Change per °C | Relative Error per °C | Concentration Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyol | Hydroxyl Value | 0.05 mg KOH/g | 0.20% | 24.91 mg KOH/g |

| Methoxypropanol | Moisture Content | Data Specific | Data Specific | Various |

| Diesel | Cetane Index | Data Specific | Data Specific | Various |

| Diesel | Viscosity | Data Specific | Data Specific | Various |

Source: Adapted from Metrohm NIRS temperature control studies [6]

Table 2: Error Budget Analysis for Polyol Hydroxyl Value Determination

| Error Source | Absolute Error (mg KOH/g) | Relative Error (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measurement Repeatability | 0.05 | 0.20% | Based on triple measurements at constant temperature |

| Temperature Variation (±1°C) | 0.05 | 0.20% | Per degree Celsius change |

| Temperature Variation (±2°C) | 0.10 | 0.40% | Per two degrees Celsius change |

| Total Error (±2°C) | ~0.15 | ~0.60% | Combined repeatability and temperature effects |

Source: Adapted from Metrohm NIRS temperature control studies [6]

Table 3: Spectrometer Operating Specifications and Temperature Ranges

| Instrument Type | Operating Temperature | Warm-up Time | Wavelength Accuracy | Photometric Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ocean Optics Vernier | 15-35°C | 5 minutes minimum | ±2 nm | ±5.0% |

| Red Tide UV-VIS | 15-35°C | 5 minutes minimum | ±1.5 nm | ±4.0% |

| SpectroVis Plus | 15-35°C | 5 minutes minimum | ±3.0 nm (650 nm) | ±13.0% |

Source: Compiled from manufacturer specifications [8] [9]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature-Controlled Cuvette Holder | Maintains consistent sample temperature during measurement | Critical for quantitative work; prefer active monitoring over passive heating |

| NIST-Traceable Temperature Standards | Verifies temperature accuracy of measurement systems | Required for validating temperature control methods |

| Quartz Cuvettes | UV-transparent sample containers for UV-VIS spectroscopy | Essential for measurements below 340 nm; avoid plastic/glass for UV work |

| Matched Cuvette Pairs | Ensure identical optical path for blank and sample | Eliminates cuvette-specific artifacts in differential measurements |

| Holmium Oxide Wavelength Standard | Verifies wavelength accuracy across temperature range | NIST-traceable standard for instrument validation [8] |

| Nickel Sulfate Photometric Standard | Validates photometric accuracy | Used for absorbance/transmittance accuracy verification [8] |

| Desiccant Packs | Controls humidity in instrument compartments | Prevents moisture-related drift in sensitive optics |

Workflow Visualization

Temperature Control Experimental Setup

Bilinear Data Analysis Pathway

Temperature Effect Mechanisms

This technical support guide addresses a critical challenge in spectroscopic analysis: mitigating the detrimental effects of temperature variations on measurement accuracy. Temperature fluctuations introduce significant errors in UV-Vis, Infrared, and Emission spectroscopy by altering molecular energy states, shifting absorption maxima, and broadening spectral lines. This resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with targeted troubleshooting methodologies and experimental protocols to control for these variables, ensuring data integrity and reproducibility within rigorous scientific research frameworks.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Temperature-Induced Spectral Shifts in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

Problem Statement: Users report inconsistent UV-Vis absorption maxima and intensity readings for the same sample across different days, suspected to be caused by laboratory temperature fluctuations.

Explanation: Temperature changes directly affect molecular dynamics and solvent-solute interactions. Increased temperature enhances molecular motion, leading to broader spectral lines due to the Doppler effect and collisional broadening. It can also shift the position of absorption peaks. For π to π* transitions, a polar solvent can decrease the transition energy, causing a bathochromic (red) shift. For n to π* transitions, hydrogen bonding with polar solvents stabilizes the ground state, leading to a hypsochromic (blue) shift with increasing temperature and solvent polarity [5] [13].

Solution: Implement a dual approach of environmental control and data compensation.

- Step 1: Environmental Stabilization

- Conduct all experiments in a temperature-controlled laboratory environment.

- Allow samples and solvents to equilibrate to the instrument's temperature for at least 15 minutes before analysis.

- Use temperature-controlled cuvette holders whenever possible.

- Step 2: Data Compensation via Multi-Source Fusion

- Methodology: Fuse spectral data with real-time temperature sensor readings using a weighted superposition algorithm [14].

- Procedure:

- Collect UV-Vis spectra (e.g., 193-1120 nm) of your samples while simultaneously recording the solution temperature with a calibrated probe.

- Establish a calibration model that incorporates both the spectral features (e.g., absorbance at key wavelengths) and the measured temperature.

- Apply this model to future predictions to compensate for the temperature variation, effectively normalizing the data to a reference temperature.

Expected Outcome: Significant improvement in the reproducibility of absorption maxima and quantitative intensity measurements, leading to a more robust and reliable analytical method.

Guide 2: Managing Environmental Interference in Infrared Gas Detection

Problem Statement: An uncooled infrared spectrometer used for open-space gas leak detection shows declining accuracy and sensitivity with changes in ambient temperature, leading to poor quantification.

Explanation: Uncooled infrared detectors are highly susceptible to environmental temperature changes, which cause drift in the focal plane array (FPA) response. This drift introduces errors in the measured radiance, corrupting the gas concentration retrieval based on infrared absorption fingerprints [15].

Solution: Implement a shutterless temperature compensation model that accounts for the entire optical system.

- Step 1: System Characterization

- Calibrate the instrument's response across its full operational temperature range (e.g., 0 °C to 80 °C).

- Step 2: Integrated Temperature Correction

- Methodology: Apply a multi-point temperature correction model that integrates readings from sensors monitoring the camera casing, FPA, internal optics, and ambient air [15].

- Procedure:

- Model the relationship between these temperature points and the FPA's radiative output.

- Use this model in real-time to correct the raw radiance signal before it is processed for gas concentration.

- This approach moves beyond simple FPA temperature stabilization, correcting for signal interference caused by the warming of all critical components.

Expected Outcome: Restoration of detection sensitivity and accuracy. Validation tests show temperature prediction errors can be maintained within ±0.96°C, enhancing detection limits for gases like SF6 and ammonia by up to 67% [15].

Guide 3: Validating Temperature Accuracy in Emission Spectroscopy

Problem Statement: A researcher needs to validate the temperature accuracy of an FTIR emission spectrometer for characterizing a high-temperature process, such as combustion.

Explanation: Emission spectroscopy infers temperature from the line-integrated emission spectra of a hot gas. Accurate temperature retrieval depends on the instrument's calibration and the accuracy of the spectroscopic database used for fitting. Without a traceable standard, uncertainties can be as large as 2-5% [16].

Solution: Validate the system using a portable standard flame with a traceably known temperature.

- Step 1: Utilize a Standard Flame Artifact

- Employ a calibrated flat-flame burner (e.g., a Hencken burner) that produces a stable, uniform post-flame region with a known temperature profile [16].

- Step 2: Comparative Measurement

- Methodology: Use Rayleigh scattering thermometry, which is directly traceable to the International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90), to calibrate the standard flame temperature with an uncertainty of about 0.5% [16].

- Procedure:

- Direct the FTIR emission spectrometer to measure the line-integrated emission spectrum from the post-flame region of the standard flame.

- Retrieve the temperature from the measured spectrum using your standard data processing algorithms.

- Compare the retrieved temperature from the FTIR system to the known Rayleigh scattering temperature of the standard flame.

Expected Outcome: Quantification of the FTIR system's measurement bias and uncertainty. Successful validation is achieved when the agreement between the methods is within the combined stated uncertainties (e.g., ~1%) [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is temperature control so critical in spectroscopic experiments, even for simple UV-Vis assays? Temperature directly impacts molecular dynamics and energy states. According to the Boltzmann distribution, temperature governs the population of molecular energy states. Changes in temperature can alter molecular interaction energies, cause band broadening, and shift absorption maxima. These effects jeopardize the accuracy and reproducibility of both qualitative and quantitative analyses, making temperature control a foundational requirement for reliable spectroscopy [5].

FAQ 2: What are the most common temperature control technologies for sensitive spectroscopic samples? The choice of technology depends on the required temperature range.

- Cryogenic Cooling: Uses liquid nitrogen or helium to achieve very low temperatures (4 K - 300 K), reducing molecular motion to enhance spectral resolution.

- High-Temperature Heating: Employs resistive heating elements for studies up to 2000 K.

- Precision Temperature Control Systems: Utilize advanced thermometry and PID control algorithms to maintain sub-degree stability within a moderate range, often integrated directly with spectroscopic cells [17].

FAQ 3: How can I calibrate my temperature control system to ensure accurate measurements? Calibration should be performed using certified reference materials.

- Use thermocouple or RTD calibration standards that are traceable to national standards.

- Perform regular calibration checks against a known reference point, such as an ice bath (0°C) or a certified thermometer.

- For in-situ validation, use materials with known phase transitions at specific temperatures [17].

FAQ 4: We cannot control our lab's ambient temperature. What are the best practices for data analysis under these varying conditions? When environmental control is not feasible, proactive data management is key.

- Acquire Calibration Data at Multiple Temperatures: Build a model that explicitly accounts for the temperature dependence of your spectral signals.

- Use Temperature-Dependent Models: Incorporate terms for temperature drift or use algorithms like two-dimensional regression analysis to compensate for its effect during quantitative analysis [18].

- Record Temperature Concurrently: Always log the ambient and/or sample temperature with each spectral measurement, allowing for post-hoc data correction [14].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Data Fusion for Temperature Compensation in UV-Vis COD Detection

This protocol is adapted from research on detecting Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) in water, where compensating for environmental factors significantly improved accuracy [14].

1. Scope and Application: This method is used to improve the accuracy of UV-Vis spectroscopic measurements for quantitative analysis (like COD detection) by compensating for the interfering effects of temperature, pH, and conductivity.

2. Experimental Workflow:

The following diagram illustrates the integrated steps for sample preparation, data collection, and model building.

3. Key Materials and Reagents:

- UV-Vis Spectrometer: Agilent Cary 60 or equivalent, with a 10 mm path length quartz cuvette [14].

- Multi-Parameter Meter: For simultaneous measurement of pH, temperature, and conductivity (e.g., Hach SensION+MM156) [14].

- Reference Standards: COD stock solution (1000 mg/L) and distilled water for dilution [14].

- Digestion Apparatus: For standard method validation (e.g., Hach DRB200 and DR3900 for COD testing) [14].

4. Data Analysis:

- Fuse the spectral data (e.g., absorbance at feature wavelengths) with the measured environmental factors into a single dataset.

- Use multivariate regression techniques like Partial Least Squares (PLS) to build a prediction model that relates the fused data to the standard assay values.

- Validate the model with an independent prediction set. The compensated model achieved a determination coefficient (R²) of 0.9602 and a root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP) of 3.52 for COD, a significant improvement over the non-compensated model [14].

Protocol 2: Standard Flame Validation for Emission Spectrometers

This protocol outlines the use of a traceable standard flame to validate the temperature reading of an FTIR emission spectrometer [16].

1. Scope and Application: This procedure is designed to validate and calibrate optical diagnostic systems, particularly FTIR emission spectrometers, used for measuring high temperatures in combustion environments.

2. Experimental Workflow:

The core of this protocol is a comparative measurement between the system under test and a traceable standard.

3. Key Materials and Reagents:

- Standard Flame Burner: A flat-flame burner (e.g., Hencken diffusion burner) that provides a uniform temperature field [16].

- Calibrated Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs): For precise control of fuel and oxidizer flow rates (e.g., Bronkhorst MFCs with <1% uncertainty) [16].

- Traceable Thermometry System: A Rayleigh scattering thermometry system calibrated and traceable to ITS-90 [16].

- Gases: High-purity fuel (e.g., Propane, 95%) and dry air [16].

4. Data Analysis:

- The known temperature of the standard flame (T_ref) is established via Rayleigh scattering.

- The FTIR system measures the emission spectrum and retrieves a temperature (T_measured).

- The validation is successful if the difference |Tmeasured - Tref| is within the combined expanded uncertainty of both measurement systems (e.g., ~1%) [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for implementing the temperature compensation and validation methods described in this guide.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Hencken Flat-Flame Burner | Provides a stable, uniform high-temperature source for validating emission spectrometers. | Produces a two-dimensional array of diffusion flamelets; temperature calibrated via Rayleigh scattering [16]. |

| Precision Mass Flow Controllers (MFCs) | Deliver exact flow rates of fuel and oxidizer to maintain stable flame and temperature conditions. | Calibration uncertainty <1% with target gas (e.g., propane); crucial for flame reproducibility [16]. |

| COD Standard Solution | Used as a known standard for developing and validating UV-Vis calibration models with environmental compensation. | 1000 mg/L stock solution; diluted with distilled water to create calibration series [14]. |

| Multi-Parameter Portable Meter | Simultaneously measures key environmental interferants (pH, Temperature, Conductivity) during spectral acquisition. | Enables data fusion for comprehensive environmental compensation in UV-Vis analysis [14]. |

| Temperature-Controlled Cuvette Holder | Maintains sample at a constant temperature during UV-Vis analysis to minimize thermal drift. | Integrates with spectrometer; often uses Peltier elements for heating/cooling [17] [5]. |

Table 1: Quantified Impact of Temperature Compensation on Analytical Performance

This table summarizes the performance improvements achieved by applying specific temperature compensation methods across different spectroscopic techniques, as reported in the literature.

| Spectroscopy Technique | Compensation Method | Key Performance Metric | Before Compensation | After Compensation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis (for COD) | Data Fusion (Spectra + Env. Factors) [14] | R² (Prediction) | Not Reported | 0.9602 |

| RMSEP | Not Reported | 3.52 | ||

| Uncooled IR (Gas Imaging) | Multi-point Temp. Correction Model [15] | Temp. Prediction Error | Not Reported | < ±0.96°C |

| SF6 Detection Limit | Baseline | +50% Improvement | ||

| NH3 Detection Limit | Baseline | +67% Improvement | ||

| Near Infrared (NIR) | 2D Regression Analysis [18] | Coefficient of Variation (CV) | Baseline | 2-Fold Decrease |

Table 2: Characterized Standard Flame for Emission Spectroscopy Validation

This table outlines the specifications of a portable standard flame system used for the traceable calibration of optical temperature measurement systems [16].

| Parameter | Specification / Value |

|---|---|

| Burner Type | Hencken Flat-Flame Diffusion Burner |

| Fuels Used | Propane (95% purity), H2/Air |

| Calibration Method | Rayleigh Scattering Thermometry |

| Temperature Uncertainty (k=1) | 0.5 % of reading |

| Key Feature | Traceability to International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90) |

| Accessible Temperature Range | 1000 °C to 1900 °C (via equivalence ratio adjustment) |

Advanced Techniques for Temperature Compensation and Robust Measurement

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Temperature-Induced Spectral Drift

Problem: Measurement inaccuracies and instability in spectroscopic readings due to laboratory temperature fluctuations.

Explanation: Temperature variations directly impact the physical properties of samples and the electronic components of the spectrometer, leading to signal drift and spectral shifts. Precision temperature control is essential for achieving reliable and reproducible results [17].

Solution: A dual approach of instrumental control and post-processing correction.

- Step 1: Implement Precision Temperature Control. Utilize modern temperature control systems, such as cryogenic cooling or high-temperature heating solutions, to maintain sample stability. These systems use advanced thermometry and Proportional-Integral-Derivative (PID) control algorithms to achieve stabilities within a few millikelvin [17].

- Step 2: Calibrate with Certified References. Regularly calibrate your temperature sensor using certified reference materials. Perform this calibration under the same environmental conditions used for sample measurements [17].

- Step 3: Apply Mathematical Correction. Model and correct for residual temperature variations using the governing equation for temperature dynamics: ( \frac{dT}{dt} = \frac{Q}{C} - \frac{T - T{\text{ambient}}}{RC} ) where (T) is sample temperature, (Q) is heat input, (C) is heat capacity, (R) is thermal resistance, and (T{\text{ambient}}) is ambient temperature [17].

Prevention Tips:

- Allow the spectrometer and sample to equilibrate to the set temperature before starting measurements.

- Use spectroscopic cells made from materials with high thermal conductivity (e.g., sapphire) to minimize internal thermal gradients [17].

- Implement instrument housing or environmental controls to minimize rapid ambient temperature changes in the laboratory.

Guide 2: Correcting Phase Errors in Complex Spectral Data

Problem: Distorted spectral line shapes and baseline artifacts in techniques like Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI) or Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT), often caused by motion or instrumental instability.

Explanation: Phase errors can arise from motion-induced field distortions, eddy currents, or environmental perturbations. These errors manifest as a mixture of absorption and dispersion line shapes, complicating metabolite quantification and image clarity [19] [20] [21].

Solution: Employ retrospective computational phase correction.

- Step 1: Acquire a Reference Signal. Use the Interleaved Reference Scan (IRS) method. This involves acquiring a non-water-suppressed reference signal (in MRSI) or measuring phase from a stable reference layer (in OCT) immediately after or before each data acquisition repetition [20] [21].

- Step 2: Estimate the Phase Error. Calculate the phase difference between adjacent scans. For a robust 2D correction, compute the vectorial gradient field of the bulk phase error across the scanning plane [21].

- Step 3: Apply the Phase Correction. Correct the actual spectral signal on a point-by-point basis using the phase information from the reference signal. This corrects for both zero-order and higher-order phase distortions, ensuring pure absorption line shapes [20] [21].

Prevention Tips:

- For in-vivo studies, use prospective motion correction with optical tracking systems to update the scanner geometry in real-time and minimize motion-induced phase errors [20].

- Improve phase stability by increasing acquisition speed where possible, as this reduces the time window for motion and environmental drift [21].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between accuracy and precision in the context of spectroscopic calibration? Accuracy (trueness) measures how close your measured value is to the expected value, while precision (repeatability) measures how consistent your results are under unchanged conditions. High-quality calibration requires both. Systematic errors affect accuracy, whereas random errors affect precision [22].

Q2: How can I correct for spectral errors when measuring under different light sources? Spectral error occurs because a sensor's response does not perfectly match the ideal quantum response. To correct for it, multiply your measured value by a manufacturer-provided correction factor (CF) specific to your light source. For example: Corrected Value = Measured Value (µmol m⁻² s⁻¹) × CF [23].

Q3: What are the best practices for maintaining temperature stability during long spectroscopic measurements?

- Use a precision temperature control system with PID algorithms.

- Design experiments to minimize thermal gradients by using optimized sample cells and heat sinks.

- Isolate the experimental setup from environmental disturbances like air conditioning vents or direct sunlight [17].

Q4: My spectra have a distorted baseline and poor line shape after in-vivo MRSI. What processing steps can help? Implement an automated processing pipeline that includes:

- Multiscale Analysis: Improving the signal-to-noise ratio and automating peak identification by processing data at multiple spatial resolutions.

- Peak-Specific Phase Correction: Isolating segments containing key metabolites (e.g., NAA, Choline, Creatine) and performing phase correction on each segment individually to simplify the problem and improve fitting robustness [19].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Temperature Calibration for a Spectroscopic System

This protocol details the steps for calibrating and validating a temperature control system on a spectrometer.

1. Objective: To ensure the temperature reported by the spectrometer's sensor accurately reflects the actual temperature of the sample.

2. Materials:

- Spectrometer with integrated temperature control (e.g., cryogenic cooler or resistive heater).

- Certified external temperature probe (e.g., thermocouple or RTD calibration standard).

- Standard reference sample.

- Data acquisition software.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Setup. Place the standard reference sample and the certified external temperature probe in the spectroscopic cell as close to the measurement spot as possible.

- Step 2: Data Collection. Set the spectrometer to a series of target temperatures (e.g., 280K, 300K, 320K). At each set point, allow the system to stabilize, then record both the spectrometer's internal temperature reading and the reading from the certified external probe.

- Step 3: Correlation. Create a calibration curve by plotting the internal sensor readings against the certified probe readings. Fit a regression line to this data.

- Step 4: Validation. Use the derived calibration function to correct the internal sensor readings. Run a validation experiment at a new temperature point not used in the calibration to confirm accuracy.

4. Data Analysis: The calibration data can be summarized in a table for easy reference:

Table 1: Example Temperature Calibration Data

| Certified Probe Reading (K) | Internal Sensor Reading (K) | Correction Offset (K) |

|---|---|---|

| 280.0 | 279.5 | +0.5 |

| 300.0 | 300.8 | -0.8 |

| 320.0 | 319.2 | +0.8 |

Protocol 2: Phase Error Correction in MRSI Data

This protocol outlines a method for retrospective phase correction in multi-slice MRSI data of the human brain using a multiscale approach [19].

1. Objective: To automatically correct for phase distortions and poor line shapes in MRSI data to enable robust metabolite quantification.

2. Materials:

- Reconstructed multi-slice MRSI data set (e.g., 64x64x1024 matrix).

- Computing environment (e.g., MATLAB).

- Processing scripts for multiscale analysis and curve fitting.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Multiscale Pyramid Creation. Create a three-level data pyramid from the original MRSI data (

Level 1: 64x64). GenerateLevel 2 (32x32)by averaging each 2x2 block of voxels from Level 1. GenerateLevel 3 (16x16)by averaging 2x2 blocks from Level 2. This improves SNR at coarser scales [19]. - Step 2: Coarse-to-Fine Peak Identification. At the top level (Level 3, best SNR), automatically identify the frequency and linewidth of the N-acetylaspartate (NAA) peak. Use this as prior knowledge to guide the identification of the same peak at the next, finer scale (Level 2). Repeat the process down to the original resolution (Level 1) [19].

- Step 3: Spectral Segmentation and Phase Correction. Extract spectral segments containing only the metabolites of interest (e.g., an NAA segment and a combined Choline/Creatine segment). For each segment in every voxel, perform an automatic phase correction by minimizing the function: ( S = \left| \sum (\text{Imaginary part}) \right| + \left| W / \sum (\text{Real part}) \right| ) where ( W ) is a weighting factor to balance contributions from the real and imaginary parts. Use the corrected real part for final quantification [19].

- Step 4: Metabolite Quantification. Fit a Gaussian line shape with a linear baseline to each corrected peak in the segmented spectra. Calculate the area under the peak to generate metabolite concentration maps [19].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps of this protocol:

Multiscale MRSI phase correction and quantification workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibrate temperature sensors and verify spectroscopic instrument response; essential for establishing measurement trueness [17] [22]. |

| PID Temperature Controller | Provides high-stability temperature control for samples by using a feedback algorithm to minimize deviations from the setpoint [17]. |

| Cryogenic Cooling System | Achieves and maintains very low temperatures (e.g., 4K - 300K) for studying low-temperature phenomena in materials [17]. |

| ATR-FTIR Accessory | Allows for direct analysis of solids, liquids, and pastes with minimal sample preparation, simplifying temperature-controlled studies [24]. |

| Optical Tracking System | Provides real-time, external motion tracking for prospective motion correction in in-vivo spectroscopy [20]. |

| Sapphire Spectroscopic Cells | Provide excellent thermal conductivity and durability for high-temperature or cryogenic experiments [17]. |

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Hub

This section provides targeted solutions for common challenges encountered when applying Non-Negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) to manage temperature-induced spectral variations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using NMF over other matrix factorization techniques like PCA for spectroscopic data? NMF's constraint that all matrices must contain only non-negative elements makes it ideal for spectroscopic data, which is inherently non-negative. This results in a parts-based representation that is often more intuitive and interpretable than the subtractive, holistic components produced by Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [25] [26]. In the context of temperature compensation, this allows NMF to decompose spectral data into more physically meaningful basis spectra and coefficients.

Q2: My NMF model for temperature compensation is not generalizing well to new samples. What could be wrong? This is often a sign of overfitting or the model learning temperature-specific noise instead of the underlying physicochemical relationship. To address this:

- Regularize the model: Incorporate graph regularization or manifold learning if you have prior knowledge about the smoothness of the temperature-dependent spectral manifold [27] [26].

- Validate implicitly: Research indicates that sometimes the best approach is to implicitly include temperature in the calibration model by designing experiments that capture temperature variation, rather than building an explicit, complex temperature model [28].

- Increase data diversity: Ensure your training set includes a sufficient number of samples measured across the entire expected temperature range.

Q3: How do I choose the correct factorization rank (k) for my NMF model?

Selecting the rank k is critical, as it determines the number of latent factors (e.g., fundamental spectral components) in the model.

- Use model selection: Employ algorithms like consensus clustering, which assess the stability of the factorization across multiple runs for different ranks [25].

- Leverage prior knowledge: The rank can sometimes be informed by the number of known independent physical processes or chemical components affected by temperature in your sample.

- Cross-validation: Use cross-validation on your end goal (e.g., prediction accuracy of a chemical property) to select the rank that provides the best and most stable performance.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Slow or Non-Convergence | Inappropriate initialization; suboptimal algorithm [27] [26]. | Use non-negative double singular value decomposition (nndsvd) for initialization; employ alternating direction method (ADM) or improved projected gradient methods [27]. |

| Poor Reconstruction Error | Factorization rank (k) is too low; model is too simple [25] [26]. |

Systematically increase the rank k and use a model selection criterion (e.g., AIC, consensus) to find the optimal value. |

| Model Sensitive to Initial Conditions | NMF objective function is non-convex, leading to local minima [29] [26]. | Run the algorithm multiple times with different random initializations and select the result with the lowest objective function value. |

| Failure to Correct for Temperature | Model is not capturing the non-linear, temperature-dependent manifold structure of the data. | Apply graph-regularized NMF (GNMF) to preserve the intrinsic geometry of the data manifold across temperatures [27] [26]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

This section details a specific methodology for developing a temperature-compensated spectroscopic model using NMF.

Detailed Protocol: Two-Dimensional Regression with NMF for Temperature Compensation

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to correct Near-Infrared (NIR) spectra for temperature effects [18].

1. Objective: To build a robust calibration model that accurately predicts sample properties from spectra, independent of temperature fluctuations in the range of 293-313 K.

2. Experimental Design and Data Collection:

- Prepare a set of calibration samples covering the expected range of chemical compositions.

- Using a NIR spectrophotometer, acquire spectra for each sample at multiple, controlled temperatures (e.g., 293 K, 303 K, 313 K). Ensure a closed cell is used to prevent evaporation [28].

- Record the corresponding output voltage values from the detector and the reference property values (e.g., concentration, density) for all sample-temperature combinations.

3. Data Preprocessing:

- Arrange the collected spectra into a primary data matrix V, where each row is a single spectrum and columns correspond to wavelengths.

- Mean-center or standardize the spectra if necessary.

4. Core NMF Decomposition:

- Apply NMF to decompose the spectral matrix V into two non-negative matrices: W (basis spectra) and H (coefficients).

- V ≈ W * H

- The rank

kof the factorization should be chosen via cross-validation or a model selection algorithm to avoid overfitting [25].

5. Two-Dimensional Regression:

- Construct a temperature matrix T that encodes the temperature conditions for each spectrum.

- Perform a two-dimensional regression (e.g., using PLS) with the NMF coefficient matrix H and the temperature matrix T as independent variables to predict the target property values Y.

- Y = f(H, T)

- This step explicitly integrates temperature information into the predictive model.

6. Model Validation:

- Validate the model using a separate test set of spectra measured at temperatures not used in the calibration.

- Compare the coefficient of variation (C.V.) and prediction error before and after compensation. A successful implementation can decrease the C.V. by 2-fold or more [18].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the experimental protocol for temperature-compensated modeling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational and data resources essential for implementing NMF in spectroscopic research.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RepoDB Dataset [30] | Gold-Standard Data | Provides benchmark drug-disease pairs (approved & failed) to validate computational repositioning methods that may use NMF. |

| UMLS Metathesaurus [30] | Knowledge Base | A source of hand-curated, structured biomedical knowledge (e.g., drug-disease treatment relations) used to build the initial matrix for factorization. |

| SemMedDB [30] | NLP-Derived Database | Provides treatment relations extracted from scientific literature via NLP, serving as another data source for constructing the input matrix. |

| Multiplicative Update Algorithm [29] | Core Algorithm | A standard, simple algorithm for computing NMF. It is parameter-free but can have slow convergence. |

| Alternating Direction Algorithm (ADA) [27] | Advanced Algorithm | A more efficient algorithm for solving NMF that is proven to converge to a stationary point, offering advantages in speed and reliability. |

| Graph Regularization [27] [31] | Modeling Technique | A constraint added to the NMF objective function to incorporate prior knowledge (e.g., drug or target similarity), improving model accuracy and interpretability. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My temperature estimation model has high overall accuracy but performs poorly on specific material types. What should I do? This indicates potential underfitting or biased training data. First, perform error analysis to isolate which material classes have the highest error rates [32]. Ensure your training set has sufficient representative samples for all material types you encounter in production. Implement feature selection techniques like mRMR (Maximum Relevance and Minimum Redundancy) to reduce feature redundancy and improve model generalization [33]. For spectroscopic data, expanding the feature set to include atomic-to-ionization line ratios has shown significant improvements in temperature correlation [34].

Q2: How can I improve model performance when I have limited labeled temperature data for training? Leverage feature engineering to create more informative inputs from existing data. For LIBS data, calculate relative intensity ratios (atomic-to-atomic, ionization-to-ionization, atomic-to-ionization) rather than relying solely on absolute peak intensities [34]. Apply data augmentation techniques and consider using synthetic data generation to create more balanced datasets, particularly for rare temperature ranges [35]. Transfer learning approaches using models pre-trained on related spectroscopic datasets can also help when labeled data is scarce.

Q3: My model works well in validation but deteriorates when deployed for real-time temperature monitoring. What could be wrong? This suggests data drift or domain shift between your training and production environments. For spectroscopic measurements, even minor changes in experimental setup can significantly affect spectra [34]. Implement continuous monitoring to detect distribution shifts in incoming data [35]. Use adaptive model training where the model parameters are periodically updated with new production data. Also verify that preprocessing steps like normalization are correctly applied in the deployment environment [33].

Q4: How do I handle class imbalance in my temperature classification model when certain temperature ranges are rare? Apply SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) to generate synthetic samples for underrepresented temperature ranges [33]. Alternatively, use appropriate evaluation metrics beyond accuracy, such as F1-score or precision-recall curves, which are more informative for imbalanced datasets [36]. Algorithmic approaches include using class weights during training to make the model more sensitive to minority classes.

Q5: What are the most important features for spatial temperature estimation in spectroscopic data? Based on research, spectral line intensity ratios consistently show strong correlation with temperature changes. Specifically, the ratio of ionic to atomic lines (e.g., Zr II 435.974 nm to Zr I 434.789 nm) has demonstrated particularly high correlation (R² = 0.976) with surface temperature [34]. Feature importance analysis using mutual information criteria can help identify the most predictive features for your specific experimental setup.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Generalization Across Different Experimental Setups

| Symptoms | Possible Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| High variance in performance across different days/labs | Environmental factors affecting measurements | Compare feature distributions between setups [37] | Implement robust data normalization [33] |

| Model fails with new material batches | Overfitting to specific sample characteristics | Analyze error patterns by material properties [32] | Expand training diversity; use data augmentation [35] |

| Performance degradation over time | Data drift in spectroscopic measurements | Monitor feature statistics for shifts [35] | Implement adaptive retraining pipeline |

Implementation Example:

Problem: Inaccurate Temperature Predictions in Specific Ranges

| Error Pattern | Root Cause | Verification Method | Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistent errors at temperature extremes | Insufficient training data in these ranges | Analyze dataset distribution by temperature bins | Targeted data collection; SMOTE for balance [33] |

| High variance in high-temperature predictions | Signal-to-noise issues in spectroscopic data | Examine raw spectra quality at different temperatures | Improve feature selection; denoising techniques |

| Systemic bias at transition points | Non-linear relationships not captured by model | Plot residuals vs. temperature | Incorporate non-linear features; try different algorithms |

Experimental Protocol:

- Isolate problematic temperature ranges through error analysis [32]

- Collect additional samples specifically in these ranges

- Engineer temperature-specific features such as specialized spectral ratios [34]

- Validate improvements using cross-validation within targeted ranges

Experimental Protocols for Spatial Temperature Estimation

Protocol 1: Feature Engineering for LIBS-Based Temperature Estimation

This protocol details the methodology for developing effective features from Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) data for temperature estimation, based on published research [34].

Materials Required:

- High-resolution spectrometer (2400 L mm⁻¹ grating or comparable)

- Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (532 nm wavelength)

- Temperature-controlled sample stage

- Reference temperature sensor (pyrometer recommended for high temperatures)

Procedure:

- Data Collection:

- Collect LIBS spectra across your temperature range of interest (e.g., 350-600°C)

- For each temperature, acquire multiple spectra to account for experimental variability

- Maintain consistent laser energy (e.g., 45 mJ per pulse) and timing parameters (e.g., 1 μs gate delay and width)

Feature Extraction:

- Identify prominent atomic and ionic lines in your spectra

- Calculate absolute intensities for each line of interest

- Compute intensity ratios between selected lines:

- Atomic-to-atomic line ratios

- Ionic-to-ionic line ratios

- Atomic-to-ionic line ratios

Feature Evaluation:

- Plot each ratio against reference temperature

- Fit curves to determine correlation strength (R² values)

- Select the ratio with strongest exponential relationship for model development

Validation:

- Reserve a portion of data (≥30%) for validation

- Compare model predictions against reference temperatures

- Calculate performance metrics (MAE, R²) specifically for different temperature ranges

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol 2: Error Analysis Framework for Temperature Estimation Models

Systematic error analysis is essential for diagnosing and improving temperature estimation models [32] [36].

Materials Required:

- Model predictions and ground truth temperature values

- Metadata about experimental conditions

- Data analysis environment (Python/R with appropriate libraries)

Procedure:

- Error Categorization:

- Calculate absolute errors for each prediction

- Categorize errors by temperature range, material type, and experimental conditions

- Create a confusion matrix (for classification) or residual plots (for regression)

Pattern Identification:

- Identify temperature ranges with systematically higher errors

- Check for correlation between error magnitude and specific spectral features

- Analyze whether errors are biased (consistently over- or under-predicting)

Root Cause Analysis:

- For high-error segments, examine raw data quality

- Verify feature distributions differ between high and low error cases

- Check for data leakage or preprocessing issues

Targeted Improvement:

- Based on findings, implement specific fixes:

- If specific temperature ranges perform poorly: collect more data in these ranges

- If certain materials have high errors: add material-specific features

- If noise is problematic: implement better filtering or feature selection

- Based on findings, implement specific fixes:

The error analysis process follows this logical workflow:

Research Reagent Solutions

| Category | Specific Material/Technique | Function in Temperature Estimation | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Zirconium Carbide (ZrC) | High-temperature calibration standard [34] | Suitable for 350-600°C range; polished surfaces recommended |

| Feature Selection | mRMR (Max-Relevance Min-Redundancy) | Identifies informative, non-redundant features [33] | Particularly effective for high-dimensional spectral data |

| Data Balancing | SMOTE | Generates synthetic samples for rare temperature ranges [33] | Improves model performance for imbalanced temperature datasets |

| Model Optimization | Optuna Framework | Automates hyperparameter tuning for temperature models [33] | More efficient than manual tuning for complex spectroscopic models |

| Validation Metrics | MAE, R², F1-Score | Quantifies model performance across temperature ranges [36] [33] | Use multiple metrics for comprehensive evaluation |

Performance Comparison of Temperature Estimation Methods

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data for various approaches to data-driven temperature estimation:

| Method | Best Performance | Key Features | Temperature Range | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LIBS Intensity Ratios | R² = 0.976 (Zr II/Zr I) [34] | Atomic/ionic line ratios | 350-600°C | Material-specific calibration required |

| mRMR + CatBoost | Accuracy: ~90% (intrusion detection) [33] | Feature selection + gradient boosting | Dataset dependent | Requires substantial training data |

| Error Analysis + Optimization | 10-15% error reduction [32] [36] | Systematic error diagnosis | Various ranges | Labor-intensive process |

| SMOTE + Model Tuning | Improved recall for minority classes [33] | Addresses class imbalance | Various ranges | May introduce synthetic artifacts |

Diagnostic Framework for Temperature Model Issues

The following diagram provides a comprehensive troubleshooting workflow for diagnosing common issues with spatial temperature estimation models:

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a hybrid pyrometry approach over a standard two-color method? A hybrid approach leverages the robustness of the two-color method for situations where emissivity is constant but unknown (gray-body assumption) while integrating a three-color method to detect and compensate for situations where emissivity varies with wavelength (non-gray surfaces). This combination provides a more reliable temperature measurement for a wider range of materials with complex, unknown emissivity characteristics [38] [39].

Q2: My two-color pyrometer shows inconsistent results on an oxidized metal surface. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. The two-color method assumes emissivity is the same at both wavelengths. If the surface oxidation causes the emissivity to vary differently at the two wavelengths you are using (a non-gray surface), this assumption is violated and introduces error [38]. A hybrid method that includes a third wavelength can help identify and correct for this specific type of emissivity variation [39].

Q3: How do I select the optimal wavelengths for my hybrid pyrometer setup? Wavelength selection is critical. The chosen wavelengths should:

- Be located in a region of the spectrum where the object's radiation is strong enough to be detected.

- Avoid atmospheric absorption bands (e.g., from water vapor) to minimize signal loss [38].

- For the two-color part of the system, a smaller difference between wavelengths can lead to more consistent calculations if the emissivity is gray, but the optimal difference depends on the expected temperature range and surface properties [38]. For the three-color component, the wavelengths should be spaced to effectively detect emissivity trends [39].

Q4: What are the common sources of error in hybrid pyrometry, and how can I minimize them? Key sources of error include:

- Emissivity Variation: Non-gray emissivity behavior is the primary challenge that hybrid methods aim to solve [38].

- Measurement Noise: Multi-wavelength systems can be more sensitive to signal-to-noise ratios, which can be exacerbated when adding more spectral bands [38]. Using high-quality detectors and appropriate signal processing is essential.

- Calibration Drift: Regular calibration against a blackbody reference is necessary to maintain accuracy [38].

- Optical Alignment: For systems with multiple detectors, precise alignment is crucial to ensure you are measuring the exact same spot on the target [38].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Erratic temperature readings on a surface with known oxidation. | Emissivity is wavelength-dependent, violating the gray-body assumption of a standard two-color pyrometer. | Switch to or activate the three-color mode of your hybrid system to account for the non-gray emissivity [39]. |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio, especially at lower temperatures. | Weak thermal radiation signal. | Optimize sensor exposure time and gain settings [38]. Ensure optical lenses are clean and use detectors with higher quantum efficiency [38]. |

| Discrepancy between pyrometer readings and thermocouple data. | Possible reflection of ambient radiation from the target surface. | Use a gold-plated reflector in the setup or apply a narrow-bandpass filter to reduce the effect of ambient light and reflected radiation [38]. |