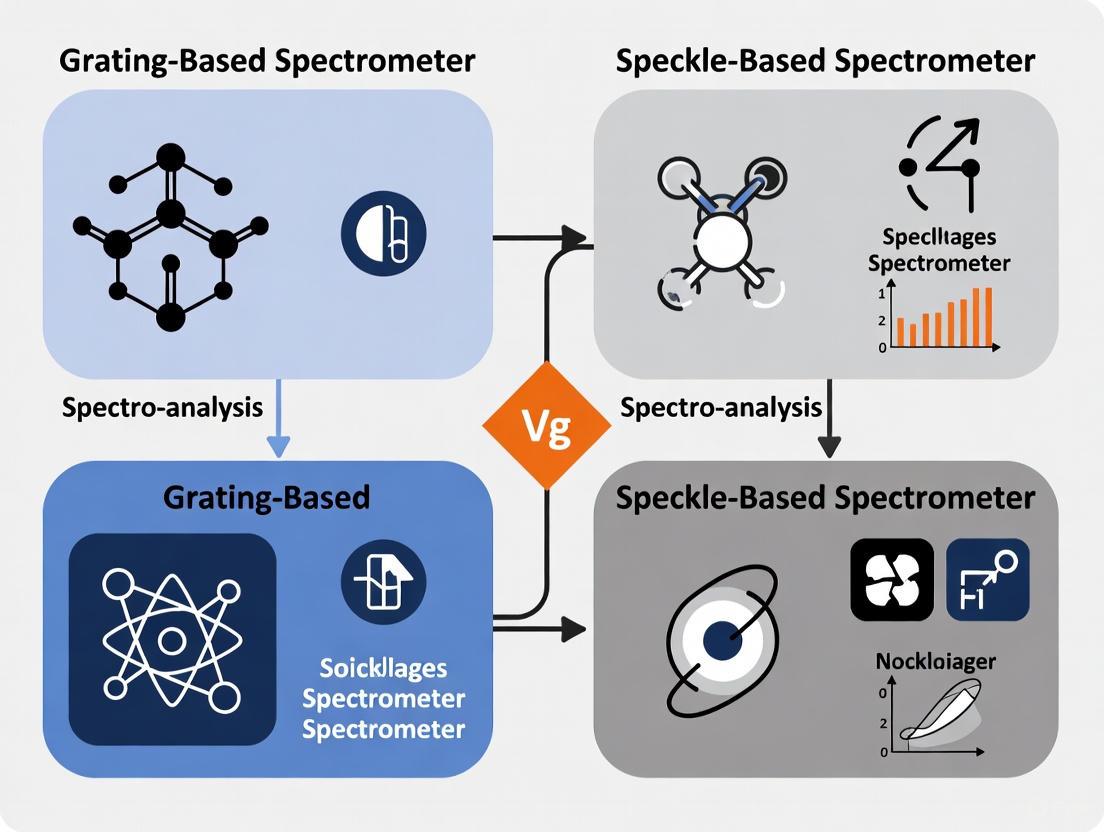

Noise Performance Showdown: Grating vs. Speckle Spectrometers for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of noise performance between traditional grating-based and emerging speckle-based spectrometers, with a specific focus on applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Noise Performance Showdown: Grating vs. Speckle Spectrometers for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of noise performance between traditional grating-based and emerging speckle-based spectrometers, with a specific focus on applications in biomedical research and drug development. We explore the foundational principles governing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in each technology, analyze their methodological implementations for spectral detection, and provide practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. By synthesizing theoretical models and experimental validations, we deliver a clear comparative analysis to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate spectrometer technology for low-light applications such as Raman spectroscopy and near-infrared tissue analysis, balancing the critical factors of sensitivity, footprint, and spectral accuracy.

Fundamental Noise Principles in Grating and Speckle Spectrometers

Optical spectrometers are indispensable tools in scientific research and drug development, enabling precise analysis of material composition through light interaction. The evolution of spectrometer technology has bifurcated into two distinct paradigms: traditional spatial dispersion and emerging computational reconstruction. Spatial dispersion systems, such as grating-based spectrometers, separate light into its constituent wavelengths across physical space using optical elements like diffraction gratings. In contrast, computational reconstruction approaches, including speckle-based systems, encode spectral information into complex light patterns that are subsequently decoded using advanced algorithms. Understanding the core operating principles, performance characteristics, and noise considerations of these architectures is essential for selecting the appropriate technology for specific applications in research and development.

Fundamental Operating Principles

Spatial Dispersion Spectrometers

Spatial dispersion spectrometers operate on the long-established principle of physically separating different wavelengths of light onto distinct detector elements. This is typically achieved using a diffraction grating or prism that angularly disperses incoming light based on wavelength. In a standard grating-based instrument, collimated light strikes a diffraction grating where different wavelengths are diffracted at different angles according to the grating equation, subsequently focused by optics onto a detector array such as a CCD or CMOS sensor. This creates a direct wavelength-to-position mapping on the detector, where each pixel corresponds to a specific spectral channel [1].

The mathematical relationship follows a direct mapping framework where the detected signal at each pixel can be represented as y = Gs + η, where y is the measurement vector, G is a predominantly diagonal matrix representing the system's spectral response, s is the unknown spectrum vector, and η represents measurement noise [1]. This one-to-one correspondence between wavelength and detector pixel simplifies reconstruction but inherently limits spectral resolution by the number of available detector pixels and requires substantial optical path lengths for high resolution.

Computational Reconstruction Spectrometers

Computational reconstruction spectrometers, including speckle-based systems, employ a fundamentally different approach where spectral information is encoded rather than dispersed. These systems use engineered structures such as random scattering media, metasurfaces, or filter arrays to create wavelength-dependent transmission patterns that are recorded as intensity distributions. Instead of direct wavelength-to-position mapping, these devices produce complex fingerprints where each wavelength generates a unique spatial pattern, and broadband light creates a superposition of these patterns [2] [1].

The mathematical foundation follows an underdetermined system representation: I = T × S, where I is the measured intensity pattern, T is the pre-calibrated transmission matrix of the system, and S is the unknown spectrum [2]. Reconstruction involves solving this inverse problem using computational algorithms ranging from compressive sensing to deep learning approaches. This paradigm decouples spectral resolution from physical footprint, enabling extremely compact devices with high channel counts by leveraging computational power rather than large optical paths.

Performance Comparison and Noise Analysis

The fundamental architectural differences between spatial dispersion and computational reconstruction spectrometers yield distinct performance characteristics, particularly regarding noise behavior, resolution, and spectral range. The table below summarizes key quantitative performance metrics from recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Spectrometer Architectures

| Performance Parameter | Spatial Dispersion (Grating-Based) | Computational Reconstruction (Speckle-Based) | Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Resolution | 1.4 cm⁻¹ [3] | 70 pm (0.07 nm) [2] | Across different operational bands |

| Bandwidth | 3800 cm⁻¹ [3] | 100 nm [2] | Specific to implemented systems |

| Channel Density | Limited by detector array size | 10,021 ch/mm² [2] | Benchmark metric for miniaturization |

| Noise Characteristics | Classical photon shot noise dominant [1] | Reconstruction-dependent noise amplification [1] | Varies with signal strength |

| Visibility/Contrast | ~50% efficiency demonstrated [3] | Reconstruction fidelity >80% [4] | Application-dependent requirements |

Noise Performance and Signal Fidelity

Noise behavior represents a critical differentiator between these architectures. Grating-based systems predominantly exhibit classical noise sources including photon shot noise and detector read noise, with well-understood propagation through the direct reconstruction process [1]. Recent research has refined noise models for such systems, demonstrating that traditional models may overestimate dark-field signal noise by more than 30% in high-visibility systems (visibility >0.5) [5].

Computational spectrometers face additional noise complexities arising from the reconstruction process itself. The ill-conditioned nature of the reconstruction matrix T can amplify measurement noise, requiring regularization techniques during inversion [1]. Experimental validation of speckle-based systems shows successful reconstruction of narrowband spectra with mean square errors of 1.05×10⁻³ and accurate identification of chemical compounds with 81.38% precision in the mid-infrared range [4]. The multi-layer metasurface approach demonstrates enhanced robustness by increasing effective interference path lengths and creating more distinctive spectral fingerprints [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Grating-Based Spectrometer Characterization

Recent high-performance grating spectrometer implementations utilize optimized optical layouts to achieve exceptional resolution-bandwidth products. One experimental protocol involved:

- Optical Configuration: Employing a fast F0.95/50 mm camera lens traversed by both input and grating-dispersed light

- Grating Specification: Using a diffraction grating with precisely controlled groove density and blaze angle

- Detection System: Implementing a high-quantum-efficiency detector array with low read noise

- Calibration Procedure: Using atomic emission lines from standard sources for wavelength calibration

- Noise Measurement: Quantifying signal-to-noise ratio across the spectral range using calibrated light sources [3]

This approach achieved a spectral resolution of 1.4 cm⁻¹ over 3800 cm⁻¹ range without moving parts, demonstrating >50% efficiency for p-polarized light in the green region [3].

Speckle-Based Spectrometer Implementation

Advanced speckle-based spectrometers employ sophisticated metasurface engineering and reconstruction algorithms:

- Metasurface Fabrication: Creating multi-layer disordered metasurfaces on silicon-on-insulator (SOI) platforms using standard lithography

- System Architecture: Implementing three cascaded metasurface layers with 100 μm separation to enhance spectral channel capacity

- Calibration Process: Mapping the transmission matrix

Tby measuring system response to monochromatic sources across the operational band - Reconstruction Algorithm: Applying deep learning networks trained on diverse spectral datasets with noise augmentation for robustness

- Performance Validation: Testing with narrowband spectra of varying center wavelengths and linewidths to establish resolution limits [2]

This methodology enabled 70 pm resolution over 100 nm bandwidth in a compact 150 μm × 950 μm footprint, achieving unprecedented channel density [2].

Table 2: Experimental Components and Their Functions

| Component Category | Specific Elements | Function in Experimental Setup |

|---|---|---|

| Optical Elements | Diffraction Gratings, Metasurfaces, Polarizers, Lenses | Wavelength dispersion or spectral encoding |

| Detection Systems | CCD/CMOS Arrays, Single-Pixel Detectors | Capture intensity patterns or dispersed spectra |

| Calibration Tools | Monochromators, Atomic Lamps, Standard Reference Materials | System characterization and wavelength calibration |

| Computational Resources | GPUs, Reconstruction Algorithms (Compressive Sensing, Deep Learning) | Spectrum recovery from encoded measurements |

| Fabrication Platforms | Silicon Photonics, Electron Beam Lithography | Miniaturized spectrometer component manufacturing |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components

Core Technologies and Materials

Implementing advanced spectrometer systems requires specific components and materials tailored to each architecture:

Spatial Dispersion Systems: High-linearity detector arrays (CCD/CMOS), precision diffraction gratings (holographic or ruled), aberration-corrected optics (lenses/mirrors), and stable mechanical mounts comprise essential components. Recent designs utilize toroidal gratings to correct astigmatism across wide bandwidths [3].

Computational Reconstruction Systems: Engineered spectral encoders (metasurfaces, quantum dots, photonic crystal slabs) [4], high-frame-rate imaging sensors, and computational resources for reconstruction algorithms are fundamental. The single-spinning film encoder (SSFE) represents an innovative approach using alternating TiO₂ and SiO₂ layers on sapphire substrates to create polarization-separated spectral responses [4].

Reconstruction Algorithms and Software

Computational spectrometers rely heavily on algorithmic approaches for spectrum recovery:

Compressive Sensing Methods: Utilizing sparsity-based regularization to solve underdetermined systems, offering enhanced noise robustness but slower reconstruction [1]

Deep Learning Approaches: Employing neural networks for rapid reconstruction, achieving high throughput but requiring extensive training datasets and being potentially more noise-sensitive [4] [1]

Hybrid Techniques: Combining physical models with data-driven approaches to balance reconstruction speed and noise resilience [1]

Application-Specific Implementation Guidance

Selection Criteria for Research Applications

Choosing between spatial dispersion and computational reconstruction architectures depends on application requirements:

High-Sensitivity Applications: Grating-based systems with their direct detection approach often provide superior signal-to-noise ratio for low-light applications such as Raman spectroscopy or fluorescence measurements [3].

Size-Constrained Implementations: Computational spectrometers offer compelling advantages in portable devices, wearable sensors, and highly integrated systems where minimal footprint is critical [2].

Broadband Spectral Analysis: Applications requiring operation across multiple wavelength bands (visible to mid-infrared) may benefit from computational approaches like the single-spinning film encoder that can cover 400-700 nm, 700-1600 nm, and 3-5 μm ranges [4].

Rapid Process Monitoring: Grating-based systems with direct readout capabilities typically offer faster acquisition times for dynamic processes, while computational systems require reconstruction time [6].

Emerging Trends and Future Developments

The field of spectrometer technology continues to evolve with several promising directions:

Hybrid Architectures: Combining elements of both spatial dispersion and computational reconstruction to leverage advantages of both approaches [1]

Advanced Materials: Utilizing metasurfaces and nanophotonic structures to enhance light-matter interactions and improve encoding efficiency [2]

Noise-Aware Reconstruction: Developing algorithms that explicitly model noise characteristics during reconstruction to improve fidelity [5] [1]

Multi-Modal Sensing: Integrating spectroscopic capabilities with other sensing modalities for comprehensive sample characterization [4]

The comparison between spatial dispersion and computational reconstruction spectrometers reveals a complex trade-space where no single architecture dominates across all performance metrics. Grating-based spatial dispersion systems offer mature technology, straightforward operation, and excellent noise performance for many conventional applications. Computational reconstruction approaches enable unprecedented miniaturization and spectral channel density while introducing new noise considerations in the reconstruction process. The optimal choice depends critically on specific application requirements including size constraints, spectral resolution needs, operational bandwidth, and noise tolerance. Future developments will likely see further convergence of these approaches alongside improved noise modeling and reconstruction algorithms to enhance measurement fidelity across diverse scientific applications.

Theoretical Models for Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in Spectrometry

The accurate modeling of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is fundamental to the advancement of spectroscopic techniques, directly impacting instrument detection limits and measurement reliability. This guide provides a systematic comparison of SNR theoretical models between two prominent approaches: grating-based spectrometers and the emerging technique of speckle-based spectrometry. Within the broader research context comparing these technologies, understanding their distinct noise characteristics and performance trade-offs is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals selecting appropriate tools for specific applications. Grating-based systems offer well-established noise models, while speckle-based methods present unique advantages in phase-contrast imaging and simplified setups. This article examines their theoretical foundations, experimental validation protocols, and quantitative performance data to inform instrument selection and development.

Theoretical SNR Models: Core Principles and Equations

Grating-Based Spectrometer Noise Models

Grating-based spectrometers employ diffraction elements to spatially separate wavelengths, with well-characterized but complex noise behavior. A revised noise model for dark-field imaging using grating interferometers addresses limitations of earlier approximations, providing accurate predictions across varying visibility conditions [5].

The fundamental intensity equation in a grating interferometer is:

I(xg) = I0[1 + V cos(2πxg/p + φ)]

where I0 is the mean intensity, V is visibility, xg is grating position, p is grating period, and φ is the phase [5]. Earlier models simplified noise calculations by assuming low visibility (V), but the revised model eliminates this limitation, accurately predicting noise behavior even with high-visibility systems (e.g., V = 0.52) where previous models exhibited >30% error [5].

For optical diffraction grating spectrometers, performance is characterized by high spectral-range-to-resolution ratios (e.g., 3800 cm⁻¹ range at 1.4 cm⁻¹ resolution) with >50% detection efficiency for p-polarized light in the green spectrum [3]. These systems achieve low noise without thermoelectric cooling, making them suitable for portable Raman trace-gas sensing [3].

Speckle-Based Spectrometry Noise Models

Speckle-based techniques leverage statistical properties of speckle patterns generated by light interference, with distinct noise considerations. The speckle contrast (K) is a fundamental parameter defined as K = σ(I)/⟨I⟩, where σ(I) is the standard deviation and ⟨I⟩ is the mean of the speckle intensity [7].

The image formation model follows:

I(r→) = O(r→) ∗ S(r→) + N

where O(r→) is the object image, S(r→) is the point spread function, ∗ denotes convolution, and N represents noise [8]. The object's Fourier amplitude spectrum can be retrieved through autocorrelation based on the Wiener-Khinchin theorem [8].

Recent advances include speckle refinement methods with self-calibrated homomorphic filtering (SCHF) that improve SNR by decomposing speckle images into in-focus and out-of-focus components, then suppressing the noise component to enhance contrast [8]. This approach adaptively determines optimal filtering parameters based on the physical mechanism of speckle correlation, significantly improving performance under challenging conditions like ambient light interference [8].

Experimental Protocols for SNR Validation

Grating-Based Spectrometer Characterization

Table 1: Key experimental parameters for grating-based spectrometer SNR validation

| Parameter | Specification | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Resolution | 1.4 cm⁻¹ [3] | Spectral line width measurement |

| Spectral Range | 3800 cm⁻¹ [3] | Wavelength scanning calibration |

| Detection Efficiency | >50% (p-polarized green light) [3] | Polarized light transmission measurement |

| Visibility Measurement | Critical for noise model validation [5] | Intensity oscillation analysis at multiple grating positions |

| Dark-Field Signal Validation | Comparison of predicted vs. measured standard deviation [5] | Multiple exposure measurements at high visibility (e.g., V=0.52) |

Experimental validation of grating-based system noise models requires precise characterization across multiple operational parameters. Synchrotron radiation experiments at facilities like the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility have verified revised noise models using Talbot interferometers with phase gratings (2.39 μm pitch, π/2 phase shift at 20 keV) and absorption gratings (2.4 μm pitch) [5]. The validation involves collecting raw images with scientific CMOS cameras at various grating positions and comparing measured standard deviations of dark-field signals against theoretical predictions [5].

Speckle-Based System Characterization

Table 2: Experimental parameters for speckle-based spectrometry SNR validation

| Parameter | Specification | Measurement Method |

|---|---|---|

| Speckle Contrast (K) | K = σ(I)/⟨I⟩ [7] | Statistical analysis of speckle pattern |

| Camera Characterization | Gain, dark offset, read noise [7] | Photon transfer curve with integrating sphere |

| SCHF Parameter Optimization | Adaptive filter parameter selection [8] | Edge point intensity analysis for autocorrelation quality |

| Ambient Light Robustness | Performance under varying SNR conditions [8] | Controlled illumination experiments |

| Spatial Resolution | Determined by speckle-to-pixel ratio [7] | Calibration with standard targets |

Speckle contrast optical spectroscopy (SCOS) requires comprehensive camera characterization to accurately quantify noise performance. The experimental protocol involves determining camera gain (g), per-pixel dark offset (⟨I⟩_dark(x,y)), and per-pixel read noise (σ_r(x,y)) using uniform illumination from an integrating sphere with baffles to eliminate direct light paths [7]. The photon transfer curve is obtained by illuminating the camera at different intensities and collecting multiple frames at each intensity level [7]. For speckle refinement methods, validation involves comparing reconstructed image quality with and without SCHF processing under challenging conditions like broadband illumination and ambient light interference [8].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for speckle correlation imaging with camera characterization and SCHF processing

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative SNR Comparison

Table 3: Direct performance comparison between grating and speckle-based techniques

| Performance Metric | Grating-Based Spectrometry | Speckle-Based Imaging |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Wavelength dispersion via diffraction [3] | Speckle correlation and statistical analysis [8] |

| Spectral Resolution | 1.4 cm⁻¹ demonstrated [3] | Resolution determined by autocorrelation quality [8] |

| Key Advantages | High resolution, well-established models [3] [5] | No phase unwrapping, simpler setup [9] |

| Noise Challenges | Visibility-dependent noise model accuracy [5] | Ambient light sensitivity, contrast reduction [8] |

| Experimental Complexity | Requires precise grating alignment [5] | Less stringent coherence requirements [9] |

| Optimal Applications | High-resolution Raman spectroscopy [3] | Phase-contrast imaging, scattering media [9] |

Experimental comparisons between speckle and grating-based techniques using synchrotron radiation X-rays reveal that speckle-based imaging does not suffer from phase unwrapping issues that often complicate grating-based interferometry [9]. Additionally, speckle-based methods can simultaneously extract two orthogonal differential phase gradients with a one-dimensional scan, providing an efficiency advantage for certain applications [9]. However, grating-based systems typically have less stringent requirements for detector pixel size and transverse coherence length when incorporating second or third gratings [9].

Instrument Design and Throughput Considerations

Fourier transform spectrometers (a related class of instruments) exhibit the "Jacquinot advantage" – for non-point sources, they provide more light throughput at equivalent resolution compared to grating spectrometers due to their two-dimensional pinhole geometry versus the one-dimensional slit in grating systems [10]. This fundamental advantage translates to potentially higher SNR for certain measurement scenarios. The throughput advantage scales geometrically: halving the slit width in a grating spectrometer doubles resolution but halves signal, while halving the pinhole diameter in an FT spectrometer doubles resolution but reduces signal to one-fourth [10].

Figure 2: Key SNR determining factors for grating-based and speckle-based spectrometry systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential research reagents and materials for spectrometry SNR studies

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Standards | Octafluoronaphthalene (OFN), Hexachlorobenzene (HCB) [11] | MS performance validation and noise calibration |

| Optical Components | Phase gratings (2.39 μm pitch), Absorption gratings (2.4 μm pitch) [5] | Grating interferometer construction and characterization |

| Light Sources | M730L5 LED, Narrowband sources (625 nm) [8] [7] | Controlled illumination for system characterization |

| Detection Systems | Scientific CMOS cameras (e.g., Hamamatsu Orca Fusion, Basler models) [7] | Speckle pattern capture with optimized noise performance |

| Calibration Tools | Integrating spheres, Photodiode power meters [7] | Uniform illumination reference and power monitoring |

| Software Algorithms | Self-calibrated homomorphic filtering, Noise correction procedures [8] [7] | Advanced signal processing for SNR enhancement |

The theoretical models for SNR in spectrometry reveal fundamentally different approaches and performance considerations for grating-based versus speckle-based systems. Grating-based spectrometers benefit from well-established noise models recently refined for high-visibility conditions, enabling high spectral resolution and efficiency for applications like Raman spectroscopy. Speckle-based techniques offer advantages in simplified setup, elimination of phase unwrapping, and the ability to extract multidimensional phase information, though they require sophisticated statistical processing and camera characterization. The choice between these technologies depends heavily on specific application requirements, with grating systems favoring high-resolution spectral analysis and speckle-based methods showing strength in phase-contrast imaging through scattering media. Future developments in both fields will likely focus on further refining noise models, improving computational processing, and expanding practical applications across scientific and industrial domains.

In advanced optical systems, particularly spectrometers, the quality of acquired data is fundamentally governed by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the distinct noise sources in different spectrometer architectures is crucial for selecting the appropriate technology for specific applications, whether in material characterization, pharmaceutical analysis, or biological sensing. Noise characteristics often dictate the practical boundaries of detection sensitivity, measurement speed, and ultimately, the reliability of analytical results.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of noise performance between two competing spectrometer technologies: grating-based spectrometers and emerging speckle-based systems. Grating-based instruments, which separate light spatially using diffraction gratings, have long been the workhorse of analytical spectroscopy. More recently, speckle-based techniques have emerged as a promising alternative, using random scattering media to encode spectral information through speckle pattern analysis. The fundamental operational differences between these platforms lead to significantly distinct noise profiles, with each exhibiting particular strengths and weaknesses across various measurement conditions.

The Noise Trinity: Shot, Detector, and Speckle Noise

All optical detection systems, including spectrometers, are subject to several fundamental noise sources that determine their ultimate performance limits. These can be broadly categorized as follows:

- Shot Noise: This fundamental noise arises from the statistical quantum nature of light and photon detection. Also known as photon noise, it follows a Poisson distribution, meaning the noise magnitude is proportional to the square root of the incident photon flux [12] [13]. Shot noise becomes the dominant limitation in high-light conditions and sets the theoretical best-case performance for any optical measurement.

- Detector Noise: This encompasses several noise components inherent to the photodetector itself [12] [14]:

- Readout Noise: Electronic noise from the detector output stage and associated circuitry, which primarily sets the instrument's detection limit under low-light conditions.

- Dark Noise: Statistical variation in thermally generated electrons (dark current) within the detector. This noise is highly temperature-dependent and can be reduced by thermoelectric cooling.

- Fixed Pattern Noise: Pixel-to-pixel variation in photo-response caused by manufacturing imperfections in the detector array.

- Speckle Noise: A phenomenon specific to measurements with coherent light sources, speckle noise manifests as random intensity fluctuations caused by interference of multiple random paths taken by photons [13]. The standard deviation of these fluctuations can be a significant fraction of the mean intensity, potentially dominating the noise budget in coherent imaging systems.

Visualizing Noise Source Relationships

The following diagram illustrates how different noise sources manifest in a typical optical detection system and their relationship to the measured signal.

Comparative Analysis: Grating vs. Speckle Spectrometers

Operational Principles and Noise Characteristics

The core architectural differences between grating and speckle spectrometers lead to fundamentally different noise behaviors.

- Grating-Based Spectrometers (GS): These conventional instruments use a diffraction grating to spatially disperse spectral components onto a detector array [15]. The spectrum is reconstructed by directly mapping pixel signals to wavelengths. Their noise performance is well-understood, typically dominated by shot noise and detector noise [15] [14]. They are considered the benchmark for many spectroscopic applications.

- Spatial Heterodyne Spectrometers (SHS): A Fourier-transform-based variant of grating spectrometers, SHS offers a larger etendue (light-gathering power) and greater potential for miniaturization. While still subject to similar shot and detector noise, their multiplexing nature distributes shot noise across spectral elements, which can be advantageous or disadvantageous depending on the measurement context [15].

- Speckle-Based Spectrometers (SBS): These systems utilize a disordered medium to generate a wavelength-dependent speckle pattern that acts as a spectral fingerprint [16]. While they offer simplicity and compactness, they introduce a unique and significant noise source: speckle noise [13] [16]. This noise results from temporal and spatial fluctuations in the speckle pattern and can become the dominant noise source, particularly for weak or broadband signals [16].

Quantitative Noise Performance Comparison

The table below summarizes key performance characteristics and noise attributes of grating-based and speckle-based spectrometers, synthesized from comparative studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Grating-Based and Speckle-Based Spectrometers

| Parameter | Grating-Based Spectrometer (GS) | Spatial Heterodyne Spectrometer (SHS) | Speckle-Based Spectrometer (SBS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Noise Sources | Shot noise, detector noise [15] [14] | Shot noise, detector noise [15] | Speckle noise, shot noise [13] [16] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Generally high for intense signals [15] | Competitive with GS; potential for better performance in specific regimes [15] | Degrades significantly for weak or broadband signals [16] |

| Etendue (Light Throughput) | Limited by entrance slit [15] | High (10-100x GS) [15] | Configuration-dependent |

| Key Strengths | Mature technology, high SNR for strong signals, well-understood noise profile [15] [14] | High throughput, compact footprint, good SNR potential [15] | Simple, low-cost setup, no need for high-precision optics [17] |

| Key Limitations | Slit limits throughput, mechanical scanning in some designs | Multiplex noise disadvantage in high-background scenarios [15] | Speckle noise limits maximum achievable SNR [13] [16] |

| Best-Suited Applications | High-precision spectroscopy, Raman spectroscopy [15] [14] | Portable spectroscopy, low-light applications [15] | Applications where cost/simplicity outweigh SNR demands, narrowband signal measurement [16] |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Characterization

Methodology for Grating Spectrometer Noise Analysis

A systematic approach to model and measure noise in grating spectrometers involves the following steps, derived from analytical models in the literature [15]:

- Define Spectral Scenario: Characterize the input light spectrum, identifying a target Raman or emission line (with peak radiance (B0) and linewidth (\Delta\nu0)), neighboring spectral components, and a flat background continuum (with radiance (B_b)) [15].

- Parameterize Spectral Components: Introduce dimensionless parameters to describe the spectral richness ((\kappan = An/A0)), background level relative to the target peak ((\kappab = Bb/B0)), and the sharpness of the target line ((\kappaw = \Delta\nu0 / (\nub-\nua))) [15].

- Calculate Total Radiance: Compute the total radiance (A) entering the spectrometer using the expression (A = B0\kappaw(1+\kappan) + \kappab) [15].

- Model Signal and Noise: The signal at the detector is given by (S(\nu) = G L(\nu)B(\nu)\Delta t), where (G) is the etendue, (L(\nu)) is the system throughput, and (\Delta t) is the measurement time. The total noise is calculated as the root sum square of shot noise ((\propto \sqrt{S})), dark current noise, and read-out noise [15].

- Compute SNR: The SNR is derived as the ratio of the target signal to the total noise in the spectral region of interest. Simplified expressions can be applied in limiting cases, such as when background-dominated or shot-noise-limited [15].

Methodology for Speckle Noise Quantification

For speckle-based systems, the experimental protocol must explicitly account for the speckle noise contribution [13]:

- System Setup: Employ a coherent light source (e.g., laser diode) and a random scattering material (e.g., abrasive paper, filter membrane) to generate a near-field speckle pattern. An area detector records the pattern.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire a reference speckle image ((I{ref})) without the sample. Introduce the sample and acquire the sample speckle image ((I{sample})). For scanning techniques, translate the diffuser in one dimension while recording multiple images [17].

- Speckle Displacement Tracking: Use cross-correlation algorithms (e.g., zero-normalized cross-correlation) to calculate the local transverse displacement field (D\perp(x, y)) between (I{ref}) and (I_{sample}) [18].

- Phase and Dark-Field Retrieval: Retrieve the differential phase gradient from the displacement map: (\alpha \approx D\perp \cdot p / (\lambda L)), where (p) is the pixel size, (\lambda) is the wavelength, and (L) is the sample-detector distance. The dark-field signal (DS) is related to the decorrelation of the speckle pattern: (D_S \approx -2\ln|\gamma|), where (\gamma) is the cross-correlation coefficient [17].

- Incorporate Speckle Noise Model: The total noise for a coherent NIRS system can be modeled as per the equation below. The speckle noise term is critical and is given by (\sigmaI = \langle I \rangle \sqrt{\beta \tauc / (MT)}), where (\beta) is an optical constant, (\tau_c) is the speckle decorrelation time, (M) is the number of speckles, and (T) is the integration time [13].

Table 2: Essential Materials for Speckle-Based Spectrometry Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Coherent Light Source (e.g., Laser Diode) | Generates coherent light required to form a speckle pattern. |

| Random Scattering Medium (e.g., Sandpaper, Filter Membrane) | Acts as a diffuser to create the random speckle pattern used for wavefront encoding. |

| High-Resolution Area Detector (e.g., sCMOS, CCD Camera) | Records high-fidelity speckle patterns with minimal intrinsic detector noise. |

| Precision Translation Stage | Enables speckle scanning for enhanced resolution in scanning SBI techniques. |

Experimental Data and Case Studies

Direct Comparison in X-Ray Imaging

A direct experimental comparison between GBI and SBI for X-ray phase-contrast imaging provides valuable insights [17]. The study found that while SBI benefits from a simpler setup and does not suffer from phase unwrapping issues, it has distinct performance trade-offs:

- Performance vs. Signal Strength: SBI provided comparable performance to GBI when measuring intense or narrowband probe signals. However, its accuracy degraded significantly relative to GBI when measuring weak or broadband signals [16] [17].

- Noise and Sensitivity: The primary factor behind this performance gap is the speckle noise inherent in SBI. This noise places a fundamental limit on the maximum achievable SNR for SBI, a limitation that is less severe in GBI for these specific signal conditions [13] [17].

The Impact of Speckle Noise in NIRS Systems

Research on Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (NIRS) systems highlights the profound impact of speckle noise in coherent systems [13]. The study introduced an extended noise model incorporating speckle and demonstrated that at short source-detector separations, speckle can contribute most of the system noise when using long-coherence-length sources. This finding is crucial for system design, indicating that simply increasing optical power does not indefinitely improve SNR in speckle-prone systems, as the SNR asymptotically reaches a limit set by the speckle statistics [13].

The choice between grating-based and speckle-based spectrometers is not a matter of identifying a universally superior technology, but rather of matching the instrument's noise characteristics to the application's specific requirements.

- For applications demanding the highest possible SNR, particularly with weak or broadband signals, grating-based spectrometers remain the gold standard due to their mature design and well-characterized noise profile dominated by fundamental shot and detector noise [15] [14].

- Speckle-based spectrometers offer compelling advantages in terms of cost, simplicity, and compactness. However, the presence of speckle noise as a dominant and often limiting factor must be carefully considered [13] [16]. They are most suitable for applications where these practical benefits outweigh the need for ultimate sensitivity or where signals are sufficiently intense to overcome speckle-induced limitations.

For researchers in drug development and related fields, this analysis underscores that noise performance is a critical specification. The decision should be guided by the spectral characteristics of the target analyte, the available light budget, and the required detection limits, with a clear understanding of the distinct noise trade-offs between these two spectroscopic architectures.

This guide objectively compares the performance of grating-based and speckle-based spectrometers, focusing on the core metrics of etendue, spectral resolution, and channel density. The analysis is framed within a broader research context investigating the noise performance of these spectrometer technologies.

Performance Metrics Comparison

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics for state-of-the-art grating-based and speckle-based spectrometers as reported in recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Grating-based and Speckle-based Spectrometers

| Spectrometer Technology | Spectral Resolution | Bandwidth | Channel Density (ch/mm²) | Footprint | Key Performance Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Chip Diffractive Speckle Spectrometer [19] | 70 pm | 100 nm | 10,021 | 150 µm × 950 µm | Scalable via cascaded metasurfaces; high channel density |

| Single-Shot Speckle Spectrometer [20] | 10 pm | 200 nm | Not Explicitly Reported | 2 mm² (chip) | 2730 independent sampling channels; single-shot capture |

| MLAG Grating-Based Spectrometer [21] | 3.0 nm (practical) | 380-780 nm | ~20.7 (for 2070 channels in ~100 mm²) | ~10 mm × 10 mm | 2070 parallel channels; high uniformity for arrayed sources |

| Brillouin Integrated Spectrometer [22] | 0.56 nm | 110 nm | Not Explicitly Reported | 1 mm (waveguide length) | Single waveguide; dynamic grating; fast spectral sweeping |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Characterization

Standardized experimental methods are crucial for the fair comparison of spectrometer technologies.

Spectral Resolution and Bandwidth Assessment

The fundamental protocol involves illuminating the spectrometer with a tunable, narrow-linewidth laser across the entire operational bandwidth [20]. The output signal is recorded at fine wavelength intervals. The Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of the system's response to this input laser is used to determine the spectral resolution [22]. For speckle spectrometers, the spectral correlation width—the wavelength shift at which the output speckle pattern decorrelates to half its original similarity—is a key indicator of potential resolution [19] [20].

Channel Density and Etendue Evaluation

- Channel Density Calculation: The total number of spectral channels (Bandwidth/Resolution) is divided by the device's footprint area [19].

- Etendue for Grating-Based Systems: For grating-based systems like the MLAG, etendue is managed by using microlens arrays and apertures to control the divergence angle of incident light from each sub-source, ensuring efficient coupling into the dispersed channels [21].

- Etendue for Speckle-Based Systems: The etendue is intrinsically high due to the use of a multimode or scattering structure. The effective light-gathering capability is coupled with the need for a high-pixel-count camera to resolve the complex speckle pattern, making the setup more complex but enabling high information density from a compact chip [20].

Technology Workflows and Operating Principles

The fundamental difference in how grating-based and speckle-based spectrometers encode spectral information leads to distinct experimental workflows.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation and testing of spectrometer technologies, particularly in sensing applications, rely on a standard set of materials and components.

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Spectrometer Characterization

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Narrow-Linewidth Laser | System calibration; measures spectral response and resolution [20]. | Used in transmission matrix calibration for speckle spectrometers [19] [20]. |

| Silicon-on-Insulator (SOI) Wafer | Standard substrate for fabricating on-chip photonic components [19] [20]. | Platform for waveguides, metasurfaces, and unbalanced MZIs. |

| Polystyrene | Reference material for real-time wavelength and intensity calibration [23]. | Built-in reference channel in miniaturized Raman spectrometers. |

| High-Pixel-Count SWIR Camera | Captures high-dimensional speckle patterns for reconstruction [20]. | Images speckle patterns diffracted from the photonic chip. |

| Lithium Niobate (LN) on Sapphire | Hybrid photonic-phononic circuit platform for non-linear spectrometers [22]. | Enables strong Brillouin interaction for dynamic grating formation. |

| Vector Network Analyzer (VNA) | Drives transducers and characterizes RF-to-acoustic conversion [22]. | Supplies RF signal to IDT in Brillouin spectrometers. |

The Multiplex Advantage and Disadvantage in Fourier Transform Systems

Fourier Transform Spectrometry (FTS) is a powerful analytical technique that has revolutionized spectral analysis across numerous scientific fields, from pharmaceutical development to astronomical observation. At the core of its operational principle lies the multiplex advantage, also known as Fellgett's advantage after its discoverer. This fundamental principle states that an FTS simultaneously measures all spectral elements across its entire operational bandwidth throughout the measurement process, unlike dispersive instruments which measure spectral elements sequentially [24]. For signal-limited applications where detector noise predominates, this simultaneous measurement provides a significant signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) improvement proportional to the square root of the number of resolved spectral elements [25].

However, the theoretical benefits of multiplexing confront practical limitations under specific experimental conditions. Recent research has revealed that the multiplex advantage transforms into a distinct disadvantage in measurement regimes dominated by photon noise (shot noise) rather than detector noise [26] [27] [28]. This critical limitation arises because the multiplexing process introduces photon noise from the entire spectral bandwidth into every measured spectral channel during the reconstruction process. When the signal-dependent photon noise becomes the dominant noise source, the SNR of a Fourier Transform Spectrometer can become inferior to that of sequential monochromators or dispersive spectrometers measuring the same signal [27] [29]. This comprehensive analysis examines both the advantages and limitations of multiplexing in Fourier transform systems, providing researchers with the experimental data and theoretical framework necessary to select the optimal spectroscopic architecture for specific application requirements.

Theoretical Foundations of the Multiplex Advantage

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Basis

The multiplex advantage in Fourier Transform spectroscopy originates from the fundamental design of the instrument. In a conventional FTS, the entire spectrum is encoded into an interferogram through the manipulation of optical path differences (OPD). The mathematical foundation relies on the fact that the measured interferogram I(δ) represents the Fourier transform of the desired spectrum B(σ):

I(δ) = ∫ B(σ) cos(2πσδ) dσ

where δ is the optical path difference and σ is the wavenumber [25]. The inverse Fourier transform of the measured interferogram recovers the spectrum, allowing all spectral elements to be captured simultaneously in each measurement. This simultaneous detection provides the theoretical SNR improvement for detector-noise-limited systems, as the integration time per spectral element is effectively multiplied by the number of spectral channels compared to sequential scanning instruments.

The magnitude of the multiplex advantage can be quantified by comparing the SNR of a Fourier transform spectrometer to that of a sequential scanning spectrometer with equivalent measurement time and optical throughput. For a system with M spectral elements where the dominant noise source is detector noise (independent of the signal), the multiplex advantage provides an SNR improvement of approximately √M [27]. This advantage becomes particularly significant in applications requiring high spectral resolution across broad bandwidths, where M can reach thousands of spectral elements. The theoretical framework also encompasses the Jacquinot advantage, which refers to the higher optical throughput of FTS instruments due to their elimination of narrow entrance slits required in dispersive systems [24]. Together, these advantages established FTS as the preferred technique for many infrared and millimeter-wave spectroscopic applications throughout the latter half of the 20th century.

Limitations and the Photon Noise Dilemma

The theoretical benefits of multiplexing confront fundamental physical limitations when applied to experimental systems with specific noise characteristics. The critical limitation emerges when photon noise (shot noise) becomes the dominant noise source rather than detector noise [27]. Photon noise represents the fundamental statistical fluctuation in photon arrival rates and follows a Poisson distribution, with variance proportional to the signal intensity. When a Fourier transform spectrometer measures a broadband source, the entire photon flux across all wavelengths contributes to the photon noise at the detector. During the mathematical reconstruction of the spectrum, this photon noise becomes distributed across all spectral channels, potentially degrading the SNR in each individual channel.

For measurements where photon noise dominates, the multiplex advantage can transform into a multiplex disadvantage. In such scenarios, the SNR of a Fourier Transform Spectrometer can be inferior to that of a dispersive instrument measuring the same source [26] [28]. This occurs because in a dispersive spectrometer with M channels, each channel receives only 1/M of the total photon flux, and consequently, only 1/M of the photon noise variance. The theoretical analysis reveals that for photon-noise-limited measurements, the SNR advantage of multiplexing disappears entirely unless the signal exhibits specific sparsity properties that can be exploited through computational methods [27]. This fundamental limitation has prompted the development of innovative spectrometer architectures that combine the benefits of FTS with alternative dispersion techniques to mitigate the photon noise penalty in broadband applications.

Table 1: Theoretical Conditions for Multiplex Advantage and Disadvantage

| Condition | Detector Noise Limited | Photon Noise Limited |

|---|---|---|

| Noise Characteristic | Signal-independent | Signal-dependent (√Signal) |

| Multiplex Effect | Advantage: SNR improvement of ~√M | Disadvantage: SNR degradation |

| Optimal Technique | Fourier Transform Spectrometry | Dispersive/Grating Spectrometry |

| Typical Applications | Low-light-level detection, Infrared spectroscopy | Bright source spectroscopy, Laser-based measurements |

Comparative Analysis of Spectrometer Architectures

Fourier Transform vs. Grating-Based Spectrometers

The performance differences between Fourier transform and grating-based spectrometer architectures become evident when examining their fundamental operational principles. Grating spectrometers employ diffractive elements to spatially separate wavelengths, typically requiring narrow entrance slits to achieve spectral resolution [24]. This slit-based design inherently limits optical throughput, creating a fundamental trade-off between resolution and signal intensity. In contrast, FTS instruments utilize an interferometric approach without entrance slits, permitting significantly higher optical throughput – the Jacquinot advantage – while simultaneously capturing the entire spectrum through multiplexing.

Experimental comparisons demonstrate that the superiority of either architecture depends critically on the noise regime of the measurement. For detector-noise-limited conditions in the long-wave infrared (LWIR, 8-14 μm) region, FTS systems demonstrate superior capability due to their higher optical throughput and multiplex advantage [24]. However, for photon-noise-limited conditions, grating-based systems can achieve superior SNR because they avoid the multiplex disadvantage. A notable experimental study comparing speckle-based imaging (SBI) and grating-based imaging (GBI) for X-ray phase contrast imaging revealed that while GBI provides excellent performance with structured patterns, SBI utilizes a simpler experimental setup without phase unwrapping issues and can simultaneously extract orthogonal differential phase gradients [17]. This illustrates how application-specific requirements can determine the optimal architectural choice.

Emerging Hybrid Architectures

Recent technological advances have led to the development of hybrid architectures that combine multiple spectroscopic principles to mitigate the limitations of individual approaches. One promising innovation is the filterbank-dispersed FTS (FBDFTS), which couples a medium-resolution FTS with a low-resolution filterbank spectrometer [29]. In this configuration, the FTS provides the spectral resolution while the filterbank serves as a post-dispersion element that physically separates the broadband light before detection. This architecture reduces the photon noise incident on each detector by over an order of magnitude while maintaining the imaging advantages of both architectures [29].

Another emerging approach addresses the multiplexing limitations through self-multiplexing with repetitive measurements using small-scale coding matrices. Unlike traditional Hadamard-transform spectrometry that relies on high-order coding matrices, this method performs multiple measurements with low-order matrices, significantly suppressing both photon and detector noise [27]. Experimental results demonstrate that with 32 repetitive measurements, this technique can improve SNR by approximately 10 dB in photon-noise-dominated measurements and 15 dB in detector-noise-dominated measurements – performance levels unattainable with traditional multiplexing approaches [27]. These hybrid architectures represent a promising direction for overcoming the fundamental limitations of conventional multiplexing while preserving its benefits in appropriate measurement regimes.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Spectrometer Architectures

| Architecture | Spectral Resolution | SNR Regime | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fourier Transform Spectrometer | High (0.1-1 cm⁻¹) [24] | Advantage in detector noise [27] | High (Jacquinot advantage) [24] | IR spectroscopy, Atmospheric monitoring [24] |

| Grating Spectrometer | High (λ/Δλ ~ 1000) [17] | Advantage in photon noise [27] | Limited by slit | UV-Vis spectroscopy, Laser analysis |

| Switch-based Digital FTS | Medium (Nλ²/ngΔL) [25] | Multiplex advantage for weak signals [25] | Moderate | Integrated photonics, Raman spectroscopy [25] |

| Filterbank-dispersed FTS | Medium (R ~ 1000) [29] | Reduced photon noise [29] | High | Astronomy, Sub-mm spectroscopy [29] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Testing Approaches

Systematic comparison of spectrometer architectures requires carefully controlled experimental protocols that isolate specific performance characteristics. For noise analysis, a standardized approach involves measuring signal-to-noise ratio as a function of input signal intensity across multiple orders of magnitude [16]. This protocol typically employs stable, calibrated light sources with adjustable intensity, with measurements performed under both detector-noise-limited conditions (very low light levels) and photon-noise-limited conditions (higher light levels). The experimental setup must carefully control for variables including integration time, spectral bandwidth, optical throughput, and detector characteristics to ensure valid comparisons between architectures.

For speckle-based versus grating-based spectrometer comparisons, a documented experimental protocol involves using a monochromatic source that is incrementally tuned across the operational bandwidth of both instruments [17]. The measured signal at each wavelength provides data for constructing the instrumental line shape function and quantifying chromatic aberrations. Another critical protocol involves measuring standard reference materials with known spectral features, such as the sulfur hexafluoride (SF₆) absorption peak at 10.6 μm used in LWIR spectrometer characterization [24]. These standardized testing approaches enable quantitative comparison of resolution, accuracy, sensitivity, and noise performance across different architectural platforms.

Advanced Noise Characterization Methods

Sophisticated noise characterization protocols have been developed specifically to quantify the multiplex advantage and its limitations. One method involves simultaneously measuring the interferogram domain SNR and the spectral domain SNR to experimentally validate theoretical predictions about noise transformation through the Fourier reconstruction process [26] [28]. This approach requires collecting multiple interferograms of both calibration sources and samples, followed by statistical analysis of both the raw interferogram points and the reconstructed spectral channels.

For comprehensive noise analysis, researchers have implemented protocols that systematically isolate different noise contributions. This typically involves measuring the noise power spectrum under various illumination conditions, distinguishing between signal-independent noise components (read noise, dark noise) and signal-dependent noise components (photon shot noise) [27]. Advanced implementations use covariance analysis to characterize noise correlations between spectral channels introduced by the multiplexing process [28]. These sophisticated protocols provide the experimental data necessary to validate theoretical models of multiplex advantage and establish boundaries for optimal application of Fourier transform spectrometry.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Spectrometer Characterization

| Material/Component | Function in Experimental Protocol | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Sulfur Hexafluoride (SF₆) Gas | Reference standard with sharp absorption at 10.6 μm [24] | LWIR spectrometer validation [24] |

| Mammographic Accreditation Phantom | Biomedical test sample with known structures [17] | Medical imaging performance evaluation [17] |

| Abrasive Paper (5μm particles) | Speckle pattern generation for SBI [17] | Wavefront measurement calibration [17] |

| Silicon Nitride (SiN) Waveguides | Low-loss photonic platform for on-chip spectroscopy [25] | Integrated spectrometer implementation [25] |

| Germanium (Ge) Photodetector | NIR detection with high responsivity (890-975 nm) [25] | Signal detection in Raman spectroscopy [25] |

| π Phase Grating (4μm period) | Beam splitter in grating interferometer [17] | X-ray phase contrast imaging [17] |

Visualization of Spectrometer Architectures and Principles

Fundamental Relationships in Multiplex Spectrometry

Hybrid Spectrometer Architecture

The multiplex advantage in Fourier transform systems represents a nuanced principle whose benefits depend critically on specific measurement conditions. While FTS provides significant SNR advantages in detector-noise-limited scenarios across broad spectral bandwidths, this advantage diminishes and can reverse in photon-noise-limited conditions. Experimental data confirms that the theoretical boundaries of multiplex advantage have practical significance in spectrometer selection and design. Emerging hybrid architectures that combine Fourier transform principles with complementary dispersion techniques offer promising pathways to mitigate these limitations while preserving the core benefits of multiplexing. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings underscore the importance of matching spectrometer architecture to specific application requirements, noise characteristics, and signal properties to optimize analytical performance.

Implementation and Use Cases in Biomedical Sensing

The pursuit of portable, high-performance Raman spectroscopy drives the development of novel spectrometer architectures. Traditional grating spectrometers (GS) have long been the industry standard, but spatial heterodyne spectrometers (SHS) are emerging as a competitive technology, particularly where miniaturization without a severe performance penalty is required. The following comparison guide objectively evaluates these two designs, focusing on their noise performance and operational characteristics, to inform researchers and development professionals in their instrument selection process.

Instrument Operational Principles

Grating Spectrometer (GS) Fundamentals

Grating spectrometers operate on the principle of spatial dispersion. A diffraction grating spatially separates the spectral components of the incoming light, which are then directly mapped onto different pixels of a detector array [15]. The entrance slit is a critical component that defines the spectral resolution; however, it also limits the optical throughput (etendue) of the system, creating a fundamental trade-off between resolution and light-gathering capability [30].

Spatial Heterodyne Spectrometer (SHS) Fundamentals

SHS is a type of static Fourier transform spectrometer based on a modified Michelson interferometer, where the traditional mirrors are replaced by two stationary diffraction gratings [31] [32]. It produces a two-dimensional interferogram on a detector array, which is then converted into a spectrum via Fourier transformation [31]. A key advantage is its operation without an entrance slit, which provides it with a significantly larger etendue—often 10 to 100 times greater than a comparable GS [15].

Performance Comparison and Noise Analysis

The performance of a Raman spectrometer is critically assessed by its Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), which directly impacts the reliability and accuracy of spectral data [33]. The dominant noise sources are typically photon shot noise, dark current noise, and read-out noise [15].

Analytical SNR Models

A generic analytical model for comparing GS and SHS performance reveals that the ratio of their SNRs (R_SNR) can vary by up to two orders of magnitude, depending on the spectral characteristics of the Raman light and instrument-specific parameters [15].

- Grating Spectrometer SNR: In a GS, the signal for a specific wavelength is concentrated on a few pixels. Its SNR is derived from the direct measurement of spectral radiance [33].

- Spatial Heterodyne Spectrometer SNR: In an SHS, the signal is multiplexed across the entire detector via the interferogram. The shot noise from the entire input spectrum is distributed across the reconstructed spectrum [15] [33].

Key Performance Trade-offs

The core trade-off between these technologies stems from the Fellgett's (multiplex) Advantage and the Jacquinot's (throughput) Advantage inherent to Fourier transform techniques, but their benefit is nuanced in the context of Raman spectroscopy.

- Throughput Advantage: The absence of an entrance slit gives SHS a fundamental etendue advantage (10-100x higher than GS), allowing it to collect more light from a given source [15] [30].

- Multiplex Disadvantage: In shot-noise-limited regimes common with Raman spectroscopy, the multiplexing nature of SHS means the shot noise from the entire spectrum (including strong background signals) is distributed across all spectral elements. This can offset the Fellgett's advantage, which primarily benefits detector-noise-limited applications [15] [33].

Table 1: Direct Performance Comparison of Grating and Spatial Heterodyne Spectrometers

| Performance Parameter | Grating Spectrometer (GS) | Spatial Heterodyne Spectrometer (SHS) | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Etendue (Optical Throughput) | Lower (limited by entrance slit) [15] [30] | 10 to 100 times higher (no entrance slit) [15] [30] | Comparative theoretical analysis [15] |

| Spectral Resolution | 1.37 cm⁻¹ (modular dispersive) [31] | 1.37 cm⁻¹ (E-SHTRS) [34], 1.23 cm⁻¹ (simulated) [32] | Measurement of calcite, quartz [31]; System design simulation [32] |

| Single-Acquisition Spectral Range | Limited, requires scanning [32] | 6314 cm⁻¹ (9 levels of echelle grating) [34], [577.3, 745.8] nm [32] | Echelle grating SHS design [34]; Dual-grating SHS prototype [32] |

| Footprint | Larger for equivalent resolution [15] | 10-30 times smaller footprint [15] [31] | Monolithic device ~35 mm, <100 g [31] |

| Relative SNR (Typical) | Benchmark | 5 to 10 times poorer than GS, but in a much smaller footprint [15] [35] | Noise analysis under shot-noise dominance [15] |

| Dominant Noise Regime | Shot noise on target signal [15] | Shot noise from entire input spectrum, including strong background [15] [33] | Analytical model and experimental validation [15] [33] |

Performance in Different Spectral Regimes

The relative performance is highly dependent on the nature of the Raman spectrum being measured [15]:

- Isolated Raman Line with High Background: When the background signal (e.g., from fluorescence) is comparable to or larger than the target Raman line, the SHS experiences a more significant SNR penalty due to the multiplex disadvantage. In this regime, the

R_SNRis primarily dependent on the relative etendue and the number of detector pixels [15]. - Complex, Multi-Component Spectra with Low Background: For spectra rich in Raman lines but with minimal background, the performance gap between SHS and GS narrows. The high etendue of the SHS can be more fully leveraged in this scenario [15].

Experimental Protocols and Validation

SNR Model Validation Protocol

A recent study established a novel SHS SNR model and validated it through a controlled experiment [33]:

- Apparatus: A self-developed SHS with 1000 sampling points and an integrating sphere as a stable light source.

- Data Acquisition: 50 interferograms were collected continuously under constant light intensity and integration time.

- Noise Calculation: The standard deviation of the 50 measurements at each sampling point was calculated as the noise, while the mean value was taken as the interference signal.

- Spectral Recovery: The interferogram was Fourier transformed to obtain the spectrum, and the noise in the spectral domain was analyzed to validate the theoretical model [33].

Mineral Spectroscopy Application Protocol

The practical application of SHRS for mineral analysis demonstrates its real-world performance [31]:

- Sample Preparation: Mineral samples (e.g., calcite in marble, forsterite in nickel ore) are prepared as flat, polished sections or pure fragments.

- Instrumentation: A broadband SHRS instrument (518–686 nm) with a resolving power of R≈3000 is used. A 532 nm laser is a typical excitation source.

- Measurement: The laser is focused onto the sample. The scattered light is collected, passed through a Bragg notch filter to suppress Rayleigh scattering, and directed into the SHRS.

- Data Processing: The recorded 2D interferogram is processed (apodization, phase correction) and Fourier transformed to retrieve the Raman spectrum.

- Benchmarking: The resulting spectra are compared against those acquired from benchtop and modular dispersive spectrometers for resolution and sensitivity assessment [31].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit - Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Echelle Grating | High-dispersion element in SHS; enables wide spectral range and high resolution [34]. | 36 gr/mm; provides multi-level diffraction [34]. |

| Reflective Blazed Grating | Standard diffraction element for dispersing light in GS or as a component in SHS [32]. | 300 lp/mm, blaze wavelength 500 nm [32]. |

| Bragg Notch Filter (BNF) | Critical for rejecting the intense Rayleigh scattered laser line while transmitting the weaker Raman signal [34]. | Tilted at a specific angle to the optical axis [34]. |

| Beam Splitter Prism (BS) | Splits the incoming light beam into two paths in an SHS interferometer [31] [32]. | 25 mm clear aperture (e.g., Thorlabs BS013) [32]. |

| Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) Camera | Detector for capturing either the dispersed spectrum (GS) or the interference fringes (SHS) [15] [34]. | Linear or area array; used in full vertical binning mode for GS [15]. |

| Standard Calibration Source | For wavelength calibration of the spectrometer [32]. | Neon lamp with known emission lines (e.g., Ocean Insight Neon Calibration Source) [32]. |

The choice between grating and spatial heterodyne spectrometer designs for Raman spectroscopy involves a critical trade-off between performance, size, and application context.

Grating spectrometers remain the robust, high-SNR choice for laboratory-based applications where footprint is not a primary constraint. Their performance is more predictable and less susceptible to degradation from fluorescent backgrounds.

Spatial heterodyne spectrometers offer a compelling alternative for field-portable, handheld, or resource-limited applications (e.g., planetary rovers, process control) where their miniaturization, high etendue, and inherent stability are paramount. While their SNR is typically lower, it remains competitive for many applications, especially those involving complex spectra with low background [15] [31].

Future research is focused on mitigating the multiplex disadvantage of SHS, further improving its SNR through advanced designs like cross-dispersed architectures [33] and optimizing data processing algorithms [30]. The ongoing development underscores SHS's potential to provide high-quality Raman data from increasingly compact and robust field-deployable instruments.

Spectrometers are indispensable tools across scientific and industrial fields, from chemical analysis to drug development. The long-standing demand for miniaturized devices has spurred innovation in integrated photonics. Among the most promising advancements are speckle-based spectrometers, which leverage the interference patterns generated by light propagating through disordered media to encode spectral information. This guide objectively compares two primary implementations of this technology: multimode optical fibers and on-chip diffractive metasurfaces. Framed within a broader thesis comparing grating-based and speckle-based spectrometer noise performance, we dissect their setups, performance metrics, and calibration protocols to inform researchers and scientists in selecting the appropriate tool for their applications.

Traditional grating-based spectrometers (GBI) operate on the principle of spatial dispersion, where different wavelengths of light are angularly separated using a diffraction grating. While capable of high performance, their miniaturization is challenging due to the need for long optical paths to achieve high resolution.

Speckle-based spectrometers present a paradigm shift. Instead of separating wavelengths, they employ a disordered medium—such as a multimode fiber or a metasurface—to create a wavelength-dependent speckle pattern, or "fingerprint," on a camera. A pre-calibrated transmission matrix then reconstructs the unknown input spectrum from this pattern [36] [37]. The key advantage lies in their compactness, as high resolution is achieved through the interference of many guided modes over a short distance, not a long physical path.

Experimental Setups and Methodologies

Multimode Fiber Spectrometer

Core Components and Function: This setup leverages a standard multimode optical fiber as the disordered medium. Light injected into the fiber excites numerous guided modes. These modes interfere with one another as they propagate, creating a complex speckle pattern at the output. Since the relative phase velocities of these modes are wavelength-dependent, any change in the input wavelength results in a completely different speckle pattern [36] [37].

Calibration and Reconstruction Protocol:

- System Calibration: The system is calibrated by inputting light from a tunable laser with a known, narrow-linewidth wavelength, (\lambda). The resulting speckle pattern, (I(\lambda)), is recorded for each wavelength across the desired operational bandwidth. This dataset is used to construct a transmission matrix, (T(\lambda)), which maps spectral components to spatial intensity patterns.

- Spectrum Measurement: For an unknown input spectrum, the resulting speckle pattern, (I_{meas}), is recorded.

- Spectrum Reconstruction: The unknown spectrum, (S(\lambda)), is reconstructed by solving the linear equation (I_{meas} = T \cdot S) using computational algorithms, even in the presence of experimental noise [36]. Advanced implementations can image orthogonal polarizations separately to reduce reconstruction error and increase bandwidth [36].

The following diagram illustrates the core operational principle and calibration workflow.

On-Chip Metasurface Spectrometer

Core Components and Function: This implementation integrates the disordered medium directly onto a photonic chip. A typical design, as demonstrated in a 2025 study, consists of an input single-mode waveguide, collimating metalenses, and multiple cascaded layers of diffractive metasurfaces [2]. These metasurfaces are patterned with random "meta-atoms" (e.g., etched waveguide slots of varying lengths) that impose a disordered phase profile on the transmitted light. This process generates a wavelength-dependent speckle pattern, which is then imaged via a multimode output grating coupler onto a camera [2].

Calibration and Reconstruction Protocol: The fundamental calibration and reconstruction process is similar to the fiber-based system but operates in a highly integrated, scaled architecture.

- Matrix Calibration: The transmission matrix (T(\lambda)) of the entire on-chip system is characterized by measuring the speckle response across a range of known wavelengths.

- Scalable Architecture: The spectral richness and number of available channels are greatly increased by scaling the architecture to multiple (e.g., three) cascaded metasurface layers. This increases the effective interference path length, creating more complex and wavelength-sensitive speckle patterns [2].

- Computational Reconstruction: As with the fiber system, unknown spectra are reconstructed by solving (I_{meas} = T \cdot S). The large number of spectral channels encoded in the speckle pattern from the cascaded metasurfaces enables high resolution over a broad bandwidth [2].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and experimental data for the two speckle spectrometer setups, alongside a reference for traditional grating-based spectrometers for context.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Spectrometer Technologies

| Technology | Spectral Resolution | Bandwidth | Footprint | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multimode Fiber [36] [37] | 8 pm (20 m fiber) | 5 - 25 nm | Meters of fiber | Resolution scales with fiber length |

| 0.03 nm (5 m fiber) | ||||

| On-Chip Metasurface [2] | 70 pm | 100 nm | 150 μm × 950 μm | Channel Density: 10,021 ch/mm² |

| Grating-Based (Reference) | High (path-dependent) | Broad | Large (cm to m) | Mature technology |

Table 2: Experimental Protocols and Noise Performance

| Aspect | Multimode Fiber Spectrometer | On-Chip Metasurface Spectrometer |

|---|---|---|

| Core Disordered Medium | Standard multimode optical fiber [36] | Cascaded layers of disordered metasurfaces [2] |

| Key Components | Fiber spool, imaging camera | Input waveguide, metalenses, metasurfaces, grating coupler |

| Calibration Method | Measure speckle pattern vs. wavelength to build transmission matrix [36] | Measure speckle pattern vs. wavelength to build transmission matrix [2] |

| Noformance Profile | Comparable to grating spectrometer for intense/narrowband signals; accuracy degrades for weak/broadband signals [16] | High channel density and integration; full noise analysis specific to this architecture is an area for further study |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Components for Speckle Spectrometer Experiments

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Multimode Optical Fiber | A standard fiber used as the random scattering medium; its length dictates the resolution [36]. | Core element in fiber-based speckle spectrometers. |

| Disordered Metasurface | An on-chip surface with randomly distributed meta-atoms (e.g., waveguide slots) that create the spectral fingerprint [2]. | Core element in integrated, chip-scale speckle spectrometers. |

| Tunable Laser Source | A laser capable of emitting precise, discrete wavelengths across a range. Essential for system calibration [36] [2]. | Used to build the transmission matrix during calibration. |

| High-Resolution Camera | A 2D imaging sensor (e.g., CCD or CMOS) used to record the speckle patterns for both calibration and measurement. | Required for imaging the output speckle in all setups. |

| Transmission Matrix | A pre-calibrated mathematical model that stores the relationship between wavelength and speckle pattern [36]. | Used in the computational reconstruction of unknown spectra. |

The experimental data reveals a clear trade-off between the classical flexibility of multimode fiber setups and the superior integration of modern metasurface devices. Fiber-based spectrometers offer exceptionally high resolution, which can be tuned by simply changing the fiber length, making them excellent for high-precision laboratory experiments. However, their footprint is inherently large, and they are susceptible to environmental perturbations and performance degradation with weak or broadband signals [16].

In contrast, on-chip metasurface spectrometers represent the cutting edge of miniaturization. Their ability to cascade multiple disordered layers on a tiny footprint achieves a benchmark channel density, delivering high resolution across a broad bandwidth in a form factor suitable for portable devices and system-on-chip integration [2].

Conclusion for Drug Development Professionals: The choice between these technologies hinges on application-specific requirements. For benchtop analysis where maximum resolution is paramount and size is not a constraint, a multimode fiber spectrometer is a powerful, cost-effective option. However, for applications demanding portability, ruggedness, and integration into larger lab-on-a-chip systems—such as point-of-care diagnostics or in-line process analytical technology (PAT)—the on-chip metasurface spectrometer, despite its greater fabrication complexity, is the unequivocal leader. This comparison underscores that speckle-based spectrometry has matured into a versatile field, offering solutions that can be tailored from the research bench to the field.