Non-Destructive Spectroscopic Analysis: Principles, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of non-destructive spectroscopic analysis, detailing its foundational principles and its transformative role in modern biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Non-Destructive Spectroscopic Analysis: Principles, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of non-destructive spectroscopic analysis, detailing its foundational principles and its transformative role in modern biomedical and pharmaceutical research. It covers core methodologies from IR to NMR spectroscopy, illustrates applications in real-time quality control and metabolite detection, and addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for complex samples. By presenting validation frameworks and comparative analyses of techniques, this guide serves as an essential resource for scientists and drug development professionals seeking to implement robust, efficient, and reliable analytical methods that preserve sample integrity and accelerate discovery.

The Core Principles of Non-Destructive Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectroscopy constitutes a fundamental scientific technique for investigating the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter [1]. Non-destructive spectroscopy specifically refers to analytical methods that allow for the characterization of a material's composition, structure, and physical properties without altering its functionality or integrity [2]. The core principle rests on the quantum mechanical phenomenon where atoms and molecules absorb or emit photons at discrete wavelengths when transitioning between energy levels, creating a unique spectral fingerprint for every substance [1] [3]. The energy involved in these transitions is described by the equation (E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda}), where (E) is energy, (h) is Planck's constant, (\nu) is frequency, (c) is the speed of light, and (\lambda) is wavelength [3].

The non-destructive nature of these techniques makes them indispensable across fields where sample preservation is critical, including pharmaceutical development, cultural heritage conservation, and environmental monitoring [2] [4]. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of non-destructive spectroscopic analysis within the broader context of analytical research.

Fundamental Principles and Techniques

Non-destructive spectroscopic techniques probe different energy transitions within materials, providing complementary information about elemental composition, molecular structure, and chemical bonds.

Light-Matter Interaction Mechanisms

The interaction between incident light and a material can occur through several mechanisms, each forming the basis for different spectroscopic methods:

- Absorption: Occurs when photon energy matches the energy required for a molecular or atomic transition (e.g., electronic, vibrational). The measurement of absorbed wavelengths forms the basis for techniques like UV-Vis and IR spectroscopy [1].

- Elastic Scattering: The photon is deflected without energy change, as in Rayleigh scattering.

- Inelastic Scattering: The photon undergoes both direction and energy change, providing information about vibrational modes, as utilized in Raman spectroscopy [3].

- Emission: Excited atoms or molecules release energy as photons when returning to lower energy states, measured in techniques like fluorescence spectroscopy [1].

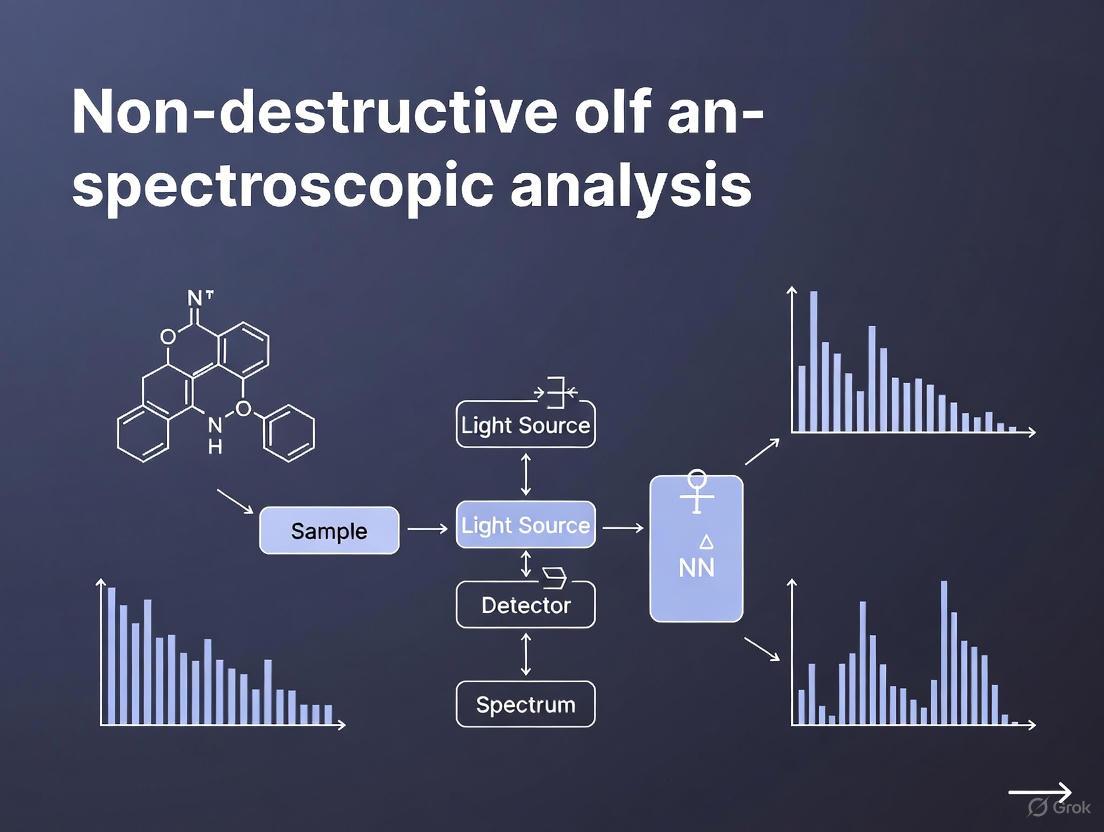

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental processes in non-destructive spectroscopy:

Major Non-Destructive Spectroscopic Techniques

Table 1: Key Non-Destructive Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Spectral Region | Measured Transition | Primary Information | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Visible Spectroscopy [5] [6] | Ultraviolet-Visible (190-800 nm) | Electronic transitions | Concentration, size of nanoparticles | Pharmaceutical quantification, nanoplastic analysis |

| Infrared Spectroscopy [2] [7] | Mid-infrared (4000-400 cm⁻¹) | Molecular vibrations | Functional groups, molecular structure | Polymer analysis, pharmaceutical formulation |

| Raman Spectroscopy [4] [3] | Visible, NIR, or UV | Inelastic scattering | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure | Pigment identification, material characterization |

| X-ray Fluorescence [4] | X-ray region | Core electron transitions | Elemental composition | Cultural heritage, material science |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance [1] | Radio frequency | Nuclear spin transitions | Molecular structure, dynamics | Drug development, biochemistry |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Quantitative Analysis of Nanoplastics Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy

The following protocol, adapted from environmental nanoplastic research, demonstrates a specific application of UV-Vis spectroscopy for quantifying true-to-life nanoplastics in suspension [5]:

Principle: This method leverages the absorbance characteristics of polystyrene nanoplastics in UV-Vis range to determine concentration in stock suspensions, providing a rapid, non-destructive alternative to mass-based techniques.

Materials and Equipment:

- Microvolume UV-Vis spectrophotometer

- Polystyrene test nanoplastics (generated from fragmented plastic items)

- MilliQ water

- Ultracentrifugal mill (e.g., ZM 200, Retsch GmbH)

- Laboratory centrifuge

- Microvolume measurement cells

Procedure:

- Nanoplastic Preparation:

- Select white, unpigmented polystyrene disposable objects to avoid pigment interference.

- Mechanically fragment selected PS objects using an ultracentrifugal mill operating under cryogenic conditions to obtain a micrometric powder.

- Separate polystyrene nanoplastics (PS NPs) from microplastics by suspending PS powder in MilliQ water (ratio: 0.1 g PS powder: 30 mL MilliQ water).

- Perform sequential centrifugations to isolate the final pellets of PS NPs.

Instrument Calibration:

- Power on the UV-Vis spectrophotometer and allow it to warm up for 30 minutes.

- Establish a calibration curve using commercial polystyrene nanobeads of known sizes (100 nm, 300 nm, 600 nm, 800 nm, and 1100 nm diameter) and concentrations.

Sample Measurement:

- Load the microvolume sample cell with 1-2 μL of the NP suspension using appropriate pipetting techniques.

- Place the sample cell in the spectrophotometer and ensure proper alignment.

- Scan absorbance from 200-800 nm with a resolution of 1 nm.

- Perform triplicate measurements for each sample to ensure reproducibility.

Data Analysis:

- Determine concentration by comparing sample absorbance values at characteristic wavelengths against the calibration curve.

- Apply appropriate dilution factors if necessary to ensure measurements fall within the linear range of the calibration curve.

Validation: Compare UV-Vis quantification results with mass-based techniques like pyrolysis gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Py-GC/MS) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), or number-based methods like nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) to verify accuracy and establish method reliability [5].

Protocol for Pigment Analysis in Cultural Heritage Using XRF

This protocol outlines the non-destructive analysis of pigments on architectural heritage using X-ray Fluorescence spectroscopy [4]:

Principle: XRF identifies elements present in pigments by detecting characteristic X-rays emitted when the sample is irradiated with high-energy X-rays, enabling qualitative and semi-quantitative elemental analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable XRF spectrometer (with X-ray tube and detection system)

- Sample positioning stage

- Calibration standards

- Optional: helium purge system for light element detection

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation:

- Visually inspect the analysis area and document with photography.

- If using laboratory-based XRF systems, minimal surface cleaning may be required to enhance sensitivity, though this should be approached cautiously with fragile heritage materials.

- Position the artwork or sample securely to prevent movement during analysis.

Instrument Setup:

- Select appropriate measurement parameters based on expected elements (voltage, current, filter selection).

- Set measurement time typically between 10-300 seconds depending on required detection limits.

- Perform energy calibration using certified standards.

Data Collection:

- Position the XRF spectrometer probe perpendicular to and in gentle contact with the sample surface.

- Acquire spectra from multiple points on each color region to account for heterogeneity.

- Include adjacent areas to establish background signals.

Data Interpretation:

- Identify elements present by matching characteristic X-ray peaks in the spectrum.

- Correlate elemental composition with known pigment formulations (e.g., Hg and S for vermilion; Cu for azurite, malachite).

- Combine with complementary techniques like FTIR or Raman spectroscopy for complete pigment identification.

Limitations: XRF is primarily surface-sensitive (penetration depth typically <100 μm) and cannot detect elements lighter than sodium with conventional instruments. For layered paint systems, the technique provides elemental information from all layers penetrated by the X-rays, which may complicate interpretation [4].

Advanced Applications and Integration

Machine Learning-Enhanced Spectroscopy

The integration of machine learning with non-destructive spectroscopy has significantly advanced analytical capabilities, particularly for complex material systems:

Plasticizer Identification in Cultural Heritage: Researchers have successfully combined ATR-FTIR and NIR spectroscopy with machine learning algorithms to identify and quantify plasticizers in historical PVC objects without destructive sampling [7]. The study utilized six different classification algorithms (Linear Discriminant Analysis, Naïve Bayes Classification, Support Vector Machines, k-Nearest Neighbors, Decision Trees, and Extreme Gradient Boosted Decision Trees) to identify common plasticizers including DEHP, DOTP, DINP, and DIDP based solely on spectroscopic data.

Quantitative Modeling: Beyond identification, regression models built from spectroscopic data enable quantification of specific components. For plasticizer analysis, models were developed to quantify DEHP and DOTP concentrations in PVC, providing conservators with essential information for preservation strategies without damaging historically valuable objects [7].

Pharmaceutical Applications

Non-destructive spectroscopic techniques have transformed pharmaceutical development and quality control through:

Real-Time Release Testing (RTRT): Spectroscopy enables RTRT frameworks where quality assurance is performed during manufacturing using non-destructive methods like NIR spectroscopy instead of end-product testing [2]. This approach allows continuous process verification and quicker release times while maintaining quality standards.

Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Implementation of spectroscopic PAT tools enables in-line monitoring of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs) during pharmaceutical manufacturing, allowing immediate corrective actions when unusual trends are detected [2]. This aligns with Quality by Design (QbD) principles promoted by regulatory agencies.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Nanobeads [5] | Calibration standards for size and concentration quantification | UV-Vis spectroscopy of nanoplastics; nanoparticle tracking analysis |

| ATR Crystals (diamond, germanium) [7] | Internal reflection element for sample contact | FTIR spectroscopy of polymer surfaces; plasticizer identification |

| Calibration Standards [4] | Quantitative elemental analysis reference materials | XRF spectroscopy of pigments and cultural materials |

| MilliQ Water [5] | High-purity suspension medium for nanomaterial preparation | Sample preparation for environmental nanoplastic research |

| Reference Pigments [4] | Known composition materials for method validation | Cultural heritage analysis; archaeological material characterization |

Comparative Analysis and Technical Considerations

Method Selection Guide

The following workflow diagram illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate non-destructive spectroscopic techniques based on analytical requirements:

Advantages and Limitations

Non-destructive spectroscopic techniques offer significant benefits but also present specific constraints that researchers must consider:

Advantages:

- Sample Preservation: Techniques do not alter the chemical state of materials during measurement, enabling repeated testing and preserving valuable samples [1] [2].

- Rapid Analysis: Most measurements are completed within seconds to minutes (e.g., XRF analysis takes 10-300 seconds for full elemental analysis) [4].

- Minimal Sample Preparation: Unlike destructive methods, most non-destructive techniques require little to no sample preparation, reducing analysis time and potential artifacts [2] [4].

- In-situ Capability: Many modern spectroscopic instruments are portable, allowing for field analysis of materials that cannot be transported to laboratories [4].

Limitations:

- Sensitivity Constraints: Some techniques may have higher detection limits compared to destructive methods, potentially missing trace components [5].

- Spectral Interpretation Complexity: Overlapping signals from complex mixtures may require advanced chemometric analysis for proper interpretation [2] [7].

- Matrix Effects: The surrounding material can influence spectral signals, potentially complicating quantitative analysis without appropriate calibration [5].

- Technique-Specific Restrictions: For example, XRF cannot detect elements lighter than sodium, and Raman spectroscopy may suffer from fluorescence interference in certain materials [4].

Non-destructive spectroscopy represents a cornerstone of modern analytical science, enabling detailed material characterization while preserving sample integrity. The interaction of light with matter provides a rich information source about composition, structure, and properties across diverse applications from pharmaceutical development to cultural heritage conservation. As spectroscopic instrumentation advances and integrates with machine learning and computational methods, the capabilities for non-destructive analysis continue to expand, offering increasingly sophisticated tools for scientific research and industrial applications. The continued refinement of these techniques ensures they will remain essential for non-invasive material characterization across scientific disciplines.

Spectroscopic analysis has emerged as a cornerstone technique in modern analytical laboratories, particularly valued for its non-destructive nature. This whitepaper examines the three fundamental advantages of spectroscopic methods—analytical speed, cost-efficiency, and sample integrity preservation—within the broader context of non-destructive analysis. By integrating recent technological advancements with practical applications, we demonstrate how these techniques deliver rapid, economically viable, and sample-preserving analysis crucial for pharmaceutical development and scientific research. The data presented establishes spectroscopy as an indispensable methodology where sample preservation and operational efficiency are paramount.

Spectroscopic methods are essential for characterizing materials because they provide critical information about physical, chemical, and structural properties while preserving sample integrity [8]. The non-destructive nature of these techniques stems from their fundamental principle: measuring the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter without consuming or permanently altering the sample [8]. Recent advances have significantly enhanced our ability to investigate complex systems more precisely and effectively, making spectroscopy particularly valuable for applications where sample preservation is essential, such as forensic analysis, rare sample investigation, and pharmaceutical development [8].

The global demand for minerals and materials, driven by expanding sectors like advanced materials, electronics, and renewable energy, has further accelerated the adoption of non-destructive spectroscopic techniques [8]. These methods provide unparalleled opportunities for mineral discovery and characterization while maintaining sample integrity for future analysis or archival purposes. The ongoing development of spectroscopic instrumentation and methodology continues to bridge the gap between fundamental research and commercial applications, highlighting the critical function of spectroscopy in modern scientific investigation.

Speed Advantages in Spectroscopic Analysis

Rapid Analysis Capabilities

The speed of spectroscopic analysis represents one of its most significant advantages over traditional wet chemical methods. Techniques such as laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS) enable real-time analysis capabilities that are invaluable for both laboratory and field applications [8]. This rapid analysis potential is further enhanced by the minimal sample preparation requirements for many spectroscopic techniques, allowing researchers to move directly from sample collection to data acquisition without time-consuming preparation steps.

Near-infrared (NIR) spectroscopy has particularly emerged as a rapid analysis technology, with its non-destructive, non-invasive, chemical-free characteristics enabling fast analysis possibilities for a wide range of materials [9] [10]. The technology's advancement in instrumentation and computing power has facilitated its establishment as a quality control method of choice for numerous applications where analytical speed is essential. The integration of multivariate data analysis with NIR spectroscopy has maintained this speed advantage while enhancing analytical precision and accuracy.

High-Throughput Screening Applications

In pharmaceutical development and research settings, spectroscopic methods enable high-throughput screening that dramatically accelerates analytical workflows. The combination of spectroscopy with automation systems allows for continuous analysis of multiple samples with minimal operator intervention, significantly increasing laboratory efficiency. This automated approach is particularly valuable in quality control environments where large numbers of samples must be analyzed within tight time constraints.

Recent developments in hyperspectral imaging have extended these speed advantages by providing spectral data as a set of images, each representing a narrow wavelength range or spectral band [9] [10]. This technology adds a spatial dimension to traditional spectroscopy, enabling simultaneous analysis of multiple sample areas without sacrificing analytical speed. The capacity to obtain both identification and localization of chemical compounds in non-homogeneous samples in a single rapid measurement represents a significant advancement in analytical efficiency.

Data Processing and Real-Time Analysis

Modern spectroscopic systems integrate advanced data processing capabilities that further enhance their speed advantages. The application of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to spectroscopic data has revolutionized interpretation processes, enabling faster and more accurate assessment of samples [8]. These computational approaches can identify patterns and relationships in complex spectral data that might elude manual interpretation, accelerating both qualitative and quantitative analysis.

The implementation of real-time analysis capabilities, particularly in field-deployable instruments, has transformed many analytical scenarios. Portable Raman and LIBS systems now provide immediate compositional information during field studies, eliminating the delay between sample collection and laboratory analysis [8]. This instantaneous feedback enables researchers to make informed decisions promptly, optimizing sampling strategies and enabling rapid on-site assessment of material properties.

Table 1: Speed Comparison of Spectroscopic Techniques Versus Traditional Methods

| Analytical Technique | Typical Analysis Time | Sample Throughput (per hour) | Sample Preparation Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| NIR Spectroscopy | 30-60 seconds | 60-120 | Minimal to none |

| Raman Spectroscopy | 1-2 minutes | 30-60 | None |

| LIBS | 10-30 seconds | 120-360 | Minimal |

| XRF Spectroscopy | 2-5 minutes | 12-30 | Minimal (pellet preparation possible) |

| Traditional Wet Chemistry | 30-60 minutes | 1-2 | Extensive |

| HPLC/GC | 15-30 minutes | 2-4 | Significant |

Cost-Efficiency of Spectroscopic Methods

Reduced Consumables and Reagent Requirements

Spectroscopic methods offer significant cost advantages through their minimal requirements for consumables and reagents. Unlike many traditional analytical techniques that require extensive chemical reagents, solvents, and disposable labware, spectroscopic analysis typically needs little beyond the sample itself [9] [10]. This reduction in consumable usage not only lowers direct costs but also minimizes the environmental impact associated with chemical waste disposal, contributing to more sustainable laboratory operations.

The economic benefits of this approach are particularly evident in high-volume analytical environments where traditional methods would require substantial ongoing investment in reagents and disposables. NIR spectroscopy exemplifies this advantage, as it eliminates the need for chemicals and avoids producing chemical waste, unlike reference methods such as gas chromatography (GC) and high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [10]. This characteristic makes spectroscopy particularly valuable in resource-limited settings or applications where cost containment is essential.

Labor Efficiency and Operational Costs

The streamlined workflows associated with spectroscopic analysis translate directly into reduced labor requirements and lower operational costs. Minimal sample preparation decreases the technician time needed for each analysis, while automated operation allows staff to focus on data interpretation rather than manual analytical procedures. This labor efficiency creates significant cost savings, particularly in environments with high personnel costs or where large sample volumes must be processed.

Instrument design and maintenance requirements also contribute to the cost-efficiency of spectroscopic methods. As noted in comparative analyses, Raman instrumentation typically exhibits reasonable cost with high signal-to-noise ratio performance [11]. Similarly, NIR spectrophotometers generally present lower instrumentation costs compared to IR spectrophotometers, making the technology accessible to a broader range of laboratories and applications [11]. These favorable cost profiles have accelerated the adoption of spectroscopic techniques across diverse analytical scenarios.

Long-Term Economic Benefits

The non-destructive nature of spectroscopic analysis generates substantial long-term economic benefits by preserving samples for additional testing or archival purposes. In pharmaceutical development, where sample materials may be rare, expensive, or difficult to synthesize, this preservation capability represents significant value. Saved samples can be reanalyzed using the same or complementary techniques, used in additional studies, or retained as reference materials, maximizing the return on investment in sample creation and acquisition.

The combination of spectroscopy with computational approaches creates additional economic advantages by extending analytical capabilities without requiring corresponding investments in physical instrumentation. Chemometric mathematical data processing enables calibration for qualitative or quantitative analysis despite apparent spectroscopic limitations, particularly for NIR spectra consisting of generally overlapping vibrational bands that are non-specific and poorly resolved [11]. This computational enhancement allows laboratories to extract maximum value from existing instrumentation, further improving the cost-efficiency of spectroscopic methods.

Table 2: Cost Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

| Cost Factor | Traditional Wet Chemistry | Spectroscopic Methods | Cost Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent/Consumable Cost per Sample | $15-50 | $0-5 | 70-100% |

| Labor Time per Sample | 45-90 minutes | 5-15 minutes | 70-90% |

| Waste Disposal Cost | Significant | Minimal to none | 90-100% |

| Initial Instrument Investment | Moderate | Moderate to high | N/A |

| Long-Term Operational Cost | High | Low | 60-80% |

Sample Integrity Preservation

Non-Destructive Analytical Principles

The fundamental principles of spectroscopy ensure sample integrity preservation by utilizing non-destructive interactions between electromagnetic radiation and matter. As described in recent advances in spectroscopic techniques for mineral characterization, these methods provide important information about physical, chemical, and structural characteristics without consuming or destroying the sample [8]. This non-destructive approach contrasts sharply with many analytical techniques that require sample dissolution, digestion, or other irreversible modifications.

Different spectroscopic techniques employ various mechanisms to preserve sample integrity. NIR spectroscopy, for example, uses shorter wavelengths (800-2500 nm) compared to the mid-infrared (MIR) range (2500-15,000 nm), enabling increased penetration depth and subsequent non-destructive, non-invasive analysis [9] [10]. Similarly, Raman spectroscopy can be used for a variety of measurements on samples that are aqueous in nature or where glass sample holders are present without affecting sample integrity [11]. These non-destructive characteristics make spectroscopic methods particularly valuable for analyzing irreplaceable or historically significant materials.

Minimal Sample Preparation Requirements

The minimal sample preparation required for spectroscopic analysis directly contributes to sample integrity preservation by avoiding potentially destructive preparation steps. Techniques such as grinding, dissolving, or extensive purification—common in traditional analysis—are unnecessary for many spectroscopic applications [12]. This reduction in sample manipulation minimizes opportunities for contamination, degradation, or accidental loss of sample material.

As outlined in guides for sample preparation for spectroscopy, proper handling is crucial for maintaining sample integrity [12]. The non-destructive nature of spectroscopy aligns perfectly with these preservation goals, as most samples require no preparation beyond being appropriately presented to the instrument. For solid samples, this might involve simple placement in a sample holder, while liquids might require only transfer to an appropriate container [12]. This straightforward approach contrasts with the extensive preparation required for techniques like HPLC or traditional wet chemistry, where samples often undergo significant modification before analysis.

Applications Requiring Sample Preservation

The sample preservation capabilities of spectroscopic methods make them particularly valuable for specific applications where material integrity is paramount. In pharmaceutical development, active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and formulation prototypes can be analyzed without consumption, preserving valuable materials for additional testing or reference purposes. Similarly, in forensic science, evidence preservation is essential for legal proceedings, making non-destructive analysis critically important.

Cultural heritage and archeological applications also benefit tremendously from the sample-preserving characteristics of spectroscopy. Historically significant artifacts, artworks, and documents can be analyzed without damage or alteration, providing valuable information about composition, provenance, and age while preserving these irreplaceable items for future study and appreciation. The capacity to obtain detailed chemical and structural information without physical sampling has revolutionized the analysis of cultural materials, enabling insights that were previously impossible without destructive testing.

Experimental Protocols for Non-Destructive Analysis

Sample Handling and Presentation Protocols

Proper sample handling is essential for achieving accurate spectroscopic results while maintaining sample integrity. The specific protocols vary depending on sample type, but all share the common goal of presenting the sample to the instrument without alteration. For liquid samples, handling typically involves transfer via pipettes or syringes to minimize exposure to air and light, with storage in airtight containers to prevent evaporation and contamination [12]. Solid samples generally require no specific preparation beyond being placed in an appropriate holder, though they should be handled using gloves or tongs to prevent contamination [12].

The fundamental principle across all sample types is maintaining the material in its original state throughout the analytical process. Gases should be stored in sealed containers or cylinders to prevent leakage and handled using specialized equipment [12]. For particularly sensitive or labile samples, additional precautions such as cool storage or freezing may be employed to preserve sample integrity before analysis, though the spectroscopic measurement itself remains non-destructive [12]. These protocols ensure that samples remain viable for subsequent analysis or other applications following spectroscopic characterization.

Instrument Calibration and Method Validation

Instrument calibration is essential for ensuring that spectroscopic measurements are accurate and reliable while maintaining the non-destructive advantage. Calibration involves adjusting the instrument to ensure that it is measuring the correct wavelengths or frequencies, typically using stable calibration standards [12]. This process is particularly important for quantitative analysis, where precise measurement of spectral features correlates with material composition or properties.

Method validation establishes the performance characteristics of a spectroscopic method for its intended application, confirming that it delivers accurate results without compromising sample integrity. The validation process typically includes determination of accuracy, precision, specificity, and robustness using appropriate reference materials and procedures [12]. For non-destructive analysis, method validation also confirms that samples remain unchanged following analysis, often through comparison of pre- and post-analysis measurements or through additional testing of sample properties. This comprehensive approach ensures that the non-destructive nature of the analysis does not come at the expense of analytical reliability.

Quality Assurance in Non-Destructive Analysis

Quality assurance protocols for non-destructive spectroscopic analysis focus on verifying analytical performance while preserving sample integrity. Regular performance verification using stable reference materials confirms that instruments continue to operate within specified parameters, while quality control samples monitor ongoing analytical accuracy [12]. These procedures maintain analytical reliability without consuming samples or requiring destructive procedures.

Documentation of sample condition before and after analysis provides additional quality assurance for non-destructive methods. This may include visual inspection, photographic documentation, or baseline spectroscopic measurements confirmed to not affect sample properties. For valuable or irreplaceable samples, this documentation creates a permanent record of sample integrity throughout the analytical process, providing confidence in both the analytical results and the preservation of sample materials for future use.

Visualization of Non-Destructive Spectroscopy Workflow

Diagram 1: Non destructive analysis workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration and method validation | Essential for quantitative analysis; available for various matrix types |

| Spectral Libraries | Compound identification and verification | Commercial and custom libraries for specific applications |

| Chemometric Software | Data processing and multivariate analysis | Enables extraction of meaningful information from complex spectral data |

| Appropriate Solvents | Sample suspension or dilution when necessary | High-purity solvents that do not interfere with spectral features |

| Sample Holders/Cells | Sample presentation to instrument | Material-specific holders (e.g., quartz for UV, glass for VIS) |

| Portable Instrumentation | Field analysis and point-of-use testing | Maintains non-destructive advantages outside laboratory settings |

Spectroscopic techniques offer compelling advantages for modern analytical challenges, particularly through their unique combination of speed, cost-efficiency, and sample integrity preservation. These non-destructive methods enable rapid analysis with minimal sample preparation, significantly reducing analytical timelines while preserving valuable samples for future study. The economic benefits of spectroscopy extend beyond initial investment to encompass reduced consumable costs, lower waste disposal expenses, and decreased labor requirements. Most importantly, the preservation of sample integrity ensures that materials remain available for additional analysis, archival purposes, or other applications, maximizing the value of each sample. As spectroscopic technology continues to advance through integration with computational methods and artificial intelligence, these fundamental advantages will further solidify the position of non-destructive spectroscopic analysis as an essential methodology across scientific disciplines.

Spectroscopic techniques form the cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, providing indispensable tools for determining molecular structure, identifying chemical substances, and quantifying composition. These methods are fundamentally non-destructive, allowing researchers to analyze samples without altering their intrinsic properties or consuming them in the process. This preservation of sample integrity is particularly crucial in fields such as pharmaceutical development, forensic science, and cultural heritage analysis where materials may be rare, valuable, or required for subsequent testing. The non-destructive nature of these techniques enables continuous monitoring of chemical processes, long-term stability studies, and the analysis of irreplaceable specimens [13] [14].

The four techniques discussed in this guide—Infrared (IR), Near-Infrared (NIR), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), and Raman spectroscopy—each exploit different interactions between matter and electromagnetic radiation to extract unique chemical information. While they share the common advantage of being non-destructive, they differ significantly in their underlying physical principles, instrumentation requirements, and specific applications. This article provides a comprehensive technical overview of these core analytical methods, highlighting their complementary strengths in molecular analysis and their vital roles in scientific research and industrial applications [15].

Fundamental Principles and Comparison

Core Physical Principles

Each spectroscopic technique operates based on distinct quantum mechanical phenomena that determine its specific applications and limitations. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light that corresponds directly to the vibrational energies of molecular bonds. When infrared radiation interacts with a molecule, specific frequencies are absorbed, promoting bonds to higher vibrational states. The absorption pattern creates a unique "molecular fingerprint" that reveals information about functional groups and molecular structure [16] [15]. IR spectroscopy primarily targets the mid-infrared region (approximately 4000-400 cm⁻¹) where fundamental molecular vibrations occur, making it exceptionally sensitive to polar bonds such as O-H, N-H, and C=O [16].

Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy utilizes the higher-energy overtone and combination vibrations of fundamental molecular vibrations, primarily involving C-H, O-H, and N-H bonds. Located between the visible and mid-infrared regions (approximately 780-2500 nm), NIR absorption bands are typically 10-100 times weaker than corresponding fundamental mid-IR absorptions. This lower absorption coefficient enables NIR radiation to penetrate much further into samples, allowing analysis of bulk materials with minimal or no sample preparation. The complex, overlapping spectra produced require multivariate calibration techniques for meaningful interpretation [17].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei. When placed in a strong external magnetic field, nuclei with non-zero spin (such as ¹H, ¹³C, ¹⁹F) absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency range. The exact resonance frequency (chemical shift) depends on the local electronic environment, providing detailed information about molecular structure, dynamics, and interactions. NMR can detect nuclei through chemical bonds (J-coupling) and through space (nuclear Overhauser effect), making it unparalleled for complete structural elucidation [18] [14].

Raman spectroscopy is based on inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, usually from a laser in the visible, near-infrared, or near-ultraviolet range. When photons interact with molecules, a tiny fraction (approximately 1 in 10⁷ photons) undergoes Raman scattering, where energy is transferred to or from the molecule's vibrational modes. The energy difference between incident and scattered photons corresponds to vibrational energies, similar to IR spectroscopy. However, Raman intensity depends on changes in molecular polarizability during vibration, making it particularly sensitive to non-polar bonds and symmetric vibrations. This complementary selection rule means some vibrations observable by Raman may be weak or invisible in IR spectra, and vice versa [19] [20].

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Spectroscopic Techniques

| Characteristic | IR Spectroscopy | NIR Spectroscopy | NMR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Physical Interaction | Absorption of infrared radiation | Absorption of near-infrared radiation | Absorption of radiofrequency radiation | Inelastic scattering of visible/UV light |

| Energy Transition Probed | Vibrational (fundamental modes) | Vibrational (overtone/combination) | Nuclear spin flip | Vibrational (polarizability change) |

| Key Measured Parameter | Wavenumber (cm⁻¹) | Wavelength (nm) | Chemical shift (ppm) | Raman shift (cm⁻¹) |

| Typical Spectral Range | 400-4000 cm⁻¹ | 780-2500 nm | ¹H: 0-15 ppm; ¹³C: 0-240 ppm | 500-3500 cm⁻¹ |

| Information Obtained | Functional groups, molecular fingerprints | Quantitative composition, physical properties | Molecular structure, dynamics, connectivity | Functional groups, molecular symmetry, crystallinity |

| Sample Form | Solids, liquids, gases | Primarily solids and liquids | Primarily liquids (solutions) | Solids, liquids, gases |

| Destructive Nature | Non-destructive | Non-destructive | Non-destructive | Non-destructive (unless sample heating occurs) |

Table 2: Complementary Strengths and Limitations

| Technique | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| IR Spectroscopy | Excellent for functional group identification; High sensitivity to polar bonds; Quantitative capabilities; Well-established libraries | Limited penetration depth; Strong water absorption; Sample preparation often required |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Deep sample penetration; Minimal sample preparation; Rapid analysis; Suitable for online monitoring | Weak absorption bands; Complex spectra requiring chemometrics; Lower sensitivity; Indirect qualitative analysis |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Unparalleled structural elucidation; Quantitative without calibration; Probing molecular dynamics and interactions | Low sensitivity; Expensive instrumentation; Requires skilled operation; Typically needs soluble samples |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Minimal sample preparation; Weak water interference; Excellent for aqueous solutions; Spatial resolution down to μm | Fluorescence interference; Weak signals; Potential sample heating; Requires standards for quantification |

Instrumentation and Experimental Protocols

Instrument Components and Configuration

The instrumentation for each spectroscopic technique shares common elements—a radiation source, sample presentation system, wavelength selection device, detector, and data processor—but differs significantly in their specific implementation. IR spectrometers typically employ a heated filament, Nernst glower, or Globar as broadband infrared sources. Modern systems predominantly use Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) technology with an interferometer instead of a monochromator for wavelength selection, providing higher signal-to-noise ratio and faster acquisition. Common detectors include deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) for routine analysis and mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) for faster, more sensitive measurements. Sample interfaces vary from transmission cells for liquids and gases to attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessories that require minimal sample preparation for solids and liquids [16] [15].

NIR spectrometers utilize halogen lamps or light-emitting diodes (LEDs) as sources, with diffraction gratings or interferometers for wavelength selection. Detectors are typically silicon for the shorter NIR range (up to 1100 nm) and indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) or lead sulfide (PbS) for longer wavelengths. The sampling accessories are designed for rapid analysis, including fiber optic probes for remote measurements, reflectance accessories for solids, and transmission cells for liquids. The ability to use fiber optics enables integration of NIR analyzers directly into production processes for real-time monitoring [17] [21].

NMR spectrometers consist of three main components: a superconducting magnet, probe, and console. The magnet generates a stable, homogeneous magnetic field, with field strength measured in MHz (typically 400-1000 MHz for modern research instruments). The probe, situated within the magnet bore, contains radiofrequency coils for exciting nuclei and detecting signals, with different probes optimized for various nuclei (¹H, ¹³C, etc.) and sample types. The console controls pulse generation, signal detection, and data processing. Modern NMR systems require cryogenic cooling with liquid helium and nitrogen to maintain superconductivity [18].

Raman spectrometers are built around a monochromatic laser source (typically with wavelengths of 532, 785, or 1064 nm) to minimize fluorescence interference. The scattered light is collected by a lens and passed through a notch or edge filter to remove the intense Rayleigh scattered component (same frequency as laser). The remaining Raman signal is dispersed by a spectrograph (grating-based) and detected by a charge-coupled device (CCD). Fourier Transform (FT)-Raman systems with 1064 nm Nd:YAG lasers are advantageous for fluorescent samples, while dispersive systems with shorter wavelength lasers provide higher Raman scattering efficiency [19] [20].

Standard Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Methods:

Table 3: Sample Preparation Guidelines by Technique and Sample Type

| Technique | Solid Samples | Liquid Samples | Gas Samples | Specialized Preparations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR Spectroscopy | KBr pellets, thin films, ATR | Thin films between IR-transparent windows, ATR | Sealed gas cells | ATR for difficult samples (polymers, coatings) |

| NIR Spectroscopy | Minimal preparation; often analyzed directly in glass vials or reflectance cups | Direct analysis in vials or transmission cells; possible dilution for strongly absorbing samples | Rarely analyzed | Fiber optic probes for direct measurement through packaging |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Dissolved in deuterated solvents (CDCl₃, D₂O, DMSO-d₆) | Filtered to remove particulates; degassing for certain experiments | Limited applications; specialized probes | Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) for solid-state NMR |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Minimal preparation; often analyzed directly in glass vials or on slides | Direct analysis in capillaries, cuvettes, or on slides | Sealed gas cells | Surface-Enhanced Raman (SERS) using nanostructured metal substrates |

Data Collection Parameters:

- IR Spectroscopy: Typically 4-32 cm⁻¹ resolution; 16-64 scans for adequate signal-to-noise ratio; background spectrum collection for atmosphere compensation [16]

- NIR Spectroscopy: Lower resolution (8-16 cm⁻¹) due to broad bands; multiple scans (32-128) for representative sampling; careful calibration with reference methods required [17] [21]

- NMR Spectroscopy: Parameter optimization including pulse width, relaxation delay, acquisition time, and number of transients; temperature control for stability; locking and shimming for field homogeneity [18]

- Raman Spectroscopy: Laser power optimization to avoid sample damage; appropriate integration time (1-10 seconds) and accumulations; calibration with silicon standard (520.7 cm⁻¹) [19] [20]

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Context | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR-transparent matrix for solid samples | IR spectroscopy of solids | Must be finely ground, dried, and pressed under vacuum; hygroscopic |

| Deuterated Solvents (CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆, D₂O) | NMR solvent with minimal interference | NMR spectroscopy | Provides lock signal; maintains field frequency; degree of deuteration affects sensitivity |

| Internal Standards (TMS, DSS) | Chemical shift reference | NMR spectroscopy | Added in small quantities; chemically inert; provides defined reference peak (0 ppm) |

| ATR Crystals (diamond, ZnSe, Ge) | Internal reflection element | ATR-IR spectroscopy | Different crystal materials offer varying hardness, pH resistance, and penetration depth |

| NIR Calibration Sets | Reference materials for multivariate models | NIR spectroscopy | Must represent expected sample variability; requires primary method validation |

| SERS Substrates (nanostructured Au, Ag) | Signal enhancement surface | Surface-Enhanced Raman | Provides plasmonic enhancement (10⁶-10⁸×); stability and reproducibility vary |

| Raman Standards (silicon, cyclohexane) | Instrument calibration | Raman spectroscopy | Verifies wavelength accuracy and intensity response; silicon (520.7 cm⁻¹) common |

Applications in Research and Industry

The non-destructive nature of these spectroscopic techniques enables their application across diverse fields where sample preservation is essential. In the pharmaceutical industry, IR and NIR spectroscopy are extensively used for raw material identification, process monitoring, and quality control of final products. NIR's ability to analyze samples through packaging makes it invaluable for stability testing without compromising product integrity. NMR spectroscopy provides critical structural verification of active pharmaceutical ingredients and excipients, while Raman spectroscopy offers mapping capabilities for assessing drug distribution and polymorph form in solid dosage forms [16] [17] [21].

In biological research, NMR serves as a powerful tool for determining three-dimensional structures of proteins and nucleic acids in near-physiological conditions, studying molecular dynamics, and characterizing metabolic pathways through metabolomics. IR and Raman spectroscopy provide label-free methods for analyzing cellular components, monitoring biochemical changes in tissues, and differentiating disease states based on spectral fingerprints. The minimal interference from water in Raman spectroscopy makes it particularly suited for studying aqueous biological systems [19] [14].

Materials science applications include polymer characterization (chain orientation, crystallinity, degradation), analysis of semiconductors, and monitoring of catalytic reactions. IR spectroscopy identifies functional groups in novel materials, while Raman spectroscopy characterizes carbon nanomaterials, measures strain in nanostructures, and investigates phonon modes in crystals. NIR spectroscopy assists in optimization of polymer manufacturing processes through real-time composition monitoring [16] [19] [21].

Additional specialized applications include forensic science (analysis of trace evidence, paints, fibers, drugs), food and agriculture (quality assessment, authenticity verification, composition analysis), environmental monitoring (pollutant detection, water quality analysis), and art conservation (pigment identification, degradation assessment) [16] [17].

Technical Diagrams

Fundamental Processes of Spectroscopy Techniques

Molecular Information Levels by Technique

IR, NIR, NMR, and Raman spectroscopy represent a powerful suite of non-destructive analytical techniques that provide complementary information about molecular structure and composition. Each method offers unique capabilities—IR for functional group identification, NIR for rapid quantitative analysis, NMR for detailed structural elucidation, and Raman for molecular symmetry and crystal structure characterization. Their non-destructive nature enables repeated measurements of valuable samples, real-time process monitoring, and analysis of materials that cannot be altered or consumed. The selection of an appropriate technique depends on the specific analytical requirements, sample characteristics, and information needed. When used individually or in combination, these spectroscopic methods form an indispensable toolkit for scientific research and industrial analysis across diverse fields including pharmaceuticals, materials science, biotechnology, and forensic investigation.

Molecular fingerprints, vector representations of chemical structures, and spectroscopic data are two complementary languages describing molecular identity. This guide explores their intersection, framed within the non-destructive nature of spectroscopic analysis, which preserves sample integrity while revealing structural information [22] [23]. For researchers in drug development, understanding this relationship is crucial for accelerating virtual screening, compound identification, and quality control.

Spectroscopic techniques act as a "molecular microscope", with each method providing a different lens for viewing molecular features [24]. The core of this analysis involves two interconnected problems: the forward problem (predicting spectra from a molecular structure) and the inverse problem (deducing molecular structure from experimental spectra), both central to molecular elucidation in life sciences and chemical industries [24].

Fundamentals of Molecular Fingerprints

Molecular fingerprints are abstract representations that convert structural features into a fixed-length vector format, enabling efficient computational handling and comparison of chemical structures [25]. The evolution of fingerprint types reflects a continuous effort to balance detail with computational efficiency.

Types and Evolution of Molecular Fingerprints

Rule-Based Fingerprints: Early systems relied on predefined structural rules. Substructure fingerprints (e.g., MACCS, PubChem) encode the presence or absence of specific molecular fragments or functional groups [26] [27]. Circular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, Morgan) capture circular substructures around each atom, representing the local chemical environment [25] [26]. Atom-pair fingerprints describe molecular shape by recording the topological distance between all atom pairs, providing excellent perception of global features like size and shape [28] [26].

Data-Driven Fingerprints: Modern approaches leverage machine learning to generate fingerprints. Deep learning fingerprints are created using encoder-decoder models like Graph Autoencoders (GAE), Variational Autoencoders (VAE), and Transformers, which learn compressed representations from molecular structures [26].

Hybrid and Next-Generation Fingerprints: The MAP4 fingerprint combines substructure and atom-pair concepts by describing atom pairs with the circular substructures around each atom, making it suitable for both small molecules and large biomolecules [28]. Visual fingerprinting systems like SubGrapher bypass traditional representations by detecting functional groups and carbon backbones directly from chemical structure images, constructing a fingerprint based on the spatial arrangement of these substructures [27].

Performance Comparison of Fingerprint Types

Table 1: Comparative analysis of molecular fingerprint types and their characteristics

| Fingerprint Type | Structural Basis | Best Application Context | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP4/Morgan [28] [26] | Circular substructures | Small molecule virtual screening, QSAR | Excellent for small molecules, predictive of biological activity |

| Atom-Pair (AP) [28] [26] | Topological atom paths | Scaffold hopping, large molecules | Perceives molecular shape, suitable for peptides & biomolecules |

| MAP4 [28] | Hybrid atom-pair & circular | Universal: drugs, biomolecules, metabolome | Superior performance across small & large molecules |

| Data-Driven (DL) [26] | Learned latent space | Target prediction, property optimization | Can incorporate complex structural patterns beyond explicit rules |

| SubGrapher (Visual) [27] | Image-based substructures | Patent analysis, document mining | Works directly from images, robust to drawing conventions |

Spectroscopic Techniques as Non-Destructive Molecular Fingerprints

Spectroscopic techniques provide experimental fingerprints that complement computationally derived representations. Their non-destructive nature is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical applications where sample preservation is crucial [22] [23].

Spectroscopic Modalities and Their Information Content

Raman Spectroscopy: This technique provides vibrational fingerprints sensitive to crystallographic structure and chemical composition. It requires no sample preparation and enables analysis through transparent containers like glass vials, making it ideal for forensic analysis and quality control [22]. Its confocal capabilities allow mapping trace quantities of controlled substances on surfaces, with the resulting spectral features enabling identification of each component and their distribution [22].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): NMR spectra provide detailed information about the carbon-hydrogen framework of compounds. Advanced 2D and 3D-NMR techniques enable characterization of complex molecules including natural products and proteins [24]. Machine learning models like IMPRESSION can now predict NMR parameters with near-quantum chemical accuracy while reducing computation time from days to seconds [24].

Mass Spectrometry (MS): MS determines molecular mass and formula while identifying fragment patterns when molecules break apart. This provides structural insights through characteristic fragmentation patterns [24].

Infrared (IR) and UV-Vis Spectroscopy: IR identifies functional groups within compounds, while UV-Vis provides information about compounds with conjugated double bonds [24].

Quantitative Spectral Fingerprinting Applications

Table 2: Non-destructive quantitative analysis of pharmaceutical formulations using spectroscopy

| Application | Technique | Sample Type | Analytical Methodology | Performance Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Identification [22] | Confocal Raman Spectroscopy | Controlled substances (e.g., cocaine forms) | Direct spectral measurement through glass vials | Clear differentiation between free base and HCl forms |

| Pharmaceutical Ointment Analysis [23] | Transmission Raman Spectroscopy | Crystal dispersion-type ointment (3% acyclovir) | PLS regression with spectral preprocessing | Average recovery: 85% LC (100.7%), 100% LC (99.3%), 115% LC (99.8%) |

| Trace Mixture Analysis [22] | Raman Mapping | Surface traces of drug mixtures | Confocal point mapping + 2D image construction | Localization of cocaine, caffeine, amphetamine in 25µm×35µm area |

Computational Integration: From Spectra to Structures

The integration of artificial intelligence with spectroscopy has created new paradigms for analyzing spectral data, transforming how we solve both forward and inverse problems in molecular analysis [24].

AI Approaches in Spectral Analysis

The field of Spectroscopy Machine Learning (SpectraML) encompasses machine learning applications across major spectroscopic techniques including MS, NMR, IR, Raman, and UV-Vis [24]. These approaches address both the forward problem (predicting spectra from molecular structures) and the inverse problem (deducing molecular structures from spectra) [24].

Forward modeling provides significant advantages by reducing the need for costly experimental measurements and enhancing understanding of structure-spectrum relationships [24]. For the inverse problem, AI transforms molecular elucidation by automating spectral interpretation and overcoming challenges like overlapping signals, sample impurities, and isomerization [24].

Workflow for Spectra-Based Molecular Identification

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational-experimental workflow for molecular identification using spectroscopic fingerprints and AI:

Molecular Identification Workflow Using Spectroscopic Fingerprints and AI

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Raman Spectral Analysis of Controlled Substances

Objective: To identify and differentiate between cocaine forms (free base vs. HCl) and their mixtures with cutting agents using non-destructive Raman spectroscopy [22].

Instrumentation: LabRAM system with 785nm diode laser and 633nm HeNe laser, long working distance objective for analysis through glass vials [22].

Methodology:

- Sample Presentation: Place particles in glass vials; analyze directly through glass window to prevent degradation/contamination

- Spectral Acquisition: Record spectra using 785nm laser to minimize fluorescence interference from contaminants

- Background Subtraction: Use software features to subtract glass background contribution (~1400cm⁻¹)

- Spectral Interpretation: Differentiate forms by examining the 845-900cm⁻¹ triplet pattern:

- Cocaine HCl: Most intense band at 870cm⁻¹

- Free base: Most intense band at 847cm⁻¹

- Mixture Analysis: For drug-cutting agent mixtures, identify cocaine presence by its characteristic intensity pattern despite signal dilution

Key Advantages: Non-contact, no sample preparation, preserves evidence for further investigation, high spatial resolution enables small sample volume analysis [22].

Non-Destructive Quantitative Analysis of Pharmaceutical Ointments

Objective: Develop quantitative model for drug assay in crystal dispersion-type ointment using transmission Raman spectroscopy [23].

Materials: Acyclovir (3% w/w model drug) in white petrolatum base, calibration samples with 85%, 100%, 115% label claims [23].

Methodology:

- Spectral Collection: Acquire transmission Raman spectra across multiple samples

- Spectral Preprocessing:

- Apply multiplicative scatter correction (MSC)

- Process with standard normal variate (SNV)

- Calculate first or second derivatives using Savitzky-Golay method

- Model Development: Optimize partial least squares (PLS) regression model using preprocessed spectral data

- Validation: Test model performance on commercial product with different material properties and manufacturing methods

Performance Metrics: Average recovery values of 100.7% (85% LC), 99.3% (100% LC), 99.8% (115% LC); commercial product mean recovery: 104.2% [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential tools and software for spectral fingerprinting research

| Tool/Software | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [28] [25] | Cheminformatics Library | Fingerprint generation & manipulation | Calculating Morgan fingerprints, similarity metrics, molecular operations |

| MAP4 Fingerprint [28] | Computational Fingerprint | Unified molecular representation | Similarity search across drugs, biomolecules, metabolome |

| HORIBA LabRAM [22] | Raman Instrumentation | Confocal Raman spectral acquisition | Non-destructive drug analysis through transparent containers |

| scikit-learn [25] [26] | ML Library | Machine learning model implementation | Random forests, naïve Bayes for spectral data modeling |

| SubGrapher [27] | Visual Recognition | Image-based fingerprint extraction | Direct functional group recognition from chemical structure images |

| PLSR Models [23] | Chemometric Method | Multivariate calibration | Quantitative spectral analysis for pharmaceutical formulations |

Molecular fingerprints and spectroscopic techniques form a powerful synergy for non-destructive molecular analysis. Spectra provide experimental fingerprints that validate and complement computational fingerprints, creating a robust framework for molecular identification and structural elucidation. The integration of machine learning with spectroscopy accelerates this process, enabling solutions to both forward and inverse problems with unprecedented speed and accuracy.

For drug development professionals, these methodologies offer preservative analysis of valuable compounds throughout the development pipeline—from initial discovery through quality control. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, the marriage of spectroscopic fingerprints and molecular representations will continue to transform how we understand and manipulate molecular identity in pharmaceutical research.

Key Spectroscopic Techniques and Their Cutting-Edge Applications in Research

Vibrational spectroscopy, encompassing Infrared (IR) and Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, provides a suite of non-destructive analytical techniques essential for modern quality control and metabolite research. These methods are grounded in the study of molecular vibrations, delivering rapid, label-free analysis without the need for extensive sample preparation. The non-destructive nature of these techniques preserves sample integrity, allowing for repeated measurements and real-time monitoring, which is a cornerstone of the broader thesis that spectroscopic analysis represents a paradigm shift in analytical science [29] [30]. NIR spectroscopy, in particular, probes the overtones and combinations of fundamental vibrations of chemical bonds such as C-H, O-H, and N-H, making it exceptionally sensitive to the organic molecules found in pharmaceuticals, agricultural products, and biological systems [31].

The fundamental advantage of these techniques lies in their ability to provide both physical and chemical information simultaneously. This dual capability is critical for applications ranging from pharmaceutical manufacturing to agricultural phenotyping, where understanding both composition and distribution is key. Fourier Transform NIR (FT-NIR) systems, for instance, offer higher resolution, better wavelength accuracy, and greater stability compared to dispersive systems, making them particularly suitable for rigorous industrial environments [32]. This technical guide delves into the specific applications, detailed methodologies, and performance data that demonstrate the transformative role of vibrational spectroscopy in industrial and research settings.

Core Principles and Technological Advantages

The operational principles of IR and NIR spectroscopy are based on the interaction of infrared light with matter. When light in these wavelengths strikes a sample, it can be transmitted, reflected, absorbed, or scattered. The specific wavelengths absorbed correspond to the vibrational energies of the chemical bonds within the molecules, creating a unique spectral fingerprint for each sample [32]. NIR spectroscopy (700–2500 nm) is especially powerful because it accesses these molecular vibrations via overtones and combination bands, which, while weaker than fundamental IR absorptions, are perfectly suited for analyzing intact, often untreated samples.

The technological advantages of these methods are substantial:

- Speed and Efficiency: Analyses can be completed in seconds, enabling high-throughput screening essential for breeding programs and industrial process control [31] [33].

- Versatility: A single spectrum can be used to predict multiple quality parameters concurrently, such as the content of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in tablets or multiple metabolites in plant leaves [34] [31].

- In-line and On-line Capability: Fiber optic probes allow for direct integration into production processes, such as conveyor belts, reactors, or hoppers, facilitating real-time release testing and continuous quality assurance [34] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow of a spectroscopic analysis, from measurement to result, highlighting the integrated nature of hardware, data processing, and model application.

Pharmaceutical Quality Control via NIR Spectroscopy

In-line Monitoring of Drug Products

In the pharmaceutical industry, NIR spectroscopy has been successfully implemented for the non-destructive quality control of final drug products, such as tablets. A key application involves using a specially designed multipoint measurement probe installed on a conveyor belt system to control both the distribution and content of the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) across a production lot [34]. This approach overcomes limitations related to acquisition speed and sampling area, providing comprehensive physical and chemical knowledge of the product. The spatial and spectral information gathered serves as an innovative paradigm for real-time release strategy, a core objective of Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiatives [34].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tablet Analysis on a Conveyor Belt

The following workflow details the methodology for in-line tablet monitoring:

- Instrumentation Setup: A Fourier Transform NIR (FT-NIR) spectrometer is coupled with a custom-designed fiber optic probe featuring multiple collection fibers. This probe is mounted above a conveyor belt transporting the tablets.

- Spectral Acquisition: The NIR probe scans each tablet as it passes on the conveyor belt. The system operates in reflectance mode, where the diffusely reflected light from the solid tablet is collected and sent to the detector [34] [32].

- Data Pre-processing: Acquired raw spectra are subjected to pre-processing techniques such as Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) to reduce the effects of light scattering and physical variations between tablets.

- Quantitative Modeling: A Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression model is used. This model, developed during the calibration phase, correlates the spectral variations with known variations in the API concentration (as determined by a reference method like HPLC).

- Prediction and Control: The calibrated PLS model is applied to the real-time spectral data from the production line to predict the API content in each tablet. The spatial data from the multipoint probe allows for monitoring the uniformity of API distribution across the batch.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics in Pharmaceutical NIR Applications

| Application Focus | Key Measured Variable | Sampling Mode | Primary Chemometric Method | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tablet API Content [34] | Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) Concentration | Reflectance | Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Real-time content uniformity analysis |

| Tablet API Distribution [34] | Spatial API Distribution | Multipoint Reflectance | Multipoint PLS Modeling | Ensures blend homogeneity |

| Process Analysis [32] | Component Concentration in Reactors | Fiber Optic Transflectance | PLS | In-line monitoring for process control |

Non-Destructive Metabolite Estimation in Agricultural Products

Metabolite Profiling in Fresh Tea Leaves

NIR spectroscopy combined with machine learning has demonstrated significant potential for the non-destructive estimation of quality-related metabolites in fresh tea leaves (Camellia sinensis L.). Research has effectively estimated the contents of free amino acids (e.g., theanine), catechins, and caffeine using visible to short-wave infrared (400–2500 nm) hyperspectral reflectance data [31]. This approach addresses a critical need in tea cultivation and breeding, where traditional methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) are destructive, time-consuming, and expensive [31].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tea Leaf Metabolite Estimation

- Sample Preparation: Approximately 200 fresh tea leaves with varying status (e.g., different nitrogen conditions, leaf stages, shading conditions) are collected. Leaves are presented for scanning without destructive pre-treatment.

- Hyperspectral Data Acquisition: Reflectance spectra are acquired from each leaf at 1-nm intervals across the 400–2500 nm wavelength range using a hyperspectral sensor.

- Reference Analysis: The same scanned leaves are destructively analyzed post-scanning using HPLC to determine the precise concentrations of 15 metabolites, including catechins, caffeine, and free amino acids, creating the reference dataset for model training [31].

- Data Pre-processing and Modeling: Six spectral patterns are tested (Original Reflectance, First Derivative, etc.) with five machine learning algorithms (Random Forest, Cubist, etc.). The combination of De-trending (DT) pre-processing and the Cubist algorithm was robustly selected as the best-performing model for most metabolites over 100 repetitions [31].

- Model Validation: Model performance is evaluated using the Ratio of Performance to Deviation (RPD). Values above 1.4 are considered acceptable, and above 2.0 are considered accurate for analytical applications [31].

Table 2: Performance of NIR Spectroscopy in Estimating Tea Metabolites (Best Model: DT-Cubist) [31]

| Metabolite | Mean RPD Value | Interpretation | Concentration Range (μg cm⁻²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Catechins | 2.7 | Accurate Estimation | 206.2 – 2528.7 |

| (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) | 2.4 | Accurate Estimation | 91.0 – 619.8 |

| Total Free Amino Acids | 2.3 | Accurate Estimation | 12.3 – 746.0 |

| Caffeine | 1.8 | Acceptable to Accurate | 1.8 – 393.1 |

| Theanine | 1.5 | Acceptable Estimation | 0.2 – 264.5 |

| Aspartate | 2.5 | Accurate Estimation | 1.6 – 59.3 |

Protein Estimation in Rice Breeding

A similar NIRS approach is used in rice breeding programs for the rapid, non-destructive estimation of protein content in brown rice flour. This application is a case study in high-throughput phenotyping, essential for matching the efficiency of modern genotyping. Proteins contain chemical bonds (C-H, N-H) easily detected by NIRS, making this a suitable target [33]. The method involves scanning ground flour in a reflectance cup, followed by calibration using PLS regression against the reference protein data obtained via the Kjeldahl method or similar [33]. This allows breeders to screen early-generation material efficiently for a trait that influences cooking and eating quality.

Essential Reagents and Research Tools

The successful implementation of vibrational spectroscopy methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details the core components of the "Scientist's Toolkit" for these applications.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Vibrational Spectroscopy

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| FT-NIR Spectrometer [32] | Core instrument for acquiring high-resolution, wavelength-accurate spectra. | Superior stability and repeatability vs. dispersive systems; no software standardization needed between instruments. |

| Fiber Optic Reflection Probe [34] [32] | Enables in-line measurement on conveyor belts, in reactors, or hoppers. | Often engineered with automatic cleaning (e.g., high-pressure air) for process environments. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging Sensor [31] | Captures spatial and spectral information for heterogeneous solid samples like leaves. | Covers VIS-NIR-SWIR range (400-2500 nm) for broad metabolite estimation. |

| Chemometric Software (PLS, Cubist) [31] [32] | Develops calibration models linking spectral data to reference analytical results. | Machine learning algorithms (e.g., Cubist) can improve model accuracy for complex traits. |

| Calibration Standards [32] | A set of samples with known chemical values for building the quantitative model. | Must include all chemical, physical, and sampling variation the model will encounter; often requires 10x the number of components as a minimum. |

Integrated Workflow from Sample to Result

The application of vibrational spectroscopy, whether in a laboratory or an industrial setting, follows a logical and integrated sequence. The diagram below maps the critical decision points and steps in the method development and deployment process, highlighting the non-destructive feedback loop that enables real-time control.

Vibrational spectroscopy, particularly NIR and IR, has firmly established itself as a powerful, non-destructive cornerstone for quality control and metabolite estimation. Its ability to provide rapid, non-invasive, and multi-parameter analyses aligns perfectly with the demands of modern industrial processes and advanced scientific research. The detailed protocols and performance data presented confirm that these techniques are not merely supplementary but are often the optimal choice for ensuring product quality in pharmaceuticals and accelerating phenotyping in agriculture. As spectroscopic instrumentation and machine learning algorithms continue to advance, the scope and accuracy of these non-destructive analyses are poised to expand further, solidifying their role as indispensable tools in the scientist's arsenal.

NMR Spectroscopy for Detailed Structural Elucidation of Complex Molecules

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stands as a cornerstone analytical technique in modern research for determining the complete structural composition of organic compounds and biomolecules. As a non-destructive method, it enables the detailed analysis of precious samples without consumption or alteration, preserving material for subsequent studies [35]. This whitepaper examines the fundamental principles, advanced methodologies, and practical applications of NMR spectroscopy, with particular emphasis on its growing role in pharmaceutical research and drug discovery where molecular complexity demands atomic-level precision.

The technique exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei, which absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation at characteristic frequencies when placed in a strong magnetic field [36]. By measuring these frequencies, NMR provides detailed information about the electronic environment surrounding nuclei, revealing the number and types of atoms in a molecule, their connectivity, and their spatial arrangement [37]. This information is obtained from various NMR parameters including chemical shifts, coupling constants, and signal intensities, allowing scientists to construct a comprehensive picture of molecular structure and dynamics [37].

Fundamental Principles of NMR Spectroscopy

Theoretical Foundation

NMR spectroscopy originates from the intrinsic property of certain atomic nuclei possessing spin, characterized by the spin quantum number (I) [36]. Elements with either odd mass or odd atomic numbers exhibit nuclear "spin" [36]. For NMR-active nuclei such as hydrogen-1 (¹H) and carbon-13 (¹³C), the spin quantum number I = ½, resulting in two possible spin states (+½ and -½) [38]. In the absence of an external magnetic field, these states are energetically degenerate. However, when placed in a strong external magnetic field (B₀), this degeneracy is lifted, creating distinct energy levels through Zeeman splitting [36] [38].

The energy difference between these states corresponds to electromagnetic radiation in the radiofrequency region (typically 4-900 MHz) [36]. The precise resonance frequency of a nucleus depends on the strength of the applied magnetic field and its magnetogyric ratio (γ), a fundamental constant unique to each nuclide [36]. Crucially, the local electronic environment surrounding each nucleus slightly shields it from the applied field, causing subtle shifts in resonance frequency that form the basis of NMR's analytical power.

Key NMR Parameters for Structural Elucidation

NMR spectra contain rich information through several measurable parameters, detailed in the table below.

Table 1: Key Information Contained in NMR Spectra