Nuclear Binding Energy and Mass Defect: Calculations, Applications, and Biomedical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nuclear binding energy and its critical role in mass defect calculations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Nuclear Binding Energy and Mass Defect: Calculations, Applications, and Biomedical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of nuclear binding energy and its critical role in mass defect calculations, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental physics underpinning nuclear stability, details practical methodologies for calculating mass defect and binding energy, and addresses common challenges in computational modeling. The content further examines the validation of nuclear models and discusses the direct implications of these nuclear phenomena for biomedical research, including the development of radiopharmaceuticals and advanced cancer therapies.

The Foundation of Nuclear Stability: Understanding Mass Defect and Binding Energy

In nuclear physics, the mass defect of an atomic nucleus is the fundamental quantity that reveals the energy which binds nucleons together. It is defined as the difference between the sum of the masses of an atom's individual protons, neutrons, and electrons and the atom's actual experimentally measured mass [1] [2]. This apparent "missing mass" is not an error in measurement but rather physical mass that has been converted into binding energy during the nucleus formation, in accordance with Einstein's mass-energy equivalence principle, (E = mc^2) [3] [4]. The relationship is inverse: a larger mass defect corresponds to a more stable nucleus, as more energy was released during its formation and thus more must be supplied to break it apart [2].

This phenomenon is directly linked to the nuclear binding energy, which is the energy required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons completely [5]. The mass defect and nuclear binding energy are therefore two different manifestations of the same physical reality; the mass defect ((\Delta m)) is the mass equivalent of the binding energy ((Eb)), related by Einstein's equation: (Eb = (\Delta m)c^2) [6]. Understanding mass defect is crucial for fields ranging from astrophysics, where it explains stellar energy generation via fusion [3], to nuclear energy, where it quantifies the energy potential in fission and fusion processes [3].

Theoretical Foundation

The Mass Defect Concept

The theoretical prediction for an atom's mass is a straightforward sum of its components. A neutral atom with atomic number (Z) (number of protons) and mass number (A) (total nucleons) contains (Z) protons, (Z) electrons, and (N = A - Z) neutrons. The predicted mass (m_{\text{predicted}}) is therefore:

[m{\text{predicted}} = Z \cdot mp + Z \cdot me + (A - Z) \cdot mn]

where (mp), (me), and (mn) are the rest masses of a proton, electron, and neutron, respectively [4]. However, meticulous experimental measurements have established that the actual nuclear mass (m{\text{actual}}) is always less than this calculated sum [2]. The mass defect (\Delta m) is this difference:

[\Delta m = m{\text{predicted}} - m{\text{actual}}]

The reason for this mass defect lies in the conversion of mass into energy. When protons and neutrons combine to form a nucleus, the strong nuclear force acts to bind them together. During this process, a portion of their mass is converted into energy and released, primarily as gamma radiation [5]. This released energy is the binding energy. Consequently, the mass of the bound system is less than the mass of its unbound components. The equivalence between the mass defect and the binding energy (E_b) is given by Einstein's renowned equation:

[E_b = (\Delta m) c^2]

where (c) is the speed of light in a vacuum [6]. This relationship is foundational to nuclear physics.

Nuclear Binding Energy and Stability

While the total binding energy indicates the overall stability of a nucleus, a more useful measure for comparing stability across different nuclides is the binding energy per nucleon (BEN), defined as [6]:

[\text{BEN} = \frac{E_b}{A}]

This quantity represents the average energy required to remove a single nucleon from the nucleus. A higher binding energy per nucleon signifies a more stable nucleus [2].

Table: Mass and Energy Equivalents of Subatomic Particles

| Particle | Mass (u) | Mass (kg) | Energy Equivalent (MeV/c²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton | 1.007276 [7] | 1.673 × 10⁻²⁷ [2] | 938.28 [6] |

| Neutron | 1.008665 [7] | 1.675 × 10⁻²⁷ [2] | 939.57 [6] |

| Electron | 0.00055 [4] | ~9.11 × 10⁻³¹ | ~0.511 |

A plot of the binding energy per nucleon against the mass number (A) reveals key insights into nuclear stability and energy release [7] [2]. The curve rises steeply for light nuclei, peaks at elements in the vicinity of iron-56 (which has the highest BEN and is thus the most stable nucleus), and then gradually decreases for heavier nuclei [7] [3] [2]. This profile has two critical implications:

- Fusion: Combining two light nuclei into a heavier one with a higher BEN (up to iron) is an exothermic process.

- Fission: Splitting a very heavy nucleus into mid-weight fragments with higher BEN is also an exothermic process [3] [2].

Quantitative Analysis and Methodologies

Calculating Mass Defect and Binding Energy: A Step-by-Step Protocol

The following methodology allows for the precise calculation of the mass defect and the corresponding nuclear binding energy for any given isotope.

Table: Fundamental Physical Constants for Calculations

| Constant | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of light | c | 2.9979 × 10⁸ m/s [1] |

| Atomic mass unit to kg | u | 1.6606 × 10⁻²⁷ kg [1] |

| MeV to Joules | - | 1.602 × 10⁻¹³ J [1] |

Protocol: Calculation for Potassium-40 (¹⁹K⁴⁰) [2]

Identify Nuclear Composition:

- Proton number, (Z = 19)

- Neutron number, (N = A - Z = 40 - 19 = 21)

Calculate the Predicted Mass:

- Obtain the individual particle masses in unified atomic mass units (u).

- Mass of one proton, (mp = 1.007276 \, \text{u})

- Mass of one neutron, (mn = 1.008665 \, \text{u})

- Predicted mass, (m{\text{predicted}} = (Z \cdot mp) + (N \cdot mn))

- (m{\text{predicted}} = (19 \times 1.007276 \, \text{u}) + (21 \times 1.008665 \, \text{u}) = 40.34692 \, \text{u})

- Obtain the individual particle masses in unified atomic mass units (u).

Determine the Mass Defect ((\Delta m)):

- Obtain the actual nuclear mass from experimental data (e.g., AME2020 database). For K-40, (m_{\text{actual}} = 39.953548 \, \text{u}).

- Mass defect, (\Delta m = m{\text{predicted}} - m{\text{actual}})

- (\Delta m = 40.34692 \, \text{u} - 39.953548 \, \text{u} = 0.393372 \, \text{u})

Convert Mass Defect to Energy:

- Method A: Using energy equivalents.

- The mass-energy equivalence is (1 \, \text{u} = 931.494 \, \text{MeV}/c^2) [7].

- Binding Energy, (Eb = \Delta m \times 931.494 \, \text{MeV}/c^2)

- (Eb = 0.393372 \, \text{u} \times 931.494 \, \text{MeV}/\text{u} = 366.30 \, \text{MeV})

- Method B: Using SI units.

- Convert (\Delta m) to kilograms: (\Delta m \, (\text{kg}) = \Delta m \, (\text{u}) \times (1.6606 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg/u}))

- (\Delta m = 0.393372 \, \text{u} \times (1.6606 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg/u}) = 6.532 \times 10^{-28} \, \text{kg})

- Apply (E = mc^2):

- (Eb = (6.532 \times 10^{-28} \, \text{kg}) \times (2.9979 \times 10^8 \, \text{m/s})^2 = 5.871 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{J})

- Convert Joules to MeV: (Eb \, (\text{MeV}) = Eb \, (\text{J}) \div (1.602 \times 10^{-13} \, \text{J/MeV}))

- (Eb = 5.871 \times 10^{-11} \, \text{J} \div (1.602 \times 10^{-13} \, \text{J/MeV}) = 366.48 \, \text{MeV})

- Convert (\Delta m) to kilograms: (\Delta m \, (\text{kg}) = \Delta m \, (\text{u}) \times (1.6606 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg/u}))

- Method A: Using energy equivalents.

Compute Binding Energy per Nucleon:

- (\text{BEN} = E_b / A = 366.3 \, \text{MeV} / 40 = 9.16 \, \text{MeV})

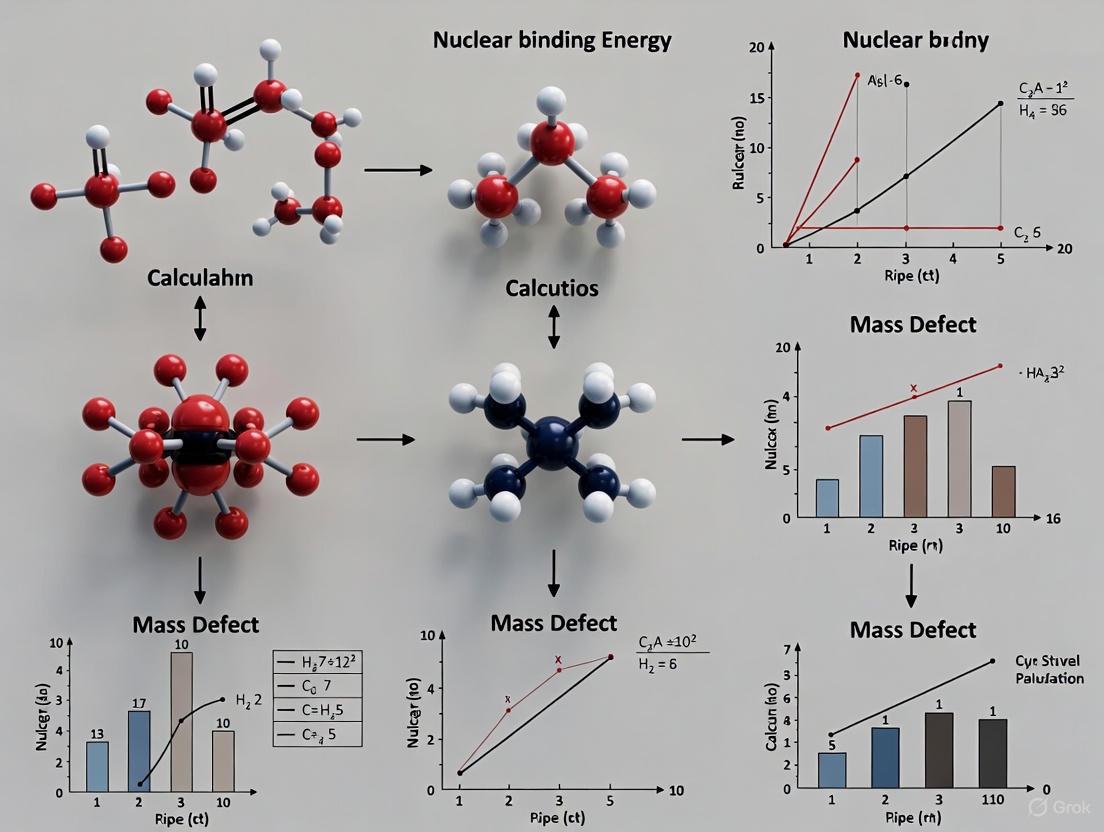

Workflow for Mass Defect Determination

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and calculations involved in determining the mass defect and binding energy.

Advanced Modeling and Current Research

The Liquid Drop Model and Semi-Empirical Mass Formula

The Liquid Drop Model (LDM) provides a foundational semi-empirical formula to approximate nuclear binding energy based on the analogy of a nucleus to a charged liquid drop [8] [5]. The model accounts for various energy contributions and can be written as:

[B(A,Z,N) \approx aV A - aS A^{2/3} - aC \frac{Z(Z-1)}{A^{1/3}} - aA \frac{(A-2Z)^2}{A} + \delta(N,Z)]

The function and typical values for the coefficients are as follows [5]:

- Volume Energy ((a_V \approx 15.8 \, \text{MeV})): This term dominates and reflects the constant binding energy per nucleon due to the strong nuclear force, proportional to the nuclear volume and thus the mass number (A).

- Surface Energy ((a_S \approx 18.6 \, \text{MeV})): A correction term for nucleons on the surface, which have fewer neighbors binding them. It is proportional to the surface area, (A^{2/3}).

- Coulomb Energy ((a_C \approx 0.717 \, \text{MeV})): The electrostatic repulsion between protons, which reduces the binding energy. It is proportional to (\frac{Z(Z-1)}{A^{1/3}}).

- Asymmetry Energy ((a_A \approx 23.3 \, \text{MeV})): This term accounts for the Pauli exclusion principle's effect, which favors symmetric nuclei where the number of protons and neutrons is equal ((N=Z)). It becomes more significant as (|N-Z|) increases.

- Pairing Energy ((\delta)): This term depends on the parity of protons and neutrons, providing a small correction that increases stability when both (Z) and (N) are even [8] [5]: [ \delta = \begin{cases} +11/\sqrt{A} \, \text{MeV} & \text{even } Z, \text{ even } N \ 0 & \text{odd } A \ -11/\sqrt{A} \, \text{MeV} & \text{odd } Z, \text{ odd } N \end{cases} ]

While the LDM captures general trends, it has limitations, particularly for light nuclei and nuclei with "magic numbers" of nucleons, which are exceptionally stable and not predicted by the model [8] [5].

Contemporary Data-Driven Approaches

Current research is addressing the limitations of traditional models through advanced computational and data-driven techniques.

- Symbolic and Continued Fraction Regression: A novel approach uses Continued Fraction Regression (cf-r) to find analytical functions that closely approximate nuclear binding energies directly from experimental data, such as the Atomic Mass Evaluation 2020 (AME2020) database [8]. This method can establish both upper and lower analytical bounds for (B(A, Z)) and has shown extrapolation capabilities, converging at a predicted nuclear mass limit around (A \approx 338) [8]. This data-driven method offers more interpretable "white-box" models compared to neural networks.

- Density Functional Theory (DFT) and Symmetry Corrections: State-of-the-art nuclear DFT calculations provide highly accurate descriptions of ground-state properties but break fundamental symmetries like translational invariance [9]. A critical area of research involves calculating the center-of-mass (CoM) correction to the total binding energy. Different prescriptions for this correction yield significantly different results (e.g., ~19 MeV vs. ~5 MeV for Lead-208), which is larger than the root-mean-square (RMS) error of the semi-empirical mass formula itself [9]. Accurate CoM correction, for instance using the Peierls-Yoccoz projection method, is essential for achieving high-precision mass models with RMS errors approaching 1 MeV or less [9].

Table: Essential Resources for Nuclear Binding Energy Research

| Resource / "Reagent" | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| AME2020 Database [8] | The Atomic Mass Evaluation 2020 is the primary international database providing authoritative, experimentally determined atomic masses, serving as the benchmark for model development and validation. |

| National Nuclear Data Center (NuDat) [8] | A comprehensive database providing nuclear structure and decay data, essential for accessing properties of both stable and unstable nuclides. |

| Semi-Empirical Mass Formula [5] | The analytical "reagent" for generating first-principle predictions of nuclear binding energies and mass defects based on the Liquid Drop Model. |

| Continued Fraction Regression (cf-r) [8] | A symbolic regression technique used to derive analytic functions that serve as highly accurate, interpretable models for nuclear binding energy. |

| Density Functional Theory (DFT) Codes [9] | Advanced computational frameworks used for ab initio calculation of nuclear properties, including binding energies, requiring subsequent symmetry corrections. |

| Center-of-Mass (CoM) Correction [9] | A critical correction applied to DFT-calculated energies to account for the spurious kinetic energy of the nucleus's center of mass, significantly impacting the final binding energy value. |

Nuclear binding energy is a fundamental concept in nuclear physics that explains the stability of atomic nuclei and is the cornerstone for understanding phenomena from nuclear power to stellar nucleosynthesis. It is defined as the minimum energy required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons (collectively called nucleons) [3]. This energy represents the work that must be done to overcome the strong nuclear force that holds the nucleus together. Conversely, it is equal to the energy released when a nucleus is formed from its free nucleons [6] [10]. The existence of binding energy is directly tied to the mass defect, the observable phenomenon where the mass of a stable nucleus is always less than the sum of the masses of its individual protons and neutrons [6] [11] [3]. This mass difference, while small, is profound and is quantitatively related to the binding energy through Albert Einstein's mass-energy equivalence principle, E = mc² [11] [3]. The energy changes in nuclear reactions are enormous—roughly one million times greater than the electron binding energies in chemical reactions—which explains the vast energy potential locked within atomic nuclei [3].

The Physics of Mass Defect and Energy Equivalence

The mass defect is the tangible manifestation of nuclear binding energy. It is calculated as the difference between the combined mass of isolated nucleons and the actual measured mass of the nucleus [6] [1]. For a nucleus with atomic number Z (number of protons) and mass number A (total nucleons), the mass defect, Δm, is given by the formula in the table below [6].

This mass defect is not mass that is destroyed, but rather mass that has been converted into energy to bind the nucleus. According to Einstein's equation, this binding energy, E_b, is calculated as: E_b = (Δm)c², where c is the speed of light [6] [11].

To illustrate this with a practical example, the calculation for a deuteron nucleus (²H, containing one proton and one neutron) is as follows [6]:

- Mass of proton: 938.28 MeV/c²

- Mass of neutron: 939.57 MeV/c²

- Sum of constituent masses: 938.28 + 939.57 = 1877.85 MeV/c²

- Actual mass of deuteron: 1875.61 MeV/c²

- Mass defect (Δm): 1877.85 - 1875.61 = 2.24 MeV/c²

- Binding Energy (E_b): (2.24 MeV/c²) * c² = 2.24 MeV

This result means that 2.24 million electron volts of energy are required to split a deuteron into a separate proton and neutron, indicating the significant strength of the nuclear force, especially when compared to the ~10 eV required to ionize a hydrogen atom [6].

Calculating Nuclear Binding Energy: A Step-by-Step Methodology

For researchers requiring precise calculations, the process for determining the nuclear binding energy of an atom can be broken down into a standardized protocol. The following table outlines the general steps, using the specific example of a Copper-63 (⁶³Cu) nucleus to provide a clear, applicable demonstration [1].

Table 1: Protocol for Calculating Nuclear Binding Energy

| Step | General Action | Specific Example for ⁶³Cu |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Determine the nuclear composition. | Copper-63 has 29 protons and 34 neutrons (63 - 29) [1]. |

| 2 | Calculate the combined mass of the isolated nucleons. | (29 × 1.00728 amu) + (34 × 1.00867 amu) = 63.50590 amu [1]. |

| 3 | Find the mass defect (Δm). | Δm = Combined Mass - Actual Nuclear Mass. For ⁶³Cu: 63.50590 amu - actual mass = Δm. (Note: The actual mass of ⁶³Cu is needed to complete this calculation) [1]. |

| 4 | Convert the mass defect into kilograms. | 1 amu = 1.6606 × 10⁻²⁷ kg. Mass (kg) = Δm (amu) × 1.6606 × 10⁻²⁷ [1]. |

| 5 | Calculate the binding energy in joules using E = Δm c². | E_b (J) = [Δm (kg)] × (2.9979 × 10⁸ m/s)² [1]. |

| 6 | Express the binding energy in useful units. | Convert to kJ/mol (using Avogadro's number) or, more commonly, to MeV per nucleon (1 MeV = 1.602 × 10⁻¹³ J) [1]. |

This methodology provides a reproducible framework for calculating the binding energy of any nuclide, provided the necessary mass data is available.

The Binding Energy per Nucleon Curve and Nuclear Stability

A critical metric for comparing the stability of different nuclei is the binding energy per nucleon (BEN), defined as BEN = E_b / A, where A is the mass number [6]. This quantity represents the average energy required to remove a single nucleon from the nucleus. A graph of BEN versus atomic mass number reveals a fundamental curve that governs nuclear behavior and energy release [10].

The curve rises sharply for light nuclei, peaks around elements such as iron-56 and nickel, and then gradually decreases for heavier elements [3] [10]. This profile has two major implications:

- Nuclear Fusion: For light nuclei lighter than iron, merging two light nuclei to form a heavier one (fusion) moves the products up the curve toward the peak, resulting in a release of energy. This is the process that powers stars, including our Sun, where protons fuse to form helium [3] [10].

- Nuclear Fission: For very heavy nuclei (heavier than iron), splitting a heavy nucleus into two medium-mass fragments (fission) also moves the products up the curve toward the peak, thereby releasing energy. This is the principle harnessed in nuclear power reactors and weapons, typically using isotopes like uranium-235 or plutonium-239 [3] [10].

The reason for the decrease in BEN for heavy elements is the increasing positive charge of the nucleus. While the strong nuclear force is attractive and binds close neighbors, the electrostatic repulsion between protons is long-range. In a large nucleus like uranium, each proton repels all other protons. As the nucleus grows, this disruptive electrostatic force begins to dominate over the cohesive strong force, making the nucleus less tightly bound and ultimately unstable [3] [10].

The Strong Nuclear Force

The force responsible for holding nuclei together against the tremendous electrostatic repulsion of the protons is the strong nuclear force (also called the residual strong force) [3] [10]. This force has distinct characteristics that differentiate it from gravitational and electromagnetic forces:

- Short-Range Attraction: The nuclear force is powerfully attractive at very short distances (on the order of 1-2 femtometers), but falls off rapidly to insignificance at larger separations. This contrasts with the electromagnetic force, which has a much longer range [3] [10].

- Strength: Within its effective range, the strong nuclear force is about 100 times stronger than the electromagnetic force, which allows it to overcome the repulsion between protons [10].

- Acts on Nucleons: It binds protons to protons, neutrons to neutrons, and protons to neutrons [10].

An analogy for the nuclear force is the force between two small magnets: they are difficult to separate when stuck together, but once pulled a short distance apart, the force between them drops almost to zero [3]. Without this force, atomic nuclei could not exist because proton-proton repulsion would blow them apart.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Experimental and theoretical research in nuclear binding energy relies on precise data and specialized computational tools. The following table details key resources used in this field.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Nuclear Binding Energy Studies

| Resource Name | Type/Function | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometer | Experimental Instrument | Precisely measures the masses of nuclei and individual nucleons, which is the foundational data for calculating mass defects [10]. |

| Nuclear Reaction Data | Experimental Data | Results from nuclear scattering experiments are used to estimate binding energies and validate theoretical models [6]. |

| Web Application for MD & BEA | Computational Tool | Specialized software and web applications are developed to automate the calculation of mass defect (MD) and binding energy per nucleon (BEA), streamlining research workflows [12]. |

| Ame2012 Atomic Mass Evaluation | Database | Provides a comprehensive and curated collection of atomic mass data, which is essential for high-precision calculations of mass defects for various nuclides [12]. |

Nuclear binding energy is the fundamental force that dictates the stability of matter at the atomic scale. Its quantitative expression through mass defect and Einstein's E=mc² equation provides a powerful framework for understanding the universe, from the energy generation in stars to the operational principles of nuclear reactors. The characteristic curve of binding energy per nucleon serves as a universal map, guiding predictions of nuclear stability and energy release via fusion and fission. For researchers, the precise calculation of these parameters remains a critical task, supported by robust experimental data and growing computational resources, enabling continued advancement in both theoretical and applied nuclear science.

The principle of mass-energy equivalence, expressed by Albert Einstein's iconic equation (E=mc^2), represents a foundational concept in modern physics that has revolutionized our understanding of energy, matter, and their interconversion. This principle states that the energy ((E)) of a system is equal to its mass ((m)) multiplied by the speed of light ((c)) squared. The enormous magnitude of the conversion factor ((c^2 ≈ 9×10^{16}) m²/s²) reveals how minute amounts of mass can transform into colossal amounts of energy, particularly in nuclear processes [13] [14].

Within nuclear physics, this principle provides the critical theoretical foundation for understanding nuclear binding energy and the associated mass defect phenomenon. The mass defect refers to the observable difference between the mass of an atomic nucleus and the sum of the masses of its individual constituent nucleons (protons and neutrons) [15]. This "missing mass" does not vanish but rather converts into binding energy through (E=mc^2), representing the energy released when nucleons bind together to form a nucleus—or conversely, the energy required to break the nucleus apart into its separate components [15] [16] [13].

Recent research has demonstrated the ongoing relevance of these fundamental principles, particularly in cutting-edge computational fields such as quantum-enhanced drug discovery, where accurate calculation of binding energies is essential for predicting molecular interactions [17] [18]. This whitepaper explores the fundamental theory, computational methodologies, and emerging applications of mass-energy equivalence and binding energy calculations, with particular emphasis on their critical role in pharmaceutical research and development.

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Framework

Theoretical Foundation of Mass-Energy Equivalence

Einstein's special theory of relativity established that mass and energy are not separate entities but different manifestations of the same physical quantity. The relationship (E=mc^2) emerges directly from the Lorentz transformations and has profound implications for nuclear processes. In nuclear reactions, the total mass-energy remains conserved, meaning that any reduction in the total mass of a system must accompanied by a corresponding release of energy, and vice versa [13] [14].

This principle fundamentally explains why the mass of an atomic nucleus is always less than the sum of the masses of its individual protons and neutrons. This mass difference, known as the mass defect (Δm), arises because when nucleons combine to form a nucleus, a portion of their mass converts into energy that is released during the binding process. This released energy represents the binding energy that holds the nucleus together [15] [16].

Quantitative Calculation of Mass Defect and Binding Energy

The mass defect for any nuclide can be calculated using the following fundamental equation:

Δm = [Z(mₚ + mₑ) + (A-Z)mₙ] - mₐₜₒₘ [15]

Where:

- Δm = mass defect (atomic mass units, amu)

- Z = atomic number (number of protons)

- A = mass number (total number of nucleons)

- mₚ = mass of a proton (1.007277 amu)

- mₙ = mass of a neutron (1.008665 amu)

- mₑ = mass of an electron (0.000548597 amu)

- mₐₜₒₘ = measured mass of the nuclide (amu)

Once the mass defect is determined, the nuclear binding energy can be calculated through direct application of Einstein's mass-energy equivalence relationship. Using the conversion factor where 1 amu of mass corresponds to 931.5 MeV of energy, the binding energy can be expressed as [15]:

BE = Δm × (931.5 MeV/amu)

Table 1: Mass Defect and Binding Energy Calculation for Selected Nuclei

| Nucleus | Atomic Mass (amu) | Mass Defect (amu) | Binding Energy (MeV) | Binding Energy per Nucleon (MeV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium-7 | 7.016003 | 0.0421335 | ~39.25 | ~5.61 |

| Uranium-235 | 235.043924 | 1.91517 | 1784 | ~7.59 |

| Helium-4 | 4.002602 | 0.030377 | ~28.3 | ~7.08 |

The binding energy per nucleon, calculated as the total binding energy divided by the mass number (A), represents a crucial metric for evaluating nuclear stability. This quantity varies systematically across the periodic table, increasing rapidly from light elements to a broad maximum around iron-56 (approximately 8.8 MeV per nucleon), then gradually decreasing for heavier elements. This pattern explains why energy can be released through both nuclear fusion (for elements lighter than iron) and nuclear fission (for elements heavier than iron) [15] [13].

Computational Methodologies for Binding Energy Analysis

Traditional Quantum Chemical Approaches

Calculating binding energies in molecular systems requires sophisticated computational methods that account for quantum mechanical effects. Traditional approaches include:

Wavefunction-based methods: These include coupled cluster theory and NEVPT2, which provide high accuracy but suffer from exponential scaling with system size, limiting application to small molecules [17] [18].

Density Functional Theory (DFT): More computationally efficient than wavefunction methods but often struggles with complex electronic structures, particularly for transition metal complexes and open-shell systems [17] [18].

These classical computational methods become prohibitively expensive for large biomolecular systems due to the exponential scaling of memory requirements with electron count [18].

Emerging Quantum Computing Approaches

Quantum computers offer a potential solution to the scaling problems of classical computational chemistry methods. By representing quantum states naturally with qubits, quantum algorithms can theoretically simulate quantum mechanical systems with polynomial rather than exponential resource scaling [17] [18].

Promising quantum algorithms for binding energy calculations include:

Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE): Provides highly accurate energy calculations but requires fault-tolerant quantum computers [17].

Qubitization techniques: More resource-efficient approaches for quantum simulation [17] [18].

Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE): Suitable for near-term quantum devices with limited qubit counts and coherence times [18].

Resource estimates indicate that approximately 1,000 logical qubits would be required to compute binding energies for complex molecular systems like ruthenium-based anticancer drugs with chemical accuracy, with gate fidelities below (10^{-7}) and logical gate times below (10^{-7}) seconds [17].

Experimental Protocols and Research Applications

Protocol: FreeQuantum Computational Pipeline for Biomolecular Binding Energies

The FreeQuantum pipeline represents an integrated computational framework for calculating binding free energies with quantum-mechanical accuracy, specifically designed for biomolecular systems [17] [18].

Experimental Workflow for FreeQuantum Pipeline

System Preparation and Sampling

Quantum Embedding and Core Selection

High-Accuracy Energy Calculations

- Perform electronic structure calculations on quantum cores using wavefunction-based methods (NEVPT2, coupled cluster) or quantum computing algorithms

- Calculate potential energy surfaces for selected configurations

- For the ruthenium-based anticancer drug test system, approximately 4,000 energy points are typically required [17]

Machine Learning Potential Training

Free Energy Calculation

Application: Pharmaceutical Drug Development

The FreeQuantum pipeline has been experimentally validated on the NKP-1339 ruthenium-based anticancer drug binding to its protein target GRP78. This system presents particular challenges for classical force fields due to the open-shell electronic structure and strong correlation effects of the ruthenium center [17] [18].

The quantum-accurate FreeQuantum pipeline predicted a binding free energy of -11.3 ± 2.9 kJ/mol, substantially different from the -19.1 kJ/mol predicted by classical force fields. This discrepancy of approximately 7.8 kJ/mol is highly significant in pharmaceutical contexts, where energy differences of 5-10 kJ/mol can determine whether a drug candidate successfully binds to its target [17].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Energy Calculations

| Research Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Force Fields | Provide initial configurational sampling and molecular dynamics | Baseline molecular simulations before quantum refinement |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Perform high-accuracy electronic structure calculations | Wavefunction-based methods (NEVPT2, coupled cluster) for quantum cores |

| Machine Learning Potentials | Bridge quantum accuracy with molecular dynamics sampling | Trained on quantum data to enable large-scale simulations |

| Quantum Computing Hardware | Execute quantum algorithms for electronic structure | Future replacement for classical quantum chemistry calculations |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Sample configurational space and calculate free energies | Implement advanced sampling methods for binding free energy calculation |

Current Research and Emerging Applications

Quantum Computing for Pharmaceutical Research

Recent research demonstrates how quantum computers can potentially revolutionize binding energy calculations in drug discovery. The FreeQuantum computational pipeline is explicitly designed as a quantum-ready framework that can integrate quantum computing resources as they become available [17] [18] [19].

This approach combines the theoretical exponential speedups of quantum computers for simulating interacting electrons with modern classical simulation techniques that incorporate machine learning to model large molecules. The pipeline employs a two-fold quantum embedding strategy where the innermost quantum cores are treated at a very high level of accuracy, either through traditional quantum chemical methods or future quantum computations [18].

Current research focuses on identifying the specific requirements for achieving quantum advantage in biochemical simulations, including necessary qubit counts, gate fidelities, and error correction thresholds. Estimates suggest that with approximately 1,000 logical qubits and gate fidelities below (10^{-7}), quantum computers could compute binding energies for pharmaceutically relevant systems within practical timeframes [17].

Nuclear Physics and Energy Applications

While pharmaceutical applications represent emerging frontiers, the fundamental principles of mass-energy equivalence continue to drive essential applications in nuclear energy:

Nuclear fission power plants utilize the mass defect in heavy elements like uranium-235, where approximately 0.1% of the mass converts to usable energy according to (E=mc^2) [13] [14].

Nuclear fusion research aims to harness the greater mass-to-energy conversion efficiency (up to 0.7%) available from light elements like hydrogen isotopes fusing to form helium [13].

Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars like our Sun continuously converts approximately 4 million tons of mass to energy every second through fusion processes [14].

The relationship between binding energy per nucleon and atomic number explains why energy release occurs in both fission (splitting heavy nuclei) and fusion (combining light nuclei), as both processes move reaction products toward the minimum of the "energy valley" at iron-56 [13].

Einstein's principle of mass-energy equivalence, (E=mc^2), continues to provide fundamental insights into nuclear processes while enabling cutting-edge research across scientific disciplines. From its foundational role in understanding nuclear binding energies and mass defects to its emerging applications in quantum-computing-enhanced drug discovery, this principle remains vital to both theoretical and applied scientific research.

The ongoing development of computational frameworks like the FreeQuantum pipeline demonstrates how first principles of physics can translate into practical methodologies with significant potential for pharmaceutical innovation. As quantum computing hardware continues to advance, the integration of these fundamental physical principles with novel computational architectures promises to open new frontiers in our ability to understand and manipulate molecular interactions at the quantum level.

The Strong Nuclear Force vs. Electrostatic Repulsion

Within the atomic nucleus, a continuous contest between two fundamental forces determines the very stability of matter. The strong nuclear force and the electrostatic force engage in a delicate balance, the outcome of which dictates whether a nucleus remains bound or undergoes radioactive decay. This dynamic is not merely of academic interest; it is the cornerstone of nuclear binding energy, which in turn is the physical basis for the mass defect observed in all atomic nuclei. The energy released in both nuclear fission power plants and fusion reactions in stars originates from this fundamental interaction. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the competition between these forces, framed within essential research on nuclear binding energy and its critical role in mass defect calculations, providing scientists with the quantitative data and methodologies central to this field.

Fundamental Forces in the Nucleus

The Strong Nuclear Force

The strong nuclear force, also referred to as the residual strong force, is the powerful attractive force that acts between nucleons—protons and neutrons—within the nucleus [20]. Its most critical characteristic is its extremely short range, being powerfully attractive at distances of about 0.8 femtometres (fm) between nucleon centers, maximal at approximately 0.9 fm, and decreasing exponentially to become negligible beyond about 2.5 fm [21] [20]. This force is responsible for binding nucleons into atomic nuclei and must overcome the electrostatic repulsion between protons to do so.

A unique property of the strong nuclear force is that it is charge-independent; it acts almost identically between two protons, two neutrons, or a proton and a neutron [20]. However, it possesses a significant spin-dependent component, being stronger between nucleons with aligned spins [20]. At very short separations (less than approximately 0.7 fm), the nuclear force becomes repulsive, which prevents the collapse of the nucleus and defines the minimum distance between nucleons [21] [20].

The Electrostatic Repulsion

The electrostatic force, or Coulomb force, is the long-range repulsive force between the positively charged protons in the nucleus. Unlike the strong nuclear force, its range is effectively infinite, varying as the inverse square of the charge separation. While it is immensely weaker than the strong force at femtometre-scale distances, it dominates the interaction between protons when their separation exceeds about 2 to 2.5 fm [20]. This persistent repulsion poses the primary challenge to nuclear stability, particularly in larger nuclei.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Nuclear Forces

| Property | Strong Nuclear Force | Electrostatic Force |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Attractive (at ~0.8-2.5 fm); Repulsive (< ~0.7 fm) | Exclusively Repulsive between protons |

| Acting Between | Nucleons (Protons & Neutrons) | Protons only |

| Range | Short (~2.5 fm) | Long (Inverse-square law) |

| Relative Strength | Strongest at short range | Weaker at short range, dominant at long range |

| Spin Dependence | Strongly spin-dependent | Spin-independent |

Force Balance and Nuclear Stability

The stability of an atomic nucleus is a direct consequence of the equilibrium between the attractive strong nuclear force and the repulsive electrostatic force. For most stable nuclei, the net internucleon potential energy is negative, meaning the attractive strong force prevails. However, this balance is fragile and depends heavily on the nucleus's composition and size.

The Role of Neutrons and the Neutron-to-Proton Ratio

Neutrons are crucial for stability because they contribute to the strong nuclear force without adding electrostatic repulsion [21]. Adding neutrons increases the total magnitude of the attractive strong force within the nucleus, helping to "glue" the protons together. Consequently, the stable neutron-to-proton (n/p) ratio increases with the atomic number (Z).

- For lighter elements (Z < 20), a stable n/p ratio is approximately 1:1 [21].

- For larger elements, the stable n/p ratio becomes greater than 1, requiring an increasing number of neutrons to counteract the growing cumulative electrostatic repulsion between the larger number of protons [21].

An imbalance in this ratio is a primary cause of nuclear instability. If the n/p ratio is too low (excess protons), electrostatic repulsion overwhelms the strong force. Conversely, if the n/p ratio is too high (excess neutrons), the average distance between nucleons can become so small that the strong force becomes repulsive, also leading to instability [21]. Furthermore, all isotopes of elements with an atomic number greater than 83 are unstable because the electrostatic repulsion becomes too immense for the strong nuclear force to contain [21].

Nuclear Binding Energy and Mass Defect

The work required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent, free nucleons is known as the nuclear binding energy. This energy is equivalent to the potential energy stored by the nuclear force holding the nucleus together. According to the mass-energy equivalence principle (E = mc²), this binding energy has mass [20].

When a nucleus is formed, energy is released, resulting in the nucleus having less mass than the sum of its individual protons and neutrons. This difference is the mass defect [20]. The mass defect is the physical manifestation of the nuclear binding energy. Accurate calculation of this mass defect is fundamental to predicting the energy released in nuclear reactions like fission and fusion, which is a key area of research in both energy production and basic nuclear science [12].

Table 2: Mass Defect and Binding Energy Calculation for a Deuterium Nucleus (Example) Assumed mass data for illustration: Proton = 1.00728 u, Neutron = 1.00866 u, Deuterium nucleus = 2.01355 u.

| Parameter | Value | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Calculated Mass of Constituents | 2.01594 u | Sum of 1 proton and 1 neutron mass. |

| Measured Mass of Deuterium Nucleus | 2.01355 u | Experimentally determined mass. |

| Mass Defect (Δm) | 0.00239 u | Difference between calculated and measured mass. |

| Binding Energy (E) | ~2.22 MeV | Energy equivalent of the mass defect (1 u = 931.5 MeV/c²). |

The relationship between nuclear composition and its ultimate stability can be visualized through the following logical pathway:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Quantifying the effects of the strong nuclear force and electrostatic repulsion relies on sophisticated experimental techniques. The following protocols outline key methods for measuring nuclear binding energies and probing nucleon interactions.

Protocol for Mass Spectrometry to Determine Mass Defect

Objective: To precisely measure the atomic mass of a nuclide, enabling the calculation of its mass defect and binding energy.

- Sample Preparation: The element of interest is chemically processed into a volatile compound suitable for vaporization and ionization.

- Ionization: The sample vapor is bombarded with electrons in an ionization chamber, producing positively charged ions of the isotope.

- Acceleration: The ions are accelerated through a strong electrostatic field (typically several kilovolts), giving them a uniform kinetic energy.

- Momentum Separation: The ion beam enters a magnetic field perpendicular to its path. Ions are deflected into circular paths with radii of curvature proportional to their momentum-to-charge ratio (m/z). Lighter ions are deflected more than heavier ones.

- Detection: A detector at a fixed position measures the intensity of the resolved ion beams. The magnetic field strength is varied to bring different m/z ions into focus.

- Data Analysis:

- The precise mass (m) of the isotope is determined by calibrating the instrument with nuclides of known mass.

- The mass defect is calculated: Δm = (Z⋅mp + N⋅mn) - m_nucleus.

- The binding energy (B.E.) is derived: B.E. = Δm ⋅ c² (typically expressed in MeV).

Protocol for Nucleon-Nucleon Scattering Experiments

Objective: To empirically determine the properties of the nucleon-nucleon (NN) force, such as its spin-dependence and interaction potential.

- Beam Generation: A beam of nucleons (protons or neutrons) is produced and accelerated to high energies (tens to hundreds of MeV) using a particle accelerator like a cyclotron or synchrotron.

- Target Preparation: A stationary target containing the other type of nucleon is prepared (e.g., a liquid hydrogen target for proton-neutron scattering).

- Collision and Detection: The particle beam is directed at the target. The angles and energies of the scattered nucleons are measured by an array of particle detectors surrounding the interaction point.

- Cross-Section Measurement: The differential cross-section (a measure of the probability of scattering at a specific angle) is measured as a function of the scattering angle and the spin states of the nucleons.

- Potential Fitting: The experimental cross-section data is used to fit parameters in phenomenological models of the internucleon potential, such as the Yukawa potential or more modern potentials (e.g., Argonne V18). These potentials quantitatively describe the NN force as a function of distance, spin, and isospin [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and tools used in experimental nuclear physics research related to binding energy and force interactions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nuclear Force Experiments

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Targets | Purified samples of specific isotopes (e.g., H-2, C-12, Pb-208) used as targets in scattering experiments to study nuclear structure and forces. |

| Particle Accelerator | A device (e.g., cyclotron, synchrotron) that accelerates charged particles (protons, ions) to high energies, providing the beam for scattering and reaction studies. |

| Mass Spectrometer | An instrument for determining the precise atomic masses of nuclides, which is the direct input for calculating the mass defect and binding energy. |

| Radiation Detectors | Sensors (e.g., semiconductor detectors, scintillators) to identify and measure the energy and trajectory of particles resulting from nuclear reactions or decays. |

| Phenomenological Potential Models | Mathematical frameworks (e.g., Yukawa potential, Skyrme force) with fitted parameters used to quantitatively describe the nuclear force between nucleons [20]. |

The workflow for a comprehensive research project integrating these tools is outlined below, showing the path from initial experiment to theoretical refinement:

The intricate balance between the strong nuclear force and electrostatic repulsion is a fundamental principle of nature with profound implications. The strong force's short-range, spin-dependent attraction provides the necessary binding to overcome the relentless Coulomb repulsion between protons, but this balance is precarious. It directly dictates nuclear stability, governs the neutron-to-proton ratio across the nuclear chart, and is the physical origin of the nuclear binding energy and its associated mass defect. Ongoing research, employing advanced scattering experiments and precision mass spectrometry, continues to refine our quantitative understanding of the nucleon-nucleon force. This knowledge is not merely academic; it is essential for advancing fields ranging from nuclear energy and astrophysical nucleosynthesis to the fundamental theory of strong interactions, Quantum Chromodynamics.

This technical guide examines the fundamental role of nuclear binding energy per nucleon (BEN) in quantifying atomic nucleus stability. Within the context of mass defect calculations research, we establish how BEN provides the crucial link between measured mass deficits and the energy landscape governing nuclear stability. We present comprehensive methodologies for experimental determination, quantitative analysis of stability trends across the nuclide chart, and computational protocols for deriving binding energies from mass defect measurements. The analysis confirms that the BEN curve explains why iron-group nuclei represent stability maxima while lighter and heavier nuclei can release energy through fusion and fission processes, respectively.

Fundamental Concepts and Theoretical Framework

Mass Defect and Nuclear Binding Energy

Mass defect (Δm) is a fundamental phenomenon in nuclear physics referring to the difference between the mass of an intact nucleus and the sum of the masses of its constituent protons and neutrons [6] [3]. This mass discrepancy arises because when nucleons combine to form a nucleus, a portion of their mass is converted into energy released during nucleus formation according to Einstein's mass-energy equivalence principle, E=mc² [11] [3]. The mass defect is quantitatively defined by:

Δm = (Z⋅mₚ + N⋅mₙ) − M_nuc [6] [22]

where Z is the atomic number (proton count), N is the neutron count, mₚ is the proton mass (1.00728 u), mₙ is the neutron mass (1.00867 u), and M_nuc is the measured nuclear mass [22] [4].

Nuclear binding energy (E_b) represents the energy equivalent of this mass defect and corresponds to the minimum energy required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons [6] [3]. The binding energy is calculated directly from the mass defect using Einstein's relation:

E_b = (Δm)c² [6]

For nuclei with mass number A > 8, the total binding energy is roughly proportional to the total number of nucleons [6]. This relationship leads to the crucial concept of binding energy per nucleon, defined as BEN = E_b/A, which serves as the primary metric for assessing nuclear stability [6] [23].

The Binding Energy per Nucleon Curve

The binding energy per nucleon (BEN) exhibits a characteristic pattern when plotted against atomic mass number (A), forming what is known as the binding energy curve [6] [23]. This curve reveals fundamental insights into nuclear stability and energy-releasing processes:

- Rapid increase for light nuclei (A < 16) followed by a broad maximum around A = 56-62 (iron-nickel region)

- Gradual decrease for heavier nuclei (A > 62)

- Peak stability at nickel-62 (highest BEN), followed closely by iron-58 and iron-56 [24] [23]

Table 1: Representative Binding Energy per Nucleon Values Across the Nuclear Chart

| Nuclide | Mass Number (A) | Binding Energy per Nucleon (MeV/nucleon) | Nuclear Stability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterium | 2 | 1.12 | Low |

| Helium-4 | 4 | 7.07 | Medium |

| Carbon-12 | 12 | 7.68 | Medium |

| Iron-56 | 56 | 8.79 | High |

| Nickel-62 | 62 | ~8.80 (maximum) | Highest |

| Uranium-238 | 238 | ~7.57 | Low |

The BEN curve fundamentally explains why nuclear fusion is energetically favorable for light elements and nuclear fission for heavy elements. Both processes move reaction products toward the iron peak, where binding energy per nucleon is maximized [3] [23].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Mass Defect Calculation Protocol

Objective: Determine the mass defect and subsequent binding energy for a specific nuclide using precise mass measurements.

Materials and Equipment:

- High-precision mass spectrometer for atomic mass determination

- Reference tables for fundamental particle masses (proton: 1.00728 u, neutron: 1.00867 u)

- Computational tools for energy unit conversions

Procedure:

Identify Nuclear Composition

- Determine atomic number (Z) from the periodic table

- Calculate neutron number (N) = Mass number (A) - Atomic number (Z)

- Verify nuclear charge state (neutral atoms have Z electrons)

Calculate Predicted Mass

Determine Mass Defect

- Obtain experimentally measured nuclear mass (M_nuc) from reference data

- Calculate Δm = Predicted mass - M_nuc [22]

Convert to Binding Energy

- Apply Einstein's equation: E_b = (Δm)c²

- Convert mass units (u) to energy units (MeV) using 1 u = 931.5 MeV/c² [3]

Compute Binding Energy per Nucleon

- BEN = E_b / A [6]

Example Calculation: Deuterium (²H)

- Composition: 1 proton, 1 neutron, 1 electron

- Predicted mass = (1 × 1.00728) + (1 × 1.00867) + (1 × 0.00055) = 2.01650 u

- Measured deuterium mass = 2.01410 u

- Mass defect = 2.01650 u - 2.01410 u = 0.00240 u

- Binding energy = 0.00240 u × 931.5 MeV/u = 2.24 MeV

- BEN = 2.24 MeV / 2 = 1.12 MeV/nucleon [6]

Nuclear Stability Assessment Protocol

Objective: Evaluate nuclear stability through neutron-to-proton ratio analysis and position relative to the valley of stability.

Materials and Equipment:

- Chart of nuclides (Segrè chart)

- Nuclear decay radiation detectors

- Half-life measurement apparatus

Procedure:

Plot Position on Nuclide Chart

Assess Neutron-to-Proton Ratio

Evaluate Decay Mode Predictions

Measure Half-Life

- Determine decay constant (λ) through activity measurements

- Calculate half-life: t₁/₂ = ln(2)/λ [23]

Quantitative Analysis of Nuclear Stability

The Valley of Stability and Nuclear Landscape

The "valley of stability" represents a characterization of nuclide stability based on binding energy as a function of proton and neutron numbers [24]. This conceptual model organizes nuclides according to their energy landscape:

- Bottom of the valley: Corresponds to the most stable nuclides with highest binding energies [24]

- Sides of the valley: Represent increasingly unstable nuclides that undergo radioactive decay to move toward stability [24]

- Line of beta stability: The central line of most stable nuclides where N/Z ratio increases with atomic number [24]

Table 2: Neutron-to-Proton Ratio Evolution Across the Valley of Stability

| Element Group | Atomic Number Range | Stable N/Z Ratio | Dominant Decay Modes for Unstable Nuclei |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Elements | 1-20 | ~1.0 | β⁻, β⁺ |

| Medium Elements | 20-50 | 1.0-1.3 | β⁻, β⁺, electron capture |

| Heavy Elements | 50-82 | 1.3-1.5 | β⁻, α decay |

| Very Heavy Elements | >82 | >1.5 | α decay, spontaneous fission |

The valley's shape reflects the balancing act between the attractive nuclear force (short-range) and repulsive electrostatic force (long-range) [24] [3]. As atomic number increases, additional neutrons are required to provide sufficient nuclear force to counteract the growing proton-proton repulsion, leading to the increasing N/Z ratio along the valley of stability [24].

Mass Defect and Binding Energy Correlation

The direct relationship between mass defect and binding energy provides the foundation for calculating nuclear stability parameters. Research in mass defect calculations consistently demonstrates:

- Larger mass defects correlate with higher binding energies and increased nuclear stability [6] [3]

- The most stable nuclei (iron-nickel region) exhibit the largest mass defects per nucleon [24] [23]

- Mass defect measurements provide experimental verification of theoretical nuclear models [6] [1]

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Nuclear Binding Energy Studies

| Research Tool | Specifications | Experimental Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Mass Spectrometer | Resolution: ≤10⁻⁸ u | Atomic mass measurement | Fundamental for mass defect determination [6] |

| Segrè Chart (Nuclide Map) | Comprehensive nuclide database | Visualization of nuclear stability | Positioning nuclides relative to valley of stability [24] [23] |

| Nuclear Decay Detectors | Gamma-ray spectroscopy capable | Radiation measurement and identification | Decay mode analysis and half-life determination [23] |

| Semi-Empirical Mass Formula Coefficients | aᵥ: ~15.8 MeV, aₛ: ~18.0 MeV, a𝒸: ~0.7 MeV, aₐ: ~23.0 MeV | Theoretical binding energy calculation | Comparison with experimental values [24] |

| Mass-Energy Conversion Constants | 1 u = 931.494 MeV/c², 1 eV = 1.602×10⁻¹⁹ J | Unit conversion | Translating mass defect to binding energy [3] [1] |

Binding energy per nucleon serves as the fundamental metric for quantifying nuclear stability, with direct implications for mass defect calculations research. The characteristic BEN curve, peaking at iron-group elements, explains the energy release mechanisms in both stellar nucleosynthesis (fusion) and nuclear technologies (fission). Experimental protocols for mass defect measurement provide critical data for verifying nuclear models and understanding stability trends across the valley of stability. Continuing research in precision mass measurements and nuclear theory development further refines our understanding of the binding energy landscape, particularly in regions far from stability where nuclear structure models face ongoing challenges.

The Significance of Mass-Energy Balance in Nuclear Reactions

This technical guide examines the fundamental role of mass-energy balance in nuclear reactions, contextualized within research on nuclear binding energy and mass defect calculations. The principle of mass-energy equivalence, as articulated by Einstein's equation E=mc², provides the theoretical foundation for quantifying energy changes in nuclear processes. This whitepaper details methodologies for calculating mass defects and binding energies, presents curated nuclear data resources, and establishes experimental protocols for researchers investigating nuclear phenomena. The comprehensive analysis underscores how precise mass-energy balance calculations enable accurate prediction of reaction energies, stability of nuclides, and energy yields in both fission and fusion processes, with significant implications for energy production and scientific applications.

Nuclear reactions involve energy changes that are enormously larger than those in chemical reactions, resulting in measurable mass changes governed by Einstein's mass-energy equivalence principle, E=mc² [25]. In this equation, E represents energy, m represents mass, and c is the speed of light (2.998×10⁸ m/s) [25]. The direct proportionality between mass and energy means that any exothermic reaction is accompanied by a decrease in mass, while endothermic reactions involve an increase in mass [25]. These mass changes, while negligible in chemical reactions, become significant in nuclear contexts due to the substantial energies involved.

The concept of mass defect is fundamental to understanding nuclear stability and energy balances. Mass defect refers to the difference between the mass of a fully formed nucleus and the sum of the masses of its individual nucleons (protons and neutrons) [1] [26]. This "missing mass" has been converted into energy during nucleus formation and represents the nuclear binding energy—the energy required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons [1]. Research within nuclear binding energy and mass defect calculations focuses on precisely quantifying these relationships to predict reaction energies, nuclear stability, and energy yields in applications ranging from power generation to medical isotopes.

Theoretical Foundation: Mass Defect and Binding Energy

Quantitative Analysis of Mass-Energy Balance

The mass-energy balance in nuclear reactions follows the conservation law where the total energy, including rest mass energy and kinetic energy, remains constant. The Q-value of a reaction represents the energy released or absorbed and can be calculated as the difference between the sum of masses on the initial side and the final side [27]. For a general nuclear reaction where a target nucleus A interacts with a projectile B to produce C and D:

[ A + B \rightarrow C + D + Q ]

The Q-value is calculated as:

[ Q = (mA + mB - mC - mD)c^2 ]

A positive Q-value indicates an exothermic reaction (energy released), while a negative Q-value indicates an endothermic reaction (energy required) [27]. This differs from the convention in chemistry and provides a direct measure of the energy released or absorbed during the nuclear transformation.

Nuclear Binding Energy Per Nucleon

The nuclear binding energy quantifies the stability of nuclides. A higher binding energy per nucleon indicates greater stability. The binding energy per nucleon curve reveals why energy is released in both fission (splitting heavy nuclei) and fusion (combining light nuclei) [25]. For most elements, the binding energy per nucleon ranges from 1-9 MeV, vastly exceeding the few eV range typical of electron binding energies in atoms, explaining why nuclear reactions yield millions of times more energy than chemical reactions [26].

Table 1: Fundamental Particle Masses and Energy Equivalents [26]

| Particle | Mass (kg) | Mass (u) | Mass (MeV/c²) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Mass Unit (u) | 1.660540×10⁻²⁷ | 1.000000 | 931.5 |

| Neutron | 1.674929×10⁻²⁷ | 1.008664 | 939.57 |

| Proton | 1.672623×10⁻²⁷ | 1.007276 | 938.28 |

| Electron | 9.109390×10⁻³¹ | 0.00054858 | 0.511 |

Methodology for Mass Defect and Binding Energy Calculations

Experimental Protocol: Calculating Nuclear Binding Energy

The calculation of nuclear binding energy follows a systematic three-step methodology applicable across nuclides [1]:

Step 1: Determine Mass Defect

- Identify the nuclide's composition (number of protons Z and neutrons N)

- Calculate combined mass of separated nucleons: [ \text{Mass}{\text{nucleons}} = Z \times mp + N \times m_n ]

- Subtract the actual measured nuclear mass: [ \Delta m = \text{Mass}{\text{nucleons}} - \text{Mass}{\text{nucleus}} ]

Step 2: Convert Mass Defect to Energy

- Convert mass defect from atomic mass units to kilograms: [ 1 \, \text{u} = 1.6606 \times 10^{-27} \, \text{kg} ]

- Apply Einstein's equation: [ E = \Delta m \cdot c^2 ] where c = 2.9979 × 10⁸ m/s [1]

Step 3: Express Binding Energy Appropriately

- For per-nucleon values: Divide total binding energy by mass number A

- For molar quantities: Multiply by Avogadro's number (6.022 × 10²³ mol⁻¹)

- For MeV conversion: Use 1 u = 931.5 MeV/c² [26]

Case Study: Binding Energy Calculation for Copper-63

The methodology can be illustrated with a copper-63 (⁶³Cu) calculation example [1]:

Table 2: Mass Defect and Binding Energy Calculation for Copper-63 [1]

| Parameter | Calculation | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Protons | 29 | 29 |

| Neutrons | 63 - 29 | 34 |

| Proton Mass Contribution | 29 × 1.00728 u | 29.21112 u |

| Neutron Mass Contribution | 34 × 1.00867 u | 34.29478 u |

| Total Nucleon Mass | 29.21112 u + 34.29478 u | 63.50590 u |

| Measured Nuclear Mass | From experimental data | 62.91367 u |

| Mass Defect (Δm) | 63.50590 u - 62.91367 u | 0.59223 u |

| Energy Equivalent | 0.59223 u × 931.5 MeV/u | 551.66 MeV |

| Binding Energy per Nucleon | 551.66 MeV / 63 nucleons | 8.76 MeV |

This calculation demonstrates that the copper-63 nucleus has a binding energy of 8.76 MeV per nucleon, consistent with typical values for medium-mass nuclides and reflecting its relative stability.

Table 3: Essential Nuclear Data Resources and Research Tools

| Resource | Type | Function | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| EXFOR Library | Experimental Database | Compilation of experimental nuclear reaction data from >22,000 experiments | IAEA [28] |

| Evaluated Nuclear Structure Data Files (ENSDF) | Reference Data | Evaluated nuclear structure and decay data | National Nuclear Data Center [29] |

| Atomic Mass Data Center | Specialized Database | Evaluated, experimental, and theoretical atomic mass data | International Network [29] |

| Chart of Nuclides | Visualization Tool | Interactive table of nuclides with nuclear properties | Various Institutions [29] |

| REACLIB | Reaction Rate Database | Comprehensive nuclear reaction rates | Joint Institute for Nuclear Astrophysics [27] |

| JANIS | Software Tool | Java-based nuclear data display program | OECD Nuclear Energy Agency [29] |

| Starlib | Library | Next-generation thermonuclear reaction rates | Research Collaboration [29] |

| NACRE | Compiled Database | Nuclear astrophysics compilation of reaction rates | International Collaboration [29] |

Nuclear Reaction Kinetics and Energetics

Factors Influencing Nuclear Reaction Rates

Unlike chemical reactions, nuclear reaction rates depend on fundamentally different factors [27]:

- Particle Energy and Flux: The energy distribution and flux density of incident particles directly determine reaction probability

- Reaction Cross Section: The effective target area presenting probability of interaction, which varies dramatically with energy

- Coulomb Barrier: For charged particles, the electrostatic repulsion must be overcome, requiring high initial energies

- Neutron Energy Dependence: Low-energy (thermal) neutrons often have higher reaction probabilities due to increased de Broglie wavelengths and resonance effects

Comparative Analysis of Nuclear vs. Chemical Energy Changes

The energy scale of nuclear processes vastly exceeds chemical reactions due to the strength of the nuclear force compared to electromagnetic interactions. For illustration, the combustion of graphite releases approximately 393.5 kJ/mol [25], while nuclear reactions typically release energy on the order of millions or billions of kJ/mol. This difference originates from the binding energy per nucleon (MeV range) being approximately six orders of magnitude greater than electron binding energies (eV range) [26].

Diagram 1: Energy comparison between nuclear and chemical reactions

Advanced Computational Methods and Data Applications

Mass-Energy Balance in Reaction Analysis

The systematic calculation of reaction energies follows a standardized approach, as demonstrated in this lithium-deuterium reaction example [27]:

Reaction: ⁶Li + d → α + α (where d represents deuterium and α represents helium-4)

Mass Analysis:

- Rest mass of ⁶Li nucleus: 6.015 Da

- Rest mass of deuterium nucleus: 2.014 Da

- Total initial rest mass: 8.029 Da

- Rest mass of two α-particles: 2 × 4.0026 Da = 8.0052 Da

- Mass defect: 8.029 Da - 8.0052 Da = 0.0238 Da

Energy Calculation:

- Energy equivalent: 0.0238 Da × 931.5 MeV/Da = 22.2 MeV

- This substantial energy release (22.2 MeV) reflects the exceptional stability of the helium-4 nucleus, which is "doubly magic" with particularly high binding energy per nucleon [27].

Experimental Workflow for Nuclear Reaction Studies

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for nuclear reaction analysis

The precise calculation of mass-energy balance in nuclear reactions represents a cornerstone of nuclear science with far-reaching implications for both theoretical research and practical applications. The direct relationship between mass defect and nuclear binding energy, governed by E=mc², enables accurate prediction of reaction energies, stability patterns across the nuclide chart, and energy yields in nuclear technologies. Continued refinement of mass measurement techniques, expansion of nuclear databases, and development of more sophisticated computational models will further enhance our ability to harness nuclear processes for energy production, scientific research, and technological innovation. The integration of comprehensive nuclear data resources with robust calculation methodologies ensures that researchers can reliably apply mass-energy balance principles to advance the field of nuclear science.

Practical Calculations: From Mass Defect to Energy Output in Nuclear Processes

Step-by-Step Calculation of Mass Defect for Common Isotopes

This technical guide elucidates the fundamental principles and detailed methodologies for calculating the mass defect of atomic nuclei, a cornerstone concept in nuclear physics. The mass defect, representing the difference between the sum of the masses of an atom's constituent particles and its actual measured mass, provides direct insight into the nuclear binding energy via Einstein's mass-energy equivalence principle, E=mc². This paper frames these calculations within the broader research context of nuclear binding energy's role in determining nuclear stability and its critical applications spanning from astrophysical nucleosynthesis to medical drug development. We provide standardized protocols, consolidated quantitative data, and visual workflows to ensure reproducibility and clarity for researchers and industry professionals engaged in nuclear science, radiopharmaceutical development, and related fields.

Nuclear binding energy is the minimum energy required to disassemble a nucleus into its constituent protons and neutrons [3]. This energy is a direct manifestation of the strong nuclear force, which binds nucleons together at short ranges, overcoming the electrostatic repulsion between protons [3]. The mass defect is the observable mass difference equivalent to this binding energy. When a nucleus is formed, a small portion of the mass of its nucleons is converted into energy and released, resulting in a nucleus that is lighter than the sum of its parts [6] [3]. This "missing mass" is the mass defect, Δm.

The relationship between mass defect and binding energy is quantitatively described by Albert Einstein's renowned equation:

where E_b is the binding energy, Δm is the mass defect, and c is the speed of light [6] [30]. For stable nuclei, the binding energy is positive, indicating that energy is released during formation and must be supplied to break the nucleus apart [3]. The binding energy per nucleon (BEN), calculated as E_b/A (where A is the mass number), is a key indicator of nuclear stability, generally increasing with mass number up to iron-56 and decreasing thereafter [6] [30]. This pattern explains why energy can be released by both the fusion of light elements and the fission of heavy elements.

Theoretical Framework and Foundational Equations

The calculation of mass defect is grounded in the comparison of a nucleus's measured mass with the summed mass of its isolated constituents.

Defining the Mass Defect

For a nucleus, the mass defect is the difference between the total mass of its constituent nucleons and its actual nuclear mass [30]. In practical calculations, it is often more convenient to use atomic masses, which include the mass of the atom's electrons. The mass defect for a neutral atom, Δm, with atomic number Z and mass number A, is given by:

or, using atomic masses [6]:

where:

m_pis the mass of a proton,m_nis the mass of a neutron,m(^1\text{H})is the mass of a neutral hydrogen-1 atom,m_{\text{nuc}}is the mass of the nucleus,m(\text{Atom})is the measured atomic mass of the isotope.

Using atomic masses automatically accounts for the binding energy of the orbital electrons, simplifying the calculation while maintaining high accuracy [6].

The Mass-Energy Equivalence

The binding energy E_b is derived from the mass defect using Einstein's relation [6] [30] [3]:

The choice of units for mass determines the units of energy. When mass is in kilograms (kg) and the speed of light is in meters per second (m/s), the resulting energy is in joules (J). In nuclear physics, it is more practical to use atomic mass units (u) for mass and mega-electronvolts (MeV) for energy. The conversion factor is derived as follows:

Therefore, the binding energy in MeV can be calculated from a mass defect in u as [30]:

Table 1: Fundamental Constants and Conversion Factors for Mass Defect Calculations

| Constant/Quantity | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proton Rest Mass | m_p |

1.007276 | u [4] |

| Neutron Rest Mass | m_n |

1.008665 | u [4] |

| Electron Rest Mass | m_e |

0.00054858 | u [4] |

| Hydrogen-1 Atom Mass | m(^1\text{H}) |

1.007825 | u [31] |

| Atomic Mass Unit | u |

1.660539 × 10⁻²⁷ | kg [4] |

| Speed of Light | c |

2.99792458 × 10⁸ | m/s |

| Energy Conversion | 1 u ⋅ c² |

931.494 | MeV/u |

Experimental and Computational Protocols

This section outlines the standard methodologies for determining mass defects, from direct calculation to advanced theoretical modeling.

Standard Protocol for Calculating Mass Defect

The following step-by-step protocol allows researchers to calculate the mass defect and binding energy for any given isotope.

Step 1: Identify Nuclear Composition

Determine the atomic number (Z) and mass number (A) of the isotope. The number of neutrons is N = A - Z. For a neutral atom, the number of electrons is equal to Z.

Step 2: Obtain Precise Mass Values

Acquire the accurately measured mass of the isotope in question, m(\text{Atom}), from a standard reference such as the Atomic Mass Evaluation (AME) [32]. Also, retrieve the masses of a hydrogen-1 atom (m(^1\text{H})) and a neutron (m_n) [31].

Step 3: Calculate the Total Constituent Mass Compute the sum of the masses of the individual constituents when they are unbound.

Step 4: Compute the Mass Defect Subtract the measured atomic mass from the total constituent mass.

Step 5: Calculate Total Binding Energy Convert the mass defect to energy using the mass-energy equivalence.

Step 6: Compute Binding Energy per Nucleon

Divide the total binding energy by the mass number, A.

Figure 1: A standardized workflow for the sequential calculation of mass defect and binding energy.

Advanced Theoretical Mass Prediction Models

For the thousands of nuclides beyond the reach of current experimental capabilities, particularly those along the rapid neutron-capture process (r-process) path, theoretical models are essential for mass prediction [32]. Global theoretical approaches fall into two main categories:

Macroscopic-Microscopic Models: These models, such as the Finite-Range Droplet Model (FRDM), combine a macroscopic description of the nucleus as a liquid drop with microscopic shell corrections [32]. While highly accurate for describing known masses, their predictive power for exotic nuclei can be limited.

Microscopic Density Functional Theory (DFT): DFT provides a robust, self-consistent framework for describing nearly all nuclides. The Covariant Density Functional Theory (CDFT), a relativistic extension, automatically incorporates key nuclear features like the spin-orbit interaction [32]. State-of-the-art implementations like the Deformed Relativistic Hartree-Bogoliubov theory in Continuum (DRHBc) simultaneously incorporate nuclear deformation, pairing correlations, and continuum effects, leading to a mass table with remarkable predictive power for neutron-rich superheavy nuclei, achieving a root-mean-square (rms) deviation of 0.642 MeV for 56 masses in the superheavy region [32].

Furthermore, Machine Learning (ML) approaches, such as Kernel Ridge Regression (KRR), are being integrated with traditional theories like the Relativistic Continuum Hartree-Bogoliubov (RCHB) theory to refine mass predictions by learning from the discrepancies between theoretical and experimental values, thereby enhancing accuracy [32].

Data Presentation: Mass Defect Calculations for Common Isotopes

The following tables present calculated data for stable and clinically relevant isotopes, demonstrating the application of the previously outlined protocol.

Table 2: Calculated Mass Defect and Binding Energy for Common Light Isotopes

| Isotope | Measured Atomic Mass (u) | Total Constituent Mass (u) | Mass Defect, Δm (u) | Total Binding Energy, E_b (MeV) | Binding Energy per Nucleon, BEN (MeV/nucleon) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterium (²H) | 2.014101778 [31] | 2.017 | 0.002 | 2.24 [6] | 1.12 |

| Helium-4 (⁴He) | 4.002603 [3] | 4.03296 [4] | 0.0304 | 28.3 | 7.08 |

| Carbon-12 (¹²C) | 12.000000 [30] | 12.102 | 0.102 | 92.2 | 7.68 |

| Oxygen-16 (¹⁶O) | 15.99491462 [31] | 16.131 | 0.136 | 126.7 | 7.92 |

| Iron-56 (⁵⁶Fe) | 55.934937 | 56.463 | 0.528 | 492 | 8.79 |

Table 3: Mass Data for Isotopes Relevant to Medical Applications

| Isotope | Nuclear Composition (Z, N) | Primary Application | Half-Life |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technetium-99m (⁹⁹ᵐTc) | (43, 56) | SPECT Imaging [33] | 6 hours [33] |

| Fluorine-18 (¹⁸F) | (9, 9) | PET Imaging ([¹⁸F]FDG) [33] | 110 minutes |

| Lutetium-177 (¹⁷⁷Lu) | (71, 106) | Targeted Radionuclide Therapy [33] | 6.65 days [33] |

| Gallium-68 (⁶⁸Ga) | (31, 37) | PET Imaging (e.g., PSMA-11) [33] | 68 minutes |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Research and development in nuclear chemistry and its applications rely on specialized materials and instruments.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stable Isotope Targets | Serve as precursors for radionuclide production in accelerators or reactors. | Enriched Mo-100 for cyclotron production of Tc-99m. |

| Targeting Vectors | Biologically active molecules that deliver radionuclides to specific cells. | Peptides (e.g., DOTATATE for somatostatin receptors), Small Molecules (e.g., PSMA-11 for prostate cancer) [33]. |

| Chelators | Organic molecules that form stable, coordinate covalent bonds with metal radionuclides. | DOTA, NOTA for binding diagnostic Ga-68 or therapeutic Lu-177 [33]. |

| Calibration Standards | For precise mass spectrometry measurements of atomic masses. | Perfluorotributylamine (PFTBA) for GC-MS calibration [34]. |

| Reference Mass Data | Critical for calculating theoretical masses and mass defects. | Atomic Mass Evaluation (AME) database [32], Table of Isotopes. |

Implications in Research and Drug Development

The principles of mass defect and nuclear binding energy underpin several advanced technologies, most notably in the development of radiopharmaceuticals for cancer theranostics.

In radiotheranostics, pairs of radioisotopes are used for both diagnosis and therapy. A diagnostic isotope like Gallium-68 (⁶⁸Ga) is used in a PET imaging agent to identify and characterize tumors. Once confirmed, the same targeting molecule (e.g., PSMA-11, DOTATATE) is labeled with a therapeutic isotope like Lutetium-177 (¹⁷⁷Lu) to deliver cytotoxic radiation directly to the cancer cells [33]. The stability of the nucleus and the energy released in its decay—concepts directly linked to its binding energy and mass defect—are paramount to the efficacy and safety of these treatments.

Figure 2: The radiotheranostics cycle in nuclear medicine, linking diagnostic imaging and targeted radionuclide therapy, enabled by the precise nuclear properties of different isotopes.