Optimizing Multi-Object Spectrometer Slit Configurations for Enhanced Accuracy in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing slit configurations in multi-object spectrometers to maximize data accuracy and throughput.

Optimizing Multi-Object Spectrometer Slit Configurations for Enhanced Accuracy in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing slit configurations in multi-object spectrometers to maximize data accuracy and throughput. Covering foundational principles from astronomy and material science, it explores advanced methodological approaches including mathematical programming and heuristic algorithms for slit design. The content details troubleshooting strategies for common issues like signal-to-noise degradation and alignment errors, and presents a rigorous framework for the validation and comparative analysis of spectroscopic methods. By synthesizing techniques from diverse fields, this guide aims to empower scientists to enhance the precision and efficiency of spectroscopic analyses in biomedical and clinical applications.

Fundamental Principles of Multi-Object Spectrometry and Slit Configuration

Core Function and Impact of Slit Configuration on Spectral Accuracy and Throughput

Troubleshooting: Slit Configuration and Spectral Data Quality

Q1: My spectral data shows inconsistent flux readings and poor signal-to-noise ratio. Could slit configuration be a factor?

Yes, improper slit configuration is a common cause of these issues. The slit acts as the entrance aperture to the spectrometer, directly controlling throughput and optical resolution [1].

- Inconsistent Flux/Throughput: This is often caused by slit losses, where the slit is too narrow to capture the entire point spread function (PSF) of the target, or misalignment where the target is not well-centered in the slit [2]. For micro-shutter assemblies (MSAs) like the one on JWST's NIRSpec, the fixed grid nature means sources will not be perfectly centered, inherently leading to greater slit losses compared to ground-based systems with positionable slits [2].

- Unexpected Background Contamination (Light Leakage): In systems like the NIRSpec MSA, even shutters commanded to be closed have finite contrast, allowing small amounts of light to leak through and contaminate the spectra from planned sources [3] [2]. This is particularly problematic when observing faint objects in fields with broad-scale nebular emission.

- Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): If the slit is too small, insufficient light enters the spectrometer, leading to a low signal. Conversely, a wider slit admits more background light, which can increase noise. Selecting a slit width that balances signal collection with the system's inherent resolution is crucial [1].

Q2: I am planning a multi-object spectroscopy (MOS) observation. What are the primary slit-related factors I must consider to ensure accurate target acquisition and data quality?

For successful MOS observations, slit configuration extends beyond individual slit dimensions to the design of the entire mask.

- Astrometric Accuracy: High-quality astrometry is critical. For compact sources, especially those smaller than a single shutter in an MSA, accurate astrometry (to 5-10 mas is strongly recommended) is necessary for both target acquisition and reliable flux calibration [3] [2]. Pre-imaging of the field, for example with JWST's NIRCam, is often required to achieve this [2].

- Slit Geometry and Placement: The goal is to maximize the number of observed targets while minimizing issues.

- Avoiding Failed Shutters/Slits: MSAs contain a population of inoperable shutters (e.g., stuck open or closed). Observation planning software must be used to design configurations that work around these elements [3] [2].

- Minimizing Contamination: Ensure slits are not placed where light from a bright, nearby source could leak into them [2].

- Spectral Resolution and Coverage: The chosen slit width, in conjunction with the disperser, defines the nominal spectral resolution. Furthermore, in MOS modes, the physical location of a slit on the focal plane can affect the complete spectral coverage due to detector gaps, where certain wavelength ranges are lost for some shutters [3].

Q3: When comparing spectrometer performance, how does a multi-object spectrometer with a configurable slit unit differ from a conventional system?

Configurable slit units, like the micro-shutter assembly (MSA) in NIRSpec or movable slits in FORS2, represent a significant advancement in MOS efficiency and flexibility.

The table below summarizes the key operational differences:

| Feature | Configurable Slit Unit (e.g., NIRSpec MSA, FORS2 MOS) | Conventional Fixed Mask Spectrometer |

|---|---|---|

| Mask/Slit Configuration | Electrically commanded micro-shutters or motor-driven slitlets [3] [4] | Physical mask, laser-cut or milled from metal [5] |

| Reconfiguration Time | ~90 seconds for a full MSA sweep [3]; <25 seconds for FORS2 slit pattern [4] | Days to weeks for fabrication and delivery [5] |

| Field of View | e.g., NIRSpec: 3.6' × 3.4' [3] | e.g., OSMOS: 20' diameter [5] |

| Number of Targets/Slits | Up to ~100+ simultaneously with NIRSpec MSA [3] | ~50-100 slits per mask for OSMOS [5]; 19 for FORS2 [4] |

| Astrometric Requirements | High (mas-level) for optimal centering and flux calibration [3] [2] | Dependent on mask fabrication and alignment accuracy |

| Flexibility | High; can rapidly change programs and respond to new information | Low; mask is fixed and cannot be altered once fabricated |

Experimental Protocols for Slit Configuration Optimization

Protocol 1: Methodology for Quantifying Slit-Loss and Flux Calibration Accuracy

This protocol is designed to empirically measure and correct for flux losses introduced by the slit configuration.

- Objective: To determine the flux loss factor for point sources observed with a given multi-object slit mask configuration.

- Materials:

- Procedure:

a. Astrometric Calibration: Use the pre-imaging data to derive precise celestial coordinates (≤ 10 mas accuracy) for all standard stars and science targets in the field [3].

b. Mask Design: Design the MOS mask, placing slits on the standard stars. For MSAs, this involves using a planning tool to configure shutter openings [3] [2].

c. Acquisition & Observation: Execute the observations, including the necessary telescope pointing and target acquisition steps to align the field with the mask [2].

d. Parallel Photometry: Simultaneously or contemporaneously, obtain direct imaging photometry of the same field through a comparable filter.

e. Data Analysis:

* Extract 1D spectra from the standard stars observed through the slits.

* Perform absolute flux calibration on the extracted spectra using the standard star's known spectral energy distribution.

* Compare the flux from the slit spectroscopy with the flux from the direct imaging photometry.

* The ratio

F_photometry / F_spectroscopyprovides the slit-loss correction factor for that specific slit configuration and pointing.

Protocol 2: Systematic Workflow for Designing and Validating an MOS Mask

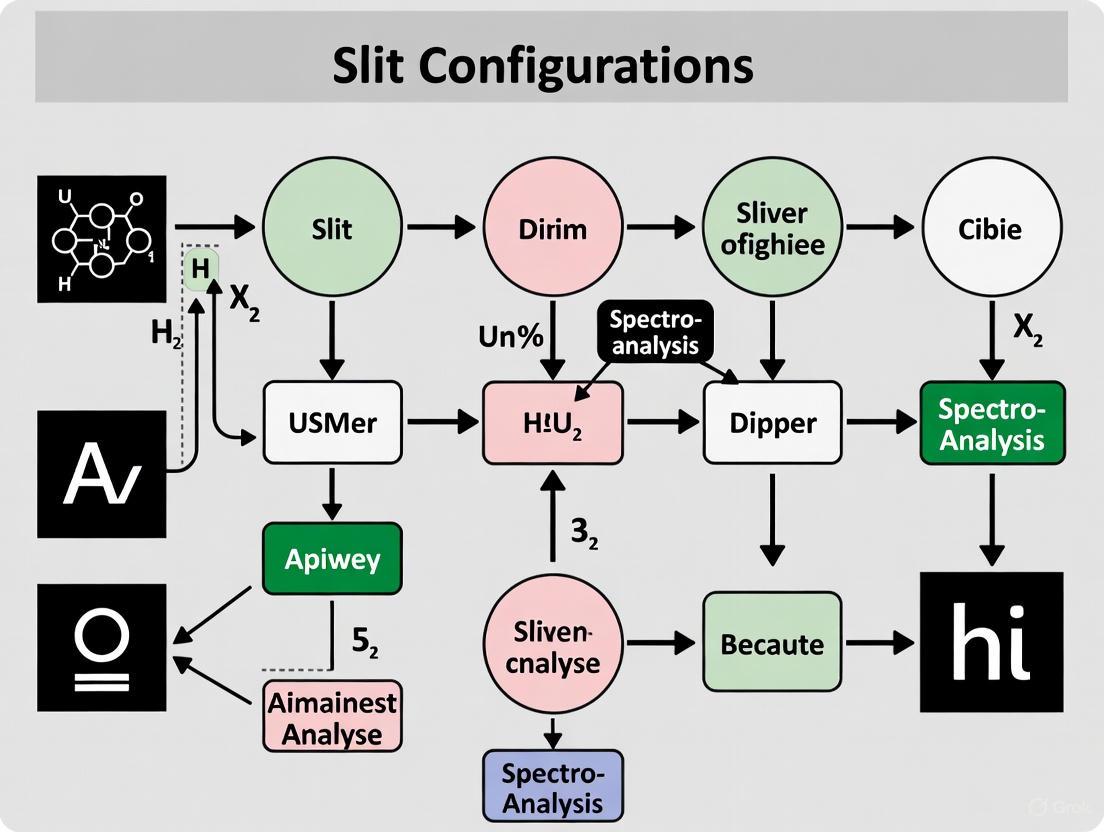

This protocol provides a general methodology for designing a high-efficiency MOS mask, from target selection to final validation. The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for MOS Research

The table below details key components and their functions in multi-object spectroscopy experiments.

| Item | Core Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Micro-Shutter Assembly (MSA) | A grid of hundreds of thousands of tiny, configurable shutters that act as programmable slits to observe dozens to hundreds of targets simultaneously [3]. | Showcase technology on JWST/NIRSpec. Provides unparalleled multiplexing but requires careful planning to work around inoperable shutters and mitigate light leakage [3] [2]. |

| Motorized Movable Slits | Individually driven slitlets that can be positioned anywhere in the focal plane to form a custom slit mask [4]. | Used in instruments like VLT/FORS2. Offers a balance of flexibility and precision without the need for physical mask fabrication [4]. |

| Pre-imaging Data | High-resolution images of the target field used to derive precise astrometry for all science targets and alignment stars [3] [2]. | A critical "reagent" for any MOS experiment. Typically acquired with a high-resolution imager (e.g., HST, JWST/NIRCam) prior to the spectroscopic observation [2]. |

| Mask Planning Tool (MPT) | Software that converts a target list and astrometric catalog into an optimal slit/shutter configuration, avoiding hardware defects and maximizing efficiency [3] [2]. | Essential for operating MSAs and complex mask designs. Uses optimization algorithms to solve the non-trivial problem of placing slits to observe the most targets [3] [6]. |

| Reference Stars (for TA) | Stars of a specific brightness range used for target acquisition to remove absolute astrometric uncertainty before the science exposure [2]. | For NIRSpec MOS, these must be between 19.5 – 25.7 ABmag in the TA filters and distributed across the field [2]. |

Maximizing Target Observation Through Optimal Slit Placement

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Slit Configuration Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Spectral Resolution but Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Slit width too narrow, severely limiting optical throughput. [7] [8] | Increase the slit width to the maximum that still meets the resolution requirement for the application. A wider slit allows more light, reducing exposure time. [7] | |

| Inability to Resolve Close Spectral Features | Slit width too wide, causing images of different wavelengths to overlap on the detector. [7] [8] | Use a narrower slit and/or a grating with higher lines per mm (higher dispersion). Ensure the final spectral image width is less than the separation between wavelengths. [7] [8] | |

| Unstable Results or Frequent Need for Recalibration | Dirty optical windows in front of the fiber optic or direct light pipe. [9] | Clean the spectrometer's optical windows regularly as part of standard maintenance procedures. [9] | |

| Low Throughput Even with an Appropriately Wide Slit | Geometric mismatch between a circular focal spot and a narrow rectangular slit. [7] | Use a ribbon fiber at the entrance, which has a linear geometry that matches the slit shape, to maximize coupling efficiency. [7] | |

| Data Processing Distortions in Diffuse Reflection | Incorrect data processing method. [10] | Convert data to Kubelka-Munk units instead of absorbance for a more accurate spectral representation. [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental trade-off in selecting a slit width?

The core trade-off is between spectral resolution and optical throughput.

- Narrow Slit: Provides higher spectral resolution by restricting the angle of incoming light and creating a sharper image. However, it allows less light to enter, which can lead to a lower signal-to-noise ratio and require longer exposure times. [7] [8]

- Wide Slit: Maximizes throughput by allowing more light into the spectrometer, which is crucial for low-light applications. The downside is lower spectral resolution, as it can cause overlapping of closely spaced spectral lines. [7] [8] The guiding principle is to use the widest slit that still meets the resolution requirements of your experiment. [7]

How does the instrument's optical design affect the slit's function?

The entrance slit acts as the object for the optical system inside the spectrometer. The final image width ((Wi)) on the detector is a product of the slit width ((Ws)) and the system's magnification, plus additional broadening ((Wo)) from optical aberrations. [7]

W_i = M * W_s + W_o

Designs with fewer off-axis components (e.g., on-axis optical trains) have a smaller (Wo), giving the user more precise control over the final resolution through slit selection. [7]

What are the advanced methodologies for optimal slit configuration?

Beyond single-slit tuning, two advanced methods are used:

- Mathematical Programming for Multi-Object Spectrometers (MOS): For instruments with configurable slit units, the problem of placing multiple slits to observe the maximum number of targets in a field of view can be formulated as a non-convex optimization problem. Solutions involve Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and heuristic approaches like iterated local search to find near-optimal configurations. [6]

- Micro-Electro-Mechanical Systems (MEMS): Technologies like Micro-Mirror Devices (MMDs) and Micro-Shutter Arrays (MSAs) act as digitally programmable slit masks. They allow for rapid reconfiguration of hundreds to thousands of "slits," enabling highly efficient multi-object spectroscopy and even Integral Field Unit (IFU)-like observations. [11] [2]

How do I optimize observations for a multi-object spectrometer?

Efficient MOS use involves several key steps:

- Astrometric Accuracy: Precise positions of all targets in the field are required. This often necessitates pre-imaging of the field. [2]

- Mask Design Optimization: Using planning tools to configure slits or micro-shutters to maximize the number of observed targets, accounting for instrumental constraints like stuck shutters. [2]

- Dithering: Moving the telescope slightly between exposures to place spectra on different detector areas helps mitigate detector artifacts and improves background estimation. [2]

The following table summarizes critical components and their functions in spectrometer configuration.

Table: Essential Research Toolkit for Spectrometer Configuration

| Component | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Variable Slit | Allows manual adjustment of the entrance slit width to balance resolution and throughput for a given experiment. [1] |

| Diffraction Grating | Disperses light into its constituent wavelengths; gratings with more lines per mm provide higher spectral resolution but cover a narrower wavelength range. [1] |

| Detector Selection | Different detectors (e.g., CCD, InGaAs) are optimized for specific wavelength ranges (UV/VIS vs. NIR) and sensitivity requirements. Cooled detectors are essential for low-light applications like Raman spectroscopy. [1] |

| Atmospheric Dispersion Corrector (ADC) | Corrects for the wavelength-dependent refraction of light passing through the atmosphere, ensuring all wavelengths from a target are simultaneously centered in the slit. Critical for ground-based observations. [12] |

| Configurable Slit Unit (CSU) / MEMS | Replaces static masks with software-defined, movable bars or micro-mirrors/shutters to rapidly create a custom multi-slit mask, dramatically improving observational efficiency. [11] [2] |

Experimental Protocol: Workflow for Slit Configuration Optimization

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for configuring a spectrometer to achieve optimal performance for a specific application.

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the fundamental optimization problem in multi-object spectrometer slit placement?

The problem involves positioning and rotating a rectangular field of view in the sky to maximize the number of celestial objects observed simultaneously through a series of configurable slits [6]. Each pair of sliding metal bars creates one slit, and the entire configuration of these bars is referred to as a "mask" [6]. The core challenge is a non-convex optimization problem where the goal is to find the optimal translation and rotation of this rectangle to encompass the highest number of target objects from an astronomical catalogue [6].

What are the key mathematical formulations used for this problem?

The approach depends on whether the rotation angle is fixed. For a fixed rotation angle, the problem can be formulated as a Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) model [6]. When the rotation angle is also a variable to be optimized, the formulation becomes a more complex non-convex mathematical program [6]. Heuristic methods, such as an iterated local search approach, are often employed to find near-optimal solutions for the general problem [6].

Troubleshooting Common Optimization Challenges

FAQ: Why does my optimization algorithm fail to find a solution that includes all my high-priority targets?

This is typically due to the geometric constraints of the slit unit and the spatial distribution of your targets. The field of view is divided into contiguous parallel spatial bands, each associated with only one pair of sliding bars [6]. If high-priority targets are clustered in a way that exceeds the slit capacity of a single band or are positioned outside the rotatable field of view, the solver cannot legally include them all. Consider revising your target priority list or adjusting the initial rotation angle constraints.

FAQ: My optimization results seem suboptimal. How can I verify the quality of the solution produced by the solver?

Implement a two-stage verification process. First, validate the solver's output against a simple, known configuration. Second, for complex instances, the iterated local search heuristic described in the literature is designed to find near-optimal masks, balancing computational time with solution quality [6]. If results are consistently poor, check the constraints in your model—specifically, ensure that the constraints preventing slit overlap and enforcing the boundaries of the field of view are correctly implemented.

FAQ: What computational resources are typically required to solve this optimization problem efficiently?

The required resources depend on the problem size (number of candidate objects) and the chosen formulation. The MILP formulation for fixed angles can be solved with standard optimization solvers, but computation time will grow with the number of integer variables [6]. The non-convex formulation for variable angles is more computationally demanding and often requires heuristic approaches like iterated local search to achieve feasible computation times for real-world instances [6].

Experimental Protocols & Implementation

Protocol 1: Defining the Input Catalogue and Parameters

- Input Preparation: Compile a catalogue of celestial objects with their precise right ascension and declination coordinates.

- Parameter Definition: Define the following fixed parameters for your spectrograph and observation run:

- Field of view dimensions (width and height of the rectangular area)

- Number of available parallel spatial bands (slits)

- Minimum and maximum allowable rotation angle for the field of view

- Priority weights for each object (if applicable)

- Model Selection: Choose the appropriate mathematical model (MILP for fixed angle, non-convex for variable angle) based on your experimental needs.

Protocol 2: Executing and Validating the Optimization

- Solver Execution: Run the selected optimization model using an appropriate solver (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi for MILP) or a custom-coded heuristic.

- Solution Validation: The output is an optimal or near-optimal "mask" configuration. This specifies the final translation (position) and rotation of the field of view, and the list of selected objects with their corresponding slit placements [6].

- Output Analysis: Generate a report detailing the selected objects, the final mask configuration, and the percentage of high-priority targets successfully included.

Visualization of the Optimization Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and key decision points in the slit placement optimization process.

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

The table below lists the essential conceptual "components" required to formulate and solve the slit placement optimization problem.

| Item | Function in the Optimization Process |

|---|---|

| Celestial Object Catalogue | Provides the input data: the set of candidate objects with their sky coordinates to be considered for observation [6]. |

| Mathematical Programming Solver | Software (e.g., CPLEX, Gurobi) used to compute the optimal solution for the MILP formulation with a fixed rotation angle [6]. |

| Iterated Local Search Algorithm | A heuristic meta-algorithm used to find high-quality solutions for the more complex non-convex problem where the rotation angle is variable [6]. |

| Spatial Band & Slit Model | A digital representation of the spectrometer's configurable slit unit, which defines the physical constraints of the problem [6]. |

| Cost Function | The objective to be optimized, which is typically defined as the (weighted) count of celestial objects that can be observed simultaneously within the mask configuration [6]. |

The Critical Role of Field of View, Rotation, and Parallel Spatial Band Management

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Suboptimal Observation Mask Configuration

This guide addresses the challenge of designing observation masks that fail to maximize the number of celestial objects observed within the spectrometer's field of view.

- Problem: The configured mask observes fewer objects than theoretically possible from the input catalogue.

- Investigation: Verify if the optimization accounts for both translation and rotation of the field of view. A non-convex mathematical formulation is required for this problem, and using a simplified model that fixes the rotation angle will yield suboptimal results [6].

- Solution: Implement an Iterated Local Search heuristic approach for the general problem where the rotation angle is unfixed. This method iteratively adjusts the pointing and rotation of the spectrograph's field of view to find a near-optimal mask configuration [6].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Inaccurate Quantitative Analysis in Complex Solutions

This guide helps resolve issues where spectral models for quantifying components like serum creatinine show high prediction errors, even when using multi-band spectra.

- Problem: Model predictions are inaccurate despite using multi-position or multi-mode spectral data, potentially due to over-fitting [13].

- Investigation:

- Check the number of wavelengths used in the model. Increasing wavelengths in low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) bands can reduce the overall SNR and counteract noise reduction efforts [13].

- Evaluate if the model uses redundant wavelength information that does not contribute to predicting the target component.

- Solution: Apply a wavelength optimization method. Specifically, use a "one-by-one elimination" technique to remove redundant wavelengths from the joint spectrum. This reduces over-fitting and improves the prediction accuracy and robustness of the model [13].

Guide 3: Troubleshooting Two-Dimensional Spatial Field-of-View Reconstruction

This guide addresses challenges in accurately reconstructing the 2D spatial information from the data cube produced by an image-slicer-based Integral Field Spectrograph (IFS).

- Problem: The reconstructed 2D field-of-view is geometrically distorted or misaligned.

- Investigation: The precise spatial location of each image slicer on the detector's focal plane must be calibrated. Inaccurate positioning points for the slicers will lead to errors in the final reconstructed image [14].

- Solution:

- Obtain the line spread function information and characteristic location coordinates for the image slicers [14].

- Determine the positioning points for each group of image slicers under a specific spectral band using quintic spline interpolation within a double-closed-loop optimization framework [14].

- Align the data from all image slicers to complete the field reconstruction [14].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental challenge in designing masks for a multi-object spectrometer with a configurable slit unit? The core challenge is a complex optimization problem that involves pointing the spectrograph's field of view to the sky, rotating it, and selecting celestial objects to create a mask that maximizes the number of objects observed. This requires solving a non-convex mathematical formulation [6].

Q2: How does the "M plus N" theory relate to improving the accuracy of spectrophotometric determinations? The "M plus N" theory states that the accuracy of quantifying a target component is determined by the uncertainty of "M" factors (like non-target components in the solution) and "N" factors (external interference factors). To achieve high accuracy, strategies must be employed during spectrum acquisition, preprocessing, and modeling to suppress errors from all these factors [13].

Q3: What is the advantage of an Integral Field Spectrograph (IFS) over traditional spectroscopic methods? An IFS can simultaneously acquire spatial and spectral information of a target area, generating a three-dimensional (x, y, λ) data cube. This is far more efficient than traditional long-slit spectrographs that require mechanical scanning to achieve spatial coverage, a process that is inefficient and prone to stitching errors [14].

Q4: In spectral modeling, when might Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression not be sufficient, and what is a potential alternative? PLS regression assumes a linear relationship, which does not always apply to complex samples. In cases of non-linearity, alternative methods like Locally Weighted PLS (LWR-PLS) can provide better performance by addressing non-linearity through localized modeling [15].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Wavelength Optimization for Serum Creatinine Analysis

This table summarizes the results of a study that used a wavelength optimization method to improve the accuracy of serum creatinine determination. The key performance indicators are the Root Mean Square Error of the Prediction set (RMSEP) and the correlation coefficient of the prediction set (Rp). A lower RMSEP and an Rp closer to 1 indicate a better model [13].

| Model Description | Spectral Range Used | RMSEP (μmol/L) | Rp | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Spectrum Model | 225-900 nm | 30.92 | 0.9911 | Baseline model with all wavelengths |

| Optimized Wavelength Model | Selectively optimized | 24.12 | 0.9948 | 39.8% reduction in RMSEP after optimization |

Protocol: Field-of-View Reconstruction for an Integral Field Spectrograph

This protocol details the method for reconstructing the two-dimensional spatial field-of-view from the data acquired by an image-slicer-based IFS [14].

- System Setup: Utilize an on-board calibration platform with a light source (e.g., an integrating sphere equipped with Hg-Ar and halogen lamps) to simulate the in-orbit calibration environment.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire the positional distribution of all image slicers (e.g., 32 slicers) within the detector for a specific spectral band.

- Slicer Positioning: For each group of image slicers, determine their precise positioning points on the detector using quintic spline interpolation.

- Optimization Framework: Employ a double-closed-loop optimization framework to establish connection points for the responses of different image slicers.

- Signal Fitting: Improve data accuracy and reliability by fitting the signal intensity of individual pixel points.

- Data Alignment and Reconstruction: Align the data from all image slicers to complete the 2D spatial field-of-view reconstruction for the characteristic wavelength band.

Diagram: Field-of-View Reconstruction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Spectroscopic Experiments

This table lists key items used in the experiments cited in this guide, along with their specific functions.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Hg-Ar Lamp | Provides characteristic spectral lines for precise wavelength calibration of a spectrograph [14]. |

| Halogen Lamp | Used as a stable, continuous light source in calibration platforms, often in conjunction with an integrating sphere [14]. |

| Serum Samples | Complex biological solutions used for developing and validating quantitative spectral models for components like creatinine [13]. |

| Image Slicer IFU | An integral field unit that segments a telescope's 2D field-of-view into multiple slices, rearranging them at the spectrograph's slit for simultaneous spatial and spectral data acquisition [14]. |

| Linear Variable Filter (LVF) | An optical filter whose passband wavelength varies linearly along its length. Used in compact spectrometer designs for spectral analysis across a wide range [16]. |

Advanced Methodologies for Optimal Slit Design and System Configuration

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

This guide addresses common technical challenges researchers face when implementing Mixed Integer Linear Programming (MILP) for fixed-angle slit configuration in multi-object spectrometers.

Q1: My MILP model solves too slowly. What are the primary strategies to improve performance?

A: Slow solve times are often due to a weak LP relaxation. Key strategies include:

- Tighten Formulations: Use the smallest possible "Big M" values for disjunctive constraints and apply problem-specific presolve techniques to strengthen your formulation [17] [18].

- Leverage Solver Capabilities: Enable features like cutting planes (e.g., Gomory, clique, cover cuts) to remove fractional solutions and heuristics (e.g., RINS, diving) to find good feasible solutions early [19] [18].

- Reformulate: A Dantzig-Wolfe (columnwise) reformulation can provide a tighter model, though it may require column generation [17].

Q2: How can I handle the large number of binary variables representing individual shutter openings?

A: This is a classic challenge in mask design [6].

- Exploit Symmetry: Identify and break symmetries in the problem to reduce the solution space.

- Aggregate Constraints: Where possible, use higher-level constraints that govern groups of shutters rather than each one individually.

- Effective Presolve: A high-quality MILP solver will automatically apply presolve to reduce the number of variables and constraints by fixing bounds and removing redundancies [19] [18].

Q3: What does it mean when the solver reports a "gap"?

A: The gap is the difference between the best integer feasible solution found (the incumbent, providing an upper bound) and the best possible solution (the lower bound from the LP relaxations) [18]. A non-zero gap indicates the solution is suboptimal. The search continues until the gap is zero (proving optimality) or falls below a specified tolerance.

Q4: My model is infeasible. How can I diagnose the cause?

A: Infeasibility often stems from overly restrictive constraints.

- Analyze the Core: Use your solver's irreducible inconsistent subsystem (IIS) finder to identify a small set of conflicting constraints.

- Check "Big M" Values: Ensure your "Big M" values are not too small, which could incorrectly cut off feasible solutions [17].

- Review Logic: Verify the logic of your integer constraints, especially those modeling the non-overlap and alignment of slits [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Table 1: Key MILP Algorithmic Components and Their Experimental Setup

| Algorithm Component | Purpose in Mask Configuration | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| LP-Based Branch-and-Bound [18] | Core algorithm for systematically searching for the optimal integer solution. | This is the foundational algorithm used by modern solvers (e.g., Gurobi, intlinprog). |

| Mixed-Integer Preprocessing [19] | To tighten the LP relaxation and reduce problem size before the main search. | Enable solver presolve. Options in intlinprog (IntegerPreprocess) control the level of analysis. |

| Cut Generation [19] [18] | To add valid inequalities that cut off fractional solutions, improving the lower bound. | Set CutGeneration to 'intermediate' or 'advanced' to activate cuts like Gomory and clique. |

| Feasibility Heuristics [19] | To find high-quality integer-feasible solutions early in the search, improving the upper bound. | Set Heuristics to 'intermediate' or 'advanced' to use methods like RINS and rounding. |

Protocol: Implementing a MILP Workflow for Fixed-Angle Mask Design

Problem Formulation:

- Objective: Define the goal, typically to maximize the number of high-priority astronomical objects observed [6].

- Decision Variables: Define binary variables for shutter open/close states and continuous variables for positions.

- Constraints: Formulate linear constraints for:

Solver Configuration:

- Algorithm Selection: Use an LP-based branch-and-bound algorithm [18].

- Parameter Tuning: Based on Table 1, enable cut generation and heuristics.

- Tolerance Setting: Set optimality gaps (e.g., 0.1% for near-optimal results).

Execution and Monitoring:

- Run the solver and monitor the upper bound, lower bound, and gap.

- Use solver callbacks to save intermediate feasible solutions.

Validation:

- Verify the physical feasibility of the solution by mapping the integer solution back to a mask configuration.

- Check for constraint violations against the original problem specifications.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for MILP-based Mask Optimization

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

MILP Solver (e.g., Gurobi, MATLAB intlinprog) |

The core computational engine that executes the branch-and-bound algorithm to find optimal solutions [19] [18]. |

| High-Precision Astrometry Catalog | Provides the precise celestial coordinates of target objects, which is crucial for accurate slit placement [3]. |

| Micro-Shutter Assembly (MSA) Planner Software | Specialized software (e.g., for JWST's NIRSpec) that translates solver output into executable instrument commands and accounts for hardware constraints [3]. |

| Performance Profiling Tools | Used to diagnose computational bottlenecks within the MILP model, highlighting areas for reformulation. |

Visualizing the MILP Process and Workflow

The following diagrams illustrate the core MILP solution algorithm and its application to the spectrometer mask design workflow.

MILP Branch and Bound Algorithm

Spectrometer Mask Optimization Workflow

Heuristic and Iterated Local Search Algorithms for Complex, Non-Convex Problems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Algorithm Selection and Theory

Q1: What are the core advantages of using Iterated Local Search (ILS) over a simple local search for configuring spectrometer slits?

Simple local search methods can quickly get trapped in local minima—configurations where no small adjustment improves the target selection but which are far from the best possible setup. ILS is specifically designed to overcome this by systematically escaping these local traps [20]. Its core operation involves a cycle of local search (intensively improving a configuration) and perturbation (intelligently modifying the configuration to jump to a new region of the search space) [21]. This makes it ideal for the complex, non-convex optimization landscape of positioning hundreds of slits to maximize the number of observed targets, where the quality of the final configuration is critical for observational efficiency [6].

Q2: Why are heuristic methods necessary for complex problems like mask design?

Many practical optimization problems in science and engineering, including the design of optimal masks for multi-object spectrometers, are non-convex [22]. This means their solution landscape is riddled with multiple local minima and saddle points, making it theoretically hard (often NP-hard) to find the single best solution in a reasonable time [23]. Heuristic methods, including ILS, forgo the guarantee of finding a perfect global optimum in favor of finding "good-enough," high-quality solutions efficiently [24]. They provide a practical and robust approach to managing the high demand for telescope time by delivering excellent slit configurations much faster than exact methods could for large problem instances [6].

Q3: What is the role of the perturbation operator in ILS, and how do I choose its strength?

The perturbation operator is the primary mechanism for diversification in ILS, helping the algorithm escape the attraction basin of the current local optimum [20]. Its strength is crucial: a perturbation that is too weak will cause the subsequent local search to fall back into the same local minimum, leading to stagnation. Conversely, a perturbation that is too strong makes the algorithm behave like a random restart, wasting the computational effort spent on the previous local search [21]. The strength can be set based on benchmark tests or, more effectively, through adaptive mechanisms that adjust it during the search based on history, for instance, by using a tabu list to guide the perturbation [21].

Practical Implementation and Troubleshooting

Q4: My ILS algorithm converges too quickly to a suboptimal slit configuration. What parameters should I adjust?

Quick convergence to a poor solution typically indicates a lack of exploration. You can adjust the following parameters to promote diversification:

- Perturbation Strength: Increase the intensity of the perturbation. For a slit mask problem, this could mean randomly swapping or shifting a larger number of slits in the current best solution [21].

- Acceptance Criterion: Make the criterion for accepting a new solution less greedy. Instead of only accepting improvements, use a criterion like Acceptance with Probability or a threshold to occasionally allow slightly worse solutions, enabling the search to cross unfavorable regions to find better optima [21].

- Number of Iterations: Simply run the algorithm for more iterations to allow for more extensive exploration.

Q5: During optimization, the algorithm seems to stall, making no progress for many iterations. What could be the cause?

Stalling is often a sign that the algorithm is trapped in a large, flat region of the search space, such as a plateau or a saddle point [25]. To address this:

- Introduce Randomness: For gradient-based methods, adding noise to the updates can help escape flat regions [23]. In ILS, ensure your perturbation operator is stochastic enough.

- Use Memory Structures: Incorporate a short-term memory, like a tabu list, to forbid the algorithm from revisiting recently explored configurations, thus forcing it into new areas [21] [25].

- Hybridize: Combine your local search with a metaheuristic like simulated annealing for its move acceptance policy, which can help traverse flat areas [25].

Q6: How can I balance the trade-off between exploration and exploitation in my ILS setup?

Balancing exploration (searching new areas) and exploitation (refining good solutions) is key to ILS's performance [21]. This balance is managed through the interaction of its core components:

- Local Search is responsible for exploitation, deeply refining a solution.

- Perturbation is responsible for exploration, pushing the search into new basins of attraction.

- Acceptance Criterion decides the balance between the two by determining whether to continue from the new solution or the old one [21].

An effective strategy is to use an adaptive approach where the strength of the perturbation is adjusted based on the search history—increasing it if the algorithm hasn't improved for a while, and decreasing it when it finds a new promising region [21].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Persistent Entrapment in Local Minima

Symptoms: The solution quality does not improve significantly across multiple runs, and the algorithm consistently returns similar, suboptimal slit configurations.

| Investigation Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| Verify Local Search | Ensure your local search algorithm (e.g., Hill Climbing, 2-opt) is working correctly and can find a local optimum from a given starting point [21]. |

| Analyze Perturbation | Check if the perturbation is sufficiently strong. A good test is to run the perturbation on a local optimum and then apply local search; if it returns to the same optimum, the perturbation is too weak [20]. |

| Adjust Parameters | Systematically increase the perturbation strength (e.g., number of slits modified). Consider implementing an adaptive perturbation strategy that reacts to search history [21]. |

Problem 2: Unacceptably Long Computation Time

Symptoms: A single run of the algorithm takes too long to complete, hindering research progress.

| Investigation Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| Profile the Code | Identify the computational bottleneck. Is it the objective function evaluation (e.g., calculating the number of targets observed) or the neighborhood search? |

| Optimize Objective Function | The evaluation of a slit mask configuration can be computationally expensive [6]. Cache results where possible or use faster, approximate evaluations during initial search phases. |

| Simplify Local Search | Use a faster, though less thorough, local search method. Consider first-improvement instead of best-improvement strategies, or reduce the neighborhood size evaluated at each step [25]. |

Problem 3: High Variability in Solution Quality

Symptoms: Different runs of the algorithm with the same input data yield results with widely differing quality.

| Investigation Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| Check Initialization | A high variance often stems from the quality of the initial, often random, solution. Implement a smart initialization heuristic (e.g., a greedy algorithm) to start from a reasonably good configuration [21] [24]. |

| Review Acceptance Criterion | If using a stochastic acceptance criterion (e.g., based on probability), the variability is expected. To reduce it, use a more deterministic criterion, or run the algorithm longer to allow it to consistently find good regions. |

| Increase Iterations | Run the algorithm for a larger number of iterations. High variability between runs often decreases as the algorithm is given more time to explore the search space thoroughly. |

Experimental Protocols for Mask Configuration

Protocol 1: Implementing a Basic Iterated Local Search

This protocol outlines the steps to implement an ILS algorithm for generating a near-optimal slit mask configuration.

1. Problem Initialization:

- Input: A list of celestial target coordinates within the field of view and the number of available slits.

- Generate Initial Solution: Create a random, feasible slit mask configuration,

X_current. A configuration defines the position and orientation of each slit [6].

2. Local Search Phase:

- Apply a local search algorithm (e.g., Hill Climbing) to

X_currentuntil a local optimum,X_base, is found [21] [24]. - For slit configuration, a neighborhood could be defined by all configurations reachable by moving a single slit a small amount or swapping the targets assigned to two slits.

3. Perturbation Phase:

- Apply a perturbation to

X_baseto create a new starting solution,X_perturbed. The perturbation should be strong enough to escape the current basin of attraction. For example, randomly shift the position of 5-10% of the slits in the mask [20] [21].

4. Local Search (on Perturbed Solution):

- Apply the local search algorithm from

X_perturbedto find a new local optimum,X_candidate.

5. Acceptance Criterion:

- Decide whether to accept

X_candidateas the new current solution. The simplest criterion is to only accept improvements:If cost(X_candidate) > cost(X_current), then X_current = X_candidate[21]. - Alternative criteria, like simulated annealing-based acceptance, can sometimes yield better performance.

6. Termination and Repeat:

- Repeat steps 3-5 until a stopping condition is met (e.g., a maximum number of iterations, or no improvement for a given number of cycles).

- The best solution found,

X_best, is the final output slit mask.

The following workflow visualizes this iterative process:

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Heuristic Performance

This protocol describes a method to compare different heuristic algorithms for the slit mask optimization problem.

1. Dataset Preparation:

- Prepare multiple benchmark instances of the slit mask problem with varying difficulty (e.g., different numbers of targets and slits, different target densities) [6].

2. Algorithm Configuration:

- Select the algorithms to compare (e.g., Basic Hill Climbing, ILS, Tabu Search).

- For each algorithm, set its parameters based on preliminary tests or literature values. For ILS, this includes perturbation strength and acceptance criterion.

3. Experimental Run:

- Run each algorithm on each problem instance multiple times (to account for stochasticity) with a fixed computational budget (e.g., a fixed time limit or number of objective function evaluations).

4. Data Collection and Analysis:

- For each run, record the final solution quality (e.g., number of targets captured) and the computation time.

- Use the collected quantitative data to populate a comparison table. The following table summarizes key metrics for evaluation:

| Algorithm | Avg. Targets Captured | Best Captured | Avg. Time to Solution (s) | Consistency (Std. Dev.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hill Climbing | 45 | 47 | 12.5 | 1.2 |

| Iterated Local Search | 52 | 55 | 45.8 | 0.8 |

| Tabu Search | 51 | 54 | 61.3 | 0.5 |

| Genetic Algorithm | 49 | 53 | 120.4 | 1.5 |

- Perform statistical tests (e.g., a Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to determine if the performance differences between the top-performing algorithms are statistically significant.

This table details essential computational and methodological "reagents" for conducting research in slit mask optimization.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Iterated Local Search (ILS) Framework | A metaheuristic skeleton that combines local search with perturbation to find high-quality slit configurations by effectively balancing exploration and exploitation [21]. |

| Perturbation Operator | A function that modifies a current slit mask solution to escape local optima. Its design is critical; it must be strong enough to jump to a new search region but not destroy good solution components [20]. |

| Local Search Algorithm | A subsidiary procedure (e.g., Hill Climbing, Variable Neighborhood Descent) used within ILS to find a local optimum from a given starting point through iterative, greedy improvements [25]. |

| Acceptance Criterion | The rule that determines whether to continue the search from a newly found local optimum or the previous one. This helps control the trade-off between intensification and diversification [21]. |

| Astronomical Target Catalog | The input data containing the celestial coordinates and magnitudes of all potential objects in the field of view, forming the basis for the optimization objective [6]. |

| Mixed-Integer Programming (MIP) Solver | An exact optimization tool (e.g., Gurobi, CPLEX) that can be used to find provably optimal solutions for smaller problem instances or to provide a baseline for evaluating heuristics [6]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical factors that directly impact spectrometer sensitivity? Spectrometer sensitivity is primarily governed by a balance between throughput (the amount of light reaching the detector) and resolution (the ability to distinguish close wavelengths). In conventional systems, achieving higher resolution typically comes at the expense of light throughput, which can lower the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and require longer integration times [26]. Optimizing slit configurations in a Multi-Object Spectrometer (MOS) is a direct method to manage this trade-off, as it controls which celestial objects' light is admitted into the spectrograph [11].

2. During low-light observations, our results show high noise. Is this a sensitivity or a configuration issue? This is likely both. A low signal intensity exacerbates the inherent limitation of conventional spectrometers, where high-resolution settings reduce luminosity [26]. First, verify that your slit configuration is optimized to maximize the collection of light from your target sources. Second, ensure there are no physical obstructions; check that the fiber optic and light pipe windows are clean, as dirty windows can cause intensity drift and poor analysis readings [9].

3. What does "injection efficiency" mean in the context of a MOS, and how is it optimized? Injection efficiency refers to the effective coupling of light from the telescope's focal plane into the spectrograph. In a MOS, this is managed by the programmable slit mask. Optimizing it involves designing a mask—a configuration of open slits or tilted micromirrors—that selects the maximum number of target objects while minimizing dead space and background sky contamination [6]. Advanced metasurface spectrometers can improve this by using a "bandstop" strategy that allows more photons to reach the detector without sacrificing resolution [26].

4. We observe inconsistent elemental readings, especially for Carbon and Sulfur. What could be the cause? Inconsistent readings for low-wavelength elements like Carbon, Phosphorus, and Sulfur are a classic symptom of a failing vacuum pump in the optic chamber [9]. These elements emit light in the ultraviolet spectrum, which is absorbed by air. If the pump is not maintaining a proper vacuum, the atmosphere enters the chamber, causing a loss of intensity and incorrect values. Monitor the pump for unusual noises, heat, or oil leaks [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Drifting Analysis or Inconsistent Results

- Symptoms: Frequent need for recalibration; significant variation in results for the same sample; low readings for carbon, phosphorus, and sulfur [9].

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Dirty Windows | Visually inspect the windows in front of the fiber optic and the direct light pipe [9]. | Clean the windows with appropriate materials as part of a regular maintenance schedule [9]. |

| Failing Vacuum Pump | Check for constant low readings of C, P, S; listen for gurgling noises; feel if the pump is hot; look for oil leaks [9]. | Replace or service the vacuum pump immediately [9]. |

| Contaminated Samples | Inspect sample preparation. A milky-white burn can indicate contamination [9]. | Re-grind samples on a new pad. Do not quench samples in water/oil or touch them with bare hands [9]. |

| Aging Light Source | Check for inconsistent readings or drift over time [27]. | Allow the instrument sufficient warm-up time. If problems persist, replace the lamp [27]. |

Issue 2: Low Light Intensity or Signal Error

- Symptoms: System reports low signal; high noise in spectra; requires excessively long integration times.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Check | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Suboptimal Slit Mask | Evaluate if the current mask design blocks too much light from targets. | Use mathematical programming to design a near-optimal mask that maximizes target objects observed [6]. Consider MEMS-based masks for dynamic optimization [11]. |

| Misaligned Optics | Check if the light collected is not intense enough for accurate results [9]. | Verify and realign the lens on probes to ensure they focus correctly on the light source [9]. |

| Obstructed Light Path | Inspect the sample cuvette for scratches or residue. Look for debris in the light path [27]. | Ensure the cuvette is clean, aligned, and free of defects. Clean the optics as needed [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Evaluating Slit Configuration Efficiency for Multi-Object Observation

This protocol is designed to empirically determine the optimal slit mask configuration to maximize the number of observed targets in a given field of view, a core aspect of throughput optimization [6].

- Objective: To quantify the efficiency of different slit mask configurations in a simulated telescope field.

- Materials:

- Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Load the catalog of target objects into the optimization software. Define the constraints of your spectrograph, such as the number of available slits and the allowable rotation angles of the field of view [6].

- Model Execution:

- Validation: Compare the number of targets selected by the optimized mask against a baseline, non-optimized configuration.

- Expected Output: A quantifiable increase in the number of targets observed per configuration, directly contributing to higher overall system throughput and efficiency.

Protocol 2: Characterizing a Novel qBIC Metasurface Spectrometer

This protocol outlines the steps to fabricate and test a high-sensitivity metasurface spectrometer that overcomes the traditional resolution-sensitivity trade-off [26].

- Objective: To fabricate a dielectric metasurface encoder and use it to reconstruct an unknown input spectrum.

- Materials:

- Quartz substrate.

- Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) film.

- Electron-beam lithography system.

- CMOS image sensor array.

- Computational reconstruction algorithm [26].

- Methodology:

- Fabrication: Deposit a 92 nm thick TiO₂ film on quartz. Use lithography to etch an array of cylindrical nanoholes in a diatomic unit cell (two holes with slightly different radii) arranged in a square lattice. The pitch (P) is varied linearly across the array to tune the central wavelength of the bandstop feature [26].

- Integration: Mount the fabricated metasurface array directly onto the CMOS sensor.

- Data Acquisition & Reconstruction: Expose the device to a light source. Record the intensity

Iifrom each of themdetectors. Reconstruct the input spectrumS(λ)by solving the system of linear equations:∫ S(λ) * Ti(λ) dλ = Ii(for i=1 to m), whereTi(λ)is the known transmission profile of each metasurface filter, using a computational algorithm [26].

- Expected Output: Demonstration of a spectrometer platform where light throughput (sensitivity) is enhanced as the spectral resolution is increased, validated by accurate spectral reconstruction under low-irradiance conditions [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| Micro-Mirror Device (MMD) | A MEMS-based array of tiny, individually addressable mirrors that functions as a dynamic slit mask for a MOS, allowing rapid reconfiguration and efficient light injection from multiple targets [11]. |

| Dielectric Metasurface (qBIC encoder) | A planar, CMOS-compatible optical component featuring nanoscale structures that support quasi-Bound States in the Continuum. It acts as a highly efficient bandstop filter for novel spectrometer designs, breaking the resolution-sensitivity trade-off [26]. |

| Reconfigurable Slit Unit | A system of sliding metal bars that can be positioned to create adjustable slits in the focal plane, enabling simultaneous spectroscopy of multiple fixed objects [6]. |

| Mathematical Programming Solver | Software used to solve the non-convex optimization problem of placing and rotating slit masks to maximize the number of observable celestial objects in a single exposure [6]. |

| Computational Reconstruction Algorithm | An algorithm designed to solve the inverse problem in computational spectroscopy, converting the encoded light intensities from a detector array into a accurate reconstructed spectrum [26]. |

System Optimization Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical relationships and workflows for optimizing spectrometer system sensitivity.

Sensitivity Trade-off & Solution

MOS Mask Optimization Logic

qBIC Spectrometer Operation

Dual-Configuration Architectures for Versatile Multi-Wavelength Coverage

FAQs: Operational Principles and Configuration

Q1: What is a dual-configuration spectrograph and what are its primary advantages? A dual-configuration spectrograph is an optical instrument designed to operate in two distinct spectroscopic modes using shared or reconfigurable hardware. Its key advantage is operational versatility, allowing researchers to switch between modes—such as different spectral resolutions or wavelength ranges—without needing multiple instruments. This architecture maximizes observational efficiency and scientific yield by enabling interchangeable settings or simultaneous multi-wavelength coverage, all while sharing costly components like detectors and cameras to reduce overall instrument cost and complexity [28].

Q2: What are the common symptoms of a fractured crystal in a scintillation detector and how is it resolved? A fractured crystal typically manifests as a "double peak" in the spectrum. The corrective action is to return the detector to the manufacturer or a specialized service center for evaluation and crystal replacement. Users should handle detectors carefully to avoid significant mechanical impacts, vibration, or rapid temperature changes that can cause such damage [29].

Q3: My spectra show inconsistent readings or baseline drift. What steps should I take? Begin by checking the instrument's light source, as an aging lamp can cause fluctuations and may need replacement. Allow the instrument sufficient warm-up time to stabilize, and perform a regular calibration using certified reference standards. Also, inspect sample cuvettes for scratches or residue and ensure they are correctly aligned in the light path [30].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Instrument Issues

| FAULT | POSSIBLE CAUSES | CORRECTIVE ACTION |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Energy Resolution [29] | Damaged detector, poor optical coupling, hydrated crystal, poor electrical ground, defective PMT, or light leak. | Inspect for physical damage, re-interface optical couplings, ensure proper grounding, replace PMT, check for/repair light leaks, or return for professional service. |

| No Signal [29] | PMT failure, faulty cables, or other system component failure. | Check all cables and connections. Return detector for evaluation and repair if a failed PMT is suspected. |

| Count Rate Too Low/High [29] | Excessive dead time, incorrect LLD setting, source strength issues, or excessive background radiation. | Verify source strength and LLD setting. Shield detector from background radiation or relocate it. |

| Low Light Intensity/Signal Error [30] | Dirty or misaligned cuvette, debris in the light path, or dirty optics. | Inspect and clean the cuvette, ensure proper alignment, and inspect/clean the optics. |

| Unexpected Baseline Shifts [30] | Residual sample contamination or need for recalibration. | Perform a full baseline correction and recalibration. Verify that the cuvette or flow cell is thoroughly cleaned. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Investigations

Protocol 1: Optimizing Slit Width for Spectral Resolution and Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)

Objective: To empirically determine the optimal entrance slit width that balances spectral resolution and signal-to-noise ratio for a given sample.

Background: The entrance slit defines the range of incident angles entering the spectrometer. A narrower slit provides higher spectral resolution (less spectral broadening) but reduces light throughput, leading to a lower SNR. A wider slit increases throughput but sacrifices resolution, potentially obscuring fine spectral features [31].

Methodology:

- Setup: Prepare a stable, standard sample with known, sharp emission or absorption peaks.

- Data Acquisition: Acquire spectra of the sample using a range of entrance slit widths (e.g., 20 µm, 50 µm, 100 µm, 200 µm). Keep all other parameters (integration time, detector gain, grating) constant.

- Analysis:

- For each spectrum, measure the Full Width at Half Maximum (FWHM) of a specific, isolated peak to quantify instrumental broadening.

- Measure the Signal-to-Noise Ratio in a flat, continuum region of the spectrum near the peak.

- Optimization: Plot FWHM and SNR against slit width. The optimal slit width is the point where acceptable resolution is achieved without a severe degradation in SNR. If SNR is too low at the desired resolution, consider increasing the integration time [31].

Protocol 2: Characterizing a Dual-Configuration Spectrograph's Performance

Objective: To validate the spectral resolving power and throughput in both operational modes of a dual-configuration spectrograph.

Background: Instruments like the compact spectrograph proposed for the Habitable Worlds Observatory use a mechanism to switch dispersive elements, enabling both low (R ~140) and high (R ~1000) resolution modes for different scientific goals, such as characterizing exo-Earth atmospheres [28] [32].

Methodology:

- Mode Selection: Configure the spectrograph for its high-resolution mode (e.g., using a grism) and then its low-resolution mode (e.g., using a prism).

- Resolution Measurement: Use a spectral calibration source (e.g., a mercury-argon lamp) with known, narrow emission lines. For each mode, capture a spectrum and measure the FWHM of several isolated lines across the wavelength range.

- Calculating Resolving Power: Calculate the resolving power (R = λ/Δλ) for each line, where λ is the line's central wavelength and Δλ is its FWHM. Report the average R for each configuration [28].

- Throughput Verification: Using a stable, broadband light source, measure the signal intensity at key wavelengths in both configurations to confirm expected performance.

Performance Data and Specifications

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of various dual-configuration and high-resolution spectrograph architectures, illustrating the trade-offs in their design.

Table 1: Performance Specifications of Advanced Spectrograph Architectures

| Instrument / Concept | Configuration or Mode | Spectral Resolving Power (R) | Key Application / Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| HWO Compact Spectrograph [28] [32] | Prismatic Mode | ~140 | Optimized for O₂ A-band (760 nm) in exo-Earth atmospheres. |

| Grismatic Mode | ~1,000 | Enables detailed atmospheric characterization via cross-correlation. | |

| IRIS/TMT [28] | Fine-scale IFS | ~4,000 | High-resolution near-IR studies of galaxy kinematics and stellar populations. |

| Multi-shot Type 2 Spectrograph [28] | Multiple Channels | 5,000 – 10,000 (simultaneous) | Achieves multi-resolution data simultaneously without mechanical switching. |

| HRMOS Project (VLT) [33] | Single, High-Resolution | 80,000 | Multi-object (40-60 targets) capability for radial velocity precision (~10 m/s). |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | Essential for regular wavelength and photometric calibration to ensure measurement accuracy and traceability [30]. |

| High-Grade Optical Coupling Grease | Used in demountable detectors to ensure efficient light transmission between components like the PMT and optical window, preventing voids that degrade resolution [29]. |

| Stable Spectral Calibration Source (e.g., Hg-Ar Lamp) | Provides known emission lines for verifying the spectral resolution and wavelength accuracy of the spectrograph in different configurations. |

| Dichroic Beamsplitter | A key component in dual-channel architectures that splits incoming light into different wavelength arms (e.g., blue/red) for parallel processing [28]. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Dual-Configuration Spectrograph Workflow

Slit Width Optimization Protocol

Troubleshooting Common Pitfalls and Strategies for Performance Optimization

Addressing Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) Degradation from Sky Background and System Noise

FAQs

1. What are the most common sources of noise in spectroscopic measurements? Several types of noise can degrade your signal, originating from the instrument itself, the detector, and the external environment. Key sources include:

- Background Noise: Unwanted radiation from the external environment, such as the zodiacal light, Milky Way, or stray light from out-of-field sky [34].

- Sky Noise: Fluctuations in the atmospheric emissivity and path length on timescales of about one second, a significant systematic error for ground-based observations [35].

- Detector Noise: This includes several components:

- Readout Noise: Noise generated when the signal is read from the detector to the data acquisition system, independent of signal strength [36] [37].

- Dark Noise: Signal originating from the thermal excitation of electrons within the detector, even without illumination [36] [37].

- Shot Noise: A fundamental noise related to the particle nature of light, proportional to the square root of the signal intensity [37].

- Fixed Pattern Noise (FPN): Consistent brightness or color deviations at fixed positions, often caused by unevenness between sensor pixels [36].

2. How does the spectrometer slit width affect SNR and resolution? The entrance slit is a critical component that directly governs the trade-off between throughput (and thus SNR) and spectral resolution [7] [38].

- Wide Slit: Increases the amount of light (optical throughput) entering the spectrometer, which can boost the signal and reduce acquisition time. However, it degrades the spectral resolution by allowing a wider range of angles to enter and by creating a broader image on the detector [7].

- Narrow Slit: Enhances spectral resolution by restricting the angle of entering light, leading to sharper images. The primary drawback is a significant reduction in optical throughput, which can lower the SNR, especially for weak signals [7] [38]. The optimal slit width is application-specific, balancing the need for fine resolution against the requirement for a detectable signal [7].

3. What strategies can be used to subtract sky background in NIRSpec-like observations? For instruments like NIRSpec, two primary background subtraction strategies are recommended, depending on the nature of your source [34]:

- Pixel-to-Pixel Subtraction (Nodding): This method involves moving the telescope to subtract the background at the count rate level.

- In-scene nodding: For point-like or compact sources, nodding within the scene maximizes on-source exposure time. Recommended dither patterns include 2, 3, or 5 points for fixed slit spectroscopy, and 2 or 4 points for integral field spectroscopy [34].

- Off-scene nodding: For extended sources that fill the aperture, observing a dedicated "blank sky" position is recommended [34].

- Master Background Subtraction: This method uses an independent flux-calibrated background spectrum. For Multi-Object Spectroscopy (MOS), this can be achieved by designing the microshutter array (MSA) configuration to include dedicated "blank sky" shutters. The spectra from these shutters are combined and subtracted from the target spectrum during data processing [34].

4. How can I calculate the SNR for my Raman spectroscopy data, and why does the method matter? Different methods for calculating Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) can yield different results for the same data, directly impacting the reported Limit of Detection (LOD). The international standard (IUPAC) defines SNR as the signal magnitude (S) divided by its standard deviation (σS) [39].

- Single-Pixel Method: Uses only the intensity of the center pixel of a Raman band. This method may report a lower SNR [39].

- Multi-Pixel Methods: Use information from multiple pixels across the Raman band, such as calculating the band area or fitting a function to the band. Research shows these methods can report a ~1.2 to over 2-fold larger SNR for the same feature compared to single-pixel methods, thereby improving the LOD [39]. Choosing a multi-pixel method can provide a statistical advantage in confirming the presence of weak spectral features that might be below the detection limit with single-pixel calculations [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low SNR Due to High Background Noise

Symptoms:

- Unstable baseline in the spectrum.

- Inability to distinguish weak spectral features from the background.

- Failed background subtraction in long-exposure observations.

Solutions:

- Implement Robust Background Subtraction: Actively employ nodding strategies or master background subtraction as described in the FAQs. For NIRSpec observations, the choice of strategy (e.g., 2-point vs. 4-point nod) impacts the final SNR, with scaling factors provided in documentation [34].

- Leverage Advanced Hardware: Consider MEMS-based multi-object spectrographs (MOS) like those using Digital Micromirror Devices (DMDs). These allow for optimal slit configurations and simultaneous sky sampling. Next-generation Micro-Mirror Devices (MMDs) are being developed with larger mirrors and higher tilt angles to maximize throughput and field of view [11].

- Site Selection for Ground-Based Astronomy: Sky noise is highly dependent on atmospheric conditions. Sites with low precipitable water vapor (PWV), like the South Pole, exhibit significantly lower sky noise, which can improve flux limits by an order of magnitude compared to sites like Mauna Kea [35].

Problem: SNR Limited by Detector and Instrument Noise

Symptoms:

- Poor SNR with short integration times.

- High noise floor even after dark subtraction.

- The SNR does not improve as expected with increasing signal.

Solutions:

- Optimize Detector Selection and Operation: Understand the key noise sources in your detector and operate in the regime that minimizes them. The table below summarizes the SNR behavior in different noise-limited regimes, where s is the signal in counts [37].

| Dominant Noise Source | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) |

|---|---|

| Shot Noise Limited (High signal) | ( \text{SNR} \approx \sqrt{s} ) |

| Read Noise Limited (Low signal) | ( \text{SNR} \propto s ) |

| Dark Current Noise Limited | ( \text{SNR} = \frac{s}{\sqrt{2 \cdot \text{(Dark Current)}}} ) |

- Characterize Your Detector: Measure the SNR performance of your detector across different signal levels. The plot below shows typical performance for common detectors, illustrating the transition from read-noise to shot-noise limitation [37].

- Employ Computational Enhancements: For Raman spectroscopy, deep learning models like SlitNET can be trained to reconstruct high-resolution spectra from low-resolution data acquired with a wider slit. This technique effectively breaks the traditional trade-off, allowing for high throughput (using a wide slit) and high resolution simultaneously, thereby enhancing analytical sensitivity [38].

- Use Appropriate SNR Calculation Methods: As outlined in the FAQs, adopt multi-pixel SNR calculation methods (area or fitting) to more accurately quantify the true SNR of your spectral features, which is particularly critical for data near the detection limit [39].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Pixel SNR Calculation for Raman Spectra

Application: Quantifying the Signal-to-Noise Ratio of a Raman band to statistically validate detection, particularly for weak features [39].

Materials:

- Raman Spectrometer: Such as a SHERLOC-like deep UV Raman instrument or equivalent [39].

- Stable Sample: With a known Raman band for method validation.

- Data Processing Software: Capable of baseline correction and spectral fitting.

Methodology:

- Data Acquisition: Collect a series of spectra from the sample. For weak signals, collect multiple successive spectra to allow for averaging [39].

- Baseline Correction: Pre-process all spectra to subtract any fluorescent background or instrumental baseline.

- Signal (S) Calculation: Choose one of the following multi-pixel methods:

- Noise (σS) Calculation: Calculate the standard deviation of the signal (S) obtained from the multiple successive spectra. If using the fitting method, the standard error of the fit parameters can also be propagated [39].

- SNR Calculation: Compute the SNR for the Raman band using the formula: SNR = S / σS [39]. A result ≥3 is generally considered statistically significant for detection [39].

Protocol 2: Background Subtraction via Nodding for Fixed Slit Spectroscopy

Application: Accurately removing sky background contamination for point or compact sources in fixed slit spectroscopic observations [34].

Materials:

- Telescope & Spectrometer: With fixed slit capability and a dithering mechanism.

- Observation Planning Tool: To define the nodding pattern.

Methodology:

- Strategy Selection: Choose an in-scene nodding pattern. For fixed slit spectroscopy, a 2, 3, or 5-point nodding pattern is recommended [34].

- Exposure Setup: Configure the instrument settings (grating, filter, integration time). Ensure the same disperser is used for all nods within a sequence to enable pixel-to-pixel subtraction in the pipeline [34].

- Data Acquisition: Execute the observation sequence. The telescope will automatically move to each nod position and acquire an exposure.

- Pipeline Processing: The data pipeline will perform pairwise pixel-to-pixel subtraction of subsequent exposures (e.g., nod B is subtracted from nod A) to remove the background. The resulting background-subtracted images are then co-added [34].

- SNR Verification: The final SNR will scale based on the number of nods and exposure parameters. Refer to scaling factors (e.g., for a 2-point nod, SNR is approximately equal to the basic unit SNR for a single pointing, SNR₁ₚₜ) to validate the observation's success against predictions [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key components and their functions in a spectroscopic system, relevant for optimizing SNR.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Cooled CCD/CMOS Detector | Reduces dark current noise by operating at low temperatures (e.g., -70°C), crucial for long-exposure measurements [38] [37]. |

| Variable Width Entrance Slit | Allows the user to manually tune the trade-off between optical throughput (SNR) and spectral resolution to match experimental needs [7] [38]. |

| Digital Micromirror Device (DMD) | A programmable MEMS slit mask that enables multi-object spectroscopy by selectively directing light from many targets into the spectrograph, dramatically improving observing efficiency [11]. |

| Master Background Spectrum | A flux-calibrated spectrum of the "blank sky," used for subtraction from the target spectrum to remove in-field and stray light background components [34]. |

| Synthetic Raman Spectrum Library | A large, simulated dataset of Raman spectra with known properties, used to train deep learning models for tasks like spectral denoising and resolution enhancement [38]. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

Mitigating Injection Efficiency Losses in Fiber-Optic Coupling Systems

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Fiber-Optic Coupling Issues

The following guide addresses common problems that can lead to injection efficiency losses in fiber-optic coupling systems, which are critical for maintaining signal integrity in multi-object spectrometer accuracy research.

Issue 1: High Insertion Loss

- Symptoms: Lower-than-expected optical power at the receiver; reduced signal-to-noise ratio.

- Causes: Axial, angular, or lateral misalignment between fibers; mode field diameter mismatch between laser diodes and single-mode fibers (SMFs); contaminated or damaged fiber end-faces [40] [41] [42].

- Solutions:

- Perform active alignment with sub-micron precision to optimize position [42].

- Use beam-expanding fibers or integrated microlenses (e.g., aspherical microlenses on coreless fiber segments) to improve mode field matching and achieve coupling efficiency (CE) up to 92% [40].

- Implement regular inspection and cleaning of connector end-faces to remove contaminants [41].

Issue 2: Signal Instability and Drift

Issue 3: Excessive Spectral Noise and Back-Reflection

- Symptoms: Poor signal-to-noise ratio; signal distortion leading to increased bit error rates.

- Causes: Back-reflections from imperfect fiber end-faces; electromagnetic interference; pump power amplification in long-distance Brillouin sensing [42] [44].

- Solutions:

- Use angled physical contact (APC) connectors to minimize back-reflections.

- Ensure proper grounding and shield sensitive electronic components from interference.

- In Brillouin sensing systems, carefully manage the power and polarization of pump pulses and probes to mitigate non-linear effects [44].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is fiber coupling efficiency so critical for multi-object spectrometer accuracy? Coupling efficiency directly impacts the optical power and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) reaching the spectrometer. In multi-object systems, where precise slit configurations are used to isolate light from multiple targets, low CE can lead to inaccurate spectral line intensity measurements. This is paramount in drug development research, where subtle spectral shifts can indicate molecular interactions [40] [42].