Optimizing Optical Transmittance: Advanced Cleaning and Maintenance Protocols for Precision Biomedical Systems

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on maintaining and optimizing optical window transmittance in sensitive biomedical instrumentation.

Optimizing Optical Transmittance: Advanced Cleaning and Maintenance Protocols for Precision Biomedical Systems

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on maintaining and optimizing optical window transmittance in sensitive biomedical instrumentation. It covers the fundamental impact of contamination on optical performance and data integrity, details advanced cleaning methodologies and material engineering solutions, presents systematic troubleshooting and optimization protocols, and establishes rigorous validation and comparative assessment frameworks. By integrating foundational science with practical application, this resource aims to enhance the reliability and longevity of optical systems critical to clinical research and diagnostic accuracy.

The Critical Link Between Optical Window Purity and Data Integrity in Biomedical Sensing

Fundamental Principles of Light Transmission and Scattering in Optical Windows

An optical window is a flat, parallel, and optically transparent component designed to separate two distinct environments while maximizing the transmission of incident light [1]. In scientific experiments, particularly in drug development and analytical research, the performance of these windows is critical. Optimal light transmission ensures accurate spectroscopic measurements, reliable imaging, and valid experimental data. However, factors such as material properties, surface contamination, and improper cleaning can introduce light scattering and absorption, degrading performance. This guide outlines the fundamental principles of light interaction with optical windows and provides practical protocols for maintaining optimal transmittance, a core focus of research in optical system optimization [1] [2].

Fundamentals of Light-Material Interaction

Key Principles of Light Transmission

When light strikes an optical window, several interactions determine how much light is transmitted:

- Refraction: The bending of light as it passes from one medium (e.g., air) into the optical window. The degree of bending is governed by the material's refractive index (nd). A higher refractive index indicates that light slows down more significantly and bends to a greater degree [1].

- Absorption: The material of the window absorbs a fraction of the light energy, converting it to heat. The absorption coefficient (μa) quantifies this property, with a lower value being desirable for most transparent windows [2].

- Scattering: This occurs when light is deflected from its original path due to interactions with imperfections, such as surface roughness, internal defects, or contaminants. Scattering reduces the intensity of the transmitted beam and can create background noise in detection systems [2].

The Impact of Scattering on Data Quality

In quantitative applications like UV/VIS or IR spectroscopy, uncontrolled scattering leads to:

- Reduced Signal-to-Noise Ratio: Scattered light that reaches the detector does not carry meaningful sample information, increasing noise.

- Inaccurate Absorbance Readings: Apparent absorption may be overestimated due to light loss from scattering.

- Poor Reproducibility: Variable contamination or surface damage introduces unpredictable error between experiments.

The goal is to maximize transmission, defined as the percentage of incident light that passes through the window and reaches the detector. A common industry standard is to consider the useful wavelength range of a material as the region where transmission exceeds 80% [1].

FAQ & Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ 1: How do I select the correct optical window material for my specific application?

The primary consideration is the wavelength range of your light source and the need to maximize transmission within that range.

Answer: The choice of material is paramount and depends directly on your operational wavelength [1]. The table below summarizes key properties of common optical window materials.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Optical Window Materials

| Material | Wavelength Range | Refractive Index (nd) | Key Properties and Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| UV Fused Silica | 180 nm - 2.5 µm [1] | ~1.46 [1] | High transmission deep into UV; resistant to laser damage; ideal for UV spectroscopy and laser applications [1]. |

| N-BK7 (Optical Glass) | 350 nm - 2.0 µm [1] | ~1.52 [1] | Economical; high transmission in visible spectrum; common in imaging and display systems [1]. |

| Sapphire (Al2O3) | 150 nm - 4.5 µm [1] | 1.768 [1] | Extremely hard and durable; chemically and thermally resistant; suitable for harsh environments [1]. |

| Calcium Fluoride (CaF2) | 130 nm - 9.5 µm [1] | 1.43 [1] | Wide transmission range; low absorption; used in UV and IR laser applications and cryogenics [1]. |

| Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) | 1 µm - 14 µm [1] | 2.403 [1] | Excellent for high-power CO2 laser systems (10.6 µm); low absorption and dispersion; soft and easily scratched [1]. |

| Germanium (Ge) | 2 µm - 16 µm [1] | 4.00 [1] | Opaque in visible light; high refractive index; ideal for thermal imaging and IR systems; requires anti-reflective coatings [1]. |

FAQ 2: My spectroscopic measurements show a consistent loss of signal intensity. Could the optical windows be the cause?

Yes, this is a common symptom. The issue likely stems from either surface contamination or bulk material degradation.

Answer: A consistent signal drop indicates reduced transmittance. Follow this diagnostic workflow to identify the root cause.

FAQ 3: What is the proper way to clean an optical window to avoid damaging it?

Improper cleaning is a major cause of permanent surface damage and increased scattering. The cardinal rule is: "If it's not dirty, don't clean it." [3] [4] Unnecessary handling and cleaning pose the greatest risk.

Answer: Always follow a graded approach, starting with the least invasive method.

Table 2: Step-by-Step Optical Window Cleaning Protocol

| Step | Procedure | Critical Notes & Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Preparation | Work in a clean, low-dust environment. Wear appropriate powder-free gloves (nitrile or cotton) to prevent fingerprints [3] [4] [5]. | Reagents: Powder-free gloves [3]. |

| 2. Initial Inspection | Hold the window near a bright light and view it from different angles. Look for dust, smudges, or Newton's rings that indicate contamination [3]. | |

| 3. Dry Cleaning (Dust Removal) | Always remove dust before wiping. Use a blower bulb or canned air to gently dislodge particles. Hold the nozzle several inches away and use short bursts [3] [4] [5]. | Never wipe a dry, dusty surface, as this grinds particles into the surface like sandpaper [3]. |

| 4. Wet Cleaning (For Smudges) | If staining persists, use a solvent. Lightly moisten a lint-free lens tissue or microfiber cloth with a suitable optical solvent. Gently wipe the surface using a circular motion from the center outward or a straight line across [4] [5]. | Reagents: Reagent-grade isopropyl alcohol (90%) or a mixture of 60% acetone / 40% methanol. Warning: Acetone cannot be used on plastic optics or housing [3] [4]. |

| 5. Drying & Storage | Allow the solvent to evaporate completely. If needed, use a clean blower to gently dry from one direction to prevent streaking [3]. Store in a clean container, wrapped in lens tissue [3]. |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Cleaning

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Compressed Air / Blower Bulb | Removes loose particulate matter without physical contact. | Safer than canned air, which can propel condensate. Always hold can upright [3] [6]. |

| Lint-Free Lens Tissue / Microfiber Cloth | Provides a soft, non-abrasive medium for wiping. | Never reuse a tissue. Never use dry tissue on an optic [3] [5]. |

| Reagent-Grade Isopropyl Alcohol | Mild solvent effective for removing fingerprints and oils. | Safe for most glass and coated optics; slower evaporation can leave marks if not dried properly [3] [4]. |

| Acetone/Methanol Mixture (60/40) | Stronger solvent mixture for stubborn contaminants. | Acetone alone dries too quickly; methanol slows evaporation for better cleaning. Use with acetone-impenetrable gloves. Not for plastics [3]. |

| Cotton Swabs | Allows for precise cleaning of small or hard-to-reach areas. | Use medical-grade, non-sterile swabs with degreased fibers to minimize lint [4]. |

Advanced Topic: Light Transport and Scattering Regimes

Understanding light transport helps model how scattering affects measurements. In highly scattering materials, light propagation can be described by diffusion theory once photons have undergone multiple scattering events and lost their initial directionality [2]. This regime is characterized by the reduced scattering coefficient (μs') and the absorption coefficient (μa). The relationship between these coefficients determines which model is appropriate.

For optical windows, the goal is to operate far from the diffuse scattering regime by maintaining pristine, smooth surfaces that minimize scattering coefficients. Contamination and damage significantly increase scattering (μs), pushing the system toward this diffuse state and degrading performance.

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Contaminated Optical Windows

This guide helps diagnose and resolve issues related to particulate, film, and residue contamination on optical components, which critically degrade performance by reducing transmission, increasing scatter, and introducing haze.

| Observable Symptom | Possible Contaminant Type | Primary Impact on Optical Performance | Recommended Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Haze or cloudiness on viewing windows [7] | Molecular film (outgassed hydrocarbons) | Increased light scatter (haze), reduced transmission [7] | Implement controlled bake-out procedures; use certified cleanroom materials [7] |

| Visible dust or dark spots on ferrule end-face [8] | Particulates (dust, skin cells, fibers) | Signal attenuation (0.5-3 dB loss), increased error rates [8] | Use one-click cleaners or gel-based tips; employ static-control measures [8] |

| Reduced laser power or system overheating [9] | Debris buildup from ablation processes | Throughput loss, thermal regulation failure, potential component damage [9] | Perform daily pre-/post-operation cleaning; replace protection window [9] |

| Visible burn marks or discoloration [9] | Carbonaceous deposits from laser-induced contamination (LIC) | Permanent absorption damage, altered beam quality (M² factor) [10] | Replace damaged window; control ambient air and hydrocarbon sources [10] |

| Thin, sticky film not removed by dry cleaning [8] | Oil residues (fingerprints, lubricants, plasticizers) | Creates a "residue trap" for more particles, signal fluctuation [8] | Use wet cleaning pens with high-purity isopropanol; follow with dry wipe [8] |

| High error rates after cleaning with alcohol [8] | Contaminant film redistributed by alcohol | Diluted contaminants re-congeal into a uniform interference layer [8] | Ensure mechanical removal (swabbing) accompanies solvent use [8] |

| Unidentified peaks in mass spectra [11] | Soaps, plasticizers, quaternary ammonium compounds | Obscures analyte peaks of interest, complicates chemical analysis [11] | Avoid skin contact, use non-contaminating plastics (e.g., PTFE), minimize handling [11] |

Troubleshooting Sample Preparation for Chromatography

Contamination during sample preparation can lead to inaccurate analytical results, column damage, and instrument downtime.

| Common Issue | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor or variable analyte recoveries [12] [11] | Analyte loss to surfaces, contamination from SPE cartridge, sample degradation [11] | Optimize SPE conditioning/elution; use internal standards; minimize sample handling [13] [11] |

| High background contamination in samples [12] [11] | Plasticizers (e.g., phthalates), soaps/detergents, impurities in solvents [11] | Use high-purity reagents; avoid plastic containers; use dedicated glassware [13] [11] |

| Column clogging or pressure spikes [13] | Particulate matter in sample | Implement filtration (0.45 µm or 0.22 µm) prior to injection [13] |

| Unreliable method robustness [12] | Inconsistent sample prep, matrix effects, undetected contaminants [11] | Standardize protocols; use matrix-matched calibration; automate where possible [13] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Molecular films, often from outgassed hydrocarbons, are a primary concern. Sources include:

- Material Outgassing: Silicone seals, O-rings, adhesives, and composite materials release volatile compounds in vacuum or elevated-temperature conditions. These compounds then condense on cooler optical surfaces [7].

- Human Activity: Handling with bare hands can transfer quaternary ammonium compounds (from lotions and detergents) and skin oils [11].

- Ambient Laboratory Air: Airborne hydrocarbons and vapors from solvents or cleaning agents can deposit on exposed surfaces over time [11].

Q2: How does particulate contamination quantitatively impact the performance of optical data links?

The financial and performance impacts in fiber optic networks are severe and well-quantified [8]:

- Power Loss: Microscopic particles (0.5-9 microns) can cause optical power degradation of 0.5-3 dB.

- Financial Cost: Intermittent outages trigger troubleshooting cycles costing $900-$1,920 per incident. Downtime for critical infrastructure can exceed $50,000 per hour.

- False Alarms: Contamination causes "link flapping" and error correction spikes, leading to unnecessary module replacements costing $150-$800.

Q3: What are the best practices for cleaning optical connectors like SFPs to avoid damage?

- Tool Selection: Use tools designed for optics. Dry cleaning pens work for dust, but gel-based tips (>99% effective) are superior for stubborn residues [8].

- Avoid Compressed Air: It can generate static electricity that attracts more dust and blow contaminants deeper into the module [8].

- Use Alcohol Correctly: If using isopropanol, apply it to a lint-free swab, not directly to the connector. Always follow with a dry pass to remove dissolved residues, as alcohol alone spreads contaminants into a thin film [8].

- Inspect: Use a fiber scope (400x magnification) to verify end-face cleanliness after cleaning [8].

Q4: What specific contaminants interfere with high-sensitivity mass spectrometry, and how can they be prevented?

FT-ICR MS and other high-resolution techniques are extremely sensitive to low-concentration interferences [11]:

- Common Contaminants: Plasticizers (e.g., phthalates from plastics), soaps/detergents (on labware), quaternary ammonium compounds (from skin), and even iron-formate clusters have been identified.

- Prevention Strategies:

- Material Choice: Use glass, PTFE, or stainless steel instead of flexible plastics wherever possible.

- Handling: Wear gloves and avoid touching surfaces that contact the sample or solvent.

- Solvents: Use high-purity solvents and perform procedural blanks to identify contamination sources.

Experimental Workflows for Contamination Analysis

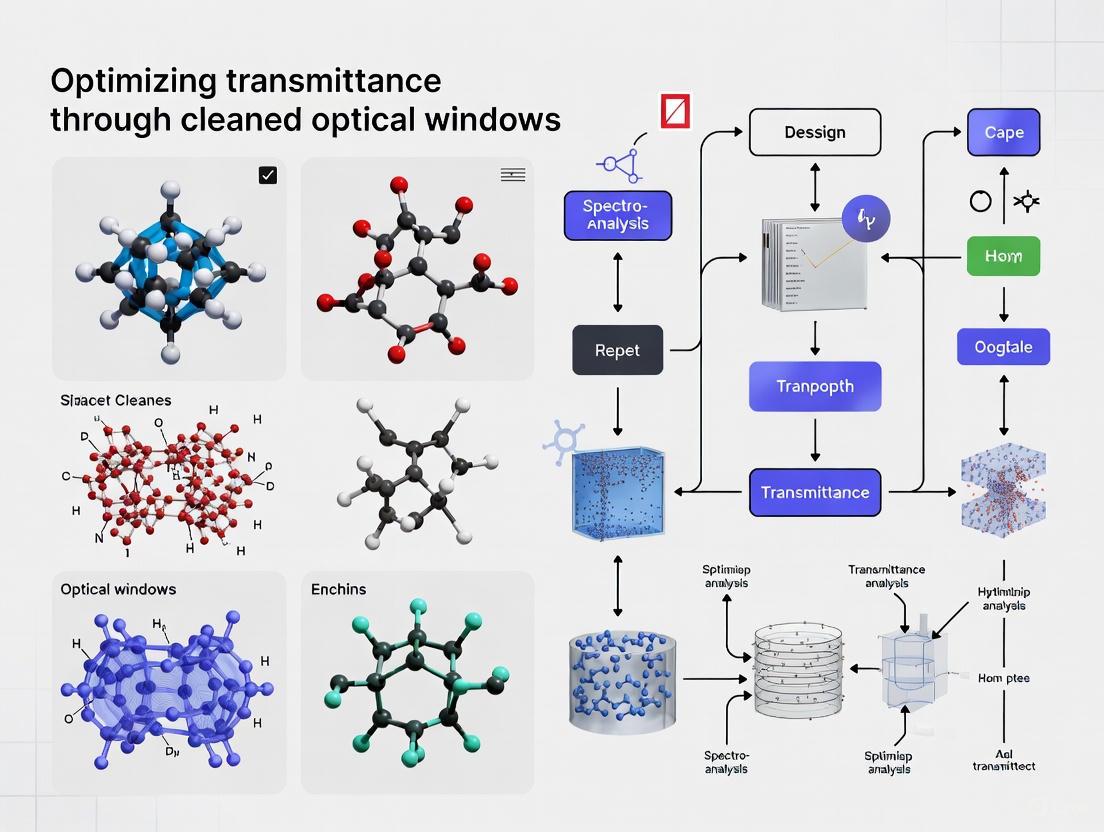

Diagram: Optical Window Contamination Assessment

Diagram: HPLC-MS Sample Preparation & Contamination Check

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (HPLC/MS Grade) | Minimize introduction of interfering compounds during sample preparation and analysis [11]. |

| Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Concentrate and purify analytes from complex matrices, removing many interfering contaminants [13]. |

| Syringe Filters (0.22 µm Pore Size) | Remove particulate matter from liquid samples to prevent column clogging and system damage [13]. |

| Nitrogen Evaporators | Gently and efficiently remove excess solvent to concentrate trace analytes without degrading them [13]. |

| Certified Cleanroom Materials | Low-outgassing seals, adhesives, and polymers that minimize molecular film deposition on optics [7]. |

| Specialized Optical Cleaners | One-click tools, gel-picks, and cassette systems designed to remove contaminants without damaging delicate surfaces [8]. |

| Molecular Sieves | Added to solvents to remove trace water, maintaining reproducibility in normal-phase HPLC separations [11]. |

| PTFE (Teflon) Labware | Inert containers and tubing that do not leach plasticizers like phthalates into sensitive samples [11]. |

Impact of Surface Contamination on Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Measurement Fidelity

Surface contamination on optical windows and components is a critical concern in scientific research and drug development, directly compromising data integrity by degrading the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) and measurement fidelity. Contaminants such as dust, skin oils, and residual chemicals act as sources of optical noise. Dust and particulate matter scatter incident light, diverting energy away from the intended optical path. Organic films, like fingerprints, absorb light, reducing total transmittance and potentially creating localized thermal points that can permanently damage delicate optical coatings [3] [14]. In the context of optimizing transmittance, even sub-micron levels of contamination can introduce significant error, leading to inaccurate spectrophotometric readings, flawed assay results, and unreliable experimental conclusions.

The relationship is straightforward: as contamination increases, useful signal strength decreases while optical noise increases. This reduction in SNR manifests as decreased measurement sensitivity, loss of feature resolution in imaging applications, and increased uncertainty in quantitative analyses [15]. For researchers relying on high-precision optical systems—such as those in HPLC detection, microplate readers, or inline process analytical technology (PAT)—maintaining pristine optical surfaces is not merely a best practice but a fundamental requirement for obtaining valid data.

Quantitative Impact of Contaminants on SNR

The following table summarizes the primary types of optical contaminants and their specific mechanisms for degrading SNR and measurement fidelity.

Table 1: Impact of Common Contaminants on Optical Performance

| Contaminant Type | Primary Effect on Optics | Impact on Signal | Impact on Noise | Overall Effect on SNR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dust & Particulates | Scatters incident light [3] | Decreases intensity | Increases scatter | Severe Reduction |

| Skin Oils & Fingerprints | Absorbs light; can damage coatings [3] [14] | Decreases transmittance | Increases absorption | Severe Reduction |

| Residual Solvents | Leaves films causing light interference [3] | Alters phase/path | Increases scatter/streaking | Moderate Reduction |

| Water Spots | Refracts light at microscopic level | Creates focal deviations | Increases scatter | Moderate Reduction |

The quantitative impact of these contaminants is a function of their density and composition. For instance, a thin, uniform oil film might cause a predictable and potentially correctable drop in transmittance. In contrast, random particulate contamination creates stochastic noise that is far more difficult to correct algorithmically. In pharmaceutical cleaning validation, studies aim to detect residue levels as low as 1-500 µg/25cm², as these minuscule amounts can be significant in sensitive processes [15]. In laser-based systems, absorbed energy from contaminants can create thermal lensing effects or even permanently damage the optical coating, leading to an irreversible degradation of system performance [3] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Impact Analysis

Protocol 1: Controlled Contamination and Transmittance Measurement

Objective: To quantitatively correlate specific surface contaminants with a reduction in optical transmittance and SNR. Materials: Clean optical window samples, spectrophotometer, lint-free gloves, controlled contaminants (e.g., ISO 12103-A1 test dust, synthetic sebum), optical power meter, lens tissue, and optical-grade solvents [3] [14].

- Baseline Measurement: Using gloved hands and following proper handling techniques, establish a baseline transmittance spectrum for the clean optical window using the spectrophotometer across the relevant wavelength range (e.g., 200 nm - 1100 nm) [14].

- Application of Contaminant: Apply a precisely measured quantity (e.g., 0.5 µL) of a specific contaminant (e.g., synthetic sebum) to the optical surface. For particulate matter, use a dust deposition chamber to achieve a controlled, uniform density.

- Post-Contamination Measurement: Remeasure the transmittance spectrum of the contaminated window using the exact same instrument settings.

- SNR Calculation: Calculate the decrease in signal (peak transmittance) and the increase in noise (standard deviation of baseline signal in a non-absorbing spectral region). Compute the SNR for both the clean and contaminated states.

- Data Analysis: Plot the percent reduction in transmittance and SNR against the contaminant type and density. This data directly quantifies the sensitivity of your optical system to specific contaminants.

Protocol 2: Validation of Cleaning Efficacy

Objective: To verify that a cleaning procedure restores the optical surface to its original transmittance and SNR performance. Materials: Contaminated optical window, appropriate solvents (e.g., reagent-grade isopropyl alcohol, acetone/methanol blend), lens tissue or Webril wipes, compressed air or dusting gas [3] [14].

- Pre-Cleaning Measurement: Measure and record the transmittance spectrum and calculate the SNR of the contaminated window.

- Cleaning Procedure:

- Dry Removal: Use a blower bulb or canned air held upright to remove loose, dry particulates. Never wipe a dusty surface first [3] [14].

- Solvent Cleaning: Select the appropriate solvent. For unknown coatings, start with a mild isopropyl alcohol or de-ionized water [3].

- Wiping Technique: Apply the solvent to a fresh sheet of lens tissue or a Webril wipe. Never use a dry wipe. Using the "drop and drag" technique for flat surfaces or the "applicator" method for mounted optics, wipe the surface slowly and steadily in a single motion, lifting contaminants away [3] [14].

- Post-Cleaning Measurement: After the solvent has fully evaporated, remeasure the transmittance spectrum and recalculate the SNR.

- Efficacy Calculation: Determine the percentage recovery of transmittance and SNR. Successful cleaning should return performance to within 1-2% of the original baseline measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Optical Cleaning

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Cleaning and Inspection

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reagent-Grade Solvents | High purity prevents film residue. A blend of 60% acetone/40% methanol is effective for dissolving organic debris [3]. | Isopropyl alcohol is safer but slower drying. Always use acetone-impermeable gloves [3]. |

| Lens Tissue | Low-lint wiper for use with solvents. Never used dry to avoid scratching [3] [14]. | Use each tissue only once. Fold to create a fresh, clean surface for each wipe [3]. |

| Webril Wipes | Soft, pure-cotton wipers that hold solvent well and are less abrasive than some tissues [14]. | Ideal for more robust cleaning where lens tissue might tear. |

| Compressed/Dusting Gas | Removes loose particulate matter without physical contact with the surface [3] [14]. | Hold can upright to avoid propellant discharge. Use short blasts at a grazing angle. |

| Powder-Free Gloves | Prevents transfer of skin oils and salts, which are highly corrosive to optical coatings [3] [14]. | Nitrile or latex gloves are suitable. Never handle optical surfaces with bare hands. |

| Inspection Light Source | A bright, visible light source used to illuminate the optical surface at an angle to reveal contamination via scattering [3] [14]. | Essential for pre- and post-cleaning inspection. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: After cleaning my optical window, my measurements are still noisy. What did I do wrong?

Answer: This is a common issue with several potential causes:

- Streaking: This occurs if too much solvent was used, or if the wiping motion was too fast, preventing even evaporation. Solution: Repeat the cleaning process using a less-saturated lens tissue and a slower, single-direction wipe [3].

- Residual Film: The wrong solvent may have been used, or the solvent grade may have been low purity. Solution: For organic residues, ensure you are using a proper blend of spectroscopic-grade acetone and methanol. For aqueous residues, use de-ionized water [3].

- Micro-scratches: If dry wiping was attempted or a dirty tissue was used, the surface may be lightly scratched. Solution: Always use solvent with lens tissue. Inspect the surface under a bright light. If scratched, the optic may need to be repolished or replaced [14].

FAQ 2: How can I tell if a drop in signal is from a dirty optic or a failing light source in my instrument?

Answer: Perform a systematic diagnostic:

- Inspect: Visually inspect all accessible optics (windows, lenses) using a bright light at an angle. Contamination will scatter light and be visible [14].

- Clean: If contamination is found, clean the optic using the proper protocol and remeasure. If signal restores, the optic was the culprit.

- Isolate: If the signal does not restore, the issue may be internal to the instrument (e.g., a failing lamp, degraded detector, or internal dirt). Consult the instrument manual for diagnostic modes and contact technical service.

FAQ 3: Are there any optics that should NEVER be cleaned with solvents and wipes?

Answer: Yes. Certain optics are extremely sensitive and can be destroyed by physical contact.

- Pellicle Beamsplitters: The thin membrane can be broken by air pressure or any physical contact. Only use canned air from a safe distance, if at all [14].

- Holographic or Ruled Gratings: The fine grooves are easily damaged. Cleaning is typically limited to careful use of compressed air [3] [14].

- First-Surface Unprotected Metallic Mirrors: The soft coating scratches easily. Use compressed air only [3].

- Polka Dot Beamsplitters: Solvents or water can deteriorate the coating. Use only compressed air in a dust-free environment [3]. Always consult the manufacturer's instructions for use (IFU) before cleaning any specialized optic [16] [14].

FAQ 4: In a pharmaceutical environment, how do we validate that an optic is "clean enough" for our measurements?

Answer: Beyond visual inspection, cleaning validation should be performance-based.

- Establish a Baseline: Record the transmittance or SNR of the optic when it is known to be clean and new.

- Set a Threshold: Define an acceptable performance threshold (e.g., "SNR must be no less than 95% of baseline").

- Verify Post-Cleaning: After each cleaning, measure the performance and compare it to the threshold. If it meets or exceeds the threshold, the optic is validated for use. This quantitative approach aligns with the principles of cleaning validation in pharmaceutical manufacturing, where the goal is to ensure the absence of contaminants that would interfere with process or product quality [15].

Workflow Diagrams for Contamination Management

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting workflow for signal degradation

Diagram 2: Optimal workflow for cleaning optical surfaces

Troubleshooting Guide: Laser Transmission Issues from Window Contamination

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradual drop in laser power at the powder bed. | Contamination of the optical window by vaporized alloy particulates and spatter, reducing transmittance [17]. | 1. Perform visual inspection of the optical window for a visible film or dots.2. Measure transmittance with a power meter before and after window cleaning.3. Review in-situ monitoring data for increased spatter activity prior to power drop [17]. | 1. Clean the optical window using an approved protocol.2. Optimize process parameters (e.g., laser power, scan speed) to minimize spatter [17].3. Implement protective measures: install a sacrificial shield or ensure gas flow is optimized to carry contaminants away [17]. |

| Increased defects (e.g., lack of fusion, porosity). | Reduced laser energy delivery prevents complete powder melting [17]. | 1. Analyze defect location correlation with laser path.2. Correlate sensor data with defect locations; check for increased spatter signatures in process monitoring data [17]. | 1. Recalibrate laser parameters to compensate for energy loss (after cleaning).2. Establish a predictive maintenance schedule for the optical system based on process hours. |

| Unstable or erratic melt pool. | Inconsistent laser energy due to uneven contamination on the window. | Use high-speed in-situ monitoring (coaxial or off-axis) to observe melt pool fluctuations and spatter behavior in real-time [17]. | 1. Clean or replace the optical window.2. Verify the alignment of the entire optical delivery system. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do vaporized alloy particulates actually reach and contaminate the optical window? During the L-PBF process, the intense laser energy can create a vapor plume from the melt pool. This plume contains vaporized metal and can eject hot spatter. The protective gas flow, if not optimally configured, can carry these particulates upward where they condense and adhere to the cooler surface of the optical window [17].

Q2: What is the quantitative impact of a contaminated window on my build process? A contaminated window acts as a filter, attenuating the laser power that reaches the powder bed. The degree of power loss depends on the thickness and density of the contaminant layer. This can lead to a significant reduction in energy density, causing defects like incomplete melting, high porosity, and a degradation of the mechanical properties of the final part [17].

Q3: What are the best methods for in-situ detection of spatter and contamination events? The most common method is using high-speed visible-light cameras in an off-axis configuration. These can track the trajectory and quantity of spatter ejection [17]. For a more detailed analysis, infrared imaging can monitor the temperature distribution of the plume and spatter, while schlieren imaging can visualize the flow of the hot gas and vapor plume itself [17].

Q4: Are there any material-specific factors that influence this contamination? Yes, different alloys have different vapor pressures and surface tensions at their melting points, which can affect the intensity of the vapor plume and the amount of spatter generated. Alloys with volatile elements may be more prone to generating contamination.

Q5: What is the recommended cleaning protocol for optical windows in L-PBF systems? Always follow the manufacturer's guidelines. A general protocol involves:

- Safe Removal: Allow the system to cool and follow safety procedures for removing the window.

- Dry Dusting: Use a stream of clean, dry air or inert gas to remove loose particles.

- Wet Cleaning: Gently clean with a solvent like isopropyl alcohol and lint-free wipes, moving in one direction to avoid scratching.

- Inspection: Re-inspect the window for smudges or residue before reinstalling.

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Transmittance Loss

Objective: To measure the degradation of optical window transmittance over a series of build cycles and correlate it with in-situ spatter detection data.

Materials & Equipment:

- L-PBF system with an accessible optical window.

- Calibrated laser power meter.

- High-speed visible-light camera (for off-axis spatter monitoring) [17].

- Logbook for documenting build parameters.

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Before any builds, measure the initial laser power (P₀) directly at the output of the optical window using the power meter.

- Contamination Cycle: Execute a standardized build job or a series of jobs designed to promote spatter generation (e.g., using over-saturated energy parameters).

- In-situ Monitoring: Throughout the build, use the high-speed camera to record spatter events, quantifying their frequency and trajectory [17].

- Post-Build Measurement: After the build cycle and allowing the system to cool, carefully remove the window and measure the transmitted laser power (P₁) again under the same conditions as Step 1.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage transmittance loss:

[(P₀ - P₁) / P₀] * 100%. Correlate this value with the quantitative spatter data collected from the high-speed footage. - Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5 over multiple build cycles to establish a degradation curve.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance to Research |

|---|---|

| High-Speed Visible-Light Camera | Essential for the in-situ detection and analysis of spatter behavior, including trajectory and quantity [17]. |

| Calibrated Laser Power Meter | Used to quantitatively measure the transmittance of the optical window before and after contamination cycles. |

| Schlieren Imaging System | Allows for the visualization of the vapor plume and gas flow dynamics around the melt pool, which transport contaminants [17]. |

| Infrared (IR) Thermal Camera | Enables the mapping of temperature distributions of the melt pool, spatter, and vapor plume, providing insight into the process energy [17]. |

| Isopropyl Alcohol & Lint-Free Wipes | Standard materials for safely and effectively cleaning optical windows without damaging their surface. |

| Sacrificial Fused Silica Windows | Inexpensive, high-transmittance optics that can be used as replaceable shields to protect the main, more expensive focusing lens. |

Workflow Diagram: Contamination & Mitigation

Experimental Setup for Transmittance Analysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of transmittance loss in optical windows used in laboratory settings? The most common causes are surface contamination and soiling. This includes the accumulation of particulate matter (PM), body fluids (e.g., blood), ground substance, rinsing fluids, bone dust, or smoke plumes generated by surgical cautery devices on the optical surface [18]. These contaminants scatter and absorb light, leading to a direct reduction in optical transmittance.

FAQ 2: How does the wavelength of light affect the measurement of soiling-induced transmittance loss? Soiling loss estimation is highly dependent on the wavelength used for measurement. Studies have shown that the Ultraviolet and Visible regions have low accuracy in estimating actual soiling losses on surfaces like glass coupons. The most accurate soiling estimates for polycrystalline materials are achieved using wavelengths in the 760 nm to 850 nm range (the Near-Infrared spectrum), which minimizes error compared to other wavelengths [19].

FAQ 3: What is the difference between direct and hemispherical transmittance measurements for quantifying soiling? Direct transmission measures light that passes straight through a material without being scattered. Hemispherical transmittance measures both direct and diffuse (scattered) transmitted light. For soiling estimation in real-world conditions, hemispherical transmittance measurements provide better results because they account for the combined effect of direct and diffuse solar radiation, which more accurately represents the actual performance loss [19].

FAQ 4: Can surface coatings prevent or reduce transmittance loss? Yes, surface coatings are an effective preventive method. Research indicates that a hybrid solution—combining a hydrophilic or hydrophobic coating on the optical lens with the use of an irrigation system—is the most promising method for maintaining optical surface cleanliness and preventing fouling. These coatings help prevent contaminants from adhering to the surface [18].

FAQ 5: What are the standard methods for validating the cleanliness of an optical surface or equipment? In regulated industries like pharmaceuticals, cleaning validation ensures equipment is free from contaminants. Standard methods include:

- Swab sampling: Using a swab to collect residues from specific, often hard-to-clean, spots on a surface [20].

- Rinse sampling: Analyzing the fluid used to rinse a piece of equipment to detect dissolved contaminants [20].

- Optical methods: Emerging technologies like Near Infra-Red Chemical Imaging (NIR-CI) are being developed for real-time, non-invasive cleanliness verification by detecting spectral signatures of residual substances [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Gradual Reduction in Signal Clarity or Intensity

Symptoms:

- A steady, gradual decline in signal strength or quality over time.

- Increased noise or error rates in data transmission.

- The issue is not resolved by checking equipment connections.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Inspect and Clean Optical Surfaces | Cause: Contamination (dust, residues). Use a visual inspection probe [21]. Clean with isopropyl alcohol (IPA) and lint-free wipes [22]. |

| 2 | Quantify Transmittance Loss | Cause: Soiling. Use a spectrophotometer to measure hemispherical transmittance of a clean vs. soiled reference coupon. Calculate Optical Transmission Loss (OTL) [19]. |

| 3 | Verify Wavelength Accuracy | Cause: Suboptimal measurement wavelength. For accurate soiling loss estimation, use light sources or sensors operating in the 760-850 nm range [19]. |

| 4 | Check for Surface Damage | Cause: Scratches or degraded coatings. Replace damaged optical components if cleaning doesn't restore performance. |

Problem 2: Sudden or Intermittent Signal Drop

Symptoms:

- A complete or near-complete loss of signal that occurs abruptly.

- Signal that comes and goes unpredictably.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Check Physical Connections | Cause: Loose connectors or cables. Ensure all fiber-optic cables and connectors are secure. Inspect for physical damage [23]. |

| 2 | Inspect and Clean Connectors | Cause: Dirty or damaged connectors. Microscopic dust or scratches can cause major signal loss. Inspect, clean, or replace connectors [21] [22]. |

| 3 | Perform a Loopback Test | Cause: Faulty transceiver. This test isolates the transceiver from other network issues. If it fails, the transceiver is likely faulty [24]. |

| 4 | Verify Power Levels | Cause: Improper signal power. Use an optical power meter. Signal can be too low (weak) or too high (saturating receiver) [21] [22]. |

Problem 3: Consistent Poor Performance After Cleaning

Symptoms:

- Signal quality or intensity remains unacceptably low even after manual cleaning of the optical window.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Evaluate Cleaning Method | Cause: Ineffective cleaning. Manual wiping may smear contaminants. Consider automated systems (e.g., lens irrigation with suction) [18] and validate with swab/rinse sampling [20]. |

| 2 | Assess for Coating Degradation | Cause: Worn-out anti-fouling coating. Hydrophobic/hydrophilic coatings can degrade. If cleaning is ineffective, the coating may need reapplication [18]. |

| 3 | Confirm Analytical Method Validity | Cause: Incorrect residue detection. Ensure the analytical method (e.g., TOC, HPLC) is validated for detection limit and recovery efficiency for the specific contaminant [25]. |

Quantitative Data on Soiling and Transmittance Loss

Table 1: Key Findings from a Field Study on Optical Soiling (Gandhinagar, India)

| Parameter | Value / Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Daily Soiling Rate | 0.39 ± 0.07 %/day [19] | Quantifies how quickly transmittance loss accumulates in a specific environment. |

| Best Wavelength for Soiling Estimation (Polycrystalline) | 760 to 850 nm [19] | Using these wavelengths minimizes error when optically estimating soiling loss. |

| Low Accuracy Wavelength Regions | Ultraviolet (RMSE: 7.89 ± 6.39) and Visible [19] | Highlights inaccuracy of UV/VIS light for soiling measurement. |

| Recommended Measurement Type | Hemispherical Transmittance [19] | Provides most accurate soiling loss estimate by accounting for direct and diffuse light. |

Table 2: Common Cleaning Methods for Optical Surfaces and Their Limitations

| Method | Description | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Manual Wiping | Rubbing the lens against soft tissue, organ, or withdrawing to wipe with gauze [18]. | Disrupts workflow, risks condensation upon reinsertion, and may not clean thoroughly [18]. |

| Lens Irrigation System | Hollow sheath with irrigation nozzle using saline or distilled water [18]. | Can cause unwanted fluid buildup; may leave bubbles/droplets; often doesn't clean satisfactorily [18]. |

| Integrated Wiper Devices | Devices with wipers, sponges, or cloths attached to trocars or endoscopes for in-situ cleaning [18]. | Can reduce cleaning time but may not improve overall procedure time due to setup needs [18]. |

| Hybrid Coating + Irrigation | Combining hydrophobic/hydrophilic coatings with irrigation systems [18]. | Cited as the most promising method, as coatings prevent fouling and irrigation aids in removal [18]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Contamination via Hemispherical Transmittance

Objective: To accurately quantify the transmittance loss of an optical window (e.g., glass coupon) due to surface soiling.

Materials:

- Spectrophotometer with an integrating sphere (for hemispherical measurement)

- Clean, identical glass coupons

- Access to the test environment (e.g., near lab equipment, outdoor setting)

Methodology:

- Baseline Measurement: Measure the initial hemispherical transmittance spectrum (e.g., 300-1100 nm) of a clean glass coupon. This is your reference.

- Field Exposure: Place multiple test coupons in the area of interest, alongside a soiling reference station if available. Leave them exposed for a defined period (e.g., 24 hours or several days).

- Post-Exposure Measurement: Carefully collect the coupons and measure their hemispherical transmittance spectrum again.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Optical Transmission Loss (OTL) or soiling ratio. One robust method is to weight the transmittance values by both the spectral irradiance of the standard AM1.5 solar spectrum and the spectral response of your detector material (e.g., polycrystalline silicon). Studies show this method provides highly accurate soiling estimates [19].

- Validation: For highest accuracy, correlate your optical results with a standard reference, such as the energy output difference between a clean and a soiled photovoltaic panel [19].

Protocol 2: Validating Cleaning Efficacy

Objective: To verify that a cleaning procedure effectively removes residues from an optical or equipment surface.

Materials:

- Appropriate swabs (e.g., polyester)

- Solvent (e.g., purified water, alcohol)

- Validated analytical equipment (e.g., HPLC for chemical residues, TOC analyzer, NIR Chemical Imager)

Methodology:

- Define Protocol: Develop a validation protocol specifying the residue(s) of interest, acceptance criteria (e.g., residue limit of 0.1% carryover), and sampling locations (focus on "worst-case" hard-to-clean areas) [25] [20].

- Soil the Surface: Contaminate the equipment with a known quantity of the substance (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient).

- Execute Cleaning: Perform the cleaning procedure to be validated (e.g., manual wipe, CIP).

- Sample the Surface:

- Analyze Samples: Use validated analytical methods to quantify the amount of residue recovered.

- Document and Report: Compare results against pre-defined acceptance criteria. A successful validation requires consistent results over multiple (e.g., three) consecutive cycles [20].

Experimental Workflow and Pathways

Workflow for Diagnosing Transmittance Loss

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Transmittance Loss and Cleaning Validation Research

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Glass Coupons | Standardized test substrates for quantifying soiling rates and transmittance loss in field studies [19]. |

| Spectrophotometer with Integrating Sphere | Instrument essential for measuring hemispherical transmittance spectra of soiled and clean surfaces [19]. |

| Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Coatings | Surface treatments applied to optical windows to reduce the adhesion of contaminants and facilitate cleaning [18]. |

| Validated Swabs & Solvents | Tools for direct surface sampling (swab sampling) to recover and quantify chemical residues for cleaning validation [20]. |

| Near-Infrared Chemical Imaging (NIR-CI) | An emerging, non-invasive process analytical technology for real-time detection and mapping of residual substances on equipment surfaces [15]. |

| Optical Power Meter | Device used to measure the absolute power of an optical signal, crucial for troubleshooting signal loss in fiber optic systems [21] [22]. |

| Fiber Optic Inspection Probe | A magnifying tool for visually inspecting the end-faces of optical connectors for contamination or damage [21] [22]. |

Proven Cleaning Methodologies and Next-Generation Coating Technologies for Maximum Transmittance

Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for Safe and Effective Optical Window Handling

This guide provides standardized procedures for the handling and cleaning of optical windows, a critical component in research and drug development. Proper maintenance is essential for optimizing light transmittance, ensuring experimental data accuracy, and protecting sensitive equipment. Adherence to these protocols minimizes surface damage and contamination, directly supporting research integrity and the reproducibility of results.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is proper handling of optical windows so critical in research experiments? Optical windows serve as the interface between your sensor and the object of interest. Improper handling can introduce contaminants like dust and skin oils, which permanently damage optical coatings and increase light scatter and absorption. This degrades image quality, reduces system performance, and compromises the validity of experimental data by affecting measured transmittance [26] [14].

Q2: What is the most common mistake when cleaning an optic? The most common and damaging mistake is wiping a dry, dusty optic with a tissue or cloth. This is equivalent to cleaning with sandpaper, as abrasive dust particles are ground into the soft optical surface. Always use compressed air or an inert gas to remove loose dust before any physical wiping with solvents occurs [3].

Q3: My optical window has a delicate anti-reflection coating. How can I clean it safely? For optics with delicate coatings, the "immersion" technique is often recommended. Gently remove dust with compressed air, then immerse the window in a reagent-grade solvent like acetone. For heavily soiled items, an ultrasonic bath can be used. Rinse in fresh solvent and blow-dry with a directed stream of air to prevent streaking. Note that this method is not suitable for cemented optics [3].

Q4: What should I do immediately if I suspect a laser exposure incident? Seek immediate medical attention. Staff should contact Occupational Medicine and students should go to Student Health. After hours, all individuals should report to the emergency room. You must also immediately notify your Principal Investigator and the Environmental Health and Radiation Safety (EHRS) office [27].

Troubleshooting Common Optical Window Issues

Problem 1: Blurry or Hazy Appearance After Cleaning

- Possible Cause: Streaking from improper drying or use of non-optical grade solvents.

- Solution: Ensure solvents are reagent- or spectrophotometric-grade. When wiping, use a slow, steady motion to allow for even evaporation and avoid pooling of the solvent. If streaks form, re-clean using a fresh lens tissue with adequate solvent, ensuring the tissue is damp but not dripping [3] [14].

Problem 2: Persistent Dust and Particulates

- Possible Cause: Ineffective initial dust removal or cleaning in a dusty environment.

- Solution: Perform the blowing-off step in a clean, temperature-controlled environment. Use short blasts from a can of inert dusting gas or a blower bulb, holding the nozzle at a grazing angle about 6 inches (15 cm) from the surface. Never use your breath to blow on an optic [14].

Problem 3: Visible Smudges or Fingerprints

- Possible Cause: Handling with bare hands or incomplete removal of skin oils.

- Solution: Always wear powder-free, acetone-impenetrable gloves or use finger cots. For fingerprints, a more thorough cleaning using the "Lens Tissue with Forceps" method may be required. Fold a fresh lens tissue, clamp it with forceps, moisten with an appropriate solvent, and wipe the surface in a continuous motion while slowly rotating the tissue [3] [14].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials required for the safe and effective handling and cleaning of optical windows.

| Item | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| Powder-Free Gloves (Acetone-Impenetrable) | Prevents transfer of skin oils and corrosive sweat to optical surfaces during handling [3]. |

| Compressed Duster Gas or Blower Bulb | Provides a contact-free method for removing loose, dry particulates like dust; the critical first step in cleaning [14]. |

| Lens Tissue (Low-Lint) | Provides a soft, non-abrasive wiping surface. Must be used with solvent and never dry. Never re-use a lens tissue [3]. |

| Reagent-Grade Solvents (Acetone, Methanol, Isopropyl Alcohol) | Dissolves and removes organic contaminants like oils and adhesives. A common effective mixture is 60% acetone and 40% methanol [3] [14]. |

| Cotton-Tipped Applicators or Webril Wipes | Useful for cleaning mounted optics or hard-to-reach areas. Webril wipes are pure cotton and hold solvent well without falling apart [14]. |

| Optical Storage Container | Provides a safe, clean, and low-humidity environment for storing optics, preventing damage and contamination between uses [14]. |

Standardized Cleaning Workflows

Workflow 1: General Cleaning for Most Flat Optical Windows

For flat windows that are unmounted or easily accessible, the "Drop and Drag" method is preferred for its minimal contact with the optical surface.

General Cleaning Workflow for Flat Windows

Protocol Steps:

- Inspect: Hold the optic under a bright light and view from different angles to identify the type and location of contaminants [14].

- Dust Off: Using canned, filtered air or nitrogen, blow off all loose dust from the surface. Hold the can upright and use short blasts at a grazing angle [3] [14].

- Evaluate: If no stains or smudges remain, stop. "If it's not dirty, don't clean it" [3].

- Drop and Drag: Place the optic on a clean, non-abrasive surface. Lay a single, unfolded sheet of lens tissue over it. Drop a small amount of solvent (e.g., acetone-methanol mix) onto the tissue and slowly drag the soaked tissue across the optic's face in one steady motion [3].

- Final Inspection: Inspect the optic again. If contaminants remain, repeat the process with fresh materials.

Workflow 2: Cleaning Small or Mounted Optical Windows

For small-diameter optics or those fixed in a mount, the "Brush" or "Applicator" technique allows for precise control.

Cleaning Workflow for Small/Mounted Windows

Protocol Steps:

- Inspect and Dust: Follow the same initial inspection and dusting steps as in Workflow 1 [14].

- Prepare Applicator: Fold a lens tissue to create a soft "brush" and clamp it with hemostats or tweezers. Alternatively, wrap a lens tissue around a synthetic, low-lint swab [3].

- Apply Solvent: Wet the applicator with an appropriate solvent. Shake off any excess to prevent dripping.

- Wipe: In one continuous motion, "paint" the optical surface, sweeping from one edge to the other. Slowly rotate the applicator during the wipe to present a clean surface to the optic and prevent re-depositing contaminants [3] [14].

Laser Safety and Incident Reporting

When working with lasers, specific safety protocols are mandatory. The table below summarizes laser hazard classifications based on the ANSI Z136.1 standard [27].

| Laser Class | Accessible Output Range (CW) | Primary Hazards | Key Control Measures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 1 | N/A (Not hazardous under normal operation) | Embedded laser may be accessible during service. | Exempt from controls during operation. Service requires LSO approval [27]. |

| Class 2 | Visible, ≤ 1 mW | Eye injury from intentional staring. | Aversion response (blinking) provides protection [27]. |

| Class 3B | 5 - 500 mW | Serious eye injury from direct and specular reflections. | SOPs, training, protective housing, laser safety eyewear [27]. |

| Class 4 | > 500 mW | Serious eye injury (including diffuse reflections), skin burns, fire hazard. | Strict engineering/administrative controls, PPE, designated laser areas, LSO oversight [27]. |

Exposure Incident Protocol: In the event of an exposure to a Class 3B or Class 4 laser beam, you must:

- Seek medical attention immediately (Occupational Medicine for staff, Student Health for students, or the emergency room after hours) [27].

- Notify your Principal Investigator immediately [27].

- Notify the Laser Safety Officer (LSO) or EHRS office immediately [27].

In the field of optical research, particularly in studies focused on maximizing transmittance through optical windows, surface cleanliness is not merely a procedural step but a fundamental determinant of experimental validity. Contaminants including dust, oils, and chemical residues significantly scatter incident light, thereby reducing total transmittance and compromising data accuracy in sensitive applications such as drug development and high-energy laser systems [28]. This technical resource center provides a comparative framework for two predominant cleaning methodologies: the traditional wipe-and-discard technique and ultrasonic cleaning. The following sections offer detailed experimental protocols, troubleshooting guides, and FAQs to support researchers in selecting and optimizing cleaning procedures to achieve superior optical transmittance and minimize surface damage.

The Wipe-and-Discard method is a manual cleaning process that employs soft, low-lint materials like lens tissue saturated with a high-purity solvent, which is used once and then discarded [3] [29]. In contrast, Ultrasonic Cleaning is an automated, immersion-based process that harnesses high-frequency sound waves to generate cavitation bubbles in a liquid solution, which implode to scrub contaminants from surfaces [30] [31].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Cleaning Techniques

| Performance Metric | Wipe-and-Discard | Ultrasonic Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Smallest Particle Removed | 5 µm [29] | 0.1 µm [31] |

| Cleaning Thoroughness | Effective on accessible surfaces; risk of streaking [3] | Excellent for complex geometries and sub-surface contaminants [31] [28] |

| Risk of Surface Damage | Moderate (potential for scratching if done incorrectly) [3] | Low to Moderate (cavitation can roughen some surfaces with incorrect settings) [31] [28] |

| Process Automation | Manual | Automated |

| Typical Cycle Time | Minutes (per piece) | 2 to 10 minutes (per batch) [31] |

| Suitable Substrates | Most mounted and unmounted optics [3] | Glass, most metals, hard plastics, ceramics [32]. Unsuitable for soft, porous materials or some delicate electronics [32]. |

Table 2: Operational and Economic Considerations

| Consideration | Wipe-and-Discard | Ultrasonic Cleaning |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Consumables | Lens tissue, solvents (e.g., acetone, methanol, isopropyl alcohol) [3] | Tank solution (water with specialized detergents) [30] [33] |

| Labor Intensity | High (hands-on per optic) | Low (batch processing) |

| Initial Equipment Cost | Low | Moderate to High |

| Environmental Impact | Solvent disposal concerns [32] | Aqueous solutions are generally greener; lower chemical usage [31] [32] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: The Wipe-and-Discard Technique

This protocol is adapted from standard optical cleaning procedures [3].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Solvent Mixture: Prepare a blend of 60% reagent-grade acetone and 40% reagent-grade methanol. Acetone alone dries too quickly, while methanol slows evaporation for better dissolution of debris [3].

- Lens Tissue: Use a fresh, low-lint tissue designed specifically for optics with each cleaning operation. Reusing tissue can scratch surfaces [3].

Methodology:

- Preparation: Perform all handling in a clean, temperature-controlled environment while wearing powder-free, acetone-impenetrable gloves. Never touch optical surfaces directly [3].

- Dry Removal: Use a canned air duster or filtered nitrogen gas to remove loose abrasive dust from the surface. Wiping a dusty optic is akin to cleaning with sandpaper [3].

- Solvent Application: For an unmounted optic, place it on a clean-room wiper. Lay a single, unfolded lens tissue over the optic and gently drop the solvent mixture onto it until it is damp but not saturated [3].

- Wiping Motion: Using a slow, steady, and continuous motion, drag the soaked tissue across the optic's surface. Wiping slowly prevents streaking and allows for proper solvent evaporation [3].

- Inspection: Hold the optic under a bright, visible-light source and view it from multiple angles to check for any remaining contamination or streaks [3].

- Storage: If not used immediately, wrap the cleaned optic in fresh lens tissue and place it in a dedicated container to prevent contact with other surfaces [3].

Protocol B: Ultrasonic Cleaning Technique

This protocol synthesizes best practices from industrial and laboratory guides [30] [31] [34].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cleaning Solution: Use a specialized, biodegradable ultrasonic cleaning solution (e.g., CLN-SC75, Elma tec clean S2) diluted in deionized or distilled water as specified by the manufacturer. These solutions are formulated to enhance cavitation while being compatible with optical materials [31].

- Rinsing Agent: High-purity isopropyl alcohol or deionized water.

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Fill the ultrasonic tank with the prepared cleaning solution to the recommended level. Avoid overfilling or underfilling [31].

- Component Loading: Place optics in a dedicated basket or rack, ensuring they do not touch each other or the tank walls. Overlapping creates "shadow zones" with reduced cleaning effectiveness [34].

- Parameter Selection: Set the ultrasonic frequency based on the delicacy of the optic. Use lower frequencies (e.g., 25-40 kHz) for robust contamination and higher frequencies (e.g., 80-200 kHz) for delicate surfaces or fine particles [31] [34]. Set the temperature to 50-60°C if compatible with the material, as heat generally improves cleaning efficacy [33].

- Degassing: Run the ultrasonic tank for 5-10 minutes without the load to remove dissolved air from the fresh solution, which improves cavitation efficiency [33].

- Cleaning Cycle: Immerse the loaded basket and run the ultrasonic cycle for 2 to 10 minutes, depending on the level of soiling [31].

- Post-Cleaning Rinse and Dry: Rinse the optics thoroughly with a clean rinsing agent to remove any residual cleaning solution. Carefully blow-dry with filtered air or nitrogen to prevent water spots [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Optical Cleaning

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Lens Tissue | Low-lint, high-quality paper; provides a soft, abrasive-free medium for physically wiping contaminants without scratching delicate surfaces [3]. |

| Reagent-Grade Solvents (Acetone, Methanol, IPA) | High-purity organic solvents dissolve and lift organic residues like oils and fingerprints from optical surfaces without leaving impurities [3]. |

| Specialized Ultrasonic Cleaning Solution | Aqueous solutions containing surfactants and detergents that lower surface tension, enhancing the cavitation process and improving contaminant removal [30] [31]. |

| Canned Air Duster / Filtered Nitrogen Gas | Provides a stream of particle-free gas for the non-contact removal of loose dust and debris as a critical first step in cleaning [3]. |

| Powder-Free Gloves (Acetone-Impenetrable) | Prevents contamination of pristine optical surfaces with corrosive salts and oils from human hands [3]. |

Decision Framework and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting and applying the appropriate cleaning technique within an experimental workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Ultrasonic Cleaning Troubleshooting

Table 4: Common Ultrasonic Cleaning Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Cleaning Performance [34] [33] | Incorrect frequency; Incorrect or degraded cleaning solution; Air bubbles in fresh solution; Incorrect loading. | Select higher frequency for delicate parts, lower for stubborn soil [34]. Replace with fresh, compatible solution [33]. Let solution degas for 5-10 mins before loading [33]. Ensure parts are spaced and not overlapping [34]. |

| No Cavitation [33] | Faulty transducer or generator; Tank not filled. | Perform the "aluminum foil test": suspend a strip in the tank for 30 seconds. Uniform pitting confirms cavitation [33]. |

| Surface Damage After Cleaning [31] [28] | Excessively aggressive parameters; Material incompatibility. | Lower power and/or use a higher frequency for delicate optics [31] [34]. Verify material compatibility with the cleaning solution [32]. |

| Machine Won't Turn On [33] | Power issues; Blown fuse. | Check outlet and power cord. Replace fuse if accessible [33]. |

Wipe-and-Discard Troubleshooting

Table 5: Common Wipe-and-Discard Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Verification Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Streaks on Surface [3] | Solvent drying too fast; Incorrect wiping technique. | Use a 60/40 acetone-methanol blend to slow evaporation [3]. Use a slow, continuous dragging motion instead of circular scrubbing [3]. |

| Scratches on Surface [3] | Wiping a dusty surface; Reusing lens tissue. | Always use compressed air or nitrogen to blow off loose dust before wiping [3]. Use a fresh, unused lens tissue for every cleaning operation [3]. |

| Residual Haze or Film [3] | Low-purity solvents; Skin contact with optical surface. | Use only reagent-grade or spectrophotometric-grade solvents [3]. Handle optics exclusively with gloves and by the edges [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Can ultrasonic cleaning damage the anti-reflective (AR) coatings on optical windows? A: Potentially, yes. The laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) of optical components with sub-wavelength structures (like some AR coatings) can be limited by surface and subsurface contaminants introduced during fabrication. While ultrasonic cleaning can effectively remove these contaminants and improve the LIDT, the process parameters must be carefully controlled. Overly aggressive cleaning can modify the nano-structures or leave a re-deposition layer, which can be detrimental to performance [28].

Q2: For a high-throughput drug development lab, which method is more cost-effective? A: While the wipe-and-discard method has a lower initial cost, ultrasonic cleaning is generally more cost-effective for high-throughput environments. The significant reduction in labor time, consistency of automated batch processing, and reduced consumable costs (replacing solvents and tissues with aqueous solutions) lead to lower operational costs and higher efficiency over time [31] [32].

Q3: Is it safe to clean all types of glass in an ultrasonic cleaner? A: Ultrasonic cleaning is safe for most types of glass, including borosilicate and fused silica [32]. However, it is not recommended for thin, fragile glass, glass with coatings of unknown durability, or glass that is already chipped or cracked, as the stress from cavitation could propagate the damage [32]. Always verify material compatibility and start with less aggressive settings.

Q4: What is the single most critical step in the wipe-and-discard method to prevent damage? A: The most critical step is the initial removal of loose particulate matter using clean, compressed air or nitrogen. Wiping a surface that still has dust or grit acts as a grinding process and will almost certainly scratch and permanently damage the optical surface [3].

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a specialized cleaning protocol necessary for optical windows? A specialized protocol is critical because general cleaning methods can leave behind residues, scratches, or static charge that significantly degrade optical performance. Contaminants like dust, oils, and leftover cleaning solvents can scatter or absorb light, directly reducing transmittance—a key metric in optical research. Proper cleaning protects sensitive coatings and ensures consistent, reliable experimental results by maintaining the integrity of the optical surface [9] [35].

Q2: What are the consequences of using non-optical-grade wipes? Using non-specialized wipes can lead to several issues:

- Scratches: Abrasive materials can permanently damage delicate optical surfaces [36].

- Lint and Fibers: Non-optical wipes can shed lint, leaving behind particulates that obstruct the light path [35].

- Chemical Residue: Wipes with high solvent extractables or chemical additives can leave a film on the optic, which directly impacts transmittance measurements by altering the surface's interaction with light [36] [37].

Q3: How does static electricity affect cleaned optics, and how can it be mitigated? Static charge on a cleaned optical surface can attract airborne dust particles, leading to rapid re-contamination. This is a known phenomenon with some polymer-based cleaning films [35]. To mitigate this, ensure your cleaning is performed in an environment with controlled humidity and consider using anti-static solutions or guns. Grounding the optic, if possible, can also help dissipate charge [35].

Q4: What is the recommended frequency for cleaning and replacing protection windows? For laser protection windows, a daily maintenance routine is recommended, involving inspection and cleaning before and after operation [9]. The lifetime of a component can vary, but with diligent daily cleaning, protection windows can last from six months to a year [9]. Always replace the window if you observe visible burn marks, permanent discoloration, or a consistent drop in system power [9].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Problem: Streaks or Haze on Optical Surface After Cleaning

- Potential Cause 1: Use of a dirty wipe or reusing a wipe. Always use a fresh, clean optical wipe for each cleaning pass.

- Potential Cause 2: The cleaning solvent is evaporating too quickly, re-depositing dissolved contaminants. Try a different solvent blend or apply the solvent to the wipe, not directly onto the optic, for better control.

- Potential Cause 3: Incompatible solvent. Ensure the solvent is appropriate for the optical coating and any adhesives present.

Problem: Consistent Scratches on Multiple Optics

- Potential Cause 1: The wipes themselves are abrasive. Switch to a wipe specified as "soft and non-abrasive for delicate optical surfaces" [36], such as pure cellulose or hydroentangled polyester/cellulose blends [37].

- Potential Cause 2: Improper technique. Avoid excessive pressure. Use a light touch and drag the wipe across the surface in a single, straight motion rather than small circles.

Problem: Noticeable Drop in Transmittance or Laser Power

- Potential Cause 1: A dirty or damaged protection window. Check the window for debris buildup, burn marks, or discoloration and clean or replace it as needed [9].

- Potential Cause 2: Invisible residue from cleaning agents. This underscores the need for wipes with low solvent extractable levels to minimize nonvolatile residue [36]. Re-clean the optic using a high-purity solvent.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials for implementing a reliable optical cleaning protocol.

Table 1: Essential Materials for Optical Cleaning Protocols

| Item | Function & Key Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Absorbond Cleanroom Wipes [36] | Designed for cleanroom use; soft, non-abrasive, and feature low solvent extractable levels to minimize residue left on sensitive optical surfaces. |

| Durx 570 Wipes [37] | Hydroentangled nonwoven wipes made from a 55% cellulose / 45% polyester blend; low in extractable levels and particulates, suitable for controlled environments. |

| Webril Handi-Pads [35] | Pure cotton, non-woven, low-lint pads that are free from contaminants and adhesives; ideal for use with optics cleaning solvents. |

| Lens Cleaning Tissues [35] | Extremely soft, premium-grade sheets that are free from contaminants and adhesives; will not leave lint or fibers on the optic. |

| Solvent Dispenser Bottles [35] | One-touch pump dispensers minimize solvent evaporation and contamination when cleaning optics, ensuring solvent purity. |

Experimental Protocol for Validating Cleaning Efficacy

This protocol is designed to quantitatively assess the effectiveness of different cleaning methods on the transmittance of optical windows.

Objective

To evaluate and compare the transmittance of optical windows cleaned with different combinations of optical-grade wipes and alcohol-based solvents, ensuring the cleaning process itself does not degrade optical performance.

Materials and Equipment

- Optical Windows: Multiple samples of the same material and coating.

- Cleaning Materials: Selected wipes and solvents from Table 1.

- Contamination Simulant: A standardized contaminant (e.g., fingerprint oil, dust particulates).

- Measurement Instrument: A spectrophotometer with a transmittance measurement accessory, such as an integrating sphere for accurate diffuse and total transmittance measurement [38] [39].

- Controlled Environment: A clean bench or laminar flow hood to prevent airborne contamination during cleaning and measurement.

Methodology

- Baseline Measurement: Measure and record the initial transmittance spectrum (e.g., across 400-700 nm) of each pristine optical window to establish a baseline [39].

- Contamination: Apply a controlled, consistent amount of contamination simulant to each window sample.

- Cleaning Test: Divide the contaminated windows into groups. Each group will be cleaned using a specific protocol (e.g., Wipe A with Solvent X, Wipe B with Solvent Y). Use a consistent, documented wiping technique.

- Post-Cleaning Measurement: After cleaning and allowing the solvent to fully evaporate, measure the transmittance spectrum of each window again under the same conditions as the baseline.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage transmittance recovery for each sample:

(Post-Cleaning Transmittance / Baseline Transmittance) * 100%.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The results from the experiment should be compiled into a summary table for clear comparison.

Table 2: Example Transmittance Recovery Data for Various Cleaning Protocols

| Cleaning Protocol (Wipe + Solvent) | Average Transmittance Recovery (%) at 550 nm | Standard Deviation (%) | Visible Residue or Damage (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleanroom Wipe + Isopropanol | 99.5 | 0.3 | N |

| Lens Tissue + Acetone | 98.8 | 0.5 | N |

| Non-woven Pad + Methanol | 95.2 | 1.1 | Y (slight haze) |

| Uncleaned (Contaminated Control) | 85.0 | 2.5 | Y |

The experimental workflow for this validation protocol is outlined below.

Experimental Workflow for Cleaning Validation

Ion-Assisted Deposition (IAD) is an advanced thin-film coating technology that combines traditional electron beam (e-beam) evaporation with simultaneous bombardment of the growing film by a beam of ions [40]. This process fundamentally enhances the microstructure and macroscopic properties of optical coatings, making them denser, harder, and more durable compared to those produced by conventional evaporation [41].

Within research focused on optimizing transmittance through cleaned optical windows, IAD plays a crucial role. The quality and durability of the anti-reflection (AR) or other functional coatings applied to these windows directly impact their long-term optical performance and reliability in demanding environments, such as high-power laser systems or supersonic combustion facilities [42] [43]. Achieving and maintaining high transmittance requires coatings that are not only optically precise but also environmentally stable and resistant to degradation.

Core Principles of IAD

The IAD Process Workflow

The IAD technique modifies standard e-beam evaporation by introducing a separate ion source that directs energetic ions (typically argon or oxygen) toward the substrate during film deposition [40]. The ion bombardment provides additional energy to the adatoms on the substrate surface, leading to a more compact atomic arrangement and the disruption of columnar microstructures common in evaporated films [40] [44]. This results in coatings with increased density, improved adhesion, reduced intrinsic stress, and enhanced environmental stability [41].

IAD System Configuration

Diagram 1: IAD System Setup. This diagram illustrates the key components of an IAD coating system, including the ion source for bombardment and the e-beam gun for material evaporation, which work in concert within a vacuum chamber to produce dense, high-quality thin films.

A typical IAD setup is based on a standard e-beam evaporation system but is augmented with a broad-beam ion source [40]. As shown in Diagram 1, the system includes:

- Vacuum Chamber: Provides a clean, controlled environment for the coating process.

- Electron Beam Gun: Focuses a high-energy electron beam to heat and vaporize the target material.

- Ion Source: Generates a stream of ions which are accelerated toward the substrate by high voltage or magnetic fields [40].

- Substrate Holder: Holds the optical components to be coated, often with heating capabilities.

- Gas Inlet: Introduces reactive gases like oxygen for oxide coatings or argon for inert bombardment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I choose IAD over standard e-beam evaporation or Ion Beam Sputtering (IBS) for my optical windows?

IAD offers a unique balance between coating performance, cost, and throughput. Compared to standard e-beam evaporation, IAD produces significantly denser and more durable films with better moisture resistance and lower scatter [41]. This is crucial for maintaining high transmittance and laser damage threshold in optical windows. Versus IBS, IAD generally provides a higher deposition rate and lower cost of ownership, making it suitable for a wider range of component sizes and production volumes, though IBS may achieve superior film quality in some high-end applications [41] [42].

Q2: How does IAD improve the laser damage threshold of coatings on optical windows?

The ion bombardment during IAD increases the packing density of the coating, eliminating microscopic voids and columnar structures that can act as absorption centers and initiate laser-induced damage [40]. Denser films also exhibit higher thermal conductivity, which helps dissipate heat more effectively during high-power laser exposure [42]. Furthermore, IAD allows for precise control over film stoichiometry, reducing point defects that contribute to absorption [40].

Q3: Can IAD be used to coat temperature-sensitive substrates?

Yes. A significant advantage of IAD is that it does not require high substrate temperatures to achieve dense films. The energy for densification comes from the ion beam, not external heating [41]. This makes IAD suitable for coating plastic materials, such as polycarbonate lenses, and other substrates that cannot withstand high temperatures [41].

Q4: What is the impact of ion energy on the properties of HfO₂ films, a common high-index material?