Optimizing Sample Preparation for Spectroscopic Analysis in 2025: A Foundational Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sample preparation to ensure accurate and reliable spectroscopic results.

Optimizing Sample Preparation for Spectroscopic Analysis in 2025: A Foundational Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing sample preparation to ensure accurate and reliable spectroscopic results. It covers the foundational principles of why sample preparation is critical, detailing how inadequate methods account for nearly 60% of analytical errors. The scope includes methodological approaches for various techniques (XRF, ICP-MS, FT-IR), practical troubleshooting strategies to overcome common pitfalls, and a comparative analysis of different preparation methods to guide selection and validation. By synthesizing the latest trends, such as automation and miniaturization, this article serves as an essential resource for improving data integrity in biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Foundations: Why Sample Preparation is the Cornerstone of Reliable Spectroscopic Data

Inaccurate sample preparation is the leading cause of analytical errors in spectroscopy, contributing to as much as 60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [1]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals overcome common sample preparation challenges and optimize their spectroscopic analyses.

The substantial impact of poor sample preparation stems from multiple interconnected factors that compromise analytical integrity. The table below summarizes the primary sources of error and their effects on spectroscopic data.

| Error Source | Impact on Analysis | Common Techniques Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Heterogeneity [1] [2] | Non-representative sampling leads to non-reproducible results. | All, especially XRF, ICP-MS |

| Particle Size Variation [1] [3] | Causes light scattering and sampling error; compromises quantitative analysis. | XRF, FT-IR, Raman |

| Contamination [1] [4] | Introduces spurious spectral signals, making results worthless. | ICP-MS, AAS, Trace analysis |

| Matrix Effects [1] [4] | Matrix constituents obscure or enhance the analyte's spectral signal. | ICP-MS, UV-Vis |

| Incorrect Calibration [5] [2] | Using an incorrect or unvalidated calibration model leads to inaccurate quantification. | All quantitative methods |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My XRF pressed pellets give precise but inaccurate results. What is the cause?

This common issue typically stems from a mineralogical or particle size effect [3]. Your preparation method may yield high precision (repeatable results), but accuracy suffers because your pressed powder standards and unknowns differ in fundamental characteristics.

- Root Cause: The "Pressed Powder Method" is susceptible to the mineralogical effect, where different minerals with the same chemical composition yield different spectral intensities due to their crystal structure [3]. Even with identical particle sizes, this effect can cause analytical totals to range from 75% to 125% [3].

- Solution: For the highest accuracy, switch to the fusion method. Fusion dissolves the crystal structure of your samples and standards into a homogeneous glass disk, effectively eliminating the mineralogical effect and creating a uniform matrix for analysis [1] [3].

Q2: My ICP-MS results show high background and erratic signals. What should I troubleshoot?

This points to issues with your liquid sample preparation. Focus on dissolution, dilution, and filtration protocols [1].

- Root Cause: Incomplete dissolution of solid samples or inadequate filtration can allow particulates to reach the plasma and nebulizer, causing signal instability and blockages. Contamination from reagents, labware, or the environment can also elevate background levels [1] [4].

- Solution:

- Ensure complete digestion of your samples using appropriate acids or microwave-assisted digestion [4].

- Filter your final solutions using a 0.45 μm membrane filter (or 0.2 μm for ultra-trace analysis) to remove any suspended particles [1].

- Use high-purity reagents and dedicate labware to prevent contamination. Acidification with high-purity nitric acid (to 2% v/v) can help keep analytes in solution [1].

Q3: How can I ensure my sub-sample is representative of the bulk material?

Representative sampling is the first and one of the most critical steps. Failure here makes all subsequent preparation and analysis meaningless [2] [6].

- Root Cause: Most materials are inherently heterogeneous. Simply scooping a sample from the top of a container can lead to severe segregation bias, as finer and denser particles tend to settle at the bottom [6]. One study showed that random scoop sampling from the same material led to variations of up to 20% in sieve analysis results [6].

- Solution:

- Follow the "Golden Rule for Accuracy": The closer your standards are to the unknowns in mineralogy, particle size, and matrix, the more accurate your analysis will be [3].

- Collect multiple sub-samples from different locations in the bulk material (top, middle, bottom, inner, outer) and combine them [6].

- Use mechanical sample dividers (e.g., rotary tube dividers) instead of manual sampling to achieve the highest degree of reproducibility and the smallest qualitative error [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Systematic Approach to Sample Preparation Issues

Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and resolve common sample preparation problems.

Guide 2: Sample Preparation Protocols for Key spectroscopic Techniques

Adhere to these detailed methodologies to ensure accurate and reproducible results.

Protocol 1: Solid Sample Preparation for XRF Analysis (Pressed Pellet Method)

This protocol is designed to create homogeneous, flat pellets with uniform density for quantitative XRF analysis [1] [3].

- Step 1: Representative Sampling: Obtain a representative sub-sample of the bulk material using a mechanical sample divider to avoid segregation bias [6].

- Step 2: Drying (if required): Dry moist samples (e.g., leaves, soils) at room temperature or using a gentle fluidized bed dryer to avoid altering sample properties. Do not use high heat for volatile components [6].

- Step 3: Grinding/Homogenization:

- Step 4: Pelletizing:

- Step 5: Storage and Handling: Store pellets in a desiccator. Avoid touching the analytical surface, as the effective layer thickness for light elements can be as little as 4-10 µm [3].

Protocol 2: Liquid Sample Preparation for ICP-MS Analysis

This protocol ensures complete dissolution, proper dilution, and removal of interferences for the high-sensitivity technique of ICP-MS [1] [4].

- Step 1: Digestion/Dissolution (for solids):

- Use acid digestion (e.g., with HNO₃) or microwave-assisted digestion to completely break down the sample matrix and bring analytes into solution [4].

- Step 2: Dilution:

- Accurately dilute the sample to bring analyte concentrations within the instrument's optimal calibration range.

- High total dissolved solids (TDS) samples may require significant dilution (e.g., 1:1000) to prevent matrix effects and instrument damage [1].

- Step 3: Filtration:

- Pass the diluted solution through a 0.45 μm membrane filter (e.g., PTFE) to remove any suspended particles that could clog the nebulizer. Use 0.2 μm for ultra-trace analysis [1].

- Step 4: Acidification and Internal Standardization:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key materials and their functions for reliable spectroscopic sample preparation.

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Tetraborate (Li₂B₄O₇) | Flux for fusion preparation of XRF samples; creates homogeneous glass disks [1]. | Excellent for silicates, minerals, and ceramics. Totally eliminates mineralogical effects [3]. |

| Boric Acid / Cellulose | Binder for pressed powder pellets in XRF; provides structural integrity [1] [3]. | Acts as a backing agent. Remember to account for dilution when calculating final concentrations [1]. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Digestant for metal analysis and acidifying agent for ICP-MS samples [1] [4]. | "High-purity" or "trace metal" grade is essential to prevent contamination of sensitive analyses [1]. |

| PTFE Membrane Filter (0.45/0.2 μm) | Removes particulate matter from liquid samples for ICP-MS [1]. | Prevents nebulizer clogging and introduction of particles into the plasma. PTFE is chemically inert [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validate analytical methods and ensure accuracy by providing a known benchmark [4]. | Critical for quality control. The standard's matrix should match your unknowns as closely as possible [3]. |

| Internal Standards (e.g., In, Sc) | Added to samples in ICP-MS to correct for instrument drift and matrix suppression/enhancement [1] [4]. | Improves quantitative accuracy. The internal standard should not be present in the original sample and should have similar behavior to the analyte [4]. |

Why is Sample Preparation Critical for Spectroscopic Analysis?

Sample preparation is a foundational step in spectroscopic analysis. Inadequate sample preparation is the cause of as much as 60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [1]. The quality of preparation directly determines the validity and accuracy of your results by controlling three key principles:

- Homogeneity: Ensuring the analyzed sample portion is representative of the whole [1].

- Contamination: Preventing the introduction of external substances that can cause false positives or elevated baselines [7] [8].

- Matrix Effects: Managing the influence of the sample's base composition on the analyte signal [1] [9].

Proper techniques are crucial for collecting reliable data, maintaining quality control, and drawing accurate analytical conclusions [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Homogeneity Issues

Problem: Non-reproducible results from non-representative sampling.

| Common Problem & Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Solid samples are heterogeneous [1]. | Grinding/Milling: Use spectroscopic grinding or milling machines to reduce particle size. Aim for particles <75 μm for techniques like XRF. Grind under identical time and pressure for consistency [1]. |

| Powdered samples segregate or do not form uniform pellets. | Pelletizing/Briquetting: Mix the ground powder with a binding agent (e.g., wax or cellulose) and press using a hydraulic press (10-30 tons) to create a solid, uniform disk for analysis [1]. |

| Liquid samples are not uniform. | Homogenization & Agitation: Use mechanical homogenization (e.g., rotor-stator) for biological tissues or viscous liquids. For solutions, ensure thorough mixing or shaking before sampling [4]. |

Contamination Issues

Problem: Falsely elevated results or false positives from introduced contaminants.

| Common Problem & Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Background contamination from labware (e.g., beakers, vials, pipettes). [7] [8] | Avoid Glass: Use high-purity plastic labware (polypropylene (PP), fluoropolymers (PFA, FEP)) for trace metal analysis. Glass can leach metals like sodium, boron, and aluminum into acidic solutions [7] [8]. |

| Contamination from laboratory environment (airborne dust, skin, gloves). [7] [8] | Control the Environment: Work in a HEPA-filtered laminar flow hood if possible. Use powder-free nitrile gloves. Avoid touching the inside of containers or pipette tips. Do not use pipettes with external stainless-steel tip ejectors, which can introduce metals [7] [8]. |

| Impurities from reagents (acids, water, solvents). [8] [10] | Use High-Purity Reagents: Use ultra-high purity acids (double-distilled in PFA or quartz) and 18 MΩ.cm deionized water. For solvents, select the appropriate grade (e.g., HPLC grade, Spectrophotometric grade) for your application [8] [10]. |

Matrix Effects Issues

Problem: The sample base composition suppresses or enhances the analyte signal, leading to inaccurate quantification.

| Common Problem & Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|

| Sample matrix causes spectral interferences or non-linear response. [1] [9] | Sample Dilution: Dilute the sample to bring the analyte concentration into a linear range and reduce the overall matrix concentration. Calibration with Matrix-Matching: Prepare calibration standards in a matrix that closely matches the sample's composition [1] [9]. |

| Complex or refractory materials (e.g., silicates, ceramics) are not fully dissolved. [1] | Fusion: For complete dissolution, fuse the sample with a flux (e.g., lithium tetraborate) at high temperatures (950-1200°C) to create a homogeneous glass disk. This destroys the original crystal structure and eliminates mineralogical effects [1]. |

| Biological or organic matrices interfere with inorganic analysis. [4] | Acid Digestion: Use microwave-assisted acid digestion with nitric acid to completely break down and dissolve organic materials before analysis by ICP-MS [4]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Pellet Preparation for XRF Analysis

This protocol is for creating a homogeneous, solid pellet from a powdered sample for X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) analysis [1].

- Grinding: Use a swing grinding machine to reduce the solid sample to a fine powder with a particle size ideally below 75 μm.

- Mixing: Weigh out a specific amount of the ground powder (e.g., 4-5 g). Mix it thoroughly with a binder like cellulose or boric acid (~5-10% by weight) in a vial or mixing vessel.

- Loading: Transfer the mixture into a specialized pellet die, ensuring it is spread evenly.

- Pressing: Place the die in a hydraulic press and apply pressure between 10 and 30 tons for 30-60 seconds.

- Ejection & Storage: Carefully eject the resulting solid pellet. Store it in a desiccator to prevent moisture absorption before analysis.

Quantitative Data on Preparation Errors

| Error Source | Impact on Analysis | Quantitative Data / Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| General Preparation Errors | Lead to invalid or inaccurate analytical findings [1]. | Inadequate preparation is responsible for ~60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [1]. |

| Particle Size (XRF) | Influences X-ray scattering and absorption, affecting quantitative accuracy [1]. | Particle size should typically be reduced to <75 μm for accurate analysis [1]. |

| Contamination (ICP-MS) | Increases background, causes false positives, and raises detection limits [7] [8]. | Use labware and acids rated for sub-ppt (ng/L) trace element analysis. Pre-rinse all plasticware with dilute, high-purity acid [8]. |

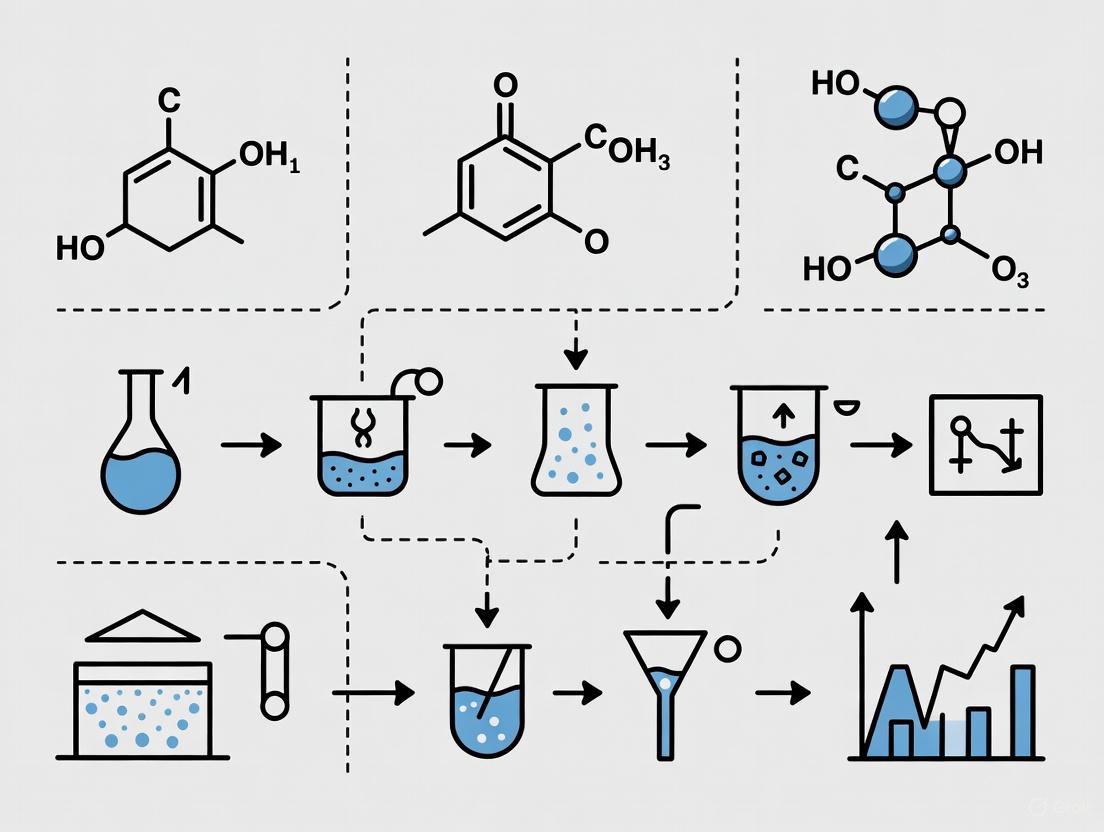

Essential Diagrams & Workflows

Sample Preparation Quality Control Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃) | Essential for digesting and dissolving samples for ICP-MS. Must be ultra-high purity (double-distilled in PFA/quartz) to prevent contamination [7] [8]. |

| Binders (Cellulose, Boric Acid) | Mixed with powdered samples to create cohesive pellets for XRF analysis, ensuring uniform density and surface [1]. |

| Internal Standard Solution | Added to samples and standards in ICP-MS to correct for instrument drift and matrix-induced signal suppression/enhancement [4]. |

| Flux (Lithium Tetraborate) | Used in fusion techniques to dissolve refractory materials at high temperatures, creating a homogeneous glass disk for accurate XRF analysis [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Materials with a certified composition used to validate analytical methods, ensure accuracy, and calibrate instruments [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: I am analyzing trace metals in a biological fluid using ICP-MS. My procedural blanks show high levels of chromium and nickel. What is the most likely source? The most probable source is contamination from pipettes with external stainless-steel tip ejectors [7]. Stainless steel contains chromium and nickel, which can be easily transferred to your samples. Remove the ejector and remove tips manually, or use pipette models without exposed metal ejectors [7].

Q2: My UV-Vis calibration curve is non-linear at higher concentrations. Is this a preparation issue? Yes, this is a classic concentration effect and a deviation from the Beer-Lambert law. It can be caused by intermolecular interactions or instrumental limitations at high absorbance [9]. The solution is to dilute your samples to bring them into the linear range of your calibration curve [9].

Q3: For FT-IR analysis, when should I use the ATR technique versus making a KBr pellet? ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) is the modern, first-choice method for most solids and liquids. It requires minimal preparation—you simply press the sample against the crystal. KBr pellet transmission is an older technique that is useful for creating very thin, transparent samples but requires careful grinding and pressing and is more prone to moisture effects [11].

Q4: Why should I avoid glassware for trace metal analysis, even if it looks clean? Glass is a significant source of metallic contaminants. Acidic or alkaline solutions will leach elements like sodium, boron, aluminum, and calcium from the glass silicate matrix into your sample, leading to falsely elevated results [7] [8]. Always use high-purity plastic labware (e.g., PP, PFA) for trace element work.

XRF Analysis: Troubleshooting and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is sample preparation so critical for accurate XRF analysis? XRF is a surface-sensitive technique. The primary X-ray beam interacts with only a very shallow layer of the sample. Imperfections on the surface, such as roughness, cracks, or porosity, can create inconsistencies in the distance to the detector, significantly altering the intensity of the measured fluorescent X-rays and leading to major analytical errors. A perfectly homogeneous and representative surface is the most critical factor for achieving accurate and repeatable results [12].

Q2: What are the most common errors in XRF sample preparation? The most prevalent pitfalls include:

- Insufficient Grinding: Failure to reduce the sample to a fine, uniform powder (ideally <75 µm) introduces particle size and mineralogical effects, making the sample non-representative [12] [13].

- Contamination: Using grinding vessels made of materials like tungsten carbide can introduce contaminating elements (e.g., tungsten) into the sample [14] [12].

- Poor Pellet Integrity: Applying insufficient pressure or using an incorrect binder ratio results in fragile pellets that crack or crumble. Any surface imperfection compromises analysis [12].

Q3: How does the pressed pellet method improve results? The pressed pellet method directly addresses the core challenges of XRF analysis by grinding the sample to eliminate particle size and mineralogical effects, and then pressing it into a dense, flat pellet with a perfectly smooth surface. This process ensures the analyzed volume is representative of the entire sample, leading to highly accurate and repeatable quantitative results [14] [12].

XRF Troubleshooting Guide

The table below outlines common XRF problems and their solutions.

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Repeatability | Large, non-uniform particles [14] [13] | Grind sample to fine powder (<75 µm) [12] |

| Low Result Accuracy | Contamination from grinding vessel [14] | Use grinding mills of material free of analytes of interest [12] |

| Weak or Crumbling Pellets | Insufficient pressure or incorrect binder ratio [12] | Press at 20-30 tons; use binder at 5-10% of sample weight [14] [12] |

| Spectral Interferences | Overlapping element signals [13] | Use instrument software for spectral deconvolution or a high-resolution detector [13] |

Optimal Workflow for XRF Sample Preparation

The following diagram illustrates the standardized workflow for preparing high-quality pressed pellets for XRF analysis.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for XRF

The table below lists key materials required for the XRF pressed pellet method.

| Item | Function | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Mill | Reduces sample to a fine, homogeneous powder [12]. | Material must avoid contaminating analytes (e.g., Agate for trace metals) [14]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Compresses powder into a solid, flat pellet [12]. | Capable of applying 20-30 tons of pressure [12]. |

| Binder / Backing Material | Provides structural integrity to the pellet [14]. | Chemically pure, low X-ray absorption (e.g., cellulose, wax) [14] [12]. |

| XRF Pellet Die | Holds the powder during the pressing process [14]. | Creates pellets of consistent diameter and thickness [12]. |

ICP-MS Analysis: Troubleshooting and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the fundamental sample requirements for liquid analysis by ICP-MS? Samples must be in a liquid form and introduced as an aerosol. For robust analysis, the liquid should typically be in an aqueous matrix (e.g., 2% nitric acid) and have a Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) level below ~0.5%. Higher TDS levels can cause the solids to precipitate in the nebulizer or overload the plasma, leading to signal drift and data collection issues [15].

Q2: How are solid samples prepared for ICP-MS? Solid samples are typically digested using strong, hot acids. The acid choice depends on the matrix:

- Simple Matrices: Nitric acid often suffices [15].

- Silicates/Sols: Hydrofluoric acid (HF) is required [15].

- Organic Matter: Hydrogen peroxide may be added to break down organics efficiently [15].

Q3: What is a common issue with organic liquid samples and how is it resolved? Analyzing organic liquids can lead to carbon buildup (carbon deposition) on the instrument cones and interface, causing signal drift. This is mitigated by using a specialized setup: a smaller injector, platinum-tipped cones, and adding oxygen to the plasma to combust the carbon [15].

ICP-MS Troubleshooting Guide

The table below summarizes common ICP-MS challenges and corrective actions.

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Drift | High Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) overloading plasma [15] | Dilute sample; ensure TDS <0.5%; use specialized nebulizer [15] |

| Carbon Deposition | Analysis of organic solvents [15] | Use O₂ in plasma; fit Pt-tipped cones & smaller injector [15] |

| Low Sensitivity/Blockage | Precipitation of dissolved solids in nebulizer [15] | Dilute sample; use matrix-matching & internal standards [15] |

This diagram maps the primary routes for introducing different sample types into the ICP-MS plasma.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ICP-MS

| Item | Function | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids | Digest and dissolve solid samples into a liquid matrix [15]. | Trace metal grade (e.g., HNO₃, HCl, HF) to minimize background contamination [15]. |

| Internal Standards | Correct for signal variation from viscosity, matrix effects, and instrument drift [15]. | Elements not present in sample (e.g., Sc, Ge, In, Bi); added to all samples and calibrants [15]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Validate the entire analytical method, from digestion to analysis [15]. | Matrix-matched to the samples being analyzed. |

FT-IR Analysis: Troubleshooting and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why do I see strange negative peaks in my ATR-FTIR spectrum? This is a classic sign of a dirty ATR crystal. The negative peaks indicate that the background scan was collected with a contaminated crystal. When you then place your sample and run the scan, the instrument detects that certain energies are less absorbed than in the "dirty" background, resulting in negative absorbance. The fix is simple: clean the ATR crystal thoroughly with an appropriate solvent, collect a new background spectrum, and then re-analyze your sample [16] [17].

Q2: My FT-IR spectrum looks noisy or has unusual spikes. What could be wrong? Instrument vibrations are a common culprit. FT-IR spectrometers are highly sensitive to physical disturbances from nearby equipment (e.g., pumps, chillers) or even general lab activity. These vibrations can introduce false features and spikes into the spectrum. Ensure the instrument is on a stable, vibration-free bench. Additionally, ensure the instrument's optical components are clean and that the instrument is properly purged to eliminate spectral contributions from atmospheric CO₂ and water vapor [16] [17].

Q3: Why does the spectrum from the surface of my plastic sample look different from a freshly cut interior piece? This highlights the difference between surface and bulk chemistry. ATR is a surface-sensitive technique. The surface of a material can have a different composition due to factors like oxidation, additive migration (e.g., plasticizers moving to or from the surface), or contamination. The spectrum from the interior represents the bulk material. For accurate bulk analysis, it is often necessary to cut the sample to expose a fresh interior surface [16] [17].

FT-IR Troubleshooting Guide

The table below addresses common FT-IR issues, particularly with ATR accessories.

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Negative Absorbance Peaks | Dirty ATR crystal during background scan [16] [17] | Clean crystal; collect fresh background [16] |

| Noisy Spectra / Strange Features | Instrument vibration or malfunction [16] [17] | Isolate instrument from vibrations; check instrument health [16] |

| Surface vs. Bulk Discrepancy | ATR measuring surface chemistry not representative of bulk [16] [17] | Analyze a freshly cut interior surface of the sample [16] |

| Distorted Diffuse Reflection Spectra | Data processed in absorbance units [16] [17] | Convert spectrum to Kubelka-Munk units for accurate analysis [16] |

FT-IR ATR Troubleshooting Decision Tree

Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and resolve the most frequent FT-IR ATR issues.

Advanced Methodologies: Tailoring Sample Preparation Techniques for Specific Spectroscopic Applications

In spectroscopic analysis research, the accuracy of X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) results is fundamentally dependent on the quality of sample preparation [18]. A poorly prepared sample introduces significant analytical errors, undermining the validity of experimental data [3]. For solid samples, techniques such as grinding, milling, pelletizing, and fusion are critical for minimizing matrix effects, particle size bias, and mineralogical interferences [18] [14]. This guide provides detailed troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers and scientists aiming to optimize these preparation steps, thereby ensuring the generation of reliable and reproducible elemental composition data.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Crumbling Pellets | Insufficient binder [19] [14]; Incorrect pressure [19]; Particle size too large [19] | Optimize binder concentration (5-10% sample weight) [14]; Increase pressing pressure (25-35 tonnes) [19]; Ensure particle size is <75µm [19] |

| Inhomogeneous Analysis | Incomplete grinding [14]; Poor sample mixing [18]; Improper subsampling [18] | Grind to fine powder (<50µm ideal) [19]; Use automated rotary sample dividers [18]; Extend grinding time until analysis stabilizes [14] |

| Contaminated Sample | Contaminated grinding vessels or media [19] [14]; Dirty pressing dies [19] | Select compatible grinding media (e.g., Tungsten Carbide, Agate) [18] [14]; Clean dies and vessels thoroughly between samples [19] [14] |

| Mineralogical Effects | Presence of different crystal structures or polymorphs [14] [3] | Transition from pressed pellet to fusion method to create a homogeneous glass bead [18] [14] [3] |

| High Background Scatter | Use of excessive binder [14]; Rough pellet surface [20] | Use minimum required amount of binder [14]; Ensure smooth, flat pellet surface via sufficient pressure [14] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is particle size so critical in XRF sample preparation, and what is the optimal size? Achieving a fine and consistent particle size is vital for analytical accuracy. Larger or variable particle sizes can lead to heterogeneities in the sample, cause particle size effects during analysis, and result in poor pellet integrity when pressing [19] [14]. The ideal particle size for pelletizing is generally below 75 micrometres (µm), with below 50 µm being optimal for the best results [19]. Proper grinding ensures the analyzed volume is representative of the entire sample [14].

Q2: How do I choose between the pressed pellet and fusion method for my sample? The choice involves a trade-off between speed and the highest possible accuracy.

- Pressed Pellets are faster and more cost-effective. They are suitable for screening, process monitoring, and semi-quantitative analysis [18]. However, they may not fully eliminate mineralogical effects [3].

- Fusion is the benchmark for high-precision quantitative analysis. It involves dissolving the sample in a borate flux (e.g., Lithium Tetraborate) at high temperatures (1000-1200°C) to form a homogeneous glass bead [18]. This method eliminates mineralogical and particle size effects, making it ideal for applications demanding the highest accuracy, such as regulatory testing and exploration geochemistry [18] [14] [3].

Q3: My pressed pellets are cracking or not holding together. What should I do? Crumbling pellets are often a result of insufficient binding or incorrect pressing. First, verify that you are using an appropriate binder, such as cellulose or wax, at a concentration of 5-10% of the sample weight [14]. Second, ensure the hydraulic press is applying adequate pressure; most samples require 25-35 tonnes of pressure for 1-2 minutes to form a stable pellet [19]. Finally, confirm that the sample powder has been ground finely enough, as larger particles do not bind well [19].

Q4: What are the primary sources of contamination, and how can I avoid them? Sample contamination can originate from the grinding vessels, the binder, or the pressing dies [19]. To prevent this, use clean, well-maintained equipment for each sample [18]. The choice of grinding media (e.g., hardened steel, agate, or tungsten carbide) should be based on the sample's hardness and the potential for introducing contaminating elements that could interfere with your analysis [18] [14].

Workflow and Methodology

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Creating Pressed Powder Pellets This method is ideal for rapid and cost-effective sample preparation.

- Crushing: For bulk solid samples like rocks or ores, begin by using a jaw crusher to reduce the material to fragments between 2 mm and 12 mm [18].

- Subsampling: Use an automated rotary sample divider (RSD) to obtain a smaller, representative portion of the crushed material for further processing [18].

- Grinding: Transfer the subsample to a pulverizing mill (e.g., Ring & Puck mill) with compatible grinding media. Grind until the particle size is consistently below 75 µm [19] [14]. Testing different grinding times and measuring the resulting analytical consistency is recommended to determine the optimal duration [14].

- Mixing with Binder: Weigh approximately 7-10g of the ground powder. Add a binder like cellulose or wax at 5-10% of the sample weight. Mix thoroughly, which may include an additional 30 seconds of grinding to ensure homogeneity [14].

- Pressing: Load the mixture into a clean pellet die. Place the die in a hydraulic press and apply a force of 15-35 tonnes [18] [19] [14]. Maintain the pressure for 30 seconds to 2 minutes to ensure proper compression [19] [14].

- Ejection and Storage: Carefully eject the pellet from the die. Handle the pellet with clean gloves and store it in a sealed container to prevent moisture uptake and contamination before analysis [19].

Protocol 2: Preparing Samples via Fusion This method provides the highest accuracy by creating a chemically uniform glass bead.

- Sample Preparation: The sample must first be ground to a fine powder (as in the pressed pellet protocol) to ensure complete reaction with the flux [18].

- Flux Mixing: Accurately weigh the ground sample and mix it with a borate flux (e.g., Lithium Tetraborate or Lithium Metaborate) in a specific ratio, typically between 1:5 and 1:10 (sample-to-flux) [18].

- Fusion: Transfer the mixture to a platinum-gold alloy crucible. Place the crucible in a fusion furnace at 1000-1200°C until the mixture becomes fully molten [18].

- Homogenization and Pouring: Agitate the molten mixture to ensure complete homogenization. Then, pour it into a preheated mold made of platinum-gold [18].

- Cooling: Allow the melt to cool, forming a stable, homogeneous glass disk (fused bead) ready for XRF analysis [18].

Process Workflow Diagram

The following diagram outlines the logical decision-making process for selecting and applying the appropriate solid sample preparation technique for XRF analysis.

XRF Sample Prep Workflow

Grinding Optimization Diagram

This diagram illustrates the experimental protocol for determining the optimal grinding time for a sample to achieve particle size homogeneity.

Grinding Optimization Protocol

Research Reagent and Equipment Solutions

The following table details essential materials and equipment required for effective solid sample preparation for XRF analysis.

| Item | Function & Purpose | Key Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Jaw Crusher | Primary size reduction of bulk solid samples, breaking large pieces into smaller fragments (2-12 mm) [18]. | Generates minimal heat; easy to clean to prevent cross-contamination [18]. |

| Pulverizing Mill | Fine grinding of subsamples into a homogeneous powder [18] [14]. | Achieves particle size <75µm; available in various media (Tungsten Carbide, Agate, Hardened Steel) [18] [14]. |

| Hydraulic Pellet Press | Compresses powdered samples into solid, dense pellets for analysis [18] [21]. | Capable of applying 15-35 tonnes of pressure; features adjustable press force and time for reproducibility [19] [21]. |

| Fusion Furnace | Melts a mixture of sample and flux at high temperatures to form a homogeneous glass bead [18]. | Capable of reaching 1000-1200°C; uses platinum-gold crucibles and molds [18]. |

| Binder (e.g., Cellulose/Wax) | Added to powdered samples to act as a binding agent, providing mechanical strength to pressed pellets [19] [14]. | Typically used at 5-10% of sample weight; should be free of contaminating elements [14]. |

| Flux (e.g., Lithium Tetraborate) | A borate-based solvent that dissolves the sample matrix during fusion to create a homogeneous glass disk [18]. | Common sample-to-flux ratios range from 1:5 to 1:10 [18]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

ICP-MS Sample Preparation Troubleshooting

Q: My ICP-MS results show high background signals and poor detection limits for common elements. What should I investigate?

- A: This is frequently caused by contamination introduced during sample preparation.

- Check Reagent Purity: For ultratrace ICP-MS analysis, always use the highest purity acids and reagents. Lower purity acids can significantly contribute to background levels for elements like sodium, potassium, iron, copper, or zinc [22].

- Inspect Labware: Plasticware such as vials and vial caps can leach contaminants. Perform a preliminary leach test on new batches of labware [22].

- Verify Water Quality: Use high-purity water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ·cm and conduct regular checks for trace elements [22].

- Perform Blank Digestion: Run a blank digestion with every batch of samples, including all steps and reagents but no sample, to identify contamination from the digestion process itself [22].

Q: How should I prepare a liquid sample with high dissolved solids for ICP-MS analysis?

- A: Samples with high Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) can cause signal drift and plasma instability.

- Smart Dilution: The typical upper limit for TDS in ICP-MS is between 0.1% and 0.5% (m/v) [22] [15]. Dilute the sample to bring the TDS below this threshold. Using automated liquid dilution via an autosampler can improve accuracy and save time [22].

- Specialized Introduction Systems: Specialized nebulizers and spray chambers can handle higher TDS levels (up to 3-4%), but this reduces detection sensitivity [15].

- Acid Digestion: For solid samples, acid digestion is the standard protocol. Use a combination of acids (e.g., nitric acid with hydrogen peroxide for organic matrices) to achieve a clear, particle-free solution [15].

Q: What is the best way to handle organic liquid samples in ICP-MS?

- A: Organic solvents require specific instrument modifications to prevent carbon buildup and signal drift.

UV-Vis Spectroscopy Troubleshooting

Q: My UV-Vis spectrum shows unexpected peaks or a noisy, shifting baseline. What are the likely causes?

- A: These issues are often related to the sample, sample holder, or instrument stability.

- Clean the Cuvette: Unclean cuvettes or substrates can cause unexpected peaks. Thoroughly wash them and handle only with gloved hands to avoid fingerprints [23].

- Check for Contamination: Unexpected peaks can indicate contamination of your sample or solvent during preparation [23].

- Perform a Blank Test: Measure a pure solvent to establish a baseline. High or erratic blank absorbance indicates background interference, contamination, or stray light [24].

- Allow Lamp Warm-up: If using a tungsten halogen or arc lamp, allow 20 minutes after turning on the instrument before measuring to achieve consistent light output [23].

Q: The absorbance values for my sample are outside the ideal range. How can I correct this?

- A: This is typically a sample preparation or methodology issue.

- Adjust Concentration: If absorbance is too high, the sample concentration may be excessive. Dilute the sample to bring the absorbance into the ideal range of 0.2–1.0 AU to maintain linearity with the Beer-Lambert Law [25].

- Change Cuvette Path Length: Use a cuvette with a shorter path length to reduce the measured absorbance without diluting the sample [23].

- Verify Solvent and Settings: Ensure the solvent does not absorb strongly at your measurement wavelength and adjust instrument settings like scan speed or slit width to optimize the signal [23] [24].

Q: My sample is cloudy or contains particles. Can I analyze it directly with UV-Vis?

- A: No. Cloudy or particle-filled samples scatter light, which violates the principles of the Beer-Lambert Law and leads to inaccurate results [25].

- Filtration: Filter the sample using an appropriate syringe filter to remove particulates before analysis [25].

- Centrifugation: As an alternative to filtration, centrifugation can clarify the sample.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: For ICP-MS, when should I use microwave digestion versus simple dilution?

- A: Simple direct dilution is often sufficient for simple aqueous matrices like wine and is more time-efficient [26]. Microwave-assisted acid digestion is recommended for complex, difficult-to-dissolve matrices (e.g., tissues, soils) to ensure complete decomposition of organic matter and accurate results for all elements [22] [15].

Q: How does filtration order affect my ICP-MS results for complex liquids like wine?

- A: The order of acidification and filtration can significantly impact results. Studies on wine have shown that both filtration-acidification and acidification-filtration treatments can yield significantly different results for multiple isotopes compared to direct dilution or microwave digestion, likely due to the disruption of metal complexes with organic components [26].

Q: What purity of solvent should I use for HPLC coupled to UV-Vis or MS detection?

- A: The solvent purity is critical for sensitivity.

Q: How often should I calibrate my UV-Vis spectrophotometer?

- A: Regular calibration is essential. It should be performed before each set of critical tests or weekly, depending on usage frequency and application requirements. Always follow standards like USP 857 or manufacturer recommendations [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Sample Pretreatments for Wine Analysis by ICP-MS

A study compared four sample preparation methods for the elemental analysis of wine. The table below summarizes key findings for 43 monitored isotopes [26].

| Sample Preparation Method | Key Findings & Isotope Recovery | Ease of Use & Throughput |

|---|---|---|

| Direct Dilution (DD) | Good accuracy and precision for most elements; a suitable compromise for many applications. | High. Most user-friendly and time-efficient. |

| Microwave Digestion (MW) | Significantly higher results for 17 isotopes; increased risk of contamination from reagents. | Low. Most time-consuming and requires specialized equipment. |

| Acidification then Filtration (AF) | Lower results for 11 isotopes compared to other methods. | Moderate. |

| Filtration then Acidification (FA) | Lower results for 11 isotopes compared to other methods. | Moderate. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sample Preparation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl) | Digestion of samples and stabilization of analytes in solution for ICP-MS [22] [15]. | Use the highest purity available (e.g., trace metal grade) to minimize background contamination [22]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Enhances oxidation potential for digesting organic matrices during ICP-MS sample prep [22] [15]. | Often used in combination with nitric acid. |

| MS Grade Solvents | Mobile phase for LC-MS or sample solvent for high-sensitivity UV-Vis [27]. | Minimizes baseline noise and ion suppression in mass spectrometry [27]. |

| HPLC Grade Solvents | Mobile phase for standard HPLC-UV analysis [27]. | Reduces ghost peaks and baseline noise for UV detection [27]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Sample holder for UV-Vis spectroscopy, especially in the UV range [23]. | Provides high transmission of UV and visible light; reusable but must be kept meticulously clean [23]. |

| Internal Standards | Added to ICP-MS samples to correct for signal drift and matrix effects [15]. | Improves data accuracy and precision. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

ICP-MS Liquid Sample Preparation Workflow

UV-Vis Troubleshooting Pathway

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Automation in Sample Preparation

FAQ: My automated sample preparation workflow is not triggering. What should I check? Automation rules can fail to trigger for several reasons. Follow this diagnostic checklist to identify the root cause [28]:

- Audit Logs: Check the automation rule's audit logs. If no entry exists at the expected execution time, the rule was never triggered (Symptom 1) [28].

- Rule Scope: Ensure the rule is not set to a global scope, but is limited to specific projects to prevent unnecessary resource consumption and potential conflicts [28].

- Condition Checks: Verify that any associated "If" conditions, such as JQL queries, are correctly structured and return the expected issues for the rule to act upon [28].

- Queue Backlog: Investigate the automation queue size. A large, growing queue can cause significant delays in rule execution. Use database queries to monitor queue health [28].

FAQ: The automation rule ran successfully but did not produce the expected outcome. How do I investigate? A status of "SUCCESS" only indicates the rule executed without errors, not that the logic was correct [28].

- Action Verification: Systematically check each action within the rule. For instance, if an action sends an email, verify the recipient address and content. If it modifies a field, confirm the new value is valid [28].

- Smart Values: A common failure point is incorrect Smart Values, which dynamically pull data from issues. Check for syntax errors, misconfigured fields, or trigger issues that can cause these values to return empty [28].

Miniaturization and Micro-Sample Handling

FAQ: How can I prevent analytical errors when working with smaller sample volumes? Miniaturization amplifies the impact of preparation errors. Inadequate sample preparation is responsible for approximately 60% of all spectroscopic analytical errors [1].

- Homogeneity: With smaller volumes, ensuring the sample is perfectly homogeneous is critical. Any heterogeneity can lead to significant sampling error and non-reproducible results [1].

- Contamination Control: The surface-area-to-volume ratio increases with miniaturization, making micro-samples more susceptible to contamination from equipment or the environment. Implement stringent cleaning protocols [1].

- Surface Effects: The quality of the sample surface becomes paramount. Rough surfaces can scatter light unpredictably, while flat, polished surfaces ensure consistent interaction with analytical radiation [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Miniaturization Issues

| Issue | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High result variability | Sample heterogeneity | Optimize grinding/milling to achieve consistent, fine particle size (<75 μm for techniques like XRF) [1]. |

| Low analyte signal | Adsorption to container walls | Use appropriate vial materials (e.g., low-adsorption plastics), and consider high-purity acidification for liquid samples [1]. |

| Contamination peaks in spectrum | Cross-contamination or impure reagents | Clean equipment thoroughly between samples; use high-purity solvents and reagents [1]. |

Green Chemistry and Sustainable Methods

FAQ: How can I make my sample preparation more environmentally friendly without sacrificing accuracy? Adopting Green Chemistry principles starts with a fundamental rethink of the sample preparation process itself [29].

- Systematic Design: Move away from trial-and-error optimization. A careful consideration of the underlying principles of extraction can lead to more efficient and environmentally friendly technologies [29].

- Method Selection: Choose sample preparation techniques that minimize or eliminate organic solvents. For example, consider techniques that require smaller volumes of safer solvents or use no solvents at all [29].

- Direct Analysis: Where possible, explore analytical techniques that require minimal sample preparation, thereby reducing the consumption of energy and materials from the outset [29].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Metagenomic Sequencing for Virus Detection

This protocol, optimized for clinical samples, exemplifies a modern approach that integrates automation-friendly steps and miniaturization for high-throughput analysis [30].

1. Sample Pre-processing (Virus Enrichment)

- Centrifuge sample at 2,000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove coarse debris [30].

- Filter supernatant through a 0.45 μm PES filter to remove bacteria and larger particles [30].

- Perform nuclease treatment (DNase & RNase) for 1 hour at 37°C to digest free nucleic acids not protected within viral capsids [30].

2. Nucleic Acid Extraction

- Use automated extraction systems (e.g., NucliSENS EasyMAG) with large starting volumes (500-1000 μL) to maximize yield, eluting into a small volume (25 μL) to concentrate the sample [30].

3. Unbiased Amplification and Sequencing

- Perform random amplification of RNA and DNA in separate reactions to ensure comprehensive genome recovery [30].

- Proceed with library preparation and high-throughput sequencing [30].

This workflow has been validated for detecting a wide range of viruses in diverse clinical samples like plasma, urine, and throat swabs [30].

Workflow: Automated Troubleshooting Guide Execution

The following diagram illustrates the "StepFly" agentic framework, an advanced model for automating troubleshooting guides in analytical workflows [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Spectroscopic Sample Preparation

| Item | Function & Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Tetraborate | Flux agent for fusion techniques (XRF). | Fuses with samples at 950-1200°C to create homogeneous glass disks, eliminating mineralogical effects [1]. |

| Boric Acid / Cellulose | Binder for pelletizing (XRF). | Mixed with powdered samples to create stable, uniform pellets under 10-30 tons of pressure [1]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (e.g., CDCl₃) | Solvent for FT-IR spectroscopy. | Provides minimal interfering absorption bands in the mid-IR spectrum for clear analyte detection [1]. |

| PTFE Membrane Filters | Filtration for ICP-MS. | Removes suspended particles (0.2-0.45 μm) to protect nebulizers; chosen for low contamination and minimal analyte adsorption [1]. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Acidification for ICP-MS. | Prevents precipitation and adsorption of metal ions to container walls (typically used at 2% v/v) [1]. |

| KBr (Potassium Bromide) | Matrix for FT-IR pellet preparation. | Transparent to IR radiation; finely ground and mixed with solid samples to form pellets for analysis [1]. |

Troubleshooting and Optimization: Solving Common Sample Preparation Challenges

Troubleshooting Guide: Contamination

Contamination is a critical issue in spectroscopic analysis, particularly for trace-level elemental measurements, as it can lead to false positives and inaccurate data. The table below summarizes common contamination sources and their mitigation strategies.

Table 1: Common Contamination Sources and Mitigation Strategies

| Contamination Source | Specific Examples | Impact on Analysis | Proven Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Labware & Containers | Glass (beakers, flasks, vials) [7]Pigmented plastics with metal additives [8] | Leaching of ubiquitous metals (e.g., Al, Zn) into acidic or basic samples, raising procedural blanks [7] [8]. | Use high-purity plasticware (e.g., PP, LDPE, PFA, FEP) [7] [8].Acid-rinse new labware before use to remove manufacturing residues [8]. |

| Reagents & Solvents | Acids in glass containers [7]Impure water (low resistance) [8] | Introduction of elemental contaminants (e.g., Na, Al, Fe, B, Si) directly into the sample [8]. | Use ultrahigh-purity acids supplied in fluoropolymer bottles [7] [8].Use 18 MΩ.cm deionized water and maintain the purification system [8]. |

| Laboratory Environment | Airborne particulate from vents, corroded metal, or dirt on shoes [8] | Particulate matter falling into open samples, introducing a variable mix of contaminants [8]. | Use HEPA-filtered laminar flow hoods for sample prep [7] [8].Implement "sticky mats" at entrances and control laboratory access [8]. |

| Personal & Handling | Powdered gloves [7]Fingertips inside sample tubes [7]Pipettes with external steel tip ejectors [7] | Direct introduction of particles, skin cells, or metals (e.g., Fe, Cr, Ni) into the sample [7]. | Wear powder-free nitrile gloves [7] [8].Use pipettes without external metal parts and avoid touching critical surfaces [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Cleaning and Preparing Labware for Ultratrace Metal Analysis

This protocol is designed to minimize background contamination from sample vials and containers for techniques like ICP-MS [8].

- Initial Rinse: Fill new polypropylene or fluoropolymer vials and tubes with a dilute acid solution (e.g., 0.1% ultrapure HNO₃).

- Soaking: Soak the labware for a minimum of several hours (or overnight) in a covered plastic container to prevent airborne contamination.

- Final Rinsing: Discard the acid and thoroughly rinse the labware three times with ultrapure water (UPW).

- Drying and Storage: Allow the labware to air-dry in a clean, particulate-free environment. Store in sealed, clean containers until use.

Troubleshooting Guide: Incomplete Dissolution

Incomplete dissolution or improper solvent choice can cause a range of analytical problems, from distorted peaks and poor repeatability in HPLC to inaccurate quantitation in spectroscopy.

Table 2: Common Issues from Incomplete or Improper Dissolution

| Problem | Root Cause | Observed Effects | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Tailing & Splitting | Strong sample-column interactions [32].Incompatible mobile phase and sample solvents [32]. | Poor separation, reduced resolution, inaccurate integration [32]. | Adjust mobile phase pH or composition [32].Match sample solvent strength to the starting mobile phase [33] [32]. |

| Poor Repeatability | Variable injection volume due to air aspiration from low liquid level [34].Incomplete sample filtration or dissolution [34]. | High variation in peak areas (%RSD) and retention times [34]. | Ensure sample volume is sufficient and vials are not empty [34].Filter samples (0.2–0.45 μm) and centrifuge if necessary [34]. |

| Ghost Peaks | Contaminated sample or mobile phase [32].Precipitation of sample in the flow path [32]. | Unexpected peaks in the chromatogram, interfering with analyte identification and quantitation [32]. | Purify the sample and filter the mobile phase [32].Ensure sample solvent is compatible with the mobile phase [33] [32]. |

| Broadened or Distorted Peaks | Sample solvent is stronger than the mobile phase [33]. | Poor peak shape, including fronting or broadening, which lowers detection sensitivity and resolution [33]. | Dilute the sample solution with a low-strength solvent [33].Reduce the sample injection volume [33]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing Sample Dissolution for HPLC

A methodical approach to ensure complete dissolution and solvent compatibility for reliable HPLC analysis [34] [33].

- Solvent Selection: The ideal solvent is the mobile phase itself. If the sample is insoluble in the mobile phase, choose a solvent of weaker eluting strength.

- Dissolution and Homogenization: Vigorously mix or sonicate the sample to ensure it is completely dissolved. For solid samples, grinding to a uniform particle size can aid dissolution [35].

- Filtration: Pass the sample solution through a 0.2 μm or 0.45 μm syringe filter to remove any undissolved particulates or impurities that could clog the column [34].

- Compatibility Check: If peak distortion occurs, reduce the injection volume or further dilute the sample with the starting mobile phase to better match the solvent strengths [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Optimized Sample Preparation

| Item | Function | Critical Quality Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (e.g., HNO₃, HCl) | Sample digestion and stabilization for metal analysis [7] [8]. | Double-distilled in PFA or quartz; supplied in fluoropolymer bottles (PFA, FEP) to avoid leaching from glass [7]. |

| Ultrapure Water | Primary diluent for aqueous solutions; rinsing labware [8]. | Resistivity of 18 MΩ·cm; low levels of specific contaminants like B and Si [8]. |

| High-Purity Plasticware (PP, LDPE, PFA) | Sample containers, vials, and pipette tips for trace metal analysis [7] [8]. | Clear, unpigmented polymer; certified for trace element analysis; should be acid-rinsed before first use [8]. |

| Syringe Filters | Removal of particulate matter from liquid samples prior to injection in HPLC or UV-Vis [34]. | Pore size (0.2 μm or 0.45 μm); membrane material compatible with the sample solvent (e.g., Nylon, PTFE) [34]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Verification of method accuracy and precision by analyzing a material with a known analyte concentration [35]. | Matrix-matched to the sample; provided with a certificate of analysis detailing uncertainty. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Sample Preparation

Q: Why is sample homogeneity so critical in spectroscopic analysis? A: Sample homogeneity ensures that the small portion you analyze is representative of the entire bulk material. Inhomogeneity leads to variations in the analytical signal, causing inaccurate and non-reproducible results. Techniques like grinding, milling, and thorough mixing are used to achieve homogeneity [35].

Q: How can I verify that my sample preparation method is accurate? A: Method verification can be achieved by analyzing a Certified Reference Material (CRM) with a known concentration of your analyte and comparing your result to the certified value. Participation in inter-laboratory comparison programs or proficiency testing also provides a robust check [35].

Contamination Control

Q: I work with ICP-MS. Why should I absolutely avoid using glassware? A: Glass is a significant source of elemental contaminants. Acidic or basic solutions will readily leach metals (e.g., sodium, potassium, aluminum, boron, silicon) from the glass matrix into your sample. This elevates your procedural blanks and method detection limits, potentially causing false positive results [7] [8]. The one notable exception is the analysis of mercury as a lone analyte, as glass typically has very low mercury content [7].

Q: What are the best practices for storing samples to prevent contamination? A: Samples should be stored in airtight containers made of high-purity plastics like polypropylene or fluoropolymers. For stability, store in a cool, dry, and dark place. Using dedicated clean containers and minimizing the time samples are left open to the laboratory environment is crucial [36].

Dissolution and Solvent Issues

Q: My HPLC peaks are broad or distorted, even though the sample dissolved. What could be wrong? A: This is a classic sign of a sample solvent that is stronger (has a higher eluting strength) than your starting mobile phase. When injected, the sample creates a local disturbance in the chromatographic conditions. The solution is to dilute your sample solution with a weaker solvent (or your starting mobile phase) or to reduce the injection volume [33].

Q: What causes "ghost peaks" in my chromatograms, and how can I eliminate them? A: Ghost peaks are typically caused by contaminants. The source can be the mobile phase (use high-purity solvents and filter them), the sample itself (purify it further), or a contaminated column (flush with strong solvent or replace the guard column). A dirty detector can also be a cause and may require cleaning [32].

Sample preparation is a foundational step in spectroscopic and mass spectrometry-based research, with its optimization being critical for data accuracy and reliability. Inadequate preparation is responsible for a significant portion of analytical errors, underscoring the need for robust, method-specific protocols [1]. This guide delves into specific case studies and troubleshooting advice to help researchers navigate the complexities of optimizing lysis conditions for the recovery of DNA and proteoforms, which is essential for downstream applications ranging from clinical PCR to top-down proteomics.

Case Study 1: Optimizing DNA Recovery for Fungal Pathogen Detection

Experimental Context and Challenge

The accurate detection of fungal pathogens like Aspergillus fumigatus and Candida albicans in clinical samples such as bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid via PCR hinges on the efficient lysis of robust fungal cell walls and the recovery of high-quality DNA. A comparative study was undertaken to evaluate the performance of six different DNA extraction methods on these pathogens [37].

Key Experimental Protocols

- Sample Preparation: A. fumigatus conidia or C. albicans yeast cells were added to BAL fluid. To simulate hyphal growth, A. fumigatus conidia were allowed to form mycelia in tissue culture media before harvesting [37].

- Evaluation Method: DNA recovery was quantitatively assessed using PCR assays to measure the yield from a defined number of fungal propagules [37].

Results and Data Analysis

The differences in DNA yield among the six methods were highly significant (P<0.0001). The performance of each method varied substantially depending on the fungal species and morphology [37].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Yields from Different Extraction Methods

| Extraction Method | C. albicans Yeast Cells | A. fumigatus Conidia | A. fumigatus Hyphae |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Lysis (GNOME kits) | High DNA Yields | Low DNA Yields | Low DNA Yields |

| Methods with Bead Beating | Not Specified | Not Specified | Highest DNA Yields |

| MasterPure Yeast Method | High DNA Yields | Moderate DNA Yields | Not Specified |

Troubleshooting and FAQs

- Problem: Low DNA yield from Aspergillus fumigatus conidia or hyphae.

- Solution: Avoid relying solely on enzymatic lysis methods. Implement extraction protocols that incorporate mechanical disruption, such as bead beating, which was proven most effective for breaking tough hyphal structures [37].

- Problem: Suspicion of contaminating fungal DNA in PCR reagents.

- Solution: Include negative controls during the extraction process. One study found reagent contamination from a specific extraction kit, highlighting the need for rigorous quality control of all buffers and solutions [37].

Optimized Workflow Diagram

Case Study 2: Optimizing Proteoform Recovery for Top-Down Proteomics

Experimental Context and Challenge

In top-down proteomics, the analysis of intact proteoforms (specific molecular forms of a protein) is often hampered by the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) used in preliminary fractionation. Efficient removal of SDS is critical for subsequent Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis, but common methods like methanol-chloroform-water (MCW) precipitation can lead to poor recovery of certain proteoforms [38].

Key Experimental Protocols

A study benchmarked the traditional MCW precipitation against four commercial SDS clean-up kits:

- DetergentOUT

- HiPPR

- MinuteSDS

The recovered proteoforms were then analyzed using LC-MS/MS to compare the performance of each clean-up method in terms of proteoform identifications, with a focus on size and charge characteristics [38].

Results and Data Analysis

The study revealed that the choice of clean-up method significantly impacts the depth and breadth of proteoform coverage.

Table 2: Comparison of SDS Clean-up Methods for Proteoform Recovery

| Clean-up Method | Overall Proteoform IDs | Recovery of Small Proteoforms | Recovery of Acidic Proteoforms | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MCW Precipitation | Fewer IDs | Poor | Poor | Low |

| DetergentOUT Kit | Comparable to MCW | Improved | Improved | High |

| HiPPR Kit | Comparable to MCW | Improved | Improved | High |

| MinuteSDS Kit | Sufficient SDS removal, broader coverage | Good | Good | Lower Cost |

Troubleshooting and FAQs

- Problem: Low recovery of small (< 25 kDa) or acidic proteoforms after clean-up.

- Solution: Avoid MCW precipitation. Opt for commercial kits like DetergentOUT or HiPPR, which demonstrated better recovery of these specific proteoform classes [38].

- Problem: Need for a cost-effective SDS removal method that still provides good proteome coverage.

- Solution: The MinuteSDS kit was identified as a lower-cost commercial alternative that provides sufficient SDS removal and broader proteome coverage compared to MCW [38].

- Problem: Inefficient lysis of mammalian tissues for western blotting, leading to low protein yield.

- Solution: For tissues, use RIPA buffer for nuclear proteins and Tris-HCl buffer for cytoplasmic proteins. Combine with mechanical homogenization and consider sonication to shear DNA. Always supplement lysis buffers with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails to preserve the protein of interest [39].

Optimized Workflow Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the appropriate reagents is paramount for successful sample preparation. The table below summarizes key solutions discussed in the case studies.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Lysis and Clean-up

| Reagent / Kit Name | Primary Function | Key Applications | Important Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | Efficient lysis using ionic & non-ionic detergents. | Extraction of membrane, cytoplasmic, and nuclear proteins from cells/tissues [40] [39]. | May denature sensitive proteins; supplement with protease inhibitors. |

| M-PER Extraction Reagent | Mild, non-denaturing lysis. | Extraction of soluble proteins from mammalian cells; compatible with activity assays [40]. | Less effective for tough tissues or nuclear proteins. |

| B-PER Reagent | Bacterial cell wall lysis. | Protein extraction from bacterial cells [40]. | Formulated with enzymes/detergents specific for bacterial walls. |

| Bead Beating Kits | Mechanical cell disruption. | Lysis of tough structures (e.g., fungal hyphae, microbial cells) [37]. | Essential for organisms resistant to chemical/enzymatic lysis. |

| DetergentOUT / HiPPR Kits | SDS removal from protein samples. | Sample clean-up for top-down proteomics prior to LC-MS/MS [38]. | Superior for recovering small/acidic proteoforms; higher cost. |

| Methanol-Chloroform-Water (MCW) | Protein precipitation & SDS removal. | Low-cost sample clean-up [38]. | Can lead to significant loss of small and acidic proteoforms. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevent protein degradation. | Added to lysis buffers for all sample types, especially tissues [39]. | Critical for preserving post-translational modifications. |

Optimizing lysis and clean-up conditions is not a one-size-fits-all process. As demonstrated, the optimal method depends critically on the sample type (e.g., yeast vs. hyphae) and the analytical goal (e.g., DNA PCR vs. intact proteome analysis). Key takeaways for researchers include:

- Mechanical lysis is superior for tough cellular structures like fungal hyphae [37].

- Specialized clean-up kits, while sometimes more expensive, can prevent the selective loss of critical analytes like small proteoforms, which is a limitation of traditional methods like MCW precipitation [38].

- Buffer selection must be tailored to the sample and target, considering factors like cellular localization and the need to preserve protein function or modifications [40] [39].

By applying the detailed protocols, troubleshooting guides, and reagent selection tools provided here, researchers can systematically overcome common sample preparation challenges and enhance the reliability of their spectroscopic and mass spectrometry analyses.

Leveraging Design of Experiments (DoE) for Systematic Process Improvement

In spectroscopic analysis, sample preparation is a critical step that directly determines the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of your results. Traditional optimization methods, which change one variable at a time (OVAT), are inefficient and often fail to identify interactions between critical factors. Design of Experiments (DoE) is a systematic, multivariate approach that allows researchers to efficiently understand the complex relationships between multiple input variables and their collective impact on spectroscopic outcomes. By implementing DoE, you can transform sample preparation from an art into a science, ensuring robust, transferable methods while saving significant time and resources.

Core DoE Concepts and Workflow

Design of Experiments involves strategically planning experiments to extract maximum information from minimum experimental runs. It enables you to:

- Identify Critical Factors: Screen numerous potential factors to determine which ones significantly impact your spectroscopic results.

- Model Interactions: Discover how factors interact with each other, which is impossible with OVAT approaches.

- Optimize Processes: Find the optimal combination of factor settings to achieve your desired analytical outcome, such as maximum signal-to-noise ratio or minimum background interference.

The following diagram illustrates the systematic, iterative workflow for implementing DoE in your sample preparation development.

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Screening with Fractional Factorial Design (FFD)

Objective: To efficiently identify the most influential factors from a large set of potential variables in sample preparation for mass spectrometry.

Background: When developing a new sample preparation method, numerous factors (e.g., buffer concentration, digestion time, temperature) could influence the final spectroscopic result. Testing all possible combinations is impractical. FFD allows for a balanced subset of experiments to identify the "vital few" factors from the "trivial many" [41].

Methodology:

- Select Factors and Ranges: Choose the factors to investigate based on prior knowledge and set realistic high (+) and low (-) levels for each. For a proteomics digestion, this might include:

- Digestion Time (e.g., 4 hours [-] vs. 18 hours [+])

- Enzyme-to-Substrate Ratio (e.g., 1:50 [-] vs. 1:20 [+])

- Temperature (e.g., 30°C [-] vs. 37°C [+])

- Urea Concentration (e.g., 1M [-] vs. 2M [+])

- Reduction/Alkylation Time (e.g., 30 min [-] vs. 60 min [+])

- Choose a Design Matrix: Select a fractional factorial design (e.g., a 2^(5-1) design requiring 16 runs instead of a full factorial's 32 runs). This design is resolution V, meaning it can estimate main effects independently of two-factor interactions.

- Randomize and Execute: Randomize the run order to avoid confounding with external variables and perform the sample preparations according to the design matrix.

- Analyze Responses: For each experiment, measure key spectroscopic responses such as Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), number of unique peptide identifications in MS, or peak intensity of the target analyte.

- Statistical Analysis: Use statistical software (e.g., JMP, Minitab, R) to perform an Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). Factors with p-values below a chosen significance level (e.g., p < 0.05) are considered significant.

Protocol: Optimization with Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

Objective: To model the relationship between the critical factors identified in the screening phase and the response variable, in order to find the optimal settings.

Background: After screening, you know which factors matter. RSM helps you understand the curvature of the response and locate the true optimum, which could be a maximum (e.g., highest SNR), minimum, or a target value [41].

Methodology:

- Select Design: Common RSM designs include Central Composite Design (CCD) and Box-Behnken Design (BBD). For instance, a face-centered CCD was used to optimize ESI source parameters for LC-MS/MS, varying factors like capillary voltage, nebulizer pressure, and gas temperature [41].

- Define Experimental Domain: Set the levels for the factors (typically 3-5 levels for a CCD) based on the results of the screening phase.

- Run Experiments and Model: Execute the designed experiments and fit a quadratic model to the data. The model has the form:

Y = β₀ + ΣβᵢXᵢ + ΣβᵢᵢXᵢ² + ΣΣβᵢⱼXᵢXⱼWhere Y is the predicted response, β₀ is the constant, βᵢ are linear coefficients, βᵢᵢ are quadratic coefficients, and βᵢⱼ are interaction coefficients. - Interpret and Optimize: Use contour plots and 3D response surface plots to visualize the relationship between factors and the response. The model can then be used to pinpoint the factor settings that produce the best possible response.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials used in sample preparation for spectroscopic analysis, along with critical considerations identified through DoE studies.

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations & DoE Insights |

|---|---|---|

| Trypsin | Enzyme for protein digestion in bottom-up proteomics (MS) | Predigestion with Lys-C (urea-tolerant) improves efficiency. DoE can optimize enzyme-to-substrate ratio and incubation time to minimize missed cleavages [42]. |

| Urea | Protein denaturant for solubilization | Can cause carbamylation; use fresh solutions and avoid elevated temperatures. A critical factor to control in screening designs [42]. |

| Detergents | Solubilize membrane proteins | Avoid PEG-based (e.g., Triton X-100); use MS-compatible alternatives like DDM. A key categorical factor in screening designs for membrane proteomics [42]. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Matrix for solid sample analysis in IR spectroscopy | Used to create transparent pellets. DoE can optimize grinding time, pressure, and sample-to-KBr ratio for optimal clarity and spectral quality [43]. |

| Volatile Salts (e.g., Ammonium Acetate) | Buffer for LC-MS compatible solutions | Replace non-volatile salts (e.g., phosphate buffers) to prevent ion suppression in the ESI source. A vital factor for response optimization in MS [42]. |

| Cuvettes/ Cells | Sample holder for UV-Vis, IR | Path length is a critical continuous factor. DoE can optimize path length and concentration simultaneously to remain within the linear range of the Beer-Lambert law [44]. |

| ATR Crystals (ZnSe, Ge) | For non-destructive solid/liquid analysis in IR | Factors like pressure applied and number of scans can be optimized via DoE to maximize reproducibility and signal intensity [43]. |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: Our DoE model shows a poor fit (low R²). What could be the cause and how can we fix it?

- Cause: High variability in experimental runs, often due to poor control over sample homogeneity or inconsistent manual preparation steps.

- Solution: Ensure sample homogeneity through rigorous grinding and mixing protocols [35]. Incorporate replication (e.g., center points) into your design to estimate pure error. If using a manual solid sample preparation method like KBr pellet formation, ensure the process is highly standardized before running the DoE.

Q2: We've found the optimal conditions, but the method is not robust when transferred to another lab. Why?

- Cause: The DoE was performed under overly ideal or narrowly controlled conditions without accounting for "noise" variables (e.g., different analysts, reagent batches, ambient humidity).

- Solution: In the optimization phase, include a robustness test using a design like a Plackett-Burman, where you intentionally vary noise factors at low and high levels to ensure your optimal solution is insensitive to these changes.

Q3: How do we handle categorical factors (e.g., choice of solvent or detergent type) in a DoE?

- Cause: Many sample preparation methods involve choices between different materials or techniques.

- Solution: Most modern DoE software can handle mixture and categorical factors. You can run a screening design with the categorical factor (e.g., Detergent: DDM vs. CYMAL-5 vs. None) as one of your factors. The analysis will tell you if the choice of detergent has a significant effect and may suggest different optimal settings for each type [42].

Q4: Our main goal is to maximize signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in our UV-Vis spectra, but we also need to minimize cost. Can DoE handle this?

- Cause: Real-world optimization often involves balancing multiple, sometimes conflicting, goals.

- Solution: Yes. Use a Desirability Function approach within RSM. You will model each response (e.g., SNR, Cost) separately. Then, the software combines these into a composite "desirability" score (ranging from 0 to 1) and finds the factor settings that maximize this overall score, providing a compromise solution that best satisfies all your criteria [35].

Q5: We see a significant interaction effect between digestion time and temperature in our model. How should we interpret this?

- Cause: Interaction means the effect of one factor depends on the level of another.

- Solution: This is a common and critical finding. For example, the model might show that increasing temperature greatly improves efficiency at a long digestion time, but has little effect at a short digestion time. Visualize this with an interaction plot. The optimal strategy is not to set each factor independently, but to choose the combination (e.g., higher temperature with shorter time) that delivers the best outcome, which would have been missed completely with an OVAT approach.

Validation and Comparative Analysis: Selecting and Qualifying Your Sample Preparation Method

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Sample Preparation Failures in Spectroscopy

This guide helps diagnose and resolve frequent issues encountered during sample preparation for various spectroscopic techniques.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Sample Preparation Problems

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution | Recommended Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| High spectral background/noise | Contaminated solvents or equipment, fingerprint contamination on IR windows [45] | Use LC-MS grade solvents, wear appropriate gloves, use low-binding tubes and filter tips [46] [47]. | All, especially MS and IR |