Qualitative vs Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

This article provides a thorough exploration of the distinctions and synergies between qualitative and quantitative spectroscopic analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Qualitative vs Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of the distinctions and synergies between qualitative and quantitative spectroscopic analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, core methodologies, and practical applications across techniques like UV-Vis, IR, NMR, MS, and Raman spectroscopy. The content addresses common analytical challenges, optimization strategies using chemometrics, and validation protocols to ensure regulatory compliance. By synthesizing current practices and emerging trends, this guide serves as an essential resource for implementing robust spectroscopic methods in research, quality control, and process optimization within the biomedical sector.

Core Principles: Understanding the 'What' vs. the 'How Much' in Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectrochemical analysis forms the cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, particularly in regulated industries like pharmaceuticals. These methods are fundamentally divided into two distinct paradigms: qualitative analysis, concerned with identifying the chemical nature of substances, and quantitative analysis, focused on precisely measuring the amount or concentration of specific components. Within the pharmaceutical industry, both analytical approaches are integral to ensuring drug safety, efficacy, and quality from raw material testing to final product release. Qualitative analysis confirms the identity and purity of materials, while quantitative analysis verifies that active ingredients are present within the specified dosage range and that impurities are below acceptable thresholds [1].

This guide explores the defining goals, methodologies, and technical requirements of qualitative and quantitative analysis, framing them within the context of spectroscopic techniques. We will examine how their distinct purposes shape experimental design, from instrument configuration to data interpretation, and provide detailed protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Conceptual Distinctions

The primary distinction between qualitative and quantitative analysis lies in their fundamental analytical goals. Qualitative analysis answers the question "What is it?" by identifying the chemical composition, structure, or functional groups present in a sample. Its objective is non-numerical information about chemical identity. In contrast, quantitative analysis answers "How much is there?" by providing a numerical measurement of the amount or concentration of a specific substance [1].

These differing goals necessitate different approaches to data collection and interpretation. Qualitative assessment often relies on matching spectral patterns or retention times to reference standards, such as using Infrared (IR) spectroscopy to identify functional groups in a molecule or Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to elucidate molecular structure [1]. Quantitative measurement, however, depends on establishing a relationship between instrumental response and analyte concentration, most commonly through the Beer-Lambert law in spectroscopy or calibration curves in chromatographic and mass spectrometric techniques [2].

Table 1: Conceptual Comparison Between Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

| Feature | Qualitative Analysis | Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identification of components, chemical structure, and purity [1] | Measurement of precise concentration or amount [1] |

| Research Question | "What is this substance?" | "How much of this substance is present?" |

| Output | Non-numerical data (e.g., identity, structure, presence/absence) [1] | Numerical data (e.g., concentration, percentage, mass) [1] |

| Key Pharmaceutical Applications | Raw material identification, impurity screening, identity confirmation [3] [1] | Assay of active ingredient, dissolution testing, impurity quantification [3] |

Technical Requirements and Methodologies

The fundamental differences in analytical goals directly translate to specific technical requirements, particularly in spectroscopic instrumentation and method validation.

Instrumental Configuration: The Monochromator Example

A clear example of this methodological divergence is in the configuration of monochromator slit widths in spectroscopic instruments. Quantitative analysis requires high resolution and precision in absorbance measurements to accurately determine concentration. This is achieved by using narrow slit widths, which enhance spectral resolution and ensure that the measured absorbance is specific to the analyte's wavelength, thereby yielding a more linear and reliable calibration curve [4].

Conversely, qualitative analysis, especially when surveying an unknown sample, prioritizes signal intensity to detect the presence of all potential components. This is achieved with wider slit widths, which allow more light to pass through the sample, improving the signal-to-noise ratio and enabling the detection of trace components that might otherwise be missed [4]. While this comes at the cost of reduced spectral resolution, it is a necessary trade-off for comprehensive identification.

Calibration and Validation Approaches

Calibration methods also differ significantly between the two paradigms.

- Quantitative Calibration: Relies on generating a calibration curve by plotting instrument response against known concentrations of standard solutions [2] [5]. The Beer-Lambert law ((A = εbc)) forms the basis for quantitative spectroscopic analysis, where absorbance (A) is proportional to concentration (c) [2]. To mitigate matrix effects, the internal standard method is often employed, where a known compound with similar properties to the analyte is added to correct for variations [2] [5].

- Qualitative Calibration: Often involves building spectral libraries. For example, techniques like FTNIR and Raman spectroscopy require a validated library of reference materials. Unknown samples are then identified by matching their spectral signature to an entry in this library [1].

Table 2: Technical Requirements for Qualitative vs. Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis

| Technical Aspect | Qualitative Analysis | Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Instrumental Goal | Detection and identification | Precise and accurate measurement |

| Typical Slit Width | Wider for better signal and detection [4] | Narrower for higher resolution and precision [4] |

| Calibration Method | Spectral libraries, retention time databases [1] | Calibration curves (e.g., using standard solutions) [2] [5] |

| Data Output | Spectrum, chromatogram, functional group identification | Concentration, mass, percentage, ratio |

| Key Performance Metrics | Probability of identification, specificity, selectivity | Accuracy, precision, limit of detection (LOD), limit of quantification (LOQ) [2] |

| Linear Dynamic Range | Less critical | Essential; defines the working concentration range for accurate measurement [2] |

Experimental Protocols in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Protocol for Qualitative Identification of a Raw Material by FTIR

Objective: To confirm the identity of an incoming raw material (e.g., an active pharmaceutical ingredient or excipient) against a certified reference standard.

Methodology: Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Sample Preparation:

- For a solid sample, mix a small quantity (1-2 mg) of the test material with dry potassium bromide (KBr, ~100 mg). Grind thoroughly using an agate mortar and pestle to create a homogeneous mixture.

- Compress the mixture into a transparent pellet using a hydraulic press.

- For the reference standard, prepare a pellet in an identical manner.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Acquire a background spectrum using a clean KBr pellet.

- Load the sample pellet and obtain the IR spectrum in the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹.

- Under the same conditions, obtain the IR spectrum of the reference standard pellet.

Identification and Analysis:

- Compare the positions and relative shapes of the major absorption bands (functional group region and fingerprint region) of the test sample to those of the reference standard.

- The identity is confirmed if the spectrum of the test sample exhibits all significant absorption maxima and minima present in the reference standard spectrum.

Protocol for Quantitative Analysis by ICP-MS

Objective: To quantify trace levels of elemental impurities (e.g., As, Se, Cd) in a drug substance.

Methodology: Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) with Internal Standardization [5].

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh approximately 0.1 g of the homogenized drug substance.

- Digest the sample in 5 mL of high-purity concentrated nitric acid using a microwave digester.

- After digestion and cooling, dilute the solution to a final volume of 50 mL with deionized water, resulting in a final acid concentration of 1% HNO₃.

Standard and Internal Standard Preparation:

- Prepare a series of multi-element calibration standards (e.g., STD1: blank, STD2: 0.5 µg/L, STD3: 1 µg/L, STD4: 2 µg/L for As and Se; appropriate levels for Cd) in 1% HNO₃ [5].

- Add internal standard elements (e.g., Gallium (Ga) and Indium (In) at 5 µg/L each) to all calibration standards and to the prepared unknown test samples [5]. The internal standard should have similar mass and ionization potential to the analytes.

Instrumental Analysis:

- Tune the ICP-MS for optimal sensitivity and stability.

- For quantitative analysis, set the instrument to monitor specific isotopes (e.g., As-75, Se-78, Cd-111) and the internal standard isotopes (Ga-71, In-115) with longer integration times than used for qualitative surveys.

- Run the calibration standards to generate a calibration curve for each element, with the y-axis as the ratio of the analyte ion intensity to the internal standard ion intensity (IS/IR) [5].

Quantification:

- Analyze the unknown test sample.

- The instrument software converts the measured ion intensity ratio for each analyte into concentration based on the calibration curve equation.

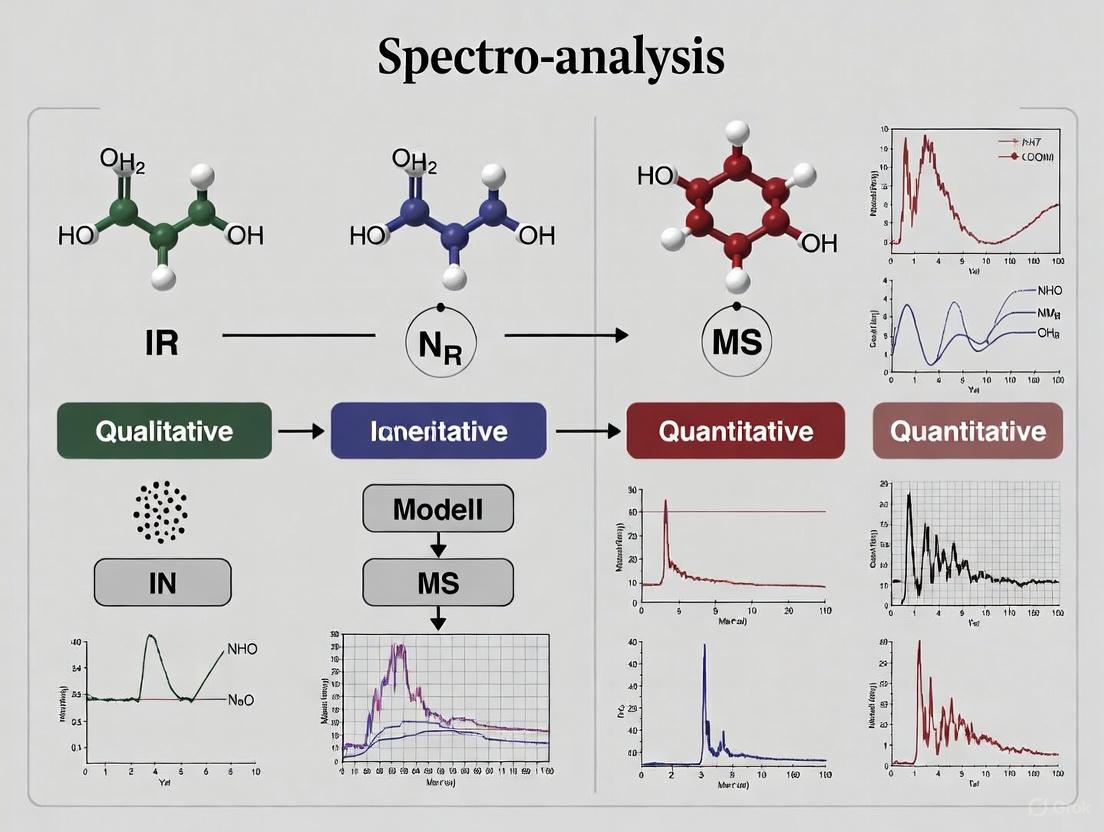

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflows for qualitative and quantitative analysis, highlighting their distinct paths and decision points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Certified Reference Standards | High-purity materials with certified identity and/or purity; essential for both qualitative identification and constructing quantitative calibration curves. |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | Infrared-transparent matrix used for preparing solid samples for FTIR analysis via the KBr pellet method [1]. |

| Internal Standard Solutions | Known compounds (e.g., Ga, In, Y for ICP-MS) added to correct for matrix effects and instrument drift in quantitative analysis [5]. |

| High-Purity Acids & Solvents | Essential for sample preparation and digestion (e.g., nitric acid for ICP-MS) to prevent contamination that would interfere with analysis [5]. |

| Mobile Phase Solvents (HPLC grade) | High-purity solvents and buffers used as the liquid phase in HPLC for separating components before detection. |

| Spectroscopic Cells/Cuvettes | Containers of defined path length (e.g., for UV-Vis) made from materials (quartz, glass) transparent to the relevant radiation. |

Qualitative and quantitative analyses, while often employed on the same samples, serve fundamentally different purposes that dictate every aspect of methodological design. Qualitative analysis prioritizes detection and identification, often employing techniques and instrument settings that maximize the ability to detect the presence of components. Quantitative analysis demands precision, accuracy, and numerical rigor, requiring carefully calibrated methods that can reliably translate an instrument's signal into a definitive concentration value. In the pharmaceutical industry, the synergy between these two approaches is critical. Confirming a material's identity is meaningless without knowing its potency, and measuring potency is futile without first verifying identity. A deep understanding of their distinct goals, requirements, and methodologies is therefore indispensable for researchers dedicated to ensuring product quality and patient safety.

Spectroscopic analysis is fundamentally based on the interactions between matter and electromagnetic radiation. When light energy interacts with a sample, it can be absorbed, emitted, or scattered in ways that are characteristic of the sample's molecular and atomic composition. These interactions form the basis for two complementary analytical approaches: qualitative analysis, which identifies what is present in a sample, and quantitative analysis, which determines how much is present [6]. In qualitative analysis, specific energy transitions create spectral "fingerprints" that are unique to particular chemical structures, functional groups, or elements. Quantitative analysis builds upon these identified features, measuring the intensity of these spectroscopic responses to determine concentration based on fundamental relationships like the Beer-Lambert law [7].

The pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical industries rely heavily on both approaches throughout drug discovery, development, and quality control. From identifying unknown compounds during early research to precisely quantifying active ingredients in final dosage forms, spectroscopic techniques provide critical data that ensures drug safety, efficacy, and consistency [8]. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of qualitative and quantitative spectroscopic analysis, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for leveraging these powerful analytical tools.

Foundational Principles: Qualitative Versus Quantitative Analysis

Core Definitions and Distinctions

Qualitative Analysis: This approach focuses on identifying the chemical components, functional groups, and molecular structures present in a sample. It answers the question "What is this substance?" by detecting characteristic spectral patterns. For example, infrared spectroscopy can identify an alcohol by the presence of a broad O-H stretch around 3200-3600 cm⁻¹, while nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy can distinguish between different hydrogen environments in a molecule [6] [7].

Quantitative Analysis: This approach measures the concentration or amount of specific components in a sample, answering "How much is present?" It relies on the relationship between the intensity of a spectroscopic signal and the concentration of the analyte. Ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, for instance, uses absorbance measurements at specific wavelengths to determine analyte concentration through established calibration curves [6].

Complementary Relationship in the Analytical Workflow

In practice, qualitative and quantitative analyses form a sequential, complementary workflow. Qualitative assessment typically precedes quantitative measurement, as a component must first be identified before it can be reliably quantified. A typical analytical process involves initial spectral fingerprinting to identify components of interest, followed by method development to establish quantitative parameters for these components, and finally precise measurement of their concentrations [6] [9]. This workflow is particularly crucial in pharmaceutical quality control, where both the identity and purity of drug compounds must be verified.

Table 1: Core Distinctions Between Qualitative and Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis

| Feature | Qualitative Analysis | Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify components, functional groups, and structures [6] | Determine concentration or amount of specific analytes [6] |

| Key Output | Spectral fingerprint, functional group identification, structural elucidation | Concentration values, purity percentages, compositional ratios |

| Common Techniques | FTIR, NMR (for structural elucidation), Raman spectroscopy [8] [7] | UV-Vis, ICP-MS, ICP-OES, NIR with chemometrics [8] [10] |

| Data Interpretation | Pattern matching, spectral library searches, functional group region analysis | Calibration curves, statistical analysis, regression models |

| Typical Workflow Stage | Exploratory research, unknown identification, method development | Quality control, process monitoring, purity assessment |

Essential Spectroscopic Techniques and Their Applications

Modern laboratories employ a diverse array of spectroscopic techniques, each with unique strengths for specific qualitative or quantitative applications. The choice of technique depends on multiple factors including the nature of the analyte, required sensitivity, sample matrix, and the specific information needed (structural versus concentration data) [11].

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy is a versatile technique that provides information about molecular vibrations and chemical bonds. It is widely used for qualitative identification of functional groups and organic compounds through their unique infrared absorption patterns in the mid-IR region (4000-400 cm⁻¹). The fingerprint region (1200-400 cm⁻¹) is particularly useful for identifying specific compounds [7]. With proper calibration and chemometric analysis, FTIR can also be applied to quantitative analysis, such as determining compound levels in plant-based medicines and supplements [9].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei to provide detailed information about molecular structure, dynamics, and chemical environment. It is considered a gold standard for qualitative structural elucidation, particularly for organic molecules and complex natural products [12]. NMR can also be used for quantitative analysis (qNMR) to determine purity and concentration without requiring identical reference standards, making it valuable for pharmaceutical applications [8].

Mass Spectrometry (MS) techniques identify and quantify compounds based on their mass-to-charge ratio. While fundamentally quantitative due to its direct relationship between ion abundance and concentration, MS also provides qualitative information through fragmentation patterns that reveal structural characteristics. Advanced hyphenated techniques like LC-MS/MS and ICP-MS combine separation power with sensitive detection and are particularly valuable for trace analysis in complex matrices [8] [13].

Atomic Spectroscopy techniques, including Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES), are primarily quantitative methods for elemental analysis. They offer exceptional sensitivity for detecting trace metals in pharmaceutical raw materials, finished products, and biological samples [8]. For example, ICP-MS can detect ultra-trace levels of metals interacting with proteins during drug development [8].

UV-Visible Spectroscopy is predominantly used for quantitative analysis due to its straightforward relationship between absorbance and concentration (Beer-Lambert Law). It finds applications in concentration determination of analytes in solution, with microvolume UV-vis spectroscopy recently being applied to quantify nanoplastics in environmental research [14]. While less specific for qualitative identification than vibrational or NMR spectroscopy, UV-Vis can provide some structural information based on chromophore absorption patterns.

Molecular Rotational Resonance (MRR) Spectroscopy is an emerging technique that provides unambiguous structural information on compounds and isomers within mixtures, without requiring pre-analysis separation. MRR can combine the speed of mass spectrometry with the structural information of NMR, making it particularly valuable for chiral analysis and characterizing impurities in pharmaceutical raw materials [12].

Table 2: Technical Comparison of Major Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Primary Qualitative Applications | Primary Quantitative Applications | Typical Sensitivity | Pharmaceutical Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR | Functional group identification, polymorph screening [7] | Content uniformity, coating thickness [9] | µg to mg | Drug stability studies using hierarchical cluster analysis [8] |

| NMR | Structural elucidation, stereochemistry determination [12] | qNMR purity assessment, concentration determination [8] | µg to mg | Monitoring mAb structural changes in formulation [8] |

| MS | Structural characterization, metabolite identification [15] | Bioavailability studies, impurity profiling [8] | pg to ng | SEC-ICP-MS for metal-protein interactions [8] |

| ICP-MS | Elemental identification | Trace metal quantification [8] | ppq to ppt | Metal speciation in cell culture media [8] |

| UV-Vis | Chromophore identification | Concentration measurement, dissolution testing [14] | ng to µg | Inline Protein A affinity chromatography monitoring [8] |

| Raman | Polymorph identification, molecular imaging [8] | Process monitoring, content uniformity [8] | µg to mg | Real-time monitoring of product aggregation during bioprocessing [8] |

| MRR | Isomer differentiation, chiral identification [12] | Enantiomeric excess determination, impurity quantification [12] | ng to µg | Raw material impurity analysis without chromatographic separation [12] |

Advanced and Hyphenated Techniques

The combination of multiple analytical techniques through hyphenation has significantly expanded the capabilities of spectroscopic analysis. Hyphenated techniques such as LC-MS, GC-MS, and LC-NMR combine the separation power of chromatography with the detection specificity of spectroscopy, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis of complex mixtures [15]. These approaches are particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis where samples often contain multiple components in complex matrices.

Advanced implementations of traditional techniques continue to emerge. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) and Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS) dramatically improve sensitivity, enabling detection of low concentration substances and analysis of protein dynamics and aggregation mechanisms [8]. These enhanced techniques provide both qualitative structural information and quantitative concentration data for challenging analytes.

Experimental Protocols: From Theory to Application

Protocol 1: Quantitative Analysis of Total Acidity in Table Grapes Using Vis-NIR Spectroscopy and Si-PLS

This protocol demonstrates a quantitative application of spectroscopy combined with chemometrics for rapid quality assessment, as exemplified in food and agricultural analysis [10].

Principle: Near-infrared radiation interacts with organic molecules through overtone and combination vibrations of fundamental molecular bonds (C-H, O-H, N-H). The resulting spectral signatures can be correlated with chemical properties of interest using multivariate calibration methods.

Materials and Equipment:

- Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (400-1100 nm range)

- Seedless White table grape samples

- Reflective measurement accessory

- Chemometrics software with Si-PLS capability

- Standard laboratory equipment for reference analysis (titration apparatus)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize representative grape samples to create a uniform matrix. Maintain consistent temperature and presentation geometry across all samples.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect diffuse reflectance spectra from each sample across the 400-1100 nm wavelength range. Use consistent instrument parameters (scan number, resolution, gain) for all measurements.

- Reference Method Analysis: Determine actual total acidity (TA) values for all samples using standard titration methods to establish ground truth data for model development.

- Spectral Preprocessing: Apply preprocessing algorithms to reduce scattering effects and enhance spectral features. The first derivative combined with Savitzky-Golay smoothing has been identified as particularly effective for this application [10].

- Variable Selection: Utilize Synergy Interval Partial Least Squares (Si-PLS) to identify optimal spectral subintervals most correlated with TA content. This improves model performance by focusing on informative spectral regions.

- Model Development: Develop PLS regression models using both full-spectrum data and selected subintervals. Validate model performance using cross-validation and independent prediction sets.

- Performance Evaluation: Assess models using correlation coefficients (Rc, Rp), root mean square errors (RMSEC, RMSEP), and residual predictive deviation (RPD). The optimal model for grape TA typically achieves Rc > 0.9 and RPD > 1.8 [10].

Protocol 2: Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Phytochemicals in Herbal Medicines Using FTIR Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the use of FTIR spectroscopy for both identification and quantification of active components in complex plant matrices, relevant to pharmaceutical quality control [9].

Principle: Mid-infrared radiation excites fundamental molecular vibrations, creating absorption spectra that serve as molecular fingerprints. Chemical composition affects these spectra in measurable ways that can be correlated with component concentrations.

Materials and Equipment:

- FTIR spectrometer with deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) detector

- Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) accessory

- Solid herbal medicine samples

- Standard compounds for calibration

- Chemometrics software for multivariate analysis

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Grind herbal samples to fine powder (<100 µm). For ATR measurement, apply uniform pressure to ensure good crystal contact. For transmission measurements, prepare KBr pellets containing precisely weighed sample amounts.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect spectra in the 4000-400 cm⁻¹ range with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution. Accumulate 64 scans per spectrum to improve signal-to-noise ratio. Include background scans under identical conditions.

- Qualitative Analysis:

- Examine functional group region (4000-1200 cm⁻¹) for characteristic absorption bands (O-H, C=O, C-O, etc.)

- Compare fingerprint region (1200-400 cm⁻¹) to reference spectra for identification

- Use second derivative spectroscopy to resolve overlapping bands

- Quantitative Method Development:

- Prepare calibration standards with known concentrations of target phytochemicals

- Apply spectral preprocessing (normalization, derivatives, multiplicative scatter correction)

- Select informative spectral variables using interval PLS (iPLS) or genetic algorithms (GA)

- Develop PLS regression models correlating spectral data with reference concentrations

- Model Validation: Validate using cross-validation and independent test sets. Report RMSEC, RMSEP, RMSEV, and R² values. For example, FTIR quantification of rosmarinic acid in Rosmarini leaves using ATR-IR with MSC and second derivative preprocessing has demonstrated excellent predictive ability [9].

Protocol 3: Quantitative Analysis of Residual Solvents Using Molecular Rotational Resonance (MRR) Spectroscopy

This protocol describes the application of emerging MRR technology for pharmaceutical solvent analysis, offering advantages over traditional GC-based methods [12].

Principle: MRR spectroscopy measures the pure rotational transitions of gas-phase molecules in the microwave region. Each molecule has a unique rotational spectrum that serves as a fingerprint, enabling identification and quantification without separation.

Materials and Equipment:

- Commercial MRR spectrometer

- Headspace autosampler

- Standard solvents and samples

- Data analysis software

Procedure:

- Sample Introduction: Use static headspace sampling to introduce volatile components into the MRR spectrometer. Maintain consistent vial size, sample volume, and equilibration conditions.

- Spectral Acquisition: Acquire broadband rotational spectra in the 2-8 GHz frequency range. The chirped-pulse Fourier-transform microwave technique enables rapid acquisition of the entire bandwidth simultaneously.

- Qualitative Identification: Compare observed rotational transitions to reference spectra for unambiguous identification of solvent molecules, including differentiation of isomers.

- Quantitative Calibration:

- Prepare standard solutions with known concentrations of target solvents

- Measure rotational transition intensities for each standard

- Establish calibration curves relating signal intensity to concentration

- Sample Analysis: Introduce unknown samples and measure rotational transition intensities. Calculate concentrations using established calibration models. For USP <467> Class 2, Procedure C solvents, MRR provides equivalent sensitivity and better quantitative performance compared to GC systems, with dramatically simplified method development [12].

Data Analysis and Chemometrics

Spectral Preprocessing and Variable Selection

The raw spectral data acquired from spectroscopic instruments often contains variations unrelated to the chemical properties of interest. Spectral preprocessing techniques are essential for enhancing the useful information and minimizing confounding factors [9].

Common preprocessing methods include:

- Derivative Spectroscopy: First and second derivatives help resolve overlapping peaks, remove baseline offsets, and enhance small spectral features. The Savitzky-Golay algorithm is widely used for derivative calculation with simultaneous smoothing [13] [10].

- Scatter Correction: Multiplicative Scatter Correction (MSC) and Standard Normal Variate (SNV) transformation correct for light scattering effects caused by particle size differences in solid samples.

- Normalization: Area normalization, vector normalization, or normalization to an internal standard peak (such as potassium thiocyanate in FTIR analysis) corrects for path length or concentration variations [13].

Variable selection is another critical step in chemometric analysis, particularly for quantitative applications. Rather than using entire spectra, selecting specific wavelengths or regions that contain information relevant to the analyte of interest can significantly improve model performance and robustness. Techniques include interval Partial Least Squares (iPLS), Synergy iPLS (Si-PLS), and Genetic Algorithms (GA) [10] [9]. For NIR data, variable selection is more commonly employed than for mid-IR data due to the broader, more overlapping peaks in the NIR region [9].

Multivariate Calibration and Model Validation

Multivariate calibration methods are essential for extracting quantitative information from complex spectroscopic data, particularly when analytes exhibit overlapping spectral features. The most widely used method is Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which finds latent variables that maximize covariance between spectral data and reference concentration values [10]. Advanced variants include interval PLS (iPLS) and synergy interval PLS (Si-PLS), which focus on informative spectral regions.

Other multivariate techniques include:

- Principal Component Regression (PCR): Uses principal components of the spectral data as predictors in regression models.

- Artificial Neural Networks (ANN): Nonlinear modeling approach useful for complex relationships, successfully applied to alkaloid quantification in Coptidis rhizoma [9].

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): Particularly effective for classification problems and nonlinear regression.

Model validation is crucial for ensuring reliable quantitative results. Common validation strategies include:

- Cross-validation: Typically leave-one-out or k-fold cross-validation to optimize model complexity and prevent overfitting.

- Independent test set validation: Using samples not included in model development to assess predictive performance.

- Performance metrics: Reporting correlation coefficients (R², Q²), root mean square errors (RMSEC, RMSECV, RMSEP), and residual predictive deviation (RPD) values [10] [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Thiocyanate (KSCN) | Internal standard for FTIR spectroscopy [13] | High purity grade; used for spectral normalization and quality control |

| Tandem Mass Tag (TMT) Reagents | Isobaric labels for multiplexed quantitative proteomics via LC-MS/MS [13] | 6-plex or 11-plex sets; enable simultaneous quantification of multiple samples |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns | Separation of macromolecules prior to elemental analysis via ICP-MS [8] | Appropriate pore size for target proteins; compatible with aqueous mobile phases |

| Chiral Tag Molecules | Enantiomeric excess determination using MRR spectroscopy [12] | Small, chiral molecules that form diastereomeric complexes with target analytes |

| Pluronic F-127 | Stabilizing agent for liquid crystalline nanoparticles in targeted therapy studies [8] | Pharmaceutical grade; used in specific ratios with glycerol monooleate (GMO) |

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR spectroscopy for structural elucidation and quantification [8] | High deuteration degree (>99.8%); minimal water content |

| Chemometric Software | Multivariate data analysis for quantitative spectroscopic applications [10] [9] | PLS, iPLS, Si-PLS algorithms; spectral preprocessing capabilities |

Workflow Visualization: From Sample to Result

The following diagrams illustrate key workflows in qualitative and quantitative spectroscopic analysis, showing the logical progression from sample preparation to final results.

Spectroscopic techniques provide powerful capabilities for both qualitative identification and quantitative measurement of chemical substances through the fundamental interactions between matter and light. The complementary nature of these approaches enables comprehensive characterization of samples across pharmaceutical, environmental, and materials science applications. As spectroscopic technology continues to advance, with emerging techniques like MRR spectroscopy and enhanced methods such as SERS and TERS, the resolution, sensitivity, and application scope of both qualitative and quantitative analysis continue to expand. By understanding the fundamental principles, appropriate methodologies, and proper data analysis techniques presented in this guide, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful tools to address complex analytical challenges in drug development and beyond.

In the realm of spectroscopic analysis, a spectral fingerprint refers to the unique pattern of electromagnetic radiation that a substance emits or absorbs, serving as a characteristic identifier for that specific element or molecule [16]. These fingerprints arise from the quantized energy transitions within atoms and molecules, producing spectral patterns that are as distinctive as human fingerprints. When light or any form of energy passes through a substance, atoms or molecules absorb specific wavelengths of energy to jump to higher energy states, or emit characteristic wavelengths as they fall to lower states. This pattern, when plotted as a graph of intensity versus wavelength or frequency, creates a spectrum that provides a definitive signature for the substance [16]. The fundamental principle underpinning spectral fingerprints is that every element and molecule possesses a unique arrangement of electrons and energy levels. Consequently, when excited, they interact with electromagnetic radiation in a pattern that is exclusive to their atomic or molecular structure, allowing for unambiguous identification [16].

The concept of the fingerprint extends across various spectroscopic techniques, each probing different types of interactions. In vibrational spectroscopy, such as Raman and FT-IR, the fingerprint region is typically considered to be between 300 to 1900 cm⁻¹ [17]. This region is dominated by complex vibrational modes involving the entire molecule, making it highly sensitive to minor structural differences. This article delves into the core principles of spectral fingerprints, framing their critical role in qualitative identification within the broader context of spectroscopic research, which is often divided into the distinct paradigms of qualitative and quantitative analysis.

Theoretical Foundations

The Physics of Spectral Formation

Spectral fingerprints are a direct manifestation of quantum mechanical principles. The formation of these spectra is governed by the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and the discrete energy levels of atoms and molecules.

- Atomic Spectra: For atoms, the absorption or emission of light occurs when electrons transition between defined energy orbitals. These transitions result in a line spectrum, which appears as a series of sharp, discrete lines at specific wavelengths against a dark background. The well-defined nature of atomic energy levels means these spectra are relatively simple and consist of distinct lines [16].

- Molecular Spectra: Molecules exhibit more complex spectra due to the combination of three types of energy transitions: electronic, vibrational, and rotational. The complex interplay between these energy modes gives rise to a band spectrum, characterized by groups or "bands" of closely spaced lines. The high density of transitions in the fingerprint region creates a unique pattern for each molecule, enabling its identification [16].

The Fingerprint Region in Vibrational Spectroscopy

In vibrational spectroscopy, the fingerprint region (300–1900 cm⁻¹) is particularly crucial for qualitative analysis. A more focused sub-region from 1550 to 1900 cm⁻¹ has been identified as a "fingerprint within a fingerprint" for analyzing Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) [17]. This narrow region is rich with functional group vibrations, such as:

- C=N vibrations (1610–1680 cm⁻¹)

- C=O vibrations (1680–1820 cm⁻¹)

- N=N vibrations (approximately 1580 cm⁻¹) [17]

A key characteristic of this specific region is that common pharmaceutical excipients (inactive ingredients) show no Raman signals, while APIs exhibit strong, unique vibrations. This absence of interference makes it an ideal spectral zone for the unambiguous identification of active compounds in complex drug products [17].

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectroscopic research can be broadly categorized into two complementary approaches: qualitative and quantitative analysis. Understanding their differences and interdependencies is fundamental to designing effective analytical strategies. The table below summarizes the core distinctions.

Table 1: Core Differences Between Qualitative and Quantitative Spectroscopic Research

| Aspect | Qualitative Analysis | Quantitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Identify components; understand composition and structure [18] | Measure concentrations or amounts; test hypotheses [18] |

| Nature of Data | Words, meanings, spectral patterns, and images [18] | Numbers, statistics, and numerical intensities [18] |

| Research Approach | Inductive; explores ideas and forms hypotheses [19] | Deductive; tests predefined hypotheses [19] |

| Data Collection | Focus on in-depth understanding; smaller, purposive samples [19] | Focus on generalizability; larger, representative samples [19] |

| Data Interpretation | Ongoing and tentative, based on thematic analysis [19] | Conclusive, stated with a predetermined degree of certainty using statistics [19] |

The Role of Spectral Fingerprints in Qualitative Analysis

The unique nature of spectral fingerprints makes them the cornerstone of qualitative spectroscopic analysis. A line spectrum is so distinctive for an element that it is often termed its 'fingerprint,' allowing scientists to identify the presence of that element in a sample, whether in a laboratory or a distant star [16]. This non-destructive identification is invaluable across fields, from forensic science, where it can detect drugs of abuse in latent fingerprints [20], to pharmaceutical development, where it ensures the identity of raw materials [17].

The Synergy with Quantitative Analysis

While this article focuses on identification, it is crucial to recognize that modern analytical instruments increasingly blur the line between qualitative and quantitative work. High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (HRMS) exemplifies this trend. Unlike traditional triple-quadrupole MS (QQQ-MS) used for targeted quantification, HRMS can acquire a high-resolution full-scan of all ions in a sample [21]. This provides a global picture, enabling both the quantification of target compounds and the qualitative, untargeted screening for unknown substances within a single analysis. This paradigm shift supports more holistic approaches in systems biology and personalized medicine [21].

Key Spectroscopic Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Raman Spectroscopy for API Identity Testing

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive technique that requires minimal sample preparation, making it ideal for qualitative identification in pharmaceuticals [17].

Experimental Protocol: Leveraging the "Fingerprint in the Fingerprint" Region

- Instrumentation: Use an FT-Raman spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Nicolet NXR 6700) equipped with a 1064 nm laser source and an InGaAs detector. Spectral resolution should be set to 4 cm⁻¹ over a range of 150–3700 cm⁻¹ [17].

- Sample Preparation: For solid dosage forms (tablets, capsules), minimal preparation is needed. The sample is simply placed under the laser objective. Bulk products can even be tested through transparent packaging [17].

- Data Acquisition: Focus the laser on the sample. A laser power of ~0.5 W is suitable for a microstage attachment. Collect the scattered light, which is transferred through an interferometer to the detector.

- Qualitative Analysis:

- Visually inspect the acquired spectrum in the 1550–1900 cm⁻¹ region.

- Compare the spectral signals against a library of known API references.

- Confirm identity by matching unique vibrational signals (e.g., C=O, C=N stretches) specific to the expected API. The absence of signals in this region from excipients simplifies interpretation [17].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| FT-Raman Spectrometer | Core instrument for measuring inelastic scattering of light from molecular vibrations [17]. |

| 1064 nm Laser | Excitation source; this longer wavelength helps reduce fluorescence in samples [17]. |

| Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) Detector | Specialized detector optimized for the near-infrared region, compatible with a 1064 nm laser [17]. |

| Reference Excipients (e.g., Mg Stearate, Lactose) | Used to build spectral libraries and confirm the absence of interfering signals in the API fingerprint region [17]. |

| Standard Spectral Libraries (e.g., USP) | Compendial databases of verified spectra for definitive identification and qualification of instruments [17]. |

| Open-Source Raman Datasets | Publicly available data (e.g., Figshare repositories) containing thousands of spectra for calibration, modeling, and training [22]. |

Detection of Drugs of Abuse in Fingerprints

Raman spectroscopy can be applied in forensics to detect contaminants like drugs of abuse in latent fingerprints, even after they have been developed with powders and lifted with adhesive tapes [20].

Experimental Protocol: Forensic Analysis of Contaminated Fingerprints

- Sample Collection: Latent fingerprints are deposited on a clean surface (e.g., glass slide). To simulate real-world conditions, the subject should handle the drug of abuse prior to deposition.

- Fingerprint Development: Develop the latent print using standard forensic powders (e.g., aluminium flake or magnetic powders) applied with a glass fibre or magnetic applicator [20].

- Recovery: Lift the developed fingerprint using a low-tack clear adhesive film or a hinge lifter, which is then placed on a contrasting backing sheet.

- Spectral Analysis:

- Place the lifted print under a Raman microscope.

- Scan across the fingerprint residue to locate particulate contaminants.

- Obtain Raman spectra from the particles and compare them to reference spectra of pure and seized drug samples (e.g., cocaine, MDMA, amphetamine). The analysis can successfully identify the drug despite the presence of development powder, though locating the particles may take longer [20].

Data Analysis and Interpretation Workflows

The journey from raw spectral data to confident qualitative identification follows a structured workflow. The diagram below illustrates the key decision points and processes in spectral fingerprint analysis.

Diagram 1: Workflow for qualitative spectral identification.

Data Preprocessing

Raw spectral data is often corrupted by noise and baseline offsets, making preprocessing essential before any interpretation. For Raman spectra, common steps include:

- Cropping: Remove non-informative spectral regions (e.g., wavenumbers ≥ 3150 cm⁻¹ which lack Raman activity) [22].

- Baseline Correction: Subtract fluorescent backgrounds and linear offsets. A simple two-point linear correction can be effective, while more advanced algorithms like asymmetric least squares (ALS) or Savitzky-Golay filters may be used for complex baselines [22].

- Scaling/Normalization: Apply techniques like Standard Normal Variate (SNV) or min-max normalization per sample to correct for intensity variations and allow for easier comparison between spectra [22].

Pattern Recognition and Identification

After preprocessing, the core qualitative analysis begins.

- Spectral Library Searching: The processed spectrum is compared against a database of known reference spectra. High similarity (matching peaks and patterns) to a library entry provides a primary identification [17]. Open-source databases are increasingly available to support this task [22].

- Functional Group Analysis: If a definitive library match is not found, or to confirm a match, analysts interpret the spectrum by identifying characteristic peaks. For instance, in the Raman "fingerprint in the fingerprint" region, a peak at 1700 cm⁻¹ would strongly suggest a C=O functional group, narrowing down the possible identities [17].

- Chemometric Analysis: Multivariate statistical methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) are used to classify spectra and identify patterns or outliers within large datasets, which is particularly useful in metabolomics or the analysis of complex mixtures [21].

Spectral fingerprints provide an unparalleled foundation for the qualitative identification of substances at the molecular and atomic levels. The unique and characteristic nature of these patterns allows researchers to definitively identify elements and compounds across diverse fields, from ensuring drug safety to solving crimes. While qualitative identification ("what is it?") and quantitative measurement ("how much is there?") are distinct research pursuits with different methodologies and goals, they are inherently linked. The qualitative identity of a substance is the essential prerequisite for any meaningful quantitative analysis. Modern technological advancements, particularly in high-resolution full-scan techniques, are forging a new paradigm where these two approaches are seamlessly integrated. This synergy promises a more holistic understanding of complex samples, ultimately driving progress in scientific research and its applications.

In scientific research, the analysis of materials via spectroscopy falls into two distinct categories: qualitative and quantitative analysis. Qualitative research seeks to answer questions like "why" and "how," focusing on subjective experiences, motivations, and reasons. In spectroscopy, this translates to identifying which substances are present in a sample based on their absorption characteristics [23]. Conversely, quantitative research uses objective, numerical data to answer questions like "what" and "how much" [23]. The Beer-Lambert Law is the foundational principle that enables the quantitative side of this paradigm, allowing researchers to precisely determine the concentration of a specific substance within a solution [24] [25] [26].

The law synthesizes the historical work of Pierre Bouguer, Johann Heinrich Lambert, and August Beer, formalizing the relationship between light absorption and the properties of an absorbing solution [24]. This whitepaper explores the Beer-Lambert Law's derivation, applications, and limitations, framing it within the broader context of spectroscopic research for drug development professionals and scientists who require robust, quantitative concentration measurements.

Fundamental Principles of the Beer-Lambert Law

Mathematical Formulation

The Beer-Lambert Law provides a direct linear relationship between the concentration of an absorbing species in a solution and the absorbance of light passing through it. It is mathematically expressed as:

Where:

- A is the Absorbance (a dimensionless quantity) [24].

- ε is the Molar Absorptivity (also known as the molar extinction coefficient), with typical units of L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹ [24] [25].

- c is the Concentration of the absorbing species in the solution, with units of mol L⁻¹ [24].

- l is the Path Length, representing the distance light travels through the sample, typically measured in cm [24].

Absorbance itself is defined in terms of the intensity of incident light (I₀) and transmitted light (I): A = log₁₀(I₀/I) [27] [24]

This formula can be rearranged to solve for concentration, which is its most common application in quantitative analysis: c = A / (εl) [24]

Underlying Mechanism and Derivation

The law is derived from the observation that the decrease in light intensity (dI) as it passes through an infinitesimally thin layer (dx) of a solution is proportional to the incident intensity (I) and the concentration of the absorber [24].

The step-by-step derivation is as follows:

- The proportional relationship is established:

-dI/dx ∝ I * cwhich becomes-dI/dx = αIc, where α is an absorption coefficient. - This differential equation is integrated:

∫(dI/I) = -αc ∫dx. - Evaluation of the integral gives:

ln(I) = -αc x + C. - Applying the boundary condition that

I = I₀whenx = 0solves the constant:C = ln(I₀). - This results in:

ln(I) - ln(I₀) = -αc xorln(I/I₀) = -αc x. - Converting from natural logarithm to base-10 logarithm:

log₁₀(I/I₀) = -(α / 2.303) c x. - By defining the molar absorptivity as

ε = α / 2.303and the path length asl = x, we arrive at the classic form:A = log₁₀(I₀/I) = ε c l[24].

The following flowchart illustrates the logical dependencies and relationships between the core concepts of the Beer-Lambert Law.

Quantitative vs. Qualitative Analysis in Spectroscopy

Understanding the distinction between quantitative and qualitative analysis is critical for applying the correct spectroscopic approach. The following table summarizes the key differences.

| Aspect | Quantitative Analysis | Qualitative Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | "How much?" or "What concentration?" [23] | "What is it?" or "Why?" [23] |

| Data Type | Numerical, objective, and countable [23] | Descriptive, subjective, and based on language [23] |

| Role of Beer-Lambert Law | Foundation for calculating precise concentrations [25] [26] | Not directly applicable; used indirectly for identifying peaks |

| Typical Output | Concentration value (e.g., 3.1 × 10⁻⁵ mol L⁻¹) [24] | Identity of a substance (e.g., "bilirubin is present") [27] |

| Data Presentation | Statistical analysis, averages, trends [23] | Grouping into categories and themes [23] |

In practice, these approaches are often combined. A researcher might first use qualitative analysis to identify the absorption spectrum of a protein in a solution and then apply the Beer-Lambert Law for quantitative analysis to determine its concentration throughout a purification process [26].

Experimental Protocols for Quantitative Measurement

Standard Protocol for Concentration Determination

This protocol outlines the steps for using UV-Vis spectroscopy and the Beer-Lambert Law to determine the concentration of an unknown sample, such as a protein or DNA solution.

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the analyte of interest. The concentrations should bracket the expected concentration of the unknown sample [25].

- Selection of Path Length and Wavelength: Choose an appropriate cuvette with a known path length (l), typically 1.0 cm. Using a spectrophotometer, identify the wavelength of maximum absorption (λ_max) for the analyte [24] [25].

- Measurement of Absorbance: Measure the absorbance (A) of each standard solution at the predetermined λ_max. Also, measure the absorbance of the unknown sample at the same wavelength [25].

- Construction of Calibration Curve: Plot a graph of the measured absorbance (y-axis) against the known concentration (x-axis) for the standard solutions. The Beer-Lambert Law predicts this will be a straight line through the origin [24] [25].

- Determination of Molar Absorptivity: The slope of the linear calibration curve is equal to the product of the molar absorptivity and the path length (slope = εl). If the path length is known, ε can be calculated [24].

- Calculation of Unknown Concentration: Determine the concentration of the unknown sample by either reading its value from the calibration curve using its measured absorbance or by direct calculation using the formula

c = A / (εl)if ε is known [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful quantitative spectroscopy requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details key items and their functions.

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer / USB Spectrometer | Instrument that measures the intensity of light transmitted through a sample, enabling absorbance calculation [25]. |

| Cuvette | A container, typically with a standard path length (e.g., 1 cm), that holds the liquid sample during measurement [24]. |

| Standard (Analyte) of Known Purity | A high-purity reference material used to prepare standard solutions for constructing the calibration curve [25]. |

| Appropriate Solvent | The liquid in which the analyte is dissolved; it must be transparent at the wavelengths of measurement and not react with the analyte [24]. |

| Monomochromatic Light Source | A light source that emits light of a single wavelength (or a narrow band), which is essential for the Beer-Lambert Law to hold true [24]. |

Applications, Limitations, and Data Presentation

Key Applications in Research and Industry

The Beer-Lambert Law is a cornerstone of quantitative analysis across diverse scientific fields.

- Pharmaceutical Analysis and Drug Development: Used to determine the concentration of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in solutions during research, quality control, and stability testing [26].

- Biological Assays: Routinely employed to quantify biomolecules such as proteins (e.g., using the Bradford or Lowry assays) and nucleic acids (DNA/RNA) in molecular biology laboratories [26].

- Environmental Monitoring: Applied to measure the concentration of pollutants, such as nitrates and heavy metals, in water and air samples [26].

- Clinical Diagnostics: Used in automated analyzers to measure concentrations of specific analytes in blood samples, such as bilirubin [27] [24].

Limitations and Deviations from the Law

Despite its utility, the Beer-Lambert Law has well-defined limitations. Deviations from linearity occur under specific conditions, which are summarized in the following flowchart.

The primary limitations include:

- High Concentrations: At high concentrations (typically > 10 mM), electrostatic interactions between molecules can alter the molar absorptivity, and changes in refractive index lead to non-linearity [27] [24] [26].

- Chemical Changes: The law assumes no chemical changes during measurement. Association, dissociation, or chemical reactions of the absorbing species will cause deviations [24].

- Non-Monochromatic Light: The law requires monochromatic light. The use of polychromatic light, especially with broad-band light sources, can lead to inaccuracies [24].

- Sample Issues: Scattering of light due to particulates or turbidity in the sample will cause apparent absorption and violate the law's assumptions [24] [26].

Quantitative Data and Workflow Table

The following table consolidates key quantitative data and steps involved in applying the Beer-Lambert Law, aiding in experimental planning and analysis.

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Units | Example Value | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absorbance | A | Dimensionless | 0.37, 0.81, 1.0 [24] | Calculated as log₁₀(I₀/I); should generally be between 0.1 and 1.0 for optimal accuracy. |

| Molar Absorptivity | ε | L mol⁻¹ cm⁻¹ | 2371, 5342, 8850 [27] [24] | Substance- and wavelength-specific constant; determined experimentally. |

| Concentration | c | mol L⁻¹ (M) | 3.1 × 10⁻⁵ M, 90 nM [24] | The target variable in quantitative analysis; law is best for dilute solutions. |

| Path Length | l | cm | 1.00, 3.00, 0.002 [27] [24] | Standard cuvettes are 1.0 cm; a known, fixed length is critical. |

| Transmitted Light | I | Relative Intensity | - | I/I₀ = 10⁻ᴬ; an absorbance of 1 means 10% of light is transmitted [24]. |

The Beer-Lambert Law remains an indispensable tool in the scientist's arsenal, providing a direct and robust method for quantitative concentration measurement. Its formulation, A = εcl, serves as the critical bridge between the qualitative identification of substances via their absorption spectra and the precise numerical data required in fields from drug development to environmental science. While its limitations must be respected, understanding its principles and correct application allows researchers to reliably answer the fundamental quantitative question, "How much is present?". As spectroscopic technologies advance, the Beer-Lambert Law continues to underpin the rigorous quantitative analysis that drives scientific discovery and innovation.

Spectroscopic techniques form the cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, enabling researchers to elucidate molecular structure, identify chemical substances, and determine their quantities with precision. These techniques measure the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation, producing signals that can be interpreted for both qualitative and quantitative analysis. Qualitative analysis focuses on identifying chemical entities based on their unique spectral patterns, while quantitative analysis measures the concentration or amount of specific components in a sample. Within pharmaceutical research and development, these methodologies play indispensable roles in drug discovery, quality control, and clinical application, providing critical analytical data that guides scientific decision-making [28] [29].

This technical guide provides a comprehensive overview of four principal spectroscopic techniques: UV-Vis, IR, NMR, and Mass Spectrometry. Each technique offers complementary capabilities, with varying strengths in structural elucidation, sensitivity, and quantitative precision. The content is framed within the broader research context of understanding the distinctions between qualitative and quantitative spectroscopic analysis, addressing the specific needs of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who rely on these methodologies in their investigative work.

Fundamental Principles: Qualitative vs. Quantitative Analysis

In spectroscopic analysis, qualitative and quantitative approaches serve distinct but complementary purposes, each with specific methodological requirements and challenges.

Qualitative analysis aims to identify substances based on their characteristic spectral patterns. In UV-Vis spectroscopy, this involves observing absorption maxima at specific wavelengths, while IR spectroscopy identifies functional groups through their unique vibrational frequencies in the fingerprint region (1200 to 700 cm⁻¹) [30] [31]. Mass spectrometry provides qualitative information through mass-to-charge ratios and fragmentation patterns, and NMR spectroscopy offers detailed structural insights based on chemical shifts, coupling constants, and integration patterns [28] [32].

Quantitative analysis measures the concentration of specific analytes in a sample, relying on the relationship between signal intensity and analyte amount. The fundamental principle for UV-Vis quantification is the Beer-Lambert law, which states that absorbance is proportional to concentration [33]. In mass spectrometry, quantitative capabilities have been significantly enhanced through technological improvements addressing instrument-related and sample-related factors that affect measurement precision [28]. Quantitative NMR (qNMR) exploits the direct proportionality between signal area and nucleus concentration, providing a primary ratio method without compound-specific calibration [32].

Each technique faces distinct challenges in quantitative applications. For MS, these include ion suppression, sample matrix effects, and the need for appropriate internal standards [28]. IR spectroscopy requires careful baseline correction and path length determination, while UV-Vis can suffer from interferences in complex mixtures [33] [31].

UV-Visible Spectroscopy

Principles and Applications

UV-Visible spectroscopy measures electronic transitions from lower energy molecular orbitals to higher energy ones when molecules absorb ultraviolet or visible light. The fundamental principle governing its quantitative application is the Beer-Lambert law, which establishes a linear relationship between absorbance and analyte concentration: A = εbc, where A is absorbance, ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient, b is the path length, and c is the concentration [33]. This technique operates primarily in the 200-700 nm wavelength range, making it suitable for analyzing conjugated systems, aromatic compounds, and inorganic complexes [33].

In pharmaceutical analysis, UV-Vis spectroscopy serves as a rapid, cost-effective method for both qualitative and quantitative drug analysis. Qualitatively, the position and shape of absorption spectra provide information about chromophores in drug molecules. Quantitatively, it enables determination of drug concentrations in formulations through direct measurement or after derivatization to enhance sensitivity or selectivity [33]. The technique's simplicity, ease of handling, and relatively low cost contribute to its widespread adoption in quality control laboratories.

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Prepare appropriate standard solutions of known concentrations using high-purity solvents

- Ensure sample compatibility with the solvent system (common solvents include water, methanol, and hexane)

- Filter turbid samples if necessary to eliminate light scattering

- Employ matched quartz or glass cuvettes depending on the wavelength range

- Maintain consistent temperature during analysis to prevent refractive index changes

Quantitative Analysis Methodology:

- Perform wavelength scanning to determine λmax of the analyte

- Prepare a calibration curve using at least five standard concentrations

- Measure absorbance of unknown samples at the predetermined λmax

- Calculate concentration using the linear regression equation from the calibration curve

- Validate method performance using quality control samples

For cell-in cell-out method, the same cuvette is used for all measurements to eliminate cell-to-cell variation, while the baseline method selects a suitable absorption band and measures P0 and P values for log (P0/P) calculation [31]. Method validation should establish linearity, accuracy, precision, and limit of quantification according to regulatory guidelines.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy

Principles and Applications

Infrared spectroscopy probes molecular vibrational transitions, providing information about functional groups and molecular structure. When incident infrared radiation is applied to a sample, part is absorbed by molecules while the remainder is transmitted. The resulting spectrum represents a molecular fingerprint unique to each compound, with the region between 1200-700 cm⁻¹ being particularly discriminative [30] [31]. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy has largely displaced dispersive instruments, offering improved speed, sensitivity, and wavelength accuracy.

IR spectroscopy delivers diverse applications in qualitative analysis, including identification of organic and inorganic compounds, detection of impurities, study of reaction progress through monitoring functional group transformations, and investigation of structural features like isomerism and tautomerism [31]. In quantitative analysis, IR measures specific functional group absorption bands related to analyte concentration, though it generally offers lower sensitivity and precision compared to UV-Vis or NMR techniques.

Experimental Protocols

Sample Preparation Methods:

- KBr Pellet Technique: Grind 1-2 mg sample with 200-400 mg dried potassium bromide; press under high pressure to form transparent pellet

- Solution Method: Dissolve sample in appropriate non-aqueous solvent (e.g., chloroform, CCl₄) using sealed liquid cells with fixed path lengths

- ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance): Place sample directly on ATR crystal requiring minimal preparation; ideal for solids, liquids, and gels

Quantitative Analysis Workflow:

- Select an absorption band unique to the analyte with minimal interference

- Prepare standard solutions spanning the expected concentration range

- Collect spectra using consistent instrumental parameters (resolution, scans)

- Measure absorbance using baseline method (connect spectrum points on either side of absorption peak)

- Construct calibration curve plotting absorbance versus concentration

- Apply derivative spectroscopy (first or second derivative) to enhance resolution of overlapping bands [30]

For industrial applications like analysis of multilayered polymeric films or heterogeneous catalysts, diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) provides rapid characterization without extensive sample preparation [31].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

Principles and Applications

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance spectroscopy exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei (e.g., ¹H, ¹³C, ¹⁹F, ³¹P) when placed in a strong magnetic field. The fundamental principle of quantitative NMR (qNMR) rests on the direct proportionality between the integrated signal area and the number of nuclei generating that signal, without requiring identical response factors for different compounds [32]. This unique attribute distinguishes qNMR from other quantitative techniques and enables its application to diverse compound classes without compound-specific calibration.

qNMR has gained significant traction in pharmaceutical analysis for purity determination of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), quantitation of natural products, analysis of forensic samples, and food science applications [32]. The technique provides exceptionally rich structural information concurrently with quantitative data, allowing both identification and quantification in a single experiment. With proper experimental controls, qNMR can achieve accuracy with errors of less than 2%, making it suitable for high-precision applications like reference standard qualification [32].

qNMR Methodologies

Internal Standard Method:

- Select certified reference standard with high purity and minimal spectral interference

- Precisely weigh analyte and reference standard using calibrated analytical balance

- Co-dissolve in appropriate deuterated solvent ensuring complete dissolution

- Acquire spectrum with optimized parameters (relaxation delay ≥5×T1, 90° pulse angle)

- Integrate target signals from analyte and reference standard

- Calculate purity or concentration using: Cₓ = (Iₓ/Iᵣ) × (Nᵣ/Nₓ) × (Mₓ/Mᵣ) × mᵣ/mₓ × Pᵣ Where Cₓ is analyte concentration, I is integral, N is number of nuclei, M is molecular weight, m is mass, and P is purity [32]

Absolute Integral Method:

- Establish "Concentration Conversion Factor" (CCF) using reference standard of known concentration

- Apply same CCF to determine chemical components in future experiments under identical conditions

- Utilize artificial signals like ERETIC or QUANTAS as internal references

- Employ residual protonated solvent signals (e.g., DMSO-d5H) as concentration reference

The experimental workflow for qNMR requires careful attention to data acquisition parameters, particularly sufficient relaxation delay to ensure complete longitudinal relaxation between scans, and appropriate signal-to-noise ratio (typically >250:1) for accurate integration [32].

Diagram 1: qNMR Experimental Workflow

Mass Spectrometry

Principles and Applications

Mass spectrometry separates ionized chemical species based on their mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) in the gas phase, providing both qualitative identification through exact mass measurement and fragmentation patterns, and quantitative analysis through measurement of ion abundance [28]. The technique involves three fundamental steps: ionization of analyte molecules in the ion source, separation of ions by mass analyzers according to m/z ratios, and detection of separated ions to produce mass spectra [28]. The development of electrospray ionization (ESI) and other soft ionization techniques has dramatically expanded MS applications to biomacromolecules and complex biological samples.

In pharmaceutical research, MS has become a standard bioanalytical technique with extensive applications in quantitative and qualitative analysis. It supports drug discovery and development by elucidating pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and toxicity profiles of new molecular entities, natural products, metabolites, and biomarkers [29]. The coupling of MS with separation techniques like liquid chromatography (LC-MS) and capillary electrophoresis (CE-MS) has significantly enhanced its quantitative capabilities in complex matrices.

Quantitative MS Challenges and Protocols

Key Challenges in Quantitative MS:

- Ion suppression effects from co-eluting matrix components

- Variable ionization efficiencies between different analytes

- Requirement for appropriate internal standards (often stable isotope-labeled analogs)

- Instrumental drift and signal instability over time

- Need for expert knowledge in data interpretation [28]

Sample Preparation Workflow:

- Extract analytes from biological matrix (plasma, urine, tissue homogenate)

- Incorporate internal standard early in preparation to correct for losses

- Employ purification techniques like protein precipitation, liquid-liquid extraction, or solid-phase extraction

- Reconstitute in MS-compatible solvent system

- Optionally employ chemical derivatization to enhance ionization efficiency

LC-MS/MS Quantitative Protocol:

- Perform chromatographic separation to reduce matrix effects

- Optimize MS parameters for multiple reaction monitoring (MRM)

- Establish calibration curve using matrix-matched standards

- Include quality control samples at low, medium, and high concentrations

- Acquire data using validated method with appropriate acceptance criteria

- Process data using peak area ratios (analyte/internal standard) against calibration curve

For absolute quantification of proteins or metabolites, the gold standard approach employs stable isotope-labeled internal standards with identical chemical properties but distinct mass signatures [34]. This approach corrects for variability in sample preparation, ionization efficiency, and matrix effects.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

Table 1: Comparison of Key Spectroscopic Techniques for Quantitative Analysis

| Technique | Quantitative Principle | Linear Range | Sensitivity | Key Applications | Primary Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis | Beer-Lambert Law (A=εbc) | 3-4 orders of magnitude | Moderate (μM-nM) | Drug purity, dissolution testing, content uniformity | Interferences from chromophores, limited to UV-absorbing species |

| IR | Beer-Lambert Law (band intensity) | 1-2 orders of magnitude | Low (mg levels) | Polymer composition, functional group quantification, industrial QC | Water interference, weak absorption, scattering effects |

| NMR | Signal area proportional to nuclei number | 2-3 orders of magnitude | Low (mM-μM) | API purity, natural product quantitation, metabolic profiling | Low sensitivity, high instrument cost, specialized training |

| Mass Spectrometry | Ion abundance proportional to concentration | 4-6 orders of magnitude | High (pM-fM) | Biomarker validation, PK/PD studies, metabolomics, proteomics | Matrix effects, ion suppression, requires internal standards |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Technique | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deuterated Solvents | NMR | Provides locking signal and solvent environment without interfering proton signals | DMSO-d6 for polar compounds, CDCl3 for non-polar compounds |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | MS | Internal standards for accurate quantification | ¹³C/¹⁵N-labeled peptides in proteomics, d3-methyl labeled pharmaceuticals |

| KBr Powder | IR | Transparent matrix for pellet preparation | Solid sample analysis for organic compounds |

| Reference Standards | qNMR | Certified materials for quantitative calibration | Purity determination of APIs, forensic analysis |

| HPLC-grade Solvents | UV-Vis/LC-MS | High purity solvents for mobile phase and sample preparation | Minimizing background interference in sensitive analyses |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

The integration of spectroscopic techniques with separation methods and computational approaches continues to expand their applications in pharmaceutical research. Hyphenated techniques like LC-MS, GC-IR, and CE-NMR combine separation power with detection specificity, enabling comprehensive analysis of complex mixtures [30] [34]. In drug development, MS-based techniques are increasingly applied to biomarker discovery and validation, providing crucial insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic responses [34].

Recent advancements in quantitative mass spectrometry have focused on addressing challenges related to sample preparation, ionization interferences, and data processing [28]. The development of novel instrumentation with improved sensitivity and resolution, coupled with advanced computational algorithms for data management and mining, continues to enhance the quantitative capabilities of MS platforms [34]. Similarly, methodological improvements in qNMR have positioned it as a valuable metrological tool for purity assignment of reference materials, with potential to complement or even replace traditional chromatography-based approaches in specific applications [32].

Future developments in spectroscopic analysis will likely focus on increasing automation and throughput while maintaining analytical precision, enhancing capabilities for analyzing increasingly complex samples, and improving data processing algorithms to extract meaningful information from large multivariate datasets. The continuing evolution of these techniques will further solidify their essential role in pharmaceutical research and quality control, enabling more comprehensive characterization of drug substances and products throughout their development lifecycle.

Techniques in Action: Selecting and Applying Spectroscopic Methods for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis

Qualitative analysis is a fundamental process in analytical chemistry focused on identifying the chemical composition of a sample, determining which elements or functional groups are present rather than measuring their precise quantities [35]. This approach stands in contrast to quantitative analysis, which deals with measurable quantities and numerical data to determine how much of a particular substance exists [36]. In the context of spectroscopic analysis, qualitative methodologies provide researchers with critical information about molecular structure, functional groups, and elemental composition, forming the essential first step in characterizing unknown compounds, particularly in natural product discovery and drug development [35].