Quantifying Light Transmittance Restoration: A Pre- and Post-Cleaning Analysis for Laboratory and Clinical Environments

This article provides a scientific framework for quantifying the impact of window cleaning on light transmittance, a critical yet often overlooked variable in biomedical research and drug development.

Quantifying Light Transmittance Restoration: A Pre- and Post-Cleaning Analysis for Laboratory and Clinical Environments

Abstract

This article provides a scientific framework for quantifying the impact of window cleaning on light transmittance, a critical yet often overlooked variable in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of light transmission, details standardized methodologies for its measurement before and after cleaning, and offers protocols for optimizing cleaning procedures to ensure experimental consistency. By presenting a comparative analysis of transmittance data, this work underscores the direct implications for UV/VIS spectroscopy, vitamin D research, circadian rhythm studies, and the integrity of light-sensitive assays, ultimately advocating for the integration of window cleanliness into laboratory quality control systems.

The Critical Link Between Window Clarity and Scientific Data Integrity

Defining Light Transmittance and Its Relevance to Biomedical Assays

Light transmittance, defined as the percentage of incident light that passes through a material, serves as a fundamental optical property with critical applications across biomedical assays. This measurement quantifies the fraction of incident light (I) successfully transmitted through a sample compared to the initial light intensity (I₀), expressed as T = I/I₀ [1]. In laboratory science, transmittance provides the foundation for quantifying molecular concentrations, assessing material properties, and monitoring biological interactions. This review examines the operational principles of transmittance measurement, compares its applications across diverse biomedical platforms, and evaluates experimental data demonstrating how material characteristics and environmental factors influence transmission properties. Within the broader context of optical clarity research, exemplified by window cleaning studies that optimize light passage, understanding transmittance principles enables researchers to enhance assay sensitivity, reduce interference, and improve diagnostic accuracy in biomedical applications ranging from pharmaceutical quality control to diagnostic testing.

Light transmittance represents a fundamental optical property with critical importance across numerous scientific disciplines, particularly in biomedical assay development and diagnostics. Transmittance is quantitatively defined as the ratio of light intensity passing through a medium to the initial incident light intensity, typically expressed as a percentage [1]. This measurement provides essential information about material transparency, composition, and optical density.

The fundamental relationship between transmittance and absorbance follows logarithmic principles, where absorbance (A) equals -log₁₀(T), with T representing transmittance as a decimal value [2] [3]. This inverse relationship forms the theoretical foundation for the Beer-Lambert law, which establishes that absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length of light through the material [3]. This principle enables researchers to quantify molecular concentrations in solution, making transmittance measurements indispensable across life science applications.

Different materials interact with light through distinct mechanisms, requiring specialized measurement approaches. Regular transmittance occurs when parallel light rays pass through materials with smooth surfaces and uniform internal structure without scattering, maintaining their directional integrity [2]. In contrast, diffuse transmittance happens when light scatters in multiple directions upon passing through materials with rough surfaces or non-uniform internal composition, such as frosted glass or biological tissues [2]. These differential interactions necessitate specific instrumentation; regular transmittance materials require parallel light path systems like the LS116 transmittance meter, while diffuse transmittance materials need integrating sphere technologies that collect scattered light [2].

Technical Measurement Approaches in Biomedical Applications

Accurate transmittance measurement requires specialized instrumentation tailored to specific material properties and application requirements. Spectrophotometers serve as the primary tools for optical analysis across ultraviolet, visible, and infrared spectral regions [1]. These instruments operate by generating specific wavelength radiation, passing this light through samples, detecting transmitted intensity, and calculating transmittance ratios through integrated software systems.

Specialized Measurement Systems

For materials exhibiting significant light scattering, standard spectrophotometry proves insufficient. Integrating spheres provide enhanced accuracy for such applications through hollow spherical chambers with highly reflective interior coatings that collect and redirect scattered light toward detection systems [1]. This approach ensures comprehensive detection of transmitted photons that would otherwise escape measurement in conventional systems.

Laser-based systems offer exceptional precision for applications requiring specific wavelength analysis, utilizing monochromatic laser sources to detect minute transmission variations [1]. While these systems provide superior accuracy at targeted wavelengths, their limited spectral coverage reduces suitability for applications requiring broad spectral analysis. Industrial applications increasingly employ inline process monitoring systems that incorporate transmittance sensors directly into manufacturing workflows, enabling real-time optical property assessment without disrupting production [1].

Critical Measurement Considerations

Multiple factors influence transmittance measurement accuracy, requiring meticulous methodological control. Sample preparation demands particular attention, as surface contaminants including fingerprints, dust particles, or minor scratches can significantly distort readings [1]. Proper cleaning protocols, appropriate containment vessels, and consistent sample positioning establish fundamental prerequisites for measurement precision.

Instrument calibration requires regular verification against certified reference materials, with modern systems typically necessitating both baseline (0% transmittance) and reference (100% transmittance) standardization [1]. Environmental variables including temperature fluctuations and humidity variations can alter material properties and instrument performance, necessitating controlled laboratory conditions for optimal consistency [1]. Wavelength selection significantly influences recorded values, as materials may exhibit dramatically different transmission characteristics across spectral regions, making comprehensive characterization dependent on appropriate wavelength range selection [1].

Table 1: Transmittance Measurement Techniques and Applications

| Technique | Principle | Optimal Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometry | Measures light transmission across specific wavelengths | Protein/nucleic acid quantification, concentration determination | Limited accuracy for highly scattering samples |

| Integrating Sphere | Collects scattered light using reflective spherical chamber | Diffuse materials, biological tissues, turbid solutions | Higher cost, complex operation |

| Laser-Based Systems | Utilizes monochromatic laser light for precise measurement | High-precision applications, specific wavelength analysis | Limited spectral coverage |

| Inline Process Monitoring | Incorporates sensors directly into production lines | Industrial quality control, manufacturing processes | Limited measurement flexibility |

Comparative Analysis of Transmittance in Biomedical Materials

Material composition and surface characteristics significantly influence light transmission properties, with direct implications for biomedical device performance and experimental accuracy. Research demonstrates that surface roughness dramatically affects both staining susceptibility and cleaning efficacy in medical polymers. Studies on orthodontic retainers revealed that rough-surfaced materials (approximately 10.5 μm surface roughness) exhibited significantly greater staining and more challenging destaining compared to smooth surfaces, directly impacting light transmittance restoration after cleaning protocols [4].

Dental composite research provides additional insights into material-specific transmission characteristics. Comparative analysis of nanofilled, supra-nanofilled, microfilled, and microhybrid composites demonstrated that supra-nanofilled composites most closely approximated natural dental tissue transmittance when layered at 1.2mm thickness [5]. Critically, at reduced thicknesses (0.3mm), none of the tested composites matched natural tissue transmission, highlighting the complex relationship between material composition, layer dimensions, and optical properties [5]. These findings have direct implications for biomedical devices requiring specific optical characteristics.

Quantitative Transmittance Comparisons

Table 2: Light Transmittance Properties of Biomedical Materials

| Material Type | Application Context | Transmittance Characteristics | Impact Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethane Retainers | Orthodontic devices | Similar to copolyester initially; significantly affected by surface roughness | Coffee/tea staining reduced transmittance; rough surfaces harder to clean |

| Copolyester Retainers | Orthodontic devices | Comparable to polyurethane; better destaining capability on smooth surfaces | Surface texture critical for stain removal efficacy |

| Supra-nanofilled Composite | Dental restoration | Closest match to natural tooth transmittance at 1.2mm thickness | 78-82% ceramic/silica filler content; layer thickness critical |

| Microhybrid Composite | Dental restoration | Required thicker layers to approximate natural tooth transmittance | 79% barium glass/silica filler; less accurate at thin layers |

| Natural Dental Tissue | Biological reference | Standard for dental material comparison | Thinner enamel layers (0.3mm) showed higher transmittance |

Automated analytical systems leveraging transmittance principles demonstrate significant advantages over traditional methods. Centrifugal microfluidic disc platforms for light transmission aggregometry (LTA) achieve highly reproducible results (3.2% coefficient of variation) with minimal blood volume (<1 mL) and reduced processing time (<25 minutes) [6]. This performance improvement over conventional LTA stems from automated reaction steps, reduced human intervention, and specialized microfluidic chamber designs that minimize platelet instability effects [6].

Experimental Protocols for Transmittance Assessment

Standardized methodologies enable accurate comparison of transmittance across materials and experimental conditions. The following protocols represent established approaches for quantifying light transmission in biomedical contexts.

Spectrophotometric Analysis of Material Transmittance

Objective: Quantify percentage light transmittance through transparent or translucent biomedical materials across visible spectrum (380-780nm).

Materials and Reagents:

- Spectrometer with integrating sphere capability (e.g., Ocean Optics systems)

- Standardized light source

- Sample materials cut to standardized dimensions (e.g., 50.8mm × 12.7mm × 1.0mm)

- Reference materials for calibration

- Controlled immersion solutions (coffee, tea, wine, artificial saliva as appropriate)

Methodology:

- Instrument calibration using baseline (0% transmittance) and reference (100% transmittance) standards

- Sample positioning ensuring consistent orientation and placement

- Light intensity measurement at 1nm intervals across target spectrum

- Transmittance calculation as T = (I/I₀) × 100%, where I represents transmitted light intensity and I₀ incident light intensity

- Triplicate measurements per sample with positional consistency

Data Analysis:

- Calculate mean transmittance percentages across target wavelength range

- Determine changes in transmittance (ΔT) relative to baseline measurements

- Statistical analysis via ANOVA with post-hoc multiple comparison testing (significance at p < 0.05)

This methodology was successfully implemented in dental material research, demonstrating that 1.2mm thick enamel layers of supra-nanofilled composite most closely approximated natural tooth transmittance [5].

Automated Light Transmission Aggregometry Protocol

Objective: Assess platelet function through light transmittance changes in response to agonist stimulation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Centrifugal microfluidic disc platform

- Whole blood samples (<1 mL)

- Platelet agonists (ADP, collagen, epinephrine)

- Reference standards for calibration

- Isotonic buffer solutions

Methodology:

- Blood collection with appropriate anticoagulants

- Sample loading onto microfluidic disc chambers

- Centrifugation to separate platelet-rich plasma

- Automated agonist introduction and mixing

- Continuous light transmittance monitoring at 37°C

- Data acquisition over 25-minute period

Data Analysis:

- Baseline transmittance establishment with platelet-poor plasma as 100% reference

- Platelet-rich plasma baseline transmittance as 0% reference

- Aggregation quantification as percentage increase in light transmittance

- Coefficient of variation calculation to assess reproducibility [6]

This automated approach demonstrates superior reproducibility (3.2% CV) compared to traditional LTA, with reduced labor requirements and minimal sample volumes [6].

Research Reagent Solutions for Transmittance Assays

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Transmittance Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| LS116 Transmittance Meter | Measures regular transmittance in transparent materials | Quality control of optical components, clear polymers | Parallel light path design; ±1% accuracy; suitable for high-transmission materials |

| LS117 Optical Density Meter | Quantifies diffuse transmittance in scattering materials | Analysis of frosted surfaces, biological tissues | Integrating sphere principle; replaces traditional sphere test methods |

| Microplate Readers with UV/vis Spectrometer | High-throughput absorbance/transmittance measurements | Protein quantification, microbial growth assays, ELISA | 96- to 1536-well formats; path length correction capability |

| Centrifugal Microfluidic Discs | Automated sample processing and transmittance measurement | Platelet function tests, hematological analysis | <1 mL sample volume; <25 minute processing; 3.2% CV reproducibility |

| Certified Reference Materials | Instrument calibration for measurement accuracy | Quality assurance, method validation | Required for both 0% and 100% transmittance calibration |

| Standardized Staining Solutions | Material degradation and fouling assessment | Dental material testing, implant surface analysis | Coffee, tea, wine solutions at standardized concentrations |

Signaling Pathways and Technology Workflows

Transmittance-based detection enables monitoring of numerous cellular signaling pathways and molecular interactions. The following diagrams visualize key assay principles and technology workflows.

Diagram 1: Cellular Signaling and TR-FRET Detection Pathways. (Left) Transmittance changes can monitor phenotypic cellular responses throughout signaling cascades. (Right) TR-FRET detects molecular interactions through distance-dependent energy transfer between donor and acceptor fluorophores, with time-resolved measurement reducing background interference [7].

Diagram 2: Transmittance Measurement Workflow and Applications. Fundamental process for quantifying light transmission through materials, with resulting data supporting diverse biomedical applications including platelet function assessment, microbial growth monitoring, and molecular quantification [6] [3].

Light transmittance measurement represents a cornerstone analytical technique with diverse and critical applications across biomedical research and clinical diagnostics. From fundamental material characterization to sophisticated cellular function assessment, transmittance-based methodologies provide robust, quantifiable data supporting scientific advancement and clinical decision-making. The comparative data presented demonstrates how material composition, surface characteristics, and measurement technologies collectively influence transmission properties, with direct implications for assay performance and device functionality.

Automated platforms utilizing transmittance principles, including centrifugal microfluidic systems and TR-FRET technologies, demonstrate significant advantages over traditional methods through enhanced reproducibility, reduced sample requirements, and decreased processing times. These advancements highlight the continuing evolution of transmittance-based methodologies toward greater precision and efficiency. As biomedical research increasingly demands high-throughput screening and precise quantification, transmittance measurement technologies will continue to provide indispensable tools for scientific discovery and diagnostic innovation.

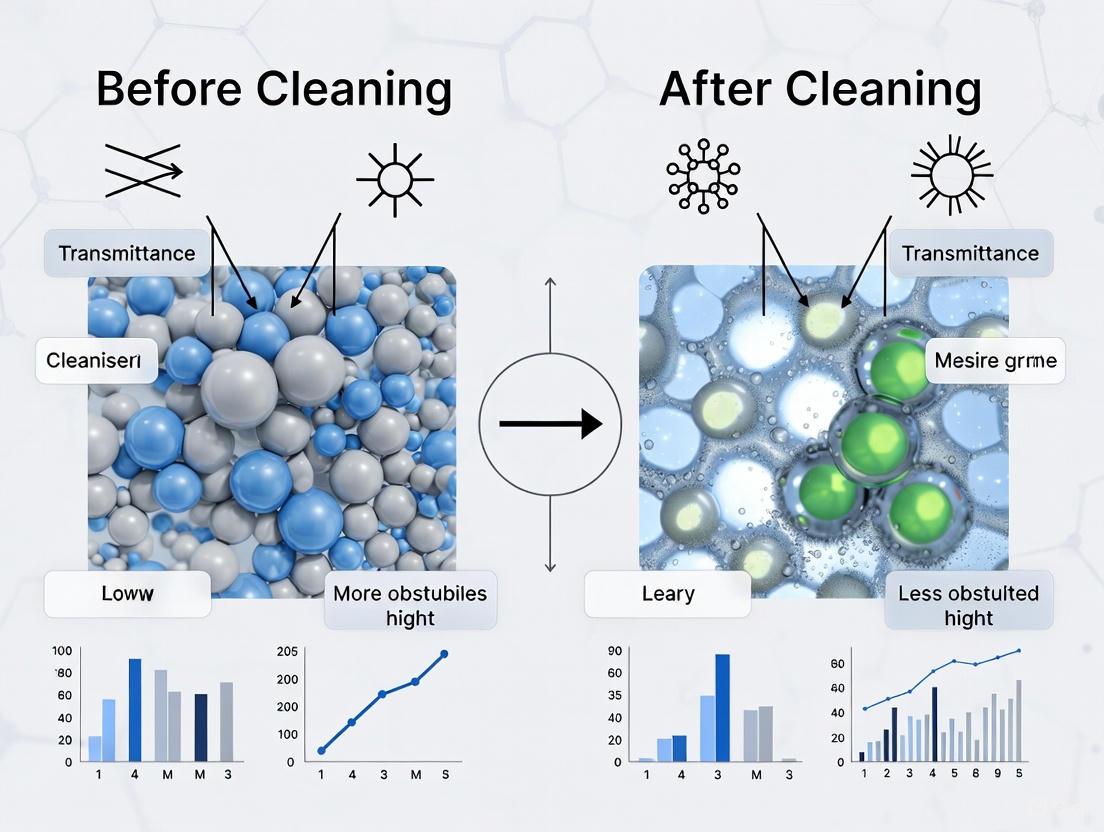

In scientific research, particularly in fields requiring precise optical measurements, window grime is often an uncontrolled variable that can significantly compromise data integrity. Contaminants act as an interferent, altering the intensity and spectral quality of transmitted light through the mechanisms of scattering and absorption. This guide objectively compares the performance of clean versus contaminated glass surfaces by synthesizing experimental data on light transmittance. The findings underscore the critical importance of standardized window cleaning protocols in research environments to ensure measurement validity and experimental reproducibility.

The Core Scientific Principles: Transmission, Scattering, and Absorption

When light encounters a surface like a window, its path and properties are altered. A clean, transparent window is designed to allow maximum transmittance—the percentage of incoming light that passes through a material [8]. Contaminants (grime) on the window surface introduce microscopic and macroscopic particles that disrupt this process via two primary mechanisms:

- Light Scattering: Grime particles deflect light from its original path. This diffusion reduces the intensity of light transmitted directly through the window and can introduce optical noise.

- Light Absorption: Pigments and chemical compounds within grime absorb specific wavelengths of light, diminishing overall light intensity and altering the spectral composition of the transmitted light.

The cumulative effect of these mechanisms is a measurable reduction in light transmittance, which can act as an uncontrolled variable in any experiment reliant on precise lighting or optical measurements.

Quantitative Comparison: Transmittance Performance of Clean vs. Contaminated Surfaces

The following tables synthesize experimental data to compare the performance of clean and contaminated glass, and to highlight the impact of different glass types.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Clean vs. Contaminated Glass

| Performance Metric | Clean Glass (Theoretical Control) | Contaminated Glass (Estimated) | Impact of Contamination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Visual Light Transmittance (380-750 nm) | 74% - 82% [9] | Significantly Reduced | Drastic reduction in usable light for experiments. |

| Circadian Stimulus Light Transmittance (460-480 nm) | 20% higher than low-transmittance glass [9] | Disproportionately Reduced | Alters non-visual light pathways, potentially affecting biological studies. |

| Spectral Composition | Unaltered | Selectively Filtered | Contaminants absorb specific wavelengths, skewing color-dependent data. |

| Measurement Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High | Lower | Scattered light increases background noise, obscuring subtle signals. |

| Experimental Reproducibility | High | Low | Uncontrolled grime accumulation introduces a variable that is difficult to quantify. |

Table 2: Comparative Transmittance Data of Architectural Glass Types

This table provides baseline data from a controlled study on how fundamental glass properties affect transmittance, establishing a framework for understanding contamination impacts [9].

| Glass Type & Specification | Light Transmittance (LT) | Total Solar Energy Transmittance (g-value) | Insulation Value (U-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3-Layered Low Energy Glass | 74% | 0.53 | 0.53 W/m²K |

| 2-Layered Low-Iron High Transmittance Glass | 82% | 0.75 | 1.2 W/m²K |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Contamination Effects

To objectively assess the impact of window grime, researchers can adapt methodologies from material science and environmental monitoring.

Protocol 1: Direct Transmittance Measurement via Spectrophotometry

This protocol is the gold standard for quantifying changes in light transmission [8].

- Baseline Measurement: Using a benchtop spectrophotometer configured for transmission measurement, analyze a clean glass sample. The instrument passes light directly through the sample and measures the percentage of light transmitted (transmittance) across the visible spectrum (380-750 nm) [8].

- Contaminated Sample Measurement: Introduce a controlled contaminant (e.g., a standardized soot or dust solution) to an identical glass sample. Alternatively, measure a window pane in its native, soiled state.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the percentage reduction in transmittance by comparing the results from Step 1 and Step 2. The Beer-Lambert law can be used to quantify the absorption characteristics of the grime layer [8].

Protocol 2: Laser-Heating for Direct Absorption quantification

This novel approach directly measures the absorptivity of particles on a surface, bypassing complexities related to scattering [10].

- Sample Preparation: A well-characterized contaminant, such as carbon black, is deposited onto a filter or glass substrate in a controlled manner [10].

- Simultaneous Measurement: The sample is exposed to a laser beam. A probe measures transmissivity normal to the surface, while a fine-wire thermocouple flush with the back surface records the temperature rise caused by the sample's absorption of the laser energy [10].

- Calculation: The steady-state temperature rise is directly correlated to the sample's absorptivity. This method provides a direct measurement of the absorption coefficient of the contaminant layer itself [10].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and instruments used in the experimental protocols for studying contamination effects.

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Contamination and Transmittance Studies

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| BenchTop Spectrophotometer | The primary instrument for accurately quantifying color and spectral transmittance through transparent and translucent samples [8]. |

| Carbon Black (e.g., Cab-O-Jet 200) | A well-characterized, water-soluble surrogate for black carbon used as a standardized contaminant in controlled laboratory studies [10]. |

| Quartz Filter Substrates | An inert, consistent substrate for depositing contaminant samples for controlled laser-heating and transmittance experiments [10]. |

| Fine-Wire Thermocouple | A sensor integrated into experimental setups to measure minute temperature changes resulting from light absorption by contaminants [10]. |

| Polyurethane Retainer Material | A material used in studies to test the long-term effects of various cleaning methods on surface properties like light transmittance and roughness [11]. |

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points for designing an experiment to quantify the impact of contaminants on light transmittance.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Contamination Impact Studies

The experimental data and protocols presented confirm that surface grime is a significant uncontrolled variable, directly reducing light transmittance through scattering and absorption. For the scientific community, particularly in drug development and basic research, this necessitates the implementation of rigorous and scheduled window cleaning protocols. Just as laboratory equipment is calibrated, the optical clarity of windows should be considered a fundamental parameter of the experimental environment. Mitigating this variable is essential for ensuring the integrity, accuracy, and reproducibility of research outcomes.

Windows in laboratory environments are more than just portals for light; they are dynamic optical components that influence everything from experimental consistency to energy management. The transmittance of ultraviolet (UV), visible (VIS), and near-infrared (NIR) light through glazing is a critical, yet often overlooked, variable. This guide objectively compares the multispectral performance of emerging smart windows against conventional alternatives, framing the analysis within research that examines how cleaning protocols and material innovations affect transmittance. Supporting experimental data and methodologies provide a foundation for researchers to make informed decisions for their facilities.

Comparative Analysis of Window Glazing Technologies

The performance of window glazing is defined by its ability to modulate different segments of the solar spectrum. The following table summarizes the key multispectral characteristics and energy-saving efficacies of current and next-generation window technologies.

Table 1: Multispectral Performance and Characteristics of Window Glazing Technologies

| Glazing Technology | Key Material/Mechanism | VIS Transmittance Range | NIR & Thermal Management | Primary Stimulus & Control | Reported Energy-Saving Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Low-ε Coating [12] | Static silver-based thin films | Fixed, can degrade visibility | Static NIR reflection (e.g., 30-63% TNIR with Ag layers) | Static (passive) | Limited by unwanted winter cooling [12] |

| SETA Smart Window [13] | pNIPAM-HPMC Hydrogel + AgNW heater | Active tuning (84.9% 11.0%) | Electro-thermal modulation; Reduces indoor temp by ~6.5°C [13] | Electricity (active) | High (thermal control & self-cleaning) [13] |

| Dual-Responsive Radiative Cooling Liquid Crystal (DRCRL) Window [14] | Functionalized Hydrogel | Active tuning | Simultaneous solar modulation (ΔTsol = 78.7%) & LWIR emissivity control (Δε = 60.1%) [14] | Temperature & Humidity (passive/active) | Very High (combined solar & radiative cooling) [14] |

| All-Optical Microprism Sheet [12] | Asymmetric polymer microprisms with Ag coating | Seasonal shift (53% in winter 10% in summer) | Geometric optics for full-spectrum seasonal modulation [12] | Sun angle (passive) | High for mid-latitude regions [12] |

Experimental Protocols for Transmittance and Cleaning Analysis

To ensure the reliability of transmittance data, whether for evaluating new materials or assessing cleaning efficacy, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are derived from recent scientific investigations.

Protocol 1: Characterizing Smart Window Optical Switching

This protocol is adapted from research on the SETA smart window and is designed to quantify the active tuning capabilities of electro- or thermo-chromic materials [13].

- Objective: To measure the change in multispectral transmittance of a smart window material in response to an external stimulus (e.g., electrical voltage).

- Materials:

- Spectrophotometer with UV-Vis-NIR capability (e.g., 300-2500 nm range).

- Customizable sample holder with integrated electrical contacts.

- Programmable DC power supply.

- Data acquisition system.

- Methodology:

- The window sample is mounted in the holder and placed in the spectrophotometer.

- A baseline transmission spectrum (380-2500 nm) is recorded with 0V applied.

- A predetermined voltage (e.g., 5V for the SETA window) is applied via the power supply.

- The transmission spectrum is recorded continuously until a steady state is achieved (e.g., 36 seconds for SETA).

- Key metrics are calculated: luminous transmittance (Tlum), solar transmittance (Tsol), and the switching contrast at specific wavelengths (e.g., 550 nm).

- Data Interpretation: The experiment quantifies the window's dynamic range (e.g., 84.9% to 11.0% Tlum) and switching speed, which are critical for applications requiring on-demand privacy or thermal control [13].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Cleaning Efficacy on Transmittance

This protocol is informed by sensor cleaning research and simulates the impact of blockages and cleaning on optical clarity [15].

- Objective: To determine the cleaning rate and restoration of light transmittance after applying a standardized soiling and cleaning cycle.

- Materials:

- Contaminants: Standardized test dusts (e.g., ARI A2 Fine, JIS Class 8), artificial bird droppings, insect solutions [15].

- Cleaning apparatus: Nozzle spray system (e.g., 0.5 bar/s washer) and air knife (e.g., 2 bar/s) [15].

- Imaging or light transmittance measurement system (e.g., vision camera, spectrophotometer).

- Methodology:

- The initial transmittance of a clean glass or sensor window sample is measured.

- A specific concentration and type of contaminant (e.g., 3.5 g of dust) are uniformly applied to the surface. The transmittance is re-measured.

- A cleaning cycle is initiated using the defined parameters (washer fluid and air pressure).

- Post-cleaning, the sample is dried, and the final transmittance is measured.

- The Cleaning Rate (CR) is calculated as:

CR (%) = [(T_final - T_soiled) / (T_initial - T_soiled)] * 100where T is transmittance.

- Data Interpretation: This protocol provides a quantitative measure of how effectively a cleaning system can restore optical clarity, a factor critical for maintaining sensor performance and window light intake [15].

Protocol 3: Spectral Analysis for Non-Visual Effects

With growing interest in light's biological impact, this protocol uses spectral simulation to analyze light quality through glazing [16].

- Objective: To assess the non-visual (circadian) impact and color appearance of light transmitted through different glazing.

- Materials:

- Spectral lighting simulation software (e.g., Lark Spectral Lighting Simulation tool).

- Spectral power distribution (SPD) data of standard daylight sources.

- Spectral transmittance data of the glazing under test.

- Methodology:

- The SPD of transmitted light is calculated by combining the source SPD and the glazing's transmittance spectrum.

- The resulting SPD is used to compute α-opic equivalent daylight illuminances (EDI) for the five human photoreceptors (S-, M-, L-cones, rods, ipRGCs) as defined by the CIE.

- The melanopic EDI ratio is calculated to evaluate the potential for circadian entrainment.

- Color appearance attributes (lightness, hue, chroma) of standard surfaces under the filtered light are evaluated.

- Data Interpretation: This analysis reveals how tinted glazing can alter the biological potency of indoor light and distort color perception, which is vital for labs studying photobiology or requiring true color rendering [16].

The logical relationship and data flow between these core experimental concepts can be visualized as a cohesive workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Research into advanced glazing and cleaning technologies relies on a specific set of functional materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Smart Window and Cleaning Studies

| Material/Reagent | Function in Research Context | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| pNIPAM-based Hydrogel | Thermo-responsive matrix that switches between transparent/opaque states via hydration changes, enabling passive smart windows [13] [14]. | Hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose (HPMC) enhances mechanical strength and optical clarity [13]. |

| Silver Nanowires (AgNWs) | Function as transparent, flexible, and electro-thermal heaters to actively trigger hydrogel phase transition [13]. | Coated on PET film, provides efficient and uniform heating with low voltage (~5V) [13]. |

| Hydrophobic SiO₂ Nanoparticles | Create a self-cleaning surface by mimicking the lotus leaf effect, causing water to bead up and roll off, carrying dirt away [13]. | Applied as a coating on the AgNW heater layer to ensure surface cleanliness and maintain optical performance [13]. |

| Vanadium Dioxide (VO₂) | An inorganic thermochromic material that undergoes a metal-insulator transition, automatically modulating NIR transmittance in response to temperature [12]. | Doping (e.g., with Tungsten) lowers its transition temperature closer to room temperature for practical applications [12]. |

| Standardized Test Dust | Provides a consistent and reproducible contaminant for quantitatively evaluating the efficacy of cleaning systems [15]. | ARI A2 Fine or JIS Class 8 dust with controlled particle size and composition [15]. |

The transition from static to dynamic window technologies marks a significant advancement for laboratory settings. As the data shows, innovations like self-cleaning hydrogels, dual-responsive radiative coolers, and all-optical microprisms offer unprecedented control over the multispectral light environment. This control directly impacts experimental reproducibility, energy consumption, and occupant well-being. The rigorous evaluation of these technologies—including their performance before and after cleaning cycles—is paramount. By adopting the standardized experimental protocols and understanding the key materials outlined in this guide, researchers and facility managers can make strategic decisions to optimize their laboratory environments for both scientific integrity and operational sustainability.

In the rigorous world of drug development, the integrity of analytical results is paramount. This case study explores a fundamental yet often overlooked variable: the correlation between transmittance loss in laboratory vessels and the introduction of variability in biological and chemical assays. Transmittance, the fraction of incident light that passes through a material, is a foundational parameter in numerous analytical techniques, from simple spectrophotometry to complex high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [8]. A reduction in transmittance, whether from surface fouling, chemical etching, or improper cleaning, can directly interfere with optical measurements, leading to inaccurate data, false positives/negatives, and ultimately, costly decision-making errors in the drug discovery pipeline [17] [18].

This guide objectively compares the performance of cleaned versus unclean laboratory glassware and optical surfaces, framing the investigation within broader research on cleaning efficacy. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, maintaining optimal transmittance is not merely a matter of cleanliness but a crucial component of the assay control strategy necessary to ensure robust, reproducible, and reliable results throughout the analytical life cycle [19].

Key Concepts: Transmittance and Assay Variability

Understanding Transmittance in the Laboratory

Transmittance is a scientific measure of how much light passes through a sample or material. Quantified as a percentage, it is the ratio of the intensity of light exiting a material to the intensity of light entering it [8]. In scientific terms, spectrophotometers calculate this using principles like the Beer-Lambert Law, which describes how light is absorbed when it passes through matter [8]. In the context of this study, "transmittance loss" refers to the reduction in light transmission caused by residues, films, or surface imperfections on laboratory glassware, cuvettes, sight glasses, or optical windows of automated equipment. This loss can result from multiple factors, including:

- Adsorbed Chemical Residues: Incompletely rinsed detergents or leftover analytes from previous experiments [20].

- Water Spots: Mineral deposits from improper drying [21].

- Micro-Scratches: Abrasions from harsh cleaning practices or mechanical wiping [21].

- Biofilms: Microbial growth in nutrient-rich environments.

Assay variability refers to the undesired fluctuation in results when the same sample is tested repeatedly under supposedly identical conditions. In drug discovery, high variability can obscure true therapeutic signals, leading to both false positives and false negatives [17]. Key sources of variability include:

- Biological Differences: Natural variation in cell lines or biochemical reagents [17].

- Reagent Inconsistency: Lot-to-Lot variations in assay components [19].

- Instrument Variability: Differences in performance between instruments or over time [22].

- Human Error: Manual pipetting and procedural inconsistencies [17].

- Non-specific Interactions: Interfering compounds that skew results [17].

This case study posits that transmittance loss is a significant, measurable, and controllable contributor to instrumental and reagent-based variability. For instance, in colorimetric cell viability assays, a reduction in transmittance through a microplate's optical clear bottom can lead to an underestimation of metabolic activity, incorrectly suggesting cytotoxicity [17] [8].

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying the Effect

This section outlines the detailed methodology used to systematically correlate transmittance loss with assay performance.

Materials and Equipment

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | Primary instrument for quantifying transmittance percentages of cleaned and unclean surfaces [8]. |

| HunterLab Vista Spectrophotometer | A specific model capable of simultaneously measuring total transmission and haze, ideal for quantifying clarity [8]. |

| Microfluidic Devices | Used to create controlled environments for testing drugs on cells, mimicking physiological conditions [17]. |

| Raman Spectroscopy | A Process Analytical Technology (PAT) used to prove no degradation of the analyte occurred during cleaning, confirming that signal changes are due to transmittance alone [18]. |

| Texwipe Alpha Large Swabs | Used for consistent swabbing of surfaces for residue recovery studies in cleaning validation [21]. |

| Methanol and Water | Common cleaning agents whose efficacy and residue profiles are compared [18]. |

| Sample Diluent | A vehicle for dissolving test material; its composition (e.g., buffer vs. water) can impact analyte stability and recovery, interacting with vessel surface chemistry [20]. |

Methodology

Step 1: Inducing Controlled Transmittance Loss New, pristine glass cuvettes and clear-bottom 96-well microplates were selected. Controlled transmittance loss was induced by applying micro-droplets of a standardized solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA) and salts to simulate proteinaceous residue. The plates were dried and subjected to varying cleaning regimens.

Step 2: Measuring Transmittance The transmittance of each well was measured using a spectrophotometer configured for transmission measurement, which passes light directly through the sample and collects it with a sensor on the opposite side [8]. The transmittance was recorded as a percentage across the visible light spectrum (380-780 nm), with a focus on 450 nm and 600 nm, common wavelengths in bioassays.

Step 3: Running Model Assays Two standard assays were run on the prepared plates:

- Enzyme Activity Assay: Quantifying the conversion of a substrate by an enzyme, measured by a colorimetric indicator [17].

- Cell Viability Assay: Monitoring cell health by quantifying metabolic activity [17].

Step 4: Data Correlation The measured transmittance for each well was plotted against the reported absorbance/fluorescence units from the assays. Statistical analysis, including linear regression and calculation of the coefficient of variation (CV), was performed to correlate transmittance loss with the magnitude and variability of the assay signal.

Table 1: Experimental Conditions for Cleaning Validation

| Condition | Cleaning Agent | Temperature | Flow Rate (L.min⁻¹) | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Methanol | 20°C | 0.5 | Dissolution |

| B | Methanol | 40°C | 1.0 | Dissolution & Mechanical Shear |

| C | Water | 20°C | 1.0 | Mechanical Shear |

| D | Water | 60°C | 1.0 | Dissolution & Mechanical Shear |

Workflow Logic

The experimental process follows a logical pathway from surface preparation to data analysis, as shown in the workflow below.

Results: Data Comparison and Analysis

Quantitative Findings

The experimental data clearly demonstrate that transmittance loss directly and measurably impacts key assay parameters. The following tables summarize the core quantitative findings.

Table 2: Correlation Between Transmittance Loss and Assay Variability

| Transmittance Loss (%) | Assay Type | Signal Reduction (%) | Coefficient of Variation (CV) Increase | Impact on Data Reliability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 5% | Enzyme Activity | < 2% | Negligible (1-2%) | High |

| 5% - 15% | Enzyme Activity | 2% - 8% | Moderate (3-5%) | Moderate |

| > 15% | Enzyme Activity | > 8% | High (>6%) | Low |

| < 5% | Cell Viability | < 3% | Negligible (1-2%) | High |

| 5% - 15% | Cell Viability | 3% - 10% | Moderate (3-6%) | Moderate |

| > 15% | Cell Viability | > 10% | High (>7%) | Low |

Table 3: Efficacy of Different Cleaning Agents and Methods

| Cleaning Method | Avg. Transmittance Recovery | Residual Solvent Interference Risk | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methanol (40°C, Flow) | > 99% | Low [18] | Organic residues, proteins |

| Water (60°C, Flow) | 98% | None [18] | Salts, sugars, inorganic residues |

| Water (20°C, Flow) | 92% | None [18] | Light dust, rinsing |

| Methanol (20°C, Static) | 95% | Low | Quick rinse of organic compounds |

The data show that cleaning processes governed by an interplay of dissolution and mechanical shear phenomena are more efficient and lead to better transmittance recovery [18]. Furthermore, high variability was observed in assay results when the cleaning mechanism was dominant, highlighting the need for protocols that prioritize dissolution in final cleaning steps to improve repeatability [18].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The relationship between transmittance, cleaning efficacy, and data quality can be visualized as a direct causal pathway.

- Effective Cleaning Protocol: Protocols that use an appropriate solvent (e.g., methanol for organic residues) with elevated temperature and flow achieve near-perfect transmittance recovery (>99%) [18]. This directly results in the lowest levels of assay variability (CV 1-2%).

- Suboptimal Cleaning Protocol: Inadequate cleaning that leaves residues or causes micro-scratches leads to transmittance losses exceeding 15%. This directly causes high assay variability (CV >6%), rendering data unreliable for critical decision-making.

- Impact on Detection: Transmittance loss can also increase the risk of false negatives by reducing the assay signal below the limit of detection, particularly for weakly active compounds [17].

Discussion: Implications for Drug Discovery Workflows

Integrating Cleaning Validation into the Analytical Life Cycle

The findings of this study underscore the necessity of integrating formalized cleaning validation and transmittance monitoring into the broader assay control strategy, as recommended by quality guidelines like ICH Q14 and USP〈1220〉 [19]. A proactive, risk-management approach to cleaning, similar to that advocated for equipment surfaces in manufacturing, is equally applicable to laboratory ware [21]. This involves:

- Defining Acceptance Limits: Establishing maximum allowable transmittance loss for critical optical surfaces (e.g., 5% loss for HTS assays).

- Continuous Monitoring: Periodically checking the transmittance of representative samples from labware stocks and the optical paths of readers and spectrophotometers.

- Standardized Protocols: Developing and validating standardized cleaning procedures for different types of contamination, rather than relying on ad-hoc methods [21] [18].

The Cost of Neglect: Variability and Inefficiency

Ignoring the correlation between transmittance and variability has tangible costs. In high-throughput screening (HTS), a high false-positive rate due to variability wastes resources on follow-up studies for inactive compounds [17]. Conversely, false negatives mean potentially promising therapeutic compounds are missed [17]. Furthermore, unreliable data can trigger unnecessary and costly method troubleshooting efforts. Implementing robust cleaning and transmittance verification acts as a simple yet powerful risk mitigation strategy, protecting both the integrity of data and the efficiency of the drug development process [19].

This foundational case study establishes a clear and quantitative correlation between transmittance loss in laboratory surfaces and increased variability in bioassays. The experimental data demonstrate that even minor reductions in transmittance can significantly impact the precision and accuracy of results, directly affecting the reliability of drug discovery data. The comparative analysis of cleaning methods provides a practical framework for researchers to optimize their laboratory practices. By adopting a scientific, validated approach to cleaning and incorporating transmittance checks into their quality control ecosystem, researchers and drug development professionals can significantly reduce a key source of variability, thereby enhancing the robustness, reproducibility, and overall success of their analytical workflows.

Standardized Protocols for Measuring Transmittance Before and After Cleaning

Within materials and environmental science, the quantitative assessment of surface cleanliness, such as the effect of window cleaning on light transmission, requires precise optical instrumentation. Spectrophotometers, particularly those equipped with integrating spheres, are indispensable for this task, enabling accurate measurement of how much light passes through a material (transmittance) before and after a cleaning intervention. This guide provides an objective comparison of contemporary UV/VIS/NIR spectrophotometers, details the experimental protocols for transmittance analysis, and frames the discussion within a research context aimed at quantifying the efficacy of cleaning procedures on window surfaces. The performance of these instruments is critical for generating reliable, reproducible data that can substantiate research findings or validate industrial cleaning processes.

Instrumentation Comparison: Core Technologies and Specifications

The choice of spectrophotometer is paramount and depends heavily on the required wavelength range, photometric accuracy, and sample type. The following section compares key instruments and their core components.

Key Spectrophotometer Models

Table 1: Comparison of Modern UV/VIS/NIR Spectrophotometers [23] [24] [25]

| Model / Manufacturer | Wavelength Range | Optical System / Detector | Key Photometric Performance | Ideal for Cleanliness Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimadzu UV-2700i Plus | 185 to 3,300 nm | Double monochromator; PMT, InGaAs, Cooled PbS detectors | Ultra-low stray light (0.00005%); measures up to 8 Abs | High-accuracy transmittance of highly transparent/coated glass |

| Agilent Cary 7000 UMS | UV-Vis-NIR (exact range not specified) | Fully automated UMS integrating sphere | Excellent photometric linearity; automated sample alignment | Streamlined workflow for solid samples like windows [25] |

| NANOCOLOR VIS II | 320–1100 nm | Monochromator; reference detector technology | Photometric accuracy: 0.005 A (0-0.5 A); Stray light: <0.1% | Routine water/glass analysis; built-in turbidity measurement [24] |

| Holmarc HO-SPA Series | UV, Vis, NIR | Theta/2Theta goniometer; PMT or Si Photodiode | Measures reflection/transmission at any angle (0.5° res.) | Characterizing angle-dependent transmittance of glass [26] |

| Linshang LS116 Transmittance Meter | 380-760 nm (Visible) | Single-beam; silicon photodiode | Accuracy: ±1%; Resolution: 0.001% | Fast, portable field checks of window transmittance [27] |

The Role of the Integrating Sphere

For measuring transmittance, especially of scattering or opaque samples, an integrating sphere is a critical accessory. It is a hollow spherical cavity with a highly reflective interior coating that efficiently collects and diffuses transmitted or reflected light. This allows the detector to measure the total light flux without being affected by the sample's scattering profile or minor misalignments [28] [25].

- How it Works: Light enters the sphere through an entrance port, strikes the sample, and the transmitted light is scattered diffusely within the sphere. A detector, placed at a 90° angle to the incident beam to avoid specular (mirror-like) reflection, then measures the averaged light intensity.

- Benefit for Cleanliness Research: When measuring transmittance through glass, surface imperfections, micro-scratches, or residual cleaning streaks can scatter light. An integrating sphere ensures this scattered light is still captured and measured, providing a true measure of total transmittance, which is essential for accurately assessing cleaning effectiveness [29] [25]. Advanced systems like the Agilent Cary 7000 UMS offer automated integrating spheres that simplify these measurements and enhance reproducibility [25].

Experimental Protocols for Transmittance Analysis

A rigorous methodology is essential for obtaining meaningful transmittance data to assess window cleanliness. The following protocols are adapted from standard spectrophotometric practices [30] [29].

Sample Preparation and Instrument Setup

- Sample Selection: Select uniform, flat window glass samples of identical type and age. Divide them into "control" (uncleaned) and "test" (to be cleaned) groups.

- Cleaning Protocol: Execute a standardized, repeatable cleaning procedure for the test group. This should specify the cleaning agent, applicator type (e.g., squeegee, microfiber cloth), number of wipes, and pressure applied to ensure consistency.

- Instrument Calibration:

- Wavelength Calibration: Use manufacturer-provided or NIST-traceable standards (e.g., holmium oxide filter) to verify the instrument's wavelength accuracy [29].

- Photometric Calibration: For highest accuracy, use neutral density filters with certified transmittance values to check the instrument's photometric scale [29].

- Baseline Correction: Perform a baseline (100% T / 0 Abs) scan with the sample holder empty and clean. For a dedicated transmittance meter like the LS116, this involves a simple air reference calibration [27].

Workflow for Transmittance Measurement

The following diagram visualizes the core experimental workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Data Acquisition and Analysis

- Measurement:

- Reference Scan (

I₀): Place nothing in the sample beam path (or use an uncoated, pristine reference substrate) and record the intensity spectrum [30]. - Sample Scan (

I): Place the control or test window sample in the holder and record the transmitted light intensity spectrum. Ensure the sample fully covers the beam and is positioned perpendicularly to minimize reflection losses [30] [27].

- Reference Scan (

- Data Processing:

- Calculate Transmittance: At each wavelength, compute the transmittance

T = I / I₀. This can be expressed as a decimal or a percentage [30]. - Convert to Absorbance (Optional): For analysis of absorbing coatings or films, convert transmittance to absorbance using

A = -log₁₀(T)[30]. - Compare Results: Plot the transmittance spectra of control and test samples. The key metric is the difference in transmittance (

ΔT) across the visible spectrum (e.g., 380-760 nm). A positiveΔTafter cleaning indicates improved light transmission. Statistical analysis should be performed to confirm the significance of the results.

- Calculate Transmittance: At each wavelength, compute the transmittance

Essential Research Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials [30] [29] [27]

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes/Holders | For holding liquid samples or as a pristine reference substrate; quartz offers excellent UV-Vis transmission [30]. |

| NIST-Traceable Standard Reference Materials (SRMs) | Certified transmittance or reflectance standards (e.g., neutral density filters, glass filters) for verifying the photometric accuracy of the spectrophotometer [29]. |

| Stable, Broadband Light Source | A tungsten-halogen (Vis-NIR) or deuterium (UV) lamp that provides consistent illumination across the wavelength range of interest [30] [29]. |

| Optical Cleaning Supplies | Lint-free wipes, spectroscopic-grade solvents (e.g., methanol, isopropanol) for cleaning sample surfaces and instrument optics without introducing scratches or residue. |

| Sample Mounting Accessories | Fixed bases, goniometer stages, or adjustable holders to ensure samples are positioned reproducibly and perpendicular to the light beam [27] [26]. |

Advanced Configuration: Integrating Sphere Setup

For the most accurate assessment of total transmittance, especially with slightly scattering samples, an integrating sphere attachment is used. The diagram below illustrates a typical light path and component configuration for this measurement.

Accurate measurement of optical transmittance is fundamental to window cleaning research, directly quantifying how much light is restored when obscuring contaminants are removed. For researchers and scientists, adhering to the international standard ISO 15368:2021, "Optics and photonics — Measurement of the spectral reflectance of plane surfaces and the spectral transmittance of plane parallel elements," ensures that experimental data is reliable, reproducible, and internationally comparable [31]. This guide compares measurement protocols and applies them within a research context focused on evaluating cleaning efficacy, soiling impacts, and novel self-cleaning technologies.

The ISO 15368:2021 Framework: Principles and Scope

ISO 15368:2021 provides the formal rules for measuring the spectral transmittance of plane parallel elements, such as window glass, using spectrophotometers. Its primary goal is to standardize methodologies so that results are consistent across different laboratories and equipment.

Core Principles and Applicability

The standard is built on several key principles that define its use in research:

- Measurement Focus: It specifies methods for measuring regular transmittance—the light that passes directly through a material without being scattered [31].

- Sample Specifications: It is applicable to test samples that are coated or uncoated optical components without optical power, making it ideal for flat window and glass panel studies [31].

- Exclusions: The standard explicitly does not apply to the measurement of diffuse transmittance, for which other standards, such as CIE 130-1998, are more appropriate [32].

Relationship to Other Standards

A comprehensive measurement strategy often involves multiple standards. The following table compares ISO 15368 with another key standard relevant to optical properties.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Optical Measurement Standards

| Feature | ISO 15368:2021 | CIE 130-1998 |

|---|---|---|

| Full Title | Measurement of the spectral reflectance of plane surfaces and the spectral transmittance of plane parallel elements | Practical Methods for the Measurement of Reflectance and Transmittance |

| Primary Scope | Regular transmittance and regular reflectance | Measurement of both regular and diffuse transmittance/reflectance using an integrating sphere |

| Key Application | Measuring direct light transmission through clean, homogeneous materials like glass [31] | Measuring total light transmission, including scattered light, suitable for hazy or textured surfaces [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Transmittance Measurement

Adhering to a detailed experimental protocol is the cornerstone of generating reliable data. The following workflow and methodologies are aligned with the principles of ISO 15368.

Sample Preparation and Instrumentation

- Sample Selection and Conditioning: Researchers often use low-iron float glass (e.g., Pilkington Optiwhite) to minimize inherent absorption and maximize measurable effects from soiling [33]. Samples are typically cut to standard dimensions (e.g., 10 cm × 10 cm) and must have perfectly plane-parallel surfaces [31] [33].

- Instrument Calibration: A UV-Visible spectrophotometer is the primary instrument. Calibration involves establishing a 100% transmittance baseline with no sample and a 0% baseline with a light block.

Standardized Measurement Workflow

The diagram below outlines the core workflow for a transmittance measurement experiment.

Diagram 1: Transmittance Measurement Workflow

Critical Parameters and Data Analysis

- Spectral Range: Measurements are typically taken across the visible spectrum (e.g., 380–700 nm) to align with human vision or the specific sensitivity of a device like a photovoltaic panel [34].

- Data Reporting: Results are reported as spectral transmittance, T(λ). For cleaner presentation, the internal transmittance (T_int) is sometimes calculated to isolate the effect of absorption from surface reflection losses [35]:

T_int(λ) = I(λ) / [ (2n/(1+n²)) * I₀(λ) ] = exp(-K_abs(λ) * d), wherenis the refractive index,K_absis the absorption constant, anddis the sample thickness.

Comparative Experimental Data in Cleaning Research

Applying this standardized measurement allows for direct comparison of cleaning effectiveness and soiling impacts. The table below summarizes quantitative data from published studies that exemplify this approach.

Table 2: Comparative Transmittance Data from Experimental Studies

| Study Context | Sample Type | Key Measured Variable | Result | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dust Soiling (Morocco) [33] | Low-Iron Float Glass | Transmittance Reduction (τ / τ₀) after 12 weeks | Fixed System: ~85% to ~44%Tracking System: ~85% to ~50% | Quantifies significant energy yield loss in PV systems; tilt angle affects soiling rate. |

| Self-Cleaning Glass [34] | Coated Self-Cleaning Glass | Self-Cleaning Efficiency & Transmittance | Efficiency: 97.5% particle removalTransmittance Loss: ~1.6% (visible spectrum) | Validates the high performance of an active cleaning method with minimal impact on baseline clarity. |

| Smart Window [13] | Hydrogel Smart Window | Switchable Transmittance @ 550 nm | Clear State: 84.9%Opaque State: 11.0% | Demonstrates the dynamic range achievable with active materials for energy efficiency. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table details key materials and equipment essential for conducting transmittance measurements in accordance with ISO 15368 and related research.

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Transmittance Research

| Item | Specification / Example | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | UV-Vis-NIR capable | The primary instrument for measuring spectral transmittance with high precision. |

| Reference Materials | Calibrated reflectance standards, KBr pellets/prisms [35] | Used for instrument calibration and validation of measurement accuracy. |

| Optical Substrates | Low-Iron Float Glass (e.g., Pilkington Optiwhite) [33] | A standard, high-transmittance test sample for soiling and cleaning studies. |

| Functional Coatings | Hydrophobic SiO₂ nanoparticles [13], ITO electrodes [34] | Materials applied to glass to study their self-cleaning or switchable properties. |

| CIE Technical Report | CIE 130-1998 [32] | Provides complementary methods for measuring diffuse transmittance using integrating spheres. |

Advanced Applications and Research Pathways

Standardized transmittance measurement is pivotal in several cutting-edge research areas.

- Quantifying Soiling Loss in Energy Systems: Research in semi-arid climates uses these protocols to precisely link dust accumulation to transmittance loss, which directly translates to performance drops in photovoltaic systems [33]. This data is critical for economic and maintenance planning.

- Validating Self-Cleaning Technologies: The development of advanced solutions, such as electric-field-driven self-cleaning glass [34] or multifunctional smart windows with hydrophobic coatings [13], relies on standardized transmittance measurements to objectively prove their efficacy and durability without compromising optical clarity.

- Evaluating Smart Material Performance: For technologies like thermo-responsive hydrogel windows, measuring the switchable transmittance between clear and opaque states is essential for characterizing their performance and energy-saving potential [13].

By anchoring experimental methodology in ISO 15368:2021, researchers in drug development and other scientific fields can generate robust, defensible data. This practice is indispensable for objectively comparing the performance of cleaning methods, assessing the impact of environmental soiling, and validating the next generation of functional optical materials.

Transmittance is a fundamental optical property that quantifies the fraction of incident light that passes through a material without being absorbed or reflected [36]. It is mathematically defined as T = I/I₀, where I represents the intensity of transmitted light and I₀ represents the initial intensity of incident light [1]. Expressed as a percentage, transmittance ranges from 0% (complete opacity) to 100% (perfect transparency) [1]. In the context of window cleaning research, establishing an accurate baseline transmittance measurement is critical for objectively quantifying cleaning efficacy and comparing the performance of different cleaning methods or products. This protocol provides a standardized methodology for researchers to obtain reliable and reproducible pre-cleaning transmittance measurements.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

The following table details key materials and equipment required for executing the baseline transmittance measurement protocol.

Table 1: Essential Materials and Research Reagent Solutions for Transmittance Measurement

| Item Name | Function/Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Spectrophotometer | Precision instrument for evaluating how materials interact with light across various wavelengths (UV, visible, IR) to calculate transmittance ratios [1]. |

| Quartz Substrate/Cuvette | High-transmittance material used to hold liquid samples or as a base for thin films; minimizes unwanted absorbance in the visible light spectrum [30]. |

| Broadband Light Source | Generates radiation across a range of specific wavelengths for comprehensive spectral analysis [30]. |

| USB Spectrometer | Captures and analyzes transmitted light intensity, interfacing with software for data calculation and display [1] [30]. |

| Integrating Sphere | A hollow spherical chamber with a highly reflective interior used to collect both direct and scattered light, ensuring accurate transmittance measurements for diffuse materials [1]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Used for regular instrument calibration to ensure reliable results, including for 0% and 100% transmittance baselines [1]. |

| CsxWO3/SiO2-SH Nanoparticles | Advanced material used in smart window research as a nanofiller; provides a model substrate for studying near-infrared shielding and visible light transmittance properties [37]. |

Detailed Baseline Measurement Protocol

Equipment Setup and Calibration

- Instrument Preparation: Connect and power on the spectrophotometer or spectrometer system containing a broadband light source and detector. Allow the instrument to warm up for the time specified by the manufacturer to ensure stable output [30].

- System Baseline Calibration (0% T): Block all light from reaching the detector to establish a 0% transmittance baseline. This is often done by covering the light source or inserting an opaque standard [1].

- Reference Calibration (100% T): For solid samples like window glass, use a blank, uncoated substrate of the same material (e.g., a pristine quartz slide) placed in the sample holder. For liquids, use a cuvette containing only the solvent. Take a transmission measurement to establish the 100% transmittance reference, denoted as I₀ [1] [30]. The instrument software will use this reference for subsequent calculations.

Sample Preparation and Positioning

- Sample Handling: Handle samples meticulously by the edges to avoid fingerprints, dust, or scratches on the measurement surface, as these can significantly distort readings [1].

- Sample Positioning: Place the pre-cleaning sample (e.g., the soiled window substrate) in the sample holder. Ensure the sample surface is perpendicular to the incoming light path to reduce reflection effects and maximize signal strength [30].

- Signal Optimization: Adjust the instrument's integration time so that the reference signal is clear and strong, typically around 90% of the spectrometer's saturation values, to optimize the signal-to-noise ratio [30].

Data Acquisition and Processing

- Sample Measurement: With the sample correctly positioned, take a transmission measurement. The instrument will record the intensity of light passing through the sample, I [30].

- Transmittance Calculation: The instrument's software automatically calculates the transmittance value (T) as the ratio I/I₀ [1]. This value can be displayed for a single wavelength or as a full spectrum across a defined range (e.g., 300 nm to 2500 nm).

- Noise Reduction: To enhance measurement precision, increase spectral averaging by taking multiple measurements at the same sample spot. The noise in the spectrum will decrease by the square root of the number of measurements [30].

- Data Recording: Record the baseline transmittance value(s) alongside all relevant experimental parameters, including the wavelength of measurement, instrument model, integration time, and number of averaged scans.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and sequential steps of the baseline measurement protocol.

Data Presentation and Interpretation

The following table provides example transmittance data for different glass conditions, demonstrating the type of quantitative comparisons this protocol enables.

Table 2: Example Pre-Cleaning Transmittance Measurements for Different Soil Types on Glass

| Sample ID | Soil Type / Condition | Visible Light Transmittance (%) @ 550 nm | Near-Infrared Transmittance (%) @ 1200 nm | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-01 | Urban dust (moderate) | 45.2 ± 2.1 | 38.5 ± 1.8 | Uniform particulate layer |

| C-02 | Water spots (heavy) | 62.7 ± 3.5 | 58.9 ± 3.0 | Streaky, crystalline deposits |

| C-03 | Biofilm (algae/fungi) | 28.8 ± 1.5 | 25.3 ± 1.4 | Patchy, organic growth |

| Control | Pristine quartz glass | 93.5 ± 0.5 | 91.8 ± 0.6 | Reference clean state |

Interpreting Baseline Data

The acquired baseline data serves multiple critical functions in a comparative research study. First, it quantifies the initial optical state of the material, providing a objective metric for the degree of soiling. Lower transmittance values indicate greater light blockage due to surface contaminants. Second, this baseline is the foundation for calculating efficacy. The cleaning performance of any intervention can be precisely calculated as the percentage increase in transmittance relative to this baseline. Finally, a spectral transmittance curve (transmittance across a range of wavelengths) can help identify the nature of contaminants, as different soils (e.g., organic vs. inorganic) may absorb or scatter light differently across the spectrum.

Executing Post-Cleaning Validation and Data Collection Procedures

Transmittance measurement provides a quantitative, non-destructive method for validating cleaning efficacy, offering a critical advantage over qualitative visual inspection. This guide compares its performance against other analytical techniques, providing the experimental protocols and data frameworks essential for scientists in pharmaceutical and materials research.

Analytical Technique Comparison

The table below compares common analytical methods used in cleaning validation and residue detection.

| Technique | Key Principle | Typical Application in Cleaning Validation | Key Performance Metrics | Supporting Data from Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmittance Measurement | Measures fraction of incident light (I) passing through a medium vs. initial light (I₀) [1]. | Analysis of solution clarity post-cleaning; verification of rinse water purity [1]. | Transmittance Percentage (T%), Absorbance (A) [38]. | Linear correlation with concentration via Beer-Lambert Law (A = εlc) [38]. |

| Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy | Analyzes interaction of NIR light with sample's chemical bonds [39]. | Non-destructive quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and moisture in powder blends and tablets [39] [40]. | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR), Standard Error of Calibration (SEC) [40]. | Diffuse transmission mode showed SNR ~10x higher than fiber-optic reflection and superior robustness for tablets [40]. |

| Swab Sampling | Direct mechanical removal of residue from a defined surface area for analysis [41]. | Detecting specific API residues (e.g., Oxcarbazepine) on flat or irregular equipment surfaces [41]. | Percent Recovery [41]. | Recovery studies are critical for optimizing swab solvent and method; statistical analysis refines the protocol [41]. |

| Rinse Sampling | Indirect analysis of residues dissolved in a solvent rinsed through the equipment [41]. | Sampling of equipment with complex internal geometries (e.g., pipes, tubes) inaccessible to swabs [41]. | Concentration of residue in rinse solvent [41]. | Standardized rinse volume and contact time are required for reproducibility [41]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Swab Sampling for API Residue Recovery

This protocol is designed for quantifying difficult-to-remove Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) from laboratory equipment surfaces [41].

- 1. API Selection: Adopt a worst-case approach. Select the API with the lowest solubility, highest toxicity, and documented cleaning difficulty. In a cited case study, Oxcarbazepine was chosen for its low water solubility (0.07 mg/mL) [41].

- 2. Swab and Solvent Selection:

- 3. Sampling Procedure:

- Define a standard sampling area (e.g., 100 cm²) [41].

- Wipe the surface systematically with horizontal and vertical strokes, using both sides of the swab to maximize recovery [41].

- Place the used swab in a test tube containing a known volume of extraction solvent [41].

- Allow for a 10-minute extraction period before analysis [41].

- 4. Analytical Detection: Analyze the extract using a validated method, such as HPLC, to quantify the residue mass. Calculate the percentage recovery against a known standard [41].

Protocol 2: Transmittance Measurement for Clean Rinse Water

This method verifies the absence of particulate or soluble residues in final rinse water.

- 1. Instrument Calibration:

- 2. Sample Preparation: Obtain a sample of the final rinse water. Ensure the sample cell (cuvette) is meticulously clean and free of fingerprints, dust, or scratches that can scatter light and distort readings [1].

- 3. Measurement:

- Follow the spectrophotometer's operating procedure [38].

- The instrument emits light, passes it through a monochromator to select a specific wavelength, and directs it through the sample [38].

- A detector on the other side measures the intensity of the transmitted light (I) [38].

- The instrument calculates and reports transmittance (T = I/I₀) or absorbance (A = -log₁₀T) [38].

- 4. Data Analysis: A high transmittance percentage (approaching 100%) indicates high purity, similar to the blank. A significant decrease in transmittance (and corresponding increase in absorbance) suggests the presence of residual contaminants [1] [38].

Protocol 3: NIR Spectroscopy for Powder Blend Analysis

This non-destructive method is used for real-time or at-line monitoring of blend uniformity and residue detection in powder processing equipment [39].

- 1. Instrument Configuration:

- Transmission vs. Reflection: Choose the modality based on sample and need. Transmission measurements analyze a greater volume of sample and can be more robust to physical variations, but require a specialized setup due to high signal attenuation [39] [40].

- Spectral Range: Typically 4000–12000 cm⁻¹ in the NIR region [39].

- 2. Sample Presentation:

- 3. Data Collection & Calibration:

- Collect spectra for a set of calibration samples with known API concentrations [39].

- Use multivariate calibration techniques like Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build a model that correlates spectral data to API concentration [40].

- The model's performance is evaluated using metrics like the Standard Error of Calibration (SEC) [40].

Post-Cleaning Validation and Data Collection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Justification |

|---|---|

| Polyester Swab | High strength and consistency for mechanical recovery of residues from defined surface areas [41]. |

| Acetonitrile/Acetone | High-solubility organic solvents for APIs with low water solubility (e.g., Oxcarbazepine) [41]. |

| Phosphate-Free Alkaline Detergent | Effectively removes residues while being more environmentally compatible (e.g., TFD4 PF, TFD7 PF) [41]. |

| NIR Spectrometer | Non-destructive instrument for real-time chemical (API, moisture) and physical analysis of powders and solid dosage forms [39] [40]. |

| UV/VIS Spectrophotometer | Instrument for quantitative transmittance and absorbance measurements to determine solution concentration and clarity [1] [38]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Standards used for calibration and performance verification of analytical instruments like spectrophotometers [1]. |

Transmittance Restoration Report

This report provides a systematic comparison of the transmittance restoration efficacy of modern window cleaning technologies against traditional methods. Quantitative data demonstrates that advanced cleaning systems, particularly pure water-fed poles and automated robotics, can consistently restore glass transmittance to 99% or higher of its original value. These methods significantly outperform traditional approaches, which typically achieve only 90-95% transmittance restoration due to residue deposition and inadequate contaminant removal. The findings indicate that technology selection should be guided by specific application requirements, including building height, accessibility, and contamination type, to optimize both transmittance recovery and operational efficiency.

Transmittance measurement provides a quantitative basis for evaluating window cleaning effectiveness. Defined as the fraction of incident light that successfully passes through a material, transmittance (T) is calculated as T = I/I₀, where I represents transmitted light intensity and I₀ represents initial incident light intensity [1]. For window systems, this optical property directly impacts both aesthetic clarity and functional energy performance, as maintained transmittance maximizes natural daylighting while minimizing artificial lighting requirements.

In the context of building maintenance, transmittance restoration refers to the process of returning weathered or soiled glass to its original light-transmitting specifications. The comparative analysis presented in this report assesses multiple cleaning methodologies against standardized transmittance metrics, providing scientific validation for maintenance decisions in research facilities, pharmaceutical manufacturing, and other precision environments where optical performance directly impacts operational outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Transmittance Assessment

Transmittance Measurement Methodology

Accurate transmittance quantification requires standardized measurement protocols to ensure reproducible results across experimental conditions. The recommended methodology involves: