Raman Spectroscopy for Microplastics Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Raman spectroscopy's application in microplastics research, tailored for scientists and drug development professionals.

Raman Spectroscopy for Microplastics Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Raman spectroscopy's application in microplastics research, tailored for scientists and drug development professionals. It covers the fundamental principles that make Raman spectroscopy particularly suited for analyzing microplastics in aqueous and complex biological matrices. The content explores advanced methodological approaches, including high-throughput imaging and flow-through systems for enhanced detection. It addresses key analytical challenges such as fluorescence interference from pigments and organic matter, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, the article presents validation frameworks and comparative analyses with complementary techniques like FT-IR and fluorescence microscopy, equipping researchers with the knowledge to implement robust, reliable microplastic analysis in environmental and biomedical contexts.

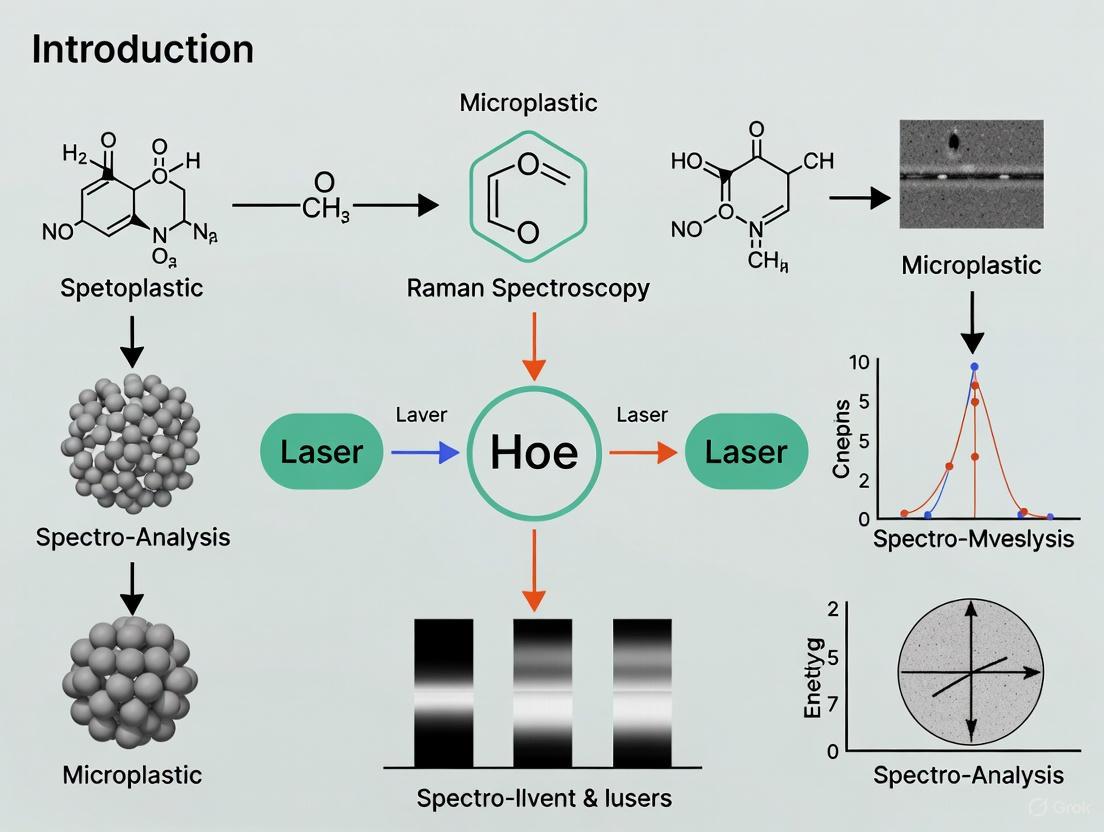

The Fundamentals of Raman Spectroscopy for Microplastic Detection

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique that leverages the phenomenon of inelastic light scattering to generate a unique molecular fingerprint of a sample. When monochromatic laser light interacts with a substance, a minuscule fraction of the scattered light undergoes energy shifts corresponding to the vibrational modes of its molecules. This resulting "Raman shift" provides a highly specific spectral signature that can be used to identify, characterize, and quantify chemical components. This whitepaper details the core principles of Raman spectroscopy, its instrumental setup, and its specific application in the field of microplastics research, highlighting advanced protocols that combine spectroscopy with artificial intelligence to address complex environmental challenges.

Raman spectroscopy is a chemical analysis technique that involves illuminating a substance with a laser and analyzing the scattered light to obtain information about its molecular structure [1]. The process is named after C.V. Raman, who first observed the effect in 1928 [2] [3].

When light interacts with a molecule, the oscillating electromagnetic field of the photon can induce a polarization of the molecular electron cloud [3]. Most of the scattered light is elastically scattered, meaning it has the same energy (wavelength) as the incident laser light; this is known as Rayleigh scattering [4] [1]. However, approximately 1 in 10 million photons undergoes inelastic scattering, where the scattered photon has a different energy than the incident photon [3]. This is the Raman effect [1].

The energy change in the scattered photon is equal to the energy of a vibrational mode of the molecule. If the scattered photon has less energy (longer wavelength) than the incident photon, the process is called Stokes Raman scattering. If the scattered photon has more energy (shorter wavelength), it is called anti-Stokes Raman scattering [4] [3]. Stokes scattering is more intense and more commonly used in spectroscopy because, at room temperature, most molecules are in their ground vibrational state, making Stokes transitions statistically more probable [4] [2].

- Rayleigh Scattering: The molecule returns to the same vibrational state. The scattered light has the same energy as the incident laser light [4] [3].

- Stokes Raman Scattering: The molecule ends in a higher vibrational state. The scattered light has less energy than the incident laser light [4] [3].

- Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering: The molecule ends in a lower vibrational state. The scattered light has more energy than the incident laser light [4] [3].

The Raman Spectrum: A Molecular Fingerprint

The inelastically scattered light is collected by a detector, and its frequency shift relative to the laser line is calculated. This shift, known as the Raman shift, is independent of the laser's excitation wavelength and is characteristic of the specific molecular vibration that caused it [2] [1].

The Raman shift (Δν̃) is calculated in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹) using the formula: Δν̃ (cm⁻¹) = ( 1 / λ₀ (nm) - 1 / λ₁ (nm) ) × 10⁷ [2] Where λ₀ is the excitation laser wavelength and λ₁ is the wavelength of the Raman-scattered light.

A plot of the intensity of this scattered light against the Raman shift produces a Raman spectrum [1]. Each peak in the spectrum corresponds to a specific molecular vibration, creating a unique "chemical fingerprint" that can be used to identify the substance [4] [1]. The spectrum for a complex molecule will contain many peaks corresponding to its numerous vibrational modes [1]. For a molecule with N atoms, the number of fundamental vibrational modes is 3N-6 for non-linear molecules and 3N-5 for linear molecules [3].

Raman vs. FT-IR Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy provides information complementary to another major vibrational spectroscopy technique, Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy [2]. The key differences are summarized in the table below.

| Feature | Raman Spectroscopy | FT-IR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Measures inelastic light scattering due to a change in molecular polarizability [2]. | Measures absorption of IR light due to a change in molecular dipole moment [2]. |

| Sensitivity to Bonds | Excellent for non-polar, covalent bonds (e.g., C-C, C=C, S-S, C-S) [4] [2]. | Excellent for polar bonds (e.g., C=O, O-H, N-H) [2]. |

| Water Compatibility | Compatible with aqueous samples, as water is a weak Raman scatterer [5]. | Less compatible, as water has strong IR absorption bands [5]. |

| Sample Preparation | Typically minimal; can analyze samples through glass or plastic packaging [4] [1]. | Often requires specific preparation to avoid signal saturation [5]. |

| Typical Laser Wavelength | Visible to near-infrared (e.g., 532 nm, 785 nm) [4]. | Infrared light source [2]. |

Instrumentation and the Scientist's Toolkit

A basic Raman spectroscopy setup consists of several key components that work in concert to excite the sample, collect the scattered light, and detect the signal [4].

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Components

The following table details the essential components of a Raman spectroscopy system and their functions in a typical experiment.

| Component | Function & Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Source | Provides the monochromatic light required to excite the sample. Wavelength choice is critical to avoid fluorescence [4] [2]. | Nd:YAG lasers (1064 nm, 532 nm), 785 nm diode lasers. 785 nm is often a good balance between performance and cost [4]. |

| Filters | Bandpass Filter: Cleans the laser beam before it hits the sample. Longpass/Notch Filter: Blocks the intense Rayleigh-scattered laser light while allowing the Raman-shifted light to pass to the detector [4] [2]. | Notch filters, edge pass filters [2]. |

| Detector | Converts the collected photons into an electrical signal to generate the spectrum. The choice depends on the laser wavelength used [4]. | Charge-Coupled Devices (CCDs) for visible lasers; Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) for NIR lasers [4] [2]. Back-thinned CCDs offer high quantum efficiency (>90%) [4]. |

| Spectrograph | Disperses the collected Raman light into its constituent wavelengths/frequencies, allowing the full spectrum to be projected onto the detector [2]. | Czerny-Turner (CT) monochromators [2]. |

| Microscope (Optional) | Allows for the analysis of microscopic samples by focusing the laser onto a tiny spot and collecting the scattered light with high spatial resolution [4] [1]. | Confocal Raman microscopes [4] [1]. |

Advanced Applications in Microplastics Research

Raman spectroscopy has become a cornerstone technique for the identification and characterization of microplastics (particles < 5 mm) due to its high chemical specificity, compatibility with water, and ability to analyze particles down to the micrometer scale [5].

High-Throughput Raman Imaging Platform

Traditional Raman analysis of microplastics can be time-consuming, posing a challenge for large-scale environmental monitoring. A recently developed high-throughput platform addresses this limitation by combining a line-scan Raman imaging system with mosaic stitching to analyze entire filter surfaces [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Water samples are collected and processed. Microplastics are extracted via density separation and vacuum-filtered onto 47-mm diameter microporous filters [5].

- Data Acquisition: A flat-top line laser beam is scanned across the filter. The system performs a "mosaic stitching" operation, automatically moving the filter and acquiring Raman hyperspectral cubes for each tile until the entire filter surface is covered [5].

- Data Processing: A deep learning-based surface roughness compensation algorithm is applied to eliminate spectral interference from the filter substrate's irregularities. Object masking techniques and artificial intelligence-based classification are then used to identify and quantify the microplastics [5].

- Outcome: This system can complete a full-sample measurement and data processing within 1 hour, dramatically outperforming conventional approaches in throughput while maintaining accuracy [5].

Raman Spectroscopy and AI for Quantitative Analysis

Another advanced technique combines Raman spectroscopy with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) to enhance the detection and quantification of microplastics in diverse water environments [6].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Polyethylene (PE) microplastic beads of various sizes are mixed into different real-world water matrices. The solutions are accumulated on the surface of low-speed qualitative filter paper [6].

- Data Acquisition: Raman spectra are acquired from the samples [6].

- Data Processing & AI Analysis: A CNN is trained on a comprehensive dataset of the acquired Raman spectra. The network learns the subtle spectral features of PE microplastics and how to distinguish them from complex background signals. Other machine learning models, such as Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM), can be used for comparison [6].

- Outcome: The combined Raman-CNN method demonstrated a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.9972 and a Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) of 0.033 for identifying the concentration of PE solutions, showing significant advantages over other models [6].

Advanced Raman Techniques

To overcome the inherent weakness of the Raman signal, several enhanced techniques have been developed.

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): This technique uses nanotextured metallic surfaces (e.g., gold or silver nanoparticles) to amplify the local electric field. This amplification can enhance the Raman signal by many orders of magnitude, allowing for the detection of trace analytes [4] [7]. SERS nanoparticles (SERS NPs) can be functionalized with antibodies for highly sensitive and multiplexed molecular imaging, such as in cancer detection [7].

- Resonance Raman Spectroscopy: This occurs when the wavelength of the excitation laser is close to the electronic absorption band of a molecule. This resonance condition can increase the intensity of the Raman signal by a factor of 10⁶ to 10⁸, making it particularly useful for studying biological chromophores [4].

Raman spectroscopy's foundation in the inelastic scattering of light provides a powerful and non-destructive means of molecular fingerprinting. Its ability to provide detailed chemical information with minimal sample preparation, through transparent materials, and in aqueous environments makes it an indispensable tool in modern research. The ongoing innovation in the field—particularly the integration of high-throughput imaging platforms and artificial intelligence—is pushing the boundaries of its application. In the critical area of microplastics research, these advancements are enabling rapid, accurate, and large-scale analysis, thereby providing the robust data necessary to understand and mitigate the impact of environmental pollution.

Within the framework of Raman spectroscopy for microplastics research, two technical advantages stand out for their profound impact on experimental design and data quality: exceptional water compatibility and high spatial resolution. These characteristics are not merely convenient but are often the decisive factors in selecting Raman spectroscopy over other vibrational techniques, such as Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, particularly for the analysis of aqueous environmental samples and nanoscale plastic particles. This guide details the underlying principles, experimental methodologies, and practical applications of these advantages for researchers and scientists engaged in microplastics detection.

Water Compatibility: Enabling Direct Analysis of Aqueous Samples

A primary challenge in spectroscopic analysis is the interference caused by water, which is a major component of environmental samples. Raman spectroscopy effectively circumvents this issue.

Fundamental Principle

The core of Raman spectroscopy's water compatibility lies in its fundamental physics. Raman effect is based on the inelastic scattering of photons by molecular vibrations [8] [9]. Water molecules are relatively weak Raman scatterers, producing a broad but manageable signal in the OH-stretching region (around 3800-3100 cm⁻¹) [10]. Conversely, FT-IR spectroscopy operates on the principle of infrared light absorption and requires a change in the dipole moment of a bond [11]. Water is highly IR-active, featuring strong, broad absorption bands that can obscure the spectral signatures of target analytes, making it notoriously difficult to use with aqueous samples [11] [12].

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Microplastics in Water Using Peak Area Ratios

The weak scattering of water can be leveraged for quantitative analysis. A demonstrated method involves using the Raman peak area ratio of a characteristic microplastic peak to the broad H₂O peak to establish a calibration model [8].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare separate suspensions of polyethylene (PE) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) in deionized water across a concentration range of 0.1 wt% to 1.0 wt% [8]. To ensure homogeneity, stir the suspensions at 600 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature prior to measurement [8].

- Raman Measurement: Acquire spectra using a confocal Raman spectrometer with a 532 nm laser. Use a 5X magnification lens with a scanning area of 800 × 800 μm. Each spectrum should be collected with a measurement time of 25 seconds, averaging 20 spectra per sample for robust data [8].

- Data Analysis: Identify the characteristic peak for PE at 1295 cm⁻¹ and for PVC at 637 cm⁻¹. Also, define the area for the broad H₂O peak. Calculate the peak area ratio (Polymer Peak Area / H₂O Peak Area) for each concentration. Perform linear fitting of the peak area ratio against concentration to establish a calibration curve [8].

This method has been validated for mixed PE and PVC samples, demonstrating high linearity (R² = 0.98537 for PE; R² = 0.99511 for PVC) and providing a robust approach for quantifying microplastics in aquatic environments [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Aqueous Analysis

Table 1: Essential Materials for Microplastic Analysis in Water via Raman Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Reference Materials | Provide standard spectra for identification and quantification [9]. | PE, PP, PS, PVC particles (e.g., from Sigma-Aldrich) [5] [8]. |

| Microporous Filters | Capture microplastics from large-volume water samples for surface analysis [5]. | Opaque, microporous filters with 47-mm diameter [5]. |

| Confocal Raman Spectrometer | Enables high-resolution chemical analysis and imaging of samples [8] [13]. | Systems using 532 nm or 785 nm lasers to balance signal strength and fluorescence suppression [8] [14]. |

| Surfactant | Aids in dispersing hydrophobic microplastics in aqueous suspension to prevent agglomeration [14]. | Used in preparing particle suspensions for flow-through analysis [14]. |

High Spatial Resolution: Probing the Micro- and Nanoscale

The ability to detect and characterize increasingly smaller plastic particles is critical for understanding their environmental transport and biological impacts.

Fundamental Principle

Spatial resolution in optical microscopy is governed by the diffraction limit, which is proportional to the wavelength of the incident light. Raman microscopy typically uses visible lasers (e.g., 532 nm), which have shorter wavelengths than the mid-infrared light used in FT-IR. This allows Raman systems to achieve spatial resolutions below 1 μm, enabling the identification of sub-micron particles and even nanoplastics with advanced techniques [11] [12]. Traditional FT-IR microscopy is diffraction-limited to spatial resolutions of several to ~15 microns, making it unsuitable for particles smaller than this threshold [11].

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Analysis on Filters

A high-throughput, deep learning-based line-scan Raman platform can be employed for the comprehensive analysis of microplastics collected on filters [5].

- Sample Preparation: Collect environmental microplastics from water samples on opaque, microporous filters (47-mm diameter). Common target polymers include polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [5].

- Raman Imaging: The platform utilizes a line-scan technique combined with a mosaic stitching operation to cover the entire filter area. A flat-top line beam configuration excites the sample, and a Raman spectrometer equipped with a volumetric scattering-light confocal slit collects the hyperspectral data [5].

- Data Processing: A deep learning-based surface roughness compensation algorithm is applied to correct for signal irregularities caused by the filter substrate. Subsequent deep learning algorithms and object masking techniques enable robust classification and quantification of the microplastics [5]. This system can complete full-sample measurements and data processing for a 47-mm diameter filter in approximately 1 hour [5].

Research Reagent Solutions for High-Resolution Analysis

Table 2: Essential Materials for High-Resolution Microplastic Analysis

| Item | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Spectral Library | Essential for automated identification of polymer types based on their unique spectral fingerprint [15] [12]. | Custom libraries from pure plastics (e.g., Hawaii Pacific University kit) [16] or commercial databases (e.g., KnowItAll by Wiley) [12]. |

| Flow Cell | Allows for dynamic, high-throughput analysis of particles in liquid suspension, bypassing the need for filtration [14]. | Used in flow Raman spectroscopy to detect particles as small as ~4 μm directly in water [14]. |

| Tip-Enhanced Raman Scattering (TERS) Probe | Drastically improves spatial resolution to the nanoscale (10–30 nm) for the detection and characterization of nanoplastics [13] [9]. | A combination of Raman spectroscopy with scanning probe microscopy [13]. |

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Raman and FT-IR Spectroscopy for Microplastics Analysis

| Feature | Raman Spectroscopy | Traditional FT-IR Spectroscopy | Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Compatibility | Excellent; minimal interference from water [8] [12] [9]. | Poor; strong water absorption obscures analyte signals [11] [12]. | Enables direct analysis of aqueous samples, river water, and drinking water with minimal preparation [8] [14]. |

| Spatial Resolution | High; typically < 1 μm, can reach ~10 nm with TERS [13] [12]. | Low; diffraction-limited to several microns [11]. | Crucial for identifying small microplastics (< 20 μm) and nanoplastics, which are more biologically relevant [14]. |

| Excitation Mechanism | Change in polarizability (inelastic scattering) [11]. | Change in dipole moment (absorption) [11]. | Raman is generally more sensitive to non-polar bonds (e.g., C-C in PE/PP), while FT-IR is better for polar functional groups [11]. |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; works well in reflection mode, often requiring no preparation [11]. | Can be complex; often requires transmission mode (thin samples) or ATR contact, risking damage or contamination [11]. | Faster workflow and reduced risk of sample loss or alteration with Raman [11] [9]. |

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

Water compatibility and high spatial resolution establish Raman spectroscopy as a superior analytical technique for microplastics research in many critical applications. The ability to analyze samples in their native aqueous state and to resolve particles down to the nanoscale provides researchers with a powerful tool to accurately assess the prevalence, distribution, and potential risk of plastic pollution in the environment. As the field advances, ongoing developments in high-throughput platforms, flow-through systems, and nanoscale techniques like TERS will further solidify the role of Raman spectroscopy in environmental monitoring and toxicological studies.

The pervasive use of synthetic polymers has led to their unintended presence in biological systems and the environment, making their accurate identification a critical research objective. Polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polystyrene (PS), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) are among the most prevalent polymers, found in applications ranging from medical devices and packaging to environmental microplastics [17] [18]. Their detection and characterization within complex biological matrices and environmental samples are essential for understanding human exposure and potential health impacts. Raman spectroscopy, a non-destructive analytical technique that provides unique molecular fingerprints based on inelastic light scattering, has emerged as a powerful tool for this purpose [19]. This guide details the application of Raman spectroscopy for identifying these five critical polymers, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in microplastics research and biomedical material analysis.

Raman Spectral Characterization of Key Polymers

The identification of polymers via Raman spectroscopy relies on matching their unique vibrational fingerprints to known reference spectra. These spectra arise from the specific molecular bond vibrations within the polymer structure, allowing for precise differentiation even between visually similar materials [17] [19]. The following table summarizes the characteristic Raman bands for PE, PP, PS, PVC, and PET, which are crucial for their identification in complex samples.

Table 1: Characteristic Raman Bands of Key Biomedical and Environmental Polymers

| Polymer | Full Name | Characteristic Raman Bands (cm⁻¹) | Key Spectral Assignments |

|---|---|---|---|

| PE | Polyethylene | 1060, 1130, 1295, 1440, 2880 [20] | C-C stretching, CH₂ bending, CH₂ symmetric & asymmetric stretching [18] |

| PP | Polypropylene | 810, 840, 1000, 1160, 1450 [20] | C-C stretching, CH₃ deformation, CH₂ bending [18] |

| PS | Polystyrene | 620, 1000, 1030, 1600, 3050 [20] | Phenyl ring breathing, C-C stretching, aromatic C-H stretching [18] |

| PVC | Polyvinyl Chloride | 635, 695, 1195, 1340, 1435, 2910 [17] [18] | C-Cl stretching, CH₂ bending, CH₂ stretching [18] |

| PET | Polyethylene Terephthalate | 860, 1095, 1295, 1615, 1725, 3065 [20] | C-C stretching, C-O stretching, aromatic ring mode, C=O stretching [18] |

A critical challenge in environmental and biological research is that polymers undergo weathering, which can alter their spectral appearance. However, studies have demonstrated that while weathering may cause a slight increase in fluorescence background, the characteristic Raman bands for polymers like PE, PP, PS, PET, and PLA remain largely unchanged, allowing for identification even after environmental exposure [20]. This robustness is essential for reliable analysis of field samples.

Experimental Protocols for Raman-Based Polymer Analysis

Sample Preparation and Handling

Proper sample preparation is paramount for obtaining high-quality Raman spectra, especially for microplastics in complex matrices.

- Pristine and Weathered Polymer Reference Materials: For building a spectral library, collect pristine polymer samples from manufacturers or consumer products. To simulate environmental aging, artificially weather samples using a weathering instrument (e.g., Xenotest) following standardized protocols (e.g., EN ISO 4892-2:2013), which involve exposure to xenon-arc lamps simulating solar radiation, temperature cycles, and humidity for a set duration (e.g., 1000 hours) [20].

- Mounting: Affix solid polymer specimens or filtered particles onto standard optical glass slides (e.g., 25.4 x 76.2 x 1 mm). Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) hot glue is a suitable mounting adhesive as it provides a stable hold and its Raman spectrum is distinct from the target polymers [18].

- Microplastics in Liquid Matrices: For water samples, overcome the challenges of low abundance and microplastic hydrophobicity by employing optimized solvent dispersion and enrichment protocols. Density separation and vacuum-assisted filtration can be used to concentrate particles onto filter paper for analysis [21] [6]. For flow-through analysis, particles can be measured directly in a liquid stream, avoiding the filtration step and reducing contamination risk [20].

Raman Spectroscopy Instrumentation and Data Acquisition

The choice of instrumentation and parameters depends on the sample type and analysis goals.

Raman Microscopy: A confocal Raman microscope (e.g., WITec alpha300 R, Thermo Scientific DXR, Horiba XploRA PLUS) is ideal for analyzing single particles or mapping cross-sections of multilayer films [20] [18] [22]. Key parameters include:

- Laser Wavelength: 532 nm and 785 nm are commonly used. The 785 nm laser is often preferred for fluorescent samples as it reduces fluorescence interference [18].

- Laser Power: Adjust to avoid sample damage (e.g., 50% power or lower) [20] [22].

- Grating: A 600 g/mm grating provides a good balance of resolution and spectral range [22].

- Objective: Use a high-numerical aperture (NA) objective for spatial resolution. For depth profiling in materials with a refractive index >1.0 (e.g., many polymers), an oil immersion objective corrected for the sample's refractive index is recommended to maintain focus and signal quality [22].

- Acquisition: Typically, 50-100 scans are accumulated and averaged to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [18].

Flow Raman Spectroscopy: This method enables real-time detection and identification of microplastics in a liquid stream, significantly reducing sample preparation time [20]. The setup involves focusing a laser (e.g., 532 nm) into a microfluidic channel or a liquid jet and collecting the Raman signal from individual particles as they flow through the detection zone. This method has demonstrated the capability to identify particles as small as ~4 µm [20].

Spectral Preprocessing and Data Analysis

Raw spectral data requires preprocessing before identification.

- Preprocessing Workflow: The standard pipeline includes:

- Denoising: Apply a median filter (e.g., 15 wavenumber-wide window) to remove high-frequency noise [18].

- Baseline Correction: Use polynomial fitting (e.g., 7th order) to correct for fluorescence background [18].

- Normalization: Apply Standard Normal Variate (SNV) normalization to compare spectra from different samples on the same intensity scale [18] [23].

- Polymer Identification:

- Spectral Matching: Processed spectra from unknown samples are matched against a reference library by calculating Pearson’s correlation coefficients (r) or other similarity metrics [18]. Open-access libraries are available, containing spectra for pristine, weathered, and biological polymers to reduce false positives [18].

- Machine Learning (ML): For higher throughput and accuracy, ML models can be trained to classify spectra automatically. Common models include k-Nearest Neighbours (k-NN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), which have demonstrated high accuracy (>99% in some studies) [17] [23] [6].

Advanced Integration: Machine Learning for Enhanced Identification

The combination of Raman spectroscopy and machine learning represents a transformative advancement for the high-throughput and accurate identification of polymers, particularly in complex environmental or biological samples.

Model Selection and Performance: A variety of supervised ML models can be applied to Raman spectral data. Studies comparing models like k-Nearest Neighbours (k-NN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and Neural Networks have shown that k-NN and SVM can achieve high accuracy (e.g., 82.5% in complex multi-class scenarios) [23]. For specific quantification tasks, such as determining the concentration of PE in water, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) have demonstrated exceptional performance (R² of 0.9972) [6]. A specialized Branched PCA-Net architecture, operating on PCA-reduced spectral data with separate paths for different variance components, has been reported to achieve over 99% accuracy in classifying 10 common plastic types [17].

Explainable AI (XAI): To move beyond "black box" models, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) can be employed to interpret ML predictions. This approach reveals the specific spectral regions (e.g., near 700 cm⁻¹ and 1080 cm⁻¹) that are most critical for a model's classification decision, providing chemically meaningful insights and validating the model's logic against known polymer chemistry [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful Raman-based polymer identification workflow relies on several key reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Raman-Based Polymer Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Specific Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Polymers | Provide known spectral fingerprints for identification and library building. | Pristine pellets/sheets of PE, PP, PS, PVC, PET; artificially weathered samples [20] [18]. |

| Open-Access Spectral Library | Essential reference database for spectral matching and model training. | Libraries containing pristine, weathered anthropogenic, and biological polymers [18] [23]. |

| Optical Glass Slides | Standard substrate for mounting solid samples and filtered particles. | 25.4 x 76.2 x 1 mm slides [18]. |

| Mounting Adhesive | To affix samples securely to slides for stable measurement. | Ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) hot glue [18]. |

| Immersion Oil | Used with oil immersion objectives to correct for refraction artifacts in depth profiling. | Select oil to match the refractive index of the polymer sample (~1.5 for many) [22]. |

| Density Separation Reagents | To separate and concentrate microplastics from complex environmental samples. | High-density salt solutions (e.g., NaCl, ZnCl₂) [21] [24]. |

| Surfactants | To disperse hydrophobic microplastic particles in aqueous suspensions. | Added to water to prevent agglomeration of particles for flow spectroscopy [20]. |

| Microfluidic Chips | Core component for flow-through Raman measurements, enabling real-time analysis. | Custom or commercial chips for particle focusing and interrogation [20] [24]. |

Raman spectroscopy, particularly when enhanced with robust sample preparation protocols, advanced spectral libraries, and machine learning, provides a powerful and non-destructive analytical framework for identifying critical polymers like PE, PP, PS, PVC, and PET. The methodologies outlined in this guide—from fundamental spectral characterization to advanced flow systems and explainable AI—offer researchers a comprehensive toolkit for accurate polymer identification in complex biomedical and environmental contexts. As the field progresses, the integration of these techniques will be pivotal in advancing our understanding of polymer life cycles, exposure pathways, and potential health impacts, thereby supporting the development of evidence-based mitigation strategies and policies.

The pervasive spread of microplastics (MPs), defined as plastic particles ranging from 1 μm to 5 mm, represents one of the most significant environmental challenges of our time [25]. These particles are now ubiquitously present in aquatic and terrestrial environments, often finding their way into food, drink, and even human tissues [25] [26]. A realistic assessment of their ill effects must commence with large-scale analysis of their abundance, size distribution, and chemical composition—a task requiring sophisticated analytical tools [25]. Among these tools, Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful technique for microplastic identification, particularly for particles smaller than 20 μm where other techniques like FT-IR spectroscopy become inadequate [25] [20]. However, the full potential of Raman spectroscopy in microplastics research remains hampered by a critical limitation: the lack of standardized protocols across laboratories and instrument platforms. This whitepaper examines the sources of variability in Raman analysis of microplastics, outlines emerging solutions for protocol harmonization, and provides detailed methodologies to guide researchers toward more reproducible and comparable results.

Analytical Advantages of Raman Spectroscopy in Microplastics Research

Raman spectroscopy offers several distinct advantages for microplastic analysis that make it particularly suitable for environmental monitoring and toxicological studies. The technique is based on the inelastic scattering of light that provides information about molecular vibrations in the form of a vibrational spectrum, which serves as a unique fingerprint for chemical identification [25]. Key advantages include:

- Superior spatial resolution: Raman techniques show better spatial resolution (down to 1 μm) compared to FT-IR spectroscopy (10–20 μm), enabling identification of smaller microplastic particles [25].

- Minimal water interference: Unlike FT-IR, Raman spectroscopy experiences less interference from water molecules, making it more suitable for analyzing aqueous samples without extensive preparation [8].

- Non-destructiveness: The technique preserves samples for additional analysis, an important consideration for precious environmental samples or time-series studies [25].

- Sensitivity to non-polar groups: Raman spectroscopy demonstrates higher sensitivity to non-polar functional groups common in many polymers [25].

These advantages are particularly relevant for detecting the smallest microplastics (<20 μm), which are absorbable by organs and can cross the blood-brain barrier, posing potential health risks [20]. However, realizing these advantages consistently across different laboratories and studies requires addressing significant methodological challenges.

Critical Gaps in Current Methodological Standards

The comparability of microplastic data across studies is compromised by multiple sources of variability inherent in current Raman methodologies:

- Instrument-dependent intensity variations: The Raman signal intensity depends on numerous factors including laser wavelength, optical components, detector quantum efficiency, and laser amplitude [27]. These variations make direct comparison of spectra from different instruments challenging without proper normalization.

- Fluorescence interference: Raman spectroscopy is prone to fluorescence interference, which can be intrinsic to the MP constituent or due to impurities like coloring agents, biological material, and degradation products [25].

- Spectral library inconsistencies: Automated μ-Raman routines employ library matching software, but successful matching depends heavily on the comprehensiveness of spectral libraries [25]. Most libraries rely on spectra from pristine polymers, which may differ significantly from environmentally aged microplastics [25].

- Sample preparation heterogeneity: Methods for sample collection, filtration, and measurement vary considerably across studies, affecting the reproducibility of results [20].

Consequences of Methodological Inconsistency

Without standardized protocols, the field faces significant challenges in data comparison, reliability, and regulatory application. The current situation leads to:

- Incomparable data sets: Research findings from different groups cannot be reliably compared or aggregated for larger-scale analysis.

- Uncertain quality control: Quality control of food and drinking water requires substantial effort with current methods [20].

- Impeded policy development: The lack of standardized, reproducible methods hampers the development of evidence-based regulations and monitoring programs.

Emerging Protocols for Raman Spectroscopy Standardization

Device Twinning for Intensity Harmonization

A promising approach for standardizing Raman measurements across different instruments is the concept of "device twinning." A 2024 study proposed a protocol to twin Raman devices by obtaining a correction factor that relates differences in signal intensity between two Raman devices [27]. The protocol involves:

- Reference material: Using a homogeneous and reproducible reference sample that ensures a unique and consistent Raman cross-section. Researchers developed a composite material of epoxy with 0.5% by weight of anatase titanium dioxide (TiO₂) particles, which shows deviations <2.5% in Raman intensity across the reference material [27].

- Intensity correlation: Establishing a mathematical relationship between the signal intensities of different instruments using the reference material.

- Signal conversion: Applying a correction factor to harmonize Raman spectra between different devices, enabling comparable intensity counts [27].

This approach allows for the harmonization of Raman spectra and increases interoperability between different instruments, applications, and industries without requiring calculation of all parameters that influence Raman intensity.

Quantitative Analysis Using Peak Area Ratios

For quantitative analysis of microplastics in water, a novel method utilizing peak area ratios has demonstrated high accuracy and linearity. This approach, validated in a 2024 study, uses the following methodology [8]:

- Internal reference: The broad H₂O peak serves as an internal standard for normalizing signal variations.

- Characteristic peaks: Raman peak area ratios of 1295 cm⁻¹ for polyethylene (PE) and 637 cm⁻¹ for polyvinyl chloride (PVC) relative to the water peak establish a calibration model.

- Concentration range: The method has been validated for microplastic concentrations ranging from 0.1 wt% to 1.0 wt% in deionized water [8].

The calibration model demonstrated impressive statistical performance, as summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Quantitative Raman Analysis for Microplastics

| Polymer Type | Characteristic Peak (cm⁻¹) | R² Value | Linear Range (wt%) | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) | 1295 | 0.98537 | 0.1-1.0 | High linearity |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | 637 | 0.99511 | 0.1-1.0 | High linearity |

| Mixed PE/PVC | Multiple | Low SEC* and %RSEC* | 0.1-1.0 | Accurate prediction |

SEC: Standard Error of Calibration; RSEC: Relative Standard Error of Calibration [8]

Multivariate Analysis for Automated Identification

The integration of multivariate analysis with Raman spectroscopy has shown great promise for standardizing and automating microplastic identification. A 2022 study demonstrated:

- High-accuracy classification: Support vector machine (SVM) classification achieved an accuracy rate of over 98% for polypropylene (PP), polyethylene terephthalate (PET), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polycarbonate, polyamide, and over 70% for high-density polyethylene and low-density polyethylene [28].

- Robustness to environmental stress: Even after exposure to environmental stressors, the developed SVM classification maintained an accuracy of 96.75% in real-world scenarios [28].

- Distinction of aged plastics: Principal component analysis (PCA) and linear discriminant analysis (LDA) could distinguish microplastic types even after artificial aging [28].

This approach reduces the subjectivity in manual spectral interpretation and enhances throughput while maintaining accuracy.

Flow Raman Spectroscopy for Standardized Sampling

Flow-through measurement systems represent a significant advancement for standardizing microplastic analysis by minimizing sample preparation variability. Recent developments demonstrate:

- Elimination of filtration steps: Measuring particles directly in the liquid avoids the contamination-prone and time-consuming process of sample filtering [20].

- Real-time capability: Flow systems allow for real-time and continuous measuring applications, enabling more representative sampling [20].

- Small particle detection: Recent systems can detect and identify ≈4 μm-sized microplastics in flow, addressing the critical size range of particles that can cross biological barriers [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Reproducible Analysis

Protocol 1: Quantitative Analysis of Microplastics in Water

Based on the 2024 study by Nature, the following protocol enables quantitative analysis of microplastics in aqueous samples [8]:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Quantitative Raman Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Polyethylene (PE) particles | Sigma-Aldrich, spherical white particles, 40-48 μm | Target analyte for method development |

| Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) particles | Sigma-Aldrich, spherical white particles, 40-100 μm | Target analyte for method development |

| Deionized (DI) water | N/A | Dispersion medium for microplastics |

| Confocal Raman spectrometer | XperRam C series (Nanobase Inc.), 532 nm laser, 5X magnification lens | Spectral acquisition |

Procedure:

- Prepare separate samples of PE with DI water and PVC with DI water at varying concentrations (0.1 wt% to 1.0 wt%).

- Adjust concentration based on weight, using 10 mL of DI water (density set to 1.0).

- Stir mixtures at 600 rpm for 30 minutes at room temperature to ensure dispersion of insoluble particles.

- Obtain Raman spectra using a confocal Raman spectrometer with 5X magnification lens and 30 mW, 532 nm laser.

- Set scanning area to 800 × 800 μm, measurement time to 25 s, and collect 20 spectra per sample.

- For data analysis, average the 20 measured spectra using the Gaussian method.

- Calculate Raman peak area ratios of characteristic peaks (1295 cm⁻¹ for PE, 637 cm⁻¹ for PVC) relative to the broad H₂O peak.

- Establish calibration model using linear fitting with the peak area ratio versus concentration.

Protocol 2: Device Twinning for Inter-Laboratory Comparability

Based on the 2024 twinning protocol, the following methodology enables harmonization between different Raman instruments [27]:

Materials:

- Reference sample: Homogeneous dispersion of 0.5 wt% anatase (titanium dioxide, TiO₂) in an epoxy resin matrix

- Raman devices to be twinned

- Standard samples for validation

Procedure:

- Manufacture reference sample with composite material of epoxy and 0.5% by weight of anatase TiO₂ particles deposited on a transparent polystyrene support.

- Measure the reference sample with both Raman devices using identical measurement parameters (laser power, integration time, etc.).

- Collect multiple spectra from different areas of the reference sample to account for heterogeneity.

- Calculate the average intensity of characteristic TiO₂ peaks for each device.

- Determine the correction factor by comparing the intensity responses between the two devices.

- Apply this correction factor to convert signal intensity between the twinned devices.

- Validate the twinning process using standard samples with known Raman cross-sections.

Protocol 3: Flow Raman Spectroscopy for Minimal Sample Preparation

Based on the 2025 flow Raman spectroscopy study, the following protocol enables standardized analysis of microplastics in liquid samples without filtration [20]:

Materials:

- Raman spectrometer with flow cell attachment

- 532 nm laser source

- Peristaltic pump for controlled flow rates

- Liquid samples potentially containing microplastics

Procedure:

- Set up the flow-through measurement system with appropriate tubing and flow cell.

- Calibrate the system using research particles of known size and composition (e.g., PS and PMMA particles).

- Adjust flow rate to ensure particles pass through the detection volume at a measurable rate.

- Use a 532 nm laser for excitation and collect Raman spectra of individual particles as they flow through the detection volume.

- Apply particle recognition algorithms to identify Raman spectra belonging to particles versus background.

- Compare acquired spectra against reference libraries for identification.

- For quantitative analysis, correlate particle count with concentration using established calibration curves.

Implementation Roadmap and Future Directions

The path toward fully standardized Raman spectroscopy protocols for microplastic analysis requires coordinated efforts across multiple stakeholders. The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for standardized microplastic analysis using Raman spectroscopy:

Figure 1: Integrated Workflow for Standardized Microplastic Analysis Using Raman Spectroscopy

Priority Actions for Implementation

- Reference Material Development: Widespread adoption of certified reference materials for intensity calibration and device twinning [27].

- Interlaboratory Studies: Collaborative ring trials to validate proposed protocols across different instrument platforms and sample types.

- Spectral Library Expansion: Development of comprehensive, open-access spectral libraries that include environmentally aged microplastics and common additives [25].

- Data Format Standardization: Establishment of uniform data reporting standards including minimum information about Raman experiments.

Emerging Techniques Requiring Standardization

As Raman technology advances, new techniques show promise for microplastic analysis but will require standardized protocols:

- Flow Raman systems for continuous monitoring [20]

- Hyperspectral Raman imaging for high-throughput analysis [25]

- Advanced multivariate analysis incorporating machine learning algorithms [28]

- Integrated spectroscopic approaches combining Raman with complementary techniques like FT-IR [26]

The establishment of standardized protocols for Raman spectroscopy in microplastics research is no longer a scientific luxury but an urgent necessity. As evidence grows about the pervasive nature of microplastic pollution and its potential impacts on ecosystem and human health, the need for comparable, reproducible data becomes increasingly critical. The protocols outlined in this whitepaper—device twinning for intensity harmonization, quantitative analysis using peak area ratios, multivariate analysis for automated identification, and flow systems for standardized sampling—represent significant steps toward this goal. By adopting and refining these methodologies, the research community can accelerate our understanding of microplastic pollution and develop effective strategies to address this global challenge. The path forward requires collaborative effort, but the tools for standardization are now within reach.

Advanced Methodologies and High-Throughput Applications

In microplastics research, the accuracy of results obtained through advanced techniques like Raman spectroscopy is fundamentally dependent on the quality of sample preparation. Without proper protocols to isolate and purify microplastic particles from complex environmental matrices, even the most sophisticated analytical instruments cannot deliver reliable data. This guide details the standardized procedures for preparing freshwater, sediment, and biological samples, forming the critical foundation for any rigorous microplastics study using Raman spectroscopy.

Sample Collection and Initial Processing

The first phase of microplastics analysis involves collecting samples from various environmental compartments with minimal contamination.

Water Sampling

- Protocol: Collect surface water using a manta trawl net, typically equipped with a 333-μm mesh, towed at low speed for standardized distances to quantify volume sampled [29].

- Purpose: This method efficiently concentrates buoyant microplastics from large water volumes, providing a representative sample of surface water contamination.

Sediment Sampling

- Protocol: Use a benthic grab sampler (such as Van Veen or Ponar grabs) to collect sediment from standardized depths and locations [29].

- Purpose: Preserves the stratification of sediment layers, allowing analysis of how microplastics accumulate in benthic environments over time.

Biological Sampling

- Protocol: For fish, dissect to isolate the entire gastrointestinal tract. Place organs in pre-cleaned glass containers and freeze at -20°C until processing [29].

- Purpose: This approach captures all microplastics ingested by the organism, which is essential for studying trophic transfer and biological impacts.

Sample Pretreatment and Digestion

Organic matter in samples can obscure microplastics during Raman analysis. Controlled digestion eliminates this interference while preserving synthetic polymers.

Table 1: Common Chemical Digestion Reagents for Organic Matter Removal

| Reagent Type | Typical Concentration | Application Context | Key Advantages | Potential Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | 30-35% | Water, sediment, and biological samples | Less destructive to sensitive polymers; minimal chemical residue [29] | Slower digestion for recalcitrant tissues |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | 10% | Biological tissues (fish guts) | Effective for digesting complex organic matrices [30] | Potential degradation of some polymers like PET |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | - | Dense organic matter | Powerful oxidizing agent for resistant materials | Risk of polymer degradation at high temperatures |

| Enzymatic Digestion | - | Delicate samples | Highly specific; preserves particle integrity [30] | Higher cost; longer processing time |

Standard Digestion Protocol for Biological Tissues

- Transfer the gastrointestinal tract to a glass beaker.

- Add 10% KOH solution at approximately 1:10 (w/v) sample-to-reagent ratio [29].

- Incubate at 60°C for 24-72 hours with occasional gentle agitation.

- Cool to room temperature before proceeding to separation.

Density Separation

Following digestion, density separation isolates microplastics from remaining inorganic debris based on buoyancy differences.

- Reagent: Sodium chloride (NaCl) solution at density of 1.2 g/cm³ is commonly used [29].

- Procedure:

- Transfer digested sample to separation funnel.

- Add saturated NaCl solution at 1:5 sample-to-solution ratio.

- Stir gently and let stand for several hours.

- Collect supernatant containing floating microplastics.

- Repeat separation 2-3 times to maximize recovery.

Filtration Techniques

Filtration concentrates microplastics onto a substrate compatible with Raman spectroscopic analysis.

Table 2: Filter Selection Guide for Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

| Filter Characteristic | Options | Considerations for Raman Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Material | Silicon, Aluminum Oxide, Glass Fiber, Gold-coated | Silicon filters recommended for minimal background interference in Raman spectra [30] |

| Pore Size | 0.45 μm - 20 μm | Smaller pores (≤1.2 μm) retain more particles but increase analysis time [30] |

| Size | 13 mm - 47 mm diameter | Driven by particle concentration and Raman microscope stage compatibility [30] |

| Color | White preferred | Enhances contrast for visual particle location before Raman analysis [30] |

Vacuum Filtration Protocol

- Assemble filtration apparatus with selected filter.

- Transfer density-separated supernatant to funnel.

- Apply vacuum gently to avoid damaging fragile particles.

- Rinse container with distilled water to transfer all particles.

- Air-dry filter in covered Petri dish to prevent contamination.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the complete sample preparation journey from collection to Raman-ready filter:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microplastics Sample Preparation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | Digest organic biological material | 10% solution in distilled water; incubation at 60°C [29] |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Oxidize organic matter in water/sediment | 30-35% concentration; may be combined with heating [29] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Density separation of microplastics | Saturated solution (density ~1.2 g/cm³); cost-effective [29] |

| Silicon Filters | Substrate for Raman analysis | Low fluorescence background; compatible with automated particle detection [30] |

| Video Raman Matching (VRM) Stage | Precise particle relocation | Patented NanoGPS technology for confident particle localization [30] |

| Microplastics Standard | Quality control validation | Set of tablets with known polymer particles to validate workflow [30] |

Quality Assurance and Contamination Control

Implementing rigorous quality control measures throughout sample preparation is essential for generating reliable data.

- Field Blanks: Expose clean filters to air during sampling to assess airborne contamination [29].

- Laboratory Blanks: Process negative controls (distilled water) through all preparation steps [29].

- Recofficiency Testing: Use microplastic standards with known particle sizes and polymer types to validate each batch [30].

- Cotton Lab Coats: Required instead of synthetic fabrics to minimize fiber contamination [29].

- Glassware Preference: Use glass containers instead of plastic whenever possible [29].

The filtration selection process is critical for optimizing downstream Raman analysis, as illustrated below:

Meticulous sample preparation spanning filtration to chemical digestion forms the cornerstone of credible microplastics research using Raman spectroscopy. The protocols detailed in this guide—from matrix-specific collection techniques through optimized digestion, separation, and filtration—enable researchers to produce contaminant-free samples with high microplastic recovery. This rigorous foundation ensures that subsequent Raman analysis delivers the precise, reliable polymer identification necessary for understanding microplastic pollution sources, fate, and impacts across aquatic ecosystems. As Raman technologies advance with machine learning integration and automation, standardized sample preparation becomes increasingly vital for generating comparable data across studies and informing effective mitigation strategies.

High-throughput Raman imaging has emerged as a critical analytical technique for researchers confronting the challenge of rapidly characterizing samples across large areas, particularly in fields such as microplastics research and biomedical analysis. Conventional single-point Raman mapping techniques require prohibitively long acquisition times when analyzing extensive sample regions, creating a significant bottleneck in analytical workflows. The integration of line-scan techniques with advanced mosaic stitching algorithms addresses this limitation by dramatically accelerating data acquisition while maintaining high spatial and spectral resolution. This technical guide explores the core principles, methodologies, and applications of these advanced Raman imaging approaches, with particular emphasis on their implementation within microplastics research.

Core Principles of Line-Scan Raman Imaging

Line-scan Raman imaging represents a fundamental advancement beyond traditional single-point spectroscopy. Rather than collecting spectra from individual points sequentially, this technique illuminates samples with a laser shaped into a flat-top line beam, enabling simultaneous spectral acquisition across an entire line of points [5]. This approach effectively transforms one dimension of spatial scanning into parallel detection, thereby significantly reducing image acquisition times.

The underlying optical configuration typically involves a cylindrical lens or diffractive optical element that transforms the Gaussian laser profile into a uniform line focus. This line is then imaged onto a spectrometer equipped with a two-dimensional detector, with one dimension capturing spatial information along the line and the other capturing spectral data. The key advantage of this configuration is its ability to obtain Raman spectral information from multiple adjacent points simultaneously, dramatically improving acquisition efficiency compared to point-scanning systems [5].

For microplastics research, this capability is particularly valuable when analyzing environmental samples deposited on filtration membranes, where particles are distributed across large surface areas. The line-scan approach enables comprehensive screening of entire filters in practical timeframes, facilitating the high-throughput analysis required for meaningful environmental monitoring [5].

Mosaic Stitching Methodologies

The combination of line-scanning with mosaic stitching creates a powerful framework for large-area Raman imaging. Two primary stitching methodologies have been developed, each with distinct advantages and implementation considerations.

Strip-Scan Mosaicing

Strip-scan mosaicing operates by continuously translating a sample stage perpendicular to the orientation of the laser line while maintaining constant acquisition [31] [32]. This approach effectively creates elongated image strips that can be assembled to cover extensive sample areas. The synchronization between stage motion and data acquisition is critical for maintaining spatial fidelity and minimizing distortion.

In a demonstrated implementation for tissue imaging, researchers achieved a nearly 10-fold reduction in total imaging time for a whole mouse brain section compared to conventional tiling methods [32]. This efficiency gain stems from the elimination of dead time between adjacent fields of view that plagues traditional tiling approaches.

A significant innovation in this domain is scanner-synchronous position sampling, which addresses the challenge of non-uniform stage velocity [31]. By reading out precision stage encoders synchronously with the line-scan trigger, this technique achieves subwavelength positional accuracy for each acquired line, enabling computational dewarping that corrects for velocity variations during stage motion [31].

Tile-Scan Stitching with Image Registration

As an alternative to continuous strip scanning, tile-scan stitching acquires discrete rectangular fields of view that are subsequently computationally assembled into a mosaic. This approach benefits from advanced image registration algorithms that identify overlapping regions between adjacent tiles to determine their precise relative positions [33].

In one implementation for bacterial analysis, researchers developed an automated stitching process that includes image identification, registration, global optimization, and blending stages [33]. This method enabled the detection and analysis of thousands of individual bacterial cells across multiple stitched fields of view, demonstrating the power of automated large-area analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Mosaic Stitching Methodologies

| Feature | Strip-Scan Mosaicing | Tile-Scan Stitching |

|---|---|---|

| Acquisition Efficiency | High (minimal dead time between FOVs) | Moderate (dead time during stage repositioning) |

| Geometric Accuracy | Requires velocity synchronization or position encoding [31] | High (discrete stage movements) |

| Computational Complexity | Lower (unidirectional stitching) | Higher (2D registration and blending) |

| Implementation Complexity | Requires precise stage-scan synchronization | Simplified synchronization requirements |

| Best Suited Applications | Large, continuous samples | Discontinuous samples or predefined regions |

Technical Specifications and Implementation

Implementing high-throughput Raman imaging requires careful consideration of multiple technical parameters that collectively determine system performance.

Detection System Configuration

Modern line-scan Raman systems employ advanced detector technologies to maximize signal collection efficiency. Silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs) have emerged as superior alternatives to conventional photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) for high-throughput applications, offering higher quantum efficiency at red and NIR wavelengths, negligible excess noise, and significantly higher saturation power [31]. One implementation demonstrated that SiPM-based detection electronics enabled more than an order of magnitude increase in photon throughput compared to conventional PMTs [31].

The optical configuration typically incorporates high-numerical-aperture (NA) objectives to maximize photon collection, though this often trades off against field of view. For example, in a specialized multiwell Raman plate reader system, researchers implemented an array of 192 semispherical lenses with NAs of 0.51 arranged to match the well spacing of a standard 384-well plate, enabling simultaneous measurement of all wells while maintaining high collection efficiency [34].

Spatial and Spectral Resolution Parameters

The performance characteristics of line-scan Raman systems must balance multiple competing parameters:

- Spatial resolution: Typically diffraction-limited, with demonstrated systems achieving approximately 1.8 μm lateral resolution [34]

- Spectral resolution: Ranging from 5-10 cm⁻¹, sufficient to distinguish polymer-specific Raman bands

- Acquisition rates: Line-scan systems can achieve rates exceeding 5 MP/s while maintaining sufficient signal-to-noise for material identification [31]

Table 2: Technical Specifications of Demonstrated High-Throughput Raman Systems

| Parameter | Line-Scan System for Microplastics [5] | Strip-Scan Two-Photon System [32] | Multiwell Plate Reader [34] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Range | Not specified | 2845 cm⁻¹ & 2930 cm⁻¹ (lipid/protein) | Full Raman spectrum |

| Spatial Resolution | Sufficient for <5 μm particles | Diffraction-limited | ~1.8 μm |

| Field of View | 47-mm diameter filters | 12 × 7 mm² tissue section | 192 wells simultaneously |

| Acquisition Time | <1 hour for full filter | 8 minutes for large tissue | 20 seconds for 192 samples |

| Laser Parameters | Not specified | 1040 nm Stokes, OPO pump (690-1300 nm) | Not specified |

Experimental Protocols for Microplastics Analysis

The application of high-throughput Raman imaging to microplastics research follows a structured workflow from sample preparation to data analysis.

Sample Preparation and Deposition

Environmental microplastics samples are typically collected via filtration onto membrane filters. For Raman analysis, opaque microporous filters with 47-mm diameter have been successfully employed, with the line-scan system configured to accommodate these standard formats [5]. Sample pre-processing may include density separation to remove inorganic contaminants and oxidative treatments to remove organic matter, though some studies indicate that oxidative treatment may not fully eliminate interference from certain pigments [16].

For controlled studies, reference microplastics can be prepared from commonly occurring polymers, including polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and polystyrene (PS), with particle sizes ranging from 1-100 μm to simulate environmental conditions [5]. These reference materials enable system validation and calibration.

System Calibration and Validation

Prior to sample analysis, system calibration ensures accurate spectral and spatial measurements:

- Spectral calibration: Perform using known reference standards (e.g., silicon peak at 520 cm⁻¹)

- Spatial calibration: Verify using standardized gratings or reference patterns with known feature sizes

- Intensity calibration: Normalize system response using a reference material with consistent Raman cross-section

For quantitative analysis, researchers have developed calibration models based on Raman peak area ratios relative to internal standards. For example, one study established a linear relationship (R² = 0.985-0.995) between peak area ratios and microplastic concentration in the range of 0.1-1.0 wt% [8].

Data Acquisition Parameters

Optimal acquisition parameters balance signal quality with throughput:

- Laser power: Typically 5-100 mW at the sample, depending on particle size and sensitivity

- Integration time: Ranges from 20-100 ms per line for microplastics on filters [5]

- Spectral range: 500-3200 cm⁻¹ to capture fingerprint and C-H stretching regions

- Spatial sampling: 1-2 μm step size sufficient for microplastic identification

Data Processing and Analysis

The substantial datasets generated by high-throughput Raman imaging require sophisticated processing pipelines:

- Spectral preprocessing: Includes cosmic ray removal, background subtraction, and intensity normalization

- Spatial reassembly: Stitching of individual strips or tiles using position encoder data or image registration algorithms

- Chemical identification: Correlation of sample spectra with reference libraries using correlation algorithms or machine learning classifiers

- Morphological analysis: Particle sizing, counting, and shape classification

Advanced implementations incorporate deep learning algorithms to compensate for substrate irregularities and improve classification accuracy on complex environmental samples [5]. These algorithms can achieve robust identification even when microplastics are mixed with natural debris and fibrous materials.

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for high-throughput Raman analysis of microplastics:

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of high-throughput Raman imaging requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the application domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Microplastics Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Microplastics | System calibration and validation | PE, PP, PS particles (1-100 μm) [5] |

| Microporous Filters | Sample substrate for filtration | Opaque membranes (47-mm diameter) [5] |

| Density Separation Solutions | Inorganic material removal | Sodium chloride or sodium iodide solutions |

| Oxidative Reagents | Organic matter removal | Hydrogen peroxide, Fenton's reagent [16] |

| Silicon Photomultipliers (SiPMs) | High-sensitivity Raman detection | Replacement for conventional PMTs [31] |

| Position Encoder Systems | Spatial registration for stitching | Optical encoders with subwavelength resolution [31] |

Technical Challenges and Limitations

Despite its significant advantages, high-throughput Raman imaging faces several technical challenges that require consideration:

Fluorescence Interference

The presence of fluorescent colorants, particularly in colored microplastics, can overwhelm the weaker Raman signal. While oxidative treatments can reduce some organic fluorescence, studies show that certain pigments, especially red colorants, continue to cause significant interference that cannot be fully eliminated through standard treatments [16].

Computational Requirements

The large datasets generated by high-throughput systems demand substantial computational resources for processing and analysis. A single 47-mm filter scan can generate gigabytes of spectral data, requiring efficient algorithms for preprocessing, stitching, and classification [5].

Sensitivity Limitations

While line-scanning improves throughput, it can reduce residence time per spatial element compared to point-scanning, potentially limiting sensitivity for weakly scattering samples or small particles (<1 μm). Advanced detectors with high quantum efficiency and low noise help mitigate this limitation [31].

High-throughput Raman imaging combining line-scan techniques with mosaic stitching represents a transformative approach for large-area sample analysis, particularly in the field of microplastics research. The methodologies detailed in this guide enable complete characterization of samples spanning square centimeters within practical timeframes, dramatically improving analytical efficiency compared to conventional approaches. As detector technologies, motion control systems, and data processing algorithms continue to advance, these techniques will play an increasingly vital role in environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and materials characterization. The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence for spectral classification and morphological analysis promises to further enhance the utility and accessibility of these powerful analytical tools.

Innovative Flow Raman Spectroscopy for Real-Time Particle Analysis

Flow Raman spectroscopy represents a significant advancement in analytical techniques for real-time particle analysis, particularly in the field of microplastics research. This method combines the chemical specificity of conventional Raman spectroscopy with the high-throughput capabilities of flow-based systems, enabling the detection and identification of individual particles in a liquid stream without the need for complex sample preparation [20]. Unlike static measurements that require filtering and manual transfer to a substrate, flow-through measuring systems allow particles to be analyzed directly in their liquid medium, dramatically reducing the risk of contamination and opening possibilities for continuous, autonomous monitoring [20] [35]. For microplastics research, this technology offers a powerful solution to one of the field's most pressing challenges: the efficient detection of small particles—some smaller than 10 µm—that can cross biological barriers and potentially impact human health [20].

The fundamental principle underlying this technique is straightforward: a liquid sample containing particles is hydrodynamically focused and passed through a laser beam, where Raman scattering occurs. The scattered light is then collected and analyzed to provide a chemical fingerprint of each particle [20] [35]. This approach is especially valuable for environmental monitoring, quality control in food and pharmaceutical industries, and toxicological studies where rapid, reliable identification of particulate contaminants is essential.

Technical Foundations and Instrumentation

Core Components of a Flow Raman System

A typical flow Raman spectroscopy system consists of several integrated components that work together to enable real-time particle analysis. The excitation source is typically a laser, with common wavelengths including 532 nm [20] and 785 nm [35] chosen to balance signal strength and fluorescence minimization. The laser light is directed through a series of optical elements—including bandpass filters to remove fiber-induced fluorescence [35]—and focused into the flow cell where particle interrogation occurs.

The flow cell itself is a critical component, often consisting of a quartz capillary tube with thin walls to optimize light transmission [35]. The choice of flow cell material and geometry significantly impacts signal collection efficiency. For biological applications, a water immersion objective is often employed to better match the refractive indices at the blood/quartz and water interfaces, resulting in higher Raman signal collection [35]. The scattered light is then passed through a series of filters to remove the dominant Rayleigh component before being coupled into a spectrometer for dispersion and detection, typically using a CCD detector [35] [36].

A key advantage of the flow-based approach is the controlled exposure time of particles to the laser. By adjusting flow rates, researchers can ensure that particles remain in the laser focal spot for optimal durations—typically milliseconds to seconds—preventing photodamage while maintaining adequate signal-to-noise ratios [35] [36]. This is particularly important for analyzing sensitive biological samples or materials prone to laser-induced degradation.

Detection Principle and Workflow

The analytical process in flow Raman spectroscopy follows a structured sequence from particle introduction to chemical identification. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and detection principle:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of flow Raman spectroscopy requires specific reagents and materials tailored to the application. The following table details essential components for microplastics research:

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Flow Raman Analysis of Microplastics

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Particles [20] | System calibration & validation | Polystyrene (PS) & polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) spheres (1-100 µm) ideal for determining detection limits |

| Surfactants [20] | Particle dispersion | Prevents aggregation in liquid suspension; ensures single-particle flow |

| Filter Membranes [5] | Sample preparation | Various pore sizes (e.g., 47-mm diameter membranes) for pre-concentration |

| Quartz Flow Cells [35] | Sample containment | Boron-rich quartz with 1.5 mm internal diameter provides optimal optical properties |

| Calibration Standards [37] | Spectral validation | Acetaminophen tablet & NIST SRM 2241 for x-axis and y-axis calibration |

For specialized applications such as blood analysis, additional reagents are required. For instance, hydrogen peroxide solutions are used to induce oxidative stress in blood samples for studying antioxidant capacity [35], while EDTA vacutainer tubes are essential for proper blood collection and preservation [35].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Techniques

Proper sample preparation is critical for obtaining reliable flow Raman results. For microplastics analysis, researchers have developed several approaches to generate representative particles. Research-grade spherical particles made of PS and PMMA with tightly controlled size distributions (e.g., 3.97 ± 0.06 µm) are commercially available and ideal for system validation and detection limit studies [20]. These monodisperse suspensions provide a benchmark for evaluating system performance.

For more application-relevant studies, environmentally representative particles can be generated through abrasion techniques. Dry-abraded particles are produced by sanding injection-molded plastic plates and collecting the resulting fragments, which are then dispersed in water with a surfactant and filtered to remove large aggregates [20]. Wet abrasion methods utilizing ultrasound-induced cavitation in an ultrasonic bath provide an alternative approach for generating particles that mimic real-world degradation processes [20]. Additionally, spherical microparticles can be produced through melt dispersion techniques using a twin-screw extruder, where plastics are mixed with water-soluble polyethylene glycol (PEG) and subsequently isolated through dissolution and filtration [20].

For biological samples like blood lysate, specific protocols must be followed. Peripheral blood is typically drawn into EDTA vacutainer tubes, aliquoted, rocked at room temperature for several hours, and then frozen at -80°C to induce hemolysis [35]. After thawing overnight at 4°C, the lysate is gently mixed and drawn into a syringe for flow analysis [35]. This standardized preparation ensures reproducible results while maintaining biological relevance.

System Operation and Data Acquisition

The operational parameters for flow Raman spectroscopy must be carefully optimized for each application. Laser power density typically ranges from 0-165 kWcm⁻² at the sample focal plane, with specific settings determined by the sample's sensitivity to photodamage [35]. Integration times—the duration for which a single spectrum is recorded—vary from milliseconds to seconds, with longer times improving signal-to-noise ratio but increasing the risk of detector saturation or sample alteration [36].

Flow rates must be adjusted to ensure an appropriate dwell time in the laser spot. For blood lysate analysis, a dwell time of 0.4 seconds with a power density below 0.2 MWcm² has been shown to avoid photodamage while maintaining adequate signal quality [35]. The flow rate also affects the particle presentation rate, with optimal conditions ensuring that particles pass through the laser focus singly rather than in clusters.