Raman Spectroscopy for Optical Window Contaminant Analysis: Techniques, AI Applications, and Best Practices for Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Raman spectroscopy for identifying and analyzing contaminants on optical windows, a critical issue in pharmaceutical development and high-precision research.

Raman Spectroscopy for Optical Window Contaminant Analysis: Techniques, AI Applications, and Best Practices for Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Raman spectroscopy for identifying and analyzing contaminants on optical windows, a critical issue in pharmaceutical development and high-precision research. It explores the foundational principles of how Raman spectral fingerprints uniquely identify unknown materials, such as rubidium silicate on vapor cells. The scope extends to established and emerging methodologies, including laser cleaning and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) for trace detection. A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting spectral contaminants and ensuring instrument stability for reliable data. Finally, the review covers validation protocols and performance comparisons with techniques like LIBS and IR spectroscopy, highlighting how AI integration is revolutionizing spectral analysis for improved accuracy and efficiency in biomedical applications.

Unveiling the Contaminant: Foundational Principles and Common Culprits in Optical Systems

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique for identifying molecular contaminants in various research and industrial settings. This guide explores its application in detecting unknown contaminants on optical surfaces, comparing its performance with alternative methods, and detailing the experimental protocols that ensure reliable results.

The Principle of the Molecular Fingerprint

Raman spectroscopy operates on the principle of inelastic light scattering. When monochromatic light interacts with a molecule, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering). However, a tiny fraction (approximately 1 in 10⁷ photons) undergoes inelastic scattering, resulting in a shift in energy that corresponds to the vibrational modes of the molecular bonds [1]. This shift, known as the Raman shift, provides a unique vibrational fingerprint for the substance under investigation.

The key advantage of this fingerprint is its specificity. Unlike techniques that merely detect the presence of a contaminant, Raman spectroscopy can identify its molecular structure by revealing specific chemical bonds and functional groups. For example, in the analysis of optical window contaminants, this allows researchers to distinguish between different types of deposits, such as rubidium silicate versus organic residues, based on their distinct spectral signatures [2] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Contaminant Identification Techniques

The following table compares Raman spectroscopy with other common analytical techniques used for contaminant identification, highlighting their respective advantages and limitations.

| Technique | Principle | Spatial Resolution | Detection Limit | Sample Preparation | Key Strengths | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic light scattering | Diffraction-limited (~0.5 µm) | ppm-ppb (enhanced with SERS) | Minimal, non-destructive | Provides molecular fingerprint; non-destructive; works in aqueous environments | Weak inherent signal; can be affected by fluorescence |

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Infrared absorption | Typically >10 µm | ~1% | Often requires compression or slicing | Fast; good for organic functional groups | Poor spatial resolution for micro-analysis; strong water interference |

| X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Photoemission from core electrons | ~10 µm | ~0.1-1 at% | Requires ultra-high vacuum | Quantitative; provides elemental and chemical state information | Destructive to surface; complex sample environment; no direct molecular ID |

| Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy-Dispersive X-ray (SEM/EDX) | Electron-induced X-ray emission | ~1 µm | ~0.1-1 wt% | Often requires conductive coating | Excellent topographical and elemental mapping | No direct molecular or chemical bond information |

| Traditional Microbiological Culture | Microbial growth | N/A | Single spore (but requires germination) | Extensive, sterile conditions | Gold standard for viability | Time-consuming (days); cannot identify non-viable spores [3] |

Advanced Raman Techniques for Enhanced Detection

To overcome the inherent challenge of Raman's weak signal, several advanced techniques have been developed, each suited for different scenarios.

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

SERS utilizes metallic nanostructures (typically gold or silver) to amplify the Raman signal by several orders of magnitude, enabling the detection of trace contaminants down to the single-molecule level [4] [5]. This is particularly valuable for identifying low-concentration impurities in sensitive environments like pharmaceutical production [6].

Time-Resolved Raman Spectroscopy

This technique separates the instantaneous Raman signal from longer-lived fluorescence, which often masks Raman spectra. By using a pulsed laser and a time-gated detector like a CMOS SPAD array, researchers can effectively suppress fluorescent backgrounds, a common issue when analyzing biological contaminants or certain materials [7].

Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS)

SORS collects Raman signals from a point spatially offset from the laser illumination spot. This allows for the probing of subsurface layers, making it possible to identify contaminants buried beneath a surface without destructive sampling [8].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for selecting the appropriate Raman technique based on the analytical challenge.

Experimental Protocols for Optical Contaminant Analysis

A robust protocol is essential for reliable contaminant identification. The following workflow, demonstrated in a study on a contaminated rubidium vapor cell, provides a generalizable framework [2].

Sample Preparation and Isolation

The first step involves isolating the contaminant for analysis. In the case of the rubidium cell, the inner surface of the optical window had developed an opaque black discoloration. The sample was carefully mounted to ensure the analysis point was accessible to both the laser and the collection optics without risking damage to the substrate [2].

Spectral Acquisition Parameters

- Laser Wavelength: A 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser is often preferred for organic or biological samples to minimize fluorescence. Shorter wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm or 532 nm) can be used for inorganic materials.

- Microscopy Coupling: The sample is placed under a microscope to precisely target the contaminated area. Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) microscopy can first be used to locate specific spores or particulate contaminants [3].

- Spectral Collection: Raman spectra are collected from multiple points on the contaminant to account for heterogeneity. Integration times are optimized to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio without causing thermal damage to the sample.

Data Processing and Analysis

- Preprocessing: Raw spectra undergo preprocessing to remove cosmic rays, correct for the instrument response, and subtract any fluorescent background using algorithms like asymmetric least squares (AsLS) [1].

- Spectral Interpretation: The processed spectrum is analyzed for characteristic Raman peaks. For instance, in the rubidium cell study, the unknown contaminant showed peaks that, when compared to known standards and simulations, were identified as rubidium silicate [2]. In another study, spores were identified by their characteristic peaks at 1577 cm⁻¹ (CaDPA), 1666 cm⁻¹ (amide I), and 2970 cm⁻¹ (C-H stretching) [3].

- Validation: Where possible, findings are validated against reference spectra from standard materials or through correlation with other analytical techniques.

The entire experimental journey, from sample preparation to identification, is summarized below.

Case Study: Raman Analysis in Action

A compelling example of this protocol in practice is the analysis of a contaminated optical window from a rubidium vapor cell used in laser-induced plasma experiments [2].

- The Problem: The optical window developed a matte black discoloration, leading to a loss of transparency. The composition of this layer was unknown, hindering both remediation and prevention efforts.

- The Analysis: Researchers collected Raman spectra directly from the discolored area. The resulting spectral fingerprints showed distinct peaks that did not match elemental rubidium or the quartz window material.

- The Identification: By comparing the unknown spectra with known reference spectra for rubidium compounds and supporting the findings with simulation results, the contaminant was conclusively identified as rubidium silicate. This finding pointed to a chemical reaction between the rubidium vapor and the quartz (SiO₂) window, likely initiated by the intense laser irradiation during the cell's operation [2].

- The Outcome: This molecular-level identification provided critical insight into the degradation mechanism, guiding the development of more durable cell designs and cleaning strategies, such as laser cleaning focused at the identified compound.

Characteristic Raman Peaks of Common Contaminants

The table below lists Raman shift ranges associated with key molecular bonds and functional groups found in various contaminants, providing a starting point for spectral assignment.

| Raman Shift (cm⁻¹) | Associated Bond/Vibration | Example Contaminants |

|---|---|---|

| 600–800 | Si-O-Si bending | Silicate glasses, quartz dust [2] |

| 838, 895, 1052 | Spore-specific biomarkers | Clostridium and Bacillus spores [3] |

| 1000–1100 | C-C and C-O stretching | Organic polymers, biofilms |

| 1400, 1577, 1666 | CaDPA, Amide I (Spores) | Bacillus cereus, B. thuringiensis [3] |

| 1722 | C=O stretching | Esters, organic acids, polyesters |

| 2970, 3000 | C-H stretching | Hydrocarbons, organic residues, spores [3] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful Raman spectroscopy lab requires more than just a spectrometer. The following table details key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Sol-gel SiO₂ Coating | Used to prepare standardized chemical coatings on optical substrates (e.g., fused silica) for contamination studies and laser damage threshold testing [9]. |

| Reference Materials (Polystyrene, CaF₂) | Provide a known Raman spectrum for instrument calibration, ensuring accurate wavenumber and intensity measurements across experiments [10]. |

| SERS Substrates (Gold/Silver Nanoparticles) | Engineered metallic nanostructures that dramatically enhance the Raman signal, enabling the detection of trace-level contaminants and single-molecule analysis [4] [5]. |

| CMOS SPAD Array Detector | A high-sensitivity, time-gated single-photon detector that allows for time-resolved Raman measurements, effectively suppressing fluorescent backgrounds [7]. |

| Python-based Analysis Platform | Enables automated batch processing, classification, and comparison of large Raman spectral datasets, reducing manual labor and improving identification efficiency [3]. |

The Future: AI and Miniaturization

The field of Raman spectroscopy is being transformed by two key developments. First, Artificial Intelligence (AI) and deep learning are now being used to automatically process complex spectral data, identify subtle patterns, and classify contaminants with high speed and accuracy, overcoming traditional challenges like background noise and fluorescence [1] [6] [8]. Second, a strong push for miniaturization is making high-performance Raman instrumentation more compact, affordable, and accessible. Recent advances have led to centimeter-scale spectrometers that are suitable for integration into handheld devices, production lines, and medical tools, thereby democratizing this powerful technology for field use [10].

The performance and longevity of optical systems are critically dependent on the pristine condition of their optical surfaces. Contamination, the unwanted accumulation of materials on these surfaces, is a pervasive challenge that can lead to significant degradation of optical performance, including reduced transmission, increased scattering, laser-induced damage, and wavefront distortion. The genesis of contaminants is multifaceted, arising from external environmental exposure, internal outgassing of system components, and even the manufacturing process itself. This guide provides a systematic comparison of common contaminants, the advanced analytical techniques used to characterize them, and the effective protocols for their mitigation, framed within the context of Raman spectroscopy analysis for optical window contaminants research.

A Comparative Analysis of Common Optical Contaminants

Optical contaminants can be broadly categorized by their origin, chemical composition, and resulting impact on system functionality. Their effects range from subtle alterations in the refractive index to complete functional failure.

Table 1: Comparison of Common Contaminants in Optical Systems

| Contaminant Type | Primary Origin | Chemical Composition | Impact on Optical Performance | Detection Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicates | Laser-induced reaction with substrate [2], Polishing residues [11] | Rubidium silicate, Aluminum silicate [2] [11] | Forms opaque, absorbing layers; drastically reduces transmission [2] | Raman spectroscopy, XPS [2] [11] |

| Polishing Residues | Chemical-Mechanical Polishing (CMP) [11] | Aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃), Cerium Oxide (CeO₂), Silicon Carbide (SiC) [11] | Embedded particles act as scattering centers and absorption sites, lowering LIDT [11] | XPS, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) [12] |

| Synthetic Polymers | Outgassing from seals, adhesives, and composites [13] | Silicones, acrylics, polycarbonates [13] | Molecular films cause haze, transmission loss, and altered color balance [13] | Ellipsometry, Haze measurement [13] |

| Particulate Matter | Environmental fallout, wear debris, laser-induced damage [2] | Dust, metals, organics | Light scattering, wavefront distortion, can initiate laser-induced damage | Optical microscopy, light scattering |

| Water Contaminants (as deposits) | Exposure to contaminated environments [14] [15] | Phosphates, Nitrates, Pharmaceuticals, Pesticides [15] | Surface films that scatter/absorb light; can promote mold or fungal growth [14] | SERS, Raman spectroscopy [14] [15] |

The mechanisms of contamination vary significantly. Silicates, such as the rubidium silicate identified on the inner surface of a rubidium vapor cell, are often the product of a laser-induced reaction where the optical substrate itself (e.g., quartz) interacts with environmental vapors, forming an opaque layer that severely compromises transparency [2]. Conversely, polishing residues like aluminum and sodium are manufacturing-induced contaminants. Their surface concentration has been shown to increase with the concentration and pH of the polishing suspension, and they can penetrate the near-surface layer of the glass, becoming encapsulated in a so-called "Beilby layer" [11]. Synthetic polymers from outgassing are a critical concern in enclosed systems, such as space exploration modules, where molecular contamination from silicone seals and O-rings can condense on critical optical surfaces like window assemblies, leading to haze and transmission loss [13].

Analytical Techniques for Contaminant Identification and Quantification

Accurate identification and quantification are prerequisites for effective contamination control. Raman spectroscopy and Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) are two powerful, complementary techniques for this purpose.

Raman and Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS)

Raman spectroscopy excels in providing a molecular "fingerprint" of contaminants, allowing for precise chemical identification without extensive sample preparation [15]. The choice of laser wavelength is a critical experimental parameter, balancing signal intensity, fluorescence suppression, and sample damage. Longer wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm) reduce fluorescence but require higher power due to the inherent 1/λ⁴ decrease in Raman scattering intensity [16].

For trace analysis, Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) provides orders-of-magnitude signal enhancement by adsorbing target molecules onto nanostructured noble metal surfaces or mixing them with metal nanoparticles [14] [15]. This makes it ideal for detecting low-concentration analytes like pharmaceutical residues or perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in water, with detection limits reaching parts per billion (ppb) [14]. Pre-concentration methods, such as leveraging the "coffee-ring effect" where a drying droplet concentrates analytes at its edge, further enhance sensitivity for detecting pollutants like nitrates, phosphates, and pesticides [15].

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS)

LIBS is a versatile, rapid technique for elemental analysis that requires little to no sample preparation. It is particularly effective for depth-resolved analysis of contaminants. A calibration-free LIBS approach has been successfully used to quantify manufacturing-induced trace contaminants (e.g., aluminum, calcium) on optical glass surfaces, revealing their penetration depth and correlation with changes in the optical properties of the glass [12]. LIBS can also be used as a real-time monitoring tool during laser cleaning processes [2].

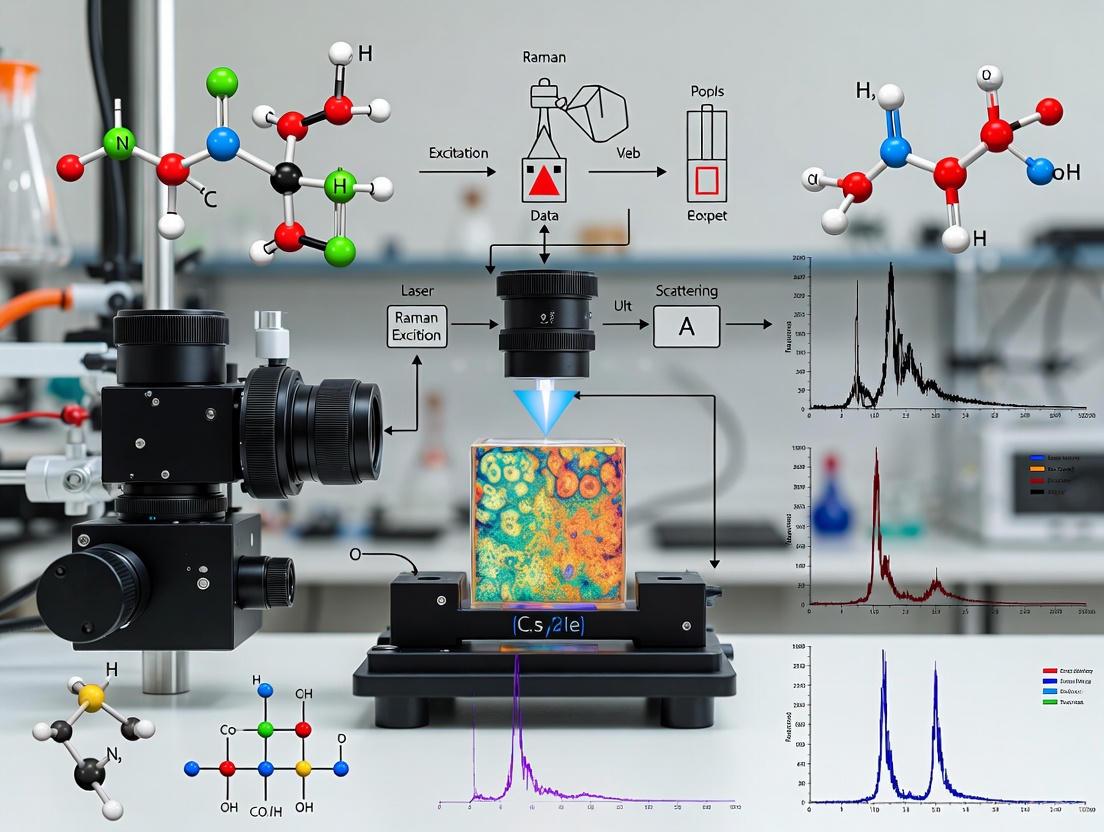

Figure 1: A workflow for analyzing optical contaminants using complementary spectroscopic techniques. Raman provides molecular identification, SERS enhances sensitivity for trace analysis, and LIBS delivers elemental composition and depth profiling.

Experimental Protocols for Contamination Study and Mitigation

Protocol 1: Raman Analysis of Surface Contaminants

This protocol is adapted from studies on detecting water contaminants and vapor cell deposits [2] [15].

- Apparatus: A Raman spectrometer (e.g., i-Raman with 785 nm diode laser), microscope objectives (e.g., 40X, NA 0.5), an aluminum foil-covered microscope slide.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation (Coffee-Ring Effect): Deposit a 2-5 µL droplet of the liquid sample (or a suspension of a solid contaminant) onto the Al substrate. Allow it to dry at room temperature for 15-20 minutes. The analyte will concentrate at the edge of the droplet.

- Instrument Calibration: Acquire a background spectrum with the laser off. Perform a spectral calibration using a standard like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE).

- Spectral Acquisition: Focus the laser on the edge ("coffee-ring") of the dried deposit. Acquire spectra using a laser power of a few mW to 300 mW (dependent on the sample's Raman cross-section). Average 3 acquisitions to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Analysis: Compare the obtained spectra against reference spectral libraries to identify the contaminant's molecular structure. For SERS, perform the same procedure using a nanostructured SERS substrate or by adding gold nanoparticles to the sample solution before deposition [15].

Protocol 2: Laser Cleaning of Optical Components

This protocol is based on the successful cleaning of a rubidium vapor cell's internal optical window [2].

- Apparatus: A Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm, 3.2 ns pulse width), a converging lens (e.g., f=295 mm).

- Procedure:

- Parameter Setup: Operate the laser in single-pulse mode to minimize thermal stress. Set the pulse energy cautiously, starting from low values (e.g., 50 mJ) and increasing as needed (up to 360 mJ in the referenced study).

- Beam Focusing: Focus the laser beam inside the cell, approximately 1 mm in front of the contaminated surface. This defocusing strategy minimizes heat stress on the glass substrate and prevents the formation of micro-cracks.

- Cleaning Execution: Apply a single laser pulse to the target area. The pulse is typically sufficient to clear the discoloration and restore transparency locally.

- Process Control: Monitor the cleaning efficiency visually or via microscopy. Raman spectroscopy or LIBS can be used in situ to verify the removal of the contaminant and ensure no damage to the substrate [2].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Contaminant Analysis and Mitigation

| Research Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nanostructured SERS Substrates (Au/Ag NPs on SiO₂) [14] | Signal enhancement for ultrasensitive detection of trace contaminants. | 3D nanohybrid substrates provide greater active surface area and higher sensitivity [14]. |

| Aluminum Oxide (Al₂O₃) Polishing Suspension [11] | Simulating and studying manufacturing-induced contamination. | Concentration and pH of the suspension directly influence the level of Al and Na surface contamination [11]. |

| Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser (1064 nm) [2] | Laser cleaning of robust contaminants like rubidium silicate. | Defocusing the beam (1 mm before surface) is critical to avoid glass damage [2]. |

| Isopropanol & Cleanroom Wipes | Standard cleaning and decontamination of optical surfaces. | Effective for removing loose particulate and some molecular films; efficiency should be validated post-cleaning [13]. |

The battle against optical contamination requires a systematic approach grounded in a deep understanding of contaminant origins, precise analytical identification, and effective mitigation strategies. Silicates and polishing residues represent chemically complex, tenacious contaminants often requiring advanced removal techniques like laser cleaning. In contrast, synthetic polymers from outgassing pose a persistent threat in sensitive enclosed systems. The researcher's arsenal, featuring techniques like Raman spectroscopy, SERS, and LIBS, provides the necessary tools for definitive contaminant characterization. As optical systems continue to advance, pushing the limits of power and precision, the protocols for maintaining contaminant-free surfaces will remain a cornerstone of optical engineering and research.

In optical systems, particularly those containing reactive alkali vapors, the formation of contaminant layers on optical windows presents a significant challenge to long-term operational stability and data integrity. This case study examines a specific instance of this phenomenon: the analysis of a black, opaque contaminant layer formed on the inner window of a rubidium vapor cell. Such cells are critical components in numerous advanced applications, including atomic clocks, optical magnetometers, and research on laser wake field acceleration, where optical transparency is paramount [2]. The gradual development of this layer during normal cell operation led to a substantial loss of window transparency, necessitating both its removal and identification. This study details the application of Raman spectroscopy as the principal analytical technique for identifying the chemical composition of the contaminant, coupled with laser cleaning as a method for its removal. The findings are contextualized within broader research on optical window contaminants, highlighting the efficacy of Raman spectroscopy for non-destructive molecular fingerprinting in challenging diagnostic scenarios.

Experimental Setup and Methodology

Sample Description and Contamination Challenge

The subject of analysis was a worn Rubidium vapor cell from a laser-induced plasma generation experiment. The cell was a cylindrical glass tube with optical quality quartz end windows. The primary issue was the development of an opaque, amorphous black discoloration with a grey halo on the inner surface of the exit window, which severely compromised its transparency. In contrast to metallic rubidium deposits also present on the window, this black layer was persistent under normal operating conditions and was therefore the main target for analysis and removal [2].

Laser Cleaning Protocol

Prior to Raman analysis, a laser cleaning procedure was employed to remove the contaminant layer. The cleaning was performed using a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser operating at its fundamental wavelength of 1064 nm, with a pulse width of 3.2 ns [2].

- Laser Parameters: Pulse energy was varied cautiously from 50 to 360 mJ. The laser was operated in single-pulse mode to minimize thermal stress on the quartz substrate.

- Beam Delivery: The laser beam was passed through the intact entrance window of the cell and focused by a biconvex lens (295 mm focal length) to a point approximately 1 mm in front of the contaminated inner surface. This defocusing strategy was critical to avoid damaging the quartz window itself.

- Cleaning Efficacy: A single laser pulse was sufficient to clear the black discoloration at the focal spot, locally restoring the window's transparency. The calculated fluence at the contamination layer ranged from 400 J/cm² to 3 kJ/cm², depending on the pulse energy [2].

Raman Spectroscopy Analysis

Raman spectroscopy was utilized to determine the molecular composition of the opaque black contaminant. The methodology focused on obtaining the vibrational fingerprint of the material.

- Spectral Acquisition: Raman spectra were acquired directly from the contaminated spots on the inner window before the cleaning procedure.

- Spectral Interpretation: The obtained spectra were compared with known reference spectra from databases and the scientific literature. A specific comparison was made with spectra of rubidium germanate compounds and simulated spectra.

- Identification Strategy: The identity of the contaminant was deduced based on the positions and shapes of the Raman peaks, which served as a unique molecular fingerprint [2].

Results and Data Analysis

Identification of the Contaminant

The Raman spectral analysis proved decisive in identifying the contaminant. The spectra obtained from the black layer showed distinct peaks that did not match any previously documented rubidium compounds in the literature. However, through comparison with known materials and theoretical simulations, the evidence strongly indicated that the unknown contaminant was rubidium silicate [2]. This finding supports the plausible hypothesis that during the cell's operation in plasma generation experiments, intense laser pulses ablated the quartz (SiO₂) window material. The liberated silicon and oxygen subsequently interacted with the rubidium vapor to form a silicate compound on the inner window surface.

Raman Peak Assignments

The following table summarizes the key Raman spectral features that contributed to the identification of the contaminant as rubidium silicate.

Table 1: Key analytical data from the Raman analysis of the window contaminant.

| Analysis Parameter | Finding | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Contaminant Identity | Rubidium Silicate | Strongly suggested by comparison with known germanate spectra and simulations [2]. |

| Raman Peaks | Distinct, previously undocumented peaks | Indicated a unique molecular structure not commonly reported [2]. |

| Laser Cleaning Result | Successful transparency restoration with a single pulse (1064 nm, 3.2 ns pulse) | Demonstrated effective, localized contaminant removal without substrate damage [2]. |

Discussion: Raman Spectroscopy in the Analysis of Optical Contaminants

Technique Advantages and Broader Context

The successful identification of rubidium silicate in this case study underscores the power of Raman spectroscopy for analyzing optical contaminants. Its key advantages in this context include:

- Molecular Specificity: Unlike elemental analysis techniques, Raman spectroscopy provides information about chemical bonds and molecular structure, allowing for direct identification of compounds like rubidium silicate [2].

- Non-Destructive Nature: The analysis can be performed in situ without the need to remove or extensively alter the sample, preserving the integrity of the valuable vapor cell for further study [2].

- Complementarity with Other Techniques: As demonstrated in studies on lithiated glasses, Raman spectroscopy is highly effective when used in tandem with elemental analysis techniques like Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), which can quantify elemental composition (e.g., lithium content) while Raman characterizes the bonding environment [17].

Critical Considerations for Reliable Raman Analysis

To ensure the reliability of Raman spectroscopy for sensitive applications like contaminant analysis, several factors must be addressed:

- Instrument Stability: Long-term device drift can introduce substantial spectral variations, reducing the reliability of data and machine learning models. A systematic approach to benchmarking stability using control substances is essential for quantitative work [18].

- Fluorescence Interference: Many samples, especially biological or complex contaminants, can produce strong fluorescence that overwhelms the weaker Raman signal. Time-resolved techniques using pulsed lasers and gated detectors, such as CMOS Single-Photon Avalanche Diode (SPAD) arrays, can effectively separate the instantaneous Raman scattering from longer-lived fluorescence [7].

- Miniaturization and Calibration: Emerging miniaturization strategies for Raman spectrometers aim to make the technology more accessible. A key development is the use of an internal reference channel (e.g., polystyrene) for real-time calibration of wavenumber and intensity, ensuring data consistency and accuracy in compact systems [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, materials, and instruments used in the featured experiment and related analytical workflows in this field.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for Raman analysis and related studies.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Rubidium Vapor Cell | Sample environment for generating contaminants and testing cleaning. | Cylindrical glass tube with quartz optical windows [2]. |

| Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser | Laser cleaning and potential excitation source for Raman. | 1064 nm, 3.2 ns pulse width, used for contaminant ablation [2]. |

| Raman Spectrometer | Molecular fingerprinting of contaminants and materials. | Can be equipped with a 785 nm laser and a cooled CCD detector [19]. |

| Reference Materials (Polystyrene, Cyclohexane) | Wavenumber and intensity calibration of the Raman spectrometer. | Critical for ensuring data accuracy and cross-instrument comparability [18] [10]. |

| Lithium Carbonate (Li₂CO₃) | Model system for studying alkali-silicate glass formation and analysis. | Added to silica glass to create standards for LIBS/Raman correlation studies [17]. |

| Time-Gated SPAD Detector | Fluorescence suppression in Raman spectroscopy. | Enables time-resolved detection to separate Raman signal from fluorescent background [7]. |

Visual Workflows

To clarify the experimental and analytical processes described, the following diagrams outline the key workflows.

Experimental Workflow for Contaminant Analysis and Removal

Data Processing Pipeline for Raman Spectral Stability

This case study demonstrates a successful integrated approach to diagnosing and remediating a complex optical contamination problem. The application of Raman spectroscopy was crucial for identifying the black contaminant as rubidium silicate, a finding that provides insight into the chemical interactions within operational vapor cells. The complementary use of laser cleaning with a carefully defocused beam effectively restored optical transparency without damaging the underlying quartz substrate. For researchers and drug development professionals, this work highlights the importance of robust, well-calibrated spectroscopic techniques. The methodologies presented—from fundamental spectral acquisition to advanced data processing for ensuring long-term instrument stability—provide a framework for tackling similar analytical challenges in the fields of optical engineering, material science, and pharmaceutical development where unwanted surface layers can compromise system performance and product quality.

The Critical Impact of Window Contamination on Optical Performance and Experiment Integrity

In photonics and analytical chemistry research, the integrity of optical windows is a fundamental prerequisite for data accuracy and experimental validity. Optical window contamination—the accumulation of foreign materials on optical surfaces—comprises a critical yet frequently overlooked variable that can systematically compromise experimental outcomes. These contaminants, ranging from sub-micron particulates to chemically reacted films, introduce significant measurement error, reduce laser-induced damage thresholds (LIDT), and ultimately jeopardize the reproducibility of scientific findings.

The context of Raman spectroscopy analysis presents a particularly compelling case study. As a technique reliant on the detection of weak inelastic scattering signals, Raman spectroscopy is exceptionally vulnerable to the confounding effects of window contamination, which can manifest as increased fluorescence background, spectral interference, or complete signal attenuation. This analysis examines the critical impact of contamination through comparative experimental data, delineates methodological frameworks for contamination identification and remediation, and provides standardized protocols for maintaining optical integrity across research applications.

Optical window contamination originates from diverse sources, each imparting distinct detrimental effects on optical performance and experimental data quality.

Manufacturing-Induced Contaminants

Residual polishing compounds and processing materials can become embedded into optical surfaces during manufacturing. Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) depth-profile analysis reveals that manufacturing-induced trace contaminants penetrate subsurface layers, directly correlating with localized changes in the index of refraction and creating sites for preferential laser damage [12]. These subsurface defects act as nucleation points for further contamination accumulation and significantly reduce the LIDT of optical components, a critical parameter for high-power laser applications [20].

Operational Deposits in Harsh Environments

In operational contexts, optical windows undergo complex interactions with their environment. Research using rubidium vapor cells demonstrates that internal window deposits form amorphous, opaque layers that progressively reduce transmission. Raman spectral analysis identified these deposits as rubidium silicate, a reaction product between the quartz window and rubidium vapor under laser irradiation [2]. Similarly, high-temperature optical cells for vapor analysis face persistent issues with material condensation and buildup on windows, which necessitates innovative design solutions like cover gas buffers to preserve optical access [21].

Particulate Contamination in Pharmaceutical Settings

The pharmaceutical industry documents that particulate matter on optical windows used for quality control can lead to false positive/negative results in contaminant identification. Cellulose fibers, synthetic polymers (e.g., PET, polypropylene), and glass fragments from packaging systems adhere to optical surfaces, scattering incident light and generating spurious Raman signals that interfere with accurate pharmaceutical analysis [22].

Table 1: Classification of Common Optical Window Contaminants and Their Primary Effects

| Contaminant Type | Primary Source | Impact on Optical Performance | Analytical Technique for Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polishing residues (ceria, alumina) | Manufacturing process | Subsurface damage; Reduced LIDT; Refractive index modification | LIBS depth profiling [12] |

| Metallic silicates | High-temperature vapor cells | Transmission loss; Increased scattering; Permanent window opacity | Raman spectroscopy [2] |

| Synthetic polymers (PET, PP, PTFE) | Pharmaceutical processing equipment | Fluorescence background; Characteristic Raman interference peaks | Raman microspectroscopy [22] |

| Cellulose fibers & dyes | Packaging materials | Broad spectral interference; Particulate scattering | Optical microscopy + Raman [22] |

| Metallic nanoparticles | SERS substrate migration | Plasmonic effects; Signal enhancement/interference | SEM-EDS analysis [23] |

Comparative Analysis: Quantifying the Impact of Contamination

Transmission Loss and Signal Degradation

The most direct impact of window contamination is the reduction of light transmission. In rubidium vapor cells, contaminated windows developed opaque layers that rendered the cell unusable for plasma generation experiments due to insufficient transmission of the incident laser beam [2]. For Raman spectroscopy specifically, contamination-induced fluorescence background can overwhelm the weak Raman signal, necessitating advanced algorithmic correction (e.g., airPLS) to restore spectral fidelity [24].

Laser-Induced Damage Threshold Reduction

Contamination significantly compromises the resilience of optical components to high-power laser irradiation. Laser-Induced Damage in Optical Materials 2025 conference proceedings emphasize that optical surfaces often limit the power handling capability of an optic due to intrinsic and extrinsic flaws and defects [20]. Contamination particles create localized absorption centers where thermal energy concentrates, initiating damage at fluences far below the intrinsic threshold of the pristine optical material.

Analytical Interference in Spectral Measurements

Contamination interferes with analytical measurements through multiple mechanisms. Pharmaceutical research documents that particulate contamination on inspection windows leads to misidentification of drug components, potentially causing product quality failures [22]. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) studies further show that migratory metal nanoparticles from substrates can create unpredictable enhancement zones, compromising quantitative analysis [23].

Table 2: Experimental Data on Contamination Effects Across Applications

| Application Context | Measured Parameter | Clean Window Performance | Contaminated Window Performance | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rubidium vapor cell [2] | Transmission at 800 nm | >95% (new cell) | <10% (heavily contaminated) | Laser transmission measurement |

| High-power laser optics [20] | Laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) | Material-dependent intrinsic value | Up to 80% reduction at contamination sites | ISO-standard LIDT testing |

| Pharmaceutical Raman [22] | Signal-to-noise ratio | >100:1 | <5:1 (with fluorescence interference) | Raman spectral acquisition |

| SERS substrates [23] | Enhancement factor variance | <15% across substrate | >300% across substrate | Rhodamine B mapping at 1358 cm⁻¹ peak |

Methodologies for Contamination Analysis and Remediation

Contamination Identification Techniques

Raman Spectroscopy for Chemical Identification

Raman spectroscopy serves as a powerful tool for non-destructive chemical identification of contaminants. Through acquisition of unique molecular fingerprint spectra, researchers can precisely identify contaminant materials without sample destruction [22]. The technique is particularly valuable for distinguishing between chemically similar contaminants, such as differentiating polyethylene terephthalate (PET) from polybutylene terephthalate (PBT) based on characteristic peak shifts in the C=O stretching region (1716 cm⁻¹ vs. 1727 cm⁻¹) [22].

Advanced Raman methodologies incorporate density functional theory (DFT) simulations to validate experimental spectra against theoretical predictions, thereby confirming contaminant identity with high confidence [24]. For complex contamination scenarios involving multiple materials, Raman microspectroscopy can resolve individual components within heterogeneous mixtures, as demonstrated in the identification of silicone-lubricated PTFE particles in pharmaceutical products [22].

Complementary Analytical Techniques

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) provides elemental composition data that complements the molecular information from Raman. LIBS is particularly effective for identifying glass contaminants and determining their origin through elemental fingerprinting [22]. The technique can be implemented sequentially with Raman on the same instrument platform, enabling comprehensive contamination characterization [22].

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) reveals the morphological characteristics of contaminants at nanometer resolution. SEM analysis of SERS substrates has shown that contaminants often accumulate at high-enhancement sites with fractal geometries and small interstructural distances [23]. This morphological information is crucial for understanding contamination mechanisms and developing effective prevention strategies.

Contamination Remediation Approaches

Laser Cleaning Techniques

Laser cleaning represents a precision removal approach for optical window contaminants. The process utilizes carefully controlled laser parameters (wavelength, pulse duration, fluence) to selectively ablate contaminant layers while preserving the underlying substrate [2]. Successful laser cleaning of a rubidium vapor cell window was demonstrated using a frequency-doubled Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm, 3.2 ns pulses) focused 1 mm inside the contaminated surface, achieving localized transparency restoration with single-pulse application [2].

The efficacy of laser cleaning hinges on the differential absorption between the contaminant and substrate material. Proper parameter selection ensures complete contaminant removal while maintaining the optical surface integrity, preventing micro-crack formation that could compromise mechanical stability or serve as nucleation sites for future contamination [2].

Preventive Design Strategies

Prevention represents the most effective contamination management strategy. High-temperature optical cells employ cover gas buffer systems to prevent material condensation on optical windows during extended operation [21]. Modular cell designs further facilitate maintenance and cleaning while allowing optical path length optimization for different spectroscopic techniques [21].

Diagram 1: Systematic workflow for optical window contamination management, integrating detection, impact assessment, and remediation strategies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Analysis and Prevention

| Reagent/Material | Application Context | Specific Function | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold-coated filters [22] | Pharmaceutical particulate analysis | Low-background substrate for Raman analysis of contaminants | Minimizes fluorescence interference; enables direct particle analysis |

| Cyclohexane standard [18] | Raman instrument calibration | Wavenumber calibration reference for spectral accuracy | Provides well-defined Raman bands at 802, 1028, 1266, 1444, 2664 cm⁻¹ |

| Silicon wafer standard [18] | Raman intensity calibration | Exposure time calibration using 520 cm⁻¹ band | Ensures consistent intensity measurements across time |

| Paracetamol reference [18] | Multi-component calibration | Validates spectral performance across wavelength ranges | Complex spectrum tests instrument resolution and sensitivity |

| Rhodamine B solutions [23] | SERS substrate characterization | Analytic for quantifying enhancement factors and uniformity | Concentrations from 10⁻² M to 10⁻¹² M assess substrate sensitivity |

| SbCl₅ vapor [21] | High-temperature cell validation | Test analyte for UV-vis/LIBS integration in vapor phase | Challenges system at operational temperatures up to 450°C |

The systematic investigation of optical window contamination reveals a multifaceted challenge with direct consequences for experimental integrity across scientific disciplines. Contamination-induced effects—including transmission loss, laser damage threshold reduction, and spectral interference—represent significant yet preventable sources of experimental error. The methodologies outlined herein provide researchers with a structured framework for contamination identification, impact assessment, and remediation.

The integration of Raman spectroscopy with complementary techniques like LIBS and SEM enables comprehensive contaminant characterization, while advanced laser cleaning approaches offer targeted removal solutions. Most critically, preventive design strategies and routine monitoring protocols represent the most effective approach to maintaining optical performance over time. As optical technologies continue to advance in sensitivity and application complexity, vigilant contamination management will remain an essential component of rigorous scientific practice.

From Detection to Action: Methodologies for Contaminant Analysis and Removal

Laser cleaning has emerged as a advanced, non-contact technique for removing contaminants from optical windows, proving particularly valuable in research applications where precision and non-invasiveness are paramount. This method utilizes controlled laser energy to ablate unwanted surface layers—such as rubidium silicate deposits, hydrocarbons, and particulate matter—without damaging the underlying optical substrate. When integrated with Raman spectroscopy, laser cleaning enables researchers to both remove contaminants and analyze their chemical composition in situ, providing a powerful combined approach for maintaining optical performance in sensitive experimental systems. This guide objectively compares laser cleaning against traditional methods, supported by experimental data and protocols demonstrating its efficacy for scientific applications.

In scientific research, the transparency and quality of optical windows are paramount. Contamination—whether from environmental exposure, operational byproducts, or handling—can significantly degrade optical performance by reducing transmission, creating wavefront distortions, and introducing localized absorption that lowers the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) [25] [26]. In the specific context of Raman spectroscopy, contaminated optics can yield poor-quality spectra with elevated background noise, compromising analytical results.

Traditional cleaning methods often fall short for research-grade optics. Mechanical wiping risks surface scratching, while chemical solvents may leave residues or interact with sensitive coating materials [26] [27]. Laser cleaning addresses these limitations by providing a controlled, non-contact process that can be finely tuned to remove specific contaminants while preserving the optical substrate, making it particularly suitable for the meticulous demands of drug development and analytical research.

Comparative Analysis of Optical Cleaning Methods

Various techniques are employed for cleaning optical surfaces, each with distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. The table below provides a structured comparison of these methods.

Table 1: Comparison of Optical Surface Cleaning Methods

| Cleaning Method | Mechanism of Action | Best For Contaminants | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Cleaning [2] [28] [29] | Ablation via high-energy pulsed light | Oxides, rust, paints, coatings, thin films, rubidium silicate [2] | Non-contact, high precision, no chemicals, automatable | High initial investment, risk of thermal damage if misused |

| Solvent Cleaning [28] [27] | Chemical dissolution | Oils, greases, adhesives, organic residues | Effective on organic films, fast evaporation | Chemical hazards, potential for residue, may damage coatings |

| Mechanical Cleaning [28] [30] | Abrasion or wiping | Loose particles, some thick coatings | Fast, low cost for large surfaces | High risk of scratching, generates dust, low precision |

| Plasma Cleaning [28] [30] | Energetic ionized gas bombardment | Oils, thin organic films, dust | Non-contact, eco-friendly, good for complex geometries | Less control, can generate residues, not for all metals |

| Microbial Cleaning [28] | Microbial digestion of hydrocarbons | Oils and greases | Eco-friendly, safe process | Slow, limited to specific organic contaminants |

Laser Cleaning in Research: Principles and Protocols

Laser cleaning operates on the principle of selective photothermal ablation. Short, high-energy laser pulses are absorbed by the contaminant layer, causing rapid heating and vaporization. The underlying substrate remains undamaged provided the laser parameters are tuned so that the contaminant's ablation threshold is exceeded while the substrate's damage threshold is not [2] [31].

Experimental Protocol: Laser Cleaning and Raman Analysis of a Contaminated Vapor Cell

A study exemplifies the integration of laser cleaning with Raman analysis. Researchers successfully restored the transparency of a rubidium vapor cell's optical window, which had developed an opaque inner layer of contamination during operation [2].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Frequency-doubled Nd:YAG Laser | Provides the 532 nm wavelength for Raman excitation and analysis of the contaminant. |

| Q-switched Nd:YAG Laser | Provides nanosecond pulses at 1064 nm for the cleaning procedure. |

| Biconvex Focusing Lens | Focuses the cleaning laser beam precisely inside the vapor cell. |

| Raman Spectrometer | Analyzes the molecular composition of the contaminant before and after cleaning. |

| Optical Microscope | Inspects the optical window surface for damage and assesses cleaning efficacy. |

Methodology:

- Contaminant Analysis: The unknown black contaminant on the inner window was first analyzed using Raman spectroscopy. The resulting spectra, showing peaks not previously described in literature, were compared with known standards and simulations, strongly suggesting the material was rubidium silicate [2].

- Laser Cleaning Setup: A Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm, 3.2 ns pulse width) was used for cleaning. The beam was passed through the uncontaminated entrance window and focused by a 295 mm focal length biconvex lens to a point approximately 1 mm in front of the contaminated inner surface. This defocusing strategy was critical to minimize heat stress on the glass and prevent micro-crack formation [2].

- Cleaning Execution: The laser was operated in single-pulse mode. A single pulse with an energy of 50 mJ, yielding a calculated fluence of approximately 400 J/cm², was sufficient to clear the black discoloration at the focal spot and locally restore window transparency. The process was repeated across the contaminated area [2].

- Post-Cleaning Validation: The cleaned spots were inspected to confirm the removal of the contaminant and the absence of damage to the quartz window. The success of this single-pulse intervention demonstrated the potential of laser cleaning for in-situ remediation of sensitive optical components without disassembly [2].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process of Raman analysis followed by laser cleaning.

Technical Specifications and Performance Data

The effectiveness of laser cleaning is governed by key parameters including wavelength, pulse duration, fluence, and power. Selecting the correct configuration is essential for achieving optimal cleaning without substrate damage.

Laser Power and Performance Comparison

Laser cleaners are categorized by power and operation mode, which dictate their suitability for different tasks.

Table 3: Laser Cleaning System Specifications and Performance

| Laser Type | Power Range | Typical Applications | Cleaning Speed (Est.) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-Power Pulsed [32] [29] | 20 W - 100 W | Delicate optics, removal of thin films, precision components | 20-30 cm²/s | High precision, minimal thermal load, suitable for lab environments |

| Medium-Power Pulsed [32] [29] | 100 W - 500 W | Industrial mold cleaning, rust, paint, and oxide removal | Can exceed 100 cm²/s | Balances speed and precision, versatile for R&D and maintenance |

| High-Power Continuous Wave (CW) [29] | 500 W - 1000 W+ | Large-scale rust and coating removal on structural parts | Very high speed | High thermal influence, generally not suitable for sensitive optics |

| Pulsed Fiber Laser [2] [29] | 50 mJ/pulse (e.g.) | Research-grade optic cleaning (as in protocol) | Spot-by-spot | Enables fine control of fluence, ideal for non-destructive ablation |

The Role of Laser Wavelength and Fluence

- Wavelength: The laser wavelength must be strongly absorbed by the contaminant and, ideally, transmitted or reflected by the substrate. For glass optics, UV and IR wavelengths are often effective [33]. The study on stained glass used a 248 nm excimer laser, while the vapor cell cleaning employed a 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser, demonstrating wavelength selection is context-dependent [2] [33].

- Fluence: This is the most critical parameter. The process must operate between the contaminant's ablation threshold and the substrate's damage threshold. For the rubidium vapor cell, a fluence of 400 J/cm² was successful [2]. Research on stained glass found that the ablation thresholds for crusts (0.25–2.0 J/cm²) were dangerously close to the alteration thresholds of the historical glass itself, requiring extremely careful control [33].

The decision-making process for implementing laser cleaning on an optical component can be summarized as follows.

Implementation in a Research Setting

Integrating laser cleaning into a scientific workflow, particularly one involving Raman spectroscopy, requires careful planning.

- Pre-Cleaning Analysis: Always first analyze the contaminant using Raman spectroscopy or other techniques (e.g., LIBS) to identify its composition. This informs the selection of appropriate laser parameters [2] [31].

- Parameter Calibration: Begin with laser energies well below the predicted damage threshold of the substrate. Use test samples or a small, inconspicuous area to establish safe and effective parameters. Continuously monitor the process with visual or acoustic sensors to detect early signs of damage [31].

- Post-Cleaning Validation: After cleaning, repeat Raman analysis to confirm contaminant removal and the absence of chemical alterations to the substrate. Perform microscopic inspection to rule out surface damage like micro-cracks or melting [2] [27].

For routine maintenance of less critical optics, traditional methods may suffice. However, for high-value research where optical integrity is non-negotiable—such as in the windows of vapor cells for atomic physics or the lenses of high-power laser systems—the precision and control of laser cleaning make it a superior choice, despite a higher initial investment [25] [2] [26].

Leveraging Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) for Ultra-Sensitive Trace Detection

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) has emerged as a transformative analytical technique for detecting trace-level contaminants, offering unparalleled sensitivity and molecular specificity. This capability is particularly vital for analyzing optical window contaminants, where even minute residues can compromise performance in spectroscopic systems and sensor applications. SERS overcomes the inherent weakness of conventional Raman scattering by leveraging nanostructured metallic surfaces to enhance signals by factors up to 1011, enabling single-molecule detection in some applications [34] [35]. The technique provides distinctive "molecular fingerprint" identification, allowing for the precise characterization of contaminant compounds without complex sample preparation [36] [35].

This guide objectively compares the performance of various SERS substrates and detection strategies, focusing on their applicability to contaminant analysis. We present experimental data, detailed methodologies, and practical toolkits to assist researchers in selecting appropriate SERS platforms for their specific trace detection requirements in optical research and drug development contexts.

Performance Comparison of SERS Platforms

The analytical performance of SERS-based detection varies significantly across different substrate designs and enhancement strategies. The following tables summarize key performance metrics for various SERS platforms as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Comparison of SERS Substrate Performance for Trace Contaminant Detection

| Substrate Material | Analytical Performance | Analyte | Detection Limit | Enhancement Factor (EF) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver-coated eggshell membrane (ESM/20Ag) | Label-free detection | 4-MBA | Not specified | 0.12 × 106 | [37] |

| Silver-coated eggshell membrane (ESM/20Ag) | Label-free detection | 4-MPBA | Not specified | 0.70 × 105 | [37] |

| Silver-coated eggshell membrane (ESM/20Ag) | Label-free detection | R6G | Not specified | 0.36 × 104 | [37] |

| Unfunctionalized SERS substrates | Label-free detection in complex matrices | Tabun (in contact lens liquid) | 7-9 ppm | Not specified | [38] |

| Unfunctionalized SERS substrates | Label-free detection in complex matrices | Tabun (in eye serum) | 10.2 ppm | Not specified | [38] |

| Unfunctionalized SERS substrates | Label-free detection in complex matrices | VX (in contact lens liquid) | 0.6-5 ppm | Not specified | [38] |

| Cellulose-based substrates | Functionalized with metal nanoparticles | Various analytes | Down to single molecule | Up to 1011 | [34] |

Table 2: Comparison of SERS Detection Strategies

| Detection Strategy | Mechanism | Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Label-free detection | Direct enhancement of target molecule signals | Pesticides (thiram, thiabendazole), nerve agents [36] [38] | Simple substrate preparation, direct molecular identification | Limited to molecules with strong SERS response [36] |

| Labeled detection (SERS encoding) | Uses Raman reporter molecules with distinct spectral signatures | Multiple contaminant detection in same area [36] | Enables multiplexed detection, high specificity | Requires careful selection of non-interfering reporters [36] |

| Labeled detection (Spatial separation) | Physical separation of detection zones | Lateral flow test strips for multiple targets [36] | Simplified spectral interpretation, compatible with point-of-need formats | Limited multiplexing capacity [36] |

| Surface-Enhanced Resonance Raman Scattering (SERRS) | Combines SERS with resonance Raman effects | Tuberculosis biomarker (ManLAM) detection [39] | 10× lower LOD and 40× increased sensitivity vs. SERS [39] | Requires precise excitation wavelength matching [39] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of Silver-Coated Eggshell Membrane (ESM/Ag) Substrates

The ESM/Ag substrate represents an innovative, cost-effective approach for SERS-based detection, demonstrating significant enhancement factors for standard analytes [37].

Materials Preparation:

- Chicken eggshell membranes (ESM) carefully separated from eggshells

- Dilute acetic acid solution for cleaning

- High-purity silver (99.99%) for thermal evaporation

- Glass slides for substrate mounting

- Ethanol for analyte solution preparation

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- ESM Extraction and Cleaning: Soak chicken eggshells in dilute acetic acid for 15-30 minutes to partially dissolve mineral components. Carefully extract the intact membrane and wash thoroughly with distilled water to remove residual albumen. Air-dry the cleaned membranes at room temperature [37].

Substrate Mounting: Cut dried ESM into uniform pieces (e.g., 1×1 cm) and securely mount onto glass slides using minimal adhesive, ensuring flat, wrinkle-free surfaces for uniform metal deposition [37].

Thermal Evaporation: Place mounted ESM in a thermal evaporation chamber (e.g., Smart Coat 3.0 thermal evaporator). Evaporate high-purity silver at a controlled rate of 0.5 Å/s under vacuum while rotating the substrate (∼8 rpm) to ensure uniform coating. Monitor deposition thickness in real-time using a quartz crystal microbalance. Optimal performance is achieved at approximately 20 nm thickness (ESM/20Ag) [37].

Characterization: Validate substrate quality using Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM) to examine surface morphology, Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) for topological features, and X-ray Diffraction (XRD) to confirm crystalline structure of deposited silver [37].

SERS Measurement Protocol for Trace Detection

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare analyte solutions (4-MBA, 4-MPBA, or R6G) in analytical grade ethanol at appropriate concentrations

- Apply 20 μL of analyte solution onto ESM/Ag substrate (0.5 × 0.5 cm)

- Air-dry completely before spectral acquisition [37]

Instrumentation Parameters (Mira DS Handheld Raman Spectrometer):

- Excitation wavelength: 785 nm

- Spectral range: 400-2300 cm-1

- Resolution: ∼10 cm-1

- Integration time: Adjust based on signal intensity (typically 1-10 seconds) [37]

Data Processing:

- Process raw spectra using Savitzky-Golay Coupled Advanced Rolling Circle Filter (SCARF) for background removal and baseline correction

- Analyze data using custom software (e.g., LabVIEW programming environment) [37]

SERS Enhancement Mechanisms and Detection Strategies

SERS enhancement arises from two primary mechanisms that often work synergistically to amplify Raman signals by several orders of magnitude.

Fundamental Enhancement Mechanisms

Electromagnetic Enhancement (EM): This dominant mechanism originates from localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) excitation when incident light interacts with metallic nanostructures. The LSPR creates intense electromagnetic fields at "hot spots" - nanoscale gaps and sharp features - where Raman signals can be enhanced by factors of 108 or higher. The EM effect is physically mediated and does not depend on the chemical nature of the analyte [36] [35].

Chemical Enhancement (CM): This secondary mechanism involves charge transfer between the metal substrate and analyte molecules, leading to increased polarizability. Chemical enhancement typically provides more modest signal improvements (10-103 fold) but contributes importantly to the overall SERS effect, particularly for molecules forming direct chemical bonds with the substrate [36] [34].

Detection Strategy Selection Framework

Choosing the appropriate SERS detection strategy depends on the analytical requirements, nature of the target contaminants, and available instrumentation.

Table 3: Guidance for Selecting SERS Detection Strategies

| Analytical Scenario | Recommended Strategy | Rationale | Implementation Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single contaminant with strong Raman cross-section | Label-free detection | Simplified preparation, direct measurement | Ensure substrate affinity for target molecule [36] |

| Multiple contaminants in same sample | SERS encoding or spatial separation | Multiplexing capability | Select reporters with non-overlapping peaks for encoding [36] |

| Ultra-trace biomarkers with weak intrinsic signal | SERRS | Combined enhancement mechanisms | Match excitation wavelength to electronic transitions [39] |

| Field-based or point-of-need testing | Spatial separation (lateral flow) | Portability and ease of use | Compatible with handheld Raman systems [36] [38] |

| Gaseous analyte detection | Functionalized substrates (MOFs, LDHs) | Enhanced adsorption of gas molecules | Increase substrate surface area and affinity [40] |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential SERS Materials and Reagents

Successful implementation of SERS detection methodologies requires specific materials and reagents optimized for enhanced performance and reproducibility.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for SERS-Based Detection

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| SERS Substrates | Silver-coated ESM, Cellulose-based substrates, Noble metal nanostructures | Provide plasmonic enhancement through LSPR | Flexible substrates adapt to irregular surfaces [34] [37] |

| Raman Reporter Molecules | 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4-MBA), 5,5'-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), 4-nitrothiophenol (NTP) | Generate distinct Raman signatures for encoded detection | Select reporters with non-overlapping characteristic peaks [36] |

| Functional Materials | Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), Layered double hydroxides (LDHs), Semiconductor nanoparticles | Enhance molecule adsorption, provide additional chemical enhancement | Particularly valuable for gaseous analyte detection [40] |

| Recognition Elements | Antibodies, Aptamers, Molecularly imprinted polymers | Provide molecular specificity for target capture | Essential for labeled detection approaches [36] [39] |

| Reference Analytes | Rhodamine 6G (R6G), 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid (4-MPBA) | System calibration and performance validation | 4-MPBA particularly useful for diol-containing molecules [37] |

SERS technology provides powerful capabilities for ultra-sensitive trace detection of contaminants relevant to optical window research and pharmaceutical applications. The performance comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that substrate selection and detection strategy significantly impact analytical outcomes. Label-free approaches using innovative substrates like silver-coated ESM offer cost-effective solutions with respectable enhancement factors, while encoded strategies enable multiplexed detection of multiple contaminants.

Future developments in SERS technology will likely focus on improving substrate reproducibility through advanced fabrication methods, integrating artificial intelligence for spectral analysis, and creating portable systems for field-deployable contaminant monitoring [36] [35]. The continued refinement of SERS platforms promises even greater capabilities for characterizing and quantifying trace-level contaminants that compromise optical systems and pharmaceutical products.

The analysis of low-concentration analytes is a significant challenge in analytical chemistry, particularly in fields like environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and biomedical research. Sample pre-concentration has emerged as a crucial step to enhance detection sensitivity, especially when coupled with powerful analytical techniques such as Raman spectroscopy. Among various pre-concentration strategies, the 'coffee-ring' effect represents a promising, passively driven approach that can concentrate analytes with minimal instrumentation.

This phenomenon is particularly relevant for detecting trace contaminants on optical components. The gradual accumulation of contaminants on optical windows can severely compromise performance in sensitive applications, including laser systems, imaging devices, and optical sensors. Efficiently concentrating and analyzing these often sparse contaminants is essential for both preventative maintenance and fundamental research. This guide objectively compares the coffee-ring effect with other concentration methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols to inform researcher selection for specific analytical challenges.

Understanding the Coffee-Ring Effect

The coffee-ring effect is a natural phenomenon where suspended particles in a droplet form a dense ring at the edge upon drying. This effect is driven by two key mechanisms: contact line pinning and evaporation-induced capillary flow [41].

When a droplet is deposited on a surface, its outer edge becomes pinned. As evaporation occurs, the liquid at the edge evaporates faster than at the center due to greater surface exposure. To replenish this lost liquid, a capillary flow is established within the droplet, moving liquid from the center to the edge. This flow carries suspended particles to the contact line, where they are deposited and concentrated as the droplet fully dries. The resulting ring-shaped deposit can concentrate analytes by several orders of magnitude, significantly enhancing the signal for subsequent spectroscopic analysis [41].

The efficiency of this concentrating effect is highly dependent on the substrate properties. Hydrophobic surfaces are particularly effective because they promote a high contact angle and facilitate the pinning and evaporation dynamics essential for ring formation. Recent advancements have simplified the creation of such substrates. For instance, a two-step fabrication process using wax-printed nitrocellulose paper can produce a substrate with a water contact angle of 116.60 ± 8.13°, which is comparable to more complexly treated surfaces and significantly more hydrophobic than standard glass slides (30.45 ± 2.69°) [41].

Table 1: Key Factors Influencing Coffee-Ring Effect Efficiency

| Factor | Influence on Concentration Efficiency | Optimal Condition |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Hydrophobicity | Determines contact line pinning and droplet shape | High contact angle (>90°), e.g., wax-printed nitrocellulose |

| Particle/Solute Properties | Affects transport dynamics within the droplet | Uniform, suspendable particles |

| Solvent Composition | Influences evaporation rate and capillary flow | Volatile solvents (e.g., water, ethanol) |

| Environmental Conditions | Controls the rate of evaporation | Stable temperature and humidity |

Comparison of Pre-Concentration Methods

Several pre-concentration methods are available to researchers, each with distinct operational principles, advantages, and limitations. The following section provides a comparative analysis of the coffee-ring effect against other common techniques.

Coffee-Ring Effect vs. Other Common Methods

Table 2: Comparison of Pre-Concentration Methods for Analytical Chemistry

| Method | Principle | Best For | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee-Ring Effect | Evaporation-driven capillary flow | Concentrating particles and analytes from small liquid volumes (µL scale) on surfaces for techniques like SERS. | Simple, low-cost, no specialized equipment, compatible with paper-based platforms, passive operation [41]. | Limited to small volumes, efficiency depends on substrate and particle properties, may not suit all analyte types. |

| Ultracentrifugation | High-speed centrifugal force to pellet particles | Processing larger sample volumes (mL scale) for biological samples like viruses or nanoparticles. | High recovery efficiency (e.g., 25±6% for SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater), handles larger volumes, well-established protocol [42]. | Requires expensive equipment, time-consuming, not easily portable, complex operation. |

| PEG Precipitation | Polymer-induced precipitation of particles | Concentrating viruses and macromolecules from biological fluids and environmental water samples. | Low cost, does not require complex instrumentation, scalable [43] [42]. | Lower recovery efficiency compared to ultracentrifugation (approx. half), longer processing times, can be sensitive to matrix effects [42]. |

| Ultrafiltration | Size-based separation using membranes | Separating and concentrating biomolecules or nanoparticles based on molecular weight cut-off. | Relatively fast, can process small volumes, various molecular weight cut-offs available. | Membrane fouling can occur, potential for analyte loss due to adsorption, may require optimization [42]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction | Adsorption of analytes onto a solid sorbent | Extracting and concentrating a wide range of organic compounds from complex matrices. | High enrichment factors, can be highly selective, can be automated. | Can be expensive, requires solvents (not green), method development can be complex [44]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Empirical data is crucial for evaluating the practical performance of these methods. The following table summarizes key metrics from published studies.

Table 3: Experimental Performance Metrics of Concentration Methods

| Method | Typical Sample Volume | Reported Recovery Efficiency/Performance | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee-Ring Effect | 0.5 - 2 µL | Up to 6-fold signal intensity increase in SERS; LOD of 41.56 nM for 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (MBA) [41]. | Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and analytes are localized in a single, dense ring on hydrophobic paper, enabling sensitive detection [41]. |

| Ultracentrifugation | 30 mL - 1000 mL | 25 ± 6% for SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater [42]. | Most effective method for virus concentration in a comparative study; large-volume processing did not significantly outperform small-volume for ultimate sensitivity [42]. |

| PEG/NaCl Precipitation | 50 mL - 250 mL | Higher sensitivity and viral titer than biphasic PEG-dextran method for SARS-CoV-2 [43]. | A robust and cost-effective method widely used in wastewater-based epidemiology; performance can be matrix-dependent [43]. |

| AlCl3 Precipitation | 30 mL | ~12.5% for SARS-CoV-2 (approx. half that of ultracentrifugation) [42]. | A simple precipitation method, but recovery efficiency may be lower than other techniques [42]. |

Experimental Protocols

Coffee-Ring-Assisted SERS on a Paper-Based Platform

This protocol details the fabrication of a low-cost, wax-printed substrate and its use for concentrating analytes via the coffee-ring effect for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) detection [41].

Materials:

- Nitrocellulose (NC) paper

- Wax printer

- Hot plate or oven (for wax melting)

- Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs)

- Sample of interest (e.g., 4-mercaptobenzoic acid or bacterial cells)

- Micropipette

Procedure:

- Substrate Fabrication: Design a hydrophobic pattern using drawing software. Print the pattern onto the NC paper using a wax printer. Melt the wax by heating the paper on a hot plate or in an oven at ~100°C for 1-2 minutes. The wax will permeate the paper, creating a hydrophobic barrier.

- Sample Preparation: Mix the target analyte with a colloidal suspension of AuNPs. The AuNPs act as both the concentrating particles for the coffee-ring effect and the enhancing substrate for SERS.

- Droplet Deposition: Pipette a small volume (e.g., 0.5 - 2 µL) of the analyte-AuNP mixture onto the center of the hydrophobic region of the prepared paper substrate.

- Drying and Concentration: Allow the droplet to dry at room temperature. As the solvent evaporates, the coffee-ring effect will concentrate the AuNPs and analytes into a narrow ring at the original droplet's edge.

- SERS Measurement: Place the dried substrate under a Raman spectrometer. Focus the laser beam on the concentrated ring to acquire the SERS spectrum.

Application in Contaminant Analysis: A Conceptual Workflow

The following diagram illustrates how the coffee-ring effect can be integrated into a workflow for analyzing contaminants found on optical surfaces, linking to the broader research context.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of pre-concentration strategies, particularly the coffee-ring effect for SERS, requires specific materials and reagents. The table below lists key solutions and their functions.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Coffee-Ring SERS

| Item | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Plasmonic substrate for SERS signal enhancement. | Spherical AuNPs (e.g., 40-80 nm diameter). Consistency in size and shape is critical for reproducible SERS enhancement [41]. |

| Hydrophobic Substrate | Platform for droplet pinning and coffee-ring formation. | Wax-printed nitrocellulose paper [41]. Alternative: chemically modified slides or other engineered hydrophobic surfaces. |

| Nitrocellulose Paper | Porous, white background material for substrate fabrication. | Provides a high-contrast background for visualizing the coffee ring and is compatible with wax printing [41]. |

| Standard Analytes | Validation and calibration of the SERS method. | 4-Mercaptobenzoic Acid: A common Raman reporter for testing SERS platform functionality [41]. |

| Volatile Solvents | Liquid medium for the sample droplet. | Deionized water or ethanol. The solvent choice influences evaporation rate and ring formation dynamics. |

The selection of an appropriate pre-concentration method is a critical decision that directly impacts the sensitivity, cost, and workflow of analytical detection. The coffee-ring effect stands out for its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness in concentrating analytes from microliter volumes directly onto a solid surface, making it exceptionally well-suited for coupling with techniques like SERS. This is highly applicable for detecting trace contaminants on optical components, where traditional methods may be overly complex or expensive.