Raman Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage: A Non-Destructive Guide for Material Analysis and Authentication

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage analysis.

Raman Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage: A Non-Destructive Guide for Material Analysis and Authentication

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage analysis. It explores the foundational principles of this non-destructive technique and its evolution into an indispensable tool for researchers and scientists. The content details methodological approaches for analyzing diverse materials—from pigments and ceramics to metals and organic remains—highlighting both standard and advanced techniques like SERS and portable systems. It also addresses common analytical challenges, such as fluorescence interference, and offers optimization strategies. Finally, the article examines how Raman spectroscopy complements other analytical techniques and discusses future directions, including the role of machine learning in enhancing diagnostic capabilities for artifact preservation and authentication.

The Fundamentals of Raman Spectroscopy: Principles and Evolution in Heritage Science

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique that provides a structural fingerprint by which molecules can be identified, based on the inelastic scattering of light [1]. This phenomenon, known as Raman scattering, occurs when light interacts with molecular vibrations, phonons, or other excitations in a system, resulting in a shift in the energy of the laser photons [1]. The technique is particularly valuable because it directly probes vibration and rotational-vibration states in molecules and materials, allowing for non-destructive and label-free chemical analysis [2]. The core principle revolves around the interaction between incident light and the electron cloud of a molecule, which creates an induced dipole moment based on the molecule's polarizability [1]. For a molecule to exhibit a Raman effect, there must be a change in its electric dipole-electric dipole polarizability with respect to the vibrational coordinate corresponding to the rovibronic state [1]. The resulting spectral fingerprints, typically covering the 500 cm⁻¹ to 1800 cm⁻¹ range for biological samples, contain detailed information about molecular composition and structure [2].

Fundamental Physics of Light-Matter Interaction

The Raman Scattering Phenomenon

The Raman effect originates from the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, usually from a laser in the visible, near infrared, or near ultraviolet range [1]. When a photon interacts with a molecule, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering) with no change in energy. However, a small fraction (approximately 1 in 10 million) undergoes inelastic scattering, resulting in energy shifts that provide information about molecular vibrational modes [3]. This energy shift, known as the Raman shift, is measured in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹) and calculated using the formula:

[ \Delta \tilde{\nu} = \left( \frac{1}{\lambda0} - \frac{1}{\lambda1} \right) ]

where (\Delta \tilde{\nu}) is the Raman shift expressed in wavenumber, (\lambda0) is the excitation wavelength, and (\lambda1) is the Raman spectrum wavelength [1].

Quantum Mechanical Description

From a quantum mechanical perspective, Raman scattering involves transitions between vibrational energy states described by:

[ E_v = h \nu \left( n + \frac{1}{2} \right) ]

where (\nu) is the vibrational frequency, (h) is Planck's constant, and (n) is the vibrational quantum number with integer values [3]. When the final vibrational state is higher in energy than the initial state, the scattered photon is shifted to a lower frequency (Stokes Raman scattering). Conversely, when the final state is lower in energy, the scattered photon is shifted to a higher frequency (anti-Stokes Raman scattering) [3] [1].

Comparison with Infrared Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy provides complementary information to infrared (IR) absorption spectroscopy, as they depend on different molecular properties. While IR spectroscopy depends on the electric dipole moment derivative (atomic polar tensor), Raman spectroscopy depends on the electric dipole-electric dipole polarizability derivative [1]. This contrasting feature means vibrational transitions that are weak or inactive in IR may be strong in Raman spectroscopy and vice versa, following the rule of mutual exclusion in centrosymmetric molecules [1].

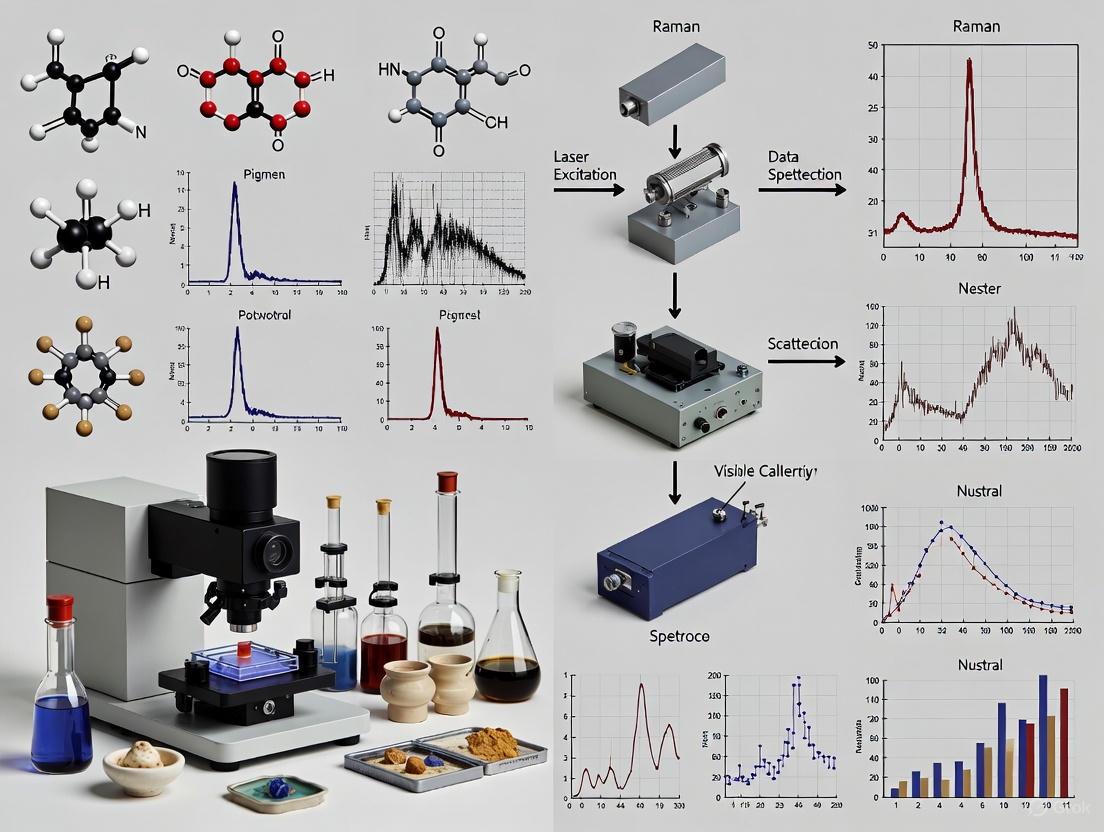

Figure 1: Raman Spectroscopy Workflow. This diagram illustrates the fundamental process from laser excitation to spectrum generation, highlighting the different scattering phenomena.

Molecular Fingerprinting Principle

The "molecular fingerprint" region in Raman spectroscopy refers to the unique pattern of peaks corresponding to specific molecular vibrations that are characteristic of a material's chemical composition [3]. These molecular vibrations are crucial processes in physical chemistry and biochemistry, and studying these fingerprints provides valuable insights into molecular structure and interactions [3]. In biological samples, approximately 90% of Raman peaks are found in the fingerprint spectral region (500 cm⁻¹ to 1800 cm⁻¹), with the remaining found in the higher energy CH/OH stretching vibrational modes (2700 cm⁻¹ to 3300 cm⁻¹) [2]. The specificity of these fingerprints allows researchers to identify chemical bonds, functional groups, and molecular structures, making Raman spectroscopy invaluable for characterizing complex materials without the need for labels or dyes [3] [2].

Quantitative Spectral Interpretation

The intensity of Raman scattering is proportional to the change in polarizability during vibration [1]. Different chemical bonds produce characteristic shifts:

Table 1: Characteristic Raman Shifts for Common Molecular Vibrations

| Molecular Bond/Vibration | Raman Shift Range (cm⁻¹) | Relative Intensity | Chemical Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| C-C stretching | 800-1200 | Strong | Carbon backbone structure |

| C=C stretching | 1500-1680 | Strong | Unsaturation presence |

| C-H stretching | 2850-3000 | Moderate | Aliphatic chains |

| O-H stretching | 3200-3600 | Weak | Hydroxyl groups, water |

| Amide I | 1640-1680 | Moderate | Protein secondary structure |

| S-S stretching | 500-550 | Strong | Disulfide bridges in proteins |

Advanced Raman Techniques

Enhanced Raman Methodologies

Several enhanced Raman techniques have been developed to overcome the inherent weakness of spontaneous Raman scattering:

Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) concentrates electromagnetic energy using metallic nanostructures with surface plasmon optical modes, enhancing Raman scattering intensity by 10⁸ to 10¹¹ magnitudes [3] [2]. This extreme sensitivity enables detection of single molecules and is particularly valuable for identifying low-abundance biomarkers in complex biological samples [3].

Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS) provides spectral information with nanoscale spatial resolution by combining Raman spectroscopy with scanning probe microscopy, allowing characterization at the single-molecule level [2].

Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS) probes deeper into samples than conventional Raman spectroscopy by spatially offsetting the laser excitation and scattering collection regions, enabling non-invasive diagnosis of subsurface features up to 2 mm deep in diffusely scattering samples [3].

Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) and Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS) are coherent Raman techniques that provide much stronger signals relative to spontaneous Raman spectroscopy, enabling real-time imaging of biological processes and materials [2].

Technical Comparison of Raman Modalities

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Raman Spectroscopy Techniques

| Technique | Enhancement Mechanism | Spatial Resolution | Key Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Raman | Spontaneous scattering | Diffraction-limited (~0.5 µm) | General material characterization | Weak signal, fluorescence interference |

| SERS | Plasmonic enhancement on metallic nanostructures | Diffraction-limited to nanoscale | Trace detection, single-molecule analysis | Substrate dependency, reproducibility challenges |

| TERS | Plasmonic enhancement at scanning probe tip | Nanoscale (<10 nm) | Nanomaterial characterization, single-molecule studies | Complex instrumentation, slow acquisition |

| SORS | Spatial offset for subsurface probing | Depth-dependent (up to 2 mm) | Non-invasive deep tissue imaging, layered materials | Reduced signal intensity with depth |

| CARS | Coherent nonlinear process | Diffraction-limited | High-speed chemical imaging, biological tissues | Non-resonant background, complex interpretation |

Experimental Protocols for Cultural Heritage Analysis

Standardized Analytical Workflow for Pigment Identification

Objective: To identify and characterize historical pigments in cultural heritage artifacts using non-destructive Raman spectroscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable Raman spectrometer (532 nm or 785 nm laser excitation)

- Microscopic attachment for small features

- Spectral calibration standards (e.g., silicon wafer at 520.7 cm⁻¹)

- Non-reflective sampling stage

- Computer with spectral processing software (e.g., RamanSPy [4])

Procedure:

Instrument Calibration:

- Perform daily wavelength calibration using a silicon standard

- Verify laser power output with a power meter

- Optimize spectrometer alignment using a reference sample

Sample Preparation:

- Stabilize artifact on non-reflective surface to minimize background

- For portable analysis, ensure proper distance and angle between probe and sample surface

- Document sampling location with microscopic imaging

Spectral Acquisition Parameters:

- Laser power: 1-10 mW (minimize potential damage to sensitive materials)

- Integration time: 1-10 seconds (adjust based on signal intensity)

- Accumulations: 3-10 scans (improve signal-to-noise ratio)

- Spectral range: 200-2000 cm⁻¹ (cover fingerprint region)

Data Quality Assessment:

- Verify signal-to-noise ratio > 10:1 for characteristic peaks

- Check for fluorescence background interference

- Ensure cosmic ray artifacts are removed from spectra

Spectral Interpretation:

- Compare acquired spectra with reference spectral libraries

- Identify key biomarker peaks for specific pigments

- Document peak positions, relative intensities, and bandwidths

Figure 2: Cultural Heritage Analysis Workflow. Standardized protocol for analyzing historical artifacts using Raman spectroscopy, ensuring reproducible results.

Multi-Technique Integration Protocol

Objective: To comprehensively characterize complex cultural heritage materials by integrating Raman spectroscopy with complementary analytical techniques.

Rationale: The combination of multiple spectroscopic approaches provides complementary information for complete characterization of molecular fingerprints in heterogeneous heritage materials [5] [6].

Integrated Workflow:

Initial Non-Invasive Screening:

- Perform macroscopic Raman mapping to identify regions of interest

- Use portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF) for elemental composition

- Document with high-resolution photography

Targeted Molecular Analysis:

- Conduct micro-Raman spectroscopy on specific regions identified during screening

- Employ SERS for enhanced detection of organic colorants

- Utilize FT-IR spectroscopy for complementary vibrational information

Data Correlation and Interpretation:

- Correlate elemental (pXRF) and molecular (Raman/FT-IR) data

- Identify material degradation products and original components

- Compare with historical recipes and reference databases

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Raman Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calibration Standards | Silicon wafer (520.7 cm⁻¹), Acetaminophen, NIST SRM 2241 | Wavelength calibration, instrument performance verification | Use daily for portable instruments; weekly for benchtop systems |

| Reference Materials | RRUFF mineral database [4], Historical pigment sets, Bacterial isolates for contamination ID [4] | Spectral matching and material identification | Maintain institution-specific database of common local materials |

| Sample Preparation | Non-reflective substrates, Conductive adhesive tapes, Micro-sampling tools | Minimize background interference, enable micro-analysis | Test substrate Raman activity before sample mounting |

| Enhancement Substrates | SERS-active nanoparticles (Au/Ag), TERS probes, Plasmonic nanostructures | Signal enhancement for trace analysis | Match plasmon resonance to laser wavelength for optimal enhancement |

| Data Processing Tools | RamanSPy [4], ORPL package [7], BubbleFill algorithm | Baseline correction, cosmic ray removal, spectral analysis | Implement standardized processing pipelines for reproducibility |

Applications in Cultural Heritage Research

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a reliable analytical tool for understanding cultural heritage, with applications evolving from initial phase to advanced stage characterized by integrated application of multi-spectral and multi-assistive techniques [5]. This shift reflects a profound change from analyzing chemical and physical systems to molecular material characterization, now encompassing diverse heritage forms including artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, stones, and crystals [5].

The synergistic combination of Raman, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) and Infrared Spectroscopies has proven particularly valuable for addressing the varied material properties encountered in heritage science [5]. Recent advancements include mobile instrumentation for in-situ analysis, application of multivariate statistical analysis to Raman spectra, and coupling mobile instrumentation with complementary analytical techniques [6]. These developments are crucial for analyzing valuable objects on-site, driven by regulatory constraints and ethical considerations of preserving cultural heritage [6].

Current research focuses on overcoming challenges related to data availability, complexity, and uncertainty through machine learning system development, enhancing Raman spectroscopy detection, and reducing operational costs [5]. These advancements ensure that Raman spectroscopy continues to empower cultural heritage preservation, conservation, and understanding, ultimately enriching our cultural legacy.

Raman spectroscopy has undergone a profound transformation in the field of cultural heritage science, evolving from a specialized laboratory technique to a fundamental, established tool for art conservation and archaeological analysis. This evolution is characterized by critical advancements in instrumentation, data processing, and application methodologies that have collectively addressed the unique challenges presented by priceless and irreplaceable cultural objects [5] [6]. The technique's capacity for non-destructive, non-invasive, and in-situ analysis has positioned it as an indispensable ally for conservators, art historians, and scientists, enabling the detailed molecular characterization of artifacts without the need for sampling [8] [9].

The journey of Raman spectroscopy within cultural heritage is one of adaptation and innovation. Initially constrained by challenges such as fluorescence interference and the bulkiness of equipment, the field has matured through technological breakthroughs. These include the development of portable and handheld instruments, the strategic use of multiple laser wavelengths to minimize fluorescence, and the application of advanced data processing algorithms [6] [10]. This article traces this historical progression, provides detailed experimental protocols for contemporary analysis, and visualizes the workflows that now define this vital scientific discipline.

The Evolutionary Journey: Four Phases of Development

Bibliometric analysis of literature from 1992 to 2024 reveals that the application of spectroscopy in cultural heritage has followed a distinct four-phase evolutionary path [5]. This journey reflects a broader shift from basic chemical analysis to sophisticated molecular-level characterization.

Table 1: Historical Phases of Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage

| Phase | Time Period | Key Characteristics | Major Advancements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I: Initial Emergence | 1992-2002 | Erratic growth; initial exploration of spectroscopic methods for cultural heritage objects [5]. | Foundation laid by conferences and early research; Laser spectroscopy and Raman spectroscopy identified as promising tools [5]. |

| Phase II: Growth & Application | 2002-2008 | Steady growth trend; focus on safety, scientific assessment, and data collection [5]. | Creation of shared heritage material databases; recognition of spectroscopy's utility for conservation management [5]. |

| Phase III: Consolidation | 2008-2015 | Constant use of spectroscopy in conservation science, art technology, and archaeology [5]. | Proliferation of multispectral combining methods; increased analysis of trace samples [5]. |

| Phase IV: Advanced Innovation | 2015-Present | Rapid, steady growth in publications; integration of multi-spectral and multi-assistive techniques [5]. | Synergistic combination of techniques (e.g., Raman-LIBS-IR); rise of machine learning and AI for data interpretation; development of advanced portable instrumentation [5] [9]. |

The field's maturation is further evidenced by the expansion of research themes. From only 24 themes in the initial phase (1992-2002), the field grew to encompass 445 distinct research themes in the current advanced phase (2016-2024), indicating immense diversification and specialization [5]. A pivotal driver of this evolution has been the shift from analyzing isolated chemical systems to the comprehensive molecular characterization of a diverse range of heritage materials, including artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, and crystals [5].

Fundamentals of Raman Spectroscopy

Core Principles

Raman spectroscopy is based on the inelastic scattering of photons by matter, known as the Raman effect [11]. When light interacts with a molecule, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering). However, a tiny fraction (approximately 1 in a million) undergoes inelastic scattering, resulting in a shift in energy that corresponds to the vibrational frequencies of the molecular bonds in the sample [11]. This shift provides a unique molecular "fingerprint" that allows for the identification of specific materials [2].

Key Technical Considerations for Heritage Science

- Resonance Raman Effect: When the laser excitation wavelength matches an electronic transition of the analyte, the scattering intensity of associated vibrational modes can be enhanced by up to 10⁶ times compared to normal Raman scattering [12]. This is particularly useful for analyzing certain pigments.

- Stress and Strain Analysis: The application of stress to a material produces strain, which manifests in Raman spectra through changes in peak position and bandwidth. Compressive stress shifts peaks to higher frequencies, while tensile stress shifts them to lower frequencies [13]. This is crucial for assessing the structural state of materials.

- Laser Wavelength Selection: The choice of laser wavelength is critical. Near-infrared (NIR) lasers (e.g., 785 nm and 852 nm) are widely used in heritage science to minimize fluorescence interference from organic binders and varnishes, which can overwhelm the weaker Raman signal [10].

Detailed Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol 1: Pigment Identification on Manuscripts

Objective: To non-invasively identify the pigments used on illuminated manuscripts, such as 16th–17th century Persian manuscripts, to inform conservation, authentication, and art-historical studies [14].

Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Manuscript Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Pigments Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectrometer | A Renishaw 1000 Ramascope or similar system with a HeNe laser (632.8 nm) for excitation [14]. | - |

| Microscope Objectives | 10x for locating areas of interest; 50x for focusing the laser beam to a small spot size (~1 μm) [14]. | - |

| Reference Databases | Spectral databases (e.g., IRUG, CHSOS, RRUFF) for pigment identification [10] [14]. | Lazurite, Vermilion, Orpiment |

Methodology:

- Manuscript Stabilization: Secure the manuscript on a stable platform to prevent movement during analysis. Do not apply any chemical or mechanical pretreatment.

- Instrument Calibration: Calibrate the spectrometer to better than 1 cm⁻¹ using a neon lamp or other standard before measurement [14].

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Use the optical microscope (10x objective) to locate the area of interest on the manuscript.

- Focus the laser beam onto the sample surface using a 50x objective lens.

- Use low laser power (e.g., <1 mW at the sample) to avoid potential damage to the artifact [14].

- Accumulate spectra with an integration time sufficient to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the acquired spectra to reference databases and published spectra of known pigments to make identifications [14].

Expected Outcomes: Analysis of Persian manuscripts typically reveals a palette including lazurite, red lead, vermilion, orpiment, carbon-based black, lead white, and malachite [14]. A key finding is the use of pigment mixtures rather than a wide range of distinct pigments to achieve different hues. For example, mixtures involving realgar and pararealgar were used to create various orange shades [14].

Protocol 2: In-Situ Analysis of Panel Paintings using a Handheld Spectrometer

Objective: To perform in-situ, non-invasive characterization of pigments and fillers in a complex paint layer, such as a mock-up panel painting prepared with egg-tempera, using a handheld Bravo spectrometer [10].

Materials and Reagents: Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Handheld Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Pigments Identified |

|---|---|---|

| Bravo Handheld Spectrometer | Portable Raman spectrophotometer employing Sequentially Shifted Excitation (SSE) technology with 785 nm and 852 nm lasers to mitigate fluorescence [10]. | Azurite, Lapis lazuli, Indigo |

| Aluminum Foil/Support | To provide a clean, non-interfering background for analyzing pure pigment powders for reference [10]. | - |

| Mock-Up Panel Painting | Artwork with a known composition, featuring a wooden support, ground layer of rabbit glue and gypsum, and an egg-tempera paint layer [10]. | Smalt, Cobalt blue, Prussian blue |

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: For reference powders, place the pigment on a sheet of aluminum foil. Position the Bravo instrument vertically over the powder using supports to avoid interference [10].

- Instrument Settings: The Bravo spectrometer uses two temperature-shifted diode lasers (785 nm and 852 nm). This protocol utilizes the 852 nm laser, covering a spectral range of 170–2200 cm⁻¹ [10].

- Spectral Acquisition:

- Begin with instrument-automated parameters for integration time and accumulations.

- To improve spectrum quality, manually increase the number of scans and integration time as needed (e.g., 0.5–50 s detector integration time with 5–30 accumulations) [10].

- For the panel painting, place the spectrometer head directly onto the painted surface.

- Data Processing: The instrument's internal algorithm (PCA-based) processes the raw data to provide background-free and smoothed spectra, which is particularly helpful for overcoming luminescence from organic materials [10].

Expected Outcomes: This protocol allows for the successful identification of pigments within a complex matrix. It is important to note that some materials may exhibit slightly different spectra, particularly in the relative intensity of Raman lines, when using the 852 nm laser excitation compared to the more standard 785 nm [10]. Building a specific spectral library for the excitation wavelength used is therefore crucial for accurate identification.

In-Situ Raman Analysis Workflow for Cultural Heritage Objects

The Modern Scientist's Toolkit

The contemporary application of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage relies on a suite of advanced techniques and tools that extend beyond the basic spectrometer.

Advanced Raman Techniques

- Portable and Mobile Instrumentation: The development of compact, handheld, and mobile Raman spectrometers has been a game-changer, allowing for in-situ analysis directly in museums, at archaeological sites, and in heritage buildings [8] [6]. This eliminates the need to transport often fragile and invaluable objects.

- Sequentially Shifted Excitation (SSE): This patented technology, used in instruments like the Bravo spectrometer, involves rapidly shifting the laser excitation wavelength over a small range. An internal algorithm then processes this data to effectively mitigate and subtract fluorescent background, yielding a clean Raman spectrum [10].

- Coupling with Complementary Techniques: The combination of Raman spectroscopy with other portable techniques, such as portable X-ray Fluorescence (pXRF), is increasingly common. This hybrid approach provides both molecular information (from Raman) and elemental data (from pXRF), offering a more comprehensive understanding of the material composition of an artifact [6].

- Multivariate Statistical Analysis: As compact devices sometimes yield lower-quality spectra, advanced data processing techniques are essential. The application of multivariate analysis to Raman spectra helps extract meaningful chemical information from complex and noisy data sets [6].

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, the field continues to face challenges that guide its future trajectory [5] [9]:

- Data Complexity and Standardization: The heterogeneity of heritage materials and the complexity of spectral data hinder standardization.

- Operational Costs: The high cost of advanced instrumentation can limit access for smaller institutions.

- Raman Detection Sensitivity: Challenges remain in identifying spectra from degraded, contaminated, or low-signal samples.

Future progress is anticipated in three key areas:

- Accelerating Machine Learning: ML and AI will be crucial for automating complex data interpretation, pattern recognition, and predicting degradation pathways [5] [9].

- Improving Raman Detection: Enhancements in detector sensitivity and laser technology will enable more accurate analysis of delicate samples [5].

- Reducing Operational Costs: The development of more accessible and scalable instrumentation will democratize access to these powerful analytical tools [5] [9].

The journey of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage, from a niche laboratory technique to an established, indispensable tool, is a testament to three decades of interdisciplinary innovation. This evolution, marked by the development of portable instrumentation, advanced fluorescence-mitigation strategies, and sophisticated data processing, has fundamentally transformed our ability to interrogate and preserve humanity's material past. The technique's non-destructive nature provides an ethical foundation for scientific inquiry into priceless artworks and artifacts. As the field moves forward, the integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence promises to further revolutionize data interpretation, while ongoing instrumental refinements will enhance sensitivity and accessibility. Raman spectroscopy has firmly established itself as a bridge between science and the humanities, ensuring that the tangible evidence of human creativity is understood, preserved, and transmitted to future generations.

Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a cornerstone analytical technique in cultural heritage science, offering unparalleled capabilities for non-destructive material analysis. This vibrational spectroscopy technique probes molecular rotational and vibrational states, generating unique spectral fingerprints that enable precise identification and characterization of a wide range of materials found in cultural heritage objects [15]. The technique's fundamental principles, based on the inelastic scattering of light discovered by C.V. Raman and K.S. Krishnan in 1928, provide the foundation for its three key advantages in heritage analysis: non-destructiveness, molecular specificity, and high spatial resolution [16] [17]. These characteristics make it particularly valuable for investigating irreplaceable artifacts where minimal intervention is paramount.

The application of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage has evolved through distinct phases, from initial exploratory studies to the current advanced stage characterized by integrated multi-spectral techniques and machine learning integration [5]. This evolution reflects a profound shift from analyzing simple chemical and physical systems to comprehensive molecular material characterization, now encompassing diverse heritage forms including artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, stones, and crystals [5]. The technique's ability to operate with minimal or no sample preparation, combined with the availability of portable systems for in-situ analysis, has established Raman spectroscopy as an indispensable tool for conservation scientists, archaeologists, and art historians alike [16].

Fundamental Advantages and Their Technical Basis

Non-Destructiveness and Non-Invasiveness

The non-destructive nature of Raman spectroscopy represents its most significant advantage for cultural heritage analysis. This characteristic allows for repeated analysis of the same sample over time without causing damage or alteration to the investigated materials [16]. The technique is strictly noninvasive, enabling the determination of both organic and inorganic components without any chemical or mechanical pretreatment—an essential requirement for rare and valuable samples [8]. This capability is particularly crucial for long-term conservation strategies and monitoring programs where the integrity of artifacts must be preserved for future generations.

The non-destructiveness stems from the fundamental physical process involved: Raman spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source in the visible or near-infrared range [16]. Unlike techniques requiring sample removal or preparation, Raman analysis can be performed directly on artifact surfaces without compromising their structural integrity or aesthetic value. This allows conservators to obtain essential chemical information without the ethical concerns associated with destructive sampling, making it possible to analyze even the most fragile and valuable objects in museum collections and at archaeological sites.

Molecular Specificity and Fingerprinting Capabilities

Raman spectroscopy provides exceptional molecular specificity through its ability to generate unique spectral fingerprints for different chemical compounds [16]. The observed Raman peaks are associated with the chemical structure of molecules and present specific characteristic patterns that enable precise material identification [17]. This molecular-level information allows heritage scientists to distinguish between different pigments, binders, degradation products, and original materials with high confidence, even when dealing with complex mixtures or similar-appearing compounds.

The technique's specificity extends to both organic and inorganic materials commonly encountered in cultural heritage contexts. Raman spectroscopy can identify various cultural heritage materials such as paints, fibers, dyes, woods, stones, inks, and textiles based on their distinct molecular vibrations [16]. This capability has proven invaluable for authenticating artifacts, identifying historical manufacturing technologies, and detecting previous restoration interventions. Furthermore, the technique's ability to analyze samples in aqueous environments without significant interference from water molecules enhances its applicability to a wide range of heritage materials, unlike infrared spectroscopy which experiences strong water absorption [16] [17].

High Spatial Resolution and Imaging Capabilities

Raman spectroscopy offers high spatial resolution, enabling the analysis of micrometer-sized areas on cultural heritage materials [16]. This capability is particularly valuable for investigating heterogeneous samples, stratified layers in painted surfaces, or small details in manuscripts and decorative arts. Modern Raman systems can achieve spatial resolution down to approximately 1 μm with confocal microscopy configurations, allowing for detailed examination of individual pigment grains, corrosion products, or material interfaces [18].

The integration of Raman spectroscopy with digital imaging technology has further enhanced its analytical power through Raman chemical imaging [17]. This hybrid approach provides spatially resolved chemical information, generating detailed images that visualize the distribution of chemical components across a sample surface [17]. For cultural heritage applications, this means conservators can map the distribution of specific pigments across a painting, identify degradation compounds forming at specific locations, or visualize subsurface layers in stratified artifacts, providing crucial information for understanding artistic techniques and deterioration mechanisms.

Table 1: Quantitative Capabilities of Raman Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage Analysis

| Analytical Parameter | Capability/Range | Significance in Cultural Heritage |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~1 μm with confocal microscopy [18] | Analysis of individual pigment grains, fine details, heterogeneous materials |

| Spectral Range | Typically 150-1510 cm⁻¹ [19] | Covers molecular vibrations for most heritage materials |

| Sampling Depth | Variable with technique; subsurface analysis with SORS | Stratified layer analysis, subsurface deterioration |

| Portability | Full portable systems available [16] | In-situ analysis at museums, archaeological sites, historical buildings |

| Water Interference | Minimal compared to IR spectroscopy [16] [17] | Analysis in humid environments, water-containing materials |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard Analysis Protocol for Pigments and Paints

Objective: To identify pigment composition and distribution in painted surfaces, manuscripts, or polychrome sculptures using non-destructive Raman analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Raman spectrometer (portable or benchtop system with microscope)

- Laser sources (typically 532 nm, 785 nm, or 1064 nm wavelengths)

- Calibration standards (silicon wafer for frequency calibration)

- Positioning stage for precise sample manipulation

- Computer with spectral database and analysis software

Procedure:

- Instrument Calibration: Perform daily wavelength calibration using a silicon standard (peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹) to ensure spectral accuracy [16].

- Visual Examination: Conduct preliminary visual inspection of the artifact under magnification to identify analysis areas.

- Laser Wavelength Selection: Choose appropriate laser wavelength based on expected material properties:

- 785 nm for general pigment analysis with reduced fluorescence

- 1064 nm (FT-Raman) for highly fluorescent materials [16]

- 532 nm for enhanced signal strength with non-fluorescent materials

- Parameter Optimization: Adjust laser power (typically 0.1-10 mW at sample), acquisition time (1-30 seconds), and number of accumulations to optimize signal-to-noise ratio while preventing sample damage.

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect spectra from multiple points within the area of interest to account for material heterogeneity.

- Database Comparison: Compare acquired spectra with reference spectral libraries of historical pigments and materials.

- Chemometric Analysis: Apply multivariate statistical methods (PCA, LDA, HCA) for complex mixture analysis and pattern recognition [16] [17].

Quality Control: Include reference materials when possible, document all instrument parameters, and replicate measurements to ensure reproducibility.

Ceramic and Glaze Analysis Protocol

Objective: To determine mineralogical composition and firing technology of ancient ceramics and glazes.

Materials and Equipment:

- μ-Raman spectrometer with confocal capability

- Polarized light microscope for sample observation

- Cross-section preparation materials (if micro-sampling is permissible)

- Reference collections of mineral phases and ceramic technologies

Procedure:

- Sample Selection: Identify representative areas for analysis including ceramic body, slip, glaze, and colored decorations.

- Non-Destructive Surface Analysis: Perform Raman mapping on intact ceramic surfaces to identify mineral phases and their distribution [20].

- Cross-Section Analysis (if micro-samples are available):

- Prepare polished cross-sections to examine stratigraphic layers

- Perform point analysis across different layers to characterize technological features

- Map elemental and mineralogical distribution within the ceramic fabric

- Mineral Identification: Focus on key indicator minerals:

- Quartz (465 cm⁻¹), rutile (612 cm⁻¹), hematite (610 cm⁻¹)

- Silicate phases to estimate firing temperature ranges

- Amorphous phases to identify original firing conditions

- Data Interpretation: Correlate mineral assemblages with potential firing temperatures and atmospheric conditions [20].

Technical Considerations: Use longer wavelength lasers (785 nm or 1064 nm) to reduce fluorescence from amorphous phases in ceramic bodies. Implement extended acquisition times for weak scatterers.

Advanced Technical Approaches

Integration with Chemometric Analysis

The combination of Raman spectroscopy with chemometrics represents a powerful advancement in cultural heritage analysis. Chemometric methods are particularly valuable for analyzing complex mixtures or when spectral bands overlap, significantly simplifying data interpretation [16]. Key chemometric techniques include principal component analysis (PCA), partial least squares regression (PLS), linear discriminant analysis (LDA), and hierarchical cluster analysis (HCA) [16] [17]. These methods reduce the dimensionality of large datasets, allowing researchers to identify key differences and correlations between samples that might not be apparent through visual inspection of raw spectra alone.

Advanced chemometric methods such as multivariate curve resolution (MCR) enable the deconvolution of complex spectra, facilitating the separation of different components in mixtures [16]. This capability is particularly valuable for analyzing heritage materials where natural aging, previous restoration attempts, and complex manufacturing techniques create challenging analytical scenarios. The integration of chemometrics with Raman spectroscopy has proven especially beneficial for classifying artifacts based on their material composition, identifying geographical origins, detecting forgeries, and understanding degradation patterns in complex multi-component systems.

Portable and In-Situ Analysis Methodologies

The development of portable Raman systems has revolutionized cultural heritage analysis by enabling in-situ investigations at museums, archaeological sites, and historical buildings without the need for sample transport [16]. This protocol outlines the methodology for successful field analysis of cultural heritage materials.

Equipment Setup:

- Portable Raman spectrometer with built-in power supply

- Fiber optic probe for access to constrained areas

- Positioning arm or tripod for stability during measurement

- Integrated video microscope for precise area selection

- Environmental protection equipment for outdoor operations

Field Procedure:

- Site Assessment: Evaluate environmental conditions including lighting, temperature, and humidity that might affect measurements.

- Instrument Stabilization: Position and secure the spectrometer to prevent movement during measurements.

- Sample Access: Carefully position the probe head perpendicular to the analysis area, maintaining consistent working distance.

- Preliminary Testing: Perform quick scans to optimize parameters for specific materials and conditions.

- Systematic Documentation: Record measurement locations photographically and schematically for future reference.

- On-Site Validation: Compare initial results with expected material composition to validate data quality before leaving the site.

Challenges and Solutions:

- Ambient Light Interference: Use protective shrouding or conduct analysis during evening/nighttime hours

- Vibration: Implement short acquisition times with multiple accumulations

- Temperature Fluctuations: Allow instrument acclimatization and frequent recalibration

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for Raman Analysis of Cultural Heritage

| Material/Reagent | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon Wafer Standard | Frequency calibration (520.7 cm⁻¹ peak) | Daily instrument calibration [16] |

| Polystyrene Reference | Intensity and resolution verification | Quality control and instrument performance validation |

| Nd:YAG Laser (1064 nm) | Excitation source for FT-Raman | Fluorescence reduction for organic materials [16] |

| RRUFF Database | Reference spectral library | Mineral and pigment identification [19] |

| Micro-fiber Cloths | Surface cleaning before analysis | Removal of loose debris without affecting original materials |

| Positioning Stages | Precise sample manipulation | Mapping and heterogeneous area analysis |

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) with Raman spectroscopy represents a transformative development in cultural heritage analysis. AI algorithms can improve, automate, and accelerate data acquisition as well as processing and quality control tasks [15]. These approaches are particularly valuable for handling the complex, multi-component spectra often encountered in heritage materials, where traditional analysis can be time-consuming and require extensive expert knowledge.

Machine learning methods including convolutional neural networks (CNN), support vector machines (SVM), and probabilistic neural networks (PNN) have demonstrated remarkable success in classifying Raman spectral data [19]. For instance, the fire module convolutional neural network (FMCNN) has achieved classification accuracy of 0.988 for mineral identification based on Raman spectra [19]. These approaches reduce reliance on human participation in routine identifications while maintaining high accuracy, allowing heritage scientists to focus on more complex interpretive challenges. Furthermore, visualization techniques for deep learning models help make the results more interpretable and transparent, addressing the "black box" concern often associated with AI approaches [19].

Multi-Technique Hybridization and Data Fusion

The combination of Raman spectroscopy with other analytical techniques through hybrid approaches provides a more comprehensive understanding of cultural heritage materials. The synergistic combination of Raman, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), and Infrared Spectroscopies has proven particularly powerful for addressing complex analytical challenges [5]. These multi-technique approaches leverage the complementary strengths of different methods, such as Raman's molecular specificity with LIBS' elemental sensitivity, to create more complete material characterizations.

Future developments are focusing on the digitalization of Raman spectroscopy through the incorporation of Open Science and FAIR data principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) [15]. This approach facilitates collaborative research through standardized data formats, metadata schemas, and domain-specific ontologies to ensure machine-actionability and interoperability [15]. The creation of federated databases and open resources in Raman spectroscopy will accelerate methodological developments and improve the reproducibility of analyses across different laboratories and research teams, ultimately strengthening the scientific basis for cultural heritage conservation decisions.

The application of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage science has undergone a profound transformation. Initially employed as a specialized tool for the molecular identification of pigments, its role has expanded to encompass the comprehensive characterization of complex artifact materials, degradation mechanisms, and even mechanical properties. This evolution from a targeted analytical technique to a holistic diagnostic tool is revolutionizing preservation strategies and deepening our understanding of humanity's material past. The non-destructive, non-invasive nature of Raman spectroscopy, which allows for the analysis of unique and irreplaceable artifacts without sampling, remains the cornerstone of its utility in this field [21]. Furthermore, the ability to perform analyses in situ with portable instruments brings the laboratory to the artifact, whether it is in a museum, at an archaeological site, or part of an immovable monument [8] [22]. This application note details the advanced protocols and integrated methodologies that enable this expanded analytical scope, providing a framework for researchers to implement these approaches in their work.

The Evolving Landscape of Raman Spectroscopy in Heritage Science

Bibliometric analysis of the field from 1992 to 2024 reveals a clear trajectory of growth and diversification. Research has evolved from an initial phase of basic chemical analysis to a mature, advanced stage characterized by the integrated application of multi-spectral and multi-assistive techniques [5]. This shift reflects a deeper change in analytical philosophy: from analyzing simple chemical and physical systems to the sophisticated molecular characterization of diverse heritage materials, including artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, stones, and crystals [5].

The table below summarizes the key phases in this evolution, highlighting the expanding scope of research themes and analytical approaches.

Table 1: Evolution of Raman Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage Research (1992-2024)

| Time Period | Phase Designation | Number of Research Themes | Key Developments and Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992-2002 | Initial Phase | 24 | Erratic growth; foundational techniques established; focus on basic material identification [5]. |

| 2003-2008 | Growth & Application | 123 | Steady growth; creation of shared spectral databases; expansion into safety and condition assessment [5]. |

| 2009-2015 | Multispectral Integration | 307 | Proliferation of research themes; common use in conservation science and archaeology; rise of combined/hybrid techniques [5]. |

| 2016-2024 | Advanced Holistic Stage | 445 | Rapid publication growth; integration of machine learning; sophisticated multi-technique synergies (e.g., Raman-LIBS) for holistic artifact profiling [5]. |

A pivotal finding from recent studies is the critical importance of multi-wavelength analysis. Research has demonstrated that some historical pigments exhibit slight but diagnostically crucial variations in their spectral lines when excited with different laser wavelengths, such as 852 nm compared to the more common 785 nm [23]. These differences in relative peak intensity provide enhanced insights into pigment composition, underscoring the need for flexible instrumentation and comprehensive, wavelength-specific spectral libraries to improve the reliability of pigment identification [23].

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Holistic Pigment and Binder Characterization on a Painted Artifact

This protocol is designed for the in-situ analysis of a painted surface, such as a canvas painting or a mural, to identify both inorganic and organic components while minimizing interference from fluorescence.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Equipment

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Handheld Raman Spectrometer | Enables non-destructive, in-situ analysis on the artifact without the need for sampling. Ideal for large or immobile objects [24] [22]. |

| Dual-Wavelength Laser Source (e.g., 785 nm & 852 nm) | Using multiple excitation wavelengths helps overcome fluorescence interference and improves pigment differentiation by revealing wavelength-dependent spectral responses [23]. |

| Anisotropic Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Ag Nanostars) | Used as substrates for Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). Their high degree of anisotropy generates intense "hot spots" that dramatically enhance the signal of weak scatterers like organic dyes and binders [21]. |

| Spectral Library/Database | A comprehensive, curated database of reference spectra is essential for accurate material identification. Libraries specific to cultural heritage materials and, ideally, to the laser wavelength used, are critical [23] [22]. |

| Fiber-Optic Probe (for SERS) | Allows for the safe and controlled application of SERS substrates (nanoparticle colloids) to a micro-area of the artifact for analysis of organic compounds [21]. |

Workflow Steps:

- Project Description & Preliminary Examination: Clearly define the research objectives (e.g., identification of original vs. restoration materials, understanding degradation). Describe the artwork and perform a thorough visual inspection under normal and raking light.

- Selection of Measurement Sites: Using high-resolution reference images, annotate and select specific sites for analysis. Prioritize areas with different colors, visible degradation, or suspected restoration.

- Instrument Setup and Calibration:

- Employ a handheld Raman spectrometer equipped with dual-wavelength lasers (e.g., 785 nm and 852 nm).

- Calibrate the instrument for both wavelength and intensity using a standard reference material (e.g., silicon wafer).

- Define operational parameters: laser power must be set to a safe level to prevent photodegradation (typically <1 mW/µm² at the sample for sensitive materials); spectral range and resolution must be configured.

- Primary Analysis with 785 nm Laser: Conduct initial Raman measurements on the selected sites. The 785 nm laser is effective for many inorganic pigments and less prone to fluorescence than shorter wavelengths.

- Fluorescence Mitigation with 852 nm Laser: If the 785 nm spectrum is overwhelmed by fluorescence, switch to the 852 nm laser. The longer wavelength can often suppress fluorescence and may reveal subtle spectral features not visible at 785 nm [23].

- SERS Analysis for Organic Components: For areas suspected to contain organic dyes (e.g., red lakes, blues) or binders that yield no Raman signal with conventional Raman:

- Apply a small droplet of an anisotropic metal nanoparticle colloid (e.g., silver nanostars) using a micro-pipette under a microscope.

- Allow the droplet to dry, concentrating nanoparticles on the surface.

- Perform Raman analysis directly on the treated area. The plasmonic enhancement provided by the nanoparticles can yield a strong SERS signal, enabling the identification of organic components at trace concentrations [21].

- Data Pre-processing: For all acquired spectra, perform baseline correction to subtract fluorescence background and normalize spectra for comparative analysis.

- Spectral Interpretation and Material Identification: Compare the processed spectra against wavelength-specific reference spectral libraries. Use chemometric tools like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to handle complex spectral datasets and classify materials [16].

- Data Storage and Reporting: Archive all raw and processed spectra with associated metadata (laser wavelength, power, integration time, location on artifact). Prepare a comprehensive report linking material identification to the artifact's condition and history.

Diagram 1: Holistic pigment and binder analysis workflow.

Protocol for Integrated Chemical and Mechanical Analysis via BRaMS

Brillouin and Raman Micro-Spectroscopy (BRaMS) is a novel, label-free technique that simultaneously assesses chemical composition and viscoelastic mechanical properties, which are critical for understanding structural integrity and deterioration phenomena like cracking and embrittlement [25].

Workflow Steps:

- Sample Selection: This protocol is suitable for homogeneous materials or small, representative samples where micro-destructive sampling is permissible. It is ideal for studying varnishes, binders like linseed oil, or modern polymeric materials in heritage collections.

- BRaMS Instrument Configuration: Integrate a Brillouin scattering spectrometer with a confocal Raman microscope into a single experimental setup. This allows for co-localized measurements from the same microscopic spot.

- Co-localized Mapping: Position the sample and define a grid or line scan for mapping.

- The Raman laser (e.g., 785 nm) excites the sample to collect a vibrational spectrum, identifying molecular components.

- The Brillouin probe (often a single-frequency laser like 532 nm) simultaneously measures the inelastic scattering from thermally excited acoustic phonons (sound waves), which provides information on the viscoelastic moduli (e.g., longitudinal modulus) of the material.

- Data Correlation: Process the data to generate correlated maps: one map showing the chemical distribution based on Raman band intensities, and a second map showing the spatial variation of mechanical properties based on Brillouin frequency shifts.

- Interpretation: Correlate areas of chemical alteration (e.g., oxidation identified by Raman) with changes in mechanical properties (e.g., embrittlement indicated by Brillouin). This provides a direct link between molecular change and macroscopic degradation.

Diagram 2: Integrated chemical and mechanical analysis workflow.

The future of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage is inextricably linked to computational science and interdisciplinary collaboration. Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) are poised to revolutionize data processing by enhancing pattern recognition, automating the interpretation of complex spectra from mixtures, and predicting degradation pathways [5] [9]. This will be crucial for managing the growing volume of data from hyperspectral and multi-technique analyses. Furthermore, the development of more sensitive, cost-effective, and portable instrumentation will democratize access to these advanced analytical capabilities, allowing smaller museums and local conservation teams to benefit from cutting-edge technology [5] [9].

In conclusion, Raman spectroscopy has successfully expanded its scope from a tool for simple pigment identification to a core platform for the holistic characterization of cultural heritage artifacts. By integrating advanced techniques like multi-wavelength analysis, SERS with anisotropic nanoparticles, and coupled methods like BRaMS, researchers can now construct a multidimensional profile of an object—revealing not only "what it is" but also "what has happened to it" and "what its future might be." This comprehensive understanding is fundamental to developing effective, long-term, and sustainable preservation strategies for our shared cultural legacy.

Methodologies and Practical Applications: From the Lab to the Field

The analysis of paints and pigments forms a cornerstone of cultural heritage science, enabling the identification of artistic materials, confirmation of provenance, and detection of anachronisms that may indicate forgery. Raman spectroscopy has emerged as a preeminent technique in this field due to its molecular specificity, minimal sample requirements, and adaptability to non-destructive in-situ analysis [6]. This application note details the protocols and methodologies for using Raman spectroscopy, often in combination with complementary techniques, to definitively identify pigment composition and trace the origin of cultural heritage artifacts, directly supporting advanced research within the framework of cultural heritage analysis.

The fundamental principle exploited is the Raman effect, an inelastic scattering process where photons interact with molecular vibrations, producing energy shifts that serve as a unique molecular fingerprint [26]. This allows for the direct identification of pigments based on their chemical structure and crystalline form, even differentiating between pigments with similar elemental compositions [27].

Essential Techniques and Instrumentation

Core Analytical Techniques

A multi-technique approach is often necessary for comprehensive analysis. The table below summarizes the key techniques used in conjunction with Raman spectroscopy for pigment analysis.

Table 1: Core Analytical Techniques for Pigment Analysis

| Technique | Acronym | Primary Information | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy [6] [26] | RS | Molecular fingerprint; chemical structure | Identifies specific molecular phases and crystal structures; minimal sample prep. | Fluorescence interference can mask signals. |

| X-Ray Fluorescence [28] [27] | XRF / HHXRF | Elemental composition | Rapid, non-destructive elemental analysis. | Cannot distinguish different chemical compounds of the same elements. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy [28] [29] | FT-IR | Molecular functional groups | Excellent for identifying organic binders and some degradation products. | Can be affected by water and carbon dioxide. |

| Visible Reflectance Spectroscopy [29] | VRS | Colorimetric properties | Provides quantitative data on color changes and degradation. | Primarily provides surface information. |

Advanced Raman Modalities

To overcome limitations like fluorescence and weak signal intensity, several advanced Raman modalities are employed:

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): Utilizes nanostructured metal substrates to dramatically enhance the Raman signal, enabling the detection of trace amounts of materials, such as organic dyes, which are challenging for conventional Raman spectroscopy [26] [30].

- Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS): Allows for the collection of spectra from subsurface layers, making it possible to analyze pigments beneath varnishes or overpaints without physical sampling [26].

- Micro-Raman Spectroscopy: Couples a Raman spectrometer to a microscope, enabling the analysis of individual pigment grains or specific microscopic features within a heterogeneous sample [30].

Experimental Protocols

In-Situ Pigment Analysis Using Portable Instrumentation

This protocol is designed for the non-destructive analysis of paintings or other cultural heritage objects in situ, such as in a museum setting.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Portable Raman Spectrometer (785 nm laser) | In-situ molecular identification of pigments. | A 785 nm laser minimizes fluorescence from organic binders [31]. |

| Portable XRF (pXRF) Analyzer | Complementary elemental analysis of inorganic pigments. | Used to identify key elements, guiding subsequent Raman analysis [27]. |

| Calibration Standards | Verification of instrument wavenumber accuracy. | Typically a silicon wafer or a standard with known peaks like polystyrene. |

| ColorChecker Chart | Standardization of visible light imaging and color reference. | Used during photographic documentation [27]. |

| Stable Tripod and Positioning Stage | Ensures consistent and safe positioning of the instrument probe. | Prevents accidental contact with the artifact surface. |

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Preliminary Documentation and Visual Examination

- Perform high-resolution visible light photography of the entire object and specific areas of interest. Include a ColorChecker chart for accurate color calibration [27].

- Conduct multispectral imaging:

- Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence (UV): To observe modern restorations (which often appear darker) and the distribution of organic materials like binders or varnishes [27].

- Infrared reflectography (IRR): To potentially reveal underlying sketches (sinopie) or compositional changes (pentimenti) [27].

Elemental Screening with pXRF

- Select multiple measurement points representing different color regions.

- Position the pXRF probe securely and perpendicular to the surface. A typical measurement takes 10-30 seconds per point [27].

- Collect spectra and identify key elements present (e.g., Hg in vermilion/cinnabar, Pb in lead-based pigments like red lead or white lead, Cu in azurite or malachite) [28] [27].

Molecular Identification with Portable Raman Spectroscopy

- Based on XRF results, select points for Raman analysis. The elemental data helps narrow down potential pigments.

- Instrument Settings: Use a 785 nm laser to minimize fluorescence. Power should be optimized to the lowest possible level that still produces a quality signal to avoid any risk of photodamage; start below 20 mW [31]. Acquisition times typically range from 1 to 30 seconds, with 10-20 accumulations to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Collect Raman spectra. The output will be a plot of Raman shift (cm⁻¹) versus intensity.

- Compare the obtained spectra against reference spectral libraries (e.g., the RRUFF database for minerals) for definitive pigment identification [31].

Data Integration and Interpretation

- Correlate data from all techniques. For example, the detection of the element Hg with XRF and a strong Raman peak at 252 cm⁻¹ confirms the presence of vermilion (HgS) [31].

- The combination of techniques helps identify mixtures and layered structures.

Laboratory-Based Analysis for Degradation Studies

This protocol is for a more detailed investigation, which may involve micro-sampling to study pigment-binder interactions and degradation mechanisms.

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Sample Preparation and Artificial Aging

- Create mock-up samples using historical pigments mixed with appropriate binders (e.g., linseed oil, egg tempera).

- Subject these samples to controlled light aging using a solar simulator or other calibrated light sources to simulate long-term degradation [29].

Colorimetric Analysis

- Use Visible Reflectance Spectroscopy to quantitatively measure color changes (∆E) over the aging period. This provides a measurable criterion for degradation [29].

Molecular Analysis of Degradation Products

- Use FT-IR Spectroscopy to monitor the oxidative degradation of the organic binder, observing changes in carbonyl (C=O) and other functional groups [29].

- Use Micro-Raman Spectroscopy to analyze specific pigment particles and look for spectral shifts or the appearance of new peaks that indicate chemical alteration of the pigment itself.

Data Modeling

- Process the spectral data (both Reflectance and FT-IR) using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify the most significant spectral changes correlated with degradation [29].

- Develop spectral response models to forecast pigment behavior under different environmental conditions, informing preventive conservation strategies [29].

Data Interpretation and Critical Analysis

Reference Spectral Data

Successful pigment identification relies on comparison with reliable reference data. The table below lists characteristic Raman shifts for common historical pigments.

Table 3: Characteristic Raman Shifts of Common Historical Pigments

| Pigment Name | Chemical Composition | Characteristic Raman Shifts (cm⁻¹) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vermilion | HgS | 252, 282, 343 [31] | |

| Cinnabar | HgS | 252, 282, 343 [31] | Natural mineral form of Vermilion. |

| Azurite | 2CuCO₃·Cu(OH)₂ | 400, 432, 540, 770, 1090, 1430 [29] | A blue copper carbonate. |

| Lapis Lazuli (Ultramarine) | Na₈–₁₀Al₆Si₆O₂₄S₂–₄ | 548, 580, 802, 1096, ~1640 [28] | The ~1640 cm⁻¹ band is particularly diagnostic [6]. |

| Red Lead (Minium) | Pb₃O₄ | 122, 152, 223, 312, 390, 548 [28] | |

| Carbon Black | C | ~1320 (D band), ~1580 (G band) [28] | Broad bands characteristic of amorphous carbon. |

Integrating Data for Provenance and Authentication

The combination of elemental and molecular information is powerful for tracing provenance. For instance, the identification of Egyptian blue (a synthetic pigment with a specific Raman signature and a composition of CaCuSi₄O₁₀) on an object supposedly from a region where this pigment was not used would raise questions about its provenance [28] [6]. Furthermore, the detection of modern pigments like cadmium red (e.g., CdS) on a painting purportedly from the 17th century is a clear indicator of forgery, as cadmium pigments were not available until the 19th century [31].

Case Study: Gainsborough Paintings

A study on three paintings by Thomas Gainsborough exemplifies this integrated approach [27].

- HHXRF Analysis: Identified the presence of elements such as Pb (lead), Hg (mercury), and Cu (copper) across the paintings, indicating the use of lead-white, vermilion, and copper-based green or blue pigments.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Provided molecular confirmation, specifically identifying vermilion (HgS) by its characteristic Raman fingerprint. This combination allowed researchers to characterize the palette and identify potential later restorations.

- Imaging Techniques: X-ray radiography revealed the artist's compositional changes and the canvas structure, while raking light photography showed the surface topography and brushwork.

The protocols outlined herein demonstrate that Raman spectroscopy, particularly when integrated with complementary techniques like XRF and FT-IR, provides an unparalleled toolkit for the definitive analysis of paints and pigments. The ability to perform non-destructive, in-situ molecular identification makes it indispensable for authenticating artifacts, tracing their provenance, and understanding their material history. Furthermore, the application of advanced data analysis techniques, including machine learning, is poised to further enhance the sensitivity and predictive power of spectroscopic analysis in cultural heritage science [5] [32]. This rigorous analytical approach ensures the preservation of our cultural legacy by providing a scientific basis for conservation, documentation, and art historical research.

Within cultural heritage science, Raman spectroscopy has carved out a critical niche as a non-destructive and highly sensitive analytical technique for diagnosing and conserving invaluable artifacts [33]. Its exceptional ability to elucidate the structural properties of materials is further enhanced when coupled with mathematical and statistical models, enabling researchers to trace the technological and degradation histories of ancient objects [33]. This application note details protocols and illustrative case studies for the examination of ceramics, glass, and stone, framing them within the broader context of a thesis on the application of Raman spectroscopy in cultural heritage research. The focus is on providing researchers and scientists with structured methodologies to extract quantitative data on material composition, manufacturing technology, and assessment of degradation.

Experimental Protocols

Core Raman Spectroscopy Workflow

A standardized workflow is essential for generating reliable, reproducible data, particularly when analyses are performed by different research groups or with different instrumentation [7]. The following protocol, summarized in Figure 1, outlines the key steps from experimental design to data interpretation.

Figure 1. Raman Spectral Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the logical sequence for analyzing Raman spectral data, from experimental design to final interpretation [34].

Protocol 1: Standardized Raman Spectral Acquisition and Processing

1.1 Experimental Design & Sample Size Planning

- Objective: Estimate the minimal number of samples required to reach a statistically meaningful conclusion or build a model with acceptable performance.

- Procedure: Base the sample size on a learning curve that characterizes a predefined metric (e.g., model accuracy) over an increasing sample size. The minimal sample size is identified where the metric no longer improves significantly [34].

1.2 Spectral Preprocessing

- Objective: Remove corrupting effects originating from the instrument, environment, and sample to isolate the Raman signal.

- Cosmic Spike Removal: Detect sharp, intense spikes by comparing successive spectra. Replace affected data points via interpolation or with intensities from adjacent scans [34] [7].

- Baseline Correction: Remove the broad fluorescence background using mathematical approaches such as asymmetric least squares smoothing, polynomial fitting, or the novel BubbleFill algorithm [34] [7].

- Smoothing: Apply a moving-window low-pass filter (e.g., Gaussian) only to highly noisy data, as it can degrade spectral resolution [34].

- Normalization: Suppress fluctuations in excitation intensity or focusing by dividing spectral intensities by the area, maximum, or l2 norm of a selected spectral region [34].

1.3 Data Modeling & Interpretation

- Dimension Reduction: Use unsupervised (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA) or supervised (e.g., Partial Least Squares - PLS) methods to extract useful features and reduce redundant information [33] [34].

- Model Construction & Evaluation: Construct classification or regression models using a training dataset. Evaluate performance with an independent testing dataset using metrics like root-mean-squared error (RMSE) or accuracy in a cross-validation framework [34].

- Model Interpretation: Identify spectroscopic variables that are important to the model and link them to chemical or biological explanations [34].

Specific Protocol for Analyzing Ancient Ceramics

This protocol leverages Raman spectroscopy to determine the firing conditions and composition of ancient pottery.

Protocol 2: Determination of Firing Temperature and Technology in Ancient Potteries

2.1 Sample Preparation

- Objective: Obtain a representative and clean surface for analysis.

- Procedure: If possible, analyze a fresh fracture surface to avoid contamination from burial deposits or previous handling. Gently clean the surface with compressed air or a soft brush. For non-portable samples, use a portable Raman instrument for in-situ analysis [33].

2.2 Spectral Acquisition

- Instrumentation: Use a portable or micro-Raman spectrometer with a Near-IR (NIR) excitation laser (e.g., 1064 nm) to minimize fluorescence from organic residues or the clay body itself [33].

- Parameters: Acquire spectra from multiple points on the sample to account for heterogeneity. Typical acquisition settings might include a 4-8 cm⁻¹ spectral resolution and multiple accumulations to improve the signal-to-noise ratio [33].

2.3 Data Analysis for Firing Temperature Estimation

- Objective: Estimate the maximum firing temperature and furnace permanence time.

- Procedure:

- Identify the spectrum of amorphous carbon (a common temper in clay) and focus on its characteristic D (Disordered) and G (Graphitic) bands.

- Perform a spectral deconvolution of the carbon band region using Lorentzian or Gaussian band shapes.

- Calculate the ratio between the areas of the D and G bands (AD/AG).

- Apply the model established by Ferrari et al. Using the AD/AG ratio and the band positions, estimate the firing temperature. Furthermore, by tracking the transition of carbon from sp³ to sp² hybridization, the permanence time in the oven can be calculated based on the percentage of transformed atoms and an assumed transition time [33].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Key Spectral Signatures and Their Interpretation

Table 1: Key Raman Spectral Bands for Cultural Heritage Materials.

| Material Class | Raman Shift (cm⁻¹) | Vibrational Mode Assignment | Interpretation in Cultural Heritage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceramics / Carbon | ~1350 (D band) | A₁ᵍ mode of disordered graphite | Presence of amorphous carbon; used for firing temperature estimation [33] |

| ~1580 (G band) | E₂ᵍ mode of ordered graphite | Indicates graphitic ordering; AD/AG ratio correlates with thermal history [33] | |

| Pigments / Inorganics | ~2240 | C≡N stretch | Presence of nitrile groups [35] |

| 1700-1730 | C=O stretch | Presence of carbonyl groups, e.g., in binders [35] | |

| General Organic | 2800-3100 | C-H stretching | Detects organic materials; position and shape inform on bonding [35] |

| 3200-3600 | O-H stretching | Indicates hydration or presence of hydroxides; broad band suggests hydrogen bonding [33] [35] |

Case Study: Quantitative Analysis of Early Bronze Age Pottery

Table 2: Quantitative Data Derived from Raman Analysis of Early Bronze IV Pottery from Khirbat Iskandar [33].

| Analyzed Parameter | Observed Spectral Feature | Mathematical Model Applied | Inferred Technological/Degradation Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Firing Temperature | D and G bands of amorphous carbon | Ferrari model for AD/AG ratio and band position | Firing temperature estimated at ~700 °C |

| Furnace Permanence Time | sp²/sp³ carbon hybridization ratio | Kinetic model of atomic transition | Permanence time of ~8 hours per mm³ of amorphous carbon |

| Material Provenance | Presence of Olivine and Anatase | Multivariate analysis (PCA) for mineralogical fingerprint | Geographical tracing of raw materials |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for Heritage Raman Analysis.

| Item | Function / Application | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Portable Raman Spectrometer (1064 nm) | In-situ analysis of precious, non-movable artifacts. | Near-IR laser minimizes fluorescence from aged organic compounds, a common issue in heritage samples [33]. |

| Standard Reference Materials (e.g., NIST SRM 2241) | Wavenumber and intensity calibration of the spectrometer. | Ensures spectral data are comparable across different instruments and measurement sessions [34] [7]. |

| Computational Chemistry Software (e.g., GAUSSIAN) | Density Functional Theory (DFT) simulations. | Models molecular structures and reactions to help identify unknown compounds or degradation pathways from spectral data [33]. |

| Open-Source Data Processing Package (e.g., ORPL) | Standardized preprocessing of raw spectral data. | Provides modular, open-sourced algorithms (e.g., BubbleFill for baseline removal) to ensure reproducibility and data compatibility between labs [7]. |

Advanced Data Modeling and Visualization

The integration of Raman spectroscopy with advanced data modeling is a cornerstone of modern heritage science. For instance, the combination of Raman observables with kinetic or Arrhenius models allows researchers to simulate and understand aging processes and firing technologies [33]. The relationship between key spectroscopic observables and the analytical models they inform is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2. From Spectral Data to Heritage Insight. This diagram illustrates the logical relationship between measured spectroscopic observables, the analytical models they feed into, and the resulting insights into artifact technology and degradation [33] [34].

This application note demonstrates that Raman spectroscopy, particularly when paired with robust experimental protocols and mathematical modeling, is a powerful tool for unraveling the history embedded in cultural heritage materials. The detailed workflows for data processing and the specific protocol for ceramic analysis provide a framework for generating quantitative, reproducible data on the technology and degradation of ceramics, glass, and stone. As the field evolves, the integration of open-source data processing and machine learning promises to further enhance the sensitivity, reliability, and accessibility of Raman spectroscopy, solidifying its role as an indispensable technique in cultural heritage science [33] [5] [7].