Raman vs IR Spectroscopy: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, two pivotal vibrational techniques in pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Raman vs IR Spectroscopy: A Comprehensive Comparative Analysis for Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a detailed comparative analysis of Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, two pivotal vibrational techniques in pharmaceutical and biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles, methodological applications, and practical troubleshooting for each technique. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with the latest advancements—including chemometrics, AI integration, and combined O-PTIR systems—this analysis delivers actionable insights for technique selection, method optimization, and validation to enhance drug discovery, quality control, and process analytical technology (PAT).

Understanding the Core Principles: How Raman and IR Spectroscopy Work

Vibrational spectroscopy is an essential tool for characterizing molecular structures and interactions, with Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy being two of its most prominent techniques. While both methods probe molecular vibrations to generate a unique "fingerprint" for chemical identification, they are founded on fundamentally different physical mechanisms: inelastic light scattering for Raman spectroscopy and direct light absorption for IR spectroscopy [1]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these core mechanisms, supported by experimental data and protocols, to assist researchers in selecting the appropriate technique for their specific applications in drug development and material science.

Core Principles and Mechanisms

Infrared Spectroscopy: The Mechanism of Light Absorption

In IR spectroscopy, molecules are exposed to infrared light. When the frequency of this incident light matches the natural frequency of a molecular vibration, light is absorbed [2]. This absorption directly promotes the molecule to a higher vibrational energy level [1].

For a vibration to be IR-active, it must cause a change in the dipole moment of the molecule [2] [1]. The dipole moment refers to the separation of positive and negative charges within a molecule. A classic example is the asymmetric stretching vibration of CO₂, which alters the charge distribution and is therefore IR-active [1]. The resulting spectrum is a plot of percent transmittance (or absorbance) against wavenumber, showing bands where energy was absorbed [2].

Raman Spectroscopy: The Mechanism of Inelastic Scattering

Raman spectroscopy, in contrast, relies on a scattering process. A monochromatic laser, typically in the visible or near-infrared range, irradiates the sample [1] [3]. Most of the scattered light is at the same energy as the laser (elastic Rayleigh scattering), but a tiny fraction undergoes inelastic scattering, meaning it emerges with a different energy [4].

This inelastic process involves the molecule being excited to a short-lived "virtual state" before relaxing back to a different vibrational state and emitting a photon. If the molecule ends up in a higher vibrational level, the scattered photon loses energy (Stokes shift). If it ends up in a lower vibrational level, the scattered photon gains energy (anti-Stokes shift) [1] [4]. The energy difference between the incident and scattered photons corresponds to the vibrational energy of the molecule.

For a vibration to be Raman-active, it must cause a change in the polarisability of the molecule—that is, the ease with which its electron cloud can be distorted by an external electric field [2] [1]. The symmetric stretch of CO₂, which changes the electron cloud's shape, is Raman-active [1]. The spectrum presents the intensity of this inelastically scattered light versus its Raman shift (cm⁻¹).

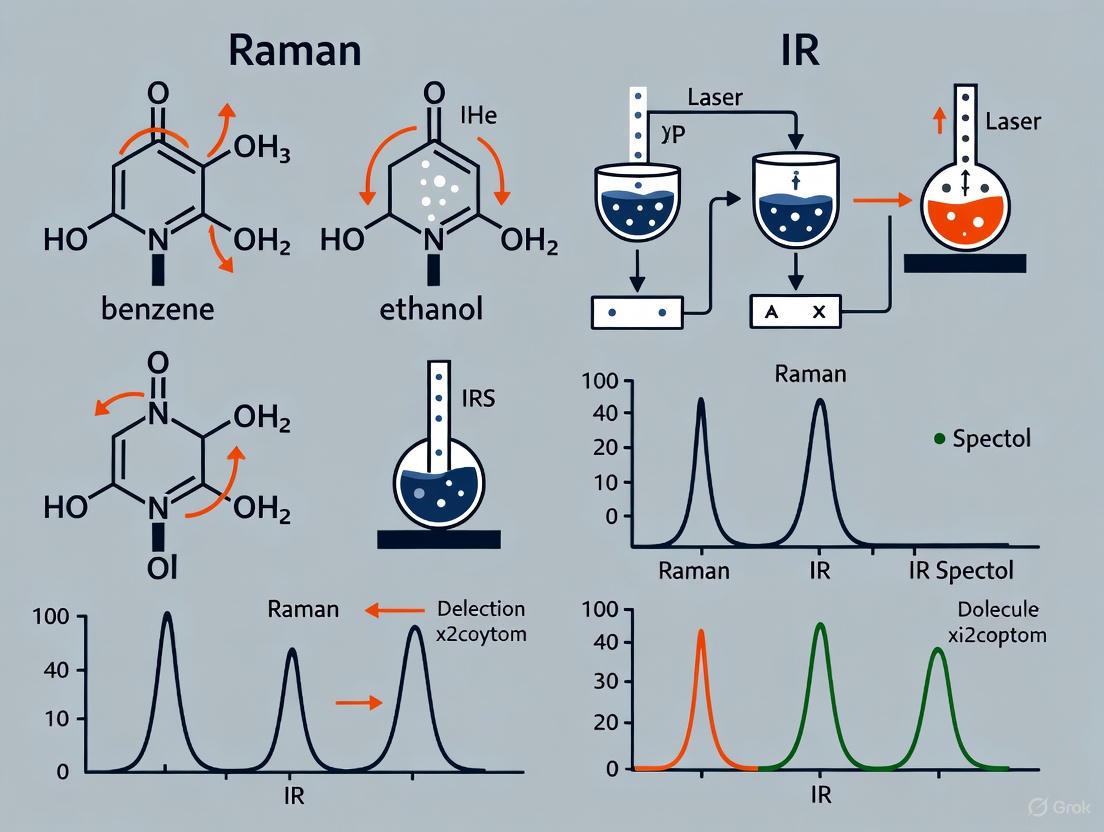

Comparative Workflow: IR Absorption vs. Raman Scattering

The diagram below illustrates the key differences in the fundamental mechanisms of IR absorption and Raman scattering.

Comparative Analysis: Raman vs. IR Spectroscopy

Direct Comparison of Key Parameters

The fundamental differences in mechanism lead to distinct practical advantages and limitations for each technique. The table below summarizes the core differentiating factors.

Table 1: Fundamental and Practical Comparison of Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy | IR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Process | Inelastic scattering of light [1] | Absorption of infrared light [2] |

| Selection Rule | Change in molecular polarisability [2] [1] | Change in dipole moment [2] [1] |

| Permanent Dipole Required | No [2] | Yes |

| Incident Radiation | Visible or Near-IR (e.g., 800-2500 nm) [2] | Mid-IR (e.g., 2.5 - 50 μm) [2] |

| Water as Solvent | Excellent (weak scatterer) [1] [3] | Poor (strong absorber) [2] [1] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; samples can be in glass containers [2] [3] | Can be elaborate; requires IR-transparent materials [2] |

| Key Strength | Analysis of aqueous solutions, covalent bonds [2] | High sensitivity for many functional groups [3] |

| Key Limitation | Fluorescence interference [1] | Strong water absorption [1] |

| Instrument Cost | High [2] [3] | Comparatively inexpensive [2] [3] |

Sensitivity and Performance Data

The performance of each technique can be quantified for specific applications. Recent research on monitoring chlorogenic acid in protein matrices provides comparative experimental data.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics for Phenolic Compound Detection

| Analytical Technique | Target Analytic | Matrix | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTIR Spectroscopy | Chlorogenic Acid | Sunflower Meal | 0.75 wt% [5] | Transmission mode, KBr pellet [5] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Chlorogenic Acid | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | 1.00 wt% [5] | 532 nm laser, 10s accumulation [5] |

| HPLC (Reference Method) | Chlorogenic Acid | Sunflower Meal | Confirmed 5.6 wt% content [5] | Standard chromatographic separation [5] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for IR Spectroscopy Analysis of Chlorogenic Acid

This protocol is adapted from a study on monitoring chlorogenic acid in sunflower meal [5].

Step 1: Sample Preparation (KBr Pellet Method)

- Thoroughly dry the sample (e.g., sunflower meal) and potassium bromide (KBr) at about 100°C for several hours to remove water.

- Precisely weigh approximately 2 mg of the sample and 148 mg of KBr [5].

- Mix and grind the materials together using an agate mortar and pestle to create a fine, homogeneous powder.

- Transfer the mixture into a specialized die and compact it into a pellet using a hydraulic press under a pressure of about 200 kPa (2 atm) for 1.5 minutes [5].

Step 2: Data Acquisition

- Place the prepared pellet in the sample holder of an FTIR spectrometer.

- Record the transmission spectrum in the mid-IR range (4,000–400 cm⁻¹) [5].

- Collect a background spectrum using a pure KBr pellet for reference.

Step 3: Data Analysis

- Identify characteristic absorption bands of chlorogenic acid (e.g., C=O stretch, aromatic ring vibrations).

- For quantification, construct a calibration curve using model samples with known concentrations of chlorogenic acid in the protein matrix.

Protocol for Raman Spectroscopy Analysis in a Protein Matrix

This protocol outlines the procedure for detecting chlorogenic acid in a Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) matrix [5].

Step 1: Sample Preparation for Mapping

- Prepare a series of model samples by mixing and grinding 2, 4, 10, 14, and 20 mg of chlorogenic acid standard with 198, 196, 190, 186, and 180 mg of BSA, respectively, to create a concentration series [5].

- Compact each mixture into a tablet using a pressing mold with a single-axis pressure of approximately 200 kPa for 1.5 minutes [5].

Step 2: Data Acquisition via Mapping

- Place the tablet on a microscope slide under a confocal Raman microscope.

- Use a 532 nm linearly polarized laser for excitation [5].

- Perform mapping on a predefined grid (e.g., 10 × 10 with a step size of 555 μm) to account for sample heterogeneity.

- For each point, acquire the spectrum with an accumulation time of 10 seconds and 2 accumulations [5].

Step 3: Data Analysis

- Process the spectral map to identify the characteristic Raman bands of chlorogenic acid.

- The intensity of key bands can be correlated with concentration to establish a detection limit, which was found to be 1 wt% in the BSA matrix [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Vibrational Spectroscopy Experiments

| Item | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | IR-transparent matrix for preparing solid sample pellets for transmission measurements [5]. | FTIR sample preparation (e.g., for sunflower meal) [5]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A well-defined protein used as a model protein matrix to simulate complex biological samples [5]. | Preparing calibration standards for analyzing compounds in a protein environment [5]. |

| Chlorogenic Acid Standard | A high-purity (>98%) chemical standard used for calibration and method validation [5]. | Quantifying phenolic compounds in plant-based protein sources [5]. |

| Alkali Metal Salts (e.g., NaCl, AgCl) | Materials used to construct IR-transparent windows for liquid or solid sample holders [2]. | Sample cells for IR spectroscopy, though they can be susceptible to water damage [2]. |

| Quartz or Glass Sample Cells | Containers for holding liquid samples during analysis. | Raman spectroscopy of aqueous solutions, as glass is transparent to visible laser light [2]. |

Raman and IR spectroscopy are powerful, complementary techniques for molecular analysis. The choice between them hinges on the fundamental mechanism best suited to the research problem: Raman spectroscopy excels for aqueous samples, covalent systems, and when minimal sample preparation is critical, leveraging its inelastic scattering mechanism. IR spectroscopy is highly sensitive for detecting functional groups with a dipole moment change and is often more cost-effective, relying on the direct absorption of light.

Emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence, are set to enhance the utility of both techniques. For instance, recent advances in AI-driven IR structure elucidation have demonstrated the ability to predict molecular structures from IR spectra with high accuracy, pushing Top-1 identification accuracy to over 63% [6]. This progression towards more powerful, accessible, and intelligent spectroscopic tools promises to further solidify vibrational spectroscopy's role as an indispensable asset in scientific research and drug development.

Molecular vibration techniques, primarily Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, are cornerstone analytical methods for identifying unknown materials and monitoring chemical reactions across pharmaceutical, material science, and biological research [7] [8]. Both techniques probe molecular vibrational energies to generate a unique "molecular fingerprint" for the sample under investigation [9]. Despite this common goal, Raman and IR spectroscopy are governed by different physical mechanisms and selection rules, making them powerfully complementary [7] [8] [9]. IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by molecular bonds that undergo a change in dipole moment during vibration, making it particularly sensitive to polar functional groups [10]. Conversely, Raman spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of light caused by molecular vibrations that induce a change in molecular polarizability, which generally makes it more sensitive to non-polar bonds and symmetric molecular structures [10] [9]. This fundamental difference in mechanism underpins their complementarity and forms the basis for selecting the appropriate technique for specific analytical challenges.

The convergence of these techniques with advanced platforms like scanning probe microscopy has further revolutionized nanoscale chemical analysis, enabling researchers to investigate hierarchical structures in biological materials and advanced nanomaterials with unprecedented resolution [9]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Raman and IR spectroscopy, offering researchers and drug development professionals a detailed framework for technique selection, method implementation, and data interpretation in compound identification.

Fundamental Principles and Technical Comparison

Core Physical Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between Raman and IR spectroscopy lies in their physical interaction with matter. In IR spectroscopy, when the electric field of the infrared light oscillates at a frequency matching a molecular vibration that causes a change in the dipole moment, energy is absorbed [10]. This absorption is measured as a function of wavelength, producing a spectrum that reveals information about functional groups and bond vibrations, making it highly effective for identifying organic compounds [10]. The resulting spectrum plots absorbance or transmittance against wavenumber (cm⁻¹), with characteristic absorption bands corresponding to specific molecular vibrations.

Raman spectroscopy operates on a fundamentally different principle based on light scattering. When monochromatic light interacts with a molecule, most photons are elastically scattered (Rayleigh scattering). However, approximately one in 10⁷ photons undergoes inelastic scattering, where it gains or loses energy corresponding to molecular vibrational frequencies [9]. This energy shift, known as the Raman effect, provides information about the molecular vibrations via changes in polarizability rather than dipole moment [10] [9]. The Raman spectrum plots scattering intensity against the Raman shift (cm⁻¹), revealing vibrational information complementary to IR spectroscopy.

Performance Characteristics and Selection Criteria

The different physical mechanisms of Raman and IR spectroscopy lead to distinct performance characteristics that guide technique selection for specific applications. The following table summarizes the key technical differences:

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Parameter | IR Spectroscopy | Raman Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Principle | Absorption of IR radiation | Inelastic scattering of visible/NIR light |

| Selection Rule | Change in dipole moment | Change in polarizability |

| Spatial Resolution | Diffraction-limited (several to ~15 μm) [10] | Submicron level (can reach <250 nm) [10] [9] |

| Water Compatibility | Strong water absorption interferes with measurements [10] | Minimal water interference; suitable for aqueous solutions |

| Sample Preparation | Often requires thin sections or ATR crystal contact [10] | Minimal preparation; works in reflection mode [10] |

| Key Limitation | Poor spatial resolution, strong water absorbance [10] | Fluorescence interference, poor spectral sensitivity [10] |

The complementarity of these techniques extends to their sensitivity toward different molecular vibrations. IR spectroscopy excels at detecting polar functional groups such as carbonyls (C=O), hydroxyls (O-H), and amines (N-H) [10]. Raman spectroscopy, meanwhile, is particularly effective for analyzing non-polar bonds including carbon-carbon double bonds (C=C), sulfur-sulfur (S-S) bonds, and symmetric molecular vibrations that may be IR-silent [10] [9]. This complementarity means that in many cases, both techniques are required for complete molecular characterization, particularly for complex samples with diverse chemical functionalities.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Measurement Procedures

IR Spectroscopy Protocols typically require specific sample preparation depending on the measurement mode. For transmission FTIR, samples must be thin enough (typically <15 μm) to adhere to the Beer-Lambert law, often requiring compression into KBr pellets for solids or placement between salt plates for liquids [10]. Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR)-FTIR has become increasingly popular as it often requires minimal preparation—the sample is simply placed in direct contact with a diamond or germanium crystal [10]. However, this contact approach risks sample damage or cross-contamination [10]. Reflection mode in traditional IR microscopy often generates spectral artifacts, limiting its application for certain sample types.

Raman Spectroscopy Protocols generally require less extensive sample preparation, as the technique often works effectively in reflection mode without physical contact [10]. Solid samples can typically be analyzed as-is, while liquids can be contained in glass vials or capillaries. However, Raman measurements are extremely susceptible to fluorescence interference, which can overwhelm the weaker Raman signal [10]. Strategies to mitigate fluorescence include using longer wavelength lasers (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm instead of 532 nm), photobleaching samples prior to analysis, or employing surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) to boost signal intensity. The following workflow diagram illustrates the complementary experimental approaches:

Spectral Calibration and Data Processing

Accurate spectral interpretation requires proper instrument calibration and data processing. For Raman spectroscopy, wavelength calibration is typically performed using standard reference materials with known peak positions. A detailed protocol from a DIY Raman spectroscopy initiative for biological research recommends using acetonitrile and neon as calibration standards [11]. The calibration process involves collecting spectra of these standards with the same system configuration and acquisition parameters as the samples of interest, typically using 1,000-10,000 ms exposure for acetonitrile and 1,000 ms for neon, with 0 dB gain and 5 averaged acquisitions [11]. The generated calibration equations then correct all sample data, ensuring accurate peak assignment.

For IR spectroscopy, calibration verification is typically performed using polystyrene films, which exhibit characteristic absorption bands at known wavenumbers. Modern FTIR instruments often include automated validation protocols to ensure spectral accuracy and reproducibility. Data preprocessing for both techniques may include normalization, scatter correction, baseline correction, and noise reduction to enhance spectral quality and facilitate accurate interpretation [12]. Advanced chemometric approaches, including principal component analysis (PCA) and partial least squares (PLS) regression, are increasingly integrated with both techniques to extract meaningful information from complex spectral datasets [12].

Comparative Analysis and Complementary Applications

Pharmaceutical and Biopharmaceutical Applications

The pharmaceutical industry represents a major application area for both Raman and IR spectroscopy, driven by stringent regulatory requirements and the need for precise compound identification. IR spectroscopy is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis for identifying active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), excipients, and polymorphic forms through their characteristic functional group vibrations [13] [14]. The technique's sensitivity to polar bonds makes it ideal for quantifying specific functional groups and monitoring chemical reactions in real-time.

Raman spectroscopy offers complementary advantages for pharmaceutical applications, particularly its minimal interference from water, which enables the analysis of hydrates and aqueous formulations without extensive sample preparation [10]. Raman is also highly effective for characterizing crystal polymorphs, which often exhibit distinct Raman spectra despite nearly identical IR profiles. The spatial resolution of Raman microscopy (down to submicron levels) allows for mapping API distribution within solid dosage forms, detecting phase separations, and identifying contaminants in drug products [10] [9].

The growing investment in pharmaceutical research and development—exemplified by the UK's pharmaceutical R&D budget of approximately $49.6 billion (£39.8 billion) for 2022-2025—continues to drive adoption of both spectroscopic techniques throughout drug discovery, development, and quality control processes [14].

Materials Science and Industrial Applications

In materials science, the complementary nature of Raman and IR spectroscopy enables comprehensive characterization of complex material systems. IR spectroscopy excels at identifying organic components in polymers, composites, and coatings through their functional group fingerprints [10]. The development of portable and handheld IR devices has expanded applications to field-based analysis, including environmental monitoring, food safety testing, and industrial quality control [15].

Raman spectroscopy provides unique capabilities for analyzing carbon-based materials, semiconductor structures, and inorganic compounds that may yield weak or complex IR spectra [10]. The technique's superior spatial resolution enables detailed mapping of phase distributions, stress states, and molecular orientation in advanced materials. The non-destructive nature of Raman analysis makes it particularly valuable for analyzing precious samples, cultural heritage artifacts, and forensic evidence.

The market data reflects the growing adoption of these complementary techniques. The Raman spectroscopy research market is projected to grow at a CAGR of 16.05% from 2026 to 2033, reaching $16.02 billion by 2033 [13]. Similarly, the IR spectroscopy market is expected to reach $2.29 billion by 2032, growing at a CAGR of 7.3% from 2025 [16]. The combined NIR and Raman spectroscopy market specifically is projected to grow from $2.05 billion in 2025 to $3.56 billion in 2029 at a CAGR of 14.8% [14].

Table 2: Application-Based Technique Selection Guide

| Application Area | Recommended Technique | Rationale | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions | Raman Spectroscopy | Minimal water interference [10] | Solute concentration, molecular conformation |

| Polymer Characterization | Both Complementary | IR: functional groups; Raman: backbone structure [10] | Crystallinity, orientation, additive distribution |

| Pharmaceutical Polymorphs | Both Complementary | Different sensitivity to molecular packing | Polymorphic identity, distribution, purity |

| Biological Tissues | Both Complementary | IR: protein secondary structure; Raman: non-polar components [9] | Protein/lipid ratio, disease markers, cellular components |

| Microplastics Analysis | AFM-IR (Nanospectroscopy) | Submicron spatial resolution for small particles [10] | Polymer identification, particle size distribution |

| Process Analytical Technology | NIR Spectroscopy | Rapid, non-invasive analysis through containers [14] | Reaction monitoring, blend uniformity, content uniformity |

Advanced Integration and Emerging Trends

Nanoscale and Correlative Spectroscopy

The convergence of Raman and IR spectroscopy with scanning probe microscopy has created powerful new paradigms for nanoscale analysis, overcoming the diffraction limit of conventional optical techniques [9]. Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS) combines the chemical specificity of Raman spectroscopy with the spatial resolution of atomic force microscopy (AFM), enabling Raman mapping at the nanoscale [9]. Similarly, Photothermal Induced Resonance (PTIR), also known as AFM-IR, provides IR spectroscopic information at spatial resolutions down to 20 nm, far beyond the conventional diffraction limit of IR microscopy [9].

These nanoscale techniques enable researchers to correlate chemical composition with morphological features at previously inaccessible resolution levels, opening new opportunities in semiconductor characterization, polymer blend analysis, biological membrane studies, and nanopharmaceutical development [9]. The recent development of optical photothermal infrared (O-PTIR) technology represents a significant advancement, enabling simultaneous submicron IR and Raman spectroscopy from the exact same sample location [10]. This simultaneous measurement eliminates uncertainties associated with sequential analysis on different instruments and provides perfectly co-registered complementary datasets.

Artificial Intelligence and Automation

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning with both Raman and IR spectroscopy is transforming spectral analysis across applications. In Raman spectroscopy, AI algorithms enable automated spectral identification, classification of complex biological samples, and real-time decision-making in process analytical technology (PAT) applications [13]. Companies are developing smart spectrometers with AI capabilities to improve accuracy and reduce analysis time, particularly in pharmaceutical and clinical settings [13].

Similarly, IR spectroscopy benefits from AI-enabled spectral libraries that automate compound identification by matching unknown spectra against vast databases in seconds, reducing dependency on manual interpretation and minimizing human error [15]. Predictive modeling algorithms extend this capability by correlating spectral features with material properties, guiding researchers toward novel compound discovery and accelerating development cycles in pharmaceutical and material science applications [15].

The implementation of DIY Raman systems with open-source data analysis pipelines, as demonstrated by Arcadia Science's repository for biological research, further democratizes access to advanced spectroscopic capabilities [11]. These systems combine affordable hardware with standardized calibration protocols and Python-based data processing scripts, making vibrational spectroscopy more accessible to research groups with limited instrumentation budgets [11].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of Raman and IR spectroscopic analysis requires specific calibration standards and sampling accessories. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in vibrational spectroscopy:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Vibrational Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Accessory | Primary Application | Function | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetonitrile | Raman Calibration Standard | Wavelength calibration reference | Peak positions: 2253 cm⁻¹ (C≡N stretch), 2943 cm⁻¹ (C-H stretch) [11] |

| Neon Lamp | Raman Calibration Standard | Wavelength calibration reference | Multiple emission lines across visible spectrum [11] |

| Polystyrene Film | IR Calibration Standard | Wavelength accuracy verification | Characteristic IR bands: 1601 cm⁻¹, 1493 cm⁻¹, 1028 cm⁻¹ |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond/Ge) | IR Sampling Accessory | Internal reflection element | Diamond: broad IR transmission; Germanium: high refractive index [10] |

| KBr Powder | IR Sample Preparation | Pellet matrix for transmission measurements | Transparent in mid-IR region; forms transparent pellets under pressure |

| Silicon Wafer | Raman Reference Standard | Intensity calibration and background | Characteristic peak at 520 cm⁻¹ for Raman shift verification |

| Tungsten-Halogen Lamp | NIR Light Source | Broadband illumination for NIR spectroscopy | Typical lifespan: 1,000-2,000 hours; blackbody emission profile [14] |

| Quantum Cascade Laser | Advanced IR Source | Tunable, high-brightness IR source for microspectroscopy | Pulse lengths: 10-500 ns; repetition rates: 1-1750 kHz [9] |

Raman and IR spectroscopy provide powerful, complementary approaches for compound identification through molecular fingerprinting. While IR spectroscopy excels at detecting polar functional groups and is well-established for qualitative analysis, Raman spectroscopy offers advantages for aqueous samples, non-polar bonds, and high-resolution mapping. The selection between these techniques should be guided by sample characteristics, information requirements, and analytical constraints rather than treating them as competing alternatives.

Emerging technological integrations—including combined IR-Raman systems, nanoscale spectroscopy techniques, and AI-enhanced data analysis—are pushing the boundaries of vibrational spectroscopy beyond traditional applications. These advancements enable researchers to address increasingly complex analytical challenges in pharmaceutical development, materials characterization, and biological research with unprecedented precision and efficiency. As both techniques continue to evolve through miniaturization, automation, and enhanced computational analysis, their synergistic application will remain fundamental to decoding complex spectral information for compound identification across scientific disciplines.

Vibrational spectroscopy techniques are indispensable tools for material identification and reaction monitoring, with Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy being two of the most prominent methods. While both techniques probe the vibrational energy levels of molecules, they operate under fundamentally different selection rules governed by distinct physical principles. Raman spectroscopy measures the inelastic scattering of light and depends on changes in molecular polarizability during vibrations, whereas IR spectroscopy involves the absorption of light and requires changes in the permanent dipole moment of the molecule [17] [18]. This fundamental difference makes the two techniques highly complementary, often revealing different aspects of molecular structure and dynamics.

The selection rules governing these spectroscopic methods determine which vibrational modes are "active" or "observable" in each technique. Understanding the role of polarizability and dipole moment changes is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals to select the appropriate analytical method for their specific application, interpret spectral data accurately, and gain comprehensive molecular-level insights into their systems of interest [7] [8]. This comparative guide provides an objective analysis of both techniques, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to pharmaceutical and materials science applications.

Theoretical Framework: Polarizability vs. Dipole Moment

Molecular Polarizability in Raman Spectroscopy

Polarizability refers to the ease with which the electron cloud of a molecule can be distorted by an external electric field, such as that of an incident photon [18]. Raman activity occurs when a molecular vibration causes a change in this polarizability. The Raman scattering intensity is proportional to the square of the change in polarizability during the vibration, making symmetric vibrations particularly prominent in Raman spectra [18].

During Raman scattering, incident photons interact with the molecule's electron cloud, resulting in energy transfer to or from the molecular vibrations. This inelastic scattering produces shifted frequencies in the scattered light that correspond to the vibrational energies of the molecule. The Raman shift, measured in wavenumbers (cm⁻¹), provides a molecular fingerprint based on polarizability changes during vibrations [18].

Dipole Moment Changes in Infrared Spectroscopy

In contrast, IR spectroscopy detects molecular vibrations that produce a change in the permanent dipole moment of the molecule [18]. When a vibration causes a fluctuation in the molecular dipole moment, it can interact with the oscillating electric field of IR radiation, leading to absorption of specific frequencies. This absorption forms the basis of IR spectroscopy, with the absorption frequency corresponding to the vibrational energy [2].

The requirement for a dipole moment change means IR spectroscopy is particularly sensitive to asymmetric vibrations and functional groups with strong dipole characteristics, such as carbonyl groups, hydroxyl groups, and other heteroatom-containing moieties [18].

Symmetry Considerations and Complementarity

The different selection rules based on polarizability and dipole moment changes make Raman and IR spectroscopy highly complementary techniques. For molecules with a center of symmetry (centrosymmetric molecules), a mutual exclusion principle often applies: vibrational modes that are Raman-active are IR-inactive, and vice versa [18]. For instance, in carbon dioxide (CO₂), the symmetric stretch is Raman-active but IR-inactive, while the asymmetric stretch is IR-active but Raman-inactive [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy | Infrared Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Basis | Inelastic scattering of light | Absorption of light |

| Selection Rule | Change in polarizability | Change in dipole moment |

| Symmetric Vibrations | Strongly active | Often inactive |

| Asymmetric Vibrations | Often inactive | Strongly active |

| Centrosymmetric Molecules | Mutual exclusion principle applies | Mutual exclusion principle applies |

| Aqueous Solutions | Well-suited (weak water signal) | Problematic (strong water absorption) |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Raman Spectroscopy Experimental Setup

Modern Raman instrumentation typically consists of three core components: a laser source, sampling optics, and a detector [19]. The choice of laser wavelength is critical, with most pharmaceutical and bioprocessing applications utilizing near-infrared wavelengths (785 nm or 830 nm) to minimize fluorescence interference while maintaining acceptable scattering efficiency [19].

Several sampling configurations are available for different applications:

- Backscattered Raman: Traditional configuration with minimal separation between excitation and collection fibers, primarily collecting signal from superficial layers [19]

- Wide Area Raman: Utilizes a defocused laser beam to illuminate a large area, improving sampling representativeness for both superficial and deep layers [19]

- Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS): Employs larger separation (1-3 mm) between illumination and collection fibers to preferentially collect subsurface signals, even through millimeters of turbid media [19]

- Transmission Raman: Excitation on one side of a sample with collection on the opposite side, providing bulk measurement capability and suppressing fluorescence from superficial layers [19]

For bioprocessing applications, particularly in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell culture monitoring, specialized immersion probes with 785 nm excitation are typically employed to overcome autofluorescence from intracellular NADH and flavins [19].

Infrared Spectroscopy Experimental Protocols

Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy has become the standard implementation of IR spectroscopy due to its superior speed and sensitivity compared to dispersive instruments. Sample preparation is more critical for IR spectroscopy, with common techniques including:

- Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR): Allows direct measurement of solids and liquids with minimal preparation

- Transmission cells: For liquid samples with controlled pathlengths to manage strong solvent absorptions

- KBr pellets: For solid powder analysis, though this technique is being replaced by ATR in many applications

A recent pharmaceutical stability study demonstrated FT-IR coupled with hierarchical cluster analysis in Python for assessing similarity of secondary protein structures in biotherapeutics under varying storage conditions [20].

Data Analysis Approaches

Both Raman and IR spectroscopy data can be analyzed using univariate or multivariate approaches. Univariate analysis focuses on specific band features (area, intensity, center of gravity) and is often reported as band ratios [19]. Multivariate analysis employing chemometric methods like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is increasingly common, especially for complex biological or pharmaceutical samples [20] [19].

Machine learning integration has significantly advanced Raman applications, as demonstrated in a 2023 bioprocessing study where hardware automation and machine learning reduced calibration efforts while enabling product quality measurements every 38 seconds [20].

Comparative Analysis: Applications and Performance Data

Pharmaceutical Applications

Table 2: Pharmaceutical Applications of Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Application | Raman Strength | IR Strength | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymorph Identification | Excellent for API forms [19] | Limited by sampling depth | Raman identified and quantified polymorph mixtures [19] |

| Protein Structure | Secondary structure in aqueous environments [20] | Secondary structure in solid state [20] | FT-IR with HCA analyzed protein drug stability [20] |

| Process Monitoring | Real-time in situ monitoring [20] [19] | Limited for aqueous systems | Inline Raman monitored 27 cell culture components [20] |

| Quantitative Analysis | Excellent with multivariate calibration [19] | Good for non-aqueous systems | Raman enabled real-time release testing [19] |

Biological and Biopharmaceutical Applications

In bioprocessing and biopharmaceutical applications, Raman spectroscopy has demonstrated significant advantages, particularly for real-time monitoring. A 2024 study showcased Raman's capability for inline monitoring of cell culture processes, establishing models for 27 components with predictive R-squared values (Q²) exceeding 0.8 for most analytes [20]. The methodology successfully identified and eliminated anomalous spectra while demonstrating effectiveness in detecting bacterial contamination through control charts [20].

IR spectroscopy faces limitations in biological systems due to strong water absorption, though it remains valuable for solid-state protein structure analysis. A recent stability study of protein drugs utilized FT-IR with hierarchical cluster analysis to assess secondary structure similarity across different storage conditions, demonstrating maintained stability despite temperature variations [20].

Material Identification and Characterization

For material identification, the complementary nature of Raman and IR spectroscopy is particularly valuable. Symmetric vibrations such as C-C stretching in carbon chains (∼1000 cm⁻¹) and breathing modes in aromatic rings produce strong Raman signals but weak IR signals [18]. Conversely, asymmetric vibrations including C=O stretching (∼1700 cm⁻¹) and O-H stretching (∼3300 cm⁻¹) yield strong IR bands but weak Raman signals [18].

The combination of both techniques provides a comprehensive vibrational profile, as demonstrated in studies of octasulfur, where molecular symmetries and group theory were used to determine allowed vibrational modes for each technique [17] [7] [8].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 785 nm Laser | Excitation source for Raman | Reduces fluorescence in biological samples [19] |

| Fiber Optic Probes | In situ sampling | Various configurations (backscatter, SORS, transmission) [19] |

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | IR sampling without preparation | Enables direct solid and liquid measurement |

| SERS Substrates | Signal enhancement | Gold/silver nanoparticles for trace detection [20] [21] |

| Reference Standards | Instrument calibration | Polystyrene for Raman, polystyrene films for IR |

| Cell Culture Media | Bioprocess monitoring | Requires NIR lasers to avoid autofluorescence [19] |

Advanced Techniques and Emerging Applications

Enhanced Raman Techniques

Several advanced Raman techniques have been developed to address specific analytical challenges:

- Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS): Utilizes plasmonic nanostructures to dramatically enhance Raman signals, enabling single-molecule detection and trace analysis [20] [21]

- Tip-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (TERS): Combines scanning probe microscopy with Raman spectroscopy for nanoscale spatial resolution [20]

- Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS): Enables subsurface analysis through turbid media and packaging [19]

- Transmission Raman: Provides bulk characterization of pharmaceutical formulations with minimal sampling error [19]

Pharmaceutical Manufacturing and PAT

The adoption of Quality by Design (QbD) principles and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiatives has driven Raman spectroscopy integration into pharmaceutical manufacturing [19]. Raman systems are now successfully implemented in real-time release testing, continuous manufacturing, and statistical process control [19]. A 2023 study demonstrated real-time measurement of product aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing using hardware automation and machine learning, achieving measurements every 38 seconds [20].

Raman and IR spectroscopy offer complementary approaches to molecular vibrational analysis governed by fundamentally different selection rules. Raman spectroscopy probes changes in molecular polarizability, making it ideal for symmetric vibrations, aqueous solutions, and real-time process monitoring. IR spectroscopy detects changes in dipole moment, excelling for asymmetric vibrations, functional group identification, and solid-state analysis.

The choice between these techniques depends on the specific analytical requirements, sample characteristics, and information needs. For comprehensive molecular characterization, particularly in pharmaceutical development and bioprocessing, the combined application of both techniques often provides the most complete understanding of molecular structure, dynamics, and interactions. As both technologies continue to advance, particularly with integration of machine learning and enhanced sampling methods, their value in research and industrial applications continues to grow.

The comparative analysis of Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy techniques reveals two powerful, yet fundamentally different, approaches to probing molecular vibrations. While both techniques provide characteristic "fingerprints" of molecular structure and composition, their instrumentation configurations differ significantly due to their distinct physical mechanisms. IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light when molecular bonds undergo a change in dipole moment during vibration. In contrast, Raman spectroscopy relies on the inelastic scattering of light from a monochromatic source, detecting energy shifts resulting from changes in molecular polarizability [1] [22]. This fundamental difference dictates unique requirements for their respective key components—from light sources and wavelength selection systems to detectors and sampling interfaces. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these instrumental architectures to inform researchers and drug development professionals selecting appropriate characterization tools for specific applications.

Core Instrumentation Comparison

The following table summarizes the key components and their specifications for Raman and IR spectroscopy systems.

Table 1: Instrument Component Comparison: Raman vs. Infrared Spectroscopy

| Component | Raman Spectroscopy | Infrared Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Monochromatic laser (UV, Vis, or NIR). Common types: diode, Nd:YAG, argon-ion [22]. | Broadband infrared source. Common types: globar (silicon carbide), tungsten-halogen, deuterium, synchrotron, or Quantum Cascade Laser (QCL) [23] [22]. |

| Wavelength Range | Typically UV (e.g., 244 nm, 325 nm), Visible (e.g., 532 nm, 633 nm), or NIR (e.g., 785 nm, 1064 nm) lasers [22]. | Mid-infrared (MIR: 4000 - 400 cm⁻¹) is most common for spectroscopy [22]. |

| Spectral Separation | Monochromator or spectrometer with a grating, often coupled to a CCD detector. Requires high-efficiency notch or edge filters to block the intense Rayleigh line [24]. | Interferometer (most common in modern systems), utilizing a Michelson design with a moving mirror for Fourier Transform IR (FTIR). Also, diffraction gratings in dispersive instruments [23]. |

| Detector | Typically a Charge-Coupled Device (CCD) detector, often cooled to reduce noise [24]. For NIR excitation (e.g., 1064 nm), InGaAs detectors are used [7] [8]. | Common detectors include Deuterated Triglycine Sulfate (DTGS) and Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT). MCT detectors are faster and more sensitive but require cooling with liquid N₂ [23]. |

| Sampling Interface | Conventional free-space optics or fiber optic probes. Microspectroscopy is achieved by coupling the spectrometer to a standard optical microscope [22]. | Sampling modes include Transmission, Transflection (on reflective substrates), and Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) using crystals like diamond or ZnSe [23]. |

| Key Advantage | Minimal interference from water, making it suitable for aqueous solutions and biological samples. Excellent for measuring low-frequency vibrations [1]. | Simpler instrument operation and widespread adoption. Direct absorption measurement is generally more sensitive than the weak Raman scattering effect [1]. |

| Key Limitation | Susceptible to fluorescence interference, which can swamp the much weaker Raman signal. The laser can also damage sensitive samples [1]. | Strong absorption by water requires specialized techniques (e.g., ATR) or sample dehydration for aqueous samples. Sample preparation can be more demanding [22]. |

Experimental Protocols and Data Acquisition

Standard Procedure for FTIR Spectroscopy

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is the dominant modern IR technique due to its speed and sensitivity. The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for analyzing a biological tissue section in transmission mode [23].

- Step 1: Sample Preparation. For transmission measurements, tissue sections are typically cut to a thickness of 5–10 µm and placed on an IR-transparent substrate like barium fluoride (BaF₂). The sample must be thin enough to avoid complete absorption of the IR beam. For hydrated biological samples, the strong water absorption bands necessitate the use of Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) accessories, which minimize the path length, or careful dehydration of the sample [23] [22].

- Step 2: Instrument Setup and Background Collection. The instrument is configured for the desired sampling mode (transmission, ATR, etc.). A background spectrum (a scan of the environment without the sample) is collected first. This is critical for FTIR as it allows the instrument to subtract the background signal from the sample spectrum later.

- Step 3: Spectral Acquisition. The sample is placed in the beam path. The interferometer in the FTIR instrument scans the moving mirror, collecting an interferogram. This interferogram is then Fourier-transformed to generate a spectrum. Typical parameters include a spectral resolution of 4-8 cm⁻¹ and 64-256 co-added scans to achieve a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio [23].

- Step 4: Data Pre-processing. The raw spectrum undergoes pre-processing, which includes atmospheric correction (removal of CO₂ and H₂O vapor bands), baseline correction, and sometimes smoothing or derivation (e.g., using the Savitzky-Golay algorithm) to enhance spectral features [23].

Standard Procedure for Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy measurements often require careful optimization of parameters to maximize signal and minimize fluorescence.

- Step 1: Sample Preparation and Mounting. Raman spectroscopy generally requires minimal sample preparation. Solids, liquids, and powders can be analyzed directly. The sample is placed under the microscope objective or in a sampling compartment. For aqueous samples, Raman is advantageous as water is a weak scatterer [1].

- Step 2: Selection of Excitation Wavelength. The laser wavelength is a critical parameter. While visible lasers (e.g., 532 nm) offer high Raman scattering efficiency, they often induce fluorescence in organic samples. Near-infrared lasers (e.g., 785 nm) are widely used to mitigate this problem, as their lower energy is less likely to cause electronic excitation and subsequent fluorescence [1] [22].

- Step 3: Spectral Acquisition. The laser is focused onto the sample. The scattered light is collected and first passes through a notch or edge filter to block the elastically scattered Rayleigh light. The remaining Raman-shifted light is dispersed by a grating onto a CCD detector. Acquisition times can vary from seconds to minutes, depending on the sample and laser power [24].

- Step 4: Data Processing. The resulting spectrum is processed to remove cosmic rays, apply a calibration, and may include baseline correction to subtract any broad fluorescent background [24].

The workflow for both techniques is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Vibrational Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals (Diamond, ZnSe) | Enables Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) measurement in FTIR by generating an evanescent wave for surface analysis with minimal sample prep [23]. | Diamond is robust but expensive. ZnSe is common for general use but can be attacked by acids. Critical for analyzing aqueous biological samples [23]. |

| IR-Transparent Substrates (BaF₂, CaF₂, Low-E Slides) | Windows for transmission IR measurements. Low-E (low-emissivity) slides are used for transflection measurements, a common mode for tissue analysis [23]. | BaF₂ is water-soluble; CaF₂ is not. Low-E slides are inexpensive but can produce electric field standing wave artifacts that require computational correction [23]. |

| Notch/Edge Filters | Optical filters placed in the Raman collection path to block the intense elastically scattered laser light (Rayleigh scatter) while transmitting the weaker Raman signal [24]. | Essential for detecting the weak Raman signal. The performance of these filters directly impacts the ability to measure low-frequency Raman shifts close to the laser line. |

| Cooled CCD Detectors | The standard detector for Raman spectroscopy. Cooling (e.g., with Peltier or liquid N₂) drastically reduces dark current and readout noise, enabling long exposures for weak signals [24]. | Crucial for achieving a high signal-to-noise ratio in Raman measurements, especially when signal levels are low, such as with biological samples or low laser power. |

| MCT Detectors | A high-sensitivity semiconductor detector for FTIR spectroscopy. Must be cooled with liquid nitrogen for optimal performance [23]. | Offers much higher sensitivity and speed compared to the more common DTGS detector. Ideal for fast imaging or analyzing very small or dilute samples. |

Raman and IR spectroscopy, while both targeting molecular vibrations, are instrumentally distinct techniques that offer complementary information. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority, but of application-specific suitability. IR spectroscopy, with its simpler operation and generally higher sensitivity, is often the first choice for identifying functional groups and analyzing dry or non-aqueous samples. Its instrumentation, particularly with the widespread adoption of FTIR and ATR accessories, is highly standardized and robust. Raman spectroscopy excels where IR faces challenges, particularly in the analysis of aqueous solutions, through glass containers, or when low-frequency vibrations are of interest. However, its instrumentation is more complex, requiring careful selection of laser wavelength and advanced filtering to manage fluorescence and detect its inherently weak signal. For researchers in drug development and material science, understanding the core components and operational principles of these tools is fundamental to selecting the correct technique, designing valid experiments, and accurately interpreting the rich chemical information contained within vibrational spectra.

Practical Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis

In the realm of drug discovery and development, ensuring the stability and structural integrity of therapeutic proteins is paramount. These biological drugs, used to treat conditions from cancer to autoimmune diseases, are significantly less stable than traditional small-molecule pharmaceuticals [25]. Vibrational spectroscopy, which encompasses both Raman and Infrared (IR) techniques, provides a powerful, label-free approach for analyzing protein structure and monitoring stability under various conditions, such as the stressful lyophilization (freeze-drying) process used to create solid dosage forms [25] [22]. This guide offers a comparative analysis of these two techniques, framing them within the broader context of analytical tools available to researchers and scientists for ensuring the quality, efficacy, and safety of biologic drug products.

Fundamental Principles and a Direct Comparison

Physical Mechanisms and Molecular Sensitivity

The fundamental difference between Raman and IR spectroscopy lies in their underlying physical mechanisms, which dictate the molecular information they provide.

Infrared Spectroscopy measures the absorption of light when the energy of the incident IR photon matches the energy required to excite a molecular bond to a higher vibrational state. For a vibration to be IR-active, it must result in a change in the dipole moment of the molecule [22] [26]. This makes IR highly sensitive to polar functional groups, such as C=O, N-H, and O-H, which is why water (with its strong O-H stretching) creates a significant interference [22].

Raman Spectroscopy is based on an inelastic scattering process. When monochromatic light (usually a laser) interacts with a molecule, a tiny fraction of photons are scattered at energies different from the incident light. This energy shift corresponds to the vibrational energy levels of the molecular bonds. For a vibration to be Raman-active, it must involve a change in the polarizability of the electron cloud around the bond [22] [26]. This makes Raman particularly effective for probing non-polar covalent bonds, such as C-C, C=C, and S-S, which are common in protein backbones and disulfide bridges [26].

Comparative Analysis: Raman vs. Infrared Spectroscopy

The table below summarizes the key operational characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each technique, particularly in the context of protein analysis.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of Raman and Infrared spectroscopy for protein analysis.

| Feature | Raman Spectroscopy | Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Basis | Inelastic light scattering; change in polarizability [26] | Absorption of light; change in dipole moment [26] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; suitable for aqueous solutions and solids; can use glass containers [25] | Constrained; requires careful control of path length (<10 µm); dehydration often needed for aqueous samples [25] [22] |

| Water Compatibility | Excellent; weak water scattering signal [25] | Poor; strong water absorption obscures protein signals [25] [22] |

| Key Advantages | - Probes hydrophobic regions & S-S bridges [27]- Minimal sample prep [25]- Suitable for aqueous and solid-state analysis [25] | - Rapid measurement [25]- Strong signal for polar groups (C=O, N-H) [22]- Can be used pre- and post-lyophilization [25] |

| Key Limitations | - Fluorescence interference can mask signals [25] [26]- Laser can cause local heating/sample damage [25]- Slower data acquisition (spontaneous Raman) [28] | - Strong water interference [22]- Limited ability to predict solid-state degradation [25]- Only measures global conformation, not tertiary structure [25] |

| Spatial Resolution | High (confocal microscopy possible) | Lower than Raman |

Experimental Protocols for Protein Stability

Combined DLS-Raman Protocol for Unfolding and Aggregation

A powerful approach for studying protein stability involves integrating Raman spectroscopy with Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS). This combination provides simultaneous insights into colloidal stability (size and aggregation via DLS) and conformational stability (structural changes via Raman) from a single sample [27].

Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for a combined DLS-Raman experiment.

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Spectrometer System | Integrated system like Zetasizer Helix, combining a Raman spectrometer and a DLS instrument [27]. |

| Protein Sample | Therapeutic protein (e.g., Lysozyme, Bovine Serum Albumin) at concentrations typically from 0.1 mg/mL to 100 mg/mL [27]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Controlled pH buffers (e.g., citrate buffer) to study pH-dependent stability [27]. |

| Quartz Cuvette | Low-volume cuvette (e.g., 3 mm pathlength, ~120 µL) with high transmission for UV-Vis and Raman signals [27]. |

| Temperature Controller | Precision temperature control unit (e.g., 0°C to 90°C ± 0.1°C) for thermal ramp and isothermal studies [27]. |

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare formulations of the target protein (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin) at a specific concentration (e.g., 50 mg/mL) in buffers of varying pH [27].

- Loading: Introduce a ~120 µL aliquot of the sample into a quartz cuvette placed in the temperature-controlled compartment of the instrument [27].

- Thermal Ramp Experiment:

- Set the instrument to collect both DLS and Raman data at predefined temperature increments.

- DLS Data: Monitors the Z-average hydrodynamic radius, polydispersity index (PDI), and size distribution. An increase in these parameters indicates the onset of aggregation (Tonset) [27].

- Raman Data: Collects spectra using a 785 nm excitation laser. Monitor specific spectral markers:

- Secondary Structure: Amide I band (1600-1700 cm⁻¹), Amide III band (1200-1350 cm⁻¹) [27].

- Tertiary Structure: Vibrational modes of aromatic side chains (Tryptophan, Tyrosine) around 850 cm⁻¹ and 1550 cm⁻¹. Shifts here indicate changes in the hydrophobic environment, characteristic of unfolding [27].

- Isothermal Incubation Experiment:

- Collect baseline DLS and Raman data at a low temperature.

- Rapidly increase the temperature to just below the melting temperature (Tm) and collect data over a long period (e.g., 7-8 hours) to monitor slow unfolding and aggregation kinetics [27].

- Data Analysis: Correlate the temporal changes in protein size (from DLS) with the structural changes (from Raman) to elucidate the unfolding and aggregation pathway [27].

The workflow below visualizes the structure of this integrated experimental approach.

Key Experimental Data and Interpretation

The combination of DLS and Raman provides a multifaceted view of protein behavior. For instance, in a study of BSA at different pH levels:

- At pH 7.1: Raman spectroscopy showed significant changes in the Amide I band, while DLS showed a concurrent increase in hydrodynamic radius. This close tracking indicates that structural unfolding results in a larger monomer before significant aggregation occurs [27].

- At pH 5.4 (near the isoelectric point, pI): Raman showed minimal structural changes, but DLS detected large size increases (>500 nm). This suggests that at pI, where charge repulsion is minimized, aggregates form freely without major unfolding, a pathway that would be missed by using either technique alone [27].

Advanced Techniques and Clinical Translation

Overcoming Limitations with Advanced Raman

Traditional spontaneous Raman spectroscopy has limitations, including slow imaging speed and low sensitivity (typical detection in the millimolar range) [28]. To address these, advanced techniques have been developed:

- Stimulated Raman Scattering (SRS) and Coherent Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering (CARS): These are forms of coherent Raman scattering (CRS) microscopy. They offer orders of magnitude faster imaging speeds than spontaneous Raman, enabling high-resolution, high-throughput chemical imaging of living cells and tissues. This is crucial for longitudinal tracking of drug uptake, distribution, and response within complex biological models like organoids [28]. SRS, in particular, is free from a non-resonant background, provides linear concentration quantification, and is highly compatible with biological imaging [28].

Comparison with Other Imaging Modalities

While vibrational imaging is powerful, it is one of several tools available. The table below compares it with other common molecular imaging modalities.

Table 3: Comparison of Raman/IR imaging with other key molecular imaging techniques.

| Modality | Key Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman/IR Imaging | Molecular vibrations [22] | Label-free, chemical specificity, simultaneous multi-analyte detection [22] [28] | Low sensitivity (Raman), water interference (IR), limited depth penetration [28] |

| Fluorescence Imaging | Light emission from excited fluorophores | Extremely high sensitivity (single molecule), high spatial/temporal resolution [28] | Requires labeling, which can alter drug properties; photobleaching [28] |

| Mass Spectrometry Imaging (MSI) | Ionization & mass detection of molecules | Unparalleled specificity & multiplex capability; can detect drugs, metabolites, lipids [28] | Destructive; complex sample prep; difficult 3D imaging; quantification challenges [28] |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Radio waves & magnetic fields on nuclei | Excellent soft-tissue contrast; deep penetration; non-invasive [22] | Low sensitivity; often requires contrast agents; low spatial resolution vs. optical [22] |

| Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) | Light absorption & ultrasound detection | Good depth penetration; combines optical contrast & ultrasound resolution [22] | Often requires exogenous contrast agents for molecular imaging [22] |

Raman and IR spectroscopy are complementary, powerful techniques for analyzing protein structure and stability in drug development. IR spectroscopy excels in rapidly assessing global secondary structure and is sensitive to polar bonds, while Raman spectroscopy offers superior compatibility with aqueous samples, minimal preparation, and provides unique insights into tertiary structure and hydrophobic domains. The combination of Raman with techniques like DLS delivers a more complete picture of protein behavior under stress. Furthermore, advanced forms of Raman, such as SRS microscopy, are overcoming historical limitations and opening new frontiers for label-free drug imaging in physiologically relevant, complex models. The choice between these techniques, or the decision to use them in concert, depends on the specific protein attribute of interest, the sample environment, and the desired throughput, underscoring their collective value in the scientist's toolkit for ensuring the development of stable and effective biopharmaceuticals.

Quality Control and Raw Material Identification

In the demanding environments of pharmaceutical development and manufacturing, the rapid and accurate identification of raw materials is a critical quality control (QC) checkpoint. Vibrational spectroscopy techniques, namely Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, have become cornerstone methods for this non-destructive analysis. Both techniques probe molecular vibrations to generate a unique "fingerprint" for a substance, allowing for the verification of a material's identity against a known standard [5] [26]. This is essential for ensuring that every batch of raw material entering the production process meets the required specifications, thereby safeguarding product efficacy and safety.

While both techniques serve the same fundamental purpose, their underlying principles and practical applications differ significantly. The choice between Raman and IR spectroscopy can impact the speed, cost, and success of QC protocols. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data, to help researchers and scientists select the most appropriate technique for their specific raw material identification needs.

Raman and IR spectroscopy are complementary vibrational techniques, but they operate on different physical principles. IR spectroscopy measures the absorption of infrared light by a molecule. For a vibration to be IR-active, it must cause a change in the molecule's dipole moment [26] [1]. This makes IR highly sensitive to polar functional groups like C=O, O-H, and N-H.

In contrast, Raman spectroscopy is a scattering technique. It involves irradiating a sample with monochromatic light (usually a laser) and detecting the inelastically scattered light. For a vibration to be Raman-active, there must be a change in the molecule's polarizability—that is, the ease with which its electron cloud can be distorted [26] [1]. This makes Raman particularly sensitive to homo-nuclear covalent bonds (e.g., C-C, C=C, S-S) and symmetric vibrations.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental energy transitions that differentiate these two techniques.

The table below provides a high-level summary of the core characteristics of each technique.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Raman and IR Spectroscopy

| Feature | Raman Spectroscopy | Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Phenomenon | Inelastic scattering of light [3] | Absorption of light [3] |

| Physical Principle | Change in molecular polarizability [26] [1] | Change in dipole moment [26] [1] |

| Sensitive to | Homo-nuclear bonds (C-C, C=C, S-S), symmetric vibrations [26] | Polar bonds (O-H, C=O, N-H), asymmetric vibrations [26] |

| Typical Spectrum | Sharp peaks on a flat background [3] | Broad absorbance bands [3] |

| Complementary Nature | Best for covalent bond characterization | Best for ionic and functional group characterization [3] |

Performance Comparison for Raw Material Identification

Selecting the right technique requires a practical understanding of its advantages and limitations in a QC setting. The following table summarizes the key performance metrics critical for raw material identification (RMID).

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Pharmaceutical RMID

| Parameter | Raman Spectroscopy | IR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | Minimal to none; can analyze through glass/plastic containers [29] [3] | Often required; constraints on sample thickness and uniformity [26] |

| Water Compatibility | Excellent (water is a weak scatterer) [3] [1] | Poor (strong absorption by water) [3] [1] |

| Fluorescence Interference | A significant problem; can obscure the Raman signal [29] [1] | Not an issue [26] [1] |

| Sensitivity | Generally less sensitive than IR; can require enhancement techniques (e.g., SERS) [3] | Generally more sensitive for most functional groups [1] |

| Quantitative LOD Example | ~1.0 wt% for chlorogenic acid in protein matrix [5] | ~0.75 wt% for chlorogenic acid in protein matrix [5] |

| Portability | Excellent; many robust handheld systems available [29] [30] | Good; handheld FTIR systems are available [3] |

| Cost | Higher (due to lasers and sensitive detectors) [3] | Lower [3] |

Key Experimental Findings

- Detection of Impurities: A 2025 study on monitoring chlorogenic acid in sunflower meal protein isolates demonstrated that while both techniques are viable, FTIR offered a slightly better limit of detection (LOD) of 0.75 wt% compared to Raman's LOD of 1.0 wt% [5]. This highlights IR's potential for superior sensitivity in certain quantitative applications.

- Portability and In-Situ Analysis: Portable Raman instruments have been successfully deployed for in-situ identification of raw materials in warehouses, testing samples directly through plastic bags or glass vials without any preparation [29]. This minimizes sampling error and increases operational efficiency.

- Material Variability and Fluorescence: A key challenge in Raman-based RMID is fluorescence, which can vary between different batches or vendors of the same material. For instance, microcrystalline cellulose (a weak Raman scatterer) can produce false negatives if the fluorescence background of a new batch differs from the reference library [29]. This necessitates robust library management and can sometimes be mitigated by using longer-wavelength lasers (e.g., 785 nm or 1064 nm) [29].

Experimental Protocols for RMID

This section outlines standardized methodologies for developing identification methods using both techniques, based on cited research.

Protocol for Raman Spectroscopy Identification

This protocol is adapted from studies on pharmaceutical raw materials and plant-based protein matrices [5] [29].

1. Sample Presentation:

- For powders, present the sample in a glass vial or a low-density polyethylene (LDPE) bag. The technique can often measure directly through the container wall [29].

- As an alternative, powders can be compacted into a tablet using a hydraulic press with low pressure (e.g., ~200 kPa) to form a uniform surface for analysis [5].

2. Instrument Setup:

- Laser Wavelength: Select an excitation wavelength to minimize fluorescence. A 785 nm laser is a common starting point for organic compounds. If fluorescence persists, a 1064 nm laser can be tested [29].

- Microscope Objective: Use a ×50 objective for a good balance of spatial resolution and light gathering [5].

- Signal Acquisition: Set an integration time (e.g., 10 ms to 10 s) and number of accumulations (e.g., 1 to 10) to achieve an adequate signal-to-noise ratio without damaging the sample. Laser power should be optimized to prevent sample degradation [5].

3. Data Collection & Analysis:

- Collect spectra from multiple points on the sample (e.g., a 10 × 10 grid mapping) to account for heterogeneity [5].

- Compare the unknown sample's spectrum against a validated reference spectral library using correlation algorithms. The match is typically reported as a "hit quality" or p-value [29].

Protocol for FTIR Spectroscopy Identification

This protocol is based on the analysis of chlorogenic acid and other pharmaceutical compounds [5] [31].

1. Sample Preparation (Transmission Mode):

- Grind approximately 1-2 mg of the sample with 100-150 mg of an infrared-transparent matrix, such as potassium bromide (KBr) [5].

- Use a hydraulic press to compress the mixture into a uniform, translucent pellet under pressure (e.g., ~200 kPa) [5].

2. Instrument Setup:

- Use a Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometer in transmission mode.

- Scan across the standard mid-infrared range (4,000–400 cm⁻¹) [5].

- Collect a background spectrum using a pure KBr pellet before analyzing the sample.

3. Data Collection & Analysis:

- Acquire the spectrum of the sample pellet.

- Preprocess the spectra (e.g., baseline correction, normalization) as needed.

- For identification, use chemometric tools like correlation, principal component analysis (PCA), or support vector machine (SVM) to compare the sample spectrum against a pre-built library [31].

The workflow below summarizes the key steps for both techniques, highlighting their differences in sample handling.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of spectroscopic RMID relies on a set of key materials and reagents. The following table details these essentials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic RMID

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) | An infrared-transparent matrix used to dilute samples for FTIR analysis to avoid signal saturation [5]. | Preparing pellets for transmission FTIR spectroscopy of solid raw materials [5]. |

| Chlorogenic Acid Standard | A high-purity chemical standard used for calibration and method development. | Quantifying phenolic compound impurities in plant-based protein sources like sunflower meal [5]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | A model protein used to create a simulated sample matrix for method development. | Preparing calibration curves for impurities (e.g., chlorogenic acid) in a protein-based raw material [5]. |

| Reference Materials | Certified raw materials (APIs, excipients) from qualified vendors. | Building and validating the spectral reference library for identity testing [29]. |

| Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) Bags/Glass Vials | Standardized containers that are largely transparent to Raman laser and NIR light. | Enabling non-destructive, in-situ analysis of samples without removing them from their packaging [29] [31]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) Software | A powerful chemometric tool for classifying complex spectral data. | Managing large-scale spectral libraries and ensuring model transferability between different instruments [31]. |

Both Raman and IR spectroscopy are powerful, non-destructive techniques that are firmly established in the modern QC laboratory for raw material identification. The choice is not a matter of which technique is universally superior, but which is more appropriate for the specific sample and application context.

- Choose Raman spectroscopy when dealing with aqueous samples, when minimal sample preparation is a priority, when analysis through packaging is required, and when targeting symmetric covalent bonds and lattice vibrations (e.g., polymorphism).

- Choose IR spectroscopy when cost is a primary concern, when analyzing non-aqueous samples, when fluorescence is anticipated to be a problem, and when high sensitivity to polar functional groups is needed.

For the most comprehensive material characterization, particularly when dealing with novel or complex substances, employing Raman and IR as complementary techniques provides the fullest picture of molecular structure and composition, ensuring the highest level of confidence in raw material quality [3] [1].

Process Analytical Technology (PAT) and Real-Time Bioprocess Monitoring

Process Analytical Technology (PAT) is a system for designing, analyzing, and controlling manufacturing through timely measurements of critical quality and performance attributes of raw and in-process materials. The goal is to ensure final product quality, with a focus on building quality into products rather than testing it in after production [19]. In biopharmaceutical manufacturing, where living cells are used to produce complex drugs, even small variations in process parameters like pH, temperature, or nutrient levels can significantly impact yield and product quality [32]. Real-time monitoring is therefore crucial for detecting process deviations early, allowing for prompt corrective actions and reducing the risk of costly batch failures [33].

Vibrational spectroscopy techniques, particularly Raman and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, have emerged as powerful PAT tools for providing molecular-level information about bioprocesses. Both techniques probe the vibrational energy levels of molecules, generating unique "molecular fingerprints" that can identify chemical composition and structure [19] [3]. However, their underlying physical principles and selection rules differ, making them complementary for various applications in real-time bioprocess monitoring. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Fundamental Principles and Selection Rules

The fundamental difference between the two techniques lies in their physical mechanisms. IR spectroscopy measures the direct absorption of infrared light by a molecule, which occurs when the radiation's frequency matches a natural vibrational frequency of the molecule and the vibration causes a change in the molecule's dipole moment [34] [1]. In contrast, Raman spectroscopy is a scattering technique. It involves irradiating a sample with a monochromatic laser and detecting the inelastically scattered light, which has shifted in energy due to interactions with molecular vibrations. A vibration is Raman active if it induces a change in the polarizability (the deformability) of the molecule's electron cloud [34] [1].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental principles and selection rules that govern whether a molecular vibration is active in IR or Raman spectroscopy.

For molecules with a center of symmetry (centrosymmetric), the Rule of Mutual Exclusion often applies. This rule states that no vibration can be both IR and Raman active; the vibrational modes are mutually exclusive [34]. This complementarity makes the techniques powerful when used together for full molecular characterization.

Technical Comparison: Raman vs. IR Spectroscopy

The different physical principles of Raman and IR spectroscopy lead to distinct practical advantages and limitations in a bioprocessing environment. The following table summarizes these key performance differentiators.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Raman and IR Spectroscopy for Bioprocess Monitoring

| Aspect | Raman Spectroscopy | Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light [3] | Absorption of infrared radiation [3] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; samples can be analyzed in glass vials or through sight glasses [3] | Often requires specific sampling accessories (e.g., ATR crystal); can be more involved [1] |