Resolving Isobaric Interferences and Managing Peak Broadening in Mass Spectrometry: Strategies for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of two fundamental challenges in mass spectrometry: isobaric interferences and peak broadening.

Resolving Isobaric Interferences and Managing Peak Broadening in Mass Spectrometry: Strategies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of two fundamental challenges in mass spectrometry: isobaric interferences and peak broadening. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational concepts of isobaric and isomeric interferences and their impact on data accuracy. The scope extends to modern methodological approaches for interference removal, including ICP-MS/MS with reactive gases and novel deconvolution algorithms. It also details practical troubleshooting and optimization techniques to minimize peak broadening and detect hidden interferences, concluding with rigorous validation strategies and a comparative analysis of available technologies to ensure analytical reliability in complex biomedical samples.

Understanding the Core Challenges: Defining Isobaric Interferences and Peak Broadening Mechanisms

Mass spectrometry (MS) is a cornerstone analytical technique across biochemistry, pharmacology, and omics research, capable of determining and quantifying compounds based on their mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) [1]. However, its formidable analytical power is routinely challenged by interferences that obscure accurate identification and quantification. These challenges are primarily categorized as isobaric and isomeric interferences. While both can co-elute and appear at the same nominal m/z, their fundamental origins and the strategies required to resolve them differ significantly. Isobaric interferences arise from distinct chemical entities with the same nominal mass, whereas isomeric interferences stem from molecules sharing an identical chemical formula and mass, but differing in their atomic connectivity or spatial arrangement [1] [2]. Within the context of mass spectra research, these interferences represent a form of molecular noise that can lead to peak broadening, composite spectral signatures, and ultimately, inaccurate biological or chemical conclusions if not properly addressed. This guide provides a comprehensive taxonomy of these challenges and outlines the advanced experimental methodologies employed to overcome them.

Defining the Fundamental Interference Types

Isobaric Interferences

Isobaric interferences occur when two or more different elemental ions or molecules share the same nominal mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), making them indistinguishable to a mass analyzer without additional separation techniques [3] [4]. This category can be further broken down into three principal subtypes, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: A Taxonomy of Isobaric Interferences in Mass Spectrometry

| Interference Type | Definition | Classic Example | Common Analytical Techniques for Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elemental Isobars | Different elements with isotopes of the same nominal mass [3] [4]. | ( ^{58}Fe^{+} ) and ( ^{58}Ni^{+} ) [3] | High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS), mathematical correction, alternative isotope selection [3] [4]. |

| Polyatomic Interferences | Molecular ions formed from the combination of two or more atoms from the plasma, solvent, or sample matrix [3] [4]. | ( ^{40}Ar^{35}Cl^{+} ) on monoisotopic ( ^{75}As^{+} ) [3] | Collision/reaction cells (KED), cool plasma, chromatographic separation, mathematical correction [3] [5]. |

| Doubly-Charged Ion Interferences | Elemental ions with a double charge (( z = 2 )), which are detected at half their true mass [4] [5]. | ( ^{136}Ba^{2+} ) interfering with ( ^{68}Zn^{+} ) [5] | Optimization of plasma conditions, selection of an alternative analyte isotope [4] [5]. |

The following diagram illustrates the primary origins and pathways leading to the major types of isobaric interferences.

Isomeric Interferences

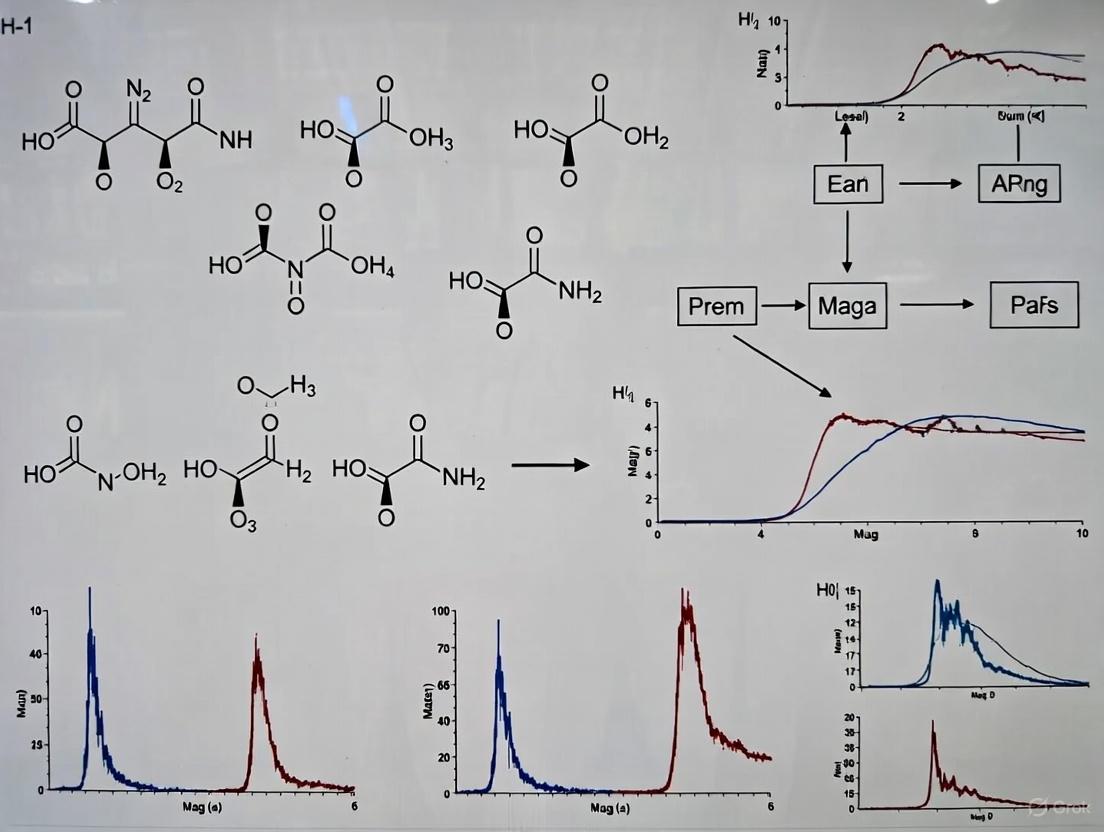

Isomeric interferences present a more subtle challenge. Here, the interfering species share the exact same chemical formula and molecular mass, but differ in their structural organization. This shared mass means they are intrinsically isobaric with each other, but the term "isomeric interference" specifically highlights the challenge of differentiating between structural variants. The hierarchy of isomerism is complex, and the main categories relevant to mass spectrometry are defined below and illustrated in the subsequent diagram [2].

- Constitutional Isomers (Structural Isomers): These share the same atoms and connectivity but differ in the arrangement of their atomic bonds. Key subtypes in lipidomics, for example, include:

- Regioisomers: Differing in the position of a functional group, such as the location of a carbon-carbon double bond (db-position) or the attachment site of fatty acyl chains on a glycerol backbone (sn-position) [2].

- Functional Group Isomers: Containing different functional groups.

- Stereoisomers: These share the same atomic connectivity but differ in the three-dimensional orientation of their atoms. This category includes:

The diagram below maps this hierarchy of isomerism.

Experimental Protocols for Interference Management

Protocol 1: Mathematical Correction for Isobaric Overlap

This protocol is a foundational strategy for managing well-characterized isobaric overlaps in techniques like ICP-MS [3].

1. Principle: By measuring the signal of an interference-free isotope of the interfering element, one can mathematically calculate and subtract its contribution from the signal at the overlapped mass [3].

2. Methodology: The following workflow outlines the sequential steps for applying a mathematical correction, using the example of correcting a ( ^{114}Sn ) interference on ( ^{114}Cd ) [3].

3. Calculation Example: The intensity of ( ^{114}Cd ) is derived as follows [3]: [ I(^{114}Cd) = I(m/z\ 114) - I(^{114}Sn) ] Where the intensity of ( ^{114}Sn ) is calculated from the measured intensity of ( ^{118}Sn ) and their known natural abundances (0.65% and 24.23%, respectively) [3]: [ I(^{114}Sn) = \frac{0.65}{24.23} \times I(^{118}Sn) \approx 0.0268 \times I(^{118}Sn) ] Thus, the final correction equation is [3]: [ I(^{114}Cd) = I(m/z\ 114) - 0.0268 \times I(^{118}Sn) ]

4. Limitations: This method can over-correct if no interference is present and may fail at very high interference-to-analyte ratios [3].

Protocol 2: Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry for Isomer Separation

For separating isomeric interferents, Ion Mobility Spectrometry (IMS) coupled to MS provides a powerful gas-phase separation dimension.

1. Principle: IMS separates ions based on their size, shape, and charge as they drift through a buffer gas under an influence of an electric field. The key measurand is the Collision Cross Section (CCS), a reproducible physicochemical descriptor that is sensitive to isomeric structure [2] [6].

2. Workflow: A typical IMS-MS workflow for lipid isomer separation involves multiple, orthogonal analytical steps, as shown below.

3. Key Steps:

- Separation: Ions are separated in the mobility cell. Compact ions (smaller CCS) traverse faster than extended ions (larger CCS) [6].

- CCS Measurement: The drift time is used to calculate the instrument-independent CCS value, which serves as a key identifier for database matching [2].

- Application Example: Cyclic IMS (CIMS) can achieve ultra-high resolution by passing ions through multiple cycles. One study resolved four fatty acid isomers (FA 18:1) differing in double-bond position and cis/trans geometry after 15 cycles, achieving a resolution of ~150, whereas a single pass yielded a single merged peak [6].

Advanced Instrumental Solutions and The Scientist's Toolkit

Modern mass spectrometry employs a sophisticated arsenal of technologies to manage interferences. The selection of a platform depends on the specific interference challenge and the required level of resolution.

Table 2: Key Instrumental Platforms for Resolving MS Interferences

| Platform / Technology | Primary Interference Target | Mechanism of Action | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrupole ICP-MS with Collision Cell (KED) | Polyatomic interferences [3] [5] | Uses a non-reactive gas (e.g., He) to cause polyatomic ions to lose more kinetic energy than atomic ions. An energy barrier filters out the slower polyatomics [3] [5]. | Abundance sensitivity (~10⁻⁶) [4] |

| Drift Tube IMS (DTIMS) | Isomeric and isobaric interferences [6] | Ions drift through a static electric field; drift time is directly proportional to CCS [6]. | Resolution: ~50 (single-pulse) to >200 (multiplexed) [6] |

| Cyclic IMS (CIMS) | Challenging isomeric mixtures [6] | Ions undergo multiple passes around a cyclic path, dramatically increasing path length and resolution [6]. | Tunable Resolution: ~60 to >750 (with 100 passes) [6] |

| Trapped IMS (TIMS) | Isomeric and isobaric interferences [6] | Ions are held in place by electric fields and gas flow, then eluted by mobility; enables very compact designs [6]. | High resolution in a compact form factor |

| Gas-Phase Ion/Ion Reactions | Isobaric lipids and positional isomers [7] | Uses reactions (e.g., charge inversion) to selectively transform analyte ion type, changing m/z and enabling separation and diagnostic fragmentation [7]. | Specificity for lipid classes (e.g., PCs, PSs) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Interference Resolution

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1,4-phenylenedipropionic acid (PDPA) dianion | Charge inversion reagent for selective reaction with phosphatidylcholine (PC) cations, converting them to anions for improved MS/MS analysis and isobaric separation [7]. | Imaging MS of lipids [7] |

| Helium (He) Gas | Non-reactive collision gas for Kinetic Energy Discrimination (KED) to suppress polyatomic interferences in ICP-MS [3] [5]. | ICP-MS collision cells [3] |

| Metal Ion Adducts (e.g., Na⁺) | Adduction with lipids to amplify drift time differences between isomers, enhancing separation in IMS [6]. | Ion Mobility-MS [6] |

| Derivatization Reagents | Chemically modify lipids (e.g., via esterification) to enhance mobility separation or induce diagnostic fragmentation [2] [6]. | LC- or IMS-MS Lipidomics [2] |

| 1,5-diaminonapthalene (DAN) | A matrix for Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) to facilitate the analysis of lipids and other analytes from tissue surfaces [7]. | Imaging Mass Spectrometry [7] |

Fundamental Causes and Consequences of Peak Broadening in Chromatographic Systems

In chromatographic systems, peak broadening describes the physical spreading of a compound's band as it migrates through the separation system. This phenomenon is one of the most critical occurrences in chromatography, directly determining the efficiency and resolving power of the analytical method [8]. Ideal chromatographic systems would produce peaks that resemble straight-line spikes with no broadening, but in practice, various physical and chemical processes cause predictable spreading of analyte bands [8]. The extent of broadening determines how many peaks can be separated within a given time window (peak capacity) and whether closely eluting compounds can be distinguished from one another [9]. For researchers investigating complex samples, particularly in drug development where isobaric compounds present significant challenges, understanding and controlling peak broadening is essential for obtaining reliable, high-quality data.

The following diagram illustrates the core concepts of peak broadening and its impact on separation efficiency:

Fundamental Causes of Peak Broadening

Column-Based Broadening Mechanisms

Within the chromatographic column, four primary processes contribute to peak broadening. The van Deemter equation, first described by J. J. van Deemter in 1956, mathematically relates these contributions to the reduced plate height, which serves as a key metric for column efficiency [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Column-Based Broadening Mechanisms [8]

| Mechanism | Physical Basis | Flow Rate Dependence | Impact on Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Longitudinal Diffusion | Molecular diffusion along the column axis | Decreases with increasing flow rate | Significant at low flow rates |

| Eddy Diffusion | Multiple flow paths through packing material | Independent of flow rate | Major contributor in poorly packed columns |

| Mass Transport in Stationary Phase | Time required for adsorption/desorption | Increases with flow rate | Dominant for strongly retained analytes |

| Mass Transport in Mobile Phase | Resistance to mass transfer in mobile phase | Increases with flow rate | Significant in columns with large particles |

Extra-Column Effects

Extra-column dispersion refers to peak broadening that occurs outside the separation column, in components such as injection systems, connecting tubing, and detector flow cells [10]. This type of broadening has gained renewed importance with the trend toward smaller column dimensions and particle sizes in modern UHPLC systems, where peak volumes can be extremely small (on the order of 10 times less than in conventional HPLC) [10]. The impact is particularly devastating for narrower columns (2.1 mm i.d.) packed with smaller particles (sub-3μm), where extracolumn variance can reduce resolution by 23% or more [10].

The mathematical treatment of extracolumn effects recognizes that peak variances are additive, not the peak widths themselves. The observed variance (σ²_obs) is calculated as:

σ²obs = σ²column + σ²_EC

Where σ²column is the intrinsic column variance and σ²EC is the extracolumn variance [10].

Thermodynamic and Kinetic Contributions

Peak broadening originates from different sources depending on operating conditions. Under linear (analytical) conditions, broadening is primarily due to kinetics—how fast molecules interact with the stationary phase. In nonlinear (preparative) conditions, broadening is governed by thermodynamics—mainly the strength and saturation behavior of the adsorption process [11].

Thermodynamic heterogeneity causes tailing when strong binding sites become saturated, while kinetic heterogeneity causes tailing when some sites have slower exchange rates. A simple test to distinguish these causes involves varying flow rates and sample concentrations: if tailing decreases at lower flow rates, the origin is kinetic; if tailing decreases at lower sample concentrations, the cause is thermodynamic [11].

Quantitative Analysis of Peak Broadening

Measures of Peak Shape and Efficiency

Several mathematical approaches exist for quantifying peak broadening, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Peak Shape Measurement Techniques [9]

| Method | Calculation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Plates (N) | N = (tᵣ/W)² × a | Simple, widely used | Assumes Gaussian shape; overestimates efficiency |

| USP Tailing Factor (T) | T = W₀.₀₅/2f | Regulatory standard; simple | Single value; misses fronting |

| Asymmetry Factor (Aₛ) | Aₛ = b/a | More precise than T | Single value; misses complexity |

| Statistical Moments | m₂ = ∫(t-tₘ)²S(t)dt / ∫S(t)dt | Model-independent; accurate | Noise-sensitive; requires high S/N |

| Derivative Test | dS/dt = (S₂-S₁)/Δt | Reveals full shape complexity | Requires high sampling rate |

The moment-based calculation of efficiency does not assume any peak shape and can be determined for any peak shape encountered in chromatography (fronting, tailing, split, shouldering, horned, etc.) [9]. However, moments are very sensitive to the determination of peak start (t₁) and peak end (t₂), and to noise in the signal S(t) [9].

Advanced Shape Analysis: Total Peak Shape Analysis

The "Total Peak Shape Analysis" approach facilitates detection and quantification of concurrent fronting and tailing in peaks that single-value descriptors might miss [9]. This is particularly valuable for characterizing "Eiffel Tower" peaks that exhibit both fronting and tailing attributes, which are common in chiral separations [9].

The derivative test provides the most straightforward approach to assess total symmetry and peak shapes. For a chromatographic signal S, the derivative is:

dS/dt = (S₂ - S₁)/Δt

Where Δt is the sampling interval [9]. This test requires a high sampling rate (80 Hz and above), low response time settings (<0.1 s), and a high signal-to-noise ratio [9]. When the derivative of a pure Gaussian peak is plotted, the maximum and minimum values are identical. If a peak has a slight tail, the left maximum has a larger absolute value than the right minimum, quantitatively revealing the asymmetry [9].

Consequences for Analytical Science and Drug Development

Impact on Resolution and Peak Capacity

The practical consequence of peak broadening is directly observed in the chromatogram's resolving power. As peaks broaden, the ability to distinguish between closely eluting compounds diminishes, potentially leading to co-elution and misidentification [8] [10]. This is particularly problematic when analyzing complex mixtures such as metabolic samples or protein digests, where dozens or hundreds of components must be separated.

The relationship between efficiency (N), retention factor (k), and selectivity (α) is captured by the fundamental resolution equation:

Rₛ = (√N/4) × [(α-1)/α] × [k/(1+k)]

This equation demonstrates that resolution is directly proportional to the square root of efficiency (N), making peak broadening control essential for achieving adequate separation [8].

Implications for Mass Spectrometric Analysis

In the context of mass spectrometric research, particularly regarding isobaric interferences, chromatographic peak broadening has significant implications for accurate compound identification. When chromatographic peaks broaden, the likelihood of co-elution of isobaric compounds increases substantially, leading to chimeric MS2 spectra where fragments from multiple precursors interfere with each other [12].

This problem is especially acute in direct infusion mass spectrometry, where the absence of chromatographic separation makes spectral deconvolution challenging [12]. The IQAROS (incremental quadrupole acquisition to resolve overlapping spectra) method has been developed specifically to address this issue by modulating precursor intensities through stepwise movement of the quadrupole isolation window, followed by mathematical deconvolution [12].

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Peak Broadening

Measuring Extracolumn Dispersion

Protocol Objective: Quantify the contribution of instrument components to total peak broadening [10].

Materials and Equipment:

- HPLC/UHPLC system with autosampler, column thermostat, and detector

- Zero-dead-volume union

- Standard analyte solution (appropriate for detection)

- Data acquisition software with peak width measurement capability

Procedure:

- Remove the chromatographic column and replace with a zero-dead-volume union

- Inject the standard solution using typical method parameters

- Measure the peak width of the resulting "system peak"

- Calculate variance using the relationship: σ² = (w₀.₅/2.355)² for Gaussian peaks

- Alternatively, use statistical moments for more accurate variance calculation of asymmetric peaks

Data Interpretation: The measured variance represents the minimum broadening contribution from the instrument itself. This value should be compared to the expected column variance to determine if the instrument is appropriate for the chosen column configuration [10].

Column Efficiency Testing Protocol

Protocol Objective: Determine the intrinsic efficiency of a chromatographic column independent of instrument contributions.

Materials and Equipment:

- Test column and reference columns (if available)

- Mobile phase appropriate for the column chemistry

- Standard analytes with low molecular weight (e.g., uracil, alkylphenones)

- Data system capable of moment calculations

Procedure:

- Condition the column according to manufacturer specifications

- Inject the standard solution and record the chromatogram

- Measure retention time and peak width at multiple heights (10%, 50%, 4.4%)

- Calculate efficiency using both Gaussian (N = (tᵣ/W)² × a) and moment-based equations

- Compare results from different calculation methods

Data Interpretation: Significant discrepancies between Gaussian and moment-based efficiency calculations indicate non-ideal peak shapes that may require further investigation [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Peak Broadening Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Zero-Dead-Volume Unions | Replace column for extracolumn measurements | Must be truly "zero" volume; use manufacturer-supplied unions |

| Isobaric Standard Mixtures | Model compounds for interference studies | Benzothiazole, adenine, acetanilide effectively demonstrate co-fragmentation [12] |

| Stationary Phase Evaluation Kits | Test different column chemistries | Include various pore sizes, surface areas, and bonding chemistries |

| High-Purity Mobile Phase Additives | Modify selectivity and peak shape | Formic acid, ammonium acetate, ion-pairing reagents [11] |

| Characterized Column Packings | Investigate fundamental broadening mechanisms | Materials with controlled pore architecture [13] |

Emerging Trends and Advanced Concepts

Gradient Stationary Phase Technology

Recent investigations into pore size gradient SEC columns demonstrate innovative approaches to managing peak broadening while extending separation range [13]. These columns feature stationary phase properties that change gradually along the column length, offering a unique compromise between selectivity and efficiency [13]. Theoretical modeling confirms that peak widths on gradient columns remain similar to those of uniform columns, while providing enhanced selectivity across broad analyte size ranges [13].

Adsorption Energy Distribution Analysis

The concept of Adsorption Energy Distribution (AED) provides a generalized tool that reveals how adsorption energies are distributed across a chromatographic surface [11]. Rather than assuming one or two distinct types of adsorption sites, AED shows the full spectrum of binding strengths, giving a detailed energetic "fingerprint" of the surface [11]. This approach is particularly useful for identifying heterogeneity in adsorption behavior that contributes to peak tailing and broadening.

Biosensor-Informed Chromatography

Research combining biosensor platforms (such as surface plasmon resonance) with chromatographic studies has provided new insights into the molecular interaction kinetics that contribute to peak broadening [11]. Biosensors allow direct observation of binding and dissociation in real time, enabling researchers to identify true kinetic limitations that contribute to peak tailing and asymmetry [11].

Within the framework of a broader thesis on isobaric interferences and peak broadening in mass spectrometry, this technical guide examines the profound consequences these phenomena have on data integrity. Mass spectrometry, a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, proteomics, and metabolomics, relies on the precise measurement of ion mass-to-charge ratios. However, the integrity of this data is systematically challenged by isobaric interferences, where different molecules share nearly identical mass-to-charge ratios, and by chromatographic peak broadening, which reduces the ability to separate these interferences. These technical issues directly manifest as false positives in identification, inaccurate relative quantification, and compromised detection limits, ultimately jeopardizing scientific conclusions and decision-making in fields like drug development. This document provides an in-depth analysis of the mechanisms, quantitative impacts, and methodological solutions to these critical problems, providing researchers with the knowledge to safeguard their data's accuracy.

Fundamental Concepts and Mechanisms

The Nature of Isobaric Interferences

Isobaric interferences occur when an signal from an unintended molecule is indistinguishable from the target analyte within the mass resolution of the instrument. These can be categorized as follows:

- Chemical Isobars: Different elemental or molecular compositions with the same nominal mass (e.g., CO⁺ and N₂⁺ in ICP-MS).

- Isotopic Overlap: Natural abundance of heavy isotopes (e.g., ¹³C) in one molecule contributing to the signal of a heavier analyte [14].

- In-Source Fragmentation: Neutral losses or fragmentation in the ion source that generate product ions identical to those monitored for another compound [15].

- Isobaric Labeling Interference: In proteomics, co-isolation and co-fragmentation of multiple peptides labeled with isobaric tags (e.g., TMT, iTRAQ) lead to distorted reporter ion ratios, a phenomenon known as "ratio compression" [16].

Chromatographic Peak Broadening

Peak broadening describes the dilution of a compound's concentration as it passes through a chromatography column, leading to wider, lower-intensity peaks. A primary cause is the presence of "rare adsorption sites" on the stationary phase that have different kinetic characteristics compared to the majority sites. Recent research demonstrates that the spatial clustering of these slow sites exacerbates peak broadening and tailing, an effect that remains significant even when considering other diffusion processes [17]. This broadening increases the likelihood that peaks from interfering species will co-elute with the target analyte, thereby compounding the challenges of mass-based separation.

Quantitative Impact on Data Integrity

The theoretical risks of interference materialize into measurable data quality issues. The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent experimental investigations.

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Interference on Data Integrity

| Analytical Domain | Documented Impact | Experimental Basis | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Metabolomics (LC-MS/MS) | ~75% of metabolites generated measurable signals in at least one other metabolite's MRM setting. | Analysis of 334 metabolite standards on a triple-quadrupole MS. | [15] |

| Targeted Metabolomics (LC-MS/MS) | ~10% of ~180 annotated metabolites in biological samples were mis-annotated or mis-quantified. | Analysis of cell lysate and serum samples combined with manual inspection. | [15] |

| Proteomics (Isobaric Labeling) | >30% of tandem mass spectra were contaminated with additional peptide-derived precursor peaks. | MudPIT proteomic experiment estimating co-isolation interference. | [16] |

| Proteomics (Isobaric Labeling) | Signal from contamination represented ~40% of total ion signal intensity on average. | MudPIT proteomic experiment estimating co-isolation interference. | [16] |

| Lipidomics (High-Resolution MS) | Concentrations of lipid species affected by isobaric overlap were more accurate when calculated from the first isotopic peak (M+1) rather than the monoisotopic peak (M). | Spike experiments with lipid species pairs of various lipid classes analyzed by flow injection analysis-FTMS. | [14] |

Detailed Experimental Methodologies

Protocol for Identifying Metabolite Interference in Targeted Metabolomics

The following protocol, adapted from a 2023 study, provides a robust method for systematically characterizing metabolite interference [15].

Step 1: Standard Preparation and LC-MS/MS Analysis

- Reagents: Prepare solutions of 334 metabolite standards, purchased from commercial suppliers (e.g., Selleck Inc.), in DMSO or water at concentrations of 10 mM or 2 mM. Divide standards into logical groups.

- Chromatography: Perform liquid chromatography using a HILIC column (e.g., iHILIC-(P) Classic column) with mobile phases of 20 mM ammonium acetate/0.1% ammonium hydroxide in 95:5 water/ACN (A) and ACN (B). Use a gradient from 85% B to 35% B over 12 minutes.

- Mass Spectrometry: Utilize a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (e.g., QTRAP 6500+) in MRM mode. Acquire data for all MRM transitions for all standards in a single method to collect a comprehensive interference dataset.

Step 2: Data Processing and Peak Identification

- Convert raw LC-MS/MS files to mzML format using MSConvert (ProteoWizard).

- Process mzML files with the

xcmsR package for peak identification and peak table generation.

Step 3: Interfering Metabolite Pair (IntMP) Analysis

- For all combinatorial metabolite pairs, check if the standard of a potential "interfering metabolite" generates a chromatographic peak in the MRM transition of a potential "anchor metabolite."

- Filter these pairs by examining whether the interfering metabolite's MS2 spectrum includes the anchor metabolite's precursor (Q1) and product (Q3) ions.

- Calculate the transition ratio (intensity in anchor's MRM / intensity in its own MRM) and the cosine similarity of the peak shapes.

- Define an Interfering Metabolite Pair (IntMP) if: the Q1 and Q3 exist in the interfering metabolite's MS2; cosine similarity > 0.8; and transition ratio ≥ 0.001.

Step 4: LC-Specific IntMP and Biological Sample Analysis

- For a specific LC method, apply retention time constraints (e.g., RT difference < 0.5 min) and calculate an interference ratio (signal from interfering metabolite / signal from anchor metabolite under the anchor's MRM). A ratio above 0.005 indicates a practically relevant interference.

- In biological samples, screen annotated peaks against the LC-specific IntMP list. A peak is considered interfered with if the transition ratio in the sample is within 0.1 to 10-fold of the ratio observed in the standard.

Protocol for Improving Quantitation in Isobaric-Labeling Proteomics

This protocol integrates spectral library searching and a feature-based filter to enhance quantitation accuracy, as demonstrated in a 2023 study [18].

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Reagents: Use isobaric labeling tags (e.g., TMT or iTRAQ) according to manufacturer protocols. For absolute bioavailability studies, use stable isotopically labeled (SIL) drugs with ¹³C or ¹⁵N labels, avoiding deuterium to prevent kinetic isotope effects [19].

- Mass Spectrometry: Acquire data on an instrument capable of high-resolution MS/MS (e.g., Orbitrap). Use HCD fragmentation for reporter ion generation.

Step 2: Sequence Database Searching and Spectral Library Construction

- Search mzML/mzXML files against a protein sequence database using search engines like Comet and X!Tandem.

- Validate results with PeptideProphet and combine them using iProphet (within the Trans-Proteomic Pipeline) to obtain statistically validated PSMs at a 1% FDR.

- Construct a sample-specific spectral library from these validated PSMs using SpectraST.

Step 3: Combined Database and Spectral Library (DB+SL) Searching

- Re-search the experimental data against the newly built spectral library using SpectraST.

- Combine the results from the initial database search and the spectral library search using iProphet. This combined output (DB+SL) typically yields a larger set of PSMs for quantitation.

Step 4: Application of the Feature-Based PSM Filter (FPF)

- The FPF tool is used to remove PSMs with larger quantitation errors.

- The filter examines various spectral features correlated with quantitation accuracy, such as:

- Peptide Length

- Charge State

- Average Reporter Ion Intensity

- Signal-to-Interference (S2I) measure (abundance of a precursor and its isotopic clusters divided by the sum of all ion signals in the isolation window). PSMs with S2I < 0.7 are typically removed [18].

- The PSMs retained after this filtering process are used for downstream quantitation, leading to improved accuracy at the peptide and protein levels.

Diagram 1: Enhanced Proteomics Workflow for Mitigating Interference.

Advanced Strategies for Interference Mitigation

Computational and Machine Learning Approaches

Advanced computational methods are proving highly effective in identifying and correcting for interferences.

- Dynamic Binning for Peak Detection: Traditional peak detection uses a fixed mass tolerance, which can lead to missed peaks or duplicates. The dynamic binning method sets the peak detection mass tolerance dynamically as a function of m/z, proportional to (m/z)² for FTICR, (m/z)¹.⁵ for Orbitrap, and m/z for Q-TOF instruments. Implementation in tools like XCMS has been shown to significantly improve quantification performance [20].

- Machine Learning to Identify Unreliable Spectra: For isobaric labeling data, the IQUP method uses machine learning to classify Peptide-Spectrum Matches (PSMs) as Quantitatively Unreliable (QUP) or Reliable (QRP). IQUP uses 16 spectral and distance-based features (e.g., peptide length, charge state, reporter ion intensity) to train models that can identify QUPs with high accuracy (0.883–0.966) [21]. Removing QUPs before quantitation significantly decreases the proportion of peptides with large relative errors.

Strategic Use of Stable Isotope Labels

In LC-MS/MS bioanalysis, particularly for microdose absolute bioavailability studies, strategic use of SIL compounds is critical.

- Overcoming Interference by Monitoring Less Abundant Ions: When isotopic interference exists between an unlabeled drug and its SIL analog, a cost-effective strategy is to monitor a less abundant isotopic ion of the SIL drug (e.g., M+1 or M+2) instead of its monoisotopic ion (M). This reduces the apparent interference from the unlabeled drug's isotopic envelope without requiring the synthesis of a more heavily labeled molecule [19].

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Metabolite Standards | For creating interference maps in targeted metabolomics. | Should be a comprehensive set (e.g., 334+ standards) divided into non-interfering groups for analysis [15]. |

| Isobaric Labels (TMT, iTRAQ) | Enable multiplexed, relative protein quantitation. | Prone to ratio compression from co-isolated peptides; requires advanced methods like MS3 or spectral library searching for accuracy [18]. |

| Stable Isotopically Labeled (SIL) Drugs | Used as internal standards or as microtracers in absolute bioavailability studies. | Prefer ¹³C/¹⁵N labels over deuterium to avoid chromatographic isotope effects [19]. |

| HILIC Chromatography Column | Separates polar metabolites in targeted metabolomics. | Different column chemistries (e.g., iHILIC-(P) vs. XBridge Amide) can resolve 65-85% of interfering signals [15]. |

| Spectral Library Software (SpectraST) | Constructs and searches libraries of experimental spectra. | Improves identification sensitivity and, when combined with filtering, enhances quantitation accuracy in proteomics [18]. |

Diagram 2: Decision Workflow for Interference Mitigation Strategies.

The integrity of mass spectrometry data is perpetually under threat from isobaric interferences and peak broadening, leading directly to false positives, inaccurate quantification, and compromised detection limits. The quantitative evidence is clear: a significant proportion of metabolites and peptides are susceptible to mis-identification or mis-quantification. Addressing these challenges requires a move beyond standard workflows. The integration of experimental strategies—such as comprehensive interference mapping with standards, optimized chromatography, and clever use of stable isotopes—with advanced computational approaches—like dynamic binning for peak detection and machine learning for filtering unreliable data—provides a robust defense. By understanding the mechanisms and implementing these detailed protocols and strategies, researchers can significantly improve data quality, ensuring that conclusions in basic research and decisions in critical applications like drug development are built upon a foundation of reliable analytical data.

Mass spectrometry has become a cornerstone technique in drug development for the quantitative analysis of drugs and their metabolites in biological matrices. However, the accuracy of these analyses is consistently challenged by analytical interferences, particularly those arising from the drug's own metabolites. Isobaric interferences and chromatographic peak broadening represent two significant classes of challenges that can compromise data integrity, leading to inaccurate pharmacokinetic and toxicological assessments [22] [23].

This technical guide explores these interferences within the context of a broader thesis on advanced mass spectrometric research. It provides an in-depth examination of the mechanisms through which metabolites cause analytical interference, presents quantitative data on their impact, details methodologies for their identification and mitigation, and proposes a standardized toolkit for researchers. By integrating specific case studies and experimental protocols, this whitepaper serves as an essential resource for scientists and drug development professionals dedicated to ensuring data accuracy and reliability.

Understanding Isobaric Metabolite Interferences

Isobaric metabolite interferences occur when a metabolite shares the same nominal mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) as the parent drug or other analytes, leading to erroneous quantification [22]. Unlike simple matrix effects, these interferences are drug-specific and arise from the biotransformation of the drug molecule itself.

Mechanisms and Case Studies

Two primary mechanisms can lead to such interferences, illustrated by the following case studies:

Case Study 1: Formation of an Isobaric Metabolite via Sequential Metabolism. A drug molecule underwent sequential metabolic reactions: initial demethylation followed by oxidation of a primary alcohol to a carboxylic acid. This two-step process resulted in a metabolite that was isobaric with the parent drug. Consequently, this metabolite produced an identical multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transition. In a 12-minute liquid chromatography (LC) method, the metabolite eluted at a retention time very close to that of the parent drug. Critically, the parent drug was rapidly metabolized in vivo and was completely absent in the studied plasma samples. The isobaric metabolite appeared as a single peak in the total ion current (TIC) trace, which data processing software could easily misidentify and quantify as the intact parent drug [22].

Case Study 2: Formation of an Isomeric Metabolite via Ring-Opening. Metabolism via ring-opening of a substituted isoxazole moiety generated an isomeric product. This metabolite exhibited an almost identical collision-induced dissociation (CID) mass spectrum as the original drug. In this instance, the parent drug and the isomeric metabolite co-eluted chromatographically. Without careful visual inspection of the TIC trace, data processing software would mistakenly quantify the combined signal and report it as the parent drug concentration [22].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and resolving such metabolite interferences.

Mitigation Strategies

The resolution of isobaric and isomeric interferences requires a multi-faceted approach:

- Stringent Chromatographic Separations: The primary defense is achieving baseline chromatographic separation between the parent drug and all potential interfering metabolites. This may require optimizing mobile phase composition, pH, column temperature, or using specialized stationary phases [22].

- Close Examination of Raw Data: Over-reliance on automated data processing software is a key risk. Scientists must routinely and carefully inspect raw TIC traces and individual spectra for signs of peak shoulder, asymmetry, or unexpected retention times, a practice that is often overlooked in highly automated workflows [22].

- Metabolite Profiling in Discovery: Early identification of major metabolic pathways during drug discovery can forewarn analysts of potential isobaric or isomeric metabolites, allowing for proactive method development [22].

The Impact of Peak Broadening on Data Quality

In liquid chromatography, an injected solute band broadens as it travels through the column, emerging as a Gaussian-shaped peak. This peak broadening is an inherent chromatographic phenomenon characterized by the number of theoretical plates (N), a measure of column efficiency [23].

Consequences for Detection Sensitivity and Solute Dilution

Peak broadening has a direct and quantifiable impact on two critical analytical parameters: detection sensitivity and solute dilution. As a peak broadens, the maximum concentration of the solute at the peak apex (c_max) decreases relative to its original injected concentration (c₀). This dilution effect lowers the signal-to-noise ratio, thereby reducing detection sensitivity and increasing the limit of quantification [23].

The relationship between column efficiency, injection volume, and solute dilution is described by equation 3, which can be used to predict relative detection sensitivity [23]: c_max / c₀ = (V_inj / V_r) * √(N / 2π)

Where:

- c_max = solute concentration at peak maximum

- c₀ = initial injected concentration

- V_inj = injection volume

- V_r = retention volume of the solute

- N = number of theoretical plates

The tables below summarize the quantitative effects of peak broadening under various conditions.

Table 1: Effect of Column Efficiency and Injection Volume on Solute Dilution (c_max/c₀ ratio)

| Theoretical Plates (N) | Injection Volume = 5 µL | Injection Volume = 20 µL | Injection Volume = 40 µL |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1,000 | 0.02 (98% dilution) | 0.08 (92% dilution) | 0.13 (87% dilution) |

| 10,000 | 0.06 (94% dilution) | 0.25 (75% dilution) | 0.40 (60% dilution) |

| 20,000 | 0.09 (91% dilution) | 0.35 (65% dilution) | 0.56 (44% dilution) |

| 30,000 | 0.10 (90% dilution) | 0.43 (57% dilution) | 0.68 (32% dilution) |

Table 2: Influence of Theoretical Plates on Peak Width and Relative Detector Response (V_inj = 10 µL, V_r = 4 mL)

| Column | Theoretical Plates (N) | Peak Width (4σ_v, µL) | Relative Detection Sensitivity (c_max/c₀) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 400 | 800 | 0.02 |

| 2 | 2,000 | 357 | 0.04 |

| 3 | 5,000 | 226 | 0.06 |

| 4 | 10,000 | 160 | 0.09 |

| 5 | 20,000 | 113 | 0.13 |

| 6 | 100,000 | 51 | 0.28 |

| 7 | 1,000,000 | 16 | 0.89 |

Mitigation Strategies for Peak Broadening

- Column Selection: Use columns packed with smaller, uniform particles to achieve higher theoretical plate counts.

- Injection Volume Optimization: Increasing the injection volume can directly improve detection sensitivity, as shown in Table 1, but must be balanced against potential volume-overload effects on efficiency [23].

- Instrument Optimization: Reducing extra-column volume, optimizing flow rates, and increasing column temperature can minimize peak broadening [23].

Experimental Protocols for Identification and Correction

Protocol 1: Investigating Metabolite Interferences in LC-MS/MS

This protocol is designed to systematically identify and characterize interferences from isobaric and isomeric metabolites [22].

- Step 1: Incubate the drug with appropriate biological systems (e.g., hepatocytes, liver microsomes) to generate a comprehensive metabolite profile.

- Step 2: Analyze the metabolite-rich sample alongside a pure standard of the parent drug using the candidate LC-MS/MS method.

- Step 3: Critically compare chromatograms. Overlay the TIC and extracted ion chromatograms (XICs) of the parent drug MRM transition from both samples.

- Step 4: Identify additional peaks or shoulder peaks in the metabolite-rich sample that are not present in the pure standard.

- Step 5: If a suspect peak is found, acquire its MS/MS spectrum. Compare this spectrum to that of the parent drug. Isomeric metabolites will show nearly identical fragments, while isobaric metabolites from different pathways may show different fragments.

- Step 6: If interference is confirmed, optimize the chromatographic method to achieve baseline resolution between the parent drug and the interfering metabolite.

- Step 7: Re-validate the optimized method for selectivity, sensitivity, accuracy, and precision.

Protocol 2: Matrix Overcompensation Calibration (MOC) for ICP-MS

While LC-MS/MS deals with organic molecular interferences, Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) faces matrix effects from concomitant elements. The Matrix Overcompensation Calibration (MOC) strategy is a novel approach to correct for carbon-based matrix effects in multielement analysis, such as in fruit juices [24].

- Sample Preparation (Dilute-and-Shoot): Dilute the sample (e.g., 1:50) in a mixture of 1% (v/v) HNO₃, 0.5% (v/v) HCl, and 5% (v/v) ethanol. The ethanol serves as the Matrix Markup (MM).

- Calibration Standard Preparation: Prepare the calibration standard series in the identical diluent: 1% HNO₃−0.5% HCl−5% ethanol.

- ICP-MS Analysis: Introduce both the diluted samples and the calibration series to the ICP-MS for detection.

- Principle: The added ethanol overwhelms the existing carbon content from the sample matrix, creating a new, dominant, and uniform carbon environment in all samples and standards. This effectively corrects for variable carbon effects across different samples, allowing the use of a single, universal external calibration curve, thereby enhancing throughput without sacrificing accuracy [24].

The workflow for this strategy is outlined below.

Protocol 3: Advanced Bucketing for NMR Metabolomics

In Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) based metabolomics, accurate "bucketing" (binning spectral data) is critical. A line-broadening factor can be applied to a reference spectrum to create an automatic, yet accurate, bucketing pattern that minimizes peak splitting, especially in studies with minor peak misalignment [25].

- Step 1: Calculate an average spectrum from all spectra in the study set using software like Bruker Amix.

- Step 2: Apply a line broadening (lb) factor (e.g., 1.0 Hz) to this average spectrum in processing software (e.g., Bruker Topspin) to smooth the spectrum.

- Step 3: Identify bucket boundaries by locating the troughs (local minima) between peaks in the smoothed average spectrum. This can be automated with a simple algorithm that calculates the derivatives to find these points.

- Step 4: Filter the bucket boundaries by removing buckets smaller than 0.005 ppm or larger than 0.3 ppm, as these ranges are unlikely to contain real NMR peaks.

- Step 5: Import the bucket table into analysis software as a pattern file. The resulting bucketing pattern is highly accurate, comparable to careful manual bucketing, but with greater efficiency and reproducibility [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful navigation of analytical interferences requires a suite of reliable reagents, materials, and software tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Mitigating Interferences

| Reagent / Material | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| High-Efficiency LC Columns | Minimizes chromatographic peak broadening, thereby improving detection sensitivity and resolution of analytes [23]. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Standards | Internal standards for MS quantification that correct for matrix effects and compensate for analyte loss during sample preparation. |

| Matrix Markup Reagents (e.g., Ethanol) | Used in strategies like MOC for ICP-MS to overcompense and correct for matrix effects of carbon origin [24]. |

| Metabolite Generation Systems | In vitro systems (hepatocytes, microsomes) used to proactively generate metabolite profiles for interference investigation [22]. |

| Deuterated Solvent with TSP | Provides a lock signal and chemical shift reference (δ = 0.0 ppm) for NMR spectroscopy in metabolomics studies [25]. |

Table 4: Essential Software and Computational Tools

| Software / Tool | Function and Application |

|---|---|

| Quantitative Software (e.g., Census) | Flexible tools for quantitative MS data analysis, supporting label-free and labeled strategies, and offering algorithms to handle poor-quality measurements [26]. |

| QFeatures R Package | Manages and aggregates quantitative mass spectrometry data from peptides to proteins, maintaining traceability [27]. |

| AMIX / Topspin | Industry-standard software for NMR data processing, visualization, and bucketing [25]. |

| Color Contrast Checkers | Online tools to ensure sufficient visual contrast in data visualizations, improving accessibility and interpretation [28]. |

Advanced Analytical Techniques: Methods for Interference Removal and Peak Shape Control

Inductively Coupled Plasma Tandem Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS/MS) represents a significant advancement in elemental analysis, capable of measuring most elements in the periodic table at trace levels with detection limits that can extend below single part per trillion concentrations. [29] This technique has become indispensable across various fields, including environmental monitoring, geochemical analysis, and particularly in the analysis of long-lived radionuclides for nuclear decommissioning activities. [30] [29] The fundamental strength of ICP-MS/MS lies in its tandem mass spectrometer configuration, which incorporates two mass filtering devices separated by a collision/reaction cell (CRC). This design provides unprecedented control over ion chemistry within the CRC, enabling the effective resolution of spectral interferences that have historically plagued conventional single quadrupole ICP-MS. [31]

A paramount challenge in mass spectrometry, and a central theme in peak broadening research, is the presence of isobaric interferences—where ions of different elements share the same nominal mass-to-charge ratio (m/z), making them indistinguishable by the mass analyzer alone. [30] For radionuclide analysis, this frequently manifests as interferences from stable isotopes of neighboring elements, which can severely compromise the accuracy and reliability of measurements. [30] [32] For instance, the determination of (^{90}\text{Sr}) is complicated by the presence of (^{90}\text{Zr}), while (^{135}\text{Cs}) and (^{137}\text{Cs}) face challenges due to isobaric overlaps with (^{135}\text{Ba}) and (^{137}\text{Ba}), respectively. Overcoming these interferences is not merely an analytical exercise but a critical requirement for obtaining trustworthy data in nuclear decommissioning and environmental monitoring. The flexibility of ICP-MS/MS in using reactive gases in the CRC to selectively modify analyte or interference ions provides a powerful toolbox for mitigating these challenges and achieving the high-fidelity measurements required for safety and regulatory compliance. [30] [31]

Theoretical Foundations of Interference Removal with N2O and NH3

Principles of Collision/Reaction Cell Operation

The collision/reaction cell (CRC) in an ICP-MS/MS is an enclosed multipole ion guide situated between the two mass filters. When pressurized with a specific gas, it facilitates controlled interactions between the incoming ion beam and the gas molecules. [29] These interactions are harnessed to remove interferences through two primary modes:

- Reaction Mode: This mode employs a reactive gas (e.g., (\text{N}2\text{O}), (\text{NH}3), (\text{H}_2)) to induce chemical reactions that selectively alter the m/z of either the analyte ion or the interfering ion. Reactions can include charge transfer, atom transfer, or cluster formation. The second mass filter (Q2) is then set to monitor the new, interference-free product ion. [29] [31]

- Collision Mode (with KED): This mode typically uses an inert gas like Helium ((\text{He})). Polyatomic interfering ions, being larger than monatomic analyte ions, undergo more frequent collisions with the gas molecules and lose more kinetic energy. An energy barrier at the cell exit filters out these lower-energy polyatomic interferences, while the analyte ions retain sufficient energy to pass through—a process known as Kinetic Energy Discrimination (KED). [33] [29] [31]

The key advantage of ICP-MS/MS over single quadrupole instruments with CRCs is the presence of the first mass filter (Q1). Q1 can be set to allow only the ions at the target mass (including both the analyte and the on-mass interference) to enter the CRC. This prevents other matrix ions from entering the cell and forming new product ions that could create secondary interferences, thereby simplifying the reaction chemistry and enhancing the reliability of the method. [31]

Chemistry of N2O and NH3 as Reaction Gases

Nitrous Oxide ((\text{N}2\text{O})) is a well-studied reaction gas for stable isotope analysis, but its application to radionuclide analysis has been limited until recently. [30] [32] (\text{N}2\text{O}) can act as an oxygen donor, facilitating oxygen atom transfer reactions. This is particularly useful for converting certain analyte ions into their oxide species (( \text{M}^+ + \text{N}2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{MO}^+ + \text{N}2 )), effectively shifting them to a higher, interference-free mass for measurement. [30]

Ammonia ((\text{NH}3)) is a highly selective reactive gas known for its propensity to undergo charge transfer reactions with many interfering species while remaining largely unreactive with many analyte ions. (\text{NH}3) has a high proton affinity and can form stable cluster ions with some interferents, thereby removing them from the spectral window of interest. [31]

The combination of (\text{N}2\text{O}) and (\text{NH}3) creates a synergistic gas mixture. Recent research demonstrates that this mixture provides a significant enhancement in the removal of isobaric interferences compared to using (\text{N}2\text{O}) alone. [30] [32] The (\text{NH}3) component can effectively suppress interfering ions that are not efficiently removed by (\text{N}_2\text{O}), leading to cleaner backgrounds and significantly improved detection limits for a range of radionuclides. [30]

Experimental Performance Data for Radionuclide Analysis

The application of the (\text{N}2\text{O}/\text{NH}3) gas mixture in ICP-MS/MS has been systematically evaluated for ten radionuclides of particular interest in the context of nuclear decommissioning. The following table summarizes the key performance metrics, including the instrument detection limits (IDLs) achieved using this approach. [30] [32]

Table 1: Analytical Performance of ICP-MS/MS with N2O/NH3 for Selected Radionuclides

| Radionuclide | Primary Isobaric Interference(s) | Instrument Detection Limit (Mass) | Instrument Detection Limit (Activity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (^{41}\text{Ca}) | (^{41}\text{K}) | 0.50 pg g(^{-1}) | 0.0016 Bq g(^{-1}) |

| (^{63}\text{Ni}) | (^{63}\text{Cu}) | Not Specified for mixture | Not Specified for mixture |

| (^{79}\text{Se}) | (^{79}\text{Br}) | 0.11 pg g(^{-1}) | 5.4 × 10(^{-5}) Bq g(^{-1}) |

| (^{90}\text{Sr}) | (^{90}\text{Zr}) | 0.11 pg g(^{-1}) | 0.56 Bq g(^{-1}) |

| (^{93}\text{Zr}) | (^{93}\text{Nb}) | Not Specified for mixture | Not Specified for mixture |

| (^{93}\text{Mo}) | (^{93}\text{Nb}) | 0.12 pg g(^{-1}) | 0.0044 Bq g(^{-1}) |

| (^{94}\text{Nb}) | (^{94}\text{Mo}) | Not Specified for mixture | Not Specified for mixture |

| (^{107}\text{Pd}) | (^{107}\text{Ag}) | Not Specified for mixture | Not Specified for mixture |

| (^{135}\text{Cs}) | (^{135}\text{Ba}) | 0.1 pg g(^{-1}) | 7.5 × 10(^{-6}) Bq g(^{-1}) |

| (^{137}\text{Cs}) | (^{137}\text{Ba}) | 0.1 pg g(^{-1}) | 0.33 Bq g(^{-1}) |

The data unequivocally shows that the (\text{N}2\text{O}/\text{NH}3) mixture provides exceptional performance for several critical radionuclides, including (^{41}\text{Ca}), (^{79}\text{Se}), (^{90}\text{Sr}), (^{93}\text{Mo}), and the cesium isotopes (^{135}\text{Cs}) and (^{137}\text{Cs}). [30] The achievement of sub-picogram per gram detection limits highlights the power of this gas mixture in mitigating isobaric overlaps and minimizing background noise, thereby enabling ultra-trace analysis. The study utilized single-element solutions of stable isotope analogues of the target radionuclides, as well as solutions of the interfering ions, to meticulously observe and characterize the reaction pathways with the cell gases. Abundance-corrected sensitivities were then applied to calculate the achievable separation factors and ultimate detection limits. [30] [32]

Detailed Methodologies and Workflow for ICP-MS/MS Analysis

General Method Development Workflow

Developing a robust ICP-MS/MS method for radionuclide analysis requires a systematic approach. The following workflow, implemented using Graphviz, outlines the key decision points and steps, from initial setup to final analysis, emphasizing the role of reactive gases.

Proper sample preparation is a critical precursor to successful ICP-MS/MS analysis. For biological and solid samples, digestion into a liquid form is mandatory. [34] [33]

- Digestion: Solid samples (e.g., tissues, soil, filters) require chemical digestion using strong acids (e.g., nitric acid) or alkalis, often assisted by heating in a dry block or microwave digestion system. [34]

- Dilution: Liquid biological samples (e.g., serum, urine) are typically diluted with an appropriate diluent. A dilution factor of 10 to 50 is common to maintain total dissolved solids (TDS) below 0.2%, thereby minimizing matrix effects and preventing nebulizer blockages. [34] Common diluents include:

- Dilute nitric acid: Prevents precipitation of certain elements but may cause protein precipitation in blood-based samples.

- Dilute alkalis (e.g., tetramethylammonium hydroxide): Better protein tolerance, but may require chelating agents like EDTA to keep some elements in solution.

- Surfactants (e.g., Triton-X100): Often added to solubilize lipids and disperse membrane proteins. [34]

- Nebulization: The liquid sample is introduced via a peristaltic pump to a pneumatic nebulizer, which creates a fine aerosol. This aerosol passes through a spray chamber that selects only the smallest droplets for efficient transport into the plasma. [34] [29]

ICP-MS/MS Operation with N2O/NH3 Gas Mixture

The core analytical protocol for leveraging the (\text{N}2\text{O}/\text{NH}3) mixture involves specific tuning of the instrument.

- Plasma Ignition and Stabilization: Ignite the argon plasma, ensuring robust and stable operation. Optimization should target low oxide levels (e.g., CeO+/Ce+ < 1.5%) to ensure efficient matrix decomposition and reduce potential polyatomic interferences. [31]

- Mass Calibration: Perform mass calibration across the intended mass range to ensure mass accuracy for both Q1 and Q2.

- Q1 Setting: Set the first quadrupole (Q1) to the mass of the target radionuclide (e.g., m/z 90 for (^{90}\text{Sr})). This allows both the analyte ion and the isobaric interferent (e.g., (^{90}\text{Zr}^+)) to enter the collision/reaction cell, while excluding all other ions. [31]

- CRC Gas Introduction: Introduce the optimized mixture of (\text{N}2\text{O}) and (\text{NH}3) gases into the collision/reaction cell. The specific flow rates for each gas should be optimized for the specific instrument and analyte pair, often leveraging manufacturer application notes or published methods. [30] [31]

- Reaction Monitoring: Inside the CRC, the gas mixture selectively reacts with the interference ions, either through charge transfer with (\text{NH}_3) or other chemical reactions, effectively removing them from the analytical path.

- Q2 Setting and Detection: Set the second quadrupole (Q2) to the same mass as Q1 (m/z 90 in this example) to monitor the unreacted analyte ions that have passed through the CRC. The detector (typically an electron multiplier) then counts the ions, and the software converts the count rate to concentration based on calibration standards. [29] [31]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for ICP-MS/MS with N2O/NH3

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS/MS Instrument | Core analytical platform with tandem mass filters and a reaction cell. | Must support the use of reactive gases and have precise control over Q1 and Q2. [29] [31] |

| N2O Gas (High Purity) | Primary reaction gas for oxygen atom transfer reactions. | Well-studied for stable isotopes; enhances interference removal when mixed with NH3. [30] [32] |

| NH3 Gas (High Purity) | Co-reaction gas for selective charge transfer and cluster formation with interferents. | Creates a synergistic effect with N2O, significantly improving interference removal for several radionuclides. [30] [31] |

| High-Purity Argon | Plasma gas and carrier gas for the sample aerosol. | High purity is essential to minimize background interferences from argon-based polyatomics. [34] [29] |

| Single-Element Standard Solutions | Used for tuning, calibration, and studying reaction pathways of analytes and interferents. | Critical for abundance-corrected sensitivity calculations and method development. [30] [32] |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid | Primary digesting agent and diluent for samples. | Essential for preparing samples and standards; low trace metal grade is required to avoid contamination. [34] |

The integration of a (\text{N}2\text{O}/\text{NH}3) gas mixture within an ICP-MS/MS platform represents a significant methodological advancement for the determination of challenging long-lived radionuclides. This approach directly addresses the persistent analytical problem of isobaric interferences, a key contributor to peak broadening and measurement inaccuracy in mass spectra. By leveraging well-understood ion-molecule reaction chemistries, the technique enables a dramatic reduction of spectral overlaps, achieving instrument detection limits at the sub-picogram per gram level for radionuclides such as (^{90}\text{Sr}), (^{135}\text{Cs}), and (^{79}\text{Se}). [30] The robust experimental protocols and the systematic method development workflow provide a clear roadmap for researchers and analysts in the nuclear sector. This methodology not only enhances the reliability of data critical for nuclear decommissioning and environmental monitoring but also enriches the broader thesis of spectral research by offering a powerful, chemically-resolved solution to the fundamental challenge of isobaric interference in mass spectrometry.

In chromatographic science, the broadening of peaks as compounds travel through the chromatographic column represents one of the most critical phenomena affecting separation quality. Ideal chromatographic systems would produce straight-line spikes without broadening, but in practice, various processes cause peaks to widen, reducing separation efficiency [8]. For researchers in drug development and mass spectrometry, understanding and controlling peak broadening is essential for achieving stringent separations, particularly when dealing with complex challenges such as isobaric interferences in mass spectral analysis. The efficiency of a chromatographic system, often quantified by its plate number (N), is approximately the same for all peaks in a chromatogram and can be calculated from first principles, allowing scientists to evaluate whether obtained performance is reasonable for their experimental conditions [35].

The reduced plate height (h) serves as a determining measure of chromatographic column efficiency, with smaller values indicating more efficient columns [8]. When abnormal peak shapes appear in chromatograms—including broadening, tailing, leading edges, shoulder peaks, or split peaks—they often indicate underlying problems that require investigation and resolution [36]. These abnormalities can be particularly problematic in trace analysis, where the ability to distinguish between closely eluting compounds is paramount for accurate qualitative and quantitative results.

Fundamental Theory of Column Chromatography

Peak Characteristics and Resolution

In column chromatography, samples are introduced as a narrow band at the top of the column. As the sample moves down the column, solutes begin to separate, and individual solute bands broaden and typically develop a Gaussian profile. When interactions with the stationary phase differ sufficiently, solutes separate into individual bands [37]. The progress of this separation is monitored by collecting fractions or using a detector to generate a chromatogram, which consists of a peak for each solute [37].

Key parameters for characterizing chromatographic peaks include (as shown in Figure 1):

- Retention time (tᵣ): The time between sample injection and the maximum response for the solute's peak

- Baseline width (w): The peak width at baseline between tangents drawn to the sides of the peak

- Void time (tₘ): The time required to elute nonretained solutes [37]

The resolution (RₐB) between two chromatographic peaks quantitatively measures their separation and is defined as:

[R{AB}=\frac{t{t, B}-t{t,A}}{0.5\left(w{B}+w{A}\right)}=\frac{2 \Delta t{r}}{w{B}+w{A}} \label{12.1}]

where B represents the later eluting of the two solutes [37]. Resolution values of 1.50 correspond to only 0.13% overlap between two elution profiles with identical peak areas, representing excellent separation [37].

Column Efficiency Measurements

Column efficiency, expressed as the plate number (N), can be calculated using two primary methods:

- Baseline width method: (N = 16 (tR / wb)^2) where (w_b) is the peak width at baseline between tangents drawn to the sides of the peak

- Half-height method: (N = 5.54 (tR / w{0.5})^2) where (w_{0.5}) is the peak width at half the peak height [35]

The half-height method is often preferred for automated determination by data systems because it doesn't require drawing tangents and can be used when peaks aren't fully separated from neighboring peaks, provided the valley between peaks is lower than the half-height [35]. From a statistical perspective, the plate number relates to the statistical broadening of a peak, with tangents drawn to the sides of a Gaussian distribution intersecting the baseline at ±2 standard deviations (σ), making the peak width at baseline equal to 4σ [35]. Thus, N can be expressed as:

[N = (t_R / σ)^2]

It's important to note that these calculations are only appropriate for isocratic separations and should not be used for gradient methods, where peak width alone better describes the separation [35].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Characterizing Chromatographic Performance

| Parameter | Symbol | Formula | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | RₐB | (R{AB}=\frac{2 \Delta t{r}}{w{B}+w{A}}) | Measures separation between two peaks |

| Plate Number (Baseline) | N | (N = 16 (tR / wb)^2) | Column efficiency for isocratic separations |

| Plate Number (Half-height) | N | (N = 5.54 (tR / w{0.5})^2) | Column efficiency when peaks are partially separated |

| Reduced Plate Height | h | (h = \frac{H}{d_p}) | Normalized efficiency measure (H = height equivalent to theoretical plate, d_p = particle diameter) |

Figure 1: Fundamental mechanisms contributing to chromatographic peak broadening, including both dead volume effects and column-based broadening processes described by the Van Deemter equation [8].

Dead Volume and Extra-Column Effects

Dead volume refers to all volume in a chromatographic system from the injector to the detector other than the column itself. Since separation only occurs in the column, all other volumes—including tubing used to connect components and volume within the detector cell—can contribute to peak broadening without enhancing separation [8]. In liquid chromatography, minimizing dead volume involves using narrow internal diameter tubing, short tubing lengths, small-volume detector cells, and specially designed fittings that reduce dead volume and minimize mixing [8].

Dead volume at tubing connections between the sample injection unit, column, and detector can cause significant peak broadening [36]. This often occurs when tubing protrusion length differs between manufacturers, particularly at column connections. Proper installation requires inserting tubing completely into the joint and pressing it against the far side as the connector is tightened [36]. Additionally, combining modern small-sized columns with older HPLC systems may necessitate capillary replacement, as the diameter of the capillary between the column and detector significantly influences peak width, along with detector flow cell size [38].

Column-Based Broadening Mechanisms

Within the chromatographic column, four primary processes contribute to peak broadening:

- Longitudinal diffusion: The natural diffusion of solute molecules along the length of the column

- Eddy diffusion: The varying flow paths through the packed column bed

- Mass transport broadening in the stationary phase: The finite time required for solute molecules to diffuse into and out of the stationary phase

- Mass transport broadening in the mobile phase: The different flow velocities across the column diameter and the time required for solute to diffuse through the mobile phase [8]

These four contributions form the basis of the van Deemter equation, first described by J. J. van Deemter in 1956, which relates these terms to the reduced plate height and provides a theoretical framework for understanding column efficiency [8].

Practical Causes of Abnormal Peak Shapes

Abnormal peak shapes in HPLC analysis can arise from multiple practical factors:

- Column deterioration: Changes in column packing status, contaminant accumulation, microparticle blockage, or desorption from the solid phase can all degrade peak shape. A slight gap in packing material at the column inlet often causes shoulder or split peaks [36]

- Inappropriate sample solvent or injection volume: Strong solvents in the sample solution can cause significant peak broadening, particularly when the injection volume is high [36]

- Temperature gradients within columns: Using high flow rates, high column temperatures, or large internal diameter columns can create temperature gradients across the column, leading to peak broadening [36]

- Inappropriate detector response settings: Slower detector response settings reduce noise but cause peak broadening, particularly for early-eluting peaks [36]

- Incorrect mobile phase pH: For ionizable compounds, the pH of the mobile phase should never match the pKa of the substance [38]

- Overloaded detection or column: Exceeding the detector's linear range or using excessive injection volume, particularly with small internal diameter columns, can distort peak shapes [38]

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Peak Broadening Issues in Chromatography

| Problem Category | Specific Issues | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| System Configuration | Excessive dead volume in connections; Large detector flow cell; Low data acquisition rate; System leaks | Use narrow ID tubing and proper fittings; Replace with smaller flow cell; Increase acquisition rate; Check for and fix leaks [38] [36] |

| Method Parameters | Incorrect flow rate; Wrong sample solvent strength; High injection volume; Improper mobile phase pH; Incorrect gradient | Adjust flow to column specifications; Match sample solvent to mobile phase; Reduce injection volume; Adjust pH away from analyte pKa; Optimize gradient [38] [36] |

| Column Issues | Column deterioration; Contamination; Void formation; Inadequate focusing | Replace guard column; Rinse or backflush column; Replace column; Adjust initial gradient conditions [38] [36] |

Chromatographic Challenges in Mass Spectrometry

Isobaric and Polyatomic Interferences

In mass spectrometric analysis, particularly when coupled with chromatography, several types of interferences can compromise results:

- Isobaric interferences: Result from equal mass isotopes of different elements present in the sample solution. Low-resolution instruments cannot distinguish between these isotopes. While elements with multiple isotopes may allow switching to an alternative isotope, monoisotopic elements (including ⁹Be, ²³Na, ²⁷Al, ⁷⁵As, and others) have no such alternative [4]

- Polyatomic (molecular) interferences: Caused by recombination of sample and matrix ions with Ar and other matrix components such as O, N, H, C, Cl, S, and F. These interferences become significant starting at mass 39K and are particularly troublesome for first-row periodic table elements (K through Se) due to numerous combinations of Ar with matrix components [4]

- Doubly charged ion interferences: Arise from doubly charged element isotopes with twice the mass of the analyte isotope. For example, ²⁰⁶Pb⁺⁺ (m/e = 103) can interfere with ¹⁰³Rh at high Pb concentrations [4]

Abundance Sensitivity and Resolution

Abundance sensitivity represents a critical consideration when measuring a low-concentration element adjacent to a high-concentration element. Tailing from the larger peak into the smaller peak can cause falsely elevated results for the smaller peak [4]. For quadrupole mass filters, abundance sensitivities for adjacent peaks on the low and high mass sides are not equal because peaks are asymmetric and tend to tail more on the low mass side [4].

Resolution in mass spectrometry is defined by the ability to distinguish between adjacent peaks. Peaks are considered resolved when the magnitude of the valley between two adjacent peaks is less than 10% of the mean magnitude of the peaks [4]. Most commercial quadrupole mass spectrometers achieve 0.8 amu mass resolution using this definition with equal adjacent peak intensities, though real-world samples rarely have adjacent peaks of equal intensity [4].

Figure 2: Common mass spectrometric interferences affecting chromatographic analysis, including isobaric, polyatomic, and doubly charged ion interferences with corresponding mitigation strategies [4].

Matrix Effects in ICP-MS

In inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), matrix effects present additional challenges:

- Space charge effects: Occur at the MS interface, the region between the skimmer tip and ion optics, and in the ion optics region. The result is suppression of signal in high concentrations of a matrix element, with larger masses (higher kinetic energy) causing more depression than lower masses [4]

- Salt buildup: High levels of matrix elements can lead to salt or oxide accumulation that partially or completely clogs the sampler cone. This is commonly addressed through dilution below 0.1% total solids, flow injection analysis, or ion exchange removal of matrix components [4]

Experimental Protocols for Optimal Separations

Method Development and Optimization

Developing robust chromatographic methods requires systematic approaches to minimize peak broadening and address potential interferences:

- Initial system suitability tests: Establish baseline performance using reference standards under controlled conditions

- Column selection: Choose appropriate column chemistry, dimensions (internal diameter, length), and particle size based on separation goals

- Mobile phase optimization: Adjust pH, buffer concentration, and organic modifier composition to enhance selectivity and efficiency

- Flow rate calibration: Set flow rates according to column specifications—typically 1 mL/min for 5 mm ID columns and 0.3 mL/min for 3 mm ID columns [38]

- Temperature control: Maintain consistent column temperature to minimize temperature-based broadening effects

- Detection parameters: Optimize detector response settings, data acquisition rates, and wavelength selection for specific analyses [36]

Quantitative Analysis Techniques in ICP-MS

For accurate quantitative analysis using ICP-MS coupled with chromatography, several techniques prove effective:

- External calibration with internal standards: The most popular approach for matrices that are known and can be matched. Internal standards help correct for drift, with selection following specific guidelines [4]:

- Avoid M²⁺ interferences

- Avoid MO and other molecular interferences

- Ensure any naturally occurring internal standard element in the sample is insignificant compared to the amount added

- Use internal standard elements as close as possible to the masses of the analyte elements

- Verify the matrix doesn't react with the internal standard to lower its concentration

- Common internal standard elements include ⁶Li, Be, Sc, Ga, Ge, Y, Rh, In, Cs, Pr, Tb, Ho, Re, Bi, and Th [4]

- Interference check analysis: Prepare for variations in matrix and analyte composition to determine if built-in corrections provide required accuracy [4]

- Peak hopping versus scanning: For final analysis, peak hopping saves time and represents a major advantage of low-resolution systems [4]

Column Maintenance and Troubleshooting Protocols

Maintaining column performance requires regular maintenance and systematic troubleshooting:

Column cleaning procedures:

- Follow manufacturer instructions for rinsing methods