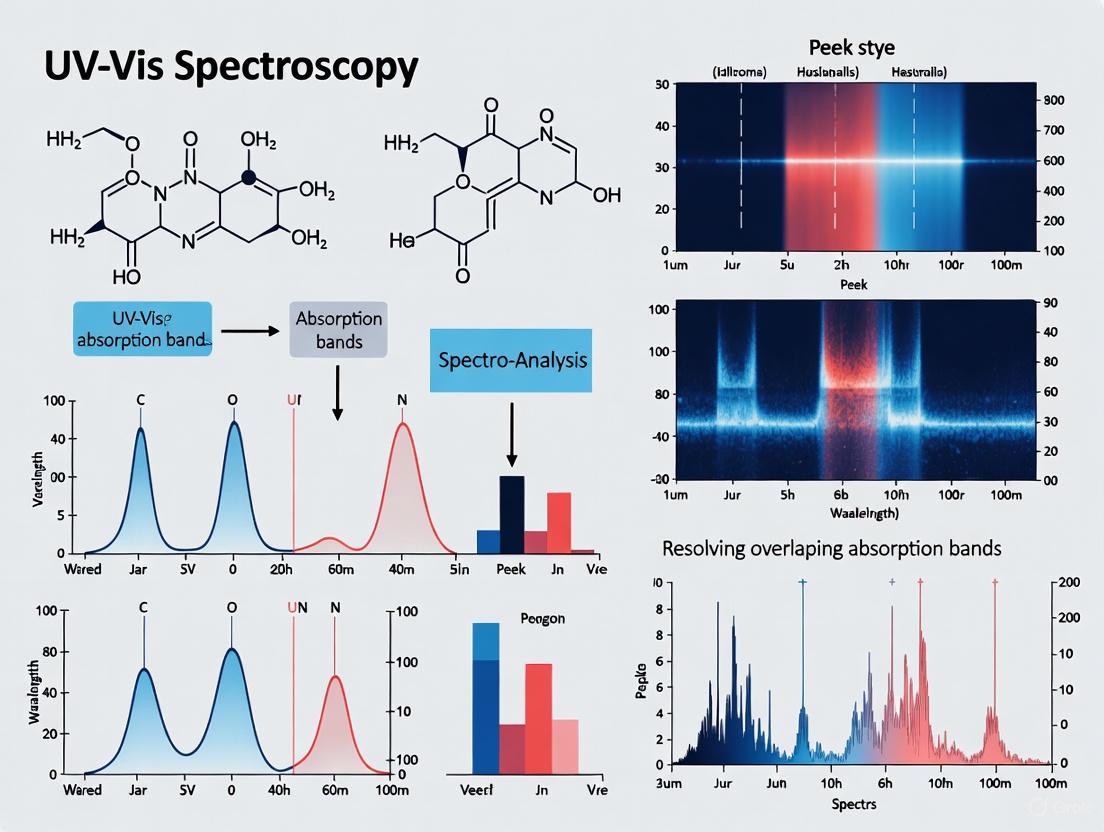

Resolving Overlapping UV-Vis Absorption Bands: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and scientists on deconvoluting complex, overlapping bands in UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Resolving Overlapping UV-Vis Absorption Bands: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a complete resource for researchers and scientists on deconvoluting complex, overlapping bands in UV-Vis spectroscopy. It covers the fundamental principles of electronic transitions and band formation, explores advanced mathematical and computational resolution techniques like Levenberg's method and DFT simulations, and addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies for quantitative analysis. A dedicated section on validation and comparative analysis, illustrated with a case study on hemoglobin quantification, offers practical insights for ensuring accuracy in characterizing chemical equilibria, biomolecules, and pharmaceuticals, directly supporting rigorous drug development and clinical research.

The Fundamentals of UV-Vis Band Overlap: Why It Happens and What It Reveals

Core Principles of Electronic Transitions and Chromophores

Core Theory

What are electronic transitions and chromophores?

Electronic transitions occur when a molecule absorbs ultraviolet or visible radiation, causing an electron to jump from a lower-energy molecular orbital to a higher-energy one [1]. The energy required for this transition corresponds to specific wavelengths of light [2].

A chromophore is the functional group within a molecule responsible for absorbing light in the UV-Vis region [2]. Common chromophores include C=C, C=O, and aromatic rings. The structure of the chromophore, especially the presence of conjugation, directly influences the energy needed for electronic transitions [3].

What are the primary types of electronic transitions?

The table below summarizes the four primary types of electronic transitions relevant to organic molecules [1] [4].

Table 1: Characteristics of Electronic Transitions in UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Transition Type | Electrons Involved | Typical λmax Range | Molar Absorptivity (ε) [L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹] | Example Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| σ → σ* | Sigma-bonding electrons | < 200 nm (High energy) | Very High | Methane, other alkanes |

| n → σ* | Non-bonding electrons | 150 - 250 nm | Medium (100 - 3000) | Saturated compounds with O, N, S, halogens |

| π → π* | Pi-bonding electrons | 200 - 700 nm (Conjugated systems) | High (1,000 - 10,000+) | Alkenes, alkynes, carbonyls, aromatics |

| n → π* | Non-bonding electrons | ~300 nm (Low energy) | Low (10 - 100) | Compounds with C=O, C≡N, N=O |

For organic and biological chemists, transitions of n or π electrons to the π* excited state are most experimentally convenient, as their absorption peaks fall within the standard UV-Vis range (200-700 nm) [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Resolving Overlapping Absorption Bands

A common challenge in research, such as in the quantitative analysis of tautomeric equilibria, is deconvoluting overlapping UV-visible absorption bands [5].

Table 2: Methodology for Resolving Overlapping Absorption Bands

| Step | Action | Technical Details | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Confirm Overlap | Collect spectra of individual pure components (if available) under identical solvent, pH, and temperature conditions. | Identifies the specific wavelengths where band overlap occurs. |

| 2 | Optimize Environment | Systematically vary solvent polarity [1] and sample pH [3]. | Induces bathochromic/hypsochromic shifts that may separate bands. |

| 3 | Record Full Spectrum | Ensure the instrument collects high-resolution data across a broad enough range. | Provides a complete dataset for mathematical analysis. |

| 4 | Apply Mathematical Analysis | Use specialized software for derivative spectroscopy or deconvolution algorithms [5]. | Resolves the composite spectrum into its individual component bands. |

Addressing Sample and Instrumentation Problems

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common UV-Vis Spectroscopy Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution | Prevention Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unexpected Peaks | Contaminated sample or dirty cuvette [6]. | Thoroughly clean cuvettes with compatible solvents. Prepare a fresh sample. | Handle cuvettes with gloved hands and use high-purity reagents. |

| Noisy or Unstable Absorbance | Instrument lamp not warmed up, low light source intensity, or contaminated cuvette [6] [7]. | Allow lamp to warm up for 20+ minutes (tungsten/halogen). Ensure cuvette clean path is clear. | Follow manufacturer's warm-up procedure. Calibrate with blank before measurements [7]. |

| Signal Too Weak/Strong | Sample concentration is too low or too high [6]. | Concentrate or dilute sample. Use a cuvette with a longer or shorter path length. | Aim for an absorbance between 0.1 and 1.0 AU for optimal results [7]. |

| Non-Linear Beer's Law Plot | Instrumental stray light, chemical associations/dissociations, or overly high concentration [4] [7]. | Ensure monochromatic light, check for chemical stability (e.g., pH), and dilute sample. | Use concentrations typically below 0.01 M to minimize molecular interactions [3]. |

The following workflow can help systematically diagnose and resolve common instrument and sample-related issues:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my sample's absorption maximum (λmax) shift when I change the solvent? The polarity of the solvent interacts differently with the ground and excited states of the chromophore. For n→π* transitions, increasing solvent polarity typically causes a blue shift (shorter wavelength) because the ground state is stabilized by solvation of the lone pair electrons. For π→π* transitions, a red shift (longer wavelength) is often observed because the excited state is more stabilized than the ground state [1] [3].

Q2: What is conjugation and how does it affect the spectrum? Conjugation occurs when pi bonds are separated by only one single bond, creating a system of delocalized electrons [8]. This delocalization lowers the energy gap between the HOMO and LUMO. A smaller energy gap requires less energy for an electronic transition, resulting in absorption at a longer wavelength (a bathochromic shift) [8] [3]. For example, beta-carotene, with its 11 conjugated double bonds, absorbs blue light and appears orange [2].

Q3: What is the difference between a chromophore and an auxochrome? A chromophore is a functional group that itself absorbs light in the UV-Vis region (e.g., C=C, C=O). An auxochrome is a functional group (often with lone pairs like -OH, -NH₂) that, when attached to a chromophore, modifies its absorption. Auxochromes typically cause a bathochromic shift to a longer wavelength and can increase the intensity of absorption (hyperchromic effect) [4].

Q4: My absorbance readings are unstable. What should I check first? First, ensure your instrument's light source has warmed up sufficiently (20+ minutes for tungsten/halogen lamps) [6]. Then, check that the cuvette is clean, free of scratches, and properly positioned in the beam path. Finally, verify the sample concentration is within the ideal range (absorbance between 0.1 and 1.0) and that solvent evaporation is not occurring [6] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for UV-Vis Spectroscopy

| Item | Function/Application | Critical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holds liquid sample for analysis. | Transmission down to ~200 nm; reusable with various path lengths (e.g., 1 cm). |

| Solvents (UV Grade) | Dissolve analyte without interfering with absorption. | High purity, "UV Grade" with low absorbance in UV region (e.g., acetonitrile, hexane). |

| pH Buffers | Control the ionization state of analytes, crucial for studying tautomers or ionic species [3]. | Non-absorbing in spectral range of interest; must not precipitate or react with analyte. |

| Standard Reference Materials | Validate instrument performance and wavelength accuracy. | Materials with known and sharp absorption peaks (e.g., holmium oxide filter). |

| Deuterium or Tungsten Lamp | Provides light source across UV and visible regions, respectively [4]. | Ensure lamp life is within specifications and it is properly warmed up before use. |

Experimental Protocol: Analyzing a Tautomeric Equilibrium

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for studying tautomeric equilibria, a classic example of resolving overlapping absorption bands [5].

Title: Quantitative Analysis of a Keto-Enol Tautomeric Equilibrium Using UV-Vis Spectroscopy.

Principle: Tautomers are structural isomers that readily interconvert. The keto and enol forms will have distinct chromophores and thus different absorption maxima (λmax). The equilibrium can be shifted by altering solvent polarity or pH, allowing for the isolation and analysis of each form's spectral signature.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of the tautomeric compound (e.g., acetylacetone) in a UV-grade solvent of low polarity (e.g., cyclohexane).

- Initial Spectrum: Fill a clean quartz cuvette with the solution and collect a baseline-corrected absorption spectrum from 220 nm to 350 nm.

- Solvent Perturbation: Prepare a second solution of the compound in a more polar, protic solvent (e.g., methanol-water mixture). Collect its absorption spectrum under identical conditions.

- pH Perturbation (if applicable): For tautomers sensitive to pH, prepare solutions buffered at different pH levels (e.g., pH 4 and pH 9) and collect their spectra.

- Data Analysis: Use the spectra to identify the λmax for each tautomer. The keto form typically absorbs at shorter wavelengths, while the enol form, due to extended conjugation, absorbs at longer wavelengths. The relative concentration of each tautomer can be determined from the absorbance at their respective λmax and their known molar absorptivities.

Key Observations:

- In non-polar solvents, the enol form is often favored, showing a stronger π→π* absorption band at longer wavelengths.

- In polar protic solvents, the keto form may be stabilized, increasing the intensity of its n→π* band.

- A clear isosbestic point (a wavelength where absorbance is constant regardless of the tautomer ratio) in the series of spectra indicates an equilibrium between two species.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the fundamental parameters of a UV-Vis absorption band? Every electronic transition in a UV-Vis spectrum appears as a band characterized by three fundamental parameters: the position (wavelength of maximum absorption, λ_max), the intensity (measured by absorbance and quantitatively expressed by the molar extinction coefficient, ε), and the width (typically measured as the full width at half maximum, FWHM) [9]. These parameters are used to estimate fundamental transition characteristics and are essential for quantitative analysis [9].

Why is accurately defining these parameters critical for analyzing overlapping bands? In complex spectra, individual component bands are often strongly overlapped and can have different widths, making it difficult to estimate their number and individual characteristics [9] [10]. Correctly resolving these overlapping bands to determine their position, intensity, and width is a necessary step to extract meaningful quantitative information about the sample, such as in the study of tautomeric equilibria or the analysis of multi-component mixtures [5] [9].

What are the most common challenges in resolving overlapping bands? The main challenges include [9]:

- Correctly estimating the number of overlapping bands contributing to the overall spectral envelope.

- Dealing with experimental noise, which can interfere with mathematical resolution methods.

- Accounting for or correcting an artificial baseline.

- Ensuring the efficiency and stability of the computational fitting procedure.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or inaccurate band parameter values upon repeated analysis.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| High Spectral Bandwidth | Ensure the instrument's spectral bandwidth is significantly narrower than the width of the absorption peak being measured. A wider bandwidth can lead to lower resolution and inaccurate measurements of extinction coefficient and band shape [11]. |

| Stray Light | Use a instrument with a double monochromator for measurements requiring high absorbance range (>2 AU). Stray light causes significant errors, especially at high absorbances, by reporting an incorrectly low absorbance [11]. |

| Wavelength Error | Conduct quantitative measurements at a wavelength close to the absorbance peak (λ_max), where the rate of change of absorbance is lowest. This minimizes inaccuracies from small errors in wavelength calibration [11]. |

| Deviations from Beer-Lambert Law | At high concentrations, absorption bands can saturate, causing absorption flattening and non-linear responses. Dilute the sample or use a shorter path length to bring the absorbance into a linear range [11]. |

Problem: Failure to achieve a good fit when deconvoluting overlapping bands.

| Potential Cause | Solution | |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Initial Estimates | The success of iterative fitting algorithms (like Levenberg's method) is highly dependent on the initial input values for position, intensity, and width. Use prior knowledge or derivative spectra to make informed initial guesses [10]. | |

| Wrong Number of Bands | An underestimation or overestimation of the number of underlying components will prevent a physically meaningful fit. Use statistical methods or singular value decomposition (SVD) available in software like `a | e` to help determine the number of components [12]. |

| Unaccounted for Baseline | A sloping or curved baseline can distort the fitted bands. Always include a baseline correction function (e.g., linear or polynomial) in the deconvolution model [9]. |

Experimental Protocols for Band Resolution

Methodology for the Mathematical Resolution of Overlapping Bands

The following logical algorithm provides a step-by-step guide for resolving individual bands from a complicated, overlapped spectrum [9] [10].

Quantitative Analysis Using Resolved Band Parameters

Once the pure component bands are resolved, their intensities (absorbance or ε) can be used for quantitative analysis. The relationship between these parameters for a single component is governed by the Beer-Lambert law [11]:

Table 1: Core Band Parameters and Their Interrelationship via the Beer-Lambert Law

| Parameter | Symbol & Units | Relationship & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Position | λ_max (nm) | Identifies the energy of the electronic transition; characteristic of the chromophore and its environment [9] [11]. |

| Intensity | A (Absorbance Units), ε (M⁻¹cm⁻¹) | A = ε c L The measured absorbance (A) is directly proportional to the concentration (c) and path length (L), with ε being the intrinsic molar absorptivity [11]. |

| Width | Δν₁/₂ or FWHM (cm⁻¹ or nm) | Related to the lifetime of the excited state and reflects the heterogeneity of the sample's microenvironment [9]. |

For a mixture of K components, the mass spectrum observed at any point is a linear combination of the pure component spectra, weighted by their concentrations [13]. This same principle applies to UV-Vis spectra of multi-component solutions, where the absorbance at any wavelength is the sum of contributions from all absorbing species.

Table 2: Key Software and Mathematical Tools for Band Analysis

| Tool Name | Function | Relevance to Band Parameter Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a | e - UV-Vis-IR Spectral Software [12] | General spectral analysis. | Performs operations like singular value decomposition (SVD) to determine the number of components and can fit Gaussians to spectra, directly aiding in the resolution of overlapping bands. |

| Chemissian [14] | Electronic structure and spectra analysis. | Allows visualization and interpretation of UV-Vis spectra from computational outputs (e.g., TDDFT). Helps link experimental band parameters to theoretical electronic transitions. | |

| Levenberg's Method [10] | Non-linear least squares algorithm. | A robust iterative procedure used to optimize the parameters (position, intensity, width) of individual bands during the deconvolution of a complex spectral envelope. | |

| Statistical Overlap Theory (SOT) [15] | Models peak crowding in separations. | Provides a theoretical framework for understanding the probability of peak overlap, which is directly analogous to the challenge of resolving overlapping absorption bands in spectroscopy. |

The relationships between the core concepts, data, and analytical goals in defining band parameters can be visualized as follows:

Fundamental Concepts of Band Overlap

What is Band Overlap and Why Does It Occur?

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, band overlap refers to the phenomenon where the absorption bands of two or more different chemical species in a mixture, or multiple electronic transitions from a single complex molecule, are insufficiently separated in the wavelength axis. This results in a single, broadened, or poorly resolved absorption peak in the measured spectrum [10]. Analyzing such spectra is a complicated task because these absorption bands can have different half-band widths, and their number is often difficult to estimate with confidence [10].

This overlap obscures the unique "fingerprint" of individual components, making it challenging to accurately identify substances or determine their concentrations. In the context of your research, resolving this overlap is critical for obtaining meaningful data on molecular structure and environment [10].

Key Molecular and Systemic Interactions Leading to Overlap

The root causes of band overlap often lie in the fundamental chemical and physical interactions within your sample. The table below summarizes the primary sources.

Table 1: Common Sources of Band Overlap in Chemical and Biological Systems

| Source of Overlap | Description | Common Examples in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple Chromophores | A molecule contains several light-absorbing groups whose individual electronic transitions occur at similar energies. | Proteins with aromatic amino acids (Tryptophan, Tyrosine); drug molecules with complex conjugated systems [16]. |

| Complex Mixtures | The simultaneous presence of multiple absorbing species in a solution, without chemical interaction between them. | Biological buffers containing nucleotides (e.g., ATP) and proteins [16]; mixtures of dyes or metabolites [16]. |

| Molecular Aggregation | Chromophores stack together through non-covalent interactions (e.g., π-π stacking), altering their individual absorption properties. | Dye aggregates; π-π stacked nucleobases in DNA [17]; supramolecular assemblies [17]. |

| Hydrogen Bonding | H-bonding with the solvent or between molecules can shift the energy levels of chromophores, leading to broadening and shifting of peaks. | DNA base pairing (e.g., G-C, A-T) [17]; solute-solvent interactions in aqueous solutions [17]. |

Methodologies for Resolving Overlapping Bands

Successfully deconvoluting overlapping bands requires a systematic approach, from sample preparation to advanced data analysis. The following workflow outlines the key steps in this process.

Experimental Protocol for Sample Preparation

Proper sample preparation is the first and most crucial line of defense against band overlap issues [6].

- Optimize Concentration: Aim for an absorbance value between 0.2 and 1.0 AU (Absorbance Units) at the peak of interest. Absorbance readings become unstable and non-linear above 1.0, which can exacerbate overlap interpretation problems [18] [19]. If the absorbance is too high, dilute your sample.

- Select Appropriate Solvent: Ensure the solvent does not absorb significantly in your wavelength range of interest. For UV work below 210 nm, use high-purity UV-grade solvents [6] [19].

- Ensure Sample Clarity: For solution samples, filter or centrifuge to remove any particulate matter that can cause light scattering, which distorts the baseline and absorption profile [19].

- Use Correct Cuvettes: Always use high-quality quartz cuvettes for UV-Vis measurements, as they transmit both UV and visible light. Plastic or glass cuvettes can absorb UV light and introduce errors [6] [18].

Mathematical Resolution Protocol: Levenberg's Method

When instrumental and sample optimization are insufficient, mathematical techniques are required. One powerful approach is the use of Levenberg's method, which is an algorithm for resolving individual bands from a complex, overlapped spectrum [10].

- Data Collection: Collect a high-resolution absorbance spectrum of the sample containing the overlapped bands.

- Initial Parameter Estimation: Make an initial estimate of the number of underlying bands, and their approximate position, height, and width. The number of bands can be difficult to estimate and may require prior knowledge of the system [10].

- Curve Fitting: The algorithm iteratively adjusts the parameters (position, amplitude, width) of individual band shapes (e.g., Gaussian or Lorentzian curves) to find the best fit to the measured, overlapped spectrum.

- Validation: The resolved spectrum (sum of the fitted individual bands) is compared to the original measured spectrum. The process repeats until the difference between them is minimized.

This method has been successfully applied to resolve the vibrational structured long-wavelength bands of molecules like trans-stilbene and its derivatives [10].

Advanced Technique: UV/Vis Diffusion-Ordered Spectroscopy (UV/Vis-DOSY)

A novel method to separate overlapping bands is UV/vis-DOSY, which combines principles from NMR with optical spectroscopy [16]. This technique separates species by their hydrodynamic radius (size) while simultaneously providing their UV/vis spectrum.

- Principle: A sample solution and pure solvent are placed in contact in a specialized cell. After the flow is stopped, molecules diffuse from the sample zone into the solvent zone at a rate inversely proportional to their size (via the Stokes-Einstein relation). The time-dependent absorption spectrum is recorded in the solvent zone [16].

- Data Output: The result is a 2D spectrum with absorption wavelength on one axis and diffusion coefficient (size) on the other. The UV/vis spectrum of a mixture is separated into the spectra of its different species, sorted by size [16].

- Application Example: This method can clearly resolve the individual spectra of a mixture of rhodamine B and methylene blue dyes, which have different sizes and diffuse at different rates, even though their absorption bands overlap in a conventional spectrum [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Having the right materials is fundamental for reliable spectroscopy and effective band resolution.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Band Resolution Experiments

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holds liquid sample in the light path. | Essential for UV range measurements; ensure cleanliness and correct path length (e.g., use shorter path length for high-concentration samples) [6] [18]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolves the analyte without interfering. | Use HPLC-grade or better; check the solvent's UV-cutoff wavelength to ensure it is transparent in your measurement region [19]. |

| Certified Reference Standards | For instrument calibration and validation. | Use certified materials like Holmium Oxide for wavelength verification. Ensures instrument performance and data accuracy [19]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Maintains biological molecules in a stable, native state. | The buffer should not absorb in the measured range. Phosphate buffers are often a good choice for UV studies [19]. |

| Syringe Pump & Flow Cell (for UV/vis-DOSY) | Creates the initial solvent-solution boundary for diffusion measurements. | Enables the use of advanced separation techniques like UV/vis-DOSY for complex mixtures [16]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs for Band Overlap Issues

The absorbance peaks in my spectrum of a biological mixture are broad and poorly resolved. What should I check first?

First, verify your sample concentration. A highly concentrated sample can lead to peak broadening and non-linear absorbance (deviating from the Beer-Lambert Law), making bands appear to merge. Dilute your sample to bring the maximum absorbance below 1.0 AU, ideally between 0.2 and 1.0, and recollect the spectrum [18] [19]. Second, check for sample clarity. Turbid solutions scatter light, creating a sloping baseline that distorts the true absorption profile. Filter or centrifuge your sample to remove any particulates [19].

I am using a common buffer, but my baseline is very high in the UV region. Why?

Many common biochemical buffers (e.g., Tris) or additives absorb strongly in the UV range below 230 nm. This high background absorption can mask the analyte's signal and create apparent overlap. Prepare a fresh blank using your exact buffer solution and ensure you are using a buffer with low UV absorbance for your wavelength range of interest [19].

The mathematical deconvolution of my overlapped band is not converging. What could be wrong?

The most common issue is an incorrect initial estimate of the number of component bands. The algorithm needs a reasonable starting point to find the optimal fit. Re-evaluate your system:

- Do you have prior knowledge (e.g., from literature or HPLC) about how many species are likely present?

- Could the overlap be due to more components than you initially assumed? Using an advanced technique like UV/vis-DOSY can provide an independent measurement of the number of species present based on their size, which can then be used to constrain the mathematical fitting [10] [16].

After resolving the bands, how can I validate that the individual peaks are real and not mathematical artifacts?

Validation is critical. If possible, compare your resolved spectra with the known absorption spectra of the pure compounds run under identical conditions (same solvent, pH, etc.). Another powerful method is to use an orthogonal technique, such as chromatography (HPLC-UV), to physically separate the components and measure their individual UV spectra, confirming the results from your mathematical deconvolution [16].

A fundamental challenge in UV-Vis spectroscopy is accurately analyzing samples where multiple chemical species, such as tautomers, coexist and contribute to a single, composite absorption spectrum [20]. The strong overlap of individual spectral bands can obscure crucial information about each component's identity, concentration, and electronic structure. This technical guide provides targeted methodologies and troubleshooting advice for researchers aiming to resolve these complex spectra, with a particular focus on systems involving tautomerism—a form of isomerism where species readily interconvert via proton transfer, leading to decisive modifications in chemical bonding and functionality [20].

Mathematical Resolution of Overlapping Bands

Electronic transitions in a spectrum are characterized by three fundamental parameters: position, intensity, and band width [9]. The mathematical resolution of a composite spectrum into its individual components relies on determining the number of overlapping bands and optimizing these parameters for each component to reconstruct the observed signal.

Key Steps and Challenges:

- Band Number Estimation: The first and often most difficult step is estimating the correct number of underlying bands. Initial guesses can be informed by chemical knowledge of the system or by examining second derivatives of the spectrum.

- Noise Management: The presence of noise in experimental data can severely impact the accuracy of the resolved bands. Smoothing algorithms or weighted least-squares fitting are often employed to mitigate this issue [9].

- Baseline Correction: An artificial or incorrectly fitted baseline can introduce significant errors. It is crucial to identify and subtract the baseline before or during the decomposition process [9].

- Computational Efficiency: The computing procedure must be efficient enough to handle the non-linear optimization problem, especially when dealing with a large number of spectral data points or multiple components [9].

Algorithmic Approach: A logical algorithm using the Levenberg-Marquardt method is highly effective for this non-linear curve-fitting problem [10]. This method combines the steepest descent and Gauss-Newton algorithms for robust convergence.

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for Resolved Bands of trans-Stilbene Derivatives [10]

| Compound | Band Assignment | λ_max (nm) | Absorbance | Half-Band Width (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| trans-Stilbene | Band 1 | ~300 | Varies | ~30 |

| Band 2 | ~320 | Varies | ~35 | |

| Derivative A | Band 1 | ~305 | Varies | ~32 |

| Band 2 | ~325 | Varies | ~36 | |

| Derivative B | Band 1 | ~310 | Varies | ~31 |

| Band 2 | ~330 | Varies | ~37 |

Experimental Protocols for Tautomeric Systems

Tautomeric equilibria, such as the keto-enol equilibrium in 3-hydroxypyridine (3HP), present a classic challenge where the individual UV-Vis absorption bands of tautomers overlap strongly [20]. Traditional methods involve perturbing the equilibrium by changing solvents or pH to detect spectral variations, which are then decomposed using statistical methods [20].

Advanced Spectroscopic Technique: Resonant Inelastic X-ray Scattering (RIXS)

RIXS offers a more direct method to disentangle the spectral contributions of individual tautomers in a mixture [20].

Principle: The technique exploits the large chemical shift in core-level excitation energies (e.g., at the nitrogen K-edge) between the two tautomers. By tuning the X-ray energy to the specific absorption resonance of one tautomer, the subsequent emission (RIXS) spectrum provides a "pure" map of its valence electronic excitations [20].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare an aqueous solution of 3HP, which exists as a nearly 1:1 mixture of enol and keto tautomers [20]. The sample is typically introduced as a liquid jet for measurement [20].

- Data Collection:

- Tune the incident X-ray beam to the specific π* resonance of the enol tautomer and collect a RIXS spectrum.

- Tune the incident X-ray beam to the specific π* resonance of the keto tautomer and collect a second RIXS spectrum.

- This generates a 2D map where regions of emission intensity are associated with each tautomer [20].

- Data Interpretation:

- The RIXS spectra for each tautomer contain transitions from occupied molecular orbitals into the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO).

- Use scattering anisotropy (comparing spectra from vertically and horizontally polarized X-rays) to assign peaks to transitions from π or σ bonding manifolds [20].

- Key Insight: The presence of a strong nitrogen lone-pair peak (~5 eV energy loss) is a clear signature of the enol form, which is absent in the keto form where the lone pair is involved in an N-H bond [20].

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My UV-Vis spectrum of a carbonyl compound shows a weak absorbance at ~275 nm and a very strong one below 200 nm. What transitions do these represent? A1: The weak band at ~275 nm is an n→π* transition, where an electron from a non-bonding orbital on the oxygen is promoted to the π* orbital of the C=O group. The strong band below 200 nm is a π→π transition within the C=O bond. The n→π transition is weak because the non-bonding and π* orbitals have poor spatial overlap [21].

Q2: How does conjugation affect the UV-Vis spectrum of a molecule? A2: Increasing conjugation decreases the energy gap (ΔE) between the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). This results in a bathochromic shift (red shift), meaning the wavelength of maximum absorbance (λmax) increases and moves toward the visible region. For example, extending conjugation from ethene (λmax = 174 nm) to butadiene (λ_max = 217 nm) causes a clear red shift [22].

Q3: When using computational chemistry to predict a UV-Vis spectrum, how do I ensure I'm calculating an absorption spectrum and not an emission spectrum? A3:

- Absorption spectra are obtained by performing a time-dependent DFT (TD-DFT) calculation on the optimized ground-state geometry.

- Emission spectra are obtained by performing a TD-DFT calculation on the optimized excited-state geometry. If your calculation uses the ground-state geometry, the spectrum generated by your software (e.g., GaussView) is the absorption spectrum. The software might display both, but only the absorption spectrum is meaningful in this context [23].

Advanced Techniques: In Situ UV-vis-NIR Spectroscopy

For studying catalysts or reactions under operational conditions, in situ UV-vis-NIR spectroscopy is a powerful tool. It spans a broad range (200-2500 nm) to probe various electronic and vibrational transitions [24].

Table 2: UV-vis-NIR Spectral Regions and Transition Information

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Typical Transitions Observed | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet (UV) | 200 - 400 nm | Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT), Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer (MLCT), π→π* | Structural and electronic information, oxidation states [24]. |

| Visible (Vis) | 400 - 700 nm | d-d transitions of Transition Metal Ions (TMI) | Coordination environment of metal centers [24]. |

| Near Infrared (NIR) | 700 - 2500 nm | Overtones and combination bands of O-H, C-H, N-H vibrations | Probing structural defects and molecular interactions [24]. |

Application: This technique is widely used in heterogeneous catalysis to monitor active sites in real-time. For example, it can track changes in the oxidation state of copper or iron ions within a zeolite catalyst during a reaction, providing insights into the reaction mechanism and kinetics [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for Spectral Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role in Analysis |

|---|---|

| 3-Hydroxypyridine (3HP) | A prototypical model compound for studying keto-enol tautomerism in aqueous solution [20]. |

| Solvent Mixtures (various polarities) | Used to perturb tautomeric equilibria, allowing for the observation of spectral shifts for individual components [20]. |

| Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm | A key non-linear optimization algorithm for resolving individual bands from a complex, overlapped spectrum [10]. |

| TD-DFT (Time-Dependent DFT) | A computational method used to predict and assign electronic excitations and UV-Vis spectra from first principles [23]. |

| InChI Identifier | A standardized, non-proprietary identifier for chemical substances, crucial for unambiguous data sharing and compound registration in databases [25] [26]. |

Advanced Techniques for Spectral Deconvolution: From Algorithms to Practical Workflows

Mathematical Foundations for Resolving Overlapping Bands

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, the analysis of complex mixtures often results in overlapping absorption bands, where the spectra of individual components are superimposed. This presents a significant challenge for accurate qualitative and quantitative analysis. The mathematical resolution of these overlapping bands is therefore a critical foundation in spectroscopic research, enabling researchers to extract meaningful information about individual components from a composite signal. This guide outlines the core principles, methodologies, and practical protocols for effectively resolving such spectral overlaps, with a focus on applications in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development.

Core Mathematical Principles and Techniques

The resolution of overlapping UV-Vis absorption bands relies on the fact that individual electronic transitions in a spectrum are characterized by three fundamental parameters: position, intensity, and width [9]. The primary challenge lies in accurately determining the number of overlapping bands, dealing with spectral noise, and employing efficient computational procedures to deconvolute the composite signal [9].

The following table summarizes the key mathematical techniques used for resolving binary mixtures, along with their central principle and a common application challenge.

Table 1: Overview of Key Techniques for Resolving Overlapping Spectra

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Typical Application Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Derivative Spectrophotometry | Uses first or higher-order derivatives of absorbance with respect to wavelength to enhance minor spectral features and suppress broad-band background interference [27]. | Higher-order derivatives amplify high-frequency noise, requiring a balance between resolution enhancement and signal-to-noise ratio [27]. |

| Simultaneous Equation Method | Solves a set of linear equations based on the absorbance of each component at its wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) [28]. | Requires that the absorptivities of both drugs are known at the two selected wavelengths and that they obey Beer-Lambert's law [28]. |

| Dual Wavelength Method | Selects two wavelengths where the interfering component has the same absorbance (isoabsorptive point), thus canceling its contribution [28]. | Finding a suitable pair of wavelengths where the analyte shows a significant difference in absorbance while the interferent does not can be difficult in highly overlapping spectra [28]. |

| Ratio-based Methods (Ratio Difference, Ratio Derivative) | Uses the ratio of the absorption spectra of the mixture against a standard spectrum of one component to resolve the other component [28]. | The accuracy is highly dependent on the purity of the standard spectrum used as a divisor. |

| Bivariate Method | Employs linear calibration regressions at two optimally selected wavelengths for the simultaneous determination of both components in a mixture [28] [29]. | The selection of the two wavelengths is critical; Kaiser's method is often used to determine the optimal wavelength pair for the sensitivity matrix [29]. |

| Advanced Absorbance & Spectrum Subtraction | Mathematically subtracts the absorbed spectrum of one component from the mixture's spectrum to isolate the spectrum of the second component [28] [29]. | Requires prior knowledge of the exact concentration of the component to be subtracted, or the use of an isoabsorptive point to find the total concentration [29]. |

The logical relationship and primary application of these methods for resolving a binary mixture can be visualized in the workflow below.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This section provides step-by-step methodologies for implementing key resolution techniques, using real analytical applications as models.

Protocol: Simultaneous Equation Method for Hydroxychloroquine and Paracetamol

This method is applied when the spectra of two components, Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) and Paracetamol (PAR), overlap but each has a distinct λmax [28].

- Step 1: Obtain Pure Standard Solutions. Prepare known concentrations of pure HCQ and PAR in a suitable solvent (e.g., distilled water).

- Step 2: Record Absorbance Spectra. Scan the absorption spectra of both pure standard solutions within the 200-400 nm range.

- Step 3: Select Two Wavelengths. Choose the wavelength of maximum absorption (λmax) for each drug. In the HCQ/PAR model, these are 220 nm (λmax of HCQ) and 242.5 nm (λmax of PAR) [28].

- Step 4: Determine Absorptivity Values. Calculate the absorptivity (A 1%, 1 cm) for each drug at both selected wavelengths.

- Let

ax1andax2be the absorptivities of HCQ at 220 nm and 242.5 nm, respectively. - Let

ay1anday2be the absorptivities of PAR at 220 nm and 242.5 nm, respectively. - Reported values: ax1=0.0881, ax2=0.0339, ay1=0.0419, ay2=0.0521 [28].

- Let

- Step 5: Formulate Simultaneous Equations. For a mixture sample, measure the absorbance (A1 and A2) at the two selected wavelengths. The concentrations of HCQ (Cx) and PAR (Cy) in the sample are calculated using:

Cx = (A2*ay1 - A1*ay2) / (ax2*ay1 - ax1*ay2)Cy = (A1*ax2 - A2*ax1) / (ax2*ay1 - ax1*ay2)

- Validation Note: This method requires that the absorptivities of both drugs are known at the two selected wavelengths and that they obey Beer-Lambert's law across the working concentration range [28].

Protocol: Advanced Absorbance Subtraction (AAS) for Ciprofloxacin and Metronidazole

This protocol is designed to determine one component in a binary mixture by leveraging isoabsorptive points and wavelengths where the interferent shows equal absorbance [29].

- Step 1: Identify an Isoabsorptive Point. Scan the spectra of the individual components and the mixture to find a wavelength where both components have the same absorptivity. For Ciprofloxacin (CIP) and Metronidazole (MET), this point is at 291.5 nm [29]. The total concentration of the mixture (Ctotal) can be determined from this point.

- Step 2: Determine MET in the presence of CIP:

- Measure the absorbance of the mixture at the isoabsorptive point (291.5 nm) and at a second wavelength (250 nm) where CIP has the same absorbance as it does at 291.5 nm.

- The absorbance difference of CIP between these two wavelengths is zero. Therefore, any measured difference in the mixture's absorbance is directly proportional to the concentration of MET.

- Calculate the concentration of MET using a pre-established regression equation [29].

- Step 3: Determine CIP in the presence of MET:

- Measure the absorbance of the mixture at the isoabsorptive point (291.5 nm) and at a different second wavelength (345 nm) where MET has the same absorbance as it does at 291.5 nm.

- The absorbance difference of MET between these two wavelengths is zero. The measured difference is thus proportional only to CIP.

- Calculate the concentration of CIP using its specific regression equation [29].

Protocol: Obtaining and Using Derivative Spectra

Derivative spectroscopy is a powerful tool for resolving overlapping bands and eliminating baseline shifts [27] [30].

- Step 1: Generate the Zero-Order Spectrum. Record the normal absorbance spectrum (zero-order) of the sample mixture.

- Step 2: Calculate the Derivative. Modern spectrophotometers use mathematical differentiation to compute the first or higher-order derivatives of the absorbance spectrum with respect to wavelength.

- First Derivative (¹D): Plots the rate of change of absorbance (dA/dλ). It crosses zero at the same wavelength as the λmax of the absorbance band in the zero-order spectrum. It is effective in eliminating constant baseline interference [27].

- Second Derivative (²D): Shows a negative peak (minimum) at the same wavelength as the λmax of the zero-order band. It is highly effective in resolving closely spaced or overlapping peaks [27] [30].

- Step 3: Quantitative Measurement. For quantification, use the peak-to-trough amplitude (for even-order derivatives) or the distance from a peak to the zero line (for odd-order derivatives) at a specific wavelength. For example, the first derivative amplitude at 329 nm has been used to determine Hydroxychloroquine where Paracetamol shows zero crossing and thus no interference [28].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Even with robust mathematical techniques, researchers often encounter practical problems. The following guide addresses common issues and their solutions.

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Resolving Overlapping Bands

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High noise in derivative spectra | Amplification of high-frequency noise during the differentiation process [27]. | Apply smoothing functions (e.g., Savitzky-Golay filter) to the zero-order spectrum before derivative calculation. Optimize the smoothing parameters to balance noise reduction and signal preservation [27]. |

| Deviation from Beer-Lambert's Law | High analyte concentration leading to molecular interactions or detector non-linearity; presence of stray light [19]. | Dilute the sample to bring the absorbance into the ideal range (0.2–1.0 AU). Ensure the instrument is well-maintained and calibrated for stray light [19]. |

| Poor resolution of closely overlapping bands | The overlapping bands are too broad or their λmax values are too close relative to their half-widths [10]. | Switch to a higher-order derivative (e.g., second or fourth derivative) which provides better band narrowing. Alternatively, combine derivative techniques with ratio methods [27]. |

| Inaccurate results with subtraction methods | Incorrect concentration estimate of the component being subtracted, or spectral contribution from an unknown interferent. | Use an isoabsorptive point to accurately determine the total concentration before subtraction. Validate the method by analyzing samples with known compositions [29]. |

| Significant baseline drift or shift | Fluctuations in the light source intensity, temperature changes in optical components, or dirty sample cuvettes [19]. | Use a double-beam instrument that compensates for real-time baseline drift. Ensure proper instrument warm-up and use matched, clean quartz cuvettes. Derivative spectroscopy can also help correct for baseline shifts [27] [19]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and their functions for conducting experiments on resolving overlapping UV-Vis bands, based on cited protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Double-Beam UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Equipped with software capable of mathematical processing (derivative calculation, spectral subtraction, etc.) [28] [29]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | 1 cm pathlength; for holding liquid samples without absorbing in the UV range [28] [29]. |

| Reference Standards | High-purity analytes (e.g., Hydroxychloroquine, Ciprofloxacin) for establishing calibration curves and absorptivity values [28] [29]. |

| Distilled / Deionized Water | A common solvent for preparing stock and working standard solutions, especially for water-soluble pharmaceuticals [28] [29]. |

| Volumetric Flasks | For precise preparation and dilution of standard and sample solutions (e.g., 10 mL flasks) [28] [29]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Holmium oxide or other certified filters for regular wavelength accuracy calibration of the spectrophotometer [19]. |

The decision-making process for selecting an appropriate resolution method based on the characteristics of the spectral overlap and available data is summarized below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the main advantage of using derivative spectroscopy over the simultaneous equation method? A1: Derivative spectroscopy excels at eliminating baseline shifts and enhancing minor spectral features, which is particularly useful for detecting shoulder peaks in heavily overlapping bands. The simultaneous equation method is more straightforward but requires well-resolved λmax points and is susceptible to errors from baseline drift [27] [30] [28].

Q2: Can these mathematical methods be applied to systems with more than two overlapping components? A2: While the principles extend to multi-component systems, the complexity increases significantly. Techniques like multivariate calibration (e.g., Principal Component Regression or Partial Least Squares) are more suitable for three or more components, as they can handle higher levels of spectral overlap and interaction [9].

Q3: How critical is instrument calibration for these resolution techniques? A3: Highly critical. Regular calibration of wavelength accuracy (using, e.g., holmium oxide filters) and absorbance accuracy is essential. Uncalibrated instruments can lead to shifts in λmax and erroneous absorptivity values, which directly impact the accuracy of all resolution methods, especially those relying on precise wavelength selection like the dual wavelength and simultaneous equation methods [19].

Q4: What is the simplest method to start with for a binary mixture with partial overlap? A4: The simultaneous equation method is often the simplest to implement initially, provided the two components have distinct and clear λmax values. It requires only the measurement of absorbance at two wavelengths and solving two linear equations, making it easy to compute and validate [28].

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, the analysis of complex mixtures is often complicated by strongly overlapped absorption bands. These bands can have different half-band widths, and their number is frequently difficult to estimate, making resolution a challenging task [10]. Computational methods, particularly optimization algorithms like Levenberg's, have become indispensable for extracting meaningful quantitative information from these complex spectral datasets. When combined with artificial neural networks (ANNs) and proper spectral preprocessing, these approaches enable researchers to resolve individual components in pharmaceutical mixtures, environmental samples, and biological matrices with remarkable accuracy [31] [32].

Core Algorithm Guide: Levenberg-Marquardt and Alternatives

Levenberg-Marquardt Algorithm Fundamentals

The Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm is a standard nonlinear least-squares optimization technique that combines gradient descent and Gauss-Newton methods. It's particularly effective for solving curve-fitting problems where model parameters must be estimated from experimental data.

Key Mechanism: The algorithm adaptively blends two approaches:

- Gradient Descent: Provides stability far from the minimum

- Gauss-Newton: Delivers fast convergence near the minimum

This hybrid approach makes LM particularly well-suited for resolving overlapping bands in UV-Vis spectroscopy, where it can be used to deconvolute individual spectral components [10].

Algorithm Selection Guide

| Algorithm | Core Mechanism | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Levenberg-Marquardt | Adaptive gradient descent/Gauss-Newton hybrid | Models with analytical derivatives; medium-sized parameter sets | Prone to matrix singularity errors; requires good initial guesses [33] |

| Nelder-Mead (Downhill Simplex) | Direct search using simplex geometric operations | Complex models without derivatives; robust parameter estimation | Slower convergence for high-dimensional problems [33] |

| Firefly Algorithm | Nature-inspired metaheuristic based on firefly flashing behavior | Variable selection and optimization in ANN models | Computationally intensive for very large datasets [32] |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ: How do I resolve "Error -20041: The system of equations cannot be solved because the input matrix is singular" when using Levenberg-Marquardt?

Problem: This error occurs when the algorithm's Jacobian matrix loses full rank, preventing the system from being solved [33].

Solutions:

- Check Initial Parameters: Ensure your initial coefficient estimates are physically reasonable and not zero

- Numerical Derivatives: If using numerical differentiation (e.g., with embedded ODE solvers), be aware that accumulated errors can make partial derivatives unreliable [33]

- Parameter Scaling: Normalize parameters to similar numerical scales to improve matrix conditioning

- Algorithm Switching: For models with iterative procedures (like Runge-Kutta ODE solvers), consider switching to derivative-free algorithms like Nelder-Mead [33]

FAQ: Why are my ANN predictions for component concentrations inaccurate despite high spectral quality?

Problem: Even with good spectral data, concentration predictions may suffer from poor accuracy.

Solutions:

- Variable Selection: Implement nature-inspired algorithms like the Firefly Algorithm (FA) to identify the most informative wavelengths, reducing model complexity and improving predictive performance [32]

- Data Preprocessing: Apply appropriate spectral preprocessing techniques including baseline correction, smoothing, and scattering correction to enhance signal quality [34] [35]

- Network Architecture: Optimize the number of hidden layers and neurons using cross-validation techniques like relative root mean square error of cross-validation (RRMSECV) [32]

FAQ: How can I resolve overlapping absorption bands for compounds without strong chromophores?

Problem: Simple sugars like glucose lack strong chromophoric groups, resulting in low absorbance and no distinct peaks in the UV-Vis range [31].

Solutions:

- Focus on UV Region: Analyze spectral variations in the ultraviolet region (200-400 nm) where subtle absorbance changes are more pronounced [31]

- Leverage Subtle Variations: Utilize computational methods to exploit minor intensity fluctuations arising from light scattering, refractive index changes, and hydrogen bonding effects [31]

- Advanced Modeling: Implement feed-forward artificial neural networks that can learn complex, non-linear relationships between subtle spectral variations and analyte concentrations [31]

Experimental Protocol: Resolving Overlapping Bands in Pharmaceutical Mixtures

Sample Preparation and Spectral Acquisition

This protocol outlines the methodology for simultaneous determination of propranolol, rosuvastatin, and valsartan in ternary mixtures, adaptable for other pharmaceutical compounds [32].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Standards | Propranolol HCl, Rosuvastatin Ca, Valsartan (≥98% purity) | Target analytes for quantification |

| Solvent | Double-distilled water | dissolution medium and spectral blank |

| Quartz Cuvettes | 1 cm pathlength, high UV transmission | Sample containment for spectral measurement |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometer | Shimadzu UV-1800 or equivalent with 1 nm resolution | Spectral data acquisition |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Stock Solution Preparation:

- Accurately weigh 10 mg of each drug standard

- Dissolve in 100 mL distilled water to obtain 100 µg/mL stock solutions

- Store at room temperature and use within 24 hours to prevent degradation

Calibration Set Design:

- Employ a partial factorial design with 3 factors (drug concentrations) at 5 levels each

- Generate 25 samples with central level at 6 µg/mL and range of 2-10 µg/mL

- This ensures coverage of the linear dynamic range

Spectral Acquisition:

- Use 1 cm quartz cuvettes with appropriate pathlength

- Set spectrophotometer parameters: 200-400 nm range, fast scan speed, 1 nm interval

- Record triplicate measurements for each sample to ensure reproducibility

- Maintain constant temperature (~25°C) throughout measurements

Data Preprocessing Workflow

Proper preprocessing is essential before computational analysis [34] [35]:

- Baseline Correction: Apply piecewise polynomial fitting or morphological operations to remove instrumental offsets

- Smoothing: Implement Savitzky-Golay filtering (window size = 7 points, polynomial order = 2) to reduce high-frequency noise while preserving spectral features [31]

- Data Normalization: Use map minmax function to scale spectral data to a consistent range [31]

- Region Selection: Exclude spectral regions above 350 nm where absorbance is minimal and uninformative [32]

Computational Analysis and Model Training

Computational Analysis Workflow for Spectral Resolution

ANN Model Development:

- Data Partitioning:

- Divide preprocessed spectral data into three sets:

- Training (70%), Validation (15%), and Testing (15%) [31]

Firefly Algorithm Optimization:

- Implement FA for variable selection to identify optimal wavelengths

- This creates simpler, more interpretable models with improved prediction accuracy [32]

Network Architecture Optimization:

- Use a feed-forward architecture with backpropagation

- Systematically vary hidden layers and neuron count

- Select optimal architecture based on RRMSECV minimization [32]

Model Training:

- Train using Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm for fast convergence

- Monitor performance via correlation coefficient (R) and mean squared error (MSE)

- Target R > 0.98 for satisfactory performance [31]

Advanced Applications and Validation Framework

Performance Metrics and Model Validation

For the developed FA-ANN models, comprehensive validation is essential:

Quantitative Performance Metrics:

- Calculate Relative Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RRMSEP)

- Determine coefficient of determination (R²) between predicted and actual concentrations

- Assess accuracy via percent recovery (target: 98-102%)

- Evaluate precision through relative standard deviation (RSD% < 2%) [32]

Method Selectivity:

- Use standard addition techniques to determine matrix effects

- Verify ability to quantify each analyte in presence of sample matrix and other components [32]

Application to Real-World Samples

The protocol can be applied to pharmaceutical formulations:

Sample Preparation:

- Accurately weigh tablet powder equivalent to 10 mg active ingredient

- Dissolve in 100 mL distilled water, sonicate for 15 minutes

- Filter through 0.45 μm syringe filters

- Dilute to appropriate concentration range before spectral acquisition [32]

Method Greenness Assessment:

- Evaluate environmental impact using Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) tool

- Assess practicality with Blue Applicability Grade Index (BAGI)

- Determine overall sustainability via Red-Green-Blue (RGB) model [32]

Comparative Performance Data

Algorithm Performance in Spectral Analysis

| Application Context | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous glucose solution analysis | Feed-Forward ANN (LM trained) | R > 0.98, low MSE across training/validation/testing sets | [31] |

| Cobalt species determination in acetic acid | ANN (LM algorithm) | RMSEP: 0.316-0.346 mM, R²: 0.988-0.996 | [36] |

| Cardiovascular drugs in ternary mixtures | FA-ANN (LM optimized) | Low RRMSEP, excellent accuracy and precision per ICH guidelines | [32] |

| Complex models with ODE solvers | Nelder-Mead | Successful convergence where LM failed with singularity errors | [33] |

This technical guide provides researchers with practical methodologies for implementing computational approaches to resolve challenging spectral overlaps. By following these protocols and troubleshooting guides, scientists can enhance the accuracy and reliability of their UV-Vis spectroscopic analyses across diverse application domains.

Leveraging Density Functional Theory (DFT) for Simulating Electronic Transitions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common sources of error in DFT calculations of UV-Vis spectra? Several common errors can affect the accuracy of your calculations:

- Integration Grid Settings: Using grids that are too sparse can lead to inaccurate energies and free energies. This is particularly problematic for meta-GGA (e.g., M06) and B97-based functionals. A grid of at least (99,590) points is recommended for reliable results [37].

- SCF Convergence Failure: The self-consistent field (SCF) process can fail to converge, especially for systems with complex electronic structures. Strategies to address this include using hybrid DIIS/ADIIS algorithms, applying level shifting, and using tight integral tolerances (e.g., 10⁻¹⁴) [37].

- Incorrect Treatment of Low-Frequency Vibrations: Very low-frequency vibrational modes (below 100 cm⁻¹) can be poorly described and lead to explosions in entropic corrections. Applying a correction that raises these modes to 100 cm⁻¹ for entropy calculations is recommended [37].

- Neglecting Solvent Effects: Performing calculations only in the gas phase can yield significant errors for molecules in solution. Using implicit solvent models like IEFPCM or explicit solvent molecules is often necessary for accurate predictions of electronic transitions [38] [39] [40].

2. Which functional and basis set should I use for simulating UV-Vis spectra? The choice depends on your system and the balance you need between accuracy and computational cost.

- Functional: The hybrid functional B3LYP is a common and validated choice for predicting the UV-Vis spectra of organic molecules with photoprotective qualities [38]. For more accurate results, especially for charge-transfer transitions or larger systems like phthalocyanines, range-separated hybrids like CAM-B3LYP are highly recommended [39].

- Basis Set: The 6-311+G(d,p) basis set is a robust choice. It includes diffusion and polarization functions, which are important for accurately modeling the electronic distribution in conjugated systems [38].

3. How can I model the effect of solvent on my UV-Vis spectrum? You can use two primary approaches:

- Implicit Solvent Models: Continuum models like IEFPCM (Integral Equation Formalism Polarizable Continuum Model) are widely used. For example, methanol (ε = 32.61) as a solvent can be effectively modeled this way [38] [40].

- Explicit Solvent Molecules: For specific solvent-solute interactions, such as hydrogen bonding (e.g., with water or N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone), you can include a few explicit solvent molecules in your calculation alongside an implicit model to capture both specific and bulk effects [40].

4. My calculated spectrum does not match my experimental data. What should I check? Begin by verifying the fundamentals:

- Geometry Optimization: Ensure your initial molecular geometry is fully optimized and confirmed to be a minimum on the potential energy surface by performing a frequency calculation (no imaginary frequencies) [38].

- Methodology Consistency: Double-check that you are using the Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT) method for excited-state calculations, not ground-state DFT [38] [39].

- Experimental Conditions: Confirm that your computational setup (especially the solvent model) matches your experimental conditions [38].

5. Are there more efficient methods for calculating spectra of large molecules? Yes, simplified TD-DFT methods (sTD-DFT) and their Tamm–Dancoff approximation (sTDA) are available. These methods can provide a significant speedup (2–3 orders of magnitude) with only a minor loss in accuracy for large systems like dyes and macrocycles, making them excellent for initial screening [39].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Self-Consistent Field (SCF) Convergence Failure

Issue: The DFT calculation fails to converge to a stable electronic energy.

Solution Protocol:

- Tighten Convergence Criteria: Increase the convergence threshold for the SCF cycle.

- Apply Level Shifting: A level shift of around 0.1 Hartree can help stabilize convergence by shifting unoccupied orbitals [37].

- Use a Hybrid Algorithm: Employ a combination of Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace (DIIS) and augmented DIIS (ADIIS) [37].

- Improve the Initial Guess: Use a better starting electron density, potentially from a calculation on a fragmented molecule or a calculation with a simpler functional.

Problem 2: Incorrect or Spurious Low-Frequency Vibrational Modes

Issue: Frequency calculations yield very low or imaginary frequencies, leading to inaccurate thermodynamic corrections.

Solution Protocol:

- Re-optimize Geometry: Ensure the geometry is a true minimum by re-running the optimization with tighter convergence criteria.

- Apply a Quasi-Harmonic Correction: For all non-transition-state modes below 100 cm⁻¹, raise the frequency to 100 cm⁻¹ specifically for the purpose of computing entropy and free energy corrections. This prevents unphysical inflation of entropic contributions [37].

Problem 3: Inaccurate Prediction of Wavelengths in the UV-Vis Spectrum

Issue: The calculated λ_max values show large deviations from experimental measurements.

Solution Protocol:

- Verify Functional and Basis Set: Switch to a range-separated hybrid functional like CAM-B3LYP, which often provides better accuracy for vertical excitation energies [39]. Ensure your basis set includes polarization and diffuse functions (e.g., 6-311+G(d,p)) [38].

- Incorporate Solvent Effects: Always include a solvent model (implicit or implicit/explicit) in your TD-DFT calculation, as the solvent environment significantly shifts excitation energies [38] [40].

- Check for State-Specific Effects: For charge-transfer states, standard functionals may be inadequate. Consider using functionals specifically parameterized for such excitations.

Problem 4: Resolving Overlapping Absorption Bands

Issue: The experimental spectrum shows overlapping absorption bands that are difficult to assign to specific electronic transitions.

Solution Protocol:

- Deconstruct with TD-DFT: Use TD-DFT to calculate the energy and oscillator strength for each individual electronic transition in the region of interest [38].

- Analyze Molecular Orbitals: For each calculated excited state, visualize the involved molecular orbitals (e.g., HOMO→LUMO) to assign the character of the transition (e.g., π-π, n-π) [40].

- Natural Transition Orbinal (NTO) Analysis: Perform an NTO analysis. This provides a more compact and chemically intuitive description of the electronic transition as a hole-electron pair, which is especially useful for complex transitions [40].

- Theoretical Spectrum Simulation: Simulate the full UV-Vis spectrum by applying a broadening function (e.g., Gaussian) to each calculated transition line based on its oscillator strength. This simulated spectrum can be directly compared to the experimental one to deconvolute the overlapping bands [38].

The following workflow outlines this computational approach to resolving overlapping bands:

Quantitative Data for Functional and Method Selection

The table below summarizes key findings from methodological surveys to guide your choice of computational method.

Table 1: Performance of different functionals and methods for predicting UV-Vis-NIR spectra of macrocycles (e.g., phthalocyanines). Adapted from [39].

| Functional | Type | Key Finding | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAM-B3LYP | Range-Separated Hybrid | Particularly accurate results for Q-band regions, recommended for sTD-DFT. | High |

| B3LYP | Hybrid GGA | Consolidated and reliable for organic molecules; good balance of cost/accuracy. | Medium |

| M06 | Meta-GGA | High sensitivity to integration grid; requires large grids for accuracy. | High |

| BP86 | GGA | Excellent for geometry optimization; less accurate for excitation energies. | Low |

| sTD-DFT | Simplified TD-DFT | 2-3 orders of magnitude speedup; excellent accuracy for large systems. | Low |

Table 2: Impact of computational parameters on DFT outcomes (based on [37]).

| Parameter | Common Error | Recommended Practice | Impact of Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Integration Grid | Using default/small grids (e.g., SG-1) | Use (99,590) grid or equivalent (e.g., dftgrid 3 in TeraChem) |

Energy & free energy inaccuracies; >5 kcal/mol error possible |

| Low-Frequency Modes | Treating quasi-free rotations as vibrations | Apply correction: set modes <100 cm⁻¹ to 100 cm⁻¹ for entropy | Inflated entropic contributions; incorrect ΔG |

| Symmetry Number | Neglecting rotational symmetry in entropy | Automatically detect point group and apply symmetry correction | Incorrect thermochemistry; error of ~RTln(2) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key materials and computational reagents for DFT-based simulation of electronic transitions.

| Item / Software | Function / Role | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian 09/16 | Quantum chemistry software for running DFT/TD-DFT calculations. | Geometry optimization, frequency, and TD-DFT analysis [38]. |

| ORCA | Quantum chemistry package with efficient TD-DFT and sTD-DFT implementations. | Predicting UV-Vis-NIR spectra of large molecules [39]. |

| GaussView | Molecular visualization and graphical interface for Gaussian. | Building molecular structures and visualizing results [38]. |

| IEFPCM Solvent Model | An implicit solvation model to simulate the effect of a solvent. | Methanol (ε = 32.61) for modeling experimental conditions [38]. |

| 6-311+G(d,p) Basis Set | A Pople-style basis set including polarization and diffuse functions. | Accurate description of conjugated systems and electronic transitions [38]. |

| Range-Separated Hybrid Functional | A type of functional to improve accuracy of charge-transfer excitations. | CAM-B3LYP for phthalocyanines and related macrocycles [39]. |

A Step-by-Step Logical Algorithm for Successful Band Resolution

In UV-Vis spectroscopy, overlapping absorption bands are a frequent challenge, especially when analyzing complex mixtures or molecules with multiple chromophores. These bands provide valuable information about the molecular structure and its environment [10]. However, their resolution is complicated because the individual bands can have different half-band widths, and their number is often difficult to estimate visually [10] [9]. This guide provides a systematic, logical algorithm to troubleshoot and resolve these overlapping bands, enabling accurate quantitative analysis of the components within a mixture.

Foundational Concepts: Why Bands Overlap

An electronic transition appears in a spectrum as an individual band, described by three fundamental parameters: its position (wavelength of maximum absorbance, λ_max), its intensity (absorbance), and its width (often measured as Full Width at Half Maximum, FWHM) [9]. Overlap occurs when the absorption bands of two or more different chemical species, or multiple transitions from the same species, are insufficiently separated in the wavelength domain. This obscures the individual contributions, making direct quantification from the composite spectrum impossible.

The Logical Algorithm for Band Resolution

The following flowchart provides a high-level overview of the systematic troubleshooting and resolution process. You can use it to diagnose your specific issue and identify the appropriate resolution technique.

Step 1: Verify Sample and Instrument Integrity

Before applying complex mathematical resolutions, rule out fundamental experimental errors.

Sample Preparation:

- Purity: Ensure your sample is not contaminated, as impurities can introduce unexpected peaks [6].

- Concentration: Excessively high concentration leads to non-linearity (deviation from the Beer-Lambert Law) and can broaden bands, exacerbating overlap. Dilute the sample to maintain absorbance ideally between 0.2 and 1.0 AU for quantitative work [19] [41].

- Solvent: Use a solvent that does not absorb significantly in your region of interest. For UV work, use quartz cuvettes, as glass and plastic absorb UV light [6] [41].

- Clarity: Turbid or cloudy samples scatter light, which violates the assumptions of the Beer-Lambert law. Filter samples to remove particulates [19].

Instrument Performance:

- Calibration: Regularly calibrate the instrument for wavelength accuracy and photometric linearity using certified standards (e.g., Holmium Oxide) [19].

- Baseline Stability: Allow the light source (especially tungsten halogen or arc lamps) to warm up for at least 20 minutes to achieve stable output and a flat baseline [6].

- Stray Light: Be aware that stray light can cause deviations in absorbance measurements, particularly at high absorbance values [19].

Step 2: Select a Resolution Method Based on Data Availability

The choice of the most efficient resolution technique depends on whether you have access to the spectra of the individual pure components.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Resolution Methods

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Equation Method (Vierordt's Method)

This classic method is used when the absorption spectra of both pure components (A and B) are known and overlap significantly.

Principle: The absorbance of a binary mixture at any wavelength is the sum of the absorbances of the two components at that wavelength. By measuring the total absorbance at two wavelengths, a system of two equations can be solved for the two unknown concentrations [28].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Select Two Wavelengths: Choose λ₁ and λ₂, typically the λ_max of each component [28].

- Determine Absorptivity Values: Using calibration curves of the pure components, determine the molar absorptivity (ε) or A(1%, 1 cm) for each component at both selected wavelengths.

- Let ( ax1 ) and ( ax2 ) be the absorptivities of component X (e.g., HCQ) at λ₁ and λ₂.

- Let ( ay1 ) and ( ay2 ) be the absorptivities of component Y (e.g., Paracetamol) at λ₁ and λ₂ [28].

- Measure Sample Absorbance: Record the absorbance of the mixture, ( A1 ) at λ₁ and ( A2 ) at λ₂.

- Solve the Simultaneous Equations:

- ( A1 = ax1 \cdot Cx + ay1 \cdot Cy )

- ( A2 = ax2 \cdot Cx + ay2 \cdot Cy )

- Where ( Cx ) and ( Cy ) are the unknown concentrations of X and Y.

- Calculate Concentrations: Solve for ( Cx ) and ( Cy ) using the following derived formulas [28]:

- ( Cx = \frac{A2 \cdot ay1 - A1 \cdot ay2}{ax2 \cdot ay1 - ax1 \cdot ay2} )

- ( Cy = \frac{A1 \cdot ax2 - A2 \cdot ax1}{ax2 \cdot ay1 - ax1 \cdot ay2} )

Protocol 2: Dual Wavelength Method

This method allows for the determination of one component in the presence of another by selecting two wavelengths where the interferent has the same absorbance.

Principle: Two wavelengths are chosen such that the difference in absorbance for the interferent component is zero, while the analyte of interest has a significant difference in absorbance. This difference is then proportional to the concentration of the analyte [28] [29].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- For Analyzing Component X in the presence of Y:

- Scan the spectrum of pure Y.

- Select two wavelengths (λ₁ and λ₂) where the absorbance of Y is equal (i.e., ( A{Y@λ1} = A{Y@λ2} )) [28].

- The difference in absorbance of the mixture at these two wavelengths is: ( ΔA{mix} = A{λ1} - A{λ2} = (A{X@λ1} + A{Y@λ1}) - (A{X@λ2} + A{Y@λ2}) ). Since ( A{Y@λ1} = A{Y@λ2} ), this simplifies to ( ΔA{mix} = A{X@λ1} - A{X@λ2} ).

- The value ( ΔA_{mix} ) is now directly proportional to the concentration of X [29]. A calibration curve of ( ΔA ) vs. concentration of pure X is used for quantification.

- For Analyzing Component X in the presence of Y:

Protocol 3: Advanced Absorbance Subtraction (AAS) and Ratio Methods

These are powerful extensions of the basic principles.

Advanced Absorbance Subtraction (AAS): This method uses an isoabsorptive point (a wavelength where both components have the same molar absorptivity) and another wavelength where one component's absorbance is canceled out. The amplitude difference between these points is used to calculate the concentration of one component, which then allows for the determination of the other [29].

Ratio Difference Method:

- Divide the absorption spectrum of the mixture by the spectrum of one of the pure components (as a divisor) to generate a ratio spectrum.

- In the ratio spectrum, the signal of the divisor component is canceled out.

- The difference in the amplitudes of the ratio spectrum at two carefully selected wavelengths will be proportional to the concentration of the other component, free from interference [28] [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Key materials and their functions in UV-Vis band resolution experiments.

| Item | Function & Importance | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Quartz Cuvettes | Holding liquid samples for analysis. Quartz is transparent across UV and visible wavelengths, unlike glass or plastic. | Path length: Typically 1 cm. Must be clean and free of scratches [6] [41]. |

| Double-Beam Spectrophotometer | Instrument for measuring absorbance. The double-beam design simultaneously measures sample and reference, compensating for source drift and ensuring a stable baseline [19]. | Wavelength Range: ~190-1100 nm. Features a monochromator (e.g., with 1200 grooves/mm) for good resolution [41]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Calibrating the spectrophotometer for wavelength accuracy and photometric linearity. | E.g., Holmium Oxide for wavelength checks. Must be traceable to standards like NIST [19]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolving samples. The solvent must not absorb significantly in the spectral region of interest. | e.g., Water, Acetonitrile, Hexane. Use HPLC or spectrophotometric grade [6] [19]. |

| Digital Software | Processing spectral data, applying mathematical transformations (derivatives, ratio, subtraction), and performing iterative fitting. | Software may be instrument-specific or third-party (e.g., Matlab, Python SciPy) for advanced deconvolution [10] [28]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)