Restoring Spectrometer Sensitivity: A Complete Guide to Diagnosing and Cleaning Dirty Optical Windows

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the prevalent issue of poor spectrometer sensitivity caused by contaminated optical windows.

Restoring Spectrometer Sensitivity: A Complete Guide to Diagnosing and Cleaning Dirty Optical Windows

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the prevalent issue of poor spectrometer sensitivity caused by contaminated optical windows. It covers the fundamental science of how dirty windows degrade data quality, outlines step-by-step cleaning and validation protocols aligned with pharmaceutical QA/QC standards, presents a systematic troubleshooting workflow to distinguish window-related issues from other instrumental problems, and discusses advanced preventative maintenance strategies and comparative analysis with other sensitivity loss factors to ensure robust, reliable spectroscopic data in biomedical and clinical research settings.

Understanding How Dirty Windows Compromise Spectrometer Sensitivity and Data Integrity

The Critical Role of Optical Windows in Light Transmission and Signal Fidelity

For researchers in drug development and analytical sciences, maintaining optimal spectrometer sensitivity is paramount. A frequent, yet often overlooked, source of signal degradation is contaminated optical windows. These components are critical for protecting the internal optics of your spectrometer. When dirty, they can scatter and absorb light, leading to diminished signal strength, unstable baselines, and inaccurate quantitative results. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and procedures to identify, rectify, and prevent issues related to optical windows, thereby safeguarding the fidelity of your spectroscopic data.

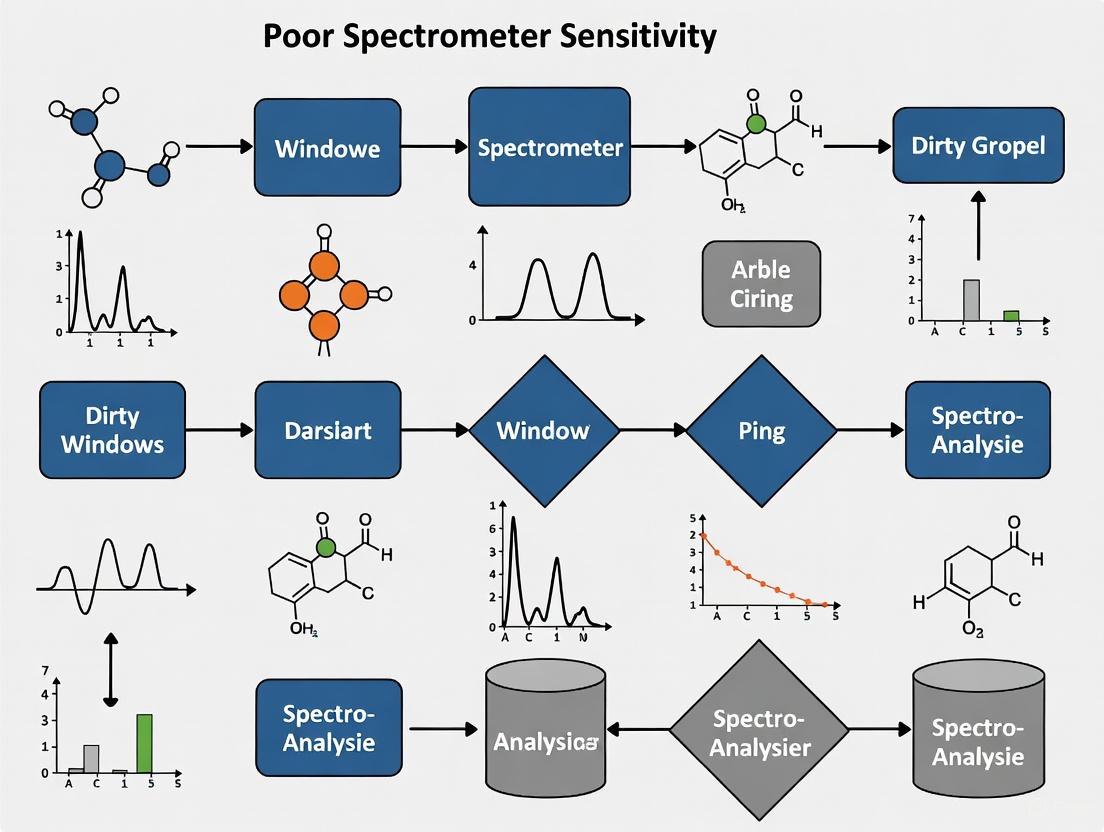

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Spectrometer Sensitivity

Use the table below to diagnose and resolve common issues stemming from compromised optical windows.

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable or Drifting Readings | - Contamination (fingerprints, dust) on the window causing light scatter [1].- Environmental factors (vibrations, temperature changes) affecting the instrument [1]. | - Clean the optical window using the detailed protocol below [1] [2] [3].- Ensure the spectrometer is on a stable, level surface away from drafts [1]. |

| Cannot Set to 100% Transmittance (Fails to Blank) | - A dirty optical window is blocking or scattering the light path [1].- The light source is nearing the end of its life [1]. | - Perform a thorough cleaning of the optical window [3].- Check the lamp usage hours in the instrument's software; replace if necessary [1]. |

| Negative Absorbance Readings | - The blank was measured with a dirtier optical surface than the sample cuvette [1]. | - Ensure all optical surfaces, including the spectrometer window and cuvettes, are cleaned uniformly before blanking [1]. |

| Generally Low Sensitivity/Weak Signal | - Significant contamination on the optical window, reducing light throughput [1] [2].- Using the wrong type of optical window material for your wavelength range (e.g., glass for UV measurements) [1]. | - Clean the optical window [2] [3].- Confirm the window material (e.g., Quartz for UV, CaF₂ for IR) is appropriate for your application [1] [2]. |

| Inconsistent Readings Between Replicates | - Gradual accumulation of residue on the window during a series of measurements. | - Clean the optical window and establish a regular cleaning schedule. Handle windows only by their edges to prevent future contamination [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can I tell if my spectrometer's sensitivity issue is caused by a dirty window and not something else?

Start with a process of elimination. First, run a blank measurement with nothing in the sample compartment. If the baseline is noisy, the 100%T line is unstable, or you cannot zero the instrument, the issue is likely with the source, detector, or internal optics. If the baseline is stable, insert a clean cuvette filled with your blank solvent. If problems arise now, the issue is with the cuvette. If the system passes both these tests but shows low signal with a known standard, a dirty internal optical window is a probable cause and should be cleaned.

Q2: What is the safest way to clean a calcium fluoride (CaF₂) optical window?

Calcium fluoride is a common material for IR and UV windows but is relatively soft and can be easily scratched. A recommended cleaning method is [2]:

- Preliminary Treatment: Gently wipe the surface with a dust-free cotton swab or optical cleaning paper soaked in reagent-grade acetone.

- Enhanced Cleaning: For stubborn contaminants, repeat the acetone wipe with a fresh swab.

- Rinse: Use a new swab lightly moistened with deionized water to remove water-soluble residues.

- Drying: Finally, wipe the surface with a swab dipped in acetone to accelerate drying and prevent water spots.

Q3: Are there any cleaning methods I should absolutely avoid?

Yes. Avoid these common mistakes to prevent permanent damage [3]:

- Do not use acetone on plastic optics or housings, as it will dissolve and damage them.

- Do not blow on an optic to remove dust, as saliva can contaminate the surface.

- Do not use ultrasonic cleaners on delicate components like diffraction gratings.

- Never apply excessive pressure while cleaning, as this can grind particles into the soft surface and cause scratches.

Q4: My spectrometer (e.g., Thunder Optics SMA) isn't calibrating properly. Could a dirty window be the cause?

Yes. The calibration process relies on measuring known light intensities. A contaminated optical window will attenuate the light signal, leading to an incorrect calibration curve and flawed intensity data in all subsequent experiments [4]. Always ensure optical windows are clean before performing any wavelength or intensity calibration.

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Cleaning Optical Windows and Lenses

This protocol is adapted from industry best practices for handling precision optics [3].

Objective: To safely remove contaminants (dust, oils, residues) from optical windows without scratching or damaging the surface.

Materials Required (The Scientist's Toolkit):

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Reagent-Grade Isopropyl Alcohol | Dissolves organic oils and residues; evaporates quickly without leaving streaks. |

| Reagent-Grade Acetone | Strong solvent for removing stubborn contaminants. Not for use on plastics. [3] |

| De-Ionized Water | Removes water-soluble contaminants; used as a final rinse after solvents. |

| Compressed Air/Dust Blower | Removes loose, abrasive dust particles before physical wiping. |

| Lint-Free Lens Tissue or Optical Wipes | Soft, non-abrasive tissue for wiping optical surfaces. |

| Cotton-Tipped Swabs | Allows for precise application of solvents and gentle wiping. |

| Powder-Free Nitrile or Latex Gloves | Prevents fingerprints and skin oils from contaminating the optic during handling. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preparation: Work on a clean, dry bench. Wear gloves and ensure all cleaning materials are within reach.

- Initial Dust Removal: Use a blast of compressed air or a dust blower to remove any loose particulate matter from the optical surface. This step is crucial to avoid grinding dust into the surface during wiping [3].

- Solvent Application: Moisten a folded piece of lens tissue or a cotton swab with a small amount of reagent-grade alcohol (or acetone, if appropriate for the material).

- Wiping Technique:

- For a lens or window held in hand, gently draw the moistened tissue across the surface in a straight line. Use a clean area of the tissue for each pass. Do not use a circular "polishing" motion, as this can redistribute contaminants [3].

- For an optic that cannot be moved, use a cotton swab. Drag the swab slowly across the surface with light pressure, turning the swab to present a clean surface as it collects contamination.

- Final Rinse (If Needed): If acetone was used, a follow-up wipe with deionized water is recommended to remove residues, followed by a final swipe with alcohol or acetone to aid in streak-free drying [2].

- Inspection: Hold the optic under a bright light and inspect it at a glancing angle. If streaks or spots remain, repeat the cleaning process with fresh materials.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for troubleshooting sensitivity issues related to optical windows.

Contaminants such as solvent residues, fingerprints, and particulates are significant yet often overlooked sources of interference in sensitive analytical techniques. Within the context of research on troubleshooting poor spectrometer sensitivity due to dirty windows, identifying and mitigating these contaminants is a critical first step. Their presence can lead to suppressed ionization, elevated baseline noise, signal interference, and irreproducible results, ultimately compromising data quality [5]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to help researchers identify, prevent, and resolve these common contamination issues.

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q: Why do I have a high background and noisy baseline in my LC-MS analysis? A: A high background is frequently caused by contaminants introduced from the mobile phase, sample, or handling. Common sources include plasticizers leaching from sample containers, impurities in solvent additives (like formic acid), microbial growth in solvent reservoirs, and compounds transferred from skin contact (such as lipids and amino acids from fingerprints) [5]. These contaminants can ionize efficiently, elevating the baseline and making it challenging to detect low-abundance analytes.

Q: My spectrometer sensitivity has suddenly dropped. What should I check first? A: Follow a systematic approach to isolate the problem:

- Check the Solvents and Additives: Prepare a fresh mobile phase using LC-MS grade solvents and additives from a reliable, dedicated source. Contaminated or low-quality formic acid is a known cause of severe signal suppression [5].

- Inspect the Instrument: For GC-MS systems, a loss of sensitivity can sometimes be traced to a worn-out filament. Switching to a second filament, if available, can restore performance [6].

- Examine Sample Preparation: Ensure you are wearing nitrile gloves to prevent contamination from fingerprints and skin [5]. Review your sample clean-up protocols to remove matrix interferences that can suppress ionization [7].

Q: I see strange peaks in my chromatogram. How can I identify if they are contaminants? A: Unexpected peaks are often exogenous contaminants. To identify them:

- Consult Contaminant Databases: Use publicly available resources that tabulate common contaminants with their mass-to-charge (m/z) values and likely sources (e.g., Triton detergents, PEG, plasticizers) [5].

- Analyze a Blank: Run a procedural blank—a sample that has undergone the same preparation process but without the analyte. Peaks present in the blank are almost certainly contaminants introduced during the workflow [5].

- Perform Sample Clean-up: Using solid-phase extraction (SPE) or desalting spin columns can remove many interfering compounds, clarifying your chromatogram [8].

Q: What is the most common source of particulate contamination, and how does it affect my system? A: Particulates can originate from dust in laboratory air, contaminated solvents, or particles from sample matrices. They can clog frits and column inlets, leading to increased backpressure and peak broadening [9]. In the context of dirty windows in optical systems, particulates can scatter light and reduce sensitivity.

Experimental Protocols for Contaminant Identification

Protocol 1: Systematic Blank Analysis to Pinpoint Contamination Source

This protocol is designed to trace the origin of contaminants within your analytical workflow.

- Preparation:

- Use only LC-MS or HPLC grade solvents.

- Wear nitrile gloves throughout the procedure to avoid fingerprint contamination [5].

- Experimental Sequence: Perform the following analyses in sequence, carefully noting any new peaks that appear:

- Blank Injection: Inject a vial of your starting mobile phase.

- Processed Blank: Inject a blank that has been processed through your entire sample preparation procedure (including any solid-phase extraction, filtration, or evaporation steps).

- System Blank: Run the LC-MS system without any injection to assess background from the instrument itself.

- Data Interpretation: Compare the chromatograms from each step. Peaks that appear in the processed blank but not the solvent blank indicate contaminants introduced during sample preparation. Peaks present in the system blank may point to a contaminated LC flow path or mobile phase.

Protocol 2: Fingerprinting Exogenous Particulates

This methodology, adapted from environmental nanoparticle research, provides a framework for characterizing unknown particulates [10].

- Sample Collection and Purification:

- Collect samples from the system of interest (e.g., a swab from a "dirty window" or a filter from a solvent line).

- Purify the sample through enzymatic hydrolysis or chemical digestion to remove adsorbed biological material.

- Multi-Fingerprinting Analysis:

- Elemental Fingerprinting: Use techniques like Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDXS) to identify the elemental composition of particulates. The presence of non-biological elements like Al, Ti, or Pt can point to abiogenic, industrial, or environmental sources [10].

- Structural Fingerprinting: Employ High-Angle Annular Dark-Field Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy (HAADF-STEM) to obtain morphological and crystallographic information about the particles at a high resolution [10].

- Source Identification: Correlate the chemical multi-fingerprints with potential sources (e.g., combustion-derived particles, catalyst residues, or construction dust) to identify the origin of the contamination [10].

Contaminant Reference Tables

| Contaminant Category | Specific Examples | Common Sources | Impact on Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvent Residues | Plasticizers (e.g., PEG), Additive impurities | Plastic solvent bottles, Low-purity mobile phase additives, Detergents from washed glassware [5] | Signal suppression/enhancement, High chemical background [5] |

| Human Residues | Lipids, Amino acids, Keratins, Salts | Handling samples/vials with bare hands, Skin contact with instrument parts [5] | Interfering peaks, Altered ionization efficiency [5] |

| Particulates | Dust, Microbes, Column frit debris | Laboratory air, Microbial growth in aqueous lines, Sample matrix [5] [9] | Clogged lines/frits, Increased backpressure, Noisy baseline [9] |

| Sample-Derived | Lipids, Proteins, Carryover | Incomplete sample clean-up, Insufficient needle wash [5] [9] | Matrix effects, Peak broadening, Contamination of subsequent runs |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity mobile phases with minimal background | Use dedicated bottles for each solvent; do not filter unless absolutely necessary to avoid introducing contaminants [5]. |

| Nitrile Gloves | Prevent introduction of biomolecules and salts from skin | Wear at all times when handling solvents, samples, vials, and instrument components [5]. |

| HeLa Protein Digest Standard | System suitability standard for LC-MS | Use to verify that sample preparation and instrument performance are not compromised by contamination [8]. |

| Peptide Desalting Spin Columns | Clean-up of peptide/protein samples | Removes salts, detergents, and other small molecule contaminants; can also remove excess labeling reagents [8]. |

| Detergent Removal Resin | Extraction of detergents from protein samples | Critical for removing ion-suppressing detergents that are incompatible with MS analysis [8]. |

| Pierce Calibration Solutions | Instrument calibration | Ensures mass accuracy is maintained, helping to correctly identify contaminants [8]. |

Contaminant Investigation Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for investigating and resolving contamination issues.

Contaminant Investigation Workflow

Advanced Contaminant Fingerprinting Strategy

For persistent or complex contamination, a formal fingerprinting strategy can be employed. The diagram below details a comprehensive analytical approach based on high-resolution mass spectrometry.

Chemical Fingerprinting Workflow

FAQs: Understanding the Impact of a Dirty Window

What symptoms indicate my spectrometer's window might be dirty? The primary symptoms of dirty optical windows on a spectrometer include signal drift, where readings consistently shift over time; poor precision, evidenced by significant variation between repeated tests on the same sample; and an elevated or noisy baseline [11] [12]. You may also find that the instrument requires more frequent recalibration [11].

How does a dirty window lead to these symptoms? Optical windows, such as those located in front of the fiber optic cable or in the direct light pipe, must be clean to allow light to pass through unobstructed [11]. Contamination on the window—such as dust, fingerprints, or residues—blocks or scatters the incoming light. This reduces the light intensity reaching the detector, leading to inaccurate measurements of light intensity and causing the symptoms of drift, poor precision, and baseline elevation [11] [13].

Which elements or measurements are most affected by this issue? While all measurements can be compromised, the low-wavelength elements are often the most sensitive to any optical path problem. These include critical elements like Carbon (C), Phosphorus (P), and Sulfur (S) [11]. Inaccurate results for these elements are a common warning sign of an issue with the optical path, which can be caused by a dirty window or a malfunctioning vacuum pump [11].

Troubleshooting Guide and Protocols

Symptom Identification Table

Use this table to quickly identify if your issues are consistent with a dirty optical window.

| Observed Symptom | Potential Cause | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Signal Drift [13] | Gradual accumulation of dirt on the window. | Measurements consistently shift in one direction (e.g., decreasing intensity) over time or between calibrations. |

| Poor Precision [11] | Contamination causing inconsistent light scattering. | High variation (e.g., Relative Standard Deviation >5) between repeated analyses of the same homogeneous sample. |

| Elevated/Noisy Baseline [12] | Dirt or stains on the window creating optical interference. | The baseline signal when no sample is being analyzed is higher than normal, chaotic, or has increased micro-peaks. |

Experimental Protocol: Cleaning Spectrophotometer Windows

This detailed methodology is adapted from standard instrument cleaning procedures [14].

Essential Materials:

- Lint-free, soft cloth (e.g., microfiber)

- Canned, dust-free compressed air (do not use a shop compressor, as it can contain moisture and oil) [14]

- Denatured or isopropyl alcohol (for stubborn contamination only) [14] [15]

- Powder-free gloves [15]

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Power Down: Turn off the spectrometer and, if applicable, unplug it. This is a critical safety step.

- Locate Windows: Identify the optical windows that require cleaning. These are typically found in the sample compartment and on the white calibration disk [11] [14].

- Initial Dust Removal: Wearing powder-free gloves, use the canned air to blow loose dust off the optical surfaces. Hold the can upright and use short bursts of air. Do not shake the can or turn it upside down during use [14].

- Inspect for Residues: Visually inspect the windows under good lighting. Look for smudges, fingerprints, or other residues.

- Clean the Surface:

- For the white calibration tile, gently wipe with a clean, lint-free cloth in circular motions. Ensure it is free of fingerprints and particles [14].

- For other optical windows, if smudges persist after dusting, apply a small amount of denatured or isopropyl alcohol to the cloth—never directly onto the instrument—and gently wipe the surface [14] [15].

- Critical: Do not use abrasive cleaners, razor blades, or coarse cloths, as these can permanently scratch the optical surfaces [15] [16].

- Final Check and Re-calibrate: Allow any residual alcohol to evaporate completely. Power the instrument back on and perform a full calibration before resuming analysis [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Maintenance Materials

Keep these items on hand for routine optical maintenance.

| Item | Function | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Lint-free Microfiber Cloth | Safely wipes away fingerprints and smudges from optical surfaces without leaving residue [14] [16]. | Avoid using lens tissues or cloths that may have been used with abrasives [15]. |

| Canned Compressed Air | Removes loose, dry dust and particulates from the aperture and hard-to-reach areas without physical contact [14]. | Must be dust-free and moisture-free. Do not use air from a standard compressor [14]. |

| Denatured / Isopropyl Alcohol | Solvent for removing stubborn, oily contaminants like fingerprints when plain wiping is insufficient [14] [15]. | Always apply to the cleaning cloth first, not directly onto the instrument. |

| Powder-free Gloves | Prevents transferring oils and fingerprints from skin onto optical surfaces and calibration standards during handling [15]. | Essential for handling any optical component or calibration standard. |

Troubleshooting Logic Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical process for diagnosing and resolving issues related to a dirty spectrometer window.

The Direct Link Between Window Cleanliness and Accurate Quantitative Analysis

Troubleshooting Guide: Symptoms of Dirty Spectrometer Windows

Dirty or contaminated optical windows are a common, yet often overlooked, source of error in spectroscopic quantitative analysis. Contaminants such as dust, fingerprints, and residue can significantly degrade data quality. The following table outlines common symptoms, their impact on data, and the underlying causes related to window cleanliness.

| Observed Symptom | Impact on Quantitative Analysis | Link to Window Contamination |

|---|---|---|

| Calibration Drift [11] | Frequent need for recalibration; loss of historical data comparability. | A dirty window attenuates light, causing a gradual shift in the instrument's baseline response over time. |

| Poor Analysis Readings [11] | Inaccurate concentration values for analytes. | Contamination scatters and absorbs light, leading to incorrect intensity measurements used for quantification. |

| Low Light Intensity/Inaccurate Readings [11] | High variability between replicate measurements of the same sample. | Inconsistent light transmission due to uneven contaminant layers causes poor measurement reproducibility. |

| Increased Signal Noise/Unstable Readings [1] | Reduced confidence in detecting low-concentration analytes. | Particulates on the window can scatter light, contributing to a noisy signal and raising the effective detection limit. |

| Negative Absorbance Readings [1] | Theoretically impossible results, indicating a fundamental measurement error. | Can occur if the blank measurement was performed with a contaminated optical path, making the sample appear "cleaner" than the blank. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which specific windows in a spectrometer are most critical for maintaining cleanliness? Two windows are paramount for accurate analysis. The first is the window located in front of the fiber optic cable, and the second is the window in the direct light pipe [11]. Contamination on either of these surfaces will directly interfere with the light path used for measurement.

Q2: How do contaminants on the window lead to inaccurate quantitative results? Quantitative analysis relies on measuring the precise intensity of light interacting with a sample. Contaminants on optical windows absorb and scatter this light, reducing the total light throughput [11]. This reduction in light intensity is misinterpreted by the instrument's software, leading to incorrect calculations of element or compound concentration. For elements measured in lower wavelengths, like Carbon and Phosphorus, this effect is particularly pronounced [11].

Q3: What is the recommended method for cleaning spectrometer windows? The universal and safest first step is to use dust-free compressed air or a blower bulb to remove loose particulate matter [17] [18] [19]. Never touch or wipe the window with anything without first blowing off dust, as this can grind particles into the surface and cause scratches [19]. For more persistent contaminants, consult the manufacturer's manual; some may recommend gentle cleaning with appropriate solvents, but this is not universally advised for all windows [17].

Q4: Can I use a lens tissue or a standard microfiber cloth to clean the windows? No, this is generally not recommended. Standard microfiber cloths and lens tissues can smudge or even scratch delicate optical glass [18]. The only user-level cleaning method advised is with compressed air. Any physical wiping should only be performed by trained personnel using specified materials, such as pure cotton wipes (e.g., Webril Wipes) and optical-grade solvents, if the manufacturer's procedure allows it [19].

Q5: How often should I inspect the spectrometer's windows for cleanliness? Inspect the windows visually before starting any critical quantitative work. The frequency of formal cleaning depends on the operating environment. A device in a clean, climate-controlled lab may require less frequent attention, while one in a factory with airborne contaminants may need daily checks [20] [21].

Experimental Protocol: Inspection and Cleaning of Optical Windows

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for the safe inspection and cleaning of spectrometer optical windows to restore and maintain analytical sensitivity.

Materials and Equipment

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Powder-free Gloves | Prevents transfer of skin oils to optical surfaces during handling [18] [19]. |

| Dust-Free Compressed Air / Blower Bulb | Primary tool for removing loose, dry particulates without physical contact [17] [18]. |

| Handheld Magnifier or Microscope | For detailed visual inspection of the window surface for fine contaminants and damage [19]. |

| Bright Light Source | Helps reveal contaminants and streaks by increasing the intensity of specular reflections [19]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Safety and Preparation: Turn off the spectrometer and disconnect the power supply [17]. Ensure you are working in a clean, well-lit, and stable environment.

- Initial Visual Inspection: While wearing powder-free gloves, visually inspect the window. Hold the window at an angle to your line of sight to see reflections from contaminants [19].

- Dry Gas Cleaning:

- Post-Cleaning Inspection: Re-inspect the window using the bright light source and magnifier. If contaminants remain, do not proceed to wiping. Contact qualified technical support, as further cleaning may require specialized tools and solvents to avoid permanent damage [17] [19].

Diagnostic Workflow for Sensitivity Loss

The following diagram outlines a logical troubleshooting pathway to systematically determine if dirty windows are the root cause of poor spectrometer sensitivity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Sensitivity Loss in Gas Chromatography (GC)

Loss of sensitivity in GC analyses is a common challenge that can significantly impact the accuracy of concentration assays. The troubleshooting approach depends heavily on the specific symptoms observed in your chromatogram. The table below categorizes common symptoms, their likely causes, and recommended corrective actions [22].

| Symptom Category | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| All peaks are smaller; retention times unchanged [22] | Incorrect instrument settings, autosampler issues, depleted detector gases, or a dirty MS ion source [22] [6]. | Verify inlet split ratio, detector temperature, and autosampler syringe function [22]. For MS, check tune report for increased repeller or EM voltage indicating a dirty source [22] [6]. Check fuel gas ratios for flame-based detectors [22]. |

| All peaks are smaller and broadened [22] | Loss of chromatographic efficiency [22]. | Confirm correct column dimensions and carrier gas flow in method [22]. Trim the inlet end of the column by 0.5–1 meter [22]. Check column installation depth into inlet/detector [22]. |

| Reduced sensitivity for late-eluting peaks [22] [23] | Sample discrimination against high-boiling-point compounds, often due to injection technique or liner geometry [22]. | Ensure fast syringe plunger speed for liquid injection [22]. Verify correct liner is installed, ideally with deactivated glass wool packing [22]. Check for leaks, over-tightened ferrules, or incorrect column positioning in the inlet [23]. |

| Specific peaks are smaller [22] | Chemical degradation or adsorption of specific analytes [22]. | Investigate analyte stability in the sample matrix and solvent [22]. Check for active sites in the flow path (liner, column) that may adsorb certain functional groups [22]. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Low Recovery in Dissolution Testing

Low drug recovery in dissolution testing can lead to inaccurate assessments of product performance and quality. The following workflow and table help diagnose the root cause, which often involves drug adsorption or instability [24].

Figure 1: Diagnostic workflow for troubleshooting low recovery in dissolution testing, based on [24].

| Observation | Indicated Problem Area | Specific Checks & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low recovery with autosampler, but acceptable with manual sampling. | The autosampler flow path, typically peristaltic pump tubing or residual film from inadequate cleaning [24]. | Switch to alternative tubing chemistry (e.g., Marprene). Perform several cleaning cycles with a water-alcohol mixture to remove residual excipients [24]. |

| Low recovery with both autosampler and manual sampling. | Filter adsorption or binding to the stainless-steel components of the dissolution apparatus itself [24]. | Validate filter adsorption using a defined procedure. If confirmed, switch to a different filter type. If binding to stainless steel is suspected, use alternative materials like PEEK cannulas or Diamond-Like Carbon (DLC) coated paddle shafts [24]. |

| Failed dissolution specification for gelatin capsules during stability studies. | Gelatin cross-linking, which makes the capsule shell insoluble [25]. | Add the appropriate enzyme (e.g., pepsin in acidic media, pancreatin in neutral media) to the dissolution medium to digest the cross-linked gelatin. A pre-treatment step without surfactant may be needed to protect enzyme activity [25]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My GC-MS sensitivity has dropped significantly, and the autotune shows a higher than normal repeller voltage and electron multiplier (EM) voltage. What is the most likely cause? [6]

A1: A simultaneous increase in both the repeller and EM voltages in the tune report is a strong indicator of a dirty ion source. Contamination on the source components reduces their ability to efficiently focus and transmit ions, forcing the instrument to compensate by increasing these voltages. The first course of action should be a thorough cleaning and reconditioning of the ion source [6].

Q2: When should enzymes be used in the dissolution testing of gelatin capsules, and is this required for routine batch release? [25]

A2: Enzymes should only be added to the dissolution medium when there is evidence of gelatin cross-linking, which can occur during stability studies under high temperature and humidity. Enzymes are not required for routine batch release testing unless cross-linking is suspected or observed. The enzyme is selected based on the pH of the dissolution medium, and its activity must be verified according to the procedure in USP general chapter <711> [25].

Q3: What is the recommended sampling method for manual dissolution sampling, and why? [25]

A3: The recommended method is to use a syringe with an L-shaped cannula. This setup allows for easy and consistent sampling from the official sampling zone within the vessel without having to stop the agitation. After withdrawal, the sample should be filtered immediately to separate any undissolved particles and stop the dissolution process [25].

Q4: If a dissolution test fails the first stage (L1) of acceptance criteria, should a laboratory investigation be triggered immediately? [25]

A4: No. The three stages (L1, L2, L3) outlined in the USP <711> acceptance table are considered part of a single test. A formal laboratory investigation for an Out-of-Specification (OOS) result is typically initiated only if the batch fails the final stage (L3). However, a manufacturer's internal quality policy may dictate more specific rules [25].

Q5: For a chewable tablet, are both disintegration and dissolution tests required? [25]

A5: Yes. According to FDA guidance, both disintegration and dissolution tests are required for chewable tablets. This is also noted in USP general chapter <1711> "Oral Dosage Forms - Performance Tests" [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| Deactivated Glass Wool | Liner packing in GC inlets; promotes complete vaporization of the sample and traps non-volatile residues [22]. |

| PEEK Cannulas & DLC Coatings | Inert alternatives to stainless steel for dissolution apparatus components (paddles, shafts, cannulas) to prevent drug adsorption [24]. |

| Enzymes (Pepsin, Pancreatin) | Added to dissolution media to digest cross-linked gelatin in capsule shells, ensuring the capsule contents are released [25]. |

| Marrene Tubing | A specific type of tubing for peristaltic pumps in automated dissolution samplers, chosen for its low binding properties for certain drugs [24]. |

| Performance Verification Standards | USP-calibrated tablets (e.g., prednisone) used in the "chemical calibration" of dissolution apparatus to ensure system suitability [26]. |

Proven Cleaning Protocols and Best Practices for Pharmaceutical QA/QC

Step-by-Step Guide to Safe Window Inspection and Removal

Within spectrometer systems, optical windows serve as critical interfaces, protecting sensitive internal optics from the external environment while allowing light transmission for accurate measurements. Contamination or damage to these windows is a prevalent cause of signal degradation, leading to poor sensitivity, analytical drift, and unreliable data [11] [27]. This guide provides a systematic, question-and-answer format for the safe inspection, cleaning, and handling of spectrometer windows to maintain optimal instrument performance in research and drug development.

FAQs on Spectrometer Window Contamination

1. What are the common symptoms of a dirty or contaminated spectrometer window?

The symptoms often include a gradual drift in instrument calibration, necessitating more frequent recalibrations [11]. Analytically, you may observe consistently low or unstable readings for certain elements, particularly those measured at lower wavelengths [11]. A general loss of signal intensity and poor reproducibility of results on the same sample are also key indicators [11].

2. How can I visually inspect my spectrometer's windows for contamination?

Begin by turning off the spectrometer and disconnecting the power to ensure safety [17] [28]. Use a bright, oblique light source to illuminate the window surfaces. Look for signs of dust, fingerprints, oily films, or any discoloration [11]. For more advanced analysis, techniques like Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) can be used to detect and quantify trace surface contaminants that are not visible to the naked eye [27].

3. What is the safest method to clean optical windows?

The universal rule for optical windows is to avoid physical contact. Never wipe a window, as this can scratch the soft optical material [17] [28]. For dust, use a gentle stream of clean, dry, oil-free air or nitrogen to blow the particles away [17] [28]. If a more thorough cleaning is necessary, it must be performed with extreme caution using specialized protocols for the specific window material (see Experimental Protocols below). Manufacturer guidelines consistently warn against allowing any liquid to come into contact with optical components within the sample compartment [17] [28].

4. My spectrometer has poor sensitivity after cleaning. What could have gone wrong?

The most likely cause is damage to the window during cleaning. Scratching from abrasive cloths or chemical etching from inappropriate solvents can permanently degrade optical performance [29]. Another possibility is the introduction of a new contaminant, such as residue from a cleaning solvent or oils from skin contact if the window was handled directly [11] [29]. Always use forceps or lint-free gloves when handling optical components [30].

5. When should a window be removed or replaced instead of cleaned?

Consider replacement if visual inspection reveals any scratches, pits, or cracks on the window surface [29]. If sensitivity does not improve after a safe cleaning procedure, the window may have sustained permanent damage or the issue may lie elsewhere in the optical path [31]. Replacement is also necessary if the window is fractured, as this will completely compromise the instrument's vacuum and optical integrity [31].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Routine Inspection and Dry Cleaning of Optical Windows

This non-invasive method is the first and most frequent step in window maintenance.

- Objective: To safely remove loose particulate contamination without risking damage to the window.

- Materials Needed: Lint-free nylon gloves [30], a source of clean, dry, oil-free compressed air or nitrogen [17] [28].

- Procedure:

- Power down the spectrometer and disconnect it from the main power supply [17] [28].

- Don lint-free gloves to prevent transferring skin oils to the instrument [30].

- Open the sample compartment to access the optical windows.

- Visually inspect the windows using an oblique light source.

- Using the stream of compressed air or nitrogen, gently blow across the window surface to dislodge dust. Do not allow the air nozzle to touch the window.

- Close the compartment and reconnect the power.

Protocol 2: Acid Washing of Calcium Fluoride (CaF₂) Windows

This aggressive cleaning method should be used sparingly and only for severe organic contamination on CaF₂ windows, as it can cause pitting [29].

- Objective: To remove tenacious organic contaminants from CaF₂ windows via oxidation.

- Materials Needed:

- Procedure:

- Prepare the acid wash: In a fume hood, dissolve a few small crystals (≈5) of KMnO₄ into a small beaker containing no more than 20 mL of sulfuric acid. The solution should turn green, not dark green. CAUTION: This is a strong oxidizer and can cause fire or explosion. [29]

- Clean the window: Using forceps, gently immerse one CaF₂ window into the permanganic acid for no more than 10-15 seconds [29].

- Rinse: Remove the window and immediately place it into a tube halfway filled with water. Repeat for the second window. Then, transfer both windows to a second tube with clean water for a more thorough rinse [29].

- Neutralize waste: Carefully pour the contents of the first rinse tube and the spent acid into a large beaker of water. Slowly add soda ash to neutralize the solution before disposal [29].

- Final rinse and dry: Rinse the windows thoroughly with deionized water and dry completely using a stream of pressurized air [29].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Common Contaminants and Their Impact on Optical Properties

| Contaminant Type | Source | Primary Impact on Signal |

|---|---|---|

| Fingerprints, Skin Oils [11] [17] | Improper handling | Scattering, reduced transmission, introduces hydrocarbons for analysis [11] |

| Polishing Residues [27] | Manufacturing process | Can alter the effective index of refraction, causing measurement drift [27] |

| Dust & Particulates [32] | Environment | Light scattering, increased haze, potential for localized heating [32] |

| Rubidium Silicate Layer [32] | Chemical reaction in vapor cells | Strong absorption, significant loss of transparency, wavefront distortion [32] |

| Molecular Film (Outgassing) [33] | Non-metallic materials (seals, O-rings) | Increased haze, reduced transmission over time [33] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for inspecting and addressing window-related issues in a spectrometer.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Materials for Window Inspection and Cleaning

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lint-Free Gloves [30] | Prevents transfer of skin oils and particulate matter to optical surfaces during handling. | Nylon or nitrile gloves are suitable. Avoid powdered gloves. |

| Compressed Air / Nitrogen [17] [28] | Removes loose, particulate contamination without physical contact with the window. | Must be clean, dry, and oil-free. Use a gentle stream. |

| Forceps [29] | Allows for safe handling of small or fragile windows during cleaning procedures. | Use tips coated with a soft, non-scratching material. |

| Sulfuric Acid & KMnO₄ [29] | Forms a potent oxidizing solution (permanganic acid) for removing organic contaminants from CaF₂. | Highly hazardous. Use only in a fume hood with full PPE for brief immersion. |

| Micro Mesh Abrasive Sheets [30] | Provides a fine, graded abrasive for hand-polishing metal source components (not the optical windows themselves). | Used for restoring a mirror finish on stainless steel parts in mass spectrometer sources. |

| Solvents (e.g., High-Purity Methanol) | Can be used for cleaning certain non-optical metal parts and for final rinsing in some protocols. | Never use on optical windows unless specified by the manufacturer, as solvents can damage coatings. |

Within the context of research on troubleshooting poor spectrometer sensitivity, maintaining pristine optical components is a critical factor for data integrity. Dirty windows on spectrometers are a common source of analytical drift, increased recalibration frequency, and poor sensitivity, ultimately compromising experimental results [11]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and protocols for selecting cleaning solvents to effectively restore and preserve optical performance.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

How does a dirty optical window affect my spectrometer's sensitivity?

A dirty window directly compromises sensitivity by reducing light throughput and causing scattering, which leads to signal loss and increased noise [11]. The instrument's analysis will begin to drift, requiring more frequent recalibration and resulting in poor or inconsistent analytical readings [11]. For elements measured at lower wavelengths, such as Carbon, Phosphorus, and Sulfur, this can manifest as consistently low readings [11].

What are the symptoms of a contaminated sample, and how can I prevent it during preparation?

Contamination presents as inconsistent or unstable results and can originate from improper sample handling [11]. To prevent it:

- Regrind Samples: Use a new grinding pad to remove plating, carbonization, or protective coatings before analysis [11].

- Avoid Re-contamination: Do not quench samples in water or oil, and avoid touching the sample with your fingers, as skin introduces oils and grease [11].

- Ensure Homogeneity: Inadequate sample preparation causes heterogeneity, which is a primary source of spectroscopic analytical errors [34].

What is the proper methodology for cleaning spectrometer windows?

The following protocol outlines the essential steps for safe and effective cleaning. Always prioritize manufacturer instructions, as specific coatings or materials may require specialized care.

How can I verify that my cleaning procedure was successful?

Post-cleaning verification is crucial. A successful cleaning is confirmed by:

- Visual Inspection: The window should be free of any visible streaks, film, or residue when examined under a bright light [1].

- Instrument Performance: The spectrometer should demonstrate a stable baseline and a return to expected sensitivity levels during a system performance check [1]. Advanced verification can involve techniques like Raman spectroscopy to confirm the absence of contaminant residues, as demonstrated in laser cleaning studies [32].

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Verification of Cleaning Efficacy via UV Spectrometry

This protocol is adapted from in-line cleaning validation studies in biopharmaceutical manufacturing and can be applied to verify the cleanliness of rinse solvents or surfaces in a lab context [35].

- Objective: To quantify the removal of residual contaminants or cleaning agents from a surface by analyzing the rinse solvent using UV spectroscopy.

Materials and Equipment:

- UV spectrophotometer

- High-purity quartz cuvettes (e.g., 10 mm pathlength) [35]

- Lint-free wipes

- High-purity solvents (see table below)

- Type 1 (Ultrapure) water

Procedure:

- Establish a Blank Baseline: Using a meticulously cleaned cuvette, record the UV spectrum (e.g., from 190–400 nm) of your clean rinse solvent (e.g., Type 1 water) as a blank [35].

- Generate a Calibration Curve: Prepare a series of standard solutions of the target contaminant (e.g., a specific cleaning agent or a model soil like Bovine Serum Albumin) in the rinse solvent. Measure the absorbance of each standard at a predetermined wavelength (e.g., 220 nm for many cleaners) and plot concentration versus absorbance to create a calibration curve [35].

- Sample the Rinse Solvent: After the cleaning procedure, collect the final rinse solvent used on the component.

- Analyze the Sample: Measure the absorbance of the collected rinse solvent at the same wavelength used for calibration.

- Quantify Residue: Calculate the concentration of the residual contaminant in the rinse sample using the calibration curve. A concentration below a pre-defined acceptance limit (e.g., based on the instrument's Limit of Detection (LOD)) confirms effective cleaning [35].

Data Interpretation: The method's sensitivity can be enhanced by using a cuvette with a longer pathlength, as absorbance is proportional to pathlength per the Beer-Lambert law [35]. This approach provides quantitative, rather than just visual, confirmation of cleaning success.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions for Spectroscopic Cleaning

The following table details key materials essential for effective and safe cleaning of spectroscopic components.

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents | To dissolve and remove specific contaminants without leaving residues. Isopropyl alcohol is effective for oils; acetone for organics. Always use spectroscopic or HPLC grade to prevent introducing new contaminants that can deposit on optics [36] [35]. |

| Lint-Free Wipes | To apply solvent and mechanically remove contamination without shedding fibers that can scatter light or scratch surfaces [37]. |

| Spectrophotometric Grade Solvents | For critical applications where ultra-high optical clarity is required. These are specially purified to have ultra-low absorbance and background interference, ensuring they do not contribute to spectral noise [36]. |

| Compressed Dust-Off Gas | To remove loose particulate matter from surfaces before wet cleaning, preventing abrasive scratches [1]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Required for UV range verification methods (<340 nm). Standard glass or plastic cuvettes absorb UV light and will yield incorrect results [1]. |

Key Compatibility and Purity Considerations

The core principle of selecting a cleaning solvent is compatibility. The solvent must effectively dissolve the contaminant without damaging the optical substrate (e.g., quartz, glass, specialized coatings). Simultaneously, the purity of the solvent is non-negotiable. Low-grade solvents contain volatile impurities that can evaporate and form a thin film on the optical surface, directly causing the sensitivity issues you are trying to resolve [36] [1]. Always consult your spectrometer's manufacturer guidelines for approved cleaning agents and methods to avoid damaging sensitive components.

Within spectrometer-based research, maintaining optimal instrument sensitivity is paramount. A frequent, yet often overlooked, cause of declining sensitivity is contaminated optical surfaces. Dirty windows scatter and absorb light, leading to signal loss, analytical drift, and poor reproducibility [11]. This guide details proper cleaning techniques to preserve optical integrity, ensure measurement accuracy, and maintain the performance of your spectroscopic systems.

FAQs: Optical Contamination and Spectrometer Sensitivity

Q1: How does a dirty optical window specifically affect my spectrometer's sensitivity?

Contamination on optical windows, such as dust, oils, or residues, directly interferes with light transmission. This leads to:

- Signal Loss: Dirt blocks or scatters light, reducing the intensity that reaches the detector [11].

- Increased Noise: Inconsistent contamination can cause signal drift and elevated baseline noise [11].

- Inaccurate Calibration: The instrument may require more frequent recalibration, and analyses can show poor precision and unstable results [11].

Q2: What are the two critical windows on a spectrometer that require regular cleaning?

According to troubleshooting guides for optical emission spectrometers (OES), the two windows that need regular attention are [11]:

- The window located in front of the fiber optic cable.

- The window located in the direct light pipe.

Q3: Are all optical wipes created equal?

No, wipes are designed for different purposes and cleanliness levels. The table below summarizes key types:

Table 1: Types of Optical Cleaning Wipes and Their Applications

| Type | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Lens Tissue [38] [39] | Extremely soft, premium grade, low-lint, and free from contaminants and adhesives. Meets specific government specifications (e.g., A-A-50177B). | Manual cleaning of high-grade optics; wrapping optics for storage. |

| Optical Cleaning Pads [38] | Pure cotton, non-woven, low-lint, and highly absorbent. Larger size allows for a single, continuous wipe. | Cleaning larger or curved optical surfaces like lenses. |

| Precision Lens Cleaning Wipes [38] | Low-lint, durable materials like polypropylene. Some versions are pre-saturated with a 70% IPA/30% deionized water solution [39]. | Quick, convenient cleaning of optics in labs and production environments. |

| Microfiber Cloths [39] | Durable, reusable, and employ advanced microfiber technology for effective debris and moisture removal. | General cleaning of uncoated optics; suitable for delicate surfaces. |

Essential Cleaning Protocols

General Step-by-Step Guide for Cleaning Optical Windows

Diagram: Logical workflow for properly cleaning spectrometer optics.

- Inspect: Visually examine the optic under good lighting. Use a magnifier if necessary to identify contamination type (dust, fingerprints, etc.) [1].

- Dry Removal: Use a can of compressed gas or a duster to remove loose, dry particulate matter. This prevents scratching during the wet-cleaning step [38].

- Apply Solvent: Moisten a fresh, lint-free wipe or cotton-tipped applicator with an appropriate solvent (e.g., high-purity isopropyl alcohol, methanol, or lens-cleaning fluid). Do not pour solvent directly onto the optic [38].

- Wipe Gently: While holding the optic securely, gently wipe the surface using a circular motion, working from the center outward. Use minimal pressure [1].

- Dry: Use a fresh, dry, lint-free wipe or swab to gently remove any remaining solvent, preventing residue formation [1].

- Final Inspection: Re-inspect the optic to ensure it is clean and free of streaks, fibers, and residue.

Specialized Cleaning Methods

- Polymer Cleaning: For delicate optics or stubborn nanoparticles, a special polymer solution (e.g., First Contact) can be applied. It forms a film that encapsulates contaminants, which is then peeled off, lifting the debris away without mechanical contact [38].

- Ultrasonic Cleaning: This method uses high-frequency sound waves in a liquid bath to remove contaminants. The choice of cleaning liquid is critical and depends on the contaminant and the optic's material compatibility [40]. Common liquids include:

- Water-based solutions with detergents for general cleaning.

- Solvent-based solutions (e.g., isopropyl alcohol) for oils and greases [40].

- Deionized water is often recommended as a final rinse to prevent water spots.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Cleaning Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Cleaning

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Lint-Free Wipes [38] [39] | To physically remove contamination without introducing new particles (lint). | Select grade (commercial, industrial) based on optical sensitivity. |

| Cotton-Tipped Applicators [38] | To clean confined areas or small optical surfaces where wipes are impractical. | Ensure the cotton is securely attached to the stick. |

| High-Purity Solvents (Isopropyl Alcohol, Methanol) [38] [40] | To dissolve organic contaminants like oils and fingerprints. | Use spectroscopic grade to avoid residue. Test compatibility with optical coatings. |

| Compressed Gas Duster [38] | To remove dry, loose abrasive particles before wet cleaning. | Hold the can upright to avoid ejecting liquid propellant. |

| Polymer Cleaning Kit [38] | To safely clean fragile optics or remove nanoparticles without scratching. | Follow manufacturer instructions for application, drying, and peeling. |

Safety and Handling of Optical Components

Many materials used in spectrometer windows (e.g., in FTIR) are toxic and require careful handling [41].

- Hazardous Materials: Be aware of common but hazardous optical materials:

- KRS-5: Contains thallium. Do not polish as the powder is highly toxic if inhaled [41].

- Zinc Selenide (ZnSe): Reacts with acids to produce toxic hydrogen selenide gas. Use only with samples in a pH range of 6.5 to 9.5 [41].

- Barium Fluoride (BaF2): Reacts with acid to produce harmful hydrogen fluoride gas [41].

- Procedures: Always consult Material Safety Data Sheets (MSDS) for handling, storage, and disposal information. Store poisonous or deleterious substances in locked cabinets with proper labeling [41].

Establishing a Preventive Maintenance Schedule for Continuous Performance

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Spectrometer Sensitivity Due to Dirty Windows

Q: How do dirty windows affect my spectrometer's sensitivity and results?

A: Dirty windows on a spectrometer directly lead to a loss of light intensity reaching the detector. This manifests as instrumental drift, necessitating more frequent recalibration and resulting in poor analysis readings and unreliable data [11]. In the context of your research on sensitivity, this is a primary physical cause of signal degradation.

Q: Which windows are critical to clean, and what are the symptoms of contamination?

A: Two primary windows require regular attention [11]:

- The window in front of the fiber optic cable.

- The window in the direct light pipe. Symptoms include consistent downward drift in calibration curves, lower-than-expected signal intensity (affecting sensitivity), and increased noise in measurements [11].

Q: What is the step-by-step protocol for cleaning spectrometer windows?

A: While specific procedures can vary by instrument, the general methodology is as follows.

- Step 1: Power off the spectrometer and allow it to cool if it has been in recent use.

- Step 2: Gently remove the window or access cover according to the manufacturer's instructions. Handle components with gloves to avoid transferring oils.

- Step 3: Clean the optical surfaces using lint-free wipes or swabs specified for optics [42].

- Step 4: Use a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol, isopropyl alcohol) as recommended by the manufacturer. Apply the solvent to the wipe, not directly onto the window, to prevent seepage into other components.

- Step 5: Wipe the optical surface gently in a circular motion. Do not apply excessive pressure.

- Step 6: Inspect the window under a light for any remaining smudges or particles. Repeat cleaning if necessary.

- Step 7: Re-install the window carefully, ensuring proper alignment and sealing.

Guide 2: General Spectrophotometer Troubleshooting for Sensitivity Issues

Q: My readings are unstable or drifting. What should I check first?

A: Instability can have several common causes. Follow this troubleshooting guide [1]:

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable/Drifting Readings | Instrument lamp not stabilized. [1] | Allow a 15-30 minute warm-up time before use. [1] |

| Sample is too concentrated. [1] | Dilute sample to an absorbance within the ideal 0.1–1.0 AU range. [1] | |

| Air bubbles in the sample. [1] | Gently tap the cuvette to dislodge bubbles. [1] | |

| Environmental vibrations or drafts. [1] | Move the instrument to a stable, vibration-free location. [1] | |

| Cannot Set 100% Transmittance | Light source (lamp) is failing. [1] [43] | Check lamp usage hours; replace if near or beyond its rated life. [42] [1] |

| Dirty or misaligned internal optics. [1] | Clean external windows; for internal optics, contact qualified service personnel. [11] [1] | |

| Negative Absorbance Readings | The blank was "dirtier" than the sample. [1] | Always use the same cuvette for blank and sample measurements. [1] |

| The cuvette was dirty during blanking. [1] | Re-clean the cuvette and perform a new blank measurement. [1] |

Q: My instrument fails to zero. Is this a hardware failure?

A: Not necessarily. First, check these points [1]:

- Sample Compartment Lid: Ensure the lid is fully closed, as external light leakage will prevent zeroing.

- Humidity: High humidity can affect internal components. Ensure the instrument is in a controlled environment and that any built-in desiccant is still active.

- Reset: Perform a power cycle by turning the instrument off and on again.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: How often should I replace the light source (lamp) on my UV-Vis spectrophotometer?

A: Lamps have a finite lifespan. Deuterium (D2) and Tungsten-Halogen (WI) lamps typically require replacement after approximately 2,000 hours of use, even if they are still illuminating, as their output degrades [42]. For some process analyzers, a 6-month replacement schedule for tungsten-halogen lamps is recommended to prevent unexpected failure and ensure peak performance [44]. Consistently low light intensity or failure to set 100% transmittance are key indicators of a failing lamp [1].

Q: What is the single most important practice for ensuring consistent, sensitive measurements?

A: Proper cuvette handling and blanking. Always [1]:

- Handle cuvettes by the frosted or ribbed sides only.

- Wipe clear optical surfaces with a lint-free cloth before each measurement.

- Use the exact same cuvette for both your blank and sample measurements.

- Ensure your blank solution is the same solvent or buffer as your sample.

Q: We use an FTIR. Are there special safety concerns with window materials?

A: Yes. Certain common FTIR window materials require specific safety precautions due to their toxicity [41]. Key examples are listed in the table below.

| Material | Key Safety Hazards | Handling & Disposal Precautions |

|---|---|---|

| KRS-5 (Thallium Bromide/Iodide) | Toxic; inhaling polishing powder can cause intoxication. [41] | Users must not attempt to polish. Subject to MSDS requirements. [41] |

| Zinc Selenide (ZnSe) | Poisonous substance; reacts with acids to produce toxic hydrogen selenide. [41] | Use only with samples in pH range 6.5-9.5. Requires controlled storage and disposal as a poisonous substance. [41] |

| Barium Fluoride (BaF2) | Deleterious substance; produces harmful hydrogen fluoride gas if heated or in contact with acid. [41] | Avoid contact with acids. Requires controlled storage and disposal as a deleterious substance. [41] |

Always consult the Material Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) for specific handling, storage, and disposal instructions [41].

Preventive Maintenance Schedule and Materials

A proactive maintenance schedule is crucial for preventing sensitivity issues and unplanned downtime. The following table provides a general guideline. Always refer to your specific instrument's manual for the manufacturer's recommended procedures.

Preventive Maintenance Schedule

| Component | Maintenance Task | Frequency | Key Performance Indicator / Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | Inspect output; Replace lamp [42] [44] | Every 2,000 hours or 6 months (varies by instrument) [42] [44] | Unstable baseline; failure to set 100%T; noisy spectra [1] |

| Optical Windows | Clean with lint-free wipes and appropriate solvent [11] [42] | Weekly or as needed (visual inspection) | Signal drift; need for frequent recalibration [11] |

| Cuvettes | Inspect for scratches/contamination; Clean [42] [1] | Before every use | Scratches scatter light; residue causes contamination [42] |

| Environmental Check | Ensure stable, vibration-free, dust-free environment [42] [1] | Daily (placement) | Drifting readings; unstable signal [1] |

| Full Calibration | Perform multi-point calibration with standards | Monthly or Quarterly (based on use and requirements) | Ensures quantitative accuracy and compliance [11] |

| Professional Service | Full optical inspection and alignment by qualified technician [42] | Annually | Maintains instrument specification and data integrity [42] [45] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Importance in Maintenance |

|---|---|

| Certified Quartz Cuvettes | Essential for UV range measurements (below ~340 nm). Must be free of scratches and cracks to avoid light scattering and erroneous absorbance values [42] [1]. |

| Lint-Free Wipes / Swabs | Used for cleaning optical windows and cuvettes without leaving fibers that can scatter light or cause contamination [42]. |

| Optical Cleaning Solvent | High-purity solvents (e.g., methanol, isopropanol) for dissolving contaminants on optical surfaces without leaving residues [41]. |

| Deuterium (D2) & Tungsten-Halogen Lamps | Standard light sources for UV-Vis spectrophotometers. Their timely replacement is critical for baseline stability and signal intensity [42]. |

| Certified Calibration Standards | Stable, traceable materials (e.g., holmium oxide for wavelength calibration, neutral density filters for photometric accuracy) used to verify instrument performance [43]. |

| Source Mirror | A consumable optical component in the lamp compartment that ensures optimal reflection and light intensity; may require cleaning or replacement during PM [42]. |

Workflow and Procedures

Experimental Protocol: Verifying Sensitivity and Quantitation Limits

This protocol, adapted from pharmaceutical cleaning validation, provides a detailed methodology to verify that your spectrometer can quantitate down to the required sensitivity level, which is critical after performing maintenance or when establishing a new method [46].

Objective: To determine the quantitation limit of an analyte on your spectrometer, ensuring it can detect residues at the required sensitivity.

Materials:

- Standard sample of the analyte (e.g., acetylsalicylic acid, isopropylantipyrine).

- Appropriate solvent (e.g., methanol, purified water).

- Volumetric flasks and pipettes.

- Certified quartz cuvettes [1].

Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Prepare a series of standard solutions of the analyte at known concentrations (e.g., 8, 20, 40, 80, 160, 400 mg/L for acetylsalicylic acid) [46].

- Absorbance Scan: Measure the absorption spectrum of the most concentrated standard to identify the wavelength of greatest absorption (λ_max).

- Create Calibration Curve: At the λ_max, measure the absorbance of each standard solution in the series. Plot a graph of absorbance versus concentration and determine the slope (S) of the calibration curve.

- Measure Blank Noise: Repeat the measurement of a blank solution (pure solvent) at least 10 times at the λ_max. Calculate the standard deviation (σ) of these blank absorbance values.

- Calculate Quantitation Limit: The quantitation limit (QL) is calculated as follows [46]:

- QL = 10 × σ / S

- This gives the concentration that corresponds to an absorbance signal ten times the noise level of the blank.

Troubleshooting Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for diagnosing the root cause of poor spectrometer sensitivity, starting with the most common and easily addressable issues.

FAQs: Spectrometer Cleaning and Compliance

Q1: How does a dirty spectrometer window affect my data and compliance? Dirty windows on a spectrometer lead to instrument analysis drift and poor analysis readings, necessitating more frequent recalibration [11]. From a compliance perspective, this drift violates the core GLP and GMP principles of data integrity and reliability. Inconsistent results due to poor maintenance can make your data inadmissible for regulatory submissions (GLP) or call into question the quality of a manufactured batch (GMP) [47] [48].

Q2: What is the documented evidence that cleaning is needed? The need for cleaning is evidenced by specific performance issues in your data. Monitor for consistent analytical drift or a sudden increase in the need to recalibrate the instrument [11]. In a GMP environment, this would be tracked against established instrument performance qualifications. Visually, a dirty white calibration disk that is no longer shiny and has fingerprints or particles is clear, objective evidence that must be addressed [14].

Q3: What are the critical cleaning steps for the external optical windows? The cleaning procedure must be documented in a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP). Key steps include:

- White Cal Disk: Use a clean, lint-free, soft cloth. Wipe gently in circular motions, avoiding scratches. For excessive dirt, denatured alcohol may be used [14].

- Aperture/Sample Area: Use canned air (not from a compressor, to avoid oil/moisture contamination). Attach the tube extension, insert it horizontally into the aperture, and use short bursts of air 2-3 times [14].

- General Cuvette Handling: Always handle cuvettes on the frosted or ribbed sides. Wipe the clear optical surfaces with a clean, lint-free cloth before each measurement to prevent fingerprints and smudges [1].

Q4: How do I document cleaning for a GLP/GMP audit? Cleaning and maintenance must be fully documented to ensure the process is reproducible, controlled, and validated [47]. Your documentation should include:

- An SOP for the cleaning procedure.

- A logbook recording each cleaning event, including the date, technician name, and the reason for cleaning (e.g., routine schedule, performance drift).

- Records linking instrument performance checks before and after cleaning to demonstrate effectiveness.

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Sensitivity Due to Dirty Optics

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions & Compliance Actions |

|---|---|---|

| General Analysis Drift & Poor Results | Dirty optical windows (in front of fiber optic or in direct light pipe) [11]. | Action: Clean the windows per SOP [11].Compliance: Document the performance issue and the corrective action in the instrument log. |

| Inconsistent Readings Between Replicates | Cuvette contamination (fingerprints, residues) or inconsistent orientation [1]. | Action: Clean cuvette with lint-free cloth; always use the same orientation [1].Compliance: Use an SOP for sample preparation and cuvette handling. |

| Failed Blank/Calibration | Contaminated or misaligned optics, or a cuvette holder that is not properly seated [1]. | Action: Clean external optics; reseat the cuvette holder. If problem persists, it may require professional servicing [1].Compliance: Document the failure and all troubleshooting steps. Servicing must be performed by a qualified provider. |

Experimental Protocol: Cleaning Spectrometer External Windows

Objective: To restore and maintain spectrometer sensitivity by removing contamination from external optical surfaces without damaging the components, in compliance with GLP/GMP documentation requirements.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions)

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Lint-free, soft cloth | For physically removing particles and smudges without scratching delicate optical surfaces or leaving fibers behind [14]. |

| Canned Air | Used to blow dust and loose particles from the instrument's aperture. Critical: Do not use compressor air, which can contain oil or moisture and cause further contamination [14]. |

| Denatured Alcohol (optional) | A solvent for removing stubborn, greasy contamination. Use sparingly and only if recommended by the instrument manufacturer [14]. |

| Powder-free gloves | Worn to prevent transferring oils and particulates from hands to the optical surfaces or calibration standards during cleaning [49]. |

Methodology

- Initiation & Documentation: Note the date, time, instrument ID, and reason for cleaning (e.g., "routine maintenance" or "corrective action for observed drift") in the equipment logbook.

- Power Down: Turn off the spectrometer, if applicable, to ensure safety.

- White Calibration Disk Cleaning:

- Visually inspect the disk for fingerprints, dust, or other contamination [14].

- Using a clean, lint-free cloth, gently wipe the surface in a circular motion.

- Apply minimal pressure to avoid scratches.

- If necessary, slightly moisten a corner of the cloth with denatured alcohol and repeat, then dry with a clean portion of the cloth [14].

- Aperture Cleaning:

- Attach the plastic tube extension to the nozzle of the canned air can. Do not shake the can or turn it upside down [14].

- Gently insert the tube about one inch horizontally into the center of the instrument's aperture.

- Deliver 2-3 short bursts (approximately 2 seconds each) of air by pressing the button on the can [14].

- Carefully remove the tube.

- Cuvette Area Inspection: If accessible, visually inspect the sample compartment and cuvette holder for debris. Use canned air to gently remove any loose particles.

- Verification & Completion:

- Power the instrument on and allow it to warm up as per the manufacturer's instructions (typically 15-30 minutes) [1].

- Perform a calibration and/or analyze a known standard.

- Document the completion of the cleaning and the result of the verification test in the logbook. If performance is restored, the action is closed.

Workflow Diagram: Compliance-Driven Cleaning Protocol

Systematic Troubleshooting to Isolate and Resolve Sensitivity Loss

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing Poor Spectrometer Sensitivity

What are the key symptoms of a dirty optical window in a spectrometer?

The primary symptoms of dirty optical windows are a gradual drift in instrument analysis and consistently poor analysis readings [11]. You may find that the spectrometer requires more frequent recalibration to maintain accuracy [11]. These symptoms occur because contamination on the windows attenuates or scatters the light entering the optical system, reducing signal intensity.

How can I conclusively verify that the optical windows are dirty?

Confirm the issue by visually inspecting and cleaning the two critical windows that require regular maintenance [11]:

- Window 1: Located in front of the fiber optic cable.

- Window 2: Located in the direct light pipe [11].

A clean, lint-free cloth is suitable for cleaning these windows. If sensitivity improves after cleaning, a dirty window was the root cause.

What is the step-by-step diagnostic process?

Follow this logical flowchart to diagnose the cause of poor spectrometer sensitivity. The process helps distinguish a simple dirty window from more complex instrument faults.

What is the detailed experimental protocol for cleaning and verification?

Objective: To restore spectrometer sensitivity by properly cleaning the optical windows and verifying system performance.

Materials Needed:

- Lint-free cleaning cloths

- Appropriate solvent (e.g., high-purity isopropyl alcohol)

- Recalibration standard samples

- Flat, homogeneous test sample

Methodology:

- System Shutdown: Power down the spectrometer if safe to do so according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Window Access: Locate and gain safe access to the two optical windows: the window in front of the fiber optic and the window in the direct light pipe [11].

- Cleaning: Gently wipe the optical windows using a lint-free cloth lightly moistened with solvent. Avoid abrasive materials or excessive pressure [1].

- System Restart: Power the instrument on and allow the lamp to warm up for at least 15-30 minutes to stabilize [1].

- Performance Verification:

- Prepare a clean, flat recalibration sample by grinding or machining it to ensure a flat surface [11].

- Perform a recalibration following the software's specific sequence.

- Analyze the first recalibration standard five times in succession using the same burn spot.

- Calculate the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD). The RSD for any recalibration standard should not exceed 5. If it does, delete the results and repeat the process [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Lint-Free Cleaning Cloths | Removes particulate contamination from optical surfaces without leaving residues. |

| High-Purity Solvents | Dissolves and removes organic films or grease from optical windows. |

| Recalibration Standards | Validates instrument performance and analytical accuracy after maintenance. |

| New Grinding Pads | Prevents cross-contamination during sample preparation by removing coatings [11]. |

What if cleaning the windows doesn't solve the problem?

If sensitivity remains poor after cleaning, the issue likely lies elsewhere. This diagnostic flowchart helps rule out other common problems. Consult the following table to understand other potential faults and their unique symptoms.

| Potential Fault | Key Differentiating Symptoms |

|---|---|

| Vacuum Pump Failure [11] | Constant low readings for Carbon (C), Phosphorus (P), Sulfur (S); pump is noisy, hot, smoking, or leaking oil. |

| Lens Misalignment [11] | Consistently low light intensity for all analyses; light does not focus correctly on the sample point. |

| Contaminated Argon or Sample [11] | Unstable or inconsistent results; a white or milky appearance to the burn. |

| Unstable Instrument | Drifting readings even after cleaning; can be caused by insufficient warm-up time (less than 30 minutes) or environmental vibrations [1]. |

In the context of research on poor spectrometer sensitivity, accurately diagnosing the root cause is the first critical step toward resolution. Three of the most common culprits are dirty optical windows, an aging light source, and a degrading detector. While they all manifest as a loss of sensitivity, their specific symptoms, affected spectral regions, and troubleshooting methods differ significantly. This guide provides a clear, actionable framework to differentiate between these issues and restore your instrument to optimal performance.

FAQ: Can these problems occur simultaneously?

Yes. Especially in older instruments or those under intense use, it is possible for multiple issues to be present at once. For instance, a spectrometer with an aging lamp may also have contaminated windows, compounding the loss of signal. The recommended approach is to address the simplest and most common issues first—such as cleaning windows and replacing the lamp—before moving on to more complex detector diagnostics.

Dirty Windows or Lenses

Core Concept and Symptoms