Speckle Pattern Reconstruction: Enabling Next-Generation Compact Spectrometers for Biomedical Research

This article explores the transformative role of speckle pattern reconstruction in developing ultra-compact, high-performance spectrometers.

Speckle Pattern Reconstruction: Enabling Next-Generation Compact Spectrometers for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the transformative role of speckle pattern reconstruction in developing ultra-compact, high-performance spectrometers. We examine the fundamental principles of how disordered media and metasurfaces encode spectral information into unique speckle patterns. The discussion covers advanced reconstruction methodologies, including deep learning models like ResNet-50 and U-Net variants, and their applications in biomedical sensing, drug development, and clinical diagnostics. Critical challenges such as system calibration, environmental stability, and optimization strategies are addressed, alongside rigorous validation using metrics including PSNR and SSIM. This synthesis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging speckle-based spectrometers in laboratory and point-of-care settings.

The Principles of Speckle-Based Spectral Encoding and Hardware Foundations

Principle of Operation

Speckle pattern-based spectrometry represents a paradigm shift from conventional spectroscopic methods. Unlike traditional spectrometers that rely on bulky dispersive elements like prisms and gratings to separate light spatially, speckle-based devices utilize the phenomenon of light interference in disordered media [1] [2].

When coherent light passes through a scattering medium, it generates a random, granular interference pattern known as a speckle pattern. Crucially, each specific wavelength of light produces a distinct and highly reproducible speckle fingerprint [1]. This occurs because the exact path each light wave takes through the disordered nanostructures is wavelength-dependent, creating unique interference profiles at the detector. The relationship between incident light and the resulting pattern can be expressed as:

I = Φ · S

where S represents the original spectral signal, Φ represents the measurement matrix transformation performed by the scattering medium, and I represents the observed light intensity (speckle pattern) [3].

Advanced computational algorithms, including deep learning models like Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (CNN-LSTM) networks, then solve the inverse problem to reconstruct the original spectrum from the captured speckle image with high precision [4].

Performance Specifications and Comparative Analysis

The following table summarizes key performance metrics achieved by recent advanced speckle spectrometer implementations:

Table 1: Performance comparison of speckle-based spectrometer technologies

| Technology / Platform | Spectral Range | Spectral Resolution | Form Factor | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Double-Layer Disordered Metasurface [1] [2] | 440–1300 nm (Visible to IR) | ~1 nm | < 1 cm (fingernail-sized) | Direct integration with commercial image sensors |

| CNN-LSTM Denoising on Sapphire [4] | Not Specified | 0.5 nm | Compact and Stable | Advanced denoising algorithm reducing environmental noise |

| Localized Speckle Pattern (Integrating Sphere) [3] | 1520–1567 nm (IR) | 2 pm (0.002 nm) | Not Specified | Uses localized speckles for 35x faster measurement |

Experimental Protocol: Metasurface Integration

This protocol details the methodology for constructing a compact spectrometer using a double-layer disordered metasurface, based on the approach pioneered by KAIST [1] [2].

Materials and Equipment

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Double-Layer Disordered Metasurface | Engineered optical component with nanostructures that scatter light to create wavelength-specific speckles. [1] [2] |

| Image Sensor | Standard CMOS or CCD sensor (e.g., from a smartphone camera) to capture speckle patterns. [1] |

| Tunable Laser Source | For system calibration, providing known wavelengths to establish the reference speckle library. [3] |

| Polarization-Maintaining Fiber (PMF) | Delivers light to the scattering medium while preserving polarization state for consistent speckle generation. [3] |

| Computational Framework | Software with reconstruction algorithms (e.g., CNN-LSTM) to convert speckle patterns into spectra. [4] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- System Assembly: Mount the double-layer disordered metasurface directly onto the active area of the image sensor. The two metasurface layers should be separated by a precisely controlled propagation space to allow for complex light scattering [2].

- Calibration and Library Generation: Illuminate the metasurface-sensor system with light from a tunable laser source across the entire target wavelength range (e.g., 440-1300 nm) in small, discrete steps (e.g., 0.5-1 nm).

- Sample Measurement: Direct the light from the unknown sample onto the metasurface. Capture a single image of the resulting speckle pattern (I).

- Spectral Reconstruction: Input the captured speckle pattern into the reconstruction software. The algorithm (e.g.,

reconstruct_spectrum(I, Φ)) compares the sample pattern against the reference library to compute the most probable original spectrum (S). - Validation: Validate the system's accuracy using standard samples with known spectral features.

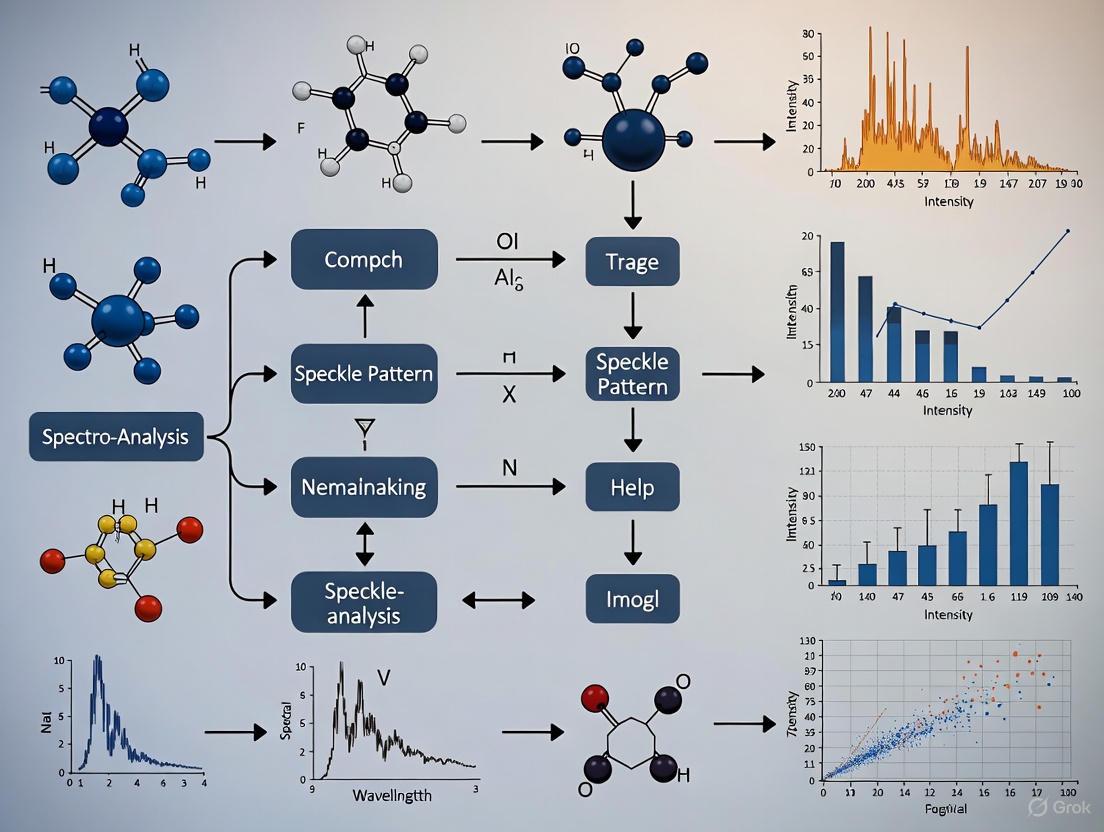

Figure 1: Speckle Spectrometer Workflow

System Architecture and Information Flow

The core of the technology lies in the metasurface, which replaces all bulk optics. The diagram below illustrates the system's architecture and the transformation of light into data.

Figure 2: System Architecture Diagram

Critical Technical Considerations

Scattering Media Selection

The choice of scattering medium directly impacts performance. Research compares multimode optical fibers (MMF) and integrating spheres, showing that localized speckles from an integrating sphere can increase the spectral measurement rate by 35 times compared to full-pixel speckles from an MMF, without sacrificing reconstruction accuracy [3].

Enhancing Signal-to-Noise Ratio

Environmental noise can reduce speckle autocorrelation, leading to reconstruction errors. Implementing a CNN-LSTM denoising algorithm effectively suppresses this noise, ensuring higher reconstruction accuracy and prolonging system stability [4]. This is critical for applications in dynamic environments.

Scattering media, which randomize the propagation of light, have transitioned from being a fundamental challenge in optics to a valuable resource for modern spectroscopic and imaging applications. The core principle underpinning this technology is that a disordered medium can encode the spectral information of incident light into a unique, high-dimensional spatial speckle pattern. This phenomenon enables the development of highly compact and computationally powerful spectrometers and sensors by replacing traditional bulk optical components like diffraction gratings with miniaturized scattering elements. These systems find particular relevance in applications demanding portability and robustness, such as point-of-care medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and industrial process control. This document provides detailed application notes and experimental protocols for implementing spectral encoding systems, with a specific focus on their role in compact spectrometer design within a broader research context of speckle pattern reconstruction.

Theoretical Foundations of Scattering-Based Spectral Encoding

The operation of spectrometers based on scattering media relies on a well-understood physical principle: when monochromatic light is transmitted through or reflected from a disordered medium, it produces a random interference pattern known as a speckle pattern. Crucially, the pattern is highly sensitive to the wavelength of the incident light. A slight change in wavelength results in a completely different, yet deterministic, speckle output.

The relationship between the input field and the output speckle pattern for a fixed scattering medium can be described by a transmission matrix, T. For a vectorial (polarized) optical field, this relationship is expressed as:

$$ \begin{pmatrix} E{out, x}(u,v) \ E{out, y}(u,v)

\end{pmatrix}

\sum{m,n,u,v} \begin{pmatrix} T{11}(m,n,u,v) & T{12}(m,n,u,v) \ T{21}(m,n,u,v) & T{22}(m,n,u,v) \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} E{in, x}(m,n) \ E_{in, y}(m,n) \end{pmatrix} $$

where ((m,n)) and ((u,v)) are the spatial coordinates of the input and output light fields, respectively, and (E{in,x}, E{in,y}) and (E{out,x}, E{out,y}) represent the complex amplitudes of the two orthogonal polarization components of the incident and outgoing vectors [5]. The transmission matrix T thus provides a complete linear description of the medium's scattering properties. In a spectral encoding device, the scattering medium acts as a mixer, mapping the input spectrum to a spatial intensity distribution ((I(x,y) = |E_{out}(x,y)|^2)) that is recorded by a standard image sensor. The reconstruction of the original spectrum is then achieved by employing a pre-calibrated reconstruction algorithm that maps the recorded speckle pattern to a known wavelength or a full spectral profile.

Key Scattering Platforms and Experimental Protocols

Multimode and Few-Mode Optical Fibers

Multimode fibers (MMFs) are a widely used platform for spectral encoding due to their flexibility, low cost, and strong mode-mixing characteristics. MMFs support numerous transverse guided modes (often hundreds or more), which interfere to form a speckle pattern at the output [6]. The large number of modes provides a high-dimensional encoding space, enabling precise spectral discrimination.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Multimode Fiber Systems

| Component | Specifications / Example Types | Function in Experimental Setup |

|---|---|---|

| Multimode Fiber (MMF) | Core/Cladding: 50/125 µm or 62.5/125 µm; Numerical Aperture (NA): 0.2-0.3 [6] | Acts as the primary dispersive and mode-mixing element for spectral encoding. |

| Few-Mode Fiber (FMF) | SMF28-J9 (2nd-mode cutoff 1260 nm), 1550-BHP (2nd-mode cutoff 1400 nm) [7] | Provides a balance between number of modes and manageable complexity; reduces speckle contrast. |

| Broadband Light Source | Superluminescent Diode (SLD), e.g., 840 nm center wavelength, 50 nm bandwidth [7] | Provides the incoherent or partially coherent illumination whose spectrum is to be characterized. |

| Polarization Controller | Inline fiber polarization controller with three adjustable rings [7] | Mitigates polarization-dependent spectral modulation artifacts caused by differential mode delay. |

| Imaging Spectrometer | Custom-built spectrometer with high-speed line camera (e.g., 80 kHz) [7] | Captures the spectrally encoded line for analysis in flow cytometry or imaging applications. |

Experimental Protocol 3.1: Spectrally Encoded Flow Cytometry (SEFC) with Few-Mode Fiber Collection

This protocol details the setup for a fiber-based SEFC system, which demonstrates the practical application of spectral encoding for high-speed cell analysis [7].

Optical Setup Assembly:

- Begin with a polarized broadband light source (e.g., an 840 nm SLD). Collimate the beam and expand it to a 2.5 mm diameter.

- Pass the expanded beam through a transmission diffraction grating (e.g., 600 l/mm) to disperse the spectrum.

- Use a unit-magnification telescope and a high-NA objective lens (e.g., 60×, 1.2 NA) to focus the spectrally encoded line onto the sample plane.

- For signal collection, employ a separate few-mode fiber (e.g., 1550-BHP). Couple the back-scattered light into this fiber using an appropriate collimating lens. A polarizing beam splitter and a quarter-wave plate in the illumination path are used to improve signal efficiency.

- Direct the collected signal to a custom spectrometer equipped with a high-speed line camera.

Calibration and Artifact Mitigation:

- Image a reflective resolution target to establish a baseline.

- If severe vertical fringe patterns appear in the image (an artifact of differential mode delay in the FMF), carefully adjust an inline polarization controller wrapped with the FMF. Manually tune the rings' tilt angles to minimize the fringe contrast.

System Characterization:

- Lateral Resolution Measurement: Image a USAF 1951 resolution target. Calculate the edge response to determine the spatial resolution along the spectrally encoded axis. Expect a slight reduction in resolution (e.g., 0.71 µm for a 1550-BHP fiber vs. 0.54 µm for a single-mode fiber) [7].

- Signal Acquisition: For flow cytometry, acquire images of flowing cells without scanning, at a high line rate (e.g., 20 kHz). The spectral encoding allows for the translation of spatial information into temporal data.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this SEFC protocol:

Laser Projection Speckle for 3D Morphology

While not a spectrometer, this application powerfully demonstrates the use of engineered speckle for high-precision measurement, showcasing another critical facet of speckle pattern reconstruction. It involves projecting a laser speckle pattern onto a target object and using stereoscopic imaging to reconstruct its 3D form.

Experimental Protocol 3.2: High-Temperature 3D Morphology Reconstruction via Laser Speckle Projection

This protocol is designed for challenging environments, such as measuring thermal components at temperatures up to 1000°C, where traditional contact methods or surface-applied speckles fail [8].

Laser Speckle Projector Assembly:

- Construct a laser projection system using a 400 mW laser and a frosted glass diffuser mounted on a micro-displacement platform. The diffuser generates a high-contrast, non-invasive speckle pattern that is projected onto the target specimen.

- Incorporate an optical filtering system (e.g., short-wavelength active light source with a matched narrowband filter) to suppress intense blackbody thermal radiation from the hot sample.

Image Acquisition and 3D-DIC Processing:

- Use a stable, calibrated dual-camera system to synchronously capture images of the laser-speckled specimen from different angles.

- Perform stereo matching and temporal matching of the speckle images using digital image correlation (DIC) algorithms. This process establishes correspondence between points in the left and right images to compute 3D coordinates [8].

Point Cloud Post-Processing:

- The initial 3D point cloud will contain noise and holes due to thermal airflow disturbances.

- Apply a wavelet-based smoothing algorithm to the point cloud data. This step is crucial for reducing high-frequency noise while preserving the underlying sharp features of the object's morphology, thereby significantly improving reconstruction accuracy [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Speckle-Based 3D Reconstruction Methods

| Method | Key Innovation | Test Environment | Reported Performance / Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Speckle & Wavelet Smoothing [8] | Laser projection speckle avoids high-temperature speckle degradation. Wavelet smoothing of point clouds. | 1000°C furnace | High-precision reconstruction; validated against commercial CMM. |

| Bi-Directional Speckle Projection [9] | Two laser projectors overcome occlusion and limited coverage on curved surfaces. | Room temperature | Relative reconstruction error of 0.1% on a semicylindrical surface. |

Advanced Reconstruction Techniques and Data Processing

Deep Learning for Speckle Restoration

Traditional linear reconstruction methods can be limited by noise and the complexity of the scattering process. Deep learning offers a powerful nonlinear alternative for reconstructing information from speckle patterns.

Experimental Protocol 4.1: Adaptive Vectorial Restoration using Trans-CNN Network

This protocol is designed for reconstructing images from dynamic speckle patterns after passing through anisotropic biological scattering media (e.g., chicken breast tissue) [5].

Dataset Generation:

- Generate Vector Optical Fields: Use a spatial light modulator (SLM) in a 4f optical setup to generate input images (e.g., processed MNIST handwritten digits) encoded on vector optical fields.

- Record Speckle Patterns: Transmit these fields through dynamic biological tissue samples of varying thickness (0.5 mm to 2.0 mm). Use a camera to record the resulting output speckle patterns for both orthogonal polarization components. This creates a paired dataset of input images and output speckles.

Model Training:

- Network Architecture: Employ the Trans-CNN network, a hybrid model combining a U-Net (for capturing local features) and a Transformer encoder (for modeling long-range, global dependencies) [5].

- Input and Output: The input to the network is the speckle image. The network is trained to output the reconstructed original image. For vector fields, the final decoding layer splits features into two channels to reconstruct the phase information for each orthogonal polarization component.

Validation and Testing:

- Evaluate the model on a test set of unseen speckle patterns generated by the biological tissue.

- Assess reconstruction quality using metrics like Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) and Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), demonstrating robustness against the dynamic and anisotropic nature of the scattering medium.

The architecture of the deep learning model used in this protocol is detailed below:

Scattering media, ranging from multimode fibers to engineered disordered surfaces, provide a versatile and powerful foundation for developing next-generation compact spectroscopic and imaging systems. The experimental protocols outlined here—from SEFC with few-mode fibers and high-temperature 3D reconstruction to deep-learning-assisted speckle restoration—provide a concrete roadmap for researchers to implement these technologies. The critical considerations of platform selection, calibration, speckle contrast management, and advanced computational reconstruction must be carefully addressed to harness the full potential of spectral encoding. As research progresses, the integration of novel disordered metasurfaces and more sophisticated AI-driven analysis promises to further miniaturize these devices and expand their applications into areas such as wearable sensors, real-time biomedical diagnostics, and harsh-environment monitoring.

In the field of compact spectrometer applications, the reconstruction of speckle patterns represents a transformative approach to spectral analysis. This methodology replaces the bulky dispersive optics of conventional spectrometers with a miniaturized encoding element and a computational reconstruction algorithm [10]. The core of this approach lies in a mathematical framework where spectral information is encoded into a spatial intensity distribution (a speckle pattern) via a transmission matrix, and subsequently decoded to recover the original input spectrum [11] [12]. This document details the foundational mathematical models, quantitative performance metrics, and standardized experimental protocols that underpin this technology, providing a resource for researchers and scientists engaged in its development and application.

Core Mathematical Model

The operation of a speckle-based reconstructive spectrometer can be formulated as a linear encoding process. An unknown input spectrum, represented by the vector S with dimensions ( N \times 1 ) (where ( N ) is the number of spectral channels), is encoded by a transmission matrix T [11] [12] [10]. The result of this encoding is a measured output signal, typically a speckle pattern, represented by the vector I with dimensions ( M \times 1 ) (where ( M ) is the number of detection channels or pixels imaging the speckle) [11] [10]. This relationship is captured by the linear equation:

[ \mathbf{I}{M \times 1} = \mathbf{T}{M \times N} \cdot \mathbf{S}_{N \times 1} ]

In the context of speckle spectrometers, the transmission matrix T is not a designed or simple matrix but is rather a complex and random mapping that is highly dependent on the physical properties of the scattering medium, be it a multimode optical fiber [12], a disordered photonic crystal [12], or a cascaded diffractive metasurface [11]. Each element ( T_{ij} ) of this matrix defines the coupling strength between the ( j )-th spectral component and the ( i )-th detection channel [10]. The process of spectral recovery involves inverting this equation to solve for the unknown spectrum S given the calibrated matrix T and the measured speckle pattern I [10].

Table 1: Key Variables in the Linear Encoding Model for Speckle Spectrometers.

| Variable | Description | Role in Spectral Reconstruction |

|---|---|---|

| S | Input spectrum vector (( N \times 1 )) | The unknown signal to be recovered; represents light intensity at N discrete wavelengths [10]. |

| I | Measured speckle pattern vector (( M \times 1 )) | The encoded signal; a spatial intensity distribution captured by a camera [11] [10]. |

| T | Transmission Matrix (( M \times N )) | The linear model of the encoding hardware; maps spectral channels to spatial channels [11] [10]. |

| ( N ) | Number of spectral channels | Defines the potential spectral resolution and bandwidth of the reconstructed spectrum [11]. |

| ( M ) | Number of detection channels | The number of pixels used to sample the speckle pattern; often ( M < N ) for compressed sensing [10]. |

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of a speckle-based spectrometer is quantified by several key metrics that are directly influenced by the properties of the transmission matrix and the physical encoding hardware.

The spectral correlation width is a critical parameter that indicates the minimum wavelength shift required to produce a statistically independent speckle pattern, thereby defining the fundamental resolution limit of the system [11] [12]. It is calculated from the correlation function of the speckle intensity [11] [12]: [ C(\Delta \lambda) = \left\langle \frac{ \langle I(\lambda, x) I(\lambda + \Delta \lambda, x) \rangle\lambda }{ \langle I(\lambda, x) \rangle\lambda \langle I(\lambda + \Delta \lambda, x) \rangle\lambda } - 1 \right\ranglex ] where ( I(\lambda, x) ) is the recorded intensity at position ( x ) for wavelength ( \lambda ), and ( \langle \cdots \rangle ) denotes averaging over wavelengths or spatial channels [11]. The Half-Width at Half-Maximum (HWHM) of ( C(\Delta \lambda) ) is often reported as the spectral correlation width [11].

Furthermore, the overall capability of a spectrometer is captured by the number of spectral channels, which is the ratio of its operational bandwidth to its resolution [11]. When this is considered relative to the chip area, it gives the channel density, a key metric for assessing the miniaturization and efficiency of on-chip devices [11].

Table 2: Reported Performance of Select Speckle Spectrometer Implementations.

| Implementation | Footprint | Bandwidth | Resolution | Spectral Channels | Channel Density | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-chip Diffractive Metasurface | 150 μm × 950 μm | 100 nm | 70 pm | 1400 | ~10,021 ch/mm² | [11] |

| Multimode Optical Fiber (20 m) | N/A (Fiber) | N/A | 8 pm | N/A | N/A | [12] |

| 2D Photonic Microring Lattice | 1 mm × 1 mm | 40 nm | 15 pm | 2666 | ~2,666 ch/mm² | [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: System Calibration and Transmission Matrix Measurement

This protocol outlines the procedure for calibrating a speckle-based spectrometer by empirically determining its transmission matrix, T.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Tunable Laser Source: Provides a spectrally pure and wavelength-known input for calibration [12].

- Single-Mode Input Waveguide/Fiber: Ensates a consistent spatial and polarization input profile for reproducible mode excitation in the scattering medium [12].

- Multimode Scattering Element: The core encoding element (e.g., multimode fiber [12], cascaded metasurfaces [11]) that generates the wavelength-dependent speckle pattern.

- High-Resolution Camera (CCD/CMOS): Images and records the output speckle patterns for each calibration wavelength [11] [12].

Methodology:

- Setup: Couple the output of the tunable laser source into the scattering element using the single-mode input waveguide. Image the output facet of the scattering element onto the camera [12].

- Data Acquisition: For each wavelength ( \lambdaj ) across the desired operational bandwidth (e.g., in steps matching the target resolution), record the corresponding speckle pattern ( \mathbf{I}(\lambdaj) ) [12].

- Matrix Construction: The measured speckle pattern for each wavelength ( \lambdaj ) forms the ( j )-th column of the transmission matrix T. For a monochromatic input at ( \lambdaj ), the spectrum S is a delta function, and thus ( \mathbf{I}(\lambdaj) = \mathbf{T}{\cdot, j} ), where ( \mathbf{T}_{\cdot, j} ) is the ( j )-th column of T [10].

- Storage: The fully populated ( M \times N ) matrix T is stored for use in the subsequent reconstruction of unknown spectra.

Protocol 2: Spectral Reconstruction of an Unknown Source

This protocol describes the process for reconstructing the spectrum of an unknown light source after the system has been calibrated.

Methodology:

- Measurement: Replace the tunable laser with the unknown light source, ensuring the input coupling conditions remain identical to those during calibration. Capture a single image of the resulting speckle pattern, which constitutes the measurement vector ( \mathbf{I}_{meas} ) [10].

- Inversion: Recover the unknown spectrum ( \mathbf{S}{rec} ) by solving the linear system ( \mathbf{I}{meas} = \mathbf{T} \cdot \mathbf{S}_{rec} ). Since this is often an ill-posed inverse problem (especially when ( M < N )), computational techniques are required [10].

- Computational Techniques:

- Compressive Sensing (CS): Used if the spectrum is sparse in some domain (e.g., has a few sharp peaks). CS algorithms find the solution that best fits the measurement while enforcing sparsity [10].

- Least Squares Minimization: A robust algorithm can combine a truncated inversion technique with least squares minimization to achieve accurate reconstruction in the presence of experimental noise [12].

- Deep Learning: Neural networks, such as U-Net architectures, can be trained to learn the inverse mapping from speckle patterns I directly to spectra S, often showing superior robustness to noise and perturbations [13] [10] [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from system calibration to spectral reconstruction.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Speckle Spectrometer Development.

| Item | Function / Role | Example Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Tunable Laser Source | Provides precise wavelength control for system calibration. | Key for building the transmission matrix; requires high wavelength accuracy and purity [12]. |

| Multimode Fiber / On-Chip Scatterer | Serves as the compact, dispersive element that encodes spectrum into speckle. | Examples: 20m multimode fiber for high resolution [12]; cascaded metasurfaces for on-chip integration [11]. |

| High-Sensitivity Camera | Records the spatial intensity distribution of the speckle pattern. | A monochrome CCD or CMOS camera is typically used; number of pixels defines detection channels (M) [12]. |

| Silicon Photonics Platform | Foundational substrate for fabricating on-chip spectrometers. | Enables integration of input waveguides, metalenses, and metasurfaces using standard processes [11]. |

| Computational Reconstruction Algorithm | Decodes the speckle pattern to recover the original spectrum. | Includes compressive sensing, least squares minimization, or deep learning models [12] [10]. |

The pursuit of miniaturized, high-performance spectrometers has catalyzed the development of advanced encoding hardware that transforms spectral information into measurable spatial patterns. Within the context of compact spectrometer applications, speckle pattern reconstruction has emerged as a powerful paradigm, leveraging complex optical scattering to encode wavelengths into unique intensity distributions. Two particularly promising technologies for generating these encoding patterns are double-layer disordered metasurfaces and femtosecond laser-induced nanostructures. These approaches enable the creation of wavelength-specific speckle fingerprints within extremely compact form factors, bypassing the traditional trade-offs between spectral resolution, operational bandwidth, and device size that have long constrained conventional spectrometer design. By functioning as specialized spectral-to-spatial encoders, these advanced hardware platforms transform integrated image sensors into powerful analytical instruments, bringing laboratory-grade spectroscopic capability to portable formats suitable for field deployment and point-of-care diagnostics.

Double-Layer Disordered Metasurfaces

Double-layer disordered metasurfaces represent a precisely engineered approach to spectral encoding through controlled multiple scattering. These devices comprise two separate layers of nanostructured metasurfaces separated by a precisely defined propagation distance [15] [16]. Each metasurface layer consists of nanoscale scatterers with randomized geometries and positions, typically fabricated from high-index dielectric materials like silicon nitride (SiNx). When incident light passes through this double-layer system, it undergoes wavelength-dependent complex modulation through the combined effects of scattering from both layers and free-space propagation between them.

The operational principle hinges on creating predictable yet highly complex speckle patterns that serve as unique fingerprints for each wavelength [15]. Unlike random scattering media, these disordered metasurfaces are computationally designed, enabling a priori determination of their spectral response without exhaustive empirical characterization. The double-layer configuration provides critical advantages over single-layer implementations by introducing additional degrees of freedom in the optical path, effectively decoupling the requirements for high spectral resolution and adequate sampling of the resulting speckle patterns [15]. This architecture enables spectral resolutions of approximately 1 nm across the visible spectrum (440-660 nm) within a total form factor of less than 1 centimeter [15] [16].

Femtosecond Laser-Induced Nanostructures

Femtosecond laser-induced nanostructures leverage a fundamentally different approach based on controlled surface modification of transparent materials. When femtosecond laser pulses (typically with durations of 10^-15 seconds) are focused onto or within transparent substrates, they induce nonlinear absorption processes that create permanent nanograting structures with feature sizes significantly smaller than the optical wavelength [17] [18]. These self-organized nanostructures exhibit periodic refractive index variations with periods ranging from 60-300 nm, functioning as form-birefringent elements that impart wavelength-dependent polarization and phase modifications to transmitted light [17].

The formation mechanism involves a complex interplay between the incident laser pulse and the electron plasma it creates, leading to nanoscale material redistribution through processes like Coulomb explosion and hydrodynamic ablation [18]. By controlling laser parameters such as pulse energy, duration, repetition rate, and polarization, along with scanning trajectory and speed, researchers can precisely tune the structural characteristics of the resulting nanogratings, including their period, orientation, and birefringence strength [17] [19]. When integrated into spectroscopic systems, these nanostructures serve as compact, robust scattering elements that generate wavelength-dependent speckle patterns, achieving remarkable spectral resolutions as fine as 0.1 nm in demonstrated implementations [20].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Advanced Encoding Platforms for Compact Spectrometers

| Parameter | Double-Layer Disordered Metasurfaces | Femtosecond Laser-Induced Nanostructures |

|---|---|---|

| Spectral Resolution | ~1 nm [15] [16] | 0.1 nm (visible) to 10 pm (NIR) [20] [21] |

| Operational Bandwidth | 440-660 nm (visible) [15] | Up to 200 nm in NIR [21] |

| Form Factor | <1 cm [15] [16] | Chip-scale (mm) [20] [11] |

| Key Advantage | Predictable speckle patterns [15] | Ultra-high resolution [20] |

| Fabrication Method | Nanolithography (e.g., E-beam) [15] | Direct laser writing [17] [18] |

| Integration Compatibility | Direct mounting on image sensors [15] | Surface or bulk modification of various substrates [17] |

Quantitative Performance Specifications

Table 2: Detailed Technical Specifications of Encoding Hardware Platforms

| Performance Metric | Double-Layer Disordered Metasurfaces | Femtosecond Laser Nanostructures on Quartz | On-Chip Diffractive Metasurfaces |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spectral Channels | 221 channels [15] | Not specified | 1400 channels [11] |

| Bandwidth-Resolution Ratio | ~200 | >1000 (for 0.1 nm resolution/100 nm BW) [20] | ~1428 [11] |

| Footprint Area | ~1 cm² [15] | Chip-scale [20] | 0.1425 mm² (150 × 950 μm) [11] |

| Channel Density | Not specified | Not specified | 10,021 ch/mm² [11] |

| Operating Wavelength | Visible (440-660 nm) [15] | Visible to NIR (1500-1600 nm demonstrated) [20] | Telecom (1500-1600 nm) [11] |

| Calibration Requirement | Minimal (predictable design) [15] | Transmission matrix measurement [20] | System-specific calibration [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Fabrication Protocol for Double-Layer Disordered Metasurfaces

The fabrication of double-layer disordered metasurfaces requires precise nanofabrication techniques to create the designed random scattering structures:

Metasurface Design:

- Define disordered patterns of silicon nitride (SiNx) nanoposts with randomized widths using computational design tools.

- Set phase delay values for nanoposts to range from 0 to 2π at the design wavelength (e.g., 532 nm).

- Determine system parameters including inter-layer separation (T ≈ 1.34 mm) and metasurface-to-sensor distance (L ≈ 8 mm) based on desired spectral resolution and form factor constraints [15].

Nanofabrication Process:

- Deposit SiNx thin film on transparent substrate via plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD).

- Apply electron-beam lithography to pattern disordered nanopost arrays with feature sizes ranging from 60-300 nm.

- Use reactive ion etching (RIE) to transfer patterns into the SiNx layer with vertical sidewalls and minimal roughness.

- Repeat the process for the second metasurface layer on a separate substrate, maintaining design consistency [15].

Alignment and Integration:

- Precisely align the two metasurface layers using optical alignment fixtures with sub-micrometer accuracy.

- Fix the inter-layer separation using precision spacers (T = 1.34 mm).

- Directly mount the stacked metasurface assembly onto a commercial image sensor (pixel size = 2.4 μm) using index-matching optical adhesive [15].

- Verify alignment and wavefront distortion using interferometric characterization.

Validation and Testing:

- Illuminate the system with monochromatic light from a tunable laser source across the operational bandwidth.

- Capture speckle patterns at 1 nm wavelength intervals.

- Calculate spectral correlation function to verify resolution using the formula: δλ ≈ λ² / [2(T(1-cosθₘₘ) + L(1-cosθₘₛ))], where θ represents acceptance angles [15].

- Confirm spectral resolution of ~1 nm through correlation analysis of adjacent wavelength speckle patterns.

Fabrication Protocol for Femtosecond Laser-Induced Nanostructures

The formation of nanogratings inside transparent materials using femtosecond laser irradiation follows a precise protocol:

Substrate Preparation:

- Select appropriate transparent substrate (fused silica, borosilicate glass, or sapphire).

- Clean substrates using standard RCA cleaning procedure to remove organic and ionic contaminants.

- Mount substrate on high-precision 3-axis translation stage with rotational capability for polarization control [17] [18].

Laser System Configuration:

- Utilize femtosecond laser system (e.g., Ti:Sapphire, 800 nm, 100 fs, 1 kHz repetition rate).

- Adjust pulse energy using a half-wave plate and polarizer combination (typical range: 0.1-1 μJ depending on material).

- Control beam polarization state using quarter-wave or half-wave plates for circular or linear polarization.

- Focus laser beam inside transparent material using high-NA objective (NA > 0.5) [17] [18].

Nanograting Formation:

- Translate substrate relative to laser focus at constant velocity (1-100 μm/s) while maintaining pulse energy stability.

- Monitor formation quality in real-time using simultaneous reflectance and transmittance measurements.

- Implement active feedback control using proportional-integral-derivative (PID) algorithm to adjust laser power based on transmittance signals for uniform nanostructures [18].

- For surface nanostructures, employ double-sided processing by flipping the substrate and repeating the procedure on the reverse side [20].

Post-Processing and Characterization:

- Anneal samples at elevated temperatures (300-500°C) to enhance stability and remove residual stress (optional).

- Characterize nanograting morphology using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and atomic force microscopy (AFM).

- Quantify birefringence properties using polarization microscopy and spectroscopic ellipsometry.

- Measure phase shift and retardance to confirm desired optical performance [17] [19].

System Integration and Calibration Protocol

Regardless of the encoding platform, proper integration and calibration are essential for optimal spectrometer performance:

Optical Integration:

- Couple light from input source (fiber, free-space) to the encoding element using appropriate optics.

- For on-chip implementations, use adiabatic tapers to match mode field diameters between components.

- Mount encoding hardware at correct distance from image sensor (L = 8 mm for double-layer metasurfaces) [15].

- Implement stray light suppression using baffles and antireflection coatings.

Calibration Procedure:

- Illuminate system with monochromatic light from tunable laser source across full operational bandwidth.

- For double-layer disordered metasurfaces: Capture speckle patterns at 1 nm intervals, verify predictability of patterns [15].

- For femtosecond laser-induced nanostructures: Measure comprehensive transmission matrix by recording speckle patterns at wavelength intervals matching desired resolution (e.g., 0.1 nm) [20].

- Store calibrated transmission matrix T(λ) for subsequent reconstruction algorithms.

Reconstruction Algorithm Implementation:

- For unknown spectrum measurement, capture single speckle pattern I(x,y).

- Solve linear inverse problem I = T×S using regularization techniques (Tikhonov regularization, compressive sensing).

- Implement neural network approaches (ResNet-50, GRU) for enhanced reconstruction accuracy [20].

- Validate reconstruction accuracy using standard reference sources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Encoding Hardware Fabrication

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metasurface Fabrication | Silicon Nitride (SiNx) thin films | Primary dielectric material for metasurfaces | High refractive index (~2.0), low absorption in visible range [15] |

| Electron-beam lithography system | Patterning of nanoscale metasurface elements | Sub-10 nm resolution capability [15] | |

| Reactive ion etching (RIE) system | Transfer of patterns into dielectric materials | High aspect ratio, anisotropic etching [15] | |

| Femtosecond Laser Processing | Ti:Sapphire femtosecond laser system | Inducing nanograting formation in transparent materials | 100-300 fs pulse width, 1-1000 kHz repetition rate [17] [18] |

| High-NA objective lenses | Focusing laser pulses inside transparent materials | NA > 0.5, working distance suitable for processing [17] | |

| Precision 3D translation stages | Controlling sample position during laser writing | Sub-micrometer accuracy, 100+ mm travel range [18] | |

| Characterization Equipment | Spectroscopic ellipsometer | Measuring birefringence of nanogratings | Spectral range covering operational wavelengths [17] |

| Scanning electron microscope (SEM) | Imaging nanostructure morphology | Resolution < 5 nm, compatible with insulating materials [18] | |

| Off-axis holographic microscope | Measuring phase delay of metasurface elements | Quantitative phase imaging capability [15] | |

| Integration Components | Scientific CMOS/CCD image sensors | Capturing speckle patterns for reconstruction | High pixel count (>1 MP), small pixel size (<5 μm) [15] [20] |

| Precision mechanical mounts | Aligning optical components | 5-axis adjustment, sub-micrometer resolution [15] | |

| Tunable laser sources | System calibration | Narrow linewidth (<0.01 nm), broad tuning range [20] |

Applications in Drug Development and Biomedical Research

The integration of advanced encoding hardware into compact spectrometers opens numerous applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical fields:

Point-of-Care Diagnostic Platforms: Miniature spectrometers enable portable chemical analysis systems for therapeutic drug monitoring, allowing healthcare providers to measure drug concentrations in patient blood or urine samples rapidly at the bedside. The 1 nm resolution capability of double-layer disordered metasurfaces permits discrimination of closely related molecular species, while the compact form factor enables integration into handheld diagnostic devices [15] [16].

High-Throughput Pharmaceutical Screening: Speckle-based spectrometers incorporated into microplate readers facilitate rapid characterization of compound libraries during drug discovery. The single-shot measurement capability of these systems significantly accelerates spectral acquisition compared to traditional scanning spectrometers, enabling real-time monitoring of chemical reactions and binding events in high-throughput screening environments [20].

Biomolecular Interaction Analysis: The ultra-high resolution (up to 10 pm) achievable with femtosecond laser-induced nanostructures enables detailed study of molecular interactions through subtle spectral shifts in absorption or fluorescence signatures. This precision allows researchers to monitor conformational changes in proteins, nucleic acid hybridization, and receptor-ligand binding kinetics without labeling [20] [21].

Quality Control in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing: Compact spectrometers integrated into manufacturing systems enable real-time monitoring of drug synthesis and formulation processes. The robustness and minimal calibration requirements of disordered metasurface-based systems make them suitable for industrial environments, providing continuous verification of chemical composition and detection of contaminants during production [15] [16].

These applications demonstrate how advanced encoding hardware transforms spectroscopic capability from a benchtop technique confined to specialized laboratories to a versatile tool deployable throughout the drug development pipeline, from discovery research to manufacturing and clinical monitoring.

Future Perspectives and Development Challenges

The continued advancement of speckle-based spectrometer technologies faces several interdisciplinary challenges requiring collaboration between materials science, photonics, and computational fields:

Fabrication Scalability: Current nanofabrication methods for disordered metasurfaces, particularly electron-beam lithography, face limitations in throughput and cost for mass production. Future development of nanoimprint lithography approaches could enable high-volume manufacturing while maintaining the precise feature control required for predictable speckle generation [15].

Spectral Range Expansion: Most current implementations focus on visible or near-infrared regions. Extending operation to ultraviolet and mid-infrared ranges would significantly broaden application potential in pharmaceutical analysis, but requires development of novel material systems with suitable dispersion properties and transparency in these regions [17] [11].

Computational Efficiency: As spectral resolution and channel counts increase, the computational burden of reconstruction algorithms grows substantially. Development of dedicated hardware accelerators and optimized reconstruction algorithms will be essential for real-time operation in resource-constrained portable devices [20] [21].

Environmental Stability: Maintaining calibration under varying temperature and mechanical conditions remains challenging for field-deployable systems. Research into temperature-compensated designs and active recalibration methods using reference light sources will enhance operational robustness in real-world environments [18].

Multimodal Sensing: Future systems may integrate spectroscopic sensing with other measurement modalities such as polarization analysis or spatial imaging within common hardware platforms. Such hyperspectral imaging capabilities would provide comprehensive material characterization for complex pharmaceutical formulations and biological samples [16] [11].

Addressing these challenges will further establish speckle-based spectrometers as powerful analytical tools that combine the performance of laboratory instruments with the portability and accessibility required for widespread deployment in pharmaceutical research, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring applications.

The advancement of compact spectrometers is intrinsically linked to the strategic engineering of three core performance metrics: spectral resolution, operational bandwidth, and device form factor. These parameters often exist in a trade-off relationship, where improving one can compromise another. For researchers and drug development professionals, navigating this balance is crucial for selecting or developing the appropriate spectroscopic tool for applications ranging from real-time reaction monitoring to portable diagnostic sensing.

This application note delineates these key metrics, provides a quantitative comparison of state-of-the-art technologies, and details experimental protocols for implementing speckle-based spectroscopic systems, which have emerged as a leading approach for achieving high performance in a miniaturized footprint.

Performance Metrics of Miniaturized Spectrometers

The table below summarizes the performance of various miniaturized spectrometer technologies, highlighting the advancements in speckle-based and other computational approaches.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Miniaturized Spectrometer Technologies

| Technology / Architecture | Spectral Resolution | Bandwidth | Bandwidth-Resolution Ratio | Footprint | Form Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| On-Chip Diffractive Speckle Spectrometer [11] | 70 pm | 100 nm | ~1,430 | 150 µm × 950 µm | Layered metasurfaces on SOI chip |

| Disordered Photonic Molecule Spectrometer [22] | 8 pm | >100 nm | >12,500 | 70 µm × 50 µm | CMOS-compatible photonic molecule chip |

| Single-Shot Integrated Speckle Spectrometer [21] | 10 pm | 200 nm | 20,000 | ~2 mm² | Passive silicon photonic network on SOI |

| Compact Speckle Spectrometer (Femtosecond Laser) [20] | 0.1 nm (100 pm) | 100 nm | 1,000 | Not Specified | Double-sided nanostructures on quartz glass |

| Double-Spiral Waveguide Spectrometer [23] | 0.08 nm (80 pm) | 150 nm | 1,875 | Not Specified | Silicon nitride double-spiral waveguide |

| Nonlinear Memristive Spectrometer [24] | 2 nm | 10 nm (630–640 nm) | 5 | Ultra-compact | 2D material (WSe₂) homojunction memristor |

Analysis of Performance Trade-offs

The data reveals distinct strategies for balancing performance metrics. Speckle-based spectrometers consistently achieve high bandwidth-resolution ratios by leveraging complex light-matter interactions to encode extensive spectral information into a spatially-dense speckle pattern [11] [21]. For instance, the single-shot spectrometer uses a cascaded network of unbalanced Mach-Zehnder interferometers and an antenna array to generate a pattern with thousands of independent sampling channels from a compact chip [21].

The disordered photonic molecule spectrometer demonstrates an extreme miniaturization, achieving a resolution of 8 pm in a footprint of just 3500 µm². This is accomplished by using an N-body-like system of coupled microdisks to generate a quasi-chaotic, high-Q transmission spectrum that effectively eliminates the periodicity found in simpler resonator systems [22].

Experimental Protocols for Speckle Spectrometry

Protocol: Transmission Matrix Calibration for a Speckle Spectrometer

This protocol is fundamental to the operation of any reconstructive speckle spectrometer [20] [11].

1. Principle: The system is treated as a linear operator, T, such that I = T ⋅ S, where S is the input spectrum and I is the output speckle intensity pattern. Calibration involves empirically determining the matrix T.

2. Materials:

- Tunable laser source with a wavelength range covering the spectrometer's operational bandwidth.

- Speckle spectrometer chip (e.g., with scattering metasurfaces [11] or a disordered photonic molecule [22]).

- High-resolution imaging system (e.g., an infrared camera with appropriate objectives).

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Couple light from the tunable laser into the spectrometer's input waveguide.

- Step 2: Set the laser to a specific wavelength, λ₁.

- Step 3: Capture the resulting speckle pattern I(λ₁) using the imaging system. Flatten the 2D image into a 1D column vector.

- Step 4: Repeat Steps 2-3 for a dense set of wavelengths (λ₁, λ₂, ..., λ_N) across the entire bandwidth. The wavelength step should be smaller than the target resolution.

- Step 5: Construct the transmission matrix T by assembling the column vectors I(λ₁) ... I(λ_N). Each column of T represents the speckle "fingerprint" for its corresponding wavelength.

4. Data Analysis: The calibrated matrix T is stored and used for subsequent spectral reconstruction of unknown inputs via algorithms like non-negative least squares or trained neural networks.

Protocol: Single-Shot Spectral Reconstruction Using a Passive Photonic Chip

This protocol describes the operational use of a spectrometer like the one detailed in [21].

1. Materials:

- Passive silicon photonic chip with an integrated unbalanced MZI network and antenna array.

- Broadband light source (e.g., supercontinuum laser) or light from the sample under test.

- Imaging system (microscope objective, lens, IR camera).

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Couple the unknown light into the chip's input grating.

- Step 2: Allow the light to propagate through the cascaded MZI network, acquiring wavelength-dependent phase shifts, and diffract into free space via the antenna array.

- Step 3: Capture a single image of the resulting far-field speckle pattern.

- Step 4: Extract the intensity values from the image pixels to form the measurement vector I_meas.

3. Spectral Reconstruction:

- The unknown spectrum Sunknown is reconstructed by solving the equation Imeas = T ⋅ S_unknown, where T is the pre-calibrated transmission matrix.

- Due to noise and an often underdetermined system, solving this typically involves optimization techniques with regularization, such as Tikhonov regularization [25]:

ŝ = argmin ‖T ⋅ s - I_meas‖₂² + α‖s‖₂² where α is a regularization parameter that prevents overfitting to noise.

- Alternatively, deep learning models (e.g., ResNet-50 combined with GRU) can be trained on known speckle-spectrum pairs to directly map Imeas to Sunknown, which can achieve superior resolution beyond the classical Rayleigh limit [20].

Visualization of the Speckle Spectrometry Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and logical relationships in a speckle-based spectral reconstruction system.

Diagram 1: Speckle spectrometry workflow for spectral reconstruction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Speckle Spectrometer Development

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Silicon-on-Insulator (SOI) Wafer | Standard substrate for fabricating CMOS-compatible photonic integrated circuits [11] [21]. | 220 nm top silicon layer on 2 µm buried oxide is a common platform. |

| Femtosecond Laser Writer | Fabricating double-sided surface nanostructures as scattering media on quartz glass [20]. | Enables direct-write, maskless fabrication of complex scattering structures. |

| Si₃N₄ Photonic Platform | Fabrication of ultra-low-loss waveguides for long optical paths in compact spirals or microresonators [23] [26]. | Low material absorption and scattering losses in the near-infrared. |

| Tunable Laser Source | Calibration of the spectrometer's transmission matrix [20] [3]. | Narrow linewidth, precise wavelength control over the full operational bandwidth. |

| High-Resolution SWIR Camera | Capturing speckle patterns in the telecommunications wavelength band (e.g., 1500-1600 nm) [21]. | High pixel count (e.g., InGaAs sensor) to maximize independent sampling channels. |

| Neural Network Software Stack | High-accuracy spectral reconstruction from speckle patterns, potentially surpassing classical resolution limits [20] [24]. | Frameworks like TensorFlow/PyTorch; architectures like ResNet-50 and GRU are applicable. |

The relentless drive for miniaturization in spectroscopy is being successfully addressed by innovations in speckle pattern reconstruction and other computational methods. As demonstrated, the strategic design of scattering media—from disordered metasurfaces and photonic molecules to cascaded interferometer networks—allows developers to deftly navigate the fundamental trade-offs between resolution, bandwidth, and footprint. The experimental protocols and toolkit outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers in academia and industry to implement, validate, and further advance these compact spectroscopic systems for demanding applications in drug development and beyond.

Reconstruction Algorithms and Biomedical Applications

Speckle patterns, the granular interference structures generated when coherent light scatters through a disordered medium, encode valuable information about the incident light. In compact spectrometer applications, these patterns serve as a unique fingerprint for the spectrum of the light they originate from. The core principle of speckle-based reconstructive spectrometers (RSs) involves capturing the speckle pattern generated by the light to be measured after it passes through a scattering medium, then computationally recovering the incident spectra using specialized reconstruction algorithms [3]. This single-shot working mechanism significantly increases the potential spectral measurement rate compared to traditional scanning spectrometers. The measurement rate of these systems can theoretically reach the kHz scale, primarily limited by the speed of detection and modulation devices [3].

The fundamental mathematical framework governing this process can be expressed as I = Φ · S, where S represents the original spectral signal, Φ denotes the measurement matrix characterizing the scattering medium, and I represents the observed light intensity captured by the detector [3]. The central computational challenge involves inverting this relationship to recover the unknown spectrum S from the measured speckle intensity I, often without direct knowledge of the transmission matrix Φ. This reconstruction process forms the core of modern computational methodologies ranging from traditional transmission matrix inversion to advanced compressive sensing and deep learning techniques.

Computational Reconstruction Methodologies

Transmission Matrix Formalism and Inversion

The transmission matrix (TM) approach provides a comprehensive mathematical framework for describing how optical fields transform when passing through scattering media. For vector optical fields, which convey multidimensional information including intensity, phase, and polarization states, the vector transmission matrix (VTM) formalism becomes essential. The relationship between input and output optical fields is expressed as:

Where Ein and Eout represent the complex amplitudes of the two orthogonal polarization components of the incident and outgoing vector fields, respectively, and T is the VTM capturing the medium's transmission characteristics [5]. In anisotropic biological tissues, the off-diagonal components of the VTM (T₁₂, T₂₁) become non-zero, indicating reciprocal conversion between orthogonal polarization components during propagation [5].

Traditional TM inversion requires precise characterization of the scattering medium through calibration, where the TM is first measured using known input fields and corresponding output speckles. Once characterized, image reconstruction involves numerically inverting the TM to recover the input from measured output speckles. However, this approach faces challenges in dynamic biological media where the TM fluctuates over time due to tissue movement or dehydration.

Explicit Speckle Tracking Algorithms

Explicit speckle tracking methods represent another class of computational approaches, particularly valuable in X-ray phase contrast imaging. These methods track local transverse displacements of speckle patterns in the detection plane after sample insertion.

X-ray Speckle Tracking (XST): This algorithm calculates the 2D cross-correlation between small windows in sample and reference images to determine lateral shifts of speckle modulations [27]. The transverse displacement D⊥(xi, yj) is found by maximizing the zero-normalized cross-correlation between image subsets. The phase image ϕ(x, y) is subsequently obtained through numerical integration of gradients derived from these displacements [27].

X-ray Speckle Vector Tracking (XSVT): This scanning technique enhances lateral resolution to a single pixel and improves angular resolution by acquiring multiple image pairs at different transverse positions of the speckle generator [27]. By organizing collected images into 3D stacks, XSVT achieves superior displacement mapping compared to basic XST.

Compressive Sensing and Ghost Imaging

Compressive sensing (CS) leverages signal sparsity to reconstruct images from significantly fewer measurements than required by the Nyquist-Shannon criterion. In speckle-based spectrometry, CS enables accurate spectral reconstruction from limited speckle data.

Computational Ghost Imaging (CGI) utilizes this principle by correlating random speckle patterns with bucket detector signals to reconstruct images. The object image G(x, y) is reconstructed through the second-order correlation function:

Where In(x,y) represents the intensity distribution of the nth speckle pattern, Sn is the corresponding bucket detector signal, and N is the total number of patterns [28]. Advanced implementations can resolve fine details as small as 2.2 μm using optimized speckle patterns and deep learning enhancement [28].

Deep Learning-Based Reconstruction

Deep learning approaches have revolutionized speckle reconstruction by learning complex mappings between speckle patterns and their corresponding sources without explicit physical models.

Trans-CNN Network: This hybrid architecture combines U-Net convolutional layers for local feature extraction with Transformer self-attention mechanisms for global dependencies [5]. The model processes input speckle images through parallel encoding paths that capture both detailed textural information and long-range pixel relationships, effectively reconstructing high-dimensional characteristics of vector optical fields.

Speckle2Self: A novel self-supervised algorithm for speckle reduction using only single noisy observations [29]. By applying multi-scale perturbation operations that introduce tissue-dependent variations while preserving anatomical structure, the method isolates clean images without requiring paired training data.

U-Tunnel-Net: A U-Net variant specifically designed for speckle noise reduction, featuring strategic pooling operation placement between convolution blocks and novel Tunnel Blocks incorporating the xUnit activation function [30]. This architecture preserves significant features after pooling operations before transfer through skip connections, enhancing denoising performance for ultrasound imaging.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Reconstruction Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmission Matrix Inversion | Direct inversion of measured transmission matrix | Physically interpretable; High accuracy with known TM | Requires precise calibration; Sensitive to medium changes |

| Explicit Speckle Tracking (XST/XSVT) | Cross-correlation of local speckle displacements | Simple implementation; Quantitative phase retrieval | Limited spatial resolution; Computationally intensive |

| Compressive Sensing & Ghost Imaging | Sparse signal recovery from undersampled measurements | Reduced measurements required; Lensless imaging possible | Reconstruction artifacts possible; Dependent on sparsity |

| Deep Learning (Trans-CNN, U-Tunnel-Net) | Learned mappings from speckle to source | Handles complex noise; Robust to variations | Large training data needed; Black-box nature |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Transmission Matrix Calibration for Spectral Reconstruction

Purpose: To characterize the transmission matrix of a scattering medium for compact spectrometer applications.

Materials:

- Tunable laser source (1520-1567 nm range)

- Polarization-maintaining fiber

- Scattering medium (integrating sphere or multimode fiber)

- InGaAs camera or CMOS detector

- Computational processing unit

Procedure:

- Setup Configuration: Connect the tunable laser to the polarization-maintaining fiber, which is fused with the selected scattering medium (integrating sphere recommended for higher measurement rates) [3].

- Wavelength Sampling: Step through the wavelength range of interest (e.g., 1520-1567 nm) at discrete intervals, ensuring sufficient sampling for target spectral resolution.

- Speckle Acquisition: At each wavelength, capture the corresponding speckle pattern using the camera. For local speckle analysis, crop regions of interest to 1/50 of full-pixel speckles to increase measurement speed by 35× without significant accuracy loss [3].

- Matrix Construction: Organize speckle patterns into column vectors to construct the measurement matrix Φ, where each column corresponds to a specific wavelength.

- Validation: Verify matrix accuracy by reconstructing known test spectra and calculating mean squared error (target: ~10⁻³ order) [3].

Computational Analysis:

- For spectral reconstruction, solve the linear system I = Φ · S using regularization techniques (Tikhonov regularization recommended for ill-conditioned systems).

- Implement singular value decomposition (SVD) for matrix inversion with truncation to eliminate noise-sensitive components.

Protocol: Deep Learning-Based Speckle Reconstruction

Purpose: To implement a Trans-CNN network for vector field reconstruction from dynamic speckle patterns through biological scattering media.

Materials:

- Vector optical field generation system (4f configuration)

- Biological scattering samples (chicken breast tissue slices, 0.5-2.0 mm thickness)

- Polarization-resolved detection system

- GPU-accelerated computational platform

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition:

- Generate vector optical fields using coherent superposition of orthogonal polarization basis vectors [5].

- Pass generated fields through biological samples of varying thickness.

- Capture output speckle patterns using polarization-resolved detection.

- Acquire approximately 10,000 speckle-image pairs for training [5].

Network Implementation:

- Configure Trans-CNN architecture with parallel U-Net and Transformer paths.

- Set input speckle image size to 256×256 pixels.

- For Transformer path, divide input image into 16×16 patches with projection to 768-dimensional embedding space [5].

- Implement skip connections with multiplicative feature combination.

Training Protocol:

- Initialize with He normal weight initialization.

- Use Adam optimizer with learning rate 1×10⁻⁴.

- Train for 1000 epochs with batch size 16.

- Employ early stopping with patience of 50 epochs.

Validation:

- Evaluate on test set with structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR).

- Assess generalization on unseen tissue samples and thicknesses.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Speckle-Based Spectrometry Research

| Category | Specific Items | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Scattering Media | Integrating spheres, Multimode fibers, Ground glass diffusers | Generate speckle patterns; Integrating spheres provide 35× faster measurement than MMFs [3] |

| Optical Components | Polarization-maintaining fibers, DMDs (Digital Micromirror Devices), Waveplates | Control polarization state; Generate structured illumination; DMDs enable programmable speckle patterns [28] |

| Detection Systems | InGaAs cameras, CMOS detectors, Single-pixel bucket detectors | Capture speckle patterns; Balance frame rate and resolution; Silicon cameras achieve ~200 kHz for visible light [3] |

| Computational Tools | NIRFASTer, NeuroDOT, Custom deep learning frameworks | Forward modeling and image reconstruction; Specialized packages for diffuse optical tomography [31] |

| Sample Preparation | Polystyrene microspheres, Chicken breast tissue slices, USAF resolution targets | Phantom validation; Biological tissue analogs; Resolution testing [32] [5] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Speckle Pattern Reconstruction Workflow. This diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from laser illumination through scattering media to computational reconstruction using various methodologies.

Diagram 2: Trans-CNN Network Architecture. This hybrid deep learning model combines U-Net convolutional layers for local feature extraction with Transformer self-attention mechanisms for capturing global dependencies in speckle patterns.

The application of deep learning architectures for pattern recognition represents a cornerstone of modern computational analysis, enabling breakthroughs across multiple scientific disciplines. In the specific context of speckle pattern reconstruction for compact spectrometer applications, the challenges of noise resilience, feature extraction, and sequence modeling require specialized architectural solutions. ResNet-50, Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs), and U-Net variants have emerged as particularly powerful tools for addressing these challenges, each contributing unique capabilities to the pattern recognition pipeline. ResNet-50 provides the deep feature extraction necessary for discerning subtle patterns in spectral data; GRU networks model temporal and sequential dependencies in wavelength-dependent phenomena; while advanced U-Net variants enable precise reconstruction of speckle patterns with pixel-level accuracy.

The integration of these architectures creates a powerful framework for spectrometer miniaturization, where traditional optical components are replaced or augmented by computational methods. Speckle patterns, which arise from the interference of scattered light, contain rich information about the incident light's properties but require sophisticated analysis to decode. The architectures discussed herein provide the mathematical foundation for transforming these complex interference patterns into actionable spectral data, enabling the development of compact, cost-effective spectroscopic tools with applications spanning pharmaceutical development, chemical analysis, and biomedical diagnostics.

Architectural Foundations

ResNet-50: Deep Feature Extraction

ResNet-50 belongs to the family of residual networks that addressed the vanishing gradient problem in deep networks through skip connections, enabling the training of substantially deeper architectures. The ResNet-50 architecture consists of 50 layers, organized into four sequential stages with increasing filter counts (64, 128, 256, 512). The fundamental innovation is the residual block, which implements the mapping: H(x) = F(x) + x, where x is the input to the block, F(x) represents the learned transformations, and H(x) is the final output. This formulation allows gradients to flow directly backward through the identity connections, mitigating gradient degradation in deep networks [33].

For speckle pattern analysis, ResNet-50 serves as a powerful feature extractor that can identify hierarchical patterns in complex interference structures. The initial layers capture basic edges and textures, while deeper layers assemble these primitives into increasingly abstract representations relevant to spectral decomposition. The architecture's depth and complexity enable it to discern subtle variations in speckle patterns that correspond to minute differences in incident light properties, making it particularly valuable for high-resolution spectroscopic applications [34].

Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU): Sequential Modeling

Gated Recurrent Units represent a sophisticated evolution in recurrent neural network architecture, designed to capture temporal dependencies in sequential data while addressing the vanishing gradient problem through gating mechanisms. The GRU simplifies the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) unit by combining the input and forget gates into a single update gate, resulting in fewer parameters while maintaining comparable performance on many sequence modeling tasks [35].

The mathematical formulation of a GRU cell includes two primary gates:

- Update gate (z_t): Controls the balance between previous hidden state information and new candidate activation

- Reset gate (r_t): Determines how much of the previous hidden state contributes to the candidate activation

These gates enable the GRU to selectively retain important historical information while discarding irrelevant content, making it particularly effective for modeling wavelength-dependent sequential patterns in spectroscopic data. In compact spectrometer applications, GRU networks can model the temporal evolution of speckle patterns as they respond to changing light properties, capturing complex dependencies that would be challenging for traditional feedforward networks [35].

U-Net Variants: Precision Reconstruction

The U-Net architecture, originally developed for biomedical image segmentation, has become a cornerstone for precise pixel-level reconstruction tasks across multiple domains. The base architecture features a symmetric encoder-decoder structure with skip connections that preserve spatial information across layers. The encoder progressively reduces spatial resolution while increasing feature depth, capturing contextual information efficiently. The decoder then reconstructs spatial resolution while leveraging skip connections to recover fine-grained details lost during downsampling [36] [37].

Recent variants have significantly enhanced the original architecture:

- U-Net++: Incorporates nested skip pathways that reduce the semantic gap between encoder and decoder features

- U-Net 3+: Employs full-scale skip connections and deep supervision to improve feature fusion

- Attention U-Net: Integrates attention gates that selectively emphasize relevant spatial features

- Transformer-U-Net: Replaces convolutional blocks with transformer modules for improved long-range dependency modeling [38] [37]

For speckle pattern reconstruction, these U-Net variants enable precise mapping from raw interference patterns to reconstructed spectra, with particular strength in preserving high-frequency components and managing the complex, non-linear relationships inherent in the phenomenon.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Deep Learning Architectures on Pattern Recognition Tasks

| Architecture | Top-1 Error (%) | Parameters (Millions) | Inference Speed (ms) | Key Strengths | Speckle Pattern Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNet-50 | 7.3 | 25.6 | 89 | Hierarchical feature extraction, stable training | Feature extraction from complex speckle textures |

| GRU | N/A | 3.2 | 45 | Temporal modeling, parameter efficiency | Sequential spectral data reconstruction |

| U-Net (Base) | N/A | 31.2 | 76 | Pixel-level precision, skip connections | Speckle-to-spectrum translation |

| U-Net++ | N/A | 36.4 | 92 | Reduced semantic gap, improved fusion | Detailed speckle pattern reconstruction |

| Attention U-Net | N/A | 34.1 | 84 | Spatial feature selection | Noise-resilient speckle analysis |

| Transformer-U-Net | N/A | 48.7 | 121 | Long-range dependency modeling | Global speckle pattern correlations |

Table 2: U-Net Variant Performance on Medical Imaging Tasks (Relevant to Speckle Pattern Analysis)

| Architecture | Dice Coefficient | mIoU | Parameter Efficiency | Inference Speed | Relevance to Speckle Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional U-Net | 0.823 | 74.9% | Medium | 89 ms | Baseline for speckle reconstruction |

| Weak-Mamba-UNet | 0.887 | 87.21% | High | 62 ms | Long-range speckle correlations |

| MWG-UNet++ | 0.8965 | 85.4% | Medium | 76 ms | Multi-scale speckle feature fusion |

| AFTer-UNet | 0.879 | 83.6% | Medium | 68 ms | Computational efficiency for embedded spectrometers |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ResNet-50 for Speckle Pattern Feature Extraction

Purpose: To extract discriminative features from raw speckle patterns for preliminary spectral classification.

Materials:

- Speckle pattern dataset (minimum 10,000 samples)

- NVIDIA V100 or equivalent GPU

- PyTorch or TensorFlow deep learning framework

- Data augmentation pipeline

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Resize all speckle patterns to 224×224 pixels to match ResNet-50 input requirements. Apply data augmentation including rotation (±15°), random cropping (85-100% of original area), and brightness variation (±20%).

- Model Configuration: Initialize ResNet-50 with pre-trained ImageNet weights. Replace the final fully connected layer with a custom classifier head matching the number of spectral classes in your dataset.

- Training Configuration: Set batch size to 32, initial learning rate to 0.001 with cosine decay, and cross-entropy loss. Use the Adam optimizer with default parameters.

- Fine-tuning: Train the network for 100 epochs, monitoring validation accuracy. Apply early stopping if validation performance plateaus for 10 consecutive epochs.

- Feature Extraction: Remove the classification head and use the output of the final convolutional layer (before global average pooling) as a 2048-dimensional feature vector for each speckle pattern.

Validation Metrics: Track top-1 classification accuracy, feature discriminability (using t-SNE visualization), and reconstruction error from downstream processing.

Protocol 2: GRU for Sequential Spectral Reconstruction

Purpose: To model the temporal dependencies in wavelength-swept speckle patterns for accurate spectral reconstruction.

Materials:

- Time-series speckle data (wavelength-dependent sequences)

- High-memory computational resources for sequence processing

- Python with Keras/TensorFlow implementation

Procedure:

- Sequence Preparation: Organize speckle patterns as sequences ordered by wavelength. Standardize each frame to zero mean and unit variance. Sequence length should be optimized for specific spectrometer characteristics (typically 50-200 frames).

- Architecture Configuration: Implement a 3-layer GRU network with 256 units per layer. Include layer normalization between GRU layers and 20% dropout for regularization.

- Teacher Forcing: During training, use teacher forcing with probability 0.5 to improve convergence. Use scheduled sampling to transition to model outputs during later training stages.

- Training Protocol: Train using mean squared error loss with the Adam optimizer (learning rate = 0.0005, β₁ = 0.9, β₂ = 0.999). Use gradient clipping at norm 5.0 to prevent explosion.

- Inference: For spectral reconstruction, process complete sequences using autoregressive generation or single forward pass depending on application requirements.

Validation Metrics: Sequence prediction accuracy, mean squared reconstruction error, and inference latency.

Protocol 3: U-Net for Speckle-to-Spectrum Translation

Purpose: To implement pixel-level reconstruction of spectral data from individual speckle patterns.

Materials:

- Paired speckle patterns and corresponding ground-truth spectra