Spectrometer Vacuum Pump Troubleshooting: A Complete Guide for Research and Pharma Professionals

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and optimizing spectrometer vacuum pump systems.

Spectrometer Vacuum Pump Troubleshooting: A Complete Guide for Research and Pharma Professionals

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding, troubleshooting, and optimizing spectrometer vacuum pump systems. It covers foundational principles, common failure symptoms like inaccurate carbon/phosphorus readings, step-by-step diagnostic procedures, and advanced optimization strategies. The article also explores future vacuum technologies and their implications for high-precision analytical work in biomedical and clinical research, ensuring data integrity and instrument reliability.

Understanding Your Spectrometer's Vacuum Pump: Why It's Critical for Accurate Results

The Role of Vacuum in Optical Emission Spectrometry (OES)

Troubleshooting Guides

Common OES Vacuum System Faults and Solutions

The vacuum system is a critical component of an Optical Emission Spectrometer. The table below summarizes common vacuum-related faults, their symptoms, and solutions [1] [2].

| Problem | Symptoms & Indicators | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Vacuum / Pump Malfunction | Constant low readings for C, P, S; Pump is hot, loud, smoking, or leaking oil; Loss of low wavelength intensity [2]. | Check and replace pump oil; Ensure pump starts automatically; Contact service provider for pump inspection or replacement [1] [2]. |

| Exhaust Not Smooth/Blocked | Restricted argon flow; Possible impact on spark chamber environment [1]. | Replace blocked exhaust pipe; Purge exhaust pipe regularly; Check for foreign objects in spark chamber elbows or argon filter inlets [1]. |

| Rapid Vacuum Drop | Vacuum value decreases quickly; Vacuum curve is not smooth [1]. | Check the tightness of the vacuum chamber cover; Replace the sealing ring or diagonally tighten the screws [1]. |

| Contaminated Optic Chamber | Drifting analysis results; Poor reproducibility; Unstable data for low-wavelength elements [1] [2]. | Clean the vacuum optical path lens; Perform re-standardization after cleaning [1]. |

| Low Light Intensity | General decrease in signal intensity; Can lead to incorrect analysis results [1]. | Clean the excitation table and spark chamber; Check and clean the entrance slit; Inspect fiber optic for potential aging [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Vacuum System Check

This protocol provides a methodology for diagnosing vacuum system issues [3].

1. Visual Inspection:

- Objective: Identify obvious physical defects.

- Procedure:

- Inspect the entire path from the excitation point back to the vacuum pump.

- Ensure all fittings, tubing, and hoses are securely connected. Even small leaks are highly detrimental in vacuum systems [3].

- Check for any signs of blockages or kinks in the lines. The use of clear hose is recommended for easier inspection [3].

- Inspect the pump inlet filters for clogging and clean or replace them as needed [3].

2. Vacuum Level Measurement:

- Objective: Isolate the section of the system causing the problem.

- Procedure:

- If possible, measure the vacuum level at two points: near the excitation point (or optic chamber) and at the vacuum pump itself [3].

- Interpretation of Results:

- Both gauges show similar, low vacuum levels: This indicates the pump is not working correctly or there is excessive leakage throughout the entire system [3].

- Gauge at pump shows high vacuum, but gauge near excitation point shows low vacuum: This indicates a flow restriction or significant leakage between the two measurement points [3].

- Both gauges show similar, adequate vacuum levels: The problem likely lies at the excitation point itself (e.g., a poor seal) or with the fundamental design of the system for the current application [3].

3. Vacuum Pump Performance Verification (Deadhead Test):

- Objective: Confirm the vacuum pump is functioning according to its specifications.

- Procedure:

- Block the vacuum inlet port of the pump (after the vacuum gauge).

- Turn on the pump and check the maximum vacuum level it achieves.

- This reading should closely match the performance data provided by the pump manufacturer. A significant difference indicates the pump requires maintenance or replacement [3].

4. Leak Detection:

- Objective: Locate the source of air ingress.

- Procedure:

- For systems that can maintain a moderate vacuum, use a non-damaging smoke or water mist around potential leak points (fittings, seals, joints) while the vacuum is on. The vacuum will draw the smoke or mist into the leak, making it visible [3].

- For mass spectrometer vacuum systems, a common method is to use a tracer gas like chlorodifluoromethane (found in "dust-off" aerosols) or sulfur hexafluoride (SF6). While monitoring the mass spectrum for the tracer gas's characteristic peak (e.g., m/z 51/67 for chlorodifluoromethane, m/z 127 for SF6), spray short bursts around suspected leak points. A spike in the signal indicates a leak [4].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a vacuum necessary in the optical chamber of an OES? A vacuum is required to purge the optic chamber of atmospheric gases. This allows low-wavelength light (such as ultraviolet) to pass through unimpeded. Low wavelengths cannot effectively pass through a normal atmosphere, and their loss would lead to incorrect values for critical elements like Carbon, Phosphorus, Sulfur, and Nitrogen [2].

Q2: What are the key signs that my OES vacuum pump needs maintenance? Key warning signs include consistently low analytical results for carbon, phosphorus, and sulfur; the pump being hot to the touch, extremely loud, or making gurgling noises; and any visible smoke or oil leaks from the pump. Oil leaks require immediate attention [2].

Q3: My data for low-wavelength elements is unstable. Could the vacuum be the cause? Yes. Instability or poor reproducibility for elements like C, P, and S is a classic symptom of a vacuum problem. Contamination of the optical path lens due to poor vacuum maintenance is a common cause. The solution is to clean the vacuum optical lens and then re-standardize the instrument [1].

Q4: How does a dirty lens affect my OES results, and how is it related to vacuum? Dirty lenses (in front of the fiber optic or in the direct light pipe) cause instrument analysis to drift, leading to poor and unstable results. This necessitates more frequent recalibration. While lens contamination is a separate maintenance issue from vacuum integrity, both can cause similar symptoms of data drift, and the vacuum chamber lens is particularly prone to contamination if the vacuum environment is compromised [2].

Q5: What regular maintenance can I perform to prevent vacuum issues? Regular maintenance is the best prevention [5]. This includes:

- Daily: Checking oil levels (for oil-filled pumps), listening for unusual noise, and checking for excessive vibration or leaks [5].

- Scheduled: Performing regular maintenance and servicing of the pump and its filters as recommended by the manufacturer [5]. This also includes regularly cleaning the excitation table and spark chamber to prevent leakage and discharge that can affect light intensity [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the maintenance and troubleshooting of OES vacuum systems [1] [4] [2].

| Reagent/Material | Function in OES Vacuum Context |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Argon | Provides an inert atmosphere for clean sample excitation in the spark chamber. Contaminated argon leads to white, milky burns and unstable or inconsistent results [2]. |

| Tracer Gas (e.g., Chlorodifluoromethane, SF6) | Used for pinpointing leaks in the vacuum system. The gas is sprayed around fittings while the mass spectrometer (if part of the system) monitors for its characteristic mass peak [4]. |

| Appropriate Pump Oil | Essential for the proper operation and lubrication of oil-sealed rotary vane vacuum pumps. Using the incorrect or degraded oil can lead to pump failure and poor vacuum [1] [5]. |

| Lens Cleaning Solvents & Supplies | Specialized solvents and lint-free wipes are used to clean the optical windows and lenses in the vacuum path. Dirty lenses cause drifting analysis and poor results [1] [2]. |

| Vacuum Sealing Grease (e.g., Apiezon L) | A low vapor pressure lubricant applied in a very light film to O-rings (e.g., Viton) during reassembly to ensure a perfect seal and prevent leaks [4]. |

| Replacement Seals & Gaskets | Critical spare parts for maintaining vacuum integrity. Metal gaskets (copper, gold) should typically be replaced upon resealing, while elastomer seals (Viton) should be inspected and lubricated [4]. |

This technical support center resource is framed within a broader thesis on troubleshooting vacuum pump issues in spectrometers. For researchers and drug development professionals, maintaining an optimal vacuum is not merely a procedural step but a foundational requirement for instrument integrity and data accuracy. This guide provides targeted, actionable troubleshooting protocols for the three primary vacuum pump types—rotary vane, diaphragm, and turbomolecular—found in mass spectrometry systems. The following sections offer detailed FAQs and diagnostic workflows to facilitate rapid identification and resolution of common vacuum failures, minimizing instrumental downtime in critical research operations.

Troubleshooting Guides

Diaphragm Pump Troubleshooting

Diaphragm pumps often serve as the roughing pumps in spectrometer vacuum systems. Issues here can prevent the high-vacuum pumps from starting.

Common Failure Modes and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pump fails to start | Power failure; Voltage drop; Locked connecting rod; Thermal protector activated [6] | Check power supply & switch; Disassemble pump head to check interior; Let pump cool down [6] |

| Abnormal noise | Damaged bearing; Damaged diaphragm; Damaged motor [6] | Replace bearing; Replace diaphragm; Replace or repair motor [6] |

| Performance degradation | Damaged diaphragm or valves; Clogged air filter; Leak in intake pipe; High ambient temperature [6] | Replace diaphragm & valves; Clean or replace air filter; Repair pipe leak; Ensure ambient temp is 7–40°C [6] |

| Excessive oil consumption | Broken diaphragm(s) [7] | Replace all diaphragms and oil [7] |

| Irregular pressure | Air suction in suction line; Incorrect pulsation dampener setting [7] | Inspect & secure all pipes/fittings; Reset dampener pressure [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Testing for a Damaged Diaphragm

- Safety Isolation: Disconnect the pump from all power and the spectrometer system.

- Visual Inspection: Disassemble the pump head according to the manufacturer's instructions to access the diaphragm.

- Condition Assessment: Inspect the diaphragm for lacerations, cracks, semi-circular cuts, or chemical swelling as described in the troubleshooting guide [7].

- Replacement: If damage is found, replace the diaphragm and the pump oil, as fluid from the pumping chamber may have contaminated it [7].

- Leak Check: After reassembly, perform a system leak check by monitoring the rough vacuum pressure to ensure it reaches and holds the expected level.

Rotary Vane Pump Troubleshooting

Rotary vane pumps are another common type of roughing pump. Their performance is critical for achieving the necessary foreline vacuum for turbomolecular pumps.

Common Failure Modes and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor ultimate vacuum | Low/contaminated oil; External air leak; Worn vanes, pump body, or lining; Pump temperature too high [8] | Add/replace oil; Locate & fix leak; Check, trim, or replace parts; Improve cooling [8] |

| Oil leakage | Damaged/improperly assembled oil drain plug or tank gasket; Loose oil sight glass; Loose connecting screws [8] | Tighten, adjust, or replace gaskets/plugs; Tighten sight glass; Check & tighten all screws [8] |

| Abnormal noise | Broken rotary spring; Burrs, dirt, or deformed parts; Worn bearing; Motor issues [8] | Replace spring; Check, clean, or deburr; Repair or replace bearing; Inspect motor [8] |

| Oil return | Malfunctioning check valve; Worn pump cover oil seal; Damaged exhaust valve [8] | Disassemble and inspect check valve; Replace oil seal; Replace exhaust valve [8] |

Experimental Protocol: Checking and Changing Pump Oil

- Operate for Sampling: Run the pump for approximately 30 minutes to warm and thin the oil [8].

- Drain Oil: Stop the pump and drain the used oil via the oil drain hole [8].

- Flush (Optional): If the expelled oil is particularly dirty, open the air inlet and run the pump for 10-20 seconds. Slowly add a small amount of clean pump oil into the suction port during this time to flush remaining residue [8].

- Refill: Add fresh, manufacturer-recommended vacuum pump oil until the level is at the midpoint of the sight glass [8].

- Verify Performance: Start the pump and monitor its achieved ultimate pressure to confirm performance restoration.

Turbomolecular Pump Troubleshooting

Turbomolecular pumps (TMPs) create the high vacuum in the mass analyzer. They cannot operate without a properly functioning roughing pump.

Common Failure Modes and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| TMP fails to start | Foreline vacuum not achieved; Faulty bearing; Electrical communication fault [9] [10] | Check rough pump & for leaks; Contact service; Check power board/sensor [9] [10] |

| TMP shuts down during operation | Power interruption; High system leak; Blocked foreline; Bearing failure [11] [9] | Check power connection; Perform leak check; Inspect foreline for blockages; Service pump [11] [9] |

| Poor high vacuum | Large air/water leak; Contaminated vacuum system; Dirty or damaged pump [12] | Perform leak check; Clean vacuum vessel & components; Service pump [12] |

| High noise/vibration | Imbalance from foreign object damage; Bearing wear [9] | Stop pump immediately; Contact qualified service technician |

Experimental Protocol: Isolating a High-Vacuum Leak

- Initial Check: Ensure the roughing pump is operating correctly and achieving its typical foreline pressure.

- Isolate the TMP: Close the valve between the TMP and the spectrometer chamber.

- Check TMP Ultimate Pressure: Allow the TMP to run. If it reaches its normal high vacuum alone, the leak is in the spectrometer chamber or the connecting piping.

- Perform a Pressure Rise Test: Isolate the spectrometer chamber (with the TMP valve closed) and monitor the pressure. A rapid rise indicates a significant leak or virtual leak from contamination [12].

- Leak Detection: With the system under rough vacuum, use a can of diagnostic gas (e.g., Dust-Off) and gently spray around all seals, fittings, and the chamber door. In the manual tune, watch for a sudden spike in the signal (especially at m/z 18 for water, 28 for nitrogen, 32 for oxygen), which pinpoints the leak location [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Isopropyl Alcohol (≥99%) | High-purity solvent for cleaning metal vacuum components without leaving residue [13]. |

| Lint-Free Wipes | For cleaning components without introducing particulate contamination [13]. |

| Apiezon L Vacuum Grease | Specific grease for lubricating O-rings on vacuum flanges to ensure proper sealing [9]. |

| Compressed Gas Duster | Used as a leak detection probe by spraying around seals while monitoring system pressure [10]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | For filling cold traps to condense volatile contaminants, helping to diagnose and eliminate contamination [12]. |

| Vacuum Pump Oil | High-performance fluid for rotary vane pumps, providing lubrication and creating a sealing barrier [8]. |

| Ultrasonic Cleaner | For thoroughly cleaning small, intricate vacuum components like valves and fittings [13]. |

| Helium Leak Detector | Professional tool for locating very small vacuum leaks that are difficult to find with other methods. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a vacuum critical inside a mass spectrometer? A vacuum is essential for three primary reasons: 1) It prevents ions from colliding with gas molecules, which would scatter them and cause signal loss or inaccurate mass readings [14]; 2) It enables high resolution and sensitivity by allowing predictable ion trajectories through electric and magnetic fields [14]; 3) It protects sensitive internal components from contamination and damage, thereby extending the instrument's lifespan [14].

Q2: What should I do immediately after a power failure to protect my spectrometer's vacuum system? If the pump stops while under vacuum, a significant pressure differential can make restarting difficult [6]. First, do not attempt to restart the pump without first breaking the vacuum. Open the vent valve to return the pump chamber to atmospheric pressure; this will allow for a smooth restart and prevent overcurrent damage to the motor [6]. For systems with a rotary vane roughing pump, be aware of the risk of oil backstreaming into the mass spectrometer manifold; placing the rough pump lower than the MS or using a foreline trap can mitigate this [11].

Q3: My turbomolecular pump (TMP) won't start, and the error points to the foreline. What are the first checks? The TMP requires a sufficient foreline vacuum (typically ~10⁻² to 10⁻³ mbar) to start. First, verify that your roughing pump (rotary vane or diaphragm) is operating and sounds normal. Next, check the foreline pressure reading. If the pressure is too high, inspect the foreline path for leaks or blockages. A common culprit is a failed O-ring on a connection or access door [9] [10].

Q4: How often should I maintain my rough vacuum pump? Maintenance frequency depends on usage, but a general guideline is:

- Rotary Vane Pumps: Check oil level before each use. Change oil every 100 hours of operation or every 6 months to a year, and inspect vanes during oil changes [8].

- Diaphragm Pumps: Perform a visual inspection of diaphragms and valves every 300 hours or at least annually. Replace diaphragms at the first sign of wear or damage [7] [15].

Q5: The vacuum gauge reads a poor ultimate pressure. How can I tell if the problem is a leak or pump contamination? You can perform a simple test using a cold trap. Pump down the system and note the pressure. Then, insert a cold trap filled with liquid nitrogen into the line between the pump and the chamber. If the pressure drops abruptly (e.g., by an order of magnitude or more), it strongly indicates the system is contaminated with condensable vapors. If the pressure remains unchanged, a leak is the more likely cause [12].

Diagnostic Workflow and System Relationships

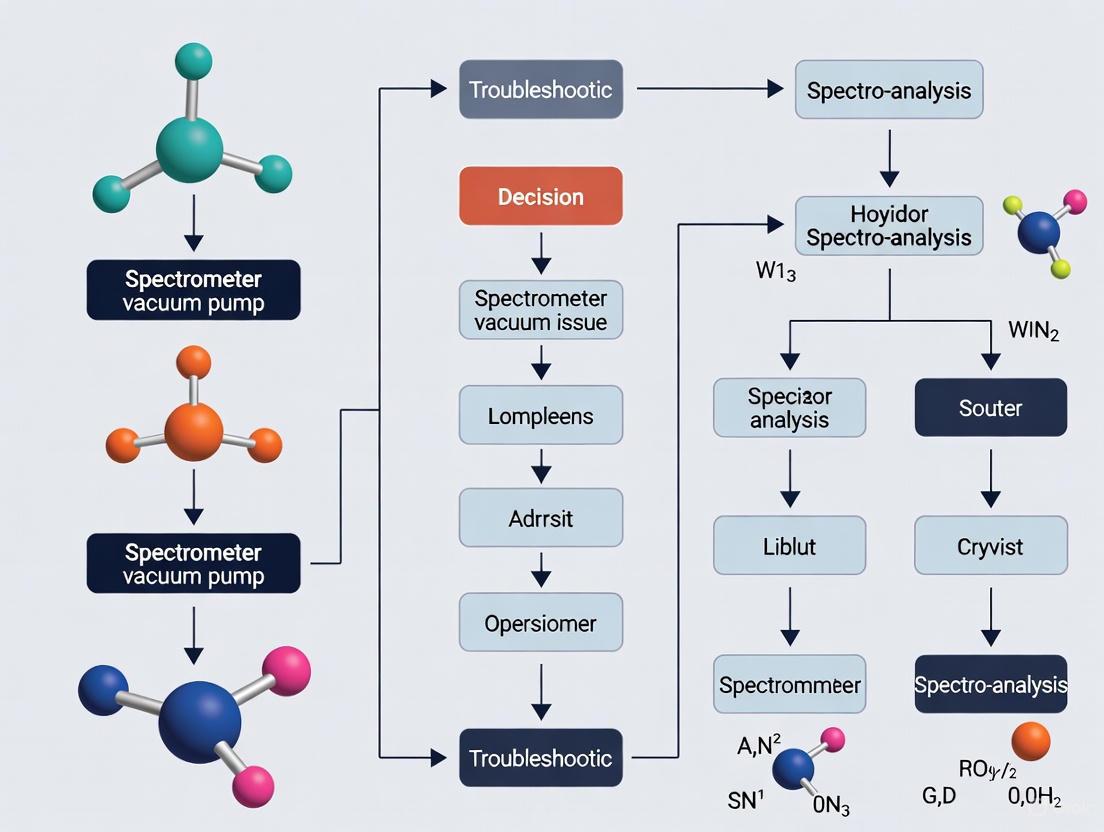

The diagram below visualizes the logical troubleshooting process for a high vacuum failure in a mass spectrometer.

Troubleshooting High Vacuum Failures

Scientific Background and Importance

The Vacuum Ultraviolet (VUV) Region

In optical emission spectrometry, the analysis of light elements—particularly carbon (C), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S)—requires measurement in the short ultraviolet spectral region, specifically the vacuum ultraviolet (VUV) [16] [17]. Atmospheric gases (primarily oxygen and water vapor) strongly absorb light in this wavelength range. To obtain accurate analytical data for these elements, the optical path must be maintained under a high vacuum to prevent signal absorption and ensure light reaches the detector [17]. A vacuum system failure directly compromises the quality of analysis for C, P, and S.

Quantitative Analysis Performance

Laser-induced breakdown spectrometry (LIBS) with multiple pulse excitation has been successfully applied for the multielemental analysis of liquid steel, with a specific focus on C, P, and S using emission wavelengths in the VUV [16]. Calibration curves for these elements have been established, and the estimated limits of detection for direct analysis of liquid steel are below 21 µg/g for each of these light elements [16]. This demonstrates the critical importance of a stable vacuum for achieving low detection limits in process-integrated online analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides

Vacuum Pump Cannot Pump Down

Reported Symptom: The vacuum pump can only reach 20–30 Torr and will not pump down further, affecting analysis of C, P, S [17].

Diagnostic Procedure:

- Isolate the Vacuum Chamber: Close the vacuum valve. If the vacuum level is maintained, the chamber is sealed, and the failure is likely a faulty vacuum probe thermistor [17].

- Test Chamber Integrity: With the vacuum at 20–30 Torr, close the vacuum pump valve. If the vacuum drops rapidly, the vacuum chamber seal is faulty [17].

- Inspect Pump Oil: If the system fails to pump down after many hours, check the vacuum pump oil for water vapor, indicating wet molecular sieve contamination [17].

Resolution:

- Probe/Gauge Failure: Replace the vacuum probe or fine-tune the calibration resistor on the vacuum gauge to approximately 1 Torr [17].

- Chamber Leak: Reseal the vacuum chamber. This involves: a. Venting the chamber slowly to avoid contaminating the optics [17]. b. Sealing the grating cover 'O' ring with minimal vacuum grease [17]. c. Sealing the incident window and the incident slit connection [17]. d. Resealing the photomultiplier tube cable socket holders [17]. e. After resealing, pump down for 30–40 minutes; if the vacuum does not approach 100 Torr after 1 hour, resealing is needed [17].

- Contaminated Molecular Sieve: Heat the collector's molecular sieve to remove water vapor [17].

Vacuum Pumps Do Not Start (Mass Spectrometry)

Reported Symptom: After a power outage or system restart, the vacuum pumps do not start, and the instrument status shows "No Instrument" [18].

Cause: The user did not allow sufficient time for the mass spectrometer's embedded PC to initialize before launching the operating software (e.g., MassLynx). The embedded PC must download its OS and check hardware before accepting commands [18].

Resolution:

- Close the instrument control software [18].

- Press the hardware RESET button on the mass spectrometer using a piece of PEEK tubing [18].

- Alternative for vented instruments: Power cycle the entire MS unit to reboot its electronics [18].

- Wait at least three minutes for the MS to complete its initialization sequence [18].

- Reopen the control software and initiate pumping from the vacuum menu [18].

Error Code: Vacuum Too High to Start Turbo Pump

Reported Symptom: Midway through analysis, argon gas is depleted, and an error code appears: "11011: Vacuum (IF/BK) time out, vacuum too high to start turbo pump" [19]. The error persists after a full system restart.

Cause: The loss of argon pressure may have prevented the automatic closure of a gate valve that separates the atmospheric pressure region from the high-vacuum chamber [19].

Diagnostic and Resolution:

- Inspect the Gate Valve: Remove the cones and lens assembly. Visually inspect if the gate valve is closed. A closed valve should appear as a "silvery black wall" [19].

- Seek Remote Support: If the valve is stuck, contact technical service. An engineer may be able to operate the valve remotely via software (e.g., MassHunter Service interface) if they have remote access to your PC [19].

- Check Consumables: The error can also be related to worn graphite gaskets, incorrect cone dimensions, or damaged O-rings. Inspect and replace these consumables as necessary [19].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my vacuum spectrometer require a specific vacuum level for analyzing Carbon, Phosphorus, and Sulfur? A1: These elements have their most sensitive analytical emission spectral lines in the Vacuum Ultraviolet (VUV) region below 190 nm. Air components (oxygen and water vapor) absorb light in this range. A high vacuum in the optical path is essential to prevent this absorption and allow for accurate measurement [16] [17].

Q2: What are the typical symptoms of a vacuum leak in my spectrometer? A2: Common indicators include [4]:

- Higher than normal ultimate (base) vacuum pressure.

- Elevated levels of background signals for m/z 18 (water), m/z 28 (nitrogen), and m/z 32 (oxygen) in a mass spectrometer.

- A characteristic 4:1 ratio of nitrogen (m/z 28) to oxygen (m/z 32) in the background spectrum.

- Poor analytical sensitivity, especially for high-mass ions and the specific elements C, P, S.

- In an optical emission spectrometer, the vacuum gauge fails to drop below 20-30 Torr [17].

Q3: What methods can I use to find a vacuum leak? A3: A systematic approach is recommended [4]:

- Mass Spectrometer as a Leak Detector: Use the instrument itself to monitor for tracer gases. While watching specific masses, spray a short burst of a tracer gas like chlorodifluoromethane (look for m/z 51, 67) or sulfur hexafluoride, SF₆ (look for m/z 127 or 146) around fittings and seals. A spike indicates a leak [4].

- Solvent Test: For larger leaks, use a high-vapor-pressure solvent like acetone on a cold flange and watch for a response on a vacuum gauge. Caution: Acetone is highly flammable. Do not use near hot components. [4]

- Helium Leak Detector: The most sensitive method. A portable helium leak detector (e.g., Veeco MS-20) can be connected to the vacuum system to precisely locate even very small leaks [4].

Q4: How can I prevent vacuum leaks in my system? A4: Proactive maintenance is key [4]:

- Replace Gaskets: Replace metal gaskets (copper, gold) each time you reopen a flange, or as recommended by the manufacturer.

- Lubricate O-Rings: Apply a light film of low vapor pressure vacuum grease (e.g., Apiezon L) to Viton O-rings before assembly.

- Avoid Damage: Keep flange surfaces clean and be careful not to nick the knife edges on Conflat-type flanges.

- Avoid Overtightening: Be cautious not to overtighten compression fittings (e.g., Swagelok), as this can damage ferrules.

Q5: My vacuum pump is running, but the pressure is not improving. What should I check? A5:

- Chamber Integrity: Follow the guide in section 2.1 to determine if the issue is with the vacuum chamber seals or the pump/gauges themselves [17].

- Virtual vs. Real Leak: A "virtual leak" is caused by outgassing from too much solvent/sample or contaminated surfaces, not an atmospheric leak. Baking the system may be required, whereas leak-checking gases will not help [4].

- Mechanical Pump Condition: Check the foreline (roughing) pump oil. If you see a lot of water vapor or the oil is discolored, the oil may be contaminated and require changing [17].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 1: Key Reagents and Materials for Vacuum System Maintenance and Leak Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chlorodifluoromethane | Tracer gas for leak detection using the mass spectrometer itself. Monitored at m/z 51 and 67 [4]. | Use "environmentally safe dust-off" aerosols. Apply in short bursts. |

| Sulfur Hexafluoride (SF₆) | Tracer gas for leak detection, especially effective in EI/PCI (m/z 127) or NCI (m/z 146) modes [4]. | Effective for locating very small leaks. |

| Argon Gas | Tracer gas for leak detection on instruments tuned to monitor m/z 40 [4]. | A common, safe gas to use. |

| Apiezon L Grease | Low vapor pressure lubricant for vacuum O-rings (e.g., Viton) [4]. | Prevents O-rings from tearing during assembly. Do not use on GC injection port seals. |

| Vacuum Pump Oil | Lubricant and sealant for mechanical roughing pumps. | Check for water contamination (milky appearance) if vacuum performance degrades [17]. |

| Molecular Sieve | Adsorbent used in collectors to trap water vapor and maintain vacuum quality [17]. | Requires periodic heating to drive off absorbed water and regenerate. |

| PTFE Ferrules | Sealing ferruls for compression fittings in heated zones [4]. | More forgiving than pure Vespel ferrules during thermal cycling. |

Experimental Protocol: Vacuum Chamber Resealing

The following workflow details the critical steps for resealing a vacuum chamber, a common procedure to resolve vacuum failures that impact C, P, and S analysis [17].

Figure 1: Vacuum chamber resealing workflow for optical emission spectrometers.

In mass spectrometers and optical emission spectrometers, the vacuum system is a foundational component. Its proper function is essential for achieving accurate analytical results, particularly for elements in the short ultraviolet spectral region like carbon, phosphorus, and sulfur [17]. The system minimizes ion-molecule collisions, prevents ion scattering and neutralization, and protects sensitive components [20]. A failing vacuum system manifests through a range of symptoms, from gradual performance drift to a complete inability to establish vacuum. Recognizing these signs early is key to maintaining instrument integrity and data quality.

FAQs: Common Questions on Vacuum System Failures

Q1: What are the most common early warning signs of vacuum pump problems? The most common early warnings include a gradual decrease in the ultimate vacuum level, an increase in pump-down time to reach the desired pressure, and a noticeable rise in operating noise or vibration [21] [22].

Q2: My vacuum pump is making unusual noises. What could be wrong? New or recently serviced pumps may produce high-pitched screeching from vane break-in, which should subside within 24-48 hours [23]. Persistent or new noises like chattering, clicking, or increased vibration often indicate mechanical wear, such as worn or cupped vanes, bearing failures, or "washboarding" of the cylinder wall [23] [22].

Q3: Why won't my mass spectrometer's vacuum pumps turn on after a power outage? This is a normal safety feature for some instruments. After a power failure, vacuum pumps may not start automatically and must be manually initiated from the Tune page of the instrument control software [24].

Q4: Can a vacuum pump overheat, and what causes it? Yes, overheating is a common symptom. Causes can include a low oil level, using the wrong oil type, motor overload, poor ventilation, electrical problems, or contamination causing internal resistance [21] [22] [25].

Q5: What does it mean if I see oil misting from the pump's exhaust? Oil misting typically indicates the pump is running at a less-than-optimal vacuum level (often below 20”Hg), a saturated or clogged oil separator, or a blocked float chamber or scavenger line [23].

Symptoms and Troubleshooting Guide

Vacuum system failures can be systematic. The following table outlines common symptoms, their possible causes, and immediate troubleshooting actions.

Table 1: Symptom and Troubleshooting Guide for Vacuum Systems

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Troubleshooting Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Vacuum Level [17] [22] [25] | System leaks, contaminated pump, damaged mechanical seal, sticking or worn vanes, faulty vacuum gauge. | Check for leaks, inspect and clean filters, verify mechanical seal, measure vane wear. |

| Increased Noise & Vibration [23] [22] | Worn or cupped vanes, bearing failure, "washboarding" of cylinder, cavitation (in liquid ring pumps). | Inspect vanes and bearings for wear, check power supply voltage, clean pump internals. |

| Extended Pump-Down Time [21] [26] | Contaminated system or pump, restricted pumping line, undersized pump. | Check for contamination, verify line conductance, ensure pump capacity matches the application. |

| Overheating [21] [25] | Motor overload, poor ventilation, low oil level, wrong oil type, blockage in exhaust. | Check oil level and type, ensure ventilation openings are clear, inspect for exhaust blockages. |

| Oil Misting from Exhaust [23] | Pump running at low vacuum, saturated oil separator, clogged float chamber/scavenger line. | Check for inlet leaks, replace oil separator, inspect and clean float chamber and lines. |

| Pump Will Not Start [24] [21] | Blown fuses, incorrect voltage, tripped breaker, internal obstruction. | Check and replace fuses, verify voltage matches motor configuration, check for internal contact. |

| High Background in Mass Spectrometer [4] | Air leak (shows high m/z 18, 28, 32, 40), virtual leak (outgassing). | Perform air/water check, use tracer gas to locate leaks, clean or bake out the source. |

Quantitative Data for Performance Assessment

Monitoring specific operational parameters can help quantify performance degradation. The table below lists key metrics and their normal versus warning ranges.

Table 2: Quantitative Operational Parameters for Vacuum Systems

| Parameter | Normal Operating Range | Warning/Unacceptable Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spec Analyzer Pressure [20] | 10-5 to 10-7 Torr | > 10-5 Torr | Pressure critical for ion transmission. |

| Rough Vacuum Pressure [20] | ~10-3 Torr | > 0.1 Torr | Pressure before high-vacuum pump engagement. |

| Air/Water Background (Tight MS) [4] | m/z 28 < m/z 18 | m/z 28 ≈ m/z 18; m/z 40 & 44 visible | Indicator of a leak in a mass spectrometer. |

| Oil Lubricated Pump Vacuum [23] | 20-29 "Hg | < 20 "Hg | Running below 20 "Hg can cause oil misting. |

| Impeller/Distribution Board Clearance [25] | 0.15-0.20 mm | > 0.20 mm | Affects pump efficiency in liquid ring pumps. |

Experimental Protocols for Diagnosis

Protocol 1: Systematic Leak Checking in a Mass Spectrometer

Objective: To locate and identify real (atmospheric) leaks in a mass spectrometer vacuum system.

- Principle: A tracer gas (e.g., chlorodifluoromethane, SF6, Argon) is sprayed around potential leak points. The gas enters the vacuum system and is detected by the mass analyzer, causing a rapid increase in the tracer's characteristic mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio [4].

- Materials:

- Tracer gas can (e.g., dust removal aerosol containing chlorodifluoromethane).

- Plastic pipette tips or a nozzle for localized application.

- Methodology:

- Verification: Confirm a real leak exists. With the instrument operational, check the background mass spectrum. A nitrogen (m/z 28) to oxygen (m/z 32) ratio of ~4:1, along with significant m/z 40 (Argon), indicates air ingress [4].

- Preparation: Enter the manual tune mode of the mass spectrometer. Set the instrument to monitor the characteristic ion of your chosen tracer gas (e.g., m/z 51 and 67 for chlorodifluoromethane) [4].

- Detection: Spray short, controlled bursts of tracer gas onto external vacuum components, starting with the most recently serviced areas (e.g., column inlet, flanges, seals, valves). Allow a few seconds after each spray for the gas to be detected.

- Identification: A sharp rise in the signal of the tracer ion indicates the location of the leak. For very small leaks, use a plastic pipette tip to apply the gas to a very small area and be patient [4].

- Safety Notes: Use flammable tracers like acetone with extreme caution, especially on hot components [4].

Protocol 2: Diagnosing Insufficient Vacuum in an Optical Emission Spectrometer

Objective: To isolate the cause of a vacuum pump's inability to pump below 20-30 Torr in an optical emission spectrometer [17].

Principle: A structured sequence of tests to determine if the fault lies with the vacuum gauge, the vacuum chamber seals, or the pump and its consumables.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Vacuum System Maintenance

| Item | Function/Application | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Tracer Gases | Used to locate minute leaks in the vacuum system. | Chlorodifluoromethane (m/z 51, 67), SF6 (m/z 127/146), Argon (m/z 40) [4]. |

| High-Vapor Pressure Solvent | Alternative leak-checking fluid; causes a rapid pressure rise when it enters a leak. | Acetone (Use with caution due to flammability) [4]. |

| Vacuum Grease | Low vapor pressure lubricant for elastomer seals to ensure a proper seal and prevent damage. | Apiezon L [4]. Applied sparingly to 'O'-rings during reassembly [17]. |

| Liquid Nitrogen | Creates a cold trap to freeze out vapors, helping to distinguish between a real air leak and system contamination. | Used to fill a cold trap; a pressure drop indicates contaminant vapors [26]. |

| Flushing Oil / Solvent | Cleans thick, contaminated oil or vane debris from the internal workings of oil-lubricated pumps. | Used to free stuck vanes and improve oil flow [23]. |

Workflow:

- Test the Vacuum Gauge:

- Test the Chamber Seal:

- With the vacuum at 20-30 Torr, close the vacuum pump valve. If the chamber pressure rapidly decreases, the chamber sealing is faulty [17].

- Action: Slowly vent the chamber and reseal all 'O'-rings and gaskets, ensuring they are clean and properly seated with a light application of appropriate vacuum grease [17].

- Inspect the Pump and Consumables:

Diagram 1: Diagnostic workflow for a vacuum pump that cannot achieve low pressure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Maintenance and Prevention

Preventative maintenance is the most effective strategy for avoiding unplanned downtime.

- Regular Inspection and Cleaning: Periodically check filters, oil level/condition, and bearings. Clean the pump internals to remove debris and vane dust [23] [25].

- Seal and Bearing Care: Replace mechanical seals and 'O'-rings during service. Lubricate bearings as recommended by the manufacturer to ensure smooth operation [25] [4].

- Proper Operational Procedures: Always ensure motor wiring matches the voltage supply and that rotation direction is correct. For flanges, replace metal gaskets when reassembling and use a light film of vacuum grease on elastomer seals [23] [4].

- System-Specific Practices: Be aware that for mass spectrometers, a routine "air and water check" can provide an early warning of developing leaks before they significantly impact performance [4].

Consequences of Vacuum Failure on Data Integrity in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

In pharmaceutical analysis, instruments like optical emission spectrometers and mass spectrometers rely on high vacuum to generate accurate and reliable data. Vacuum failure can directly compromise data integrity, leading to serious regulatory consequences such as FDA Form-483 observations and warning letters [27]. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers and scientists maintain instrument integrity and ensure data compliance with ALCOA+ principles.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Vacuum Failure Symptoms and Solutions

The table below summarizes common vacuum pump failure signs, their impact on data integrity, and immediate corrective actions.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Impact on Data Integrity | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inability to Reach Operating Vacuum [17] | Vacuum chamber leaks, failed vacuum probe thermistor, contaminated pump oil [28] [29]. | Erroneous analysis of elements like Carbon (C), Phosphorus (P), and Sulfur (S) in short UV wavelength [17]. | Check and reseal vacuum chamber, replace vacuum probe, inspect and change pump oil [17] [28]. |

| Excessive Noise from Pump [28] [29] | Worn or broken vanes, mechanical failure, internal corrosion [28] [29]. | Potential for unexpected shutdown, leading to loss of analytical run and incomplete data sets [30]. | Shut down pump; inspect and replace vanes or bearings; check for mechanical wear [29]. |

| Slow Pump-Down Rate [28] | Contamination in valves or chamber, worn consumable parts, clogged inlet filter [28] [29]. | Longer processing times can delay batch release decisions and risk missing data review deadlines [28]. | Clean or replace inlet filters, inspect and clean vacuum valves, check vanes for wear [29]. |

| Oil Misting or Carbon Dust from Exhaust [29] | Failing oil separator, contaminated oil, or severe vane failure [29]. | Contamination can lead to gradual performance degradation, causing unnoticed data drift over time [31]. | Replace oil and oil separator filters; inspect and replace damaged vanes [29]. |

| Pump Overheating [28] | Poor ventilation, incorrect voltage, internal friction from failing parts [28]. | Overheating can cause automatic shutdown, corrupting electronic data files and audit trails [28] [30]. | Ensure proper ventilation, check motor voltage, and inspect for internal mechanical issues [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Vacuum System Integrity Check

This methodology is critical for investigating suspected vacuum failure and its impact on analytical results, ensuring data generated is attributable, legible, contemporaneous, original, and accurate (ALCOA+) [30].

1. Pre-Experiment Setup and Safety

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE): Wear safety glasses and nitrile gloves.

- Data Integrity Pre-Check: Verify that your user credentials are unique and that audit trails are enabled on the spectrometer's data system to ensure all actions are recorded [30].

- Materials: The vacuum gauge reading, a soft-head screwdriver for fine-tuning (if applicable), and appropriate vacuum grease.

2. Procedure: Isolating the Fault

- Step 1: Initial Assessment. Close the vacuum valve isolating the pump from the main chamber. Monitor the vacuum gauge reading inside the chamber [17].

- Step 2: Chamber Re-sealing Protocol.

- Power down the instrument and follow controlled inlet procedures to re-pressurize the chamber slowly, avoiding contamination from dust particles [17].

- Open the vacuum chamber and meticulously inspect all

O-rings on grating covers, incident windows, and cable feed-throughs. Replace any that are cracked, brittle, or damaged [17]. - Re-seal the chamber, applying a thin layer of vacuum grease sparingly to the

O-rings. Ensure quartz windows are installed in the correct orientation [17]. - Close the relief valve and restart the vacuum pump. Pump for 30-40 minutes and check if the vacuum reaches the required level (e.g., near 100 Torr for a roughing pump). If not, re-check the seals [17].

- Step 3: Vacuum Gauge Calibration.

- If the pump is operational but readings are inaccurate, the vacuum probe or gauge may be faulty. For specific models (e.g., DV-4 spectrometer), fine-tuning the resistor on the vacuum gauge may restore the bridge balance, correcting the reading [17].

3. Data Recording and Documentation

- Record all observations, initial and final vacuum readings, and parts replaced in your laboratory notebook or electronic logbook.

- This documented evidence is crucial for proving data integrity during audits and investigations into out-of-specification (OOS) results [30].

Visual Guide: Vacuum Failure Troubleshooting Workflow

The diagram below outlines the logical decision-making process for diagnosing a vacuum system failure.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Vacuum System Maintenance

The table below lists key reagents and materials essential for maintaining vacuum systems and ensuring data continuity.

| Item | Function | Data Integrity Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Pump Oil (Correct Grade) | Lubricates and seals internal pump components. | Precludes oil misting and vane sticking, avoiding gradual data drift and unexpected pump failure [28] [29]. |

| O-Ring Kit (Instrument-Specific) | Provides airtight seals for vacuum chambers. | Prevents chamber leaks, the primary cause of inability to reach operating vacuum and subsequent erroneous elemental analysis [17]. |

| Oil Separator Filter | Removes oil mist from the exhaust stream in oil-flooded pumps. | Prevents contamination of the system and environment, ensuring consistent pump performance and reliable data generation [29]. |

| Replacement Vanes | Maintain the pumping mechanism in vane-type pumps. | Worn vanes cause slow pump-down rates, leading to longer analysis times and potential delays in batch release decisions [29]. |

| Vacuum Grease | Ensures a seal on O-rings and ground-glass joints. | A proper seal is the first line of defense against vacuum chamber leaks that compromise analytical results [17]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our vacuum pump seems to be working, but the data for carbon and sulfur analysis is consistently out-of-specification. What is the connection? The analysis of light elements like carbon (C), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S) requires a good vacuum in the optical chamber because their emission lines are in the short ultraviolet region. These wavelengths are absorbed by air, so a poor vacuum directly leads to low and erratic signal intensity, causing OOS results [17]. This is a direct physical consequence of vacuum failure on data accuracy.

Q2: During an audit, we were cited for shared login credentials on our spectrometer's computer system. How does this relate to vacuum and data integrity? While seemingly separate, this is a critical data integrity issue. Shared logins violate FDA 21 CFR Part 11 requirements for unique user identification [30]. If a vacuum failure causes anomalous data, the audit trail cannot definitively attribute who performed the analysis or any subsequent reprocessing. This makes it impossible to reconstruct the event fully, breaching ALCOA+ principles and calling all data from that system into question [27] [30].

Q3: We found an incomplete dataset for a batch release where some vacuum pressure log entries were missing. What is the risk? Maintaining a complete dataset is essential for reconstructing the GxP activity [30]. Vacuum pressure is a critical process parameter. Missing log entries, whether on paper or electronic, create an "orphan data" scenario. Regulators would be unable to verify that the instrument operated within specified vacuum limits during analysis, potentially invalidating the entire batch release decision and leading to regulatory action [30].

Q4: What is the most important preventative maintenance task to avoid vacuum-related data integrity issues? Committing to a regular and documented maintenance schedule is paramount. For vacuum pumps, this includes dismantling and inspection approximately every 3,000 hours of operation, draining and changing the oil, and examining drive belts and bearings [28]. This proactive approach prevents gradual performance degradation (data drift) and catastrophic failures (data loss), ensuring the continuity and reliability of your analytical data.

Proactive Maintenance and Operational Best Practices for Reliable Performance

Establishing a Preventive Maintenance Schedule for Peak Performance

Fundamental Concepts: The Role of Vacuum in Spectrometry

All mass spectrometers require a very low-pressure (high vacuum) environment to operate effectively. This vacuum is crucial for minimizing collisions between ions and other gas molecules. Any such collision can cause ions to react, neutralize, scatter, or fragment, all of which will interfere with the resulting mass spectrum and degrade data quality [20].

To achieve the necessary high vacuum, typically between 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁷ torr depending on the instrument geometry, a two-stage pumping system is standard [20]:

- Stage 1: Rough Vacuum. A mechanical pump (e.g., a rotary vane pump) provides the initial pump-down from atmospheric pressure.

- Stage 2: High Vacuum. A turbomolecular or diffusion pump takes over to achieve the final operating pressure.

Performance is monitored using specialized gauges. A thermocouple gauge measures the pressure in the rough vacuum lines, while an ionization gauge measures the high vacuum in the main chamber [20] [32]. A small change in pressure can lead to a significant degradation in performance, making accurate vacuum measurement a critical troubleshooting metric [32].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Vacuum Issues and Solutions

FAQ 1: How do I know if my vacuum system has a leak?

Answer: Indications of a vacuum leak include higher than normal baseline pressure readings, a drop in overall sensitivity, poor high-mass sensitivity, and characteristic changes in the background mass spectrum [4].

Key diagnostic mass peaks to monitor include:

- m/z 18 (Water) and m/z 28 (Nitrogen): On a tight system, these should be relatively low and stable. When their abundances rise, it suggests air and moisture are entering the system [4].

- m/z 32 (Oxygen) and m/z 40 (Argon): The presence of argon is a particularly strong indicator of a real air leak. A nitrogen-to-oxygen ratio of approximately 4:1 is also characteristic of air [4].

FAQ 2: What is the systematic method for locating a vacuum leak?

Answer: A systematic approach is vital to avoid unnecessary disassembly.

Experimental Protocol: Leak Detection Using Tracer Gas

- Preparation: Ensure the mass spectrometer is operational and under vacuum. Access the manual tune mode of the instrument software.

- Mass Monitoring: Set the instrument to monitor specific fragment ions from a tracer gas. Common choices and their monitored masses are:

- Testing: In a well-ventilated area, apply short, controlled bursts of the tracer gas to potential leak points—such as flange connections, seals, the ion source interface, and vacuum gauge ports.

- Observation: An almost instantaneous rise in the monitored mass signals indicates the location of the leak. If the leak is severe and the instrument cannot be safely operated, a solvent like acetone can be carefully used (away from hot surfaces) while watching for a deflection on the vacuum gauges [4].

The following workflow outlines this systematic troubleshooting process:

FAQ 3: My vacuum pump is running but cannot achieve the required low pressure. What should I check?

Answer: This is a common failure mode. The table below summarizes the symptoms, likely causes, and solutions based on systematic troubleshooting [17].

Table: Troubleshooting a Vacuum Pump That Fails to Pump Down

| Observed Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pump stops at 20-30 Torr; analysis data for C, P, S is normal. | Faulty vacuum probe/gauges [17]. | Close the main vacuum valve. If the vacuum reading holds steady, the chamber vacuum is good, but the probe is faulty. | Replace the vacuum probe or recalibrate the gauge per manufacturer's instructions [17]. |

| Pump stops at 20-30 Torr; vacuum drops rapidly when pump valve is closed. | Vacuum chamber sealing failure [17]. | Close the pump valve and observe the vacuum gauge for a rapid pressure rise. | Reseal the main vacuum chamber. This involves inspecting and properly re-lubricating all 'O'-rings on grating covers, incident windows, and cable sockets [17]. |

| Continuous pumping for >12 hours with no improvement; water vapor in pump oil. | Saturated molecular sieve collector or contaminated pump oil [17]. | Inspect the vacuum pump oil. A milky appearance indicates water contamination. | Reactivate the molecular sieve by heating per the manufacturer's guide and change the contaminated pump oil [17]. |

FAQ 4: What are the risks of a power failure, and how can I mitigate them?

Answer: A sudden power failure poses a risk of backstreaming, where the oil from the rotary vane roughing pump can flow back into the higher-vacuum regions of the mass spectrometer (like the diffusion pump and analyzer manifold), contaminating critical components [11].

Mitigation Strategies:

- Physical Placement: Install the roughing pump at a lower level than the mass spectrometer to use gravity to reduce backstreaming risk [11].

- Use of Traps: Install a foreline trap or baffle between the roughing pump and the high-vacuum system to capture backstreaming oil vapors [11].

- Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS): A short-term UPS for the vacuum system can allow for a controlled shutdown during brief power outages [11].

Preventive Maintenance Schedule and Best Practices

A proactive maintenance schedule is the most effective strategy for ensuring peak performance and instrument uptime.

Table: Preventive Maintenance Schedule for Spectrometer Vacuum Systems

| Frequency | Maintenance Task | Key Action / Checkpoint |

|---|---|---|

| Daily | Check Vacuum System [33] | Monitor pressure gauges for normal readings. Listen for unusual pump noises. |

| Weekly | Check for Air/Water Leaks [4] | Perform an air and water check by monitoring m/z 18 and 28 in the background spectrum. |

| Monthly | Inspect Gas Supplies | Ensure continuous supply of instrument gases (e.g., Nitrogen, Helium) and track levels [33]. |

| Quarterly | Clean Ion Source [33] | Follow manufacturer's instructions to clean repeller, capillaries, cones, and other source parts to maintain ionization efficiency. |

| As Recommended by Manufacturer | Change Pump Oil | Replace oil in mechanical (roughing) pumps to prevent contamination and maintain pumping efficiency [33]. |

| Annually / Biannually | Professional Service & Calibration | Schedule a professional service visit for comprehensive checks, leak detection, and mass analyzer calibration [33] [34]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Vacuum Maintenance

Table: Key Materials for Vacuum System Maintenance

| Item | Function / Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Pump Oil | Lubricates and seals mechanical roughing pumps. | Must be the specific grade recommended by the pump manufacturer. Change regularly when contaminated [33]. |

| Tracer Gas (e.g., Chlorodifluoromethane, SF₆) | Used as a detectable probe for locating vacuum leaks. | Use in a well-ventilated area. Monitor specific mass fragments (e.g., m/z 51, 52, 67) for detection [4]. |

| High-Purity Solvents | For cleaning the ion source and other components. | Use solvents specified by the manufacturer (e.g., methanol, acetone) to dissolve contaminants without damaging parts [33]. |

| Vacuum Grease (Apiezon L) | Low vapor-pressure lubricant for O-rings and seals. | A light film on Viton O-rings before reassembly prevents leaks and eases future disassembly [4]. Do not use on GC inlet seals. |

| Replacement Gaskets & O-rings | Form vacuum-tight seals at flanges and connections. | Replace, don't reuse: Metal (copper, gold) gaskets should typically be replaced every time a flange is opened [4]. Keep a stock of common sizes. |

| Foreline Trap / Baffle | Installed between roughing and high-vacuum pumps. | Captures oil vapors from the roughing pump, preventing backstreaming and contamination of the mass analyzer [11]. |

Adhering to a structured preventive maintenance schedule and knowing how to systematically troubleshoot common issues will significantly enhance the reliability of your mass spectrometer, reduce costly downtime, and ensure the generation of high-quality, reproducible data for your research.

Proper Startup and Shutdown Sequences to Prevent Internal Condensation

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, maintaining the integrity of spectrometer vacuum systems is paramount. Internal condensation within these systems poses a significant risk, potentially leading to corrupted data, instrument damage, and costly downtime. This guide provides detailed startup and shutdown sequences and troubleshooting protocols to prevent internal condensation, a critical aspect of troubleshooting spectrometer vacuum pump issues research.

Standard Operating Procedures

Proper Startup Sequence

A meticulous startup procedure is the first defense against condensation by ensuring the system is properly prepared and evacuated.

- Step 1: Pre-Startup Checks. Visually inspect the system. Ensure all vents and ports are securely closed. Verify that the roughing pump oil is at the correct level and appears clean [35].

- Step 2: Initiate Rough Vacuum. Start the mechanical roughing pump (e.g., a rotary vane pump) first. Allow it to operate until the system reaches a low or medium vacuum level, typically below 1 Pa [36]. This initial evacuation removes the bulk of the air and any residual moisture.

- Step 3: Activate High-Vacuum Pump. Once a sufficient rough vacuum is achieved, activate the high-vacuum pump (e.g., a turbomolecular pump). Do not start the high-vacuum pump at atmospheric pressure, as this can cause it to overload and fail [36].

- Step 4: Monitor Pressure. Continuously monitor the vacuum levels until the system stabilizes at its optimal operating pressure. A stable high vacuum indicates that the system is free of significant outgassing and condensation [37].

Proper Shutdown Sequence

An orderly shutdown protects the system during non-operational periods by maintaining a clean, dry internal environment.

- Step 1: Isolate from Sample Introduction. Close the inlet from the sample introduction system or ionization chamber to prevent any backstreaming of vapors [38].

- Step 2: Vent the System Correctly. If venting the system to atmosphere is necessary, always use dry, inert gas such as nitrogen or argon. Never vent with laboratory air, as this introduces moisture which will condense on internal surfaces [37].

- Step 3: Maintain Vacuum (Recommended). For frequent use, the best practice is to leave the vacuum system under a continuous vacuum. As noted in research settings, keeping mass spectrometers under constant vacuum avoids the lengthy process of removing condensed vapors and restarting [39]. The vacuum pump acts as a safeguard, continuously removing any outgassed water vapor.

- Step 4: Final Pump Down. If the system was vented, always initiate a pump-down cycle before the next use. Start the roughing pump, allow it to evacuate the system, and then start the high-vacuum pump as per the startup procedure.

The following workflow summarizes the critical logical relationships in these procedures:

Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses specific symptoms and resolutions related to vacuum system condensation.

Symptom: Contaminated Pump Oil or "Chocolate Milk" Appearance

- Cause: This is a direct result of water condensation and emulsification within the pump oil [35].

- Solution: Immediately replace the contaminated oil. Before starting the pump again, run the system with the gas ballast valve open for at least 30 minutes to purge any remaining condensed vapors from the pump [35]. Investigate and correct the source of the moisture, such as an improper shutdown procedure.

Symptom: Failure to Reach Optimal Operating Pressure

- Cause: An external air leak can introduce moist air, leading to internal condensation and elevated pressure readings. A clogged inlet filter can also prevent the pump from achieving its ultimate vacuum [35].

- Solution: Perform a thorough leak check on the entire system, paying close attention to O-rings, seals, and fittings. Replace the inlet filter if it is dirty or clogged [35].

Symptom: High Background Noise in Mass Spectra

- Cause: A poor vacuum, often due to residual moisture and other gases from internal condensation or air leaks, increases background interference and can induce unwanted ion-molecule reactions [37].

- Solution: Verify the system is holding vacuum. Check for leaks and ensure the vacuum pumps are operating correctly. A high background can indicate that the vacuum is "too low," meaning the pressure is too high [37].

Symptom: Visible Corrosion or Deposits on Internal Components

- Cause: Oxygen from residual air, combined with moisture, can burn and corrode sensitive components like the ion source filament. Condensable vapors can also leave behind solid deposits [35] [37].

- Solution: In severe cases, the system may require professional cleaning. To prevent recurrence, always use a condensate trap (water trap) in the inlet line to capture condensable vapors before they enter the pump, and service this trap regularly [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is it critical to prevent condensation inside my spectrometer's vacuum system? Condensation causes multiple serious problems: it contaminates pump oil, promotes corrosion of internal components (like the ion source filament), increases background interference in your data, and can lead to premature pump failure and costly repairs [35] [37].

Q2: Can I turn off my vacuum pumps when the instrument is not in use? While you can shut down the system completely, best practice for instruments in frequent use is to leave the vacuum pumps running. This maintains a continuous vacuum, preventing moisture from entering and condensing. Shutting down and restarting can be a lengthy process and exposes the system to potential contamination [39].

Q3: What is the purpose of the "gas ballast" function on my roughing pump, and when should I use it? The gas ballast valve allows a small, controlled amount of dry air to enter the pump. This helps to purge condensed vapors (especially water) from the pump oil by preventing them from condensing inside the pump chamber. Use the gas ballast during and after pumping on samples with high moisture content, and always before shutdown to dry the oil [35].

Q4: What type of condensate trap should I use, and how do I maintain it? Condensate traps (or water traps) work by cooling surfaces or using adsorbent media to capture vapors before they reach the pump [35]. They are essential for handling solvents or moist samples. Maintenance is critical: traps with automatic drains should be serviced according to the manufacturer's schedule, while manual traps must be checked and drained regularly to prevent overflow back into the system [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key consumables and materials crucial for maintaining a reliable spectrometer vacuum system.

| Item | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Inert Gas (e.g., Nitrogen, Argon) | Used for venting the vacuum system. Prevents moisture from laboratory air from entering and condensing on internal components [37]. |

| Gas Ballast-Compatible Pump Oil | Specialized oil for roughing pumps that can effectively handle the aeration from the gas ballast function without excessive foaming, aiding in water vapor removal [35]. |

| Inlet Filters & Traps | Protects the vacuum pump. Inlet filters block particulates, while condensate/water traps capture condensable vapors and solvents before they enter and damage the pump [35]. |

| Replacement O-Rings & Seals | Critical for maintaining vacuum integrity. Worn seals are a common source of micro-leaks that introduce moist air. A stock ensures quick replacement during routine maintenance [38]. |

| Digital Thermoelectric Flow Meter | A diagnostic tool placed in the sample introduction line to monitor and ensure consistent sample uptake, helping to identify blockages that could lead to pressure issues [38]. |

| Nebulizer-Cleaning Devices | Safely dislodges particulate build-up in the sample introduction system without damaging delicate components, preventing blockages that disrupt vacuum stability [38]. |

Monitoring and Maintaining Optimal Argon Purity for Sample Integrity

The Critical Role of Argon Purity in Analytical Instrumentation

In scientific research, particularly in fields utilizing Optical Emission Spectrometry (OES) and other high-precision analytical techniques, high-purity argon is not a luxury but a fundamental requirement for data integrity. Argon serves as an inert carrier gas, creating a stable environment for sample excitation and ensuring that the resulting spectral emissions are solely from the sample material itself [40]. When impurities are present in the argon supply—even at trace levels—they can introduce extraneous spectral lines or alter the intensity of the sample's emission spectrum, leading to significant errors in the identification and quantification of elements [40]. For researchers troubleshooting spectrometer systems, understanding and maintaining argon purity is often the key to resolving inconsistent or inaccurate results.

The required purity level is exceptionally high. For sensitive research applications, including the detection of trace elements, argon with a purity grade of 99.9999% (6.0 grade) is often necessary [40]. This ultra-high purity is essential because contaminants like oxygen, nitrogen, water vapor, and hydrocarbons can suppress signals, increase background noise, and ultimately compromise the sensitivity and repeatability of your experiments [41] [40].

Troubleshooting Guide: Argon Purity and Related Systems

This guide addresses common symptoms and their solutions, with a focus on argon purity and the vacuum systems that are critical for spectrometer operation.

Symptom 1: Inaccurate or Irreproducible Analytical Results

- Question: Why are my OES results for trace elements like Carbon, Phosphorus, or Sulfur inconsistent or inaccurate, even after instrument calibration?

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Confirm Argon Purity: Verify that you are using the correct grade of argon (99.999% or better for trace analysis) [40]. Check the certification provided by your gas supplier.

- Check for Contamination: Impurities in the argon, such as oxygen, nitrogen, or moisture, can directly interfere with the emission spectra of light elements [40]. Utilize specialized gas analyzers (e.g., Gas Chromatography with Plasma Emission Detection) to detect impurities at parts-per-billion (ppb) levels [42].

- Inspect Gas Delivery System: Leaks, contaminated regulators, or degraded piping can introduce atmospheric gases or moisture into your ultra-pure argon [41]. Check all connections and consider replacing filters or regulators.

Symptom 2: Vacuum Pump Fails to Achieve or Maintain Required Vacuum

- Question: The spectrometer's vacuum pump cannot pump down to the required vacuum level (e.g., it stalls at 20-30 Torr), affecting the analysis of elements in the short ultraviolet region [17].

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Test System Integrity: Close the vacuum valve. If the vacuum level drops rapidly, it indicates a leak in the vacuum chamber [17].

- Inspect and Reseal: Open the vacuum chamber and meticulously reseal all 'O'-rings, including those on the grating cover, incident window, and cable sockets. Avoid using excessive vacuum grease [17].

- Check Vacuum Components: A faulty vacuum probe thermistor can provide false readings. This component may need replacement or recalibration [17].

- Examine Pump Condition: If the pump oil shows signs of water vapor, the molecular sieve collector may be saturated and require heating to remove moisture [17].

Symptom 3: Increased Signal-to-Noise Ratio and Poor Detection Limits

- Question: Why has the background noise in my spectra increased, reducing the sensitivity for detecting low-concentration elements?

- Investigation & Resolution:

- Audit Argon Quality: This is a classic sign of argon contamination. High-purity argon ensures a stable, low-noise baseline by minimizing background spectral interference [40]. A degraded argon supply is the most likely cause.

- Quantify the Noise: Calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). A declining SNR quantitatively demonstrates the impact of impurities [40].

- Monitor Consistently: Implement continuous purity monitoring at the point of use with devices like the Oilcheck 500 for oil vapors or the FA 500 for humidity to catch contamination events in real-time [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between 5.0 and 6.0 purity argon, and which should I use?

A: The grade indicates the purity level. Grade 5.0 argon is 99.999% pure and is often suitable for standard laboratory applications like gas chromatography where extreme sensitivity is not critical. Grade 6.0 argon is 99.9999% pure and is essential for ultra-trace analysis, such as in OES for detecting minute quantities of nitrogen or other elements, where even minimal impurities can skew results [40].

Q2: How can I practically monitor argon purity in my gas line?

A: Specialized analyzers are required for reliable monitoring. CS Instruments offers solutions like the Oilcheck 500 to detect minimal oil vapour contamination and the FA 500 for precise humidity measurement in argon streams [41]. For comprehensive impurity analysis, Servomex provides gas analyzers using Gas Chromatography and Plasma Emission Detection technology capable of measuring down to ppb levels [42].

Q3: Could my vacuum pump be causing issues that mimic argon purity problems?

A: Yes, absolutely. A failing vacuum pump or a leak in the spectrometer's vacuum system can lead to poor analysis of light elements (C, P, S, B), which is similar to the symptoms caused by contaminated argon [17]. Always check the vacuum system's performance—including pump oil condition, seal integrity, and probe functionality—as part of your diagnostic workflow when analytical results deteriorate.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details key materials and equipment critical for maintaining argon purity and system integrity.

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Argon (Grade 6.0) | Provides a contaminant-free environment for sample excitation in OES. Its 99.9999% purity minimizes background spectral noise, enabling accurate detection of trace elements [40]. |

| Oil Vapor Sensor (e.g., Oilcheck 500) | Monitors for minimal oil vapour contamination in the argon gas stream, which is a common impurity that can degrade analytical performance [41]. |

| Humidity Meter (e.g., FA 500) | Precisely measures water vapour content in argon. Moisture is a key electronegative impurity that must be controlled for reliable operation [41]. |

| Gas Analyzer with Plasma Emission Detector | Used for comprehensive purity analysis. This technology provides highly sensitive and selective measurement of trace impurities in argon, down to ppb levels [42]. |

| Dry Screw Vacuum Pump | Maintains a clean, oil-free vacuum in the spectrometer's optical chamber. Prevents hydrocarbon contamination from pump oil backstreaming, which protects optical components and ensures stability [43]. |

| Helium Mass Spectrometer | The gold-standard tool for leak detection in vacuum systems and gas delivery lines. Essential for identifying minute leaks that can introduce atmospheric contaminants [43]. |

Diagnostic Workflow for Argon and Vacuum System Issues

The diagram below outlines a systematic logical approach to diagnosing issues related to argon purity and vacuum systems in spectrometers.

Sample Preparation Techniques to Minimize Pump Contamination

In the context of troubleshooting spectrometer vacuum pump issues, contamination originating from sample preparation is a prevalent challenge that can lead to significant instrument downtime, costly repairs, and unreliable analytical data. The vacuum pump is the lifeblood of mass spectrometers, and its protection is paramount for maintaining operational integrity. Sample matrices introduced into the system are a primary source of contamination, which can deposit on critical components like the ion source and ultimately degrade vacuum pump performance and oil quality [44]. This guide outlines practical sample preparation strategies and preventative maintenance protocols to shield your vacuum pump from contamination, thereby ensuring robust and reproducible results in research and drug development.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How can my sample preparation method reduce contamination of the spectrometer vacuum pump?

Sample preparation is the first line of defense against vacuum pump contamination. The goal is to minimize the introduction of non-volatile components, salts, and excessive matrix that can volatilize in the ion source, deposit on surfaces, and eventually migrate to or affect the vacuum system [44].

- Problem: Recurrent vacuum pump failure or degradation, characterized by an inability to reach ultimate vacuum, increased background noise in mass spectra, or frequent need for oil changes.

- Solution: Implement the following sample preparation techniques:

- Sample Cleanup: Use techniques like solid-phase extraction (SPE), liquid-liquid extraction, or protein precipitation to remove interfering salts, proteins, and phospholipids from your samples prior to analysis [44].

- Dilution: For samples with a high concentration of matrix components, a simple dilution with a compatible solvent can reduce the total mass of material entering the system.

- Derivatization: For some hard-to-analyze compounds, derivatization can improve volatility, allowing for lower inlet temperatures and reducing the risk of non-volatile residue formation.

- Appropriate Solvent Selection: Use high-purity solvents that are compatible with your instrument's vacuum system and can effectively dissolve your analytes without precipitating matrix components.

FAQ 2: What protective equipment can I install to safeguard the pump from sample-related contamination?

Even with excellent sample preparation, some contaminants may still enter the gas stream. Protective hardware is essential for intercepting these materials before they reach the pump.

- Problem: Despite careful sample cleanup, the vacuum pump oil becomes contaminated quickly, or the pump requires frequent servicing.

- Solution: Install protective devices in the vacuum line between the instrument and the pump.

- Cold Trap: A cold trap (e.g., using liquid nitrogen) is placed before the pump inlet to condense solvent vapors and other volatile contaminants, preventing them from entering and mixing with the pump oil [45] [46].

- Inlet Filter/Particulate Trap: An inlet filter is critical for blocking abrasive particulates from entering the pump's rotating mechanism, which can cause wear and tear [45] [47].

- Knock-Out Pot or Cyclone Separator: These devices use centrifugal force or baffling to separate slugs of liquid, aerosols, and suspended solids from the vacuum air stream, protecting the pump from liquid ingestion and solid deposits [47].

FAQ 3: What routine maintenance is essential for a vacuum pump handling prepared samples?

Regular maintenance is non-negotiable for a vacuum pump exposed to analytical samples. Contaminants from samples will inevitably accumulate in the pump oil over time.

- Problem: Gradual loss of vacuum performance, increased operating temperatures, or unusual pump noises.

- Solution: Adhere to a strict, documented maintenance schedule.

- Regular Oil Changes: Change the pump oil according to the manufacturer's schedule, or more frequently if the oil appears dark or cloudy, or smells of solvents. For demanding applications, this could be as often as weekly [45] [48].

- Oil Inspection: Regularly check the oil level and condition. A milky appearance indicates water contamination, while a dark color suggests oxidation or high contamination with organics [48].

- Use Gas Ballast: When working with condensable vapors (like solvents), always use the pump's gas ballast function. This feature purges solvents from the oil by introducing air, reducing internal corrosion and extending oil life [45].

- Filter Replacement: Replace inlet filters, exhaust filters, and oil mist filters as recommended to ensure they remain effective [48].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: Assessing Pump Oil Contamination Post-Analysis

This protocol allows researchers to monitor the degradation of vacuum pump oil resulting from the analysis of prepared samples.

1. Objective: To visually and mechanically assess the level of contamination in vacuum pump oil following an extended sequence of sample analyses.

2. Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Clean, unused pump oil (reference) | Provides a baseline for color and clarity comparison. |

| Glass test tubes (2) | For holding and comparing oil samples. |

| Vacuum pump oil sampling kit | Allows for safe and clean extraction of oil from the pump. |

| Multimeter/Oscilloscope | For checking pump motor amp draw during ultimate vacuum test. |

| Ultimate vacuum test gauge | To measure the pump's baseline performance. |

3. Procedure: 1. Baseline Measurement: With the pump inlet valve closed, operate the pump and record the ultimate vacuum level and motor amp draw in a maintenance log [48]. 2. Oil Sampling: After the analytical sequence, and with the pump turned off and cooled, extract a small sample of oil from the pump. 3. Visual Inspection: Place the used oil sample in a test tube next to a test tube of clean, unused oil. Compare the color and clarity. Note any cloudiness (water) or darkening (organic contaminants) [48]. 4. Tactile Inspection (if safe): Rub a small amount of oil between your fingers to feel for grit, which indicates particulate contamination [45]. 5. Performance Correlation: Correlate the visual findings with the recorded ultimate vacuum and amp draw. A decline in performance with discolored oil indicates the need for an oil change.

4. Data Interpretation: The table below summarizes common oil conditions and their implications for pump maintenance.

| Oil Appearance | Potential Contaminant | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Clear and amber (like honey) | Minimal contamination | None required; continue normal operation. |