Spectroscopic Analysis of Ancient Artifacts and Paintings: Techniques, Applications, and Cross-Disciplinary Insights for Research Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive overview of spectroscopic techniques applied to the analysis of ancient artifacts and paintings, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Spectroscopic Analysis of Ancient Artifacts and Paintings: Techniques, Applications, and Cross-Disciplinary Insights for Research Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of spectroscopic techniques applied to the analysis of ancient artifacts and paintings, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles and historical evolution of spectroscopy in cultural heritage, details specific methodological applications from pigment identification to material characterization, addresses key challenges and data optimization strategies, and validates techniques through comparative analysis. By synthesizing findings from recent studies and market trends, the article highlights how advanced analytical approaches in heritage science can inform and accelerate innovation in biomedical research and diagnostic development.

The Foundation of Spectroscopy in Cultural Heritage: Principles and Historical Evolution

Spectroscopic techniques form the cornerstone of modern, non-destructive analysis in cultural heritage research. These methods are pivotal for studying invaluable and often fragile ancient artifacts and paintings, as they probe the interaction between light and matter to reveal molecular and elemental composition without causing damage. The fundamental principle involves measuring how materials absorb, emit, or scatter electromagnetic radiation, resulting in spectra that serve as unique fingerprints for pigments, binders, and substrates. The overarching goal in this field is to extract detailed chemical and physical information to inform conservation strategies, authenticate artifacts, and understand historical manufacturing technologies. Recent bibliometric analysis indicates that the application of spectroscopy in cultural heritage has evolved from basic chemical analysis to sophisticated molecular-level characterization, increasingly enabled by multi-technique approaches and portable instrumentation [1].

Core Spectroscopic Techniques: Principles and Applications

The analysis of ancient artifacts utilizes a suite of spectroscopic techniques, each with distinct principles and specific applications. The following table summarizes the key techniques used in the field.

Table 1: Core Spectroscopic Techniques for Ancient Artifact Analysis

| Technique | Acronym | Principle of Interaction | Primary Information Obtained | Typical Applications on Artifacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Raman | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light. | Molecular vibrations, chemical bonds, and crystal structure. | Identification of specific pigments (e.g., vermilion, azurite), binding media, and degradation products [1]. |

| Infrared Spectroscopy | IR (e.g., ATR-FTIR) | Absorption of IR light, exciting molecular vibrations. | Functional groups (e.g., OH, C=O), organic and inorganic compounds. | Analysis of binders (e.g., beeswax, oils), varnishes, and synthetic materials [1]. |

| X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy | XRF | Emission of characteristic secondary X-rays after atom excitation by a primary X-ray source. | Elemental composition (typically elements heavier than sodium). | Determining elemental makeup of metals, pigments, and inks; tracing provenance of raw materials [1]. |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy | LIBS | Analysis of atomic emission from micro-plasma generated by a focused laser pulse. | Elemental composition (including light elements). | Rapid, in-situ elemental analysis and depth profiling of layered structures [1]. |

| Hyperspectral Imaging | HSI | Capture of a series of images across contiguous spectral bands. | Spatial and chemical mapping across a surface. | Visualization of underdrawings, mapping of pigment distributions, and identification of restoration areas [1]. |

| Ultraviolet-Visible Spectroscopy | UV-Vis | Absorption of UV or visible light, promoting electrons to higher energy levels. | Electronic transitions in molecules, often related to color. | Characterization of natural dyes and organic colorants [1]. |

Experimental Protocol: Multi-Modal Analysis of a Fayum Portrait

The following protocol details a macroscale multimodal chemical imaging approach, as pioneered for the non-invasive analysis of a 2nd-century Egyptian Fayum mummy portrait [2]. This methodology integrates three spectroscopic techniques to provide a comprehensive chemical map of the entire artwork.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Materials and Instrumentation for Multi-Modal Analysis

| Item/Reagent | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Artifact/ Painting | The subject of analysis, e.g., a Fayum portrait (a Greco-Roman era mummy mask from Egypt). Must be structurally stable for analysis. |

| Hyperspectral Diffuse Reflectance Imaging System | Measures the light reflected from the surface across numerous wavelengths, providing molecular information for every pixel. |

| Luminescence Imaging System | Detects light emitted by materials after absorbing energy, useful for identifying certain pigments and binders. |

| X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) Scanner | A non-elemental analyzer that bombards the surface with X-rays and measures the characteristic fluorescent X-rays emitted by atoms, providing elemental maps. |

| Calibration Standards | Certified reference materials with known composition for calibrating the spectroscopic instruments and ensuring data accuracy. |

| Data Fusion Software Platform | Custom software to align, process, and overlay the data streams from the three different imaging modalities on a pixel-by-pixel basis. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Pre-Analysis Visual Examination and Documentation:

- Perform a thorough visual examination of the artifact under normal, raking, and UV light.

- Photographically document the artifact's condition at high resolution.

Instrument Calibration:

- Calibrate the hyperspectral, luminescence, and XRF imaging systems using appropriate spectral and elemental calibration standards according to manufacturer specifications.

Data Acquisition - Co-registered Scans:

- Position the artifact securely in the instrument suite.

- Hyperspectral Diffuse Reflectance Scan: Acquire a data cube of the entire painting surface. This involves capturing an image at each narrow spectral band, from the ultraviolet to the short-wave infrared.

- X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) Scan: Raster the XRF spectrometer over the entire surface of the portrait with a resolution matching the hyperspectral data. This generates elemental distribution maps (e.g., for lead, iron, copper) [2].

- Luminescence Scan: Illuminate the portrait with specific wavelengths of light and capture the resulting luminescence emission to identify materials with luminescent properties.

Data Processing and Fusion:

- Use the data fusion software to precisely co-register the three datasets. Each pixel in the image will now contain hyperspectral, elemental, and luminescence data.

- Process the raw data to correct for instrument noise, dark current, and spectral distortions.

Data Interpretation and Material Identification:

- Analyze the fused data cubes to identify materials based on their combined spectral and elemental signatures.

- Example: The identification of "madder lake" pigment (an organic red) in a purple robe is confirmed by its characteristic hyperspectral signature, even though its elemental signature (via XRF) may be weak. Conversely, the presence of lead and iron points to red ochre and lead-based pigments in the skin tones [2].

- Correlate the chemical maps with the visual appearance to understand the artist's technique, such as identifying the use of different tools (fine brush, engraver) based on paint application and composition variations [2].

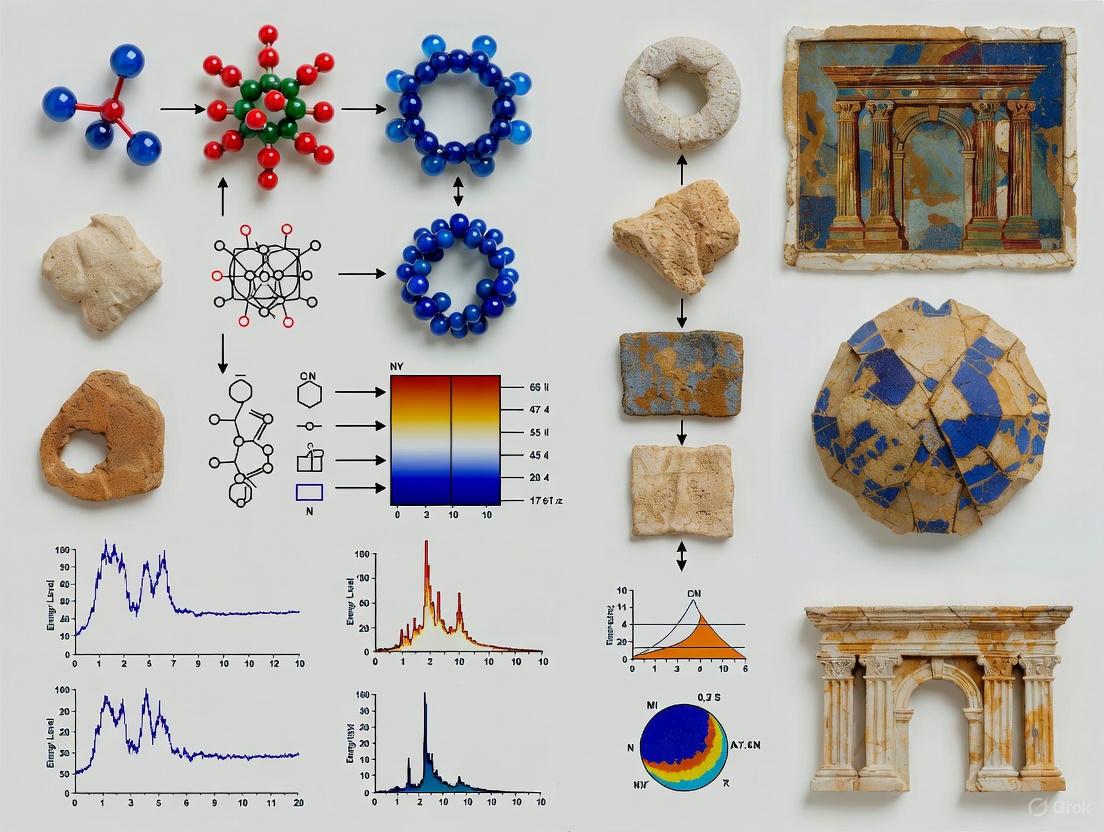

Workflow Visualization

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of advanced spectroscopic techniques continues to revolutionize cultural heritage science. The protocol above, for instance, confirmed the use of the encaustic painting technique (using melted beeswax as a binder) and identified the complex mixture of pigments like red ochre, lead, and charcoal black used to create skin tones and hair in the Fayum portrait [2]. The future of this field points toward increased interdisciplinarity, combining chemistry, materials science, archaeology, and computer science. Key challenges include standardizing complex data analysis and reducing operational costs. Future progress is expected to hinge on accelerating machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) development to enhance pattern recognition and automate complex data interpretation, thereby democratizing access to high-quality analytical tools for smaller institutions [1].

Spectroscopic techniques have revolutionized the field of cultural heritage science, enabling non-destructive analysis of priceless artifacts and artworks. A comprehensive bibliometric analysis of Web of Science literature from 1992 to 2024 has revealed a clear evolutionary pathway for spectroscopy in cultural heritage, characterized by four distinct developmental phases [3]. This progression represents a fundamental shift from basic chemical analysis to sophisticated molecular-level characterization using multi-spectral and multi-assistive techniques [1] [3]. The following sections detail this transformative journey through structured timelines, experimental protocols, and technical workflows that have shaped modern heritage science.

The Four-Phase Evolution of Heritage Spectroscopy

Phase I: Foundation and Initial Exploration (1992-2002)

The initial phase was characterized by pioneering research establishing the fundamental applicability of spectroscopic techniques to cultural heritage materials. Annual publication output remained low, with no more than six articles per year, indicating the emerging nature of the field [3]. Research during this period focused primarily on basic chemical and physical analysis of heritage materials using limited spectroscopic methods [1].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Phase I (1992-2002)

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Annual Publications | ≤ 6 papers per year [3] |

| Primary Focus | Basic chemical and physical analysis of heritage materials [1] |

| Key Techniques | Laser Spectroscopy, Raman Spectroscopy (RS) [3] |

| Research Themes | 24 identified themes, with 50% persisting into subsequent periods [3] |

| Major Contribution | Established foundational applications for cultural heritage artifacts [3] |

Phase II: Growth and Application (2002-2008)

This period witnessed steady growth and expanded application of spectroscopic techniques following the 7th International Conference on Non-Destructive Testing and Microanalytics in 2002 [3]. The research scope deepened, with scientists recognizing spectroscopy's utility for safety management and scientific assessment of cultural heritage [3]. A significant development was the creation of shared databases of information on heritage materials, facilitating more collaborative research approaches [3].

Table 2: Key Characteristics of Phase II (2002-2008)

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Publication Trend | Steady growth [3] |

| Research Themes | 123 themes identified (111 emerging, 15 lost), with 88% theme retention [3] |

| Technological Advancements | Increased data collection using high-tech analytical tools [3] |

| Applications | Material differentiation, degradation monitoring, environmental studies [3] |

Phase III: Consolidation and Multispectral Integration (2008-2015)

Phase III marked a period of methodological consolidation and the beginning of integrated analytical approaches. The Eighth Biennial Conference in 2008 cemented spectroscopy's role as a core tool for cultural heritage research [3]. Applications expanded significantly into conservation science, art technology, and archaeological surveys, with particular emphasis on trace sample analysis [3]. This period saw the rise of multispectral combining methods, where multiple spectroscopic techniques were employed to overcome the limitations of individual methods [3].

Table 3: Key Characteristics of Phase III (2008-2015)

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Research Themes | 307 themes identified (199 emerging, 10 lapsed), with 97% theme retention [3] |

| Primary Applications | Conservation science, art technology, archaeological surveys, trace sample analysis [3] |

| Methodological Shift | Rise of multispectral combining methods [3] |

| Technique Integration | Combined spectroscopic approaches becoming common [3] |

Phase IV: Advanced Innovation and Miniaturization (2015-2024)

The most recent phase represents a period of rapid advancement and technological innovation. Annual publications grew significantly, exceeding 174 per year and projected to surpass 250 by the end of 2024 [3]. Research exploded with novel developments, including increased combination and synchronization of spectroscopic techniques, new assessment methods, and the introduction of portable equipment for on-site analysis [1] [4]. This era has been defined by the synergistic combination of Raman, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), and Infrared Spectroscopies to address diverse heritage materials including artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, stones, and crystals [3].

Table 4: Key Characteristics of Phase IV (2015-2024)

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Annual Publications | >174 papers per year, projected to exceed 250 by end of 2024 [3] |

| Research Themes | 445 themes identified (148 new) [3] |

| Key Technologies | Portable equipment, combined Raman-LIBS-IR techniques, machine learning [1] [3] |

| Materials Analyzed | Diverse heritage forms: artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, stones, crystals [3] |

| Future Directions | AI-powered data processing, enhanced Raman detection, reduced operational costs [1] |

Experimental Protocols in Heritage Spectroscopy

Protocol 1: Multi-Analytical Pigment Identification

Purpose: To identify historical pigments and binders in paintings using a complementary spectroscopic approach [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) instrument

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) instrument

- Surface Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) instrumentation

- Microscopic sampling tools

- Reference spectral databases [4]

Procedure:

- Sample Collection: Obtain microscopic sample of paint layer (≤1 mm) from inconspicuous area of artwork [5]

- LIBS Analysis: Perform elemental characterization using LIBS to identify metallic components in pigments [5]

- FTIR Analysis: Conduct molecular analysis to identify organic binders and some inorganic components [5]

- Raman Analysis: Implement SERS for enhanced detection of pigment molecular fingerprints [5]

- Data Correlation: Integrate elemental (LIBS) and molecular (FTIR/Raman) data for comprehensive material identification [5]

Interpretation: Example identification of chrome orange, lithopone, and iron oxide pigments in "The Birth of Venus" painting, determining the artwork was created in glue tempera technique no earlier than the last quarter of the 19th century [5].

Protocol 2: Non-Invasive Hyperspectral Imaging for Mural Painting Documentation

Purpose: To conduct large-scale, non-invasive mapping and characterization of polychrome surfaces on mural paintings [6].

Materials and Equipment:

- Push-broom hyperspectral imaging sensors (Visible, NIR, SWIR regions)

- Scanning platform or motion system

- Calibration standards

- Multivariate analysis software (PCA, MNF, t-SNE, UMAP) [6]

Procedure:

- System Setup: Position HSI system at appropriate distance (several meters for large murals)

- Spatial-Spectral Scanning: Acquire data-cube with two spatial and one spectral dimension using push-broom scanning

- Spectral Calibration: Collect reference spectra from calibration standards

- Data Processing: Apply dimensionality reduction algorithms to extract relevant information

- Material Mapping: Group and map artists' materials and alteration products based on spectral similarities [6]

Interpretation: Visualization of hidden details, underdrawings, and pentimenti, particularly using SWIR region data, while providing high-quality documentation for conservation monitoring [6].

Workflow Visualization: Multi-Spectroscopic Analysis

Diagram 1: Multi-technique workflow for comprehensive heritage material analysis, integrating elemental and molecular spectroscopy with spatial imaging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Materials and Reference Resources for Heritage Spectroscopy

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| INFRA-ART Spectral Library | Open access database of 1,843 spectral data for 918 cultural heritage materials; provides reference ATR-FTIR, XRF, Raman, and SWIR spectra for comparison [4] |

| Commercial Spectral Databases | Subscription-based reference libraries offering comprehensive spectral data for pigment and binder identification [4] |

| NIST Standard Reference Materials | Certified glass standards (SRM610, SRM612) for instrument calibration and validation of analytical methods [7] |

| Portable XRF Spectrometers | Field-deployable instrumentation for in-situ elemental analysis of artifacts at museums or archaeological sites [1] [4] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging Systems | Push-broom sensors with Si CCD/CMOS (400-1000 nm), InGaAs (900-1700 nm) detectors for non-invasive surface mapping [6] |

| Multivariate Analysis Software | Algorithms for dimensionality reduction (PCA, MNF) and automated classification (t-SNE, UMAP) of spectral data [6] |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advancements, heritage spectroscopy faces ongoing challenges including uneven data availability, analysis complexity hindering standardization, and high operational costs [1] [3]. Raman spectroscopy, while critical, still encounters hurdles in spectrum identification with degraded or contaminated samples [1]. Future progress depends on accelerating machine learning development for enhanced pattern recognition, improving Raman detection sensitivity, and reducing operational costs through more accessible instrumentation [1] [3]. The field is evolving toward increasingly interdisciplinary collaboration, integrating chemistry, materials science, archaeology, art history, and computer science to create holistic conservation strategies [1]. AI-powered data processing promises to democratize access to high-quality analytical tools, enabling even small museums and local conservation teams to benefit from advanced spectroscopic technology [1].

Spectroscopic techniques form the cornerstone of modern analytical methods for investigating cultural heritage. These non-destructive or micro-destructive tools enable researchers to determine the elemental and molecular composition of ancient artifacts and paintings, providing crucial insights into their provenance, authenticity, and manufacturing techniques. The synergistic application of Raman spectroscopy, Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, X-ray Fluorescence (XRF), and Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) has revolutionized archaeological science and conservation, allowing for in-situ analysis of priceless objects without compromising their integrity. This article details the fundamental principles, applications, and standardized protocols for these core spectroscopic families, framed within the context of ancient material research.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Raman Spectroscopy probes molecular vibrations through inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source. When light interacts with a molecule, the scattered light can shift in energy corresponding to the vibrational modes of the chemical bonds present. These shifts provide a molecular fingerprint that enables precise identification of materials, including pigments, binders, and decay compounds [8]. Its non-destructive nature and minimal sample preparation make it particularly valuable for analyzing fragile artworks.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy operates on the principle of molecular bond vibrations absorbing infrared electromagnetic radiation. When IR radiation hits a molecule, covalent bonds absorb energy and vibrate through stretching and bending modes, changing the bond length and angle [9] [10]. The absorbed frequencies are characteristic of specific chemical bonds and functional groups, producing spectra that reveal molecular structures and compositions. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy, especially with Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR) accessories, has expanded applications for analyzing heritage materials with minimal sample preparation [11].

X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) Analysis is an elemental analysis technique that measures characteristic X-rays emitted from materials when exposed to high-energy X-rays. When incident X-rays strike an atom, they can eject inner-shell electrons. As outer-shell electrons fill these vacancies, they emit fluorescent X-rays with energies specific to the element and electron transition involved [12]. This non-destructive method provides qualitative and quantitative information about elemental composition, from sodium to uranium, depending on instrument configuration.

Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) utilizes a focused pulsed laser to generate a micro-plasma on the sample surface. The laser pulse ablates a nanogram quantity of material, creating a transient plasma where constituent elements are atomized and excited. As excited atoms and ions return to ground state, they emit element-specific wavelengths of light [13]. Spectral analysis of this emitted light provides quantitative and qualitative elemental composition data. LIBS offers exceptional spatial resolution and the unique capability for depth profiling by recording spectra from successive laser pulses at the same location [13].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Spectroscopic Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Information Obtained | Spatial Resolution | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light | Molecular vibrations, chemical phases, crystal structure | ~1-2 μm (micro-Raman) | Varies; can detect trace compounds |

| IR Spectroscopy | Absorption of IR radiation by molecular bonds | Molecular structure, functional groups, chemical bonds | ~10-50 μm (FT-IR microscopy) | Major and minor components |

| XRF Analysis | Emission of characteristic X-rays after excitation | Elemental composition (Na-U, depending on instrument) | ~50-200 μm (micro-XRF) | ppm to % range |

| LIBS | Atomic emission from laser-induced plasma | Elemental composition (all elements), depth profiling | ~10-200 μm (micro-LIBS) | ppm to % range |

Theoretical Framework and Molecular Interactions

The underlying theoretical framework for these spectroscopic techniques involves quantum mechanical interactions between matter and electromagnetic radiation. In vibrational spectroscopy (Raman and IR), the energy of incident photons matches the energy difference between vibrational ground and excited states, following the model of a simple harmonic oscillator [10]. The stretching frequency follows Hooke's Law, where the frequency is proportional to the bond force constant and inversely proportional to the reduced mass of the atoms [10].

In atomic spectroscopy (XRF and LIBS), the principles are governed by atomic energy transitions. For XRF, the energy of emitted photons corresponds to the difference between electron energy levels, following Moseley's law which relates X-ray frequency to atomic number [12]. For LIBS, the intensity of atomic emission lines correlates with element concentration in the plasma, enabling quantitative analysis through calibration with reference materials or calibration-free approaches [13].

Figure 1: Fundamental principles of spectroscopic techniques and the type of information they provide

Applications in Ancient Artifact and Painting Research

Material Identification and Authentication

Spectroscopic techniques are indispensable for identifying materials in ancient artifacts and paintings. Raman spectroscopy has been successfully deployed for characterizing ancient pottery, porcelain, and mosaic glass, providing unique "Raman signatures" for different production centers [14]. For example, analysis of 18th-century Capodimonte porcelain established specific Raman profiles for pastes and glazes, enabling definitive attribution of artifacts to this manufacture [14]. Similarly, IR spectroscopy has been crucial in identifying organic binders, varnishes, and restoration materials in historical paintings through characteristic molecular vibrations [10] [11].

XRF analysis has proven invaluable for authenticating ancient metal artifacts through elemental fingerprinting. The technique was instrumental in resolving the provenance of the "Victorious Youth" bronze statue by determining that its elemental composition (copper, tin, and lead) matched ancient copper mines in southern Tuscany, indicating a 4th-century BC origin in Greece or southern Italy [12]. This analysis helped settle a longstanding ownership dispute and facilitated the statue's return to Italy.

LIBS extends these capabilities with exceptional spatial resolution and depth profiling, particularly for investigating layered structures in painted artworks. The technique can sequentially characterize each layer of complex polychrome surfaces, revealing underlying compositions and previous restoration interventions [13]. This capacity is vital for establishing the original manufacturing techniques and documenting the conservation history of cultural objects.

Provenance Determination and Technological Studies

Determining the geographic origin of ancient materials provides crucial insights into trade routes, cultural interactions, and technological transmission. XRF analysis has revealed the origins of significant archaeological artifacts, including the Nebra Sky Disk, where the specific composition of gold, copper, and tin traced the materials to ancient mining sites, illuminating Bronze Age exchange networks [12]. Similarly, analysis of Etruscan bronze mirrors identified distinct production centers through trace element patterns, reconstructing trade networks of these prestigious objects [12].

Recent advances in multi-spectroscopic approaches combine complementary techniques for comprehensive material characterization. A study on ancient Chinese wall paintings employed ATR FT-IR, UV-Vis-NIR, and Raman spectroscopy with principal component analysis (PCA) and nonlinear curve fitting to predict relative contents of mixed mineral pigments with remarkable accuracy (2-3.6% error) [15]. This non-destructive methodology enables precise quantification of pigment mixtures without physical sampling, representing a significant advancement for conservation science.

Table 2: Characteristic Applications of Spectroscopic Techniques in Cultural Heritage Research

| Analytical Question | Recommended Techniques | Specific Examples from Cultural Heritage |

|---|---|---|

| Pigment Identification | Raman, XRF, FORS | Identification of red ochre, cinnabar, azurite, lead white, Prussian blue in Chinese murals [15] |

| Metal Alloy Composition | XRF, LIBS | Analysis of Nebra Sky Disk bronze composition (gold, copper, tin) [12] |

| Provenance Determination | XRF, LIBS, Raman | Tracing Etruscan bronze mirrors to specific production centers [12] |

| Authentication & Forgery Detection | Raman, XRF, IR | Revealing anachronistic pigments in fake "Supper at Emmaus" painting attributed to Caravaggio [12] |

| Depth Profiling & Stratigraphy | LIBS, ATR-FT-IR | Layer-by-layer analysis of polychrome surfaces and complex paint layers [13] [11] |

| Organic Material Analysis | FT-IR, ATR-FT-IR, Raman | Identification of binders, varnishes, and adhesives in paintings [10] [11] |

Experimental Protocols

Standardized Analytical Workflows

Protocol 1: Multi-Technique Pigment Analysis for Wall Paintings

This protocol outlines a non-destructive approach for analyzing mixed mineral pigments in ancient wall paintings, adapted from recent research on Chinese murals [15].

- Sample Preparation: For in-situ analysis, ensure the surface is clean and stable. For laboratory analysis, create simulated reference samples mimicking ancient pigments (e.g., malachite-lazurite mixtures bound with rabbit glue) to establish calibration models.

- Instrumentation and Settings:

- Colorimetry: Measure color coordinates to establish baseline appearance and color differences.

- UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy: Acquire reflectance spectra in the 200-2500 nm range. Use a deuterium-tungsten light source and appropriate detectors for full spectral coverage.

- ATR FT-IR Spectroscopy: Collect infrared spectra with a diamond ATR crystal. Recommended resolution: 4 cm⁻¹; number of scans: 32-64.

- Raman Spectroscopy: Use a 785 nm laser to minimize fluorescence. Power: 10-50 mW at sample; integration time: 10-30 seconds; multiple accumulations.

- Data Analysis:

- Process spectral data using appropriate preprocessing (normalization, baseline correction, derivatives).

- Develop predictive models based on the Beer-Lambert law using principal component analysis (PCA) and nonlinear curve fitting.

- For Raman mapping data, integrate non-negative partial least squares (PLS) analysis for quantification.

- Validate models with reference samples and calculate error rates (target: <5% prediction error).

Protocol 2: LIBS and Raman Combination for Stratigraphic Analysis

This protocol details the combined use of LIBS and Raman spectroscopy for depth profiling of layered heritage materials [13] [8].

- Sample Preparation: Ensure the analysis area is representative and properly stabilized. For portable instruments, position the instrument head perpendicular to the surface with appropriate distance.

- Instrumentation and Settings:

- LIBS Analysis:

- Laser: Nd:YAG, 1064 nm, 5-10 ns pulse duration.

- Energy: 10-50 mJ per pulse (adjust based on material sensitivity).

- Spot size: 50-200 μm (use microscope objectives for micro-LIBS).

- Detection: ICCD spectrometer with time-gating capability.

- Acquisition: Record spectra from successive pulses at the same spot for depth profiling (typically 10-50 pulses).

- Raman Spectroscopy:

- Laser: 532 nm or 785 nm depending on material fluorescence.

- Power: 1-10 mW at sample to avoid damage.

- Integration time: 5-20 seconds with multiple accumulations.

- Spatial resolution: 1-2 μm with microscope objectives.

- LIBS Analysis:

- Data Analysis:

- Process LIBS spectra: background subtraction, peak identification, and normalization.

- Create depth profiles by plotting element intensities versus pulse number.

- Analyze Raman spectra: cosmic ray removal, baseline correction, and peak fitting.

- Correlate molecular information (Raman) with elemental data (LIBS) for comprehensive material characterization.

Figure 2: Decision workflow for spectroscopic analysis of ancient artifacts

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis of Cultural Heritage

| Item | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| ATR Crystals | Internal reflection element for FT-IR spectroscopy | Diamond, ZnSe, or Ge crystals with high refractive index [11] |

| Reference Pigments | Calibration and validation of spectroscopic methods | Certified mineral pigments (azurite, malachite, cinnabar, lead white) [15] |

| Binding Media | Creation of reference samples | Rabbit skin glue, egg tempera, linseed oil matching historical formulations [15] |

| Polishing Materials | Sample preparation for metal analysis | Silicon carbide papers, diamond suspensions (1µm to 9µm grit) |

| Spectroscopic Accessories | Enhancing instrument capabilities | Microscopic attachments, motorized stages, fiber optic probes [13] |

| Calibration Standards | Quantitative analysis verification | Certified reference materials matching artifact composition (bronze, glass, pottery) [12] |

Advanced Data Analysis and Integration

Chemometric Approaches and Machine Learning

Modern spectroscopic analysis of cultural heritage materials increasingly relies on advanced data processing techniques to extract meaningful information from complex spectral datasets. Multivariate data analysis or chemometrics combines the advantages of spectroscopic techniques in terms of time, effort, and multicomponent analysis [11]. For NIR data, which suffers from overlapping absorption bands, arithmetic data pre-processing (normalization, derivatization, and smoothing) helps diminish the impact of extraneous data and maintains focus on the main spectral features [11].

Classification techniques, including unsupervised methods like principal component analysis (PCA) and supervised approaches such as partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLSDA), enable the grouping of artifacts based on their spectral signatures [15] [11]. Regression methods, including principal component regression (PCR), partial-least squares (PLS), and artificial neural networks (ANN), facilitate quantitative analysis of complex mixtures in heritage materials [11]. These approaches have demonstrated remarkable accuracy, with UV-Vis-NIR models achieving approximately 2% prediction error for relative malachite content in malachite-lazurite mixtures [15].

Future Perspectives and Technological Integration

The future of spectroscopy in cultural heritage research points toward increased interdisciplinary collaboration and technological integration. Research themes have evolved from basic chemical analysis to sophisticated molecular-level characterization, now encompassing diverse heritage forms through multi-spectral approaches [3] [1]. Emerging directions include the development of machine learning systems to enhance pattern recognition and automate complex data interpretation, improvement of Raman detection sensitivity for delicate samples, and reduction of operational costs through more accessible instrumentation [3] [1].

The integration of artificial intelligence-powered data processing promises to democratize access to high-quality analytical tools, enabling smaller museums and local conservation teams to benefit from advanced spectroscopic technology [1]. Furthermore, the establishment of standardized spectroscopic databases and experimental protocols will facilitate comparisons among results obtained in different laboratories, enhancing the reliability of these techniques for routine cultural heritage analysis [14].

The analysis of cultural heritage (CH) materials, including ancient artifacts and paintings, presents a unique scientific challenge: how to extract maximum information from historically and artistically invaluable objects while preserving their physical and aesthetic integrity. Spectroscopy technique (ST) has emerged as a powerful analytical tool that addresses this challenge directly, enabling reliable characterization of CH materials through non-invasive or micro-destructive means [16]. These techniques leverage interactions between light and matter to examine various substances' composition, structure, and properties without disrupting the artifact's structure or functionality [16] [17].

The fundamental advantage of spectroscopic methods lies in their ability to provide objective data through the quantification of absorption, emission, scattering, and other light-related phenomena exhibited by cultural materials [16]. This capability has transformed heritage science from an initial phase of limited analysis to an advanced stage characterized by integrating multi-spectral and multi-assistive techniques [16]. This shift reflects a profound evolution from analyzing chemical and physical systems to comprehensive molecular material characterization, now encompassing diverse heritage forms including artifacts, murals, paintings, bronzes, stones, and crystals [16].

The Non-Destructive Analytical Framework

Core Principles of Heritage Spectroscopy

Spectroscopic techniques applied to CH materials operate on the principle that different materials interact with electromagnetic radiation in characteristic ways, producing unique spectral fingerprints that can be interpreted to identify composition, structure, and condition. These non-destructive methods stand in stark contrast to traditional analytical approaches that often require sample removal or preparation that alters the artifact [17]. The varied material properties found in CH objects necessitate tailored spectroscopic approaches, with the synergistic combination of Raman, Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS), and Infrared Spectroscopies proving particularly effective for comprehensive analysis [16].

The non-destructive nature of these techniques makes them ideally suited for investigating irreplaceable cultural objects. As noted in research on pigment analysis for architectural heritage, "Considering the irreplaceable nature of ancient buildings, safe and non-destructive research methods are essential" [17]. This imperative drives the development and refinement of spectroscopic methods that provide maximum information with minimal intervention.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Heritage Spectroscopy

| Reagent/Material | Function in Analysis | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Colloidal Silver (Ag) Pastes | Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) substrate | Enhancing signal for dye identification in historical textiles [18] |

| Reference Pigment Standards | Calibration and validation of spectroscopic measurements | Quantitative analysis of mineral pigments in wall paintings [19] |

| Hydrogel Supports | Minimally invasive extraction of analytes | Identifying madder, turmeric, and indigo dyes via SERS [18] |

| Ion-pairing Reagents | Dispersive liquid-liquid microextraction (IP-dLLME) | Purification and preconcentration of synthetic dyes before HPLC-HRMS [18] |

| Rabbit Glue Binder | Simulation of historical painting techniques | Creating calibrated samples for pigment analysis [19] |

Spectroscopic Techniques for Cultural Heritage: Application Notes

The application of spectroscopic techniques to CH materials has evolved through four distinct phases, from initial exploratory studies (1992-2002) to the current advanced stage (2015-present) characterized by integrated multi-spectral approaches and machine learning integration [16]. This evolution reflects growing recognition of spectroscopy's value in preserving our cultural legacy.

Technique-Specific Applications

Table 2: Spectroscopic Techniques for Cultural Heritage Analysis

| Technique | Primary Information | Applications in Cultural Heritage | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy | Molecular composition, crystalline structure | Pigment identification [17], characterization of ancient pottery, porcelain, and glass [14] | Fluorescence interference, weak signal for some materials |

| X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) | Elemental composition | Analysis of pigment elements in architectural structures [17], terracotta figurines [17] | Limited penetration depth, semi-quantitative without standards |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) | Molecular bonds, functional groups | Identification of binders, varnishes, and degradation products [18] | Sample preparation often required for transmission mode |

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy (LIBS) | Elemental composition, depth profiling | Stratigraphic analysis of painted layers [16] | Micro-destructive, requires careful control of laser parameters |

| UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy | Electronic transitions, colorimetry | Quantitative analysis of mixed pigments [19], condition assessment | Primarily surface information, limited molecular specificity |

Advanced Integrated Approaches

Recent advancements emphasize the combination of multiple spectroscopic techniques to overcome individual limitations and provide comprehensive material characterization. For instance, the integration of µ-EDXRF, Raman spectroscopy, and X-ray diffraction (XRD) has enabled complete characterization of degradation products, mineral substrates, and pigments in microsamples from prehistoric artworks [18]. Similarly, the combination of Raman spectroscopy and LIBS provides complementary molecular and elemental information for complete pigment and substrate analysis [16].

The synergy between spectroscopic techniques and computational methods represents another significant advancement. Machine learning algorithms, including convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and generative adversarial networks (GANs), are increasingly employed to optimize spectral data processing, enhance detection accuracy, and predict material properties [16] [20]. These computational approaches help address challenges related to data complexity and uncertainty in heritage science [16].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Non-Destructive Analysis of Mixed Mineral Pigments in Wall Paintings

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for predicting relative pigment content in ancient wall paintings using multiple spectroscopic techniques, based on research by Applied Spectroscopy [19].

Figure 1: Workflow for Quantitative Pigment Analysis

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable colorimeter for color difference measurements

- Attenuated Total Reflection Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR FT-IR) spectrometer

- Ultraviolet-Visible-Near Infrared (UV-Vis-NIR) spectrophotometer

- Raman spectrometer with mapping capability

- Reference pigment standards (e.g., malachite, lazurite)

- Historical binding media (e.g., rabbit glue for simulated samples)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Create simulated pigment samples using historical materials and techniques. Mix mineral pigments (e.g., malachite-lazurite) with rabbit glue in known ratios to create calibration standards [19].

- Accelerated Aging: Subject simulated samples to controlled aging conditions to replicate long-term environmental effects observed in ancient paintings.

- Multi-Technique Data Acquisition:

- Perform colorimetric measurements to establish color difference metrics

- Collect ATR FT-IR spectra in the range of 1041 cm⁻¹, focusing on characteristic absorption bands

- Acquire UV-Vis-NIR reflectance spectra for quantitative analysis

- Conduct Raman mapping to establish spatial distribution of pigment components

- Multivariate Data Analysis:

- Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce spectral dimensionality

- Utilize nonlinear curve fitting for quantitative modeling

- Employ empty modeling methods combined with non-negative partial least squares for Raman mapping data

Validation and Quality Control: The protocol achieves high prediction accuracy with errors approximately 2% for UV-Vis-NIR models and less than 3.6% for ATR FT-IR models at specific wavenumbers. Raman mapping approaches demonstrate errors between 0.01-9.30% depending on the analytical method [19].

Protocol 2: On-Site Analysis of Museum Objects Using Portable Spectroscopy

This protocol describes an integrated approach for non-destructive analysis of fragile museum objects, adapted from methodologies applied to porcelain artifacts in museum collections [14].

Figure 2: Museum Object Analysis Workflow

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer

- Portable Raman spectrometer with multiple laser wavelengths (e.g., 785 nm, 532 nm)

- Fiber Optic Reflectance Spectroscopy (FORS) system

- High-resolution digital camera for documentation

- Portable optical microscope for surface examination

Procedure:

- Preliminary Examination: Conduct visual inspection under standardized lighting conditions. Document object condition with high-resolution photography.

- Non-Invasive Elemental Analysis:

- Use portable XRF to identify key elements present in the object

- Perform multiple measurements across different areas to account for heterogeneity

- Utilize fundamental parameters or empirical calibration for semi-quantitative analysis

- Molecular Characterization:

- Employ portable Raman spectroscopy with appropriate laser wavelength and power to avoid damage

- Collect spectra from multiple points to establish material consistency

- Compare results with reference spectral databases for cultural materials

- Color and Surface Analysis:

- Implement FORS to document color properties and identify colorants

- Correlate spectral reflectance data with material identification

- Data Integration:

- Combine elemental and molecular information for comprehensive material identification

- Cross-validate results from different techniques to improve reliability

- Contextualize findings with historical and artistic information

Technical Considerations:

- Laser power in Raman spectroscopy must be carefully controlled to prevent damage to sensitive materials

- XRF penetration depth limitations require consideration of layered structures

- Integration of findings from multiple techniques enhances interpretation accuracy

- Portable instrument performance should be regularly validated with standard reference materials

Spectroscopic techniques represent a paradigm shift in cultural heritage science, offering unprecedented capabilities for analyzing irreplaceable artifacts while respecting their preservation needs. The non-destructive imperative driving their development and application continues to yield innovative methodologies that balance analytical depth with material integrity. As spectroscopic technologies evolve—particularly through integration with machine learning and advanced data processing—their role in heritage conservation and interpretation will undoubtedly expand, enriching our understanding of cultural legacy while ensuring its transmission to future generations.

Application Note: Integrating Spectroscopic Analysis with Modern Publishing Frameworks

The spectroscopic analysis of ancient artifacts and paintings represents a specialized research domain that is increasingly shaped by global collaboration and evolving academic publishing trends. This application note details how modern research into ancient materials, such as pigments from Chinese wall paintings, intersects with technological advancements in scholarly communication. The non-destructive nature of techniques like Raman spectroscopy and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy enables the in-situ analysis of priceless cultural heritage objects, facilitating international studies without the need to transport artifacts [15] [21]. Concurrently, the academic publishing landscape is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by Artificial Intelligence (AI), Open Science principles, and blockchain technology, which collectively enhance the transparency, speed, and global reach of disseminating complex scientific data [22] [23]. This note outlines protocols for spectroscopic analysis and demonstrates how contemporary publishing trends are creating new pathways for collaborative research that transcends traditional geographical and institutional boundaries.

Key Spectroscopic Techniques for Ancient Materials

The accurate analysis of ancient pigments and binding media requires a suite of complementary, non-destructive spectroscopic techniques. These methods allow researchers to determine the chemical composition, molecular structure, and geographical provenance of materials, which is crucial for authentication, dating, and conservation efforts [24] [21].

Table 1: Core Spectroscopic Techniques in Heritage Science

| Technique | Core Principle | Data Output | Key Application in Ancient Artifact Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Raman Spectroscopy [24] [21] | Measures slight energy changes in laser light scattered by molecular vibrations. | Sharp spectral bands corresponding to specific molecular bonds. | Identifies specific pigments (e.g., vermilion, cadmium yellow) and can detect biological colonizations on artworks [21] [25]. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy [15] [21] | Measures absorption of infrared light to probe molecular bond vibrations. | Absorption spectrum indicating functional groups and molecular structure. | Analyzes complex mixtures and organic materials like binders (e.g., rabbit glue) and varnishes; effective for malachite identification [15] [21]. |

| X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) Spectroscopy [15] [21] | Measures secondary X-rays (fluorescence) emitted from a material when irradiated with X-rays. | Elemental composition spectrum. | Provides elemental "fingerprinting" to map pigments (e.g., Hg in vermilion, Au in gold leaf) in artifacts and manuscripts [21]. |

| UV-Vis-NIR Spectroscopy [15] | Measures reflection or absorption of ultraviolet, visible, and near-infrared light. | Spectral reflectance curve. | Used for colorimetry and, combined with modeling, to predict the relative content of mixed pigments like malachite-lazurite with high accuracy [15]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and software solutions essential for conducting and disseminating research in this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Spectroscopic Analysis and Publishing

| Item/Software | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Mineral Pigment Standards (e.g., Malachite, Lazurite, Cinnabar) [15] | Simulated samples for calibration and method validation in quantitative spectroscopic analysis. |

| Rabbit Glue [15] | Traditional binding medium used to create historically accurate simulated paint samples for testing. |

| Spectrometer Software Libraries [24] | Databases containing reference spectra for pigments and compounds, enabling rapid chemical identification. |

| Colorimeter [24] | Provides precise, objective measurement of color, crucial for detecting subtle material differences imperceptible to the human eye. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) Software [15] | Statistical tool for analyzing complex spectral data, identifying patterns, and quantifying pigment mixtures. |

| AI-Powered Literature Review Tools [22] | Automates the sifting of vast academic literature, helping researchers stay current with global developments. |

| Blockchain-Based Research Logs [22] | Creates an immutable and transparent record of peer review and research findings, enhancing trust in collaborative studies. |

| Preprint Servers [22] [23] | Enables rapid dissemination of initial findings and establishes priority, fostering early community feedback. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Non-Destructive Analysis of Mixed Pigments in Wall Paintings

This protocol, adapted from a 2024 study, describes a methodology for predicting the relative content of mixed mineral pigments using multiple spectroscopic techniques [15].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Equipment:

- Samples: Simulated paint samples mimicking ancient compositions (e.g., mixtures of malachite and lazurite bound with rabbit glue) [15].

- Spectrometers: UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer, ATR FT-IR spectrometer, Raman spectrometer with microscope [15] [21].

- Software: Data analysis software capable of performing Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and non-negative partial least squares (PLS) regression [15].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of simulated paint samples with known, varying ratios of target pigments (e.g., malachite and lazurite) using a period-appropriate binding medium such as rabbit glue. These samples serve as a calibrated set for model development [15].

- Spectral Data Acquisition:

- Analyze each simulated sample using UV-Vis-NIR, ATR FT-IR, and Raman spectroscopy.

- For Raman analysis, place the sample under the microscope and center a single pigment particle. Shine the laser to acquire the spectrum [21].

- Ensure consistent measurement conditions (e.g., laser power, integration time, spectral range) across all samples.

- Model Development: Collect all spectral data and develop a predictive model using advanced mathematical methods.

- Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to reduce the dimensionality of the spectral data and identify key patterns [15].

- Apply the Beer-Lambert law, which links absorbance to concentration, and use nonlinear curve fitting to create a model that predicts pigment content from spectral features [15].

- Integrate non-negative PLS analysis, particularly for Raman mapping data, to quantify compositions [15].

- Model Validation: Test the predictive model on the simulated samples to calculate the error of prediction. The cited study achieved errors as low as 2% for malachite content using UV-Vis-NIR models [15].

- Application to Ancient Artifacts: Once validated, apply the model to spectral data acquired non-destructively from ancient wall paintings to predict the relative pigment content in unknown mixtures [15].

- Data Sharing and Publication: Share spectral data in open repositories as per funder mandates. Disseminate findings through open access journals or preprint servers to accelerate community feedback and collaborative interpretation [22] [23].

Protocol for Leveraging Publishing Trends in Global Collaborative Research

This protocol outlines how to utilize modern publishing infrastructures to enhance the reach, integrity, and impact of global collaborative research on ancient materials.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Software:

- Collaborative Platforms: Cloud-based tools with real-time editing and shared document storage (e.g., Google Workspace, Overleaf) [22].

- AI Screening Tools: Software for initial manuscript checks, plagiarism detection, and reference validation [22] [23].

- Preprint Servers: Discipline-specific servers (e.g., arXiv, SSRN) for rapid dissemination.

- Blockchain System: A platform for creating immutable records of research contributions and peer review activities [22].

- Social Media: Professional networks (e.g., LinkedIn, Bluesky, Threads) and academic social platforms [22] [26].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Team Formation and Workflow Setup: Establish a global research team across multiple institutions. Implement an integrated research workflow management system to assign tasks, track progress, and manage centralized documents [22].

- AI-Assisted Manuscript Preparation: Use AI-powered tools during the writing phase to generate initial literature reviews, validate references, and ensure language polishing. Adhere to emerging ethical guidelines on AI usage in publications [22] [23].

- Open and Transparent Peer Review: Upon submission, engage in open peer review or cross-institutional review networks to increase accountability and diversity of feedback. Consider using platforms that leverage blockchain technology to immutably record the review process, enhancing transparency [22].

- Open Access Publication and Data Sharing: Publish the final research in an Open Access (OA) journal to maximize reach and democratize knowledge. Fulfill stricter data-sharing mandates by depositing raw spectral data and analysis code in public repositories to ensure research reproducibility [22] [23].

- Post-Publication Promotion and Engagement: Actively promote the published work through social media channels and targeted communication to niche academic communities. Use these platforms to foster direct author-reader engagement, leading to richer discussion and crowdsourced insights [22] [26].

The integration of advanced, non-destructive spectroscopic techniques with transformative trends in academic publishing is creating a powerful paradigm for studying the spatial and temporal distribution of ancient materials. Protocols that combine precise chemical analysis with open, collaborative, and technology-driven dissemination are setting a new standard. This synergy not only deepens our understanding of cultural heritage but also ensures that the resulting knowledge is generated and shared more rapidly, transparently, and inclusively across the global research community.

Advanced Methodological Applications: From Pigment Identification to Multi-Technique Synergy

The scientific analysis of cultural heritage artifacts provides an indispensable window into the materials, techniques, and trade practices of historical civilizations. Within this field, the identification of pigments and binders forms a cornerstone for authentication, dating, and informing conservation strategies. Vibrational spectroscopy, particularly Raman spectroscopy and Infrared (IR) spectroscopy, has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive toolkit for researchers seeking to unravel the material composition of ancient artifacts and paintings [27]. These techniques provide molecular-level identification of both inorganic and organic components, enabling the reconstruction of historical palettes and the study of degradation mechanisms, all while minimizing physical interaction with precious objects.

Theoretical Foundations and Technical Principles

Raman Spectroscopy

Raman spectroscopy operates on the principle of inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser source. When light interacts with a molecule, the scattered light can shift in energy corresponding to the vibrational modes of the chemical bonds present. These shifts provide a molecular fingerprint unique to the substance being analyzed [27].

Key advantages of Raman spectroscopy include:

- Non-destructive and non-invasive character, allowing in-situ analysis without mechanical or chemical pre-treatments.

- High molecular specificity and sensitivity (ppm range).

- High spectral resolution (≤ 1 cm⁻¹) and spatial resolution (≤1 μm).

- Minimal interference from water, enabling the study of hydrated samples [27].

A significant challenge is fluorescence emission from certain pigments or binding media, which can overwhelm the weaker Raman signal. This has been mitigated through technological advances such as Spatially Offset Raman Spectroscopy (SORS), which also enables the exploration of subsurface stratigraphy in layered artifacts [27].

Infrared Spectroscopy

IR spectroscopy, in contrast, measures the absorption of infrared light by molecules, which occurs at frequencies corresponding to the energies of molecular vibrations. Different regions of the IR spectrum offer distinct advantages:

- Mid-IR (MIR: 4000–400 cm⁻¹): Reveals fundamental vibrational transitions, ideal for identifying organic functional groups [28] [29].

- Far-IR (600-10 cm⁻¹): Particularly effective for characterizing inorganic pigments, many of which have characteristic lattice vibration bands in this region [28].

- Near-IR (NIR: 7500–4000 cm⁻¹): Features overtone and combination bands of fundamental vibrations (e.g., O-H, N-H, C-H). The weaker absorption in this region allows for greater penetration depth, making it suitable for studying underlying layers in a painting stratigraphy [29].

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, especially when combined with microscopy or portable systems for in-situ analysis, has become a standard tool in heritage science [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for In-Situ Raman Spectroscopy of Wall Paintings

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in the analysis of pigments from the Boyary I rock art site [30] and other ancient manuscripts and paintings [27].

1. Equipment and Reagents:

- Portable Raman spectrometer (e.g., with 532 nm, 785 nm laser options)

- Calibration standards (e.g., silicon wafer)

- Microscope attachment for spatial resolution ≤1 μm

- Soft brushes and inert swabs for gentle surface cleaning

2. Safety Precautions:

- Wear appropriate laser safety goggles.

- Ensure the artifact is stabilized and supported to prevent accidental damage.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Instrument Calibration. Verify the wavelength calibration of the spectrometer using a standard such as a silicon wafer (peak at 520.7 cm⁻¹) before analysis.

- Step 2: Preliminary Visual Examination. Document the artifact with high-resolution photography under visible, UV, and IR light to identify areas of interest.

- Step 3: Spot Analysis. Select a representative area for analysis. If using a portable system, gently place the spectrometer probe head perpendicular to, and in light contact with, the surface. For micro-Raman, focus the laser on the sample surface.

- Step 4: Spectral Acquisition. Use a laser power of ≤1 mW at the sample surface to avoid potential damage. Accumulate 10-30 scans with an integration time of 1-10 seconds per scan to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Step 5: Data Processing. Process the raw spectra by applying cosmic ray removal, baseline correction, and smoothing algorithms. Compare the resulting spectrum against reference spectral libraries of pigments [30] [27].

4. Interpretation: The identification of hematite (Fe₂O₃) in red pigments by its characteristic bands at about 225, 291, 410, 495, and 610 cm⁻¹ is a typical outcome [30]. The detection of calcium oxalate whewellite can indicate the degradation of an organic binder [30].

Protocol for FT-IR Analysis of Paint Binders and Stratigraphy

This protocol draws from non-invasive studies of Renaissance paintings using FT-NIR spectroscopy [29] and far-IR microspectroscopy [28].

1. Equipment and Reagents:

- FTIR spectrometer with NIR, MIR, and Far-IR capabilities (e.g., Thermo Scientific Nicolet iS50)

- Reflectance module for contactless measurements

- ATR microspectroscopy accessory (e.g., SurveyIR diamond ATR)

- Reference materials (e.g., linseed oil, egg yolk, animal glue)

2. Safety Precautions:

- The instrument compartment should be purged with dry, CO₂-free air when measuring in the MIR region.

3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample/Area Selection. For micro-analysis, a minute sample may be required. For non-invasive in-situ analysis, select a representative and discreet area.

- Step 2: Spectral Acquisition Mode Selection.

- For organic binders (lipids, proteins): Use the NIR region (7500-4000 cm⁻¹). Acquire spectra in reflection mode as a sum of 200 scans at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹ [29].

- For inorganic pigments (e.g., vermilion, zinc white): Use the Far-IR region (1800-50 cm⁻¹). For micro-samples, use the ATR accessory with 256 scans at 8 cm⁻¹ resolution [28].

- Step 3: Data Processing. Transform reflection spectra in the NIR range to pseudo-absorbance (Log(1/R)). Process MIR reflection spectra using the Kramers-Kronig transform. For complex NIR data, use multivariate analysis (e.g., Principal Component Analysis - PCA) to differentiate binders [29].

4. Interpretation: In the NIR spectrum, a combination band at about 4265 cm⁻³ (assigned to the combination of C-H stretching and C=O stretching of esters) is indicative of a drying oil, whereas a band at about 4865-4875 cm⁻³ (assigned to the combination of N-H stretching and amide II) suggests a proteinaceous tempera [29]. In the Far-IR, the identification of zinc white is confirmed by a sharp absorption peak at 380 cm⁻¹ [28].

Data Presentation and Analysis

The following tables summarize key data obtained from the spectroscopic analysis of artists' materials, providing a reference for researchers.

Table 1: Identification of Common Historical Pigments by Raman Spectroscopy [27]

| Pigment Name | Color | Chemical Composition | Characteristic Raman Bands (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vermillion | Red | HgS (Mercuric sulphide) | 252, 282, 343 |

| Red Ochre | Red | Fe₂O₃ (Ferric oxide) | 225, 291, 410, 495, 610 |

| Azurite | Blue | 2CuCO₃·Cu(OH)₂ | 400, 432, 768, 838, 1096, 1428 |

| Lead White | White | 2PbCO₃·Pb(OH)₂ | 1054 |

| Orpiment | Yellow | As₂S₃ | 135, 154, 179, 200, 292, 308, 353, 384 |

Table 2: Key Spectral Signatures for Binder Identification in the NIR Region [29]

| Binder Type | Chemical Characteristics | Key NIR Absorption Bands (cm⁻¹) & Assignments |

|---|---|---|

| Drying Oil (e.g., Linseed) | Esters of glycerol and long-chain fatty acids | ~4265 (C-H str + C=O str of ester); ~5185 (2 x C-H str of CH₂); ~7000 (2 x C-H str of CH₃) |

| Proteinaceous (e.g., Egg Yolk) | Proteins and phospholipids | ~4865-4875 (N-H str + Amide II); ~6620 (2 x N-H str); ~5150 (2 x C-H str of CH₂) |

| Animal Glue | Protein (collagen) | ~4865 (N-H str + Amide II); ~6620 (2 x N-H str) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis of Cultural Heritage

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Portable Raman Spectrometer (785 nm laser) | In-situ analysis; reduces fluorescence in many organic materials [27]. |

| FTIR Spectrometer with Far-IR & NIR capability | Comprehensive analysis of both organic binders and inorganic pigments [28] [29]. |

| Diamond ATR (Attenuated Total Reflectance) accessory | Micro-analysis of minute samples without preparation, for MIR and Far-IR [28]. |

| Reference Pigment Collections (e.g., Forbes Collection) | Critical reference standards for spectral comparison and positive identification [28]. |

| Spectral Libraries (Digital) | Databases of Raman and FTIR spectra for pigments, binders, and degradation products [27]. |

| Siccative Oils, Egg Yolk, Animal Glue | Reference materials for binder identification and studying aging processes [29]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The logical sequence of analysis, from non-invasive in-situ methods to more detailed micro-destructive techniques, can be visualized as a workflow.

Diagram 1: Analytical Workflow for Pigment and Binder Analysis

Case Studies and Applications

Analysis of Boyary I Rock Art Pigments

Raman spectroscopy analysis of red pigments from the Boyary I rock art site (Khakassia) identified hematite as the primary coloring agent. Furthermore, the detection of whewellite (calcium oxalate) exclusively in areas with pigment residues suggested it resulted from the decomposition of the original organic binder, providing clues about the painting's technology and subsequent degradation [30].

Far-IR Identification of Pigments in a Qing Dynasty Wardrobe

Far-IR microspectroscopy was pivotal in analyzing pigments from an 18th-century Chinese wardrobe. The technique clearly identified vermilion (HgS) in red layers and orpiment (As₂S₃) in yellow layers based on their characteristic lattice vibrations in the far-IR region. This identification provided key evidence for the artifact's authenticity, as these pigments were consistent with materials used in historical Chinese lacquerware [28].

Binder Differentiation in Renaissance Paintings

FT-NIR spectroscopy successfully distinguished between lipid-based (drying oils) and protein-based (egg tempera) binders in model samples simulating the complex stratigraphy of Renaissance paintings. The deeper penetration of NIR radiation also allowed researchers to gain information about the composition of the preparatory layers (ground) beneath the paint films, which is crucial for understanding the artist's technique [29].

Raman and IR spectroscopy provide a powerful, complementary suite of techniques for the non-invasive and micro-destructive analysis of historical pigments and binders. The protocols and data outlined in this application note offer researchers a framework for conducting their investigations. As spectroscopic technology continues to advance, particularly in portability and sensitivity, its role in uncovering historical palettes, verifying authenticity, and guiding the conservation of our shared cultural heritage will only become more profound.

The scientific analysis of ancient artifacts provides a window into the technological achievements, trade networks, and daily life of past societies. This field relies on advanced spectroscopic techniques to non-destructively characterize material composition and degradation states, which is particularly crucial for irreplaceable cultural heritage objects. Within the broader context of spectroscopic analysis of ancient artifacts and paintings, this article presents structured application notes and experimental protocols for assessing three critical material classes: bronze alloys, stone tools, and crystalline pigments. The integration of complementary analytical approaches enables researchers to reconstruct ancient manufacturing technologies, identify raw material sources, and develop informed conservation strategies, thereby preserving humanity's shared cultural legacy for future generations.

Analytical Techniques for Ancient Material Characterization

A range of spectroscopic techniques is employed in archaeometric studies, each providing unique insights into elemental composition, molecular structure, and material properties.

Table 1: Core Spectroscopic Techniques in Archaeological Science

| Technique | Acronym | Information Provided | Typical Applications | Spatial Resolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy | LIBS | Elemental composition | Bronze alloy analysis, pigment identification | Micrometer scale |

| X-Ray Fluorescence | XRF | Elemental composition | Metal alloy quantification, stone provenance | Millimeter scale |

| Raman Spectroscopy | - | Molecular structure, crystalline phases | Pigment identification, corrosion products | Micrometer scale |

| Laser-Induced Fluorescence | LIF | Molecular fluorescence | Organic materials, degradation studies | Micrometer scale |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy | FT-IR | Molecular bonds, functional groups | Mineral identification, firing temperatures | Millimeter to micrometer |

| Near-Infrared Spectroscopy | NIR | Overtone and combination bands | Bronze patinas, organic coatings | Millimeter scale |

Bronze Alloy Composition and Corrosion Analysis

Analytical Challenges and Multi-Technique Approaches

Bronze artifacts present particular challenges due to surface corrosion that often obscures the original bulk composition. As noted in studies of ancient bronzes, the limited depth resolution of techniques like XRF means that "readings may be inaccurate due to heterogeneity caused by the cooling process, degradation/weathering, and cleaning or other preservation treatment" [31]. This has led to the development of specialized protocols for in-situ analysis, including the use of filters to enhance precision and multiple measurements to account for surface heterogeneity [31].

Portable XRF (pXRF) has become particularly valuable for analyzing museum collections where object transport or sampling is prohibited. Research on Bronze Age figurines from the National Museum of Damascus demonstrated that reliable quantitative data could be obtained through a defined analytical protocol that included "the use of filters in the excitation path" and attention to "the heterogeneity of the alloys" [32]. For binary copper-tin alloys, the ratio of tin Kα to Lα lines has been established as a robust semiquantitative criterion to assess surface alteration [32].

Complementary laser-based techniques provide additional dimensions of information. As highlighted in a recent review, "Three spectroscopic techniques—Raman spectroscopy, laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS), and laser-induced fluorescence (LIF)—are poised to transform the archaeology industry" [33]. LIBS offers precise elemental analysis by focusing "a high-powered laser on a tiny area of the artifact" to generate a plasma whose emitted light reveals elemental composition [33]. Raman spectroscopy excels in identifying corrosion products such as atacamite and paratacamite, while LIF detects fluorescence signals from organic materials and pigments [33] [34].

Bronze Analysis Experimental Protocol

Application Note: Elemental and Molecular Characterization of Ancient Bronze Alloys

Objective: To determine the bulk composition of copper-based alloys and characterize corrosion products through a non-destructive multi-technique approach.

Materials and Equipment:

- Portable XRF spectrometer with filter capability (e.g., Bruker III-SD)

- Portable Raman spectrometer with 785 nm laser

- LIBS instrument with pulsed Nd:YAG laser

- Optical microscope for surface examination

- Certified reference materials for copper alloys

Procedure:

- Visual Examination: Document surface characteristics, color variations, and corrosion patterns under controlled lighting.

- Site Selection: Identify multiple analysis points representing different surface conditions (3-5 points minimum).

- pXRF Analysis:

- Configure instrument with 12 mil Al + 1 mil Ti filter

- Set parameters to 40 kV, 1.5-4 μA, 30-60 seconds acquisition time

- Maintain consistent measurement geometry (5 × 7 mm beam size)

- Calculate Sn Kα/Lα ratio to identify potential surface alteration

- LIBS Analysis:

- Focus high-powered laser on selected micro-areas (avoiding visually distinct corrosion)

- Collect plasma emission spectra across UV-Vis range

- Determine quantitative estimation of tin, lead, and arsenic concentrations

- Raman Spectroscopy:

- Analyze green and brown corrosion products with 785 nm excitation

- Identify mineral phases using reference spectral database

- Settings: 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, 10-30 s accumulation, 10-20 mW power

- Data Integration: Combine elemental and molecular data to reconstruct original composition and corrosion history

Quality Control:

- Analyze certified reference materials with known composition at beginning and end of session

- Monitor Sn Kα/Lα ratios for consistency across measurements

- Employ principal component analysis (PCA) for statistical classification of samples [35]

Figure 1: Bronze Artifact Analysis Workflow

Stone Artifact Provenance and Technology

Material Sourcing and Technological Analysis

Stone artifact analysis provides insights into trade networks, resource management, and technological choices of ancient societies. Research on Chinese Bronze Age sites has revealed that "stone tools were still an important element in the toolkits of craft production, agriculture, and daily life" despite the period's association with bronze metallurgy [36]. At Panlongcheng, a major Erligang culture site (ca. 1500–1300 BCE), diverse raw materials including "slate, granite, mudstone, gneiss, schist, sandstone, limestone and other stones" were identified through petrographic analysis [36].

Provenance studies combine geological surveys with material characterization to trace resource exploitation strategies. At Panlongcheng, researchers determined that approximately "81% of stone artifacts are made of materials that are not available in the local area" but were instead sourced from the Dabie Mountain region, indicating organized procurement strategies [36]. This challenges previous assumptions about Bronze Age resource utilization and highlights the continued importance of lithic technology even in periods defined by metal use.

Stone Analysis Experimental Protocol

Application Note: Provenance Determination and Technological Analysis of Stone Artifacts

Objective: To identify raw material types, determine geological sources, and understand manufacturing techniques through petrographic and geochemical analysis.

Materials and Equipment:

- Polarizing microscope with digital imaging

- Thin section preparation system

- Portable XRF spectrometer

- FT-IR spectrometer with reflectance attachment

- Geological reference collection

- SEM-EDS system (if micro-sampling permitted)

Procedure:

- Macroscopic Analysis:

- Document typological classification, dimensions, and use-wear patterns

- Identify raw material based on physical characteristics (color, texture, hardness)

- Thin Section Petrography:

- Prepare standard 30 μm thin sections from inconspicuous locations (if permitted)

- Analyze mineral composition, texture, and structure under polarized light

- Compare with geological reference samples

- Geochemical Characterization:

- Conduct non-destructive pXRF analysis on multiple points

- Measure major and trace elements (Si, Al, Fe, K, Ca, Ti, Rb, Sr, Zr)

- Use FT-IR to identify mineralogical components through molecular vibrations

- Data Interpretation:

- Compare elemental composition with geological sources using HCA (Hierarchical Cluster Analysis)

- Calculate SiO₂/Al₂O₃ concentration ratios for provenance grouping [37]

- Correlate material properties with artifact function and manufacturing techniques

Quality Control:

- Analyze geological standards with known composition

- Perform multiple measurements to account for material heterogeneity

- Cross-validate mineral identification through complementary techniques (petrography + FT-IR)

Table 2: Stone Artifact Compositional Data from Panlongcheng [36]