Spectroscopic Analysis: Principles, Techniques, and Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of spectroscopic analysis, a fundamental technique in scientific research and industrial applications.

Spectroscopic Analysis: Principles, Techniques, and Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of spectroscopic analysis, a fundamental technique in scientific research and industrial applications. It explores the core principles of how light interacts with matter to reveal chemical composition, structure, and concentration. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the content covers foundational theories, diverse methodological approaches, and practical applications—from quality control in pharmaceuticals to advanced biomedical imaging. It also addresses troubleshooting, optimization strategies, and the integration of new technologies like AI and Quantum Cascade Lasers, offering insights into future trends shaping biomedical and clinical research.

The Science of Light and Matter: Core Principles of Spectroscopic Analysis

Spectroscopic analysis represents a cornerstone of modern analytical science, enabling researchers to determine the composition, structure, and properties of matter through its interaction with radiative energy. Within this field, the terms spectroscopy and spectrometry describe complementary aspects of the science, with the former representing the theoretical study of interactions between matter and radiated energy, and the latter concerning the practical measurement of these interactions to obtain quantitative data [1]. This distinction, while subtle, is fundamental to understanding the application of these techniques across scientific disciplines.

In pharmaceutical and biopharmaceutical development, these methodologies have become indispensable tools for drug discovery, process monitoring, and quality control [2]. The evolution of these techniques from Isaac Newton's initial prism experiments in the 1600s to today's sophisticated AI-enhanced instruments demonstrates their enduring scientific value [1] [3]. This technical guide examines the theoretical underpinnings, methodological applications, and experimental protocols that define contemporary spectroscopic and spectrometric practice, with particular emphasis on their crucial role in advancing pharmaceutical sciences.

Theoretical Framework: Core Principles and Definitions

Fundamental Concepts and Terminology

The theoretical foundation of spectroscopic analysis rests on the principle that atoms and molecules exhibit characteristic interactions with electromagnetic radiation, producing unique spectral "fingerprints" that reveal their identity and concentration [4]. When electromagnetic radiation passes through or interacts with a substance, atoms and molecules respond by absorbing specific wavelengths and emitting others, creating a spectrum that can be measured and interpreted [4].

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), spectroscopy is formally defined as "the study of physical systems by the electromagnetic radiation with which they interact or that they produce" [5]. This establishes spectroscopy as the theoretical science investigating how matter behaves when subjected to radiative energy. In contrast, spectrometry refers specifically to "the measurement of such radiations as a means of obtaining information about the systems and their components" [5], positioning it as the practical measurement component of the field.

The Spectroscopy-Spectrometry Distinction

The relationship between spectroscopy and spectrometry represents a paradigm of complementary scientific domains:

Spectroscopy encompasses the theoretical framework for understanding energy-matter interactions, the quantum mechanical principles governing these interactions, and the interpretation of resulting spectral patterns [1] [4]. It provides the scientific basis for predicting how substances will respond to electromagnetic radiation across different regions of the spectrum.

Spectrometry comprises the methodological approaches, instrumental techniques, and quantitative procedures for acquiring spectral measurements [1] [5]. This includes the design of spectrometers, development of measurement protocols, and implementation of calibration methodologies that transform theoretical principles into actionable analytical data.

This distinction explains why techniques such as mass spectrometry are classified under spectrometry rather than spectroscopy, as they measure mass-to-charge ratios of ions rather than directly measuring the interaction of matter with electromagnetic radiation [5].

Technical Classification of Methodologies

Classification by Type of Radiative Energy and Interaction

Spectroscopic techniques can be systematically categorized according to the specific form of radiative energy employed in the analysis and the nature of the interaction between this energy and the material under investigation [3]. This classification framework provides researchers with a logical structure for selecting appropriate methodologies for specific analytical challenges.

Table 1: Classification of Spectroscopic Techniques by Radiative Energy and Interaction Mechanism

| Technique Category | Radiative Energy Source | Interaction Mechanism | Primary Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atomic Spectroscopy | Visible/UV light [3] | Electronic transitions of outer shell electrons [3] | Elemental composition and concentration [3] |

| Molecular Spectroscopy | Visible/UV/IR radiation [3] | Molecular rotations, vibrations, and electronic states [3] | Molecular structure, functional groups, bonding [3] |

| Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy | Radio waves [3] [4] | Nuclear spin transitions in magnetic field [2] [3] | Molecular structure, conformational details [2] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Ionizing energy [1] [5] | Ionization and mass-to-charge separation [1] [5] | Molecular mass, structural fragments [1] |

| X-ray Spectroscopy | X-rays [3] | Excitation of inner shell electrons [3] | Elemental composition, crystal structure [3] |

| Scattering Spectroscopy | Visible/IR/NIR light [3] | Elastic or inelastic scattering [3] | Molecular structure, crystallinity [3] |

Spectral Regions and Corresponding Analytical Techniques

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses a broad range of energies, each providing unique information about molecular and atomic structure. Different spectroscopic techniques exploit specific regions of this spectrum to probe particular aspects of chemical systems.

Table 2: Electromagnetic Spectrum Regions and Corresponding Spectroscopic Techniques

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Associated Techniques | Information Revealed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gamma-ray | <0.01 nm [4] | Gamma-spectrometry [6] | Nuclear structure [7] |

| X-ray | 0.01 nm - 10 nm [4] | X-ray diffraction (XRD) [2] | Crystal structure, elemental analysis [3] |

| Ultraviolet (UV) | 10 nm - 400 nm [4] | UV-Vis spectroscopy [2] [4] | Electronic transitions, concentration [2] [4] |

| Visible | 400 nm - 700 nm [4] | UV-Vis, Colorimetry [7] [4] | Electronic structure, color measurement [7] |

| Infrared (IR) | 700 nm - 1 mm [4] | FT-IR, NIR [2] [4] | Molecular vibrations, functional groups [2] [4] |

| Microwave | 1 mm - 1 m [4] | Electron spin resonance [7] | Molecular rotations, unpaired electrons [7] |

| Radio wave | 1 m and above [4] | NMR, MRI [6] [4] | Molecular structure, tissue composition [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Size Exclusion Chromatography with Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (SEC-ICP-MS) for Protein-Metal Interaction Studies

Purpose: To differentiate between ultra-trace levels of metals interacting with proteins and free metals in solution during monoclonal antibody development [2].

Principle: SEC-ICP-MS combines separation of molecular species by size with highly sensitive elemental detection, enabling researchers to study metal-protein interactions that can affect therapeutic protein efficacy, safety, and stability [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- Size Exclusion Chromatography System: High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system with SEC column for biomolecular separation [2]

- ICP-MS Instrument: Mass spectrometer with inductively coupled plasma ionization source for trace metal detection [2]

- Mobile Phase Buffer: Aqueous buffer compatible with both protein stability and ICP-MS requirements (typically ammonium acetate or ammonium bicarbonate) [2]

- Metal Standards: Certified reference materials for calibration (cobalt, chromium, copper, iron, nickel) [2]

- Protein Samples: Monoclonal antibodies co-formulated and stored under controlled conditions [2]

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Reconstitute protein samples in appropriate mobile phase buffer at concentrations typically ranging from 0.1-1.0 mg/mL [2].

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject samples onto SEC column equilibrated with mobile phase. Use flow rate of 0.5-1.0 mL/min with column temperature maintained at 4-25°C depending on protein stability requirements [2].

- Elemental Detection: Direct column effluent to ICP-MS nebulizer. Monitor specific metal isotopes (e.g., ⁵⁹Co, ⁵²Cr, ⁶³Cu, ⁵⁶Fe, ⁶⁰Ni) with time-resolved analysis [2].

- Data Analysis: Correlate retention times of metal signals with protein elution profile. Metals co-eluting with protein peaks indicate metal-protein interactions, while earlier eluting peaks represent free metals [2].

- Quantification: Use external calibration curve method with serial dilutions of metal standards for quantification of both protein-bound and free metal concentrations [2].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research: This protocol provides critical insights for biopharmaceutical development by characterizing metal-protein interactions that may impact drug stability and efficacy, particularly for monoclonal antibodies and other protein therapeutics [2].

Protocol: Inline Raman Spectroscopy with Machine Learning for Real-Time Bioprocess Monitoring

Purpose: To enable real-time measurement of product aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing using hardware automation and machine learning [2].

Principle: Raman spectroscopy measures inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, providing molecular vibration information that serves as a chemical fingerprint. When combined with machine learning algorithms, it enables real-time monitoring of critical quality attributes during biomanufacturing [2] [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Raman Spectrometer: Instrument with laser source (typically 785 nm for biological applications), diffraction grating, and CCD detector [2] [8]

- Immersion Probe: Fiber-optic probe suitable for inline insertion into bioreactors, with compatible optical window materials [2]

- Calibration Standards: Polystyrene standards for wavelength calibration, Raman shift calibration standards [2]

- Cell Culture Media: Appropriate media for specific cell line (e.g., Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell culture media) [2]

- Data Analysis System: Computer with machine learning algorithms (e.g., convolutional neural networks, principal component analysis) [8]

Procedure:

- System Configuration: Install Raman immersion probe directly into bioreactor vessel, ensuring proper orientation and aseptic installation [2].

- Instrument Calibration: Perform wavelength calibration using polystyrene standard. Verify intensity response with appropriate Raman standards [2].

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect Raman spectra continuously or at predetermined intervals (e.g., every 38 seconds) throughout bioprocess cycle [2].

- Spectral Preprocessing: Apply preprocessing algorithms to remove cosmic rays, correct baseline drift, and normalize spectral intensity [2] [8].

- Machine Learning Analysis: Process spectra through trained algorithms to identify and eliminate anomalous spectra. Apply chemometric models for 27 critical components in cell culture including nutrients, metabolites, and product quality attributes [2].

- Real-Time Monitoring: Generate control charts to detect normal and abnormal conditions (e.g., bacterial contamination). Implement feedback control loops for process adjustment when critical parameters deviate from specifications [2].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research: This protocol enables real-time monitoring of biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes, allowing for improved process understanding, reduced calibration efforts, and enhanced product quality control through measurement of critical quality attributes including aggregation and fragmentation [2].

Experimental Workflows and Signaling Pathways

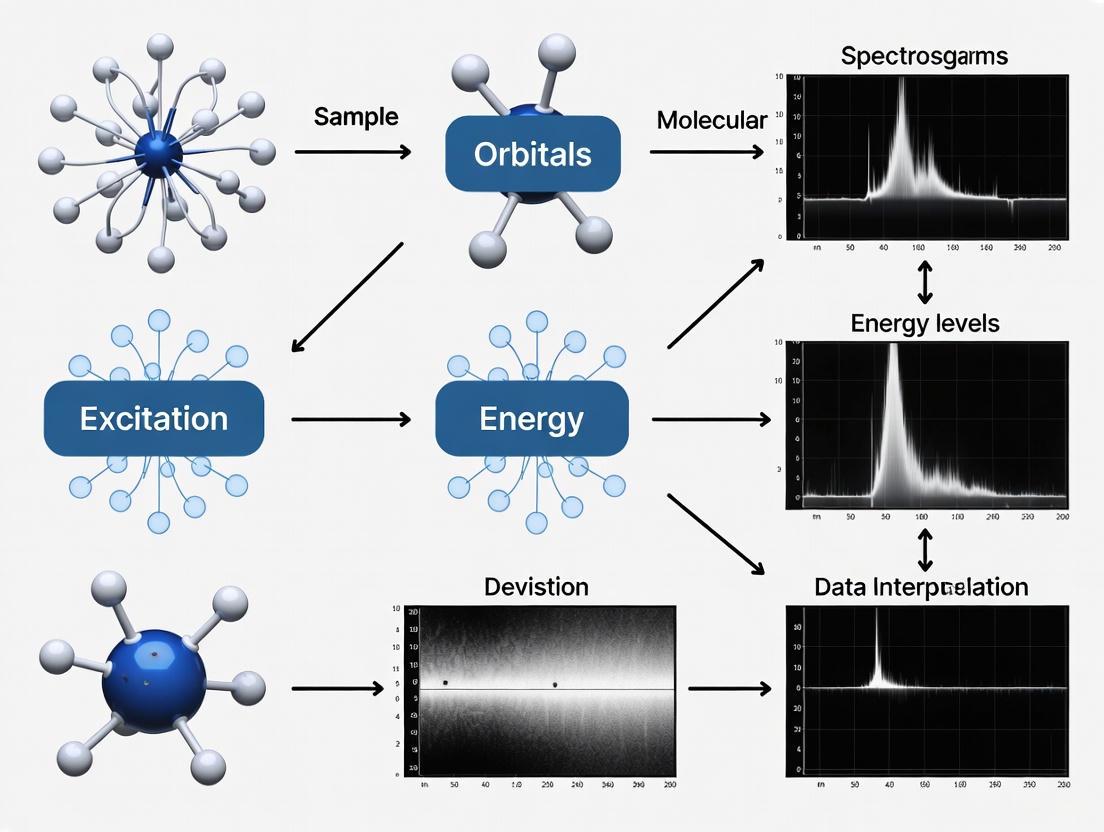

The relationship between theoretical spectroscopy and practical spectrometry, along with their implementation in pharmaceutical research, can be visualized through the following workflow:

Spectroscopy to Spectrometry Workflow

The implementation of specific spectroscopic techniques in pharmaceutical analysis follows standardized experimental pathways:

Spectroscopic Analysis Experimental Pathway

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

AI-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy in Drug Development

The integration of artificial intelligence with Raman spectroscopy represents a significant advancement in pharmaceutical analysis, particularly for drug development and quality control applications. Deep learning algorithms including convolutional neural networks (CNNs), long short-term memory networks (LSTM), and Transformer models are revolutionizing the interpretation of Raman spectral data by automatically identifying complex patterns in noisy data sets and reducing the need for manual feature extraction [8].

Implementation Protocol:

- Spectral Acquisition: Collect high-resolution Raman spectra using instrumentation equipped with quantum cascade lasers tuned for specific molecular vibrations (e.g., amide I band from 1700-1600 cm⁻¹ for protein analysis) [8].

- Data Preprocessing: Apply noise reduction algorithms, baseline correction, and spectral normalization to standardize input data [8].

- Model Training: Implement deep learning architectures using training datasets of known compounds with associated spectral signatures. Employ data augmentation techniques to enhance model robustness [8].

- Pattern Recognition: Deploy trained models to identify spectral features correlated with critical quality attributes, including drug aggregation states, conformational changes, and impurity profiles [8].

- Real-Time Monitoring: Integrate AI models with inline Raman systems for continuous monitoring of biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes, enabling automatic detection of process deviations and quality anomalies [8].

This approach has demonstrated particular utility in monitoring mAb (monoclonal antibody) aggregation and fragmentation during clinical bioprocessing, with measurements achievable every 38 seconds, significantly enhancing process control and product quality assurance [2].

Spectroscopic Techniques in Pharmaceutical Quality Control

Table 3: Spectroscopic Quality Control Applications in Pharmaceutical Development

| Technique | QC Parameter Measured | Application Example | Regulatory Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS [2] | Trace metal impurities | Monitoring transition metals in therapeutic proteins [2] | ICH Q3D Elemental Impurities [2] |

| FT-IR [2] | Protein secondary structure | Stability testing of protein drugs under varying conditions [2] | ICH Q1A(R2) Stability Testing [2] |

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy [2] | Concentration, purity | Protein A affinity chromatography monitoring at 280 nm [2] | USP <857> UV-Vis Spectrophotometry [2] |

| NMR Spectroscopy [2] | Molecular structure, conformation | Higher-order structure analysis of biologics [2] | ICH Q6B Specifications [2] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy [2] | Protein denaturation, aggregation | In-vial monitoring of heat-induced BSA denaturation [2] | Non-invasive quality control [2] |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The implementation of spectroscopic and spectrometric methodologies requires specific research reagents and materials designed to ensure analytical accuracy, precision, and reproducibility.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Technical Function | Application Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Cascade Lasers [1] | Mid-infrared light source with precisely tunable wavelength | FT-IR spectroscopy, particularly for amide I band analysis (1700-1600 cm⁻¹) [1] | |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography Columns [2] | Biomolecular separation by hydrodynamic volume | SEC-ICP-MS analysis of metal-protein interactions [2] | |

| Atomic Spectrometry Standards [2] | Calibration and quantification reference materials | Trace metal analysis by ICP-MS and ICP-OES [2] | |

| Raman Calibration Standards [2] | Wavelength and intensity calibration | Validation of Raman spectrometer performance [2] | |

| Chiral Derivatization Reagents | Enantiomeric separation and analysis | Chiral spectroscopic analysis of pharmaceutical compounds | |

| Deuterated Solvents [2] | NMR spectroscopy without interfering proton signals | High-resolution NMR analysis of pharmaceutical compounds [2] | |

| Surface-Enhanced Raman Substrates [2] | Signal amplification for low-concentration analytes | SERS detection of trace impurities and contaminants [2] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of spectroscopic analysis continues to evolve through technological innovations and methodological advancements. The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning represents the most significant trend, with deep learning algorithms increasingly applied to spectral interpretation, pattern recognition, and predictive modeling [8]. These approaches address traditional challenges including background noise, complex data sets, and model interpretation while enhancing analytical accuracy and efficiency [8].

Miniaturization and portability constitute another major trend, with the development of handheld spectrometers enabling field-based analysis and point-of-care diagnostic applications [5]. Advancements in detector technologies, particularly in previously challenging spectral regions such as terahertz spectroscopy, have expanded the practical application of spectroscopic techniques across wider electromagnetic ranges [5].

In pharmaceutical analysis, the movement toward real-time process monitoring and control using inline spectroscopic techniques aligns with Quality by Design (QbD) principles and Process Analytical Technology (PAT) initiatives [2]. The continued development of interpretable AI methods, including attention mechanisms and ensemble learning techniques, addresses the "black box" challenge of deep learning models and enhances regulatory acceptance of these advanced analytical approaches [8].

The distinction between spectroscopy as the theoretical science investigating energy-matter interactions and spectrometry as the practical measurement of these interactions provides a fundamental framework for understanding modern analytical methodology. This complementary relationship enables the continuous advancement of pharmaceutical research and development, from initial drug discovery through manufacturing and quality control.

The integration of sophisticated spectroscopic techniques with artificial intelligence and automation represents the future trajectory of the field, promising enhanced analytical capabilities, improved process understanding, and accelerated therapeutic development. As these technologies continue to evolve, the synergy between theoretical spectroscopy and practical spectrometry will undoubtedly yield increasingly powerful tools for scientific discovery and pharmaceutical innovation.

Spectroscopic analysis is a scientific methodology that involves the study of the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation [9]. This field is fundamental to modern science, enabling researchers to determine the arrangement of atoms and electrons in molecules based on the amounts of energy absorbed or emitted during changes in molecular structure or motion [10]. The technique operates on the principle that when electromagnetic radiation passes through or reflects off a substance, atoms and molecules respond by absorbing specific wavelengths and emitting others, creating a unique spectral "fingerprint" that reveals information about the substance's composition and properties [4]. This analytical approach provides exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting single atoms among 10²⁰ atoms of a different species and measuring frequency shifts as small as one part in 10¹⁵ [9].

The foundation of all spectroscopic techniques lies in the electromagnetic spectrum, which spans an immense range of frequencies and wavelengths [11]. By measuring how samples interact with different regions of this spectrum—from high-energy gamma rays to low-energy radio waves—scientists can extract detailed information about molecular structure, chemical composition, and physical properties across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, materials science, and clinical diagnostics [4].

Fundamental Principles of the Electromagnetic Spectrum

Wave-Particle Relationships

Electromagnetic radiation exhibits both wave-like and particle-like properties, with its behavior described by several fundamental relationships. The radiation is composed of oscillating electric and magnetic fields that propagate through space at the constant speed of light (c = 2.9979 × 10¹⁰ cm/s in vacuum) [11]. The distance between successive wave crests is defined as the wavelength (λ), while the frequency (ν) represents the number of wave cycles that pass a given point per second, measured in hertz (Hz) [12] [9].

These parameters are interrelated through the equation: c = νλ [12]

where the speed of light (c) is constant, establishing an inverse relationship between frequency and wavelength: as frequency increases, wavelength decreases, and vice versa [12].

In particle terms, electromagnetic radiation consists of photons, discrete packets of energy quantized according to the equation: E = hν

where E is the energy of a single photon, h is Planck's constant (6.6261 × 10⁻²⁷ erg·s in cgs units), and ν is the frequency [11]. This relationship demonstrates that photon energy increases proportionally with frequency, meaning that higher frequency (shorter wavelength) radiation carries more energy per photon [12] [11].

The Electromagnetic Spectrum Ranges

The electromagnetic spectrum encompasses all possible frequencies of electromagnetic radiation, traditionally divided into regions based on how the radiation interacts with matter. Table 1 provides the definitive wavelength, frequency, and energy ranges for these regions, illustrating the tremendous span of over 21 decades in wavelength that characterizes the full spectrum [11].

Table 1: Electromagnetic Spectrum Regions and Their Characteristic Ranges

| Band | Wavelength Range | Frequency Range | Energy Range | Decades Covered |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radio Waves | > 100 cm | < 300 MHz | --- | > 3.0 |

| Microwave | 1 mm - 1 m | 0.3 - 300 GHz | --- | 3.0 |

| Infrared (IR) | 1 - 100 μm | 3 - 300 THz | 0.01 - 1.2 eV | 3.0 |

| Visible Light | 400 - 700 nm | 430 - 750 THz | 1.8 - 3.9 eV | 0.3 |

| Ultraviolet (UV) | 10 - 400 nm | 750 THz - 30 PHz | 3.9 - 124 eV | 1.5 |

| X-Ray | 0.25 - 100 Å | 30 - 12,000 PHz | 0.12 - 50 keV | 3.0 |

| Gamma-ray (γ) | < 0.25 Å | > 12,000 PHz | > 50 keV | > 8.5 |

The optical band (combined UV, visible, and near-IR) covers only a trivial portion of the complete electromagnetic spectrum, yet it is particularly significant for spectroscopic analysis due to its interaction with valence electrons in molecules [11]. Each spectral region probes different aspects of molecular and atomic structure, making specific regions suitable for particular analytical applications [4].

Spectroscopic Techniques by Energy Region

High-Energy Spectroscopy (Gamma-Ray and X-Ray)

High-energy spectroscopic techniques utilize photons with sufficient energy to probe nuclear and core-electron structures. Gamma-ray spectroscopy, dealing with the highest energy photons (>50 keV), primarily investigates nuclear energy transitions and is employed in nuclear physics, radiology, and nuclear medicine [11] [4]. The extremely short wavelengths of gamma-rays (<0.25 Å) enable study of nuclear properties and high-energy physical processes [11].

X-ray spectroscopy operates in the 0.12-50 keV energy range (approximately 0.25-100 Å) and is divided into soft X-ray (0.12-5 keV) and hard X-ray (5-50 keV) regions [11]. This technique probes the inner-shell electrons of atoms and is particularly valuable for elemental analysis and structural determination. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measures the kinetic energy of electrons ejected from core atomic orbitals when samples are irradiated with X-rays, providing quantitative information about elemental composition and chemical states [13]. The NIST X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database contains critical evaluations of over 22,000 photoelectron and Auger-electron spectral lines for reference purposes [13].

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

UV-Vis spectroscopy encompasses the ultraviolet (10-400 nm) and visible (400-700 nm) regions of the electromagnetic spectrum [11] [4]. This technique measures electronic transitions where molecules absorb energy, promoting electrons from ground state to higher energy molecular orbitals [14]. For organic chromophores, these typically involve π–π, n–π, σ–σ, and n–σ transitions, while transition metal complexes exhibit color due to multiple electronic states associated with incompletely filled d orbitals [14].

The fundamental principle governing quantitative UV-Vis analysis is the Beer-Lambert law: A = log₁₀(I₀/I) = εcL

where A is the measured absorbance, I₀ and I are the incident and transmitted intensities, ε is the molar absorptivity (in M⁻¹·cm⁻¹), c is the concentration of the absorbing species, and L is the path length through the sample [14]. This relationship enables the determination of analyte concentrations in solution by measuring absorbance at specific wavelengths.

UV-Vis instrumentation typically operates between 175-3300 nm, with technical specifications requiring controlled beam sizes (2-12 mm diameter) and specific sample volumes (>0.2 mL for liquids) or solid sample dimensions (0.5×0.5 cm to 10×10 cm) [15]. Modern UV-Vis spectrophotometers incorporate monochromators to select specific wavelengths, with spectral bandwidth being a critical parameter affecting resolution and measurement accuracy [14].

Infrared (IR) and Raman Spectroscopy

Infrared spectroscopy operates in the 1-100 μm wavelength range (3-300 THz), corresponding to energies of 0.01-1.2 eV [11]. This technique probes molecular vibrations, including stretching, bending, and rotational modes, which are characteristic of specific functional groups within molecules [4]. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopic analysis, conducted using instruments like the Bruker-EQUINOX55 with resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, provides high-quality vibrational spectra for compound identification and structural elucidation [16].

Raman spectroscopy is a complementary technique to IR spectroscopy that measures inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, typically from a laser in the visible, near-infrared, or near-ultraviolet range [13]. The Raman effect occurs when photons interact with molecular vibrations, resulting in energy shifts that provide information about vibrational modes in the system. Databases such as the Raman Spectroscopic Library of Natural and Synthetic Pigments contain reference spectra for 56 common pigments known to have been used before 1850, organized by color for easy identification [13].

Microwave and Radio Wave Spectroscopy

Microwave spectroscopy (1 mm - 1 m wavelength, 0.3-300 GHz frequency) investigates rotational transitions in molecules [4]. The energy in this region is sufficient to cause changes in the rotational energy levels of gas-phase molecules, providing information about molecular geometry, bond lengths, and angles [9].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy utilizes the radio frequency region (1 m and above) [4]. This technique exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei when placed in a strong magnetic field. NMR measures the absorption of radio frequency radiation that matches the energy difference between nuclear spin states, providing detailed information about molecular structure, dynamics, and chemical environment [4]. The Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank provides quantitative data derived from NMR spectroscopic investigations of biological macromolecules, while databases like NMRShiftDB offer web-based resources for organic structures and their NMR spectra, including spectrum prediction capabilities [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

UV-VIS/NIR Spectroscopy Protocol for Liquid Samples

UV-VIS/NIR analysis of liquid samples follows a standardized methodology for determining analyte concentrations or monitoring chemical conversions in solution [15]. The experimental workflow begins with sample preparation, where the analyte is dissolved in an appropriate solvent that does not significantly absorb in the spectral region of interest (e.g., water for water-soluble compounds or ethanol for organic-soluble compounds) [14]. The solution is then dispensed into a clean cuvette with a known path length, typically 1 cm.

The cuvette is placed in the spectrophotometer sample compartment in the path between the optical light source and detector [15]. The instrument scans across the desired wavelength range (typically 175-3300 nm), measuring the absorption of light by the sample [15]. For quantitative analysis, measurements are taken at wavelengths where the analyte exhibits maximum absorption, and concentrations are determined using the Beer-Lambert law with previously established calibration curves [14] [15].

Critical experimental parameters that must be controlled include spectral bandwidth (which affects resolution and linearity of response), wavelength accuracy (measurements should be taken near absorbance peaks to minimize errors), and stray light (which can cause significant measurement errors, especially at high absorbances) [14]. For pharmaceutical applications, regulatory requirements from pharmacopoeias such as the USP and Ph. Eur. demand strict instrument validation for factors including stray light and wavelength accuracy [14].

Diagram 1: UV-VIS Spectroscopy Workflow for Liquid Samples

Atomic Absorption Spectrometry Protocol

Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) is a widely used technique for elemental analysis, particularly for metallic elements in solution [10]. The methodology begins with sample preparation, which may involve acid digestion or extraction to dissolve the analyte into solution. The solution is then aspirated into an atomizer, typically a flame (acetylene-air or acetylene-nitrous oxide) or electrothermal atomizer, which vaporizes the sample and breaks molecular bonds to produce free ground-state atoms [10].

A hollow cathode lamp emitting light characteristic of the element being determined passes this light through the atomized sample. Ground-state atoms of the analyte absorb light at specific wavelengths, reducing its intensity [10]. The monochromator selects the appropriate wavelength and isolates it from other spectral lines, while the detector measures the attenuated light intensity [10].

The quantity of radiation absorbed is proportional to the concentration of atoms in the flame and, consequently, to the total concentration of that element in the sample [10]. Quantitative analysis typically employs a calibration curve method using standards of known concentration. The technique is exceptionally sensitive for many metallic elements, with detection limits often in the parts-per-million range or lower [10].

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy Protocol

FTIR spectroscopy provides molecular fingerprinting through vibrational transitions [16]. Sample preparation varies by physical state: solid samples may be ground with potassium bromide (KBr) and pressed into pellets, liquid samples can be analyzed as thin films between salt plates, and gaseous samples require specialized gas cells with extended path lengths.

The experimental protocol involves collecting a background spectrum without the sample to account for atmospheric absorption (primarily CO₂ and H₂O). The sample is then placed in the instrument beam path, and an interferogram is collected using a Michelson interferometer with a moving mirror [16]. The Fourier transformation of this interferogram converts the data from the time domain to the frequency domain, producing the infrared absorption spectrum [16].

Modern FTIR instruments like the Bruker-EQUINOX55 typically operate with a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, with higher resolution available for specialized applications [16]. Spectral interpretation involves identifying characteristic functional group frequencies and comparing against reference databases such as the SDBS (Integrated Spectral Database System) which includes FT-IR spectra for organic compounds [17] [13].

Table 2: Essential Spectral Databases for Analytical Spectroscopy

| Database/Resource | Scope and Coverage | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| SDBS [17] [13] | Organic compounds; 6 spectral types including MS, NMR, IR, Raman | Integrated system; search by name, formula, CAS RN | National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science, Japan |

| NIST Chemistry WebBook [17] [13] | Chemical and physical property data; IR, mass, UV/Vis spectra | Evaluated data; search by multiple parameters | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| SpectraBase [13] | Hundreds of thousands of IR, NMR, Raman, UV, MS spectra | Original BioRad-Sadtler data; spectrum comparison | Wiley (free account limited to 10 searches/month) |

| Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank [13] | NMR spectroscopic data for biological macromolecules | Quantitative data for proteins, nucleic acids | University of Wisconsin |

| RRUFF [17] [13] | Raman and IR spectra of well-characterized minerals | Includes crystal data and chemistry | University of Arizona |

| NIST Atomic Spectra Database [13] | Radiative transitions and energy levels in atoms and ions | Data from 20 pm to 60 m wavelengths | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| HITRAN [13] | High-resolution transmission molecular absorption database | Atmospheric gas spectroscopy; fundamental parameters | Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Spectroscopic-Grade Solvents [14] | Sample preparation for UV-Vis and IR spectroscopy; minimal UV absorption | Water, ethanol, hexane, acetonitrile with low UV cutoffs |

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) [16] | Matrix for solid sample preparation in FTIR; transparent in IR region | FTIR grade; for pellet preparation with solid samples |

| Hollow Cathode Lamps [10] | Light source for atomic absorption spectrometry; element-specific | Single-element or multi-element configurations |

| Deuterated Solvents [13] | Solvent for NMR spectroscopy; minimal interference with sample signals | D₂O, CDCl₃, DMSO-d₆ with specified isotopic purity |

| Reference Standards [10] | Calibration and quantitative analysis; known purity compounds | Certified reference materials with documented purity |

| Cuvettes [15] | Sample containers for liquid spectroscopy; defined path length | Quartz (UV-Vis), glass (Vis), NaCl/KBr (IR); various path lengths |

| Integrating Spheres [15] | Accessory for diffuse reflectance and transmittance measurements | For solid sample analysis; internal reflective coating |

Applications in Drug Development and Pharmaceutical Research

Spectroscopic techniques play indispensable roles throughout the drug development pipeline, from discovery through quality control. UV-Vis spectroscopy provides a rapid, inexpensive method for quantifying analyte concentrations in solution, monitoring reaction kinetics, and determining chemical conversions [15]. Its simplicity and speed make it particularly valuable for high-throughput screening during early drug discovery phases [15].

Infrared and Raman spectroscopy contribute significantly to polymorph screening and characterization, a critical aspect of pharmaceutical development as different crystal forms can dramatically affect drug bioavailability and stability [16]. These techniques identify functional groups, monitor solid-state transformations, and characterize API-excipient interactions [16].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy serves as a powerful tool for structural elucidation of novel compounds, reaction monitoring, and impurity profiling [4] [13]. Advanced NMR techniques provide information about molecular dynamics, conformation, and intermolecular interactions in solution [13].

Mass spectrometry, while strictly speaking a form of spectrometry rather than spectroscopy, is often grouped with spectroscopic techniques and provides essential capabilities for determining molecular weight, structural characterization, and metabolite identification in drug development [4] [13]. Databases such as the Metabolomics Workbench facilitate metabolite identification through tandem mass spectrometry data [13].

Regulatory compliance in pharmaceutical spectroscopy demands careful method validation and instrument qualification. Pharmacopoeial standards (USP, Ph. Eur.) specify requirements for spectrophotometer performance including wavelength accuracy, stray light limits, and resolution [14]. For medical device characterization, techniques like UV/VIS/NIR support chemical safety assessment according to ISO 10993-18 standards [15].

Diagram 2: Spectroscopy in Drug Development Pipeline

Spectroscopic analysis represents a cornerstone of modern analytical science, providing unparalleled insights into molecular structure and composition across the entire electromagnetic spectrum. From high-energy gamma rays probing nuclear structure to radio waves revealing molecular dynamics through NMR, each spectral region offers unique analytical capabilities that researchers can harness for specific applications.

The continuing evolution of spectroscopic techniques, coupled with expanding spectral databases and improved instrumentation, ensures that these methods will remain essential tools for scientific advancement. In pharmaceutical research and drug development specifically, spectroscopy provides critical support at every stage, from initial discovery through final quality control, enabling researchers to understand molecular interactions, optimize formulations, and ensure product safety and efficacy.

As technology advances, spectroscopic techniques continue to evolve toward higher sensitivity, resolution, and automation, opening new possibilities for analytical characterization across scientific disciplines. The integration of spectroscopic data with computational analysis and machine learning approaches promises to further enhance the power and application of these fundamental analytical tools in addressing complex research challenges.

Spectroscopic analysis is a fundamental scientific technique that investigates the interaction between electromagnetic radiation and matter to determine the composition, structure, and properties of substances [18] [7]. This methodology forms the cornerstone of analytical chemistry, enabling researchers to perform both qualitative and quantitative measurements across diverse sample types, from simple elements to complex polymers and biomolecules [7]. The technique's nondestructive character and ability to detect substances at concentrations as low as parts per billion make it indispensable for research and industrial applications, including pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and medical diagnostics [7] [19].

At its core, spectroscopy involves measuring the intensity of light as a function of its wavelength, frequency, or energy after interaction with a sample [18]. The information contained in these measurements provides detailed insights into atomic and molecular behavior, allowing scientists to identify specific elements or compounds, determine their concentrations, and elucidate structural characteristics [7]. The electromagnetic spectrum utilized in these analyses spans multiple regions, from high-energy gamma rays to low-energy radio waves, with each region providing unique information about the sample being studied [7] [20].

Foundational Principles of Light-Matter Interactions

The theoretical framework for spectroscopy rests on the principles of electromagnetic radiation, characterized by its wavelength (λ) and frequency (ν), which relate through the speed of light (c) in the equation c = νλ [21]. When electromagnetic radiation encounters matter, it can undergo several fundamental interaction processes that form the basis for all spectroscopic techniques [22] [21].

The primary interactions include absorption, where matter takes in electromagnetic radiation; emission, involving the release of electromagnetic radiation by excited matter; and scattering, which redirects incident radiation in multiple directions [21]. These processes originate from energy exchanges between photons and atoms or molecules, resulting in electronic transitions, vibrational excitations, or rotational changes [22]. The specific wavelengths at which these interactions occur create characteristic spectral patterns that serve as molecular "fingerprints" for material identification [22].

Quantitative descriptions of these interactions employ well-established physical laws and parameters. The Beer-Lambert law governs absorption phenomena, relating absorbance to sample concentration and path length [18] [22]. Cross-section quantifies the probability of light-matter interactions, while quantum yield measures the efficiency of photochemical processes [22]. Selection rules, derived from quantum mechanical principles, determine allowed spectroscopic transitions based on changes in quantum numbers and symmetry considerations [22].

Absorption Spectroscopy

Theoretical Framework and Quantitative Analysis

Absorption spectroscopy measures the attenuation of light as it passes through a sample, with atoms or molecules absorbing photons to transition to higher energy states [18] [22]. The analytical utility of this technique stems from the relationship between light absorption and sample properties, quantitatively described by the Beer-Lambert law: A = ε·c·l, where A represents absorbance (unitless), ε is the molar absorptivity coefficient (L·mol⁻¹·cm⁻¹), c denotes concentration (mol/L), and l is the path length (cm) [18] [22] [21]. This fundamental equation enables quantitative analysis by establishing the direct proportionality between absorbance and the concentration of absorbing species in a sample [18].

Absorbance itself is defined as the negative logarithm of transmittance (A = -log₁₀T = -log₁₀(I/I₀)), where I represents transmitted intensity and I₀ incident intensity [22]. For multiple absorbing species in a sample, absorbance values are additive, expanding the law's application to complex mixtures [22]. The technique assumes monochromatic light and no interactions between absorbing species, with deviations from these assumptions potentially requiring more sophisticated calibration approaches [22].

Experimental Methodology for Absorption Measurements

Instrumentation and Setup: Absorption spectroscopy instruments typically consist of a broad-spectrum radiation source, a sample holder, and a detector [7] [21]. For ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, which covers wavelengths from 190-780 nm, common light sources include deuterium lamps (UV region) and tungsten-halogen lamps (visible region) [20]. The light passes through a monochromator or wavelength selector, typically containing a diffraction grating that disperses light into its component wavelengths, allowing selective transmission of specific wavelengths to the sample [19].

Sample Preparation and Measurement: Liquid samples are contained in cuvettes with precise path lengths, with material selection (e.g., quartz for UV, glass or plastic for visible light) critical for minimizing interference [19]. Solid samples may be prepared as thin films or pressed pellets, while gaseous samples require specialized cells with extended path lengths to enhance sensitivity [7]. The sample is placed between the radiation source and detector in transmission mode, and the instrument measures the intensity of light before (I₀) and after (I) passing through the sample to calculate absorbance [19].

Data Collection and Analysis: The spectrophotometer scans across a predetermined wavelength range, measuring absorbance at discrete intervals [19]. For quantitative analysis, a calibration curve is constructed by measuring absorbance values of standard solutions with known concentrations [7]. The resulting plot of absorbance versus concentration should yield a linear relationship, with the slope providing the molar absorptivity (ε) for the specific analyte [18]. Unknown sample concentrations are then determined by interpolating their absorbance measurements onto this calibration curve [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Absorption Spectroscopy

Table: Essential Materials for Absorption Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cuvettes | Transparent containers for liquid samples | Material (quartz, glass, plastic) must be compatible with wavelength range [19] |

| Standard Reference Materials | Calibration and quantitative analysis | Certified concentrations for accurate calibration curves [7] |

| Solvents | Sample dissolution and dilution | High purity, transparent in spectral region of interest [7] |

| Buffer Solutions | pH control for biological samples | Maintain biomolecular structure and activity [7] |

Emission Spectroscopy

Theoretical Principles and Energy Transitions

Emission spectroscopy analyzes light emitted by atoms or molecules when they transition from excited states to lower energy states [18] [7]. The process begins with excitation, where an external energy source (heat, electrical field, or laser) promotes electrons to higher energy orbitals [18]. As these excited electrons return to ground states or lower energy levels, they release excess energy as photons of specific wavelengths characteristic of the elements or compounds involved [18]. The emitted radiation may fall within visible, ultraviolet, or infrared regions, depending on the energy differences between electronic states [18].

Two specialized emission processes include fluorescence and phosphorescence, both involving light absorption followed by re-emission [7]. Fluorescence occurs when emission happens almost instantaneously after absorption (nanosecond timescale), while phosphorescence involves a significant time delay due to forbidden transitions between electronic states of different multiplicities [7]. The efficiency of emission processes is quantified by quantum yield (Φ), defined as the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed [22].

Experimental Protocol for Emission Measurements

Instrumentation Configuration: Emission spectroscopy systems require an excitation source, sample compartment, wavelength separation components, and a detection system [18] [7]. Common excitation sources include flames, electrical discharges (for atomic emission), and lasers (for molecular fluorescence) [18]. The detection path is typically positioned at 90° to the excitation beam to minimize interference from the excitation source, particularly in fluorescence measurements [7].

Sample Preparation and Excitation: Samples are prepared appropriately for the excitation method—solutions for flame emission, solid samples for arc/spark excitation, or gaseous forms for plasma techniques [18]. The excitation energy must be carefully controlled to avoid sample decomposition while achieving sufficient emission intensity [18]. In atomic emission spectroscopy, samples are often vaporized and atomized in high-temperature sources like inductively coupled plasma (ICP) to produce free atoms in excited states [19].

Spectral Acquisition and Analysis: The emitted radiation is dispersed using a monochromator or polychromator with diffraction gratings to separate wavelengths [19]. Detectors, such as photomultiplier tubes or CCD arrays, capture the intensity at specific wavelengths [19]. The resulting emission spectrum displays intensity versus wavelength, with peak positions identifying specific elements or molecules and peak intensities correlating with concentration [18]. For quantitative analysis, calibration curves are constructed using standard reference materials [7].

Research Reagent Solutions for Emission Spectroscopy

Table: Essential Materials for Emission Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Excitation Sources | Sample energy excitation | Lasers, plasma torches, or flame systems depending on application [18] |

| Reference Standards | Spectral calibration and quantification | Certified materials with known emission characteristics [7] |

| Sample Introduction Systems | Controlled delivery to excitation source | Nebulizers for liquid samples, laser ablation for solids [19] |

| Quartz Windows/Containers | UV-transparent sample containment | Essential for UV emission measurements [19] |

Scattering Spectroscopy

Theoretical Basis of Scattering Phenomena

Scattering spectroscopy measures changes in the direction, frequency, or polarization of radiation after interaction with matter [18]. Unlike absorption or emission processes, scattering involves the redirection of incident light by particles, molecules, or atoms within a sample [18]. The analytical utility of scattering techniques lies in their ability to provide information about sample properties such as particle size, molecular structure, and composition through analysis of the scattered light [18].

Two primary categories of scattering exist: elastic scattering, where the scattered radiation maintains the same energy (wavelength) as the incident radiation, and inelastic scattering, where energy exchange occurs between photons and molecules [22]. Rayleigh scattering represents the dominant elastic process, occurring when particles are much smaller than the excitation wavelength and resulting in scattered light at the same frequency [18]. Raman spectroscopy, the most widely used inelastic scattering technique, involves small frequency shifts (Raman shifts) corresponding to molecular vibrational energies that provide structural information complementary to infrared spectroscopy [20].

Experimental Approach for Scattering Measurements

Instrument Configuration for Raman Spectroscopy: Modern Raman systems consist of a monochromatic laser source (typically in visible or near-infrared regions), sample illumination optics, collection optics, a wavelength analyzer, and a sensitive detector [20] [19]. The laser wavelength is selected based on sample properties to avoid fluorescence interference while maintaining acceptable scattering efficiency [20]. The collection optics gather scattered light at 90° or 180° (backscattering) geometry, with notch or edge filters removing the intense elastically scattered Rayleigh component before spectral dispersion [19].

Sample Preparation and Presentation: Raman spectroscopy requires minimal sample preparation, with solids, liquids, and gases analyzed directly without special containment [20]. Glass containers are typically suitable since silica exhibits weak Raman scattering, and water produces a relatively weak Raman signal, enabling analysis of aqueous solutions [20]. For surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS), samples are deposited on nanostructured metal surfaces (gold or silver) to enhance signal intensity by several orders of magnitude [19].

Spectral Acquisition and Processing: The collected scattered radiation is dispersed using a high-resolution monochromator with a diffraction grating and detected with CCD arrays optimized for low-light detection [19]. Multiple scans are often accumulated to improve signal-to-noise ratios for weak signals [19]. The resulting Raman spectrum plots intensity versus Raman shift (cm⁻¹), with peak positions indicating specific molecular vibrations and bond types [20]. Spectral interpretation identifies functional groups and molecular structures through comparison with reference databases [20].

Research Reagent Solutions for Scattering Spectroscopy

Table: Essential Materials for Scattering Spectroscopy

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Laser Sources | Monochromatic excitation | Various wavelengths (UV, Vis, NIR) to avoid fluorescence [20] |

| SERS Substrates | Signal enhancement | Nanostructured gold or silver surfaces [19] |

| Reference Compounds | Instrument calibration | Materials with known Raman shifts (e.g., silicon) [20] |

| Microscope Objectives | Spatial resolution in micro-Raman | Focus excitation and collect scattered light [19] |

Comparative Analysis of Spectroscopic Techniques

Technical Specifications and Application Fit

Table: Comparative Analysis of Absorption, Emission, and Scattering Techniques

| Parameter | Absorption Spectroscopy | Emission Spectroscopy | Scattering Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Process | Radiation absorption with electron transitions [22] | Radiation emission from excited states [18] | Radiation redirection by sample [18] |

| Quantitative Basis | Beer-Lambert Law (A = ε·c·l) [18] | Intensity proportional to excited state population [7] | Intensity related to polarizability changes [20] |

| Detection Limits | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁹ M (UV-Vis) [7] | ~10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹² M (fluorescence) [19] | Variable; SERS to single molecule [19] |

| Information Obtained | Concentration, electronic structure [7] | Element identity, energy states [18] | Molecular vibrations, structure [20] |

| Sample Compatibility | Solutions, gases, solids [7] | Primarily solutions, vapors [18] | Solids, liquids, gases; minimal preparation [20] |

| Key Applications | Concentration measurement, reaction monitoring [21] | Elemental analysis, trace metal detection [18] | Molecular identification, surface analysis [18] |

Relationship Visualization

Diagram 1: Fundamental spectroscopic techniques and their primary applications.

Complementary Information for Material Characterization

The three fundamental spectroscopic interaction types provide complementary information that, when combined, offer comprehensive material characterization [20]. Absorption techniques, particularly UV-Vis and infrared spectroscopy, excel at identifying functional groups and quantifying concentrations through well-established relationships like the Beer-Lambert law [18] [22]. Emission methods provide exceptional sensitivity for trace element detection and are invaluable for analyzing energy states and electronic transitions [18] [7]. Scattering approaches, especially Raman spectroscopy, offer distinctive capabilities for studying aqueous solutions, investigating symmetric vibrational modes, and performing non-destructive analyses with minimal sample preparation [20].

This complementary relationship is particularly evident in the pairing of infrared absorption and Raman scattering spectroscopies, which both probe molecular vibrations but through different selection rules [20]. While IR absorption requires a change in dipole moment during vibration, Raman scattering depends on polarizability changes [20]. Consequently, homonuclear diatomic molecules like N₂ that are invisible to IR spectroscopy produce strong Raman signals, making the techniques powerfully complementary for complete molecular vibrational analysis [20].

Advanced Applications in Drug Development and Research

Structural Characterization and Quality Control

Spectroscopic techniques play indispensable roles throughout pharmaceutical development, from initial compound identification to final product quality assurance [7]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, while not covered in detail herein, provides comprehensive structural information about drug molecules through analysis of atomic environments [19]. Infrared absorption spectroscopy identifies functional groups and verifies compound identity through characteristic vibrational fingerprints, with attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessories enabling rapid solid and liquid analysis without extensive sample preparation [7] [21].

UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy serves as a workhorse for quantitative analysis in pharmaceutical applications, often coupled with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) systems to detect and quantify drug compounds as they elute from separation columns [20]. This combination provides both separation capability and specific detection based on ultraviolet absorption characteristics, creating a powerful analytical system for complex mixture analysis [20]. Raman scattering spectroscopy has gained prominence for its ability to analyze aqueous formulations nondestructively, identify polymorphic forms, and map drug distribution in solid dosage forms through hyperspectral imaging [20] [19].

Biomolecular Interaction Studies and Kinetic Monitoring

The high sensitivity of fluorescence emission spectroscopy makes it invaluable for studying biomolecular interactions, including protein-ligand binding, protein folding, and enzyme kinetics [19]. Intrinsic fluorophores (tryptophan, tyrosine) or extrinsic fluorescent labels provide signals that change with molecular environment, conformation, and interaction status [19]. These changes in fluorescence intensity, polarization, or energy transfer efficiency enable researchers to quantify binding constants, thermodynamic parameters, and reaction rates critical to understanding drug mechanisms [19].

Absorption spectroscopy in the UV-Vis region facilitates real-time reaction monitoring by tracking appearance or disappearance of chromophores during chemical and biological processes [21]. The technique's rapid data acquisition capabilities allow researchers to determine kinetic parameters and elucidate reaction mechanisms [21]. Similarly, IR absorption spectroscopy monitors reaction progress through changes in functional group vibrations, providing insights into reaction pathways and intermediate formation [21]. These applications demonstrate how fundamental light-matter interactions translate into practical tools for advancing pharmaceutical research and development.

Experimental Workflow for Drug Analysis

Diagram 2: Spectroscopic techniques applied throughout the drug development pipeline.

Spectroscopic analysis, a cornerstone of modern analytical science, is the study of the interaction between matter and electromagnetic radiation [3]. This field measures and interprets electromagnetic spectra to investigate the composition, physical structure, and electronic structure of matter at atomic, molecular, and macroscopic scales [3]. The journey of spectroscopy from a fundamental observation of light to a sophisticated tool underpinning quantum theory and revolutionizing industries like pharmaceutical development represents a remarkable synthesis of empirical observation and theoretical innovation. This progression demonstrates how technological advances continuously refine our understanding of fundamental physical principles, enabling precise qualitative and quantitative measurement of substances from simple elements to complex biomolecules [7]. The non-destructive character, high-throughput capability, and applicability to a wide range of samples make spectroscopy indispensable in contemporary research and industrial quality control [23] [7].

Historical Foundations: From Light to Lines

The foundational discoveries in spectroscopy emerged through cumulative work by scientists building upon each other's observations, with Isaac Newton's prism experiments between 1666 and 1672 representing a pivotal starting point [24]. Newton used a prism to disperse white sunlight into colored components, which he named the "spectrum" [24] [3]. His work, documented in "Optics," was built upon earlier investigations by Athanasius Kircher (1646), Jan Marek Marci (1648), Robert Boyle (1664), and Francesco Maria Grimaldi (1665) [24].

In 1802, William Hyde Wollaston created the first spectrometer by improving upon Newton's model with a lens that focused the Sun's spectrum onto a screen [24]. He observed that the spectrum was missing sections of color but mistakenly attributed these lines to natural boundaries between colors [24]. This error was corrected by Joseph von Fraunhofer in 1815, who replaced Newton's prism with a diffraction grating, achieving improved spectral resolution [24]. The dark lines he observed and quantified are still known as Fraunhofer lines, earning him the distinction as the father of spectroscopy [24].

Throughout the mid-1800s, scientists including Anders Jonas Ångström, George Stokes, and William Thomson made important connections between emission spectra and absorption and emission lines [24]. The critical breakthrough came in the 1860s when Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff discovered that Fraunhofer lines correspond to emission spectral lines observed in laboratory light sources, establishing the fundamental connection between chemical elements and their unique spectral patterns [24] [3].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Early Spectroscopy

| Year(s) | Scientist | Contribution | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1666-1672 | Isaac Newton | Prism experiments dispersing white light | Established "spectrum" concept and foundational optics |

| 1802 | William Hyde Wollaston | Built first spectrometer with focusing lens | Noted missing color sections in solar spectrum |

| 1815 | Joseph von Fraunhofer | Used diffraction grating for dispersion | Discovered and quantified dark absorption lines (Fraunhofer lines) |

| 1860s | Robert Bunsen & Gustav Kirchhoff | Systematic spectral examinations | Established link between elements and unique spectral patterns |

The following workflow diagrams the key historical developments in early spectroscopy:

The Quantum Revolution: Spectroscopy as a Foundation

The development of quantum mechanics in the early 20th century is inextricably linked with spectroscopic observations that challenged classical physics. Spectroscopy provided the critical experimental evidence that necessitated a radical rethinking of atomic structure and energy transitions [3]. The discrete spectral lines observed by Fraunhofer, Bunsen, and Kirchhoff found their explanation in quantum theory, which posits that atoms and molecules exist in discrete energy states and transitions between these states result in the absorption or emission of specific frequencies of electromagnetic radiation [3].

Spectroscopic studies were central to developing quantum mechanics because the first useful atomic models described the hydrogen spectrum [3]. Niels Bohr's atomic model, Erwin Schrödinger's wave equation, and matrix mechanics all successfully predicted the discrete hydrogen spectrum, providing crucial validation for quantum theory [3]. Further, Max Planck's explanation of blackbody radiation involved comparing light wavelength using a photometer to black body temperature, establishing the quantum nature of energy [3]. The Lamb shift observed in the hydrogen spectrum, a subtle deviation from theoretical predictions, played a pivotal role in developing quantum electrodynamics [3].

Table 2: Spectroscopic Contributions to Quantum Mechanical Concepts

| Quantum Concept | Spectroscopic Evidence | Scientific Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Quantized energy levels | Discrete atomic emission/absorption lines | Invalidated classical continuous energy prediction |

| Wave-particle duality | Atomic spectral line patterns | Supported de Broglie hypothesis of matter waves |

| Quantum jumps | Hydrogen spectrum discrete transitions | Validated Bohr model of electron transitions |

| Quantum electrodynamics | Lamb shift in hydrogen spectrum | Refined understanding of electron-photon interactions |

The theoretical framework underlying all spectroscopic techniques is that each element has a unique light spectrum described by the frequencies of light it emits or absorbs, consistently appearing in the same part of the electromagnetic spectrum when diffracted [3]. This atomic spectral signature enables the identification and quantification of elements across various phases and conditions [3]. The National Institute of Standards and Technology maintains a public Atomic Spectra Database that is continually updated with precise measurements, facilitating modern spectroscopic analysis [3] [13].

Methodological Framework: Techniques and Applications

Classification of Spectroscopic Methods

Spectroscopy encompasses numerous techniques classified by the type of radiative energy involved, the nature of the energy-matter interaction, and the material being studied [3]. The primary classification based on interaction type includes:

- Absorption spectroscopy: Measures radiation absorbed by the material, decreasing transmitted energy [7] [3]

- Emission spectroscopy: Measures radiative energy released by the material, either spontaneously or after energy stimulation [7] [3]

- Vibrational spectroscopy: Studies molecular vibrations through infrared or Raman techniques [3]

- Electron spin resonance: Utilizes microwave radiation to study systems with unpaired electrons [7]

- Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR): Uses radio waves to examine atomic nuclei in magnetic fields [7] [25]

The following workflow illustrates the fundamental spectroscopic processes based on energy-matter interactions:

Modern Technical Implementations

Contemporary spectroscopy utilizes various regions of the electromagnetic spectrum, each providing unique information about atomic and molecular structures:

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy: Exploits magnetic properties of atomic nuclei (e.g., hydrogen-1, carbon-13) that absorb and re-emit electromagnetic radiation at characteristic frequencies when placed in a strong magnetic field [25]. Parameters like chemical shifts, coupling constants, and signal intensities reveal electronic environments, atomic connectivity, and spatial arrangement [25].

Infrared (IR) spectroscopy: Analyzes molecular vibrations in the infrared region, particularly useful for identifying functional groups and bonding patterns [26]. Characteristic signals include O-H bonds (2400-3400 cm⁻¹), carbonyl C=O bonds (around 1700 cm⁻¹), and unsaturated hydrocarbons (slightly above 3000 cm⁻¹ for sp² hybridized carbon atoms) [26].

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy: Studies electronic transitions in molecules using ultraviolet and visible light, commonly applied to concentration measurements [7] [2].

Mass spectrometry: While not strictly spectroscopic, often combined with spectroscopic techniques to provide comprehensive molecular characterization [13].

Table 3: Spectroscopic Techniques Across the Electromagnetic Spectrum

| Spectral Region | Wavelength Range | Primary Information | Common Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| γ-ray | < 0.01 nm | Nuclear structure | Mössbauer spectroscopy |

| X-ray | 0.01-10 nm | Inner shell electrons | X-ray spectroscopy, X-ray fluorescence |

| Ultraviolet-Visible | 10-400 nm (UV), 400-750 nm (Vis) | Electronic transitions | UV-Vis spectroscopy, fluorescence |

| Infrared | 750 nm-1 mm | Molecular vibrations | FTIR, NIR, Raman spectroscopy |

| Microwave | 1 mm-1 m | Molecular rotations | Rotational spectroscopy, electron spin resonance |

| Radio wave | > 1 m | Nuclear spin states | NMR spectroscopy |

Contemporary Applications: Spectroscopy in Drug Discovery and Development

NMR in Pharmaceutical Research

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy has revolutionized drug discovery, particularly through its ability to target biomolecules and observe chemical compounds directly [25]. Recent advancements include high-field NMR spectrometers providing unprecedented resolution and sensitivity, cryoprobes improving measurement efficiency, and advanced pulse sequences enhancing data accuracy [25]. NMR-based fragment screening has emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying small molecules that bind to target proteins, enabling optimization into potent drug candidates [25]. Paramagnetic NMR spectroscopy studies protein-ligand interactions by leveraging metal ions to enhance NMR signals of nearby nuclei, providing insights into spatial arrangements within complexes [25].

Vibrational Spectroscopy in Quality Control

Infrared spectroscopy has become indispensable in pharmaceutical quality control and herbal medicine analysis due to its rapid, non-destructive nature [27]. FT-IR coupled with chemometric techniques enables quantitative analysis of compounds in complex matrices like plant-based medicines and supplements [27]. Spectral preprocessing and variable selection significantly enhance the accuracy and precision of infrared spectroscopy methods for quantifying phytochemicals and detecting adulterants [27]. The success of these applications is evaluated through root mean square error of calibration (RMSEC), root mean square error of prediction (RMSEP), root mean square error of cross-validation (RMSECV), and determination coefficient (R²) values [27].

Advanced Spectroscopic Integration

Modern pharmaceutical research increasingly combines multiple spectroscopic techniques for comprehensive analysis. Recent developments include:

- Raman spectroscopy enhancements: Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) and tip-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (TERS) enable molecular imaging, fingerprinting, and detection of low-concentration substances [2].

- Process Analytical Technology (PAT): Integration of inline Raman spectroscopy for real-time monitoring of biopharmaceutical manufacturing processes, enabling measurement of product aggregation and fragmentation every 38 seconds [2].

- Multi-technique correlation: Combining NMR with cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography to obtain complementary structural information for therapeutic design [25].

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions in Spectroscopic Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High-field NMR spectrometers | Provides high resolution and sensitivity for biomolecular analysis | Protein-ligand interaction studies, drug candidate optimization |

| Cryoprobes | Enhances signal-to-noise ratio in NMR measurements | Structure-based drug discovery, metabolite identification |

| Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometers | Identifies chemical bonds and functional groups through infrared absorption | Herbal medicine authentication, polymer characterization |

| Diffraction gratings | Disperses light into component wavelengths for precise spectral analysis | Atomic emission spectroscopy, laser spectroscopy |

| Chemometric software | Processes complex spectral data through multivariate analysis | Quantitative spectral analysis, pattern recognition in mixtures |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies in Practice

Infrared Spectroscopic Analysis Protocol

Standard FT-IR analysis for organic compound characterization follows this workflow:

Sample Preparation: Prepare samples as solutions, vapor, powders, thin films, or pressed pellets depending on material properties and analytical requirements [27]. For solid samples, the KBr pellet method is commonly employed.

Instrument Calibration: Perform background scan and instrument calibration using standard reference materials to ensure wavelength accuracy and intensity linearity.

Spectral Acquisition: Acquire spectra typically in the range of 4000-400 cm⁻¹ with 4 cm⁻¹ resolution, accumulating 64 scans to improve signal-to-noise ratio [23].

Spectral Preprocessing: Apply preprocessing techniques such as multiplicative scatter correction (MSC), standard normal variate (SNV), Savitzky-Golay derivatives, or wavelet transforms to remove scattering effects and enhance spectral features [27].

Data Analysis: For qualitative analysis, identify characteristic functional group absorptions (O-H at 2400-3400 cm⁻¹, C=O at ~1700 cm⁻¹) [26]. For quantitative analysis, employ chemometric methods like partial least squares (PLS) regression with variable selection techniques (CARS, iPLS-GA) to build calibration models [27].

NMR Spectroscopy in Drug Discovery Protocol

The application of NMR in structure-based drug discovery involves:

Sample Preparation: Prepare protein target (0.1-1 mM) in appropriate buffer with 5-10% D₂O for lock signal. For ligand observations, typically use 0.01-1 mM compound concentration.

Ligand Screening: Employ NMR-based fragment screening using libraries of low-molecular-weight compounds (200-300 Da). Monitor chemical shift perturbations, line broadening, or transferred NOE to identify binders [25].

Binding Affinity Determination: Measure chemical shift perturbations as a function of ligand concentration to determine dissociation constants (K_D) using titration experiments.

Structure Determination: For protein-ligand complexes, collect multidimensional NMR spectra (NOESY, HSQC, TROSY) to determine binding mode and structural constraints [25].

Lead Optimization: Use structural information to guide medicinal chemistry efforts, optimizing fragments into potent drug candidates through iterative synthesis and NMR validation [25].

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for structural determination using combined spectroscopy and chemical tests:

Spectroscopic analysis continues to evolve, driven by technological innovations in optics, electronics, and computational methods [23] [7]. Ongoing miniaturization of spectrometers enhances on-site capabilities for environmental monitoring, while airborne drones equipped with spectrometers enable remote monitoring of large land, sea, and air areas [23]. In pharmaceutical research, the integration of spectroscopy with machine learning and artificial intelligence promises to further accelerate drug discovery and quality control processes [2]. The historical journey from Newton's prism to modern quantum-mechanical applications demonstrates how fundamental scientific inquiries mature into essential analytical tools that continue to expand their capabilities and applications across diverse scientific disciplines.

Spectroscopic analysis is a cornerstone of modern scientific research, enabling the detailed examination of materials based on their interaction with light. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, these techniques provide indispensable tools for determining chemical composition, identifying molecular structures, and quantifying substances with exceptional precision. The fundamental principle underlying all spectroscopic methods is that when matter interacts with electromagnetic radiation, it absorbs, emits, or scatters this radiation in ways that are characteristic of its specific chemical properties [4]. This interaction produces a unique "spectral fingerprint" that can be measured and interpreted to reveal critical information about the sample's composition and structure [4].

The widespread adoption of spectroscopic techniques across pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, and materials research stems from their ability to deliver rapid, non-destructive analysis with high sensitivity and specificity. From ensuring drug purity and stability to characterizing novel compounds and monitoring industrial processes, spectrometers and spectrophotometers have become essential instruments in the researcher's toolkit [2]. This technical guide examines the fundamental operating principles, components, and applications of these critical analytical instruments, with a specific focus on their implementation in research and development environments.

Fundamental Principles of Spectroscopy

The Electromagnetic Spectrum and Molecular Interactions

Spectroscopy utilizes various regions of the electromagnetic spectrum to probe different aspects of molecular structure. The specific type of information obtained depends on the energy of the radiation used, which corresponds to different molecular processes [20]. Ultraviolet (UV) spectroscopy (190-360 nm) primarily examines electronic transitions involving non-bonding electrons and those in double and triple bonds, making it particularly useful for detecting chromophores such as ketones, aldehydes, and aromatic compounds [20] [28]. Visible spectroscopy (360-780 nm) also probes electronic transitions, specifically those that produce colored compounds, with applications in color measurement and quantitative analysis of transition metal complexes and highly conjugated organic molecules [20]. Infrared (IR) spectroscopy (700 nm-1 mm) investigates molecular vibrations, including stretching and bending motions of chemical bonds, providing information about functional groups present in organic compounds, polymers, and pharmaceuticals [20] [4].