Strategic HPLC Column Selection for Pharmaceutical Compounds: A 2025 Guide to Method Development, Optimization, and Troubleshooting

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on selecting and optimizing HPLC columns for pharmaceutical analysis.

Strategic HPLC Column Selection for Pharmaceutical Compounds: A 2025 Guide to Method Development, Optimization, and Troubleshooting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals on selecting and optimizing HPLC columns for pharmaceutical analysis. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details the latest innovations in column technology, including inert hardware and novel stationary phases for complex samples like oligonucleotides and biologics. The content offers actionable methodologies for method development, practical troubleshooting strategies for common performance issues, and frameworks for method validation and comparative analysis to ensure regulatory compliance and robust quality control.

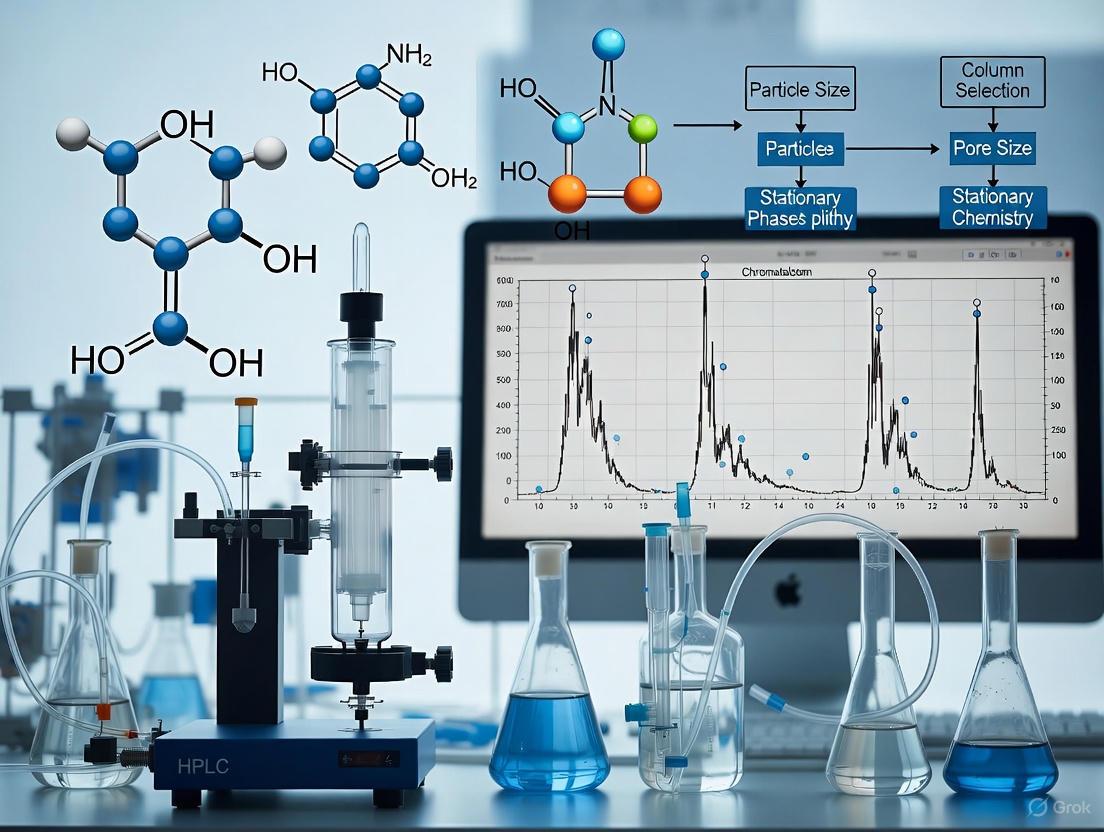

Understanding HPLC Column Fundamentals: Stationary Phases, Particle Technology, and Modern Innovations

In the field of pharmaceutical analysis, the selection of an appropriate High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) column is a critical determinant of research success. Effective separation of drug compounds, their metabolites, and potential impurities directly impacts the accuracy and reliability of analytical results. This application note details the three fundamental principles governing HPLC separation—retention, selectivity, and efficiency—within the specific context of pharmaceutical compound separation research. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this document provides both theoretical frameworks and practical experimental protocols to guide robust HPLC method development and column selection.

The core separation power of HPLC is mathematically described by the master resolution equation [1]: Rs = (1/4) * (α - 1) * √N * (k₂/(1 + k₂)) Where:

- Rs = Resolution

- α (Alpha) = Selectivity

- N = Efficiency (Theoretical Plates)

- k = Retention Factor

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships between the fundamental parameters, the factors that influence them, and the ultimate goal of chromatographic resolution.

Core Principles and Quantitative Relationships

Retention (k)

Retention, quantified by the retention factor (k), describes the relative speed at which an analyte moves through the chromatographic system. It is calculated as k = (tᵣ - t₀)/t₀, where tᵣ is the analyte retention time and t₀ is the column dead time [2]. Adequate retention is essential to separate analytes from the solvent front and ensure accurate integration. For pharmaceutical applications, a retention factor between 2 and 10 is generally considered optimal [3]. It is crucial to note that while the retention factor is nominally independent of variables like flow rate and column length, significant operating pressure can influence the retention of certain analytes, particularly larger molecules or ionizable compounds [4].

Selectivity (α)

Selectivity (α) is the capability of the chromatographic system to separate two analytes based on their differing chemical interactions with the stationary and mobile phases. It is defined as α = k₂/k₁, where k₂ and k₁ are the retention factors of the two later- and earlier-eluting analytes, respectively [2]. A selectivity value of 1 indicates co-elution. Altering selectivity is the most powerful approach to improving resolution [1] [5]. For structural isomers or compounds with identical mass, achieving chromatographic selectivity is often the only reliable way to differentiate them, even when using mass spectrometric detection [1] [2].

Efficiency (N)

Column efficiency, expressed as the number of theoretical plates (N), is a measure of peak broadening. A higher number of theoretical plates yields sharper, narrower peaks, which enhances resolution and detection sensitivity [6]. Efficiency is calculated from retention time and peak width, with several accepted calculation methods [7]:

- United States Pharmacopeia (USP) / Tangent Method: N = 16 (tᵣ / Wb)²

- Half-Peak Height Method (used by EP, BP, DAB): N = 5.54 (tᵣ / W₀.₅)²

- Area Height Method: N = 2π (tᵣ H / A)² where Wb is the peak width at baseline, W₀.₅ is the width at half height, H is the peak height, and A is the peak area [7]. It is critical to maintain consistent calculation methods when comparing columns, as the values can differ significantly for tailing peaks [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of k, α, and N on Resolution

| Parameter | Definition | Mathematical Impact on Resolution (Rs) | Optimal Range for Pharmaceuticals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Retention Factor (k) | Measures relative analyte speed; k = (tᵣ - t₀)/t₀ [2] | Affects term k/(1+k); diminishing returns beyond k > 10 [1] | 2 - 10 [3] |

| Selectivity (α) | Ratio of retention factors for two analytes; α = k₂/k₁ [2] | Linear effect via (α - 1); most powerful factor for improving Rs [5] | >1.05 (Values further from 1.0 indicate better separation) |

| Efficiency (N) | Number of theoretical plates; measure of peak sharpness [6] | Square root effect (√N); doubling N only increases Rs by ~1.4x [5] | Maximize via small particles, optimized flow, and column packing |

Table 2: Comparison of Theoretical Plate (N) Calculation Methods [7]

| Calculation Method | Governing Pharmacopeia | Formula | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tangent Line Method | USP | N = 16 (tᵣ / Wb)² | Official USP method. | Problematic with distorted peaks that have multiple inflection points. |

| Half Peak Height Method | EP, BP, DAB | N = 5.54 (tᵣ / W₀.₅)² | Simple; most widely used; can be done easily by hand. | For broader peaks, results in larger N values than other methods. |

| Area Height Method | - | N = 2π (tᵣ H / A)² | Accurate and reproducible even for distorted peaks. | Can yield larger N values when peak overlap is significant. |

| EMG Method | - | N = See reference [7] | Accommodates peak asymmetry. | Cannot calculate unless the peak is completely separated. |

Experimental Protocols for HPLC Method Development

This section provides a detailed workflow and specific procedures for developing and optimizing an HPLC method for pharmaceutical compounds.

Systematic Method Development Workflow

The following workflow outlines a structured approach to HPLC method development, from defining objectives to final validation.

Protocol 1: Optimization of Retention and Selectivity via Mobile Phase and Stationary Phase

Objective: To achieve baseline resolution (Rs ≥ 1.5) for a mixture of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and related compounds by systematically optimizing mobile phase composition and stationary phase chemistry [3] [8].

Materials:

- HPLC system with UV or PDA detector

- Columns: A standard C18 column (e.g., 150 mm x 4.6 mm, 5 µm), a phenyl-hexyl column, and a cyano (CN) column [1] [9].

- Mobile Phase A: Water or aqueous buffer (e.g., 10-20 mM phosphate or formate)

- Mobile Phase B: Organic modifiers (Acetonitrile, Methanol, Tetrahydrofuran)

- Standard solution containing target analytes

Procedure:

- Initial Scouting: Inject the standard solution using the C18 column and a linear gradient from 5% to 95% B over 20-30 minutes. Observe the retention and separation of all components.

- Optimize Retention (k): Switch to an isocratic method. Adjust the %B based on the scouting run to bring the retention factors of all critical peaks into the optimal range of 2-10. If the last peak elutes with k > 10, increase %B; if the first peak elutes with k < 2, decrease %B.

- Optimize Selectivity (α) via Mobile Phase:

- Change Organic Modifier: If critical peak pairs are still co-eluting, switch the organic modifier. Use Figure 4 (solvent strength relationships) from the search results to estimate the required concentration for equivalent retention [3]. For example, if 50% Acetonitrile was used, try ~57% Methanol or ~35% Tetrahydrofuran.

- Adjust pH (for ionizable compounds): For acidic compounds, use a buffer at a pH ~2 units below the pKa. For basic compounds, use a buffer at a pH ~2 units above the pKa. This suppresses ionization and increases retention. Adjusting pH can dramatically alter selectivity [3].

- Optimize Selectivity (α) via Stationary Phase: If mobile phase adjustments are insufficient, change the column chemistry [1] [2].

- For aromatic compounds, try a biphenyl phase to exploit π-π interactions [1] [9].

- For polar compounds or those requiring different selectivity, try a cyano (CN) or a polar-embedded phase [1].

- For basic compounds that show tailing on silica-based columns, consider a charged surface hybrid (CSH) or polymer-based column to minimize silanol interactions [10] [2].

- Final Method Refinement: Fine-tune the gradient profile or isocratic composition based on the selected column and organic modifier to achieve the final separation.

Protocol 2: Evaluation of Column Efficiency and System Suitability

Objective: To determine the efficiency (theoretical plate count, N) of an HPLC column and assess system suitability for a specific analytical method as per pharmaceutical guidelines [7] [6].

Materials:

- Validated HPLC method (isocratic conditions preferred)

- Column under test

- Standard analyte with k > 5 (e.g., toluene or naphthalene for reversed-phase) [6]

Procedure:

- System Equilibration: Equilibrate the column with the mobile phase until a stable baseline is achieved. Ensure the system is leak-free and the column thermostat is set to the specified temperature.

- Injection and Data Acquisition: Inject the standard solution and record the chromatogram. Ensure the peak of interest is well-defined and symmetrical.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the column efficiency (N) using one of the following methods, ensuring consistency with prior tests [7].

- USP (Tangent) Method: From the chromatogram, measure the retention time (tᵣ) and the peak width at baseline (Wb) determined by drawing tangents to the inflection points of the peak. Calculate N = 16 (tᵣ / Wb)².

- Half-Peak Height Method: Measure the retention time (tᵣ) and the peak width at half its maximum height (W₀.₅). Calculate N = 5.54 (tᵣ / W₀.₅)².

- System Suitability Assessment: Compare the calculated plate count against the method's predefined acceptance criteria. A well-packed analytical column (150 mm) should typically deliver tens of thousands of plates per meter [6]. Also, check for peak asymmetry (tailing factor).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the correct materials is paramount for successful HPLC analysis in pharmaceutical research. The following table details key solutions for method development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HPLC Method Development

| Category & Item | Function / Rationale for Use | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Stationary Phases | ||

| C18 (Octadecylsilyl) | The workhorse for reversed-phase; provides hydrophobic retention for a wide range of analytes. | Good starting point for most methods. All C18 phases are not created equal; selectivity varies by manufacturer [1]. |

| Biphenyl | Provides π-π interactions in addition to hydrophobicity, offering enhanced selectivity for aromatic analytes [1] [9]. | Ideal for separating structural isomers of aromatic pharmaceuticals. |

| Phenyl-Hexyl | Offers a combination of hydrophobic and π-π interactions, providing alternative selectivity to C18 [9]. | Useful for challenging separations where C18 fails. |

| Cyano (CN) | A versatile, polar functional group that can be used in both reversed-phase and normal-phase modes, offering vastly different selectivity [1]. | Useful for more polar analytes in reversed-phase mode. |

| Organic Modifiers | ||

| Acetonitrile | Aprotic solvent; strong elution strength in reversed-phase; often produces sharp peaks and high efficiency [2]. | First-choice modifier for methods coupled with MS due to low viscosity and high volatility. |

| Methanol | Protic solvent; weaker elution strength than acetonitrile; can provide different selectivity, especially for hydrogen-bonding compounds [3] [2]. | Useful for separating compounds that co-elute with acetonitrile. Can generate higher backpressure. |

| Aqueous Buffers & Additives | ||

| Ammonium Formate/Acetate (10-20 mM) | Volatile buffers for mass spectrometry compatibility; controls pH for ionizable compounds. | Standard for LC-MS methods. |

| Phosphate Buffers (10-50 mM) | Non-volatile buffers for UV detection; excellent pH control in the 2-8 range. | Not suitable for LC-MS. Provides robust control of retention and selectivity for ionizable analytes [3]. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) (0.05-0.1%) | Ion-pairing agent and pH modifier; improves peak shape for peptides and basic compounds [3]. | Can cause signal suppression in MS. |

| Specialist Columns | ||

| Solid-Core / Fused-Core | Particles with a solid core and porous shell; provide high efficiency with lower backpressure than fully porous particles of the same size [3] [9]. | Enables fast, high-resolution separations. |

| Bio-inert / Inert Hardware | Columns with passivated (e.g., PEEK-lined) hardware to minimize interaction with metal-sensitive analytes [9]. | Essential for analyzing chelating compounds, phosphorylated drugs, or certain antibiotics to prevent adsorption and peak tailing. |

Advanced Considerations and Recent Innovations

The field of HPLC column technology continues to evolve. Recent innovations focus on providing novel selectivity, enhanced inertness, and broader operating ranges [9].

- Novel Stationary Phases: New phases like the Halo 90 Å PCS Phenyl-Hexyl (Advanced Materials Technology) are designed to offer enhanced peak shape for basic compounds and alternative selectivity. Phases such as the Aurashell Biphenyl (Horizon Chromatography) are engineered for improved retention of hydrophilic aromatics and isomer separations [9].

- Enhanced Inertness: The trend towards using inert or bio-inert hardware is strong. Columns like the Halo Inert (Advanced Materials Technology) and Restek Inert HPLC Columns feature passivated fluid paths that minimize analyte adsorption, crucially improving recovery and peak shape for metal-sensitive compounds like those found in many pharmaceutical formulations [9].

- Broad pH Stability: Columns based on hybrid silica (e.g., Halo 120 Å Elevate C18) offer exceptional stability across a wide pH range (e.g., pH 2-12), granting chromatographers a powerful tool for manipulating selectivity via pH without damaging the column [9].

The strategic selection and optimization of an HPLC column are foundational to successful pharmaceutical analysis. A deep understanding of the interdependent roles of retention, selectivity, and efficiency allows researchers to develop robust, reliable methods efficiently. As demonstrated, while all three parameters in the resolution equation are important, manipulating selectivity through changes in the stationary phase chemistry and mobile phase composition provides the most significant leverage for overcoming challenging separations, such as those involving isomeric impurities. By applying the systematic protocols and utilizing the toolkit outlined in this application note, scientists can make informed decisions in HPLC column selection and method development, ultimately accelerating drug research and ensuring data quality.

The selection of an appropriate stationary phase is a critical first step in developing robust, selective, and efficient high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) methods for pharmaceutical analysis. The chemical nature of the stationary phase directly governs the retention mechanism and selectivity for target analytes, influencing method resolution, sensitivity, and analysis time. Within drug development, applications range from the separation of small molecule APIs and excipients to the characterization of large biomolecules like oligonucleotides and proteins. This application note provides a detailed, contemporary guide for researchers and scientists selecting among five principal stationary phase chemistries—C18, C8, Phenyl, HILIC, and Ion Exchange. It synthesizes the latest 2025 innovations in column technology with practical experimental protocols to guide method development for specific pharmaceutical compound classes, ensuring optimal outcomes in research and quality control.

The evolving pharmaceutical landscape, particularly the rapid expansion of complex modalities like oligonucleotide therapeutics, continuously pushes the boundaries of chromatographic science. Recent innovations focus on enhancing column inertness to improve the recovery of metal-sensitive compounds, developing stationary phases with alternative selectivity to replace ion-pairing reagents and creating materials capable of withstanding extreme pH conditions for method flexibility. This document frames the selection of stationary phase chemistry within the broader thesis that a fundamental understanding of retention mechanisms, coupled with strategic experimental screening, is paramount for successful HPLC method development in modern drug research and development.

Stationary Phase Chemistry and Characteristics

Core Principles and Retention Mechanisms

The interaction between an analyte and the stationary phase is the foundation of chromatographic separation. In reversed-phase chromatography (RPC), which includes C18, C8, and Phenyl phases, the primary mechanism is hydrophobic interaction, where non-polar regions of the analyte associate with the hydrophobic ligands of the stationary phase. The strength of this interaction increases with the surface area and the carbon load of the phase. In contrast, Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography (HILIC) operates with a polar stationary phase and a hydrophobic mobile phase (typically acetonitrile-rich), retaining polar compounds via hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole interactions, and occasionally electrostatic forces. Ion Exchange Chromatography (IEX) separates ionic or ionizable compounds based on electrostatic attraction between the analyte and charged functional groups on the stationary phase; cationic analytes bind to negatively charged sulfonic acid groups (strong cation exchange, SCX), while anionic analytes bind to positively charged ammonium groups (strong anion exchange, SAX).

Comparative Analysis of Stationary Phases

The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison of the key physical and chemical characteristics of the five stationary phases, serving as a quick-reference guide for initial selection.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of HPLC Stationary Phases for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Stationary Phase | Retention Mechanism | Typical Pore Size (Å) | Typical Particle Sizes (µm) | pH Range | Primary Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C18 | Hydrophobic/dispersive | 90 - 140 [11] | 1.7, 1.8, 2.7, 3, 5 [11] | 1.0 - 12.0 (varies by brand) [9] [11] | General small molecules, potency assays, stability-indicating methods, lipids |

| C8 | Hydrophobic/dispersive (less than C18) | 90 - 100 [11] | 3, 5, 10 [12] [13] | 2.0 - 8.0 [11] | Moderately polar small molecules, peptides, natural products |

| Phenyl | Hydrophobic + π-π stacking, dipole-dipole | 90 - 150 [9] [11] | 1.8, 2.7, 3, 5 [9] | 2.0 - 8.0 [11] | Aromatics, isomers, oligonucleotides (ion-pair free) [14], compounds with conjugated systems |

| HILIC | Hydrogen bonding, dipole-dipole, electrostatic | 100 - 140 [11] | 1.7, 3, 5 [15] | 2.5 - 8.0 (silica-based) [11] | Polar small molecules (sugars, organic acids), nucleotides, water-soluble vitamins, metabolites |

| Ion Exchange | Electrostatic attraction | N/A | 1.9, 3, 5 [9] | Varies (polymer-based can be 1-14) [16] | Biologics (proteins, mAbs, oligonucleotides), charged APIs, impurity profiling |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for HPLC Method Development

| Item | Function/Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Acetate (Volatile Buffer) | Provides pH control and ionic strength in MS-compatible methods. | Ideal for oligonucleotide analysis with phenyl columns and HILIC methods [14]. |

| Trifluoroacetic Acid (TFA) | Ion-pairing reagent and mobile phase modifier for peptides and proteins. | Can suppress ionization in MS; use at low concentrations (0.05-0.1%). |

| Triethylamine (TEA) | Ion-pairing reagent for oligonucleotides in IP-RPLC. | Non-volatile; not MS-compatible. Phenyl phases offer an MS-compatible alternative [14] [17]. |

| Formic Acid (Volatile Acid) | Common mobile phase additive for low-pH RPLC-MS methods. | Promotes protonation of analytes; enhances ionization in positive ESI-MS. |

| Inert/Passivated Hardware Columns | Columns with metal-free flow paths or passivated surfaces. | Crucial for analyzing metal-sensitive compounds like phosphorylated species, chelating PFAS, and pesticides [9]. |

| Methanol & Acetonitrile (HPLC Grade) | Primary organic modifiers for reversed-phase and HILIC chromatography. | Methanol can enhance π-π interactions on phenyl phases [14]. Acetonitrile is preferred for HILIC and low-UV detection. |

Detailed Stationary Phase Profiles and Applications

C18 (Octadecylsilane)

C18 columns are the most widely used stationary phases in RPC due to their strong hydrophobic retention, making them the default choice for a vast range of non-polar to moderately polar small molecules. The long alkyl chain (18 carbons) provides significant hydrophobic surface area for interaction. Newer C18 phases are engineered for high pH stability (pH 2-12), allowing method development at alkaline pH to suppress the ionization of basic compounds, improving peak shape and retention [9]. While often considered a general-purpose phase, its selectivity can be fine-tuned through variations in bonding density, end-capping procedures, and base silica purity. A notable innovation is the introduction of superficially porous particle (SPP) C18 columns, which offer high efficiency and lower backpressure compared to fully porous particles, making them ideal for high-throughput UHPLC-MS/MS applications in bioanalytical testing and therapeutic drug monitoring [9] [11].

C8 (Octylsilane)

C8 columns, with a shorter carbon chain, provide less hydrophobic retention compared to C18. This often results in shorter analysis times and can be advantageous for separating moderately hydrophobic compounds that are overly retained on a C18 phase. The distinction is not merely about retention time; factors such as bonding chemistry and packing quality can have a greater effect on selectivity and efficiency than the chain length itself [18]. In practice, a high-load C8 phase can sometimes generate more retention than a low-load C18 phase. C8 columns are particularly well-suited for the separation of peptides and moderately polar pharmaceutical compounds, and they can exhibit improved peak shapes for basic analytes due to reduced secondary interactions with residual silanols, although this is highly dependent on the base silica and end-capping used [18]. The market for C8 columns is growing steadily, valued at $299 million in 2025, driven by their versatility in pharmaceutical, biotechnology, and food safety applications [12] [13].

Phenyl (and Fluorinated Phenyl)

Phenyl stationary phases, including phenyl-hexyl, biphenyl, and pentafluorophenyl (PFP), offer a unique retention mechanism that combines standard hydrophobic interactions with π-π interactions. This makes them exceptionally selective for analytes containing aromatic rings or conjugated systems, allowing for the separation of structural isomers that are challenging to resolve with alkyl phases. A significant recent application is in the ion-pairing-free analysis of oligonucleotides. A 2025 study systematically evaluated phenyl phases and found that biphenyl and PFP columns provided superior performance, with retention governed primarily by π-π stacking when using methanolic mobile phases [14] [17]. This provides a robust, mass spectrometry-compatible alternative to traditional ion-pair reversed-phase chromatography (IP-RPLC). Fluorinated phases like PFP also exhibit dipole-dipole interactions and enhanced retention for charged bases, offering complementary selectivity to standard phenyl phases [11].

HILIC (Hydrophilic Interaction Liquid Chromatography)

HILIC is the technique of choice for retaining and separating highly polar and hydrophilic compounds that elute near or with the void volume in reversed-phase chromatography. The mechanism involves partitioning analytes between an organic-rich mobile phase (e.g., 70-95% acetonitrile) and a water layer immobilized on the surface of a polar stationary phase. Common stationary phases include bare silica, amino, cyano, and zwitterionic materials. The global HILIC columns market, valued at $193 million in 2025, is growing due to increased adoption in pharmaceutical analysis, biomarker discovery, and metabolomics [15]. HILIC is invaluable for analyzing polar drugs, metabolites, and nucleotides. Method development requires careful optimization of buffer concentration and pH, as electrostatic interactions can play a significant role alongside partitioning. A key advantage is its compatibility with MS detection, as the high organic content promotes desolvation and ionization efficiency [15].

Ion Exchange (IEX)

Ion Exchange Chromatography separates molecules based on their net surface charge. It is predominantly used in the analysis of large biomolecules such as proteins, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), peptides, and oligonucleotides. Separations are typically performed with a salt gradient (e.g., NaCl) in an aqueous buffer, where increasing ionic strength competes with the analyte for binding to the charged stationary phase. IEX is critical for assessing charge heterogeneity of biopharmaceuticals, which is a critical quality attribute. Modern IEX columns often feature bioinert or polymer-based hardware to prevent protein adsorption and degradation, ensuring high recovery and reproducibility [9] [16]. For example, polymer-based columns like the PRP-C18 (despite its name, often used for ion-exchange) are stable across a wide pH range (1-14), enabling separations under aggressive conditions that would destroy silica-based columns [16]. Guard cartridges with bioinert properties are also available to protect analytical columns and extend their lifetime in these demanding applications [9].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Oligonucleotide Analysis Using Ion-Pair Free RPLC on a Biphenyl Column

Application Note: This protocol describes a method for analyzing antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) without the use of ion-pairing reagents, making it highly compatible with mass spectrometry detection. It is based on a 2025 systematic evaluation of phenyl stationary phases [14] [17].

Materials and Reagents:

- Column: Biphenyl or Pentafluorophenyl (PFP) column (e.g., 150 x 2.1 mm, 2.7 µm) [14]

- Mobile Phase A: 50 mM Ammonium Acetate in water, pH 8.0

- Mobile Phase B: Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Reference Standards: Target oligonucleotide and related impurities/shortmers

Instrumentation:

- UHPLC system capable of handling pressures up to 1000 bar

- Column oven

- Mass Spectrometer (e.g., Q-TOF or Triple Quadrupole) or UV detector

Method Parameters:

- Column Temperature: 50 °C

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Injection Volume: 1-5 µL

- Detection: UV at 260 nm and/or MS in negative ionization mode

- Gradient Program:

- Time = 0 min: 5% B

- Time = 20 min: 35% B

- Time = 20.1 min: 95% B (hold for 3 min)

- Time = 23.1 min: 5% B (hold for 5 min for re-equilibration)

Procedure:

- Prepare mobile phases fresh and degas thoroughly.

- Equilibrate the column under initial gradient conditions (5% B) for at least 10 column volumes or until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Inject the oligonucleotide standard and execute the gradient method.

- The retention order is typically: IP-RPLC (TEAA) < biphenyl-RPLC < PFP-RPLC [17].

- For a chemically modified ASO, the biphenyl and PFP phases will show complementarity in selectivity, potentially resolving different impurities.

Protocol 2: Separation of Basic Drugs Using a Polymer-Based C18 Column at High pH

Application Note: This protocol leverages a stable polymer-based C18 column and a high-pH mobile phase to separate basic pharmaceutical compounds in their neutral forms, improving peak shape and broadening the elution window [16].

Materials and Reagents:

- Column: Polymer-based C18 column (e.g., 50 mm length, sub-3µm particles for fast analysis) [16]

- Mobile Phase A: 10 mM Ammonium Bicarbonate in water, pH ~10 (or other compatible alkaline buffer)

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile (HPLC grade)

Instrumentation:

- UHPLC or HPLC system

- Column oven (set to 40 °C)

Method Parameters:

- Column Temperature: 40 °C

- Flow Rate: Adjusted to achieve desired backpressure and separation time (e.g., 0.8 - 1.2 mL/min for a 50 mm column)

- Injection Volume: 1-10 µL

- Detection: UV at 220 nm or 254 nm

- Gradient Program (Generic 5-min example):

- Time = 0 min: 10% B

- Time = 5 min: 90% B

- Time = 5.1 min: 10% B (hold for 2 min for re-equilibration)

Procedure:

- Prepare the alkaline mobile phase A accurately and ensure it is within the pH stability range of the column.

- Condition the polymer column with the starting mobile phase. Note that this column type is stable and does not require the same conditioning precautions as silica-based phases at high pH.

- Inject a mixture of basic drug compounds.

- The method should resolve the compounds with symmetrical peaks and minimal tailing, as the polymer phase is devoid of free silanols and the high pH suppresses analyte ionization.

Decision Framework and Strategic Selection

The following workflow diagram outlines a systematic strategy for selecting the optimal stationary phase based on the physicochemical properties of the analyte and the goals of the analysis.

The strategic selection of stationary phase chemistry is a cornerstone of successful HPLC method development in pharmaceutical research. A one-size-fits-all approach does not exist; rather, the choice must be informed by the chemical structure of the analyte, the desired separation mechanism, and the analytical goals. The contemporary trends in column technology—including the rise of inert hardware to mitigate analyte-surface interactions, the development of novel phenyl phases for challenging separations like ion-pair-free oligonucleotide analysis, and the refinement of robust stationary phases for extended pH and temperature stability—provide scientists with an powerful and expanding toolkit. By applying the principles and protocols outlined in this application note, researchers and drug development professionals can make informed, rational decisions that enhance chromatographic performance, accelerate method development, and ultimately support the delivery of safe and effective pharmaceuticals.

The selection of an appropriate column is a pivotal decision in high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) method development, directly influencing the resolution, efficiency, and speed of separations, particularly in pharmaceutical research where analyzing active compounds and their impurities is critical. The performance of an HPLC column is predominantly governed by the morphology and characteristics of the packing particles. Within this context, three classes of particles have proven highly significant: fully porous particles (FPPs), superficially porous particles (SPPs), and monodisperse particles.

FPPs have been the traditional mainstay of HPLC, valued for their high surface area and loading capacity [19]. SPPs, also known as core-shell particles, feature a solid, non-porous core surrounded by a thin, porous outer shell, which provides enhanced kinetic performance [20] [21]. Finally, monodisperse particles, characterized by their highly uniform size and shape, are emerging as a key technology for producing highly efficient and reproducible columns, not only in chromatography but also in areas like drug delivery [22] [23] [24]. This application note details the properties, performance, and optimal applications of these particle types to guide scientists in selecting the ideal phase for their pharmaceutical separation challenges.

Particle Architectures and Fundamental Properties

The structural differences between particle types define their chromatographic behavior.

Fully Porous Particles (FPPs)

FPPs are traditional spherical silica (or other material) particles that are porous throughout their entire volume [19]. This extensive porous network provides a high surface area-to-volume ratio, which is responsible for their high analyte retention capacity and sample loading capability. They are available in a wide range of particle sizes, pore sizes, and surface modifications, making them versatile for various applications from analytical to preparative scale separations [19].

Superficially Porous Particles (SPPs)

SPPs consist of a solid, impermeable core (typically silica) surrounded by a thin, porous outer shell of a consistent thickness [20] [25]. This architecture shortens the diffusion path length for analytes, significantly reducing the resistance to mass transfer (the C-term in the van Deemter equation). Furthermore, SPPs are typically more uniform in size than traditional FPPs, leading to more homogeneous packed beds and reduced eddy dispersion (the A-term) [25]. While their total surface area is lower than an FPP of the same diameter, modern SPPs retain 50-75% of the surface area, which is often sufficient for analytical retention while conferring major efficiency gains [25].

Monodisperse Particles

Monodisperse particles are defined by their extremely narrow size distribution, often with a relative standard deviation of less than 5% [23]. This uniformity can be applied to both fully porous and superficially porous morphologies. The primary advantage of monodispersity is the ability to form exceptionally uniform and well-ordered packed beds within HPLC columns. This minimizes flow path variations, thereby reducing band broadening and enhancing column efficiency [22]. Such particles are also critical in non-chromatographic applications, such as drug delivery, where size uniformity ensures consistent behavior and performance [23] [24].

Table 1: Comparative Characteristics of HPLC Particle Types

| Property | Fully Porous Particles (FPPs) | Superficially Porous Particles (SPPs) | Monodisperse Particles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Porous throughout | Solid, impermeable core | Can be either porous or solid core |

| Typical Size Range | 1.7 µm to 5 µm and larger | 1.7 µm to 5 µm | Varies (sub-micron to microns) |

| Primary Advantage | High surface area & loadability | High efficiency & fast separations | Highly uniform packing & efficiency |

| Key Limitation | Slower mass transfer for large molecules | Lower surface area & loadability | Complex and costly synthesis |

| Ideal Application | Preparative-scale, impurity profiling | High-speed & high-resolution analysis | High-performance columns, drug delivery |

Comparative Kinetic Performance

The performance of HPLC columns is quantitatively evaluated using kinetic plots, which compare efficiency (plate height, H) versus mobile phase linear velocity (u). The van Deemter equation (H = A + B/u + C·u) describes this relationship, where the A-term represents eddy dispersion, the B-term represents longitudinal diffusion, and the C-term represents resistance to mass transfer [25].

Performance Advantages of SPPs

Columns packed with SPPs demonstrate a superior kinetic performance compared to those packed with similarly sized FPPs. This is due to improvements in all three terms of the van Deemter equation [21] [25]:

- Reduced A-term: The high monodispersity of SPPs and their ability to form more homogeneous beds lead to narrower flow path distributions, reducing eddy dispersion [25].

- Reduced B-term: The solid core limits the volume of stagnant mobile phase within the particle, thereby reducing the contribution of longitudinal diffusion to band broadening [25].

- Reduced C-term: The thin porous shell drastically shortens the distance analytes must diffuse into and out of the particle, significantly lowering the resistance to mass transfer. This is particularly beneficial for separating large biomolecules like proteins, which have slow diffusion rates [20].

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between particle structure and the resulting band broadening contributions that define their kinetic performance.

Diagram 1: Performance pathways of different particle technologies, showing how structure influences band-broadening terms and applications.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance benefit of SPPs is such that 2.7 μm SPPs can provide efficiencies comparable to sub-2 μm FPPs but at roughly half the operating pressure [25]. This allows for UHPLC-level performance on conventional HPLC systems rated for 400 bar. A study comparing 5 μm SPPs to 3.5 and 5 μm FPPs found the SPPs provided superior kinetic performance across the entire relevant range of separation conditions [21].

Table 2: Experimental Kinetic Performance Data

| Particle Type | Particle Size (µm) | Minimum Reduced Plate Height (hₘᵢₙ) | Relative Pressure | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Porous | 5.0 | ~2.0 [21] | Low | Standard analytical separations |

| Fully Porous | 3.5 | ~2.0 [21] | Medium | High-resolution analysis |

| Fully Porous | 1.8 - 2.0 | ~2.0 | Very High | UHPLC, fast separations |

| Superficially Porous | 5.0 | < 2.0 [21] | Low | Fast separations on HPLC systems |

| Superficially Porous | 2.7 | 1.5 - 1.8 [21] | Medium | High-speed & high-efficiency analysis |

| Superficially Porous | 1.7 | ~1.5 [21] | High | UHPLC applications |

Application Notes for Pharmaceutical Separations

Impurity Profiling and Assay

The separation of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from closely related impurities and degradants demands high chromatographic efficiency. SPP-based columns are exceptionally well-suited for this task. For instance, a study demonstrating the separation of an amoxicillin impurity showed that 5 μm SPPs provided superior kinetic performance compared to both 3.5 and 5 μm fully porous particles [21]. The ability to resolve critical pairs with high efficiency makes SPPs a powerful tool for method development in quality control labs.

Biomolecule Separations

The fast mass transfer properties of SPPs are particularly advantageous for separating large biomolecules like proteins and monoclonal antibodies. These molecules have low diffusion coefficients, and the short diffusion path length in the porous shell of SPPs minimizes the time they spend in the stagnant mobile phase, leading to sharper peaks and higher resolution even at elevated flow rates [20]. This enables rapid gradient separations, as demonstrated by the separation of eight proteins in just over 0.75 minutes [20].

High-Throughput Analysis

The combination of high efficiency and low backpressure makes SPP-based columns ideal for high-throughput environments, such as during drug discovery. Methods can be accelerated by using higher flow rates without a severe penalty in efficiency or exceeding instrument pressure limits, thereby increasing laboratory productivity.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Kinetic Performance of HPLC Columns

Purpose: To measure the kinetic performance of an HPLC column by constructing a van Deemter curve and calculating the minimum plate height (Hₘᵢₙ) and optimal linear velocity (uₒₚₜ).

Materials:

- HPLC system with variable wavelength UV-Vis detector or DAD

- Test columns (e.g., packed with FPPs and SPPs of various sizes)

- Mobile phase: Acetonitrile and water (e.g., 50:50 v/v)

- Test analytes: Alkylphenones (e.g., acetophenone, propiophenone, butyrophenone) or other neutral, stable compounds [21]

- Data acquisition and processing software

Procedure:

- System Preparation: Equilibrate the column with the mobile phase at a low flow rate (e.g., 0.2 mL/min) until a stable baseline is achieved.

- Dead Time Determination: Inject a non-retained compound (e.g., uracil or sodium nitrate) to determine the column's void time (t₀).

- Flow Rate Study: Inject a small volume (e.g., 1 µL) of the test analyte solution at a series of increasing flow rates (e.g., 0.2, 0.5, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.5 mL/min). Ensure the system backpressure remains within the limits for the column and instrument.

- Data Collection: For each flow rate, record the retention time (tᵣ) and the peak width at half height (w₀.₅) or the baseline peak width (w).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the linear velocity (u) for each flow rate: u = Column Length (L) / t₀

- Calculate the plate number (N) for each peak: N = 5.54 (tᵣ / w₀.₅)²

- Calculate the plate height (H) for each flow rate: H = L / N

- Plotting: Construct the van Deemter curve by plotting plate height (H) versus linear velocity (u).

Interpretation: The curve will show a minimum plate height (Hₘᵢₙ) at the optimal linear velocity (uₒₚₜ). Compare Hₘᵢₙ and the flatness of the C-term region for different columns. Columns with lower Hₘᵢₙ and flatter C-terms generally provide higher efficiency, especially at faster flow rates.

Protocol: Synthesis of Monodisperse Polymeric Particles for Biosystem Immobilization

Purpose: To synthesize monodisperse polymeric particles for use as matrices for immobilizing enzymes, proteins, or cells [24].

Materials:

- Monomers (e.g., styrene, divinylbenzene for synthetic polymers; or chitosan, alginate for natural polymers)

- Initiator (e.g., potassium persulfate, AIBN)

- Surfactant/Stabilizer (e.g., sodium dodecyl sulfate, polyvinyl alcohol)

- Deionized water and organic solvents as needed

- Nitrogen gas source

- Reaction flask with condenser, stirrer, and heating mantle

Procedure:

- Aqueous Phase Preparation: Charge the reaction flask with deionized water and surfactant. Purge the solution with nitrogen to remove oxygen.

- Monomer Mixture: Combine the primary monomer and cross-linker in a separate vial. Add a hydrophobic initiator if required.

- Emulsion/ Dispersion Polymerization: Slowly add the monomer mixture to the aqueous phase with vigorous stirring to form a stable emulsion or dispersion.

- Polymerization: Heat the reaction mixture to the initiation temperature (e.g., 70°C) with continuous stirring under a nitrogen atmosphere. Maintain the temperature for several hours to complete the reaction.

- Purification: After cooling, filter or centrifuge the resulting particle suspension. Wash the particles repeatedly with water and/or solvent to remove unreacted monomers and surfactant.

- Characterization: Determine particle size and monodispersity using dynamic light scattering (DLS) or electron microscopy. Confirm the presence of functional groups for immobilization via FT-IR.

Notes: The specific ratios of monomer, cross-linker, initiator, and surfactant, as well as stirring speed and temperature, are critical for achieving monodispersity and must be optimized. Natural polymers like chitosan or alginate can be formed into monodisperse particles using emulsification-gelation techniques [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Particle Technology and Applications

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alkylphenone Homologous Series | Neutral test compounds for evaluating column efficiency and hydrophobic selectivity [21]. | Constructing van Deemter plots for kinetic performance comparison. |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | A volatile buffer for LC-MS/MS compatibility; effective buffering range pH 3.5-5.5 [26]. | Mobile phase modifier for analyzing ionizable pharmaceutical compounds. |

| Base-Resistant C18 Column | A column with a stationary phase stable at high pH (e.g., >9) [26]. | Analyzing basic compounds in their non-ionized form for improved peak shape. |

| Chitosan | A natural, biocompatible polymer with functional groups for chemical modification [24]. | Synthesis of monodisperse particles for enzyme immobilization or drug delivery. |

| Porous Silica Microspheres | The foundational support material for most HPLC stationary phases [19]. | Manufacturing of fully porous and superficially porous HPLC packing materials. |

| Corona Discharge Ion Source | A source of unipolar ions for charge reduction [22]. | Producing monodisperse particles via electrospray by preventing Coulomb explosions. |

The advancement of particle technology has provided chromatographers with powerful tools to address complex separation challenges in pharmaceutical research. Fully porous particles remain the workhorse for methods requiring high loadability, such as preparative-scale purification. Superficially porous particles offer a compelling balance of high efficiency, speed, and moderate operating pressure, making them an excellent first choice for high-resolution analytical methods, including impurity profiling and biomolecule separation. The emerging emphasis on monodisperse particles, both as HPLC packings and for biotechnology applications, underscores the critical importance of particle uniformity for achieving superior and reproducible performance. By understanding the properties and advantages of each particle type, scientists can make an informed, application-driven selection to optimize their chromatographic methods.

The Rise of Bioinert and Metal-Free Hardware for Metal-Sensitive Compounds

For researchers in pharmaceutical development, the analysis of metal-sensitive compounds presents a persistent analytical challenge. Conventional stainless steel high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) hardware can cause unwanted interactions with electron-rich analytes, leading to compromised data quality and unreliable results [27]. These interactions are particularly problematic for critical pharmaceutical compounds including oligonucleotides, phosphorylated lipids, phosphopeptides, and metal-coordinating small molecules [27] [28] [29].

Bioinert and metal-free HPLC hardware technologies have emerged as essential solutions, specifically engineered to prevent analyte loss, maintain peak integrity, and ensure the reproducibility required in pharmaceutical research and quality control [27] [30]. This application note details the implementation of these technologies, providing validated protocols and performance data to guide column selection for the analysis of metal-sensitive pharmaceutical compounds.

Bioinert and metal-free HPLC columns address the limitations of traditional stainless steel hardware through several advanced engineering approaches.

Bioinert Coated Stainless Steel: These columns feature an advanced surface coating applied to the stainless steel column body and frits. This coating creates a metal-free barrier for analytes while maintaining the mechanical resilience and high-pressure stability of traditional stainless steel hardware [27] [28]. They are compatible with a wide range of solvents and do not require special connectors [27].

PEEK-Lined Stainless Steel: This design utilizes stainless steel for external pressure resistance while lining the entire internal flow path with inert PEEK (polyetheretherketone) polymer, including PEEK frits [30] [31]. This creates a fully metal-free environment for samples, preventing interactions while maintaining pressure capabilities [30].

Titanium Hardware: While known for biocompatibility, titanium is not truly bioinert as metal erosion can still occur, potentially leading to contamination of the silica bed and interactions with silanol groups [27].

The primary advantage of bioinert coated over PEEK-lined hardware is reduced hydrophobicity, minimizing hydrophobic interactions with polar analytes [30]. For most pharmaceutical applications involving metal-sensitive compounds, both technologies demonstrate superior performance compared to passivation techniques or mobile phase additives, which offer only temporary solutions and can interfere with mass spectrometry detection [27] [28].

Application Performance Data

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Extensive testing across multiple compound classes demonstrates the significant performance advantages of bioinert hardware for metal-sensitive analytes.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Stainless Steel vs. Bioinert Hardware

| Analyte Class | Specific Analytes | Performance Metric | Stainless Steel Hardware | Bioinert Hardware | Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylated Nucleotides | AMP, ADP, ATP | Peak Tailing Factor | 2.6 - 4.8 | 1.3 - 1.7 | 50-65% reduction | [28] |

| Phosphopeptides | Peptide "c" (pY) | Relative Signal Height | 50% | 100% | 2x increase | [28] |

| Phosphopeptides | Peptide "b", "d" (pS, pY) | Detectability | Not detectable | Clear detection | Complete recovery | [28] |

| Acidic Metabolites | Glutamine, Glutamate, Malate | Peak Shape | Significant tailing | Sharp peaks | Improved resolution | [28] |

| Oligonucleotides | Phosphorothioated RNA | Peak Area/Height | Baseline | Up to 2x higher | 100% increase | [27] |

| Triphosphates | Nucleotide triphosphates | Peak Shape & Recovery | Poor shape, low recovery | Excellent shape, high recovery | Marked improvement | [31] |

Application-Specific Performance

Oligonucleotide Analysis: For phosphorothioated RNA analysis using ion-pair reversed-phase liquid chromatography (IP-RPLC), bioinert columns demonstrated up to twice the peak area and height compared to regular stainless steel columns [27]. In HILIC mode, bioinert coated columns required only 8 injections for conditioning compared to 20 for stainless steel and 14 for PEEK-lined columns, with minimal differences (<10%) between initial and final peak areas [27].

Lipidomic Applications: For the analysis of signaling lipids containing phosphate groups, bioinert coated columns enabled long-term reproducible results across different matrices, with one method identifying approximately 700 distinct molecules in under 10 minutes [27].

Pharmaceutical Small Molecules: Bioinert hardware provides critical advantages for compounds with coordinating functional groups, including mycotoxins (fumonisins), chelating compounds (hinokitiol), and metabolites in tryptophan metabolism [27].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Analysis of Phosphorylated Nucleotides (AMP, ADP, ATP)

This method is optimized for the separation and quantification of phosphorylated nucleotides using HILIC chromatography with bioinert hardware.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Nucleotide Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function | Supplier Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinert HILIC Column | 2.1 × 150 mm, 2.7 μm | Separation of polar phosphorylated compounds | Agilent Altura HILIC-Z [28] |

| Acetonitrile (LC-MS Grade) | ≥99.9% | Organic mobile phase component | Various |

| Ammonium Acetate | ≥99.0% | Volatile buffer salt | Various |

| Formic Acid | LC-MS Grade | Mobile phase additive for ionization | Various |

| Phosphorylated Nucleotides | AMP, ADP, ATP standards | Analytical standards for calibration | Sigma-Aldrich [28] |

Method Parameters:

- Column: Bioinert HILIC column (e.g., Agilent Altura HILIC-Z, 2.1 × 150 mm, 2.7 μm) [28]

- Mobile Phase A: Water with 0.1% formic acid

- Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid

- Gradient Program:

- 0 min: 2% B

- 1.5 min: 2% B

- 11.5 min: 32% B

- 12 min: 2% B

- 18 min: 2% B

- Flow Rate: 0.4 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 40°C

- Injection Volume: 1-5 μL

- Detection: MS with ESI+ ionization

Critical Notes: This method utilizes low concentrations of formic acid (0.1%) to maintain compatibility with mass spectrometry while providing efficient ionization. The bioinert hardware is essential to prevent adsorption of phosphate groups to metal surfaces, which would cause poor peak shapes and reduced sensitivity [28].

Protocol 2: Analysis of Therapeutic Oligonucleotides Using IP-RP

This protocol describes the analysis of phosphorothioated oligonucleotides using ion-pair reversed-phase chromatography with bioinert hardware.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Oligonucleotide Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function | Supplier Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioinert C18 Column | 2.1 mm ID, 1.9-2.7 μm | Separation of oligonucleotides | YMC Accura Triart Bio C18 [30] |

| Hexafluoroisopropanol (HFIP) | ≥99.5% | Ion-pairing agent component | Various |

| N,N-Diisopropylethylamine (DIPEA) | ≥99.5% | Ion-pairing agent component | Various |

| Methanol (LC-MS Grade) | ≥99.9% | Organic modifier | Various |

| Therapeutic Oligonucleotide | Phosphorothioated RNA | Analytic of interest | Prepared in-house |

Method Parameters:

- Column: Bioinert C18 column (e.g., YMC Accura Triart Bio C18, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.9 μm) [30]

- Mobile Phase A: 100 mM HFIP, 5 mM DIPEA in water

- Mobile Phase B: 100 mM HFIP, 5 mM DIPEA in methanol

- Gradient Program:

- 0 min: 10% B

- 15 min: 40% B

- 15.1 min: 95% B

- 18 min: 95% B

- 18.1 min: 10% B

- 22 min: 10% B

- Flow Rate: 0.3 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 60°C

- Detection: UV at 260 nm or MS detection

Critical Notes: The use of bioinert hardware is particularly crucial for longer oligonucleotides, which show stronger interaction with metal surfaces [27]. For MS-compatible methods without ion-pairing agents, alternative approaches using ammonium bicarbonate as a volatile additive with bioinert C18 columns have been successfully demonstrated [27].

Protocol 3: Native IEX-MS Analysis of Intact Antibodies

This method enables the analysis of intact antibodies under native conditions using bioinert ion-exchange columns coupled to mass spectrometry.

Method Parameters:

- Column: Bioinert coated cation exchange column (e.g., YMC Accura BioPro IEX, 2.1 mm ID) [27] [30]

- Mobile Phase A: 20 mM ammonium acetate, pH 5.6, containing 2% acetonitrile

- Mobile Phase B: 20 mM ammonium acetate, 1 M sodium chloride, pH 5.6, containing 2% acetonitrile

- Gradient Program:

- Varied by specific mAb (e.g., 47-58% B over 55 min for trastuzumab)

- Flow Rate: 0.2-0.3 mL/min

- Column Temperature: 25°C

- Detection: MS with nano-electrospray ionization

Critical Notes: The smaller internal diameter (2.1 mm) available with bioinert columns helps reduce flow rates required for nano-electrospray ionization MS detection [27]. The bioinert hardware prevents metal-induced oxidation and interactions that could compromise the analysis of large biomolecules under native conditions.

Practical Implementation Guide

Column Selection Criteria

When selecting bioinert or metal-free columns for pharmaceutical applications, consider these key parameters:

- Analyte Properties: Electron-rich compounds ( oligonucleotides, phosphorylated species, acidic metabolites) with coordinating moieties strongly benefit from bioinert hardware [27] [28].

- Detection Method: For LC-MS applications, bioinert columns prevent signal suppression and enable the use of minimal MS-compatible additives without compromising recovery [27] [28].

- Pressure Requirements: Bioinert coated stainless steel columns maintain the high-pressure capabilities of traditional hardware (up to 1000 bar for UHPLC), while PEEK-lined columns have moderate pressure limits [30].

- Solvent Compatibility: Bioinert coated columns offer broader solvent compatibility compared to PEEK-lined columns, which may have limitations with certain organic solvents [27].

Method Transfer Considerations

When transferring methods from conventional to bioinert columns:

- Expect Improved Performance: Significantly higher recovery and better peak shapes are typically observed, which may require adjustment of acceptance criteria [27] [28] [31].

- Verify Selectivity: While the stationary phase may be identical, the absence of metal interactions may subtly affect selectivity for metal-coordinating compounds [32].

- Eliminate Passivation Steps: Remove column passivation procedures (e.g., EDTA or phosphoric acid flushes) from methods as they are unnecessary with bioinert hardware [27].

The adoption of bioinert and metal-free HPLC hardware represents a significant advancement in the analysis of metal-sensitive pharmaceutical compounds. These technologies effectively address the fundamental limitation of conventional stainless steel hardware – unwanted metal-analyte interactions – enabling reliable, high-resolution results with precision and reproducibility essential for drug development [27].

The experimental protocols and performance data presented demonstrate that bioinert hardware provides quantifiable improvements in analyte recovery, peak shape, and sensitivity for critical compound classes including oligonucleotides, phosphorylated compounds, and therapeutic antibodies. Implementation of these technologies throughout the pharmaceutical development workflow ensures data integrity while reducing analytical challenges associated with metal-sensitive compounds.

The selection of an appropriate High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) column is a critical determinant of success in pharmaceutical research and development. The year 2025 has witnessed significant advancements in column technology, particularly for small-molecule reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC), driven by the need for improved separation efficiency, alternative selectivity, and enhanced analysis of challenging compounds [9]. This application note provides a detailed overview of the latest trends and commercially available columns, equipping scientists with the knowledge and protocols needed to leverage these innovations for superior chromatographic method development.

The global HPLC columns market, valued at USD 4.98 billion in 2025, underscores the importance of this technology, with the pharmaceutical segment accounting for a dominant 29.8% share [33]. A key trend is the move towards more specialized and customized columns for niche applications, including biopharmaceutical analysis and metabolomics [33]. This document synthesizes the most recent product information and technical data to serve as a practical guide for researchers aiming to enhance their analytical workflows.

Key Trends and Column Innovations in 2025

The landscape of small-molecule RPLC columns in 2025 is characterized by three dominant trends: the refinement of particle and hardware technology, the growing adoption of inert columns, and the expansion of chemistries offering orthogonal selectivity. These developments collectively enhance peak shapes, improve analyte recovery for metal-sensitive compounds, and provide scientists with a broader toolkit for method development [9].

Advances in Particle Technology

Manufacturers continue to innovate in particle design to boost column efficiency and peak capacity. Superficially porous particles (SPP), also known as fused-core or solid-core particles, remain at the forefront due to their ability to provide high efficiency with lower backpressure compared to fully porous particles. Simultaneously, monodisperse fully porous particles (MFPP) are being engineered for higher efficiency and improved performance in specific applications, such as oligonucleotide separation without ion-pairing reagents [9].

Table 1: New Small-Molecule RPLC Columns for Alternative Selectivity (2025)

| Product Name | Manufacturer | Stationary Phase | Particle Technology | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halo 90 Å PCS Phenyl-Hexyl [9] | Advanced Materials Technology | Phenyl-Hexyl | Superficially Porous | Enhanced peak shape for basic compounds; alternative selectivity to C18 via π-π interactions; optimized for MS. |

| Aurashell Biphenyl [9] | Horizon Chromatography | Biphenyl | Superficially Porous | Utilizes hydrophobic, π-π, and dipole interactions; suited for metabolomics and isomer separations; 100% aqueous compatible. |

| Evosphere C18/AR [9] | Fortis Technologies Ltd. | C18 and Aromatic ligands | Monodisperse Fully Porous | Designed for oligonucleotide separation without ion-pairing reagents; available in various particle sizes. |

| SunBridge C18 [9] | ChromaNik Technologies Inc. | C18 | Fully Porous (5 µm) | High pH stability (pH 1-12); designed for general-purpose use with a broad application range. |

| Raptor C8 LC Columns [9] | Restek Corporation | C8 (Octylsilane) | Superficially Porous (2.7 µm) | Faster analysis times with selectivity similar to C18; suitable for a wide range of acidic to slightly basic compounds. |

The Rise of Bio-inert and Inert Columns

A persistent trend is the increasing availability of columns with inert hardware, designed to minimize surface interactions with analytes that are sensitive to metal surfaces, such as phosphorylated compounds, chelating molecules, and certain pharmaceuticals [9]. This is achieved through various column hardware passivation techniques or the use of polyether ether ketone (PEEK) liners. The primary benefit is enhanced peak shape and improved analyte recovery, which is crucial for accurate quantification in bioanalytical and pharmaceutical workflows [9]. This trend aligns with the broader industry focus on "biocompatible" systems for analyzing biomolecules.

Table 2: New Inert RPLC Columns and Guards (2025)

| Product Name | Manufacturer | Stationary Phase | Key Feature | Target Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halo Inert [9] | Advanced Materials Technology | Not Specified (RPLC) | Passivated hardware creating a metal-free barrier | Phosphorylated compounds and metal-sensitive analytes. |

| Evosphere Max [9] | Fortis Technologies Ltd. | Not Specified | Inert hardware with monodisperse porous silica | Enhanced peptide recovery and sensitivity. |

| Restek Inert HPLC Columns [9] | Restek Corporation | Polar-embedded alkyl (L68) and C18 (L1) | Inert hardware | Chelating PFAS and pesticide compounds. |

| Raptor Inert HPLC Columns [9] | Restek Corporation | HILIC-Si, FluoroPhenyl, Polar X | Superficially porous particles with inert hardware | Metal-sensitive polar compounds. |

| Force/Raptor Inert Guard Cartridges [9] | Restek Corporation | Biphenyl, C18, and others | Inert hardware in guard format | Protecting inert analytical columns; improving response for metal-sensitive compounds. |

Expansion of Commercially Available Capillary-Scale Columns

The adoption of capillary-scale LC (columns with inner diameters of 0.075–0.50 mm) is accelerating, particularly in 'omics' fields and other applications with limited sample availability [34]. Recent advancements have expanded the commercial availability of these systems and their corresponding columns. The benefits are substantial: increased electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) sensitivity, dramatic reductions in solvent consumption, and the ability to utilize non-traditional column formats like pillar arrays [34]. Vendors are now offering a wider range of capillary columns in various lengths, inner diameters, and chemistries, making method translation from analytical-scale more accessible.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful method development and implementation rely on a suite of essential materials. The following table details key solutions for working with the latest RPLC columns.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Modern RPLC

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Advanced Inert Guard Columns [9] | Protect expensive analytical columns from particulates and irreversibly adsorbed compounds; specifically designed with inert hardware to match the performance of new analytical columns. | Essential for extending column lifetime, especially when analyzing complex biological or environmental matrices. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Compatible Mobile Phase Additives [9] | Low ionic strength volatile acids (e.g., formic acid) and buffers (e.g., ammonium formate) that do not suppress ionization or cause source fouling in MS detection. | Critical for achieving high sensitivity in LC-MS workflows. Many 2025 columns are optimized for these conditions. |

| Wide pH Range Buffers [9] | Mobile phase buffers that allow operation across a wide pH range (e.g., pH 2-12) to leverage the stability of modern hybrid and advanced silica particles. | Enables fine-tuning of selectivity for ionizable compounds, a key strategy in method development. |

| Specialized Solvents for HILIC | High-purity acetonitrile, water, and volatile salts for hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography, a complementary technique to RPLC for polar analytes. | Used with HILIC phases (available in many 2025 product lines) to retain and separate highly polar compounds not retained in RPLC [35]. |

| Column Performance Test Mixtures | Standardized mixtures of compounds with known properties (e.g., acids, bases, neutrals) for evaluating column efficiency, peak asymmetry, and retention. | Used for initial column qualification and for periodic monitoring of column performance over its lifetime. |

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Approach to Column Screening and Selectivity Evaluation

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for evaluating the performance of new 2025 RPLC columns for separating a mixture of small-molecule pharmaceutical compounds, including acidic, basic, and neutral analytes.

Materials and Equipment

- HPLC/UHPLC System: Capable of handling pressures up to 1000 bar and generating gradient mobile phases. Should include a diode-array detector (DAD) or similar.

- Columns to be Evaluated: A selection of at least 3-4 columns from Table 1 (e.g., Halo Phenyl-Hexyl, Aurashell Biphenyl, a C18 phase for reference, and an inert column if analyzing metal-sensitive compounds).

- Guard Columns: Corresponding inert guard cartridges matching the analytical columns used [9].

- Mobile Phase Components: LC-MS grade water, acetonitrile, and methanol. Ammonium formate or ammonium acetate, formic acid, and phosphoric acid for buffer preparation.

- Analyte Standards: A mixture of proprietary pharmaceutical compounds or a standardized test mixture containing protonatable bases (e.g., amitriptyline), ionizable acids (e.g., naproxen), and neutral compounds (e.g., acetophenone).

Procedure

Step 1: Mobile Phase Preparation

- Prepare Mobile Phase A: 10 mM Ammonium Formate in water, pH adjusted to 3.0 with formic acid.

- Prepare Mobile Phase B: Acetonitrile.

- Filter all mobile phases through a 0.22 µm nylon or PVDF membrane and degas by sonication under vacuum or with continuous helium sparging.

Step 2: Instrument and Column Conditioning

- Install the first column and its corresponding guard cartridge according to manufacturer instructions.

- Set the column temperature to 30°C and the detection wavelength as appropriate for your analytes (e.g., 254 nm).

- Condition the column by pumping a sequence of solvents at a slow flow rate (e.g., 0.2 mL/min) as follows:

- 5 column volumes (CV) of 50:50 Acetonitrile/Water (no buffer)

- 10 CV of the initial gradient starting condition (e.g., 5% B in A)

- Hold at initial conditions until a stable baseline is achieved.

Step 3: Initial Gradient Scouting Run

- Perform an initial fast gradient to profile the column's performance.

- Gradient Program: 5% B to 95% B over 10 minutes.

- Hold: 95% B for 2 minutes.

- Equilibration: 5% B for 3 minutes.

- Flow Rate: As recommended for the column dimension (e.g., ~0.5 mL/min for a 4.6 mm i.d. column).

- Injection Volume: 1-5 µL of the standard mixture.

Step 4: Data Collection and Analysis

- For each column, record the chromatogram and calculate the following parameters for each peak in the standard mixture:

- Retention Factor (k)

- Peak Asymmetry (As)

- Theoretical Plates per Meter (N/m)

- Resolution (Rs) between the most critical pair of analytes.

Step 5: Selectivity Optimization

- Based on the initial results, select the two most promising columns showing different selectivity.

- For these columns, systematically optimize the gradient time (e.g., 5 to 20 minutes) and temperature (e.g., 30°C to 50°C) to improve resolution and/or reduce run time.

- If analytes are ionizable, consider adjusting the pH of Mobile Phase A within the column's specified operating range (e.g., pH 2.5 and 4.5) to fine-tune selectivity.

Step 6: Final Method Validation

- On the selected optimal column, perform a basic validation by injecting the standard mixture in triplicate to assess the method's precision (%RSD of retention time and peak area).

The logical workflow for this protocol, from preparation to data analysis, is outlined in the following diagram:

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The data collected from the experimental protocol should be systematically compared to guide column selection.

Table 4: Data Analysis Table for Column Performance Comparison

| Analyte / Parameter | Column A (e.g., C18) | Column B (e.g., Biphenyl) | Column C (e.g., Phenyl-Hexyl) | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Plates (N/m) | > 50,000 (for 5µm particles) | |||

| Peak Asymmetry (As) | 0.8 - 1.5 | |||

| Retention Factor (k) - Analyte 1 | 2 - 10 | |||

| k - Analyte 2 | 2 - 10 | |||

| Resolution (Rs) - Critical Pair | > 1.5 | |||

| %RSD Retention Time (n=3) | < 1.0% |

Interpretation Guide:

- Efficiency and Peak Shape: Columns with higher theoretical plates and peak asymmetry closer to 1.0 are generally preferred, indicating superior kinetic performance [9].

- Retention and Selectivity: Significant differences in retention factor (k) for specific analytes between a C18 column and an alternative phase (e.g., biphenyl) indicate different selectivity. This is often due to additional interactions like π-π bonding or dipole-dipole interactions [9]. A column that provides baseline resolution (Rs > 1.5) for the most challenging pair of analytes is a strong candidate.

- Precision: Low %RSD values indicate a robust method on the given column.

The 2025 market for small-molecule RPLC columns offers pharmaceutical scientists a powerful and expanding array of tools to solve challenging separation problems. The key trends—advanced particle technology, widespread availability of inert hardware, and diverse chemistries for alternative selectivity—provide unprecedented opportunities for method optimization. By adopting a systematic screening protocol as outlined in this application note, researchers can efficiently navigate these new options to develop robust, sensitive, and efficient LC methods that accelerate drug development and ensure product quality.

Developing Robust HPLC Methods: From Column Matching to Complex Separation Strategies

A Systematic Approach to Matching Column Chemistry with Analyte Properties

Within pharmaceutical research and development, High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) serves as a cornerstone analytical technique for the separation, identification, and quantification of drug-related compounds. The heart of any HPLC system is the column, and its selection—specifically, the chemistry of the stationary phase—directly dictates the success of the separation [36]. A systematic approach to matching this column chemistry with the properties of the analyte is not merely a matter of convenience; it is fundamental to achieving the resolution, efficiency, and reproducibility required in pharmaceutical analysis, from quality control of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) to impurity profiling and stability studies [37].

The modern chromatographer is faced with a "bewildering array of stationary-phase choices" [38]. This application note provides a structured framework to navigate this complexity, enabling scientists to make informed, rational decisions in HPLC column selection for pharmaceutical compounds.

Fundamental Principles of Analyte-Stationary Phase Interactions

Retention and separation in reversed-phase HPLC, the most common mode for pharmaceutical analysis, are governed by the equilibrium of the analyte between the mobile phase and the bonded stationary phase [38]. The primary molecular interactions influencing this equilibrium include:

- Dispersive (Hydrophobic) Interactions: These are the dominant retention mechanisms in reversed-phase separations, especially with alkyl ligands like C18 and C8. Retention increases with the hydrophobicity of the analyte [38].

- Charge Transfer (π–π) Interactions: These occur when the stationary phase or analyte contains aromatic rings. Phases like biphenyl or phenylhexyl can provide enhanced selectivity for planar compounds or those with unsaturated bonds through π–π interactions [9] [38].

- Dipole–Dipole and Hydrogen Bonding Interactions: These are critical for retaining polar compounds. Stationary phases with polar embedded groups or cyano ligands enhance this type of interaction, offering alternative selectivity for hydrophilic molecules [39] [38].

- Electrostatic Interactions: These occur between ionized sites on the analyte and charged sites on the stationary phase surface, such as residual silanol groups on silica-based particles. While often a source of peak tailing for basic compounds, this mechanism can be managed with inert or specially endcapped columns [9] [38].

A Systematic Framework for Column Selection

Navigating column selection systematically requires a sequence of logical decisions, from defining the analytical goal to fine-tuning the final method. The workflow below outlines this step-by-step process, which is detailed in the subsequent sections.

Step 1: Characterize Analyte Properties

The first step is a thorough analysis of the physicochemical properties of the target pharmaceutical compound(s).

- Polarity/Hydrophobicity: Determine the log P value or assess the functional groups. Polar compounds (e.g., metabolites, sugars) are poorly retained on standard C18 phases and may require polar-embedded, HILIC, or normal-phase methods [39] [40].

- Ionic Character (pKa): The acid-base character of the analyte dictates its state at a given mobile phase pH. Ionizable compounds require careful control of pH and may benefit from columns designed to mitigate undesirable interactions with residual silanols [39] [37].

- Molecular Size and Structure: The molecular weight guides the choice of pore size. For instance, a pore size of 120 Å is suitable for most small-molecule drugs (<2000 Da), while larger pores (e.g., 300 Å) are necessary for biomolecules like proteins and peptides [36] [41]. The presence of aromatic rings or chiral centers also influences phase selection.

Step 2: Select the Appropriate Chromatographic Mode

Based on the analyte properties, the most suitable chromatographic mode can be selected. Table 1 summarizes the primary modes and their typical pharmaceutical applications.

Table 1: Selection of HPLC Mode Based on Analyte Properties

| Mode | Stationary Phase Polarity | Mobile Phase Polarity | Elution Order | Ideal for Analyte Properties | Common Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversed-Phase (RPLC) [37] [40] | Non-polar (e.g., C18, C8) | Polar (Water/MeCN/MeOH) | More polar first, less polar last | Non-polar to moderately polar; hydrocarbon-soluble | API potency, impurity profiling, dissolution testing [37] |

| Normal-Phase (NPLC) [37] [40] | Polar (e.g., Silica, Diol, Amino) | Non-polar (Organic solvents) | Less polar first, more polar last | Polar; soluble in organic solvents | Separation of isomers, phospholipids |

| Hydrophilic Interaction (HILIC) [40] | Polar (e.g., Amide, Diol) | High Organic (>70% ACN) | More polar last, less polar first | Highly polar, hydrophilic | Polar metabolites, carbohydrates, aminoglycosides [40] |

| Ion-Exchange (IEX) [37] [40] | Charged (Cationic or Anionic) | Aqueous buffer (increasing ionic strength) | Based on charge strength | Charged molecules (proteins, nucleotides) | Purification of biopharmaceuticals (mAbs, oligonucleotides) [9] [40] |

| Size-Exclusion (SEC) [37] [40] | Inert porous matrix | Aqueous buffer | Larger first, smaller last | Biomolecules, polymers | Aggregate analysis of proteins, monoclonal antibodies [37] |

Step 3: Choose Stationary Phase Chemistry and Selectivity

Within the reversed-phase mode—the most prevalent in pharma—selecting the right ligand is crucial for achieving the required selectivity. Table 2 provides a guide to common reversed-phase stationary phases.

Table 2: Guide to Reversed-Phase Stationary Phases for Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Stationary Phase | Primary Interactions | Selectivity For | Typical Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| C18 (Octadecyl) [39] [40] | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic molecules; general-purpose workhorse | Potency assays, method development starting point [39] |