Strategies to Reduce Spectral Interference in Spectrophotometric Analysis: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing spectral interference in spectrophotometric analysis.

Strategies to Reduce Spectral Interference in Spectrophotometric Analysis: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing spectral interference in spectrophotometric analysis. It covers the foundational principles of interference types, explores traditional and advanced methodological corrections, details troubleshooting and optimization strategies for complex samples, and validates methods through comparative analysis of modern techniques. By integrating insights from atomic spectroscopy, UV-Vis, and cutting-edge approaches like artificial intelligence, this resource delivers practical solutions for achieving accurate and reliable analytical results in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications.

Understanding Spectral Interference: Mechanisms and Impact on Analytical Accuracy

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent or Drifting Readings During Analysis

- Potential Cause 1: Aging instrument lamp or unstable source.

- Solution: Check and replace the aging lamp. Allow the instrument sufficient warm-up time to stabilize before use [1].

- Potential Cause 2: Uncorrected background absorption or scattering.

- Potential Cause 3: Sample-related issues, such as a dirty cuvette or debris in the light path.

- Solution: Inspect the sample cuvette for scratches, residue, or improper alignment. Check for and clean any debris from the optics [1].

Problem: Unexpected High Signal or Positive Bias in Results

- Potential Cause 1: Direct spectral overlap from an interfering element.

- Potential Cause 2: Elevated background due to scattering from particulates or broad absorption bands from molecular species in the sample matrix [2].

- Solution: Use a background correction method. The D2 lamp method is common for correcting broad, structured background. The Zeeman effect background correction is another powerful technique that applies a magnetic field to differentiate analyte absorption from background absorption [2].

- Potential Cause 3: The element causing the signal increase is present in the sample but not in the calibration standards.

- Solution: Use standard preparation to introduce the interfering element into all calibration standards as a matrix-matching component, so its effect is subtracted via the calibration curve [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is spectral interference in simple terms? A1: Spectral interference occurs when a signal from something other than your target analyte is mistakenly measured by the instrument. This "something else" can be another element with a similar emission/absorption wavelength, or broad background absorption and scattering from molecules or particles in the sample. This leads to an incorrectly high reading for your analyte [5] [2].

Q2: When is spectral interference most likely to occur? A2: It is common in complex samples containing a mixture of elements, particularly at trace levels in the presence of a high-concentration matrix. Examples include analyzing precious metals in geological samples [4], or biological/biopharmaceutical samples with complex matrices [6].

Q3: What is the single best way to deal with spectral interference? A3: Avoidance is strongly preferred over correction. If your instrument has the capability, select an alternative analytical wavelength for your analyte that is free from known interferences. This is often more robust and reliable than attempting to correct for the overlap mathematically [3].

Q4: How can I minimize the impact of spectral interference before running my sample? A4: Careful sample and calibration standard preparation is key. By matching the matrix of your calibration standards to that of your sample (i.e., adding the interfering element to your standards), you can calibrate its effect out of the final result [5]. Increasing the atomization temperature can also help by breaking down interfering molecular species [2].

Q5: My ICP-MS results are plagued by polyatomic interferences. What are my options? A5: For ICP-MS, collision-reaction cell (CRC) technology is the primary tool. Cells can use inert gas collisions (to dissipate interference energy) or reactive gases (like ammonia or oxygen) to chemically convert interferences or analytes into different species, thereby removing the overlap [3] [4].

The tables below consolidate key quantitative information on interference types and correction methods for easy reference.

Table 1: Common Types of Spectral Interference in Atomic Spectroscopy

| Interference Type | Description | Example | Primary Technique Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Spectral Overlap | An interfering element has an emission or absorption line that directly overlaps with the analyte's line [5]. | As 228.812 nm line on Cd 228.802 nm line [3]. | ICP-OES, AAS |

| Polyatomic Ion Interference | Ions composed of multiple atoms (from plasma gas, solvent, or matrix) have the same mass-to-charge ratio as the analyte [4]. | 40Ar35Cl+ on 75As+; 63Cu40Ar+ on 103Rh+ [4]. | ICP-MS |

| Refractory Oxide Interference | Oxide species formed from matrix elements interfere with the target analyte mass or wavelength [4]. | 90Zr16O+ on 106Pd+ [4]. | ICP-MS, ICP-OES |

| Background Absorption/Scattering | Broad-band absorption by undissociated molecules or scattering of source radiation by particulates in the flame or furnace [2]. | Molecular species in a flame; particulates scattering light at wavelengths <300 nm [2]. | AAS |

Table 2: Summary of Spectral Interference Correction and Avoidance Methods

| Method | Principle | Example & Key Parameter | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative Wavelength Selection | Moving the measurement to an interference-free emission/absorption line of the analyte [3]. | Selecting a secondary, clean analytical line for the element. | Preferred avoidance method; requires knowledge of spectral database [3]. |

| Collision-Reaction Cell (ICP-MS) | Using gas-phase reactions or collisions to remove polyatomic interferences before mass analysis [3] [4]. | Using NH3 gas to eliminate Cu/Ar clusters on Rh [4]. Optimized gas flow is critical (e.g., ~1 mL/min for NH3) [4]. | Powerful for complex matrices; requires method development. |

| Mathematical Correction | Applying an equation to subtract the calculated contribution of the interference from the gross signal [3]. | Correction = Gross Signal - (Interferent Conc. × Correction Coefficient). | Assumes instrument response is stable; can increase measurement uncertainty [3]. |

| Background Correction (AAS) | Measuring and subtracting the background signal adjacent to the analyte peak. | D2 Lamp: Corrects for broad background [2]. Zeeman Effect: Uses magnetic splitting to distinguish analyte/background [2]. | Essential for accurate AAS in complex matrices. |

Experimental Protocol: Mitigating Interference in Complex Matrices

This protocol details the use of a Dynamic Reaction Cell (DRC) in ICP-MS to reduce polyatomic interferences for the determination of Ruthenium (Ru) in a copper-nickel-chloride matrix, based on published methodology [4].

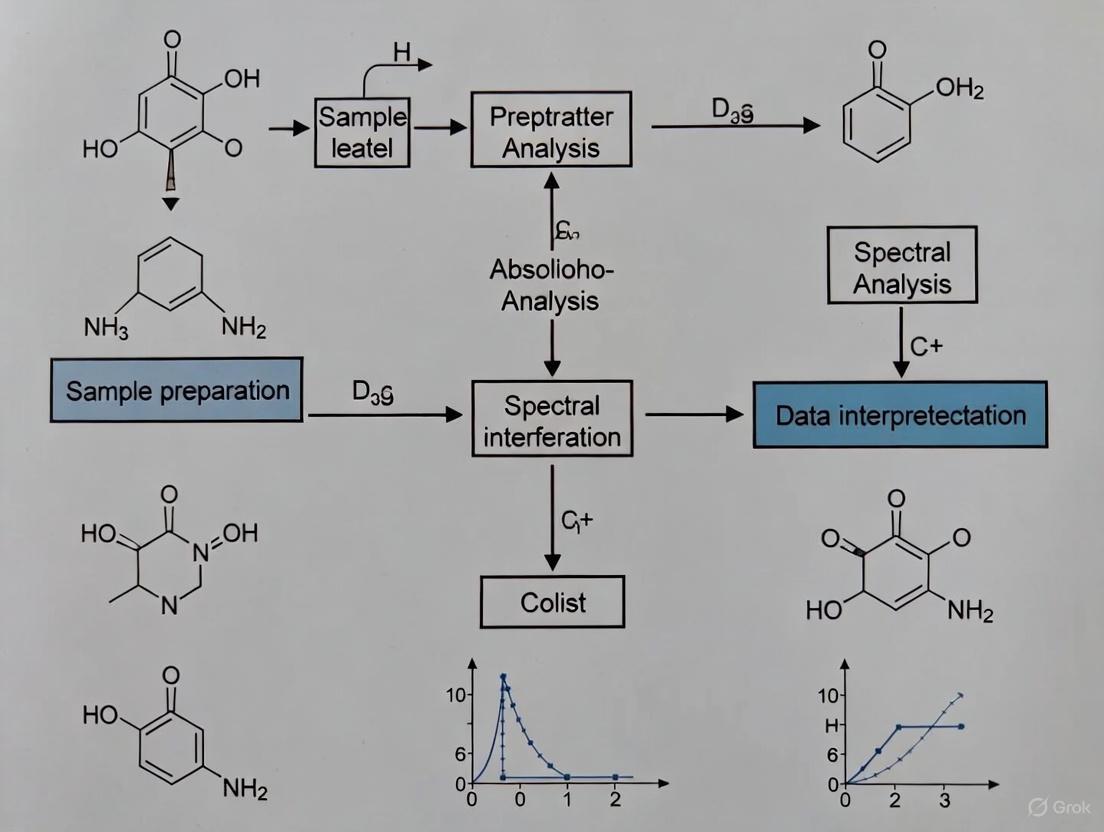

Workflow Diagram

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a synthetic sample containing 0.5 μg/L of Ruthenium (Ru), along with other analytes of interest like Rhodium (Rh) and Palladium (Pd).

- Dissolve these analytes in a matrix that simulates the real sample, containing 80 mg/L Nickel (Ni), 40 mg/L Copper (Cu), and 1% Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) [4].

ICP-MS Instrument Setup:

- Use an ICP-MS system equipped with a Dynamic Reaction Cell (DRC), such as an ELAN DRC II.

- Install standard sample introduction components: a concentric nebulizer, a cyclonic spray chamber, and appropriate pump tubing.

- Set the plasma power and nebulizer gas flow according to the manufacturer's recommendations for optimal sensitivity and stability. The specific conditions used in the referenced study are summarized in Table 3 below [4].

DRC Optimization:

- Introduce Ammonia (NH₃) as the reaction gas into the DRC.

- For the isotope ¹⁰¹Ru, optimize the NH₃ gas flow rate by monitoring three parameters simultaneously: the signal from the blank matrix (green plot), the signal from the matrix plus the 0.5 μg/L Ru analyte (blue plot), and the calculated Background Equivalent Concentration (BEC) (red plot).

- The goal is to find the flow rate (typically around 1.0 mL/min) where the BEC is minimized. This point represents the best compromise between maximizing analyte signal and minimizing the background interference, as shown in the optimization plot for Ru [4].

Calibration and Analysis:

- Establish a calibration curve using a series of standards that contain the analytes (Ru, Rh, Pd) and are matrix-matched with the same concentrations of Ni, Cu, and HCl as the samples.

- Run the unknown samples under these optimized DRC conditions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for DRC-ICP-MS Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonia (NH₃) Gas | Highly reactive gas used in the DRC to undergo ion-molecule reactions with polyatomic interferences, converting them into harmless species [4]. | Used to eliminate interferences from Cu-, Ni-, and Cl- based polyatomics on ¹⁰¹Ru, ¹⁰³Rh, and ¹⁰⁵Pd [4]. |

| Methyl Fluoride (CH₃F) Gas | Alternative reaction gas used to break up refractory oxide interferences, which are common in digested rock matrices [4]. | Can be used to dissociate ⁹⁰Zr¹⁶O⁺ to enable measurement of ¹⁰⁶Pd⁺ [4]. |

| High-Purity Acids | Used for sample digestion and dilution. High purity is essential to minimize the introduction of new elemental interferences and background noise. | Use of 1% HCl for the copper-nickel-chloride matrix [4]. |

| Certified Single-Element Standards | Used for the preparation of accurate calibration standards and for determining instrumental correction coefficients. | Used to prepare the 0.5 μg/L Ru, Rh, Pd stock in the synthetic sample [4]. |

| Matrix-Matched Calibration Standards | Calibration standards that contain a similar composition of major matrix elements as the samples, which helps to account for signal suppression/enhancement and some interferences. | Standards contain the same 80 mg/L Ni, 40 mg/L Cu in 1% HCl as the samples [4]. |

| Peristaltic Pump Tubing | Delivers the liquid sample at a consistent and stable flow rate to the nebulizer. | Critical for maintaining a stable signal during DRC optimization and analysis [4]. |

Spectral interference is a significant challenge in spectrophotometric analysis, adversely affecting the accuracy, precision, and reliability of results. In pharmaceutical research and drug development, where precise quantification of compounds is crucial, understanding and mitigating these interferences is paramount. This guide addresses common interference sources—sample matrix, solvents, and radicals—providing researchers with practical troubleshooting methodologies to enhance analytical outcomes.

Troubleshooting Guides

Sample Matrix Interferences

Problem: Inaccurate absorbance readings due to components in the sample's matrix other than the analyte.

- Manifestation: Elevated baseline, unexpected peaks, or suppressed analyte signal.

- Common Causes: Excipients in pharmaceutical formulations (e.g., preservatives like benzalkonium chloride), proteins in biological samples, or inorganic salts in environmental samples [7] [4].

Solutions:

- Background Correction: Use instrumental background correction techniques.

- Deuterium Lamp (D₂) Background Correction: Measures background absorption with a continuum source and subtracts it from the total absorbance measured with the line source (e.g., hollow cathode lamp) [8].

- Zeeman Effect Background Correction: Applies a magnetic field to the atomizer to split absorption lines, allowing selective measurement of background absorption [8].

- Matrix Matching: Prepare calibration standards in a matrix that closely resembles the sample's composition to ensure the background absorption is consistent between samples and standards [8].

- Standard Addition Method: Add known quantities of the analyte to the sample to correct for matrix-induced suppression or enhancement effects [4].

- Advanced Instrumentation: For complex matrices like geological samples, use Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) with a Dynamic Reaction Cell (DRC). A reaction gas like ammonia (NH₃) can be introduced to eliminate polyatomic interferences by converting them into harmless species [4].

Solvent Interferences

Problem: Solvent properties alter the analyte's spectral characteristics or introduce absorbing species.

- Manifestation: Shifts in absorption/emission maxima, changes in spectral bandwidth, or elevated background, particularly at shorter wavelengths (e.g., below 300 nm) [8] [9].

Solutions:

- Solvent Selection: Choose a solvent that is transparent in the spectral region of interest. For UV-Vis studies, use UV-grade solvents. Prioritize green solvents like water or ethanol to minimize environmental impact and toxicity [7] [10].

- Use of Buffers and pH Control: Maintain a constant pH using appropriate buffers, as the absorption spectrum of ionizable analytes can be highly pH-dependent.

- Characterize Solvent Effects: Understand how solvent polarity and hydrogen-bonding capabilities affect the analysis. For instance, the photoconversion rate of Diclofenac increases with solvent polarizability and H-bond donor capability but decreases with H-bond acceptor capability [9].

- Baseline Correction: Always run a blank containing the same solvent and all reagents except the analyte, and use it to zero the instrument.

Interferences from Radicals and Reactive Species

Problem: Unstable radicals or reactive species generated in the sample can lead to side reactions, decomposition of the analyte, or formation of interfering compounds.

- Manifestation: Unstable readings, unexpected reaction products, or a gradual change in absorbance over time.

Solutions:

- Control Reaction Conditions: Use inert atmospheres (e.g., nitrogen or argon purging) to prevent oxidation of radicals by atmospheric oxygen.

- Temperature Regulation: Perform analyses at controlled, often lower, temperatures to slow down unwanted radical reactions [9].

- Add Stabilizers or Scavengers: Introduce specific chemical agents that can stabilize reactive species or scavenge interfering radicals without affecting the analyte.

- Kinetic Studies: Monitor the reaction progress over time using techniques like fluorescence spectroscopy to understand the kinetics and identify stable measurement windows [9].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main types of spectral interferences in atomic absorption spectroscopy? The primary types are spectral and matrix interferences. Spectral interferences occur when an analyte's absorption line overlaps with an absorption line or band from an interferent or due to scattering by particulates. Matrix interferences arise from sample components that affect atomization efficiency or physically impede the analysis [8].

Q2: How can I quickly check if my solvent is suitable for UV-Vis analysis? Perform a baseline scan with the solvent in the cuvette against air or water (for aqueous solvents). The solvent should have low absorbance (preferably <1.0) across your wavelength range of interest, especially at lower UV wavelengths [11] [12].

Q3: Our lab analyzes combination drugs with overlapping UV spectra. What is a green approach to resolve this without chromatography? Employ green chemometric methods. Use water or water-ethanol mixtures as a solvent and apply multivariate calibration models like Partial Least Squares (PLS) or Multivariate Curve Resolution-Alternating Least Squares (MCR-ALS). These methods can accurately quantify individual components in a mixture without prior separation, aligning with Green Analytical Chemistry principles [13] [10].

Q4: Why are my absorbance readings drifting unpredictably during a kinetic study? Drift can be caused by instrumental issues or chemical instability. First, ensure the spectrophotometer lamp is warmed up and stable. Check for dirty cuvettes or debris in the light path. Chemically, the drift may indicate photodegradation of the analyte or interference from reactive species. Controlling temperature and using stabilizers can mitigate this [9] [11].

Q5: What is the optimal absorbance range for precise quantitative analysis? For most spectrophotometers, the optimal range for accurate concentration measurement is between 0.1 and 2.0 absorbance units. Absorbance below 0.1 may suffer from low signal-to-noise, while readings above 2.0 may lead to detector saturation and deviations from the Beer-Lambert law [12].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Interferences

Protocol 1: Resolving Spectral Overlap in a Ternary Pharmaceutical Mixture

This protocol is adapted from a green method for analyzing alcaftadine (ALF), ketorolac (KTC), and benzalkonium chloride (BZC) in eye drops [7].

- Instrument Setup: Use a dual-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., Shimadzu UV-1800) with 1 cm quartz cells. Set parameters: bandwidth 1 nm, scanning speed 2800 nm/min, wavelength range 200-400 nm.

- Green Solvent Preparation: Use ultrapure water as the sole solvent for all solutions.

- Standard Solutions: Prepare individual stock solutions of ALF, KTC, and BZC at 1.0 mg/mL in water. Further dilute to working solutions as needed.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the pharmaceutical formulation (eye drops) with water to a suitable volume.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Record the zero-order absorption spectra of samples and standards.

- For quantification, apply one of these direct, non-separation techniques:

- Absorbance Resolution Method: Use the extension of KTC's spectrum beyond that of ALF.

- Factorized Zero-Order Method: Leverage unique spectral properties of the mixture.

- Validation: Validate the method for linearity, accuracy, and precision as per ICH guidelines.

Protocol 2: Using a Dynamic Reaction Cell (DRC) in ICP-MS for Complex Matrices

This protocol is for determining precious metals in a complex copper-nickel-chloride geological matrix [4].

- Sample Digestion: Digest the geological sample using concentrated HCl/HNO₃ (aqua regia) and hydrofluoric acid (HF) in appropriate labware.

- Instrument Setup: Use an ICP-MS system equipped with a DRC (e.g., PerkinElmer ELAN DRC II).

- Sampling Conditions: Use a Micromist nebulizer, cyclonic spray chamber, platinum sampler and skimmer cones, and set RF power to 1550 W.

- DRC Optimization:

- Introduce ammonia (NH₃) as the reaction gas.

- Optimize the gas flow rate (e.g., ~1.0 mL/min) to maximize the signal-to-background ratio for analytes like ¹⁰¹Ru, ¹⁰³Rh, and ¹⁰⁵Pd.

- The NH₃ gas reacts with polyatomic interferences (e.g., ArCu⁺, ClO⁺), converting them into non-interfering species, while the analyte ions pass through for detection.

- Analysis: Measure the samples and standards, using the DRC mode for interfered elements and standard mode for others.

Interference Mitigation Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step process for identifying and addressing the sources of interference discussed in this guide.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the interference mitigation strategies discussed.

| Reagent/Material | Function in Interference Mitigation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonia (NH₃) Reaction Gas | Eliminates polyatomic interferences in ICP-MS via ion-molecule reactions in a DRC [4]. | Determination of Ru, Rh, Pd in copper-nickel geological matrices [4]. |

| Ultrapure Water | A green, non-toxic solvent with low UV cutoff, minimizes environmental impact and solvent interference [7] [10]. | Primary solvent for analyzing alcaftadine and ketorolac in eye drops [7]. |

| Deuterium (D₂) Lamp | A continuum source used for background correction in AAS and UV-Vis, correcting for broad-band molecular absorption [8]. | Correcting for background absorption from flame products or matrix components [8]. |

| Methyl Fluoride (CH₃F) Gas | Reaction gas in ICP-MS DRC to break up oxide-based interferences from refractory elements [4]. | Enabling accurate determination of Palladium in the presence of Zirconium oxide interferences [4]. |

| Chemometric Software | Resolves severely overlapping spectra mathematically, avoiding toxic solvents and separation steps [13] [10]. | Simultaneous quantification of meloxicam and rizatriptan in combined tablets [10]. |

A Technical Support Center for Spectrophotometric Analysis

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers identify and mitigate spectral interferences, which are a major source of false positives and false negatives in analytical data.

Understanding False Positives and False Negatives

In analytical chemistry, a false positive occurs when a test incorrectly indicates the presence of an analyte (a Type I error). A false negative occurs when a test incorrectly indicates the absence of an analyte (a Type II error) [14] [15] [16].

The following table outlines how these errors relate to spectral interference.

| Term | Definition | Relationship to Spectral Interference |

|---|---|---|

| False Positive | A result that incorrectly indicates the presence of an analyte [16]. | Reported analyte concentration is higher than the true value. Often caused by an interfering species whose signal adds to the analyte's signal [5]. |

| True Positive | A correct result that confirms the presence of an analyte when it is actually present. | The measured signal originates solely from the analyte, with interference properly corrected. |

| False Negative | A result that incorrectly indicates the absence of an analyte [16]. | Reported analyte concentration is lower than the true value. Can be caused by background correction errors that subtract a portion of the analyte signal [3]. |

| True Negative | A correct result that confirms the absence of an analyte when it is actually not present. | The instrument correctly identifies that no analyte signal exists above the detection limit. |

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process and potential error pathways in analytical measurement.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Spectral Interference

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is spectral interference, and when does it occur? Spectral interference, or spectral overlap, occurs when a species in the sample matrix (not the analyte) absorbs or emits radiation at a wavelength that is too close to the measurement line of the analyte [3] [5] [2]. This is common in atomic spectroscopy when the analyte's absorption line overlaps with an interferent's absorption line or band, or when molecular species in the sample's matrix form and produce broad absorption bands or scatter source radiation [2].

Q2: How can spectral interference lead to a false positive? A false positive can occur when the signal from an interfering species is mistakenly attributed to the analyte, inflating the final result [5]. For example, in a drug bridging immunoassay, the presence of soluble multimeric targets can create a false positive signal, leading to the incorrect conclusion that an anti-drug antibody is present [17].

Q3: How can spectral interference lead to a false negative? A false negative can occur during background correction. If the algorithm used to estimate and subtract the background radiation is inaccurate, it can inadvertently subtract a portion of the analyte's peak signal, leading to an under-reporting of the analyte's true concentration [3].

Q4: What is the simplest way to avoid spectral interference? The most straightforward strategy is avoidance by selecting an alternative analytical line for your analyte that is free from known interferents present in your sample matrix [3]. Modern simultaneous ICP-OES instruments make this particularly feasible.

Q5: My instrument only has one suitable wavelength. How can I correct for interference? If avoidance is not possible, effective correction strategies exist.

- Background Correction: Instruments can measure the background signal on one or both sides of the analyte peak and subtract it [3] [2]. The correction method (flat, sloping, or curved) must match the actual background shape for accuracy [3].

- Mathematical Correction: For a known, direct spectral overlap, you can measure the concentration of the interfering species and apply a pre-determined correction factor to subtract its contribution from the combined signal [3].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigation

Protocol 1: Background Correction with Point Selection

This method is suitable for flat or linearly sloping backgrounds [3].

- Analyte Measurement: Measure the net intensity at the analyte's peak wavelength.

- Background Point Selection: Select one or two background correction points (wavelengths) near the analyte peak. For a sloping background, ensure points are equidistant from the peak center [3].

- Averaging: Average the intensity values from the background points.

- Subtraction: Subtract the average background intensity from the net peak intensity to obtain the corrected analyte signal.

Protocol 2: Acid Dissociation for Target Interference in Immunoassays

This protocol is effective for minimizing false positives caused by soluble dimeric targets in bridging anti-drug antibody (ADA) assays [17].

- Sample Treatment: Mix the sample (e.g., plasma or serum) with an optimized concentration of a strong acid, such as hydrochloric acid (HCl). This disrupts the non-covalent interactions stabilizing target complexes [17].

- Incubation: Allow the acidified sample to incubate for a defined period to ensure complete dissociation.

- Neutralization: Add a neutralization buffer to return the sample to a pH compatible with the subsequent immunoassay steps. This prevents denaturation of the assay reagents [17].

- Analysis: Proceed with the standard bridging ELISA or ECL assay protocol. The acid treatment step significantly reduces target interference without the need for complex immunodepletion [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

The following table lists essential items used in the featured experiments and their functions.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Holmium Oxide Solution/Filters | Used to verify the wavelength accuracy of a spectrophotometer due to its sharp and well-characterized absorption bands [18]. |

| Deuterium (D₂) Lamp | A continuum source used for background correction (e.g., D₂ background correction in AAS). It corrects for broad-band molecular absorption and light scattering [2]. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | A strong acid used in sample pre-treatment to dissociate non-covalent complexes (like soluble multimeric targets) that cause false positives in immunoassays [17]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Standards with known analyte concentrations and a well-defined matrix. Used for method validation and to check for interference by ensuring accuracy in a matched matrix [3]. |

| Neutral Density Filters / Solid Attenuators | Used to check the photometric linearity of an instrument across a range of absorbance values, helping to identify instrumental drift or non-linearity as an error source [18]. |

Visualizing the Interference Mitigation Workflow

The following diagram provides a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing spectral interference in your research.

FAQs: Understanding Phosphate Interference

Q1: What is the primary mechanism of phosphate-induced spectral interference in AAS? Phosphate matrices primarily cause spectral interference by forming stable phosphate salts with the target metal analytes in the atomizer (flame or graphite furnace). These stable compounds have higher vaporization and dissociation energies, preventing the metal atoms from fully atomizing into the ground state atoms required for measurement. This results in a suppressed or altered absorption signal [19].

Q2: Which elements are most susceptible to phosphate interference? Research indicates that elements like Arsenic (As), Antimony (Sb), Selenium (Se), and Tellurium (Te) are particularly prone to spectral interferences when analyzed in phosphate matrices using electrothermal AAS [19].

Q3: How does spectral broadening affect AAS measurements in complex matrices? Spectral broadening, caused by mechanisms like Doppler, Stark, and pressure broadening, can convolve the absorption profile of the analyte. This broadening may cause the analytical line to overlap with absorption lines from other elements or molecules in the matrix (e.g., phosphorus species), leading to inaccurate concentration readings. While it generally introduces errors, the broadening effect can also be used to glean information about the plasma conditions [20].

Q4: What is the difference between spectral and non-spectral interferences?

- Spectral Interferences occur when a species in the sample absorbs light at or very close to the same wavelength as the analyte. This can be due to direct overlap with another atomic line or from molecular absorption by matrix components.

- Non-Spectral Interferences (or matrix effects) affect the atomization efficiency of the analyte. Phosphate interference often falls into this category, as phosphates can alter the volatilization and atomization rates of metals.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Diagnosing Phosphate Interference

Observed Symptom: Consistently low recovery of the analyte, especially when using standard calibration curves prepared in simple acid matrices.

Diagnostic Steps:

- Check for Signal Suppression: Compare the signal of a standard solution with the signal of the standard spiked into the sample matrix. A significant suppression in the spiked sample indicates a likely matrix effect.

- Inspect Atomization Profiles: In Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS), observe the temporal atomization profile. A shift to a higher temperature or a distorted peak shape suggests the analyte is being retained longer by the matrix.

- Use a Different Technique: If available, confirm results with an alternative technique like ICP-MS, which is less susceptible to some of these interferences.

Guide 2: Resolving Hollow Cathode Lamp (HCL) Performance Issues

A poorly performing light source can exacerbate interference problems.

Symptom: Low energy, noisy signal, poor baseline stability, or drifting calibration [21].

Prevention and Troubleshooting:

- Warm-up Time: Always allow the HCL to warm up for the manufacturer's recommended time (typically 10-30 minutes) before use.

- Proper Current: Operate the lamp at the recommended current. Excessive current can shorten lamp life and cause self-absorption.

- Cleanliness: Ensure the lamp window is clean. Fingerprints or dust can scatter light.

- Replacement: HCLs have a finite lifespan. Replace the lamp if energy levels remain low after adequate warm-up or if spectral line purity degrades [21].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating Interference

Protocol 1: Method of Standard Additions

This is the most robust method for compensating for matrix effects when analyzing samples with complex, variable phosphate backgrounds.

Procedure:

- Prepare Samples:

- Divide the sample solution into at least four equal aliquots.

- To all but one aliquot, add known and increasing volumes of a standard analyte solution.

- Dilute all aliquots to the same final volume.

- Measurement: Measure the absorbance of each solution via AAS.

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured absorbance against the concentration of the added analyte. The best-fit line is extrapolated to the x-axis. The absolute value of the x-intercept gives the concentration of the analyte in the original sample. This corrects for multiplicative matrix effects.

Protocol 2: Use of Chemical Modifiers in GFAAS

Chemical modifiers are added to the sample in the graphite tube to stabilize the analyte or modify the matrix during the pyrolysis stage.

Procedure for Analyzing Metals in Phosphate Matrices:

- Select Modifier: Palladium (Pd) salts, often mixed with Magnesium (Mg) nitrate, are universal modifiers. For specific elements, consult literature (e.g., Ni modifier for Se and As).

- Injection Sequence: Inject the chemical modifier solution into the graphite tube, typically followed by the sample solution. Modern autosamplers can do this automatically.

- Optimize Temperature Program: Adjust the pyrolysis (ashing) temperature to be high enough to remove the phosphate matrix (as volatile PxOy species) without volatilizing the analyte, which is now stabilized by the modifier. This separates the matrix removal from the analyte atomization in time.

Protocol 3: Background Correction

This technique corrects for broadband molecular absorption.

Types of Correction:

- Deuterium Lamp Background Correction: A deuterium continuum source is used to measure broadband absorption, which is then subtracted from the total absorption measured by the HCL.

- Zeeman Effect Background Correction: A magnetic field is applied to split the atomic energy levels, allowing for highly accurate correction of structured and unstructured background adjacent to the analytical line. This is particularly effective for complex matrices [22].

Quantitative Data on Interference Effects

Table 1: Impact of Phosphate Matrix on Selected Metal Analytes in Electrothermal AAS

| Analyte | Wavelength (nm) | Observed Interference Effect | Primary Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | 193.7 | Signal suppression due to formation of stable arsenic phosphates | Pd/Mg chemical modifier; Zeeman background correction [19] |

| Selenium (Se) | 196.0 | Signal suppression and shifted atomization profiles | Ni modifier; Method of Standard Additions [19] |

| Antimony (Sb) | 217.6 | Signal suppression in phosphate-rich environments | Platform atomization; Oxidizing acid addition [19] |

Table 2: Comparison of AAS Interference Correction Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Method of Standard Additions | Builds calibration in the sample matrix | Directly compensates for matrix effects | Time-consuming; not ideal for high-throughput labs |

| Chemical Modification | Modifies thermal stability of analyte/matrix | Highly effective for volatile elements; allows higher pyrolysis temps | Requires optimization; adds reagent cost |

| Zeeman Background Correction | Splits spectral line with magnetic field | Corrects for structured background near the analytical line | Higher instrument cost; can cause sensitivity loss for some elements |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Managing Phosphate Interference

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Palladium Nitrate | Universal chemical modifier; forms thermally stable alloys with analytes | High-purity grade is essential to avoid contaminant background. |

| Magnesium Nitrate | Often used with Pd to enhance its modifier effect. | Helps to form a more homogeneous carbon matrix in the graphite tube. |

| Nitric Acid (High Purity) | Primary digesting and diluting acid for samples. | Minimizes chloride interference, which can combine with phosphate effects. |

| High-Purity Argon Gas | Inert gas for graphite furnace; purges volatilized matrix. | Purity is critical to prevent tube oxidation and formation of interfering species. |

| Platform Graphite Tubes | Provide an isothermal environment for atomization. | Improves accuracy by atomizing the analyte into a hotter, more uniform gas. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

Diagram: Pathway of Phosphate Interference and Mitigation

Proven Correction Techniques and Their Application in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Troubleshooting Guides

Deuterium Arc Background Correction

Problem: Over- or Under-correction of Background Signal

- Cause: This occurs when the background absorbance is not constant over the spectral bandwidth isolated by the monochromator. The D₂ lamp measures an average background across a wider range, which may not match the background at the specific analytical line [23] [8].

- Solution: Verify the nature of the background. This method is best for broad, continuous background. For structured background (sharp peaks), switch to Zeeman or Smith-Hieftje correction if available. Ensuring the D₂ lamp and HCL beams are perfectly aligned is also crucial.

Problem: Noisy Baseline After Correction

- Cause: Instability or aging of the Deuterium lamp can lead to intensity fluctuations [23].

- Solution: Check the lifetime of the D₂ lamp and replace it if necessary. Allow the instrument and lamp to warm up sufficiently to stabilize. Increase the measurement integration time to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Zeeman Effect Background Correction

Problem: Signal Loss or Sensitivity Reduction

- Cause: In the transverse magnetic field configuration, the π component (which is at the original wavelength) is absorbed by the analyte, while the σ± components are shifted away. When the magnetic field is on, the polarizer is set to measure only the background using the σ± components. If the background is not perfectly flat, this can lead to a sensitivity loss or inaccurate correction [23] [8].

- Solution: This is an inherent characteristic of some Zeeman system configurations. Consult your instrument manual to understand the specific configuration (transverse/longitudinal). For low-concentration analytes, compare results with D₂ correction to assess sensitivity loss.

Problem: Inaccurate Correction with Strong Background

- Cause: While Zeeman correction is very powerful, extremely high background signals can still pose challenges, particularly if they exhibit polarization properties [23].

- Solution: Dilute the sample if possible. For graphite furnace applications, optimize the pyrolysis and ashing steps to remove more of the matrix components before atomization.

Smith-Hieftje Background Correction

Problem: Severe Loss of Sensitivity

- Cause: The high-current pulse used to create self-reversal may not be fully effective for all elements. The dip in the center of the emission line might not be complete, meaning the analyte still absorbs some radiation during the "background" measurement phase, leading to signal subtraction and reduced sensitivity [23].

- Solution: Confirm that the specific HCL is designed for Smith-Hieftje operation. This loss is method-dependent for certain elements. If sensitivity is critical, compare performance with Zeeman correction.

Problem: HCL Fails or Has Short Lifetime

- Cause: The repeated high-current pulses used to induce self-reversal put significant stress on the hollow cathode lamp [23].

- Solution: Use only lamps specified by the manufacturer as compatible with this correction method. Avoid excessive pulse parameters and ensure the lamp cooling system is functioning properly.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between these background correction methods? The core difference lies in how they discriminate between the specific atomic absorption and non-specific background. The Deuterium Arc uses a second light source to measure background. The Zeeman Effect uses a magnetic field to split the absorption line. The Smith-Hieftje method uses a high-current pulse to broaden the emission line from the primary source [23] [8].

2. Which correction method is the most effective? There is no single "best" method; the choice is application-dependent. Zeeman Effect correction is often considered the most robust for complex matrices, especially in graphite furnace AAS, as it can correct for structured background. Deuterium Arc is simple and effective for broad, continuous background. Smith-Hieftje can be a good compromise but may suffer from sensitivity loss for some elements [23].

3. Can these methods correct for all types of interference? No. These methods are designed to correct for spectral interferences, specifically non-specific absorption and light scattering from molecular species or particles. They do not correct for chemical interferences (e.g., formation of refractory compounds) or matrix effects that alter transport or atomization efficiency [8].

4. Why is my absorbance reading still incorrect after applying background correction? Background correction systems can fail if the background is too intense or has a complex, structured nature that the chosen method cannot fully resolve. Other sources of error, such as contamination from leached chemicals from plasticware, can also cause unexpected UV absorption and interfere with measurements [24].

5. Is High-Resolution Continuum Source AAS (HR-CS AAS) a form of background correction? HR-CS AAS represents a modern, advanced approach. Instead of using a separate physical principle for correction, it uses a high-resolution CCD array detector to view the entire spectrum around the analytical line. This allows direct visualization and software-based subtraction of the background, making it highly effective for structured backgrounds [23].

Comparison of Background Correction Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three main background correction techniques.

| Feature | Deuterium Arc | Zeeman Effect | Smith-Hieftje |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Second continuum source (D₂ lamp) [23] [8] | Magnetic splitting of absorption lines [23] [8] | Self-reversal of HCL emission via high-current pulse [23] |

| Background Measured At | Average over spectral bandwidth [8] | Same wavelength as analytical line [23] [8] | Same wavelength as analytical line [23] |

| Effectiveness on Structured Background | Poor [23] [8] | Excellent [23] | Poor [23] |

| Typical Sensitivity | No loss [23] | Can be reduced [23] | Can be significantly reduced [23] |

| Best For | Simple matrices, broad background [23] | Complex matrices, furnace AAS, structured background [23] | Applications where sensitivity loss is acceptable [23] |

Experimental Workflow for Method Selection

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and validating a background correction method based on your sample and instrument capabilities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Materials

The table below lists essential items used in spectrophotometric analysis, particularly in the context of pharmaceutical analysis as described in the search results.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Ultra-purified Water | Used as a green solvent for preparing standard and sample solutions, minimizing environmental impact and toxic waste [7] [10]. |

| Standard Reference Materials | High-purity certified compounds (e.g., Alcaftadine, Ketorolac) used to prepare calibration curves for quantitative analysis [7] [13]. |

| Quartz Cuvettes | Hold liquid samples for measurement. They are transparent across UV and visible wavelengths and have a precise pathlength (typically 1 cm) critical for the Beer-Lambert law [7] [10] [13]. |

| Microcentrifuge Tubes (High-Quality) | For sample storage and manipulation. Low-quality tubes can leach UV-absorbing chemicals, causing significant interference, especially at wavelengths below 300 nm [24]. |

| Matrix Modifiers (for AAS) | Chemicals added to a sample in graphite furnace AAS to stabilize the analyte or modify the matrix, reducing volatility and chemical interferences during the heating stages. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary goal of using mathematical resolution methods in spectrophotometry? These methods aim to enable the simultaneous quantification of multiple drugs in a mixture without requiring physical separation steps. They achieve this by mathematically resolving the significant spectral overlap that often exists between compounds, which is a common challenge in the analysis of pharmaceutical formulations [7] [25] [26].

2. How does the Factorized Zero-Order Method (FZM) work?

The FZM is an advanced technique that recovers the pure zero-order spectrum (D⁰) of a target drug from a mixture. It calculates a single response value for the target analyte that is unaffected by other components. This involves dividing the D⁰ spectrum of a pure standard of the target drug by its absorbance value at a specific, pre-determined wavelength (λs). This resulting "factorized spectrum" is then multiplied by the absorbance of the mixture at that same wavelength to extract the target drug's D⁰ contribution [27].

3. My samples include a preservative like benzalkonium chloride. Can these methods handle this? Yes. A key application of these methods is to account for and negate the spectral interference from common formulation preservatives. For instance, methods have been successfully developed to determine active ingredients like alcaftadine and ketorolac tromethamine in the presence of benzalkonium chloride, which has strong UV absorbance, without prior separation [7].

4. What is a major advantage of derivative spectrophotometry over zero-order? Derivative spectrophotometry helps differentiate between very closely spaced or overlapping absorbance peaks. The first derivative can eliminate baseline shifts, and the technique is particularly useful for overcoming the effects of scattering from unidentified interfering compounds, leading to more accurate quantitative analysis [28].

5. How do I assess the environmental impact of my analytical method? The greenness of spectrophotometric methods can be quantitatively evaluated using modern metric tools such as the Analytical Greenness (AGREE) metric, the Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), and the Analytical Eco-Scale. These tools assess factors like solvent toxicity, energy consumption, and waste production, helping you align your methods with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles [7] [29] [26].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inaccurate Results in Multicomponent Analysis Due to Spectral Overlap

Problem: When analyzing a binary or ternary mixture, the absorption spectra of the components heavily overlap, making it impossible to quantify each one accurately using direct absorbance measurement at a single wavelength [25].

Solution: Employ mathematical resolution techniques tailored to your mixture's spectral characteristics.

- Applicable Methods:

- Absorbance Resolution & Extended Absorbance Difference: Use these when one component's spectrum is broader than the other's or when you can find two wavelengths where the interferent shows equal absorbance [27].

- Ratio Difference Method: Ideal for complete spectral overlap. You will divide the mixture spectrum by the spectrum of one of the pure components (the divisor) to get a ratio spectrum. The difference in amplitudes at two carefully selected wavelengths in this ratio spectrum is proportional to the concentration of the other component [25] [26].

- Derivative Methods: Use first or higher-order derivatives to resolve overlapping peaks and eliminate baseline interferences. The analyte can be quantified at a wavelength where the derivative of the interferent is zero (a zero-crossing point) [30] [25] [28].

Experimental Protocol (Ratio Difference Method for a Binary Mixture) [25] [26]:

- Preparation: Scan and store the

D⁰spectra of your mixed sample and standard solutions of the individual pure components (Drug A and Drug B). - Divisor Selection: Choose an appropriate concentration of a standard Drug B spectrum to use as a divisor.

- Obtain Ratio Spectra: Divide the stored

D⁰spectra of the mixture and all Drug A standard solutions by the divisor spectrum of Drug B. - Measurement: In the ratio spectra, measure the amplitudes at two selected wavelengths (P1 and P2). The difference in amplitudes (ΔP) is calculated.

- Quantification: Construct a calibration curve by plotting the ΔP values of the Drug A standards against their known concentrations. Use this curve to determine the concentration of Drug A in your mixture.

- Repeat: To find the concentration of Drug B, repeat the process using a standard Drug A spectrum as the divisor.

Issue 2: Handling Complex Formulations with a Preservative

Problem: The pharmaceutical formulation contains active ingredients alongside a preservative (e.g., benzalkonium chloride), all of which contribute to the UV absorbance spectrum, creating a ternary mixture that is difficult to resolve [7].

Solution: Implement a Factorized Zero-Order Method (FZM) or related factorized response techniques, which can recover the pure spectrum of each active ingredient.

Experimental Protocol (Framework for Ternary Mixture with Preservative) [7]:

- Standard Solutions: Prepare separate stock and working standard solutions of all active ingredients and the preservative using a green solvent like water where possible.

- Laboratory-Prepared Mixtures: Accurately prepare several laboratory mixtures containing the actives and the preservative in different, known concentration ratios to simulate the market formulation and test method specificity.

- Spectral Manipulation:

- For each target active ingredient (e.g., Alcaftadine), use the corresponding pure standard.

- Apply the FZM principle: The

D⁰spectrum of the pure standard is divided by its absorbance at an iso-absorptive point or a selected wavelength (λs) to generate its factorized spectrum. - Multiply the factorized spectrum by the absorbance of the ternary mixture at that same λs. This recovers the

D⁰spectrum of the target active as it exists in the mixture.

- Quantification: The concentration of the active is then determined from this recovered spectrum using a pre-established calibration curve at its λmax.

Issue 3: Excessive Background Noise or Scattering in Samples

Problem: Physical interferences from suspended impurities or chemical interferences from a complex sample matrix cause background absorbance or scattering, leading to inaccurate, inflated absorbance readings [28] [8].

Solution:

- Physical Pre-treatment: If sample volume permits, filter or centrifuge the sample to remove suspended particulates [28].

- Derivative Spectroscopy: This is a highly effective mathematical correction. Converting the zero-order spectrum to its first or second derivative can eliminate baseline shifts and minimize the effects of background scattering and random noise [28].

- Three-Point Correction: For non-linear background, measure absorbance at the analytical wavelength and at two closely spaced wavelengths on either side of it. The background interference can be estimated by linear interpolation between the two side wavelengths and then subtracted from the reading at the analytical wavelength [28].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential materials and their functions in mathematical resolution methods.

| Material/Reagent | Function in the Experiment | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Drug Standards | Used to construct calibration curves and obtain reference spectra for spectral resolution techniques like divisor in ratio methods or factorized spectra. | Alcaftadine, Ketorolac Tromethamine, Remdesivir, Moxifloxacin [7] [26]. |

| Green Solvents (e.g., Water, Ethanol) | To dissolve samples and standards, aligning with Green Analytical Chemistry (GAC) principles by reducing toxicity and environmental impact. | Water as a sole solvent for Alcaftadine/Ketorolac analysis; Ethanol for Telmisartan/Chlorthalidone analysis [7] [29]. |

| UV-Transparent Cuvettes | Contain the sample solution for spectrophotometric measurement. Standard 1 cm pathlength quartz cells are typically used. | 1 cm quartz cells are specified in multiple experimental sections [7] [29] [25]. |

| Pharmaceutical Formulation Excipients | Inactive components (e.g., starch, cellulose, magnesium stearate) used in laboratory-made tablets to validate method accuracy and specificity in a simulated real-world matrix. | Maize starch, microcrystalline cellulose (Avicel), magnesium stearate, colloidal silica (Aerosil) [25]. |

| Preservative Standards (e.g., BZC) | Pure standard of the preservative to study and account for its spectral contribution, ensuring it does not interfere with the active ingredient quantification. | Benzalkonium Chloride (BZC) standard used to resolve its interference in eye drop analysis [7]. |

Table 2: Typical linearity ranges and wavelengths for different drug combinations and methods.

| Drug Combination (Example) | Analytical Method | Linearity Range (µg/mL) | Key Wavelengths (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alcaftadine (ALF) & Ketorolac (KTC) [7] | Direct Spectrophotometry, Absorbance Resolution, FZM | ALF: 1.0–14.0KTC: 3.0–30.0 | Resolving interference from Benzalkonium Chloride. |

| Paracetamol (PAR) & Meloxicam (MEL) [25] | Zero-Order & First-Order Derivative | MEL (Zero): 3–30PAR (1D): 2.5–30MEL (1D): 3–15 | MEL (Zero) at 361 nm;PAR (1D) trough at 262 nm;MEL (1D) peak at 342 nm. |

| Remdesivir (RDV) & Moxifloxacin (MFX) [26] | Ratio Difference (RD) | RDV: 1–15MFX: 1–10 | RDV (ΔP247-262);MFX (ΔP299-313). |

| Remdesivir (RDV) & Moxifloxacin (MFX) [26] | Ratio Derivative (1DD) | RDV: 1–15MFX: 1–10 | RDV at 250 nm;MFX at 290 nm. |

| Chlorphenoxamine HCl (CPX) & Caffeine (CAF) [27] | Factorized Zero-Order (FZM) & other Factorized Methods | CPX: 3–45CAF: 3–35 | Spectral recovery and quantification without need for zero-crossing points. |

Spectral interference is a fundamental challenge in spectrophotometric analysis, often compromising the accuracy of measurements in complex samples like pharmaceutical formulations and biological matrices. Within a broader thesis on reducing spectral interference, first-order derivative spectrophotometry emerges as a powerful signal processing technique. By transforming overlapping spectral features, it enables researchers to isolate and quantify analytes in the presence of interfering substances that absorb at similar wavelengths. This technical support center provides detailed guidance on implementing this method and interpreting the Area Under the Curve (AUC) metric, essential tools for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to enhance analytical precision.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does first-order derivative spectrophotometry fundamentally reduce spectral interference?

First-order derivative spectrophotometry converts a standard zero-order absorption spectrum (absorbance vs. wavelength) into its first derivative (rate of change of absorbance vs. wavelength). This transformation provides two key advantages for resolving spectral overlaps [31] [32]:

- Enhanced Resolution of Overlapping Peaks: Broad, featureless background absorption from excipients or matrix components often produces a near-constant or slowly sloping signal. The first derivative of such a signal is approximately zero, effectively eliminating its contribution. This allows the sharper, more structured peaks of the analyte to be distinguished in the derivative spectrum.

- Utilization of Zero-Crossing Points: In a mixture of two compounds, it is often possible to find a wavelength where the first derivative of one component is zero (a zero-crossing point), while the other component has a significant derivative value. By measuring the derivative amplitude at this specific wavelength, the second component can be quantified without interference from the first [33].

2. My derivative signal is noisy. What are the main causes and solutions?

Excessive noise in derivative signals is a common issue, as the differentiation process inherently amplifies high-frequency noise present in the original spectrum [32].

- Cause: The numerical calculation of derivatives (e.g.,

dA/dλ ≈ ΔA/Δλ) magnifies small, random fluctuations in the absorbance (A) values. - Solutions:

- Signal Smoothing: Apply smoothing algorithms, such as the Savitzky-Golay filter, which is designed to smooth data while preserving the shape and features of the spectrum. The Savitzky-Golay smooth can even be configured to compute derivatives directly, combining both steps into one optimized algorithm [32].

- Optimize Instrumental Parameters: Ensure your spectrophotometer has a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio. This can involve using a wider spectral bandwidth or longer integration times to improve the quality of the raw data before differentiation [18].

- Check for Stray Light: Stray light within the spectrophotometer can cause non-linear responses and contribute to noise and inaccurate derivatives; regular instrument calibration is crucial to minimize this [18].

3. When should I use AUC, and how do I interpret its value?

The Area Under the Curve (AUC), specifically from Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis, is a summary metric used to evaluate the performance of a binary classification test, such as determining if a sample is "positive" or "negative" for a condition based on a continuous diagnostic signal [34] [35].

- When to Use: AUC is used when you need to assess the overall ability of your analytical method or derived metric (e.g., a specific derivative amplitude) to discriminate between two defined groups. It is especially useful for comparing the performance of different methods or signals.

- Interpretation: The AUC value ranges from 0.5 to 1.0. The following table provides a standard interpretation guide [35]:

| AUC Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| 0.9 - 1.0 | Excellent discrimination |

| 0.8 - 0.9 | Considerable/good discrimination |

| 0.7 - 0.8 | Fair discrimination |

| 0.6 - 0.7 | Poor discrimination |

| 0.5 - 0.6 | Fail (no better than chance) |

4. Can I use derivative spectrophotometry for stability-indicating assays?

Yes, derivative spectrophotometry is highly valuable for stability-indicating assays. It allows for the direct determination of a drug in the presence of its degradation products, which often have overlapping UV spectra. By selecting a derivative wavelength where the degradation product has a zero-crossing point, the intact drug can be quantified without interference from its breakdown products [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Poor Specificity in Multicomponent Mixtures

Problem: Inability to accurately quantify the target analyte due to spectral overlap from excipients, co-formulated drugs, or matrix components.

Solution Steps:

- Record Zero-Order Spectra: Obtain the absorption spectra of the pure analyte and the potential interferent(s) across a relevant wavelength range [33].

- Generate First-Order Derivatives: Use your instrument's software to compute the first-derivative spectra of all components [33].

- Identify Zero-Crossing Wavelength: Carefully examine the first-derivative spectrum of the interferent to find a wavelength where its derivative value crosses zero (where the slope of its original spectrum is zero) [33].

- Validate the Wavelength: Confirm that at this zero-crossing wavelength, the analyte has a significant and measurable first-derivative amplitude.

- Construct Calibration Curve: Prepare standard solutions of the analyte and measure their first-derivative amplitudes at the selected zero-crossing wavelength. Plot these amplitudes against concentration to create a calibration curve [33].

- Quantify Unknowns: Measure the first-derivative amplitude of your unknown sample at the same wavelength and determine the concentration from the calibration curve.

Guide 2: Correcting for Baseline Drift and Background Interference

Problem: The baseline of the spectrum is sloped or curved due to scattering (e.g., from particulate matter) or broad background absorption, making accurate measurement of the analyte peak difficult.

Solution Steps:

- Understand the Derivative Property: Recall that the derivative of a constant background is zero. A linearly sloping background becomes a constant offset in the first derivative, and a curved background becomes a sloping line. This often simplifies the interference compared to the complex background in the zero-order spectrum [32].

- Select Appropriate Background Correction: In the derivative spectrum, the contribution of the broad background is transformed. The analytical signal can often be measured as the peak-to-trough amplitude of the derivative peak, which can effectively cancel out any remaining linear background offset [3] [32].

- Verify with a Blank: Always run a blank or matrix sample and process its derivative spectrum. This will show the residual derivative signal of the background, allowing you to confirm that your chosen measurement metric (e.g., amplitude at a specific wavelength) is free from interference.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantification of an Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) in the Presence of a Bioenhancer

This protocol is based on a published study for quantifying Saquinavir (SQV) in a eutectic mixture with Piperine (PIP) [33].

1. Goal: To develop and validate a first-order derivative UV-spectrophotometric method for the quantification of SQV in the presence of PIP.

2. Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Saquinavir (SQV) Mesylate | The Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) to be quantified. |

| Piperine (PIP) | Natural bioenhancer; acts as the potential spectral interferent. |

| Ethanol (70%) | Solvent used to prepare stock and standard solutions. |

| Volumetric Flasks | For accurate preparation and dilution of standard solutions. |

| Quartz Cuvettes (1 cm) | For holding samples in the UV-Vis spectrophotometer. |

3. Procedure:

- Standard Solution Preparation: Independently prepare stock solutions of SQV and PIP (e.g., 100 mg/L) in 70% ethanol. Dilute these to create a series of standard solutions for each (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/L) [33].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare the SQV-PIP eutectic mixture (EM) and dissolve it to make sample solutions at concentrations within the calibration range [33].

- Spectra Acquisition: Using a double-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer, record the zero-order absorption spectra of all standard and sample solutions from 220 nm to 270 nm [33].

- Derivative Processing: Use the instrument's software (e.g., UV-Probe, Origin Pro) to generate the first-order derivative spectra of all recorded zero-order spectra [33].

- Wavelength Selection: Examine the first-derivative spectrum of pure PIP. Identify the wavelength where its derivative value is zero (the zero-crossing point). In the referenced study, this was found at 245 nm [33].

- Calibration: Measure the first-derivative amplitude (dA/dλ) of the SQV standard solutions at 245 nm. Plot these amplitudes against the respective SQV concentrations to create a calibration curve [33].

- Validation: Assess the method's linearity, precision, accuracy, and specificity according to ICH guidelines. The method should be specific for at least a 1:4.3 SQV:PIP ratio [33].

4. Key Quantitative Parameters from the Model Study The following parameters were reported for the validated method [33]:

| Parameter | Value / Outcome |

|---|---|

| Linear Range | 0.5 - 100.0 mg/L |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.331 mg/L |

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | 0.468 mg/L |

| Specificity (SQV:PIP) | Confirmed up to 1:4.3 ratio |

| Critical Wavelength | 245 nm (PIP zero-crossing) |

Protocol 2: Using AUC to Validate a Diagnostic Spectral Signal

1. Goal: To use AUC analysis to evaluate the diagnostic power of a specific derivative signal amplitude in distinguishing between two sample groups (e.g., contaminated vs. pure API).

2. Procedure:

- Define Groups and Measure: Establish two clear sample groups (e.g., "Pure" and "Contaminated"). For each sample in both groups, apply your derivative method and record the diagnostic signal (e.g., derivative amplitude at a specific wavelength) [35].

- Perform ROC Analysis: Use statistical software to perform ROC analysis. The software will iterate through all possible cutoff values for your derivative signal, calculating the sensitivity and 1-specificity (False Positive Fraction) at each point [34] [35].

- Plot the ROC Curve: Graph the resulting values with Sensitivity (True Positive Fraction) on the Y-axis and 1-Specificity (False Positive Fraction) on the X-axis [34].

- Calculate and Interpret AUC: Calculate the Area Under this ROC Curve. Refer to the interpretation table in FAQ #3 to assess the discriminatory power of your signal. An AUC ≥ 0.8 is generally considered to have considerable clinical/analytical utility [35].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: How can using water as a solvent specifically reduce matrix effects in spectroscopic analysis? Using water as a solvent minimizes matrix effects by reducing the introduction of interfering organic compounds that can cause spectral overlap or affect the physicochemical environment during detection. A 2024 study on pain reliever analysis demonstrated that Green Analytical Chemistry-based UV spectrophotometric methods, which used water, successfully avoided the spectral interference commonly encountered with organic solvents, leading to a complete overlap of zero-order spectra for accurate determination of multiple drug components [36].

FAQ 2: What are the main challenges when switching from organic solvents to water, and how can they be overcome? The primary challenge is the low solubility of many non-polar natural products and pharmaceuticals in water [37]. Researchers have developed several methods to enhance water's solvent potential while maintaining its green credentials:

- pH Adjustment and Salts: Modifying pH or adding chaotropic salts can weaken water-water interactions, strengthening water-analyte interactions and facilitating solubilisation (the salting-in effect) [37].

- Cosolvents: Adding miscible, green cosolvents like ethanol or glycerol reduces water's polarity, making it more effective for non-polar compounds [37] [38].

- Surfactants and Micellar Catalysis: Designer surfactants can form nanoreactors (micelles) in water, creating a non-polar environment for reactions and extractions within the aqueous bulk. This can lead to higher local reactant concentrations and faster reaction rates [39].

FAQ 3: Are there specific analytical techniques where water has proven particularly effective as a green solvent? Yes, water has shown significant success in several techniques:

- UV-Spectrophotometry: As a direct solvent in methods like the Double Divisor Ratio Spectra Method (DDRSM) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) for analyzing complex drug mixtures [36].

- Liquid Chromatography (LC): Used as a major or sole component of the mobile phase in reversed-phase LC. This can be achieved by using specialized stationary phases or elevated column temperatures to enhance water's elution strength for non-polar compounds [38].

- Extraction Techniques: Water is central to green sample preparation methods like QuEChERS (Quick, Easy, Cheap, Effective, Rugged, and Safe), which use minimal solvents compared to traditional techniques [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Solubility of Analytes in Aqueous Solvents

Symptoms:

- Low analyte recovery rates.

- Poor peak shape or splitting in chromatography.

- Inconsistent or suppressed detector response.

Solutions:

- Employ pH Control:

- Principle: Adjusting the pH can ionize acidic or basic analytes, significantly increasing their solubility in water.

- Protocol: Prepare a series of aqueous buffers covering a relevant pH range (e.g., pH 2, 4, 7, 9, 10). Dissolve your analyte in each and check for solubility and stability. For example, the solubility of anthocyanin delphinidin is highest in acidic water (pH < 5) [37].

Utilize Green Cosolvents:

- Principle: Miscible solvents like ethanol or glycerol reduce the polarity of the aqueous mixture.

- Protocol:

- Prepare water-cosolvent mixtures (e.g., 10%, 30%, 50% v/v ethanol in water).

- Test analyte solubility in each mixture.

- Note that the optimal ratio for solubilisation may differ from the optimal ratio for extraction [37].

Apply Surfactant-Assisted "In-Water" Methods:

- Principle: Surfactants form micelles that act as nanoreactors, solubilizing non-polar compounds.

- Protocol: Add a small quantity (e.g., 1-2% w/w) of a green surfactant (e.g., TPGS-750-M) to pure water. Stir to form micelles before introducing the analyte [39].

Problem 2: Persistent Spectral Interference in Complex Matrices

Symptoms:

- Inaccurate quantification due to overlapping spectral peaks.

- High background signal or noise.

Solutions:

- Implement Mathematical Signal Resolution Techniques:

- Principle: Advanced algorithms can resolve overlapping signals without physical separation.

- Protocol (Double Divisor Ratio Spectra Method - DDRSM):

- Scan and store the spectra of the ternary mixture (A+B+C) and standard solutions of the individual components (A', B', C').

- To determine component A, divide the mixture spectra by a double divisor made from adding the standard spectra of B' and C'.

- Multiply the resulting ratio spectrum by the same double divisor (B'+C') to obtain the zero-order spectrum of A, which is used for quantification [36].

- Application: This method has been successfully applied for the analysis of Aceclofenac, Paracetamol, and Tramadol in bulk and tablet forms [36].

- Use Area Under the Curve (AUC) for Quantification:

- Principle: Measuring the integrated absorbance value over a selected wavelength range can mitigate the effects of slight spectral shifts or overlapping peaks.

- Protocol: Select a wavelength range (λ1 to λ2, e.g., ± 20 nm around a central wavelength) where the analyte has significant absorption. The area under the curve within this range is used for constructing the calibration curve and determining concentration, as it is less susceptible to minor interferences than single-wavelength measurements [36].

Problem 3: Matrix Effects in Detection (e.g., Signal Suppression/Enhancement)

Symptoms:

- Reduced (suppression) or increased (enhancement) detector response for the analyte in a sample compared to a pure standard.

- Inaccurate quantification despite good separation.

Solutions:

- The Internal Standard Method:

- Principle: A known amount of a standard compound, similar to the analyte, is added to every sample. Any variations in detector response affect both the analyte and internal standard similarly, allowing for accurate correction.

- Protocol:

- Select a suitable internal standard (e.g., a stable isotope-labeled version of your analyte).

- Spike a consistent amount into all calibration standards and unknown samples.

- For quantitation, plot the ratio of the analyte signal to the internal standard signal against the ratio of their concentrations [41].

- Assess the Matrix Effect:

- Principle: Proactively identify if matrix effects are present.

- Protocol (Infusion Experiment for LC-MS):

- Infuse a dilute solution of the analyte post-column into the MS detector.

- Inject a blank sample matrix extract onto the LC column.

- Observe the analyte signal across the chromatographic run time. A constant signal indicates no matrix effect, while a dip or rise indicates suppression or enhancement co-eluting with matrix components [41].

The following tables summarize key quantitative data from green chemistry methods utilizing water.

Table 1: Analytical Figures of Merit for a Green UV-Spectrophotometric Method (Ternary Drug Analysis)

| Parameter | Aceclofenac (ACE) | Paracetamol (PAR) | Tramadol (TRM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Range (µg/mL) | 8 – 12 | 22.75 – 35.75 | 2.62 – 4.12 |

| Analytical Technique | DDRSM & AUC [36] | DDRSM & AUC [36] | DDRSM & AUC [36] |

Table 2: Comparison of Green Solvent Enhancement Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Example Reagents/Tools | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH & Salts | Ionization control; salting-in effect [37] | HCl, NaOH, chaotropic salts | Solubilizing ionizable compounds (e.g., anthocyanins) |

| Cosolvents | Polarity reduction of aqueous phase [37] | Ethanol, Glycerol, PEG | Extracting medium-polarity natural products |

| Surfactants/Micelles | Formation of nanoreactors for non-polar reactions [39] | TPGS-750-M designer surfactants | Suzuki-Miyaura, Sonogashira couplings in water |

| Subcritical Water | Tuning dielectric constant with temperature [37] | Pressurized hot water systems | Green extraction of botanicals |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Green Spectrophotometric Analysis of a Ternary Drug Mixture using DDRSM and AUC [36]

1. Reagent and Standard Preparation:

- Solvent: Use high-purity water as the sole solvent.

- Standard Stock Solutions: Accurately weigh Aceclofenac (ACE), Paracetamol (PAR), and Tramadol (TRM) reference standards. Dissolve and dilute with water to prepare stock solutions of known concentration.

- Working Standard Solutions: Dilute the stock solutions with water to obtain working standards within the linear range (see Table 1).

2. Instrumentation and Data Acquisition:

- Use a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (e.g., JASCO series).

- Scan the zero-order absorption spectra of the individual working standards and the ternary mixture solutions over a predefined wavelength range (e.g., 200-400 nm). Store all spectra.

3. Double Divisor Ratio Spectra Method (DDRSM) for ACE:

- Prepare Double Divisor: Add the stored standard spectra of PAR (B') and TRM (C') to create a double divisor spectrum (B' + C').

- Obtain Ratio Spectrum: Divide the stored spectrum of the ternary mixture (A+B+C) by the double divisor spectrum (B' + C').

- Regenerate Zero-Order Spectrum: Multiply the resulting ratio spectrum by the same double divisor (B' + C'). This yields the zero-order spectrum of ACE, which is used for its quantification at a specific wavelength.

4. Area Under the Curve (AUC) Method:

- For each component, select a specific wavelength range (λ1 to λ2) in the zero-order spectrum where the component shows significant absorption.

- Calculate the area under the curve for this selected range for both standard and sample solutions.

- Construct a calibration curve by plotting the AUC values against the concentrations of the standard solutions. Use this curve to determine the concentration in unknown samples.

Protocol 2: Surfactant-Assisted Reaction in Water [39]

1. Setup:

- Charge a reaction vessel with high-purity water.

- Add a small amount (e.g., 1-2% w/w) of a "designer surfactant" like TPGS-750-M.

2. Reaction Execution:

- Add the organic reactants and catalyst to the surfactant-containing water. The reaction will proceed inside the formed micelles.

- Stir the mixture at the recommended temperature (often mild conditions to avoid the surfactant's cloud point).

3. Work-up and Isolation:

- Liquid Products: Perform an "in-flask" extraction using a minimal, recyclable amount of an organic solvent. The product will partition into the organic phase.

- Solid Products: Simply decant the aqueous phase or filter to isolate the solid product.

Visual Workflows and Diagrams

Diagram 1: DDRSM Workflow for Isolating a Component.

Diagram 2: Surfactant-Assisted 'In-Water' Synthesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Water-Based Green Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Water | Primary green solvent for analysis and reactions [36] [39]. | Base solvent for UV spectrophotometry and micellar catalysis [36] [39]. |

| Green Cosolvents (Ethanol, Glycerol) | Modifies polarity of aqueous phase to dissolve less polar analytes [37] [38]. | Mobile phase modifier in HPLC; extraction solvent [38]. |

| Chaotropic Salts | Enhances solubility of non-polar compounds via "salting-in" effect [37]. | Addition to aqueous buffer to improve analyte recovery. |

| Designer Surfactants (e.g., TPGS-750-M) | Forms micelles for solubilizing and reacting non-polar compounds in water [39]. | Enabling Suzuki-Miyaura and Sonogashira couplings in aqueous media [39]. |

| Primary Secondary Amine (PSA) | Sorbent for sample clean-up in QuEChERS, removing fatty acids and sugars [40]. | Purifying extracts in pesticide residue analysis from complex matrices [40]. |

Troubleshooting Complex Samples and Optimizing Analytical Performance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)