Validating Hyperspectral Imaging for Soil Contamination: A 2025 Review of Methods, AI Integration, and Detection Limits

This article provides a comprehensive validation of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) as a non-invasive, rapid tool for soil contamination assessment.

Validating Hyperspectral Imaging for Soil Contamination: A 2025 Review of Methods, AI Integration, and Detection Limits

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive validation of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) as a non-invasive, rapid tool for soil contamination assessment. Targeting researchers and environmental scientists, it explores the foundational principles of HSI in detecting diverse pollutants, including microplastics and heavy metals. We detail cutting-edge methodological approaches that integrate machine learning and deep learning, with a specific focus on overcoming key challenges like detection limits and data complexity. The scope includes a comparative analysis of sensor technologies and algorithmic performance, presenting evidence that validates HSI as a viable alternative to traditional, labor-intensive chemical methods for large-scale environmental monitoring.

The Science of Seeing the Invisible: Hyperspectral Imaging Fundamentals for Soil Contamination

Soil contamination from pollutants like microplastics, heavy metals, and hydrocarbons poses a significant threat to environmental safety and food security. Detecting these contaminants has traditionally relied on labor-intensive, costly, and destructive laboratory methods. Hyperspectral Imaging (HSI) has emerged as a powerful, non-invasive alternative. This technology operates on a core principle: every material interacts with light in a unique way, resulting in a characteristic spectral signature. This guide explores how these light-matter interactions are harnessed to detect and quantify soil pollutants, comparing the performance of HSI with established analytical techniques.

The Core Principles of Light-Pollutant Interaction

Hyperspectral imaging works by capturing the reflectance of light from a soil sample across hundreds of narrow, contiguous wavelength bands, typically from the visible (VIS) to the short-wave infrared (SWIR) spectrum [1]. When light hits the soil, pollutants within it alter its reflectance properties in predictable ways based on their molecular composition.

- Microplastics: Synthetic polymers like polyethylene (PE) and polyamide (PA) have specific chemical bonds (e.g., C-H, C-C) that vibrate at characteristic frequencies, absorbing and reflecting light in unique patterns in the near-infrared (NIR) and SWIR regions. This creates a spectral fingerprint that distinguishes them from natural soil components [2] [3].

- Heavy Metals: Unlike microplastics, heavy metals (e.g., copper, zinc, cadmium) often lack direct spectral features in the VIS-SWIR range. Instead, they are detected indirectly through their interactions with spectrally active soil constituents like organic matter, clay minerals, and iron oxides. The presence of heavy metals can alter the spectral signatures of these components, serving as a proxy for contamination [4].

- Hydrocarbons: Contaminants like crude oil and diesel have strong, direct spectral responses due to the presence of C-H bonds. These create deep absorption features in the SWIR region, which can be quantified to determine the level of contamination [5].

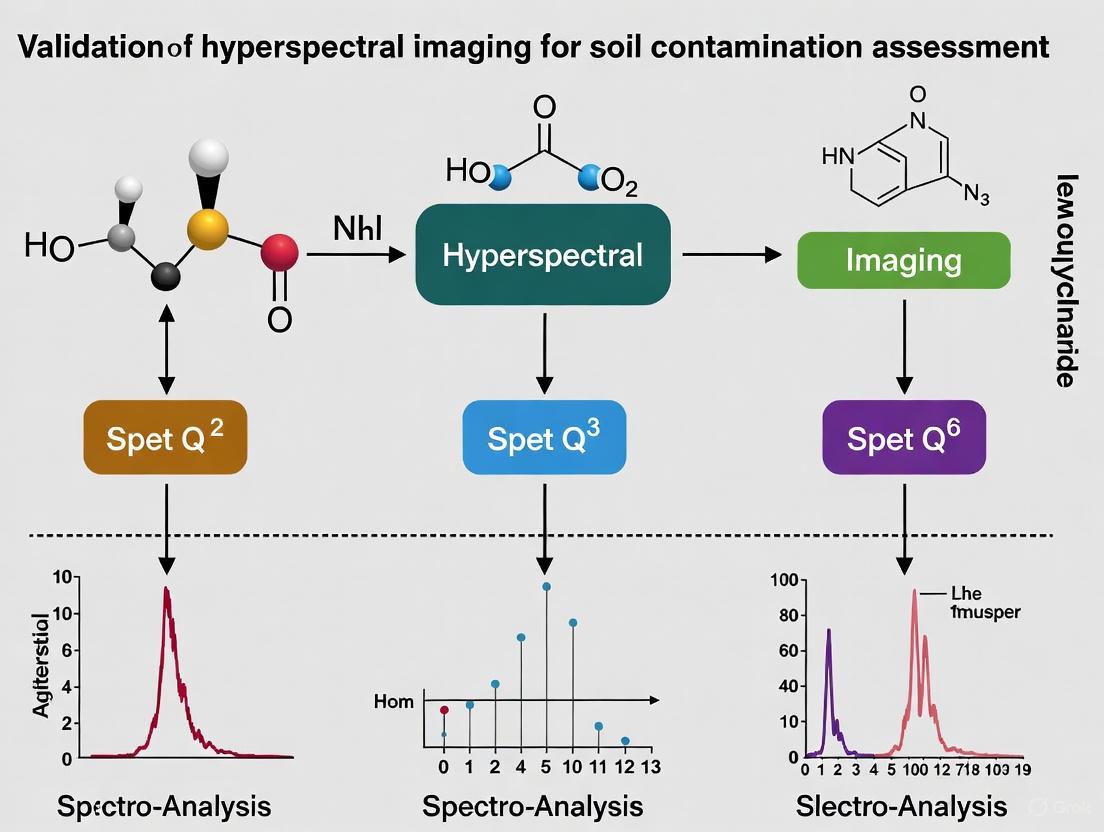

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental workflow of pollutant detection via hyperspectral imaging.

Hyperspectral Imaging vs. Alternative Analytical Techniques

The following table provides a quantitative comparison of Hyperspectral Imaging against other standard methods for detecting soil pollutants.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Soil Pollutant Detection Techniques

| Technique | Typical Pollutant | Detection Limit/Accuracy | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging (SWIR-HSI, MCT Sensor) | Microplastics (PE, PA) | >93.8% accuracy at 0.01-12% concentration [3] | Non-destructive, minimal sample prep, rapid, provides spatial distribution [2] [3] | Performance affected by soil moisture/structure [2] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging (VIS-NIR) | Microplastics (PE) | 77-84% precision for 0.5-5 mm particles [6] | Direct visualization on soil surface, no chemical digestion [6] | Lower precision for dark/black particles [6] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging with RF Model | Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Cd) | R² > 0.8 [4] | Non-invasive, zero chemical pollution, rapid large-scale monitoring [4] | Indirect detection via correlation with organic matter/clays [4] |

| Hyperspectral Imaging with XGBoost | Hydrocarbons (Diesel, Crude) | R² = 0.96, RMSE = 600 mg/kg [5] | Strong predictive ability for organic contaminants [5] | Lower accuracy for gasoline [5] |

| Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) | Microplastics | N/A (Qualitative) | High molecular specificity, non-destructive | Struggles with organic matter interference, requires intensive sample pre-treatment [2] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Microplastics | N/A (Qualitative) | High molecular specificity, non-destructive | Can be impeded by sample fluorescence [2] |

| Pyrolysis–Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (Py-GC-MS) | Microplastics | N/A (Quantitative) | Detailed chemical structure information | Destructive method, cannot be reused for analysis [2] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Hyperspectral Imaging

To ensure reproducible and reliable results, standardized experimental protocols are critical. Below are detailed methodologies for applying HSI to different pollutant types, synthesized from recent studies.

Protocol 1: Detection of Microplastics in Soil Using SWIR-HSI

This protocol is adapted from studies that achieved over 93% detection accuracy for low-concentration microplastics [3].

- Sample Preparation: Soil samples are sieved (e.g., <2 mm) and may be spiked with known types and concentrations of microplastics (e.g., 0.01% to 12% by weight). Samples are spread evenly in a container to create a uniform surface for imaging [3] [6].

- Hyperspectral Image Acquisition: A short-wave infrared hyperspectral imaging (SWIR-HSI) system is used. The study compared two sensors:

- Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT): Covers 1000-2500 nm, demonstrating superior performance.

- Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs): Covers 800-1600 nm. The imaging system scans the soil sample, capturing a hypercube where each pixel contains a full spectral signature [3].

- Spectral Data Preprocessing: Raw spectra are preprocessed to reduce noise and enhance features. Techniques include:

- Savitzky-Golay smoothing to reduce spectral noise.

- Multiple Scattering Correction (MSC) or Standard Normal Variate (SNV) to correct for light scattering effects.

- Derivative transformations (first or second order) to resolve overlapping spectral features and highlight key absorption peaks [4].

- Machine Learning and Classification: Processed spectral data are analyzed using machine learning models.

- Pixel-wise classification algorithms like Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Logistic Regression are trained to distinguish the spectral signatures of microplastics from soil.

- The model's performance is validated, resulting in a classification map that visually identifies the spatial distribution of microplastic particles on the soil surface [3] [6].

Protocol 2: Inversion of Heavy Metal Content in Soil

This protocol outlines an indirect approach for estimating heavy metal concentrations, as used in studies of black soil farmland [4].

- Soil Sampling and Lab Analysis: A large number of soil samples (e.g., 119) are collected from the field. These samples undergo traditional laboratory chemical analysis to determine the precise concentrations of heavy metals like Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), and Cadmium (Cd).

- Spectral Measurement and Preprocessing: In the lab, the spectral reflectance of each soil sample is measured using a high-resolution spectrometer (e.g., ASD FieldSpec4) across the 350-2500 nm range. The spectra are then preprocessed using a combination of techniques, including first- and second-order derivatives, multiple scattering correction, and Savitzky-Golay smoothing [4].

- Feature Band Selection: The Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA) is used to identify the most informative wavelengths (characteristic bands) that are strongly correlated with the heavy metal content, reducing data dimensionality and minimizing redundancy [4].

- Inversion Model Development: Machine learning models are trained to establish the nonlinear relationship between the selected spectral features and the lab-measured heavy metal concentrations. Studies show that the Random Forest (RF) model can outperform Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) models, achieving R² values greater than 0.8 [4].

The workflow for these protocols, from sample preparation to final analysis, is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of hyperspectral imaging for soil analysis relies on a suite of specialized tools, sensors, and computational models.

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Hyperspectral Soil Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SWIR-HSI with MCT Sensor | A hyperspectral camera with Mercury Cadmium Telluride detector; highly sensitive in 1000-2500 nm range. | Key for detecting microplastics at very low concentrations (0.01%) with high accuracy [3]. |

| ASD FieldSpec4 Spectrometer | A high-resolution field/lab spectrometer for measuring soil reflectance from 350-2500 nm. | Used for precise spectral measurement of soil samples for heavy metal inversion models [4]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A supervised machine learning algorithm for classification and regression. | Effectively classifies different types and sizes of microplastic particles in soil [2] [6]. |

| Random Forest (RF) Model | An ensemble machine learning algorithm based on decision trees. | Achieves high accuracy (R² > 0.8) for predicting heavy metal concentrations in soil [4]. |

| XGBoost Regressor | An optimized gradient boosting machine learning algorithm. | Provides a robust balance of accuracy and performance for predicting hydrocarbon levels [5]. |

| Spectral Preprocessing Algorithms | Computational techniques (e.g., Savitzky-Golay, MSC, Derivatives) to clean and enhance spectral data. | Critical step for improving signal-to-noise ratio and model performance across all pollutant types [4]. |

Hyperspectral imaging technology, grounded in the precise principles of light-pollutant interaction, offers a transformative approach for soil contamination assessment. While traditional methods like FTIR and Py-GC-MS provide high specificity, HSI stands out for its rapid, non-destructive, and spatially explicit monitoring capabilities. Experimental data confirms that HSI, particularly when paired with advanced sensors like MCT and robust machine learning models like Random Forest and XGBoost, can achieve high accuracy in detecting microplastics, quantifying hydrocarbons, and estimating heavy metal content. The choice between HSI and alternative techniques ultimately depends on the specific research goals, balancing the need for minimal sample preparation and high-throughput analysis against the requirement for ultimate molecular specificity.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is emerging as a powerful, non-invasive tool for environmental monitoring, capable of detecting a range of soil contaminants. This guide objectively compares the performance of HSI technologies in identifying two critical pollutant classes: microplastics and heavy metals, providing researchers with a data-driven assessment of its current capabilities and limitations.

Comparative Performance of Hyperspectral Imaging for Contaminant Detection

The efficacy of hyperspectral imaging varies significantly depending on the target contaminant, the sensor technology used, and the implemented data processing model. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance comparison of hyperspectral imaging for detecting different soil contaminants

| Contaminant Type | Sensor Technology | Spectral Range | Key Model(s) | Reported Performance | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microplastics (Polyamide, Polyethylene) | Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) | 1000–2500 nm | Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 93.8% accuracy | 0.01% (weight) | [3] [7] |

| Microplastics (Polyamide, Polyethylene) | Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) | 800–1600 nm | Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine (SVM) | 68.8% accuracy | 0.01% (weight) | [3] [7] |

| Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Cd) | ASD FieldSpec4 Spectrometer (Lab) | 350–2500 nm | Random Forest (RF) | R² > 0.8 | Not Specified | [4] |

| Heavy Metals (Cu, Zn, Cd) | ASD FieldSpec4 Spectrometer (Lab) | 350–2500 nm | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Lower accuracy than RF | Not Specified | [4] |

| Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) | HySpex VNIR-SWIR (Lab) | 400–2500 nm | Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR) | R² = 0.66 | Not Specified | [8] |

Analysis of Key Findings

- Sensor Technology is Critical for Microplastics: For microplastic detection, the choice of sensor is a primary factor. The MCT sensor, with its extended range into the short-wave infrared (SWIR), significantly outperformed the InGaAs sensor, achieving over 93% accuracy compared to 69%. This is attributed to the MCT's higher sensitivity and coverage of spectral regions where plastic-specific molecular bonds are most active [3] [7].

- Machine Learning Models Must Be Matched to the Contaminant: For heavy metal inversion, which relies on indirect correlations with spectrally active soil components, non-linear models like Random Forest (RF) have demonstrated superior performance (R² > 0.8) compared to other models like Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) [4]. For microplastics, simpler models like Logistic Regression and SVM can be highly effective when paired with the correct sensor data [7].

- Detection Limits Present a Challenge: While HSI can detect microplastics at concentrations as low as 0.01%, accuracy declines markedly at these trace levels, especially for the less sensitive InGaAs sensor [7]. This highlights a significant challenge for monitoring low-level, yet environmentally relevant, contamination.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines the core methodologies from the studies cited in the performance comparison.

Protocol for Microplastic Detection in Soils

This protocol is adapted from the study that demonstrated high accuracy using an MCT sensor [3] [7].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Soil samples are spiked with specific types and sizes of microplastics (e.g., polyethylene and polyamide with maximum particle sizes of 300 μm and 50 μm, respectively). The samples are prepared to represent a range of concentrations, typically from very low (0.01-0.1%) to high (1-12%) weight percentages.

- 2. Hyperspectral Image Acquisition: Prepared soil samples are scanned using two synchronized short-wave infrared HSI (SWIR-HSI) platforms for comparison:

- An MCT (Mercury Cadmium Telluride) sensor operating in the 1000-2500 nm range.

- An InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide) sensor operating in the 800-1600 nm range.

- 3. Spectral Data Preprocessing: Raw spectral data is preprocessed to reduce noise and enhance features. Techniques include Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) for dimension reduction and feature extraction.

- 4. Machine Learning Model Training: Extracted spectral features are used to train classification models. The study effectively employed Logistic Regression and Support Vector Machines (SVM) with both linear and nonlinear kernels to distinguish between microplastic particles and soil.

- 5. Validation: Model performance is validated using metrics such as overall accuracy, typically through cross-validation or a hold-out test set, reporting the mean and standard deviation across multiple runs.

Protocol for Heavy Metal Inversion in Soils

This protocol is derived from research on black soils in Jilin Province, which found success with Random Forest models [4].

- 1. Field Sampling and Lab Analysis: A large number of topsoil samples (e.g., 119 samples from a 10-20 cm depth) are collected from the study area. These samples undergo traditional laboratory chemical analysis to determine the precise concentrations of heavy metals like copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), and cadmium (Cd).

- 2. Soil Spectral Measurement: In the laboratory, the spectral reflectance of prepared (dried, crushed, and sieved) soil samples is measured using a high-resolution spectrometer like an ASD FieldSpec4, which covers the 350-2500 nm range.

- 3. Spectral Data Transformation and Preprocessing: The raw spectra are processed to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and highlight features related to heavy metal complexes. Common techniques include:

- First- and second-order derivatives.

- Multiple Scatter Correction (MSC).

- Savitzky-Golay (SG) smoothing.

- Standard Normal Variate (SNV) correction.

- 4. Feature Band Selection: The Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA) is used to identify a subset of characteristic wavelengths most correlated with the heavy metal concentrations, reducing data dimensionality.

- 5. Inversion Model Building: The transformed spectral data and selected features are used to train and compare multiple machine learning models, including Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression. The model demonstrating the highest R² and lowest error on validation data is selected as the optimal inversion model.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized experimental workflow for hyperspectral detection of soil contaminants, integrating the key steps from the protocols above.

Hyperspectral Soil Contaminant Analysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful hyperspectral analysis requires specific tools for sample preparation, data acquisition, and processing. The following table details the key materials and their functions.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and solutions for hyperspectral soil analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ASD FieldSpec4 Spectrometer | Laboratory-grade measurement of soil spectral reflectance. | Covers 350-2500 nm range; high spectral resolution for precise heavy metal inversion [4]. |

| HySpex VNIR-1800 & SWIR-384 Sensors | Proximal sensing of soil surfaces for SOC and property mapping. | High spatial and spectral resolution; enables identification of pure soil pixels via spectral unmixing [8]. |

| MCT (Mercury Cadmium Telluride) Sensor | Short-wave infrared (SWIR) imaging for microplastic detection. | 1000-2500 nm range; high sensitivity crucial for detecting low (0.01%) microplastic concentrations [3] [7]. |

| InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide) Sensor | Short-wave infrared (SWIR) imaging for comparison with MCT. | 800-1600 nm range; less accurate for trace microplastics than MCT [3] [7]. |

| Spectral Preprocessing Algorithms | Enhancing spectral data quality and feature extraction. | Includes Derivatives, MSC, SNV, and Savitzky-Golay smoothing to reduce noise and correct scatter [4] [8]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries (e.g., Scikit-learn) | Developing contaminant classification and regression models. | Provides implementations of Random Forest, SVM, and Logistic Regression for modeling spectral data [4] [7]. |

Hyperspectral imaging presents a validated, non-invasive approach for soil contamination assessment. The technology demonstrates high proficiency in detecting microplastics, with performance heavily dependent on advanced SWIR sensors like MCT. For heavy metals, its power lies in coupling indirect spectral features with robust non-linear models like Random Forest. While challenges remain in detecting contaminants at trace concentrations, the integration of advanced sensors and tailored machine learning protocols positions HSI as a transformative tool for large-scale, high-resolution soil monitoring.

Spectral Libraries and the Unique Fingerprints of Common Pollutants

The accurate identification of environmental pollutants in soil has entered a new era with the advancement of hyperspectral imaging (HSI) and the development of comprehensive spectral libraries. These technologies enable researchers to detect and quantify contaminants based on their unique molecular "fingerprints"—distinct spectral signatures that arise from the interaction of light with matter. For soil contamination assessment, this non-invasive approach provides a rapid, cost-effective alternative to traditional laboratory methods, allowing for large-scale monitoring and precise mapping of polluted areas. The validation of HSI for this purpose hinges on the existence of robust, curated spectral libraries that contain reference signatures for a wide range of common pollutants, from hydrocarbons to microplastics.

The fundamental principle underpinning this methodology is that every compound exhibits a characteristic spectral signature due to its specific chemical bonds and molecular structure. When hyperspectral sensors capture reflected light across hundreds of narrow, contiguous wavelength bands, they record these unique patterns, which can then be matched against reference entries in spectral libraries. This process transforms the complex task of chemical identification into a pattern-matching problem, facilitated by sophisticated machine learning algorithms. The integration of these technologies creates a powerful framework for environmental monitoring, particularly in the context of increasing industrial pollution and microplastic accumulation in agricultural soils.

The Role and Composition of Spectral Libraries

Spectral libraries serve as essential knowledge bases for compound annotation in untargeted analysis, functioning as curated collections of reference spectra against which unknown samples can be compared. The concept dates back to the 1950s, but has seen exponential growth in recent years with the expansion of computational resources and data sharing platforms. These libraries operate on the premise that molecules undergo reproducible fragmentation or light interaction patterns, creating distinctive spectral fingerprints that can be used for identification purposes. In mass spectrometry-based libraries, this involves matching fragmentation patterns, while in hyperspectral imaging, the focus is on matching reflectance or absorption spectra across optical wavelengths [9].

The landscape of available spectral libraries is diverse, encompassing both commercial and open-access resources. Some of the most extensive libraries include the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) tandem mass spectral library, which contains over 265,000 organic compounds and is widely used across industries for chemical identification. Similarly, METLIN Gen2 spectral library and mzCloud represent significant commercial collections with extensive fragmentation data. On the open-access side, resources like the Global Natural Products Social Molecular Networking (GNPS) community spectral libraries and Massbank of North America (MoNA) aggregate reference spectra from multiple contributors, creating comprehensive knowledge bases that are freely available to the research community [9] [10].

Library Growth and Quality Considerations

The past decade has witnessed explosive growth in publicly accessible spectral libraries, with some resources expanding more than 60-fold in the past eight years alone. This expansion has dramatically improved the coverage of chemical space, enabling researchers to identify a broader range of pollutants with higher confidence. The growth isn't merely quantitative; quality curation practices ensure that library entries maintain high standards of accuracy and reliability. The NIST library, for instance, employs rigorous quality control procedures, with specialists filtering, recalibrating, and structurally annotating each spectrum to maintain consistency and reliability—a level of curation that sets it apart from other resources [9] [10].

Table 1: Major Spectral Libraries and Their Characteristics

| Library Name | Type | Approximate Size | Primary Focus | Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NIST Tandem Mass Spectral Library | Mass Spectrometry | >265,000 compounds | Broad coverage, emphasis on organic compounds | Commercial |

| mzCloud | Mass Spectrometry | Millions of spectra (largest by spectra count) | Small molecules, extensive fragmentation trees | Commercial |

| GNPS Community Libraries | Mass Spectrometry | Hundreds of thousands of spectra | Natural products, environmental compounds | Open Access |

| MoNA (MassBank of North America) | Mass Spectrometry | Hundreds of thousands of spectra | Aggregated from multiple sources | Open Access |

| METLIN Gen2 | Mass Spectrometry | Tens of thousands of compounds | Lipids, dipeptides, metabolites | Commercial |

| HyperSoilNet (from research) | Hyperspectral Imaging | Framework for soil properties | Soil nutrients and contaminants | Research Framework |

The quality of spectral libraries directly impacts identification confidence. Several factors determine quality: spectral accuracy, which depends on proper calibration and instrument conditions; annotation completeness, including structural information and metadata; and coverage of relevant chemical space. For soil contamination studies, libraries must include reference spectra for common pollutants acquired under conditions similar to field applications. The emergence of standardized spectral hashes (SPLASH) helps track provenance and detect duplicates across different library resources, ensuring greater transparency and reliability in compound identification [9].

Hyperspectral Imaging for Soil Pollutant Detection

Sensor Technologies and Performance Comparison

Hyperspectral imaging systems employ different sensor technologies that significantly impact their ability to detect soil pollutants. The most common sensors for soil analysis include indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) and mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detectors, which operate in different spectral ranges with varying sensitivity characteristics. InGaAs sensors typically cover the 800-1600 nm range, while MCT sensors extend further into the short-wave infrared (1000-2500 nm), capturing a broader range of molecular absorption features that are critical for identifying many organic pollutants [7].

Recent comparative studies have demonstrated significant performance differences between these sensor technologies for detecting pollutants at low concentrations. In research focused on microplastic detection in soils, the MCT sensor achieved an overall accuracy of 93.8 ± 1.47% across concentration ranges of 0.01-12%, substantially outperforming the InGaAs sensor, which achieved only 68.8 ± 3.76% accuracy under the same conditions. This performance advantage was particularly pronounced at lower contamination levels (0.01-0.10%), where the MCT sensor maintained reasonable detection capability while the InGaAs sensor showed markedly reduced accuracy. The superior performance of MCT sensors is attributed to their extended spectral coverage (particularly the 1600-2500 nm range) and higher sensitivity, enabling better detection of the subtle spectral features associated with low concentrations of pollutants [7] [3].

Table 2: Sensor Performance Comparison for Microplastic Detection in Soil

| Sensor Type | Spectral Range | Overall Accuracy (0.01-12%) | Accuracy at High Concentration (1.0-12%) | Accuracy at Low Concentration (0.01-0.10%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) | 1000-2500 nm | 93.8 ± 1.47% | >94% | Significantly higher than InGaAs |

| Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) | 800-1600 nm | 68.8 ± 3.76% | >94% | Markedly reduced |

Detection Methodologies and Workflows

The process of detecting soil pollutants through hyperspectral imaging follows a structured workflow that begins with data acquisition and proceeds through multiple processing stages to final identification. A typical protocol involves collecting hyperspectral data using either laboratory-based or field-deployable systems, followed by preprocessing steps to reduce noise and correct for instrumental artifacts. The critical stage of spectral feature extraction then identifies meaningful patterns in the data, which serve as inputs for machine learning classification or regression models that correlate spectral features with pollutant identity and concentration [1] [7].

For microplastic detection, researchers have employed standardized experimental protocols wherein soil samples are spiked with known concentrations of target pollutants (e.g., polyamide and polyethylene at particle sizes of 50μm and 300μm, respectively). Hyperspectral imaging is then performed using both MCT and InGaAs sensors across multiple concentration ranges (0.01-0.10%, 0.10-1.0%, and 1.0-12%). The acquired spectral data undergoes preprocessing including normalization and dimensionality reduction via principal component analysis (PCA) or partial least squares (PLS), before being analyzed using machine learning classifiers such as logistic regression and support vector machines with both linear and nonlinear kernels [7].

For hydrocarbon contamination, a similar approach has proven effective. Studies evaluating soil contamination with crude oil, diesel, and gasoline (0-10,000 mg/kg) across different soil types (clayey, silty, sandy) employ hyperspectral imaging to capture spectral signatures, which are then correlated with reference contamination values obtained through gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The models are trained and validated using various machine learning approaches, with ensemble methods like XGBoost consistently providing the best balance between accuracy and robustness, achieving R-squared values of 0.96 and root mean square error (RMSE) of 600 mg/kg on testing sets [5].

Hyperspectral Soil Analysis Workflow

Machine Learning Approaches for Spectral Data Analysis

Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Models

The analysis of hyperspectral data for pollutant detection relies heavily on machine learning algorithms capable of handling high-dimensional spectral data and capturing complex, nonlinear relationships between spectral features and pollutant concentrations. Studies systematically comparing different machine learning approaches have revealed distinct performance characteristics across model types. For hydrocarbon contamination assessment, ensemble methods like XGBoost regressors have demonstrated particularly strong performance, achieving R-squared values of 0.96 and RMSE of 600 mg/kg when predicting hydrocarbon levels in testing sets. These models consistently provide a good balance between accuracy and robustness, making them well-suited for practical spectral applications in environmental monitoring [5].

The performance variation across different pollutant types and soil matrices is significant. In hydrocarbon contamination studies, models for gasoline generally show lower accuracy due to less distinguishable spectral features compared to diesel and crude oil, which exhibit more pronounced spectral signatures. Similarly, the soil matrix itself (clayey, silty, or sandy) influences model performance, necessitating calibration across soil types or the inclusion of soil-specific models. The selection of input features—whether full spectral ranges or strategically selected spectral bands—also substantially impacts model performance, with careful feature selection reducing overfitting while maintaining predictive accuracy [5].

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks

Recent advances in soil pollutant detection have seen the development of sophisticated hybrid frameworks that combine the strengths of deep learning representation with traditional machine learning techniques. The HyperSoilNet framework exemplifies this approach, leveraging a pretrained hyperspectral-native CNN backbone integrated with an optimized machine learning ensemble. This architecture combines the feature extraction capabilities of deep neural networks with the regression performance of traditional ML models, achieving a score of 0.762 on the HyperView challenge leaderboard for predicting soil properties including contaminants [1].

The integration of self-supervised learning approaches represents another significant advancement in the field. By employing contrastive learning frameworks that pull together different augmented views of the same sample in feature space while pushing apart views of different samples, models can capture meaningful spectral patterns without extensive labeled datasets. This is particularly valuable for soil contamination studies, where obtaining large quantities of labeled training data (with precise chemical validation) is expensive and time-consuming. These self-supervised approaches enable models to develop robust spectral feature encodings that can be fine-tuned for specific pollutant detection tasks with limited labeled examples [1].

Table 3: Machine Learning Model Performance for Soil Contaminant Detection

| Model Type | Application | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost Regressor | Hydrocarbon contamination | R² = 0.96, RMSE = 600 mg/kg | Good accuracy/robustness balance | Performance varies by petroleum type |

| Support Vector Machines (Linear/Nonlinear) | Microplastic detection | 93.8% accuracy with MCT sensor | Effective for high-dimensional data | Sensitive to parameter tuning |

| Artificial Neural Networks | Soil moisture (proxy for some contaminants) | R² = 0.9557 | Captures complex nonlinear relationships | Requires substantial data |

| HyperSoilNet (Hybrid CNN+ML Ensemble) | Multiple soil properties | Leaderboard score: 0.762 | Combines deep feature learning with ML regression | Computational complexity |

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Implementing hyperspectral imaging for soil contamination assessment requires specific research reagents and materials that facilitate sample preparation, data acquisition, and analysis. The following table details essential components of the experimental toolkit, drawn from methodologies described in recent research publications:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Soil Contamination Analysis

| Item | Function | Example Specifications | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCT (Mercury Cadmium Telluride) Sensor | Hyperspectral image acquisition in SWIR range | Spectral range: 1000-2500 nm | Primary sensor for microplastic detection [7] |

| InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide) Sensor | Hyperspectral image acquisition in NIR range | Spectral range: 800-1600 nm | Comparison sensor for performance evaluation [7] |

| Reference Soil Samples | Validation and calibration | Clayey, silty, sandy types with characterized properties | Method validation across soil matrices [5] |

| Certified Pollutant Standards | Quantitative spike experiments | Polyethylene, polyamide, crude oil, diesel, gasoline | Creating concentration gradients for model training [7] [5] |

| GC-MS Instrumentation | Reference contamination measurements | Chromatographic separation with mass detection | Ground truth data for hydrocarbon contamination [5] |

| NIST Mass Spectral Library | Reference spectral database | >265,000 organic compounds | Compound identification and verification [9] [10] |

| mzCloud Library | Advanced spectral matching | Multi-stage MSn spectra with structural annotation | In-depth structural identification for unknowns [11] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized experimental protocols are critical for generating reproducible, comparable results in soil contamination studies using hyperspectral imaging. For microplastic detection, a representative protocol involves collecting intact soil cores or preparing homogenized soil samples, which are then spiked with known concentrations of target microplastics (e.g., 0.01-12% weight/weight). The samples are stabilized in sample holders and scanned using both MCT and InGaAs hyperspectral imaging systems under controlled illumination conditions. Following image acquisition, spectral data is extracted from regions of interest, preprocessed to reduce noise and correct for scattering effects, and then analyzed using machine learning classifiers such as support vector machines with cross-validation to assess detection accuracy across concentration ranges [7] [3].

For hydrocarbon contamination assessment, the methodological approach typically involves creating synthetically contaminated soil samples across a concentration gradient (0-10,000 mg/kg) for different petroleum products (crude oil, diesel, gasoline) and soil types (clayey, silty, sandy). Hyperspectral imaging is performed under standardized conditions, with parallel samples analyzed using GC-MS to establish reference contamination values. The spectral data is then partitioned into training and testing sets, with machine learning models (including XGB regressors and neural networks) trained to predict contamination levels from spectral features. Model performance is evaluated using R-squared and RMSE metrics, with particular attention to performance variation across petroleum types and soil matrices [5].

Analysis Pathways and Decision Framework

The interpretation of hyperspectral data for pollutant identification follows a structured analytical pathway that progresses from raw data to confident identification. This pathway involves multiple decision points where analytical strategies are selected based on data quality and research objectives. The process typically begins with an assessment of spectral data quality, followed by feature extraction to reduce dimensionality while retaining diagnostically valuable information. The subsequent pattern recognition phase employs machine learning models trained to recognize characteristic spectral signatures of specific pollutants, with confidence levels assigned based on statistical measures and spectral matching scores [1] [5].

Pollutant Identification Decision Pathway

When library searching produces inconclusive matches, advanced analytical strategies come into play. The mzLogic algorithm exemplifies such an approach, using spectral similarity and sub-structural information (precursor ion fingerprinting) to rank potential candidates even when no direct library match exists. This method leverages the comprehensive fragmentation information in large spectral libraries like mzCloud to identify common sub-structural elements, which are then used to score and filter candidate compounds from chemical databases. This enables researchers to propose plausible structural hypotheses for completely unknown compounds, significantly expanding the range of identifiable pollutants beyond those represented in reference libraries [11] [9].

For validation of identifications, particularly for novel or unexpected pollutants, orthogonal analytical techniques are essential. The Metabolomics Standards Initiative outlines different levels of identification confidence, with level 1 representing confirmed structure through co-analysis with authentic standards or complementary techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). In practice, this might involve comparing chromatographic retention times with standards, performing additional spectral analyses under different fragmentation conditions, or applying complementary spectroscopic methods. This multi-tiered validation framework ensures that hyperspectral identification of soil pollutants meets the rigorous standards required for environmental monitoring and regulatory decision-making [9].

The integration of hyperspectral imaging with comprehensive spectral libraries represents a transformative advancement in soil contamination assessment, enabling rapid, non-invasive detection and quantification of pollutants based on their unique spectral fingerprints. The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that sensor selection critically influences detection capability, with MCT sensors outperforming InGaAs alternatives for identifying low concentrations of pollutants like microplastics. Similarly, machine learning approaches, particularly ensemble methods and hybrid deep learning frameworks, have proven highly effective at extracting meaningful patterns from complex spectral data, achieving impressive accuracy in quantifying hydrocarbon contamination across diverse soil matrices.

Looking forward, several emerging trends promise to further enhance the capabilities of hyperspectral approaches for soil monitoring. The continuous expansion of spectral libraries, with both commercial and open-access resources growing at an accelerating pace, will improve coverage of pollutant diversity and increase identification confidence. Advances in sensor technology, including miniaturization and reduced costs, will make hyperspectral systems more accessible for routine environmental monitoring. Additionally, the development of more sophisticated machine learning approaches, particularly self-supervised and semi-supervised methods, will help address the challenge of limited labeled training data. As these technologies mature and integrate into environmental monitoring frameworks, hyperspectral imaging is poised to become an indispensable tool for addressing the growing challenge of soil pollution assessment and remediation on a global scale.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) is revolutionizing soil contamination assessment by offering distinct advantages over traditional laboratory methods. This guide objectively compares the performance of HSI against conventional techniques, supported by recent experimental data and detailed methodologies.

↳ Non-Destructive Analysis: Preserving Sample Integrity

Traditional soil analysis relies on chemical methods that are destructive, altering or consuming the sample. In contrast, HSI is a non-invasive, non-destructive technique that analyzes targets without physical or chemical alteration, preserving sample integrity for future research or archival purposes [12] [13] [14].

Experimental Evidence in Soil Science: A 2025 proximal sensing experiment demonstrated HSI's capability to quantify Soil Organic Carbon (SOC) in undisturbed soil surfaces. Researchers carefully removed contiguous topsoil pieces, air-dried them, and scanned them with HySpex VNIR-1800 and SWIR-384 hyperspectral sensors in the laboratory. This approach directly analyzed undisturbed soil structures, whereas conventional methods would have required destruction through sieving and grinding [8].

Comparative Performance Data: Table 1: Comparison of SOC Estimation Performance Using Different Spectral Data Approaches

| Method | Data Processing Approach | R² | RMSE (g kg⁻¹) | Destructive to Sample? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chemical Analysis | Laboratory wet chemistry | (Reference) | (Reference) | Yes |

| HSI with Unprocessed Image Data | Mean absorbances from full image | 0.36 | 5.03 | No |

| HSI with Pure Soil Pixels | Spectral unmixing to remove non-soil materials | 0.66 | 3.68 | No |

The experimental workflow for this non-destructive analysis involved several key steps, as illustrated below:

↳ Rapid Analysis: Accelerating Data Acquisition and Processing

Traditional soil analysis methods are time-consuming, requiring extensive sample preparation, chemical processing, and skilled laboratory work. HSI combined with modern machine learning dramatically accelerates both data acquisition and analysis [12] [14].

Experimental Evidence in Food Science: While focused on food composition analysis, a 2024 study demonstrates HSI's rapid screening capability relevant to soil assessment. Researchers used HSI with Ridge regression models to rapidly predict nutritional parameters in complex food products, achieving high accuracy for protein content (R² = 0.88) and moisture (R² = 0.85) without sample homogenization [14]. This approach bypasses the lengthy chemical extraction and analysis required by conventional methods.

Comparative Performance Data: Table 2: Time Efficiency Comparison Between Traditional and HSI Methods

| Method | Sample Preparation Time | Analysis Time | Total Processing Time | Suitable for High-Throughput? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chemical Analysis | Extensive (drying, grinding, chemical extraction) | Hours to days | Days to weeks | Limited |

| HSI with Machine Learning | Minimal (placement for scanning) | Minutes to hours | Hours to days | Excellent |

The rapid analysis workflow leverages machine learning for efficient prediction, as shown below:

↳ Large-Scale Analysis: From Laboratory to Field Applications

Traditional soil analysis provides point-based measurements that may not represent larger field variability, making large-scale assessment costly and time-consuming [1]. HSI enables scalable analysis from microscopic to regional levels through adaptable platforms including laboratories, field instruments, and airborne systems [12].

Experimental Evidence in Regional Assessment: A 2025 study introduced HyperSoilNet, a hybrid deep learning framework for estimating soil properties from hyperspectral imagery. This approach addresses the challenge of mapping soil characteristics like potassium oxide (K₂O), phosphorus pentoxide (P₂O₅), magnesium (Mg), and pH across large agricultural regions [1]. The model achieved a score of 0.762 on the Hyperview challenge leaderboard, demonstrating accurate large-scale soil assessment capabilities.

Platform Comparison for Scalable Analysis: Table 3: HSI Platforms for Different Spatial Scales in Soil Assessment

| Platform | Spatial Coverage | Key Applications in Soil Assessment | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laboratory Scanners | Single samples to multiple samples | Detailed analysis of soil composition, contamination mapping | Controlled conditions, highest data quality |

| Field Portable Systems | Plot to field scale | In-situ soil monitoring, targeted contamination assessment | Affected by ambient conditions, requires calibration |

| Airborne & UAV Systems | Hundreds of square kilometers | Regional soil mapping, contamination hotspot identification | Requires ground truthing, affected by atmospheric conditions |

The integration of HSI across multiple scales creates a comprehensive soil assessment framework:

↳ The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Solutions for HSI Soil Contamination Assessment

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HSI Soil Contamination Research

| Solution / Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Imaging Sensors (VNIR, SWIR) | Captures spectral-spatial data cubes from soil samples | Laboratory, field, and airborne platforms |

| Spectral Calibration Panels | Provides reference for reflectance conversion | Field and laboratory measurements |

| Spectral Unmixing Algorithms | Separates mixed pixel spectra into pure components | Data processing for improved accuracy |

| Machine Learning Frameworks (e.g., HyperSoilNet) | Analyzes high-dimensional spectral data | Soil property prediction and contamination mapping |

| Ground Truth Soil Samples | Validates and calibrates HSI models | Essential for model accuracy across all applications |

Hyperspectral imaging establishes a new paradigm for soil contamination assessment through its non-destructive nature, rapid analytical capabilities, and scalability across multiple spatial dimensions. While traditional methods remain valuable for specific calibration purposes, HSI offers researchers a powerful tool for comprehensive, efficient soil analysis that preserves sample integrity and enables monitoring at previously impractical scales.

From Data to Detection: Methodologies and Real-World Applications of HSI in Soil Analysis

The validation of hyperspectral imaging for soil contamination assessment represents a critical advancement in environmental monitoring. Short-wave infrared (SWIR) hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has emerged as a powerful, non-destructive technique for identifying and quantifying pollutants in agricultural and natural landscapes. This technology captures detailed spectral data across hundreds of contiguous bands, enabling the detection of contaminants based on their unique molecular absorption signatures. Unlike traditional methods that require time-consuming sample preparation and chemical analysis, SWIR-HSI offers rapid, in-situ assessment capabilities essential for large-scale soil health monitoring. The effectiveness of this approach hinges fundamentally on the performance of the sensor technology deployed. Among available options, mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) and indium gallium arsenide (InGaAs) detectors represent the two primary sensor technologies competing for dominance in SWIR hyperspectral imaging applications. This comparison guide objectively evaluates their performance characteristics, supported by recent experimental data, to inform researchers and scientists developing soil contamination assessment methodologies.

SWIR hyperspectral imaging typically covers wavelengths from approximately 400 nm to 2500 nm, though different sensors cover varying portions of this range. Both MCT and InGaAs are semiconductor materials engineered to detect light in this region, but they operate on different physical principles and offer distinct performance trade-offs.

Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) sensors are alloy-based detectors whose spectral response can be tuned by adjusting the cadmium-to-mercury ratio. This tunability allows MCT arrays to cover a broad spectral range from the visible spectrum to over 25 µm, though for SWIR applications they typically operate between 1000-2500 nm [15] [16]. MCT detectors typically require cooling to reduce dark current, with higher operating temperature (HOT) technologies being developed to mitigate size, weight, and power requirements [15].

Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) sensors are III-V compound semiconductor detectors with a typical spectral response from 900-1700 nm, though some extended versions can reach up to 2500 nm [17] [16]. The technology benefits from more mature manufacturing processes compared to MCT, contributing to lower costs and greater availability. InGaAs sensors typically operate with thermoelectric (Peltier) cooling rather than the more complex cryogenic systems often required by MCT detectors [18].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of MCT and InGaAs Sensors

| Parameter | MCT (Mercury Cadmium Telluride) | InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical SWIR Range | 1000-2500 nm [3] [19] | 800-1700 nm (standard); up to 2500 nm (extended) [17] [16] |

| Material Basis | Tunable II-VI semiconductor alloy | III-V compound semiconductor |

| Operating Temperature | Typically cooled (HOT developments) [15] | Thermoelectrically cooled [18] |

| Manufacturing Maturity | Less mature, specialized processes [16] | Well-established fabrication processes |

| Primary Advantage | Broad spectral coverage and high sensitivity | Lower cost and simpler cooling requirements |

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Technical Specifications

Recent comparative studies, particularly in environmental monitoring applications, provide compelling data on the relative performance of MCT and InGaAs sensors for hyperspectral imaging.

Detection Accuracy for Soil Contaminants

A seminal study focused on detecting microplastics in soil provides direct comparative metrics between the two technologies. Researchers evaluated the systems' abilities to identify polyethylene (PE) and polyamide (PA) particles in soil samples at concentrations ranging from 0.01% to 12% using machine learning classification [3] [19].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Soil Microplastic Detection

| Performance Metric | MCT Sensor (1000-2500 nm) | InGaAs Sensor (800-1600 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Detection Accuracy | 93.8% [3] | 68.8% [3] |

| Low Concentration Sensitivity (0.01-0.1%) | High detection capability [3] | Significantly reduced performance [3] |

| Key Advantage | Extended spectral coverage captures molecular bond features beyond 1600 nm [3] [19] | Adequate for some applications but limited by spectral range [19] |

The superior performance of MCT systems is attributed to their extended spectral coverage into the 2000-2500 nm range, where many plastic-specific molecular bonds (particularly C-H bonds) exhibit strong overtone and combination bands that provide distinct spectral fingerprints [3]. The MCT system's higher sensitivity and reduced signal noise, particularly in these chemically informative spectral regions, enable more accurate identification and classification of contaminants [3] [19].

Spectral and Dynamic Range Considerations

The effective dynamic range of hyperspectral imaging systems significantly impacts their ability to resolve materials with varying reflectivity properties within the same scene. Research has demonstrated that the effective dynamic range of InGaAs-based systems can be extended from 43 dB to 73 dB through multi-exposure techniques that compensate for limitations in low-light sensitivity and dark current effects [18]. This approach incorporates dark current modeling and multiple exposure times to maintain adequate signal-to-noise ratio across varying illumination conditions [18].

MCT sensors inherently possess advantages for low-light imaging and applications requiring broad spectral coverage, though they typically require more sophisticated cooling systems to minimize dark current [15]. Recent developments in MCT technology have focused on improving dark current performance and operating temperature to reduce size, weight, and power requirements [15].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Comparison

To ensure valid performance comparisons between MCT and InGaAs sensors, researchers should adhere to standardized experimental protocols that account for the unique characteristics of each technology.

Sample Preparation and Imaging Methodology

The soil contaminant detection study employed a rigorous methodology that serves as a model for comparative sensor evaluation [19]:

- Sample Preparation: Soil samples are spiked with target contaminants (e.g., polyethylene, polyamide) at precisely defined concentrations ranging from 0.01% to 12%. Samples are homogenized and presented with consistent surface texture and particle distribution.

- Imaging Setup: Both sensor systems image identical sample sets under controlled illumination conditions using halogen lamps to ensure consistent spectral characteristics. The imaging geometry is standardized at 45° illumination and 0° viewing angles to minimize specular reflections.

- Spectral Calibration: Imaging systems are calibrated using a diffuse reflectance standard (typically PTFE or Spectralon) to convert raw sensor data to relative reflectance [18].

- Data Acquisition: Hyperspectral data cubes are collected using push-broom scanning with consistent spatial resolution across samples. Multiple exposures may be employed to extend dynamic range, particularly for InGaAs systems [18].

Data Processing and Analysis

- Spectral Extraction: Mean spectra are extracted from regions of interest corresponding to homogeneous areas of each sample concentration.

- Machine Learning Classification: Supervised classification algorithms (Support Vector Machines, Logistic Regression) are trained on spectral data using cross-validation techniques. Models are evaluated based on accuracy, precision, and recall metrics [19].

- Feature Selection: Wavelength selection algorithms identify diagnostically important spectral regions for contaminant identification, highlighting the value of extended spectral ranges.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for comparing MCT and InGaAs sensor performance in soil contaminant detection.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for SWIR Hyperspectral Soil Analysis

| Item | Function | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Target | Spectral calibration | PTFE tile or Spectralon; provides diffuse reflectance standard [18] |

| Illumination Source | Sample illumination | Halogen lamps with continuous spectrum; consistent 45° geometry [18] |

| Hyperspectral Imagers | Data acquisition | Push-broom style; MCT (1000-2500 nm) and/or InGaAs (800-1600 nm) [19] |

| Soil Samples | Analysis matrix | Representative soils; controlled moisture content; sieved for consistency |

| Contaminant Standards | Method validation | Pure polymer powders (PE, PA); precise concentration series [19] |

| Machine Learning Algorithms | Data analysis | SVM, Logistic Regression; cross-validation implementation [19] |

Application to Soil Contamination Assessment

Within the context of soil contamination assessment research, SWIR hyperspectral imaging enables several critical capabilities:

- Microplastic Identification: Both MCT and InGaAs systems can detect common microplastics like polyethylene and polyamide, but with significantly different accuracy levels (93.8% for MCT vs. 68.8% for InGaAs) [3]. MCT's extended spectral range captures detailed molecular absorption features beyond 1600 nm, providing more definitive identification of polymer types.

- Low-Concentration Detection: MCT sensors demonstrate superior sensitivity at trace contamination levels (0.01-0.1%), enabling detection of emerging contamination before reaching critical levels [3].

- Non-Destructive Analysis: Both technologies eliminate extensive sample preparation required by conventional methods (e.g., density separation, chemical digestion), enabling rapid screening of soil samples [19].

- Spatial Mapping: Hyperspectral imaging preserves spatial distribution information, allowing researchers to visualize contamination patterns and hotspots within soil samples.

Diagram 2: Sensor-specific pathways for soil contaminant detection showing performance differential.

The comparative analysis of MCT and InGaAs sensor technologies for SWIR hyperspectral imaging reveals a clear performance-sensitivity trade-off with significant implications for soil contamination assessment research.

MCT sensors provide superior detection accuracy (93.8% vs. 68.8%), enhanced sensitivity at low contamination levels, and more definitive material identification through their extended spectral coverage to 2500 nm. These advantages come at the cost of more complex cooling requirements and higher acquisition costs. For research requiring the highest sensitivity for emerging contaminants or precise polymer differentiation, MCT technology represents the optimal choice despite its cost and complexity.

InGaAs sensors offer a more accessible entry point for hyperspectral soil analysis with adequate performance for many applications. Their limitations in spectral range (typically to 1700 nm) restrict identification capability for materials with diagnostic features beyond this cutoff. For general soil screening applications or research with budget constraints, InGaAs technology provides a viable alternative, particularly when enhanced through multi-exposure techniques to extend dynamic range.

Future developments in both technologies will likely narrow this performance gap. Higher operating temperature MCT detectors will reduce cooling requirements, while extended-range InGaAs arrays may broaden spectral coverage. For now, the selection between these sensor technologies should be guided by specific research requirements: MCT for maximum sensitivity and identification certainty, InGaAs for cost-effective screening applications. This comparative analysis provides the experimental evidence necessary for researchers to make informed decisions validating hyperspectral imaging methodologies for soil contamination assessment.

Hyperspectral imaging (HSI) has emerged as a powerful, non-destructive technique for environmental monitoring, particularly for assessing soil contamination. Its ability to capture both spatial and spectral information in a single dataset makes it uniquely suited for identifying and quantifying pollutants, such as microplastics and heavy metals, in complex soil matrices [20]. However, the high-dimensional nature of hyperspectral data, characterized by hundreds of contiguous narrow bands, presents significant analytical challenges. Effectively interpreting this data requires sophisticated machine learning algorithms that can handle spectral redundancy, noise, and non-linear relationships.

This guide provides an objective comparison of three foundational algorithms in the spectral data scientist's toolkit: Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (PLS-DA), Random Forest (RF), and Support Vector Machine (SVM). We frame this comparison within the critical context of validating hyperspectral imaging for soil contamination assessment, a field where accuracy, robustness, and efficiency are paramount for researchers and environmental professionals [20] [7]. The performance of these algorithms is evaluated based on experimental data from recent peer-reviewed studies, focusing on their application to real-world analytical problems.

Experimental Protocols for Hyperspectral Classification

To ensure the reproducibility of results and provide a clear framework for comparison, this section details the standard experimental methodologies employed in the studies cited throughout this guide.

Hyperspectral Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The foundational step in any HSI analysis involves acquiring high-quality spectral data. Common protocols include:

- Sensor Selection: Studies often compare different sensors to optimize detection. For instance, research on soil microplastics has shown that Mercury Cadmium Telluride (MCT) sensors (1000–2500 nm) significantly outperform Indium Gallium Arsenide (InGaAs) sensors (800–1600 nm) for detecting low concentrations of polymers, due to their extended spectral coverage and higher sensitivity [7] [3].

- Sample Preparation: Soil samples are typically air-dried and sieved to minimize the effects of moisture and particle size on spectral measurements [21]. For microplastic detection, samples may be spiked with specific polymer types (e.g., polyethylene, polyamide) across a range of concentrations (e.g., 0.01% to 12%) to build calibration models [7].

- Spectral Transformations: Raw spectral reflectance is often transformed to enhance features and reduce scattering effects. Standard transformations include the First Derivative (FD), Standard Normal Variate (SNV), and Continuum Removal (CR) [21].

Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Selection

To mitigate the "curse of dimensionality" and reduce computational load, dimensionality reduction is a critical preprocessing step.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A linear technique that projects the data into a new coordinate system where the greatest variances lie along the first few axes (principal components) [21] [22].

- Minimum Noise Fraction (MNF): A transformation similar to PCA that orders components based on signal-to-noise ratio, which is particularly useful for hyperspectral data [23] [22].

- Feature Extraction: Algorithms like the Successive Projections Algorithm (SPA) can be used to select a subset of informative wavelengths from the full spectrum, thereby simplifying the model [20].

Model Training and Validation

Robust model validation is essential for assessing generalizability.

- Data Splitting: The dataset is typically divided into a training set (e.g., 70%) for model building and a testing set (e.g., 30%) for evaluating performance on unseen data [24].

- Cross-Validation: k-Fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) is widely used to tune model hyperparameters and prevent overfitting [24].

- Performance Metrics: Common metrics include Overall Accuracy (OA), F1-score (the harmonic mean of precision and recall), and Kappa coefficient [23].

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for a hyperspectral classification project, integrating the steps described above.

Hyperspectral Analysis Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard protocol from sample preparation to final classification.

Core Algorithm Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes the experimental performance of PLS-DA, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machine based on recent research in spectral classification for environmental assessment.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of PLS-DA, RF, and SVM in Spectral Classification Tasks

| Algorithm | Application Context | Reported Performance | Key Experimental Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| PLS-DA | Microplastic detection in soil & marine environments [20] | Near 100% sensitivity/specificity for particles ≥1 mm [20] | Effective when polymer types are limited and particle sizes are large; performance drops for complex matrices and smaller particles [20]. |

| Random Forest (RF) | Identification of invasive/expansive plant species [23] | F1-score > 0.9 (with 300 training pixels/class on 30 MNF bands) [23] | Less sensitive to small training sample sizes; maintains high accuracy even with reduced samples (e.g., F1-score drop of ~13 pp for 30-pixel samples) [23]. |

| Urban forest tree species identification [22] | Overall Accuracy (OA): 82.56% (Kappa = 0.81) [22] | Achieved the highest species-level accuracy (95% for some species) when used with PCA-transformed data [22]. | |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Soil free iron content estimation [21] | R²: 0.876 (Training), 0.803 (Testing) [21] | The best combination involved FD-transformed spectra and PCA for variable selection (FD + PCA + SVM) [21]. |

| Invasive species classification [23] | Comparable F1-score to RF (>0.9) with sufficient training data [23] | Noted for high stability and reliability, even with small training sets and noisy data [23]. | |

| Soil microplastic detection [7] | Key component in a model achieving 93.8% accuracy with an MCT sensor [7] | Used with linear and nonlinear kernels to analyze spectral features for detecting low-concentration microplastics [7]. |

Algorithm Strengths and Operational Characteristics

Beyond raw accuracy, the choice of an algorithm depends on its inherent characteristics and suitability for a given problem.

Table 2: Operational Characteristics and Comparative Profile of the Three Algorithms

| Characteristic | PLS-DA | Random Forest (RF) | Support Vector Machine (SVM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Linear supervised dimensionality reduction and classification [20]. | Ensemble of decision trees using bagging and random feature subsets [23] [22]. | Finds an optimal hyperplane to separate classes with maximum margin [25] [23]. |

| Handling of Non-Linearity | Limited; assumes linear relationships in the data. | Excellent; inherently models complex, non-linear interactions [25]. | Very good; can model non-linearity via kernel functions (e.g., RBF) [25] [23]. |

| Robustness to Noise & Overfitting | Moderate; can be affected by irrelevant variables. | High; ensemble approach reduces variance and overfitting [23]. | High; generalization is governed by the margin, making it robust [25] [23]. |

| Training Speed | Fast for high-dimensional data. | Fast to train; parallelizable [23]. | Can be slow for large datasets, depending on the kernel. |

| Interpretability | High; provides variable importance in projection (VIP) scores. | Moderate; provides feature importance metrics, but is an ensemble "black box" [25]. | Low; the "support vectors" are interpretable, but the model itself is often a black box. |

The diagram below visualizes the fundamental operational principles of each algorithm, highlighting their distinct approaches to classification.

Algorithm Operational Principles. This diagram contrasts the core classification mechanisms of PLS-DA, Random Forest, and SVM.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental protocols and high-performance results discussed are enabled by a suite of essential research reagents and tools. The following table details key components of a hyperspectral classification workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Hyperspectral Soil Analysis

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Representative Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hyperspectral Sensors | Captures spatial and spectral data as a hypercube. Critical choice dictates detectable features. | MCT (Mercury Cadmium Telluride): 1000-2500 nm; superior for microplastic detection [7] [3]. InGaAs (Indium Gallium Arsenide): 800-1600 nm; a common alternative [7]. |

| Preprocessing Algorithms | Corrects for noise, scatter, and baseline effects to extract meaningful spectral features. | Savitzky-Golay Filter: Smoothing and derivative calculation [24]. Standard Normal Variate (SNV): Scatter correction [21]. First Derivative (FD): Enhances subtle spectral features [21]. |

| Dimensionality Reduction Tools | Reduces data redundancy and computational cost while preserving critical information. | Principal Component Analysis (PCA): A linear workhorse for compression [21] [22]. Minimum Noise Fraction (MNF): Orders components by signal-to-noise ratio [23]. |

| Machine Learning Libraries | Software frameworks providing implementations of classification algorithms. | Scikit-learn (Python), Caret (R); provide PLS-DA, RF, and SVM implementations, along with tools for validation and hyperparameter tuning. |

| Validation Metrics | Quantifies model performance and generalizability to ensure reliable results. | F1-Score: Balances precision and recall for imbalanced data [23]. Kappa Coefficient: Measures agreement between classification and ground truth, correcting for chance [22]. |

The accurate assessment of soil contamination is a critical challenge in environmental science. Advanced deep learning architectures applied to hyperspectral imaging (HSI) data are proving to be powerful tools for this task. This guide provides a comparative analysis of two prominent approaches: the specialized one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (1D-CNN) for spectral feature extraction, and the hybrid HyperSoilNet framework, which integrates deep learning with traditional machine learning. Performance evaluations on public benchmarks reveal that the 1D-CNN can achieve high classification accuracy, while the more complex HyperSoilNet demonstrates superior performance in the regression-based estimation of specific soil properties [26] [1].

Table 1: Architectural Comparison of 1D-CNN and HyperSoilNet

| Feature | 1D-CNN | HyperSoilNet |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | One-dimensional convolutional layers [26] | Hybrid: Hyperspectral-native CNN backbone + ML ensemble [1] |

| Primary Input | Pixel-wise spectral data [26] | Hyperspectral imagery cubes [1] |

| Key Strength | Extracting deep-level spectral features [26] | Combines deep representation learning with ML robustness [1] |

| Typical Output | Land cover/contamination class [26] | Estimated values of soil properties (e.g., pH, nutrients) [1] |

| Spatial Context | Can be incorporated via augmented input vectors [26] | Inherently models spatial-spectral features [1] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison

| Model | Dataset | Key Metric | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1D-CNN with Augmented Input | Salinas Valley (Agriculture) | Overall Accuracy | 99.8% [26] |

| 1D-CNN with Augmented Input | Indian Pines (Mixed Vegetation) | Overall Accuracy | 98.1% [26] |

| HyperSoilNet | HyperView Challenge (Soil Properties) | Leaderboard Score | 0.762 [1] |

In-Depth Architectural Analysis

1D Convolutional Neural Networks (1D-CNN)

The 1D-CNN is designed to process the spectral signature of each pixel in a hyperspectral image as a one-dimensional vector. Its architecture is fundamentally geared toward extracting hierarchical spectral features [26].

A standard implementation, as demonstrated in classification tasks for agricultural and mixed vegetation terrains, involves a sequence of convolutional blocks. Each block typically contains a 1D convolutional layer (conv-1D), which applies multiple filters to the input spectrum to detect local spectral patterns. This is followed by Batch Normalization (BN), which stabilizes and accelerates the learning process by normalizing the outputs from the previous layer. A Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) activation function then introduces non-linearity, allowing the network to learn complex relationships. Finally, a max-pooling layer downsamples the feature maps, reducing computational load and providing a form of translational invariance [26]. These blocks are followed by fully connected layers that perform the final classification, often using a softmax function [26].

To improve accuracy, the input can be augmented from a single pixel's spectrum to include spatial-spectral features. This is achieved by extracting the first few Principal Components (PCA) from the surrounding pixels of a target pixel and concatenating them with the target's original spectral vector. This augmented input provides the 1D-CNN with crucial spatial context, significantly boosting classification performance [26].

Figure 1: 1D-CNN workflow for soil classification, showing the spectral-spatial feature augmentation process and sequential convolutional blocks.

HyperSoilNet: A Hybrid Deep Learning Framework

HyperSoilNet represents a modern hybrid paradigm designed to tackle the challenges of soil property estimation from HSI. It synergistically combines the strengths of deep learning and traditional machine learning to achieve robust performance, especially with limited labeled data [1].

The framework is built on a hyperspectral-native CNN backbone. This deep learning component acts as a powerful feature extractor, processing the raw hyperspectral data to learn a compact, informative representation of the spectral-spatial patterns relevant to soil properties. To mitigate overfitting on small datasets, the CNN backbone is often pretrained using a self-supervised contrastive learning scheme. This pretraining phase allows the model to learn robust feature representations from unlabeled HSI data by pulling together different augmented views of the same sample and pushing apart views from different samples [1].

Instead of using a simple output layer for regression, HyperSoilNet employs a machine learning ensemble (e.g., carefully optimized regressors like Random Forest or Gradient Boosting) as the final predictor. The features extracted by the CNN backbone are fed into this ML ensemble, which then estimates the target soil properties such as potassium oxide (K₂O), phosphorus pentoxide (P₂O₅), magnesium (Mg), and soil pH [1]. This hybrid approach provides a form of regularization, where the deep model transforms the high-dimensional input, and the downstream ML ensemble reduces overfitting through averaging and other constraints [1].

Figure 2: HyperSoilNet hybrid framework, illustrating the combination of a CNN feature extractor with a traditional ML ensemble for regression.

Experimental Protocols and Performance

Key Experimental Setups

The performance of HSI models is highly dependent on rigorous experimental protocols. The following methodologies are derived from benchmark studies.

1D-CNN for Land Cover Classification

- Datasets: Models are frequently trained and validated on public benchmarks like the Indian Pines and Salinas Valley datasets. These contain HSI data of agricultural and mixed vegetation scenes with corresponding ground truth labels [26].

- Input Preparation: For pixel-wise classification, the spectral vector of each pixel is used. For enhanced performance, an augmented input vector is created by concatenating the pixel's spectrum with the first Q Principal Components (PCA) from an R x R pixel neighborhood around it [26].

- Training: The 1D-CNN, composed of consecutive conv-BN-ReLU-pooling blocks, is trained using the cross-entropy loss function and a mini-batch optimization algorithm (e.g., Adam). Batch Normalization is critical for stabilizing learning [26].

- Evaluation: Performance is primarily measured by Overall Accuracy (OA), which calculates the percentage of correctly classified test pixels across all classes [26].

HyperSoilNet for Soil Property Estimation

- Dataset: The model is evaluated on the HyperView Challenge dataset, which focuses on estimating key soil parameters from satellite-based HSI [1].

- Framework Training: The CNN backbone is first pretrained in a self-supervised manner on a large collection of unlabeled HSI data to learn robust spectral-spatial features. Subsequently, the backbone is integrated with the ML ensemble, and the entire hybrid pipeline is fine-tuned on the labeled soil data [1].

- Evaluation: Model performance is assessed using a specific leaderboard score (achieving 0.762 on the HyperView challenge) and validated through comprehensive ablation studies to understand the contribution of each framework component [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Tools for Hyperspectral Soil Contamination Analysis

| Tool / Solution | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Airborne Visible/Infrared Imaging Spectrometer (AVIRIS) | A standard sensor for acquiring research-grade hyperspectral data, used in foundational datasets like Indian Pines [26]. |