Validating Laser Cleaning Effectiveness on Optical Surfaces: Protocols for Precision and Performance

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists validating laser cleaning technologies for sensitive optical surfaces.

Validating Laser Cleaning Effectiveness on Optical Surfaces: Protocols for Precision and Performance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and scientists validating laser cleaning technologies for sensitive optical surfaces. It covers the foundational physics of laser-material interactions, detailed methodologies for application, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing processes, and rigorous validation techniques. By synthesizing current research and experimental data, this guide aims to establish reliable protocols for implementing laser cleaning in biomedical and clinical research environments where optical component integrity is paramount.

Laser-Optics Interaction: Principles and Contaminant Removal Mechanisms

Fundamentals of Laser Ablation and Energy Absorption Dynamics

Laser ablation, the process of removing material from a surface using focused laser energy, has emerged as a critical technology for precision cleaning, particularly for sensitive optical components. This process is governed by the fundamental dynamics of energy absorption, where laser energy is transferred to the target material, leading to rapid heating, vaporization, and ejection of contaminants without damaging the underlying substrate. Within the context of validating laser cleaning effectiveness on optical surfaces, understanding these core mechanisms is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals who rely on impeccably clean optical systems for analytical instrumentation, imaging, and diagnostic equipment.

The validation of laser cleaning processes requires a thorough comparison against alternative methods across multiple parameters, including cleaning efficacy, surface preservation, and operational practicality. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these technologies, with a specific focus on their application to optical surfaces, to support scientific decision-making and process optimization in research and development environments.

Core Mechanisms of Laser Ablation

Physical Principles of Laser-Material Interaction

Laser ablation operates on the principle of selective energy absorption. When a high-energy laser beam is directed onto a contaminated surface, the contaminant layer (e.g., rust, organic film, or particulate matter) absorbs the laser energy far more efficiently than the underlying optical substrate. This selective absorption causes the contaminant to undergo rapid heating and vaporization—a process known as laser ablation—effectively removing it from the surface [1]. The process depends critically on several factors:

- Laser Parameters: Wavelength, pulse duration, fluence (energy per unit area), and repetition rate are tuned to maximize absorption by the contaminant while minimizing interaction with the substrate [1].

- Material Properties: The optical and thermal properties of both the contaminant and the substrate determine the efficiency of energy transfer and the subsequent material removal [2].

- Ablation Regimes: The specific mechanism of material removal can vary. For ultrashort (femtosecond to picosecond) laser pulses, material ejection can be driven by photomechanical effects (spallation) due to stress confinement. At higher fluences, the process can transition to a "phase explosion," where the superheated material undergoes explosive decomposition into vapor and liquid droplets [2].

Advanced Dynamics and Experimental Visualization

The fundamental dynamics of laser ablation involve highly non-equilibrium states of matter. Time-resolved studies using techniques like pump-probe microscopy have revealed that following ultrafast laser excitation, materials can undergo melting and amorphization before the onset of ablation [3]. The ablation plume itself exhibits complex nanoscale density heterogeneities during expansion, which are signatures of the specific phase decomposition processes at work [2].

Cutting-edge imaging techniques are crucial for validating these dynamics. For instance, a dual-modal ultrafast microscopy system that combines two-dimensional reflectivity and three-dimensional topography imaging has achieved impressive spatiotemporal resolutions of 236 nm and 256 fs. This system can successfully examine the dynamics of laser-induced periodic surface structure formation, strengthening, and erasure on silicon surfaces, providing a robust tool for the comprehensive analysis of ablation dynamics [3].

Comparative Analysis of Surface Cleaning Methodologies

Laser Ablation vs. Traditional Cleaning Methods

The following table provides a structured comparison of laser ablation against other prevalent surface cleaning techniques, with a focus on parameters critical for optical surface processing.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Surface Cleaning Technologies

| Parameter | Laser Ablation/Cleaning | Sandblasting | Chemical Cleaning | Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning Mechanism | Photothermal/Photomechanical ablation vaporizes contaminants [1]. | High-pressure abrasive particles physically remove contaminants [4]. | Chemical reactions dissolve or break down contaminants [5]. | Reactive ions and radicals chemically etch and volatilize organics [6]. |

| Precision | High (suitable for sub-millimeter features) [4]. | Low (difficult to control on small areas) [4]. | Low to Medium | High (uniform, large-area processing) [6]. |

| Surface Contact | Non-contact [5]. | Contact [5]. | Contact (typically immersion) | Non-contact [6]. |

| Substrate Damage Risk | Very Low (when parameters are optimized) [1]. | High (can cause pitting and erosion) [1]. | Medium (potential for chemical etching) | Very Low (non-destructive to coatings) [6]. |

| Environmental Impact | Low (no chemicals, minimal waste) [5] [1]. | High (airborne dust, spent media) [4] [1]. | High (hazardous waste streams) [5] | Low (gas-based, no liquid waste) [6]. |

| Typical Applications | Precision cleaning of delicate optics, electronics, historical artifacts [5] [4]. | Heavy-duty rust removal on large structural components [4] [1]. | General degreasing, wafer cleaning. | In-situ cleaning of large-aperture optical components in vacuum systems [6]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental studies provide quantitative data on the effectiveness of different cleaning methodologies. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent research, which are essential for validating process effectiveness.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Cleaning Studies

| Study Focus | Cleaning Method | Key Experimental Parameters | Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid-assisted laser rust removal on Q235 steel [7] | Combined continuous & nanosecond pulsed laser | Water layer thickness: 0.25-1.0 mm; Laser energy density: Varied. | Liquid layer effectively reduced thermal damage to substrate; Optimal rust removal efficiency achieved with specific water layer thickness. |

| Organic contaminant removal from optical coatings [6] | Low-Pressure Oxygen Plasma | Discharge power and gas pressure varied; Plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature measured. | Effectively restored surface morphology and enhanced optical transmittance; Recovered laser-damage resistance of components. |

| Predicting laser-induced surface modifications [8] | Nanosecond Nd:YAG Pulsed Laser | Wavelength: 532 nm; Pulse Width: 4.4 ns; Laser Intensity: 1.6×10^6 to 1.61×10^10 W/cm². | A hybrid deep learning model (CNN-MLP) achieved >99% accuracy in predicting surface modification. |

| Laser ablation of gold films [2] | Femtosecond Laser Pulses | Pulse Duration: 50 fs; Laser Fluence: Up to 6.3 J/cm². | Time-resolved X-ray probing mapped the evolution of nanoscale density heterogeneities in the ablation plume. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol for Liquid-Assisted Laser Cleaning of Metallic Surfaces

This protocol, based on the study of Q235 steel, outlines the process for evaluating the efficacy of liquid-assisted laser cleaning in reducing thermal damage [7].

- Sample Preparation: Prepare substrate samples (e.g., 30x30 mm Q235 steel plates). Induce corrosion artificially by placing them in a humid environment and spraying with 6% NaCl solution every 12 hours for 15 days.

- Liquid Film Application: Apply a uniform layer of pure water over the rusted surface. The thickness of this layer (e.g., 0.25 mm, 0.5 mm, 0.75 mm, 1.0 mm) is a critical variable.

- Laser Setup and Calibration: Employ a combined laser system (continuous wave and nanosecond pulsed laser). Precisely calibrate the laser energy density and the delay between the two laser pulses.

- Processing: Irradiate the sample surface through the water layer with the combined laser beam.

- Post-Processing Analysis:

- Surface Morphology: Characterize the cleaned surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to assess rust removal efficiency and surface roughness.

- Thermal Damage Assessment: Analyze cross-sections for any evidence of heat-affected zones or microstructural changes in the substrate.

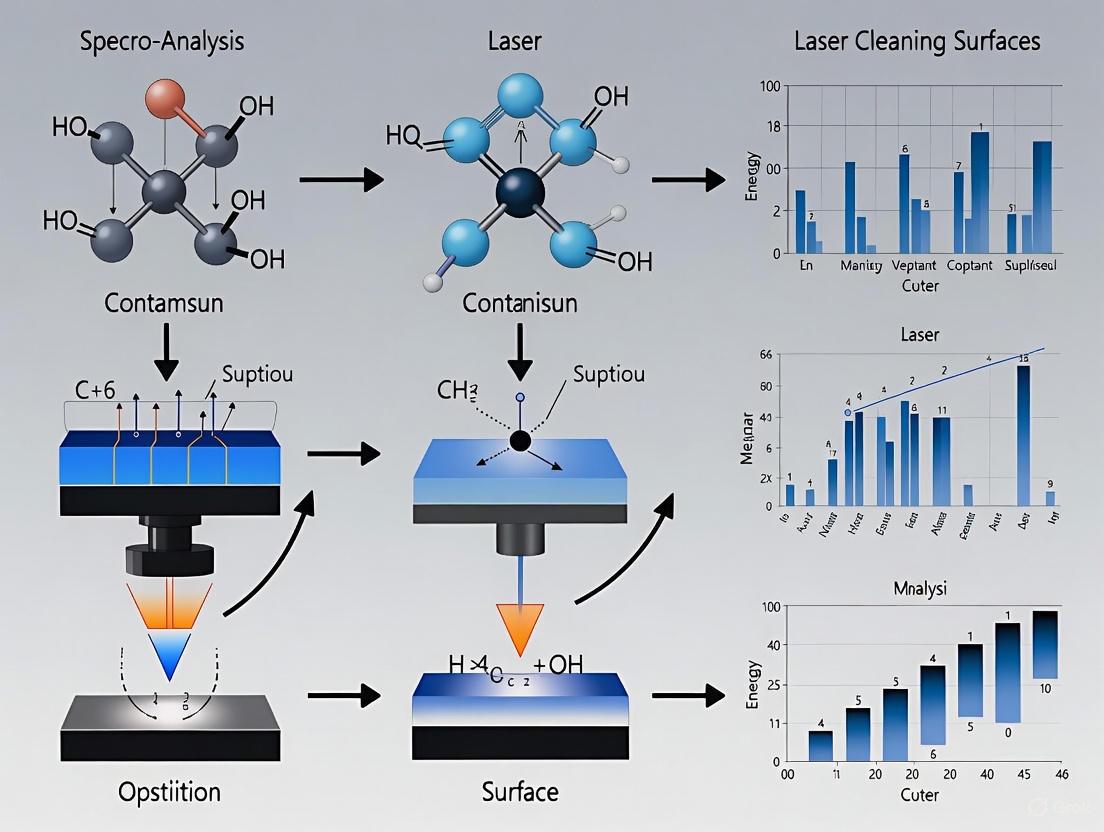

The workflow for this experimental validation is summarized in the diagram below:

Protocol for Plasma Cleaning of Optical Components

This protocol details the methodology for in-situ plasma cleaning of large-aperture optical components with chemical coatings, as used in intense laser systems [6].

- Sample Preparation: Use dip-coating methods to prepare chemical-coated fused silica samples (e.g., sol-gel SiO₂ anti-reflective coatings).

- Contaminant Application: Artificially deposit a uniform layer of organic contaminants onto the coating surface.

- Plasma Reactor Setup: Place the contaminated optical component inside a low-pressure plasma chamber. Use a capacitive-coupling discharge model.

- Process Parameter Optimization:

- Use a Langmuir probe to characterize plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature.

- Adjust core parameters like discharge power and oxygen/argon gas pressure to establish the optimal process window.

- Plasma Treatment: Expose the optical component to the low-pressure plasma for a defined duration.

- Effectiveness Analysis:

- Optical Performance: Measure the transmittance of the optical component at the target wavelength (e.g., 355 nm) to quantify recovery.

- Surface Analysis: Use techniques like X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to verify the removal of organic functional groups.

- Laser Damage Threshold Testing: Measure the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) to confirm the restoration of optical strength.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For researchers designing experiments to validate laser ablation and other cleaning techniques, the following tools and materials are fundamental.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Cleaning Validation

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nanosecond/Picosecond Pulsed Lasers | Provides high peak power for efficient ablation with controlled thermal input. | Laser-induced surface modification studies; rust removal [8] [7]. |

| Sol-Gel Chemical Coatings | Represents functional optical coatings (anti-reflective, high-reflective) on substrates. | Serving as test samples for cleaning studies on optical components [6]. |

| Low-Pressure Plasma Reactor | Generates reactive ions and radicals for gentle, non-contact cleaning of sensitive surfaces. | In-situ removal of organic contaminants from large-aperture optics [6]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Provides high-resolution imaging for qualitative assessment of surface morphology pre- and post-cleaning. | Evaluating rust removal efficiency and surface topography [7]. |

| Langmuir Probe | Diagnoses plasma parameters (density, temperature) critical for process optimization. | Characterizing plasma discharge in plasma cleaning experiments [6]. |

| Spectrophotometer | Quantifies the optical transmittance/reflectance of coated optics to measure cleaning performance. | Assessing the recovery of optical performance after cleaning [6]. |

The validation of laser cleaning effectiveness on optical surfaces is a multi-faceted process that requires a deep understanding of laser ablation fundamentals and a rigorous, comparative approach to performance assessment. As the experimental data and comparisons in this guide demonstrate, laser ablation offers a unique combination of precision, non-contact operation, and minimal substrate damage, making it highly suitable for delicate optical surfaces. However, alternative methods like low-pressure plasma cleaning present a compelling, equally non-destructive solution for specific applications, such as the in-situ cleaning of large optical components in vacuum systems.

The choice of an optimal cleaning technology must be guided by the specific requirements of the optical component—including the nature of the contaminant, the sensitivity of the substrate, and the required level of cleanliness. The experimental protocols and toolkit outlined herein provide a foundation for researchers and scientists to conduct their own validations, ensuring that the integrity and performance of critical optical systems are maintained to the highest standards.

Laser cleaning has emerged as a critical, non-contact process for maintaining optical surfaces, with its effectiveness heavily dependent on the precise selection of operational parameters. For researchers and scientists, particularly in fields like drug development where contamination control is paramount, understanding the interplay between wavelength, pulse duration, and power density is essential for validating cleaning protocols that are both effective and non-damaging. This guide objectively compares the performance of different laser parameter sets, supported by experimental data, to provide a framework for optimizing cleaning processes for sensitive optical components.

Core Laser Parameters and Their Impact on Cleaning

Laser cleaning performance is governed by the fundamental interaction between laser light and the contaminant or coating material. The three parameters below form the cornerstone of any effective laser cleaning protocol.

Wavelength: The wavelength of the laser determines how energy is absorbed by the material. A wavelength of 1064 nm, common in fiber lasers, is highly absorbed by metals and many contaminants, making it a industry standard for industrial cleaning tasks [9]. For detecting trace residues in pharmaceutical manufacturing, deep UV spectroscopy systems utilize specific ultraviolet wavelengths to excite and quantify molecules without contact [10].

Pulse Duration: This parameter dictates the temporal nature of the energy delivery and is critical for controlling thermal effects.

- Nanosecond (ns) pulses can lead to significant thermal diffusion, which may damage the underlying substrate [11].

- Femtosecond (fs) pulses provide extremely short, high-intensity energy bursts. This confines energy absorption to the target contaminant, minimizing heat transfer to the substrate and enabling ultra-precise, non-thermal ablation, which is ideal for delicate optical surfaces [11].

Power Density (or Fluence): Power density, often expressed as energy per unit area (J/cm²), is the decisive factor for the cleaning outcome. If the fluence is below the removal threshold of the contaminant, cleaning will be ineffective. Conversely, fluence above the damage threshold of the substrate will cause irreversible harm. Successful cleaning occurs in the window between these two thresholds. For instance, a fluence of 2.17 J/cm² from a femtosecond laser has been shown to effectively remove 15 µm polystyrene microbeads without damaging a glass substrate [11].

Comparative Performance Analysis of Laser Parameters

The tables below synthesize data from recent research to compare how different parameter combinations influence cleaning effectiveness and safety across various applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Laser Pulse Duration Regimes for Cleaning

| Pulse Duration | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Femtosecond (fs) | Primarily non-thermal ablation, minimal heat diffusion [11] | High precision; minimal substrate damage; suitable for thermally sensitive materials [11] | Higher equipment cost; process complexity | Heritage restoration; wafer cleaning; sensitive optical surfaces [11] |

| Nanosecond (ns) | Photothermal and photochemical effects; some thermal diffusion [11] | Proven, robust technology; cost-effective for many industrial uses | Risk of thermal damage to substrate; reduced precision [11] | Rust, paint, and oxide removal from robust components [11] |

Table 2: Experimental Laser Parameters and Outcomes from Recent Studies

| Study Objective | Optimal Parameters | Key Performance Outcomes | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaning 15 µm microbeads from glass | • Wavelength: 1030 nm• Pulse Duration: 190 fs• Fluence: 2.17 J/cm² | Effective contaminant removal with minimal energy use and no substrate damage. Enabled by real-time deep learning control. | [11] |

| Paint layer removal from Al alloy | • Laser Power: 291 W• Scanning Speed: 8425 mm/s• Frequency: 166 kHz | Achieved controlled paint removal with a post-cleaning surface roughness error range of -0.573 µm to -0.419 µm. | [12] |

| LDED coating of FeCoNi+Y₂O₃ | • Laser Power: 706.8 W• Scanning Speed: 646.2 mm/min• Powder Feed: 12 g/min | Reliable regression model for cladding morphology (dilution rate error: 7.36%; width-to-height ratio error: 10.03%). | [13] |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Laser Cleaning

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of laser cleaning processes, a structured experimental methodology is crucial. The following protocol, based on the Response Surface Methodology (RSM), provides a robust framework for optimization.

Experimental Design and Setup

- Material Preparation: The substrate (e.g., an Al alloy sample with a composite paint layer [12] or a 316L stainless steel substrate [13]) is prepared and cleaned. Contaminants or coatings are applied uniformly to ensure consistent test conditions.

- System Configuration: The laser cleaning system typically includes a pulsed laser source, galvanometer scanners for beam steering, a motion control stage, and process gas or vacuum extraction [12]. In advanced setups, a real-time monitoring system like a CMOS camera is integrated for feedback [11].

Optimization via Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

RSM is a statistical technique that fits a multivariate regression equation to experimental data to model and optimize process parameters [13] [12].

- Define Input Variables and Responses: Key laser parameters (e.g., Laser Power, Scanning Speed, Repetition Frequency) are chosen as input variables. The output responses are quantifiable quality metrics such as paint removal thickness, surface roughness (Ra), or dilution rate [13] [12].

- Experimental Design: A Box-Behnken Design (BBD) is often employed, which efficiently explores the multi-parameter space with a reduced number of experimental runs [13].

- Model Validation: A regression model is established, and its reliability is assessed through Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). The model is then used to predict optimal parameter sets, which are finally validated through confirmation experiments [12].

Real-Time Monitoring and Advanced Control

For the highest precision, a closed-loop system can be implemented. One study demonstrated this by integrating a conditional Generative Adversarial Network (cGAN). This neural network takes a camera image of the surface before a laser pulse and predicts the outcome after the pulse. This prediction is used in a real-time feedback loop to tailor the laser's position and energy for selective cleaning, drastically improving precision and efficiency [11].

The workflow for this optimized, data-driven approach is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Laser Cleaning Research and Validation

| Material/Component | Function in Research Context | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Polystyrene Microbeads | A standardized model contaminant for developing and validating high-precision cleaning processes due to uniform size and properties [11]. | 15 µm diameter beads on a glass slide to simulate contaminants [11]. |

| Composite Paint Layers | A representative challenging coating system for studying controlled, layered removal from alloy substrates [12]. | Al alloy substrate with polyurethane topcoat and epoxy primer [12]. |

| High-Entropy Alloy (HEA) Powders | Used in coating formation studies (e.g., via LDED) to understand how laser parameters affect the morphology of deposited functional coatings [13]. | FeCoNi alloy powder mixed with Y₂O3 for oxide dispersion strengthening [13]. |

| Trace Chemical Detector | Validates cleaning effectiveness by detecting residual contamination on surfaces at trace levels, crucial for pharmaceutical and optical applications [10]. | Deep UV instrument (e.g., TraC) for non-contact detection of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) [10]. |

Key Insights for Research Applications

The research and data lead to several critical conclusions for professionals validating laser cleaning on optical surfaces:

- Pulse Duration is Paramount for Delicate Surfaces: For cleaning where substrate integrity is non-negotiable, femtosecond lasers are superior. Their ultrashort pulses ablate material with negligible thermal damage, making them the tool of choice for critical optical components and in R&D for high-precision industries [11].

- Validation Requires a Multi-Faceted Approach: Relying on a single metric is insufficient. A robust validation protocol must combine physical metrics (e.g., roughness, removal thickness) with chemical detection methods (e.g., deep UV spectroscopy) to confirm both macroscopic and microscopic cleanliness [10] [12].

- Systematic Optimization is a Force Multiplier: The Response Surface Methodology provides a powerful, data-driven framework for moving beyond trial-and-error. It efficiently maps the complex relationships between multiple laser parameters and cleaning outcomes, ensuring reliable and reproducible results [13] [12].

- The Future is Adaptive and Automated: The integration of deep learning with real-time monitoring represents the cutting edge. This technology enables a self-correcting cleaning process that can adapt to varying contaminant thickness and type, ensuring optimal photon usage and guaranteeing results [11].

In high-power laser systems and precision optical applications, surface contaminants are not merely a nuisance; they are a primary factor limiting performance and longevity. Organic films, particulate matter, and other surface adherents can dramatically reduce laser-induced damage thresholds (LIDT), leading to catastrophic failures in critical optical components. Studies have demonstrated that contamination on optical component surfaces can induce damage spots five times the size of the contaminants themselves under intense laser irradiation, reducing the LIDT by approximately 60% [6]. As optical systems advance toward higher powers and greater precision, understanding and validating contaminant-specific removal mechanisms has become a fundamental research imperative.

This guide objectively compares the performance of laser cleaning against alternative technologies, with a specific focus on mechanistic actions across different contamination types. We present experimental data and protocols to provide researchers with a rigorous framework for selecting and validating cleaning approaches based on specific contamination challenges, particularly for sensitive optical surfaces where preservation of substrate integrity is paramount.

Fundamental Cleaning Mechanisms: A Comparative Analysis

Cleaning technologies operate through distinct physical principles that determine their effectiveness against different contamination types. The three primary mechanisms are laser thermal ablation, laser-induced stress waves, and plasma-based chemical reactions.

Laser Thermal Ablation Mechanism

Laser thermal ablation removes contaminants through rapid vaporization. When a pulsed laser beam irradiates a surface, the contaminants absorb laser energy, and their temperature rises instantly. If the energy exceeds the contaminant's vaporization threshold, it undergoes instant phase change, leading to removal [14]. The process is governed by the laser energy density, which must be carefully controlled to sit between the ablation threshold of the contaminant and that of the underlying substrate [14]. This mechanism is highly effective for organic films and coatings.

Laser Thermal Stress Mechanism

This mechanism utilizes stress effects rather than thermal ablation. A short pulsed laser causes rapid, localized heating and thermal expansion of either the contaminant or the substrate. This generates a thermoelastic stress wave that propagates and displaces the contaminant when the resulting lifting force exceeds the adhesion force (typically van der Waals forces) [14]. The one-dimensional heat conduction equation can be expressed as:

[ \rho c \frac{\partial T(z,t)}{\partial t} = \lambda \frac{\partial^2 T(z,t)}{\partial z^2} + \alpha I_0 A e^{-A z} ]

Where ( \rho ) is density, ( c ) is specific heat, ( \lambda ) is thermal conductivity, ( \alpha ) is absorptivity, ( I_0 ) is laser intensity, and ( A ) is the absorption coefficient [14]. This mechanism is particularly effective for removing particulate contaminants without damaging the substrate.

Plasma Surface Interaction Mechanism

Low-pressure plasma cleaning operates on different principles, using ionized gas (typically oxygen or argon) to remove contaminants. The ionized gas generates reactive species (ions, electrons, radicals) that interact with organic contaminants, breaking them down into volatile compounds through chemical reactions and physical sputtering [6]. Reactive molecular dynamics (RMD) simulations have revealed that oxygen plasma removes organic films via radical-driven pathways, effectively restoring optical performance [6].

Figure 1: Laser and Plasma Cleaning Mechanisms. This diagram illustrates the fundamental physical processes through which different cleaning technologies interact with and remove surface contaminants.

Technology Performance Comparison

Quantitative Cleaning Efficiency Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cleaning Technologies for Different Contaminant Types

| Contaminant Type | Cleaning Technology | Key Performance Metrics | Optical Surface Impact | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic Films(Photoresist, oils) | KrF Excimer Laser(λ=248 nm) | Ablation rate: 0.09 μm/pulse at 0.3 J/cm²; Complete removal possible with optimized pulses [15] | Minimal substrate damage with proper parameter control; Can restore near-baseline transmittance | Potential for chemical residue; Requires precise fluence control |

| Low-Pressure Oxygen Plasma | Removes realistic organic films via radical-driven pathways; Restores optical performance [6] | Non-destructive to coatings; High uniformity (~80%) [6] | Slower process; Requires vacuum chamber | |

| Solvent Cleaning | Effective for most organic contaminants [16] | Risk of solvent residue causing hazing or further contamination | Environmental and health concerns; Chemical disposal issues | |

| Particulates(Sub-micron particles) | Steam Laser Cleaning(with liquid film) | Highly effective for micron to sub-micron particles; Explosive vaporization generates removal forces [17] | Gentle on delicate substrates when optimized | Requires precise liquid film deposition |

| Dry Laser Cleaning(UV laser) | Effective for particulate removal [17] | Non-contact process | Less effective than steam-enhanced method | |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning | Effective for larger particles [14] | May cause damage to delicate optical coatings | Ineffective for sub-micron particles; Can drive particles into surfaces | |

| Paint & Coatings(Composite layers) | Pulsed Fiber Laser(λ=1064 nm) | Removal depth proportional to pulse overlap; Multiple mechanisms coupled: ablation, plasma impact, thermal stress [18] | Selective removal possible with parameter optimization; Risk of substrate damage if over-exposed | Complex parameter optimization required for multilayer systems |

| Mechanical Abrasive(Sandblasting) | Fast removal rate for thick coatings [16] | High probability of surface and substrate damage; Creates secondary contamination | Low precision; Generates dust and debris | |

| Rust & Oxides(Surface corrosion) | Fiber Laser(λ=1064 nm) | Effective removal at 0.41-8.25 J/cm²; Below 0.41 J/cm² ineffective, above 8.25 J/cm² causes damage [14] | Can clean without damaging underlying metal substrate | Narrow processing window for sensitive applications |

Operational Characteristics and Process Considerations

Table 2: Operational Parameters and Practical Implementation Factors

| Parameter | Laser Cleaning | Plasma Cleaning | Traditional Methods(Chemical, Mechanical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | Thermal ablation, stress waves, plasma shock [14] | Radical-driven chemical reaction, physical sputtering [6] | Chemical dissolution or mechanical displacement |

| Selectivity | High - Precise targeting possible [19] | Medium - Treats entire chamber volume | Low - Broad application |

| Substrate Damage Risk | Low to Medium (with parameter optimization) [18] | Very Low - Non-destructive to coatings [6] | High - Chemical etching or abrasive damage |

| Environmental Impact | Low - No chemicals required [19] | Medium - May require gas handling | High - Solvent waste, media disposal [16] |

| Process Speed | Fast (cm²/min scale) [19] | Slow (minutes to hours) [6] | Variable - Often requires additional steps |

| Capital Cost | High | Medium | Low to Medium |

| Operational Complexity | High - Parameter optimization critical | Medium - Vacuum systems required | Low - Established procedures |

| In-situ Capability | Possible with fiber delivery | Limited by chamber requirements | Generally limited |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Laser Cleaning Validation for Organic Films on Optical Surfaces

Objective: Quantitatively validate the effectiveness of laser cleaning for removing standardized organic contaminants from coated optical surfaces while preserving anti-reflective (AR) or high-reflective (HR) coating integrity.

Sample Preparation:

- Substrate: Fused silica with sol-gel SiO₂ AR coatings at 355 nm wavelength [6]

- Contaminant Application: Spin-coating of photoresist (PFR 7790G) to ~1.2 μm thickness [15]

- Contamination Standardization: Use calibrated thickness measurements via profilometry to ensure uniform contaminant layers

Laser Parameters:

- Laser Type: KrF Excimer Laser (λ = 248 nm) [15]

- Fluence Range: 0.1-0.3 J/cm² (below coating damage threshold) [15]

- Pulse Repetition: 10-50 Hz

- Spot Size: 1-5 mm diameter with beam homogenizer

- Number of Pulses: Varied from 10-100 pulses

Characterization Methods:

- Ablation Depth: Profilometry measurements after single and multiple pulses [15]

- Surface Quality: White-light interferometry for surface roughness

- Coating Integrity: Laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) testing pre- and post-cleaning

- Chemical Residue: FTIR spectroscopy for detection of organic residues [20]

Validation Metrics:

- Cleaning efficiency calculated as (initial thickness - final thickness)/initial thickness × 100%

- LIDT maintenance >95% of pristine coating value

- Surface roughness change < ±10% from baseline

Plasma Cleaning Protocol for Sensitive Optical Components

Objective: Evaluate low-pressure oxygen plasma efficiency for removing organic contamination from large-aperture optical components without degradation of optical performance.

Experimental Setup:

- Plasma System: Low-pressure RF capacitive coupling discharge [6]

- Process Gases: Oxygen (90%) and Argon (10%) mixture

- Operating Pressure: 50-200 mTorr

- RF Power: 100-500 W

- Treatment Duration: 15-90 minutes

Diagnostic Methods:

- In-situ Plasma Characterization: Langmuir probe for plasma potential, ion density, electron temperature [6]

- Optical Emission Spectroscopy: Identification of reactive species in plasma

- Transmittance Measurement: Quantitative relationship between functional groups and optical transmittance [6]

- Surface Analysis: XPS for chemical composition changes

Validation Approach:

- Establish quantitative correlation between plasma parameters and cleaning effectiveness

- Use reactive molecular dynamics (RMD) simulations to model plasma-contaminant interactions [6]

- Compare experimental results with simulation predictions for mechanism verification

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Materials and Equipment for Cleaning Validation Studies

| Category | Item | Specification/Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized Contaminants | Photoresist (PFR 7790G) | Mixture of ethyl lactate, Novalac resin, naphthoquinone diazide ester; forms uniform ~1.2μm films [15] | Organic film removal studies |

| Sol-gel SiO₂ coatings | 29nm particle size, anti-reflective at 355nm [6] | Optical substrate simulation | |

| Laser Systems | KrF Excimer Laser | λ=248nm, short pulse duration for photochemical breaking of molecular bonds [15] | Organic contaminant ablation studies |

| Pulsed Fiber Laser | λ=1064nm, high repetition rate, adjustable pulse overlap [18] | Paint removal, industrial applications | |

| Analytical Instruments | Langmuir Probe | Measures plasma potential, ion density, electron temperature [6] | Plasma characterization |

| Profilometer | Measures ablation depth and surface topography [15] | Cleaning efficiency quantification | |

| FTIR Spectrometer | Detects organic functional groups and residues [20] | Chemical residue analysis | |

| White-light Interferometer | Measures surface roughness at nanometer scale | Substrate damage assessment | |

| Plasma Systems | RF Capacitive Coupling Discharge | Low-pressure system for uniform, diffuse plasma generation [6] | Gentle cleaning of sensitive optics |

| Simulation Tools | Reactive Force Field (ReaxFF) MD | Models atomic-scale reaction pathways of plasma-surface interactions [6] | Mechanism investigation at nanoscale |

Figure 2: Contaminant-Specific Cleaning Validation Workflow. This decision framework guides researchers in selecting and validating appropriate cleaning methods based on contaminant characteristics and performance requirements.

The validation of contaminant-specific removal mechanisms provides a critical foundation for selecting appropriate cleaning technologies for optical applications. Laser cleaning offers distinct advantages in precision, controllability, and environmental compatibility, but requires careful parameter optimization based on specific contaminant characteristics. Plasma cleaning emerges as a highly effective alternative for organic film removal on sensitive components, particularly where substrate preservation is paramount.

Future research directions should focus on real-time monitoring of cleaning processes, advanced simulation of laser-material interactions, and development of combinatorial approaches that leverage the strengths of multiple technologies. As optical systems continue to advance in power and precision, the role of validated, contaminant-specific cleaning protocols will only grow in importance for ensuring optimal performance and longevity.

Optical components form the core of numerous advanced technologies, from high-energy laser systems to semiconductor manufacturing and biomedical devices. The performance and longevity of these components critically depend on their surface quality, making cleaning processes not merely maintenance procedures but fundamental to optical surface integrity. Within research focused on validating laser cleaning effectiveness, substrate preservation emerges as the paramount objective—the process must remove contaminants without introducing new damage or altering the functional properties of the optical surface. This guide provides a comparative analysis of cleaning methodologies, evaluating their performance against the central goal of preserving substrate integrity.

Contaminant Types and Their Impact on Optical Surfaces

Understanding the specific contaminants affecting optical surfaces is the first step in selecting an appropriate cleaning strategy. Different contaminants necessitate different removal mechanisms and pose varying threats to surface integrity.

- Particles: Residual polishing abrasives (e.g., cerium oxide) or environmental dust particles act as nano precursors for laser-induced damage. Under laser irradiation, these absorbing sites can initiate catastrophic failure, drastically reducing the component's damage threshold [21] [22].

- Organic Films: Residuals from optical paint, cement, or fingerprints create thin organic layers. These films increase light absorption and can lead to thermal loading and damage under high-power laser operation. Their presence is a primary reason for incorporating solvent-based pre-cleaning steps [22].

- Carbonaceous Contamination: In vacuum environments of high-power laser systems, volatile organic compounds can deposit on optics, forming carbon-based layers. This contamination is particularly detrimental as it directly absorbs laser energy, leading to coating degradation and reduced laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) [6].

Comparative Analysis of Optical Cleaning Methodologies

The following analysis compares three primary cleaning approaches, with experimental data highlighting their efficacy and potential impact on substrate integrity.

Table 1: Comparison of Optical Surface Cleaning Methodologies

| Cleaning Method | Mechanism of Action | Best For Contaminant Type | Typical Surface Quality (RMS Roughness) | LIDT Performance | Key Advantages | Key Risks to Substrate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Chemical Cleaning | Chemical dissolution and emulsification | Organic films, some particles | < 3 Å (on fused silica) [22] | Can restore high LIDT with proper process [22] | High efficacy on organics, established protocols | Chemical attack on sensitive substrates, water staining |

| Laser Cleaning | Thermal ablation, shockwaves, thermal stress [23] | Particles, dry contaminants | N/A (Substrate-dependent) | Effective on insulators; parameter-sensitive [23] | Non-contact, precision cleaning, automation-friendly | Thermal stress cracking, surface melting, ablation if parameters are incorrect [23] [24] |

| Plasma Cleaning | Chemical reaction with radicals, ion bombardment, atom-by-atom removal [21] [6] | Organic and carbonaceous films | Can reduce roughness (e.g., SiC from 1.090 nm to 0.055 nm) [6] | Improves damage resistance by removing absorptive contaminants [6] | Non-contact, atomic-level removal, no secondary waste | Potential surface etching at high power, requires vacuum equipment [21] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data of Cleaning Methods

| Cleaning Method | Removal Efficiency | Process Parameters | Impact on Optical Transmission | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonic Wet Cleaning | Particle density reduction sub-micrometer scale [22] | Varying ultrasonic frequencies (40-500 kHz), alkaline solutions [22] | Not explicitly quantified, but critical for pre-coating LIDT [22] | Surface particle density analysis, LIDT testing [22] |

| Laser Cleaning | Effective contaminant removal on glass insulators (ESDD/NSDD measurement) [23] | 8 m/s scan speed, varying laser power [23] | Not directly measured, but surface cleanliness restored | Equivalent Salt Deposit Density (ESDD) measurement, thermal monitoring [23] |

| Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning | Efficient removal of organic contaminants from coated optics [6] | Oxygen/Argon gas, RF power, pressure-controlled [6] | Restores near-baseline optical performance [6] | Langmuir probe, emission spectroscopy, transmittance measurement [6] |

Decision Workflow for Cleaning Method Selection

The following diagram illustrates a systematic approach for selecting an appropriate cleaning method based on substrate and contaminant properties, aligning with the goal of substrate preservation.

Experimental Protocols for Validating Cleaning Effectiveness

Rigorous validation is essential for confirming that cleaning processes achieve their goal without compromising the substrate. The following protocols are standard in the field.

Objective: To quantify surface contamination levels and micro-roughness before and after cleaning.

- Materials: Inspection microscope (e.g., Leica INM200 with 100x magnification), atomic force microscope (AFM), dark-field microscope.

- Procedure:

- Inspect samples in transmission and reflection using a spot lamp for initial gross contamination assessment.

- Perform automated microscope inspection with high-resolution camera (e.g., 2.3 MP Sony sensor) to detect particles >83 nm.

- Measure RMS roughness via AFM on multiple sample regions (typically 5-10 locations).

- Document particle density (particles/cm²) and size distribution.

- Interpretation: Successful cleaning shows reduced particle density without increased RMS roughness, which would indicate surface damage.

Objective: To determine the resistance of cleaned optical surfaces to high-power laser irradiation.

- Materials: Pulsed laser system (e.g., 1064 nm, ns-pulsed), beam delivery optics, energy measurement devices, online microscopy.

- Procedure:

- Place sample in test bench at normal incidence or specified angle.

- Expose multiple sites to laser pulses with gradually increasing fluence (S-on-1 test).

- Monitor each site for plasma flash or scattering increase indicating damage.

- Characterize damage morphology post-test via microscopy.

- Apply statistical analysis (e.g., linear regression) to damage probability data to determine LIDT value (usually at 0% damage probability).

- Interpretation: Effective cleaning increases LIDT; organic contaminants can reduce LIDT by up to 60% [6].

Objective: To measure the recovery of optical properties after cleaning.

- Materials: Spectrophotometer, ellipsometer, scatter measurement apparatus.

- Procedure:

- Measure baseline transmittance/reflectance spectrum before contamination.

- Re-measure after contamination and after cleaning.

- Calculate performance recovery: [(Tafter - Tbefore)/(Tclean - Tbefore)] × 100%.

- Perform spectroscopic ellipsometry to detect ultrathin residual layers.

- Interpretation: Successful cleaning restores >95% of original optical performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Optical Cleaning Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fused Silica Substrates | High-quality reference substrate with well-characterized properties | Standardized test samples for cleaning process development [22] |

| Deconex OP Solutions | Alkaline cleaning solutions for precision cleaning | Removal of polishing residuals in ultrasonic cleaning processes [22] |

| Sol-Gel SiO₂ Coatings | Representative functional coatings for laser optics | Testing cleaning compatibility with sensitive AR coatings [6] |

| Oxygen and Argon Gases | Process gases for plasma cleaning | Generation of reactive species in low-pressure plasma cleaning [6] |

| Langmuir Probe | Diagnostic tool for plasma characterization | Measuring plasma potential, ion density, and electron temperature [6] |

Preserving optical surface integrity during cleaning requires a methodical approach that matches cleaning technology to specific contamination challenges and substrate properties. Wet chemical cleaning remains highly effective for organic films, laser cleaning offers precision for particle removal, and plasma cleaning excels at removing carbonaceous contamination without secondary waste. The validation framework presented here—encompassing surface quality assessment, LIDT testing, and optical performance validation—provides researchers with the necessary tools to quantitatively confirm cleaning effectiveness while ensuring substrate preservation. As optical systems continue to advance toward higher powers and greater precision, the development of cleaning methodologies that prioritize substrate integrity will remain critical to performance and reliability.

Laser-Induced Damage Thresholds (LIDT) in Optical Coatings and Materials

The Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) represents the maximum optical energy or power density an optical component can withstand before sustaining irreversible damage. It is a critical parameter determining the performance and longevity of high-power laser systems across various scientific, industrial, and medical applications. For optical coatings—typically the most vulnerable element in laser systems—LIDT depends on multiple factors including coating material properties, deposition techniques, substrate characteristics, and laser parameters such as wavelength, pulse duration, and repetition rate [25]. Understanding and comparing LIDT values across different materials and experimental conditions is fundamental to advancing laser technology, particularly in validating surface preparation techniques like laser cleaning, which aim to enhance optical component durability by removing contamination and defects that initiate damage [26] [27].

Quantitative Comparison of LIDT Performance

The LIDT performance of optical materials varies significantly based on material composition, coating structure, and operational laser regime. The following tables summarize key experimental data for direct comparison.

Table 1: LIDT of Coating Materials under Pulsed Laser Irradation

| Material | Laser Parameters | LIDT Value | Substrate | Deposition Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HfO₂ (single-layer) | 1064 nm, 12 ns | 22.13 J/cm² | K9 Glass | Ion Beam Sputtering (IBSD) | [28] |

| ZrO₂ (single-layer) | 1064 nm, 12 ns | 12.26 J/cm² | K9 Glass | Ion Beam Sputtering (IBSD) | [28] |

| SiO₂ (single-layer) | 1064 nm, 12 ns | 14.56 J/cm² | K9 Glass | Ion Beam Sputtering (IBSD) | [28] |

| CVD Diamond (bulk) | CO₂, 100 ns | 8 J/cm² | N/A | Chemical Vapor Deposition | [29] |

| ZnSe (bulk) | CO₂, 100 ns | 2.8 J/cm² | N/A | N/A | [29] |

| Ge (bulk) | CO₂, 100 ns | 1.7 J/cm² | N/A | N/A | [29] |

| ZrO₂/SiO₂ (AR coating) | 1064 nm, 9.6 ns | >40 J/cm² | Fused Silica | RF Sputtering | [30] |

Table 2: LIDT under Continuous Wave (CW) Laser Irradiation and Substrate Comparison

| Coating/Substrate Combination | Laser Parameters | LIDT Value | Notes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZnS/YbF₃ AR on Diamond | 10.6 µm, CW | 15,287 W/cm² | 28.5% higher than ZnSe | [29] |

| ZnS/YbF₃ AR on ZnSe | 10.6 µm, CW | 11,890 W/cm² | Baseline for comparison | [29] |

| Gold (Au) Coating | ~1064 nm, CW | ~1.5×10⁵ W/cm | Transition to CW regime | [31] |

| Aluminum (Al) Coating | ~1064 nm, CW | ~4×10⁴ W/cm | Transition to CW regime | [31] |

Table 3: LIDT Scaling with Pulse Duration for Metallic Coatings [31]

| Pulse Duration Range | Observed LIDT Scaling Law | Dominant Damage Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| 10 fs - 200 ps | Nearly constant (Fluence~τ⁰) | Ablation Dominated: Electron-phonon interactions, ultrafast ablation. |

| 200 ps - 10 ns | Fluence ~ τ⁰‧⁵ | Thermal Diffusion: Balance of deposited energy and lateral heat diffusion. |

| 10 ns - 10 s (CW) | Power Density ~ Constant | Steady-State Heating: Bulk temperature rise, melting. |

Experimental Protocols for LIDT Measurement

Standardized methodologies are crucial for obtaining reliable and comparable LIDT data. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) 21254 provides the primary framework for laser damage testing.

Standardized Testing Protocols

The ISO 21254 standard defines several critical testing protocols. The 1-on-1 test involves irradiating multiple fresh sites on a sample with a single laser pulse per site, gradually increasing the fluence until damage occurs, which is ideal for determining the intrinsic threshold. The S-on-1 test irradiates a single site multiple times (e.g., S=1000) at each fluence level to assess damage probability under cumulative exposure, simulating real-world operational conditions where optics experience repetitive laser pulses [31]. Damage detection typically combines in-situ methods like monitoring scattered light from the surface and ex-situ inspection using Nomarski microscopy to identify and confirm the onset of damage [30].

Representative Experimental Workflow

A typical LIDT experiment follows a structured workflow from preparation to data analysis, ensuring consistency and reliability in results.

Specific Methodologies from Cited Studies

- Study on Metallic Coatings (Optics Express, 2025): Researchers tested seven metallic coatings across pulse durations from 10 fs to 10 seconds. They used 1-on-1 and S(1000)-on-1 protocols per ISO 21254-2. Beam diameters were maintained between 195–230 μm (1/e² level), and incident fluence was controlled via a motorized attenuator. The Highest-Before-First-Damage (HBFD) method determined the LIDT, calculated as the average between the lowest damaging fluence and the highest non-damaging fluence [31].

- Study on AR Coatings for CO₂ Lasers (Coatings, 2025): The LIDT for ZnS/YbF₃ AR coatings on diamond and ZnSe substrates was evaluated under continuous-wave (CW) 10.6 μm laser irradiation. The laser spot diameter was 2.5 mm, and the power density was increased until visible damage occurred. The damage threshold was defined as the power density (W/cm²) causing irreversible damage, confirmed by microscopy [29].

- Study on Single-Layer Films (Applied Surface Science, 2008): ZrO₂, SiO₂, and HfO₂ single-layer films deposited via Ion Beam Sputtering were tested with a 1064 nm laser at 12 ns pulse width. The experiments followed a 1-on-1 procedure, and damage was identified by audible acoustic signals, plasma flashes, and subsequent optical microscopy [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

This table catalogs key materials and equipment frequently employed in LIDT research and high-power optical coating fabrication.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for LIDT Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| High-Index Coating Materials | Form high-reflectance layers in dielectric stacks. | HfO₂, ZrO₂, Ta₂O₅, TiO₂, ZnS (for IR) [28] [29] |

| Low-Index Coating Materials | Form low-reflectance layers and spacer layers. | SiO₂, YbF₃, LiF [29] [30] |

| High-Thermal-Conductivity Substrates | Dissipate heat, reduce thermal lensing, increase LIDT in CW regimes. | CVD Diamond, Polished Copper [29] |

| Standard Optical Substrates | Support for coatings; chosen for low absorption and surface quality. | Fused Silica (Spectrosil 2000), Borofloat 33, K9 Glass, ZnSe [28] [30] |

| Deposition Systems | Fabricate thin-film coatings with controlled properties. | Ion Beam Sputtering (IBS), Ion-Assisted Deposition (IAD), RF Sputtering, Thermal Evaporation [28] [25] [30] |

| LIDT Test Lasers | Provide calibrated irradiation sources across different regimes. | Q-switched Nd:YAG (1064 nm, ns), Ti:Sapphire (fs/ps), CO₂ Laser (10.6 μm, CW) [31] [29] |

| Diagnostic Tools | Characterize absorption, defects, and surface morphology. | Photothermal Common-Path Interferometry (PCI), Nomarski Microscope, Atomic Force Microscope (AFM), Scattered Light Detection [30] |

Systematic comparison of LIDT performance reveals that material selection, deposition technique, and substrate thermal properties are paramount in designing optics for high-power lasers. Under pulsed conditions, materials like HfO₂ and CVD diamond demonstrate superior resistance, whereas under CW irradiation, the superior thermal conductivity of diamond substrates provides a significant LIDT advantage over traditional materials like ZnSe. The emergence of standardized testing protocols (ISO 21254) enables reliable comparison of data across studies. Furthermore, the effectiveness of any optical surface treatment, including laser cleaning for contamination removal [27], must ultimately be validated against these rigorous LIDT standards to ensure enhanced component lifetime and system reliability. Continued research into novel coating materials, advanced deposition processes, and comprehensive damage testing remains essential for pushing the frontiers of high-power laser applications.

Implementing Laser Cleaning: Protocols for Optical Surface Applications

The effectiveness of laser cleaning on sensitive optical surfaces is highly dependent on the specific laser technology employed. Within the context of validating laser cleaning effectiveness, the selection of an appropriate laser system is paramount. Fiber, Nd:YAG, and UV lasers each offer distinct mechanisms of interaction with contaminants and substrates, leading to varying outcomes in cleaning efficiency, surface preservation, and overall process safety. This guide provides an objective comparison of these three laser types, consolidating experimental data and detailed methodologies to support researchers and scientists in making informed decisions for optical surface remediation projects. The performance of each laser is framed around their application in cleaning optical components, a critical step for maintaining performance in high-energy laser systems, synchrotron radiation beamlines, and historical conservation.

Laser Fundamental Types and Characteristics

Lasers are categorized primarily by their gain medium, the material which amplifies light, as this defines their fundamental operating properties and typical applications [32]. The three laser systems under review—Fiber, Nd:YAG, and UV—span different categories. Fiber and Nd:YAG lasers are both types of solid-state lasers, while UV lasers often use solid-state crystals to generate their specific wavelength and represent a different class based on their cold processing mechanism [32] [33].

The mode of operation is another critical differentiator. Lasers can operate as continuous-wave (emitting a constant beam) or pulsed (emitting energy in short bursts) [32]. Pulsed lasers are predominantly used in precision cleaning and are further classified by their pulse duration, which ranges from milliseconds (ms) down to femtoseconds (fs) [32]. Ultrashort pulses (picosecond and femtosecond) enable extremely precise ablation with minimal thermal effects on the substrate, which is crucial for delicate optical surfaces [32] [34].

Table 1: Fundamental Classifications of Laser Types Relevant to Optical Cleaning.

| Laser Type | Gain Medium | Primary Operating Mode | Typical Wavelength(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiber Laser | Rare-earth-doped silica glass (e.g., Ytterbium) [32] | Pulsed (Nanosecond to Ultrashort) [32] | 1064 nm (Infrared) [33] [35] |

| Nd:YAG Laser | Neodymium-doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet crystal [32] | Pulsed (Nanosecond most common) [36] | 1064 nm (Infrared); 532 nm (Green) via harmonic generation [32] |

| UV Laser | Frequency-tripled solid-state crystals (e.g., for 355 nm) [33] | Pulsed (Nanosecond to Femtosecond) [34] | 355 nm (Ultraviolet) [33] |

Comparative Analysis of Laser Technologies

Fiber Lasers

Fiber lasers utilize an optical fiber doped with a rare-earth element as the gain medium, producing a high-quality, precise beam [32]. They are renowned for their robustness, high electrical efficiency, and low operating costs [32]. In cleaning applications, they operate primarily through a thermo-mechanical mechanism.

- Cleaning Mechanism: The intense, pulsed infrared beam is absorbed by surface contaminants, causing rapid heating and subsequent vaporization, ablation, or thermal-induced vibration that dislodges the material [35]. The effectiveness of this process hinges on the significant difference in absorption between the contaminant and the underlying substrate.

- Experimental Evidence for Optical Cleaning: A study on cleaning metal mirrors for optical diagnostics in ITER demonstrated that pulsed radiation from a fiber laser could effectively recover the optical properties of the mirror surface [37]. The research found that efficient cleaning was achieved at a relatively low power density of less than 10⁷ W/cm², where contaminants were removed in the solid phase with an insignificant thermal effect on the mirror substrate [37]. This highlights the capability of fiber lasers for delicate cleaning tasks where preserving the optical properties of the substrate is critical.

Nd:YAG Lasers

Nd:YAG lasers are a workhorse solid-state technology. Their infrared output can be efficiently converted to green (532 nm) and ultraviolet (355 nm) wavelengths using nonlinear crystals, though the fundamental 1064 nm wavelength is most common for cleaning [32] [36].

- Cleaning Mechanism: Similar to fiber lasers, nanosecond-pulsed Nd:YAG lasers at 1064 nm typically remove material through thermal ablation and vaporization. The high peak power of the pulses rapidly heats the contaminant layer, causing it to be ejected from the surface.

- Experimental Evidence for Optical Cleaning: Research on cleaning a 48 nm thick gold layer from fused silica mirrors demonstrated the high efficiency of a nanosecond-pulsed Nd:YAG laser [36]. By optimizing parameters like pulse duration, beam incidence angle, and spot overlapping, the study achieved a cleaning efficiency of approximately 98% in just 3 minutes for a 48 cm² area. The quality of the cleaned surface was verified using microscopy, SEM, and reflectivity measurements, confirming the method as a low-cost solution for reclaiming damaged optical components [36].

UV Lasers

UV lasers represent a different class of interaction, often referred to as "cold processing" [33]. The high-energy ultraviolet photons directly break chemical bonds in the contaminant material, a process known as photochemical ablation.

- Cleaning Mechanism: Unlike the thermal mechanisms of IR lasers, UV laser cleaning does not rely on significant heat generation. This makes it ideal for heat-sensitive materials. The breaking of molecular bonds allows for the precise removal of material layer-by-layer with minimal thermal damage to the substrate [34].

- Experimental Evidence for Optical Cleaning: A study on the safe cleaning of historical stained-glass from the 15th century employed a UV femtosecond laser [34]. The ultrashort pulses at UV wavelength (355 nm) allowed for the controlled removal of an unwanted crust—composed of hydrated and anhydrous sulphates and apatite—without damaging the underlying glass or the delicate grisaille (painted) layer. A multi-scan series process was designed to control the ablated crust thickness precisely, avoiding heat accumulation and preserving the integrity of the historical artifact [34].

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Optical Surface Cleaning Applications.

| Parameter | Fiber Laser | Nd:YAG Laser | UV Laser |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Cleaning Mechanism | Thermal ablation, Thermo-mechanical vibration [35] | Thermal ablation, Vaporization [36] | Photochemical bond breaking (Cold Ablation) [34] [33] |

| Typical Pulse Duration | Nanosecond to Ultrashort [32] | Nanosecond [36] | Femtosecond to Nanosecond [34] |

| Heat Affected Zone (HAZ) | Low to Moderate (depends on pulse width) | Moderate (for nanosecond pulses) | Very Low [34] |

| Suitable Contaminants | Oxides (rust), paints, coatings on metals [37] [35] | Metal coatings (e.g., Au), organic layers [36] | Inorganic crusts, fine particulates, organic films [34] |

| Suitable Optical Substrates | Metal mirrors, fused silica (with care) [37] | Fused silica, coated optics [36] | Colorless glass, stained-glass, sensitive polymers [34] |

| Key Advantage for Cleaning | High efficiency on metals, low operating costs [32] | Proven efficiency for delicate metal coating removal [36] | Exceptional control and safety for sensitive surfaces [34] |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the validity and reproducibility of laser cleaning experiments, a standardized approach to methodology is essential. The following protocols are synthesized from the cited research.

General Workflow for Laser Cleaning Validation

The diagram below outlines a generalized experimental workflow applicable to validating the cleaning effectiveness of any laser system on an optical surface.

Detailed Methodologies

Sample Preparation and Initial Characterization:

- Sample Preparation: The optical substrate (e.g., fused silica mirror, historical glass) is prepared, and the contaminant (e.g., rust, gold coating, sulfate crust) is applied naturally or artificially [7] [36].

- Initial Characterization: The sample is analyzed using techniques such as:

- Optical Microscopy and Confocal Microscopy to assess surface morphology and crust thickness [34].

- Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for high-resolution surface imaging [34] [36].

- Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS/EDX) to determine the elemental composition of the contaminant layer [34].

- Raman Spectroscopy to identify chemical compounds present [34].

- Angle-dependent Reflectivity Measurement to establish baseline optical performance [36].

Laser Parameter Selection and Cleaning:

- Parameter Optimization: A systematic investigation of key laser parameters is conducted, often via a design of experiments (e.g., single-factor analysis, orthogonal arrays) [35]. Critical parameters include:

- Laser Fluence / Power Density (J/cm² or W/cm²): Must be above the ablation threshold of the contaminant but below the damage threshold of the substrate [37] [36].

- Pulse Repetition Frequency (kHz): Affects heat accumulation [35].

- Scanning Speed (mm/s) and Spot Overlap: Determine the number of pulses per spot and the overall processing time [35] [36].

- Wavelength: Selected based on the absorption properties of the contaminant versus the substrate.

- Cleaning Execution: The laser is applied to the sample using a galvanometer scanner or linear stages. For enhanced control, a multi-scan series process is often employed instead of a single high-fluence pass to avoid heat accumulation and control the ablated depth precisely [34].

- Parameter Optimization: A systematic investigation of key laser parameters is conducted, often via a design of experiments (e.g., single-factor analysis, orthogonal arrays) [35]. Critical parameters include:

Post-Cleaning Analysis and Validation:

- The same characterization techniques used in the initial analysis are reapplied to the cleaned area.

- Cleaning Efficiency is quantified. This can be measured as:

- The absence of substrate damage is confirmed. This involves checking for:

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key materials, equipment, and software solutions essential for conducting rigorous laser cleaning validation experiments, as derived from the cited research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Laser Cleaning Validation.

| Item / Solution | Function in Research | Specific Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Pulsed Laser System | The core tool for performing the cleaning ablation. | Fiber laser (1064 nm) [37], Nd:YAG laser (1064 nm, ns pulses) [36], UV femtosecond laser (355 nm) [34]. |

| Optical Microscope | Initial and post-process inspection of surface morphology and contamination. | Used for qualitative assessment before and after cleaning in all cited studies [34] [36]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | High-resolution imaging to verify contaminant removal and inspect for sub-micron substrate damage. | Used to analyze the surface of cleaned gold mirrors [36] and stained-glass [34]. |

| Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) | Quantitative elemental analysis to confirm the removal of contaminant elements. | Used to identify components of the crust on stained-glass and confirm their removal [34]. |

| Spectrophotometer / Reflectometer | Measures the recovery of optical performance (reflectance/transmittance) of the cleaned surface. | Angle-dependent reflectivity measurement using a synchrotron radiation beamline to validate mirror performance [36]. |

| Confocal Microscope / Profilometer | Provides 3D surface topography and quantitative measurement of surface roughness. | Used to control the thickness of ablated material and assess surface quality after UV laser cleaning [34]. |

| Specialized Software | For controlling laser parameters, designing scan paths, and analyzing experimental data. | EzCad2 for laser control [39], image analysis software for efficiency calculation [36]. |

The validation of laser cleaning effectiveness on optical surfaces demands a technology-specific approach. Fiber lasers offer an efficient, cost-effective solution for cleaning metallic optical components and mirrors, with proven success in recovering reflectivity with minimal thermal impact. Nd:YAG lasers provide a versatile and powerful tool, capable of achieving exceptionally high cleaning efficiencies for specific tasks, such as the removal of metal coatings from delicate fused silica substrates. UV lasers, particularly those with ultrashort pulses, stand out for applications requiring the utmost precision and minimal thermal load, making them indispensable for cleaning historically valuable or highly sensitive optical materials.

The choice among them is not a matter of superiority but of appropriateness for the specific contaminant-substrate system. Validation through the rigorous experimental protocols outlined herein—including comprehensive pre- and post-characterization—is critical for ensuring that cleaning goals are met without compromising the integrity of the valuable optical surface. This comparative guide provides a foundational framework for researchers and scientists to select and validate the optimal laser system for their specific optical cleaning challenges.

In the realm of high-precision optics, particularly within intense laser systems and pharmaceutical drug development instrumentation, maintaining pristine optical surfaces is paramount for ensuring performance, accuracy, and longevity. Laser cleaning has emerged as a sophisticated, non-contact method for the selective removal of contaminants—including organic films, particles, and chemical residues—from sensitive optical components without compromising their delicate surfaces. This process is governed by a complex interplay of parameters that require meticulous optimization to balance cleaning efficacy with substrate preservation. The validation of these cleaning regimens is a critical research focus, as the laser-induced damage threshold (LIDT) of optical components is directly threatened by surface contamination, which can lead to performance degradation under high-power laser irradiation [40] [6] [41].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of laser cleaning against alternative technologies and details the experimental protocols essential for establishing effective, validated cleaning parameters tailored for optical surfaces. The principles of laser cleaning, primarily laser ablation, involve directing a high-intensity laser beam at the contaminated surface. Contaminants absorb the laser energy, leading to rapid heating and subsequent vaporization or disintegration, while the underlying reflective substrate remains undamaged [42]. For optical components, which often have specialized chemical coatings, the precision of this ablation process is critical. Researchers and scientists must navigate a multi-dimensional parameter space—including wavelength, pulse duration, fluence, and repetition rate—to develop a cleaning protocol that effectively restores optical performance without inducing microscopic damage that could initiate larger failures [40] [43].

Comparative Analysis of Cleaning Technologies

Selecting an appropriate cleaning technology requires a thorough understanding of the specific application, the nature of the contaminants, and the sensitivity of the optical substrate. The table below provides a structured comparison of laser cleaning against other prominent methods used for high-value optical components.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Optical Surface Cleaning Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism of Action | Best For Contaminants | Precision & Selectivity | Risk of Substrate Damage | Environmental & Operational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Cleaning | Ablation via directed photon energy (thermal, photochemical, or mechanical shock) [44] [42] | Organic films, particles, thin metal layers, oxides [43] [41] | High (can be tuned for selective removal) [42] | Medium (thermo-mechanical damage if parameters are incorrect) [40] [43] | No chemicals; generates gaseous/vapor waste; requires fume extraction [42] |

| Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning | Chemical reaction and physical sputtering with ionized reactive species (e.g., oxygen radicals) [6] | Organic carbonaceous films [6] [41] | Low (blanket surface treatment) | Low (non-thermal process suitable for sensitive coatings) [6] | Uses process gases (O₂, Ar); no secondary waste [6] |

| Wet Chemical Cleaning | Dissolution and dilution via chemical solvents | Soluble residues, oils, greases | Low | Medium (potential for solvent permeation or coating degradation) | Hazardous chemical use, storage, and disposal [44] |

| Ultrasonic Cleaning | Cavitation-induced mechanical scouring in a liquid medium | Particulate matter | Low | High (cavitation can erode fragile coating structures) | Uses liquid baths and detergents; generates chemical waste |

Key Insights from Comparative Data

- Laser Cleaning excels in applications requiring localized, selective removal without chemical residues. Its tunability makes it ideal for complex optical assemblies where only specific areas require treatment. However, the risk of thermal damage necessitates rigorous parameter optimization [43] [42].

- Low-Pressure Plasma Cleaning is a highly effective, uniform process for removing thin, pervasive organic contaminants from large-aperture optics without disassembly, making it suitable for in-situ maintenance in vacuum-based laser systems [6] [41].

- Traditional Methods like wet chemical and ultrasonic cleaning, while useful for gross contamination, pose significant risks to delicate optical coatings through chemical attack, immersion, or mechanical vibration, and their environmental footprint is substantially higher [44].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Laser Cleaning Efficacy

A scientifically robust validation protocol is fundamental to establishing a reliable laser cleaning regimen. The following methodology outlines the key steps for evaluating cleaning effectiveness and preserving optical functionality.

Sample Preparation and Contamination

- Substrate Selection: Utilize optical components relevant to the research, such as fused silica substrates with sol-gel SiO₂ anti-reflective coatings prepared via dip-pull coating machines, which are standard in high-power laser applications [6].

- Contamination Process: For organic contamination studies, a controlled dip-coating or vapor deposition method can be used to apply a uniform layer of a contaminant (e.g., pump oils, silicones) to mimic real-world conditions. Accelerated aging protocols in environmental chambers can further simulate long-term exposure [6].

Laser Cleaning Setup and Parameter Matrix

- Equipment: A typical setup includes a nanosecond-pulsed fiber laser (e.g., 1064 nm wavelength), computer-controlled galvanometer scanning system, and integrated fume extraction [43].

- Parameter Optimization: A factorial experimental design should be employed to systematically investigate the effects of key parameters. The table below summarizes findings from recent studies on different substrate-coating systems.

Table 2: Laser Parameter Optimization and Outcomes from Experimental Studies

| Study Focus | Optimal Laser Parameters | Cleaning Mechanism | Resultant Surface Morphology | Performance Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Removing Al Layer from Ceramic [43] | Power: 120 W, Pulse Width: 200 ns, Frequency: 240 kHz, Speed: 6000 mm/s | Thermal ablation & thermo-mechanical stress from thermal expansion mismatch | Complete Al removal; Ra = ~13.8 µm; No cracking or burning | Ceramic substrate intact; complete coating removal confirmed via SEM |

| Liquid-assisted Rust Removal from Q235 Steel [7] | Combined continuous & pulsed laser with water layer (0.25-0.5 mm) | Synergy of laser ablation, shock waves, and liquid evaporation | Optimized morphology; reduced thermal damage vs. dry cleaning | Simulation and experiment showed high removal efficiency |

| Paint Removal from CFRP [44] | Wavelength: Shorter (UV), Pulse Duration: Nanosecond regime | Photochemical decomposition & thermal ablation | Minimal resin damage; clean fiber exposure | Preservation of composite tensile strength |

Post-Cleaning Analysis and Validation Metrics

- Surface Morphology: Utilize Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to visualize the micro-scale cleanliness and inspect for any evidence of melting, cracking, or fiber damage (in composites) [43] [44].

- Surface Roughness: Quantify using a surface roughness tester (e.g., TR200). Changes in Ra and Rq values indicate the extent of material interaction and can correlate with post-cleaning light scatter [43].

- Chemical Analysis: Employ techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) or Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to verify the absence of contaminant molecular signatures [6].

- Functional Optical Performance: Measure the transmittance/reflectance spectrum to confirm restoration of baseline optical properties. Crucially, evaluate the Laser-Induced Damage Threshold (LIDT) to ensure the cleaning process has not created defects that predispose the optic to failure under high power [40] [41].

Visualizing the Laser Cleaning Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for developing and validating an optimized laser cleaning protocol, from initial setup to final performance verification.

Figure 1: Laser cleaning validation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key equipment, reagents, and materials essential for conducting rigorous laser cleaning validation research on optical surfaces.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Laser Cleaning Validation

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Nanosecond Pulsed Fiber Laser | Delivers high peak power in short pulses for controlled ablation, minimizing heat diffusion. | Standard source for removing metal layers and contaminants without excessive thermal load [43] [42]. |

| Sol-Gel Coating Materials | Enables in-house preparation of standardized optical coatings with controlled properties for testing. | Used to create anti-reflective coatings on fused silica substrates for contamination and cleaning studies [6]. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) | Provides high-resolution imaging of surface topography pre- and post-cleaning at micro/nano scale. | Critical for visualizing complete contaminant removal and identifying substrate damage like micro-cracks [43]. |

| Surface Roughness Tester | Quantifies changes in surface texture (Ra, Rq) resulting from the laser cleaning process. | Used to correlate laser parameters with changes in surface morphology; e.g., Ra increase from 9.4 to 13.8 µm after Al layer removal [43]. |

| Low-Pressure Plasma System | Serves as a non-laser baseline or alternative for removing organic contaminants via reactive ions/radicals. | Effectively removes carbonaceous films from optical coatings to restore transmittance and LIDT [6] [41]. |

| Spectrophotometer | Measures transmittance and reflectance spectra to quantify the restoration of optical performance. | Validates that cleaning has returned the component's optical properties to their pre-contamination baseline [6] [41]. |

Advanced Beam Delivery Systems for Complex Optical Geometries

Beam delivery systems are critical components that transfer laser energy from the source to the target surface with precision and efficiency. In the context of laser cleaning—a non-contact, environmentally friendly alternative to chemical and abrasive methods—the choice of beam delivery system directly influences the effectiveness, safety, and quality of the process [45] [46]. For researchers validating laser cleaning on sensitive optical surfaces, selecting the appropriate delivery method is paramount to achieving complete contaminant removal without damaging the underlying substrate [23] [11].